Highlights

-

•

Regional FLAIR textures can classify vascular and non-vascular cognitive impairment.

-

•

All regional FLAIR biomarkers are correlated to mean diffusivity (MD) in dMRI.

-

•

All regional FLAIR biomarkers except WM tracts are strongly correlated to WML load.

-

•

Penumbra and WM tract texture is discriminative of scVMCI and Mixed groups.

-

•

WM degeneration in specific regions may be more important than global WML load.

Keywords: Subcortical vascular disease, Alzheimer’s disease, FLAIR, Neurodegeneration, Regional biomarkers, Texture analysis

Abstract

Interactions between subcortical vascular disease and dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are unclear, and clinical overlap between the diseases makes diagnosis challenging. Existing studies have shown regional microstructural changes specific to each disease, and that textures in fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI images may characterize abnormalities in tissue microstructure. This work aims to investigate regional FLAIR biomarkers that can differentiate dementia cohorts with and without subcortical vascular disease. FLAIR and diffusion MRI (dMRI) volumes were obtained in 65 mild cognitive impairment (MCI), 21 AD, 44 subcortical vascular MCI (scVMCI), 22 Mixed etiology, and 48 healthy elderly patients. FLAIR texture and intensity biomarkers were extracted from the normal appearing brain matter (NABM), WML penumbra, blood supply territory (BST), and white matter tract regions of each patient. All FLAIR biomarkers were correlated to dMRI metrics in each region and global WML load, and biomarker means between groups were compared using ANOVA. Binary classifications were performed using Random Forest classifiers to investigate the predictive nature of the regional biomarkers, and SHAP feature analysis was performed to further investigate optimal regions of interest for differentiating disease groups. The regional FLAIR biomarkers were strongly correlated to MD, while all biomarker regions but white matter tracts were strongly correlated to WML burden. Classification between Mixed disease and healthy, AD, and scVMCI patients yielded accuracies of 97%, 81%, and 72% respectively using WM tract biomarkers. Classification between scVMCI and healthy, MCI, and AD patients yielded accuracies of 89%, 84%, and 79% respectively using penumbra biomarkers. Only the classification between AD and healthy patients had optimal results using NABM biomarkers. This work presents novel regional FLAIR biomarkers that may quantify white matter degeneration related to subcortical vascular disease, and which indicate that investigating degeneration in specific regions may be more important than assessing global WML burden in vascular disease groups.

1. Introduction

Vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) refers to a broad group of cognitive disorders caused by vascular lesions and cerebrovascular pathology (Barbay et al., 2017). Subjects with VCI may progress to vascular dementia (VaD), one of the most common types of dementia, second only to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Barbay et al., 2017). There is increasing prevalence of AD and VaD in aging populations, while the mechanisms of interactions of the two diseases remain to be fully elucidated (Attems and Jellinger, 2014). There is considerable overlap in clinical symptoms and neuroimaging features between the two diseases which makes differentiating one from another challenging (Jiang et al., 2020). Accurate diagnosis of AD and VaD is crucial in identifying the best treatment options for patients (Castellazzi et al., 2020) and routine diagnostic MRI biomarkers could be clinically useful in this regard. Imaging biomarkers from structural MRI (sMRI) will be an important first step for multi-modality analysis. Though existing modalities such as PET imaging, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and more recently plasma biomarkers, are becoming more available, amyloid PET remains expensive and not widely available (Janelidze et al., 2020).

Existing studies have investigated different imaging modalities, structural regions of interest and machine learning models to classify VaD subjects and found tract-based features from diffusion MRI (dMRI) and functional MRI (fMRI) modalities classified AD and VaD subjects with 85% accuracy using an ANFIS model (Castellazzi et al., 2020). Zarei et al. used tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) to study changes of dMRI metrics in AD, VaD, and controls (Zarei et al., 2009). They found a reduction in FA in the forceps minor was the most significant difference between AD and VaD subjects. Combining FA measures from the forceps minor with the Fazekas score resulted in the optimal discriminant model performance with 87.5% accuracy. In the study by Zheng et al., the authors used volumetric features of brain substructures derived from sMRI to yield 84% accuracy in classifying AD and VaD subjects using a SVM (Zheng et al. 2019). The hippocampus volume was found to be the most important feature for differential diagnosis. In Diciotti et al., volumetric measurements of 148 cortical and 55 subcortical regions, along with dMRI metrics in the white matter (WM) tissue, were used as features to classify between healthy controls and VaD patients (Diciotti et al., 2015). Model performance increased with the number of multi-modal features, with the highest area-under-the curve (AUC) value of 96.8% using a functional tree model. In Liu et al., the authors were able to classify controls and Subcortical Ischemic Vascular Cognitive Impairment No Dementia (SIVCIND) patients with 94.8% accuracy using structural radiomics features derived from T1-weighted images and a Random Forest classifier (Liu et al., 2022). Structural regions discriminating between controls and SIVCIND were found to be the right amygdala, left caudate nucleus, left putamen, and left thalamus. Given that the studies investigated different regions of interest using multiple modalities, it is difficult to make solid conclusions on the differences in regional manifestations between VCI and AD. Additionally, though the etiology of SIVCIND is known to be associated with vasogenic edema and venous collagenosis (Black et al., 2009), the interactions between subcortical vascular disease and dementia due to AD remain unclear.

Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) is emerging as a beneficial MRI sequence for characterizing WM disease. The FLAIR sequence suppresses the high signal from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in T2 weighted images, thus highlighting WM disease and white matter lesions (WML). WML are considered to be of vascular origin and associated with vascular risk factors, cerebral small vessel disease, blood-brain barrier dysfunction, and ischemic pathology (de Groot et al., 2013). Maillard et al. showed FLAIR intensity in the WML penumbra (region surrounding WML) is a predictor of WML growth, and postulated FLAIR MRI may provide complementary information to dMRI (Maillard et al., 2013). Further analysis of FLAIR from normal-appearing brain matter (NABM) in Bahsoun et al. found several novel biomarkers based on intensity, texture and volume, and mean diffusivity (MD) from dMRI, were correlated with cognitive decline (Bahsoun et al., 2022). The authors postulated that FLAIR texture biomarkers were measuring abnormalities in tissue microstructure. Recent studies have used FLAIR to train deep learning models in classifying subtypes of vascular disease. Wang et al. achieved 96.9% accuracy in classifying VaD, VMCI, no cognitive impairment (NCI) with subcortical ischemic vascular disease (SIVD) and control subjects using a 3D CNN model (Wang et al., 2019). Chen et al. achieved 93.8% accuracy in classifying amnestic mild cognitive impairment (a-MCI), nonamnestic MCI (na-MCI), and NCI subtypes of subcortical VMCI using a 3D ResNet (Chen et al., 2020).

In this work, to study regional differences across AD and vascular disease, a large dementia cohort is analyzed by extracting regional biomarkers from FLAIR, which includes intensity and texture features from the normal appearing brain matter (NABM), WM tracts, WML penumbra and blood supply territories (BST). We hypothesize texture and intensity biomarkers from FLAIR contain information related to microstructural tissue damage, and that specific regions will demonstrate differences in dementia cohorts with and without vascular contributions.

2. Materials & methods

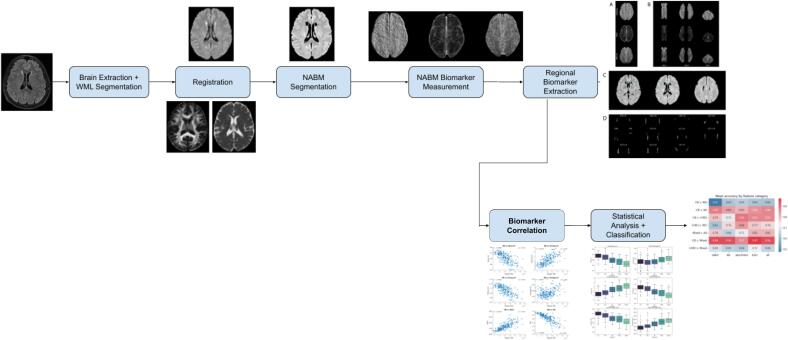

The following subsections will describe the cohort and methods used. A summary of the proposed pipeline can be found in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Full pipeline of proposed methodology.

2.1. Data

The dataset used is from the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA) (Mohaddes et al., 2018), a pan-Canadian cohort study across the common dementias, including cognitive impairment due to small vessel disease (Wardlaw et al., 2013). Subjects with MCI, mild dementia due to AD, subcortical vascular MCI (scVMCI), and Mixed etiology with a vascular component, along with healthy controls (cognitively-intact elderly (CIE)) were recruited across Canada. Cognitive tests for determining diagnosis included global Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale, logical memory, CERAD word list recall, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and Lawton-Brody IADL scale. CIE criteria included normal performance on standardized cognitive tests. MCI subjects had to meet National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association (NIAAA) clinical criteria for MCI due to AD (Albert et al., 2011). scVMCI subjects met the criteria for MCI, while also demonstrating extensive subcortical cerebrovascular disease on the Age-Related White Matter Change (ARWMC) scale or two or more hemispheric subcortical lacunar infarcts (Smith et al., 2021). Patients with history of symptomatic stroke were excluded. AD subjects had to meet the NIA-AA clinical criteria for AD (McKhann et al., 2011) and non-AD causes of dementia were ruled out by standardized work up for dementia. The Mixed group were defined using the NIA-AA clinical criteria for Mixed Etiology dementia (McKhann et al., 2011) which included subjects at the intersection of the AD and scVMCI diagnostic groups. In total, there are 200 subjects used in this analysis (65 MCI, 21 AD, 44 scVMCI, 22 Mixed, 48 CIE) with both dMRI and FLAIR volumes. Imaging data was acquired using SIEMENS, GE, and Philips scanners, varying by acquisition centre. A summary of the acquisition parameters and subjects is presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

FLAIR and dMRI acquisition parameters.

| Modality | TR (ms) | TE (ms) | TI (ms) | Pixel Spacing (mm) | Slice Thickness (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLAIR | 9000–9840 | 120–146 | 2250–2500 | 0.9375 | 3 |

| dMRI | 6900–13000 | 64–101 | – | 0.9375–2.6506 | 2–3 |

Table 2.

