Abstract

Cavβ subunits are essential for surface expression of voltage-gated calcium channel complexes and crucially modulate biophysical properties like voltage-dependent inactivation. Here, we describe the discovery and characterization of a novel Cavβ2 variant with distinct features that predominates in the retina. We determined spliced exons in retinal transcripts of the Cacnb2 gene, coding for Cavβ2, by RNA-Seq data analysis and quantitative PCR. We cloned a novel Cavβ2 splice variant from mouse retina, which we are calling β2i, and investigated biophysical properties of calcium currents with this variant in a heterologous expression system as well as its intrinsic membrane interaction when expressed alone. Our data showed that β2i predominated in the retina with expression in photoreceptors and bipolar cells. Furthermore, we observed that the β2i N-terminus exhibited an extraordinary concentration of hydrophobic residues, a distinct feature not seen in canonical variants. The biophysical properties resembled known membrane-associated variants, and β2i exhibited both a strong membrane association and a propensity for clustering, which depended on hydrophobic residues in its N-terminus. We considered available Cavβ structure data to elucidate potential mechanisms underlying the observed characteristics but resolved N-terminus structures were lacking and thus, precluded clear conclusions. With this description of a novel N-terminus variant of Cavβ2, we expand the scope of functional variation through N-terminal splicing with a distinct form of membrane attachment. Further investigation of the molecular mechanisms underlying the features of β2i could provide new angles on the way Cavβ subunits modulate Ca2+ channels at the plasma membrane.

Keywords: alternative splicing, biophysics, calcium channel, retina, photoreceptor, physiology

Voltage-gated calcium (Ca2⁺) channel Cavβ subunits (Cavβ) are cytosolic auxiliary subunits that play an essential role in regulating the surface expression and gating properties of voltage-gated Ca2⁺ channels (VGCC). As critical modulators of VGCC properties, they act by increasing open probability, hyperpolarizing the voltage dependence of activation (1), and increasing the number of channels on the plasma membrane via different mechanisms (2) thus enhancing macroscopic Ca2+ currents several-fold. Importantly, all Cavβ subunits also enhance voltage-dependent inactivation (VDI), with the notable exception of splice variants β2a and β2e that show the opposite effect, slowing down, and decreasing VDI (3).

As part of the membrane-associated guanylate kinase protein family, Cavβ subunits are cytoplasmic proteins that contain a conserved Src homology 3 (SH3) domain that are involved in anchoring VGCC complexes at presynaptic sites, a guanylate kinase-like (GK) domain with which they bind to the α-interacting domain of Cav1 and Cav2 I–II loops and a HOOK domain critical in modulating VDI of its associated VGCC (4). However, it is the N-terminus that imparts the profoundly VDI-slowing properties to β2a and β2e and thus constitutes an important functional determinant.

The N-terminal end is extensively alternatively spliced in Cavβ2 (5), with canonical alternative exons 1A|B and 2A|B|C|D, giving rise to at least five different N-terminal sequences that have profound impact on the biophysical properties of associated Ca2⁺ channels (for reviews, see Refs. (2, 5, 6, 7)). It has been shown that both β2a and β2e can associate with the plasma membrane independent of binding to an α1 subunit. For β2a, this membrane targeting is mediated by palmitoylated cysteines in its N-terminus (8) and underlies its effect on channel properties (9). β2e interacts with the plasma membrane through positively charged residues and hydrophobic side chains in its N-terminal sequence (10). It is this membrane anchoring by the alternatively spliced N-termini that crucially determines the VDI-slowing effect of β2a and β2e (5, 10).

Thus far, β2a and β2e have been the only two N-terminus variants described among all Cavβ isoforms to be membrane anchored. In the retina, the Ca2⁺ channel complex expressed in rod and cone photoreceptors responsible for synaptic release was thought to contain a splice variant of β2a, termed β2X13 (11), in complex with Cav1.4-α1 and α2δ-4. The β2X13 variant is identical to β2a except for its HOOK domain, which contains short exon 7B instead of the longer exon 7A. Screening mouse retina RNA-Seq data (12), we confirmed the shorter HOOK domain with predominant splicing of exon 7B over exon 7A in β2. However, we observed unexpected N-terminal β2 splicing containing a novel exon, which suggested the existence of a hitherto undescribed N-terminus splice variant. Therefore, we aimed to investigate fundamental characteristics of this novel β2 variant, including its expression inside and outside the retina, biophysical properties it imparts on Ca2+ channels, intrinsic membrane targeting, and the functional implications that distinguish it from the established canonical variants.

Results

RNA-based evidence for a novel splice variant of Cavβ2 expressed in mammalian retina

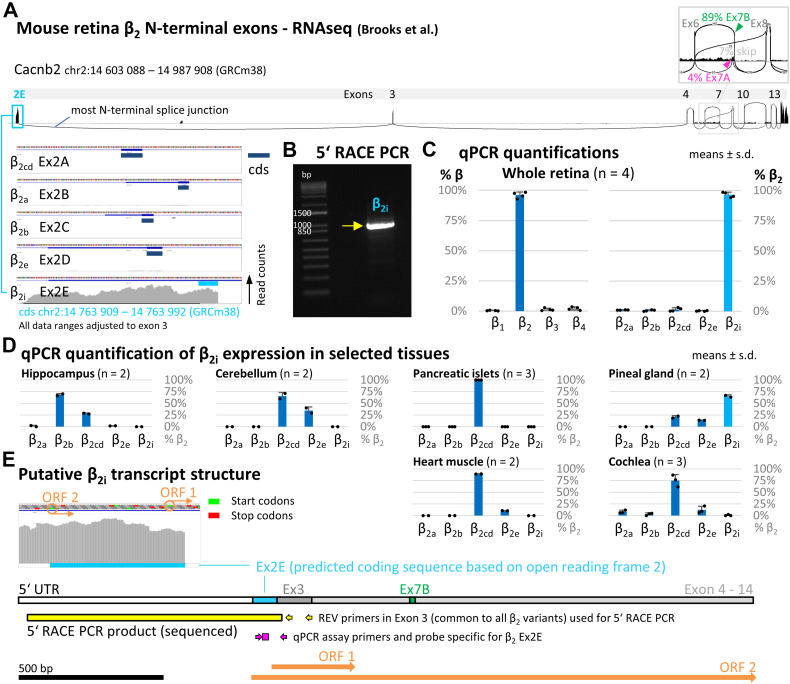

Since RNA-Seq is one of the most powerful tools to reveal the complexity of mRNA transcripts, we screened publicly available RNA-Seq data of wildtype mouse retina (12) for alternatively spliced exons of the main Cavβ subunit isoform of the retina, β2, using Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) visualization of mapped reads. In line with previous studies that found predominant expression of alternative exon 7B in human retina β2 (11) RNA-Seq data suggested that also in mouse retina exon, 7B inclusion was predominant over inclusion of exon 7A (Fig. 1A, inset; predominance based on the numbers of splice junction–mapping reads upstream and exon-mapping read counts). Similarly, exon 7B inclusion was predominant in rod and cone photoreceptors as well as rod bipolar cells (Fig. S1A) suggesting the same splice pattern of the β2 HOOK region in these cell types. However, we were surprised to discover a novel alternative splice pattern at the distal N-terminus. Unexpectedly, splice junction–mapping reads at the N-terminus of β2 did not link exon 3 (common to the known N-terminus splice variants (5)) to upstream exons of any known canonical β2 splice variant. Instead, all reads showing splicing upstream of exon 3 mapped to a genomic region for which no protein-coding exons were annotated (Fig. 1A). Closer inspection of this genomic region revealed a splice donor site right after the 3′ end of the unknown sequence, but no splice junction–mapping reads further upstream, suggesting that this sequence constitutes a novel first exon of a β2 splice variant transcript. We named this sequence exon 2E and the resulting novel Cavβ2 subunit β2i, in line with the established exons 2A to 2D of Cavβ2a–e and the nomenclature of described Cavβ2 variants (5).

Figure 1.

RNA-Seq data evidence for a novel N-terminus splice variant of Cavβ2in mouse retina.A, RNA-Seq data from mouse retina suggested splicing of a single β2 N-terminus variant upstream of canonical exon 3. The lack of both splice junction–mapping reads connecting to canonical exons 2A–2D and reads mapping to these exons indicated predominant splicing of the novel putative exon, which we named exon 2E. We called the putative β2 splice variant containing this novel exon β2i. Predominant inclusion of Ex7B (89% of splice junction–mapping reads downstream of Ex6) over Ex7A was also evident. B, seminested 5′-RACE PCR yielded an N-terminal sequence upstream of exon 3 containing exon 2E (arrow-marked product, verified by sequencing). C, quantitative PCR (qPCR) quantification showed near-exclusive expression of the novel N-terminal sequence variant β2i in mouse retina (β2cd assay detects both variants). D, qPCR quantification revealed dominant expression of β2i in pineal gland but not in a selection of other tissues. E, the sequence of Ex2E contains start codons for two potential ORFs. ORF 2 is in-frame with Ex3–Ex14 and thus yields a complete β2 transcript. Based on ORF 2, we predicted the putative coding sequence of Ex2E with a long 5′-UTR. The 5′-RACE PCR product and primers used, as well as the custom qPCR assay location, are marked. RACE, rapid amplication of cDNA.

In-frame translation with exon 3 was predicted to lead to an ORF with a short coding sequence (cds; location chr2: 14,763,909–14,763,992 [GRCm38/mm10]) of exon 2E (84 bp) and a long 5′-UTR. We confirmed experimentally that exon 2E constitutes the 5′-end of a transcript in mouse retina by 5′-rapid amplication of cDNA end (RACE) PCR (Fig. 1B) using full-length mouse retinal complementary DNA (cDNA) and amplifying the 5′ end of β2 with primers in canonical exon 3 in a seminested approach. The PCR product was verified by sequencing and corresponded to exon 2E with a long 5′-UTR spliced to exon 3, as predicted from RNA-Seq. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis confirmed β2 as the major Cavβ isoform expressed in mouse retina and showed that exon 2E defines the 5′ cds of retinal β2 almost exclusively (Fig. 1C). The exclusive expression of β2i held equally true when we analyzed cell type–specific RNA-Seq data of rod and cone photoreceptors as well as rod bipolar cells (Fig. S1A), and we could confirm the predominance of exon 2E/β2i in these cell types experimentally by qPCR on fluorescence-activated cell sorting–purified cell populations (Fig. S1B). Thus, RNA-Seq data and our qPCR experiments provided substantial evidence that β2i is the major β2 variant in all ribbon synapse–bearing cell classes in mouse retina. Similarly, we found that the homologous sequence of exon 2E also likely predominates the N-terminus of β2 in human, rhesus monkey, and rat retina (Fig. S2), suggesting conservation of β2i as the major retinal β2 variant in mammals (see evolutionary conservation of homologous sequences in Fig. S4). We quantified β2i expression by qPCR in nonretinal tissues (pineal gland, pancreas, heart muscle, and cochlea) and brain regions (cortex, cerebellum, striatum, and hippocampus), among which only pineal gland showed substantial expression (Figs. 1D and S3). This suggests that β2i in mouse is largely specific for retina and pineal gland, which are closely related in their gene expression patterns (13). We outlined the putative transcript structure of β2i (Fig. 1E) with two potential ORFs (see zoom-in of RNA-Seq visualization) of which ORF 2 (in-frame with exon 3) yields a complete β2 transcript with the short cds of exon 2E described previously and a long 5′ UTR with predominant inclusion of exon 7B.

