Abstract

The relationship between the human placenta—the extraembryonic organ made by the fetus, and the decidua—the mucosal layer of the uterus, is essential to nurture and protect the fetus during pregnancy. Extravillous trophoblast cells (EVTs) derived from placental villi infiltrate the decidua, transforming the maternal arteries into high-conductance vessels1. Defects in trophoblast invasion and arterial transformation established during early pregnancy underlie common pregnancy disorders such as pre-eclampsia2. Here we have generated a spatially resolved multiomics single-cell atlas of the entire human maternal–fetal interface including the myometrium, which enables us to resolve the full trajectory of trophoblast differentiation. We have used this cellular map to infer the possible transcription factors mediating EVT invasion and show that they are preserved in in vitro models of EVT differentiation from primary trophoblast organoids3,4 and trophoblast stem cells5. We define the transcriptomes of the final cell states of trophoblast invasion: placental bed giant cells (fused multinucleated EVTs) and endovascular EVTs (which form plugs inside the maternal arteries). We predict the cell–cell communication events contributing to trophoblast invasion and placental bed giant cell formation, and model the dual role of interstitial EVTs and endovascular EVTs in mediating arterial transformation during early pregnancy. Together, our data provide a comprehensive analysis of postimplantation trophoblast differentiation that can be used to inform the design of experimental models of the human placenta in early pregnancy.

Subject terms: Development, Biotechnology

A multiomics single-cell atlas of the human maternal–fetal interface including the myometrium, combining spatial transcriptomics data with chromatin accessibility, provides a comprehensive analysis of cell states as placental cells infiltrate the uterus during early pregnancy.

Main

During the nine months of human pregnancy, the successful development of the fetus is entirely dependent on its placenta. This transient extraembryonic organ is located at the interface between the mother and her fetus. Placental trophoblast cells arise from the trophectoderm surrounding the preimplantation embryo6. After implantation, EVTs emerge from the cytotrophoblast shell, infiltrate the decidua—the mucosal lining of the pregnant uterus, and migrate towards the spiral arteries where they destroy the smooth muscle media. Subsequently, endovascular trophoblast cells (eEVTs) form a plug close to the cytotrophoblast shell where the arteries terminate and then eEVTs replace the endothelium1. In this way EVTs transform maternal arteries in the decidua basalis into high-conductance vessels2,7–9. EVTs fuse into placental bed giant cells (GCs) around the decidual–myometrial boundary and normally invade only as far as the inner third of the myometrium10. Placentation and successful pregnancy depend on the correct degree of trophoblast invasion, and the decidua has an important role in this process11,12.

Our previous single-cell transcriptomics analysis of the first trimester maternal–fetal interface provided an unprecedented view of the cell states comprising this environment13. However, trophoblast cells present in the deeper layers of the decidua and myometrium are only present in samples of pregnant hysterectomies, and the villous syncytiotrophoblast (SCT), a multinucleated layer, is lost in classical single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). A further difficulty is the loss of spatial context in these samples, which is essential to systematically resolve the interactions between trophoblast and decidual cells in early pregnancy. In addition, novel in vitro models have been developed recently, including trophoblast stem cells (TSCs) expanded in vitro5 and self-renewing primary trophoblast organoids3,4,14 (PTOs). These models can recapitulate some aspects of placental development and invasion, opening paths towards mechanistically dissecting trophoblast invasion in humans. Single-cell studies15,16 show that these models are promising but a comprehensive benchmarking has been lacking.

Here we present a spatially resolved single-cell multiomic characterization of the maternal–fetal interface. We examine the site of placentation from historical samples of first trimester hysterectomies, which include the entire uterus containing the placenta, decidua and myometrium. Spatiotemporal ordering of trophoblast invasion enables us to predict the potential participants regulating placentation. We use this comprehensive detailed account of trophoblast differentiation to benchmark existing PTO and TSC models. Finally, we describe the interactions between trophoblast subsets and decidual cells that are likely to affect how arterial transformation by trophoblast occurs. Thus, we provide a description of the whole trajectory of human trophoblast cell states in the first trimester and their spatial niches.

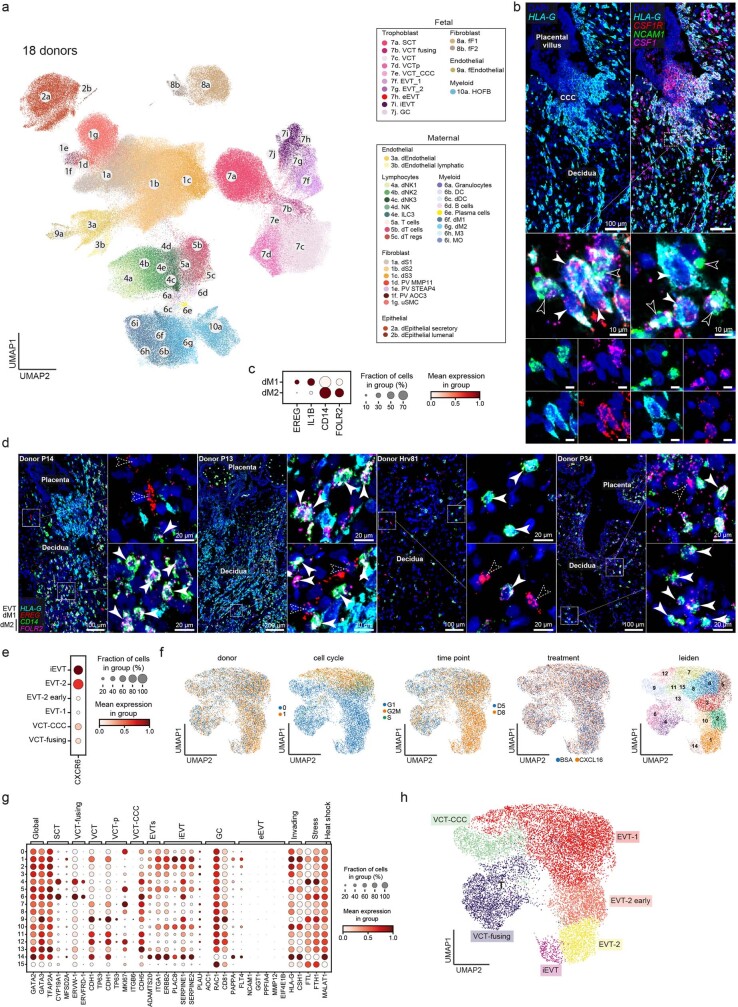

A spatial map of human placental bed

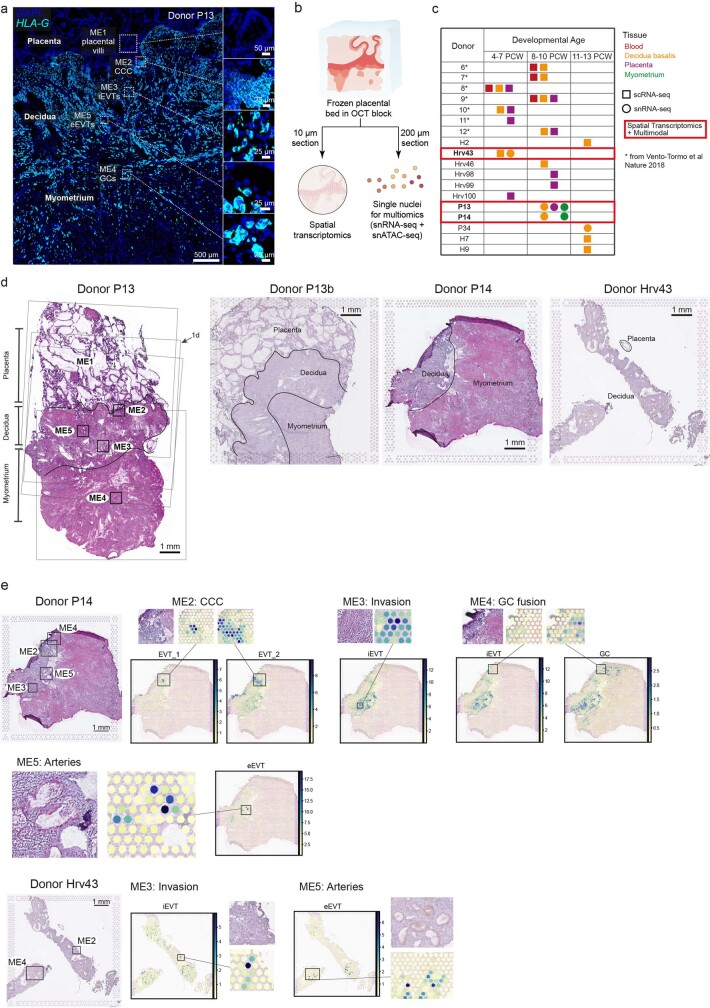

We profiled three human implantation sites (between 6 and 9 post-conceptional weeks (PCW)) using a multimodal approach (Fig. 1a,b, Extended Data Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Tables 1–3). Consecutive sections from frozen tissue blocks of the implantation site were used for: (1) single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq); (2) combined snRNA-seq and single-nuclei assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (snATAC–seq) (we refer to the combined analysis as the multiome); and (3) spatial transcriptomics using Visium (Extended Data Figs. 1c and 2a–d). To account for the large tissue area of one donor (P13), we targeted four consecutive sections with four spatial transcriptomics capture areas (Extended Data Fig. 1d). We also profiled five decidual and three placental samples from 5–13 PCW by scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq and integrated all the data with our previous scRNA-seq dataset of the maternal–fetal interface13 (Extended Data Figs. 1c and 2e). Our single-cell and spatial transcriptomics map is available at https://reproductivecellatlas.org.

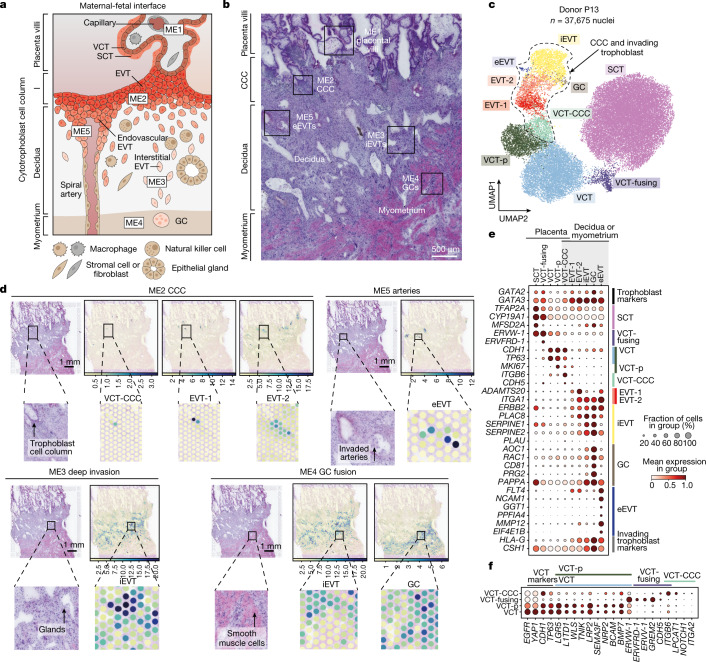

Fig. 1. Trophoblast cell states in the early maternal–fetal interface.

a, Schematic representation of the maternal–fetal interface during the first trimester of human pregnancy. b, Histological overview (haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining) of the implantation site of donor P13 (approximately 8–9 PCW) (n = 1). Black outlines indicate trophoblast microenvironments in space. c, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot of snRNA-seq of donor P13 trophoblast nuclei in the maternal–fetal interface (n = 37,675 nuclei) coloured by cell state. d, Overview of spatial locations of invading trophoblast cell states in Visium spatial transcriptomics data of a section of donor P13 tissue (the position of the capture area is indicated with an arrow in Extended Data Fig. 1d). Spot colour indicates cell state density computed by cell2location, which is the number of cells of a given cell state in a Visium spot. Invading trophoblast cell states are grouped on the basis of the spatial microenvironment that they represent. e, Dot plots showing normalized, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of genes (y-axis) characteristic of trophoblast cell states (x-axis) in donor P13 snRNA-seq data. f, Dot plots showing normalized, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of genes (x-axis) characteristic of villous cytotrophoblast (y-axis) in donor P13 snRNA-seq data.

Extended Data Fig. 1. Spatial transcriptomics of human placental bed.

a: High-resolution imaging of a section of the placenta-decidua interface stained by in situ hybridization (smFISH) for HLA-G, illustrating the depth of invasion of EVTs into the uterus (n = 1). Magnified insets (dashed squares) highlight the HLA-G-negative placental villi, and HLA-G+ EVTs emerging from the CCC to invade the decidua and myometrium. b: Overview of experimental design of the study. c: Cohort composition split by gestational age window (post-conceptional weeks, PCW) representing tissues sampled from each donor and performed assays. Highlighted in red rectangles are the three donors whose tissues have been additionally profiled with spatial transcriptomics (Visium) and multiome assays. d: Histological overview (H&E staining) of donors P13, P14 and Hrv43 tissues with annotations of tissue regions. For the implantation site of donor P13 (~ 8-9 PCW, left); black squares (small) indicate trophoblast microenvironments in space; faint grey squares (large) indicate positioning of tissue on Visium spatial transcriptomics capture areas; arrow indicates representative Visium section further explored in Fig. 1d. For Visium, P13 (n = 5 feature areas, 4 consecutive slides with overlapping positions and 1 slide from an additional tissue block - P13b), P14 (n = 2 feature areas, consecutive slides with same position), Hrv43 (n = 1 feature area). e: Cell state locations (derived with cell2location) in representative Visium sections of donors P14 and Hrv43 highlighting relevant spatial trophoblast microenvironments. Spot colour indicates cell state densities computed by cell2location as the number of cells of a given cell state in a Visium spot. Cytotrophoblast cell column (CCC), extravillous trophoblast (EVT), interstitial EVT (iEVT), giant cells (GC), endovascular EVT (eEVT), single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq), microenvironment (ME), Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E).