Summary of diagnostic groups with available dMRI volumes.

| Group | Patients | Sex (F/M) | Mean age | Mean WML burden (mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIE | 48 | 40/8 | 69.65 | 8.99 |

| MCI | 65 | 29/36 | 71.86 | 10.96 |

| AD | 21 | 6/15 | 75.70 | 12.81 |

| scVMCI | 44 | 17/27 | 77.36 | 45.62 |

| Mixed | 22 | 12/10 | 78.82 | 30.26 |

2.2. Atlases

Atlases used in this work include the Brainder FLAIR atlas (Winkler et al., n.d.), blood supply territory atlases, and white matter tract atlases from FSL’s XTRACT library (Warrington et al., 2020). The original Brainder atlas with 0.7 mm × 0.7 mm × 0.7 mm resolution was resampled to 0.8594 mm × 0.8594 mm × 3.5 mm, as this resolution is most common in the dataset. This was done to prevent ghosting between slices when registering native FLAIR volumes to the atlas space. The resulting FLAIR atlas used for all subsequent registrations has final dimensions of 256×256×55. The BST atlases used in this work were delineated with the same FLAIR atlas, using the work in (Tatu et al., 1998) as a main reference. Delineations of the vascular territories were performed by a trained graduate student (A.G.) and verified by neuroradiology experts (P.M. & A.M.). Intra-rater variability was measured using the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) and the results can be seen in Appendix Table B8. The major territories included in this work are regions supplied by the anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries (ACA, MCA, and PCA). The FSL WM tract atlases were acquired in MNI152 standard space with a resolution of 1 mm × 1 mm × 1 mm and dimensions of 182×218×182. A total of 22 tracts were used in this work, including the left and right anterior thalamic radiations (ATR), left and right dorsal and posterior cingulum bundles (CBD and CBP), left and right corticospinal tracts (CST), forceps major and minor (FMA and FMI), left and right inferior fronto-occipital fasciculi (IFO), left and right inferior longitudinal fasciculi (ILF), three major components of the left and right superior longitudinal fasciculi (SLF1, SLF2, SLF3), and the left and right uncinate fasciculi (UF).

2.3. Image analysis

FLAIR volumes were intensity-normalized using a method developed in Reiche et al. (Reiche et al., 2019) to remove variations in intensities between scanners and centres. Brain extraction was then performed using a pre-trained MultiResUnet model (DiGregorio et al., 2021) and WML masks were generated from the volumes using a pre-trained SC U-Net model (Khademi et al., 2021). The NABM was extracted using the intensity standardized volumes by segmenting WML using the masks and thresholding CSF as in Bahsoun et al. (Bahsoun et al., 2022). To spatially normalize the data, FLAIR volumes were registered to the FLAIR Brainder atlas using Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs) symmetric normalization (SyN) transform (Avants et al., 2011), which applies affine and deformable transformations with a mutual information loss function. All segmentation masks are registered using this transformation. Tractoflow (Theaud et al., 2020) was used to extract MD and fractional anisotropy (FA) from dMRI data. To align dMRI and FLAIR data, each subject’s native FA map was registered to their corresponding native FLAIR volume, then transformed to the FLAIR atlas space using the ANTs SyN transform from the first registration (Appendix Fig. A6, top). Native MD maps were registered directly to the Brainder atlas space using a multi-metric loss function method, which drives the registration using both a Demons and a mutual information loss metric. This resulted in better visual alignments in the ventricular areas and higher mutual information scores compared to the two-step ANTs SyN registration for the FA maps. To extract subject specific WM tracts, the FA volumes are used since they provide large contrasts for the WM tracts (Meoded et al., 2017). K-means clustering was applied to FA volumes and the two highest intensity clusters were extracted as a preliminary segmentation of all tracts. Segmented tracts were registered using ANTs SyN to the whole MNI tract atlas which contains individual FSL tract atlases (Appendix Fig. A6, bottom). To separate the subject’s tracts, the individual tract atlases were transformed back into the subject’s original FA space. All tracts were then registered from FA space to Brainder space using the patient’s corresponding two-step ANTs SyN registrations, binarized, and post-processed to be used as regional masks for segmenting FLAIR texture volumes. Post-processing steps included erosion operations to clean tract masks by removing outlying voxels and noise. We opted to use this method instead of AFQ and TBSS since AFQ can only analyze the central portion of the WM tracts (Qiu et al., 2021) and TBSS can only be used to analyze the tract skeletons with highest FA, which excludes large parts of the tracts (Roine et al., 2015). Lastly, we wanted to account for individualized structural anatomy such as enlarged ventricles rather than using the same atlas for every patient. Qiu et al. used a similar method of inverse registering the tract atlases to the individual space (Qiu et al., 2021).

2.4. FLAIR regional biomarker extraction

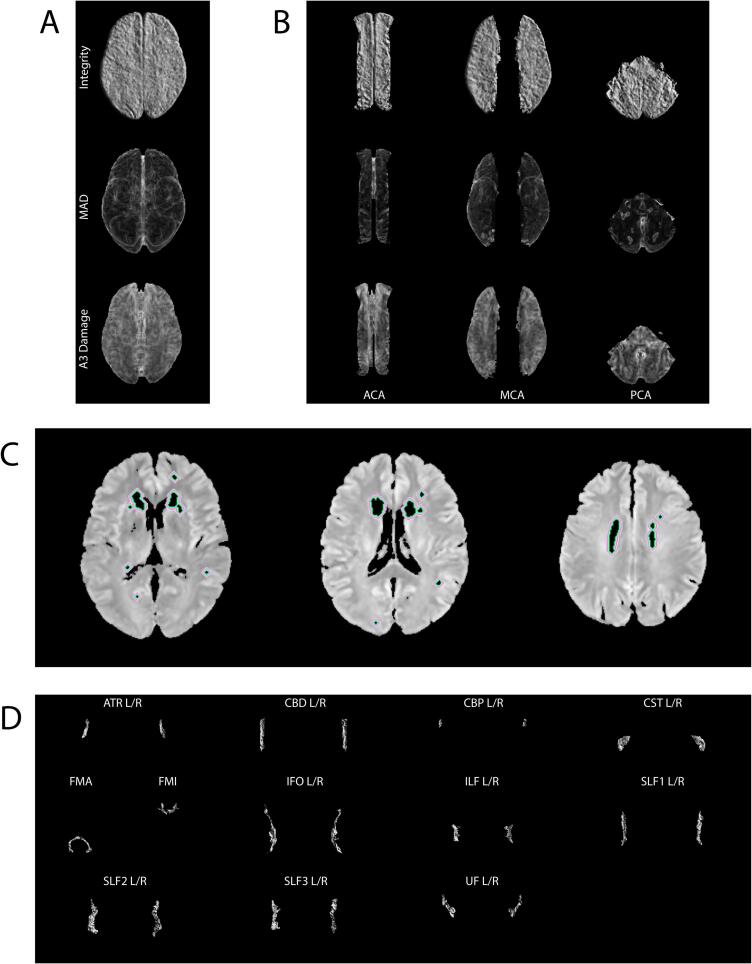

Four categories of texture biomarkers were investigated in this work, corresponding to the following regions of interest: normal-appearing brain matter (NABM), white matter lesion penumbra, blood supply territories (BST), and white matter tracts. A summary of all regions and biomarkers is presented in Appendix Table B9. Visuals of sample texture biomarker maps in each region of interest are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Visuals of each region of interest in this work. (A) Mean NABM texture maps, (B) Mean BST regional texture maps, (C) Penumbra regions P1 (green) to P5 (light pink) delineated on original FLAIR MRI slices, (D) Mean tract integrity maps. Note only supratentorial regions are analysed in this work.

2.4.1. NABM biomarkers

The NABM region is composed of normal appearing white and gray matter, and is found by thresholding the FLAIR volumes to remove CSF and masking out WML using the WML segmentation masks (Bahsoun et al., 2022). Texture biomarkers extracted from the NABM, called macrostructural damage (MAD) and microstructural integrity (MII), were found to be associated with cognition in Bahsoun et al. (Bahsoun et al., 2022). In addition to these two measures, an additional texture measure called A3 Damage based on the wavelet transform (Khademi and Krishnan, 2007, Khademi and Krishnan, 2008) is added, along with three wavelet statistical features. The textures were computed per slice, which were then voxel-wise averaged across slices to yield a mean feature map for each patient (Fig. 2A). The median of the mean feature map was taken as the texture biomarker.