Transcript structure and predicted protein sequence of β2i show distinct N-terminus features

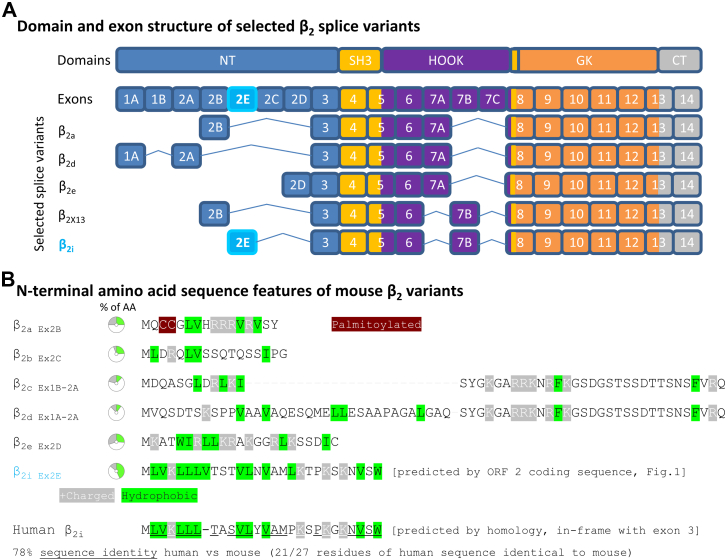

The overview of the exon structure and encoded domains of selected β2 splice variants and β2i (Fig. 2A) shows that β2i has highest similarity with β2X13, containing exon 7B instead of exon 7A, albeit with a different N-terminus (5). A sequence comparison of the established β2 splice variants with the predicted N-terminal amino acid sequence of β2i (Fig. 2B) showed that β2i differs in several relevant features that determine crucial aspects of β2 function like interaction with the plasma membrane (14). First, there are no cysteines in β2i, and therefore S-palmitoylation, which is necessary for β2a membrane association (3, 8, 9, 15, 16), is not expected (dark red in Fig. 2B). Moreover, the β2i sequence shows only few positively charged amino acids (similar to β2b–d, gray in Fig. 2B), which are required for β2e membrane association (10). However, β2i contains a striking accumulation of hydrophobic amino acids that are especially concentrated at the very N-terminal end (green in Fig. 2B). Thus, the β2i N-terminus by far exceeds the hydrophobicity (43% of exon 2E-encoded residues belong to the most hydrophobic amino acids: ILVFW) of the N-termini of known splice variants (10–26%). The hydrophobic character is preserved in human β2i (predicted from homologous sequence), which shows high overall sequence similarity with mouse β2i (78% sequence identity). High evolutionary conservation of predicted β2i sequence features was indeed found across mammalian and nonmammalian vertebrate species (Fig. S4) including, but not limited to, the strongly hydrophobic character.

Figure 2.

β2splice variant exon composition and N-terminal amino acid sequence features.A, comparison of selected β2 splice variants and β2i exon composition (based on the RNA-Seq evidence of predominant exon 7B inclusion). B, the predicted N-terminal sequence of β2i contains no cysteines (see β2a) and no accumulation of charged residues (see β2e) but features extraordinarily high hydrophobicity (43% of residues). The predicted human β2i sequence (based on RNA-Seq evidence of exonic sequence and conceptual translation in-frame with exon 3) has high sequence identity to mouse β2i, including the hydrophobic residues.

Biophysical properties of Cav1.4 complexes with β2i

We studied the basic functions of β subunits for this splice variant, namely the modulation of VGCC current properties. We recorded Ca2+ currents from tsA-201 cells heterologously expressing human Cav1.4 α1 together with α2δ-4 and different β2 subunits: β2X13, β2a, and β2d in comparison to β2i. We have selected these Cavβ subunits for the comparison because the membrane-associated β2X13 and β2a have been proposed to be dominantly expressed in the retina and β2X13 shares inclusion of exon 7B with β2i, making it the closest match only differing in the N-terminal sequence. β2d served as reference for a nonmembrane-associated variant.

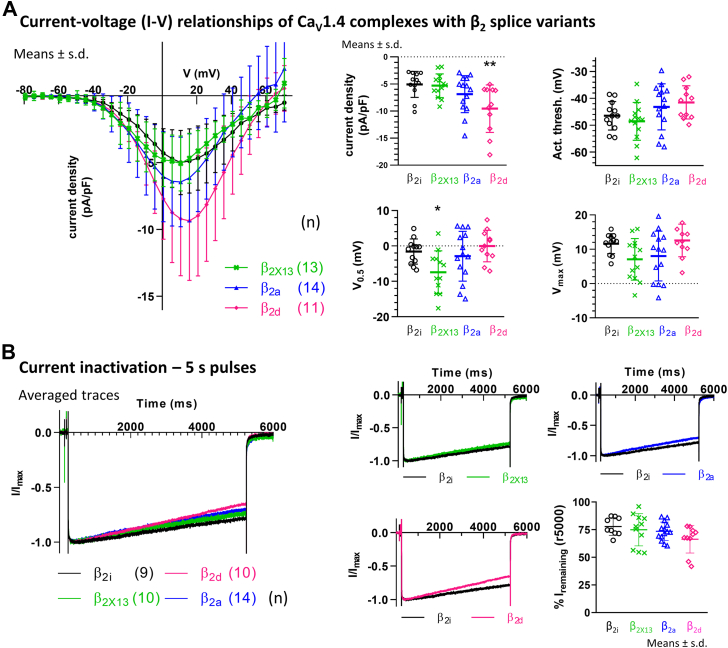

As shown in plots of current–voltage (I–V) relationships (Fig. 3A and see Table 1 for parameters), current densities of Cav1.4 complexes with β2i were smaller than with β2d (p = 0.004) but not significantly different from β2a (p = 0.344) or β2X13 (p = 0.996). The activation threshold determines the range where channels begin to open and was defined as the voltage where currents reached 5% of the maximal current. Activation threshold with β2i was similar as with β2X13, β2a, and β2d (p = 0.797; p = 0.483; p = 0.222, respectively). By contrast, in the presence of β2i, voltage dependence of activation properties of Cav1.4, determined by the voltage of half-maximal currents (V0.5) and maximal currents (Vmax), was partly right-shifted in comparison to β2X13 (p = 0.034; V0.5 and p = 0.119; Vmax) yet similar to β2a (p = 0.876; V0.5 and p = 0.251; Vmax) and β2d (p = 0.842; V0.5 and p = 0.955; Vmax). The statistics employed were one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons to β2i.

Figure 3.

Electrophysiology of calcium currents in Cav1.4 complexes with β2variants. β2 variants were coexpressed in tsA-201 cells together with Cav1.4 and α2δ-4. Currents were recorded in 15 mM Ca2+. A, current densities of Cav1.4 complexes with β2i were smaller than with β2d but not significantly different from β2X13 or β2a. The activation threshold was comparable among the variants tested. The voltage dependence (V0.5 but not Vmax) with β2i was partly right-shifted in comparison to β2X13. There was no difference in the voltage dependence between β2i and β2a or β2d (for details, see Table 1 and text). B, normalized currents during a 5 s pulse to Vmax. Current inactivation with β2i during the 5 s pulse was not significantly different from β2X13 or β2a but showed a tendency to slower inactivation than with β2d (see text for details). Statistics: one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons to β2i.

Table 1.

I–V properties of Cav1.4 with α2δ-4 and different β2 variants

| β2 variant (no. of recordings) | Current density (pA/pF) | Activation threshold (mV) | V0.5 (mV) | Vmax (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β2i (12) | −5.074 ± 2.385 | −46.457 ± 5.323 | −1.565 ± 3.539 | 11.616 ± 2.913 |

| β2X13 (13) | −5.306 ± 2.182 | −48.531 ± 7.013 | −7.406 ± 6.015∗ | 7.063 ± 6.046 |

| β2a (14) | −6.880 ± 3.429 | −43.134 ± 8.586 | −2.885 ± 7.018 | 8.017 ± 7.255 |

| β2d (11) | −9.555 ± 4.392∗∗ | −41.487 ± 6.164 | −0.022 ± 4.455 | 12.575 ± 4.742 |

Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistics: one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons to β2i.

Abbreviations: V0.5, half maximal voltage of activatio; Vmax, voltage of maximal current influx.

Significance levels of p < 0.05 or p < 0.01 are denoted by a single or double asterisk, respectively.

We measured Ca2+ current inactivation during prolonged depolarizations, for which all Cavβ2 subunits supported slowly inactivating Cav1.4 currents (Fig. 3B). Note, that despite recording with Ca2+ as charge carrier, Ca2+-dependent inactivation is absent in Cav1.4 (17), and thus, the current inactivation reflects only VDI properties. We measured Cav1.4 inactivation as the fractional remaining current amplitude at the end of a 5-s test pulse to Vmax. Remaining currents were comparable between β2i (77.91% ± 8.01%) and β2X13 (74.98% ± 14.60%; p = 0.877) as well as β2a (73.54% ± 8.31%; p = 0.668) and showed a tendency to reduced inactivation with β2i compared with β2d (66.37% ± 12.49%; p = 0.073; means ± SD; one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons to β2i). Thus, current inactivation properties with β2i were generally similar to the membrane-associated variants β2X13 and β2a. This biophysical characteristic could be consistent with a potential membrane association of β2i that might underlie slow inactivation, but differentiation in slowly inactivating Cav1.4 was limited.

