Highlights

-

•

Dynamic nature is a crucial factor for optimal enzyme activity.

-

•

Due to enormous complexity, it is difficult to directly correlate enzyme dynamics and activity.

-

•

This question is addressed here taking an industrially crucial proteolytic enzyme, bromelain.

-

•

We contemplated and correlated the structure, dynamics and activity of bromelain in versatile chemicals.

-

•

In all the cases, a robust relationship between active-site dynamics and activity emerges.

-

•

Microsecond active-site dynamics is probably a key factor for activity.

Keywords: Bromelain, Activity, Conformational dynamics, Structure, Crowder, GnHCl, Sucrose

Abstract

Proteins are dynamic entity with various molecular motions at different timescale and length scale. Molecular motions are crucial for the optimal function of an enzyme. It seems intuitive that these motions are crucial for optimal enzyme activity. However, it is not easy to directly correlate an enzyme's dynamics and activity due to biosystems' enormous complexity. amongst many factors, structure and dynamics are two prime aspects that combinedly control the activity. Therefore, having a direct correlation between protein dynamics and activity is not straightforward. Herein, we observed and correlated the structural, functional, and dynamical responses of an industrially crucial proteolytic enzyme, bromelain with three versatile classes of chemicals: GnHCl (protein denaturant), sucrose (protein stabilizer), and Ficoll-70 (macromolecular crowder). The only free cysteine (Cys-25 at the active-site) of bromelain has been tagged with a cysteine-specific dye to unveil the structural and dynamical changes through various spectroscopic studies both at bulk and at the single molecular level. Proteolytic activity is carried out using casein as the substrate. GnHCl and sucrose shows remarkable structure-dynamics-activity relationships. Interestingly, with Ficoll-70, structure and activity are not correlated. However, microsecond dynamics and activity are beautifully correlated in this case also. Overall, our result demonstrates that bromelain dynamics in the microsecond timescale around the active-site is probably a key factor in controlling its proteolytic activity.

Graphical abstract

Protein dynamics in the microsecond timescale around the active-site of a plant enzyme, bromelain control its proteolytic activity.

1. Introduction

Since Crum-Brown and Fraser's groundbreaking work in 1865, [1] innumerable number of times, the structure-activity relationship of a biomolecule has been observed, contemplated, and established. [2], [3] However, one can not predict a general rule of the relationship because of biomolecules' enormous complexity. Furthermore, a protein structure is not rigid; instead, it is best presented as an ensemble average of several closely related conformations. [4], [5] These conformations differ slightly from one to another, and there is always an interconversion between them. [5], [6] Understandably, this interconversion timescale, in other words, the protein's flexibility, should have a profound effect on its functional behaviour, i.e., activity. Dynamics in the µs timescale drew the most attention, as enzyme catalysis, signal transduction, protein-protein interactions, and so on occur in this timescale. [5], [6]

NMR provides vital information about such fluctuations. [7] However, NMR study is restricted only to small proteins [8], [9] and requires of high concentration (mM) of the sample, at which most of the protein tends to form aggregates. [10] Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) also provides details of protein fluctuation dynamics, [11] but is limited with tedious instrumentation, analysis, and the inherent difficulty in attaching the protein with chip-surface not compromising its dynamics. [12] Fluorescence spectroscopy is another powerful technique to study biomolecules, though a bulk level measurement cannot furnish any dynamic information as these dynamics are uncorrelated. [7,13] To overcome this, single molecular fluorescence resonance energy transfer (smFRET) and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) are used routinely. [14] In these experiments, the conformational dynamics of a protein is obtained in real-time. [7,15, 16]

Although FCS is not a true single molecular experiment, this diffusion-based technique holds some advantages over smFRET in the sense that (i) the protein need not be immobilised, that might perturb its conformation, (ii) better time resolution can be achieved, and (iii) more straightforward instrumentation is applied. [15,17]

In the present contribution, we applied FCS to find the possible dynamic-activity relationship of a protein. We have chosen bromelain as the model protein for this purpose. It is an industrially important cysteine protease derived from pineapple. [18] Earlier, bromelain's structure, stability, and activity were examined in the presence of various external agents like denaturants, sugars, crowders, ionic liquids, and deep eutectic solvents. [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27] In some cases, a beautiful correlation between its stability and activity was established. [[19], [20], [21],24,26] However, the critical dynamical parameter of bromelain has not been studied till date. Bromelain's activity is controlled by His-158 and Cys-25 residues. [28], [29] We tagged this free Cys-25 of bromelain with a fluorescent coumarin derivative to get the structural (hydrodynamic radius) and dynamical (conformational fluctuation dynamics around Cys-25) information through FCS and other spectroscopic techniques. Proteolytic activity of bromelain is measured using UV–visible spectroscopy, taking casein as the substrate.

Although it seems inevitable, it is not easy to directly correlate an enzyme's dynamics and activity due to biosystems' enormous complexity. Further, the observed change in activity might not be due to dynamical variation but is a consequence of structural alteration. Initially, we started with two osmolytes: guanidine hydrochloride (GnHCl, one of the most used chemical denaturant) and sucrose (one of the most studied protein-stabilizer). We found that all the three parameters, i.e., structure, dynamics, and activity, are beautifully correlated in both the cases. However, it is difficult to comment on the role of dynamics in the functional response explicitly. To do so, we searched for some reagent, for which structural transition and functional response apparently does not have any correlation. After a thorough search, we came up with Ficoll-70, which meets the criterion that structure and function are uncorrelated. The rest of the article presents the data and analysis regarding this and demonstrates a close relationship between active-site dynamics and activity of bromelain.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials and methods

Bromelain, casein, 7-diethylamino-3-(4-maleimidophenyl)−4-methylcoumarin (CPM), guanidine hydrochloride (GnHCl), sucrose and Ficoll-70 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Tricholoro acetic acid was from Alfa-Aesar. Analytical grade di-sodium hydrogen phosphate and sodium dihydrogen phosphate were purchased from Merck, India, and used to prepare buffer (pH 7.4). Dialysis membrane tubing (12 kD cutoff) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and was washed according to the procedure given by Sigma-Aldrich. Centrifugal filter units (Amicon Ultra, 10 kD cutoff) have been purchased from Merck Millipore, Germany. HPLC grade dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was purchased from S. D. Fine Chemicals Limited, India.

2.2. Protein labelling and sample preparation

Bromelain contains five cysteine groups, amongst which Cys-22/Cys-63, Cys-57/Cys-96, and Cys-152/Cys-199 form disulfide linkages. [28,30] The cysteine residue at 25th position is free and is tagged selectively by the thiol-reactive CPM using a common procedure (Scheme 1a). Briefly, bromelain (192 mg) was dissolved in 19 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). CPM (3.2 mg) was dissolved in 1 mL of DMSO and added dropwise to the stirred solution of bromelain in the buffer. The reaction mixture was stirred at 20 °C for 12 hrs, followed by dialysis against 1000 mL of 1:15 (v/v) DMSO and phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) at 5 °C. The dialysis medium was replaced every 12 hrs for 4 days and then was replaced by only buffer for another 4 days. Tagged protein was concentrated using the 10 kD cutoff centrifugal filtration unit. The tagging procedure is represented in scheme 1b.