Macrostructural damage (MAD): The MAD biomarker was computed using the Mantel statistic (Khademi et al., 2009), which quantifies the spatial correlation between pixels (Eq. (1). It detects whether pixels that are in proximity to each other have similar intensity values. Therefore, MAD is large in regions with rapidly changing intensities such as edges and more textured tissue regions. As such, it is measuring structural variations in the tissue. Higher MAD values were found to be associated with worsening cognition (Bahsoun et al., Jan. 2022). As shown in Fig. 2A (MAD), in regions with texture and edges, there are higher intensities in the texture map (indicating less homogeneity).

| (1) |

where Wij is the distance between pixels si and sj and Uij is the absolute difference of their intensities.

Microstructural integrity (MII): The MII biomarker was computed based on local binary patterns (LBP) to detect repeating texture patterns. Differences in intensities within a 3x3 neighbourhood are compared to the central pixel (Eq. (2), thus defining a local texture pattern. A higher number of similar repeating structured patterns in the tissue (higher LBP values), indicate more tissue integrity associated with better cognition (Bahsoun et al., Jan. 2022). The average LBP map shows which regions have rapidly changing intensities (Fig. 2A – MII), with similar values indicating similar intensity patterns.

| (2) |

where P is the number of neighbours, Ip is the intensity of the neighbouring pixel, and Ic is the intensity of the central pixel.

Wavelet Transform A3 Biomarkers: The Stationary Wavelet Transform (SWT) is used to analyze localized spatial-frequency information from the third-level Haar wavelet decomposed approximation (A3) images (Fayaz et al., 2021). Statistical features of mean, energy, and entropy of the A3 coefficients were extracted from every slice and averaged to obtain a final metric for each patient volume. The A3 mean describes the homogeneity of the tissue, while entropy measures heterogeneity (rapid intensity fluctuations). Unlike the discrete wavelet transform, the SWT decomposition images remain the same size as the original images, allowing us to compute an A3 Damage marker. This was done by first computing the Mantel’s statistic (Eq. (1) of the smoothed A3 volumes, which is Otsu thresholded to remove the high values resulting from large edges, to detect small intensity variations in underlying microstructures (Bahsoun et al., 2022). The wavelet features are extracted from the low frequency bands and the midline artifacts (large edge) are minimized (see Fig. 2A – A3 Damage). The mean texture representation is overall more smooth, looking for more subtle variations in texture.

2.4.2. WML penumbra

Recent studies have shown FLAIR intensity in penumbra regions surrounding WML demonstrate abnormalities quantified by decreased MD and increased FA values (Maillard et al., 2013, Nasrallah et al., 2019). Additionally, Promjunyakul et al. found cerebral blood flow in areas surrounding WML was significantly lower than in normal-appearing white matter (Promjunyakul et al., 2015). This coincides with the findings in Rowley et al., which suggest the penumbra of stroke infarcts can be detected by combining multiple vascular features in FLAIR and dMRI images, including site of vessel occlusion, extent of perfusion, and infarct parenchyma (Rowley, 2001). Therefore, penumbra regions could potentially carry signs of microstructural tissue alterations related to vascular disease. Five penumbra regions were found by dilating white matter lesion masks (see Fig. 2C for extracted penumbra regions). A 1-voxel dilation, corresponding to 0.86 mm, was performed five times and the previous dilated masks were removed from the centers of each dilation to obtain the five regions. The masks were then used to segment the regions of interest from the NABM texture volumes. The biomarkers extracted for the penumbra region include A3 Mean, MAD, MII, and median FLAIR intensity from each of the 5 penumbra regions.

2.4.3. Blood supply territories

The blood supply territories (BST) are regions that are directly vascularized by the cerebral arteries (Konan et al., 2022). The three major BSTs investigated in this work are the ACA, MCA, and PCA. These regions were chosen to examine relationships between brain tissue damage and the major cerebral blood supplies. The Brainder BST atlas was used to segment each territory from the volumes. The texture volumes for each territory were computed as in Section 2.4.1 and voxel-wise averaged, resulting in a mean texture image for each BST region (Fig. 2B). Features extracted from BST regions include MII, MAD, A3 Damage, and A3 Mean.

2.4.4. White matter tracts

White matter (WM) tracts are tissue fibers that provide connectivity between different regions of the brain. They are found mainly at the distal borders between blood supply territories and are prone to vascular insufficiency (Iadecola, 2013). They could therefore be useful in assessing microstructural WM damage in patients with vascular pathology. Additionally, numerous studies have found differences in strategic WM tracts between healthy, AD, and vascular disease patients (Castellazzi et al., 2020, Zarei et al., 2009, Yoshita et al., 2006, Jiang et al., 2018, Duering et al., 2011). The segmented tracts of each patient from the pipeline in Fig. 6 were used to segment tract regions from the FLAIR texture volumes. Each tract texture region was then voxel-wise averaged, resulting in mean texture images for each tract region (Fig. 2D). The features extracted from the tract regions are MII, MAD, A3 Damage, and A3 Mean.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Trends in regional biomarkers between diagnostic groups are explored using parametric tests. A one-way ANOVA was performed on features to evaluate significance between diagnostic group means. Two-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc tests were performed to analyze the effect of diagnostic groups and regions on FLAIR biomarker features for penumbra, BST, and tract biomarkers. Pearson’s correlation and t-tests were used to evaluate strength of the relationship between FLAIR biomarkers and dMRI metrics as well as with WML load.

Classification experiments were implemented to further explore the predictive nature of FLAIR regional biomarkers between diagnostic groups. A Random Forest classifier was used for all experiments and five-fold cross validation to test on all the data. Eight experiments were performed, one for each binary classification: CIE vs. MCI, CIE vs. AD, CIE vs. scVMCI, CIE vs. Mixed, AD vs. Mixed, MCI vs. scVMCI, AD vs. scVMCI, and Mixed vs. scVMCI. To analyze which regional biomarkers can predict diagnosis, every classification task was performed using each category of regional biomarkers individually (NABM, BST, penumbra and WM tracts) and once with all the features combined. For each classification task, the biomarker category that resulted in the highest classification accuracy (optimal models) for that task, is analyzed further.

From the optimal models, the top six most important features (sub-regions and biomarkers) from each biomarker category are found using Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) to investigate the highest-contributing sub-regions to each classification. Six was chosen to match the number of NABM biomarkers. We use SHAP since in ensemble decision trees, gain is generally used to assess feature importance but has proven to be inconsistent (Nohara et al., 2022). As an alternative, Lundberg et al. proposed the Shapley (SHAP) value as a unified measure of feature importance which can be used across different types of models (Lundberg and Lee, 2017). The SHAP value is computed as the average marginal contribution of a feature value across all possible combinations. In other words, the SHAP importance of a feature f is the difference between the prediction of the model with and without feature f computed in every possible order and combination of features. As a result, SHAP values are in units of log-odds, such that they represent the likelihood of a feature value belonging to the positive class in a binary classification. SHAP dependence plots, which demonstrate the relationship between feature values and their effect on the outcome as measured in SHAP values (Nohara et al., 2022), were used to determine biomarker thresholds in each classification as proof-of-concept that the proposed FLAIR biomarker panel can be clinically useful for stratifying patients into diagnostic groups. A regression curve was fit to the data distribution in the dependence plots and the crossing point of the fitted curve at y = 0 was determined to be the biomarker threshold between the two classes. The y = 0 line is significant in the SHAP dependence plot because any data points with SHAP values above the line indicate a higher likelihood of those points belonging to the positive class and vice versa.

3. Results

All biomarkers are extracted from the cohort to perform analysis. Biomarker correlation is completed between dMRI metrics and WML load and corresponding FLAIR biomarkers, followed by statistical analysis, classification and feature importance analysis. All correlation results for NABM and tract region biomarkers are shown in Table 3, Table 4.

Table 3.

Correlation of FLAIR NABM texture biomarkers vs. dMRI biomarkers and WML lesion load. Pearson's correlation coefficients, p-values. Underlined indicates strong correlations, bold indicates significant p-values.

| Biomarkers | MD |

FA |

WML Load |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | p | R | p | R | p | |

| Mean A3 | −0.69 | <0.001 | 0.26 | <0.001 | −0.70 | <0.001 |

| Entropy A3 | 0.69 | <0.001 | −0.26 | <0.001 | 0.67 | <0.001 |

| Energy A3 | −0.70 | <0.001 | 0.26 | <0.001 | −0.67 | <0.001 |

| Damage A3 | 0.35 | <0.001 | −0.03 | 0.68 | 0.44 | <0.001 |

| MAD | 0.74 | <0.001 | −0.22 | <0.01 | 0.74 | <0.001 |

| Integrity | −0.79 | <0.001 | 0.27 | <0.001 | −0.68 | <0.001 |

Table 4.

