Highlights

-

•

The pCRP to mCRP change is measured using several methods sensitive to conformation.

-

•

Several chemical treatments yield modified CRP, few lead to a form that binds C1q.

-

•

Modified CRP binding to C1q is achieved with dilute SDS and heat treatment.

Keywords: Non-denaturing PAGE, ELISA, Complement immune response, mCRP, pCRP, ANS, Tryptophan fluorescence, Circular dichroism, Dynamic light scattering

Abstract

C-reactive protein (CRP) is commonly measured as an inflammatory marker in patient studies for coronary heart disease, autoimmune disease and recent acute infections. Due to a correlation of CRP to a vast number of disease states, CRP is a well-studied protein in medical literature with over 16000 references in PubMed [1]. However, the biochemical and structural variations of CRP are not well understood in regards to their binding of complement immune response proteins. Conformations of CRP are thought to affect disease states differently, with a modified form showing neoepitopes and activating the complement immune response through C1q binding. In this work, we compare the unfolding of CRP using chemical denaturants and identify which states of CRP bind a downstream complement immune response binding partner (C1q). We used guanidine HCl (GndHCl), urea/EDTA, and 0.01% SDS with heat to perturb the pentameric state. All treatments give rise to a monomeric state in non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis experiments, but only treatment with certain concentrations of denaturant or dilute SDS with heat maintains CRP function with a key downstream binding partner, C1q, as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. The results suggest that the final form of modified CRP and its ability to mimic biological binding is dependent on the preparation method.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

C-reactive protein (CRP) is an inflammation mediator and plays an active role in the complement immune response to clear foreign material and apoptotic cells from the body [2]. The amount of CRP in serum is related to numerous disease states, such as coronary heart disease [3], Alzheimer's disease [4] autoimmunity, and COVID-19 severity [5], [6], [7]. In many diseases, elevated CRP levels are related to increased risk (i.e. coronary heart disease, Alzheimer's disease) and CRP is often measured as a marker for chronic disease. In other diseases (i.e. arthritis, multiple sclerosis) overexpression of CRP in mouse models has been shown to be protective [8,9]. Although elevated CRP levels reveal inflammation, CRP is necessary for immune system regulation.

Native, pentameric CRP (pCRP) is a stable, soluble, homopentamer present in serum. CRP binds to damaged cell membranes and foreign pathogens to activate an immune response for clearance [2,10,11]. It has been proposed that cellular damage exposes phosphatidylcholine (PC) headgroups and this allows CRP to bind [2] through Ca2+ dependent binding sites present on each monomer [12] shown in Fig. 1. Upon binding membranes, CRP activation of the complement immune response likely involves pentamer dissociation to reveal neoepitopes [13,14]. The new form of CRP is referred to as modified CRP (mCRP), but the precise structure of this conformation is not known and it is not meant to refer to monomeric CRP. In response to the new portions of CRP that are exposed, binding partners, such as C1q, recognize CRP and the complement immune response is initiated [15]. The majority of research points to membrane bound CRP binding the globular head region of C1q [11,[16], [17], [18]]. However, mCRP has been shown to bind mainly to the collagen-like regions of C1q [11]. To activate C1q, it is predicted that multivalent binding needs to occur through the globular heads [19]. In the pentameric state pCRP presents only one binding site for the large C1q, therefore multiple copies are likely needed [17]. A single pentamer that transforms into a modified form could expose multiple epitopes for C1q binding and this would lead to multivalent binding. In support of this, other studies have shown that the native form of CRP is incapable of binding C1q and a modified form is required [18,20].

Fig. 1.

pCRP has rotated protomers and PC binding sites, as seen by the secondary structure. Secondary structure of pCRP (PDB 1B09) includes α-helices (orange) and β-sheets (purple) along with a calcium (yellow) dependent PC (blue) to PC binding site [12,37]. Distance from center of PC binding between protomers is 4.2 nm.

In most patient studies, the soluble, pentameric form of CRP is measured, but there is clear evidence that the conformational state of CRP affects function and physiological reactivity [18,[21], [22], [23], [24], [25]]. Multiple forms of CRP have been measured in patient samples, where atypical forms of CRP were identified in patient serum by gel electrophoresis and correlated to obesity [26]. Modified forms, as recognized by antibodies that are specific for epitopes that are not exposed in pCRP, have also been found in plaque [13], suggesting an active role of modified CRP in cardiovascular disease. The causes and effects of CRP conformational changes are not well understood. Proposed causes of conformational change include membrane binding and/or the presence of an acidic environment, like those at sites of inflammation [27,28]. Membrane shape may also play a role in CRP conformational change since certain forms of CRP have curvature preferences [29,30]. In general, binding to membranes likely stabilizes the transition from a pentamer to monomer by allowing for insertion into membranes to stabilize hydrophobic portions of the protein, like the cholesterol binding domain [31].

Despite the broad interest in CRP, there is a noticeable gap of information in the biochemical literature regarding how different conformational states affect biochemical reactivity. The main purpose of this work was to design a method for CRP conversion in the laboratory and an assay for creating a form of CRP that mimics modified CRP activity. Since one physiological purpose of CRP is to activate C1q, we have chosen our readout for making an active, modified form of CRP as one that can bind C1q. To determine the best method for CRP conversion, we formed modified CRP biochemically with urea/EDTA [18,22,[31], [32], [33]], with Guanidine HCl [34] or by dilute SDS and heat [23,35]. We compared a variety of methods for synthesizing mCRP from serum purified pCRP and then tested each method for the ability to produce a form of CRP that: (1) runs differently than pCRP on a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel and (2) binds C1q, one of the downstream binding partners of CRP in the complement immune response. The change in conformation was characterized by tryptophan (Trp) and 1-anilinonaphthalene-8-sulfonic acid (ANS) fluorescence, which show clear differences in methods used to make modified CRP. Circular dichroism (CD) measurements reveal that secondary structure is altered during conversion. These methods build upon previous methods that have characterized CRP states by non-denaturing PAGE procedures [23] and adds functional relevance through ELISA based assays with C1q. We conclude that dilute SDS/heat treated pCRP consistently produces a functional form of modified CRP, whereas only certain concentrations of GndHCl and urea/EDTA result in a functional mCRP.