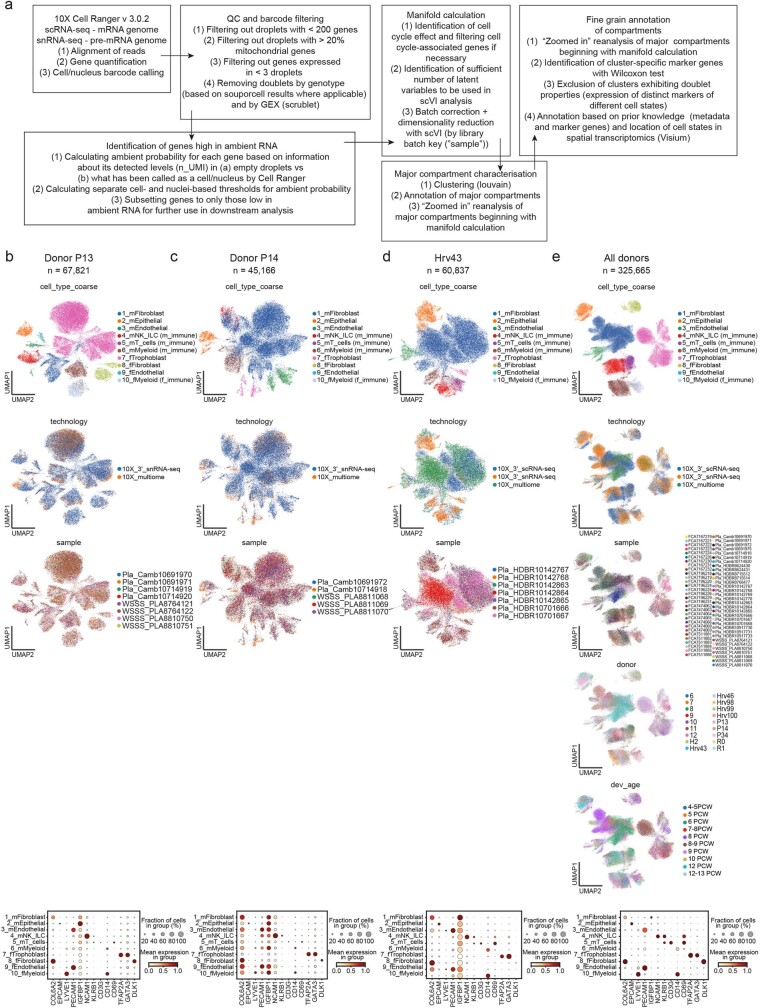

Extended Data Fig. 2. scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq data quality control and data analysis overview.

a: Overview of the computational pipeline implemented for analysis of in vivo scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq data. Data integrated with scVI. b–e: (top) UMAP (uniform manifold approximation and projection) scatterplots of donors P13 (n = 67,821 nuclei), P14 (n = 45,166 nuclei), Hrv43 (n = 60,837 nuclei and cells) and all donors’ (n = 325,665 nuclei and cells, m = 18 donors) scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq data (b-e respectively) for all recovered cell states, coloured by coarse grain compartment annotation and metadata labels: assay, sample (10X library), donor and developmental age. (bottom) Dot plots show normalised, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of genes characteristic of coarse grain compartment (X-axis) in donors profiled (Y-axis). Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq), maternal (m), fetal (f), natural killer (NK), innate lymphocytes (ILC), single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq).

We examined trophoblast heterogeneity in two steps. First, we analysed the full-thickness implantation site from P13 (at around 9 PCW), as it contains both fetal (placenta) and maternal (decidua and myometrium) tissues on the same slide, and the tissue block is perfectly preserved and oriented (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 3a). Second, we validated the trophoblast populations and their markers in the integrated dataset (around 5–13 PCW) (Extended Data Fig. 3b,c). Trophoblast subsets were annotated by considering canonical markers and their spatial location (Fig. 1d–f and Extended Data Figs. 1e and 3d,e). To assign spatial coordinates we used cell2location17, our probabilistic method to deconvolve the spatial voxels using our pre-defined snRNA-seq data. We then placed the trophoblast cells into five pre-defined microenvironments (ME1–ME5) in the tissue based on manual histological annotation.

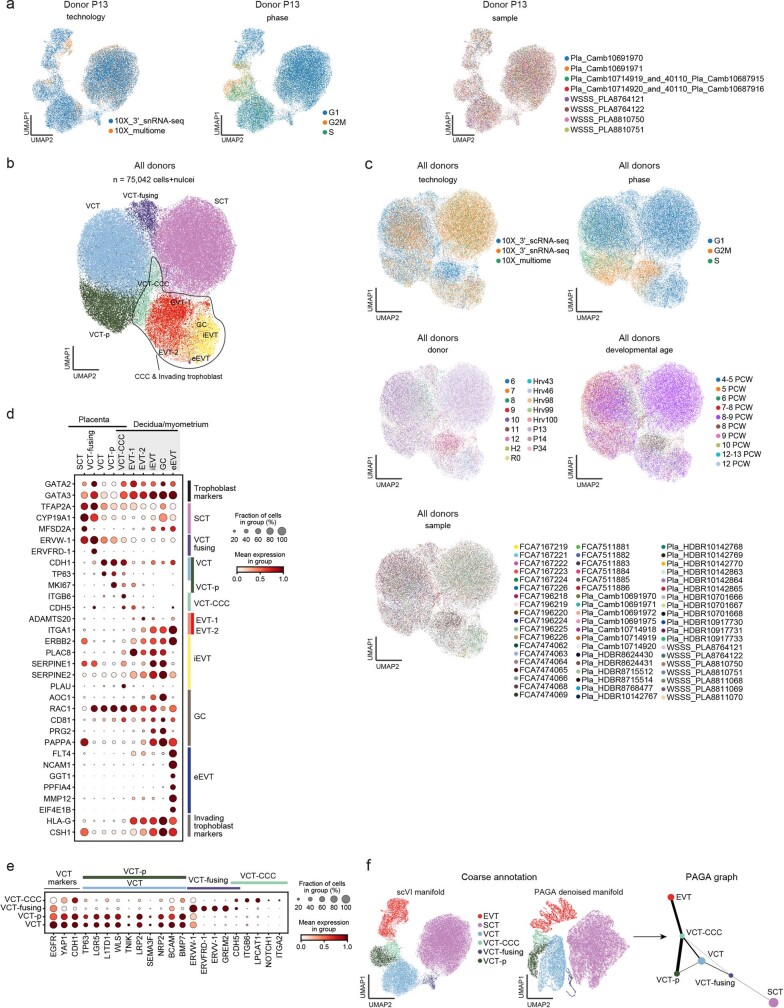

Extended Data Fig. 3. snRNA-seq and scRNA-seq trophoblast data analysis overview.

a: UMAP (uniform manifold approximation and projection) scatterplots of donor P13 snRNA-seq data (n = 37,675 nuclei) for all trophoblast cell states coloured by (from left to right) assay, cell cycle phase of the nuclei and sample (10X library). Please note: bioinformatics analyses used cannot distinguish between G0 and G1. b: UMAP scatterplot of integrated snRNA-seq and scRNA-seq of all donors’ (n = 75,042 nuclei and cells, m = 17 donors with trophoblast present) trophoblast cell states in the maternal-fetal interface coloured by cell state. c: UMAP scatterplots of all donors’ scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq data for all donors’ (n = 75,042 nuclei and cells, m = 17 donors with trophoblast present) trophoblast cell states coloured by assay, sample (10X library), cell cycle phase of the cells/nuclei, donor and developmental age. d: Dot plot showing normalised, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of genes (Y-axis) characteristic of trophoblast cell states (X-axis) in all donors (m = 17 donors with trophoblast present). e: Dot plot showing normalised, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of genes (X-axis) characteristic of VCT cell states (Y-axis) in all donors (m = 17 donors with trophoblast present). f: Results of PAGA trajectory inference of all trophoblast cell states in donor P13 snRNA-seq data. (left) main manifold, center: denoised PAGA manifold, (right) PAGA reconstruction of putative trajectory tree for all trophoblast cell states. For the purpose of this analysis all EVTs have been united in annotation under the ‘EVT’ label. Syncytiotrophoblast (SCT), villous cytotrophoblast (VCT), cytotrophoblast cell column (CCC), proliferative (p), extravillous trophoblast (EVT), interstitial EVTs (iEVTs), giant cells (GC), endovascular EVT (eEVT), single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq).

In the placental villi (ME1), villous cytotrophoblast (VCT) fuse to form the overlying SCT layer that is in contact with maternal blood in the intervillous space. VCT subsets express high levels of TP63 and CDH1 in the P13 donor (Fig. 1e) and all other donors (Extended Data Fig. 3d). VCT and VCT-proliferative (VCT-p) upregulate known stem and progenitor cell markers (LGR5, L1TD1 and TP63), Wnt signalling molecules (WLS and TNIK), the SEMA3F–NRP2 signalling complex and the VCT marker BCAM18 (Fig. 1f, Extended Data Fig. 3e). We define an additional population of VCT in the placental villi that we name VCT-fusing, which the connectivity network PAGA19 indicates is an intermediate cell state between VCT and SCT (Extended Data Fig. 3f). As VCT commit into VCT-fusing, they downregulate Wnt (WLS, TNIK and LGR5) and BMP signals (BMP7 and upregulation of BMP antagonist GREM2), and upregulate the endogenous retroviral genes (ERVW-1, ERVFRD-1, ERVV-1) known to mediate trophoblast fusion20 (Fig. 1f and Extended Data Fig. 3e). Our strategy for isolation of nuclei enables the capture of mature multinucleated SCTs (expressing CYP19A1 and MFSD2A), which were not found in previous scRNA-seq studies13,21 (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 3d).

Soon after implantation, foci of cytotrophoblast cell columns (CCCs) arise from the VCTs that break through the SCT. These expand and form a shell around the conceptus that becomes discontinuous in the following weeks. EVTs begin to differentiate in cell columns but invasive EVTs emerge only when the anchoring villi attach to the maternal decidua. In the trophoblast shell (ME2), we define an additional population of CCC VCT (VCT-CCC) (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1e). VCT-CCCs are proliferative and PAGA analysis shows they are likely to emerge from VCT or VCT-p and give rise to EVTs (Extended Data Fig. 3f). This analysis confirms that VCT is a common progenitor for both VCT-fusing, giving rise to SCT, and VCT-CCC where EVTs emerge. As they commit to become VCT-CCCs, they downregulate the Wnt pathway (WLS, TNIK and LGR5 expression), upregulate NOTCH1, undergo an integrin shift (upregulating ITGB6 and ITGA2), and upregulate markers characteristic of epithelial–mesenchymal transition22 (LPCAT1) (Fig. 1f and Extended Data Fig. 3e). Expression of NOTCH1 and ITGA2 is characteristic of putative trophoblast progenitor cells located in a small niche in the CCC23,24. In agreement with this finding, in ME2, VCT-CCCs co-localize with EVTs (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1e).