Currents in Cav1.2 complexes with β2i are slowly inactivating

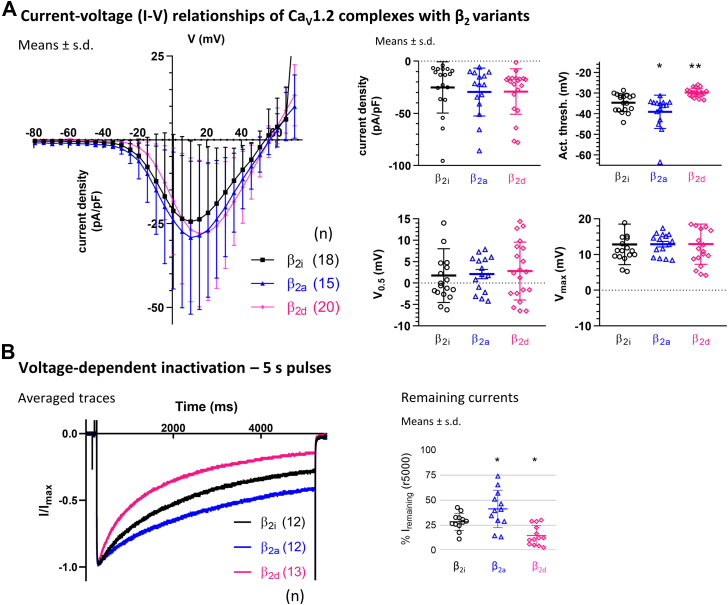

We characterized inactivation properties also with Cav1.2 with the aim of achieving a more pronounced difference in VDI between membrane-associated (β2a for comparison) and nonmembrane-attached (β2d for comparison) β2 variants compared with the slowly inactivating Cav1.4. We chose Cav1.2 because it supports well-studied VDI kinetics (18, 19). We measured Ba2+ currents, to exclude Ca2+-dependent inactivation, through Cav1.2 in complex with α2δ-1 and β2 variants. The I–V relationships (Fig. 4A, and see Table 2 for parameters) showed that current densities of Cav1.2 complexes with β2i were not significantly different from β2d (p = 0.818) or β2a (p = 0.812). The activation threshold with β2i was right-shifted compared with β2a (p = 0.032) but left-shifted compared with β2d (p = 0.009). The voltage-dependent activation properties of Cav1.2 with β2i were comparable in Vmax and V0.5 with β2a (p = 0.979; V0.5 and p = 0.999; Vmax) and β2d (p = 0.803; V0.5 and p = 0.999; Vmax).

Figure 4.

Electrophysiology of currents in Cav1.2 complexes with β2variants. β2 variants were coexpressed in tsA-201 cells together with Cav1.2 and α2δ-1. Currents were recorded in 15 mM Ba2+. A, current densities were comparable with β2i, β2d, and β2a. Activation thresholds were different from β2i with β2d (right-shifted) and with β2a (left-shifted), whereas voltage dependence (V0.5 and Vmax) was comparable throughout (for details, see Table 2 and text). B, normalized Ba2+ currents during 5 s pulses to Vmax. Voltage-dependent inactivation with β2i during the 5 s pulse was faster than with β2a but slower than with β2d (see text for details). Statistics: one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons to β2i.

Table 2.

IV properties of Cav1.2 with α2δ-1 and different β2 variants

| β2 variant (no. of recordings) | Current density (pA/pF) | Activation threshold (mV) | V0.5 (mV) | Vmax (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β2i (18) | −25.15 ± 24.55 | −34.62 ± 4.34 | 1.75 ± 6.29 | 12.85 ± 5.69 |

| β2a (15) | −29.51 ± 22.92 | −39.05 ± 8.11∗ | 2.11 ± 4.14 | 12.88 ± 3.01 |

| β2d (20) | −29.12 ± 19.41 | −29.70 ± 2.19∗∗ | 2.83 ± 6.79 | 12.90 ± 5.58 |

Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistics: one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons to β2i.

Abbreviations: V0.5, half maximal voltage of activation; Vmax, voltage of maximal current influx.

Significance levels of p < 0.05 or p < 0.01 are denoted by a single or double asterisk, respectively.

Remaining currents at the end of 5-s pulses (Fig. 4B) with β2i (28.4% ± 8.5%; means ± SD) were lower than with membrane-associated β2a (41.2% ± 18.7%; p = 0.041) but significantly higher than with cytosolic β2d (14.7% ± 9.9%; p = 0.024). The reduced VDI in comparison to β2d suggested a potential membrane attachment of β2i.

β2i is membrane associated and exhibits distinct intrinsic localization properties

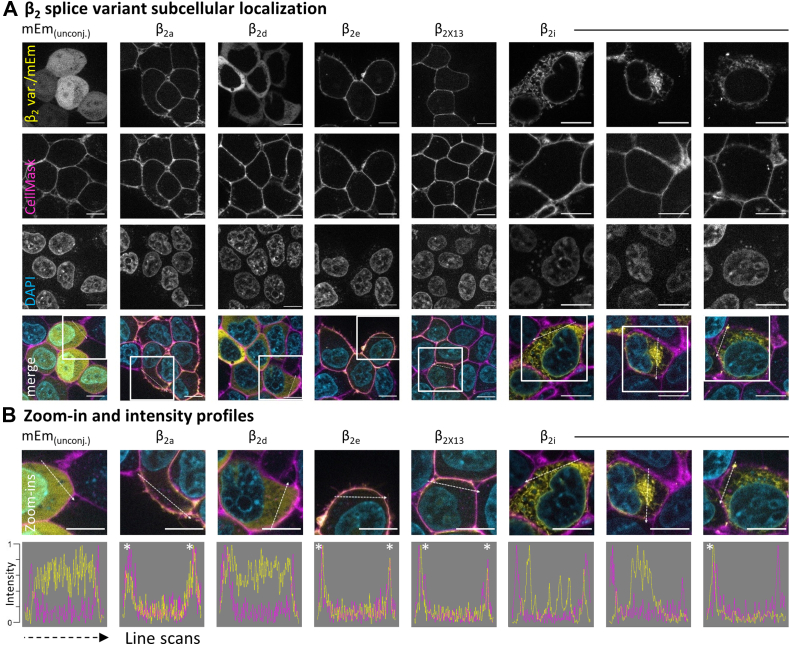

The functional properties that β2i subunits confer to Cav1.4 and Cav1.2 channel complexes were consistent with a potential membrane association of β2i subunits independent of the channel complex. Therefore, we tested membrane targeting of β2i by heterologously expressing mEmerald (mEm)-tagged β2 subunits in the absence of a Cavα1 in tsA-201 cells. We assessed the subcellular localization of these tagged β2 variants using the mEm fluorescence together with the plasma membrane stain CellMask (Fig. 5A) in live cells. Line scan analysis provided cross sections through the fluorescence intensity profiles, which revealed colocalization of mEm with the CellMask fluorescence in variants with membrane association (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

β2isubcellular localization differs from known splice variants.A, β2 splice variants were C-terminally tagged with the fluorescent reporter mEmerald (mEm) and expressed in tsA-201 cells without Cavα1 subunits to track their intrinsic membrane association properties. The β2 subunit localizations (visualized by conjugated mEm fluorescence) were overlapping with the plasma membrane marker CellMask in β2a, β2e, and β2X13, whereas β2d was localized mostly intracellularly, similar to unconjugated mEm. For β2i, we observed three patterns of localization (left to right): intracellular (web-like), intracellular (accumulated), and membrane colocalized. Notably, in all three patterns, the localization of β2i appeared clustered. B, zoom-ins of the regions marked above. Line scans provided intensity profiles of mEm and CellMask, highlighting the overlap of β2 subunit–conjugated mEm fluorescence with the plasma membrane (marked by ∗ in line scans) in β2a, β2e, β2X13, and β2i (right-most panel). The scale bars represent 10 μm.

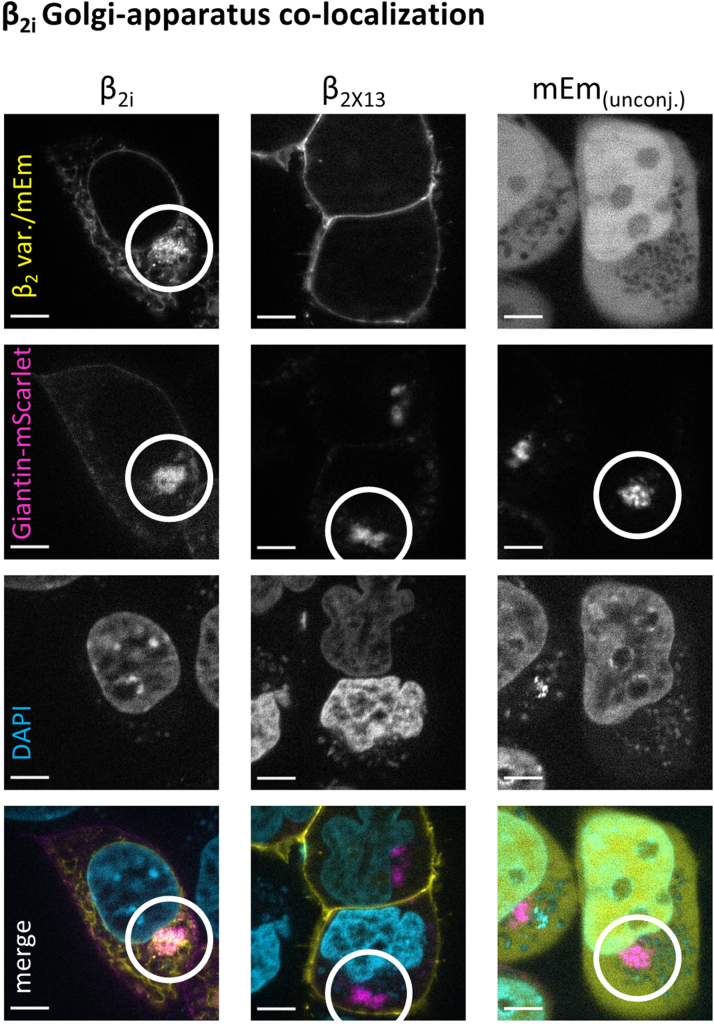

The known membrane-anchored variants β2a, β2X13, and β2e associated with the plasma membrane, whereas β2d was located in the cytosol of the cells, as was unconjugated mEm that was used as control. Unconjugated mEm was also seen in the nucleus, which is common for GFP derivatives (20). By contrast, β2i showed subcellular distributions that differed from the other β2 splice variants and could be observed in three major patterns. First, β2i was localized perinuclear and in a web-like manner throughout the cell volume, reminiscent of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Second, β2i accumulated in a single dense cluster within the cytoplasm. This dense intracellular accumulation was confirmed as the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 6) by coexpression of a Golgi marker (Giantin-mScarlet) with mEm-tagged β2i and β2X13 or with unconjugated mEm. Accumulation of mEm fluorescence in the Golgi apparatus did not occur with β2X13 or with mEm alone showing a dependence of the Golgi accumulation on the β2i N-terminus. Third, we found β2i in clusters overlapping with the plasma membrane marker. These clusters of β2i at the membrane were numerous and very commonly seen while focusing through the convex shape of the cell surface or bottom part of cells adhering to the coverslip (see example Video in supporting information). Still, for colocalization with the membrane marker, only clusters within the optical membrane cross-section (i.e., perpendicular to the coverslip surface) were used. The three localization patterns were not mutually exclusive as reticular and Golgi localization often occurred in parallel with membrane colocalization. In addition, β2i consistently exhibited a clustered appearance as opposed to the largely homogeneous cytosolic (β2d) or membrane-localized (e.g., β2X13) distributions of the other β2 variants. Yet, with low frequency, a more homogenous cytosolic localization of β2i could also be observed (1–2% of fluorescent cells). The membrane colocalization was illustrated in line scans showing overlap between CellMask fluorescence profiles and mEm (∗ in Fig. 5B), highlighting the overlay of the membrane and the β2i cluster in the example image. In summary, we observed a clustered localization of β2i from a reticular appearance through the Golgi apparatus to widespread dense clusters at the plasma membrane.

