Highlights

-

•

This article indicated that the both behaviors of Congo red and insulin were derived from

-

•

a driving force related to the hydrophobic hydration.

-

•

∙The amyloid formation of insulin was induced predominantly gripped by hydrophobic hydration and an electrostatic shielding effect.

-

•

∙This study is trigger for conformational change of amyloid fibrils and related Congo red behavior.

Keywords: Congo red, insulin, amyloid fibrils, DLVO theory, hydrophobic hydration

Abstract

Amyloid fibrillation is provoked by the conformational rearrangement of its source. In our previous study, we claimed that the conformational rearrangement of hen egg white lysozyme requires intermolecular aggregation/packing induced. Our proposed causality of the aggregation and amyloid formation was demonstrated by the quantitative dependence of amyloid fibrillation on pH difference from its isoelectric point (pI) and on the square root of ionic strength in order to reduce the intermolecular repulsion due to the shielding effect of electrolytes (DLVO effect). When Congo red has dianionic form at the pH higher than its pKa, it forms ribbon-like micelle colloids under lower ionic strength, while it loses electrostatic repulsion and aggregates to be emulsified in the octanolic phase under the higher ionic strength. These behaviors of Congo red were resembling to molecular assembly of surfactants. In contrast, the amyloid formation of insulin was proportional to the square root of ionic strength at the pH lower than its isoelectric point. Therefore, the trigger for conformational rearrangement of amyloid fibrillation is predominantly gripped by hydrophobic hydration and an electrostatic shielding effect. We concluded that the both behaviors of Congo red and insulin were derived from a driving force related to the hydrophobic hydration.

1. Introduction

Amyloidosis is associated with an amyloid fibril, a characteristic protein assembly of a laminating β-sheet. [1], [2], [3] Proteins that form amyloids are involved in 38 diseases, such as primary systemic amyloidosis, dialysis-related amyloidosis, familial amyloid polyneuropathy, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and diabetes type-II. [4], [5], [6], [7] Although genetic and structural similarities/conservations are not observed among the amyloidogenic proteins, amyloid fibrils generated by their aggregation share certain characters: [8,9] and aggregates typically form a cross-β-sheet structure through the nucleation and growth phases. [10], [11], [12], [13], [14] Through the pathogenesis and propagation of amyloid-related diseases, the most important events are nucleation, which typically progresses very slowly. Once nuclei are formed, monomers or oligomers associate onto the ends of the nuclei, resulting in rapid growth. [2,15]

Human insulin (HI, Scheme 1a) is known as one of the proteins that form amyloid fibril formation. [16] When insulin is repeatedly injected into the same sites for the treatment of diabetes, amyloid fibrils or insulin balls could be formed under the skin. [17] They can interfere with insulin absorption and cause poor glycemic control. [18,19] It is important to investigate the mechanism of insulin amyloid fibril formation because of its effect on diabetes treatment. [20] HI is a 51-amino-acid peptide hormone whose aqueous solution consists of an equilibrium mixture of hexameric, tetrameric, dimeric, and monomeric units. [21] Hexamer, which plays the role of a biological storage form, comprises the majority of the mixture in the presence of Zn2+ at neutral pH, whereas the monomer appears in 20% AcOH at pH 1.8, and the dimer is observed in 20 mM HCl at pH 1.7. [22] This indicates that dispersion of monomeric insulin is allowed under the condition of a high concentration of amphiprotic dissolution aid (protonated AcOH), whereas oligomers would be favorable for dissolution into aqueous solutions. Insulin units in oligomers are thought to be hydrophobic interfaces, which might usually be buried in contact regions among associated insulin molecules. [23,24] Therefore, aggregation of insulin units requires exposure of this contact region to the aqueous solution. [25] This exposure of certain hidden/covered hydrophobic residues was the first step in the aggregation of monomeric insulin, and it involved an assumption that the driving force for insulin aggregation into amyloids is hydrophobic interactions. [26,27] Could such a conformational rearrangement, however, be allowed against a thermodynamic disadvantage? Insulin is known to have a high tendency to fibrillate at hydrophobic surfaces formed at the air-water interface induced by vigorous stirring. [26,27] This perturbation of polar solvent order results in the exposure of hydrophobic residues inside insulin molecules.

Scheme 1.

The structure of (a) insulin (PDB: entry 3I40), (b) thioflavin T, (c) Congo Red.

Thioflavin T (ThT, Scheme 1b) is a benzothiazole derivative dye that has been widely used to visualize the cross-β-architectures in amyloids as its fluorescence intensity increases at approximately 480 nm upon interaction with the cross-β-strand ladders. [28,29] ThT contained in micelles binds amyloid fibrils, and the ThT molecule with twisted conformation fluoresces brightly upon binding to the amyloid surface. [30,31] Similarly, Congo red (CR, Scheme 1c), whose binding is monitored by its characteristic yellow-green light refraction observed with cross-polarization, is used to detect the presence of amyloids in tissue sections and for in-vitro characterization of amyloid fibrils. [33,34] The bound CR exhibits birefringence under polarized light. Although the binding of ThT and CR is not specific to amyloids in tissue sections, the CR assay is performed under extreme conditions of 50%–80% ethanol, high salt concentration, and alkaline pH to promote amyloid binding. [33,34] The absorption spectrum of aqueous CR solutions shows three large peaks in the ultraviolet-visible light range. [34] CR is a pH-dependent halochromic reagent; in solutions with pH < 3.0, the amphoteric-charged neutral species has an absorption maximum at 560 nm, whereas at pH > 5.2, the divalent anionic disulfonate has an absorption maximum at 480 nm. [35,36] A study of the structure of CR in different media suggested that it has a different molecular structure in water compared to that in aqueous NaCl solutions. [37] However, the authors of this study did not determine the influence of ionic strength (J) on the pattern of the ultraviolet-visible spectrum. Other self-assembling organic molecules form rod- or ribbon-like supramolecular structures in solution. [35] The degree of twisting in the assembly arrangement of CR molecules decreases when the charges are shielded, allowing for greater overlap of the terminal aromatic rings, thereby resulting in an increase in the stacking interaction. [37] CR can also solubilize amyloids and suppress their toxicity by playing a role similar to that of a detergent. [38,39] CR may thus be considered as a new protein-ligand with possibly wide-ranging medical applications in medical diagnostic studies. [40]