Scheme 1.

Tagging of bromelain. (a) Amino acid sequence and secondary structure of Bromelain. The structure is taken from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 1W0Q). The free cysteine at the 25th position is highlighted with red colour. (b) Covalent tagging of the thiol group of Cys-25 by 7-diethylamino-3-(4-maleimidophenyl)−4-methyl coumarin (CPM).

Samples were prepared by mixing the required amount of tagged bromelain with the required amount of GnHCl, sucrose and Ficoll-70 stock solution in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). 600 gL–1 GnHCl, 800 gL–1 sucrose, and 350 gL–1 Ficoll-70 were used as the stock. Samples were incubated for 12 hour before performing any experiment. Protein concentration was maintained as 4 µM for steady-state and time-resolved fluorescence measurements and 10 µM for the CD experiment. For FCS measurements, the protein concentration was kept as 5 nM.

2.3. Activity measurement

We determined the proteolytic activity of bromelain by UV-visible spectrophotometer, taking casein as the substrate.[[20], [26]] 0.3 mL of 1.5% (w/v) casein in pH 7.4 50 mM phosphate buffer was incubated with 0.3 mL 0.12 mg mL–1 bromelain in the same buffer at 37 °C for 10 min. The reaction was quenched by the addition of 0.3 mL 200 mM trichloroacetic acid. The residue was removed by centrifugation and the absorbence of the supernatant was measured at 280 nm. The value of the absorbence at 280 nm is proportional to the degree of the proteolysis of bromelain. Thus, we represent bromelain's activity as the absorbence value obtained for 10 min digestion. Appropriate blank (consists of all the constituent except bromelain) is subtracted from every measurement to nullify the effect of viscosity.

2.4. Instrumentation

Centrifugation was done in Eppendorf Centrifuge 5810R at 5000 rpm.

We recorded circular dichroism spectra on a commercial CD spectrometer (Jasco J-815, Japan). CD data was analysed using CDNN software to get the secondary structural components. [31]

The steady-state absorption and emission spectra were recorded on a commercial UV−visible spectrophotometer (Schimadzu 2450, Japan) and spectrofluorimeter (FluoroMax4, JobinYvon, USA), respectively. Samples were excited at 390 nm for all the emission measurements. Area under the emission curve is taken as the fluorescence intensity.

Time-resolved fluorescence were measured on a commercial TCSPC setup (LifeSpec-II, Edinburgh Instruments, UK). Samples were excited with a 375 nm pulsed laser diode (EPL-375, Edinburgh Instruments, UK). The transients were fitted by a sum of exponential functions

| (1) |

where I(t) is the fluorescence intensity at time t and is the amplitude associated with the fluorescence lifetime component . The average fluorescence lifetime was calculated as

| (2) |

FCS experiments were done on a home-built set-up. [32], [33], [34] The detailed instrumentation is described elsewhere and in the supporting material (Section S1 of the supporting material). [32], [33], [34], [35] The output fluorescence autocorrelation, G(τ), was fitted by either Eq. (3) or Eq. (4). [13]

| (3) |

| (4) |

where N is the number of particles in the observation volume, is the diffusion time, ω = r/l is the ratio of radial and axial radius of 3D Gaussian volume, is the time component and a is the amplitude of the corresponding process other than diffusion. Eq. (3) was used for the pure diffusion process of fluorescent particle in a monodisperse solution, whereas Eq. (4) was used when additional process other than diffusion contributes to the fluorescence fluctuation. The choice of fitting function in the present study has been elaborated in the results and discussion section. The translational diffusion coefficient and the hydrodynamic radius can be calculated from the diffusion time () and radius of the observation volume (r) as

| (5) |

| (6) |

where kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature and η is the viscosity of the medium. The radius ‘r’ of the 3D Gaussian volume was estimated from the diffusion coefficient of rhodamine 6 G (R6G) in water (Dt = 4.14 × 10−6 cm2 s − 1) at 298 K following standard procedure. [36] In the presence of external agents (like GnHCl, sucrose or Ficoll-70) viscosity and refractive index of the solution changes. These effects are taken care of by performing control experiments with R6G at every experimental points. R6G is a rigid dye molecule and will not undergo any structural change with change in the viscosity or refractive index. Therefore, any change in the diffusion time of R6G in the presence of additives will be solely due to the modulation of the medium property. Using the measured values of the diffusion time of R6G and hydrodynamic radius of the same the hydrodynamic radius of bromelain was calculated as

| (7) |

2.5. Calculation of free energy

The structural and dynamical transition of bromelain can be described either by a two-state or a three-state model (see discussion for justification). A two-state model can be represented as

| (8) |

The variation of a spectroscopic signal in this case is described by [35]

| (9) |

where, and are the spectroscopic signals for the native and the final states, respectively, and A is defined as: [37]

| (10) |

In the above equation, is the free energy change in the absence of any external agent and m is the slope of free energy change against the additive concentration. R and T are universal gas constant and absolute temperature, respectively. The midpoint of transition can be calculated as

| (11) |

A three-state model can be represented as

| (12) |

Here, I is intermediate state. In this case, variation of a spectroscopic signal can be expressed as

| (13) |

were, is the spectroscopic signal of the intermediate state. and are defined as

| (14) |

| (15) |

and are the free energy change in the absence of any external agent for and transitions, respectively. Similarly, and are the slope of free energy change against the additive concentration for and transitions, respectively. Like previous case, transition mid-points are calculated as:

| (16) |

| (17) |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Steady-state and time-resolved emission study

CPM is a positive solvatochromic dye and is weakly fluorescent in an aqueous medium ( = 482.0 nm). Upon tagging to Cys-25 residue of bromelain, it becomes highly fluorescent, probably because of the restricted rotation of the 7-diethylamino group inside the protein matrix, and the emission maximum is found at 475.0 nm (see figure S1 of the supporting material). A blue shift of CPM emission also points towards the inclusion of CPM in protein as the protein core is more hydrophobic. Tagging efficiency is calculated to be 0.8. We confirmed that CPM tagging does not perturb the secondary structure (see figure S2 of the supporting material) and stability.

Upon addition of GnHCl up to 75 gL–1, we observe a slight blue shift (1.5 nm) of CPM-bromelain emission with an increase in the intensity. It suggests that the probe moves in a relatively more hydrophobic and restricted environment than that in the native state. With a further increase in the concentration of GnHCl, a gradual redshift in the emission spectrum with a concomitant decrease in the intensity is observed. In the presence of 400 gL–1 GnHCl the emission maximum reaches to 479.0 nm (see Figs. 1a, 1b and 1c), suggesting the formation of a less hydrophobic and less rigid environment around the probe. We also performed a time-resolved emission study to have a clear picture of environmental modulation around CPM tagged to bromelain (Figs. 1d and 1e). The fluorescence lifetime of CPM in native bromelain is 3.3 ns, which increases up to 75 gL–1 GnHCl. However, beyond that, lifetime gradually decreases. Eventually, the result agrees well with the steady-state emission study and proves that at lower GnHCl content bromelain probably takes up a more compact conformation (at least around Cys-25 residue). At higher GnHCl concentration, bromelain probably takes up an elongated conformation where surrounding amino acids around CPM moves further away.

