Abstract

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) finely tunes the balance between survival and death to control homeostasis. XIAP is found aberrantly expressed in cancer, which has been shown to promote resistance to therapy-induced apoptosis and confer poor outcome. Despite its predominant cytoplasmic localization in human tissues, growing evidence implicates the expression of XIAP in other subcellular compartments in sustaining cancer hallmarks. Herein, we review our current knowledge on the prognostic role of XIAP localization and discuss molecular mechanisms underlying differential biological functions played in each compartment. The comprehension of XIAP subcellular shuttling and functional dynamics might provide the rationale for future anticancer therapeutics.

Keywords: XIAP subcellular localization, Resistance to apoptosis, Molecular functional mechanisms, Prognostic marker, Cancer

Abbreviation list

- Akt

Protein kinase B

- Apaf-1

Apoptotic protease activating factor 1

- BAK

Bcl-2 homologous antagonist/killer

- BAX

Bcl-2-associated X protein

- BIR

Baculoviral IAP repeat

- Cdc42

Cell division control protein 42 homologue

- CDK1

Cyclin-dependent kinase 1

- c-Jun/AP-1

Jun proto-oncogene/Activator protein 1

- c-Myc

Cellular Myc

- COMMD1

copper metabolism MURR1 domain-containing 1

- c-Raf

Raf proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase

- CRM1

Chromosomal maintenance 1

- C-terminal

Carboxi terminal

- DLBCL

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- E2F1

E2F transcription factor 1

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- ERK

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- GDP

Guanosine diphosphate

- Gro/TLE

Groucho protein/Transducin-like enhancer

- GSK-3

Glycogen synthase kinase 3

- GTP

Guanosine triphosphate

- HIF-1

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1

- IAP

Inhibitor of apoptosis protein

- IKKβ

IκB kinase beta

- IKKε

IκB kinase epsilon

- LC3-II

Microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MAPKK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- Mdm2

Mouse double minute 2 homolog

- MEKK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase

- MMP2

Matrix metalloproteinase-2

- MNK

MAPK interacting kinase

- NES

Nuclear export signal

- NFκB

Nuclear factor kappa B

- NLS

Nuclear localization signal

- NPC

Nuclear pore complex

- Omi/HtrA2

High-temperature requirement serine protease A2

- OMM

Outer mitochondrial membrane

- p62/SQSTM1

Sequestosome 1

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PP2A

Protein phosphatase 2

- PTEN

Phosphatase and tensin homolog

- PTMs

Post-translational modifications

- Rab

Tas-related protein

- Rac1

Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1

- Ran

Ras-related nuclear protein

- Rho

Ras homologous

- RhoGDI

Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor

- RhoGDIβ

Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor beta

- RING

Really interesting new gene

- Smac/DIABLO

Second mitochoncrial-derived activator of caspases/Direct IAP binding with low PI

- Sp1

Specificity protein 1

- SUMO

Small ubiquitin-like modifiers

- TβRI

Transforming growth factor beta type I receptor

- TAB1

TAK1-binding protein 1

- TAK1

Transforming growth factor β-activated protein kinase 1

- TBK1

TANK-biding kinase 1

- TCF/Lef

T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor family

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor beta

- UBA

Ubiquitin-associated domain

- Ubc13

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 13

- Vgl-4

Vestigial-like family member 4

- XAF-1

XIAP-associated factor 1

- XIAP

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein

1. Introduction

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) is a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis protein family (IAP) [1]. XIAP has been described to directly bind to and inhibit caspase activity [2], [3], further regulating the balance between survival and apoptotic cell death. The physiological role of XIAP in the control of apoptosis mainly relies on the interaction between its BIR (baculoviral IAP repeats) domains and apoptotic players [4]. Additionally, XIAP crosstalks with the ubiquitination machinery and regulates the stability of other proteins and of XIAP itself through its UBA (ubiquitin-associated) and RING domains [1], [5]. Although ubiquitously expressed in normal tissues, XIAP is found aberrantly expressed in cancer [6]. Notably, the overexpression of XIAP has been consistently implicated in resistance to therapy-induced apoptosis and poor outcomes in cancer [7]. The information on XIAP overexpression and role in chemoresistance has been extensively exploited as a potential therapeutic strategy, but contrasting data across cancer cohorts and types still limit its clinical utility [8]. Interesting, increasing evidence indicates that assessing not only XIAP total expression but also subcellular localization might provide more comprehensive insights into XIAP functional dynamics. Although XIAP is predominantly expressed at the cytoplasm, emerging evidence suggests that its expression in cell nuclei may contribute to cancer hallmarks [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], and represent a relevant prognostic marker for cancer patient disease outcome [13], [14], [15]. Interestingly, XIAP has also been found in the mitochondrial fraction of some cell types [16], [17], which might reveal additional biological functions for XIAP of possible clinical significance. In this review, we aim to discuss functional and prognostic information concerning XIAP dynamic localization, particularly focusing on cancer. To attain the discussion to XIAP subcellular localization, studies addressing the clinical and biological impact of XIAP based on the assessment of XIAP expression in whole cell extracts have been excluded from this review.

2. Prognostic relevance of subcellular localization of XIAP in cancer

2.1. Localization of XIAP in hematological malignancies

Although the total expression of XIAP has been widely addressed in hematological malignancies, data on the subcellular localization of XIAP is still scarce (Table 1). In B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, the analysis of blood samples from 30 patients revealed XIAP expression predominantly at the cytoplasm [18]. Nevertheless, cytoplasmic expression of XIAP has not been correlated to prognostic factors, such as age, gender, white blood cell count or treatment. Similarly, XIAP expression has failed to predict fludarabine sensitivity [18]. In primary cells derived from multiple myeloma patients, XIAP expression has been found variable and no correlation could be established with disease status [19]. Interestingly, the analysis of XIAP subcellular localization in a multiple myeloma-derived cell line revealed an interaction with its antagonist XIAP-associated factor 1 (XAF1) at the cytoplasm [19].

Table 1.

- XIAP subcellular localization in samples from cancer patients.

| Human cancer | Cohort of patients | Technique | % XIAP positivity | Subcellular localization | Association with clinical-biological parameteres | Prognosis | XIAP antibody | Cohort origin | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 30 | IC | N/A | Cytoplasmic | Prognosis and resistance to fludarabine were not correlated with XIAP cytoplasmic expression | No association | R&D systems | Brazil | [18] | |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 69 | IHC | 32.4% | Nuclear | There was no correlation between p53, Bcl-2, Ki-67, and XIAP expression with progression, free survival and overall survival | No association | X4503, Sigma-Aldrich | Brazil | [20] | |

| Hogkin and Non-Hodgkin lymphomas | 40/240 | IHC | 58% / 15% | Cytoplasmic | XIAP levels have been correlated with expression of cIAP1 and cIAP2 family members | N/A | Clone 48, BD Biosciences | United States | [21] | |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 229 | IHC | 55.0% | N/A | XIAP expression conferred poor clinical outcome | Poor | Clone 48, BD Biosciences | Saudi Arabia | [22] | |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 78 | IHC | 55.1% | Cytoplasmic | XIAP positivity found as an unfavorable factor for therapy response and shorter survival | Poor | ab2541, Abcam | Serbia | [23] | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 12 | IHC | 100% | Cytoplasmic | High XIAP levels in B-cell lines and biopsies derived from Hodgkin lymphoma | N/A | N/A | Denmark | [24] | |

| Cervical carcinoma | 77 | IHC | 94% | Cytoplasmic | Expression of XIAP was not correlated with tumor apoptosis, proliferation, disease stage and patient survival | No association | ApoptoGen Inc. | Hong Kong | [25] | |

| Human ovarian epithelial cancer | 3 | IHC | N/A | Cytoplasmic | XIAP was expressed in highly proliferative cells and human ovarian epithelial carcinomas | N/A | Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc | Canada | [26] | |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | 109 | IHC | 70.64% | Cytoplasmic | XIAP expression was negatively correlated with pathological tumor-node metastasis staging, tumor differentiation and decreased patient survival | Poor | US company Upstate | China | [27] | |

| Colorectal cancer | 96 | IHC | N/A | Cytoplasmic | Higher level of XIAP expression was correlated with tumor differentiation,venous invasion, Duke's staging and lower disease-free and overall survival | Poor | R&D System | China | [28] | |

| Rectal cancer | 58 | IHC | 40.0% | Cytoplasmic | High expression of XIAP and Survivin were associated with advanced stage and poor prognosis |

Poor | R&D | China | [29] | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 50 | IHC | 68% | Cytoplasmic | High expression of XIAP was correlated with unfavorable clinicopathological parameters and poor survival | Poor | Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc | China | [30] | |

| Medullary thyroid carcinoma | 74 | IHC | 37% | Cytoplasmic | XIAP was an independent prognostic biomarker, with a strong negative correlation with patient overall survival, advanced tumor stage and metastatis |