Correlation of WM tract FLAIR texture biomarkers vs. dMRI biomarkers and WML lesion load. Pearson's correlation coefficients, p-values. Underlined indicates strong correlations, bold indicates significant p-values.

| Biomarkers | MD |

FA |

WML Load |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | p | R | p | R | p | |

| Mean A3 | −0.51 | <0.001 | −0.04 | <0.01 | −0.28 | <0.001 |

| MAD | 0.43 | <0.001 | −0.005 | 0.68 | 0.26 | <0.001 |

| Integrity | 0.21 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.28 | −0.17 | <0.001 |

| Damage A3 | 0.47 | <0.001 | 0.15 | <0.001 | 0.22 | <0.001 |

3.1. Correlation between FLAIR and dMRI biomarkers

FLAIR biomarkers were correlated to the corresponding dMRI MD and FA metrics (Appendix Figs. A7 – A10). All NABM biomarkers (Table 3) were significantly (p < 0.001) correlated to MD, with MII having the highest Pearson’s R coefficient of −0.79, followed by MAD. The A3 statistical features also demonstrated strong correlations with MD with R values of −0.69, 0.69, and −0.70 for mean, entropy, and energy respectively. A3 Damage demonstrated a moderate but significant correlation with MD. All correlations with FA were weak but significant except for A3 Damage, which did not demonstrate significant correlation with FA. MAD, A3 Entropy, A3 Damage – were found to have positive associations with MD (“damage” biomarkers), while MII, A3 Mean, A3 Energy – were negatively correlated to MD (“integrity” markers), indicating increased water diffusion is related to higher damage and lower integrity in the tissue. To investigate other regional biomarkers, correlation analysis was performed for features from the penumbra, WM tract, and BST regions and sub-regions. Similar trends were found. The BST regions demonstrated strong significant correlations with MD while the penumbra regions demonstrated moderate significant correlations with MD (Appendix Tables B10 – B13). The tract region biomarkers (Table 4) demonstrated moderate to strong correlations to MD, and all regions showed weak correlations with FA.

3.2. Correlation between FLAIR biomarkers and WML load

The FLAIR biomarkers were also correlated to global WML load. Correlation trends for NABM and tract region biomarkers are shown in Appendix Figs. A11 – A14. All NABM biomarkers (Table 3) were significantly (p > 0.001) correlated to WML volume. MAD and A3 Mean yielded the highest Pearson’s coefficient when correlated with WML volume of 0.74 and −0.70 respectively. A3 Damage also demonstrated a moderate but significant correlation with WML volume. MAD, A3 Damage, and A3 Entropy were found to have positive associations, while MII, A3 Mean, and A3 Energy were negatively associated with WML volume, indicating the NABM biomarkers are measuring increased damage and decreased integrity with higher lesion loads. Similar trends and strong significant correlations were seen in the penumbra and BST region biomarkers (Appendix Tables B14 and B15). Interestingly, weak correlations with WML load were seen in the tract texture biomarkers (Table 4). A3 Mean and MII yielded the highest and lowest Pearson’s coefficients of −0.28 and −0.17 respectively, which suggest the texture biomarkers in the tract regions may be measuring microstructural tissue abnormalities unrelated to global WML burden.

3.3. ANOVA and post-hoc tests

Trends of increasing damage biomarkers and decreasing integrity biomarkers can be seen in the order of CIE, MCI, AD, scVMCI, and Mixed, as shown by Appendix Figs. A15 – A20. One and two-way ANOVA along with Tukey post-hoc tests were performed to investigate differences in biomarker means between diagnostic groups and sub-regions as well as to analyze interaction effects of Diagnosis*Subregion. A summary of the results is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results from one- and two-way ANOVAs. Effect size is measured as η2 values. Underlined values indicate large effect sizes, italicized values indicate medium to large effect sizes, and bolded p-values indicate statistical significance.

| Region | Biomarkers | Source | Effect size (η2) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NABM | MAD MII A3 Energy A3 Entropy A3 Mean A3 Damage |

Diagnosis Diagnosis Diagnosis Diagnosis Diagnosis Diagnosis |

0.382 0.385 0.367 0.364 0.382 0.14 |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 |

| Penumbra | MAD MII Intensity A3 Mean |

Diagnosis*Subregion Diagnosis*Subregion Diagnosis*Subregion Diagnosis*Subregion |

0.133 0.082 0.037 0.007 |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.806 |

| BST | MAD MII A3 Mean A3 Damage |

Diagnosis*Subregion Diagnosis*Subregion Diagnosis*Subregion Diagnosis*Subregion |

0.025 0.015 0.011 0.047 |

0.004 0.09 0.298 <0.001 |

| WM Tracts | MAD MII A3 Mean A3 Damage |

Diagnosis*Subregion Diagnosis*Subregion Diagnosis*Subregion Diagnosis*Subregion |

0.037 0.103 0.076 0.093 |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 |

For NABM biomarkers, all features demonstrated significant differences (p < 0.001) in diagnostic group means with large effect sizes (η2 >0.14), indicating that the biomarkers have a strong relationship to the diagnostic label. Tukey post-hoc tests showed A3 Entropy and A3 Energy had significant differences in all diagnostic group pairings and comparisons. A3 Mean demonstrated significant differences in all pairings except between AD/scVMCI and scVMCI/Mixed, A3 Damage demonstrated significant differences in all pairings including a vascular group, MII demonstrated significant differences in all pairings except between AD/scVMCI, and MAD demonstrated significant differences in all pairings except between scVMCI/Mixed.

The main effects of Diagnosis and Subregion for the BST biomarkers demonstrated significant p-values (p < 0.001) for all biomarkers, while significant interactions between Diagnosis and Subregion were found in the MAD (p < 0.01) and A3 Damage (p < 0.001) biomarkers. In the penumbra region, the Diagnosis main effect demonstrated significant p-values (p < 0.001) in all biomarkers except MAD, while Subregions demonstrated a significant main effect (p < 0.001) for all biomarkers. All biomarkers except A3 Mean demonstrated significant interactions (p < 0.001). For the tract region, all main and interaction effects in all biomarkers demonstrated significant p-values (p < 0.001). Additional ANOVA tables for the main effects are shown in Appendix Tables B16 – B18.

Majority of the biomarkers in each region demonstrated statistically significant main (Diagnosis, Subregion) and interaction (Diagnosis*Subregion) effects, indicating regional biomarkers may be effective in classifying diagnostic groups and could be used to potentially uncover regional pathological mechanisms specific to each diagnostic group.

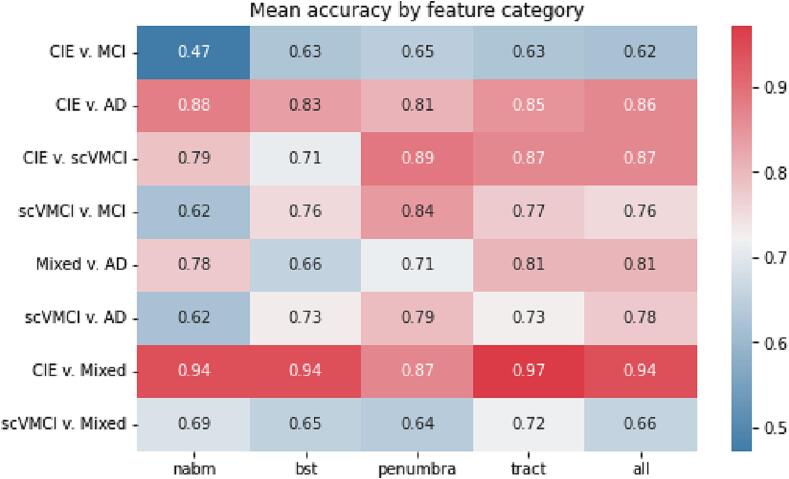

3.4. Classification and SHAP feature importance

Binary classification was performed using a Random Forest classifier and 5-fold cross-validation. The mean accuracies from all 5 folds for each classification task are shown in Fig. 3. The models constructed from feature categories that performed the best for a given classification task were retained for further analysis. Results are shown in Table 6, which lists the highest mean accuracies and area-under-the-curve (AUCs) of the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) achieved by a particular feature category for each classification task. The accuracy metric is the percentage of correctly predicted samples over the total number of samples. Though commonly used and intuitive, accuracy is known to be biased when extreme sample size imbalance is present in the dataset. To compliment accuracy, the AUC (area under the ROC curve) which plots the true positive rates against the false positive rates of the model at different classification thresholds is also examined. AUC values describe model performance based on its rate of correct or incorrect classifications. An AUC of 1 describes a perfect classifier, while a model with an AUC of 0.5 is not better than a random guess. Though there are no extreme data imbalances in this work, both accuracy and AUC are reported to fully describe model performances.

Fig. 3.

Mean classification accuracies by feature category.

Table 6.

Best evaluation metrics for each binary classification.

| Groups | Optimal feature category | Accuracy | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIE vs. MCI | Penumbra | 0.645 | 0.687 |

| CIE vs. AD | NABM | 0.879 | 0.919 |

| CIE vs. scVMCI | Penumbra | 0.888 | 0.957 |

| CIE vs. Mixed | Tract | 0.971 | 0.969 |

| Mixed vs. AD | Tract | 0.805 | 0.830 |

| MCI vs. scVMCI | Penumbra | 0.841 | 0.890 |

| AD vs. scVMCI | Penumbra | 0.793 | 0.885 |

| Mixed vs. scVMCI | Tract | 0.718 | 0.596 |

The CIE vs. Mixed classification performed the best overall with the highest accuracy and AUC of 97% using the tract features. This was followed by CIE vs. scVMCI and CIE vs. AD classifications with mean accuracies of 89% and 88% using penumbra and NABM features respectively. The worst performing classification results were for the CIE vs. MCI task, with a highest mean accuracy of 65% using penumbra features, followed by Mixed vs. scVMCI with mean accuracy of 72% using tract features. However, the Mixed vs. scVMCI classification yielded a low AUC value of 0.59 while all other tasks had AUCs higher than their respective accuracies. Mixed vs. AD classification yielded an accuracy of 81% using the tract features. MCI and AD vs. scVMCI classifications yielded accuracies of 84% and 79% respectively using penumbra features. Furthermore, it was found that all classifications involving the Mixed group yielded highest performance using the tract biomarkers, while all classifications involving the scVMCI and MCI groups performed best using the penumbra biomarkers. The CIE vs. AD classification was the only task that demonstrated best performance using NABM biomarkers. The same experiments were also performed using standard dMRI (mean FA and MD) metrics extracted from each sub-region (Appendix Table B19). The proposed FLAIR biomarkers far outperformed the dMRI metrics in all classification tasks.