Fig. 1.

Steady-state and time-resolved emission study. (a) Emission spectra, (b) variation of emission maxima, (c) variation of emission intensity, (d) representative fluorescent transients, (e) variation of fluorescence lifetime of CPM tagged bromelain with GnHCl. (f) Emission spectra, (g) variation of emission maxima, (h) variation of emission intensity, (i) representative fluorescent transients, (j) variation of fluorescence lifetime of CPM tagged bromelain with sucrose. (k) Emission spectra, (l) variation of emission maxima, (m) variation of emission intensity, (n) representative fluorescent transients, (o) variation of fluorescence lifetime of CPM tagged bromelain with ficoll-70. Bromelain concentration is kept at 4 µM, pathlength is 1 cm, and the excitation wavelength is 390 nm and 375 nm for steady-state and time-resolved emission, respectively. Every experimental point is the average value of three independent measurements, and the error bar represents the standard deviation of the mean. The solid black lines in the figures (b), (c), (e), (g), (h), (j), (l), (m) and (o) are eye guides. The solid black lines in figures (d), (i), and (n) are fitting lines to the fluorescent transients following equation 1.

The effect of sucrose is just opposite, however, to a lesser extent than that of GnHCl (Figs. 1f, 1g, 1h, 1i and 1j). Up to 200 gL–1 sucrose, a slight redshift of 1 nm with a decrease in the emission intensity and fluorescence lifetime of CPM indicate the formation of a slightly open structure of bromelain where the probe moves in a less hydrophobic and restricted environment. With further increase in the sucrose concentration, a gradual blue shift of the emission maximum with a concomitant increase in the intensity and lifetime is observed. It suggests the formation of a more compact structure where the probe goes into a more hydrophobic and restricted environment.

For Ficoll-70, the change of steady-state and time-resolved emission profile of CPM tagged bromelain is too subtle to emphasize any structural change of bromelain (see Figs. 1k, 1l, 1m, 1n and 1o). All the data are tabulated in table S1 of the supporting material.

3.2. Circular dichroism (CD) experiment

CD spectroscopy in the far UV region provides protein's secondary structural parameters, namely α-helicity, β-sheet, β-turn and random coil (Fig. 2). [38] CD signal in the region 190 nm to 230 nm is important for this purpose. However, we cannot record the CD data at lower wavelength than 210 nm as output voltage was exceeding the instrument threshold. However, one can still comment qualitatively on the modulation of secondary structural contents.

Fig. 2.

Circular dichroism (CD) measurement. CD spectra of untagged bromelain in the presence of different (a) GnHCl concentrations, (b) sucrose concentrations. and (c) different ficoll-70 concentrations. Bromelain concentration is kept at 10 µM, and pathlength is 1 mm.

With increasing GnHCl concentration up to ∼75 gL−1, the CD signal becomes more negative in the region 215 nm to 222 nm suggesting increase in the compact secondary structures like α-helicity and β-sheet. With further increase in GnHCl concentration, CD signal in this region becomes less negative suggesting disrupture of this compact secondary structure, most probably with a concomitant increase in the random coil percentage.

With sucrose, CD signal in the region 215 nm to 222 nm becomes increasingly more negative with increasing concentration hinting that sucrose acts as structure maker for bromelain.

On the other hand, Ficoll-70 does not induce a significant secondary structural alteration in bromelain

3.3. Single molecular level FCS measurement

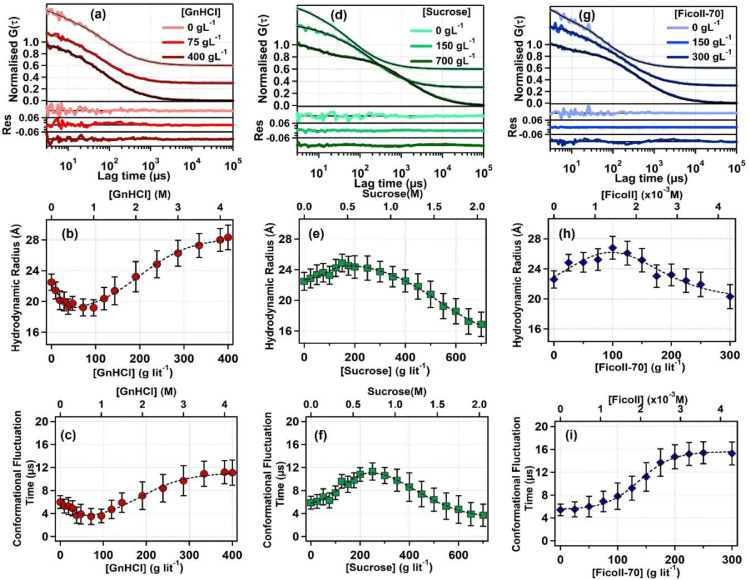

We applied FCS measurement to investigate the behaviour of bromelain at the single molecular level. The fluorescence autocorrelation traces for CPM can be fitted with Eq. (3), and the diffusion time is measured as 24 µs (see figure S3 of the supporting material). However, the fluorescence autocorrelation curves for CPM tagged bromelain cannot be fitted with Eq. (3). Incorporation of a relaxation term (i.e., Eq. (4)) greatly improves the quality of the fitting (Figure S3 of the supporting material). Earlier, we proved the origin of this extra component to be conformational fluctuation dynamics of amino acids around CPM tagged to Cys-25 of bromelain. [26] For CPM tagged bromelain, diffusion time () is 70 µs, and the conformational fluctuation time is 6 µs. The increase in of CPM tagged bromelain compared to free CPM proves that CPM is attached to bromelain. is converted to following Eqs. (4) and 5. The hydrodynamic radius of bromelain in its native state is calculated to be 22.5 Å, which matches well with the previous experimental reports. [26,39] A few fluorescence intensity autocorrelation traces of CPM tagged bromelain in the presence of GnHCl, sucrose, and Ficoll-70 are given in Figs. 3(a), 3(d), and 3(g), respectively, along with the fitting and residuals.

Fig. 3.