Poor | Clone 48,BD Biosciences | Germany | [31] | |

| Malignant mesothelioma | 112 | IHC | 63% | Cytoplasmic | Higher XIAP and Ki-67 expression was associated with poor overall survival. XIAP is upregulated in mesothelioma effusions and peritoneal mesotheliomas | Poor | Clone 48, BD Biosciences, | Norway | [32] | |

| Bladder cancer | 105 | IHC | 66% | Cytoplasmic | The expression levels of XIAP were not correlated with tumor stage or grade and was an independent prognostic marker for recurrence-free survival | Poor | Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc | China | [33] | |

| Sebaceous gland carcinoma | 29 | IHC | 62% | Cytoplasmic | XIAP overexpression was associated with advanced age, large tumor size and reduced disease-free survival | Poor | A-7 clone, Santa Cruz Biotechnology | India | [34] | |

| Clear-cell renal carcinomas |

170 | IHC | 95% | Cytoplasmic | XIAP expression levels increased with tumor undifferentiation, advancing tumor stage, and aggressiveness | Poor | H62120,clone 48,Transduction Laboratories | Germany | [35] | |

| Gastric carcinoma | 1162 | IHC | 20% | Cytoplasmic | XIAP expression was related to the advanced stage and poor survival and negatively correlated with XAF1 and Smac/DIABLO expression | Poor | BD Bioscience | Korea | [36] | |

| Gastric adenocarcinoma | 201 | IHC | N/A | Cytoplasmic | High XIAP expression was an independent negative prognostic marker for diffuse and mixed type gastric carcinomas | Poor | Clone 48,BD Biosciences | Germany | [37] | |

| Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | 60 | IHC | N/A | Cytoplasmic | Co-expression of XIAP and cIAP1 conferred a worse prognosis than their respective expression |

Poor | BD Biosciences | China | [38] | |

| Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | 60 | IHC | 20.83% | Cytoplasmic | XIAP expression was a primary cause of treatment failure and chemotherapy-induced XIAP expression led to a poor patient outcome | Poor | BD Biosciences | China | [39] | |

| Prostate cancer | 84 | IHC | 35.71% | Cytoplasmic | Negative tumor expression of XIAP, procaspase-3 or cleaved caspase-3 had a significantly worse prognosis and helped identify risk of progression | Favorable | Santa Cruz, CA | Spain | [40] | |

| Prostate cancer | 192 | IHC | N/A | Cytoplasmic | XIAP is expressed at higher levels in prostate cancers and is strongly associated with reduced risk of tumor recurrence | Favorable | R&D Systems, Inc/ Immunogen/ aa 244–263 | United States | [41] | |

| Non-small-cell lung cancer | 144 | IHC | 20% | Cytoplasmic | XIAP expression had an inverse correlation with proliferation markers and was a novel independent prognostic factor for better outcome of resected patients | Favorable | MIHA/ILP-a/ Clone 2F1,MBL |

Netherlands | [42] | |

| Hepatocelullar carcinoma | 150 | IHC | 25.3% | Cytoplasmic | XIAP expression was inversely correlated with LC3 protein and associated with a smaller tumor size, early stage and better patient survival | Favorable | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | China | [43] | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 192 | IHC | 89.6% | Cytoplasmic | XIAP-positive tumors had increased risk of recurrence and reduced disease-free survival and was an independent prognostic factor | Poor | R&D system | China | [44] | |

| Hepatocelullar carcinoma | 80 | IHC | 82.5% | Cytoplasmic | Patients with XIAP-positive/XAF1-negative expression correlated with worse overall and disease-free survival | Poor | Clone 48,BD Biosciences | Italy | [45] | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 70 | IHC | 81.4% | Cytoplasmic | Expression of XIAP and p53 were associated with occurrence, development, metastasis and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma | Poor | ab21278, Abcam | China | [46] | |

| Pancreatic carcinoma | 54 | IHC | N/A | Cytoplasmic | XIAP expression was associated with shorter patient survival and tumor invasion status in aggressive tumors | Poor | BD Biosciences | China | [47] | |

| Oral cell squamous carcinomas | 193 | IHC | 30% (floor of the mouth)/ 13.2% (tongue)/12.5% (other) | Cytoplasmic | XIAP showed higher expression in the floor of the mouth and was associated with decreased overall survival | Poor | Clone 48, BD Biosciences | Germany | [48] | |

| Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | 78 | IHC | N/A | Cytoplasmic | High levels of XIAP correlated with progression | Poor | Cell Signaling Technology | China | [49] | |

| Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and esophageal adenocarcinoma | 114 / 80 | IHC | N/A | Cytoplasmic | High XIAP expression strongly correlated with female gender and advanced tumor stages | Poor | Clone 48, BD Biosciences | Germany | [50] | |

| Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | 110 | IHC | 77.5% | Cytoplasmic | No significant correlation between XIAP expression and clinicopathologic characteristics | No association | R&D systems | China | [51] | |

| Oral cell squamous carcinoma | 54 | IHC | 24.0% | Cytoplasmic | No correlation between expression of cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP and age, gender, primary tumor site, clinical stage or differentiation | No association | Santa Cruz | Japan | [52] | |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | 43 | IHC | 69.8% | Cytoplasmic | Higher levels of XIAP were associated with reduced survival, but results did not reach statistical significance |

No association | Abcam Ltd | Germany | [53] | |

| Breast invasive ductal carcinoma | 102 | IHC | 85.7%(C) / 42.9%(N) | Cytoplasmic and Nuclear | Nuclear XIAP, age, tumor size and lymph node status had prognostic significance | Poor | Abzoom | China | [14] | |

| Breast invasive ductal carcinoma | 138 | IHC | 65.9% (C)/22.5% (N) | Cytoplasmic and Nuclear | Nuclear expression of XIAP was an independent predictor of poor prognosis and identified a subset of hormone-receptor negative patients with shorther survival | Poor | AF8221, R&D systems | Brazil | [13] | |

| Breast cancer | 100 | IHC | 91.5% (C)/74,6% (N) | Cytoplasmic and Nuclear | High expression of cytoplasmic XIAP correlated with HER-2 expression and considered a prognostic biomarker for basal-like breast cancer patients | Poor | N/A | China | [54] | |

| Breast cancer (Triple negative phenotype) | 42 | IHC | 80.95% | Cytoplasmic | Expression of XIAP was correlated with aggressive tumor phenotype, decreased overall and disease free survival |

Poor | Abcam Biotechnology Corporation | China | [55] | |

C: Cytoplasmic; cIAP1/2: Cellular inhibitor of apoptosis 1/2; hIAP: IHC: immunohistochemistry; IC: immunocitochemistry; N: Nuclear; N/A: Not analyzed; XIAP: X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein.

In diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), the most frequent non-Hodgkin lymphoma type, an immunohistochemical analysis revealed that XIAP expression was found at the nucleus of 23 out of 71 samples from adult patients [20]. Nevertheless, progression-free and overall survival have not been affected by nuclear expression of XIAP [20]. This study contrasts data from Akyurek and colleagues [21], who have detected XIAP expression at the cytoplasm of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (15% positivity), precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma (57%), mantle cell lymphoma; (43%) and DLBCL (23%). This study has also reported XIAP cytoplasmic expression in Hodgkin lymphoma patient samples [21]. Although the information on XIAP subcellular localization has been omitted, an additional immunohistochemical work has found XIAP to be overexpressed in 55% of DLBCL patients and to be significantly associated with shorter survival curves [22]. This finding has been confirmed by Markovic and colleagues [23], who found XIAP cytoplasmic expression in significant correlation with ‘bulky’ disease, age, decreased serum albumins, survivin expression, shorter survival and lower therapy response rates. Consistently, XIAP has been found expressed at significantly higher levels in intracytoplasmatic B cell lines derived from Hodgkin lymphoma, compared with the control B cell line L1309 [24]. In cases of biopsies from patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, XIAP high or moderate expression was similarly stained at the cytoplasm. This might imply that XIAP overexpression is a common feature of lymphomas, despite its differential subcellular localization pattern across distinct histologic subtypes.

2.2. Localization of XIAP in solid tumors

Although the pattern of subcellular localization of XIAP has been little explored in hematological malignancies (except for lymphomas), there are more studies addressing this issue in solid tumors (Table 1). By immunohistochemistry, high expression of cytoplasmic XIAP has been found in cervical carcinoma, but failed to associate with prognostic parameters and patient survival [25]. The cytoplasmic staining of XIAP has also been observed in ovarian cancer, but the correlation with prognosis was not evaluated [26]. This study has demonstrated that XIAP confers cisplatin resistance whilst XIAP downregulation promotes drug-induced apoptosis, pointing to a role of cytoplasmic XIAP in chemoresistance. Consistently, XIAP expression has been detected at the cytoplasm of patient samples derived from nasopharyngeal carcinoma [27], colorectal cancer [28], [29], cholangiocarcinoma [30], medullary thyroid carcinoma [31], malignant mesothelioma [32], bladder cancer [33], sebaceous gland [34], clear cell renal [35] gastric [36], [37] and head and neck squamous cell cancer [38], [39]. All these studies have associated increased expression of cytoplasmic XIAP with poor clinical patient outcome, further indicating the biological relevance of XIAP and possible molecular interactions occurring at this subcellular compartment. Contrastingly, the expression of cytoplasmic XIAP has been related to favorable prognosis in some cancer types. In prostate cancer, negative expression of XIAP has conferred worse prognosis [40] and higher levels of the protein has been correlated with reduced risk of tumor recurrence [41]. The expression of cytoplasmic XIAP has also been found to confer favorable outcomes in non-small cell lung cancer [42] and hepatocellular carcinoma [43]. This data contrasts other studies in hepatocellular carcinoma which found the expression of cytoplasmic XIAP as an indicator of poor prognosis [44], [45], [46]. Data on the prognostic relevance of XIAP subcellular localization remains controversial in further tumor types. The cytoplasmic expression of XIAP has been reported to confer poor prognosis in pancreatic carcinoma [47], oral cell squamous carcinoma [48] and both esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma [49], [50]. Nevertheless, previous data on these tumors had failed to demonstrate a statistically significant correlation between cytoplasmic XIAP and clinicopathologic characteristics [51], [52], [53]. In these cases, more studies are necessary to support the connection between XIAP subcellular localization and clinical outcomes.

