Dear editor,

Dysregulated inflammatory responses primarily account for damage to the central nervous system, however, neurodegenerative processes likely contribute to the pathophysiology of progressive forms of multiple sclerosis (MS). These pathophysiological aspects include axonal energy depletion and impaired remyelination capacity (Levin et al., 2014). The clinical efficacy of most disease-modifying therapies in MS to date has been achieved by targeting functions of the adaptive immune system (Cree et al., 2019; Szepanowski et al., 2021). In light of the unmet need for a regenerative therapy in multiple sclerosis, the concept of high-dose biotin (HDB) treatment (approximately 10,000-fold the recommended daily allowance) as a neurometabolic modulator arose (Sedel et al., 2016). Biotin is an essential cofactor for five carboxylase enzymes: pyruvate carboxylase, propionyl-coenzyme A (CoA) carboxylase, 3-methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase and two isoforms of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), ACC-265 and ACC-280 (Zempleni and Kuroishi, 2012). Given the involvement of these carboxylases in a wide range of metabolic pathways, it has been hypothesized that supraphysiological doses of biotin might have neuroprotective and regenerative potential. For example, HDB might contribute to adenosine triphosphate production by increasing intermediates of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and may improve remyelination by elevating levels of the ACC product, malonyl-CoA, as a building block for fatty acid synthesis (Sedel et al., 2016). However, these claims regarding the presumptive mode of action of HDB have barely been validated in preclinical studies employing appropriate animal models. Nevertheless, an open-label pilot study investigating the efficacy of HDB in patients with primary and secondary progressive MS revealed promising results (Sedel et al., 2015). A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study (MS-SPI) indicated that HDB might reverse disability in a subgroup of progressive MS patients compared to the placebo arm (Tourbah et al., 2016). Despite these initial positive results, the subsequent phase 3 trial (SPI2) did not show significant improvements of disability, leading to the conclusion that HDB cannot be recommended for patients with progressive forms of MS (Cree et al., 2020).

The presumed efficacy of HDB in progressive MS patients had been suggested to - at least in part - result from increased myelin synthesis in oligodendrocytes. This assumption stems from the observation that, within the central nervous system, the ACC-265 isoform appears to be predominantly expressed in oligodendrocytes and that highest ACC 265 activity correlates with the course of postnatal central nervous system myelination (Tansey and Cammer, 1988; Sedel et al., 2016). Similarly, there is evidence for significantly increased ACC 265 expression during postnatal sciatic nerve myelination (Salles et al., 2003). Furthermore, ACC-265 expression has been reported to be reduced by approximately 70% in sciatic nerves of trembler mutant mice, a model for peripheral nervous system dysmyelination (Salles et al., 2003). These findings indicate a fundamental role of ACC 265 in developmental peripheral nervous system myelination and may therefore have implications for targeting ACC-265 activity during the process of remyelination.

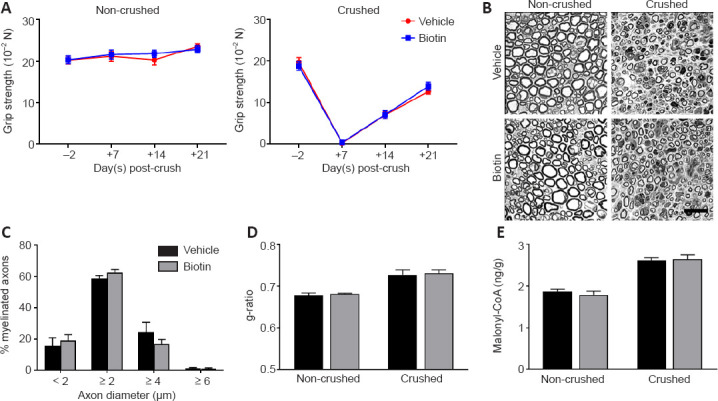

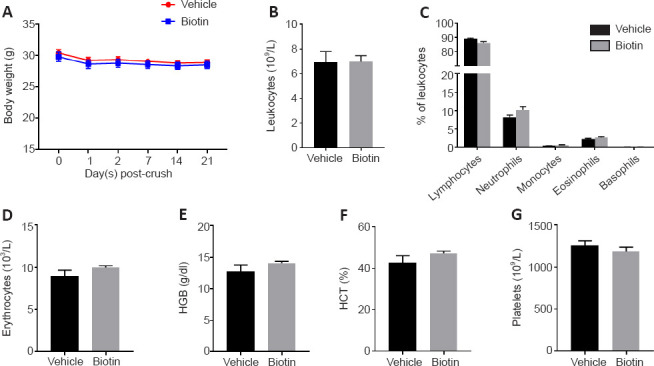

To this end, we performed sciatic nerve crush in wild-type C57BL/6J mice treated with 60 mg/kg biotin (corresponding to human equivalent dose of 300 mg per day in MS patients (Sedel et al., 2016) via daily intraperitoneal injection, starting immediately after crush injury was introduced. Animals were subjected to clinical testing by grip strength analysis of the left (non-crushed) and right (crushed) hindlimbs at 2 days before and 7, 14 and 21 days post-crush (Figure 1A). We did not observe any improvement of grip strength under HDB treatment. Coherently, histological analyses performed at 21 days post-crush (Figure 1B) revealed that HDB did not affect the distribution of myelinated axons (Figure 1C) and, most importantly, did not improve myelin thickness as determined by g-ratio measurements (Figure 1D). At 14 days post-crush, during the phase of ongoing remyelination, we prepared sciatic nerve homogenates to quantify the ACC enzymatic product malonyl-CoA, a building block for fatty acid synthesis. In line with elevated metabolic activity in the regenerating nerve, we were able to detect highly significant increases in malonyl-CoA levels in crushed nerves as compared to non-crushed controls (Figure 1E). However, there was no additional improvement under HDB treatment, indicating that the proposed mechanism of HDB driving ACC activity and thus malonyl-CoA formation is not present to a measurable extent. Of note, HDB treatment was nevertheless well tolerated by the animals and did not affect weight (Figure 2A) or basic hematological parameters (Figure 2B–G).