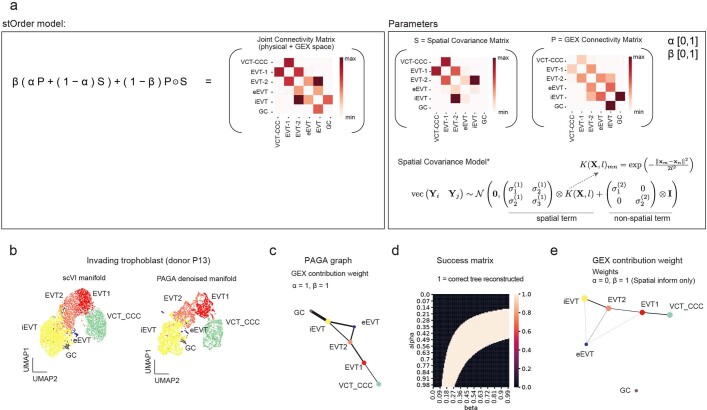

Trajectories of EVT defined by StOrder

To further investigate the EVT differentiation pathway as it arises from the CCCs of the anchoring villi to infiltrate maternal tissue, we leveraged both spatial and single-cell transcriptomics data using a three-step statistical framework, which we named StOrder (Extended Data Fig. 4a and Methods). First, StOrder builds a gene expression-based connectivity matrix (generated in our case by PAGA19) to establish putative connections between clusters (Extended Data Fig. 4b). The values in this matrix are interpreted as pairwise similarity scores for cell states in the gene expression space. Second, StOrder generates a spatial covariance matrix that reflects the pairwise proximity of trophoblast states that co-exist in space. To do so, StOrder takes as an input the estimated cell densities per spot (derived in our case with cell2location17) in Visium spatial transcriptomics data, and fits a Gaussian process model that derives pairwise spatial covariance scores for all the cell state pairs (Extended Data Fig. 4a). This enables inference of which cell states are proximal in physical space and are probably gradually differentiating as they migrate. Third, StOrder reconstructs connections between cell states by combining the connectivity matrix (step 1) from single-cell transcriptomics data and the spatial covariance matrix (step 2) from the spatial data in a weighted manner (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 4a–e). In sum, StOrder reconstructs the likely cell transitions in space by taking into account both the single-cell transcriptomics and the mini-bulk spatial transcriptomics data.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Analysis of extravillous trophoblast invasion trajectory using stOrder.

a: Schematic overview of StOrder approach representing the workflow of joint cell differentiation trajectory inference from gene expression and spatial transcriptomics data (See methods). b: (Left) Main UMAP (uniform manifold approximation and projection) scatterplot and (right) denoised manifold used for PAGA trajectory inference of all trophoblast cell states in donor P13 single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) data. c: PAGA reconstruction of putative trajectory tree for all extravillous trophoblast cell states. This corresponds to the trajectory tree inferred by stOrser with α = 1, β = 1 parameters from donor P13 snRNA-seq data and spatial transcriptomics data of donors P13 (5 capture areas), P14 (2 capture areas) and Hrv43 (1 capture area). d: Heatmap of binary success matrix of stOrder approach for pairs of (α,β), values (along Y and X axes, respectively). Assigned matrix value is 1 if a tree of correct topology has been reconstructed for that pair of (α,β) values, and 0 if no tree of correct topology was reconstructed. e: Reconstruction of putative invading trophoblast trajectory tree based solely on spatial data inferred by stOrder with α = 0, β = 1 parameters from donor P13 snRNA-seq data and spatial transcriptomics data of donors P13 (5 chips), P14 (2 chips) and Hrv43 (1 chip). Villous cytotrophoblast (VCT), cytotrophoblast cell column (CCC), extravillous trophoblast (EVT), interstitial EVTs (iEVTs), giant cells (GC), endovascular EVT (eEVT).

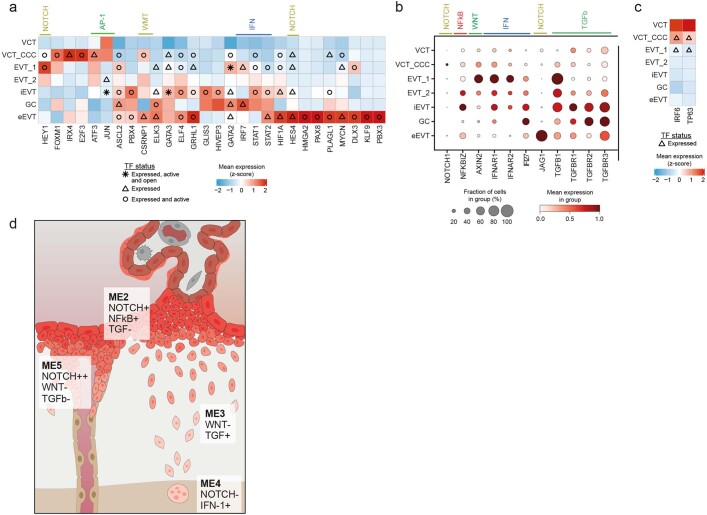

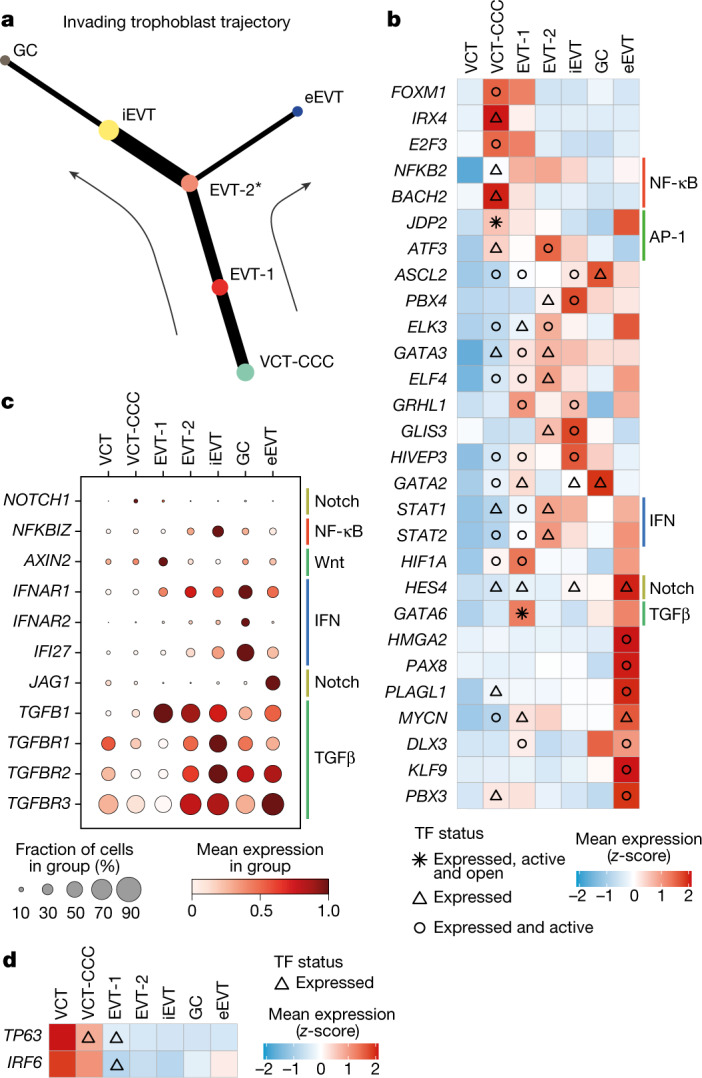

Fig. 2. Transcription factors that are active during EVT invasion.

a, Representative tree of EVT differentiation trajectory inferred by StOrder (Methods). The tree shown is inferred with α = 0.4 and β = 0.5 for snRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics data from donors P13 (5 capture areas), P14 (2 capture areas) and Hrv43 (1 capture area). Tree edge thickness is proportional to connectivity (joint measure inferred from snRNA-seq data and spatial transcriptomics data) between two cell types connected by that edge. The asterisk indicates the bifurcation point. b, Heat map showing z-scores of normalized, log-transformed and scaled expression of transcription factor (TF) genes upregulated during trophoblast invasion in donor P13 snRNA-seq data. The x-axis indicates cell state, the y-axis lists transcription factors. Differential expression (upregulated genes) is tested along the invading trophoblast trajectory (as shown in a) in a retrograde manner using the limma approach (false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05, with Bonferroni correction for multiple hypotheses testing). Coloured bars to the right of heat map indicate members of selected pathways. IFN, interferon. c, Dot plot showing normalized, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of genes (x-axis) of signalling molecules upregulated in EVT (y-axis) in donor P13 snRNA-seq data. d, Heat map showing z-score of normalized, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of transcription factors (x-axis) downregulated during trophoblast invasion in P13 in trophoblast states (y-axis). Differential expression (downregulated genes) is tested along invading trophoblast trajectory (as shown in a) in a retrograde manner using the limma approach (FDR < 0.05, with Bonferroni correction for multiple hypotheses testing).

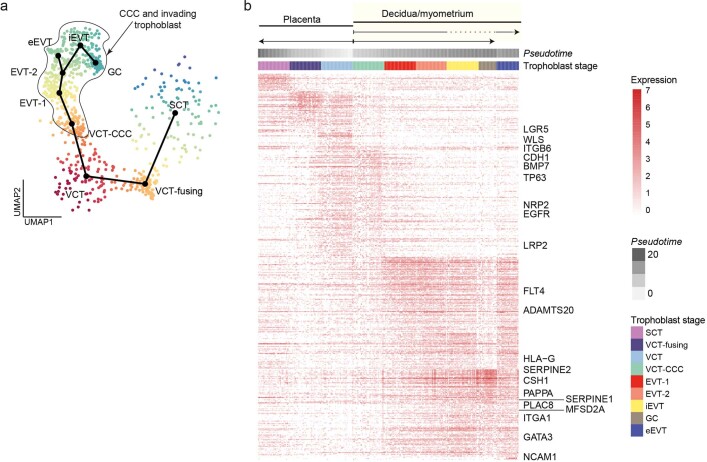

StOrder enabled us to resolve the most likely trajectory for the emergence and differentiation of invasive EVTs (Fig. 2a). Consistent trajectories were obtained when reconstructing pseudotime on snRNA-seq data using Slingshot25 (Extended Data Fig. 5a). We then calculated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) along the three trophoblast trajectories with different end points: (1) eEVT, (2) GC and (3) SCT (Extended Data Fig. 5b and Supplementary Table 5). VCT-CCCs are the precursors of EVTs-1 and EVTs-2 and co-localize with them in ME2 (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1e). EVTs-1 are proliferative while EVTs-2 do not proliferate and upregulate the metalloprotease gene ADAMTS20 and the integrin subunit gene ITGA1 (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 3d). EVTs-2 are located at the distal end of the anchoring villi, and are identified as the bifurcation point between eEVTs and interstitial EVTs (iEVTs) (Figs. 1d and 2a). Thus, EVTs-2 can transition either into iEVTs that invade through decidual stroma, or into eEVTs that move down inside the arteries.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Analysis of extravillous trophoblast invasion trajectory using Slingshot.

a: Minimum spanning tree of donor P13 trophoblast single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) data computed by Slingshot, visualised on the UMAP (uniform manifold approximation and projection) embedding of P13 donor trophoblast cells from Fig. 1c (n = 37,675 nuclei). Bigger black dots indicate trophoblast states. Smaller dots’ colour indicates pseudotime. b: Heatmap showing normalised and log-transformed expression values of the 567 genes associated with trophoblast pseudotime, estimated with tradeSeq (p-value < 1x10-6 and mean LogFC > 0.5). Cells in rows are sorted according to the predicted pseudotime. Genes are sorted according to the trophoblast state where gene expression peaks. Marker genes are highlighted. Syncytiotrophoblast (SCT), villous cytotrophoblast (VCT), cytotrophoblast cell column (CCC), extravillous trophoblast (EVT), interstitial EVTs (iEVTs), giant cells (GC), endovascular EVT (eEVT).

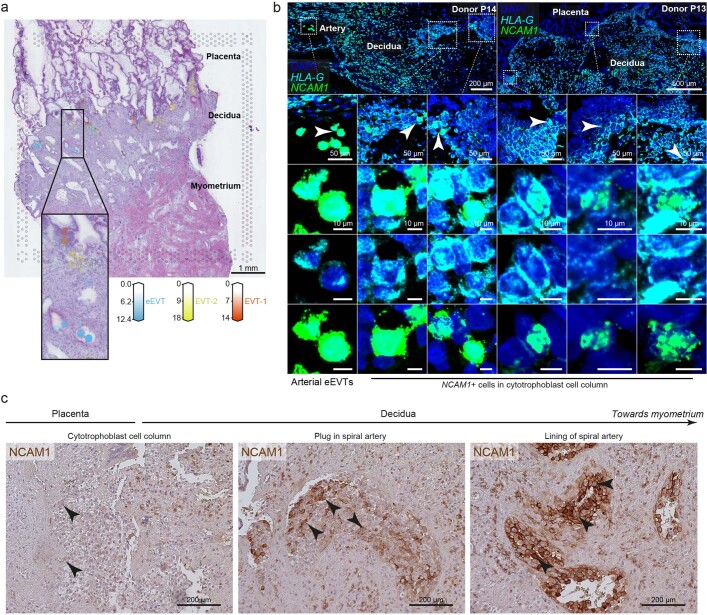

eEVTs are present inside spiral arteries (ME5) (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1e). Besides NCAM126,27, eEVTs also upregulate GGT1, PPFIA4 and MMP12 (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 3d). Evidence that eEVTs emerge from the distal end of the CCC is supported by their close proximity to EVTs-2 (Extended Data Fig. 6a). In our samples, we detect sporadic NCAM1+ cells close to the cytotrophoblast shell when it is overlying a spiral artery, by single-molecule fluorescent in situ hybridisation (smFISH) (Extended Data Fig. 6b). Immunohistochemistry confirms our previous findings26,27 that cells in the CCC do not stain with a monoclonal antibody to NCAM1, but there are scattered positive cells in the plug of eEVTs beneath this column. In a more proximal portion of the same artery all the eEVTs lining the artery are NCAM1+ (Extended Data Fig. 6c).

Extended Data Fig. 6. Histological characterisation of eEVTs.

a: Estimated amount of mRNA computed by cell2location (colour intensity) contributed by each cell population to each spot (colour) shown over the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) image of donor P13 implantation site (n = 1). b: (Top) High-resolution imaging of sections of the placenta-decidua interface from two donors (n = 2, donor ID is indicated in each panel), stained by multiplexed single molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) for HLA-G and NCAM1; dashed squares indicate areas shown magnified below. (Middle) magnified insets highlight an artery containing aggregating eEVTs (left) and cytotrophoblast cell columns; in the latter, solid arrows indicate sporadic nascent NCAM1+ cells shown magnified below (bottom). c: Expression of NCAM1 (marker of eEVT) with IHC in first-trimester decidual tissue. Nuclei are counterstained with hematoxylin. Representative images from three different donors (n = 3).

