Abstract

Glaucoma is a common neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive retinal ganglion cell (RGC) loss and visual field defects. Pathologically high intraocular pressure (ph-IOP) is an important risk factor for glaucoma, and it triggers molecularly distinct cascades that control RGC death and axonal degeneration. Dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1)-mediated abnormalities in mitochondrial dynamics are involved in glaucoma pathogenesis; however, little is known about the precise pathways that regulate RGC injury and death. Here, we aimed to investigate the role of the ERK1/2-Drp1-reactive oxygen species (ROS) axis in RGC death and the relationship between Drp1-mediated mitochondrial dynamics and PANoptosis in ph-IOP injury. Our results suggest that inhibiting the ERK1/2-Drp1-ROS pathway is a potential therapeutic strategy for treating ph-IOP-induced injuries. Furthermore, inhibiting Drp1 can regulate RGC PANoptosis by modulating caspase3-dependent, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor-containing pyrin domain 3(NLRP3)-dependent, and receptor-interacting protein (RIP)-dependent pathways in the ph-IOP model. Overall, our findings provide new insights into possible protective interventions that could regulate mitochondrial dynamics to improve RGC survival.

Keywords: Glaucoma, Retinal ganglion cell, Mitochondrial dynamics, Dynamin-related protein 1, PANoptosis

Highlights

-

•

The ERK1/2-Drp1 signaling pathway is a potential therapeutic target in glaucoma.

-

•

Inhibiting Drp1 phosphorylation protects against ph-IOP-induced PANoptosis.

-

•

ROS-responsive Drp1 prodrugs or ROS scavenging may effectively treat APACG.

-

•

Our study provides new insights into retinal and RGC damage prevention in glaucoma.

1. Introduction

Glaucoma is a heterogeneous group of optic neuropathies characterized by progressive loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), retinal nerve fiber layer thinning, and vision loss. Glaucoma will affect more than 100 million people globally by 2040 [1, 2]. Pathologically high intraocular pressure (ph-IOP) is a major risk factor for the onset and progression of glaucoma, which can cause retinal oxidative stress, inflammation, ischemia-reperfusion (IR), and other pathological damage, ultimately leading to RGC degeneration and death [[3], [4], [5]]. Current treatment strategies for glaucoma are limited and primarily rely on medications or surgery to lower IOP. Unfortunately, lowering IOP does not completely stop glaucoma progression or RGC damage. Several patients with glaucoma experience persistent visual field narrowing despite medication treatment and IOP control within the normal range [2,6,7]. Hence, other causative factors are believed to be involved in retinal damage after IOP recovery. Therefore, finding and controlling these causative factors will aid us in optimizing future therapeutic strategies targeting glaucoma.

Dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) expressed on the outer mitochondrial membrane participates in mitochondrial fission through post-translational modifications, including sumoylation, phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitylation, and S-nitrosylation [[8], [9], [10], [11]]. Drp1 has been shown to play a role in glaucoma, but there are many inconsistencies in the current studies. For example, Mdivi-1, a selective inhibitor of Drp1, increases RGC survival in acute ischemic mouse retina [12]. However, another study found that Drp1 expression was significantly reduced in the neuroretina of the Minipig model with retinal ischemia [13]. In the NMDA-induced retinal glutamate excitotoxicity model, Roscovitine alleviated NMDA-induced mitochondrial fission associated with neuronal loss by inhibiting phosphorylation of CDK5 and Drp1 (Ser585) [14]. In contrast, ERK1/2-Drp1 (Ser585) expression was significantly downregulated in a THA-induced retinal primary neuron model [15]. In a DBA/2J simulated model of spontaneous glaucoma, Drp1 was found to be a potential therapeutic target to ameliorate oxidative stress-mediated mitochondrial fission and dysfunction of the RGC and its axons during glaucomatous neurodegeneration [16], and another study showed that in the same glaucoma model, modulating Drp1 phosphorylation at Ser637 is a potential therapeutic strategy for neuroprotective intervention in glaucoma and other mitochondria-related optic neuropathies [17]. This demonstrates that there are numerous contradictory studies on Drp1 in glaucoma. Furthermore, different glaucoma models can only simulate one reason in the pathogenesis of glaucoma, such as ph-IOP, glutamate excitotoxicity, genetic factors, and so on. Drp1 may play different roles in different glaucoma models, and the role of Drp1 in ph-IOP as a major risk factor in the pathogenesis of glaucoma has not been thoroughly investigated, with the main regulatory mechanisms and the upstream and downstream not being clear.

PANoptosis refers to the simultaneous occurrence of pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis in the pathophysiology of some diseases [18,19]. The PANoptosome complex is assembled from numerous key pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis regulators and regulates PANoptosis. PANoptosis regulates various types of cell deaths that can be broadly classified into caspase-dependent apoptosis, receptor-interacting protein (RIP)-dependent necroptosis, and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor-containing pyrin domain 3 (NLRP3)-dependent pyroptosis. In the ph-IOP injury model, apoptosis is involved in RGC injury and irreversible visual impairment [20]. Recent evidence suggests that RIP1 inhibitors can promote RGC survival by inhibiting necroptosis [21]. In addition, NLRP3-dependent pyroptosis has been linked to ph-IOP-induced RGC death [[22], [23], [24]]. These results suggest that PANoptosis may be involved in ph-IOP-induced RGC death [25]. The relationship between abnormal mitochondrial division and PANoptosis has not been reported.

The ph-IOP glaucoma model is an ideal and widely used animal model for studying sustained RGC loss after IOP control in glaucoma and can simulate the clinical pathogenesis of acute primary angle-closure glaucoma (APACG). APACG is characterized by significantly elevated IOP, acute disease onset, and significant RGC loss within a short period. In addition, APACG is more prone to blood perfusion sensitivity after IOP reduction, leading to IR injury and exacerbating RGC death [26]. The oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion (OGD/R) in vitro model can mimic in vivo ph-IOP-induced IR injury and observe ph-IOP-induced retinal cell abnormalities. In this study, we aimed to explore the changes and abnormalities in Drp1-mediated mitochondrial dynamics in ph-IOP injury and clarify how the ERK1/2-Drp1-ROS axis plays a key role in RGC death. Inhibiting Drp1 phosphorylation protects against ph-IOP-induced PANoptosis, and provides evidence that Drp1-mediated mitochondrial dynamics can effectively regulate cell PANoptosis, with potential therapeutic implications. Overall, this study clarifies the mechanism of mitochondrial dysfunction in glaucoma, provides new insights into retinal and RGC damage prevention, and presents theoretical and practical recommendations for future glaucoma treatments.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture and the oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion (OGD/R) model

The R28 retinal cell line, an adherent retinal precursor cell line derived from the rat retina and widely used in vitro studies, was used in this study. It was provided by the Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology of Central South University (Changsha, China). R28 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (v/v, FBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (v/v, PS, NEST Biotechnology, Wuxi, China) at 37 °C with an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 (v/v). For the OGD/R model, 5 × 105 R28 cells were plated and grown for 24h. After changing the media to glucose-free DMEM, the cells were incubated in a hypoxic chamber (1% O2) (v/v) for 4h followed by 1h, 3h, or 6h reoxygenation in normal complete medium. Control cells were maintained in a complete medium under normoxic conditions. The schematic illustration of this procedure is shown in Fig. 1A.

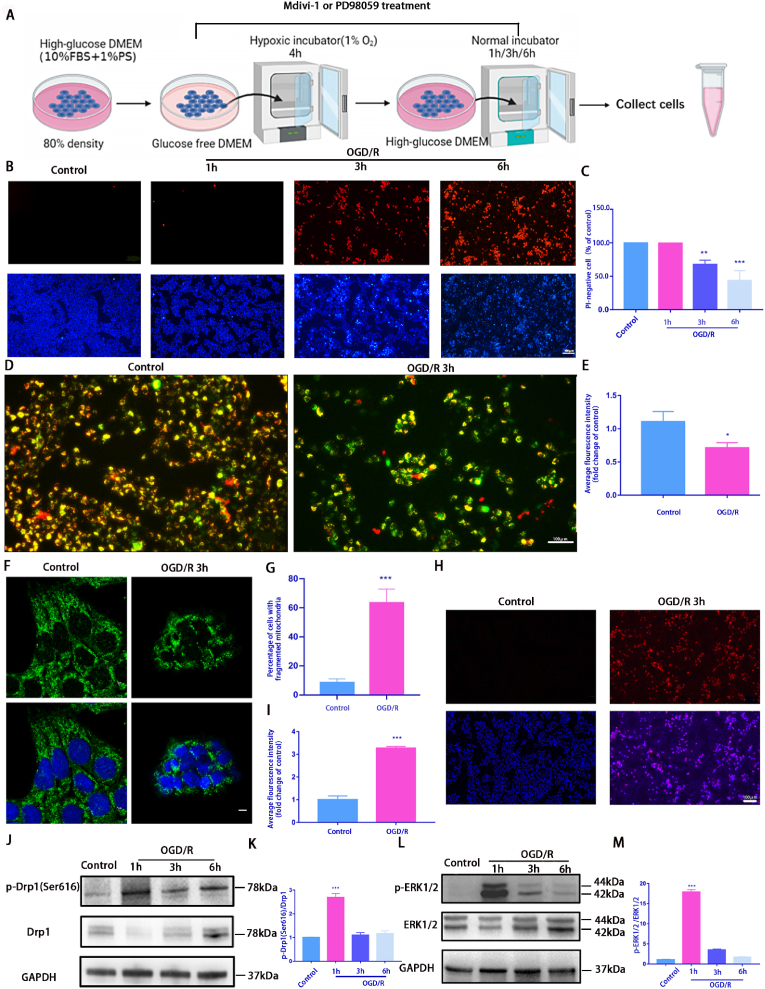

Fig. 1.