Materials and methods

Reagents

C-reactive protein was purchased from Academy Bio-Medical Company (#30P-CRP110) and stored at 4°C for up to 6 months. Standard CRP concentration used was 57.5 μg/mL unless otherwise noted. C1q was purchased from Complement Technologies (#A099). Standard buffers used for the majority of these experiments were 30 mM PIPES (J.T. Baker), 2 mM calcium chloride, 140 mM sodium chloride, pH 6.4. Chemicals were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific or Sigma Aldrich unless otherwise noted. Stock denaturant solutions of 6 M GndHCl and 8 M urea, 10 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) were made in standard buffer (pH 6.4). GndHCl and urea CRP conversion samples were allowed to incubate for 2 h at room temperature prior to analysis. Dilute sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) treated mCRP was made by combining CRP in standard buffer with 0.01% SDS and heating for 1 h at 80°C [35]. All error values are standard error of the mean. All concentrations reported are final concentrations after adding CRP, which may differ from the work of others [36].

Structural analysis

The published crystal structure of CRP with bound PC was used for all structural illustrations and analysis [12]. Renderings were done using the UCSF Chimera software [37].

Non-denaturing PAGE

CRP forms were visualized using a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) assay previously established [35] Standard Laemmli conditions were followed [38] with the exception of using 0.005% SDS in the gel and using native sample buffer (no SDS, BME, or heat). These modifications ensured a non-denaturing gel. Standard tris-glycine running buffer containing 0.1% SDS was used. The amount of CRP loaded into each well was 0.43 μg. Gels were run at 80 V for 2 h and then silver stained. Relative molecular weights for denatured proteins were marked for comparison by using Precision Plus Dual Color Standards (Bio-Rad #1610374). Gels shown are representative of at least 4 experiments.

Tryptophan fluorescence spectroscopy

All fluorescence measurements were measured in a Tecan Infinity M1000 Plate Reader using black polystyrol half area 96 well plates (Corning #3694). The intrinsic fluorescence of CRP was measured using 57.5 µg/mL of CRP, which was compared with 3.06 µg/mL tryptophan (the equivalent concentration for the amount of CRP used based on 6 tryptophan residues per monomer). Excitation wavelength was 280 nm with a bandwidth of 2.5 nm. Emission spectra were collected from 300-400 nm with a step size of 5 nm and a bandwidth of 5 nm. The fluorescence intensity from 300-400 nm was integrated and then each value was normalized to the integrated pCRP intensity. The intensity was integrated because the peak shifted slightly from approximately 335 nm to 340 nm in the presence of denaturants. Data points were not included when they fell more than two standard deviations from the mean value.

Dynamic light scattering

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was performed on a DynaPro Plate Reader II with Dynamics version 7 software (Wyatt Technology) using a 384 well glass bottom plate (Greiner Bio-One Sensoplate #781892). CRP (500 µg/mL in pH 6.4 PIPES buffer, details above) was placed into 4 wells for measurements (50 µL). The plate was centrifuged at 200 rpm for 2 min. Readings were performed at 25°C using a 5 s acquisition time with auto-attenuation. The solvent setting for the system used was based on phosphate buffered saline with a refractive index of 1.333 (at 589 nm for 20°C) and a viscosity of 1.019 cP. Each well had 10 acquisitions. A Rayleigh spheres model was used to fit the data with the Dynamics software.

Circular dichroism

CRP samples of pCRP and mCRPHeat were prepared for circular dichroism (CD) by dilution in standard HEPES buffer at pH 7.4 to a concentration of 19.6 µg/mL. Dilute SDS samples contained 19.6 µg/mL of CRP in phosphate buffer (10 mM disodium phosphate, 2.7 mM potassium chloride, 1.8 mM monopotassium phosphate, 1 mM calcium chloride, pH 7.6) with 0.005% SDS. CD spectra from 207-250 nm was recorded using a JASCO J-1500 Circular Dichroism Spectrometer. Samples with SDS were heated and measured at 5-degree intervals from 20 to 80°C and then allowed to cool to room temperature (20°C) before the final scan. Background CD spectra from buffers was subtracted for all samples.

ANS fluorescence assay

1-Anilinonaphthalene-8-sulfonic acid (ANS), a hydrophobic fluorescent probe purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI), was used to monitor the conformational changes of CRP after treating the protein with different denaturants. The stock solution of 100 mM ANS was dissolved in DMSO and diluted to a final concentration of 190 μM with Millipore water. CRP (50 μg/mL) was incubated with the GndHCl or urea/EDTA denaturants in HEPES buffer (pH 6.4) for 2 h at 37°C. Dilute SDS CRP samples were heated for 1 h at 80°C with 0.01% SDS in HEPES buffer (pH 6.4). The control pCRP sample was diluted in TBS buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.2). Fluorescence intensity of ANS was measured using an excitation wavelength of 390 nm, and emission spectra were measured from 440 nm to 650 nm. The same plate reader and plates listed above in tryptophan fluorescence were used for ANS experiments.

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Binding of CRP to C1q was measured by performing an ELISA with C1q as a capture or fatty acid free bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a control, each at a concentration of 1 µg/mL, following previously published procedures [35]. Experiments used a 96 well high binding clear microplate (either Greiner Bioscience Microlon 600 #655081 or Nunc Maxisorp Immuno Plate #446612). Variations in the protocol incubations include CRP (1.8 µg/mL) incubated for 1 h at 37°C and both biotinylated polyclonal anti-CRP (Academy Biomedical Co.) and streptavidin-HRP being incubated at 37°C instead of room temperature. Color from 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate was allowed to develop (5-10 min) at room temperature prior to stopping with sulfuric acid as described in the published procedure. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm, with a reference absorbance of 620 nm on the Tecan microplate reader.