Amyloid fibrillation of proteins, which can be highly variable, is influenced by temperature, pH, and ionic strength (J). [14,33,41] We assumed that the interaction between Congo red and β-strand segments of amyloid fibrils would resemble the intermolecular interaction of amyloid since Congo red is clinically used as a fluorescent indicator that binds with amyloid fibrils, as described above. CR forms aggregates as a self-assembling organic molecule, analogous to the fibrillation of amyloids. CR also has a strong affinity for amyloids. Hence, amyloids can be detected based on CR binding. Furthermore, while CR is an organic compound and insulin is a protein, both exist as association colloids in solution. The purpose of this study was to demonstrate the use of CR as an aggregation model for amyloids and to investigate the dependence of the aggregated forms of amyloids on pH or J. It was confirmed that CR aggregation was dependent on J at a pH lower than the pKa. It was suggested that aggregates of CR were formed based on the theory of Derjaguin, Landau, Verwey, and Overbeek (DLVO), [42] which explains the stability of a hydrophobic colloid solution. Furthermore, we investigated the similarity of CR to amyloidogenic proteins such as insulin, which is a readily available protein for which a method for amyloid formation has been established. [14] We also examined the common physicochemical conditions that induce CR aggregation and amyloid fibril formation.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

CR and ThT were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Recombinant human insulin (rHI) was purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan). These reagents and other reagents were of the highest grade commercially available. In the CR experiments, saline media were buffered with citrate/HCl to ensure that the pH was not higher than 4, with sodium phosphate to obtain a pH in the range of 5–7, and with sodium borate to ensure that the pH was not less than 9. In the rHI experiments, the pH of the buffered saline was balanced with citrate/phosphate. The concentration of the buffering acids was 10 mmol/L. The J value was adjusted by adding the required volume of the NaCl stock solution.

2.2. Measurements of the 1-Octanol/Water Partition coefficient

The partition coefficient was determined by the shaking-flask method. [43,44] Aqueous sample solutions at various pH values were combined with equivalent volumes of water-saturated 1-octanol and subsequently placed on a shaker for 24 h at 25°C. Concentrations of equilibrated aqueous and octanolic phases were measured using a DU 720 ultraviolet/visible-light spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Calibrations were performed for 1-octanol-saturated aqueous buffers at high pH and water-saturated 1-octanol.

2.3. Evaluation of amyloid fibrillation by rHI aggregation

The rHI stock solution was prepared by dissolving rHI (10 mg/mL rHI). Solutions were diluted with phosphate buffers at pH 3.3, 4.3, 5.3, 6.3, and 7.3, and adjusted to a specific J (rHI concentration of 0.1 mg/mL). The rHI sample solutions were then subjected to three cycles of a combined process of heating at 90°C for 45 min and subsequent shaking at room temperature for 30 min, according to E. Chatani et al. [14] The supernatants of the heat-processed sample solutions were collected by centrifugation at 15000 rpm for 20 min. The protein concentrations were assayed by colorimetry using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA)-copper(I) complex and subsequently calculated using the following equation:

| (1) |

Calibration curves were obtained using intact rHI as standards. [45]

2.4. Zeta potential of the particle dispersion

The zeta potentials of 100 particles were measured using a ZEECOM analyzer (Microtec Co., Funabashi, Japan). rHI samples were dissolved in solutions buffered at various pH values and adjusted to different values of J. The samples (J = 0.03) were analyzed immediately after preparation to avoid aggregate formation. A current of 10 mV was used for the measurements.

2.5. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra

FTIR spectra were measured using an FTIR spectrophotometer with a UATR accessory (PerkinElmer, Kanagawa, Japan) using 20 μL of the sediment obtained after centrifuging the heat-processed sample solutions. The FTIR spectrum was monitored at room temperature by collecting 64 interferograms. The resultant spectra were separated into several peaks by the Gaussian function and fitted to calculate the secondary structural ratio in the sediment, the ratio of the α-helix structure to the β-sheet structure. The equation for the Gaussian function is as follows:

| (2) |

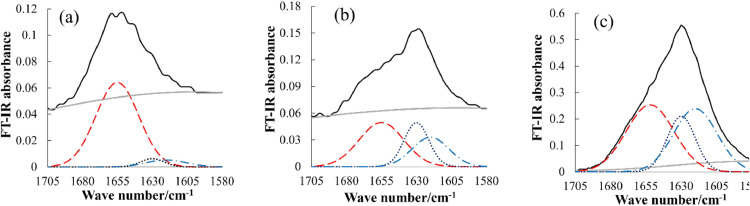

where y0 is the baseline, A is the intensity of a peak, ν is the wavenumber, σ is the peak width, and n is the number of components. We selected three components (n): the peaks of α-helix at the wavenumber of 1655 cm−1, β-sheet at 1630 cm−1, and β-strand at 1620 cm−1. [46]

2.6. ThT fluorescence of aggregated proteins

Fluorescence intensities were measured using an RF-5300PC spectrofluorometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Emission at the wavelength of 480 nm was induced by excitation at 420 nm for rHI. The heat-processed sample solutions were pre-stained with ThT (rHI concentration of 0.01 mg/mL, ThT concentration of 1 µg/mL). An unheated sample was used as a control.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Aggregation and emulsification of CR at oil/water interface