OGD/R model induces mitochondrial damage and death in R28 cells

A: A schematic diagram of OGD/R treatment. R28 cells cultured in glucose-free DMEM were incubated in a hypoxic chamber (1% O2) for 4 h followed by 1 h, 3 h, or 6 h reoxygenation in normal complete medium. Control cells were maintained in a complete medium under normoxic conditions. Cells from each time point were used for subsequent analysis; B: OGD/R-induced cell death was detected using Hoechst 33342 and PI dual staining. Scale bar = 100 μm; C: Quantifying the percentage of PI-positive cells(n = 9); D: The ΔψM was measured using JC-1 staining(2.0 μg/mL) after 3h OGD/R. Scale bar = 100 μm; E: The relative red/green ratio quantification(n = 9); F: Confocal microscopy was used to determine mitochondrial morphology using Tom20 antibodies via immunofluorescence after 3 h OGD/R. Scale = 2 μm; G: The average mitochondrial length was analyzed(n = 9); H: Mito-SOX(2 μM) staining was used to detect the ROS level of mitochondrial after 3h OGD/R. Red fluorescence represents mitochondrial ROS production, and Hoechst staining in the nuclei is shown in blue. Scale bar = 100 μm; I: Relative Mito-SOX red fluorescence quantification(n = 9); J and L: Western blotting was performed to detect p-Drp1(Ser616), Drp1, p-ERK1/2, and ERK1/2 expression at each time point after OGD/R treatment; K and M: Quantification of p-Drp1(Ser616), Drp1, p-ERK1/2, and ERK1/2 levels. Relative protein levels were calculated using ImageJ software(n = 9). Values are expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was followed by the Dunnett's test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001and****P < 0.0001 vs Control.

For drug administration, mitochondrial fission inhibitor Mdivi-1 (S7162) purchased from Selleck (Selleck Chemicals, China) and p-ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were used. The concentrations used in this study were determined based on previously published literature [27,28]. Mdivi-1(10 μM) or PD98059(25 μM) was added at the beginning of the OGD/R model, after incubated in a hypoxic chamber (1% O2) (v/v) for 4h, the medium was changed to normal complete medium with Mdivi-1(10 μM) or PD98059(25 μM) and incubated with the time indicated.

2.2. Model of ph-IOP injury and drug delivery

For animals, Wild-type C57BL/6J mice (8 weeks, 18–20 g) were used in this study. The mouse model of ph-IOP was established via the raised IOP (120 mmHg for 45 min) as previously described [26,29]. An anesthetized mouse with dilated pupils and anesthetized corneas was placed on a heating workbench. A 30G needle connected to a saline infusion set was carefully inserted into the mouse's anterior chamber and the anterior chamber pressure was gradually increased to 120 mmHg by adjusting the saline bottle height (162 cm); the pressure was maintained for 45 min. In the control group, a sham operation was performed without raising the pressure in the left eye. For intravitreal drug delivery, intravitreal injections of the drug were injected prior to the start of the ph-IOP model and administered as previously described [30]. The injections were administered using a Hamilton syringe fitted with a 30-gauge glass microneedle under a dissecting microscope. 2 μL liquid of PD98059(5 mM, diluted in the DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and Mito-TEMPO (200 μM, diluted in the DMSO, Selleck Chemicals, China) was slowly injected into the vitreous chambers of the eyes before ph-IOP model conducted [31,32]. Mdivi-1(3 mg/kg; Selleck) dissolved in the DMSO was used intraperitoneal (i.p) injection before the ph-IOP model conducted [27]. All procedures for handling animals were in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (approval number: 2019030171).

2.3. Hoechst 33342/propidium iodide (PI) dual staining assay

An apoptosis and necrosis detection kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) was used to assess cell death rate of the R28 cells. First, R28 cells were plated in 6 cm2 plates and grown for 24h, then subjected to OGD/R treatment. After OGD/R, the cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then incubated with medium containing PI and Hoechst 33342 at 4 °C for 30 min. Afterward, the cells were washed twice and underwent fluorescent imaging using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Leica DMi8, Wetzlar, Germany). To produce a double-blind experiment, for each group, 5 pictures were randomly captured by a researcher who was blind to the study, PI positive cells and Hoechst 33342-stained cells were counted and the percentage of cell death was calculated.

2.4. Immunofluorescence (IF) staining

R28 cells from all groups were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (m/v, Ncmbio, Suzhou, China) for 15 min. Cells were then washed three times with PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Trixton-X-100 in PBS for 10 min. After blocking with 5% BSA(m/v) for 30 min, cells were immunostained with an anti-Tom20 primary antibody (1:200; #42406, Cell Signaling Technology) with 5% BSA(m/v) at 4 °C overnight. Following another three washes with PBS, cells were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody of anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (1:300; Sigma–Aldrich) with 5% BSA(m/v) for 2h. Cells were then washed five times with PBS and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Solarbio, Beijing, China). At least five random images for each experimental condition were captured using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica). Mitochondrial quantification was performed with image J by experimental staff blinded to the experiments. The percentage of cells with fragmented mitochondria was calculated. For each identified object, the major axis length of mitochondria was calculated. Cells were scored with fragmented mitochondria when >50% of the mitochondria displayed a major axis <2 μm. At least 100 cells of three independent experiments were counted.

For immunostaining of paraffin-embedded retinal tissue sections, slides were dewaxed twice with xylene for 20 min each, immersed in 100, 90, 80, and 70% ethanol(v/v) gradient series for rehydration for 5 min each. Then incubated in boiling 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10min for antigen retrieval. After blocking with 5% BSA(m/v) for 1h, the slides were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: anti-RBPMS(1:500, Abcam, ab152101), anti-RBPMS(1:500,Phosphosolution,1832), anti-phospho-MLKL(1:500, #37333), anti-phospho-RIP1(1:250, #44590), anti-phospho-RIP3(1:250, #93654), anti-phospho-Drp1(Ser616)(1:300, #4494), anti-cleaved-caspase3(1:100, #9664) and anti-phospho-ERK1/2(1:300, #9101) obtained from Cell Signaling Technology; anti-caspase1(1:400, 22915), anti-NLRP3(1:100, 19771) obtained from Proteintech (Rosemont, IL, USA). Then the slides were washed three times with PBST (0.1 %Triton-X100, v/v) for 10 min and incubated with the respective Alexa-594-conjugated goat anti-Rabbit and Alexa-488-conjugated goat anti-Guinea pig secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The nuclei were stained with DAPI for 5min. Slides were scanned with a digital slide scanner (Pannoramic 250, 3D Histech, Hungary). Immunofluorescence intensity quantification and counting were performed after setting equivalent thresholds using ImageJ. Similarly, we divided the left and right hemispheres of the optic nerve into three equal parts (six groups of data), and obtained the average fluorescence intensity and the number of positive RBPMS staining after counting each image separately. All of the images are presented at a distance of 720 μm from the ONH. The average number of RGCs per 360 μm length retina was calculated at various ph-IOP times (0h, 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h), and statistical analyses of RGC counting number from each group were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0).

2.5. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

A transmission electron microscope (TEM) was used to assess the mitochondria of RGCs using a HT7700 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan), by locating at RGC layer.

2.6. Western blot (WB) analysis

The cells and homogenized retinas were resuspended in an ice-cold lysis buffer containing a cocktail of protein phosphatases and protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Afterward, whole samples were subjected to sonication and centrifuged (13800 g) at 4 °C for 10 min, and the supernatant was subsequently collected. The total protein concentration was analyzed using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay (New Cell &Molecular biotech, China). Then collect 80 μl lysate and add 20 μl 5x loading buffer (300 mM Tris–HCl [pH 6.8], 40%[v/v] glycerol, 10%[w/v] sodium dodecyl sulfate, 20%[v/v] β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.02%[w/v] bromophenol blue), place on 95 °C heat blotting for 10 min. Proteins in the lysates were separated using 10%(w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis at 140 V. The separated proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane at 300 mA. After blocking for 1 h with 5%(m/v) BSA in PBS with Tween20(PBST), the proteins on the membranes were immunoblotted overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: anti-Drp1(1:1000, #8570), anti-phospho-Drp1(Ser616)(1:1000, #4494), anti-phospho-ERK1/2(1:1000, #9101), anti-NLRP3(1:1000, #15101), anti-N-GSDMD(1:1000, #36425S), anti-cleaved-caspase3(1:1000, #9664), anti-phospho-MLKL(1:1000, #37333), anti-phospho RIP1(1:1000,#31122), anti-RIP1(1:1000, #3493) obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA), anti-caspase1(1:1000, 22915), anti-MLKL(1:5000, 66675) obtained from Proteintech (Rosemont, IL, USA), anti-ERK1/2 (1:1000, ab184699), anti-phospho RIP3(1:1000, ab205421), anti-RIP3 (1:1000,ab62344) obtained from Abcam, and anti-GAPDH (1:3000, T0022) obtained from Affinity Biosciences. The membranes were then washed thrice with PBST, incubated with secondary antibodies (1:1000,Proteintech, SA00001-1; SA00001-2) for 1h at room temperature, and washed thrice. Western blot bands were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence solution (Millipore, USA). Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ.

2.7. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data analysis

The R Bioconductor package edgeR was used to select differentially expressed genes (DEGs). A false discovery rate <0.05 and fold change >2 or <0.5 were set as the cut-off criteria for identifying DEGs. Volcano plots and heatmaps were plotted using volcanoPlot and pheatmap functions in R. To identify functional categories of DEGs, the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database was used for pathway analysis to identify the significant enrichment of different molecular pathways using KOBAS3.0 software (http://www.genome.jp/kegg). The hypergeometric test and Benjamini-Hochberg FDR controlling procedure were used to define the enrichment of each term. The data comes from the SAR database (PRJNA838649).

2.8. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining

Mice were anesthetized and sacrificed, and the eyeballs were enucleated and fixed in 4% PFA(m/v) for 24 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the eyeballs were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 4 μm thick. The sections were then deparaffinized and stained with HE and imaged using a light microscope (Nikon, Japan). Images were randomly captured by a researcher who was blind to the study, and the retinal damage was evaluated by counting the number of cells in the ganglion cell layer (GCL). We divided the location of the optic nerve center equally into three straight lines on either side perpendicular to the retina. The number of cells in the GCL for each image was then counted (six sets of data per image were obtained) and averaged.