Results

To determine the stability of the native, pentameric form of CRP, we denatured CRP using two common denaturants, urea/EDTA and GndHCl. The intrinsic, tryptophan fluorescence was measured and found to decrease with increasing denaturant, as expected, for most concentrations (Figs. 2A and B). The change in fluorescence occurs as some of the 6 Trp residues (per monomer of CRP) go from a hydrophobic protein environment to a more aqueous environment. Denaturation with GndHCl led to a clear transition (Fig. 2A) between 2 and 2.75 M GndHCl, however, the gradual decline in fluorescence from 0 to 2 M suggests conformational changes are occurring even at low concentration. Interestingly, tryptophan fluorescence increases at GndHCl concentrations higher than 4.25 M (see Fig. S1A). With a weaker denaturant, urea/EDTA, the decrease in fluorescence is more gradual and lacks a clear transition. If pCRP was completely denatured, the expected Trp fluorescence would be equal to the same amount of free Trp in buffer (shown as open circles in Figs. 2A and B). It is interesting to note that the tryptophan fluorescence of CRP treated with GndHCl, to a final concentration of 4M GndHCl, falls below that of free tryptophan, while urea treated CRP treated with urea, to a final concentration of 7M urea, and free Trp have similar integrated fluorescence intensities.

Fig. 2.

Intrinsic fluorescence and non-denaturing PAGE assays of CRP treated with GndHCl and urea. Intrinsic, tryptophan fluorescence was measured by exciting solutions at 280 nm and recording fluorescence from 300-400 nm for both GndHCl (N=8), A) and urea/EDTA (N=10), B) treated CRP (black filled circles) as well as select concentrations for free tryptophan (open circles). The integrated fluorescence was normalized to the 0 M denaturant data point. Error bars are +/- SEM. Non-denaturing PAGE of CRP treated with GndHCl (C) and urea/EDTA (D) after two hours of incubation. The ladders shown are SDS-PAGE (denatured) protein standards for relative molecular weight comparison.

After measuring the intrinsic fluorescence to identify changes in the exposure of Trp residues to an aqueous environment, samples were loaded onto a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel to assess the presence of different states of CRP. Non-denaturing gel conditions were used instead of traditional native gel conditions because mCRP fails to appear under native gel conditions that contain no SDS [23]. Both the molecular mass and the charge affect migration in this assay. In Fig. 2C and D, a clear transition occurs where a modified form of CRP begins to show, running similar to the 20 kDa standard. With GndHCl treatment, this band first shows up at 1.75 M GndHCl and is fully present at 2.75 M, matching the profile of intrinsic fluorescence in Fig. 2A. A slight change in the appearance of the band with non-denaturing gel is observed at higher concentrations of GndHCl (Fig. S1B). When pCRP is treated with urea/EDTA, a clear transition exists in the gel from 2.25 to 4.00 M urea. The mCRP band increases over this range and the pCRP signal (not shown but retained in the stacking portion of the gel) disappears. A haze of protein is also observed in the gel and this fully disappears at 4.00 M. This could be due to alternative states of pCRP that have not been fully characterized and these are present in the absence of urea (Fig. 2D, 0.00 M).

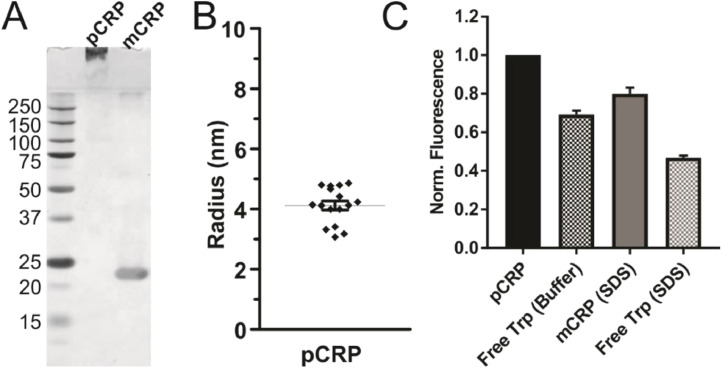

To determine if other denaturants can be used to stabilize a functional form of mCRP, dilute amounts of detergent (SDS) along with heat were tested [30,35]. Non-denaturing PAGE reveals a band around 20 kDa for mCRP made from exposure to 0.01% SDS with heat and a high, slow running, band for pCRP (Fig. 3A). Since pCRP remains in and near the stacking portion of the non-denaturing PAGE gel, dynamic light scattering (DLS) was used to confirm that pCRP is not aggregating. 99.85% +/- 0.09 of the results for the hydrodynamic radius fell between 0 and 10 nm, where the average radius from that range is 4.12 +/- 0.15 nm (Fig. 3B). DLS of mCRP prepared with SDS and heat (80°C) gave results that indicated aggregation due to the high concentration of CRP needed to run the experiment (0.5 mg/ml). This included visual cloudiness in the sample. The different properties of dilute SDS and heat-treated CRP are evident when free tryptophan and CRP levels of all the denaturants are compared. Only mCRP made with SDS and heat has a normalized integrated fluorescence between the pCRP and free tryptophan levels, where free trp measurements were performed in the dilute SDS buffer to mimic the solvent properly (Fig. 3C). Although this data demonstrates that pCRP can undergo large conformational changes in these conditions, structural changes are likely occurring simultaneously.

Fig. 3.

Dilute SDS with heat treatment leads to monomeric CRP. A) Non-denaturing PAGE of pCRP and CRP heated at 80°C with 0.01% SDS (mCRP) demonstrates that the two forms have different electrostatic properties. B) The average radius measured is 4.12 ± 0.15 nm. C) Comparison of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence for pCRP and SDS with heat mCRP with fluorescence of free tryptophan. Normalized to pCRP, N = 16 replicates. All error is SEM.