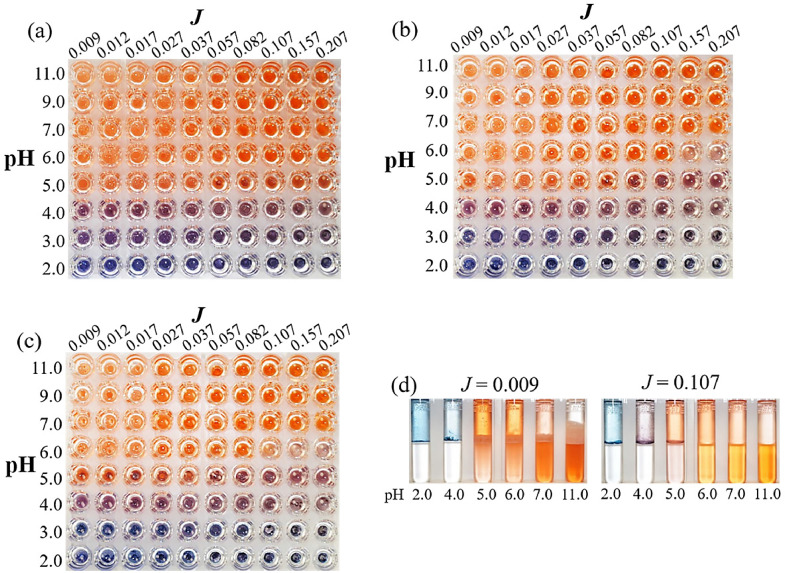

CR solution, aggregation, and emulsion were observed at the interface between 1-octanol and aqueous phases in a 96-well microplate. In the aqueous phase, the pH and the ionic strength J of CR solutions with a final concentration of 100 µmol/L were adjusted to obtain the ranges of 2.0-11.0 and 0.009-0.207, respectively. Subsequently, 1-octanol phase was added at a volume equivalent to that of the aqueous phase, and Figure 1a shows photographs taken immediately after the addition of the 1-octanol phase. The aggregated particles of the amphoteric-charged neutral species with the visible absorption at a wavelength of about 560 nm (notated as “560-Blue”) were obtained under all values in the range of J at pH 2.0, whereas those of the monovalent anion with the absorption at about 530 nm (as “530-Purple”) were observed at pH 3.0 and pH 4.0. In the pH range of 5.0-11.0, the divalent anion with absorption around 480 nm (as “480-Red”) was dissolved in both the aqueous and 1-octanol phases. With lower J values at higher pH, the contents in the wells were emulsified with a cloudy white color on the 480-Red solutions. As shown in Figure 1b, taken after 6 h and in Figure 1c taken after 24 h, the initially formed 530-Purple aggregates at pH 3.0 gradually transformed to 560-Blue, while the 530-Purple aggregates were gradually synthesized in wells with higher J values at pH 5.0.

Figure 1.

CR aggregates at the oil/water interface from J = 0.009 to J = 0.207 at pH 2.0–11.0 (a) immediately after partition, (b) 6 h after partition, and (c) 24 h after partition. Views from the top of a 96-well microplate (a–c), and side view of test tubes (d) are shown.

As shown in Figure 1d, the aggregations and emulsions were analyzed in detail from the side of test tubes containing 25 µmol/L CR solution and 1-octanol (including measurements with UV-Vis spectrophotometry). Oil phases were present in the upper halves of the test tubes, and aqueous phases were present in the lower halves. A cloudy white emulsion in the oil phase above the water/oil interface was observed at a high pH and J = 0.009 (see Figure 1c). The volume of the emulsion layer increased over time at J ≤ 0.017 and pH ≥ 5.0, and the borderline of the water/oil interface sequentially decreased. CR undergoes self-aggregation due to a stacking interaction at low pH and forms a ribbon-like micelle structure at high pH. [37,47] Accordingly, CR might be stabilized via the formation of a ribbon-like micelle structure [32] with its anionic form at pH > 6.0, while by anionic self-aggregation at pH < 5.0. At pH 2.0 and 4.0, CR was adsorbed on glass surfaces. The oil phase appeared blue or purple, but it was actually clear. This suggested that the formation of CR aggregations progressed at the oil/water interface and the oil/glass interface. The aggregation mechanism of CR was different at both pH values (pKa = 4.9). A cloudy white emulsion of CR was formed overtime at low J and high pH.

To verify whether this emulsification was specific to CR, emulsifications of Evans blue and that of methyl orange, anionic analogs of CR, were performed (see Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). At low J and high pH, these dyes formed similar white emulsion layers (see Figure S2). Furthermore, the emulsion layers were immiscible with the 1-octanol phase, and their dispersed phases consisted of stabilized oil-in-water particles with a size sufficient to account for Mie scattering. The same experiments were carried out for trypan blue and direct blue 1 (see Figure S1), known as other CR analogs, and both dyes also formed an emulsion (data not shown). Because CR and the other four dyes have negatively charged functional groups at their ends, intermolecular repulsion is predominant at low J. On the contrary, at high J, the repulsive interaction is shielded by electrolytes, promoting the aggregation of negatively charged CR. Based on this assumption, although the divalent anion of CR is dispersed at low J due to repulsion, it likely has the capacity of amphiphilic properties to form an emulsion. Lendel et. al. also reported the surfactant properties of CR. [38]

3.2. Zeta potential and partition coefficient of CR

Figure 2 shows the zeta potentials of CR solution/dispersion under lower and higher J values at various pH to examine the tendency of aggregation. The negative zeta potential was consistently proportional to pH at low ionic strength (J = 0.020). However, at high ionic strength (J = 0.205), it decreased with a similar slope dependent on pH until 7.0, and switched to zero, with a pH value higher than 7.0. In the pH range of 2.0–7.0, the negative charge of the particles increased as the proportion of monovalent or divalent anionic CR species increased with an increase in pH. Under such acidic conditions, the zeta potential of the particles showed linearity independent of the J value. At pH > 7.0, which is higher than the pKa (4.9) of CR by an order of 2 or more, the continuous increase in the negative charge required low ionic strength. In solutions with higher J values, we consider that repulsive interactions between the negative charges of the anionic CR species were shielded by the electrolytes and observed the neutralization of the apparent negative charges.

Figure 2.

Zeta potential of CR in solutions of J = 0.02 (●) and J = 0.20 (▲) in the pH range from 2.0 to 11.0.