Feature importance was analyzed using the SHAP method. The six most important features for each classification task are shown in Table 7, while rankings of all features can be found in Appendix Fig. A21. In the CIE vs. MCI classification, major contributions were found from outer penumbra regions (regions further from WML, i.e. P2 to P5), where the likelihood of MCI classification increases with larger intensity and MAD values and lower integrity values. The CIE vs. scVMCI and MCI vs. scVMCI classifications were found to have similar important features with the exception of increased P1 intensity contributing to a larger likelihood of scVMCI classification in the latter experiment. It was also found in these classifications along with AD vs. scVMCI that all the P1 biomarkers followed expected trends, i.e. higher likelihood of scVMCI with higher damage and lower integrity values, while all the biomarkers of the outer penumbra regions demonstrated the opposite.

Table 7.

Top 6 important features selected by SHAP analysis for each classification task. The positive class in each task is italicized. Arrows indicate higher likelihood of a subject being classified in the positive class with increasing feature values, otherwise there is a lower likelihood with increasing feature values.

| CIE vs MCI | CIE vs scVMCI | MCI vs scVMCI | AD vs. scVMCI | AD vs. CIE | CIE vs Mixed | AD vs Mixed | Mixed vs scVMCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature category | Penumbra | Penumbra | Penumbra | Penumbra | NABM | Tract | Tract | Tract |

| Rank 1 | Intensity P5 ↑ | Integrity P1 | Integrity P1 | MAD P3 | Integrity | Integrity IFO.L | MAD SLF2.R ↑ | Integrity UF.R |

| Rank 2 | Intensity P4 ↑ | MAD P3 | MAD P3 | MAD P1 ↑ | MAD ↑ | Integrity UF.R ↑ | MAD FMA ↑ | A3 Damage ILF.L ↑ |

| Rank 3 | Intensity P3 ↑ | MAD P4 | MAD P1 ↑ | MAD P4 | A3 Energy | A3 Mean IFO.R | Integrity FMA | A3 Mean CBD.R ↑ |

| Rank 4 | MAD P2 ↑ | MAD P1 ↑ | MAD P4 | Integrity P1 | A3 Mean | MAD FMA ↑ | A3 Mean SLF3.R | MAD FMI ↑ |

| Rank 5 | Integrity P2 | A3 Mean P1 | Intensity P1 ↑ | Intensity P1 ↑ | A3 Entropy ↑ | MAD IFO.R ↑ | A3 Mean SLF2.R | A3 Damage CBP.L ↑ |

| Rank 6 | Integrity P5 | A3 Mean P1 | A3 Mean P1 | MAD P2 | A3 Damage | Integrity UF.L | A3 Mean SLF1.R | A3 Mean CBP.R ↑ |

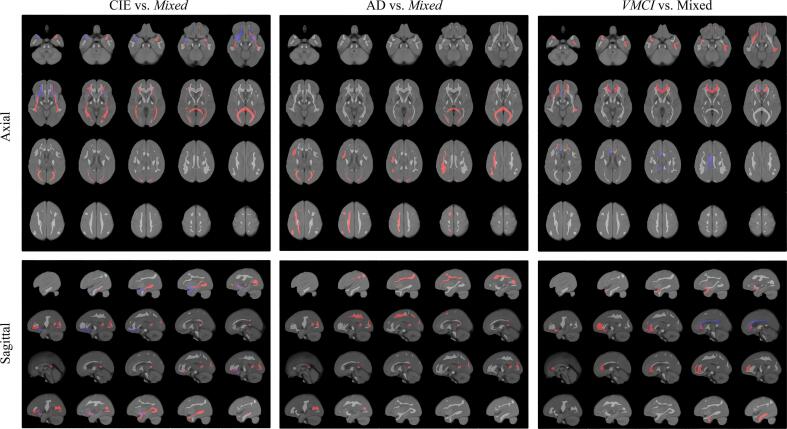

Mixed classifications demonstrated optimal performance with the tract biomarkers and the six most important tract regions for each binary classification as seen in Table 7 are visualized in Fig. 5. For CIE vs. Mixed classification, SHAP analysis found higher damage and lower integrity biomarkers in the bilateral IFO, FMA, and left UF tracts to contribute to the Mixed class. Higher integrity in the right UF contributed to the CIE class. In AD vs. Mixed, higher damage and lower integrity in all right SLF and FMA tracts were found to contribute to the Mixed class. For scVMCI vs. Mixed, higher damage and lower integrity biomarkers in the right UF, left CBP, left ILF, and FMI contributed to a higher likelihood of scVMCI classification. Lower integrity in the right CBD and right CBP were found to contribute to the Mixed class.

Fig. 5.

Important tract regions selected by SHAP analysis for each Mixed group classification overlaid on FLAIR atlas. Red regions indicate tracts with higher damage or lower integrity contributing to higher likelihood of positive class, blue tracts indicate the opposite. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

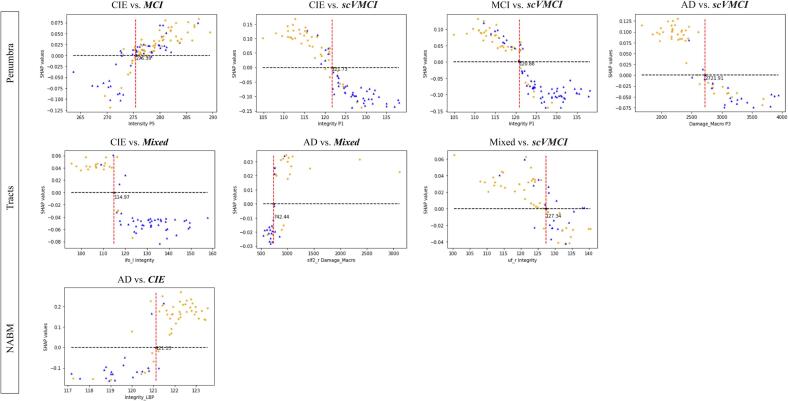

In further analysis, the SHAP dependence plots for the most important feature in each classification were used to determine appropriate thresholds for biomarker values. The plots in Fig. 4 visualize the spread of original biomarker values and the likelihood of positive classification for each data point. For most of the binary classifications, it can be seen that data points with lower integrity and higher damage than the computed thresholds are more likely to be classified in the worse diagnosis group. The thresholds were determined to be the following: 275.39 for intensity in P5 to differentiate between CIE and MCI patients, 121.73 for integrity in P1 to differentiate between scVMCI and CIE patients, 120.88 for integrity in P1 between scVMCI and MCI, 114.97 for integrity in the left IFO tract to differentiate between CIE and Mixed patients, 742.44 for macrostructural damage in the right SLF2 tract to differentiate between AD and Mixed patients, 2721.91 for macrostructural damage in P3 between AD and scVMCI, 127.34 for integrity in the right UF tract to differentiate between Mixed and scVMCI patients, and 121.13 for NABM integrity to differentiate between CIE and AD patients (Appendix Table B20).

Fig. 4.

SHAP feature dependence plots of the most important feature for each binary classification. Data points above y = 0 line have a higher likelihood of being classified in the positive class italicized in plot titles. Red dashed lines indicate potential threshold values of each biomarker for differentiation of data point classes (orange points belonging to the positive class and blue triangles belonging to the other class according to their true labels). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

In this work, FLAIR texture biomarkers were extracted from four regions – NABM, penumbra, BST, and white matter tracts – and used to investigate differences between controls, MCI, AD, scVMCI, and Mixed diagnostic groups. There were significant differences in NABM texture biomarkers between diagnostic groups, with increasing damage and decreasing integrity trends as the severity of the diagnosis increased. This reinforces the findings in Bahsoun et al. that showed global texture patterns in FLAIR are capturing tissue degeneration related to cognitive decline (Bahsoun et al., 2022). The novel wavelet biomarkers demonstrated strong correlations with MD and statistically significant effects in ANOVA and post-hoc tests, effectively supplementing the MAD and MII texture biomarkers from Bahsoun et al. (Bahsoun et al., 2022). Significant interactions were seen between diagnostic groups and sub regions of the penumbra, BST, and tract region biomarkers, indicating strategic regional analysis is appropriate in investigating pathological mechanisms across diagnostic categories. Further investigation of the predictive nature of the regional biomarkers was completed using binary classifications. Classification results demonstrated FLAIR texture and intensity biomarkers can differentiate between diagnostic groups with high accuracy comparable to existing works while maintaining explainability in the biomarkers. Classification of the AD, scVMCI, and Mixed groups from controls yielded the highest accuracies and AUC values for the NABM, penumbra, and tract regions, respectively. This demonstrates that abnormalities in FLAIR images relative to healthy controls may represent imaging surrogates of the pathogenesis of AD, scVMCI, and Mixed disease.