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) study. (a) Some representative normalized fluorescence intensity autocorrelation curves of CPM tagged bromelain in the presence of different GnHCl concentrations. (b) Variation of hydrodynamic radius and (c) variation of conformation fluctuation time with increasing GnHCl concentration. (d) Some representative normalized fluorescence intensity autocorrelation curves of CPM tagged bromelain in the presence of different sucrose concentrations. (e) Variation of hydrodynamic radius and (f) variation of conformation fluctuation time with increasing sucrose concentrations. (g) Some representative normalized fluorescence intensity autocorrelation curves of CPM tagged bromelain in the presence of different Ficoll-70 concentrations. (h) variation of hydrodynamic radius and (i) variation of conformation fluctuation time with increasing Ficoll-70 concentration. Bromelain concentration is kept at 5 nM; the excitation wavelength is 405 nm. Every experimental point is the average value of three independent measurements, and the error bar represents the standard deviation of the mean. The solid black lines in (a), (d), and (g) are the fitting lines using Eq. (4). The residuals of the fittings are also shown. The dotted black lines in the (b), (c), (e), (f), and (h) are the fitting lines using Eq. (13). The dotted black line in the (i) is the fitting line using Eqn 9

3.3.1. Structural Transition:

Structural transition of bromelain in the presence of GnHCl: Withincreasing GnHCl concentration, the hydrodynamic radius () gradually decreases and reaches to ∼19 Å around 40–90 gL–1 GnHCl (see Fig. 3b and table S3 of the supporting materail). With further increase in the GnHCl concentration, of bromelain increases monotonically and reaches 28 Å at 400 g L–1. Such an observation agrees with many previous results, where it is shown that GnHCl is primarily a strong denaturant for proteins; however, at low concentration, it compacts protein structure. [40], [41], [42], [43] The result is also following our steady-state emission and CD study. The unfolding profile indicates that the transition cannot be approximated as a two-state process. In addition to the native state (at 0 gL–1 GnHCl) and denatured state (at 400 gL–1 GnHCl), an additional intermediate state of bromelain around 75 gL–1 GnHCl is proposed. During GnHCl induced denaturation of bromelain, the presence of an intermediate state is suggested at lower GnHCl concentration previously. [43,44] The state around 75 gL–1 GnHCl cannot be represented as a linear combination of the native and the denatured states with non-negative coefficients. The presence and identification of such an intermediate state in the course of a protein unfolding is significant.

The oldest and probably the easiest comprehendible theory about GnHCl denaturation is the preferential accumulation of GnHCl at the protein surface compared to the protein core. [45,46] In the denatured state, the surface area of the protein increases, and GnHCl favours such conformation with higher surface area, i.e., elongated conformation. On a molecular level, it has been proved that the hydrophobic face of Gdm+ in GnHCl salt stack against hydrophobic side chains of the protein. [47,48] This modulates the intra-hydrophobic interaction within the protein and distorts the protein structure. [47,49,50] It was also suggested that Gdm+ could denature proteins by breaking the salt bridge (electrostatic interaction between oppositely charged amino acid side chains) through competitive binding with COO− side groups. [51,-52]. The denaturating ability of GnHCl is sometimes related to the water structure breaking ability of it. [53] The formation of a more compact intermediate state of bromelain at lower GnHCl concentration can be rationalized as follows. Gdm+ ion is common in GnHCl and arginine. Arginine is one of the three most abundant amino acids in proteins, and bromelain contains 12 arginine [54,55] There is a possibility that bromelain contains specific binding pockets for arginine, where Gdm+ binds preferentially. Such binding lowers the energy of bromelain and might compacts it. [46,49,[54], [55]] Some reports including determination of protein structure at lower GnHCl concentration hints that protein GnHCl interaction might be non-specific. [56] However, in that case also, protein will be stiffened due to cross linking action of Gdm+ cation and through eentropic stabilization [57,58].

Structural transition of bromelain in the presence of sucrose: On addition of sucrose, of bromelain increased and reaches a value of ∼25 Å at around 150 gL–1 (see Fig. 3e and table S3 of the supporting material). With further increase in sucrose concentration, gradually decreases and reaches to 17.6 Å at 700 gL–1 sucrose. We proposed an intermediate state of around 150 gL–1 sucrose, which cannot be described as a linear combination of the initial and the final state with non-negative coefficients. Sugar's non-preference for the protein surface [45,59] explains the compaction of bromelain at high sucrose content as is observed frequently with other proteins60. [60,61]

Many theories are proposed to explain such observations at the molecular level, like (i) a particular state of protein might be entrapped in a highly viscous sugar matrix, [62] (ii) hydrogen bonds are formed between sugar and protein and modulates protein behaviour, [63] (iii) water molecules are trapped between sugar and protein surface, and sugar layer stabilizes the protein, [64] (iv) sugar and protein may interact directly assisted by water entrapment. [65] However, in the present case, we observed an increase in the of bromelain in the presence of a small amount of sucrose. The result is surprising and needs a considerable effort to rationalise it. There are at least two reports for the same protein (bromelain) where sucrose is reported to cause destabilisation. Rani et al. observed that sucrose destabilizes bromelain at a lower concentration. [19] Habib et al. proposed that preferential hydration (preference replacement of hydration water by sucrose) model could explain such unexpected destabilization leading to the elongation of bromelain. [22] They showed that the preferential hydration of the denatured state of bromelain is higher compared to its native state and anticipated as the main reason for the sugar-induced elongation of bromelain. [22] Ajito et al. showed that such preferential hydration model is only operational at lower sucrose concentration. [66]

Structural transition of bromelain in the presence of Ficoll-70: Similarly, bromelain's initially increases monotonically with increasing Ficoll-70 and reaches to 26.8 Å at around 100 gL–1 (see Fig. 3h and table S3 of the supporting material). With further increase in Ficoll-70 concentration, of bromelain gradually decreases and reaches 20.3 Å at 300 gL–1. Here also, we propose the presence of an intermediate state, which cannot be represented as a linear combination of the initial and the final state.

Protein behaviour in a crowded milieu is very much modulated and is a delicate balance between the entropic and enthalpic terms. [67], [68], [69], [70] The main component of the entropic part is positional restriction due to excluded volume, the pressure exerted on the protein surface by crowders, and the associated modulation of water entropy. [[33], [34], [35],67,68,[70], [71], [72], [73]] The enthalpic component arises because of modified energetics and interactions. [73] At lower concentration, specific interaction between Ficoll-70 and bromelain probably decides bromelain's fate (elongation of the tertiary structure). However, at an increased concentration, probably the excluded volume effect and pressure effect predominates and compacts bromelain. Further study is needed to know the exact forces responsible for such a behaviour.

From previous literature, one could find a thermal stability trend of bromelain with GnHCl [19], sucrose [21] and Ficoll-70 [20]. General expectation is that more compact conformation is more stable, whereas more elongated conformation is less stable. Keeping this expectation in mind the observed trend of structural change matches qualitatively with the previous observation of bromelain stability in different perturbations.

3.3.2. Modulation of domain-III conformational dynamics:

As mentioned earlier, the time component of 6 µs is due to the conformational dynamics () of bromelain [26] It reflects the timescale of fluorescence modulation of the tagged dye (CPM) due to local structural fluctuation by virtue of side-chain dynamics. The change of with changing GnHCl, sucrose and Ficoll-70 concentration are plotted in the Figs. 3(c), 3(f) and 3(i), respectively. With GnHCl, gradually decreases and reaches 3.5 µs at ∼75 gL–1 GnHCl. With further increase of GnHCl, gradually increases and reaches 11.1 µs at 400 gL–1 GnHCl. With sucrose, gradually increases and reaches 11.3 µs at 250 gL–1 sucrose. With further increase of sucrose, gradually decreases and reaches 3.7 µs at 700 gL–1 sucrose. The variation of with GnHCl and sucrose correlates well with the structural alteration (see Figs. 3(b) and 3(e)). At lower GnHCl concentration and higher sucrose concentration, the size of bromelain decreases. Therefore, the electron-rich amino acid residues around the probe move closer. Thus the length scale of side-chain dynamics decreases, and the timescale of such dynamics should also decrease. On the other hand, at higher GnHCl and lower sucrose concentrations, the size of bromelain increases, and the length scale of conformational dynamics should increase. Expectedly, we observed an increase in .