The outcomes so far rationalized why the forms of CR, namely aggregation and emulsion, were determined by the molecular charges of CR. In the pH range of 2.0-4.0, 560-Blue, which predominantly contains amphoteric-charged neutral species, loses its apparent electrostatic repulsion independently at low and high J values, so that its own hydrophobic intermolecular interaction enhances aggregation. At pH 5.0, approximated to the pKa value of CR, 530-Purple, which mainly contains monovalent anions, was partially aggregated. The electrostatic repulsion was shielded by electrolytes under high ionic strength J, and the aggregation increased gradually. At pH higher than pKa, as the 480-Red contains divalent anions, which exhibit negative charges at both ends of the tandem azo dyes, the hydrophobic centers of the CR molecules are thought to be associated by stacking to form a helical ribbon-like micelle structure. [37] Under this condition, since the ribbon-like micelles are stabilized by the shielding effect of electrolytes at high ionic strength J, the apparent zeta potential approached zero. At low ionic strength J, even at high pH, however, the electrostatic repulsion would be too large to maintain the ribbon-like micelles. [32] In contrast, the divalent anion alone is finitely solved in an aqueous solution because of its hydrophobicity. Here, we considered that the water-in-oil emulsion is composed of exhausted CR from the aqueous phase to the 1-octanolic phase. In this case, a dominant factor behind emulsification is possibly related to CR not being soluble in an aqueous solution, which indicates hydrophobicity.

Subsequently, to measure the hydrophobicity of the 480-Red, 530-Purple, and 560-Blue, the apparent 1-octanol/water partition coefficients D for 5 mL of 25 µmol/L CR solution at various pH values were examined. At acidic pH, the formation of aggregates at the interface between 1-octanol and the 10 mmol/L sodium phosphate buffer solution prevented the measurement of the partition coefficient. The CR aggregations dissolved in either 1-octanol or aqueous solution and were adsorbed at the oil/water and oil/glass interfaces. Since the CR aggregate was similarly insoluble or poorly soluble in butyl acetate, hexane, and cyclohexane, the decisive factor behind aggregation did not seem to be the hydrophobicity of the amphoteric-charged neutral species observed at the acidic pH. We speculate any formation of amphoteric pairs or clusters of CR, but no evidence is available. This aggregation is reversibly dispersed into basic solutions formed upon the addition of an alkaline solution.

Although the slope of the linear correlation between concentrations in the 1-octanol and aqueous phases (CO and CW, respectively), D, has been previously determined for various drugs, [46] we analyzed the relationship between CO and CW of CR. At high pH, the curve for the apparent partition coefficient (D = CO/CW) versus pH was explained by either a traditional plateau or a bilinear polygraph. [43,44] In Figures 3a and 3b, CO became saturated because the free CR in 1-octanol was in equilibrium with free CR in water, and CR aggregated at the 1-octanol/water interface. A similar correlation (i.e., saturation curve) between CO and CW was also observed for methyl orange and other azo pigments, in addition to CR. The CO saturation varied depending on the electrolyte concentration in the aqueous solution, as indicated by the J values in Figures 3a and 3b. Since the pH of the aqueous phase was adjusted by the addition of NaOH solution, J was varied as a function of pH such that D increased at pH 11.0 and pH 12.0. The D = CO/CW was determined under J = 0.020 and J = 0.205 at various pH values, and the following equation from Langmuir's absorption isotherm theory was applied for the analysis of saturation curves:

| (3) |

where the saturation point n represents the saturated CO and the association constant K corresponds to the reciprocal CW under conditions that yield 50% saturated CO.

Figure 3.

Apparent partition coefficients of CR at J = 0.020 (a) and J = 0.205 (b) at pH 5.0 (■), pH 5.5 (□), pH 6.0 (●), pH 6.5 (○), pH 7.0 (◆), pH 9.0 (◇), and pH 11.0 (▲); and theoretical association constant K (c) corresponding to the reciprocal Cw under conditions of 50%-saturated Co and the theoretical saturation point n (d) at J = 0.020 (×) and J = 0.205 (△). The y-axis of Figure 2c and 2d are represented on a logarithmic scale.

In Figure 3c, the higher K values obtained under J = 0.020 at the low pH indicated its immediate saturation in the aqueous phase, whereas its aqueous solubility was elevated at high pH. The K values were less than 0.2 under J = 0.205, demonstrating that there was very little CR in the octanol phase independent of pH. In Figure 3d, the parameter n obtained at low J = 0.020 decreased as a function of pH, corresponding to a change in negative charge, consistent with the increasingly negative zeta potential at high pH shown in Figure 2. In contrast, the n values at J = 0.205 hardly changed, even when the pH was increased. These results indicate that CR is stabilized in the aqueous phase with a high J value, that is, the amounts of CR in both water and 1-octanol are independent of pH.

In the pH range of 7.0–11.0, as shown in Figures 3a and 3b, the apparent slopes of CO to CW would be somewhat invariable. The molecular association in CR solutions induced the formation of characteristic ribbon-like micelles dispersed in an aqueous solution by the electrostatic shielding effect of electrolytes. [32,42] Partition equilibration would be maintained between this aqueous micelle dispersion and 1-octanol solution of CR. In contrast, regardless of the apparent D (i.e., hydrophobicity) of CR was low under the lower J value at pH 7.0-11.0. Although these conditions allowed molecules of CR to form divalent anions, we obtained a cloudy white emulsion, as shown in Figure 1d. We considered that the formation of ribbon-like micelles requires a high concentration of its counter cations (Na+, etc.) to stabilize in an aqueous solution. If the counter cations were lost, then the divalent anion form of CR would be too hydrophobic to dissolve in the aqueous phase. Thus, the divalent anion is amphiphilic to form a water-in-oil emulsion in the 1-octanol phase, as previously stated. CR is known as a pH-indicating halochromic reagent, coloring blue (as the 560-Blue) at an acidic pH and red (as the 480-Red) at a pH higher than its pKa. The color change could be rational, considering that the sequentially conjugated conformation of aromatic rings and double bonds (which may color Navy Blue) is collapsed by ribbon-like micelle formation and amphiphilic emulsification at pH higher than pKa to transform to a bending conformation. (The color of azo-naphthyl derivatives is known as Bordeaux Red.)