Despite the predominant cytoplasmic expression of XIAP across tumors from different origins, some studies have implicated the expression of nuclear XIAP in determining distinct clinical outcomes in cancer. Zhang and colleagues [14] have found 42.9% nuclear and 85.7% cytoplasmic expression of XIAP in breast invasive ductal carcinoma samples. Interestingly, only nuclear XIAP reached prognostic significance and shorter patient survival. Corroborating these findings, a recent study from our group has detected the presence of 65.9% cytoplasmic and 22.5% nuclear XIAP in breast cancer by immunohistochemistry [13]. Nuclear XIAP has been found as an independent predictor of poor prognosis and could identify a subset of patients with shorter survival within the hormone-receptor negative subgroup. Contrasting these data, Xu and colleagues [54] either found 91.5% cytoplasmic and 74,6% nuclear expression of XIAP, but only cytoplasmic XIAP achieved poor prognostic significance. A cytoplasmic pattern of expression has also been reported for triple negative breast cancer [55], closely linked to Ki-67 positivity, shorter overall and disease-free survival curves. Considering the heterogeneity of breast cancer, future studies might provide insights on the impact of XIAP nuclear and cytoplasmic expression on specific molecular subtypes. Altogether, these data indicate that XIAP may exhibit differential subcellular localization patterns and prognostic impact, depending on the type of the cancer.

3. XIAP subcellular shuttling

3.1. Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling: the case for XIAP

In eukaryotic cells, the active transport of macromolecules through the nuclear pore complex (NPC) is essential for the transduction of signals that regulate key cellular processes [56]. This mechanism is bidirectional and selectively regulated by binding of specific ligands to transport receptors, enabling the active shuttle of larger molecules across the nuclear membrane [57], [58]. The nuclear import involves recognition of short sequences of basic amino acids in the structure of cargo proteins, termed nuclear localization signals (NLS). NLS-containing proteins interact with import receptors in the cytoplasm, the karyopherins, which then act in concert with RanGTPases to coordinate their active transport into the nucleus [59]. During the nuclear export process, the export receptor Crm1 binds directly to the leucine-rich sequence of cargo proteins, known as nuclear export signal (NES), forming a complex dependent on the RanGTP/GDP axis [58]. The tight regulation of subcellular localization has been proposed essential for the control of molecules involved in key biological processes, including apoptosis regulators [60]. In the case of XIAP, we lack reports on the mechanisms of cytoplasmic-nuclear translocation. Interestingly, we have failed to find a NLS, either classical or non-classical, within XIAP protein sequence [61]; http://mleg.cse.sc.edu/seqNLS. Therefore, the nucleocytoplasmic transport of XIAP through the NPC is likely to involve structural changes which might favor the direct interaction with NLS-containing cargo proteins

3.2. Post-translational modifications in the regulation of XIAP subcellular localization

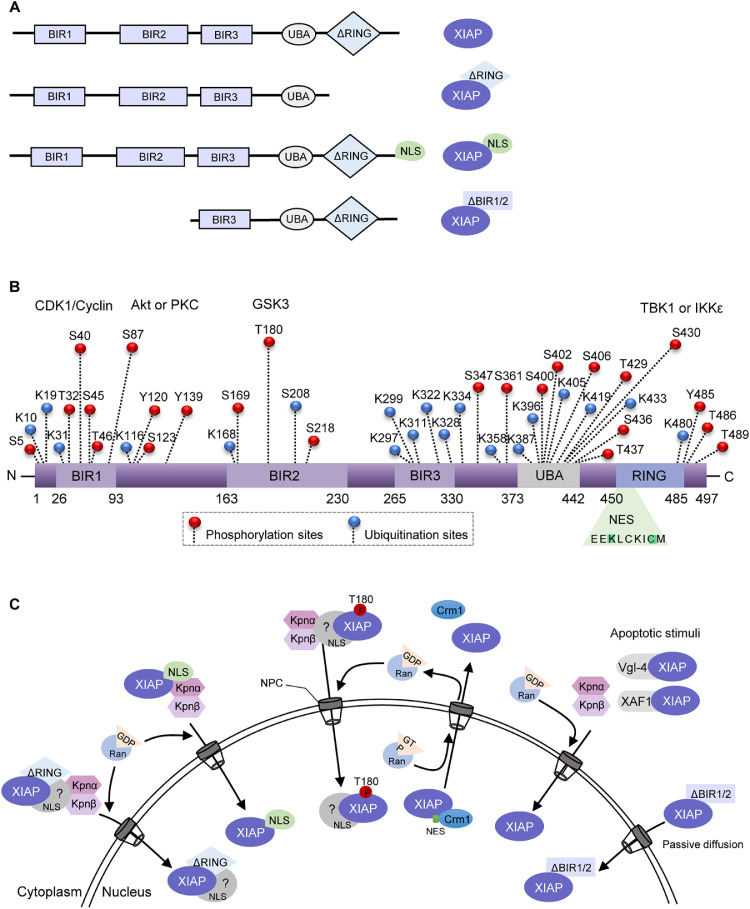

Another issue worth raising on the regulation of XIAP nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling is the role of post-translational modifications (PTMs), known as crucial for regulating protein lifespan, conformation, binding capacity, solubility, localization and function [62]. Some reports have associated PTMs of XIAP with regulation of its stability, subcellular location and function in different cellular models (Fig. 1). In fact, XIAP presents multiple ubiquitination and phosphorylation sites on its structure, and has its function regulated by different kinases [11], [63], [64], [65]. A study published by Lotocki and colleagues [66] was the first to suggest that XIAP monoubiquitination could be involved in the regulation of XIAP perinuclear distribution in neurons following traumatic brain injury-induced cell death. Although not yet demonstrated in tumor models, XIAP monoubiquitination has been already described as an important mechanism for regulating XIAP levels and its ability to counteract apoptosis [67], [68], [69]. Besides, phosphorylation of XIAP has also been reported as a key regulator of XIAP stability and activity during apoptosis and other signaling pathways [11], [64], [65], [70]. During the process of placental maturation, phosphorylated XIAP has been found in the nucleus of trophoblast cells, suggesting a role for XIAP in the regulation of cell survival during pregnancy [70]. Also, XIAP phosphorylation at S87 by Akt and PKC has been described to stabilize XIAP and prevent it from ubiquitin-mediated proteasome degradation, further suppressing apoptosis under stress conditions in neuroblastoma, pancreatic, hepatocellular and colorectal carcinoma [64], [71], [72], [73]. In contrast, phosphorylation at S430 by TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) or the IκB kinase (IKKε) promotes XIAP autoubiquitination and proteasomal degradation after viral infection [74]. Also, XIAP is phosphorylated at S40 by CDK1–cyclin-B1 during mitosis, which inhibits its antiapoptotic function and sensitizes mitotic cervical cancer and osteosarcoma cells to apoptotic signals [65]. Although these reports have not discussed the impact of XIAP phosphorylation on regulation of its subcellular localization, XIAP stability induced by phosphorylation at specific sites could possibly favor XIAP exclusion from the cytoplasm and contribute to enhance XIAP-associated nuclear signaling. In respect to this, some studies have implicated XIAP in modulating the Wnt signaling in models of human embryonic kidney 293 cells, Xenopus embryos and colorectal cancer cells [11], [75]. It has been observed that phosphorylation of XIAP at T180 by GSK3 induced its nuclear localization and improved canonical Wnt signaling through the monobiquitination and direct interaction with Gro/TLE proteins [11] (Table 2, Fig. 1). These findings could reinforce the hypothesis that phosphorylation at sites located within the BIR domain favors XIAP nuclear shuttling and stabilizes its function. Since the C-terminal end of XIAP is involved in autoregulation, its suggestive that phosphorylation in this region could modulate XIAP ubiquitination and thus, proteasomal degradation signaling. On the other hand, the phosphorylation in BIR sites may induce a structural rearrangement in XIAP protein that could increase its stability and interaction with cytoplasmic and nuclear signaling molecules. In fact, mutations in the BIR region have been already described to alter interactions between conserved amino acids within the core of the protein, affecting its activity and stability [76], [77]. Considering that BIR2 and BIR3 domains are important for XIAP interaction with antagonists, Omi/HtrA2 and Smac/DIABLO, phosphorylation at sites within these domains could disturb these interactions and thus, increase XIAP activity. These data point to an interplay between phosphorylation and ubiquitination in regulating XIAP expression, subcellular localization and function in a domain-specific manner, further contributing to determine cell fate decisions.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the XIAP structure and dynamic intracellular localization. (A) Structural representation of XIAP variants that have been shown to translocate into the nucleus. XIAP wild type is composed of three baculoviral IAP repeat (BIR) domains, a ubiquitin-binding domain (UBA) and a RING finger domain. XIAPΔRING is a RING domain-deleted form and XIAPNLS is the variant with a nuclear localization signal (NLS) insertion at the carboxi-terminal end. XIAPΔBIR1/2 is a protein fragment shown to be generated following chemotherapeutic treatment. (B) Predicted phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and nuclear export signal (NES) sites on XIAP have been curated by PhosphoSitePlus and NetNES 1.1 online resources tools. XIAP is a substrate for CDK-cyclin B1, Akt, PKC, GSK3, TBK1 and IKKε phosphorylation at different sites and presents an NES located within the RING domain. (C) A model of XIAP nuclear-cytoplasmatic shuttling regulation. XIAPΔRING, XIAPNLS and T108-phosphorylated forms might complex with cargo proteins at the cytoplasm and translocate to the nuclear compartment through the nuclear pore complex (NPC). Under apoptotic stimuli, Vgl-4 and XAF1 can directly bind to and sequester XIAP to the nuclear compartment. Also, the XIAPΔBIR1/2 fragment might transport to the nucleus by passive diffusion. Image abbreviations: P, phosphorylation-modified protein; Akt, Protein kinase B; CDK1, Cyclin-dependent kinase 1; Crm1, Chromosomal maintenance 1; GDP, Guanosine diphosphate, GSK-3, Glycogen synthase kinase 3; GTP, Guanosine triphosphate; IKKε, IκB kinase epsilon; IKKβ: IκB kinase beta; Kpnα, karyopherin-alpha; Kpnβ: karyopherin-alpha; PKC, Protein kinase C; Ran, Ras-related nuclear protein; TBK1, TANK-biding kinase 1; Vgl-4, Vestigial-like family member 4; XAF1, XIAP-associated factor 1.