Figure 1.

High-dose biotin neither improves peripheral nerve regeneration nor elevates malonyl-coenzyme A (CoA) levels.

(A) Grip strength was assessed in crushed and contralateral non-crushed hindlimbs 2 days before crush (−2) and 7 (+7), 14 (+14) and 21 (+21) days post-crush (n = 10 for both groups and all time points). (B) Toluidine blue-stained semi-thin sections of the distal injured nerve stump at 21 days post-crush. Scale bar: 10 µm. (C) Axon diameter histogram indicates no differences in the percentage of myelinated axons in crushed nerves between the treatment groups. (D) g-ratio measurements at 21 days post-crush indicate no impact of high-dose biotin treatment on myelin thickness and remyelination, respectively (n = 3 for all columns). (E) Malonyl-CoA levels are strongly upregulated in the regenerating nerve (P < 0.0001 non-crushed vs. crushed nerves), but not increased by high-dose biotin treatment (n = 7/8/7/8 from left to right). Data are represented as mean ± SEM, and were analyzed by Student’s t-test. The detailed procedures are shown in Additional file 1 (115.1KB, pdf) . Unpublished Data.

Figure 2.

High-dose biotin does not affect body weight or basic hemogram profiles.

(A) High-dose biotin did not affect body weight after crush injury (n = 10 for both groups). At 21 days post-injury, hemogram profiles were generated from blood samples taken by retrobulbar puncture immediately after animals were sacrificed. (B) The total number of circulating leukocytes was unaffected by treatment with high-dose biotin. (C) Coherently, no significant differences were observed for leukocyte subpopulations including lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, eosinophils and basophils. (D–G) Also, no differences were detected in basic parameters including erythrocytes (D), hemoglobin (HGB) (E), hematocrit (HCT) (F) and platelets (G) (n = 9 for both groups). Data are represented as mean ± SEM, and were analyzed by Student’s t-test. The detailed procedures are shown in Additional file 1 (115.1KB, pdf) . Unpublished Data.

Collectively, our findings strongly suggest that HDB is not effective in promoting peripheral nerve regeneration and that HDB does not modulate the activity of its proposed target – namely ACC and malonyl-CoA production. As such, we conclude that HDB does not improve myelin repair in the peripheral nervous system, which may explain why it cannot promote remyelination in the central nervous system.

We thank Stefanie Hezel and Kristina Wagner (both at the Department of Neurology, University Medicine Essen, Germany) for excellent technical assistance.

Additional files:

Additional file 1 (115.1KB, pdf) : Detailed procedures.

Detailed procedures.

Additional file 2: Open peer review report 1 (81.5KB, pdf) .

Footnotes

Availability of data and materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Open peer reviewer: Christina Dimovasili, Boston University, USA.

P-Reviewer: Dimovasili C; C-Editors: Zhao M, Liu WJ, Yu J; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- 1.Cree BAC, Mares J, Hartung HP. Current therapeutic landscape in multiple sclerosis:an evolving treatment paradigm. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019;32:365–377. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cree BAC, Cutter G, Wolinsky JS, Freedman MS, Comi G, Giovannoni G, Hartung HP, Arnold D, Kuhle J, Block V, Munschauer FE, Sedel F, Lublin FD. Safety and efficacy of MD1003 (high-dose biotin) in patients with progressive multiple sclerosis (SPI2):a randomised, double-blind , placebo-controlled , phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:988–997. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30347-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin MC, Douglas JN, Meyers L, Lee S, Shin Y, Gardner LA. Neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis involves multiple pathogenic mechanisms. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis. 2014;4:49–63. doi: 10.2147/DNND.S54391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salles J, Sargueil F, Knoll-Gellida A, Witters LA, Cassagne C, Garbay B. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase and SREBP expression during peripheral nervous system myelination. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1631:229–238. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(03)00041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sedel F, Papeix C, Bellanger A, Touitou V, Lebrun-Frenay C, Galanaud D, Gout O, Lyon-Caen O, Tourbah A. High doses of biotin in chronic progressive multiple sclerosis:a pilot study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sedel F, Bernard D, Mock DM, Tourbah A. Targeting demyelination and virtual hypoxia with high-dose biotin as a treatment for progressive multiple sclerosis. Neuropharmacology. 2016;110:644–653. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szepanowski F, Warnke C, Meyer Zu Hörste G, Mausberg AK, Hartung HP, Kleinschnitz C, Stettner M. Secondary immunodeficiency and risk of infection following immune therapies in neurology. CNS Drugs. 2021;35:1173–1188. doi: 10.1007/s40263-021-00863-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tansey FA, Cammer W. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase in rat brain. I. Activities in homogenates and isolated fractions. Brain Res. 1988;471:123–130. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(88)90157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tourbah A, Lebrun-Frenay C, Edan G, Clanet M, Papeix C, Vukusic S, De Seze J, Debouverie M, Gout O, Clavelou P, Defer G, Laplaud DA, Moreau T, Labauge P, Brochet B, Sedel F, Pelletier J MS-SPI study group. MD1003 (high-dose biotin) for the treatment of progressive multiple sclerosis:A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Mult Scler. 2016;22:1719–1731. doi: 10.1177/1352458516667568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zempleni J, Kuroishi T. Biotin. Adv Nutr. 2012;3:213–214. doi: 10.3945/an.111.001305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detailed procedures.