However, unlike GnHCl and sucrose, with ficoll-70, value gradually increases and reaches to 15.3 µs at 300 gL–1 Ficoll-70. On the other hand, at higher concentrations of ficoll-70 (beyond 100 gL–1), bromelain gets compacted. Therefore, we might expect a gradual decrease in value beyond 100 gL–1 ficoll-70. But that is not the case here. It is thus clear that modulation is not a consequence of the structural alteration. It is just another independent parameter that measures the flexibility or rigidity of the surrounding amino acids around CPM tagged to bromelain. Probably in the presence of macromolecules like Ficoll-70, bromelain is restricted in a smaller volume due to volume-exclusion. It provides a crowder-induced hindrance leading to a decrease in the freedom of a protein's motion, and because of such restriction, dynamics becomes slower.

3.3.3. Presence of Intermediate in the Transition Path

Detection and identification of intermediate state during protein folding-unfolding study is very important to understand protein folding pathway, assembly process, protein-misfolding and aggregation. The structural transition of bromelain in the presence of GnHCl, sucrose and Ficoll-70 prove that all the transition involves an intermediate state. For, GnHCl and sucrose, the intermediate state can be identified also in dynamical transition. However, for Ficoll-70, such intermediate state is not identified through the dynamical transition. In the case of GnHCl induced transition of bromelain, the intermediate state can be characterized as a state where the secondary (from CD measurement) and tertiary (from measurement) structures get compacted with lower solvent exposure than the native state with more flexibility of the active site. With sucrose induced transition, the intermediate state can be characterised as a less flexible state with partial destruction of secondary and tertiary structure with higher solvent exposure. For ficoll-70 induced transition, the intermediate state can be characterised as less flexible with an almost similar secondary structure where tertiary structure gets destroyed partially with similar solvent exposure to the native state.

3.3.4. Thermodynamic Parameters of the Structural and Dynamical Transition:

We fitted variation data to a three-state model (by Eq. (13)) to estimate the thermodynamic parameters associated with the structural changes of bromelain in the presence of GnHCl, sucrose, and ficoll-70. To calculate the thermodynamic parameters associated with dynamical changes of bromelain we fitted variation data in the presence of GnHCl and sucrose to a three-state model (using Eq. (13)) and Ficoll-70 to a two-state model (using Eq. (9)). The results are summarised in the table 1. Similar free energy change is observed in guanidine hydrochloride induced denaturation of a similar protein papain. [41] Free energy change in thermal denaturation of bromelain is also in this range. [19,21] The interesting point is that the corresponding values for structural and dynamical transition with GnHCl and sucrose are similar. It gives a hint that the structural and dynamical evolution of bromelain in the presence of GnHCl and sucrose are probably somewhat correlated.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic parameters for structural and dynamical changes of bromelain induced by GnHCl, sucrose, and ficoll-70.

| GnHCl | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For structural transition | For dynamical transition | ||||||||||

| 1200 | 2000 | 65 | 10 | 18.5 | 200 | 1200 | 2000 | 42 | 11 | 28.6 | 181..8 |

| Sucrose | |||||||||||

| For structural transition | For dynamical transition | ||||||||||

| 1550 | 2350 | 11 | 6 | 141 | 391.6 | 1500 | 2550 | 16 | 5 | 93.8 | 425.0 |

| Ficoll-70 | |||||||||||

| For structural transition | For dynamical transition | ||||||||||

| 600 | 1300 | 10 | 10 | 60.0 | 130.0 | 2800 | 20 | 140.0 | |||

s are in cal mol–1; m is in cal mol–1 g–1 L, and s are in g L–1.

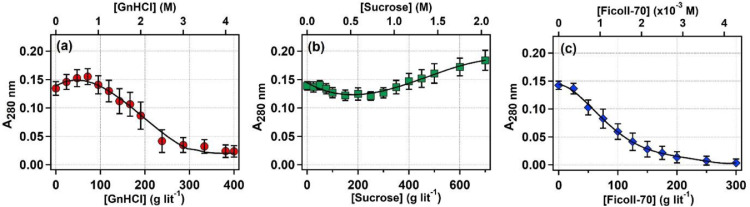

3.4. Activity measurement

We carried out the proteolytic activity of bromelain in the presence of different concentrations of GnHCl, sucrose and Ficoll-70 taking casein as the substrate. For GnHCl, at lower concentrations (till 75 gL–1), a slight increase in the activity has been observed (see Fig. 4a and table S4 of the supporting materaial). Beyond that, the activity gradually decreases. In presence of sucrose, bromelain's activity marginally decreased till 200 gL–1 and then the activity gradually increases (Fig. 4b and table S4 of the supporting material). In case of Ficoll-70, the activity gradually decreases with increasing its concentration (Fig. 4c and table S4 of the SI).

Fig. 4.

Activity measurement. (a) Variation of the proteolytic activity of untagged bromelain with increasing concentration of (a) GnHCl, (b) sucrose, and (c) Ficoll-70. Every experimental point is the average value of three independent measurements, and the error bar represents the standard deviation of the mean. Solid black lines are the eye guides.

3.5. Structure dynamics activity relationship

Both positive and negative effect in the activity of bromelain with denaturant, sugar osmolyte and macromolecular crowder must be an outcome from their influences on protein conformation and dynamics. [57,74,75] These can directly interact with the protein to affect the rate of encounter between enzyme and substrate, can specifically stabilize or destabilise a particular conformation, or can inhibit the enzymatic reaction by blocking the binding site of the protein. These possibilities are to be considered to fully understand the complex biological reactions. For example, it is known that denaturants like guanidine hydrochloride interacts directly with the protein to destabilise its active conformer.[[18], [19]] Bhakuni et al. proposed some sort of binding interaction between active -site of bromelain and Ficoll-70 following molecular docking studies.[20] Moreover, in all the cases, the effect of associated water structure modulation must be taken into consideration. [57,76] Especially, osmolytes like sucrose are known to exert their effect on the activity of biomolecule by modulating water structure. [59,66]

A comprehensive elucidation of the correlation between bromelain activity, structure and dynamics is therefore very difficult and might even be misleading as it is an interplay of various factors. However, we attempted to find how activity depends on structure and dynamics to understand complex biochemical reactions a little better. In Fig. 5, we plotted the%-relative change of bromelain's hydrodynamic radius, the time constant of conformational dynamics, and activity.

Fig. 5.

%-relative change of hydrodynamic radius, active site dynamics and activity of bromelain in the presence of (a) GnHCl, (b) sucrose, and (c) Ficoll-70. The structure-dynamics-activity correlation is also highlighted.