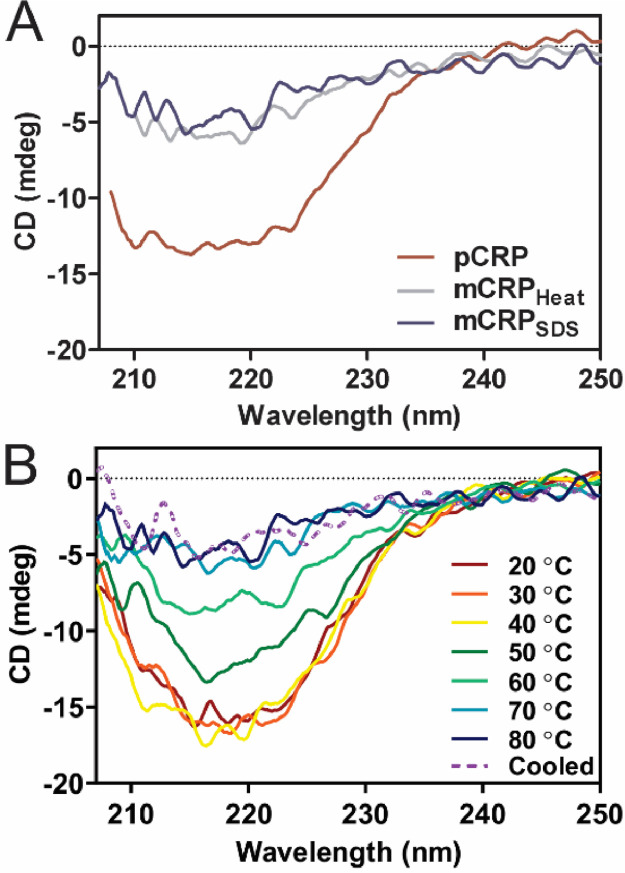

To assess changes in secondary structure during these treatments, circular dichroism (CD) was used to measure CRP during the denaturation process (Fig. 4). pCRP and mCRP have a different CD signal from 210 to 230 nm (Fig. 4A). Although there is a different CD signal for pCRP and mCRP forms, the two methods tested for mCRP – with dilute SDS and heat or with just heat – have similar spectra. CRP treated with dilute SDS was tested at various temperatures and Fig. 4B shows full conversion from pCRP to mCRP around 70°C. CRP that has been cooled back to room temperature post-heating to 80°C continues to show less structure in the 210-230 nm region of α-helices and β-sheets.

Fig. 4.

Circular Dichroism of CRP forms shows a structural change. A) Circular dichroism spectra of pCRP (red line) and mCRP made from heat only (80°C, grey line) and dilute SDS with heat (80°C, blue line). B) CRP sample with dilute SDS in buffer heated in the cuvette from 20-80°C with CD spectra recorded and final sample allowed to cool back to room temperature (dashed purple line).

To monitor the exposure of hydrophobic portions of CRP after incubation with different denaturants ANS, a fluorescent that brightens in hydrophobic environments, was used (Fig. 5). ANS is frequently used to identify protein folding and aggregation. ANS binds to hydrophobic regions of proteins, which leads to a significant increase in its quantum yield and a blue shift in the emission maxima [39]. Previous research has used ANS to investigate the conformational changes of CRP at various pH and temperatures [28,40]. Because ANS binds hydrophobic regions, an increase in ANS fluorescence indicates that the protein has more hydrophobic regions exposed. As shown in Fig. 5, treatment with 3 M GndHCl (Fig. 5A), 6 M urea (Fig. 5B), or 0.01% SDS with heat (Fig. 5C) caused hydrophobic portions of CRP to be exposed when compared to untreated pCRP (Fig 5 A-C, grey). SDS-treated CRP showed the largest change (Fig. 5C, black circles) from the untreated CRP (grey triangles in all Fig.s) compared to other denaturants. The control lacking CRP but containing SDS and ANS (Fig. S2) is similar to the pCRP alone (Fig. 5, grey), which suggests that pCRP minimally binds ANS. Although these data (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4-5) demonstrate that pCRP can convert to mCRP under a variety of conditions, it is not known if the mCRP form produced can retain function and activate an immune response.

Fig. 5.

Treatment of CRP with denaturants increases ANS binding. ANS fluorescence upon binding to CRP incubated with (A) 3 M GndHCl for 2 h at 37°C (black circles), (B) 6 M urea/EDTA at 37°C for 2 h (black circles), and (C) 0.01% SDS with incubation at 80°C for one hour (black circles). Grey triangles for all are pCRP. N = 3 replicates.

After altering the conformation of pCRP with urea/EDTA, GndHCl and 0.01% SDS with heat, we assessed whether the new forms of CRP could bind C1q, a well-established binding partner for initiation of the complement immune response. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed where C1q was used to capture CRP. A polyclonal antibody to CRP with a biotin linkage was used to then bind horseradish peroxidase linked streptavidin (HRP-Strep). In Fig. 6A, the GndHCl treated CRP clearly shows binding to C1q (black filled circles). However, for most concentrations, similar binding was observed for a control, where bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as the capture protein, suggesting that this interaction is not specific. Statistical significance between BSA and C1q binding only exists at 1.5 M GndHCl (p-value of 0.0037 for Student's paired t-test). Urea treated CRP binds BSA comparably to C1q and the binding is also not statistically significant (Fig. 6B). Acid treated CRP shows similar behavior which indicates that the binding observed is not specific [28]. However, dilute SDS with heat-treated CRP does have significant C1q binding with a p-value of 0.0103 as determined by a two-tailed paired Student's t-test (Fig. 6C). Supplemental Table S1 contains a detailed list of all p-values. A summary of the ELISA results for each CRP form is shown in Table 1. The only form of mCRP that retains specific binding to C1q is the dilute SDS and heat preparation.

Fig. 6.