3.3. Denaturation of heat-treated human insulin

In our previous study, we analyzed the amyloid formation of hen egg-white lysozyme. [48] Comparatively, insulin is clarified where is conformational converting region (the SLYQLENY segment at 12-19 in A chain) neighboring to a steric zipper interface β-strand (the LVEALYL segment at 11-17 in B chain) important to form the amyloid fibrils. [49] Thus, we examined rHI to explore the mechanism of amyloid fibrillations. Concentrations of protein remaining in centrifuged supernatants of the heat-treated rHI solutions at various pH values were measured using the BCA assay. [45] In Figure 4a, no denatured rHI precipitated at pH 6.3-7.3, independent of the J value. At a pH of 5.3 or less, the rHI concentration decreased as J increased. This indicated that the lower the pH and the higher the value of J, the higher the precipitation of denatured rHI.

Figure 4.

(a) The change of rHI concentration with respect to pH and ionic strength in solution with no heating (○), J = 0.015 (●), J = 0.03 (■), J = 0.09 (◆), J = 0.16 (▲), J = 0.36 (×). (b) Isoelectric point measurement by zeta potential (ζ).

As shown in Figure 4b the inset, the zeta potential disappeared at pH 5.3, and positively charged rHI (about +15 mV) was observed at lower pH. Aggregation of the heat-treated rHI was considered to be facilitated by the electrostatic shielding effect of the electrolyte under the higher J condition at low pH. According to the measurements of zeta potential, the charge of the protein was canceled at pI of pH 5.3, the protein was in an amphoteric-charged neutral state. [50] The electronic double layer of the water-soluble particles allowed them to disperse in diluted electrolyte solutions at lower J values. If the number of electrolytes increased, H2O was consumed by the electrolytes to lack H2O accessible to the positively or negatively charged surfaces of the amphoteric-charged neutral protein. This is the reason that the higher the value of J, the more rHI precipitated/aggregated.

3.4. Aggregation of human insulin

The centrifuged precipitates were obtained by heat treatment of rHI solutions under various J conditions at various pH values, in accordance with the experiments described in the previous section. The precipitates were analyzed on their ATR-FTIR spectra, which were reproduced by summation of the i-th Gaussian function with peak height Ai, peak width σi, and mean wave number νi were optimized (cf. Equation 2). The peaks of α-helix, β-sheet, and β-strand were assigned at wavenumbers of 1655 cm−1, 1630 cm−1, and 1620 cm−1, respectively. [51], [52], [53] As no rHI aggregations were produced at pH 6.3, and pH 7.3, ATR-FTIR spectra of the drops of solutions were similarly measured and analyzed. Figure 5 shows the peak decompositions of the ATR-FTIR spectra of the rHI precipitates prepared at pH 3.3. In the control group, rHI contained the α-helical signal occupying the largest part. We found a conformational conversion from the α-helix to the β-structures in the rHI aggregates.

Figure 5.

Peak separation of FT-IR spectra of rHI by Gaussian fitting at pH 3.3 and (a) control, (b) J = 0.03, and (c) J = 0.36. Native spectra: solid line, α-helix: dashed line, β-sheet: dotted line, β-strand: dashed dotted line, baseline: gray line.

The area under the curve (AUC) of each Gaussian component is given as the product of Ai and the square root of 2πσi2. The secondary structure ratio when the α-helix structure in the obtained spectrum was assumed to be 100% was calculated from the following equation:

| (4) |

Figure 6 demonstrates that the quantity of conformational conversion from α-helix to β-structures depended on the J value at any pH. The conversion was promoted under lower J values at low pH, whereas it stagnated under relatively high J conditions at pH higher than pI = 5.3. This was consistent with the fact that insulin formed a β-structure in an acidic environment, as suggested by Chatani et al. [14] In the previous section, we described that the concentration of rHI remaining in the centrifuged supernatant was found under higher J conditions at lower pH. Focusing on the relationships of rHI precipitation/aggregation to J at various pH values (Figure 4), it tended to saturate at more than J = 0.09. In contrast, the relationship of β-structure conversion to J demonstrated a similar trend only at pH 3.3 (Figure 6a). At higher pH, the conspicuous conversions seemed to require a slightly higher J value (Figures 6b-6e). We considered that the β-structure conversion progressed more under the condition that led to the production of a higher amount of precipitates rather than under the condition that resulted in little precipitation.

Figure 6.

Transition of secondary structure of rHI at (a) pH 3.3, (b) pH 4.3, (c) pH 5.3, (d) pH 6.3 and (e) pH 7.3 by ATR-FTIR. The red and blue bars represent α-helix or β-sheet structure content, respectively.

Both precipitation/aggregation and conformational conversion to β-structures are strictly identical to amyloid fibrillation or its precursor formation. In general, amyloids and precursors are detectable with ThT bound to these cross-β-sheets, which is informed by an attribute fluorescent response. [28,34,54] Figure 7a shows the difference in the ThT fluorescence intensity of rHI with respect to pH, compared to samples prepared under various J values. At pH 6.3, and 7.3, insulin showed little fluorescence intensity at any J value, while at pH 3.3, 4.3, and 5.3, (= pI), it showed a fluorescence intensity dependent on J values. Figure 7b shows the ThT fluorescence intensity of the heat-treated rHI solution with respect to the square root of the J value. In our previous study conducted with heat-treated lysozyme, amyloid fibrillation showed a linear correlation with the J1/2 value. [48] In light of this, the linearity of the ThT fluorescence intensity proportional to the square root of J was inspected.

Figure 7.

(a) ThT fluorescence intensity of rHI depending on pH: no heating (○), J = 0.015 (●), J = 0.03 (■), J = 0.09 (◆), J = 0.16 (▲), J = 0.36 (×) measured at 480 nm. (b) ThT fluorescence intensity of rHI depending on J1/2: pH = 7.3 (○), pH = 6.3 (●), pH = 5.3 (■), pH = 4.3 (▲), pH = 3.3 (×) measured at 480 nm.