Table 2.

Molecular mechanisms and biological effects associated with XIAP nuclear expression and translocation from in vitro approaches.

| Cellular model | Mechanism of XIAP nuclear localization | Biological effects and structural domains involved | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCT116 colorectal cancer cell line | Overexpression of a mutant form encoding XIAPΔRING | Anchorage-independent growth and G1/S phase transition, through interaction with E2F1 and increase in cyclin E levels in a BIR domain dependent fashion | [9] |

| U2OS osteosarcoma cell line | Treatment with nuclear export inhibitor leptomycin B | Lys63-linked polyubiquitination of HIF by XIAP/Ubc13 complex, leading the upregulation of HIF-responsive genes during hypoxia | [10] |

| SW480 and HCT116 colorectal cancer cell lines | XIAP nuclear translocation induced by GSK3 phosphorylation | Phosphorylation at threonine 180 within the BIR2 domain of XIAP activates the Wnt signaling pathway | [11] |

| T24T and UMUC3 bladder cancer cell lines | Overexpression of mutant forms encoding XIAPΔBIR and XIAPΔRING | BIR2 and BIR3-mediated interaction with E2F1 and Sp1 leads to cell invasion via modulation of miR-203, MMP2 and Src | [12] |

| MCF-7 breast cancer cell line | Overexpression of mutant forms encoding nuclear XIAP (NLS C-term and ΔRING) | Improved growth capacity, decreased drug sensitivity and increase in NFkB p50 protein levels of nuclear XIAP-overexpressing cells in a RING-associated manner | [13] |

| Trophoblast cells | Phosphorylated-induced nuclear XIAP during placenta maturation | Decreased trophoblast apoptosis in preeclamptic placenta | [70] |

| Human embryonic kidney 293 cell line | Overexpression of TLE3 increased the nuclear pool of XIAP | Induction of monoubiquitylation of Gro/TLE repressor and activation of Wnt activation associated with XIAP E3 ligase activity | [75] |

| HeLa cervical carcinoma, HEL 299 human fetal lung fibroblast and SF295 patient-derived glioblastoma cell lines | Nuclear co-expression of XIAP and XAF1 | XIAP nuclear capture prevents the formation of XIAP/caspase-3 complex and improves sensitivity to etoposide | [112] |

| Rat brains | Nuclear XAF1 and XIAP co-localization post-ischemic brain injury | Interaction with XAF1 disrupts XIAP/caspases complexes, leading to apoptosis | [113] |

| MCF-7 breast cancer and human embryonic kidney 293 cell lines | Nuclear co-expression of XIAP and Vgl-4 | Bax-induced caspase-mediated pro-apoptotic signaling | [115] |

| DOHH-2 B-cell lymphoma cell line | XIAP cleavage into a BIR3-RING fragment which translocated to the nucleus | XIAP nuclear translocation possibly by passive diffusion associated with chemotherapeutic drug-induced apoptosis | [116] |

4. Mechanistic insights into XIAP dynamics in distinct subcellular compartments

4.1. Molecular interactions and biological functions of cytoplasmic XIAP

XIAP antiapoptotic activity is mostly played at the cytoplasmic compartment, where it interacts with caspases and apoptotic antagonists to counteract apoptosis. Once intrinsic apoptosis is triggered in mammalian cells, XIAP can bind to the activated forms of executioner caspase-3 and 7 through the BIR structural domains [4]. The interaction between XIAP and caspases has been widely associated with cancer drug resistance, due to XIAP-mediated inhibition of caspase-proteolytic activity and drug-induced apoptotic cell death stimuli. Therefore, XIAP-caspase complexes have been considered a target for anticancer intervention aiming to sensitize chemoresistant malignant cells [78]. Of note, several ongoing clinical trials have BIR-targeted IAP inhibitors being currently tested for cancer patients [79].

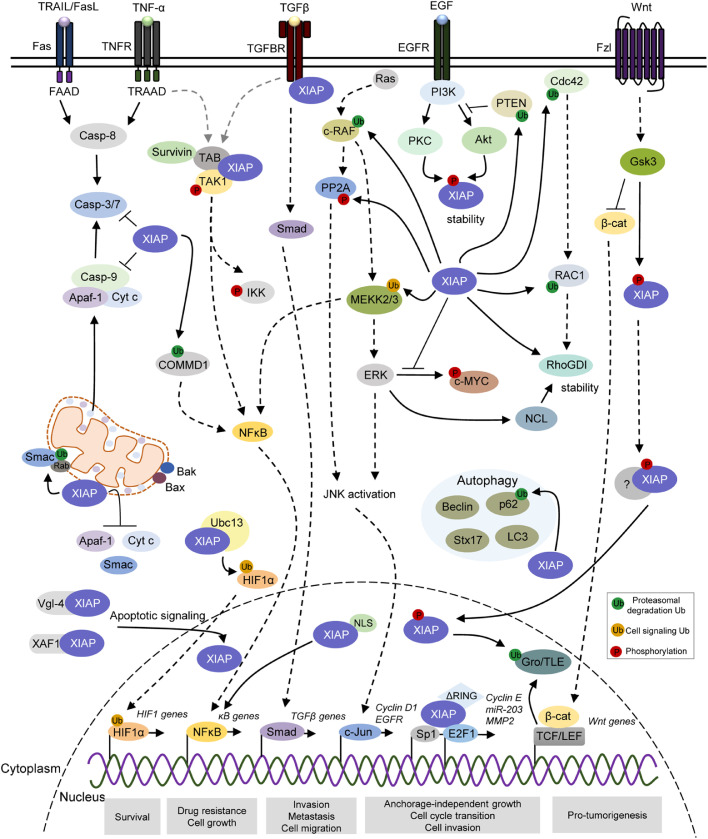

Nevertheless, cytoplasmic XIAP also works as a regulator of oncogenic molecular pathways (Fig. 2). Through the BIR1 domain, XIAP interacts with transforming growth factor (TGF)-β-activated kinase (TAK)1-binding protein (TAB)1 to form the BIR1/TAB1 complex, which further contributes to the phosphorylation of IκB kinase (IKKβ), leading to release of NFκB into the nucleus and activation of specific gene signatures to modulate tumor progression [80], [81], [82]. Although not described in tumors, XIAP-mediated activation of NFκB also occurs dependently on the UBA domain [83]. Alternatively, XIAP activates NFκB as a downstream molecule of MNK (MAPK Interacting Kinase) signaling, forming a feedback loop that increases XIAP expression in breast cancer [84]. Additionally, mechanistic studies in human embryonic kidney 293 cells have shown that XIAP with loss of E3 ubiquitin ligase activity failed to activate κB-dependent reporter gene activity, indicating that the RING E3 ubiquitin ligase activity is required for the activation of NFκB [85]. In this same cellular model, it has been demonstrated that XIAP can modulate a second wave of NFkB activation through the direct interaction and ubiquitination of MEKK2 via K48- and K63-conjugated ubiquitin chains [86]. Moreover, XIAP directly conjugates K63-linked ubiquitin chains to MEKK2 and MEKK3 and interferes with ERK5 signaling cascade in cervical carcinoma and human myogenic differentiation [87]. Through an NFκB-dependent signaling via the E3 ligase activity of RING domain, XIAP can also interact with survivin to stimulate tumor cell invasion and metastasis in breast, prostate and colorectal cancer cells [82]. To add complexity to this scenario, the RING domain has been shown to indirectly modulate NFκB activity due to its function in maintaining homeostasis of copper, an essential micronutrient whose disorder is associated with cancer progression (revised in [88]).

Fig. 2.