Highly invasive iEVTs are found in ME3, surrounded by decidual stromal and immune cells (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1e). iEVTs upregulate PLAC828 and plasminogen activator inhibitor genes SERPINE1 and SERPINE2, with concomitant downregulation of the plasminogen activator gene PLAU (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 3d). iEVTs eventually fuse to form placental bed GCs deeper in the decidua and myometrium (ME4) (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 1e). GCs upregulate RAC1 and CD81, and the PRG2–PAPPA complex29 (Fig. 1d,e, Extended Data Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 3c).

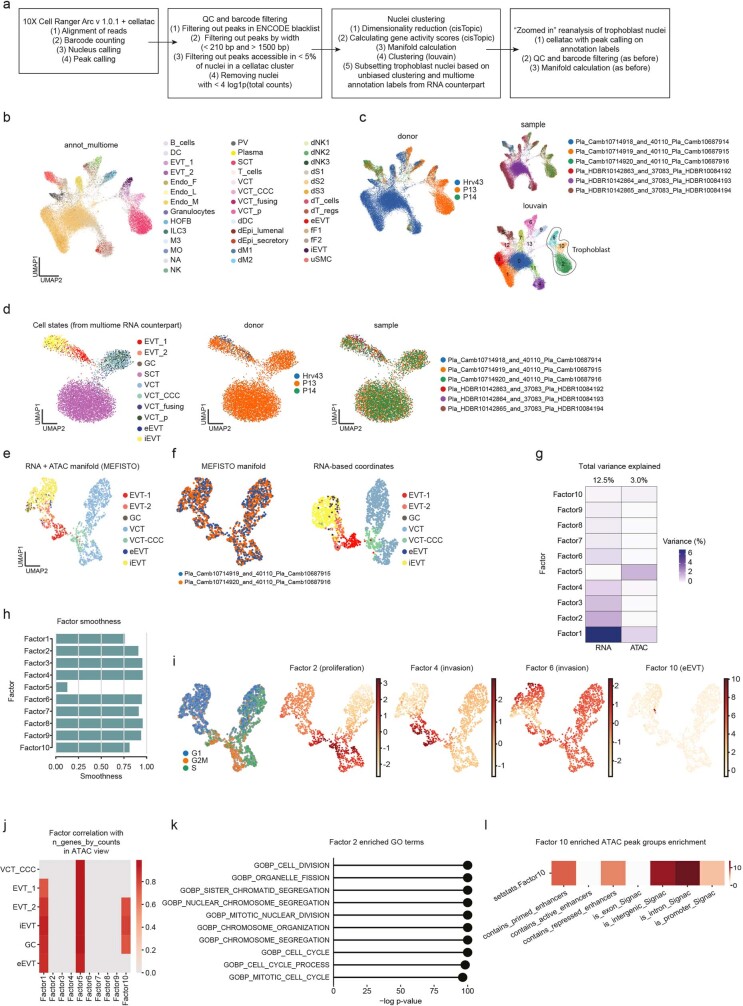

We next explored the regulatory programmes that might mediate EVT invasion by analysing the multimodal RNA-seq and ATAC–seq data (Extended Data Fig. 7a–c). We applied our multifactorial method MEFISTO30 to donor P13 multimodal data, which contained the full spectra of VCT and EVT subsets (Extended Data Fig. 7d–f). MEFISTO identified 10 latent factors that jointly explain 12.5% of the variance in the RNA expression data and 3% of the chromatin accessibility data (Extended Data Fig. 7g,h). Using a logistic regression approach, we define factors 2, 4, 6 and 10 as the main driving factors of the trophoblast trajectory (Extended Data Fig. 7i–l). Factors 2, 4 and 6 explain changes along the main interstitial trophoblast invasion pathway (VCT-CCC to GC) (Supplementary Table 4). Genes contributing strongly to these factors are MKI67, CENPK (cell cycle, factor 2); CSF1R, ADAM8 and LAIR2 (early trophoblast invasion, factor 4); CALD1 and COL21A1 (late trophoblast invasion, factor 6). Factor 10 captured eEVTs; the main genes contributing to this factor include NCAM1, JAG1, ADORA1, EPHA1 and HES4.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Multimodal analysis of extravillous trophoblast invasion.

a: Overview of the computational pipeline implemented for analysis of multimodal data. b-c: UMAP (uniform manifold approximation and projection) scatterplot of multimodal snATAC-seq data from donors P13, P14 and Hrv43 (n = 52,798 nuclei) coloured by cell state (b), donor, sample (10X library) or unbiased clustering labels (c). Data is annotated based on the corresponding single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) cell state assignment. d: UMAP scatterplot of integrated multimodal single-nuclei ATAC sequencing (snATAC-seq) data for trophoblast only from donors P13, P14 and Hrv43 (n = 7449 nuclei) coloured by cell state, donor and sample (10X library). e: UMAP scatterplot of multiome (snRNA-snATACseq) data of invading trophoblast cells from donor P13 (n = 1605 nuclei) coloured by cell state. The manifold is calculated based on dimensionality reduction performed by MEFISTO (model with n = 9 factors). f: (Left) UMAP scatterplot of multiome (snRNA-snATACseq) data of invading trophoblast cells from donor P13 (n = 1605 nuclei) coloured by sample. The manifold is calculated based on dimensionality reduction performed by MEFISTO (model with n = 9 factors). (Right) Scatterplot of UMAP coordinates obtained from the RNA expression data that were used as covariates for MEFISTO, coloured by cell state. g: Heatmap representing percentage of variance explained by each MEFISTO factor in each data modality. h: Smoothness along differentiation estimated with MEFISTO. i: UMAP scatterplot of multiome (snRNA-snATACseq) data of invading trophoblast cells from donor P13 (n = 1605 nuclei) coloured by cell cycle phase and MEFISTO factor values for important selected factors. j: Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients of each latent factor learned with MEFISTO and the number of genes per counts in snATAC-seq data (multiome). k: Gene set (RNA) enrichment analysis overview of MEFISTO factor 2 using two-sided parametric t-test, FDR is used to rank gene sets. l: Peak set (ATAC) enrichment analysis overview of MEFISTO factor 10 using two-sided parametric t-test, FDR is used to rank peak sets. Villous cytotrophoblast (VCT), cytotrophoblast cell column (CCC), proliferative (p), extravillous trophoblast (EVT), interstitial EVTs (iEVTs), giant cells (GC), endovascular EVT (eEVT), dendritic cells (DC), lymphatic (l), maternal (m), fetal (f) Hofbauer cells (HOFB), innate lymphocytes (ILC), macrophages (M), monocytes (MO), natural killer (NK), perivascular (PV), decidual (d), epithelial (epi), stromal (S), fibroblasts (F), uterine smooth muscle cells (uSMC).

Transcription factors in EVT subsets

To identify the major regulatory programmes driving EVT differentiation, we extracted the transcription factors that are differentially expressed and active along the EVT differentiation trajectory (Supplementary Table 6 and Methods). Activation of the FOXM1–NOTCH1 axis is likely to lead to the differentiation of VCTs into VCT-CCCs (Fig. 2b,c and Extended Data Fig. 8a,b). Upregulation of NOTCH1 may trigger the downregulation of IRF6 and TP63 expression in trophoblast23,31 (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 8c). VCT-CCCs upregulate NF-κB pathway genes (NFKB2 and BACH2) and modulate AP-1 signalling genes (JDP2 and ATF3), which may result in epithelial–mesenchymal transition (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 8a). Activation of the NF-κB pathway is maintained throughout EVT differentiation (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 8a), but there is upregulation of the NF-κB inhibitor (NFKBIZ) at the iEVT stage (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 8b). This could be another mechanism to avoid inflammation as EVTs invade13,32.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Transcription factors active in extravillous trophoblast cell states (all donors).

a: Heatmap showing z-score of normalised, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of transcription factors (TFs) upregulated during trophoblast invasion in all donors (n = 17 donors with trophoblast present). Y-axis indicates cell state, X-axis lists TFs. Differential expression (upregulated genes) is tested along invading trophoblast trajectory (as shown in Fig. 2a) in a retrograde manner using limma approach (FDR < 0.05, with Bonferroni correction for multiple hypotheses testing. b: Dot plot showing normalised, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of genes (X-axis) of signalling molecules upregulated in EVT (Y-axis) in all donors (n = 17 donors with trophoblast present). c: Heatmap showing z-score of normalised, log-transformed and scaled expression of TFs downregulated during trophoblast invasion in all donors (n = 17 donors with trophoblast present). Y-axis indicates cell state, X-axis lists TFs. Differential expression (downregulated genes) is tested along invading trophoblast trajectory (as shown in Fig. 2a) in a retrograde manner using limma approach (FDR < 0.05, with Bonferroni correction for multiple hypotheses testing). d: Schematic representation of signalling pathways in distinct spatial microenvironments. Villous cytotrophoblast (VCT), cytotrophoblast cell column (CCC), extravillous trophoblast (EVT), interstitial EVTs (iEVTs), giant cells (GC), endovascular EVT (eEVT), microenvironment (ME), transcription factors (TFs).

Invading EVTs intermingle with stromal and immune cells in the decidua. Decidual stromal cells secrete the Wnt inhibitor DKK133 and EVT invasion is characterized by inhibition of Wnt, with downregulation of the Wnt target AXIN2 (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 8b). As they invade, iEVTs upregulate the transcription factor ASCL234, other transcription factors involved in cancer invasion (ELK3–GATA3 complex35), as well as tumour suppressor genes (GRHL1) (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 8a). This is in keeping with iEVTs being non-proliferative. As iEVTs transition into GCs, they upregulate receptors of the type I interferon pathway (IFNAR1 and IFNAR2) and its targets (IFI27) (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 8b).

The eEVTs interact with endothelial cells, which they replace, and constituents of maternal blood. eEVTs have a unique pattern of transcription factor genes, which include HMGA2, PAX8, PLAGL1, MYCN and PBX3 (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 8a). In addition, eEVTs upregulate Notch signalling (HES4 and JAG1) and the expression of TGFβ signalling genes (TGFB1, TGFBR1 and TGFBR2) is lower than in iEVT (Fig. 2c,d and Extended Data Fig. 8a,b). GATA6, which is known to affect vessels by suppressing autocrine TGFβ signalling36, is always upregulated and active in EVT-1 and maintains its high expression in eEVTs, as opposed to iEVTs. In summary, eEVT identity is marked by strong upregulation of Notch signalling and downregulation of TGFβ signalling, whereas iEVT cell fate is characterized by TGFβ upregulation and Wnt inhibition (Extended Data Fig. 8d).

Benchmarking of trophoblasts in vitro

We next explored whether the cell-intrinsic regulatory programmes that are triggered upon VCT-to-EVT differentiation are also present in EVTs derived from both self-renewing PTOs3 and TSCs5. To do so, we performed scRNA-seq on: (1) PTOs differentiated in the presence of EVT medium (EVTM) (PTO-EVTM). PTOs grown in trophoblast organoid medium (TOM) (PTO-TOM) are used as controls; (2) TSCs differentiated in the presence of EVTM (TSC-EVTM). Here TSCs in trophoblast stem cell medium (TSCM) (TSC-TSCM) are used as controls (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 9a). In addition, to capture multinucleated SCT, we performed snRNA-seq on organoids grown in TOM and derived from both (3) PTOs and (4) TSCs (Extended Data Fig. 9a). We annotated the in vitro data using canonical trophoblast markers, transferring labels from the in vivo dataset into the in vitro dataset and integrating both in vivo and in vitro datasets on the same manifold (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Figs. 9b–l and 10a–e).

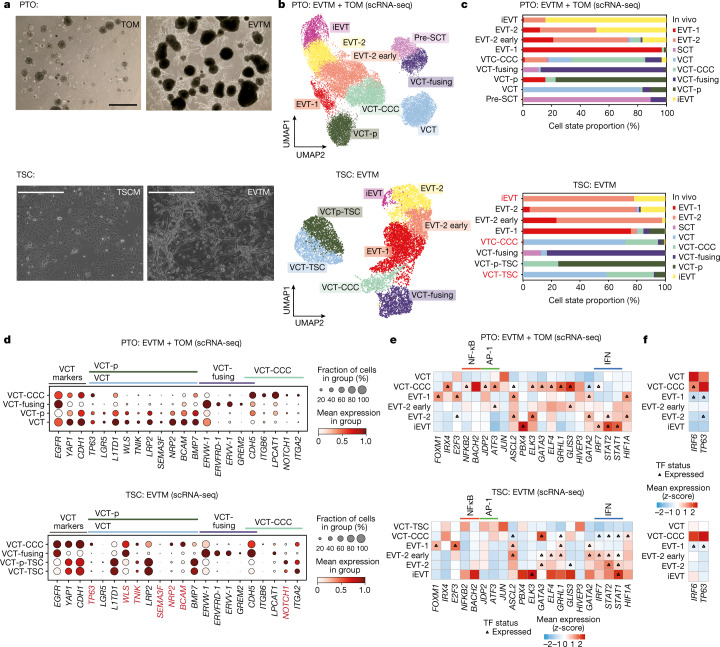

Fig. 3. Benchmark of EVTs derived from primary-derived trophoblast organoids and TSCs.

a, Top, phase-contrast images of PTOs plated in a Matrigel droplet and exposed to TOM or EVTM. Scale bar, 1 mm. Representative image of n = 6 experiments. Below, phase-contrast images of TSCs exposed to TSCM or EVTM. Scale bar, 400 μm. Representative image of n = 2 experiments. b, UMAP plot of PTO (n = 26,852 cells) and TSC (n = 9957 cells) scRNA-seq data coloured by cell state. Annotation was performed as indicated in Extended Data Fig. 9b. c, Bar plot representing the proportion (%) of cell states assigned to the in vitro cell states (defined by markers) using a logistic regression classifier trained on the in vivo data. Red text indicates cell states that differ between the annotations given by the logistic regression classifier and the ones given by the expression of canonical markers. d, Dot plot showing normalized, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of genes (x-axis) characteristic of VCT y-axis in PTOs (top) and TSCs (bottom). Red text indicates genes that differ from the in vivo observed expression pattern. e, Heat map showing z-scores of normalized, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of transcription factor genes that are known to be upregulated in in vivo trophoblast invasion (see Fig. 2b). The y-axis indicates cell state and the x-axis shows transcription factor genes. f, Heat map showing z-scores of normalized, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of transcription factor genes that are known to be downregulated in in vivo trophoblast invasion.