Denaturation of pCRP by GndHCl, urea/EDTA, or dilute SDS with heat alters CRP binding to BSA and C1q. ELISA with BSA (open circles or solid bars) or C1q (filled circles or striped bars) as the capture agent was performed to determine if denaturation at a certain concentration leads to a form of CRP that can bind C1q. A) CRP treated with GndHCl (1.5M final concentration or higher for GndHCl) leads to C1q binding, however the binding above 2 M GndHCl is not specific; BSA capture works equally well. N = 8. B) Urea treated CRP binds C1q at 5 M and higher concentrations, but also binds BSA non-specifically. Data for A and B was normalized to pCRP (0 M GndHCl or urea). N = 4. C) C1q captures CRP treated with 0.01% SDS and heated at 80°C for 1 h (solid black), but not pCRP (solid grey) or antibodies (solid light grey). BSA captures mCRP significantly less than C1q (black stripes) but captures more 0.01% SDS with heat treated CRP than pCRP (grey stripes) or antibodies (light grey stripes). Data was normalized to the average mCRP absorbance with C1q capture. Significance was calculated using a two-tailed Student's paired t-test (p-values < 0.05 shown as * and < 0.01 shown as **). At least 9 replicates per condition. Detailed significance for C can be found in supplemental Table S1. Error bars are SEM and only shown in the positive direction for clarity. Often the SEM is smaller than the data point.

Table 1.

Summary of biochemical preparations of mCRP and their results.

| CRP Preparation | Transition to mCRP | Structural Notes | C1q binding |

|---|---|---|---|

| GndHCl | Non-denaturing PAGE & Trp Fluorescence show transition around 2.75 M | Hydrophobic portions exposed (Trp and ANS Fluorescence) | Only at 1.5 M GndHCl |

| Urea/EDTA | 3 M is where an mCRP band starts to show up in non-denaturing PAGE | Hydrophobic portions exposed (Trp and ANS Fluorescence) | Trends toward binding at 7M, but not statistically significant |

| SDS/Heat | 0.01% SDS and heat for 1 h at 80°C has mCRP band | Cloudiness observed at higher CRP concentrations; CD spectra loses dip in secondary structure region | 0.01% SDS with heat has statistically significant C1q binding |

Discussion

Size suggests that CRP starting material is a soluble pentamer

CRP is known to have both a pentameric native form and a modified form that exposes neoepitopes [20,34]. We confirmed with DLS that pCRP, prior to denaturation methods, had a hydrodynamic radius (RH) within range for the pentameric state (4.12 +/- 0.15 nm, Fig. 3B). In comparison, the measured radius from the pCRP crystal structure is 5.1 nm [41] and the radius of gyration (Rg) for pCRP is 3.7 nm, as determined by x-ray scattering [33]. The Rg has a linear relationship to the RH for spheroidal objects that can be summarized by the equation Rg = 0.775 x RH [42]. Using the RH found by DLS above, our calculated radius of gyration would be 3.19 +/- 0.12 nm. Since CRP is a disk-shaped pentagon [43] and not a perfect sphere, a slight discrepancy between the calculated and observed Rg values is expected. With high salt concentrations in buffer, CRP is expected to stay as a pentamer and not form a decamer [33]. Having established that CRP without any denaturant is the native, pentameric form, the next step was to produce an in vitro mCRP that retains function. Chemical denaturants, such as urea and GndHCl, are widely used to study protein denaturation. Results here from many biochemical assays indicate that methods used to make mCRP have varied effects on the structure of pCRP.

Modified CRP, but not intermediates, can be observed via non-denaturing PAGE

One assay often used to explore the states of CRP is gel electrophoresis. Whether a 2D urea gel [36], reduced SDS [23], or the conditions used here for non-denaturing PAGE, all results show a pCRP band that runs high and a mCRP band that runs low. Each gel (Figs. 2C, 2D, and 3A) shows a native pentameric form that stays near the stacking portion (bands in Fig. 2D have been cropped). Non-denaturing gels separate proteins based on more than molecular weight, including protein shape and charge. pCRP is a 115 kDa pentamer with a pI of 6.4 that changes to 5.6 upon monomerization with urea [34]. The pentameric form has less charge density, is larger, and therefore does not run well into the gel. The pCRP structure has salt bridges between subunits, hydrogen bonding, and van der Waals forces [44]. The gel conditions include pH levels of 8.3 for the running buffer, 6.8 for the stacking portion, and 8.8 for the running portion of the gel, leaving mCRP with more charge to run farther on the non-denaturing gel. Treatment of CRP with ≥ 2.5 M GndHCl, ≥ 3 M urea/EDTA, or 0.01% SDS with heat all run close to the molecular weight for a CRP monomer (23 kDa) with non-denaturing PAGE. It is possible that the observed pCRP to mCRP transition appears at a slightly lower concentration of denaturant in this assay (Fig. 2C-D) due to the presence of a dilute amount of SDS in the non-denaturing gel, which could act additively with the other denaturants. Regardless, the non-denaturing PAGE demonstrates a clear transition and separation of pCRP and mCRP bands and this supports the observations from intrinsic fluorescence measurements (Fig. 2A-B).

The transition from pCRP to mCRP with GndHCl treatment occurs at a similar concentration in both the Trp fluorescence assay and the non-denaturing PAGE measurement (Fig. 2A and C, around 2.5-3 M). The observed Trp fluorescence transition for urea treated CRP is gradual (Fig. 2B, from 2 – 6 M) and over a much wider range than that observed in the gel (Fig. 2D, around 2.5-3M). This gradual transition suggests that conformational changes are still occurring that affect the Trp environment, but that these changes do not broadly influence the size or charge of the protein in a way that affects how it runs on a gel. The transition likely occurs over a larger range of urea concentrations because urea is a weaker denaturant than GndHCl.