2.9. Retinal flat-mounted immunofluorescence

For retinal flat-mounted immunofluorescence, the eyes of mice were enucleated and fixed in 4% PFA(m/v) for 2 h at room temperature, the cornea and lens were removed. After fixed in 4% PFA (m/v) for another 1 h at room temperature, the retinas were dissociated, transferred to a glass slide, and cut into four equal quadrants. Retinas were permeabilized in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100(v/v) for 30 min, followed by blocking in blocking solution (5% BSA) (m/v) for 1.5 h, and then stained with anti-RBPMS (1:500; Abcam; ab152101) overnight at 4 °C. After washing 3 times with PBST, retinas were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit-labeled secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature, followed by mounting. Images were captured using a Nikon Ni-U microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Each retina was divided into 4 quadrants (sharing a central quadrant) and RBPMS + cells were counted using ImageJ to determine the RGC density (RGCs per square millimeter) for that retina. Mean values were calculated for the mean densities of all retinas per group. The relative RGC density in each group was calculated as a percentage of the mean using the control sample as reference. Statistical analyses of the relative RBPMS + cells from each group were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0).

2.10. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining assay

The TUNEL assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche, 11684795910). Briefly, paraffin sections were deparaffinized and permeabilized with proteinase K for 30 min, followed by rinsing the sections three times with 0.1% Triton-X100 in PBS. TUNEL reaction mixture was incubated with the slices for 1 h at 37 °C, after washing 3 times with PBS. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Then sections were imaged using a Ni–U microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Pictures were captured by a researcher who was blind to the study. The number of TUNEL-positive cells in the GCL and inner nuclear layer (INL) was counted for each retinal section.

2.11. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) measurement

The ATP concentration was detected using an ATP assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, S0026, China). Cells and retinas were lysed and centrifuged at 13800 g for 10 min to isolate total protein. Subsequently, 100 μl of the supernatant was added to 100 μl of ATP detection solution, and standard samples were generated. The luminescence was immediately detected using a plate reader (Synergy LX; BioTek, USA).

2.12. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection

R28 cellular transfections were performed using Lipofectamine® 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions. 5 × 105 R28 cells were plated and grown to 30% confluency at the time of transfection. The transfection complexes were prepared with 8 μl lipo2000 and 5 μl of siRNA(50 nm) in 200 μl OptiMEM per 6 cm2 dish (NEST Biotechnology, Wuxi, China). After transfection for 4 h, the medium was removed and the R28 cell culture medium was added and cultured for another 48h (Fig. 2A). siRNAs (RiboBio, Guangzhou, China) with the following sequences were used to silence Drp1 expression:5-GGUGCUAGGAUUUGUUAUATT-3. The sequence for ERK1/2 siRNA was 5-GCACCTCAGCAATG ATCAT-3, and a negative control siRNA (ncRNA) was constructed. 24h after transfection of fluorescent control, the fluorescence distribution in R28 cells was observed by fluorescence microscope (Leica DMi8, Wetzlar, Germany). The Drp1-siRNA (2 nmol/eye) and negative control used for intravitreal injection were provided by Ribobio Biotechnology (Guangzhou, China), and the ph-IOP model was constructed 72h after siRNA injection.

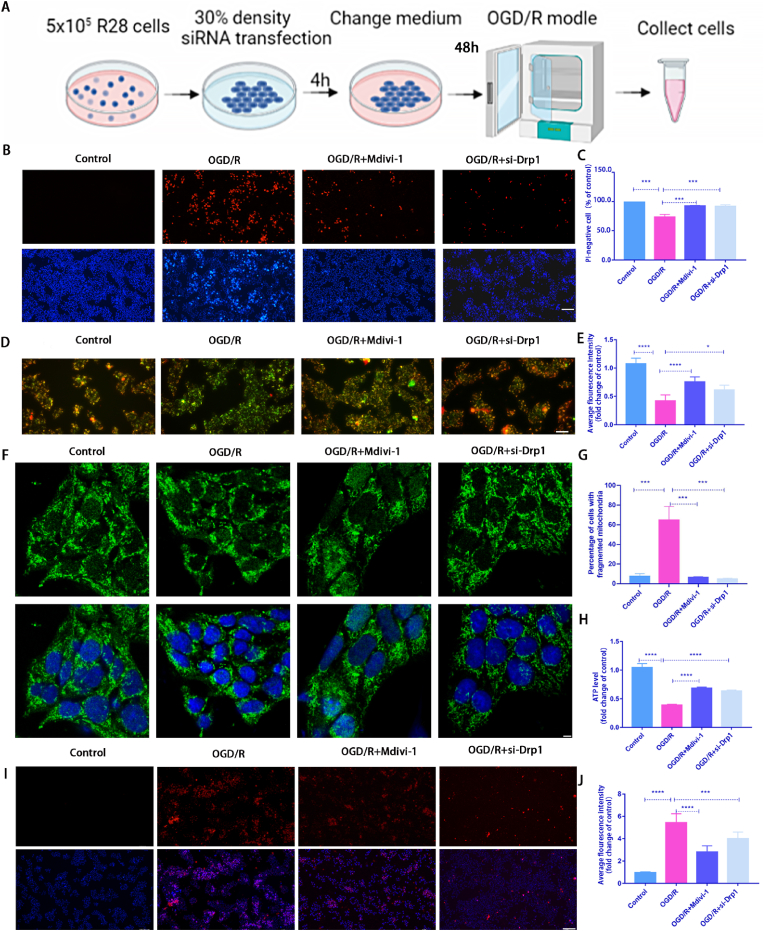

Fig. 2.

Mdivi-1 treatment or silencing Drp1 expression using siRNA transfection alleviated R28 cell injury induced by OGD/R.

A: A schematic diagram of siRNA application. R28 cells were plated and cultured to 30% confluence for transfection. After 4 h transfection, R28 cells were cultured for an additional 48 h and then subjected to OGD/R modeling; B: After Mdivi-1 treatment or silencing Drp1 expression, the cell death rate was detected using Hoechst 33342 and PI dual staining. Scale bar = 100 μm; C: Quantification of the percentage of PI-positive cells(n = 9); D: After Mdivi-1 treatment or silencing Drp1 expression, the ΔψM was measured by JC-1 staining(2.0 μg/ml). Scale bar = 100 μm; E: Quantification of the relative red/green ratio(n = 9); F: After Mdivi-1 treatment or silencing Drp1 expression, mitochondrial morphology was identified using Tom20 antibodies by immunofluorescence. Scale bar = 2 μm; G: Average mitochondrial lengths were analyzed (n = 9); H: After Mdivi-1 treatment or silencing Drp1 expression, ATP assay kit was used to detect ATP production(n = 9); I: After Mdivi-1 treatment or silencing Drp1 expression, Mito-SOX(2 μM) staining to detect the ROS level. Red fluorescent spots represent mitochondrial ROS production, and Hoechst staining in the nuclei is shown in blue. Scale bar = 100 μm; J: Quantification of the relative Mito-SOX red fluorescent intensity(n = 9). Values are expressed as the mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was followed by the Dunnett's test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001and****P < 0.0001 vs OGD/R.

2.13. Mitochondrial membrane potential assay (ΔψM)

Mitochondrial membrane potential was evaluated using the JC-1 mitochondrial membrane potential detection kit (US Everbright Inc, J604, Suzhou, China). Cells were incubated with JC-1(2.0 μg/ml) staining solution for 20 min at 37 °C, and rinsed, then examined using a fluorescence microscope. Mitochondrial membrane potential was detected and analyzed using relative fluorescence ratio staining. The red to green fluorescence ratio was lower in apoptotic and necrotic cells than in normal cells. In normal cells, JC-1 formed as aggregates in the matrix of the mitochondria with a red appearance. When the membrane potential was decreased and JC-1 maintained its monomeric form and turns green. For each group, 5 pictures were randomly captured with a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMi8, Wetzlar, Germany) by a researcher who was blind to the study, after adjusting the uniform threshold using ImageJ, fluorescence intensity was determined for each pixel using ImageJ. The mean fluorescence intensity of these pixels was calculated as the average number of pixels at each group.

2.14. ROS production detection

ROS in the retina were determined using 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, Elabsciences, Shanghai, China). First the retinas were dissociated and lysed, then incubated with 50 μM DCFH-DA working solution at 37 °C for 30 min. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 1000g and washed three times with PBS buffer to remove DCFH-DA. Fluorescence intensity was detected using a microplate reader (Synergy LX; BioTek, USA) with an excitation wavelength at 500 nm and an emission wavelength at 525 nm.

Mito-SOX Red was used to detect mitochondrial ROS (mtROS), and Hoechst was used to stain the nuclei of living cells. For Mito-SOX Red staining, the cells were first incubated with 2 μM fluorochrome for 10 min, washed with PBS, and then detected using a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMi8, Wetzlar, Germany). For each group, 5 pictures were randomly captured, and mean fluorescence intensity of these pixels was calculated as the average number of pixels at each group using ImageJ.

2.15. Clinical sample collection

6 human peripheral blood samples from glaucoma patients with high IOP and 3 human peripheral blood samples from age-matched cataract patients with normal IOP were obtained. Mononuclear cells were separated according to our standard operation procedure. Lysates of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) were detected by Western blot analysis with antibodies recognizing p-ERK1/2, ERK1/2, phosphor-Drp1 (S616), and Drp1 protein.

2.16. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Data were analyzed by Student's t-test or ANOVA (Dunnett's test). Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 software. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. P-values of <0.05, <0.01, <0.001 and < 0.0001 are indicated by *, **, ***and****, respectively. The values are an average of three independent experiments with three mice or cell wells per treatment in each experiment.