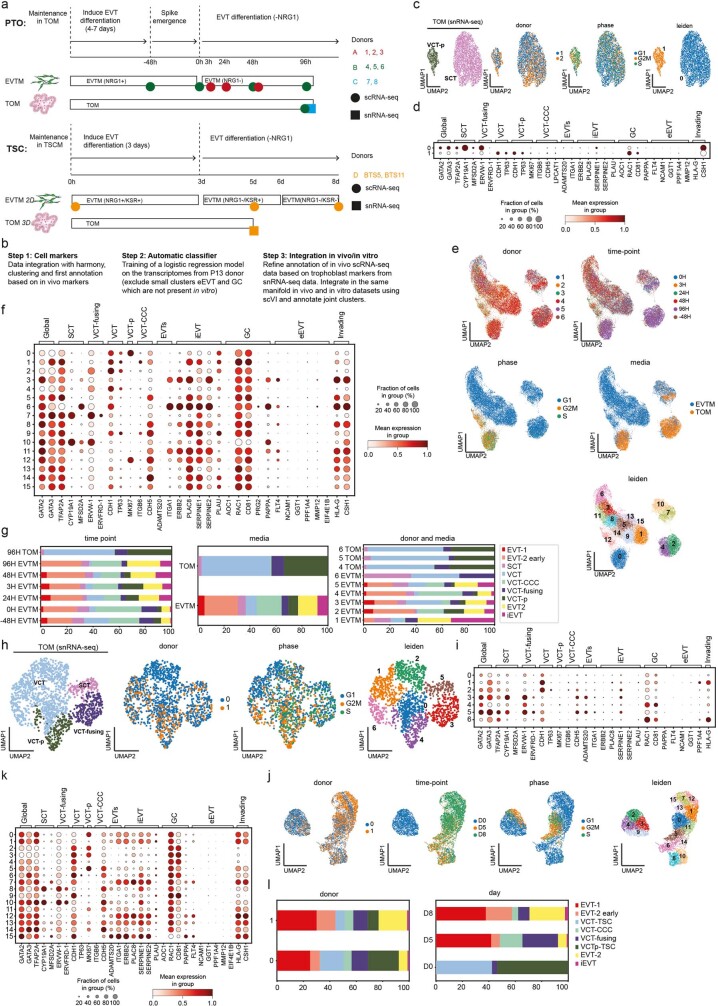

Extended Data Fig. 9. scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq data quality control and analysis overview of the trophoblast in vitro models.

a: Schematic representation of the extravillous trophoblast (EVT) differentiation experimental design, indicating time points and biological replicates in both primary trophoblast organoids (PTO, n = 6 scRNA-seq and n = 2 for snRNA-seq) and trophoblast stem cell (TSC, n = 2 for both scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq) models. b: Diagram showing the annotation of the in vitro models. Firstly, we analysed the datasets in four separate manifolds and annotated each of the cell states based on canonical markers. Secondly, we projected the trophoblast in vivo reference data onto the in vitro trophoblast subsets by building a logistic regression classifier that we trained on P13 snRNA-seq in vivo dataset. We excluded eEVT and GC cells as these are scarcely represented and our marker data show they are not present in the in vitro cultures. Thirdly, we integrated scRNA-seq data from in vivo and in vitro conditions using scVI, and used this manifold to calculate differentially expressed genes (DEG) amongst subsets. c: UMAP (uniform manifold approximation and projection) scatterplots of snRNA-seq (n = 3928 nuclei) of PTOs coloured by cell state, donor (n = 2 donors), cell cycle phase and unbiased clustering using leiden. Sample integration was performed with Harmony. d: Dot plot showing normalised, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of genes (X-axis) of main trophoblast subsets (Y-axis) in each of the clusters identified by unbiased clustering (a) in snRNA-seq of primary trophoblast organoids (PTOs). e: UMAP scatterplots of scRNA-seq of PTOs derived from n = 6 donors and coloured by donor, time-point, cell cycle phase, media cultured and unbiased clustering using leiden. f: Dot plot showing normalised, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of genes (X-axis) of main trophoblast subsets in each of the clusters identified by unbiased clustering (c) in scRNA-seq of PTOs (Y-axis). g: Bar plots showing the proportion (%) of final cell states identified in data of each time point (left), media (center) and donor (right) for PTOs scRNA-seq. h: UMAP scatterplots of snRNA-seq (n = 1563 nuclei) of trophoblast organoids from trophoblast stem cells (TSC) coloured by cell state, donor, cell cycle phase and unbiased clustering using leiden. Sample integration was performed with Harmony. i: Dot plot showing normalised, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of genes (X-axis) of main trophoblast subsets (Y-axis) in each of the clusters identified by unbiased clustering (f) in snRNA-seq of trophoblast stem cells (TSC). j: UMAP scatterplots of scRNA-seq of EVT derived from TSC coloured by donor, time-point, cell cycle phase and unbiased clustering using leiden. k: Dot plot showing normalised, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of genes (X-axis) of main trophoblast subsets in each of the clusters identified by unbiased clustering (j) in scRNA-seq of trophoblast stem cells (TSC) (Y-axis). l: Bar plots showing the proportion (%) of final cell states identified in each donor’s data (left) and time-point (right) for TSCs scRNA-seq. Trophoblast organoid media (TOM), syncytiotrophoblast (SCT), villous cytotrophoblast (VCT), cytotrophoblast cell column (CCC), proliferative (p), extravillous trophoblast (EVT), EVT media (EVTM), interstitial EVT (iEVT), giant cells (GC), endovascular EVT (eEVT), single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq).

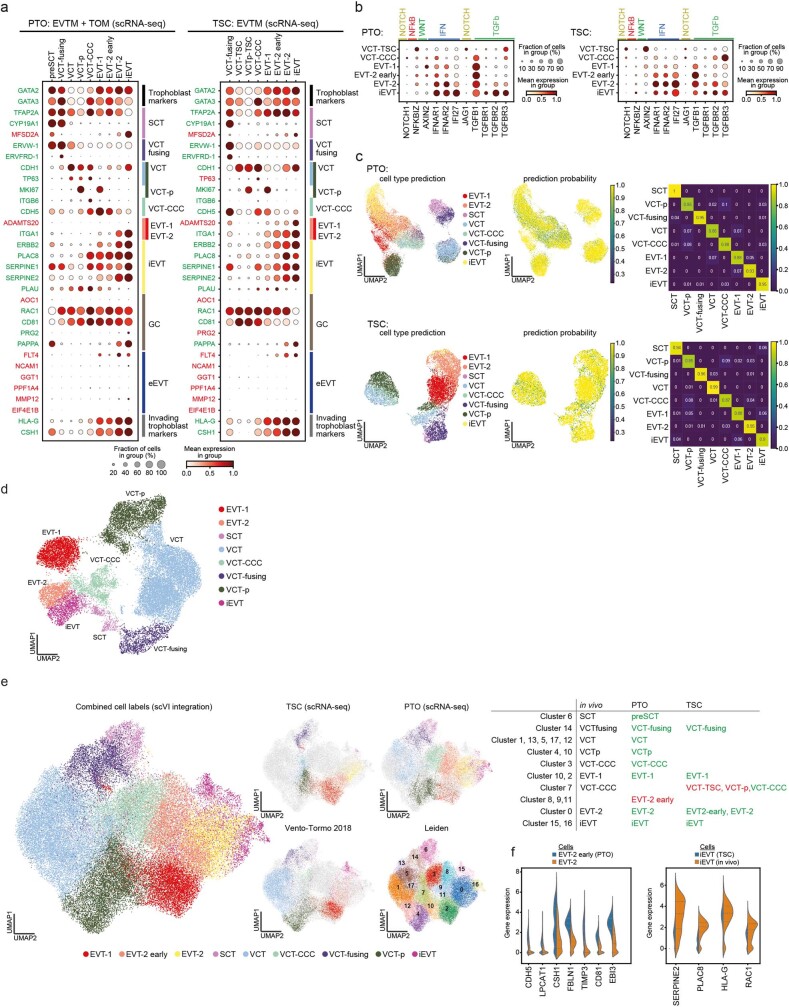

Extended Data Fig. 10. Annotation and benchmark of trophoblast in vitro models.

a: Dot plots showing normalised, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of genes (Y-axis) characteristic of trophoblast cell states (X-axis) in primary trophoblast organoids (PTO, left) and trophoblast stem cell (TSC, right) models. Marked in red are genes that differ from the in vivo observed expression pattern. b: Dot plot showing normalised, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of genes (X-axis) of signalling molecules known to be upregulated in in vivo trophoblast invasion plotted in trophoblast organoids (Y-axis). c: UMAP (uniform manifold approximation and projection) scatterplot of PTO single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq data, n = 26,853 cells) coloured by predicted cell state (top left) and probability (top center) according to our logistic regression model. Only in vivo data from donor P13 (snRNA-seq) was considered for the training. Confusion matrix with predictions on test set based on common features with PTO (Top right). UMAP scatterplot of TSC scRNA-seq data (n = 9957 cells) coloured by predicted cell state (bottom left) and probability (bottom center) according to our logistic regression model. Only in vivo data from donor P13 (snRNA-seq) was considered for the training. Confusion matrix with predictions on test set based on common features with TSC (Bottom right). d: UMAP scatterplot of scRNA-seq data (n = 23,519 cells) from13 re-annotated using markers from Fig. 1e. e: (Left and center) Integrated manifold (in vivo and in vitro) using scVI and coloured by cell state and specific conditions. Integration is performed with scVI. (Top right) Table displaying organoid-independent annotation for each scVI-integrated cluster. Organoid annotation matching in vivo labels displayed in green, discordant annotation in red. f: Violin plot showing normalised and log-transformed expression of differentially expressed genes (DEGs, limma, FDR < 0.05, with Bonferroni correction for multiple hypotheses testing) when comparing early EVT-2 in PTO vs in vivo EVT-2. (Right) Violin plot showing normalised and log-transformed expression of DEG when comparing iEVT in TSC vs in vivo iEVT. Primary trophoblast organoids (PTO), trophoblast stem cells (TSC), trophoblast organoid media (TOM), syncytiotrophoblast (SCT), villous cytotrophoblast (VCT), cytotrophoblast cell column (CCC), proliferative (p), extravillous trophoblast (EVT), interstitial EVT (iEVT), giant cells (GC), endovascular EVT (eEVT).

Projection of in vivo data onto in vitro trophoblasts using a logistic regression classifier that we trained on the in vivo dataset showed that VCT heterogeneity is better recapitulated in PTOs than in TSCs (Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 10b). The four VCT subsets defined in vivo are present in PTOs and they express the same canonical markers (Fig. 3d). In PTOs, VCT-CCCs are enriched in the presence of EVTM, which triggers upregulation of the FOXM1–NOTCH1 axis, NF-κB (NFKB2 and BACH2) and AP-1 modulators ( JDP2 and ATF3) (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 10d). By contrast, bona fide VCTs are not found among TSCs (Fig. 3c). Instead, when grown in TSCM, cells that we call ‘trophoblast stem cells’ (VCT-TSC) are primed to become VCT-CCCs as they upregulate VCT-CCC markers (NOTCH1 and ITGA2) and downregulate some of the canonical VCT markers (TP63, WLS, TNIK, SEMA3F, NRP2 and BCAM) (Fig. 3d). In both TSCs and PTOs, VCT-CCCs (CDH5, ITGB6 and LCAT1) are enriched in the presence of EVTM media, which triggers the NOTCH–FOXM1 axis, leading to a further downregulation of IRF6 and TP6323,31 in EVT-1 (Fig. 3e,f). VCT-fusing is present in both PTOs and TSCs and accurately recapitulates its in vivo counterparts (Fig. 3c,d). snRNA-seq allowed us to capture mature SCT in PTOs (Extended Data Fig. 9d), and SCT in TSCs do not express MFSD2A (Extended Data Fig. 9i). Thus, our results highlight that the VCT subsets are accurately recapitulated in PTO, whereas bona fide VCTs are not found in TSCs.