Since no intermediates were observed in the gel (only modified and native), the intermediate states of fluorescence intensity were interpreted to be mixtures of folded and unfolded states, not proteins that exist in an intermediate state. However, the work of others [10] suggests that tetramers, trimers and dimers may exist under certain conditions. Our work suggests that only two states exist in a purified, biochemical system. Other conditions and the presence of other proteins may stabilize intermediate states that are not observed here.

CRP changes conformation differently under different denaturing treatments

Each CRP monomer contains 6 Trp residues, which allows for comparison to a control sample of free Trp (Fig.s 2A and 2B, open circles). The lower fluorescence for CRP treated with 4 M GndHCl than for free Trp at the same concentration suggests quenching. Tryptophan is sensitive to environment and many different interactions may contribute to a decrease in fluorescence including aggregation or quenching from nearby residues such as phenylalanine and lysine [45]. There are two Trp residues with an adjacent phenylalanine and the CRP sequence contains 13 lysine residues per monomer (Fig. 7). Conformational changes near the tryptophan residues are most likely the cause of the quenching and the lower than expected fluorescence. However, aggregation of CRP may also explain the low Trp fluorescence followed by an increase at higher concentrations of GndHCl due to stabilization and protein denaturation (Fig. S1A). Each denaturant has a slightly different change in ANS fluorescence in comparison to free ANS in solution (Fig. 4), which points to a difference in how the denaturants change the structural form of CRP. Urea and dilute SDS with heat treated CRP show a larger increase in ANS fluorescence, with the dilute SDS form being the largest change, indicating hydrophobic regions being exposed. A change in the amino acid residues exposed for mCRP is consistent with the observance of a mCRP specific aptamer [35,46].

Fig. 7.

pCRP to mCRP conversion with highlighted amino acid residues. CRP monomer (from PDB 1B09) contains 6 tryptophan residues (navy blue), 13 lysine residues (magenta), 14 phenylalanine residues (yellow), and 2 cysteine residues to form the disulfide bond (green) [51]. Hydrogen bonds are shown in cyan [12,37].

The difference in the secondary structure of pCRP and mCRP forms (Fig. 4A) indicates that mCRP is not merely a monomeric form of pCRP, but that it undergoes a structural change. Types of secondary structure that show up in the 210-230 nm region include α-helix and anti-parallel β-sheet [47]. Native CRP has two antiparallel β-sheets and one α-helix per protomer (Figs. 1 and 7) [12,41]. CD spectra of recombinant mCRP in comparison to pCRP have been reported to have a significant secondary structural change, mainly from β-sheet to α-helix, although no spectra were published [32]. This structural change may be what gives mCRP its different binding properties, such as C1q binding.

GndHCl and Urea/EDTA denatured CRP and do not retain C1q binding

Denaturation with GndHCl is likely harsh and causes full unfolding, such that the sites needed for C1q binding are no longer intact. Instead, the protein binds a wide variety of other proteins, like BSA, likely in a non-specific way. In previous research, others have shown that while CRP treatment with 5 M GndHCl appears to have some monomeric properties [48], various concentrations of GndHCl failed to produce a mCRP form with neoantigenicity [34,48]. This discrepancy was contributed to different pH levels for the experiments, and in light of the research here, GndHCl effects on CRP appears to depend strongly on concentration. Urea/EDTA denaturation has a similar behavior with a trend towards binding C1q more than BSA at high concentrations of urea. Results from a fluorescent anisotropy assay confirm acid treatment also did not allow CRP to retain C1q binding abilities [35]. This agrees with experiments using surface plasmon resonance that show recombinant mCRP and not pCRP binding to C1q [20]. Meanwhile, gentle unfolding with dilute SDS (0.01%) and heat retains binding to C1q (Table 1).

Only dilute SDS/heat treatment maintains CRP:C1q binding

Although, many conditions can cause monomerization and denaturation, only certain conditions leave CRP in a state that is capable of binding C1q. In order to determine which denaturant makes a biologically relevant mCRP form, binding to the downstream C1q complement protein was analyzed with an ELISA (Fig. 5). CRP residues that interact with C1q are near the inside of the ring and the interface of the CRP monomer (Fig. S3) [17]. BSA was used as a control because others have shown that CRP promiscuously binds to a wide range of proteins under acidic conditions [28]. In this same work, at neutral pH, pCRP does not bind BSA. Indeed, we see the same behavior where many forms of mCRP bind BSA equally well to C1q (Fig. 5). The only forms with statistically significant binding to C1q relative to BSA as a capture were mCRP treated with GndHCl to a final concentration of 1.5 M and mCRP treated with dilute SDS and heat (Fig. 6).

Other methods of making mCRP possibly retain C1q binding

In literature, mCRP has been made with a wide variety of methods. Treatment with 8 M urea-EDTA is frequently used for pCRP to mCRP conversion [18,22,30,33,36] and our results indicate that concentrations of urea >7 M are likely to follow the upward trend to make a CRP form with significant C1q binding (relative to non-specific BSA binding). One mCRP preparation method commonly used for cellular and animal experiments is recombinant mCRP, where two cysteines are mutated to alanines [32]. The recombinant form has been shown by others to bind C1q and is considered similar to urea chelated mCRP in other assays [20,32,49,50]. The recombinant form remains mCRP and does not revert back to pCRP [32]. The method of making mCRP with 0.01% SDS and heating for 1 h at 80°C is consistent with functional relevance of C1q binding, in both this work and the work of others [35]. The ability of SDS/heat prepared mCRP to maintain functional relevance even when diluted points to a permanent change in the molecular conformation. This indicates that mCRP is unlikely to return to pCRP. Further studies of mCRP would benefit from using the SDS and heat preparation method due to the consistent C1q binding and simple preparation technique.

Author contributions

MKK and SMR designed the experiments and guided the research project. CLM performed and analyzed all experiments shown except those in Figs. 4 and 5. YC performed the experiments in Fig. 4 and AAA performed the experiments in Fig. 5. CLM and MKK wrote the paper and AAA and SMR provided input. CLM created Figs. 1 and 7 from Chimera. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Michelle K Knowles reports financial support was provided by National Science Foundation.