3. Results

3.1. OGD/R model induced R28 mitochondrial damage and death in R28 cells

We assessed the cell death rate using Hoechst 33342 and PI dual staining to investigate the effects of the OGD/R model on R28 cells. OGD/R treatment induced R28 cell death, and approximately 30.0% of cells were PI-positive after 3 h of OGD/R treatment (Fig. 1B and C). To determine whether OGD/R-induced damage in R28 cells was associated with mitochondria, mitochondrial morphology, ΔψM, and mtROS were examined. First JC-1 staining was used to detect ΔψM. When the ΔψM is normal, JC-1 form as aggregates with a red appearance; however, once the ΔψM is lowered or lost, the dye turns green (JC-1 monomers). Therefore, the reduction in the red/green ratio reflects the decrease of mitochondrial membrane potential and impaired mitochondrial function. The results revealed that the mitochondrial membrane potential significantly decreased after OGD/R (Fig. 1D and E). Mitochondrial outer membrane protein Tom20 was used to detect mitochondrial morphological changes. Immunofluorescence results showed that the mitochondria became significantly more fragmented after OGD/R (Fig. 1F and G). OGD/R injury also increased the mtROS content, which was detected by Mito-SOX Red (Fig. 1H and I). Thereafter, we examined changes in protein levels related to mitochondrial dynamics and found increased phosphorylation of the mitochondrial fission-related protein Drp1 (Ser616). To explore the upstream targets of Drp1(Ser616) activation, we performed an analysis of the RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) results, the KEGG showed that differential genes were enriched in the MAPK pathway (Figs. 1a–d). We further verified the expression levels of ERK1/2 and p-ERK1/2 after OGD/R. We found that p-Drp1 (Ser616) and p-ERK1/2 expression levels peaked at 1 h after OGD/R, while the expression of Drp1 and ERK1/2 remained largely unchanged (Fig. 1J and M). Based on these findings, we performed follow-up phenotypic studies 3 h after OGD/R. These results preliminarily suggest that the OGD/R model can induce mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death in R28 cells.

3.2. Mdivi-1 and Drp1 siRNA treatment attenuated OGD/R-induced damage in R28 cells

Previous studies have demonstrated that Mdivi-1 is used as an inhibitor of Drp1 (Ser616) [27]. To further determine the impact of Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission on OGD/R-induced damage, Mdivi-1 or siRNA was used to investigate the effect of p-Drp1 (Ser616) on R28 cells in the OGD/R model, respectively. We previously demonstrated that 10 μM Mdivi-1 can inhibit the p-Drp1 (Ser616) level in irradiated R28 cells, without inducing cellular toxicity. Thus, 10 μM Mdivi-1 was used as the effective concentration in this study. Fig. 2A shows a schematic diagram of siRNA application. Compared with the OGD/R group, Mdivi-1 or siRNA treatment significantly decreased PI-positive cells (Fig. 2B and C). Furthermore, Mdivi-1 or siRNA treatment had a protective effect on mitochondrial function. The decrease in ΔψM and ATP production induced by OGD/R were partially recovered in the Mdivi-1 treatment group (Fig. 2D and E; 2H). Furthermore, OGD/R-induced mitochondrial fragmentation and mtROS overproduction decreased significantly following treatment with Mdivi-1 and siRNA, respectively (Fig. 2F and G, 2I and J).

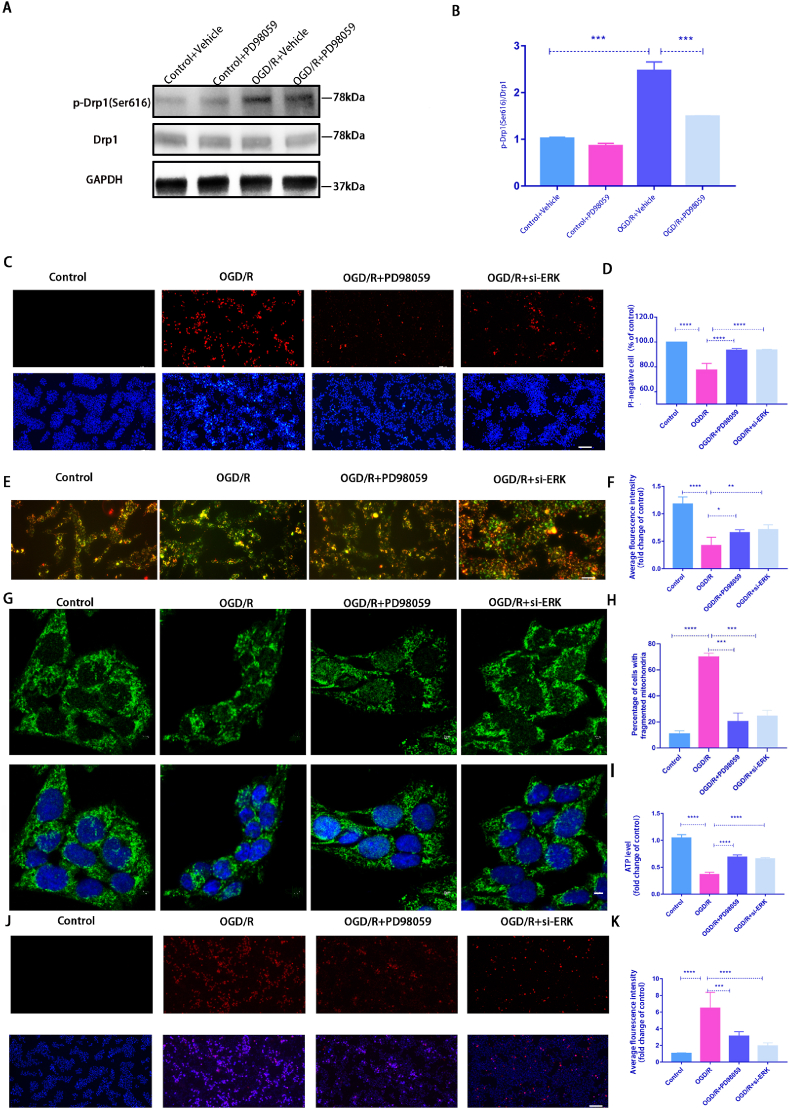

3.3. ERK1/2-mediated Drp1 Ser616 phosphorylation regulated mitochondrial dynamics during OGD/R-induced injury in R28 cells

As p-ERK1/2 was significantly elevated in the OGD/R model, we used PD98059, an inhibitor of p-ERK1/2, to determine whether it could protect against OGD/R injury through p-Drp1 (Ser616) to clarify the relationship between p-ERK1/2 and p-Drp1 (Ser616). Fig. 3A and B shows that the OGD/R-induced increase in p-Drp1 (Ser616) was significantly inhibited after treatment with PD98059. Hoechst 33342 and PI dual staining results revealed that PD98059 or siRNA treatment significantly increased cell survival compared with OGD/R alone (Fig. 3C and D). Moreover, the mitochondrial function was partially recovered, whereas ΔψM and ATP levels increased significantly (Fig. 3E and F, 3I). Additionally, PD98059 and siRNA reduced mitochondrial fragmentation and mtROS production (Fig. 3G and H, 3J and K). siRNA silencing efficiency against ERK1/2 was detected by using WB analysis (Supplement Fig.2). These results demonstrated that inhibiting the ERK-Drp1(Ser616) pathway protects against OGD/R-induced injury by rescuing of mitochondrial dysfunction and clearing mtROS production.

Fig. 3.

PD98059 treatment or silencing ERK1/2 expression by siRNA alleviated OGDR-induced damage to R28 cells.

A: Western blot was used to detect the expression level of p-Drp1 (Ser616) after PD98059 application; B: Quantification of the WB result(n = 9); C: After PD98059 treatment or silencing ERK1/2 expression, the cell death rate was detected by Hoechst 33342 and PI dual staining. Scale bar = 100 μm; D: Quantification of the percentage of PI-positive cells(n = 9); E: After PD98059 treatment or silencing ERK1/2 expression, the ΔψM was measured by JC-1 staining(2.0 μg/ml). Scale bar = 100 μm; F: Quantification of the relative red/green ratio(n = 9); G: After PD98059 treatment or silencing ERK1/2 expression, mitochondrial morphology was identified using Tom20 antibodies by immunofluorescence. Scale = 2 μm; H: Average mitochondrial lengths were analyzed(n = 9); I: After PD98059 treatment or silencing ERK1/2 expression, ATP assay kit was used to detect ATP production(n = 9); J: PD98059 treatment or silencing ERK1/2 expression, Mito-SOX(2 μM) staining to detect the ROS level. Red fluorescent spots represent mitochondrial ROS production, Hoechst staining in the nuclei is shown in blue. Scale = 100 μm; K: Quantification of the relative Mito-SOX red fluorescent intensity(n = 9). Values are expressed as the mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was followed by Dunnett's test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001 vs OGD/R.