VCT-CCCs in both PTOs and TSCs give rise to invasive EVT (EVT-1, EVT-2 early, EVT-2 and iEVT), whereas markers characteristic of GCs (high expression of PRG2 and AOC1) and eEVT (FLT4, NCAM1, GGT1, PPFIA4, MMP12 and EIF4E1B) are absent in our cultures (Extended Data Fig. 10a). Despite a good representation of almost all trophoblast subsets in both in vitro models, the relative proportion and efficiency of EVT differentiation was variable (Extended Data Fig. 9g,l). Similar to in vivo EVTs, EVTs derived from PTOs or TSCs downregulate the Wnt signalling pathway (AXIN2), upregulate members of the TGFβ signalling pathway (TGB1, TGBR1 and TGFBR2) and express EVT markers (ITGA1, PLAC8 and HLA-G) (Extended Data Fig. 10a,b). Markers of deep EVT invasion (ERBB2, SERPINE1, SERPINE2 and PAPPA) are upregulated in iEVTs generated in PTOs or in TSCs. However, some differences in EVT states are found between in vivo and the two in vitro trophoblast models. For PTO there is an expansion of VCT-CCCs and an early EVT-2 that upregulates markers of both VCT-CCCs (CDH5 and LPCAT1) and EVTs (CSH1, FBLN1, TIMP3, CD81 and EBI3) when compared to in vivo EVT-2 (Extended Data Fig. 10d–f). By contrast, TSC captures an early iEVT state that is assigned as EVT-2 by our logistic regression model despite upregulating iEVT markers (Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 10a,c). In line with this, TSC-iEVT-early clusters together with in vivo iEVTs but expresses lower levels of invasive markers (SERPINE2, PLAC8, HLA-G and RAC1) than its in vivo counterparts (Extended Data Fig. 10d–f). Altogether, major EVT invasion programmes are conserved in both PTOs and TSCs, yet there is an expansion of an early EVT population (EVT-2 early) in PTO and a less mature iEVT-like cluster is found in TSCs. The absence of deep invasive GCs and eEVTs in these cultures suggests that maternal cues present in vivo, specifically factors from the decidual stroma or maternal arteries and blood, respectively, are essential for generating these EVT end points.

Maternal cells and EVT differentiation

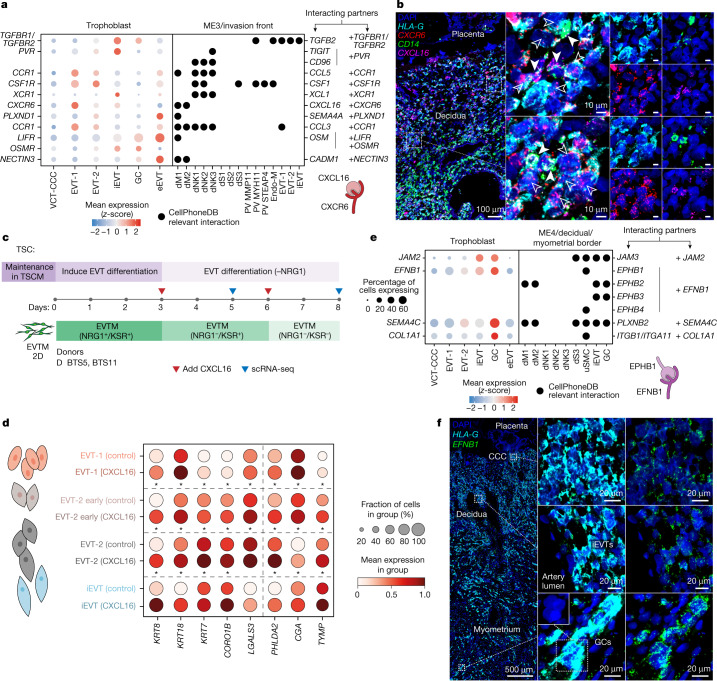

We integrated single-cell and single-nuclei transcriptomics data from 18 donors to study how decidual maternal cells affect trophoblast invasion (Extended Data Figs. 1c, 2e and 11a). We used CellPhoneDB v437 to determine the ligand–receptor interactions that are enriched in the four decidual microenvironments (Fig. 1a and Methods). We first focused on interactions mediating trophoblast invasion (Fig. 4a). As previously described13, decidual natural killer (dNK) cells interact with EVTs through multiple ligand–receptor pairs (PVR–TIGIT, PVR–CD96, CCR1–CCL5 and CSF1R–CSF1). We find that the majority of these receptors are upregulated in EVT-2, near the CCCs (Fig. 4a). In this location, the CSF1–CSF1R interaction is enriched, confirming previous findings13,38, and we reinforce this result using high-resolution multiplexed smFISH, which shows the close proximity of CSF1+ dNK cells and CSF1R+ EVT cells (Extended Data Fig. 11b).

Extended Data Fig. 11. Predicted interactions between trophoblast and maternal immune cells.

a: UMAP (uniform manifold approximation and projection) scatterplot of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) data of the 18 donors described in Extended Data Fig. 1c of the maternal-fetal interface (n = 325,665 cells and nuclei) coloured by cell state. Integration was performed with scVI. b: (Left) High-resolution imaging of a section of the placenta-decidua interface stained by smFISH for HLA-G, highlighting EVTs invading the decidua from the CCC. (Right) multiplexed co-staining with NCAM1 (dNK marker), CSF1 and cognate receptor CSF1R; dashed squares indicate areas shown magnified to right. (Bottom) solid and outlined arrows indicate neighbouring CSF1R-expressing EVTs and CSF1-expressing dNK cells, respectively. Representative image of samples from three donors. c: Dot plot showing normalised, log-transformed and variance-scaled gene expression of macrophage markers (X-axis) in data from (a) (Y-axis). d: High-resolution imaging of the placenta-decidua interface stained by multiplexed smFISH for HLA-G (EVTs), EREG (dM1), and CD14 and FOLR2 (dM2) for n = 4 donors (donor ID is specified in each panel). e: Dot plot showing normalised, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of CXCR6 (X-axis) on the EVT subsets present in TSC (n = 2). f: UMAP scatterplots of scRNA-seq of TSC (CXCL16 and BSA conditions) coloured by donor, cell cycle phase, time point, treatment and unbiased clustering using leiden (n = 2). g: Dot plot showing normalised, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of marker genes of the main trophoblast subsets (X-axis) in cell clusters defined in (f) (Y-axis) from the integrated manifold of CXCL16 and BSA conditions in trophoblast stem cell (TSC) scRNA-seq (n = 2). h: UMAP scatterplot of scRNA-seq of TSC coloured by cell state (n = 2). Villous cytotrophoblast (VCT), cytotrophoblast cell column (CCC), proliferative (p), extravillous trophoblast (EVT), interstitial EVTs (iEVTs), giant cells (GC), endovascular EVT (eEVT), dendritic cells (DC), lymphatic (l), maternal (m), fetal (f), Hofbauer cells (HOFB), innate lymphocytes (ILC), macrophages (M), monocytes (MO), natural killer (NK), perivascular (PV), decidual (d), epithelial (epi), stromal (S), fibroblasts (F), uterine smooth muscle cells (uSMC), bovine serum albumin (BSA).

Fig. 4. Predicted ligand–receptor interactions during EVT invasion.

a, Left, dot plot showing z-score of normalized, log-transformed and variance-scaled gene expression of selected receptors (y-axis) that are upregulated in EVT-1, EVT-2 and/or iEVT (ME3) (x-axis). Right, dot plot showing the presence of selected ligands (y-axis) in cells present in ME3 (invasion front; x-axis). Differential expression as in Extended Data Fig. 8a. Schematic in bottom right represents select ligand–receptor interactions. b, Left, high-resolution multiplexed smFISH of placenta–decidua interface showing HLA-G (EVT) and CD14 (decidual macrophage), and CXCL16 and its cognate receptor CXCR6. Dashed outlines indicate areas shown magnified on the right. Centre, filled and unfilled arrows indicate neighbouring CXCL16-expressing decidual macrophages and CXCR6-expressing EVTs, respectively. Images are representative of two donors. c, Schematic representation of the EVT differentiation experimental design, indicating time points and biological replicates in TSC models (n = 2 donors). d, Dot plot showing normalized, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of genes (x-axis) that are significantly upregulated (limma, FDR < 0.05, with Bonferroni correction for multiple hypotheses testing) in the EVT subsets upon exposure to CXCL16 compared with control. e, Left, dot plot showing z-score of normalized, log-transformed and variance-scaled gene expression of selected receptors (y-axis) that are upregulated in GC (ME4) (x-axis). Right, dot plot showing the presence (y-axis) of selected ligands in cells present in ME4 (decidual–myometrial border; x-axis). Differential expression as in Extended Data Fig. 8a. Schematic in bottom right represents select ligand–receptor interactions. f, High-resolution multiplexed smFISH of the placenta–decidua interface showing HLA-G and EFNB1, demonstrating that expression of EFNB1 is present throughout EVTs, including iEVTs, and higher in GCs. The inset (bottom centre) illustrates the multinucleated nature of GCs. Images representative of two donors. dM, decidual macrophages; dS, decidual stromal cells; endo-M, maternal endotheial cells; PV, perivascular.

We predicted multiple interactions between invading trophoblast cells and dM1 (EREG+ and IL1B+) and dM2 (FOLR2+ and CD14high) (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 11c,d). Maternal macrophages upregulate adhesion receptor genes, including CADM1 (expressed in dM1 and dM2) and SEMA4A (expressed in dM1), whose cognate receptors NECTIN3 and PLXND1 are expressed in EVTs (Fig. 4a). In addition, both dM1 and dM2 express the chemokine genes CXCL16 and CCL3, and their receptor genes CXCR639 and CCR1 are upregulated in invading EVTs (Fig. 4a). CXCR6+HLA-G+ EVTs and CXCL16+CD14+ decidual macrophages are in close proximity in the implantation site (Fig. 4b). Similar to their in vivo counterparts, scRNA-seq confirms that TSC-EVTs express CXCR6, and we used this model to functionally validate the effect of CXCL16 on EVTs (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 11e–h). CXCL16 upregulates the expression of characteristic placental genes (PHLDA2 and CGA), those involved in endothelial integrity (TYMP) as well as cytokeratins (KRT7, KRT8 and KRT18), actin-binding molecules (CORO1B) and the galectin member LGALS3, previously assigned to have a role in EVT invasion40 (Fig. 4d). This is in keeping with a role for CXCL16 in promoting trophoblast motility and function.

The receptors that are potentially involved in EVT invasion, including CXCR6, CSF1R38 and PLXND1, are downregulated in GCs (Fig. 4a), in keeping with their presence at the limit of EVT invasion41. GCs form by the fusion of iEVTs and upregulate adhesion genes (JAM2, EFNB1 and SEMA4C) whose cognate receptor genes are expressed by other iEVTs (JAM3, EPHB2, EPHB3 and PLXNB2), providing potential mechanisms for fusion (Fig. 4e). A possible explanation for iEVT migration from decidua into myometrium is the specific expression of EPHB1 and EPHB410 by myometrial smooth muscle cells (uSMCs) which bind to EFNB1, which is upregulated in the iEVTs and GCs (Fig. 4e). We validated expression of EFNB1 in GCs using multiplexed smFISH (Fig. 4f).