As shown in Figure 7b, at pH lower than pI, ThT fluorescence increased proportionally to the J1/2 value until 0.4 (J ≤ 0.16), whereas the plot under J1/2 = 0.6 (J = 0.36), was much lower than the extension line. Since the mass ratio of insulin (5.8 kDa) to lysozyme (14.3 kDa) is 2/5, the molar ratio of insulin to lysozyme on the surface of a sphere of the same volume was determined as (51/3/21/3)2 = 1.84. Since the sphere of the same volume contains 5/2 times of insulin than that of the lysozyme, smaller insulin is of disadvantage for ThT staining to be 1.84/ (5/2) = 0.72 times rather than larger lysozyme. At a pH higher than pI, no ThT fluorescence was observed under any J values. In Figures 6d and 6e, the resultant precipitate shows a converted β structure, but the product did not contain any components stained by ThT. The steric zipper interface, the LVEALYL segment at 11-17 in the B chain has an acidic residue ay E. Hence, it would be electrostatically repulsive to cross-link. Thus, it is reasonable that rHI aggregation does not lead to amyloid fibrillation. As shown in Figure 7b, at pH 5.3 equivalent to pI, obvious enhancements of amyloid formation were confirmed with J1/2 = 0.6. According to this averaged value and assumed linearity of fluorescence to J1/2, higher intensities were expected under J1/2 values of 0.2-0.4. However, the resulting values were lower. Under this condition, the acidic residue in the steric zipper interface is partially acid dissociated. This could be the reason for the small amount of ThT fluorescence. The formation of amyloid of rHI incubated at acid pH was also confirmed by fluorescence evaluation by CR (Fig. S4). Along with this, I cite a paper that evaluated the presence of curli, a functional amyloid fiber of Escherichia coli that acts as a cilia, by CR. [55] Although there are also reports on the interaction between native insulin and CR, UV-vis spectra did not show such an interaction under these conditions (Fig. S5). [56]

3.5. More discussion

Since Congo red (CR) is clinically used as a fluorescent indicator to bind with amyloid fibrils, the mode of interaction between CR and β-strand segments of amyloid fibrils is expected to resemble the intermolecular interaction of amyloid. CR did not demonstrate its own 1-octanol/water partition coefficient. This is consistent with the fact that CR did not maintain any molecular dispersion but showed organizations such as aggregation at low pH, an amphiphilic emulsion under low ionic strength at high pH, and a ribbon-like micelle under high ionic strength at high pH. At a pH higher than its pKa = 4.9, the steric structure of divalent anionic CR was squeezed to a bending conformation, resulting in its red color. As the ionic strength increased at a pH lower than its isoelectric point, the more the recombinant human insulin (rHI) aggregated and the more thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence increased, indicating amyloid fibrillation. At higher pH values, aggregation contained no fibrillation because of an anionic residue in its steric zipper interface. Insulin has been reported to form oligomers, mainly dimers, tetramers, hexamers, etc. E. J. Nettleton, et al. reported that dimer association induced aggregate and fibrosis, and hexamer induced an assembly of fibrils with higher order structure. [57] They also reported that the association of insulin dimers to form large aggregates causes the natural helical structure to migrate to the β-sheet and the packing of the fibrous structure to proceed. In our study, conformational rearrangement of insulin amyloid fibrillation was controlled by hydrophobic hydration and an electrostatic shielding effect.

There are some points to note about the behavior of CR and insulin. CR takes two molecular states, an ionic type with a charge and a molecular type without a charge, by changing the pH with respect to pKa, and the molecules associate and aggregate to induce a conformational change like a ribbon-like micelle. On the other hand, the surface charge of insulin is positive or negative depending on the change in pH with respect to pI. At pH close to pI, insulin molecules became easier to approach due to the attenuation of electrostatic interaction and associated with each other, and further coagulated by the molecular distance approaching due to the change in ionic strength. As described above, it was confirmed that insulin is controlled not only by simple pH aggregation like CR but also by ionic strength as a colloidal molecule, so more verification is required than in the case of CR.

In the CR emulsion, CR micelle, and rHI amyloid fibrillation, these molecules were condensed in the particles excluded from the bulk aqueous solution. Alba, E. et al. reported that CRs stacked in a staircase pattern fit into the grooves formed when constructing an amyloid structure. [58] This behavior of CR proved that the groove specifically possessed by the amyloid fibril structure provided a hydrophobic environment for the CR molecule, which could not occur by simple dissolution in a solvent. The above report on the behavior of CR molecules supports the finding that the driving force in the conformational change of CR is hydrophobic hydration, which was found in this study. Therefore, the driving force for CR conformation change and rHI amyloid fibrillation would be hydrophobic hydration induced by being trapped in the water molecular network connected with potent hydrogen bonds.

4. Conclusion

The mode of CR was controlled by both pH and ionic strength. That likely has the capacity of amphiphilic properties to form an emulsion. By controlling the electrostatic repulsion of the molecular surface by pH and the presence of electrolyte, CR determines whether it becomes a ribbon-shaped micelle or a bending conformation. So that, the color change in CR could be rational. Aggregation of heat-treated rHI was promoted by controlling the molecular surface charge by pH and ionic strength and approaching a neutral state. As the number of electrolytes increases, H2O is consumed by the electrolyte, and there is a lack of H2O that can access the positively or negatively charged surface of the amphoteric charged neutral protein. This contributed to rHI aggregation. The rHI β-structural conversion proceeded under the condition of a large amount of precipitates, rather than the condition of a small amount of heat-treated rHI precipitates. In addition, due to the difference in pH with respect to pI, the formation of the rHI amyloid structure was different due to the presence of acidic amino acid residues. Both CR conformational changes and rHI amyloid formation are hydrophobic induced by molecular surface charge controlled by pH and ionic strength, that is, confinement in a water molecule network connected to strong hydrogen bonds. Promoted by hydration (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

The aggregation processes of Congo red and rHI at high ionic strength and each pH.