Figure 6.

β2iaccumulation in the Golgi apparatus. The intense intracellular accumulation of β2i colocalized with the Golgi apparatus, revealed by colabeling with a Golgi marker (cotransfected plasmid coding for Giantin-mScarlet) while clustering of mEm fluorescence at the Golgi was not observed with β2X13 or unconjugated mEmerald. Scale bars represent 5 μm.

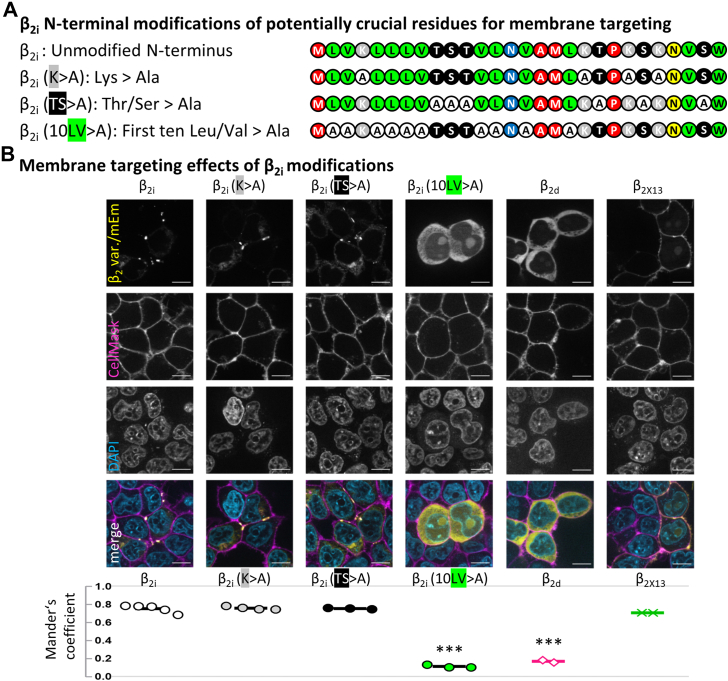

Since β2i showed clear membrane association, we set out to determine the impact of different amino acids within the N-terminus on the subcellular localization. As the mouse β2i sequence contains no cysteines or glycines as post-translational palmitoylation targets, we considered three other possibilities that might explain the membrane localization of the protein: 1—positively charged lysine residues that interact with negatively charged phospholipids (as in β2e (10)), 2—serine and threonine residues as potential targets for other types of post-translational modification (acylated Ser/Thr as myristoylation/palmitoylation targets, similar to β2a (8)), or 3—direct interaction of the highly hydrophobic N-terminus with the lipid bilayer of the plasma membrane itself.

To test the role of these three candidate mechanisms, we cloned modifications that contained alanine substitutions of the respective residues (Fig. 7A) and expressed them in tsA-201 cells. While the lysine modification (K>A) and serine/threonine modification (TS>A) neither altered the clustering nor the membrane localization, substitution of hydrophobic residues (LV>A) lead to a homogeneous fully cytosolic localization (Fig. 7B), similar to β2d (used as cytosolic control, with β2X13 as membrane-associated control). For quantification of membrane colocalization, cells were imaged 48 h post-transfection, during which β2i membrane clusters typically grew in size, and regions of interest were selected around visually identified mEm clusters (for β2i) or similarly sized image sections from the other variants (see example image sections in Fig. S5A). The degree of colocalization of the expressed β2 splice variants with the plasma membrane was quantified by the Mander’s coefficient (MC) of colocalization between mEm and CellMask signals (percent of mEm-positive pixels overlapping CellMask-positive pixels, thresholding example see Fig. S5B) for β2i, β2i modifications, β2d and β2X13 (Fig. 7B, bottom). β2i showed a high degree of membrane colocalization (MC = 0.761) similar to the β2i K>A and TS>A modifications (MC = 0.766; p = 0.997 and MC = 0.755; p = 0.999, respectively) and comparable to β2X13 (MC = 0.710; p = 0.216), whereas the β2i 10LV>A modification exhibited a significantly reduced membrane colocalization (MC = 0.109; p < 0.001), close to cytosolic β2d (MC = 0.170; p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons to β2i).

Figure 7.

β2imembrane targeting depends on hydrophobicity.A, we cloned three N-terminus modifications of β2i, replacing charges (K>A), threonines/serines (TS>A), or the first ten hydrophobic residues leucine/valine (10LV>A) by alanine substitution to identify crucial residues for the membrane-targeting property of β2i. B, the K>A and TS>A modifications showed an unchanged clustered appearance and apparent membrane localization. The 10LV>A modification showed a cytosolic and homogeneous distribution, comparable to the localization of β2d. The established membrane-localized variant β2X13 was used for comparison. Scale bars represent 10 μm. We calculated the Mander's coefficient (fraction of mEmerald [mEm] pixels that colocalizes with CellMask pixels), showing high membrane colocalization of β2i, the K>A and TS>A modifications, and in β2X13, while the LV>A modification exhibited loss of membrane colocalization with Mander’s coefficient values comparable to the cytosolic β2d (see text for details). Statistics: one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons to β2i.

We investigated in more detail whether the number or the position of hydrophobic residues are essential for the maintenance of clustering and membrane association by cloning three additional modifications, each substituting only a subset of five hydrophobic amino acid residues. We replaced 1—the first five hydrophobic residues (5LV>A first), 2—the first five odd-numbered hydrophobic residues (5LV>A odd), or 3—the first five even-numbered hydrophobic residues (5LV>A even). All three modification subsets altered the subcellular location of β2i in the same way as the full set of β2i hydrophobicity removal (10LV>A), with no cluster formation (and no reticular distribution pattern or accumulations at the Golgi apparatus) and no detectable localization at the membrane (Fig. S6). In summary, the removal of subsets of five hydrophobic residues was sufficient to abolish both cluster formation and membrane targeting of β2i, whereas charged Lys residues and Ser/Thr residues appeared to have no role in localization or clustering.

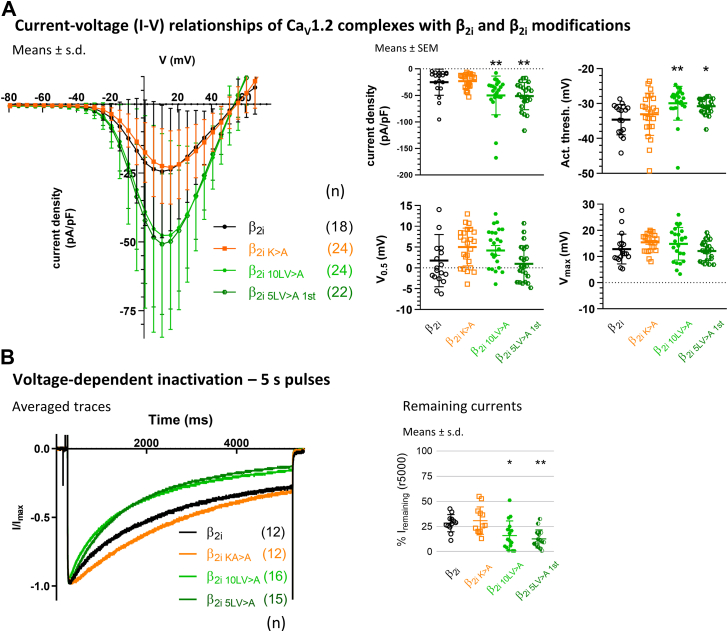

Biophysical properties of β2i modifications match their membrane localization

We measured the biophysical effects of β2i N-terminus modifications on Ba2+ currents with Cav1.2 coexpressed with α2δ-1 and β2i modifications to determine whether the membrane-localization behavior also impacts the biophysical properties. The I–V relationships (Fig. 8A, and see Table 3 for parameters) showed that the K>A modification did not alter current density (p = 0.990), but currents were remarkably larger with the hydrophobicity modifications 10LV>A (p = 0.009) and 5LV>A first (p = 0.007). The Cav1.2 activation threshold was not significantly shifted with the K>A (p = 0.564) but was significantly more depolarized with 10LV>A (p = 0.005) and 5LV>A first modifications (p = 0.030), akin to β2d. The voltage dependence of activation properties of Cav1.2 with β2i, on the other hand, were comparable in V0.5 and Vmax with the K>A (p = 0.115; V0.5 and p = 0. 219; Vmax), 10LV>A (p = 0.300; V0.5 and p = 0. 398; Vmax), and 5LV>A first modifications (p = 0.929; V0.5 and p = 0. 933; Vmax).

Figure 8.

Electrophysiology of currents in Cav1.2 complexes with β2imodifications. β2i modifications were coexpressed in tSA-201 cells together with Cav1.2 and α2δ-1. Currents were recorded in 15 mM Ba2+. A, the K>A modification did not change current density compared with unmodified β2i, but current densities of the hydrophobicity modifications 10LV>A and 5LV>A first were much larger. Activation thresholds were right-shifted from unmodified β2i with the hydrophobicity modifications, whereas voltage dependence (V0.5 and Vmax) was comparable throughout (see Table 3 and text for details). B, normalized Ba2+ currents during 5 s pulses to Vmax. Voltage-dependent inactivation with β2i during the 5 s pulse was unchanged in the K>A modification, but the hydrophobicity modifications 10LV>A and 5LV>A first showed significantly faster inactivation, as expected for a loss of membrane association (see text for details). Statistics: one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons to β2i.

Table 3.

IV properties of Cav1.2 with α2δ-1 and β2i modifications

| B2i modification (no. of recordings) | Current density (pA/pF) | Activation threshold (mV) | V0.5 (mV) | Vmax (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β2i unmodified (18) | −25.15 ± 24.55 | −34.62 ± 4.34 | 1.75 ± 6.29 | 12.85 ± 5.69 |

| β2i K>A (24) | −23.21 ± 13.38 | −33.08 ± 6.03 | 5.04 ± 4.54 | 15.40 ± 3.37 |

| β2i 10LV>A (24) | −50.06 ± 36.36∗∗ | −29.92 ± 4.85∗∗ | 4.21 ± 5.75 | 14.85 ± 6.21 |

| β2i 5LV>A (22) | −51.45 ± 25.53∗∗ | −30.80 ± 2.29∗ | 0.97 ± 4.36 | 12.13 ± 3.73 |

Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistics: one-way ANOVA multiple comparisons to unmodified β2i.