The same classification experiments using the MD and FA features showed that FLAIR performed significantly better for every task, with an average of 21% increase in accuracy. This strongly suggests that FLAIR is highlighting different pathological mechanisms compared to DTI. FLAIR contrast is related to the attenuation of lipid protons in the myelin of WM (Maillard et al., 2013) and white matter damage (highlighted bright in FLAIR) related to vasogenic edema, venous collagenosis, tortuosity, and demyelination (Black et al., 2009). FLAIR texture features measure intensity variations and patterns in local regions, and could capture important microstructural information. FLAIR texture biomarkers were strongly and significantly associated with MD values and weakly associated with FA values in all regions, except the WM tracts which showed moderate correlations with MD. MD measures the magnitude of water diffusion and higher MD values are associated with increased tissue degeneration (Bahsoun et al., 2022). The strong correlation between MD and FLAIR texture biomarkers suggests that FLAIR texture may be related to tissue structure, water content (vasogenic edema) and neurodegeneration. FA measures the amount of diffusion in the principal direction along fiber tracts, and higher FA values indicate better restriction of water diffusion related to fiber density and myelination. Recent studies on dMRI imaging show FA values are highly variable and conclusions about tissue integrity should be made with caution (Figley et al., 2022). Therefore, the low correlation between FLAIR and FA texture biomarkers may be due to variability in the FA metric, or may suggest weaker correlations between the mechanisms of the two modalities.

NABM features were designed in Bahsoun et al. to investigate whole-brain texture and were shown to quantify global disease burden related to cognition (Bahsoun et al., 2022). The NABM region is comprised of normal-appearing WM and GM combined. For the CIE vs. AD classification task, NABM texture biomarkers were found to be the optimal features for characterizing tissue changes related to AD. GM atrophy has been widely studied in dementia (Pini et al., 2016) and used as a biomarker to track disease progression in AD patients (Anderson et al., 2012). While it is likely to have coincident GM and WM changes in AD subjects, some authors suggest GM atrophy is secondary to WM damage (Pievani et al., 2010). Therefore, NABM texture may be capturing disease processes related to AD in both the GM and WM at the same time. Interestingly, FLAIR penumbra biomarkers were optimal features for differentiating between earlier phases of dementia (CIE vs. MCI), whereas NABM texture was the lowest performer. Penumbra regions surrounding the WML have been shown to measure early stage WM disease (Maillard et al., 2013). This suggests that early stage disease has differences in the WM, while late-stage disease (AD) has differences in both the GM and WM (NABM). These results could suggest that GM atrophy is secondary to WM damage, but longitudinal studies will be required to fully understand the mechanisms of MCI to AD progression.

We hypothesized specific regions related to vascularization and WM microstructure will demonstrate differences in cohorts with and without vascular contributions to cognitive impairment. Interestingly, the BST regions did not yield optimal classification results in any of the experiments though they are directly vascularized by the main cerebral arteries. This may be attributed to the fact that a critical level of stenosis in the carotid arteries, which supply the cerebral arteries, may be required for a distal hemodynamic effect to be seen (Powers, 1991). On the other hand, for vascular groups, FLAIR penumbra biomarkers were important for all classifications involving scVMCI, and tract biomarkers were optimal for all classifications involving Mixed disease. The penumbra regions have been shown in various studies to exhibit signs of microstructural tissue damage of vascular origin (Maillard et al., 2013, Promjunyakul et al., 2015, Rowley, 2001, Wu et al., 2019), while WM tracts are known to be prone to vascular insufficiency at the borders of the vascular supplies (Iadecola, 2013).

Wu et al. found extensive alterations of cerebral blood flow (CBF), and less extensive but significant alterations of diffusion measures in penumbra regions of subjects with subcortical VMCI (Wu et al., 2019). Their findings indicate compromised CBF may precede changes in white matter integrity in the penumbras. In this work, the optimal features for differentiating between scVMCI and CIE/MCI/AD were the penumbra texture features. This, coupled with previous research, could suggest features in FLAIR are detecting tissue changes due to altered CBF and diffusion in the scVMCI group compared to controls and AD groups. Qiu et al. also found diffusion features in the penumbra of VMCI patients successfully distinguished them from healthy controls, and suggested early treatment of cardiovascular risk factors to slow WM disease progression (Qiu et al., 2021).

SHAP feature importance analysis of CIE, MCI, and AD vs. scVMCI classification models revealed higher damage and lower integrity biomarkers in the P1 region contributed to a higher likelihood of scVMCI, while the P2 to P5 regions demonstrated the opposite effect. This may be suggesting WM alterations are mainly evident in penumbra regions directly adjacent to WMH in scVMCI patients (could be related to more punctuate/focal lesions), while tissue changes are seen farther away from the WMH in non-vascular diseases (more diffuse WM disease). This coincides with the feature importance analysis of the CIE vs. MCI classification, which showed evidence of main contributions from outer penumbra regions (WM) in which higher damage and lower integrity values increased the likelihood of MCI classification. Maillard et al. also found patients with non-vascular pathology, namely MCI and AD, demonstrated elevated FLAIR intensities in the outer penumbra up to 8 mm away from WML compared to controls (Maillard et al., 2013).

WM tract textures were optimal for classification tasks involving the Mixed group. Several existing tract-based studies have found similar results and postulated that DTI abnormalities in specific tract regions can better characterize patients with VaD and cognitive performance as opposed to whole brain biomarkers (Zarei et al., 2009, Hu et al., 2022). Compared to controls, SHAP feature analysis showed higher damage and lower integrity in the bilateral IFO tracts as major contributors to the Mixed group. The IFO tracts originate in the occipital and parietal lobes, and terminate in the inferior frontal region of the brain (Conner et al., 2018). The SHAP feature analysis results coincide with DTI findings in Zarei et al., where IFO tracts were found to be particularly compromised in VaD compared to AD and control subjects (Zarei et al., 2009). This was attributed to ischemia-induced pathology in the frontal and parietal white matter in VaD patients. To visualize this in the CCNA dataset, the important tracts selected by SHAP analysis for each Mixed group classification are shown in Fig. 5. For CIE vs. Mixed classification, significant biomarker contributions can be seen in the inferior, anterior, and posterior regions of the brain, namely from the bilateral IFO tracts, with some involvement of the bilateral UF tracts. These findings suggest the proposed FLAIR texture biomarkers may be detecting ischemic pathology in white matter tracts. As reports on the relationship between WML lesion load, cerebrovascular disease and dementia are varying (McAleese et al., 2021), FLAIR texture may provide an alternative surrogate marker for vascular disease.

WML are used as markers for cerebrovascular disease, but often the presence of WML alone cannot determine the underlying pathology (vascular or AD-related degeneration) responsible for WM changes (McAleese et al., 2021). Understanding underlying mechanisms of pathological changes in the WM is important for accurate diagnosis, intervention and therapeutic development, thus surrogate markers for vascular disease would be clinically valuable. When investigating the relationship of the regional FLAIR biomarkers with WML load, strong correlations in the NABM, penumbra, and BST regions suggest structural changes in these regions are related to global WML disease burden. On the other hand, weak correlations were seen between WML load and FLAIR biomarkers in the tract regions. This suggests the novel tract-based texture biomarkers are quantifying WM disease in a different manner compared to WML loads and the other biomarkers. Tract biomarkers were found to be the optimal features in all Mixed group classifications, suggesting FLAIR tract textures are detecting subtle microstructural changes related to WM damage. Perhaps WM degeneration measured by FLAIR texture offers a new dimension for measuring vascular-related pathology. A number of studies have observed that venous collagenosis increases vascular resistance, interrupts the flow of interstitial fluid and causes fluid leakage from small veins (vasogenic edema), effectively inducing ischemic changes and reducing amyloid beta clearance in the case of AD (Black et al., 2009, Keith et al., 2017). These mechanisms of WM damage suggest both AD and vascular components to the development of WML, which corresponds to the known etiology of the Mixed disease group, though the extent of contributions to WM damage from ischemia relative to amyloid deposition remain unknown. As such, the proposed tract-based FLAIR biomarkers may be capturing underlying abnormalities caused by venous collagenosis and vasogenic edema in the microstructural tract regions as they are prone to underperfusion, rather than measuring the extent of visible WM damage. Further investigation of the SHAP feature importance analysis is performed to determine if FLAIR biomarkers in specific tract regions can measure differences in the manifestations of ischemia and AD pathology within the Mixed disease group.

For AD vs. Mixed classification, important features were the tracts of the right hemisphere and superior regions of the brain as visualized in Fig. 5, namely in all major areas of the right SLF tract which is in line with known manifestations of vascular pathology. Zhou et al. had found asymmetric microstructural white matter damage in subjects with SVD where the right hemisphere was more injured than the left (Zhou et al., 2018), while Fu et al. and Palesi et al. both reported DTI abnormalities found in the SLF of patients with VaD (Fu et al., 2014, Palesi et al., 2018). Biesbrook et al. found an association between lacunar lesion volume in the SLF and executive functioning, identifying the SLF as a key anatomical structure in VCI (Biesbroek et al., 2017). Therefore, FLAIR biomarkers in the SLF may be quantifying the vascular contributions to the Mixed diagnosis, further reinforcing that regional FLAIR biomarkers can detect ischemic microstructural damage in patients with manifestations of vascular pathology. Additionally, higher damage in the FMA was found to contribute to the Mixed classification. The FMA is a commissural tract formed by the fibers of the splenium of the corpus callosum (CC). It is a known pathogenesis that the splenium of the CC is affected quite early in patients with AD (Palesi et al., 2018), suggesting that damage and integrity biomarkers of the FMA may be detecting manifestations of AD in the Mixed diagnosis. Higher damage of the FMA seen in the Mixed group in comparison to AD may also suggest the Mixed diagnosis displays an additive effect of vascular pathology, which may exacerbate alterations in white matter microstructure in AD (or vice versa).