XIAP differentially regulates apoptotic and pro-oncogenic signaling pathways in distinct subcellular compartments. XIAP is a multi-functional protein involved in multiple cellular signaling pathways associated with cellular processes that favor tumor features, including survival, drug resistance, autophagy, anchorage-independent cell growth, cell proliferation, migration, invasion and metastasis. XIAP blocks the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways through binding to and inhibiting caspases-3/7/9. XIAP also acts on apoptosis signaling by catalyzing ubiquitination of its mitochondrial regulator Smac, as well as limit the release of Cyt C (Cytochrome c), Smac and Apaf-1 during antiapoptotic response. During hypoxia, the XIAP/Ubc13 complex ubiquitinates HIF1, subsequently upregulating the expression of HIF target genes. XIAP binds to TAB1/TAK1 complex and interact with survivin to stimulate NFκB-dependent signaling. Indirectly, XIAP modulates NFκB activity by ubiquitination of COMMD1 and MEKK2/3. XIAP physically interacts with TGF-β type I receptor through Smad-dependent signaling, promoting TGF-β signaling pathway. XIAP has also a role in cell migration via ubiquitination of c-RAF, CDC42 and RAC1, as well as regulation of ERK activity to modulate c-MYC, nucleolin and RhoGDI stability. XIAP also induces PP2A phosphorylation, further contributing to c-Jun/AP-1 activation signaling. XIAP plays a role in the autophagy, in which it interacts and suppresses SQSTM1 (p62) by ubiquitination-dependent proteasomal degradation. Also, XIAP indirectly modulates the levels of LC3-II, Beclin 1 and Syntax 17 during the autophagic flux. XIAP can ubiquitinate PTEN, promoting Akt activation, which in turn leads to XIAP stability. XIAP is phosphorylated by GSK3 and, thus, recruited to TCF/Lef transcriptional complexes where it promotes monoubiquitination of co-repressor Groucho/TLE, further leading to the transcription of Wnt-regulated genes. Also, intranuclear XIAP binds to transcriptional factor Sp1 and E2F1, increasing Cyclin E, miR-203 and MMP2. The black and dotted arrows represent direct and indirect interactions, respectively. P, phosphorylation-modified protein; Ub, ubiquitin-modified protein. Akt, Protein kinase B; Apaf-1, Apoptotic protease activating factor 1; Cdc42, Cell division control protein 42 homologue; CDK1, Cyclin-dependent kinase 1; c-Jun/AP-1: Jun proto-oncogene/Activator protein 1; c-Myc: Cellular Myc; COMMD1, copper metabolism MURR1 domain-containing; c-Raf: Raf proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase; Crm1, Chromosomal maintenance 1; Cyt C, Cytochrome c; E2F1, E2F transcription factor 1; EGFR: Epidermal growth factor receptor; ERK, Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GDP, Guanosine diphosphate, GSK-3, Glycogen synthase kinase 3; GTP, Guanosine triphosphate; HIF1; Hypoxia-inducible factor 1; IKKε, IκB kinase epsilon; IKKβ: IκB kinase beta; Kpnα, karyopherin-alpha; Kpnβ: karyopherin-alpha; LC3-II: Microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3; p62/SQSTM1: Sequestosome 1; PKC, Protein kinase C; PP2A, Protein phosphatase 2; LC3-II: Microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3; MEKK, Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase; MMP2, Matrix metalloproteinase-2; NFκB, Nuclear factor kappa B; PI3K, Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; Rac1, Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1; Ran, Ras-related nuclear protein; RhoGDI: Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor; Smac, Second mitochoncrial-derived activator of caspases; Sp1: Specificity protein 1; TAB1/TAK:TAK1-binding protein 1/Transforming growth factor β-activated protein kinase 1; TBK1, TANK-biding kinase 1; TCF/Lef, T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor family; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor beta; Vgl-4, Vestigial-like family member 4; XAF1, XIAP-associated factor 1.

Besides NFκB activation, XIAP has also been reported to regulate other signaling pathways associated with tumor features, such as anchorage-independent cell growth, proliferation, migration, invasion and metastasis. For instance, XIAP strongly binds to and ubiquitinates c-RAF, promoting its degradation via the Hsp90-mediated quality control system, thereby modulating the MAPK signaling pathway and cell migration in cervical carcinoma cells [89]. Also, XIAP can work as a cofactor for transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) in the regulation of gene expression through Smad-dependent signaling in metastatic breast cancer cells [90]. Interestingly, XIAP has been found to physically interact with TGF-β type I receptor (TβRI), mediating the downstream signaling of both TGF-β- and κB-responsive promoters in an E3 ligase activity-dependent manner, promoting tumor invasion [90]. Additionally, XIAP accelerates cell migration by inducing epithelial–mesenchymal transition via TGF-β signaling in esophageal carcinoma cells [91].

During the control of cell plasticity, XIAP directly conjugates polyubiquitin to the Lys147 of Rho GTPase Rac1 and thereby directs Rac1 for proteasomal degradation in both in vitro and in vivo models [92]. In addition, XIAP binds to the Rho GTPase Cdc42 and contributes to its degradation, thus controlling actin cytoskeleton dynamics, polarity and tumor metastasis [93]. Interestingly, XIAP interacts with RhoGDI through its RING domain and negatively modulates its SUMOylation at Lys-138 by a mechanism independent of its E3 ligase activity, further facilitating actin expression and polymerization as well as colorectal cancer cell motility [94], [95]. Moreover, mechanistic studies have shown that the overexpression of XIAP induces bladder cancer invasion in vitro and lung metastasis in vivo through Erk, which in turn regulates nucleolin mRNA stability and increases RhoGDIβ mRNA stability and expression [96]. Also, the RING-associated E3 ligase activity of XIAP has also been described to regulate anchorage-independent growth, transcription of cyclin D1 and cell cycle transition in colorectal cancer cells, through induction of PP2A phosphorylation at Tyr-307 and transactivation of c-Jun/AP-1 [97]. On the other hand, RING deletion promotes EGFR expression through Rac1 inhibition and down-regulation of PP2A/MAPKK/MAPK/c-Jun axis, further resulting in microRNA-200a suppression and anchorage-independent growth in bladder cancer cells [98]. Recently, it has been observed that the RING domain of XIAP is able to stabilize c-Myc by inhibiting ERK-mediated phosphorylation at Thr-58, thus inducing anchorage-independent growth and tumor cell invasion [99]. By catalyzing the direct ubiquitination of PTEN, XIAP has been shown to modulate PTEN levels in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that XIAP can promote activity of its downstream negative target Akt via its E3 ligase activity [100].

XIAP has also been reported as an autophagy modulator in different cellular contexts. In wild-type p53 colorectal cancer cells, XIAP could inhibit autophagy via a XIAP-Mdm2-p53 signaling axis, contributing to tumorigenesis [101]. Another study has demonstrated that XIAP directly interacts with p62 (SQSTM1/sequestosome 1) and suppresses its expression via ubiquitination-dependent proteasomal degradation, pointing to role of the E3 ligase activity of XIAP in p62 stability during cell cancer proliferation [102]. In contrast, cervical carcinoma cells overexpressing a gene encoding mutant XIAP with impaired E3 ubiquitin ligase activity (XIAPH467A) exhibit reduced levels of the microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3-II), compared to wild-type XIAP [103]. These variants have been similarly used to demonstrate that the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of XIAP stimulates proteasomal degradation of IκB, leading to the nuclear translocation of the NFκB p65 subunit, which binds to and transcriptionally activates the promoter of Beclin 1, crucial for autophagosome biogenesis during early stages of canonical autophagy [103]. In addition, the RING domain of XIAP is required to physically interact with Syntaxin 17 during late stages of autophagic flux, further regulating the autophagosome-lysosome fusion [104]. Thus, despite the controversial role of XIAP during the autophagic process, the interplay between XIAP and autophagy might be relevant in cancer, particularly for survival mechanisms [105], [106], [107], [108]. Taken together, these observations suggest that cytoplasmic XIAP might act to regulate a wide range of signaling pathways and biological processes, independently of its apoptosis inhibition function.

4.2. Molecular interactions and biological functions of mitochondrial XIAP

Apart from cytoplasm, XIAP expression has been detected in other subcellular compartments and shown to contribute to cancer aggressive features, including cell proliferation, cell migration, autophagy, invasion, metastasis and differentiation [9,13,87,91,[97], [98], [99]]. This diversity of XIAP functions could rely, at least in part, on the different structural domains and distinct subcellular locations within cancer cells. In the last years, it has been demonstrated that XIAP can localize to and deregulate mitochondria during modulation of the antiapoptotic cascade in cancer (revised in [16], [17]). In breast cancer models, XIAP can enter mitochondria by activating Bax/Bak-mediated mitochondrial permeabilization, which results in degradation of its inhibitor Smac/DIABLO, through endolysosomal and proteasomal signaling (Fig. 2) [109], [110]. In an E3 ligase-dependent manner, XIAP interacts with Rab membrane targeting components at the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), generating Rab5- and Rab7-positive endolysosomes in the mitochondria and leading to Smac degradation [110]. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that overexpression of XIAP in renal cell carcinoma can limit the release of cytochrome c, Smac and Apaf-1 from the mitochondria during etoposide-induced apoptosis, reinforcing its role in mitochondria homeostasis during the antiapoptotic response [17]. It remains to be explored the molecular mechanisms of XIAP translocation into the mitochondria aiming to design potential intervention strategies.