Author Contributions

T. Kasai and T. Wada drafted the manuscript and figures. T. Iijima, Y. Minami, T. Sakaguchi, T. Shiratori, and Y. Okayama are supporting investigations, R. Koga provided the experimental data for supplemental information. Y. Otsuka and Y. Shimada gave productive suggestions and experimental instructions. S. Goto supervised.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

Part of this research was supported by a Research Grant for Young Scientists from the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tokyo University of Science.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bbadva.2021.100036.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Dobson C.M. Protein folding and misfolding. Nature. 2003;426:884–890. doi: 10.1038/nature02261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uversky V.N., Fink A.L. Conformational constraints for amyloid fibrillation: the importance of being unfolded. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1698:131–153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson M.D., Buxbaum J.N., Eisenberg D.S., Merlini G., Saraiva M.J.M., Sekijima Y., Sipe J.D., Westermark P. Amyloid nomenclature 2020: update and recommendations by the International Society of Amyloidosis (ISA) nomenclature committee. Amyloid. 2020;27:217–222. doi: 10.1080/13506129.2020.1835263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmgren G., Ericzon B.G., Groth C.G., Steen L., Suhr O., Andersen O., Wallin B.G., Seymour A., Richardson S., Hawkins P.N. Clinical improvement and amyloid regression after liver transplantation in hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. Lancet. 1993;341:1113–1116. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)93127-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyle R.A., Greipp P.R. Amyloidosis (AL). Clinical and laboratory features in 229 cases. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1983;58:665–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westermark P., Wernstedt C., O'Brien T.D., Hayden D.W., Johnson K.H. Islet amyloid in type-2 human diabetes-mellitus and adult diabetic cats contains a novel putative polypeptide hormone. Am. J. Pathol. 1987;127:414–417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goate A., Chartier-Harlin M.C., Mullan M., Brown J., Crawford F., Fidani L., Giuffra L., Haynes A., Irving N., James L., Mant R., Newton P., Rooke K., Roques P., Talbot C., Pericak-Vance M., Roses A., Williamson R., Rossor M., Owen M., Ardy J. Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 1991;349:704–706. doi: 10.1038/349704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mecocci P., Polidori M.C. Antioxidant clinical trials in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1822:631–638. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joyner P.M., Cichewicz R.H. Bringing natural products into the fold—exploring the therapeutic lead potential of secondary metabolites for the treatment of protein-misfolding related neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011;28:26–47. doi: 10.1039/c0np00017e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sipe J.D., Cohen A.S. Review: history of the amyloid fibril. J. Struct. Biol. 2000;130:88–98. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blake C., Serpell L. Synchrotron x-ray studies suggest that the core of the transthyretin amyloid fibril is a continuous beta sheet helix. Structure. 1996;4:989–998. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke M.J., Rougvie M.A. Cross-β protein structures. I. Insulin fibrils. Biochemistry. 1972;11:2435–2439. doi: 10.1021/bi00763a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glenner G.G. The bases of the staining of amyloid fibers: their physico-chemical nature and the mechanism of their dye-substrate interaction. Prog. Histochem. Cytochem. 1981;13:1–37. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6336(81)80003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatani E., Imamura H., Yamamoto N., Kato M. Stepwise organization of the β-structure identifies key regions essential for the propagation and cytotoxicity of insulin amyloid fibrils. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:10399–10410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.520874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wetzel R. Kinetics and thermodynamics of amyloid fibril assembly. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:671–679. doi: 10.1021/ar050069h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ansari A.M., Osmani L., Matsangos A.E., Li Q.K. Current insight in the localized insulin-derived amyloidosis (LIDA): clinico-pathological characteristics and differential diagnosis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2017;213:1237–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2017.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dische F.E., Wernstedt C., Westermark G.T., Westermark P., Pepys M.B., Rennie J.A., Gilbey S.G., Watkins P.J. Insulin as an amyloid-fibril protein at sites of repeated insulin injections in a diabetic patient. Diabetologia. 1988;31:158–161. doi: 10.1007/BF00276849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagase T., Iwaya K., Iwaki Y., Kotake F., Uchida R., Oh-I T., Sekine H., Miwa K., Murakami S., Odaka T., Kure M., Nemoto Y., Noritake M., Katsura Y. Insulin-derived Amyloidosis and Poor Glycemic Control: A Case Series. Am. J. Med. 2014;127:450–454. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuzu K., Lindgren M., Nyström S., Zhang J., Mori W., Kunitomi R., Nagase T., Iwaya K., Hammarström P., Zako T. Insulin amyloid polymorphs: implications for iatrogenic cytotoxicity. RSC Adv. 2020;10:37721–37727. doi: 10.1039/d0ra07742a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagase T., Katsura Y., Iwaki Y., Nemoto K., Sekine H., Miwa K., Oh-I T., Kou K., Iwaya K., Noritake M., Matsuoka T. The insulin ball. Lancet. 2009;373:184. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muzaffar M., Ahmad A. The mechanism of enhanced insulin amyloid fibril formation by NaCl is better explained by a conformational change model. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e27906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmad A., Millett I.S., Doniach S., Uversky V.N., Fink A.L. Partially folded intermediates in insulin fibrillation. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11404–11416. doi: 10.1021/bi034868o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brange J., Dodson G.G., Edwards D.J., Holden P.H., Whittingham J.L. A model of insulin fibrils derived from the x-ray crystal structure of a monomeric insulin (despentapeptide insulin) Proteins. 1997;27:507–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeo S.D., Debendetti P.G., Patro S.Y., Przybycien T.M. Secondary structure characterization of microparticulate insulin powders. J. Pharm. Sci. 1994;83:1651–1656. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600831203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nielsen L., Khurana R., Coats A., Frokjaer S., Brange J., Vyas S., Uversky V.N., Fink A.L. Effect of environmental factors on the kinetics of insulin fibril formation: elucidation of the molecular mechanism. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6036–6046. doi: 10.1021/bi002555c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sluzky V., Tamada J.A., Klibanov A.M., Langer R. Kinetics of insulin aggregation in aqueous solutions upon agitation in the presence of hydrophobic surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991;88:9377–9381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sluzky V., Klibanov A.M., Langer R. Mechanism of insulin aggregation and stabilization in agitated aqueous solutions. Biotech. Bioengin. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1992;40:895–903. doi: 10.1002/bit.260400805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khurana R., Coleman C., Ionescu-Zanetti C., Carter S.A., Krishna V., Grover R.K., Roy R., Singh S. Mechanism of Thioflavin T binding to amyloid fibrils. J. Struct. Biol. 2005;151:229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biancalana M., Koide S. Molecular mechanism of thioflavin-T binding to amyloid fibrils. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1804:1405–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qin Z., Sun Y., Jia B., Wang D., Ma Y., Ma G. Kinetic mechanism of Thioflavin T binding onto the amyloid fibril of hen egg white lysozyme. Langmuir. 2017;33:5398–5405. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b00221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robbins K.J., Liu G., Selmani V., Lazo N.D. Conformational analysis of Thioflavin T bound to the surface of amyloid fibrils. Langmuir. 2012;28:16490–16495. doi: 10.1021/la303677t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khurana R., Uversky V.N., Nielsen L., Fink A.L. Is Congo red an amyloid-specific dye? J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:22715–22721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011499200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Puchtler H., Sweat F., Levine M. On the binding of Congo red by amyloid. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1962;10:355–364. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emmert G.L., Coutant D.E., Sweetin D.L., Gordon G., Bubnis B. Studies of selectivity in the amaranth method for chlorine dioxide. Talanta. 2000;51:879–888. doi: 10.1016/s0039-9140(00)00285-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones T.P., Porter M.D. Optical pH sensor based on the chemical modification of a porous polymer film. Anal. Chem. 1988;60:404–406. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mera S.L., Davies J.D. Differential Congo red staining: the effects of pH, non-aqueous solvents and the substrate. Histochem. J. 1984;16:195–210. doi: 10.1007/BF01003549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skowronek M., Stopa B., Konieczny L., Rybarska J., Piekarska B., Szneler E., Bakalarski G., Roterman I. Self-assembly of Congo red—A theoretical and experimental approach to identify its supramolecular organization in water and salt solutions. Biopolymers. 1998;46:267–281. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lendel C., Bolognesi B., Wahlström A., Dobson C.M., Gräslund A. Detergent-like interaction of Congo red with the amyloid β peptide. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1358–1360. doi: 10.1021/bi902005t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frid P., Anisimov S.V., Popovic N. Congo red and protein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res. Rev. 2007;53:135–160. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stopa B., Jagusiak A., Konieczny L., Piekarska B., Rybarska J., Zemanek G., Król M., Piwowar P., Roterman I. The use of supramolecular structures as protein ligands. J. Mol. Model. 2013;19:4731–4740. doi: 10.1007/s00894-012-1744-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Owczarz M., Motta A.C., Morbidelli M., Arosio P. A Colloidal description of intermolecular interactions driving fibril−fibril aggregation of a model amphiphilic peptide. Langmuir. 2015;31:7590–7600. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b01110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruiz-Cabello F.J.M., Maroni P., Borkovec M. Direct measurements of forces between different charged colloidal particles and their prediction by the theory of Derjaguin. J. Chem. Phys. 2013;138 doi: 10.1063/1.4810901. Landau, Verwey and Overbeek (DLVO) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tateuchi R., Sagawa N., Shimada Y., Goto S. Enhancement of the 1-octanol/water partition coefficient of the anti-inflammatory indomethacin in the presence of lidocaine and other local anesthetics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:9868–9873. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b03984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.OECD guidelines for the testing of chemicals. Phys.-Chem. Prop. 1995;1:2074–5753. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang T., Long M., Huo B. Competitive binding to cuprous ions of protein and BCA in the bicinchoninic acid protein assay. Open Biomed. Eng. J. 2010;4:271–278. doi: 10.2174/1874120701004010271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goormaghtigh E., Raussens V., Ruysschaert J.M. Attenuated total reflection infrared spectroscopy of proteins and lipids in biological membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1422:105–185. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(99)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Król M., Roterman I., Piekarska B., Konieczny L., Rybarska J., Stopa B., Spólnik P., Szneler E. An approach to understand the complexation of supramolecular dye Congo red with immunoglobulin L chain lambda. Biopolymers. 2005;77:155–162. doi: 10.1002/bip.20197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakaguchi T., Wada T., Kasai T., Shiratori T., Minami Y., Shimada Y., Otsuka Y., Komatsu K., Goto S. Effects of ionic and reductive atmosphere on the conformational rearrangement in hen egg white lysozyme prior to amyloid formation. Coll. Surf. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2020;190 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.110845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ivanova M.I., Sievers S.A., Sawaya M.R., Wall J.S., Eisenberg D. Molecular basis for insulin fibril assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:18990–18995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910080106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Conway-Jacobs A., Lewin L.M. Isoelectric focusing in acrylamide gels: use of amphoteric dyes as internal markers for determination of isoelectric points. Anal. Biochem. 1971;43:394–400. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mezzenga R., Fischer P. The self-assembly, aggregation and phase transitions of food protein systems in one, two and three dimensions. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2013;76 doi: 10.1088/0034-4885/76/4/046601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holzwarth G., Doty P. The ultraviolet circular dichroism of polypeptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965;87:218–228. doi: 10.1021/ja01080a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greenfield N., Fasman G.D. Computed circular dichroism spectra for the evaluation of protein conformation. Biochemistry. 1969;8:4108–4116. doi: 10.1021/bi00838a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chaturvedi S.K., Khan J.M., Siddiqi M.K., Alam P., Khan R.H. Comparative insight into surfactants mediated amyloidogenesis of lysozyme. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016;83:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reichhardt C., Cegelski L. The Congo red derivative FSB binds to curli amyloid fibers and specifically stains curliated E. coli. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klunk W.E., Pettegrew J.W., Abraham DJ. Quantitative Evaluation of Congo Red Binding to Amyloid-like Proteins with Beta-pleated Sheet Conformation. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1989;37:1273–1281. doi: 10.1177/37.8.2666510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nettleton E.J., Tito P., Sunde M., Bouchard M., Dobson C.M., Robinson C.V. Characterization of the Oligomeric States of Insulin in Self-Assembly and Amyloid Fibril Formation by Mass Spectrometry. Biophys. J. 2000;70:1053–1065. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76359-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Espargaró A., Llabrés S., Saupe S.J., Curutchet C., Luque F.J., Sabaté R. On the Binding of Congo Red to Amyloid Fibrils. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:8104–8107. doi: 10.1002/anie.201916630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.