Feature importance analysis for scVMCI vs. Mixed revealed higher damage in the FMI tract in the scVMCI group. It is known that the genu of the CC, fibers of which make up the FMI, are the main leukoaraiosis areas in subjects with vascular pathology (Palesi et al., 2018). Our results also show higher integrity in the scVMCI group than the Mixed group in the dorsal and posterior regions of the cingulum bundle (CBD and CBP). Catheline et al. found a decrease in FA values in the supero-posterior cingulum in AD patients compared to controls is associated with a reduction in the number of fibers in the posterior part of the cingulum tract (Catheline et al., 2010). This coincides with our findings in the CBD and CBP, suggesting increased degeneration in these tracts causing a reduction in fiber density of the cingulum tracts in the Mixed group (vs. scVMCI) which may be attributed to the AD contribution of the Mixed etiology. These findings suggest that FLAIR tract biomarkers can differentiate between scVMCI and Mixed cohorts and may be providing insight into disease mechanisms related to both AD and vascular disease in the Mixed-disease cohort. They may also offer early regional cues for whether or not a scVMCI patient will progress to a Mixed diagnosis. However, longitudinal analysis of FLAIR tract biomarkers with clinical variables is required to determine the exact role of each tract in the pathogenesis of AD and vascular diseases.

In comparison to previous efforts in differentiating AD from vascular dementia using regional structural approaches, this work presents novel explainable texture biomarkers which have the potential to aid in better understanding the pathological processes involved in the development of AD and vascular dementia. Appendix Table B21 compares our results with existing methods. Our CIE vs. Mixed classification achieved a higher accuracy than reported in any of the previous studies, and the accuracies of the other classification tasks were comparable to the other studies for which one can make a meaningful comparison. In addition to good model performance, the novelty of our method lies firstly in single-modality analysis, secondly in the fact that all designed biomarkers are explainable as measures of damage and integrity, and lastly in the feature analysis which was performed to find the optimal ROIs in multiple classification tasks encompassing a range of cognitive groups. With this methodology, we are able to utilize FLAIR-only texture biomarkers to uncover microstructural differences across the disease states, as well as to propose proof-of-concept of the clinical utility of FLAIR biomarkers.

For clinical translation of the FLAIR MRI biomarkers, thresholds determined by SHAP analysis may be a step towards using the biomarkers for patient-level diagnoses. For most classification pairings, the separation of data points at the determined threshold value is obvious, with more severe diagnoses demonstrating lower integrity and higher damage. This indicates a patient could be diagnosed by biomarker values and the region they fall into in the SHAP plots. AD and Mixed groups or MCI and scVMCI groups have similar clinical symptoms and risk factors and therefore, this panel of FLAIR biomarkers could be used to confirm a diagnosis. The thresholds are explainable and intuitive and could potentially be used to supplement radiological workflows and help stratify patients into homogeneous cohorts. Biomarker thresholds will be further studied in future longitudinal studies and perhaps it will be possible for these biomarkers to track the progression of vascular and non-vascular pathology.

Several key findings in this work should be highlighted. First, correlations of the regional FLAIR biomarkers with MD indicate texture biomarkers may be quantifying WM degeneration related to water content and tissue organization. This may be related to vasogenic edema and venous collagenosis, both of which are known mechanisms of scVMCI. Additionally, all regional biomarkers were correlated to WML load except for the WM tracts. As such, FLAIR texture of the WM tracts may provide surrogate markers for subcortical vascular disease. Classification results further demonstrated that FLAIR textures in the penumbra and WM tract regions are more discriminative of scVMCI and Mixed disease groups, indicating WM degeneration in specific regions may be more important than assessing global WML load in vascular disease groups. Biomarker differences in specific WM tracts between disease groups indicate certain regions may be more largely affected in patients with subcortical vascular disease than in others, and should be further correlated to clinical variables and analyzed longitudinally. Lastly, differences in AD pathology subjects showed that penumbra features were important in early stages of the disease (MCI), while the later stages (AD) had damage to both GM and WM suggesting that WM damage may precede GM atrophy in AD.

There are several limitations to the proposed work. First, the CCNA study did not include vascular disease measures, such as carotid artery stenosis or intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH), which may be used to further investigate regional FLAIR biomarkers and cerebrovascular disease. Future studies should explore the relationships of the designed biomarkers with clinical variables using vascular cohorts, and should also employ additional datasets to evaluate the robustness of the regional biomarkers across cohorts. Secondly, the need for FA volumes in the tract segmentation pipeline imposed a limitation on the FLAIR sample sizes used. The preprocessing of dMRI volumes is prone to errors and as such, reduces the number of patients with matching FLAIR and FA volumes available for analyses. In future work, alternative methods for segmenting and generating masks of the WM tracts should be explored in detail. In particular, the use of deep learning methods for tract segmentation may be able to remove the dependency on FA volumes. Lastly, the analysis in this work was performed cross-sectionally. Longitudinal studies should be done in the future to investigate the progression of disease mechanisms in AD and vascular disease patients, as well as to establish biomarker thresholds that not only separate diagnostic groups, but could be used to monitor or track disease progression to determine optimal treatment points.

5. Conclusion

In this work, texture and intensity biomarkers in FLAIR were designed and extracted from the NABM, penumbra, BST, and WM tract regions to classify between vascular and AD diagnostic groups. Our results, with accuracies exceeding or comparable to existing studies, revealed that the features in the WM tracts, penumbra, and NABM were effective and informative for classifications involving the Mixed, scVMCI, and AD groups respectively. Feature importance analysis highlighted that the regional FLAIR biomarkers may provide clinically useful imaging markers for identifying subjects with subcortical vascular disease. In the future, the biomarkers may be used for patient stratification, investigating disease etiologies, and tracking disease progression.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

-

•

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC); the Government of Ontario; and the Alzheimer’s Society Research Program.

-

•

Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration and Aging (CCNA) for data, data storage, management and standardized MRI protocols [16].

-

•

We would like to acknowledge the help of Dr. Maxime Descoteaux from the Computer Science Department, University of Sherbrooke, for help with processing the dMRI data.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2023.103385.

Contributor Information

Karissa Chan, Email: karissa.chan@torontomu.ca.

Corinne Fischer, Email: corinne.fischer@unityhealth.to.

Pejman Jabehdar Maralani, Email: pejman.maralani@sunnybrook.ca.

Sandra E. Black, Email: sandra.black@sunnybrook.ca.

Alan R. Moody, Email: alan.moody@sunnybrook.ca.

April Khademi, Email: akhademi@torontomu.ca.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

The authors do not have permission to share data.

References

- Albert M.S., DeKosky S.T., Dickson D., Dubois B., Feldman H.H. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the national institute on aging-alzheimer’s association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- V. M. Anderson, J. M. Schott, J. W. Bartlett, K. K. Leung, D. H. Miller, and N. C. Fox, “Gray matter atrophy rate as a marker of disease progression in AD,” Neurobiology of Aging, vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 1194–1202, Jul. 2012. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3657171/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Attems J., Jellinger K.A. The overlap between vascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease - lessons from pathology. BMC Medicine. 2014;12(1):206. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0206-2. [Online]. Available: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avants B.B., Tusison N.J., Song G., Cook P.A., Klein A., Gee J.C. A reproducible evaluation of ants similarity metric performance in brain image registration. Neuroimage. 2011;54 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahsoun M.-A., Khan M.U., Mitha S., Ghazvanchahi A., Khosravani H., Jabehdar Maralani P., Tardif J.-C., Moody A.R., Tyrrell P.N., Khademi A. FLAIR MRI biomarkers of the normal appearing brain matterare related to cognition. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2022;34 doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2022.102955. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213158222000201 [Online]. Available: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbay M., Taillia H., Nedelec-Ciceri C., Arnoux A., Puy L., Wiener E., Canaple S., Lamy C., Godefroy O., Roussel M. Vascular cognitive impairment: Advances and trends. Revue Neurologique. 2017;173(7):473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2017.06.009. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S003537871730468X [Online]. Available: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- J. M. Biesbroek, A. Leemans, H. den Bakker, M. Duering, B. Gesierich, H. L. Koek, E. van den Berg, A. Postma, and G. J. Biessels, “Microstructure of Strategic White Matter Tracts and Cognition in Memory Clinic Patients with Vascular Brain Injury,” Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, vol. 44, no. 5-6, pp. 268–282, 2017, publisher: Karger Publishers. [Online]. Available: https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/485376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Black S., Gao F., Bilbao J. Understanding White Matter Disease: Imaging-Pathological Correlations in Vascular Cognitive Impairment. Stroke. 2009;40, no. 3_suppl_1 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.537704. https://www. ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.537704 [Online]. Available: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellazzi G., Cuzzoni M.G., Cotta Ramusino M., Martinelli D., Denaro F., Ricciardi A., Vitali P., Anzalone N., Bernini S., Palesi F., Sinforiani E., Costa A., Micieli G., D’Angelo E., Magenes G., Gandini Wheeler-Kingshott C.A.M. “A Machine Learning Approach for the Differential Diagnosis of Alzheimer and Vascular Dementia Fed by MRI Selected Features”, Frontiers. Neuroinformatics. 2020;14 doi: 10.3389/fninf.2020.00025. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fninf.2020.00025 [Online]. Available: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- G. Catheline, O. Periot, M. Amirault, M. Braun, J.-F. Dartigues, S. Auriacombe, and M. Allard, “Distinctive alterations of the cingulum bundle during aging and Alzheimer’s disease,” Neurobiology of Aging, vol. 31, no. 9, pp. 1582–1592, Sep. 2010. [Online]. Available: https: //www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0197458008002996. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen Q., Wang Y., Qiu Y., Wu X., Zhou Y., Zhai G. A Deep Learning-Based Model for Classification of Different Subtypes of Subcortical Vascular Cognitive Impairment With FLAIR. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2020;14:557. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00557. [Online]. Available:https: //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7315844/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A. K. Conner, R. G. Briggs, G. Sali, M. Rahimi, C. M. Baker, J. D. Burks, C. A. Glenn, J. D. Battiste, and M. E. Sughrue, “A Connectomic Atlas of the Human Cerebrum—Chapter 13: Tractographic Description of the Inferior Fronto-Occipital Fasciculus,” Operative Neurosurgery, vol. 15, no. Suppl 1, pp. S436–S443, Dec. 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6890527/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- M. de Groot, B. F. Verhaaren, R. de Boer, S. Klein, A. Hofman, A. van der Lugt, M. A. Ikram, W. J. Niessen, and M. W. Vernooij, “Changes in Normal-Appearing White Matter Precede Development of White Matter Lesions,” Stroke, vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 1037–1042, Apr. 2013, publisher: American Heart Association. [Online]. Available: https: //www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/strokeaha.112.680223. [DOI] [PubMed]