eEVT interactions with spiral arteries

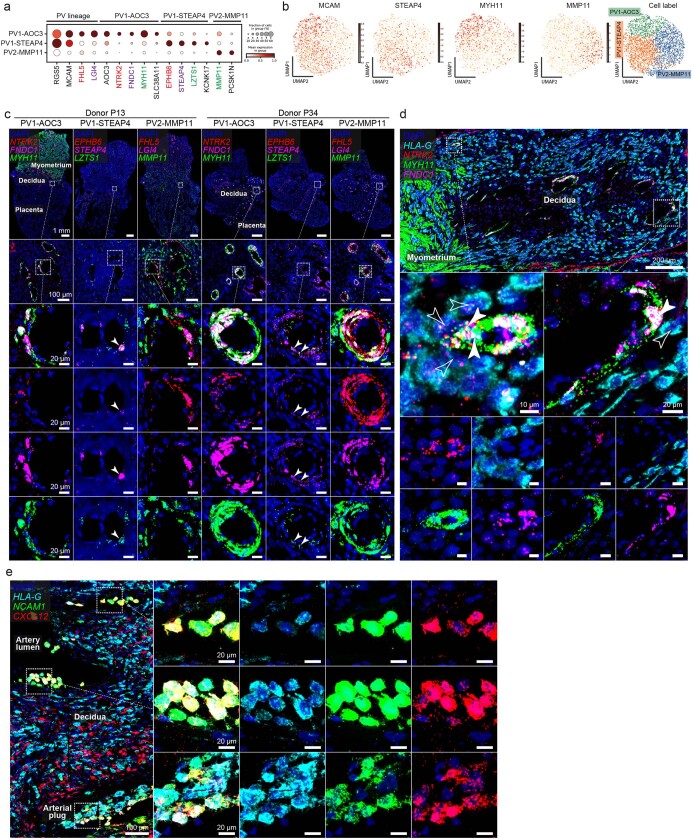

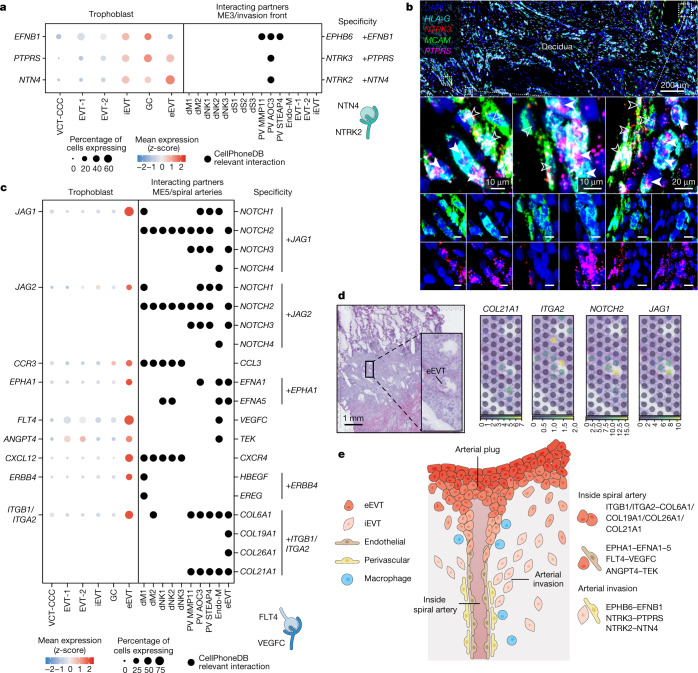

Trophoblast arterial transformation during early pregnancy is crucial for pregnancy success. Initially, there is destruction of the media by iEVTs which is replaced with acellular fibrinoid material1,27,41. We previously defined two perivascular cell states13, PV1 (MCAM-high) and PV2 (MMP11-high) in the arterial media. Here we combine scRNA-seq and smFISH to identify two cell states within PV1: PV1-AOC3 (AOC3-high, MYH11-high, FNDC1-high and NTRK2-high) and PV1-STEAP4 (STEAP4-high, EPHB6-high and LZTS1-high) (Extended Data Fig. 12a–c). We mapped the interactions between perivascular cell subsets and iEVT that might lead to medial destruction. Expression of EFNB1 by iEVTs could induce their tropism towards the arteries as perivascular cells express the cognate receptor gene, EPHB6 (Figs. 4f and 5a). We also find that iEVTs upregulate specific cell signalling molecules (PTPRS and NTN4) whose cognate receptor genes (NTRK2 and NTRK3) are upregulated in PV1-AOC3 (Fig. 5a). Neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinases (NTRKs) can be associated with cellular survival. Whether they are involved in the ‘fibrinoid change’ in the arterial media1,27,41,42 would require further exploration. Using multiplexed smFISH, we validated the close proximity between iEVTs (HLA-G+) expressing PTPRS and perivascular cells (MCAM+) expressing NTRK2 and NTRK3 (Fig. 5b and Extended Data Fig. 12d).

Extended Data Fig. 12. Interactions between trophoblast and perivascular (PV) cells.

a: Dot plot showing normalised, log-transformed and variance-scaled expression of perivascular (PV) cell state markers. b: UMAP (uniform manifold approximation and projection) scatterplot of scRNA-seq of PV cells (n = 2768 cells) coloured by the scaled gene expression of PV cell state markers. c: (Top) High-resolution imaging of adjacent sections of maternal-fetal interface stained by multiplexed smFISH for three gene panels, from two donors. Dashed squares indicate areas shown magnified underneath (middle and below), highlighting PV1-AOC3, PV1-STEAP4, and PV2-MMP11 cells expressing each of their three respective marker genes. Solid arrows indicate relatively sparse PV1-STEAP4 cells in second and fifth columns. d: (Top) High-resolution imaging of a section of decidua stained by smFISH for HLA-G (EVTs) multiplexed with MYH11, FNDC1, and NTRK2 (PV1-AOC3); dashed squares indicate areas shown magnified below. (Middle) solid and outlined arrows indicate neighbouring PV1-AOC3 cells expressing NTRK2 and EVTs, respectively. Representative image of samples from two donors. e: (Left) High-resolution imaging of a section of decidua stained by multiplexed smFISH for HLA-G, NCAM1, and CXCL12. Dashed squares highlight arteries containing HLA-G+ NCAM1+ eEVTs expressing CXCL12, shown magnified to right. Representative image of samples from two donors.

Fig. 5. Predicted ligand–receptor interactions modulating uterine arterial transformation.

a, Left, dot plot showing z-score of normalized, log-transformed and variance-scaled gene expression of selected receptors (y-axis) that are upregulated in iEVT (x-axis). Right, dot plot showing the presence of selected ligands (y-axis) in cells present in ME3 (invasion front; x-axis). Differential expression as in Extended Data Fig. 8a. b, Top, high-resolution smFISH of decidua stained for HLA-G and MCAM (PV marker), and NTRK3 and its receptor PTPRS. Dashed outlines indicate areas that are shown magnified below. Middle and bottom, filled and unfilled arrows indicate neighbouring PTPRS-expressing EVTs and NTRK3-expressing dNK cells, respectively. Images are representative of three donors. c, Left, dot plot showing z-score normalized, log-transformed and variance-scaled gene expression of selected receptors (y-axis) that are upregulated in eEVT (y-axis). In the case of a complex, the expression corresponds to the least expressed subunit of the complex (ITGB1). Right, dot plot showing the presence of selected ligands (y-axis) in cells present in ME5 (spiral arteries; x-axis). Differential expression as in Extended Data Fig. 8a. d, Overview of spatial locations of invading trophoblast cell states in Visium spatial transcriptomics data of a representative section of donor P13 tissue. The position of the capture area is indicated with an arrow in Extended Data Fig. 1d. Spot colour indicates cell state densities computed by cell2location as the number of cells of a given cell state in a Visium spot. e, Schematic representation of the spiral arteries in the first trimester of human pregnancy, highlighting the novel interactions between PV–iEVT, endothelial–eEVT, and eEVT–eEVT.

eEVTs initially form plugs in the spiral arteries close to the cytotrophoblast shell that limit high-pressure maternal blood flow into the intervillous space before 8–10 PCW, prior to the establishment of the haemochorial circulation43. eEVTs eventually replace the maternal endothelium41,42. Our unbiased analyses enable us to speculate how the plugs are formed. In addition to the homotypic interactions by NCAM1, eEVTs express both ITGB1 and ITGA2 (forming the integrin α2β1) and its cognate collagen ligands (COL6A1, COL19A1, COL26A1 and COL21A1) (Fig. 5c). Active Notch signalling is suggested by upregulation of ligand ( JAG1 and JAG2) and receptor (NOTCH2 and NOTCH3) genes (Fig. 5c). Interactions of eEVTs in the vasculature (ME5) could be mediated by EPHA1, CXCL12, FLT4 and ANGPT4, with endothelial cells expressing their interacting partners EFNA1, EFNA5, VEGFC and TEK (Fig. 5c and Extended Data Fig. 12e). Using spatial transcriptomics, we visualized the expression of extracellular matrix (ECM) component (COL21A1–ITGA2) and Notch (NOTCH2–JAG1) interactions in the arterial plug (Fig. 5d).

Together, our high-resolution analyses of the spiral arteries in the decidua basalis enabled us to detect several ECM components and ligand–receptor pairs that are expressed in eEVT and maternal endothelial cells as well as in iEVT and PV subsets (Fig. 5e). These ligand–receptor interactions that occur between maternal and fetal cells are likely to be pivotal in mediating the maternal arterial transformation that is characteristic of the first trimester of pregnancy and is essential for its success.

Discussion

In the postimplantation embryo, trophectoderm differentiates into trophoblast that invades the uterus to transform the maternal arteries. Defective trophoblast invasion is the primary underlying cause of the great obstetric syndromes that include pre-eclampsia, fetal growth restriction, unexplained stillbirth, placental abruption and preterm labour2. We made use of a historical collection of first-trimester pregnant hysterectomies to delineate the trophoblast landscape at the implantation site, where fetal and maternal cells intermingle. The human implantation sites profiled in our study were collected more than 30 years ago and have been stored in liquid nitrogen. We report new high-quality multiomics and spatial data, and developed a statistical framework (StOrder) that describes the complete trophoblast invasion trajectory during the first trimester of pregnancy. This includes the unbiased transcriptomics profile of eEVTs that replace the endothelium from the maternal arteries and placental bed GCs, present deeper in the decidua and the inner third of the myometrium. We use the complete in vivo trophoblast trajectory to benchmark current PTOs and TSCs in vitro trophoblast models and demonstrate that they faithfully recapitulate EVT differentiation. Terminal eEVTs and deep invasive GCs are absent in our in vitro cultures, and we reason that maternal signals from uterine cells and maternal serum are required to generate them.

Our systems biology approach has enabled us to explore potential interactions between EVTs and maternal decidual cells. First, we predict the ligand–receptor interactions between the maternal macrophages and EVT, in keeping with the importance of decidual innate immune cells for placentation32. We further explore the poorly described macrophage–EVT signalling axis in vitro and describe upregulation of motility genes in the EVT subsets. Second, we pinpoint the potential molecular and cellular mediators of arterial transformation during early pregnancy. Interactions between PV1-AOC3 and iEVT could drive iEVT tropism towards the arterial wall and mediate the destruction of arterial smooth muscle media. eEVTs have a specific ECM that could allow them to form the plug. There are also specific interactions with endothelial cells that enable eEVTs to adhere to them. These novel interactions add to our understanding of the communication between endothelial and eEVT cells44. The effect of defective arterial transformation in the later stages of pregnancy is well-described and underpins the great obstetric syndromes9. Our study increases the understanding of these major pregnancy disorders, all of which have their origins in the first trimester45. In addition, our roadmap of trophoblast differentiation can be used as a blueprint to design improved in vitro models that fully recapitulate the early stages of implantation.

Methods

Human samples

Placental and decidual samples used for the in vivo and in vitro profiling were obtained from elective terminations from: The MRC and Wellcome-funded Human Developmental Biology Resource (HDBR, https://www.hdbr.org), with appropriate maternal written consent and approval from the Fulham Research Ethics Committee (REC reference 18/LO/0822) and Newcastle and North Tyneside 1 Research Ethics Committee (REC reference 18/NE/0290). The HDBR is regulated by the UK Human Tissue Authority (HTA; https://www.hta.gov.uk) and operates in accordance with the relevant HTA Codes of Practice.Addenbooke’s Hospital (Cambridge) under ethical approval from the Cambridge Local Research Ethics Committee (04/Q0108/23), which is incorporated into the overarching ethics permission given to the Centre for Trophoblast Research biobank for the Biology of the Human Uterus in Pregnancy and Disease Tissue Bank at the University of Cambridge under ethical approval from the East of England-Cambridge Central Research Ethics Committee (17/EE/0151) and from the London-Hampstead Research Ethics Committee (20/LO/0115).

Placental–decidual blocks (P13, P14 and P34) were collected prior to 1 September 2006 and consent for research use was not obtained. These samples are considered ‘Existing Holdings’ under the Human Tissue Act and as such were able to be used in this project. All the other tissue samples used for this study were obtained with written informed consent from all participants in accordance with the guidelines in The Declaration of Helsinki 2000.

All samples profiled were histologically normal.

TSC lines BTS5 and BTS11 derived from human blastocysts by H. Okae and colleagues5 were used in this study. Informed consent was obtained from all donors prior to the establishment of the cell line and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tohoku University School of Medicine (Research license 2016-1-371), associated hospitals, the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Japan). This work was internally approved by HuMFre-20-0005 at the Wellcome Sanger Institute and the lines were covered by a Conditions of Use agreement with the Tohoku University School of Medicine (internal reference CG175).

Tissue cryopreservation

Fresh tissue samples of human implantation sites were embedded in cold OCT medium and flash-frozen using a dry ice-isopentane slurry as described46.

Quality of archival frozen tissue samples was assessed by extraction of RNA from cryosections using the QIAGEN RNeasy Mini Kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions including on-column DNase I digestion. RNA quality was assayed using the Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit. All samples processed for Visium and single-nuclei had RIN values greater than 8.7.

Single-nuclei extraction

Single-nuclei suspensions were isolated from frozen tissue sections when performing multiomic snRNA-seq, scATAC-seq and snRNA-seq, following the manufacturer’s instructions. For each OCT-embedded sample, 400 μm of tissue was prepared as 50 μm cryosections, which were paused in a tube on dry ice until subsequent processing. Nuclei were released via Dounce homogenization as described47.

Single-cell isolation from tissue

We used the previous protocol optimized for the decidual–placental interface13. In short, decidual tissues were enzymatically digested in 15 ml 0.4 mg ml−1 collagenase V (Sigma, C9263) solution in RPMI 1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 21875-034)/10% FCS (Biosfera, FB-1001) at 37 °C for 45 min. The supernatant was diluted with medium and passed through a 100-μm cell sieve (Corning, 431752) and then a 40-μm cell sieve (Corning, 431750). The flow-through was centrifuged and resuspended in 5 ml of red blood cell lysis buffer (Invitrogen, 00-4300) for 10 min. Placental villi were scraped from the chorionic membrane using a scalpel and the stripped membrane was discarded. The resultant villous tissue was enzymatically digested in 70 ml 0.2% trypsin 250 (Pan Biotech P10-025100P)/0.02% EDTA (Sigma E9884) in PBS with stirring at 37 °C for 9 min. The disaggregated cell suspension was diluted with medium and passed through a 100-μm cell sieve (Corning, 431752). The undigested gelatinous tissue remnant was retrieved from the gauze and further digested with 10–15 ml collagenase V at 1.0 mg ml−1 (Sigma C9263) in Ham’s F12 medium/10% FBS with gentle shaking at 37 °C for 10 min. The disaggregated cell suspension was diluted with medium and passed through a 100 μm cell sieve (Corning, 431752). Cells obtained from both enzyme digests were pooled together and passed through a 100 μm cell sieve (Corning, 431752) and washed in Ham’s F12. The flow-through was centrifuged and resuspended in 5 ml of red blood cell lysis buffer (Invitrogen, 00-4300) for 10 min.