Abbreviations: V0.5, half maximal voltage of activation; Vmax, voltage of maximal current influx.

Significance levels of p < 0.05 or p < 0.01 are denoted by a single or double asterisk, respectively.

VDI was measured as the remaining current at the end of 5 s pulses to Vmax (Fig. 8B). Compared with β2i remaining currents (28.4% ± 8.5%; means ± SD), the K>A modification had an unchanged inactivation (30.9% ± 13.6%; p = 0.912), whereas remaining currents with 10LV>A (16.1% ± 14.5%; p = 0.023) and 5LV>A first modifications (12.8% ± 8.9%; p = 0.004) were significantly lower. In summary, we found comparable inactivation for β2i and the β2i K>A modification, whereas the β2i 10LV>A and β2i 5LV>A first modifications exhibited significantly increased inactivation, reminiscent of cytosolic β2d (Fig. 4). Thus, the biophysical properties matched the loss of membrane localization by the hydrophobicity modifications.

Structural investigation elucidates potential framework for β2i N-terminus membrane association

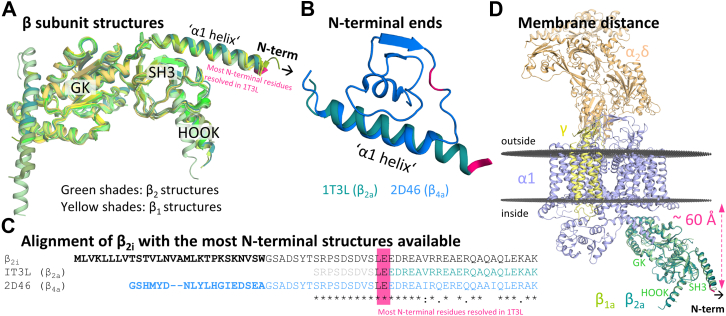

We sought to investigate the N-terminus on a structural level to get further insights into the potential molecular mode of action. However, a detailed survey of available β2 structures from different species revealed that none of them contained the N-terminus (Fig. 9A). This was due to the fact that the first residues were deleted in the constructs used for structure elucidation because of solubility issues (21), and in addition, the N-termini of β subunits were generally considered an intrinsically disordered region (22, 23). Similarly, in experimental complexes of the related β1 isoform where full-length proteins were used for structure generation, the N-terminus remains unresolved (Fig. 9A) (24, 25). In Figure 6, the most N-terminal residues resolved in the rabbit β2a structure (Protein Data Bank [PDB] entry: 1T3L (26)) LE33–34 were highlighted in magenta for reference. The only structural insights available of more N-terminal residues were provided by an NMR structure of the human β4a subunit (PDB entry: 2D46 (27)), which was solved under low temperature conditions to reduce protein motion. Compared with the partially resolved N-terminus of β2a, a part of the β4a structure shows a shorter “α1 helix” and the homologous residues of this part (LEEDREAI in β4a) exhibit a loop conformation instead (Fig. 9, B and C). Please note that the mouse β2i N-terminus shows no homology in the alignment with the human β4a N-terminus upstream of the highly conserved sequence region (upstream of GSADSYT) and is ten amino acids longer (Fig. 9C). Taken together, this indicates that the N-termini of β subunits are highly flexible and thus intrinsically difficult to resolve. Given the key role of β subunit variant N-termini in membrane anchorage, we next investigated the approximate spatial orientation of the N-terminus in relation to the membrane. For this purpose, we aligned the membrane-embedded rabbit Cav1.1 in complex with the auxiliary β1a, γ, and α2δ subunits (PDB entry: 6JPA (24)), which we downloaded from the Orientations of Proteins in Membranes database (28) (https://opm.phar.umich.edu/), to the reference rabbit β2a structure (PDB entry: 1T3L (26)) (Fig. 9D). We chose to use rabbit Cav1.1 in complex with β1a for a new alignment of β2 because the location and orientation of the β subunit was much more reliable in this structure than in the previous published structure where β2 was docked as a rigid body on a less well-resolved β1a (29). Our analysis suggests that the 44 most N-terminal residues of the β2i subunit, upstream of the resolved reference rabbit β2a structure (compare Fig. 9C), would need to span ∼ 60 Å to contact the membrane. In the absence of a solved structure, more substantial insights into potential mechanisms that underlie the described characteristics of β2i were not achievable. Structure prediction tools (including AlphaFold2 (30)) suggested a potential alpha helical conformation at the novel N-terminus (Fig. S7) with a roughly 70 Å-long intrinsically disordered loop connecting this helix to the conserved “α1 helix.”

Figure 9.

Structural analysis.A, alignment of available β2 (green shades, Protein Data Bank [PDB] entries: 1T0H, 1T0J (21), 1T3L, 1T3S (26), 3JBR (29), 4DEX, 4DEY (67), 5V2P, and 5V2Q (67)) and full-length β1 (yellow shades, PDB entries: 6JPA and 6JPB (24)) structures revealed missing N-termini upstream of the first α-helix (called “α1 helix”) throughout. B, in the structure alignment of rabbit β2a (green, PDB entry: 1T3L (26)) and human β4a (blue, PDB entry: 2D46 (27)), the “α1 helix” structure is partly conserved but shorter in the β4a structure (see homologous residues LE in magenta). C, sequence alignment of the mouse β2i splice variant with rabbit β2a (PDB entry: 1T3L (26)) and human β4a (PDB entry: 2D46 (27)) constructs. Nonconserved parts in bold, nonresolved parts in the 1T3L structure in light gray. D, membrane-embedded Cav1.1 (α1, violet) in complex with auxiliary subunits β1 (light green), α2δ (orange), and γ (yellow, PDB entry: 6JPA (24)) was aligned to rabbit β2a (dark green, PDB entry: 1T3L (26)) and revealed a distance from the most N-terminal residues to the inner leaf of the membrane (gray disc) of ∼60 Å. For reference, the most N-terminal residues still resolved in the rabbit β2a structure (PDB entry: 1T3L (26)) are highlighted in magenta in all panels.

Discussion

Transcript

We introduced β2i here as a novel Cavβ2 splice variant for which we provided ample and consistent experimental evidence of its exon composition, splicing pattern, and expression. While there has been no clear recognition in the literature of the existence and nature of the novel N-terminus splice variant we describe here, there have been some evidence and annotated sequences published that correspond to β2i. In a recent publication, alternative transcript start sites specific to mouse rod photoreceptors were mapped based on chromatin signatures that revealed a novel start site for β2. This novel start site is indeed localized at the β2i N-terminus, which was confirmed by PCR using primers in the 5′UTR of β2i and exon 3 in the study (31). The Ensembl database (https://www.ensembl.org) also contains a mouse Cacnb2 transcript variant (classified as nonprotein-coding) that is composed of the 5′UTR + exon 2E of β2i spliced to canonical exons 3 to 5 (incomplete transcript), thus containing the exon 2E–exon 3 splice junction we described here (Ensembl transcript Cacnb2-205; ENSMUST00000137746.8). The Ensembl entry cites two sources of supporting information from high-throughput sequencing studies (RIKEN, ENA accession no.: AK044560.1; National Institutes of Health, ENA accession no.: BQ951456.1; https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/), which both used cDNA generated from mouse retina tissue samples. Thus, the pre-existing evidence for β2i variant expression originated in mouse retina.

National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) also contains entries corresponding to β2i, based on early whole genome shotgun sequencing data from both mouse (β2 isoform CRA_d; GenBank accession no.: EDL08070.1; conceptual translation, partial sequence/β2 isoform X5; GenBank accession no.: XM_036157788; predicted by automated computational analysis) and human (β2 isoform CRA_b; GenBank accession no.: EAW86194.1; conceptual translation). So, while there is prior evidence that correctly identified the alternative transcript start site or determined the splicing of exon 2E with exon 3, this has not been followed by description and recognition of this transcript as a verified alternative N-terminus variant with respective annotation.

β2i seems to have a rather tissue-selective expression pattern compared with the canonical N-terminus variants, with predominance in the retina (both mouse and human) and pineal gland (which generally has a similar transcriptome as the retina) and otherwise no detectable expression in a number of other tissues that prominently feature β2 with a variety of the canonical variants. This might suggest a special role for β2i in the retina within ribbon synapse–bearing cell classes where we confirmed its predominant expression. Of note, there was no exon 2E expression detectable in whole cochlea cDNA, and thus, hair cell ribbon synapses might not contain Ca2+ channel complexes with β2i although this should be investigated in more detail with a focus on hair cells. Expression outside the retina context could be informative as a narrow retina-selective expression pattern might be related to a distinct functional feature of β2i compared with the more widespread expression of the established variants.

In addition to the novel N-terminus, β2 in the retina also predominantly contains the alternatively spliced exon 7B coding for a part of the HOOK domain, evident from the RNA-Seq data from whole retina as well as the cell type–specific data from rods, cones, and rod bipolar cells. A previous report determined the predominant splicing of exon 7B over 7A in human retina Cavβ2 (11), with an average 93.5% exon 7B inclusion versus 6.5% exon 7A. These numbers are close to the ratio of splice junction–mapping reads we observed for the splice junctions connecting exon 7A versus 7B to upstream or downstream exons. While the percentage of exon 7B inclusion from RNA-Seq data we present here has to be taken with a grain of salt, as quantifications based on few splice junctions are inherently variable, we consider this sufficient confirmation that also in mouse retina exon 7B inclusion strongly predominates in retinal Cavβ2 transcripts and, hence, the predominant N-terminal exon 2E at large combines with exon 7B to form splice variant β2i. Direct confirmation of the cosplicing of exon 2E with exon 7B within the same transcript is given by our cloning of the β2i cDNA sequence from exon 2E down to exon 10, including exon 7B. While being nonquantitative, this confirms the principal existence of exons 2E and 7B within the same transcript.

Primary protein sequence

The predicted cds of the β2i N-terminus contains two methionines, and translation initiation from the second methionine inside the predicted sequence cannot be excluded. Both potential start codons have a similarly weak Kozak sequence context (32) but evolutionary conservation is very high upstream of the second methionine, including full conservation of the first methionine, making the first in-frame methionine the likely translation start site. This notion has some support by the fact that our modifications of both the first five (5LV>A first) and the first five odd (5LV>A odd) hydrophobic residues fully changed β2i localization. Protein translation from the second methionine in these modifications would have an unchanged sequence and show unaltered localization, which we did not observe. Aside from the most apparent feature unique to the β2i N-terminus, its extraordinary hydrophobicity, the evolutionary comparison of predicted β2i homologs highlights also other structural features that are highly conserved. Among those are not only the lysines (charges) and the serines/threonines, which we examined here, but also a polar residue, a putative glycosylation site, a glycine residue, and some alanine/methionine/proline residues (also on the hydrophobic spectrum). The degree of conservation suggests the relevance of these structural features beyond the hydrophobicity we focused on here and thus are also potential targets for further studies.