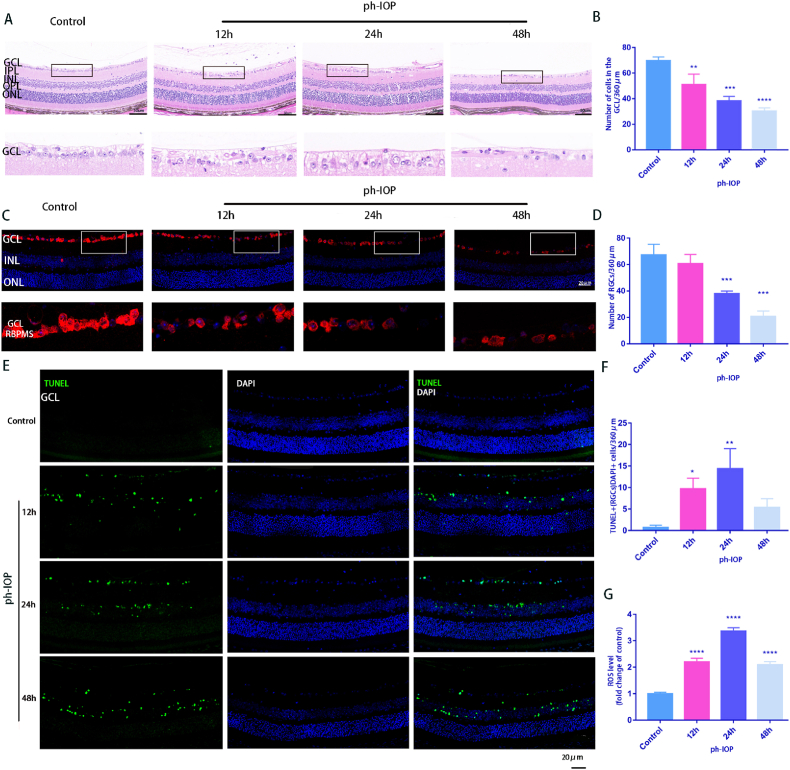

3.4. ph-IOP injury-induced mitochondrial damage and cell death in mouse RGCs

The HE results showed that, compared with the control group, the retinal structure of the ph-IOP group was gradually irregular, the retinal layer was distinctly loose and disordered, and the number of RGCs decreased with time. The retinal GCL and inner plexiform layer (IPL) were markedly edematous, and retinal thickness decreased markedly at 48 h (Fig. 4A). ph-IOP injury significantly reduced the number of cells in the retinal GCL(Fig. 4B). This trend was also observed in RBPMS immunofluorescence staining of retinal paraffin sections, and the number of labeled RGCs was greater in the control group (Fig. 4C and D). The number of TUNEL staining-positive cells also significantly increased after retinal ph-IOP injury (Fig. 4E and F). In addition, the total amount of ROS peaked 24 h after retinal ph-IOP injury and decreased slightly after 48 h (Fig. 4G). Therefore, 24 h was chosen as the observation period for experiments whose results are presented in Fig. 6.

Fig. 4.

ph-IOP injury-induced mitochondrial damage and cell death in RGCs

A: HE-stained retinal sections in control and ph-IOP group at 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h showed retinal structure changes after ph-IOP. Scale bar = 50 μm; The lower pictures are the enlarged representations of the boxed regions of the upper pictures. B: Quantification of the number of cells in the retinal GCL(n = 9); C: RGCs identified using RBPMS antibodies by immunofluorescence with retinal paraffin sections. The lower images are the enlarged representations of the boxed regions of the upper pictures. Scale bar = 20 μm; D: The average number of RGCs at different ph-IOP times (12 h, 24 h, and 48 h) were calculated(n = 9); E: Retinal paraffin sections were stained using TUNEL to observe cell apoptosis. Scale bar = 20 μm; F: TUNEL-positive RGCs were counted(n = 9); G: Retinal ROS generation was determined using DCFH-DA fluorescence intensity quantification after ph-IOP (12 h, 24 h, and 48 h) (n = 9). Values are expressed as the mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was followed by Dunnett's test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001and****P < 0.0001 vs Control.

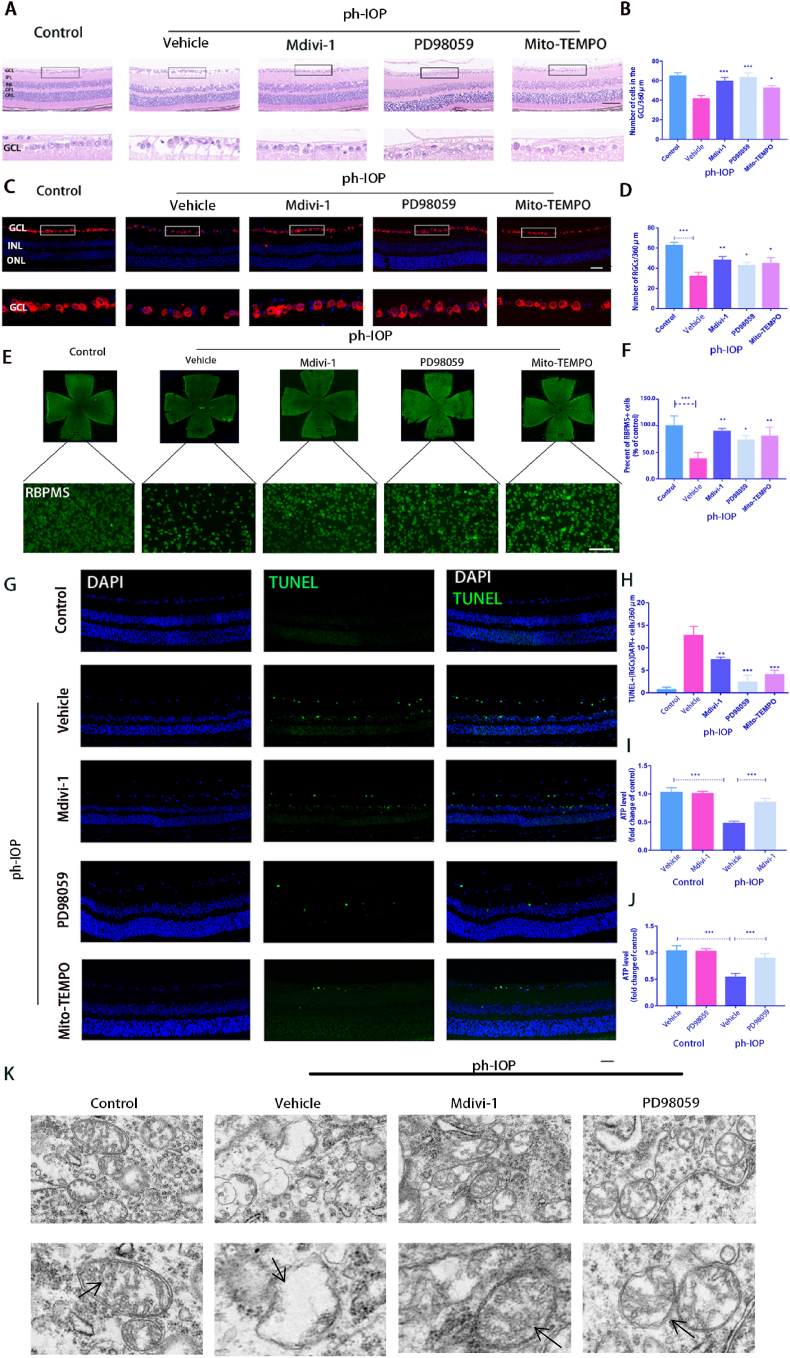

Fig. 6.

Inhibiting the ERK1/2-Drp1-ROS signaling pathway can reduce ph-IOP-induced RGC damage in mouse.

A: After Mdivi-1, PD98059, or Mito-TEMPO treatment, HE was used to observe the retinal morphology and the number of cells in the RGC layer. Scale bar = 50 μm; B: Quantification of the number of cells in the retina GCL of each group(n = 9); C: RGCs identified using RBPMS antibodies by immunofluorescence with retinal paraffin sections. The lower images are the enlarged representations of the boxed regions of the upper pictures. Scale bar = 20 μm; D: The average number of RGCs at different groups were calculated(n = 9); E–F: After Mdivi-1, PD98059 or Mito-TEMPO treatment, RBPMS-positive cells in whole mounted retinas were assessed by observing flat-mounted retinas. Scale bar = 100 μm(n = 9); G: Retinal paraffin sections were stained using TUNEL to observe cell apoptosis. The lower pictures are the enlarged representations of the boxed regions of the upper pictures. Scale bar = 20 μm; H: TUNEL-positive RGCs were counted(n = 9); I–J: ATP kit was used to detect the total content of ATP in the retina(n = 9); K: TEM tracks mitochondrial damage in RGCs, Black arrows indicate the morphology of mitochondria in each group(n = 9). Values are expressed as the mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was followed by the Dunnett's test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and****P < 0.0001 vs ph-IOP + Vehicle.

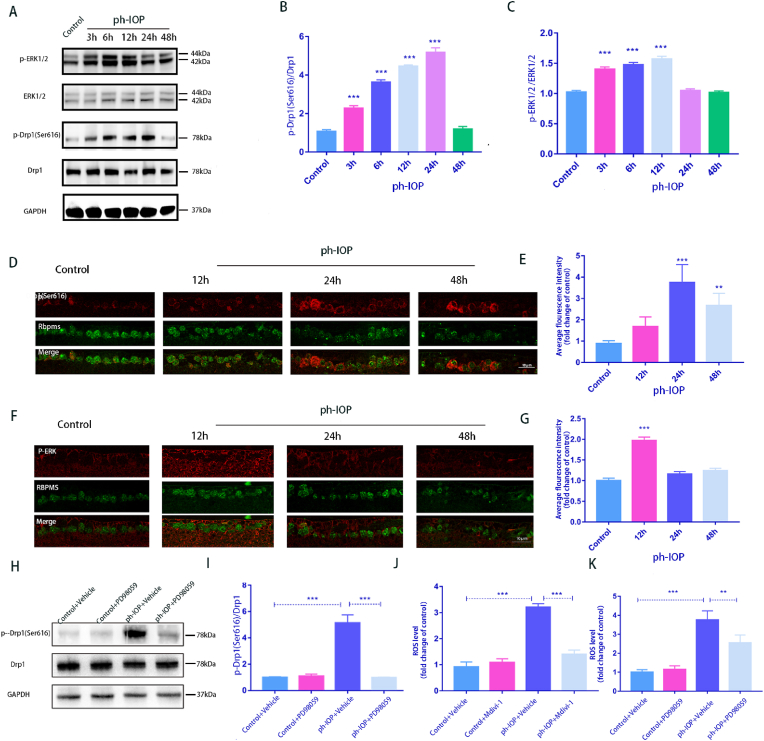

3.5. ph-IOP injury activated ERK1/2-Drp1(Ser616)-ROS signaling pathway

The expression of ERK1/2 and Drp1(Ser616) proteins in the mouse retina were detected at 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h after ph-IOP injury. p-ERK1/2 expression increased at 3 h and peaked at 12 h. Meanwhile, p-Drp1 (Ser616) expression significantly increased at 6 h and peaked at 24 h (Fig. 5A–C). Simultaneously, RBPMS was co-stained with p-Drp1 (Ser616) and p-ERK1/2 for immunofluorescence analysis, and the results were consistent with the WB results (Fig. 5D–G). The fluorescence intensities of p-ERK1/2 and p-Drp1 (Ser616) peaked at 12 h and 24 h, respectively. WB results show that PD98059 treatment of the retina reduces ph-IOP-induced elevation of p-Drp1(Ser616) (Fig. 5H and I), suggesting that p-ERK1/2 may play a role in RGC damage via p-Drp1 (Ser616). Subsequently, Mdivi-1 and PD98059 were used to inhibit p-Drp1 (Ser616) and p-ERK1/2, respectively, which significantly decreased ROS production in the mouse retina (Fig. 5J and K). These results indicated that the ERK1/2-Drp1 signaling pathway could potentially promote ROS generation in ph-IOP injury.