- S. Diciotti, S. Ciulli, A. Ginestroni, E. Salvadori, A. Poggesi, L. Pantoni, D. Inzitari, M. Mascalchi, and N. Toschi, Multimodal MRI classification in vascular mild cognitive impairment, Aug. 2015, vol. 2015, journal Abbreviation: Conference proceedings: ... Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Conference Publication Title: Conference proceedings: ... Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Conference. [DOI] [PubMed]

- DiGregorio J., Arezza G., Gibicar A., Moody A.R., Tyrrell P.N., Khademi A. Intracranial volume segmentation for neurodegenerative populations using multicentre FLAIR MRI. Neuroimage: Reports. 2021;1(1) https://www.sciencedirect. com/science/article/pii/S2666956021000040 [Online]. Available: [Google Scholar]

- M. Duering, N. Zieren, D. Hervé, E. Jouvent, S. Reyes, N. Peters, C. Pachai, C. Opherk, H. Chabriat, and M. Dichgans, “Strategic role of frontal white matter tracts in vascular cognitive impairment: a voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping study in CADASIL,” Brain, vol. 134, no. 8, pp. 2366–2375, Aug. 2011. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr169. [DOI] [PubMed]

- M. Fayaz, N. Torokeldiev, S. Turdumamatov, M. S. Qureshi, M. B. Qureshi, and J. Gwak, “An Efficient Methodology for Brain MRI Classification Based on DWT and Convolutional Neural Network,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 22, p. 7480, Nov. 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/21/22/7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- C. R. Figley, M. N. Uddin, K. Wong, J. Kornelsen, J. Puig, and T. D. Figley, “Potential Pitfalls of Using Fractional Anisotropy, Axial Diffusivity, and Radial Diffusivity as Biomarkers of Cerebral White Matter Microstructure,” Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 15, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2021.799576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fu J.-L., Liu Y., Li Y.-M., Chang C., Li W.-B. Use of diffusion tensor imaging for evaluating changes in the microstructural integrity of white matter over 3 years in patients with amnesic-type mild cognitive impairment converting to Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroimaging: Official Journal of the American Society of Neuroimaging. 2014;24(4):343–348. doi: 10.1111/jon.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.-M. Hu, Y.-L. Ma, Y.-X. Li, Z.-Z. Han, N. Yan, and Y.-M. Zhang, “Association between Changes in White Matter Microstructure and Cognitive Impairment in White Matter Lesions,” Brain Sciences, vol. 12, no. 4, p. 482, Apr. 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3425/12/4/482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- C. Iadecola, “The Pathobiology of Vascular Dementia,” Neuron, vol. 80, no. 4, pp. 844–866, Nov. 2013. [Online]. Available: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0896627313009112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Janelidze S., Mattsson N., Palmqvist S., Smith R., Beach T.G., Serrano G.E., Chai X., Proctor N.K., Eichenlaub U., Zetterberg H., Blennow K., Reiman E.M., Stomrud E., Dage J.L., Hansson O. Plasma P-tau181 in Alzheimer’s disease: relationship to other biomarkers, differential diagnosis, neuropathology and longitudinal progression to Alzheimer’s dementia. Nature Medicine. 2020;26(3):379–386. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0755-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- J. Jiang, M. Paradise, T. Liu, N. J. Armstrong, W. Zhu, N. A. Kochan, H. Brodaty, P. S. Sachdev, and W. Wen, “The association of regional white matter lesions with cognition in a community-based cohort of older individuals,” NeuroImage: Clinical, vol. 19, pp. 14–21, Jan. 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213158218301050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jiang D., Lin Z., Liu P., Sur S., Xu C., Hazel K., Pottanat G., Darrow J., Pillai J., Yasar S., Rosenberg P., Moghekar A., Albert M., Lu H. Brain Oxygen Extraction Is Differentially Altered by Alzheimer’s and Vascular Diseases. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2020;52 doi: 10.1002/jmri.27264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith J., Gao F.-Q., Noor R., Kiss A., Balasubramaniam G., Au K., Rogaeva E., Masellis M., Black S.E. Collagenosis of the Deep Medullary Veins: An Underrecognized Pathologic Correlate of White Matter Hyperintensities and Periventricular Infarction? Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 2017;76(4):299–312. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlx009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A. Khademi and S. Krishnan. “Medical image texture analysis: A case study with small bowel, retinal and mammogram images,” in 2008 Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering, May 2008, pp. 001949–001954, iSSN: 0840-7789.

- A. Khademi, D. Hosseinzadeh, A. Venetsanopoulos, and A. Moody, “Nonparametric statistical tests for exploration of correlation and nonstationarity in images,” in 2009 16th International Conference on Digital Signal Processing. Santorini, Greece: IEEE, Jul. 2009, pp. 1–6. [Online]. Available: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/5201186/.

- Khademi A., Gibicar A., Arezza G., DiGregorio J., Tyrrell P.N., Moody A. Segmentation of white matter lesions in multicentre flair mri. Neuroimage: Reports. 2021;1 [Google Scholar]

- Khademi A., Krishnan S. Shift-invariant discrete wavelet transform analysis for retinal image classification. Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing. 2007;45(12):1211–1222. doi: 10.1007/s11517-007-0273-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L. M. Konan, V. Reddy, and F. B. Mesfin, “Neuroanatomy, Cerebral Blood Supply,” in StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532297/. [PubMed]

- B. Liu, S. Meng, J. Cheng, Y. Zeng, D. Zhou, X. Deng, L. Kuang, X. Wu, L. Tang, H. Wang, H. Liu, C. Liu, and C. Li, “Diagnosis of Subcortical Ischemic Vascular Cognitive Impairment With No Dementia Using Radiomics of Cerebral Cortex and Subcortical Nuclei in High-Resolution T1-Weighted MR Imaging,” Frontiers in Oncology, vol. 12, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2022.852726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- S. Lundberg and S.-I. Lee, “A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions,” Nov. 2017, number: arXiv:1705.07874 arXiv:1705.07874 [cs, stat]. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1705.07874.

- P. Maillard, O. Carmichael, D. Harvey, E. Fletcher, B. Reed, D. Mungas, and C. DeCarli, “FLAIR and Diffusion MRI Signals Are Independent Predictors of White Matter Hyperintensities,” American Journal of Neuroradiology, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 54–61, Jan. 2013. [Online]. Available: http: //www.ajnr.org/lookup/doi/10.3174/ajnr.A3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- K. E. McAleese, M. Miah, S. Graham, G. M. Hadfield, L. Walker, M. Johnson, S. J. Colloby, A. J. Thomas, C. DeCarli, D. Koss, and J. Attems, “Frontal white matter lesions in Alzheimer’s disease are associated with both small vessel disease and AD-associated cortical pathology,” Acta Neuropathologica, vol. 142, no. 6, pp. 937–950, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8568857/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McKhann G.M., Knopman D.S., Chertkow H., Hyman B.T., Jack C.R., Kawas C.H., Klunk W.E., Koroshetz W.J., Manly J.J., Mayeux R., Mohs R.C., Morris J.C., Rossor M.N., Scheltens P., Carrillo M.C., Thies B., Weintraub S., Phelps C.H. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3312024/ [Online]. Available: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A. Meoded, A. Poretti, S. Mori, and J. Zhang, “Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI),” in Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology. Elsevier, 2017, p. B978012809324502472X. [Online]. Available: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B978012809324502472X.