Beyond the high similarity among predicted β2i orthologs, we found no other proteins with a strong homology to the N-terminal sequence. The most similar non-β subunit proteins revealed by a protein BLAST search (see Fig. S4B and supporting information for details) were bacterial transporters of the major facilitator superfamily proton symporters and ABC transporters (33). These protein families are generally flagged as integral plasma membrane proteins with multiple transmembrane domains, but structures of the homologous sequences are not available. With the limited sequence similarity of these bacterial proteins, however, knowledge about their structure would also not allow to extrapolate directly to β2i to gain reliable structural insights.

Biophysics

We hypothesized that the hydrophobic nature of the β2i N-terminus might support membrane interaction and thus, we compared the biophysical properties of Cav1.4 or Cav1.2 complexes with β2i with the most closely related member of the β2 family that associates with the membrane, β2X13, and its closest relative β2a, in comparison to cytosolic β2d. The low macroscopic Ca2+ current density of Cav1.4 complexes with β2i was in line with the two membrane-targeting variants β2X13 and β2a, whereas Ba2+ currents in Cav1.2 were no different with β2i than with either β2a or β2d. Besides direct effects that could account for the small currents, like reduced trafficking, lower open probability or single-channel conductance, expression of membrane-targeting variants also could favor survival of cells with smaller currents with Cav1.4 because of Ca2+ overload caused by more slowly inactivating channels. It has been reported that β2a confers increased open probability to heart ventricular myocyte L-type channels (34) and heterologously expressed Cav1.2 (35) (with unchanged single-channel conductance) leading to increased current densities. As we do not see larger current densities with β2a, a reduced survival of cells with larger noninactivating currents may curtail currents with β2a and perhaps also β2i. Yet, effects of β2i on open probability cannot be clearly deduced from macroscopic currents and should be determined with single-channel recordings.

All Cavβ subunits shift the voltage dependence of activation to more negative potentials (see Ref. (2)for overview), and β2i showed only minor differences from the other variants tested. Voltage dependence of activation was shifted less in the hyperpolarized direction with β2i compared with β2X13 with Cav1.4 and showed a less hyperpolarized activation threshold compared with β2a with Cav1.2. Thus, voltage dependence of activation was overall comparable across Cavβ2 variants tested here.

Support of slow current inactivation is the hallmark of membrane-anchored Cavβ2 variants, most prominently in β2a and β2e, where they show pronounced remaining currents during prolonged depolarizing steps (14). The Cav1.4 current inactivation properties with β2i were in line with the membrane-targeting variants, but showing only a tendency toward slower inactivation compared with β2d after 5 s. Cav1.4 itself already supports slowly inactivating currents (17) and, possibly, therefore we did not observe differences in the inactivation kinetics imposed by the Cavβ2 variants we measured, unlike those seen with other α1 isoforms (3, 36). In line with this notion, the effect of β2i on slowing inactivation with Cav1.2 was indeed consistent with membrane association. The dependence on membrane attachment is further supported by our measurements of VDI of β2i and β2i modifications in complex with Cav1.2. We showed slow inactivation for unmodified β2i and the K>A modification and increased inactivation for the hydrophobicity modifications 5LV>A first and 10LV>A, consistent with the membrane localization of β2i and β2i K>A and the cytosolic localization of the LV>A modifications.

The other factor to consider in functional aspects of β2i is the alternatively spliced HOOK region. Among the established Cavβ2 variants, only β2X13 and β2h (same N-terminus as β2d (5)) contain exon 7B, whereas the other variants express exon 7A. The shorter HOOK domains encoded by exon 7B (and its homologs that predominate in all other β isoforms) have been shown to contribute to increased inactivation (37), an effect also reported from Cav1.4 in complex with α2δ-4 and β2X13 (11). In our experiments, we did not see this difference in inactivation between β2a and β2X13, possibly because of the Cav1.4 variant we used, which contains a shorter exon 9 (38) and consequently a shorter intracellular I–II loop where the β binding site, the α-interacting domain, is located. The shorter loop might prevent the additive effect of the longer HOOK domain of β2a on slowing inactivation further compared with β2X13. The increased inactivation with Cav1.2 and β2i versus β2a is further evidence that the shorter HOOK domain of β2i curtails the slowing effect that membrane attachment has on inactivation. Thus, inactivation properties of β2i might resemble most those with β2X13 (both having shorter HOOK domains), that is, current inactivation with β2i likely is slowed down to a lesser extent than it could be with an exon 7A-encoded longer HOOK domain. Contrary to the commonly held notion that properties of retinal Cav1.4 complexes are tuned to the slowest possible current inactivation, this would rather suggest that a certain degree of inactivation of the Ca2+ current is indeed of functional relevance.

Subcellular localization

The experiments with fluorescently tagged Cavβ2 variants revealed a surprising intrinsic localization behavior of β2i. The localization of β2i did not match any of the known variants tested, which were either diffuse cytosolic (β2d) or diffuse membrane-associated (β2a, β2e, and β2X13) as shown previously (14). The localization of β2i appeared neither freely cytosolic nor diffuse but generally inhomogeneous. The perinuclear to web-like localization we observed most likely revealed β2i within the ER. Furthermore, β2i accumulated strongly to the Golgi apparatus, presenting there as dense clusters, and finally also localized in a clustered fashion at the plasma membrane.

In principle, it would be conceivable that the β2i N-terminus retains an interaction with the ER membrane at ER/plasma membrane junctions. However, in the heterologous expression without a Ca2+ channel, this would require a dual interaction of the N-terminus with both membranes to result in the plasma membrane localization we observed. In its native environment, for example, the photoreceptor terminal, β2i is unlikely to maintain both ER and plasma membrane interactions, as its binding partner Cav1.4 is strictly localized to synaptic ribbons, whereas the ER is more diffusely distributed within the terminals, too distal from ribbon structures to allow Cav1.4-bound β2i to interact (39, 40).

Curiously, we did not observe a similar labeling of putative ER or Golgi for β2a even at earlier time points post-transfection, though it should pass through the same trafficking pathways to reach the plasma membrane. Conversely, we still observed reticular and Golgi labeling at later time points with β2i, whereas the membrane-localized clusters had grown further in size. In principle, this could be caused by a delayed forward trafficking of β2i, for example, through ER- and/or Golgi-retention signals, but a delay in trafficking does not explain the clustered appearance on the membrane. While clusters of β2i in the transport pathway could for example be defined by dense packing during transport, a traffic delay in itself would not lead to clustering on the membrane. The other membrane-localized Cavβ2 variants did not start out as clusters that eventually filled up the membrane homogeneously but exhibited a diffuse membrane labeling also at earlier time points post-transfection.

The clustered appearance of β2i might be dependent on intermolecular interactions. While oligomerization is a known feature of Cavβ proteins, the clustering of β2i was clearly distinct also from β2X13 from which it differs only in the N-terminus. Yet, oligomerization of Cavβ subunits is thus far attributed to homodimerization via their SH3 domains (41) or to homo-oligomerization and hetero-oligomerization via their GK domains (42) with both domains also underlying intramolecular interactions (23). As β2i and β2X13 are identical except for the very N-terminus, the clustered appearance of β2i cannot be attributed to one of these known mechanisms. Oligomerization or clustering by direct interactions of the N-terminus has not been described for Cavβ subunits and, if indeed the case for β2i, would be a distinguishing feature.

An interesting point is also the potential interaction with other proteins. At present, the involvement of the Cavβ N-terminus in protein–protein interactions is an open question. Previously identified interactions of Cavβ subunits do not depend on the N-terminus. Small GTPases like RGK proteins or Rab proteins for example interact with Cavβ SH3/HOOK/GK domains either directly (40) or indirectly (43) via Rab3-interacting molecule proteins, and thus do not depend on the N-terminus of Cavβ subunits. Nonetheless, it will be an important avenue to explore whether the Cavβ N-terminus has roles beyond regulating intrinsic properties like membrane attachment.

For now, it is unclear which mechanism governs clustering of β2i as is the mechanism by which membrane targeting is achieved, besides the apparent requirement of hydrophobic residues at the N-terminus for both properties. We cannot rule out that, for example, clustering depends on prior membrane targeting. Generally, proteins that interact with the membrane are either integral/intrinsic (trans-)membrane proteins that stably integrate with the membrane or peripheral/extrinsic membrane proteins that can interact more transiently with spatial or temporal precision (see Ref. (44) for an overview). While the former require a long stretch of hydrophobic residues to span the membrane, often in the form of an α helix, membrane interaction of the latter can rely on four prototypical arrangements (44): 1—electrostatic interactions (as β2e), 2—lipidation (as β2a), 3—insertion of a hydrophobic stretch into the membrane, or 4—an amphipathic α helix parallel to the membrane surface (or, more generally, hydrophobic protrusions (45)). Hydrophobic residues therefore play important roles in several of these membrane interaction paradigms, proposing several possibilities for β2i membrane attachment with mechanisms based on hydrophobic characteristics.

Structure considerations

To elucidate the mechanism(s) behind membrane targeting and clustering, structure information about the N-terminus of β2i would be highly beneficial. However, the N-terminus is missing in most available experimentally determined structures (X-ray, cryo-EM) of any β subunit variant and thereby suggests a general challenge in resolving the most N-terminal structures. Possibly, it is the disordered and flexible nature of at least part of the N-terminal ends of β subunits that precluded the N-termini from structural resolution in published structures. In fact, only the β4a NMR structure (PDB entry: 2D46) contains a complete N-terminus, but this structure had to be resolved under special conditions, and it diverges on the length of the strongly conserved “α1 helix.” The lack of N-terminus structural information would be consistent with a disordered loop, as suggested by the AlphaFold2 structure prediction. A disordered and flexible loop as part of the N-termini of β2 variants could be behind the lack of experimentally determined structures because the predicted loop is formed in part by a sequence that is common to all β2 splice variants (GSAD…DSDV, upstream of the “α1 helix”), and thus a loop structure might be a common feature of the β2 N-terminus. Based on the AlphaFold2 loop structure suggestion, the β2i N-terminus could at least potentially span the distance to the plasma membrane, enabling a membrane attachment. Our findings provide a basis for future studies to decipher the role of the β2i N terminus, regarding (i) the structure of the potential loop and (ii) the membrane interaction—by a potential α helix as suggested by AlphaFold2, with hydrophobic protrusions, as a partial insertion or a full transmembrane segment.

Concluding remarks

We identified a novel splice variant of the already diverse Cavβ2 N-terminus. While association of β2i with the plasma membrane itself is not a novel feature, the propensity for clustering and its dependence on hydrophobic residues is distinct. As the biophysical properties of Ca2+ channels in complex with β2i resemble those of other membrane-associated variants, other features of this variant might be more relevant for its dominant role in the retina. Identifying the mechanisms behind clustering and membrane targeting of β2i could provide new insights into Ca2+ channel regulation in retinal ribbon synapse organization and also help closing the gap in understanding the functional roles of the large diversity of β2 N-terminus splice variants.