Fig. 5.

ph-IOP model activates the ERK-Drp1-ROS signaling pathway

A: Western blot detected the expression of p-ERK1/2 and p-Drp1 (Ser616); B–C: Western blot quantitative results of p-Drp1 (Ser616) and p-ERK1/2(n = 9); D: Co-staining of p-Drp1 (Ser616) and RBPMS. Scale bar = 10 μm; E: Average fluorescence intensity quantification of p-Drp1 (Ser616) (n = 9); F: Co-staining of p-ERK1/2 and RBPMS. Scale bar = 10 μm; G: Average fluorescence intensity quantification of p-ERK1/2(n = 9); H: After PD98059 treatment, Western blot detected the expression of p-Drp1 (Ser616); I: Quantification of p-Drp1 (Ser616) expression levels after using PD98059(n = 9); J: After Mdivi-1 treatment, retinal ROS generation was determined using DCFH-DA fluorescence intensity quantification (n = 9); K: After treatment with PD98059, retinal ROS generation was determined using DCFH-DA fluorescence intensity quantification(n = 9). Values are expressed as the mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was followed by Dunnett's test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001 vs Control(A-G) or ph-IOP + Vehicle(H-K).

3.6. Inhibiting the ERK1/2-Drp1-ROS signaling pathway reduced ph-IOP-induced RGC damage in mouse

Next, PD98059 (p-ERK1/2 inhibitor), Mdivi-1 (p-Drp1 (Ser616) inhibitor), and Mito-TEMPO (ROS inhibitor) were also used to investigate whether inhibiting the ERK1/2-Drp1-ROS pathway could prevent retinal morphological damage and RGC loss. The HE results showed that 24 h after ph-IOP injury, the retinal morphology and cell numbers in the retinal GCL were significantly damaged in the untreated injury group. After PD98059, Mdivi-1, or Mito-TEMPO treatment, the retinal morphology was partially restored, following which, the number of cells in the GCL also rebounded to a certain extent (Fig. 6A and B). This result was further verified via RBPMS staining (Fig. 6C and D). Similar results were obtained for flat-mounted retina (Fig. 6E and F). The number of TUNEL-positive RGCs and other retinal cells significantly decreased after injecting the inhibitor (Fig. 6G and H). In addition, PD98059 and Mdivi-1 treatments prevented the depletion of retinal ATP. The ATP content was significantly lower in the retina after ph-IOP injury than that in the normal group. The ATP content significantly increased after treatment with the inhibitor (Fig. 6I and J). Mdivi-1 and PD98059 treatment preserved the morphology of the mitochondrial structures in the GCL after ph-IOP injury since the number of mitochondria with disorganized structures was lower in these groups (Fig. 6K).

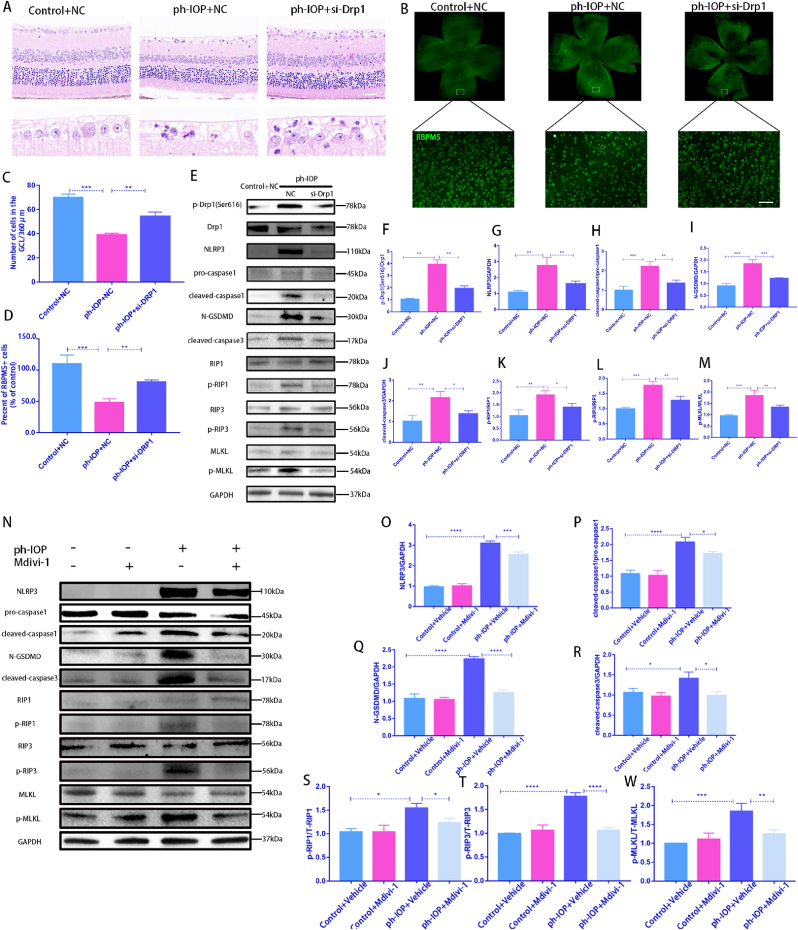

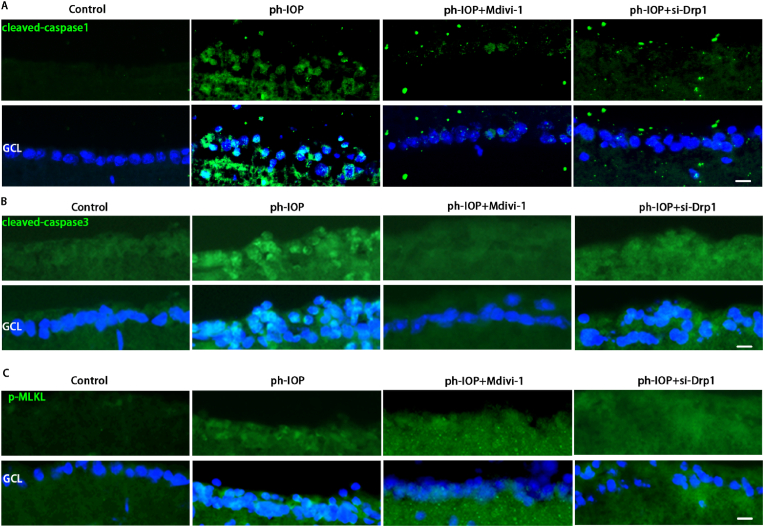

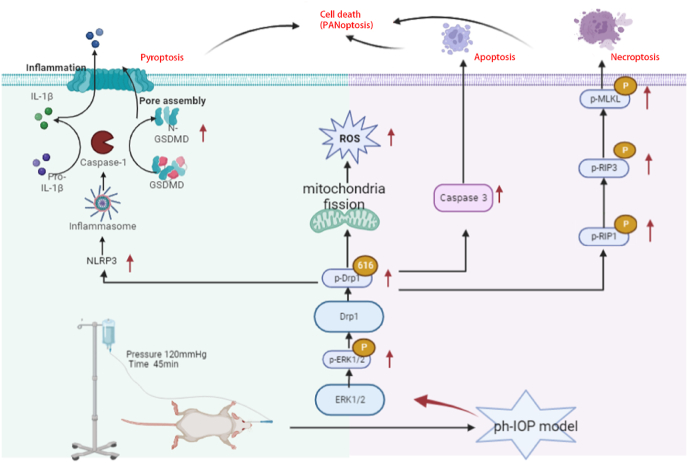

3.7. In vivo inhibition of Drp1 using Mdivi-1 or delivery of siRNA rescues ph-IOP-induced RGC PANoptosis

Drp1 was knocked down via intravitreal injection of Drp1 siRNA, and the ph-IOP model was constructed 72 h after siRNA injection to elucidate the role of Drp1 in ph-IOP-induced glaucoma. We examined retinal morphology and RGC loss after siRNA treatment, and noted that si-Drp1 effectively rescued ph-IOP-induced retinal damage and RGC loss (Fig. 7A–D). WB results revealed that si-Drp1 significantly reduced p-Drp1(Ser616) expression in the test group compared to the Control + NC group (Fig. 7E and F). To investigate the relationship between Drp1 and the PANoptosis of RGCs, we used WB and immunofluorescence to analyze the expression of PANoptosis-related proteins. WB results showed that following si-Drp1 treatment, markers of apoptosis (cleaved-caspase3) (Fig. 7J), pyroptosis (NLRP3/caspase1/GSDMD)(Fig. 7G–I), and necroptosis (p-RIP1/p-RIP3/p-MLKL) (Fig. 7K–M) were significantly downregulated. Similar results to si-Drp1 treatment were obtained using Mdivi-1 in vivo (Fig. 7N–W). Immunofluorescence results showed that cleaved-caspase3, caspase1, and p-MLKL expression levels in the GCL decreased significantly after Mdivi-1 or si-Drp1 treatment (Fig. 8A–C). The immunofluorescence results showing the expression of other PANoptosis-related markers (NLRP3/p-RIP1/p-RIP3) are provided in Figs. S4a–c. Overall, we infer that Drp1 is involved in regulating ph-IOP-induced retinal cell PANoptosis (Fig. 9).