Acknowledgements

The following funding sources were used for this work: Vinnova (M.K.Knowles, #2015-01541), National Science Foundation (M.K. Knowles, # 1033215), NIH – R15 (S.M.Reed, GM088960), the Libyan Ministry of Higher Education (A. A. Alnaas). Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with the UCSF Chimera package. Chimera was developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bbadva.2022.100058.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.PubMed search for “C-reactive Protein” in title, Accessed 2022 Apr 7. (2022).

- 2.Black S., Kushner I., Samols D. C-reactive Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:48487–48490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casas J.P., Shah T., Hingorani A.D., Danesh J., Pepys M.B. C-reactive protein and coronary heart disease: a critical review. J. Intern. Med. 2008;264:295–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.M. Slevin, S. Matou, Y. Zeinolabediny, R. Corpas, R. Weston, D. Liu, E. Boras, M. Di Napoli, E. Petcu, S. Sarroca, A. Popa-Wagner, S. Love, M.A. Font, L.A. Potempa, R. Al-Baradie, C. Sanfeliu, S. Revilla, L. Badimon, J. Krupinski, Monomeric C-reactive protein–a key molecule driving development of Alzheimer's disease associated with brain ischaemia?, Sci Rep. 5 (2015) 13281. 10.1038/srep13281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Edberg J.C., Wu J., Langefeld C.D., Brown E.E., Marion M.C., Mcgwin G., Petri M., Ramsey-Goldman R., Reveille J.D., Frank S.G., Kaufman K.M., Harley J.B., Alarcón G.S., Kimberly R.P. Genetic variation in the CRP promoter: association with systemic lupus erythematosus. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:1147–1155. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du Clos T.W. Pentraxins : structure, function, and role in inflammation. ISRN Inflamm. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/379040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potempa L.A., Rajab I.M., Hart P.C., Bordon J., Fernandez-Botran R. Insights into the use of C-reactive protein as a diagnostic index of disease severity in COVID-19 infections. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020;103:561–563. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones N.R., Pegues M.A., McCrory M.A., Kerr S.W., Jiang H., Sellati R., Berger V., Villalona J., Parikh R., McFarland M., Pantages L., Madwed J.B., Szalai A.J. Collagen-induced arthritis is exacerbated in C-reactive protein-deficient mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2641–2650. doi: 10.1002/art.30444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szalai A.J., Nataf S., Hu X.-Z., Barnum S.R. Experimental allergic encephalomyelitis is inhibited in transgenic mice expressing human C-reactive protein. J. Immunol. 2002;168:5792–5797. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Q., Kang T., Tian X., Ma Y., Li M., Richards J., Bythwood T., Wang Y., Li X., Liu D., Ma L., Song Q. Multimeric stability of human C-reactive protein in archived specimens. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji S.R., Wu Y., Potempa L.A., Liang Y.H., Zhao J. Effect of modified C-reactive protein on complement activation: a possible complement regulatory role of modified or monomeric C-reactive protein in atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006;26:934–941. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000206211.21895.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson D., Pepys M.B., Wood S.P. The physiological structure of human C-reactive protein and its complex with phosphocholine. Structure. 1999;7:169–177. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenhardt S.U., Habersberger J., Murphy A., Chen Y.C., Woollard K.J., Bassler N., Qian H., von zur Muhlen C., Hagemeyer C.E., Ahrens I., Chin-Dusting J., Bobik A., Peter K. Dissociation of pentameric to monomeric C-reactive protein on activated platelets localizes inflammation to atherosclerotic plaques. Circ. Res. 2009;105:128–137. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.190611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ji S.-R., Wu Y., Zhu L., Potempa L.A., Sheng F.-L., Lu W., Zhao J. Cell membranes and liposomes dissociate C-reactive protein (CRP) to form a new, biologically active structural intermediate: mCRP(m) FASEB J. 2007;21:284–294. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6722com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaboriaud C., Frachet P., Thielens N.M., Arlaud G.J. The human C1q globular domain: Structure and recognition of non-immune self ligands. Front. Immunol. 2012;2:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGrath F.D.G., Brouwer M.C., Arlaud G.J., Daha M.R., Hack C.E., Roos A. Evidence that complement protein C1q interacts with C-reactive protein through its globular head region. J. Immunol. 2006;176:2950–2957. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal A., Shrive A.K., Greenhough T.J., Volanakis J.E. Topology and structure of the C1q-binding site on C-reactive protein. J. Immunol. 2001;166:3998–4004. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mihlan M., Blom A.M., Kupreishvili K., Lauer N., Stelzner K., Bergstrom F., Niessen H.W.M., Zipfel P.F. Monomeric C-reactive protein modulates classic complement activation on necrotic cells. FASEB J. 2011;25:4198–4210. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-186460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaboriaud C., Thielens N.M., Gregory L.A., Rossi V., Fontecilla-Camps J.C., Arlaud G.J. Structure and activation of the C1 complex of complement: unraveling the puzzle. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bíró A., Rovó Z., Papp D., Cervenak L., Varga L., Füst G., Thielens N.M., Arlaud G.J., Prohászka Z. Studies on the interactions between C-reactive protein and complement proteins. Immunology. 2007;121:40–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiele J.R., Habersberger J., Braig D., Schmidt Y., Goerendt K., Maurer V., Bannasch H., Scheichl A., Woollard K., von Dobschutz E., Kolodgie F., Virmani R., Stark G.B., Peter K., Eisenhardt S.U. The dissociation of pentameric to monomeric C-reactive protein localizes and aggravates inflammation: in vivo proof of a powerful pro-inflammatory mechanism and a new anti-inflammatory strategy. Circulation. 2014;130:35–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujita M., Takada Y.K., Izumiya Y., Takada Y. The binding of monomeric C-reactive protein (mCRP) to integrins αvβ3 and α4β1 is related to its pro-inflammatory action. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor K.E., Van Den Berg C.W. Structural and functional comparison of native pentameric, denatured monomeric and biotinylated C-reactive protein. Immunology. 2007;120:404–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02516.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajab I.M., Hart P.C., Potempa L.A. How C-reactive protein structural isoforms with distinctive bioactivities affect disease progression. Front. Immunol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Potempa L.A., Rajab I.M., Olson M.E., Hart P.C. C-Reactive protein and cancer: interpreting the differential bioactivities of its pentameric and monomeric, Modified Isoforms. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.744129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asztalos B.F., Horan M.S., Horvath K.V., McDermott A.Y., Chalasani N.P., Schaefer E.J. Obesity associated molecular forms of C-reactive protein in human. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eisenhardt S.U., Habersberger J., Murphy A., Chen Y.-C., Woollard K.J., Bassler N., Qian H., von Zur Muhlen C., Hagemeyer C.E., Ahrens I., Chin-Dusting J., Bobik A., Peter K. Dissociation of pentameric to monomeric C-reactive protein on activated platelets localizes inflammation to atherosclerotic plaques. Circ. Res. 2009;105:128–137. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.190611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammond D.J., Singh S.K., Thompson J.A., Beeler B.W., Rusiñol A.E., Pangburn M.K., Potempa L.A., Agrawal A. Identification of acidic pH-dependent ligands of pentameric C-reactive protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:36235–36244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.142026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alnaas A.A., Moon C.L., Alton M., Reed S.M., Knowles M.K. Conformational changes in C-reactive protein affect binding to curved membranes in a lipid bilayer model of the apoptotic cell surface. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:2631–2639. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b11505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang M.S., Messersmith R.E., Reed S.M. Membrane curvature recognition by C-reactive protein using lipoprotein mimics. Soft Matter. 2012;8:7909–7918. doi: 10.1039/c2sm25779c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H.-Y., Wang J., Meng F., Jia Z.-K., Su Y., Bai Q.-F., Lv L.-L., Ma F.-R., Potempa L.A., Yan Y.-B., Ji S.-R., Wu Y. An intrinsically disordered motif mediates diverse actions of monomeric C-reactive protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:8795–8804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.695023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khreiss T., József L., Hossain S., Chan J.S.D., Potempa L.A., Filep J.G. Loss of pentameric symmetry of C-reactive protein is associated with delayed apoptosis of human neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:40775–40781. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205378200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okemefuna A.I., Stach L., Rana S., Buetas A.J.Z., Gor J., Perkins S.J. C-reactive protein exists in an NaCl concentration-dependent pentamer-decamer equilibrium in physiological buffer. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:1041–1052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.044495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potempa L.A., Maldonado B.A., Laurent P., Zemel E.S., Gewurz H. Antigenic, electrophoretic and binding alterations of human C-reactive protein modified selectively in the absence of calcium. Mol. Immunol. 1983;20:1165–1175. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(83)90140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang M.S., Black J.C., Knowles M.K., Reed S.M. C-reactive protein (CRP) aptamer binds to monomeric but not pentameric form of CRP. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011;401:1309–1318. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5174-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kresl J.J., Potempa L.A., Anderson B.E. Conversion of native oligomeric to a modified monomeric form of human C-reactive protein. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1998;30:1415–1426. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., Ferrin T.E. UCSF Chimera - A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laemmli U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Albani J.R. Principles and applications of fluorescence spectroscopy. Blackwell Sci. 2007 Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh S.K., Thirumalai A., Hammond D.J., Pangburn M.K., Mishra V.K., a. Johnson D., Rusiñol A.E., Agrawal A. Exposing a hidden functional site of C-reactive protein by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:3550–3558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.310011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Volanakis J.E. Human C-reactive protein: expression, structure, and function. Mol. Immunol. 2001;38:189–197. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(01)00042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smilgies D.M., Folta-Stogniew E. Molecular weight-gyration radius relation of globular proteins: a comparison of light scattering, small-angle X-ray scattering and structure-based data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2015;48:1604–1606. doi: 10.1107/S1600576715015551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vashist S.K., Venkatesh A.G., Schneider E.Marion, Beaudoin C., Luppa P.B., Luong J.H.T. Bioanalytical advances in assays for C-reactive protein. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016;34:272–290. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rzychon M., Zegers I., Schimmel H. Analysis of the physicochemical state of C-reactive protein in different preparations including 2 certified reference materials. Clin. Chem. 2010;56:1475–1482. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.147124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lakowicz J.R., Fluorescence Protein. 3rd ed. Springer; Baltimore: 2006. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy; pp. 529–575. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim S.D., Ryu J.S., Yi H.K., Kim S.C., Zhang B.T. Preliminary Proceedings of the Tenth International Meeting on DNA Computing (DNA10) 2004. Construction of C-reactive protein-binding aptamer as a module of the DNA computing system for diagnosing cardiovascular diseases; pp. 334–343. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kelly S.M., Jess T.J., Price N.C. How to study proteins by circular dichroism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 2005;1751:119–139. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edelman G.M., Gotschlich E.C. C-reactive protein: a molecule composed of subunits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1965;54:558–566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.54.2.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ji S.-R., Ma L., Bai C.-J., Shi J.-M., Li H.-Y., Potempa L.A., Filep J.G., Zhao J., Wu Y. Monomeric C-reactive protein activates endothelial cells via interaction with lipid raft microdomains. FASEB J. 2009;23:1806–1816. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-116962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwedler S.B., Amann K., Wernicke K., Krebs A., Nauck M., Wanner C., Potempa L.A., Galle J. Native C-reactive protein increases whereas modified C-reactive protein reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Circulation. 2005;112:1016–1023. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.556530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oliveira E.B., Gotschlich E.C., Liu T.Y. Primary structure of human C-reactive protein. J. Bological Chem. 1979;254:489–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.