Experimental procedures

RNA-Seq

We used publicly available RNA-Seq data from National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) to screen for gene expression and alternatively spliced exons. We analyzed data from mouse total retina (bulk RNA-Seq of whole retina, GEO accession GSE33141 [SRR358714–SRR358716], postnatal day 21 C57BL6 wildtype retina, (12)).

Raw FASTQ files were downloaded from GEO with the fastq-dump module of the SRA tools. Quality control of the FASTQ files was performed with fastqc and trimming, where necessary, was performed with trimmomatic (46). The alignment of reads was done using STAR (47), with GENECODE’s GRCm38 (vM21) primary assembly FASTA file. Assignment of reads to features was performed with featureCounts (48), using GENECODE’s vM21 primary assembly annotation GTF file. Visualization of the reads mapping to the reference genome (mm10/GRCm38 – vM21) was performed using Broad Institute’s IGV (49). All samples of a dataset were pooled for viewing in a single track, and data were displayed as Sashimi plots for visualization of splice junction mapping reads. Software versions used: Python 3.7.1, fastq-dump 2.9.4, FASTQC 0.11.8, trimmomatic 0.39, STAR 2.7.1a, featureCounts 1.6.1, R 3.6.1, and IGV 2.4.5.

Mouse tissue sample preparations

Experimental procedures were designed to minimize animal suffering and the number of used animals and approved by the national ethical committee on animal care and use (Austrian Federal Ministry for Science and Research). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Animals were kept in a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle, and all experiments were performed during circadian day times with light-adapted animals. All mice were anesthetized with isofluorane prior to cervical dislocation, decapitation, and tissue removal. Retinas (one sample = both retinas of one animal) were isolated from 3-month-old male C57BL6/J mice. Retinas were removed in cold PBS on ice and immediately transferred to the lysis buffer. Pineal glands (one sample = pineal glands of eight animals pooled) were extracted from 2- to 3-month-old female C57BL/6J mice. Pineal glands were collected from removed skullcaps and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, stored at −80 °C, and subsequently pooled in the lysis step. Pancreatic islets (one sample = 145–197 islets per animal pooled) were collected from 2-month-old male C57BL/6N mice as described previously (50). Heart muscle (one sample = heart of one animal) was prepared from 2-month-old female C57BL/6J mice. Hearts were removed, and the caudal tips of the heart myocards were homogenized, with a rotor-stator homogenizer in lysis buffer followed by proteinase K digestion. Cochlea samples were taken from 3-week-old NMRI mice as part of another study (51). Samples from brain were dissected from 3-month-old male C57BL/6N mice as part of another study (52).

RNA isolation

RNA was isolated from the retina samples using Rneasy Mini kits (Qiagen). Contaminating genomic DNA was removed by Dnase I digestion (Qiagen) or prior to reverse transcription by dsDNase (Thermo). The isolated RNA concentrations and purities were determined on a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo).

Reverse transcription

For qPCR applications, reverse transcription of up to 1 μg of RNA was performed with Maxima H minus First Strand cDNA Synthesis kits (Thermo) using random hexamer primers or with LunaScript RT kits (NEB) using a mixture of random hexamer and oligo dT primers following manufacturer's instructions, and the resulting cDNAs were stored at −20 °C until use.

For 5′-RACE, PCR full-length cDNA was produced using the TeloPrime Full-Length cDNA Amplification Kit (Lexogen) using oligo-dT primers for reverse transcription and cap-dependent linker ligation selecting for mature full-length RNA molecules that are both polyadenylated and 5′-capped. During linker ligation, an adapter sequence (5′-TGGATTGATATGTAATACGACTCACTATAG-3′) was added to each full-length cDNA molecule, which was used for unbiased amplification of 5′ cDNA ends.

5′-RACE PCR

Two rounds of PCR in a seminested approach were used to amplify the 5′ end of Cavβ2 transcripts. PCR products were visualized on 1.5% low-melting agarose gels together with a size marker (GeneRuler 1 kb Plus; Thermo). Gel-extracted bands (Monarch DNA gel extraction kit; NEB) from the first round were used as template for the second round. PCRs were run with a Phusion proof-reading polymerase using the primers summarized in Table 4 with following protocols:

Table 4.

Primers for 5′-RACE PCR

| PCR round | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| First round | TGGATTGATATGTAATACGACTCACTATAG (TeloPrime adapter FOR) | GCACAGTTGGAAAAAGCAAAG (β2 Ex3 REV out) |

| Second round | TGGATTGATATGTAATACGACTCACTATAG (TeloPrime adapter FOR) | CCGATTCAGATGTGTCTTTGG (β2 Ex3 REV in) |

Composition: 4 μl 5× high-fidelity buffer (Thermo), 2 μl dNTPs (2 mM), 0.6 μl dimethyl sulfoxide, 1 μl forward primer (10 μM), 1 μl reverse primer (10 μM), 0.2 μl Phusion polymerase (Thermo), 10.2 μl water, and 1 μl Cdna (20 ng) for the first round or 1 μl of purified gel–extracted PCR product of the first round for the second round. Program: 98 °C/30 s; [98 °C/7 s; Tm/27 s; 72 °C/25 s] ∗ 35 cycles; 72 °C/10 min. Tm was 60 °C for the first round and 66 °C for the second round.

qPCR

Gene expression quantification was performed by probe-based qPCR using off the shelf and custom-made TaqMan assays (Thermo) for which standard curves were established as described elsewhere (53) to allow for absolute quantification. Most of the Cavβ TaqMan assays used have been established previously (54). Specificity of the new custom β2i assay was confirmed by spike-in tests with mixtures of β2i: β2a DNA templates at 1:1, 1:2, 1:5, and 1:10 ratios (103:103 to 103:104 molecules) that showed unchanged cycle thresholds (CT) from a pure β2i template (CT 27.34 for 103 molecules of pure β2i versus CT 27.63, 27.75, 27.82, and 27.93, respectively, for the mixtures; means, n = 3 each). qPCR was run on a real-time PCR machine (7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System; Applied Biosystem) in duplicates in a 96-well format with the following composition per reaction: 10 μl Luna Universal Probe qPCR 2× master mix (NEB), 4 μl water, 1 μl assay, 5 μl Cdna (preadjusted to 0.4 ng/μl = 2 ng RNA-equivalent per reaction) or 5 μl water for negative controls, using the standard ramp speed program for probe-based assays. Cycle thresholds were determined at 0.1 ΔRn of the amplification curves, and molecule numbers were calculated as described before (55) based on the standard curves for each assay, normalized by the most stable reference (house-keeping) genes for each sample type determined by geNorm methods (56). The assays used are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Assays for qPCR

| Cavβ | Exon boundary | Assay ID or primer and probe sequences (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| β1 | Ex1–Ex2 | Mm00518940_m1 |

| β2 | Ex4–Ex5 | Mm01333550_m1 |

| β3 | Ex1–Ex2 | Mm00432233_m1 |

| β4 | Ex11–Ex12 | Mm00521623_m1 |

| β2a | 5′-UTR—Ex2B | CACGGTGCCGCTTGGT (FOR) TGCATGAAGAGGTGGCAGAA (REV) AAGCCACGCTCTGAC (Probe) |

| β2b | 5′-UTR— Ex2C | TTACACATCTCAAACTTCAGGGAAAA (FOR) CCAGCTAAAGGTGGCTTTGC (REV) CGGAGCCCGTGCGA (Probe) |

| β2cda | Ex2A–Ex3 | AAAGGCTCGGATGGAAGCA (FOR) CCCTGGCGGACAAAACTGT (REV) ATCGTCAGACACTACCTC (Probe) |

| β2e | Ex2D—Ex3 | GGGAGGAAGGCTGAAGAGTTC (FOR) GGGCGGCTGGTGTAGGA (REV) ACATCTGTGGTTCGGC (Probe) |

| β2i | Ex2E–Ex3 | AACTGCTGTTGGTCACCTCAACT (FOR) GGGCGGCTGGTGTAGGA (REV) TCCTGAATGTTGCCATGC (Probe) |

| Reference gene | Assay ID |

|---|---|

| Actb | Mm00607939_s1 |

| B2m | Mm00437762_m1 |

| Gapdh | Mm99999915_g1 |

| Hprt1 | Mm00446968_m1 |

| Sdha | Mm01352363_m1 |

| Tbp | Mm00446973_m1 |

| Tfrc | Mm00441941_m1 |

Assay does not distinguish between β2c and β2d.

Cloning procedures

All β2 vectors used in this study were based on plasmids containing the cds of mouse β2 variants (β2a:β2-N3-Pcaggs-IRES-GFP, β2d:β2-N1-Pcaggs-IRES-GFP, β2e:β2-N5-Pcaggs-IRES-GFP; gift from V. Flockerzi (57)), thus using identical CAG promoters and differing only in the cds for the β2 variants, ensuring equal drive for expression.

The β2 variant expression vectors were supplemented with a DNA sequence coding for the C-terminal end of β2 with the stop codon removed, a short linker (coding for Gly-Ala-Thr-Gly), and the cds for mEm (synthetic sequence; Twist BioScience) followed by a stop codon, leading to in-frame translation of β2 variants with a C-terminally fused mEm fluorescent reporter for live-cell imaging experiments.

N-terminus modifications were derived from a synthetic DNA fragment (K>A, TS>A, and 10VL>A modifications; Twist BioScience) that introduced the desired changes by exchanging the respective part in the original β2i vector. We generated β2X13 by replacing the HOOK domain in β2a with the exon 7B-containing HOOK domain from β2i. For electrophysiological experiments, β2 variant vectors without conjugated reporter sequences were used. Where necessary, IRES-GFP cassettes were removed from parent β2 variant vectors by SmaI digestion and religation of the backbones after gel purification.

Cloning β2i from mouse retina

We used the full-length Cdna from whole mouse retina (as described previously) to amplify the β2i sequence from N-terminus to exon 9 (including exon 7B) in a nested PCR approach (primers in Table 6). The nested forward primer added a SacI restriction site for subsequent cloning. PCR was run with the same composition and program described previously for the 5′-RACE PCR, albeit with 66 °C annealing temperature for the outer PCR and 61 °C for the nested PCR.

Table 6.