3.5.1. Structure-activity relationship:

At higher GnHCl and lower sucrose concentration, bromelain becomes somewhat elongated (than its native state), and its proteolytic activity is reduced. Generally, a particular form of a protein (native state) is active, and activity decreased with the structural alteration. Therefore, such a loss in bromelain's action is expected at higher GnHCl and lower sucrose content. On the other hand, at lower GnHCl and higher sucrose content, bromelain takes up a more compact structure than its native state. Interestingly, in these cases, bromelain's activity also increases. Taken together, we observe a potent relationship between structure and activity of bromelain in the presence of GnHCl and sucrose. The structural transition of bromelain in the presence of Ficoll-70 is somewhat similar to that in the presence of sucrose. However, unlike sucrose, with Ficoll-70 the proteolytic activity continuously decreases. Beyond 100 gL–1 Ficoll-70, bromelain started to get compacted. But, contrary to the expectation, its activity decreases. At least in this case, we did not see any correlation between the structure and bromelain activity. We suspect that, probably, some other factor plays a key role here to control bromelain's proteolytic activity.

3.5.2. Dynamics-activity relationship:

Protein dynamics (in addition to structure) is another crucial factor that controls its property. The dynamics of the active-site of bromelain is expected to play a key role in controlling its activity and we expect a correlation between the active-site dynamics and the activity. Interestingly, at higher GnHCl and lower sucrose content, where bromelain adopts an elongated conformation and shows less activity, conformational fluctuation time gets increased. It suggests that bromelain takes a more rigid conformation here. Probably, more rigidity of the active site in the presence of a high amount of GnHCl and low amount of sucrose is somewhat responsible for bromelain's reduced activity. Intuitively, one might think that a decrease in conformational fluctuation time (that suggests a flexible active site) might increase bromelain's proteolytic activity. At lower GnHCl and higher sucrose concentration, the conformational fluctuation time of bromelain decreases, and its activity increases. Taken together, we get a strongcorrelation between active site dynamics of bromelain in the microsecond timescale with its activity for GnHCl and sucrose. However, we also observed a beautiful correlation between its structure and activity. Therefore, we are still not sure if dynamics play the crucial role in modulating its behaviour or the structural alteration. We observed that the structural transition of bromelain does not correlate well with its activity in the presence of Ficoll-70 (especially beyond 100 gL–1 ficoll-70 concentration). However, from the Fig. 5c, it is clear that even for Ficoll-70, we observe a convincing correlation between bromelain's dynamics and activity. With increasing ficoll-70 concentration, bromelain's active-site gets more and more rigid, and its activity gradually decreases. Taken together, we propose that the active site dynamics of bromelain in the microsecond timescale is probably the key factor that controls its activity.

Overall, we observed a robust relationship between the structure and activity as well as dynamics and activity of bromelain in the presence of GnHCl and sucrose. However, we observed that the structural transition of bromelain does not have any apparent correlation with its activity in the presence of ficoll-70 (especially beyond 100 gL–1 Ficoll-70 concentration), but dynamics and structure of bromelain are anti-correlated in the presence of Ficoll-70 also. Taken together, we propose that the active site dynamics of bromelain in the microsecond timescale is probably the key factor that controls its activity.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, we investigated the structural, dynamical, and functional response of an industrially important proteolyte, bromelain, in the presence of a chemical denaturant (GnHCl), a stabilizer (sucrose) and a macromolecular crowder (ficoll-70). The main findings can be summarised as follows: (i) GnHCl compacts the protein structure at low concentration with more helical content and denatures it at higher concentration with a concomitant loss in the helicity. Sucrose at a lower concentration slightly unfolds the protein with a loss in the helicity and, at a higher concentration, compacts it. Ficoll-70 unfolds the protein at a lower concentration and beyond it compacts bromelain's tertiary structure, with only a little modulation of the secondary structural parameters. (ii) Conformational fluctuation time () slightly decreases at low GnHCl concentration but increases at higher GnHCl concentration. In presence of sucrose, increases at lower concentration and decreases at higher concentration. With ficoll-70, we observe a monotonous increase in the active-site dynamics. (iii) Proteolytic activity of bromelain slightly increases at lower GnHCl concentration but decreases at higher GnHCl concentration. In the presence of sucrose, activity decreases at lower concentrations and increases at higher concentrations. With ficoll-70, we observed a gradual decrease of enzymatic activity of bromelain. (iv) We observe a strong correlation between structure-dynamics, structure-activity and dynamics-activity in the presence of GnHCl. Also, with sucrose, we observed a beautiful relation between its structure dynamics, structure-activity and dynamics-activity. With Ficoll-70, on the other hand, there is no apparent correlation between structure-dynamics and structure-activity. However, a beautiful correlation between the active site dynamics and the activity is observed (see scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

A schematic correlation of structural, functional and dynamical response of bromelain in the presence of GnHCl, sucrose and ficoll-70. A robustcorrelation between structure-dynamics, structure-activity and dynamics-activity is observed in the presence of GnHCl and sucrose. However, with Ficoll-70, there is a correlation only between active site dynamics and activity.

Overall, we correlated the structure, dynamics, and activity of bromelain in the presence of three different classes of chemicals used routinely in the biophysical study. Our results demonstrate that the protein dynamics in the microsecond timescale around the active-site of bromelain is probably a critical factor to control its proteolytic activity.

Supporting material

Details of FCS setup; emission of CPM before and after tagging; CD spectra of untagged bromelain and CPM tagged bromelain, and their evolution with temperature; fluorescence autocorrelation trace for free CPM and CPM tagged bromelain with fitting comparison; tables of variation of emission maxima, emission intensity, lifetime, secondary structural contents, hydrodynamic radius, conformational fluctuation time, and activity of bromelain with GnHCl, sucrose, and ficoll-70.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Acknowledgements

ND thanks Council of Scientific and Industrial Research and SY thanks Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur, respectively, for providing graduate fellowships. ET thankful to the Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, India, for providing financial assistance as Institute Post-Doctoral Fellow. PS thanks Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur for infrastructure and support. This work is financially supported by Science and Engineering Research Board, Government of India (Grant No. EMR/2016/006555).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bbadva.2022.100041.

Contributor Information

Nilimesh Das, Email: nilimesh@iitk.ac.in.