4.3. Molecular interactions and biological functions of nuclear XIAP

To date, a few reports have experimentally demonstrated the mechanisms of XIAP translocation to the nuclear compartment, as well as its functions. Studies conducted in models of induced brain ischemia and chemotherapy treatment have implicated some molecules in XIAP nuclear retention (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Upon ischemic brain injury, XIAP-associated factor 1 (XAF1) has been demonstrated to directly interact with and transport XIAP to the nucleus [111], [112], [113]. Another study has shown that XAF1 can bind to the RING domain of XIAP protein, but no association with XIAP nuclear translocation has been established [114]. In addition, a transcriptional cofactor of skeletal muscle Vgl-4 protein has been described as a XIAP carrier, triggering its distribution to the nucleus in transiently transfected breast cancer cells [115]. These studies have all associated XIAP capture in the nuclear compartment to the abrogation of its caspase-inhibitory cytoplasmic function and therefore, improved apoptosis sensitivity. Although these studies have not provided the molecular basis of the mechanisms, others have approached XIAP role in cancer treatment response using models of drug-induced or forced entry of sequence-modified XIAP mutants into the nucleus. Nowak and colleagues [116] have demonstrated that XIAP is cleaved in lymphoma cells exposed to chemotherapeutic agents in vitro, generating a ∼30 kDA BIR3-RING fragment, which then translocates from the cytosol to the nucleus. In this setting, XIAP cleavage could possibly facilitate its passage through the NPC by passive diffusion, a feature of proteins smaller than 40 kDa.

In contrast, evidence from the last 10 years has emerged on role of XIAP in regulating apoptosis-independent nuclear signal transduction, particularly of transcription factors known to contribute to cancer hallmarks, including E2F1, NFκB, HIF1 and Wnt/ β-catenin cascades (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Cao et al [9]. have found that colorectal carcinoma cellular models overexpressing XIAPΔRING exhibit nuclear XIAP, which then interacts with E2F1 to increase cyclin E levels and promote anchorage-independent growth and G1/S phase transition. Accordingly, we have also confirmed nuclear expression of XIAP in XIAPΔRING-overexpressing breast cancer cells [13]. Using cells overexpressing a mutant form of XIAP containing an insertion of an NLS (XIAPNLS C-term), our group have recently demonstrated that intranuclear XIAP associates with increased NFκB transcriptional activity, drug resistance and cell growth in breast cancer [13]. Since cells overexpressing XIAP with disrupted E3 ligase activity (XIAPΔRING e XIAPH467A) have failed to induce NFκB activity and promote similar aggressive features, these effects were attributed, at least in part, to the RING domain [13]. Although the molecular mechanism underlying XIAPΔRING localization at the nucleus has not been determined to date, the nuclear accumulation of XIAP has been reported in osteosarcoma cells treated with leptomycin B, an irreversible inhibitor of all NES/Crm1 interaction and thus, nuclear export in osteosarcoma cells [10]. Corroborating this idea, two canonical NES located in hydrophobic residues into the RING domain sequence have previously predicted by an in silico approach [13]. These findings might point to a potential role of the RING domain for the nuclear exclusion of XIAP via classical nuclear export mechanisms and could partially explain XIAP nuclear retention in XIAPΔRING-overexpressing cells. Once XIAPΔRING mutant encodes a protein larger than 40 kDa, unlikely to passively go through the NPC, we might hypothesize that this mutant undergoes a conformational change that favors its interaction with cytoplasmic molecules involved in XIAP translocation.

Not only RING mediates nuclear XIAP-induced effects but also BIR2 and BIR3 domains, through which XIAP binds to E2F1 and Sp1 and increases miR-203 transcription, MMP2 activation and bladder cancer cell invasion by inhibiting Src [12]. In osteosarcoma cells, XIAP has been shown to upregulate the expression of HIF target genes during hypoxia, by targeting HIF1 for Lys63-linked polyubiquitination, dependently on the activity of E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme Ubc13 [10]. Last but not least, evidence suggests that XIAP crosstalks with the nuclear signaling downstream Wnt activation during tumorigenesis and development [11], [75]. XIAP is phosphorylated by GSK3 and, thus, recruited to TCF/Lef transcriptional complexes where it promotes monoubiquitination of co-repressor Groucho/TLE family proteins in colorectal cancer cells, releasing the promoter for the assembly of the β-catenin-TCF/Lef transcription complex and leading to the transcription of Wnt pathway-regulated genes [11], [75]. Altogether, these studies point to a non-canonical function for XIAP in the nucleus, closely linked to the modulation of multiple oncogenic pathways.

5. Conclusions and perspectives

The overexpression of XIAP is a hallmark of a great variety of tumor types [7]. However, data on the significance and prognostic value of XIAP have shown inconsistences, which limit its validation as a cancer biomarker of clinical utility. One of the possible reasons for the observed inconsistencies in the literature could be the wide range of antibody clones, with different brands and specificities, used indistinctly across sets of cancer patient cohorts. Moreover, some of these studies have been conducted with a small number of patients, which impacts statistical data analysis and confidence and further prompts validation in larger and multicenter cancer cohorts. Another possible reason for opposing conclusions is that XIAP-encoding gene undergoes alternative splicing and thus, XIAP presents some splicing variants, that might differ in their subcellular localization. It remains to be determined whether anti-XIAP antibodies currently used can recognize all XIAP splicing isoforms. Also, it would be worth it addressing the expression profile, subcellular localization and functional relevance of XIAP splicing variants to clarify their biological roles in specific cellular contexts and in cancer tissues from different origins.

Regardless of potential pitfalls in assessing XIAP expression, strong evidence indicates that XIAP protein can be found in different subcellular compartments, cytoplasm, mitochondria and nucleus, further regulating diverse signaling pathways sustaining cancer hallmarks. How XIAP is recruited to the mitochondrial and nuclear compartment to act differently from its canonical antiapoptotic function is not fully understood. We urge to identify the particular mechanisms involved in XIAP subcellular shutting, as well as elucidate the role of post-translational modifications on the stability, activity and subcellular localization of XIAP. The knowledge on the mechanisms of translocation of XIAP from the cytoplasm to the nucleus might give insights on how we could interfere with XIAP shuttling to prevent oncogenic functions played in specific compartments. Interestingly, other IAP members have been shown to shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm and exert differential functions in tumor models, depending on the subcellular compartment. Similarly, Survivin [117], [118], [119], Livin [120], and cIAP1 and cIAP2 [6], [121], [122] have also been found expressed at the nucleus and cytoplasm, with distinct functional, mechanistic and prognostic impact in cancer. Although the particularities of each IAP member go beyond the scope of this review, interfering with IAP subcellular localization might be a potential strategy to modulate cancer aggressive features. Indeed, the nuclear transport machinery has been emerging as a potential therapeutic target, particularly considering that the nuclear-cytoplasmic transport is deregulated in different types of cancers [123]. Not only it is important to understand the mechanisms underlying XIAP subcellular shuttling but also XIAP-mediated oncogenic effects in each subcellular compartment. These studies might contribute to better understanding mechanisms associated with tumorigenesis and provide the rationale for directed therapy. Although many clinical trials are ongoing with small-molecule IAP inhibitors, antisense oligonucleotides, and mimetics of IAP antagonists, most of these strategies target the BIR domains of XIAP [79]. Considering that the BIR domains mainly mediate interactions of XIAP with apoptosis mediators located at the cytoplasm, we herein propose that targeting the RING domain might be a promising strategy to counteract RING-dependent functions exerted by XIAP at both the cytoplasm, the nucleus and potentially, the mitochondria.

Last, we should mention that the findings concerning the mechanistic and functional impact of XIAP differential subcellular localization in cancer raise the concern with studies carrying out q-PCR and Western blotting using whole cell lysates and thus, ignoring cytoplasm or nuclei when analyzing their data. Growing evidence points that analysis of XIAP expression at cellular compartments by either subcellular fractioning or immunocyto/histochemistry should be similarly performed when trying to understand its contribution in certain experimental or clinical settings. Labeling XIAP subcellular localization in combination with total expression levels might provide additional functional, predictive and prognostic information of potential biological and clinical significance.

Funding

Work conducted by G.N. is supported by grants from Programa de Oncobiologia (Fundação do Câncer 2019), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (and FAPERJ/JCNE N° 201.274/2021 and FAPERJ/INST-111.298/2016), L'oreál-UNESCO-ABC Para Mulheres na Ciência and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (MCTIC/CNPq N° 28/2018 - 435,783/2018–1). R.C.M. is supported by CNPq Produtividade (304,565/2016–4), FAPERJ/CNE N° 02/2017, Universal MCTIC/CNPQ (N.° 28/2018 - E-26/202.798/2017), Swiss Bridge Foundation and Programa de Oncobiologia (Fundação do Câncer 2019). B.S.M. and C.A.F. are supported by FAPERJ and CNPq fellowships, respectively.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

We apologize to authors whose work has not been cited due to space limitations.