Primers for cloning of mouse β2i

| PCR | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outer PCR | TGTGATGTGCAACTTTCCATG (5′UTR) | TTCACTCTGAACTTCCGCTAAG (exon 10–11 boundary) | 1118 |

| Nested PCR | AATTGAGCTCGCCACCATGTTGGTGAAACTGCTGTTGG (Ex2E; SacI; start codon) | TGATGGATATCCGCCCTTC (Exon 9–10 boundary; EcoRV) | 863 |

After gel electrophoresis, the bands with the predicted sizes were extracted using the Monarch DNA gel extraction kit (NEB) and used for nested PCR and restriction digestion, respectively. The nested PCR product was digested with SacI-HF and EcoRV-HF (NEB) yielding an insert with 5′ overhangs and a 3′ blunt end. The same enzymes were used to digest the target plasmid backbone (β2a:β2-N3-pCAGGS) into which the insert was ligated after purification by Takara DNA Ligation Kit (Takara) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequence identity was confirmed by sequencing.

Functional analyses in tsA-201 cells

Cell culture, transfection procedures, and whole-cell patch-clamp recording conditions were as previously described (58). Mouse β2 subunits (mβ2i-pCAGGS, mβ2X13-pCAGGS, mβ2a-pCAGGS-IRES-GFP, mβ2d-pCAGGS, see aforementioned) were transiently cotransfected with human Cav1.4 α1 (59) and mouse α2δ-4 (mα2δ-4-pIRES2-enhanced GFP [eGFP] (60), gift from MA Denti/S Casarosa) or mouse β2 subunits (mβ2i-pCAGGS, mβ2i(K>A)-pCAGGS, mβ2i(5LV>A first)-pCAGGS, mβ2i(10LV>A)-pCAGGS, mβ2a-pCAGGS-IRES-GFP, and mβ2d-pCAGGS) were transiently cotransfected with human Cav1.2 α1 (61) and rabbit α2δ-1 (GenBank accession number: NM_001082276) using the Ca2+-phosphate precipitation method (62) together with eGFP as transfection marker in tsA-201 cells. DNA concentrations used for transfections were 0.2 μg/ml for β2 subunits, 0.3 μg/ml Cav1.4 α1 or Cav1.2 α1, 0.25 μg/ml α2δ-4, and 0.1 μg/ml eGFP, corresponding to ratios of approximately 0.9:1.0:0.6:0.5 for these vectors (DNA amounts normalized by plasmid sizes). Solutions for recordings were (in millimolar): intracellular solution: 135 CsCl, 10 Cs-EGTA, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 4 Na2-ATP, pH 7.3, adjusted with CsOH; extracellular solution: 15 CaCl2 (for Cav1.4) or 15 BaCl2 (for Cav1.2), 150 choline-Cl, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, pH 7.4 adjusted with CsOH. Borosilicate glass patch pipettes with resistances of 1.2 to 3.5 MΩ were used for recordings. Series resistance was compensated at 60 to 90%, data was low-pass filtered at 2 kHz, and digitized at 50 kHz sampling rate (Axopatch 200B, Digidata 1322A; Molecular Devices). I–V relationships were collected by 25 or 50 ms square pulse from the holding potential of −89 mV (liquid junction potentials of −9 mV corrected offline) to various test potentials (5 mV increments). The obtained I–V plots were fitted to the following equation:

where Gmax is the maximum slope conductance, V is the test potential, Vrev is the extrapolated reversal potential, V0.5 is the voltage of half-maximal activation, and kact is the activation slope factor. The VDI of the channels was examined by pulsing cells to Vmax for 5 s from holding potential. The remaining current was quantified at the end of the test pulse as the percent of the peak inward current.

Cell culture for live-cell imaging

Round coverslips (13 mm diameter, thickness #1.5) were surface treated with hydrochloric acid, rinsed with water, sterilized with ethanol, dried and attached on a droplet of gelatine (1% in water) in 35 mm cell culture dishes before coating with poly-l-lysine (0.1 mg/ml). tsA-201 cells were seeded in the dishes with the prepared coverslips at 300,000 cells/dish and cultured and transfected as described previously using expression vectors of mEm-fused β2 variants or a vector with mEm alone (0.15 μg plasmid DNA of each construct per dish, corresponding to 0.075 μg/ml). For some experiments, a marker for the Golgi apparatus was cotransfected (pmScarlet-H_Giantin_C1 was a gift from Dorus Gadella; Addgene plasmid #85049; http://n2t.net/addgene:85049; Research Resource Identifier: Addgene_85049 (63)). Cells were incubated 24 h post-transfection at 37 °C/5% CO2 and in some experiments an additional 24 h at 30 °C/5% CO2. Only cells from passages 9 to 18 were used for these experiments.

Live-cell imaging

Right before imaging, cell membranes (CellMask Deep Red plasma membrane stain, 1:2000 dilution in cell culture medium) and nuclei (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, 10 μg/ml) were stained for 10 min at 37 °C. Coverslips were washed thrice with PBS and mounted in PBS on glass slides for immediate live-cell imaging. Images were acquired on a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 equipped with an ApoTome using a 63×/numerical aperture 1.4 Oil immersion objective and Colibri LED light source (excitation wavelengths 385 nm [4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole], 475 nm [mEm], 630 nm [CellMask Deep Red], 567 nm [mScarlet]) and appropriate filter sets for each fluorophore. A variable number of representative images with multiple mEm-positive cells per image were acquired from each coverslip and subjected to processing and analysis with the aim of highest possible comparability of conditions for evaluation.

Image processing and quantitative colocalization analysis

Zeiss Zen lite was used for image processing. Acquired images were divided into image sections containing cells with comparable mEm fluorescence intensity. The histograms of mEm and CellMask channels were adjusted to span the individual intensity ranges to achieve best possible comparability of the two markers and in between images. Colocalization analysis was performed using the plug-in JACoP (64) for ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/; Version 1.53q, Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health). The MC as measure of colocalization was calculated as the fraction of suprathreshold pixels in the mEm channel colocalizing with suprathreshold pixels in the CellMask channel, that is, percentage of mEm pixels localized at the membrane (10, 64). The thresholds for the calculation of the MC were set manually for the CellMask channel in each image aiming for best representation outline of the plasma membrane. The same threshold value was selected for the mEm channel to avoid bias and to ensure comparability (as both channel histograms had been preadjusted to span the same range). Image sections or individual cells were excluded from quantitative colocalization if at least one of the following criteria was fulfilled: dead cell, visible protrusions from the cell membrane, apparent overexposure, parts of the membrane blurry or weakly stained, and extracellular background fluorescence noise in the image indicating erroneous thresholds. Furthermore, image sections of cells expressing β2i and modifications imaged 2 days post-transfection were excluded from quantification when strong reticular mEm signal or clusters in the Golgi apparatus above threshold were apparent.

Structure investigation

We downloaded all available Cavβ structures (Table 7) as well as full Ca2+ channel complex structures from the PDB aligned and visualized them with PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8.0.0; Schrödinger, LLC) and UniProt Align (https://www.uniprot.org/align; European Molecular Biology Laboratory, EMBL) (65, 66).

Table 7.

Available β2 structures

| PDB code | Mzethod | Resolution (Å) | Species | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1T0H | X-ray | 1.97 | Rattus norvegicus (rat) | (21) |

| 1T0J | X-ray | 2.00 | Rattus norvegicus (rat) | (21) |

| 1T3L | X-ray | 2.20 | Oryctolagus cuniculus (rabbit) | (26) |

| 1T3S | X-ray | 2.30 | Oryctolagus cuniculus (rabbit) | (26) |

| 3JBR | Cryo-EM | 4.20 | Rattus norvegicus (rat) | (29) |

| 4DEX | X-ray | 2.00 | Oryctolagus cuniculus (rabbit) | (68) |

| 4DEY | X-ray | 1.95 | Oryctolagus cuniculus (rabbit) | (68) |

| 5V2P | X-ray | 2.00 | Rattus norvegicus (rat) | (69) |

| 5V2Q | X-ray | 1.70 | Rattus norvegicus (rat) | (69) |

Statistical analysis

Electrophysiology

Data are presented as mean ± SD, unless stated otherwise for the indicated number of cells analyzed (n). Data analysis was performed using Clampfit 10.0 (Axon Instruments), Sigmaplot 14.0 (Systat), and GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc). Data were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons in reference to β2i in GraphPad Prism 8.0. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Significance levels of p < 0.05, p < 0.01, or p < 0.001 are denoted in graphs by a single, double, or triple asterisk, respectively. Inactivation properties were determined as remaining currents after 5000 ms as a percentage of the maximum (r5000)

Live-cell imaging

The arithmetic mean of the MCs was calculated for each transfection (n). These means were weighted against the number of analyzed image sections per transfection to calculate the weighted mean over transfections. Statistical analyses were done in GraphPad Prism. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons in reference to β2i. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Significance levels of p < 0.05, p < 0.01, or p < 0.001 are denoted in graphs and tables by a single, double, or triple asterisk, respectively.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supporting information files).

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information (11, 13, 30, 50, 51, 52, 66, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Heigl for outstanding scientific support, Bettina Tschugg and Jennifer Müller for excellent technical support, Filip Van Petegem for fruitful discussion, and Noelia Jacobo-Piqueras and Nadja Hofer for aid in preparation of mouse tissue samples. This work was supported by the Center for Molecular Biosciences Innsbruck, the University of Innsbruck, and the Medical University of Innsbruck.

Author contributions

H. S. and A. K. conceptualization; H. S., J. O., J. H., L. Z., U. T. L., G. F., M. L. F.-Q., and T. K. methodology; G. F. and M. L. F.-Q. software; H. S., J. O., P. G., J. H., L. Z., G. F., M. L. F.-Q., and T. K. formal analysis; J. O., P. G., J. H., L. Z., and U. T. L. investigation; H. S., L. Z., and A. K. validation; H. S. and A. K. writing–original draft; H. S., J. O., P. G., U. T. L., G. F., M. L. F.-Q., T. K., and A. K. writing–review & editing; H. S., J. O., P. G., J. H., L. Z., G. F., M. L. F.-Q., and T. K. visualization; H. S. and A. K. project administration; H. S. and A. K. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information

This research was funded in whole, or in part, by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF P33566 to H. S. and P32747 to A. K.). For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any author accepted manuscript version arising from this submission.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Kirill Martemyanov

Contributor Information

Hartwig Seitter, Email: hartwig.seitter@gmail.com.

Alexandra Koschak, Email: alexandra.koschak@uibk.ac.at.

Supporting information

References

- 1.Neely A., Garcia-Olivares J., Voswinkel S., Horstkott H., Hidalgo P. Folding of active calcium channel β1b-subunit by size-exclusion chromatography and its role on channel function. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:21689–21694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312675200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buraei Z., Yang J. Structure and function of the β subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1828:1530–1540. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olcese R., Qin N., Schneider T., Neely A., Wei X., Stefani E., et al. The amino terminus of a calcium channel β subunit sets rates of channel inactivation independently of the subunit’s effect on activation. Neuron. 1994;13:1433–1438. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qin N., Olcese R., Zhou J., Cabello O.A., Birnbaumer L., Stefani E. Identification of a second region of the β-subunit involved in regulation of calcium channel inactivation. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271:C1539–C1545. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.C1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]