Pratik Sen, Email: psen@iitk.ac.in.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Brown A.C., Fraser T.R. The Connection between Chemical Constitution and Physiological Action. Trans. R. Soc. Edinburgh. 1865;25:257. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadowski M.I., Jones D.T. The sequence–structure relationship and protein function prediction. Curr. Opi. Str. Biol. 2009;19:357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kundrotas P., Belkin S., Vakser I. Structure-function relationships in protein complexes. Biophys. J. 2018;114:46a. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper A. Thermodynamic fluctuations in protein molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1976;73:2740–2741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.8.2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo J., Zhou H.X. Protein allostery and conformational dynamics. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:6503–6515. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yon J.M., Perahia D., Ghelis C. Conformational dynamics and enzyme activity. Biochimie. 1998;80:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(98)80054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boehr D.D., Dyson H.J., Wright P.E. An NMR perspective on enzyme dynamics. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3055–3079. doi: 10.1021/cr050312q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frederick K.K., Marlow M.S., Valentine K.G., Wand A.J. Conformational entropy in molecular recognition by proteins. Nature. 2007;448:325–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenmesser E.Z., Bosco D.A., Akke M., Kern D. Enzyme dynamics during catalysis. Science. 2002;295:1520–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.1066176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hills B.P., Takacs S.F., Belton P.S. The effects of proteins on the proton N.M.R. transverse relaxation time of water. Mol. Phy. 1989;67:919–937. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suenaga A., Ichikawa M., Hatakeyama M., Yu X., Futatsugi N., Narumi T., Fukui K., Terada T., Taiji M., Shirouzu M., Yokoyama S. Molecular dynamics, free energy, and SPR analyses of the interactions between the SH2 domain of Grb2 and ErbB phosphotyrosyl peptides. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5195–5200. doi: 10.1021/bi034113h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capelli D., Parravicini C., Pochetti G., Montanari R., Temporini C., Rabuffetti M., Trincavelli M.L., Daniele S., Fumagalli M., Saporiti S., Bonfanti E., Abbracchio M.P., Eberini I., Ceruti S., Calleri E., Capaldi S. Surface plasmon resonance as a tool for ligand binding investigation of engineered GPR17 receptor, a G protein coupled receptor involved in myelination. Front. Chem. 2020;7:910. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2019.00910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakowicz J.R. 3rd Ed. Springer; New York: 2006. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michalet X., Weiss S., Jager M. Single-molecule fluorescence studies of protein folding and conformational dynamics. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:1785–1813. doi: 10.1021/cr0404343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quast R.B., Margeat E. Studying GPCR conformational dynamics by single molecule fluorescence. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2019;493 doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2019.110469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grime R.L., Goulding J., Uddin R., Stoddart L.A., Hill S.J., Poyner D.R., Briddon S.J., Wheatley M. Single molecule binding of a ligand to a G-protein-coupled receptor in real time using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, rendered possible by nano-encapsulation in styrene maleic acid lipid particles. Nanoscale. 2020;12:11518–11525. doi: 10.1039/d0nr01060j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Briddon S.J., Kilpatrick L.E., J.Hill S. Studying GPCR Pharmacology in Membrane Microdomains: fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy Comes of Age. Trends. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018;39 doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2017.11.004. 158-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Das S., Bhattacharyya D. Bromelain from Pineapple: its Stability and Therapeutic Potentials. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2012 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rani A., Venkatesu P. A distinct proof on interplay between trehalose and guanidinium chloride for the stability of stem bromelain. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:8863–8872. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b05766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhakuni K., Venkatesu P. Crowded milieu tuning the stability and activity of stem bromelain. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;109:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rani A., Venkatesu P. Insights into the interactions between enzyme and co-solvents: stability and activity of stem bromelain. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015;73:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Habib S., Khan M.A., Younus H. Thermal destabilization of stem bromelain by trehalose. Protein J. 2007;26:117–124. doi: 10.1007/s10930-006-9052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jha I., Bisht M., Venkatesu P. Does 1-Allyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride Act as a Biocompatible Solvent for Stem Bromelain? J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:5625–5633. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b03912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhakuni K., Venkatesu P. Does Macromolecular Crowding Compatible with Enzyme Stem Bromelain Structure and Stability? Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;131:527–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiran P., Jha I., Sindhu A., Venkatesu P., Bahadur I., Ebenso E.E. Experimental and Molecular Docking Studies in Understanding the Biomolecular Interactions between Stem Bromelain and Imidazolium- Based Ionic Liquids. J. Mol. Liq. 2020;297 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Das N., Khan T., Subba N., Sen P. Correlating Bromelain's activity with its structure and active-site dynamics and the medium's physical properties in a hydrated deep eutectic solvent. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021;23:9337–9346. doi: 10.1039/d1cp00046b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pavani P., Kumar K., Rani P. Venkatesu A., Lee M.J. Insight into Interactions between Enzyme and Biological Buffers: enhanced Thermal Stability of Stem Bromelain. J. Mol. Liq. 2020;322 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ritonja A., Rowan A.D., Buttle D.J., Rawlings N.D., Turk V., Barrett A.J. Stem bromelain: amino acid sequence and implications for weak binding of cystatin. FEBS Lett. 1989;247:419–424. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81383-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Husain S.S., Lowe G. The amino acid sequence around the active-site cysteine and histidine residues of stem bromelain. Biochem. J. 1970;117:341–346. doi: 10.1042/bj1170341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamphuis I.G., Drenth J., Baker E.N. Thiol proteases: comparative studies based on the high-resolution structures of papain and actinidin, and on amino acid sequence information for cathepsins B and H, and stem bromelain. J. Mol. Biol. 1985;182:317–329. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90348-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Böhm G., Muhr R., Jaenicke R. Quantitative Analysis of Protein Far UV Circular Dichroism Spectra by Neural Networks. Prot. Eng. Des. Sel. 1992;5:191–195. doi: 10.1093/protein/5.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sengupta B., Das N., Sen P. Monomerization and aggregation of β-lactoglobulin under adverse condition: a fluorescence correlation spectroscopic investigation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteomics. 2018;1866:316–326. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Das N., Sen P. Functional, and Dynamical Responses of a Protein in a Restricted Environment Imposed by Macromolecular Crowding. Biochemistry, 2018;57:6078–6089. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Das N., Sen P. Size-Dependent Macromolecular Crowding Effect on the Thermodynamics of Protein Unfolding Revealed at the Single Molecular Level. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;141:843–854. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Das N., Sen P. Shape Dependent Macromolecular Crowding on the Thermodynamics and Microsecond Conformational Dynamics of Protein Unfolding Revealed at the Single Molecular Level. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2020;124:5858–5871. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c03897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muller C.B., Loman A., Pacheco V., Koberling F., Willbold D., Richtering W., Enderlein J. Precise measurement of diffusion by multi-color dual-focus fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Europhys. Lett. 2008;83:46001. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naidum K.T., Prabhu P.N. Protein–surfactant interaction: sodium dodecyl sulfate induced unfolding of ribonuclease A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:14760–14767. doi: 10.1021/jp2062496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pauling L., Corey R.B., Branson H.R. The structure of proteins: two hydrogen-bonded helical configurations of the polypeptide chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1951;37:205–211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.37.4.