References

- 1.Kocab A.J., Duckett C.S. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins as intracellular signaling intermediates. FEBS J. 2016;283:221–231. doi: 10.1111/febs.13554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamm I., Wang Y., Sausville E., Scudiero D.A., Vigna N., Oltersdorf T., Reed J.C. IAP-family protein survivin inhibits caspase activity and apoptosis induced by Fas (CD95), Bax, caspases, and anticancer drugs. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5315–5320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi R., Deveraux Q., Tamm I., Welsh K., Assa-Munt N., Salvesen G.S., Reed J.C. A single BIR domain of XIAP sufficient for inhibiting caspases. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:7787–7790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scott F.L., Denault J.-.B., Riedl S.J., Shin H., Renatus M., Salvesen G.S. XIAP inhibits caspase-3 and -7 using two binding sites: evolutionarily conserved mechanism of IAPs. EMBO J. 2005;24:645–655. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galbán S., Duckett C.S. XIAP as a ubiquitin ligase in cellular signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:54–60. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vischioni B., van der Valk P., Span S.W., Kruyt F.A.E., Rodriguez J.A., Giaccone G. Expression and localization of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in normal human tissues. Hum. Pathol. 2006;37:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohamed M.S., Bishr M.K., Almutairi F.M., Ali A.G. Inhibitors of apoptosis: clinical implications in cancer. Apoptosis. 2017;22:1487–1509. doi: 10.1007/s10495-017-1429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao X., Zhang L., Wei Y., Yang Y., Li J., Wu H., Yin Y. Prognostic Value of XIAP Level in Patients with Various Cancers: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Cancer. 2019;10:1528–1537. doi: 10.7150/jca.28229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao Z., Li X., Li J., Luo W., Huang C., Chen J. X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) lacking RING domain localizes to the nuclear and promotes cancer cell anchorage-independent growth by targeting the E2F1/Cyclin E axis. Oncotarget. 2014;5:7126–7137. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park C.V., Ivanova I.G., Kenneth N.S. XIAP upregulates expression of HIF target genes by targeting HIF1α for Lys63-linked polyubiquitination. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2017;45:9336–9347. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng V.H., Hang B.I., Sawyer L.M., Neitzel L.R., Crispi E.E., Rose K.L., Popay T.M., Zhong A., Lee L.A., Tansey W.P., Huppert S., Lee E. Phosphorylation of XIAP at threonine 180 controls its activity in Wnt signaling. J. Cell Sci. 2018;131 doi: 10.1242/jcs.210575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu J., Hua X., Yang R., Jin H., Li J., Zhu J., Tian Z., Huang M., Jiang G., Huang H., Huang C. XIAP Interaction with E2F1 and Sp1 via its BIR2 and BIR3 domains specific activated MMP2 to promote bladder cancer invasion. Oncogenesis. 2019;8:71. doi: 10.1038/s41389-019-0181-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delbue D., Mendonça B.S., Robaina M.C., Lemos L.G.T., Lucena P.I., Viola J.P.B., Magalhães L.M., Crocamo S., Oliveira C.A.B., Teixeira F.R., Maia R.C., Nestal de Moraes G. Expression of nuclear XIAP associates with cell growth and drug resistance and confers poor prognosis in breast cancer. Biochim Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2020;1867 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2020.118761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y., Zhu J., Tang Y., Li F., Zhou H., Peng B., Zhou C., Fu R. X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis positive nuclear labeling: a new independent prognostic biomarker of breast invasive ductal carcinoma. Diagn. Pathol. 2011;6:49. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-6-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nestal de Moraes G., Delbue D., Silva K.L., Robaina M.C., Khongkow P., Gomes A.R., Zona S., Crocamo S., Mencalha A.L., Magalhães L.M., Lam E.W.-F., Maia R.C. FOXM1 targets XIAP and Survivin to modulate breast cancer survival and chemoresistance. Cell Signal. 2015;27:2496–2505. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaudhary A.K., Yadav N., Bhat T.A., O'Malley J., Kumar S., Chandra D. A potential role of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein in mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and its implication in cancer therapy. Drug Discov. Today. 2016;21:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen C., Liu T.S., Zhao S.C., Yang W.Z., Chen Z.P., Yan Y. XIAP impairs mitochondrial function during apoptosis by regulating the Bcl-2 family in renal cell carcinoma. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018;15:4587–4593. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.5974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silva K.L., Vasconcellos D.V., de P. Castro E.D., Coelho A.M., Linden R., Maia R.C. Apoptotic effect of fludarabine is independent of expression of IAPs in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Apoptosis. 2006;11:277–285. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-3560-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desplanques G., Giuliani N., Delsignore R., Rizzoli V., Bataille R., Barillé-Nion S. Impact of XIAP protein levels on the survival of myeloma cells. Haematologica. 2009;94:87–93. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faccion R.S., Rezende L.M.M., de O. Romano S., de S. Bigni R., Mendes G.L.Q., Maia R.C. Centroblastic diffuse large B cell lymphoma displays distinct expression pattern and prognostic role of apoptosis resistance related proteins. Cancer Invest. 2012;30:404–414. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2012.672844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akyurek N., Ren Y., Rassidakis G.Z., Schlette E.J., Medeiros L.J. Expression of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in B-cell non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphomas. Cancer. 2006;107:1844–1851. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hussain A.R., Uddin S., Ahmed M., Bu R., Ahmed S.O., Abubaker J., Sultana M., Ajarim D., Al-Dayel F., Bavi P.P., Al-Kuraya K.S. Prognostic significance of XIAP expression in DLBCL and effect of its inhibition on AKT signalling. J. Pathol. 2010;222:180–190. doi: 10.1002/path.2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markovic O., Marisavljevic D., Cemerikic V., Perunicic M., Savic S., Filipovic B., Mihaljevic B. Clinical and prognostic significance of apoptotic profile in patients with newly diagnosed nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) Eur. J. Haematol. 2011;86:246–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kashkar H., Haefs C., Shin H., Hamilton-Dutoit S.J., Salvesen G.S., Kronke M., Jurgensmeier J.M. XIAP-mediated caspase inhibition in Hodgkin's lymphoma-derived B cells. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:341–347. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu S.S., Tsang B.K., Cheung A.N., Xue W.C., Cheng D.K., Ng T.Y., Wong L.C., Ngan H.Y. Anti-apoptotic proteins, apoptotic and proliferative parameters and their prognostic significance in cervical carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer. 2001;37:1104–1110. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J., Feng Q., Kim J.M., Schneiderman D., Liston P., Li M., Vanderhyden B., Faught W., Fung M.F., Senterman M., Korneluk R.G., Tsang B.K. Human ovarian cancer and cisplatin resistance: possible role of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins. Endocrinology. 2001;142:370–380. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.1.7897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren M., Wang Z., Gao G., Gu X., Wu L., Chen L. Impact of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein on survival of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients following radiotherapy. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:11825–11833. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-5029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiang G., Wen X., Wang H., Chen K., Liu H. Expression of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein in human colorectal cancer and its correlation with prognosis. J. Surg. Oncol. 2009;100:708–712. doi: 10.1002/jso.21408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y.-.T., Tsao S.-.C., Tsai H.-.P., Wang J.-.Y., Chai C.-.Y. The X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein is an independent prognostic marker for rectal adenocarcinoma after preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Virchows. Arch. 2016;468:559–567. doi: 10.1007/s00428-016-1913-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou F., Xu J., Ding G., Cao L. Overexpressions of CK2β and XIAP are associated with poor prognosis of patients with cholangiocarcinoma. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2014;20:73–79. doi: 10.1007/s12253-013-9660-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Werner T.A., Tamkan-Ölcek Y., Dizdar L., Riemer J.C., Wolf A., Cupisti K., Verde P.E., Knoefel W.T., Krieg A. Survivin and XIAP: two valuable biomarkers in medullary thyroid carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer. 2016;114:427–434. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleinberg L., Lie A.K., Flørenes V.A., Nesland J.M., Davidson B. Expression of inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein family members in malignant mesothelioma. Hum. Pathol. 2007;38:986–994. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen X., Wang T., Yang D., Wang J., Li X., He Z., Chen F., Che X., Song X. Expression of the IAP protein family acts cooperatively to predict prognosis in human bladder cancer patients. Oncol. Lett. 2013;5:1278–1284. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jayaraj P., Sen S., Dhanaraj P.S., Jhajhria R., Singh S., Singh V.K. Immunohistochemical expression of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis in eyelid sebaceous gland carcinoma predicts a worse prognosis. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2017;65:1109–1113. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_399_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramp U., Krieg T., Caliskan E., Mahotka C., Ebert T., Willers R., Gabbert H.E., Gerharz C.D. XIAP expression is an independent prognostic marker in clear-cell renal carcinomas. Hum. Pathol. 2004;35:1022–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim M.A., Lee H.E., Lee H.S., Yang H.-.K., Kim W.H. Expression of apoptosis-related proteins and its clinical implication in surgically resected gastric carcinoma. Virchows. Arch. 2011;459:503–510. doi: 10.1007/s00428-011-1150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dizdar L., Tomczak M., Werner T.A., Safi S.A., Riemer J.C., Verde P.E., Stoecklein N.H., Knoefel W.T., Krieg A. Survivin and XIAP expression in distinct tumor compartments of surgically resected gastric cancer: XIAP as a prognostic marker in diffuse and mixed type adenocarcinomas. Oncol. Lett. 2017;14:6847–6856. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang X.-.H., Feng Z.-.E., Yan M., Hanada S., Zuo H., Yang C.-.Z., Han Z.-.G., Guo W., Chen W.-.T., Zhang P. XIAP is a predictor of cisplatin-based chemotherapy response and prognosis for patients with advanced head and neck cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang X.