Trophoblast in vitro cultures

Trophoblast stem cell (TSC) lines BTS5 and BTS11 derived by Okae and colleagues were grown as described previously5. In brief, TSC self-renewing medium (TSCM) components were substituted with local suppliers with the exception for 30% w/v BSA from WAKO Japan and CHIR99021 concentration was increased to 6 µM which maintained the undifferentiated morphology as well as preserving its EVT invasive morphology. TSCs were grown on 5 µg ml−1 Collagen IV (Corning) coated wells and early passaged cells between passages 24 and 26 were used for differentiation and analysis. For 2D differentiation into EVT identity, cells were seeded at a density of 1.3 × 105 per cm2 (corresponding to 125,000 cells plated on a well of a 6-well plate) in EVTM1 detailed below supplemented with ice-cold 2% Matrigel GFR (Corning) before seeding on 1 µg ml−1 Collagen IV (Corning) coated wells (D0). Three days later (D3), medium was changed to EVTM2 supplemented with ice-cold 0.5% Matrigel GFR. Three days later (D6), the medium was changed to EVT medium 3 supplemented with ice-cold 0.5% Matrigel GFR. Cells were treated with TrypLE for downstream analysis 48 h later (D8). For CXCL16 induction experiments, a final concentration of 100 ng ml−1 CXCL16 (RnD 976-CX-025 with carrier, dissolved in 0.1%BSA(WAKO)/PBS) were supplemented to EVTM2 or EVTM3 and analysed 48 h later. The induction was controlled by supplementing an equal volume of 0.1% BSA/PBS.

In total, six trophoblast organoids were grown and differentiated into EVT as previously described3,48. To differentiate trophoblast organoids into EVT, organoids were cultured with TOM for ~3–4 days and transferred into EVTM1 (+NRG1) for ~4–7 days. Once trophoblasts initiate their commitment into EVT (spike emergence), EVTM2 (−NRG1) is added for 4 days. Donors were differentiated and collected in batches of three that were multiplexed on the same 10x Genomics reaction. Samples for donors 1, 2 and 3 were collected at 3 h, 24 h and 48 h after the addition of EVTM2, while samples for donors 4, 5 and 6 were collected at 48 h before, and then 0 h, 48 h and 96 h after, addition of EVTM2. Organoids grown in TOM were also collected as a control at 96h.

Media compositions have been described previously3,5,48 and are shown here. TSCM: DMEM/F12 with Glutamax (Gibco) supplemented with 0.2% v/v FBS (Gibco), 0.3% wt/vol BSA (WAKO), 1% ITS-X (Gibco), 2.5 µg ml−1 l-ascorbic acid-2-phosphate (Sigma), 50 ng ml−1 EGF (Peprotech AF-100-15), 6 µM CHIR99021 (Tocris 4423), 0.5 µM A83-01 (Tocris 2939), 1 µM SB43154 (Tocris 1614), 0.8 mM VPA (Sigma, dissolved in H2O) and 5 µM Y-27632 (Millipore 688000). TOM: Advanced DMEM/F12, N2 supplement (at manufacturer’s recommended concentration), B27 supplement minus vitamin A (at manufacturer’s recommended concentration), Primocin 100 μg ml−1, N-Acetyl-l-cysteine 1.25 mM, l-glutamine 2 mM, recombinant human EGF 50 ng ml−1, CHIR99021 1.5 µM, recombinant human R-spondin-1 80 ng ml−1, recombinant human FGF-2 100 ng ml−1, recombinant human HGF 50 ng ml−1, A83-01 500 nM, prostaglandin E2 2.5 µM, Y-27632 5 µM. EVTM1: Advanced DMEM/F12 (or DMEM/F12 for TSC-EVTM 2D), l-glutamine 2 mM, 2-mercaptoethanol 0.1 mM, penicillin/streptomycin solution 0.5% (vol/vol), BSA 0.3% (wt/vol, WAKO), ITS-X supplement 1% (vol/vol), NRG1 (Cell Signaling 5218SC) 100 ng ml−1, A83-01 7.5 µM, knockout serum replacement 4% (vol/vol). EVTM2, Advanced DMEM/F12 (or DMEM/F12 for TSC-EVTM 2D), l-glutamine 2 mM, 2-mercaptoethanol 0.1 mM, penicillin/streptomycin solution 0.5% (vol/vol), BSA 0.3% (wt/vol, WAKO), ITS-X supplement 1% (vol/vol), A83-01 7.5 µM, Knockout serum replacement 4% (vol/vol) (this is the same as EVTM1 without NRG1). This medium can be stored at 4 °C for up to 1 week. EVTM3, DMEM/F12 (for TSC-EVTM 2D), l-glutamine 2 mM, 2-mercaptoethanol 0.1 mM, penicillin/streptomycin solution 0.5% (vol/vol), BSA 0.3% (wt/vol, WAKO), ITS-X supplement 1% (vol/vol), A83-01 7.5 µM (this is the same as EVTM1 without NRG1 or knockout serum replacement). This can be stored at 4 °C for up to 1 week.

H&E staining and imaging

Fresh frozen sections were removed from −80 °C storage and air dried before being fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 5 min. After rinsing with deionised water, slides were stained in Mayer’s haematoxylin solution for 90 s. Slides were completely rinsed in 4–5 washes of deionised water, which also served to blue the haematoxylin. Aqueous eosin (1%) was manually applied onto sections with a pipette and rinsed with deionised water after 1–3 s. Slides were dehydrated through an ethanol series (70%, 70%, 100%, 100%) and cleared twice in 100% xylene. Slides were coverslipped and allowed to air dry before being imaged on a Hamamatsu Nanozoomer 2.0HT digital slide scanner.

Multiplexed smFISH and high-resolution imaging

Large tissue section staining and fluorescent imaging were conducted largely as described previously49. Sections were cut from fresh frozen samples embedded in OCT at a thickness of 10–16 μm using a cryostat, placed onto SuperFrost Plus slides (VWR) and stored at −80 °C until stained. Tissue sections were processed using a Leica BOND RX to automate staining with the RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent Reagent Kit v2 Assay (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Bio-Techne), according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Probes are listed in Supplementary Table 8. Prior to staining, fresh frozen sections were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 6–8 h, then dehydrated through a series of 50%, 70%, 100%, and 100% ethanol, for 5 min each. Following manual pre-treatment, automated processing included heat-induced epitope retrieval at 95 °C for 15 min in buffer ER2 and digestion with Protease III for 15 min prior to probe hybridisation. Tyramide signal amplification with Opal 520, Opal 570, and Opal 650 (Akoya Biosciences) and TSA-biotin (TSA Plus Biotin Kit, Perkin Elmer) and streptavidin-conjugated Atto 425 (Sigma Aldrich) was used to develop RNAscope probe channels.

Stained sections were imaged with a Perkin Elmer Opera Phenix Plus High-Content Screening System, in confocal mode with 2 μm z-step size, using a 40× (NA 1.1, 0.149 μm/pixel) water-immersion objective. Channels: DAPI (excitation 375 nm, emission 435–480 nm), Atto 425 (excitation 425 nm, emission 463–501 nm), Opal 520 (excitation 488 nm, emission 500–550 nm), Opal 570 (excitation 561 nm, emission 570–630 nm), Opal 650 (excitation 640 nm, emission 650–760 nm).

Image stitching

Confocal image stacks were stitched as two-dimensional maximum intensity projections using proprietary Acapella scripts provided by Perkin Elmer.

10x Genomics Chromium GEX library preparation and sequencing

For the scRNA-seq experiments, cells were loaded according to the manufacturer’s protocol for the Chromium Single Cell 3′ Kit v3.0, v3.1 and 5’ v1.0 (10X Genomics). Library preparation was carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocol to attain between 2,000 and 10,000 cells per reaction. Libraries were sequenced, aiming at a minimum coverage of 20,000 raw reads per cell, on the Illumina HiSeq 4000 or Novaseq 6000 systems using the following sequencing format: (A) read 1: 26 cycles; i7 index: 8 cycles, i5 index: 0 cycles; read 2: 98 cycles; (B) read 1: 28 cycles; i7 index: 8 cycles, i5 index: 0 cycles; read 2: 91 cycles; (C) read 1: 28 cycles; i7 index: 10 cycles; i5 index: 10 cycles; read 2: 90 cycles (v3.1 dual).

For the multimodal snRNA-seq and scATAC-seq experiments, cells were loaded according to the manufacturer’s protocol for the Chromium Single Cell Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression v1.0 to attain between 2,000 and 10,000 cells per well. Library preparation was carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Libraries for scATAC-seq were sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq 6000, aiming at a minimum coverage of 10,000 fragments per cell, with the following sequencing format; read 1: 50 cycles; i7 index: 8 cycles, i5 index: 16 cycles; read 2: 50 cycles.

10x Genomics Visium library preparation and sequencing

Ten-micrometre cryosections were cut and placed on Visium slides, then processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, sections were fixed with cold methanol, H&E stained and imaged on a Hamamatsu NanoZoomer S60 before permeabilization, reverse transcription and cDNA synthesis using a template-switching protocol. Second-strand cDNA was liberated from the slide and single-indexed libraries were prepared using a 10x Genomics PCR-based protocol. Libraries were sequenced (1 per lane on a HiSeq 4000), aiming for 300M raw reads per sample, with the following sequencing format; read 1: 28 cycles, i7 index: 8 cycles, i5 index: 0 cycles and read 2: 91 cycles.

Alignment and quantification of scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq data

For each sequenced single-cell and single-nucleus RNA-seq library, we performed read alignment to the 10X Genomics’ GRCh38 3.0.0 human reference genome, mRNA version for scRNA-seq samples and pre-mRNA version for snRNA-seq samples, latter created following instructions from 10X Genomics: https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-gene-expression/software/pipelines/latest/advanced/references#premrna. Quantification and initial quality control were performed using the Cell Ranger Software (version 3.0.2; 10X Genomics) using default parameters. Cell Ranger filtered count matrices were used for downstream analysis.

Alignment and quantification of multiome data

For each sequenced snRNA-seq and ATAC–seq (multiome) library, we performed read alignment to custom made genome consisting of 10X Genomics’ GRCh38 3.0.0 pre-mRNA human reference genome and 10X Genomics Cell Ranger-Arc 1.0.1 ATAC genome, created following instructions from 10X Genomics: https://support.10xgenomics.com/single-cell-multiome-atac-gex/software/pipelines/latest/advanced/references. Quantification and initial quality control were performed using the Cell Ranger-Arc Software (version 1.0.1; 10X Genomics) using default parameters. Cell Ranger-Arc filtered count matrices were used for downstream analysis.

Downstream scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq analysis

Detection of doublets by gene expression

We used Scrublet for cell doublet calling on a per-library basis. We used a two-step diffusion doublet identification followed by Bonferroni FDR correction and a significance threshold of 0.01, as described in50. Predicted doublets were not excluded from the initial analysis, but used afterwards to flag clusters with high doublet scores.

Detection of doublets by genotype

Souporcell51 was used to deconvolute (1) maternal and fetal origin of cells and nuclei in our scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq samples (including multiome snRNA-seq); (2) assignment of cells to individuals in pooled samples (namely, samples Pla_HDBR8768477, Pla_HDBR8715512 and Pla_HDBR8715514); and (3) organoids from multiple individuals. In some samples deconvolution into maternal or fetal origin by genotype was not possible which is probably owing to the highly skewed ratio of genotypes (either extremely high (>0.95) or extremely low (<0.05) ratio of maternal to fetal droplets). In those cases, maternal–fetal origin of the cells was identified using known markers from ref. 13.

Souporcell (version 2.4.0) was installed as per instructions in https://github.com/wheaton5/souporcell and used in the following way:

path_to/singularity exec ./souporcell.sif souporcell_pipeline.py -i ./cellranger_path/possorted_genome_bam.bam -b ./cellranger_path/filtered_feature_bc_matrix/barcodes.tsv -f ./genome_path/genome.fa -t 8 -o souporcell_result -k 2 --skip_remap True --common_variants ./filtered_2p_1kgenomes_GRCh38.vcf

Where k = 2 corresponds to the number of individuals to be deconvoluted (in our case either mother and fetus or pooled individuals H7 and H9 in samples Pla_HDBR8768477, Pla_HDBR8715512 and Pla_HDBR8715514. The accuracy of deconvolution was evaluated in downstream analysis once cluster identity was clear from either gene expression or predictions of logistic regression. In samples where deconvolution worked successfully, inter-individual doublets were further excluded from downstream analysis.

Filtering genes high in ambient RNA signal