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaman M., Zakariya S., Nusrat S., Khan M., Qadeer A., Ajmal M., Khan R. Surfactant-mediated amyloidogenesis behaviour of stem bromelain; a biophysical insight. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2016;35:1407–1419. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2016.1185040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sengupta B., Das N., Sen P. Elucidation of μs dynamics of domain-III of human serumalbumin duringthe chemical and thermal unfolding: fluorescence correlation spectroscopic investigation. Biophys. Chem. 2016;221:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sengupta B., Chaudhury A., Das N., Sen P. Single Molecular Level Investigation of Structure and Dynamics of Papain under Denaturation. Prot. Pept. Lett. 2017;24:1073–1081. doi: 10.2174/0929866524666170811145838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiao M., Zhou Y.L., Li H.T., Zhang D.L., Chen J., Liang Y. Structural and Functional Alterations of Two Multidomain Oxidoreductases Induced by Guanidine Hydrochloride. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2010;42:30–38. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmp107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahmad B., Shamim T.A., Haq S.K., Khan R.H. Identification and characterization of functional intermediates of stem bromelain during urea and guanidine hydrochloride unfolding. J. Biochem. 2007;141:251–259. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rasheedi S., Haq S.K., Khan R.H. Guanidine hydrochloride denaturation of glycosylated and deglycosylated stem bromelain. Biochemistry (moscow) 2003;68:1097–1100. doi: 10.1023/a:1026354527750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Povarova O.I., Kuznetsova I.M., Turoverov K.K. Differences in the pathways of proteins unfolding induced by urea and guanidine hydrochloride: molten globule state and aggregates. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:15035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arakawa T., Timasheff S.N. Protein stabilization and destabilization by guanidinium salts. Biochemistry. 1984;23:5924–5929. doi: 10.1021/bi00320a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mason P.E., Brady J.W., Neilson G.W., Dempsey C.E. The Interaction of Guanidinium Ions with a Model Peptide. Biophys. J. 2007;93:4–6. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.108290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neurath H., Greenstein J.P., Putnam F.W., Erickson J.A. The chemistry of protein denaturation. Chem. Rev. 1944;34:157–265. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mason P.E., Neilson G.W., Enderby J.E.M., Saboungi L., Dempsey C.E., MacKerrell Jr A.D., Brady J.W. The structure of aqueous guanidinium chloride solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:11462–11470. doi: 10.1021/ja040034x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Brien E.P., Dima R.I., Brooks B., Thirumalai D. Interactions between Hydrophobic and Ionic Solutes in Aqueous Guanidinium Chloride and Urea Solutions: lessons for Protein Denaturation Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7346–7353. doi: 10.1021/ja069232+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meuzelaar H., Panman M.R., Woutersen S. Guanidinium-induced denaturation by breaking of salt bridges. Angew. Chem. 2015;127:15470–15474. doi: 10.1002/anie.201508601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bosshard H.R., Marti D.N., Jelesarov I. Protein stabilization by salt bridges: concepts, experimental approaches, and clarification of some misunderstandings. J. Mol. Recog. 2004;17:1–16. doi: 10.1002/jmr.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Samanta N., Mahanta D.D., Mitra R.K. Collective Hydration Dynamics of Guanidinium Chloride Solutions and Its Possible Role in Protein Denaturation: a Terahertz Spectroscopic Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014;16:23308–23315. doi: 10.1039/c4cp03273j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cozzolino S., Balasco N., Vigorita M., Ruggiero A., Smaldone G., Del Vecchio P., Vitagliano L., Graziano G. Guanidinium Binding to Proteins: the Intriguing Effects on the D1 and D2 Domains of Thermotoga Maritima Arginine Binding Protein and a Comprehensive Analysis of the Protein Data Bank. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;163:375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.06.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zarrine-Afsar A. Protein Stabilization by Specific Binding of Guanidinium to a Functional Arginine-Binding Surface on an SH3 Domain. Protein Sci. 2006;15:162–170. doi: 10.1110/ps.051829106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dunbar J., Yennawar H.P., Banerjee S., Luo J., Farber G.K. The effect of denaturants on protein structure. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1272–1733. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhuyan Abani K. Protein Stabilization by Urea and Guanidine Hydrochloride. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13386–13394. doi: 10.1021/bi020371n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kumar R., Prabhu N.P., Yadaiah M., Bhuyan A.K. Protein Stiffening and Entropic Stabilization in the Subdenaturing Limit of Guanidine Hydrochloride. Biophys. J. 2004;87:2656–2662. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.044701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee J.C., Timasheff S.N. The stabilization of proteins by sucrose. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:7193–7201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.James S., McManus J.J. Thermal and Solution Stability of Lysozyme in the Presence of Sucrose, Glucose, and Trehalose. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:10182–10188. doi: 10.1021/jp303898g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shil S., Das N., Sengupta B., Sen P. Sucrose-Induced Stabilization of Domain-II and Overall Human Serum Albumin against Chemical and Thermal Denaturation. ACS Omega. 2018;3:16633–16642. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sampedro J.G., Uribe S. Trehalose-enzyme interactions result in structure stabilization and activity inhibition. The role of viscosity. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004;256:319–327. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000009878.21929.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carpenter J.F., Crowe J.H. An infrared spectroscopic study of the interactions of carbohydrates with dried proteins. Biochemistry. 1989;28:3916–3922. doi: 10.1021/bi00435a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Belton P.S., Gil A.M. IR and Raman spectroscopic studies of the interaction of trehalose with hen egg white lysozyme. Biopolymers. 1994;34:957–961. doi: 10.1002/bip.360340713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fedorov M.V., Goodman J.M., Nerukh D., Schumm S. Self-assembly of trehalose molecules on a lysozyme surface: the broken glass hypothesis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:2294–2299. doi: 10.1039/c0cp01705a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ajito S., Iwase H., Takata S.I., Hirai M. Sugar-Mediated Stabilization of Protein against Chemical or Thermal Denaturation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2018;122:8685–8697. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b06572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou H., Rivas G., Minton A. Macromolecular Crowding and Confinement: biochemical, Biophysical, and Potential Physiological Consequences. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008;37:375–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cozzolino S., Graziano G. The Magnitude of Macromolecular Crowding Caused by Dextran and Ficoll for the Conformational Stability of Globular Proteins. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;322 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hirai M., Ajito S., Sato S., Ohta N., Igarash N., Shimizu N. Preferential Intercalation of Human Amyloid-β Peptide into Interbilayer Region of Lipid-Raft Membrane in Macromolecular Crowding Environment. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2018;122:9482–9489. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b08006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Samanta N., Mahanta D.D., Patra A., Mitra R.K. Soft Interaction and Excluded Volume Effect Compete as Polyethylene Glycols Modulate Enzyme Activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018;118:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Silverstein T., Slade K. Effects of Macromolecular Crowding on Biochemical Systems. J. Chem. Educ. 2019;96:2476–2487. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sharp K.A. Analysis of the size dependence of macromolecular crowding shows that smaller is better. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015;112:7990–7995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505396112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gnutt D., Ebbinghaus S. The macromolecular crowding effect - from in vitro into the cell. Biol. Chem. 2016;397:37–44. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2015-0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Homchaudhuri L., Sarma N., Swaminathan R. Effect of crowding by dextrans and ficolls on the rate of alkaline phosphatase-catalyzed hydrolysis: a size-dependent investigation. Biopolymers. 2006;83:477–486. doi: 10.1002/bip.20578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Daniel R.M., Dunn R.V., Finney J.L., Smith J.C. The role of dynamics in enzyme activity. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2003;32:69–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.142445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prabhu N., Sharp K. Protein−Solvent Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:1616–1623. doi: 10.1021/cr040437f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.