Fig. 7.

Silencing Drp1 expression by siRNA or Mdivi-1 treatment rescues ph-IOP-induced RGC PANoptosis in vivo.

A: After silencing Drp1 expression by siRNA, HE was used to observe the retinal morphology and the number of cells in the RGC layer. Scale bar = 50 μm; B: After silencing Drp1 expression by siRNA, RBPMS-positive cells in whole mounted retinas were assessed by observing flat-mounted retinas; Scale bar = 50 μm; C: Quantification of the number of cells in the GCL of each group(n = 9); D: Quantification of RGC cell density in each group(n = 9); E: After silencing Drp1 expression by siRNA, Western blot used to detected PANoptosis-related proteins; F–M: Western blot results were quantified(n = 9); N:After Mdivi-1 treatment, Western blot was used to detect PANoptosis-related proteins; O–W: Western blot results were quantified(n = 9). Values are expressed as the mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was followed by Dunnett's test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001and****P < 0.0001 vs ph-IOP.

Fig. 8.

Silencing Drp1 expression by siRNA or Mdivi-1 treatment rescues ph-IOP-induced RGC PANoptosis in vivo.

A: After si-Drp1 or Mdivi-1 treatment, retinal immunofluorescence staining detected cleaved-caspase1 expression levels, Scale bar = 10 μm(n = 9); B: After si-Drp1or Mdivi-1 treatment, immunofluorescence used to detect cleaved-caspase3 expression levels, Scale bar = 10 μm(n = 9); C: After si-Drp1 or Mdivi-1 treatment, immunofluorescence used to detect p-MLKL expression levels, Scale bar = 10 μm (n = 9). NC: negative control. Values are expressed as the mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA was followed by Dunnett's test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001and****P < 0.0001 vs ph-IOP.

Fig. 9.

ph-IOP -induces the death of RGCs through the ERK1/2-Drp1-ROS signaling pathway

ph-IOP injury is an important pathological process in the development of glaucoma and can aggravate the damage of RGCs in glaucoma. In this study, ph-IOP injury induced the increased phosphorylation of ERK1/2, followed by the phosphorylation of Drp1 at serine 616. This led to mitochondrial fission and dysfunction (decreased mitochondrial membrane potential, decreased ATP, etc.), resulting in the production of large amounts of ROS, eventually leading to the PANoptosis of RGCs. Regulation of Drp1-mediated abnormalities in mitochondrial dynamics is a potential therapeutic target for ph-IOP-induced PANoptosis.

3.8. ERK1/2-Drp1 signaling pathway is activated in mononuclear cells of patients with glaucoma with high IOP

We obtained human peripheral blood mononuclear cells from six patients with glaucoma who had high IOP to validate our results. WB analysis revealed that p-ERK1/2 and p-Drp1(Ser616) expression were markedly higher than that of normal control individuals (Figs. S3a–b). These results suggest that ERK1/2-mediated Drp1(Ser616) is likely involved in glaucoma pathogenesis in patients who also have high IOP.

4. Discussion

Glaucoma pathogenesis is extremely complex, and the underlying mechanisms and factors remain unknown. The currently accepted risk factor for glaucoma is ph-IOP, in addition to glutamate excitotoxicity and immune abnormalities [2]. Several studies have demonstrated the importance of Drp1 in the pathogenesis of glaucoma. In a recent review on Drp1 and neurodegenerative diseases, we found that there are multiple upstream targets that regulate the role of Drp1 in glaucoma pathogenesis [33]. Examples include GSK-3β, AKAP1, and CDK5 [14, 17, 34], and in our study, we sequenced mRNA in the ph-IOP model retina and found that the MAPK pathway was one of the major enriched pathways. Interestingly, in our previous study in the glutamate excitotoxicity model [15], it was demonstrated that glutamate excitotoxicity induced dephosphorylation of ERK1/2 and its downstream protein Drp1 S585, and decreased the excitotoxicity of glutamate in primary retinal neurons, which is contrary to this finding that ERK1/2-Drp1 signaling was up-regulated in the ph-IOP model. Regarding the reasons for the opposite results, we suggest that different pathogenic mechanisms may exist in the glutamate excitotoxicity model and the ph-IOP model. In this study, we show for the first time that blocking the ERK1/2-Drp1-ROS signaling pathway can effectively rescue RGC death in a ph-IOP model. Drp1 can be regulated by various kinases, with ERK1/2 playing the most prominent role in the ph-IOP model. However, our findings show that p-ERK1/2 is not expressed in RGCs. Previous research has reported that p-ERK1/2 is mostly expressed in the Müller cells [35], hence, we hypothesize that early upregulation of p-ERK1/2 expression in the ph-IOP model can activate Müller cells, regulates the upregulation of p-Drp1(Ser616) expression in RGCs, which ultimately causes the onset of PANoptosis in RGCs. However, the relationship between Müller cells and RGCs needs to be further explored in the future.

PANoptosis is a newly emerging concept that highlights the crosstalk and coordination that occurs between three of these pathways, that is, pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis [36]. When PANoptosis is activated, blocking one form of cell death (pyroptosis, apoptosis, or necroptosis alone) cannot prevent cell death. In-depth characterization of the detailed mechanisms of PANoptosis activation in the ph-IOP glaucoma model will be important for glaucoma treatment in the future. In current previous studies, Drp1 has been shown to regulate apoptosis or necrosis of RGCs alone [37,38]. However, the presence of PANoptosis in glaucoma has recently been demonstrated [36,39], suggesting that inhibition of pyroptosis, apoptosis, or necroptosis alone is not sufficient for the protection of RGCs in glaucoma. This study focused on the relationship between Drp1-mediated mitochondrial dynamics and different modes of cell death in glaucoma. We provide the first evidence that cellular surveillance of mitochondrial dynamics is a key checkpoint in controlling PANoptosis in ph-IOP-induced RGC injuries. Excessive mitochondrial fission may be an early event of mitochondrial damage in IR and other neuronal injuries.

In this study, we examined the changes of Drp1(Ser616) in multiple species, R28 cells from rats, retinas from mice, and peripheral blood from glaucoma patients. We found that Drp1(Ser616) showed significant changes in multiple species of glaucoma models, and this high degree of conservation and consistency provides a good basis for future development of clinical drug development against Drp1(Ser616) targets. Most importantly, our study highlights the anti-PANoptosis effects of Drp1 modulation, revealing that the ERK1/2-Drp1 signaling pathway is a potential therapeutic target for this disease. ERK1/2 are ubiquitously expressed hydrophilic non-receptor proteins that participate in the MAPK cascade and regulate multiple pathways, including cell survival, differentiation, proliferation, and other processes. In our immunostaining results, p-ERK1/2 was distributed in various layers of retinal cells, while p-Drp1(Ser616) was mainly located in RGCs. Hence, targeting Drp1 or its downstream ROS might be the best choice, and developing ROS-responsive prodrugs for Drp1 or ROS scavenging may be an effective therapy for APACG.

Another noteworthy aspect is the role of mitochondrial ROS disruption and redox system imbalance in glaucomatous PANoptosis. Previous studies have demonstrated that ROS and other important enzymes related to the redox system are altered during glaucoma pathology. For example, glutathione (GSH) activity is significantly downregulated in the peripheral blood of patients with several types of glaucoma [40] and in the retinas of ph-IOP mouse model [26], and a study concluded that the redox proteins thioredoxin(TXN)1 and TXN2 support RGCs survival in experimental glaucoma [41]. In addition, NADHP and others enzymes have been shown to show changes in models of ph-IOP. All of these studies remind us that disruption of redox system imbalance has an important role in glaucoma pathogenesis. In our study, we found that regulating Drp1 could modulate ROS production, and that targeted inhibition of mitochondrial ROS using Mito-TEMPO alleviated RGCs death and retinal damage. Previous studies have also shown that ROS, GSH, and the TXN system interact with each other [42,43], so we hypothesize that Drp1 can mediate the mitochondrial ROS production during the development of glaucomatous, leading to the disruption of the balance of the redox system and ultimately causing PANoptosis. To determine in the future the role of mitochondrial ROS as well as other redox enzymes in glaucomatous PANoptosis, specific small molecule inhibitors can be further used.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital of Central South University approved this study (approval number: 2019030171). Informed consent was obtained from all human subjects recruited.

Author contributions

Z. Zeng and M. L. You performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript; C. Fang and R. Rong analyzed the Results; H.B. LI and X.B. Xia designed the experiments and edited the manuscript.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors agree to publish and have no conflicts of interest.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the SAR database (PRJNA838649).

Funding

This work was supported by the National key research and development program of China(2020YFC2008205)、the Key research and development plan of Hunan Province of China (No.2020SK2076); National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.82171058、81974134、81670858) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Central South University(2022ZZTS0822).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Central Laboratory of Xiangya Hospital of Central South University for providing us with relevant instruments for experiments.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2023.102687.

Contributor Information

Haibo Li, Email: lihaibo@csu.edu.cn.