-.H., Liu L., Hu Y.-.J., Zhang P., Hu Q.-.G. Co-expression of XIAP and CIAP1 Play Synergistic Effect on Patient's Prognosis in Head and Neck Cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2019;25:1111–1116. doi: 10.1007/s12253-018-0533-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodríguez-Berriguete G., Torrealba N., Ortega M.A., Martínez-Onsurbe P., Olmedilla G., Paniagua R., Guil-Cid M., Fraile B., Royuela M. Prognostic value of inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) and caspases in prostate cancer: caspase-3 forms and XIAP predict biochemical progression after radical prostatectomy. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:809. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1839-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seligson D.B., Hongo F., Huerta-Yepez S., Mizutani Y., Miki T., Yu H., Horvath S., Chia D., Goodglick L., Bonavida B. Expression of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein is a strong predictor of human prostate cancer recurrence. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:6056–6063. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferreira C.G., van der Valk P., Span S.W., Ludwig I., Smit E.F., Kruyt F.A., Pinedo H.M., van Tinteren H., Giaccone G. Expression of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis as a novel prognostic marker in radically resected non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001;7:2468–2474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu W.-.Y., Kim H., Zhang C.-.L., Meng X.-.L., Wu Z.-.S. Clinical significance of autophagic protein LC3 levels and its correlation with XIAP expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Med. Oncol. 2014;31:108. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi Y.-.H., Ding W.-.X., Zhou J., He J.-.Y., Xu Y., Gambotto A.A., Rabinowich H., Fan J., Yin X.-.M. Expression of X-linked inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein in hepatocellular carcinoma promotes metastasis and tumor recurrence. Hepatology. 2008;48:497–507. doi: 10.1002/hep.22393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Augello C., Caruso L., Maggioni M., Donadon M., Montorsi M., Santambrogio R., Torzilli G., Vaira V., Pellegrini C., Roncalli M., Coggi G., Bosari S. Inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) expression and their prognostic significance in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Z., Han C., Feng J. Relationship of the expression levels of XIAP and p53 genes in hepatocellular carcinoma and the prognosis of patients. Oncol. Lett. 2017;14:4037–4042. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li S., Sun J., Yang J., Zhang L., Wang L.E., Wang X., Guo Z. XIAP expression is associated with pancreatic carcinoma outcome. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2013;1:305–308. doi: 10.3892/mco.2013.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frohwitter G., Buerger H., Korsching E., van Diest P.J., Kleinheinz J., Fillies T. Site-specific gene expression patterns in oral cancer. Head Face Med. 2017;13:6. doi: 10.1186/s13005-017-0138-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou S., Ye W., Shao Q., Qi Y., Zhang M., Liang J. Prognostic significance of XIAP and NF-κB expression in esophageal carcinoma with postoperative radiotherapy. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2013;11:288. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dizdar L., Jünemann L.M., Werner T.A., Verde P.E., Baldus S.E., Stoecklein N.H., Knoefel W.T., Krieg A. Clinicopathological and functional implications of the inhibitor of apoptosis proteins survivin and XIAP in esophageal cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018;15:3779–3789. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.7755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang S., Ding F., Luo A., Chen A., Yu Z., Ren S., Liu Z., Zhang L. XIAP is highly expressed in esophageal cancer and its downregulation by RNAi sensitizes esophageal carcinoma cell lines to chemotherapeutics. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2007;6:973–980. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.6.4195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nagata M., Nakayama H., Tanaka T., Yoshida R., Yoshitake Y., Fukuma D., Kawahara K., Nakagawa Y., Ota K., Hiraki A., Shinohara M. Overexpression of cIAP2 contributes to 5-FU resistance and a poor prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer. 2011;105:1322–1330. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shrikhande S.V., Kleeff J., Kayed H., Keleg S., Reiser C., Giese T., Büchler M.W., Esposito I., Friess H. Silencing of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) decreases gemcitabine resistance of pancreatic cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:3265–3273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu Y.-.C., Liu Q., Dai J.-.Q., Yin Z.-.Q., Tang L., Ma Y., Lin X.-.L., Wang H.-.X. Tissue microarray analysis of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP) expression in breast cancer patients. Med. Oncol. 2014;31:764. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0764-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang J., Liu Y., Ji R., Gu Q., Zhao X., Liu Y., Sun B. Prognostic value of the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein for invasive ductal breast cancer with triple-negative phenotype. Hum. Pathol. 2010;41:1186–1195. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wente S.R., Rout M.P. The nuclear pore complex and nuclear transport. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oka M., Yoneda Y. Importin α: functions as a nuclear transport factor and beyond. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2018;94:259–274. doi: 10.2183/pjab.94.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cautain B., Hill R., de Pedro N., Link W. Components and regulation of nuclear transport processes. FEBS J. 2015;282:445–462. doi: 10.1111/febs.13163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Çağatay T., Chook Y.M. Karyopherins in cancer. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2018;52:30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodriguez J.A., Lens S.M.A., Span S.W., Vader G., Medema R.H., Kruyt F.a.E., Giaccone G. Subcellular localization and nucleocytoplasmic transport of the chromosomal passenger proteins before nuclear envelope breakdown. Oncogene. 2006;25:4867–4879. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin J., Hu J. SeqNLS: nuclear localization signal prediction based on frequent pattern mining and linear motif scoring. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramazi S., Zahiri J. Posttranslational modifications in proteins: resources, tools and prediction methods. Database (Oxford) 2021;2021:baab012. doi: 10.1093/database/baab012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hornbeck P.V., Zhang B., Murray B., Kornhauser J.M., Latham V., Skrzypek E. PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs and recalibrations. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2015;43:D512–D520. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kato K., Tanaka T., Sadik G., Baba M., Maruyama D., Yanagida K., Kodama T., Morihara T., Tagami S., Okochi M., Kudo T., Takeda M. Protein kinase C stabilizes X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) through phosphorylation at Ser(87) to suppress apoptotic cell death. Psychogeriatrics. 2011;11:90–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8301.2011.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hou Y., Allan L.A., Clarke P.R. Phosphorylation of XIAP by CDK1-cyclin-B1 controls mitotic cell death. J. Cell Sci. 2017;130:502–511. doi: 10.1242/jcs.192310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lotocki G., Alonso O.F., Frydel B., Dietrich W.D., Keane R.W. Monoubiquitination and cellular distribution of XIAP in neurons after traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:1129–1136. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000086938.68719.E0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang Y., Fang S., Jensen J.P., Weissman A.M., Ashwell J.D. Ubiquitin protein ligase activity of IAPs and their degradation in proteasomes in response to apoptotic stimuli. Science. 2000;288:874–877. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5467.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shin H., Okada K., Wilkinson J.C., Solomon K.M., Duckett C.S., Reed J.C., Salvesen G.S. Identification of ubiquitination sites on the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein. Biochem. J. 2003;373:965–971. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schile A.J., García-Fernández M., Steller H. Regulation of apoptosis by XIAP ubiquitin-ligase activity. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2256–2266. doi: 10.1101/gad.1663108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arroyo J., Price M., Straszewski-Chavez S., Torry R.J., Mor G., Torry D.S. XIAP protein is induced by placenta growth factor (PLGF) and decreased during preeclampsia in trophoblast cells. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 2014;60:263–273. doi: 10.3109/19396368.2014.927540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Baek H.-.S., Kwon Y.-.J., Ye D.-.J., Cho E., Kwon T.-.U., Chun Y.-.J. CYP1B1 prevents proteasome-mediated XIAP degradation by inducing PKCε activation and phosphorylation of XIAP. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2019;1866 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2019.118553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hong S.-.W., Shin J.-.S., Moon J.-.H., Jung S.-.A., Koh D.-.I., Ryu Y., Park Y.S., Kim D.Y., Park S.-.S., Hong J.K., Kim E.H., Kim M.J., Jeong H.-.R., Bae I.H., Ahn Y.-.G., Suh K.H., Cho I.-.J., Kang J.-.S., Hong Y.S., Lee J.S., Jin D.-.H., Kim T.W. Chemosensitivity to HM90822, a novel synthetic IAP antagonist, is determined by p-AKT-inducible XIAP phosphorylation in human pancreatic cancer cells. Invest. New Drugs. 2020;38:1696–1706. doi: 10.1007/s10637-020-00956-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhou H.-.Z., Zeng H.-.Q., Yuan D., Ren J.-.H., Cheng S.-.T., Yu H.-.B., Ren F., Wang Q., Qin Y.-.P., Huang A.-.L., Chen J. NQO1 potentiates apoptosis evasion and upregulates XIAP via inhibiting proteasome-mediated degradation SIRT6 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Commun. Signal. 2019;17:168. doi: 10.1186/s12964-019-0491-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nakhaei P., Sun Q., Solis M., Mesplede T., Bonneil E., Paz S., Lin R., Hiscott J. IκB kinase ε-dependent phosphorylation and degradation of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis sensitizes cells to virus-induced apoptosis. J. Virol. 2012;86:726–737. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05989-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hanson A.J., Wallace H.A., Freeman T.J., Beauchamp R.D., Lee L.A., Lee E. XIAP monoubiquitylates Groucho/TLE to promote canonical Wnt signaling. Mol. Cell. 2012;45:619–628. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sun C., Cai M., Gunasekera A.H., Meadows R.P., Wang H., Chen J., Zhang H., Wu W., Xu N., Ng S.C., Fesik S.W. NMR structure and mutagenesis of the inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein XIAP. Nature. 1999;401:818–822. doi: 10.1038/44617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]