Xiaobo Xia, Email: xbxia21@csu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Kang J.M., Tanna A.P. Glaucoma. Med. Clin. 2021;105:493–510. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2021.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinreb R.N., Aung T., Medeiros F.A. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA. 2014;311:1901–1911. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zukerman R., Harris A., Oddone F., Siesky B., Verticchio Vercellin A., Ciulla T.A. Glaucoma heritability: molecular mechanisms of disease. Genes. 2021;12 doi: 10.3390/genes12081135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almasieh M., Wilson A.M., Morquette B., Cueva Vargas J.L., Di Polo A. The molecular basis of retinal ganglion cell death in glaucoma. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2012;31:152–181. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun M.H., Pang J.H., Chen S.L., Han W.H., Ho T.C., Chen K.J., Kao L.Y., Lin K.K., Tsao Y.P. Retinal protection from acute glaucoma-induced ischemia-reperfusion injury through pharmacologic induction of heme oxygenase-1. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010;51:4798–4808. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prosseda P.P., Alvarado J.A., Wang B., Kowal T.J., Ning K., Stamer W.D., Hu Y., Sun Y. Optogenetic stimulation of phosphoinositides reveals a critical role of primary cilia in eye pressure regulation. Sci. Adv. 2020;6 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aay8699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein J.D., Khawaja A.P., Weizer J.S. Glaucoma in adults-screening, diagnosis, and management: a review. JAMA. 2021;325:164–174. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nunnari J., Suomalainen A. Mitochondria: in sickness and in health. Cell. 2012;148:1145–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan D.C. Mitochondrial dynamics and its involvement in disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2020;15:235–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012419-032711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giacomello M., Pyakurel A., Glytsou C., Scorrano L. The cell biology of mitochondrial membrane dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020;21:204–224. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meyer J.N., Leuthner T.C., Luz A.L. Mitochondrial fusion, fission, and mitochondrial toxicity. Toxicology. 2017;391:42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2017.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park S.W., Kim K.Y., Lindsey J.D., Dai Y., Heo H., Nguyen D.H., Ellisman M.H., Weinreb R.N., Ju W.K. A selective inhibitor of drp1, mdivi-1, increases retinal ganglion cell survival in acute ischemic mouse retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011;52:2837–2843. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-5010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pasak M., Vanisova M., Tichotova L., Krizova J., Ardan T., Nemesh Y., Cizkova J., Kolesnikova A., Nyshchuk R., Josifovska N., Lytvynchuk L., Kolko M., Motlik J., Petrovski G., Hansikova H. Mitochondrial dysfunction in a high intraocular pressure-induced retinal ischemia Minipig model. Biomolecules. 2022;12 doi: 10.3390/biom12101532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jahani-Asl A., Huang E., Irrcher I., Rashidian J., Ishihara N., Lagace D.C., Slack R.S., Park D.S. CDK5 phosphorylates DRP1 and drives mitochondrial defects in NMDA-induced neuronal death. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015;24:4573–4583. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng Z., Li H., You M., Rong R., Xia X. Dephosphorylation of ERK1/2 and DRP1 S585 regulates mitochondrial dynamics in glutamate toxicity of retinal neurons in vitro. Exp. Eye Res. 2022;225 doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2022.109271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim K.Y., Perkins G.A., Shim M.S., Bushong E., Alcasid N., Ju S., Ellisman M.H., Weinreb R.N., Ju W.K. DRP1 inhibition rescues retinal ganglion cells and their axons by preserving mitochondrial integrity in a mouse model of glaucoma. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1839. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards G., Perkins G.A., Kim K.Y., Kong Y., Lee Y., Choi S.H., Liu Y., Skowronska-Krawczyk D., Weinreb R.N., Zangwill L., Strack S., Ju W.K. Loss of AKAP1 triggers Drp1 dephosphorylation-mediated mitochondrial fission and loss in retinal ganglion cells. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:254. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2456-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samir P., Malireddi R.K.S., Kanneganti T.D. The PANoptosome: a deadly protein complex driving pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis (PANoptosis) Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020;10:238. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y., Kanneganti T.D. From pyroptosis, apoptosis and necroptosis to PANoptosis: a mechanistic compendium of programmed cell death pathways. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021;19:4641–4657. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas C.N., Berry M., Logan A., Blanch R.J., Ahmed Z. Caspases in retinal ganglion cell death and axon regeneration. Cell Death Dis. 2017;3 doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2017.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Do Y.J., Sul J.W., Jang K.H., Kang N.S., Kim Y.H., Kim Y.G., Kim E. A novel RIPK1 inhibitor that prevents retinal degeneration in a rat glaucoma model. Exp. Cell Res. 2017;359:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin C., Wu F., Zheng T., Wang X., Chen Y., Wu X. Kaempferol attenuates retinal ganglion cell death by suppressing NLRP1/NLRP3 inflammasomes and caspase-8 via JNK and NF-kappaB pathways in acute glaucoma. Eye. 2019;33:777–784. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0318-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qi Y., Zhao M., Bai Y., Huang L., Yu W., Bian Z., Zhao M., Li X. Retinal ischemia/reperfusion injury is mediated by Toll-like receptor 4 activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014;55:5466–5475. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wan P., Su W., Zhang Y., Li Z., Deng C., Li J., Jiang N., Huang S., Long E., Zhuo Y. LncRNA H19 initiates microglial pyroptosis and neuronal death in retinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:176–191. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0351-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qin Q., Yu N., Gu Y., Ke W., Zhang Q., Liu X., Wang K., Chen M. Inhibiting multiple forms of cell death optimizes ganglion cells survival after retinal ischemia reperfusion injury. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13:507. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-04911-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao F., Peng J., Zhang E., Ji D., Gao Z., Tang Y., Yao X., Xia X. Pathologically high intraocular pressure disturbs normal iron homeostasis and leads to retinal ganglion cell ferroptosis in glaucoma. Cell Death Differ. 2022;30:69–81. doi: 10.1038/s41418-022-01046-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rong R., Xia X., Peng H., Li H., You M., Liang Z., Yao F., Yao X., Xiong K., Huang J., Zhou R., Ji D. Cdk5-mediated Drp1 phosphorylation drives mitochondrial defects and neuronal apoptosis in radiation-induced optic neuropathy. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:720. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-02922-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kong D., Gong L., Arnold E., Shanmugam S., Fort P.E., Gardner T.W., Abcouwer S.F. Insulin-like growth factor 1 rescues R28 retinal neurons from apoptotic death through ERK-mediated BimEL phosphorylation independent of Akt. Exp. Eye Res. 2016;151:82–95. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ha Y., Liu H., Xu Z., Yokota H., Narayanan S.P., Lemtalsi T., Smith S.B., Caldwell R.W., Caldwell R.B., Zhang W. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-regulated CXCR3 pathway mediates inflammation and neuronal injury in acute glaucoma. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6 doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu H., Zhang W., Zhao Y., Shu X., Wang W., Wang D., Yang Y., He Z., Wang X., Ying Y. GSK3beta-mediated tau hyperphosphorylation triggers diabetic retinal neurodegeneration by disrupting synaptic and mitochondrial functions. Mol. Neurodegener. 2018;13:62. doi: 10.1186/s13024-018-0295-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang S., Huang P., Yu H., Lin Z., Liu X., Shen X., Guo L., Zhong Y. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathway is insufficiently involved in the neuroprotective effect by hydrogen sulfide supplement in experimental glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019;60:4346–4359. doi: 10.1167/iovs.19-27507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piippo N., Korhonen E., Hytti M., Kinnunen K., Kaarniranta K., Kauppinen A. Oxidative stress is the principal contributor to inflammasome activation in retinal pigment epithelium cells with defunct proteasomes and autophagy. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018;49:359–367. doi: 10.1159/000492886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi W., Tan C., Liu C., Chen D. Mitochondrial fission mediated by Drp1-Fis1 pathway and neurodegenerative diseases. Rev. Neurosci. 2022 doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2022-0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu J.H., Zhang S.H., Gao F.J., Lei Y., Chen X.Y., Gao F., Zhang S.J., Sun X.H. RNAi screening identifies GSK3beta as a regulator of DRP1 and the neuroprotection of lithium chloride against elevated pressure involved in downregulation of DRP1. Neurosci. Lett. 2013;554:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeng S., Zhang T., Chen Y., Chu-Tan J., Jin K., Lee S.R., Yam M.X., Madigan M.C., Fernando N., Cioanca A., Zhou F., Zhu M., Zhang J., Natoli R., Fan X., Zhu L., Gillies M.C. Inhibiting the activation of MAPK (ERK1/2) in stressed Muller cells prevents photoreceptor degeneration. Theranostics. 2022;12:6705–6722. doi: 10.7150/thno.71038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye D., Xu Y., Shi Y., Fan M., Lu P., Bai X., Feng Y., Hu C., Cui K., Tang X., Liao J., Huang W., Xu F., Liang X., Huang J. Anti-PANoptosis is involved in neuroprotective effects of melatonin in acute ocular hypertension model. J. Pineal Res. 2022;73 doi: 10.1111/jpi.12828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu S.M., Liao L.S., Huang J.F., Wang S.C. Role of CAST-drp1 pathway in retinal neuron-regulated necrosis in experimental glaucoma. Curr Med Sci. 2022;43:166–172. doi: 10.1007/s11596-022-2639-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tonner H., Hunn S., Auler N., Schmelter C., Pfeiffer N., Grus F.H. Dynamin-like protein 1 (DNML1) as a molecular target for antibody-based immunotherapy to treat glaucoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23 doi: 10.3390/ijms232113618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonzalez-Rodriguez P., Fernandez-Lopez A. PANoptosis: new insights in regulated cell death in ischemia/reperfusion models. Neural Regen Res. 2023;18:342–343. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.343910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gherghel D., Mroczkowska S., Qin L. Reduction in blood glutathione levels occurs similarly in patients with primary-open angle or normal tension glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013;54:3333–3339. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-11256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren X., Leveillard T. Modulating antioxidant systems as a therapeutic approach to retinal degeneration. Redox Biol. 2022;57 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu T., Sun L., Zhang Y., Wang Y., Zheng J. Imbalanced GSH/ROS and sequential cell death. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2022;36 doi: 10.1002/jbt.22942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park W.H. Upregulation of thioredoxin and its reductase attenuates arsenic trioxide-induced growth suppression in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells by reducing oxidative stress. Oncol. Rep. 2020;43:358–367. doi: 10.3892/or.2019.7414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the SAR database (PRJNA838649).

Data will be made available on request.