Abstract

Purpose: From 1991 through 2000, incoming medical students (M-Is) at the School of Medicine at Virginia Commonwealth University have been surveyed with a written questionnaire on their computer literacy. The survey's purpose is to learn the students' levels of knowledge, skill, and experience with computer technology to guide instructional services and facilities.

Methodology: The questionnaire was administered during M-I orientation or mailed to students' homes after matriculation. It evolved from sixteen questions in 1991 to twenty-three questions in 2000, with fifteen questions common to all.

Results: The average survey response rate was 81% from an average of 177 students. Six major changes were introduced based on information collected from the surveys and advances in technology: production of CD-ROMs distributed to students containing required computer-based instructional programs, delivery of evaluation instruments to students via the Internet, modification of the lab to a mostly PC-based environment, development of an electronic curriculum Website, development of computerized examinations for medical students to prepare them for the computerized national board examinations, and initiation of a personal digital assistant (PDA) project for students to evaluate PDAs' usefulness in clinical settings.

Conclusion: The computer literacy survey provides a snapshot of students' past and present use of technology and guidance for the development of services and facilities.

INTRODUCTION

The need for medical students to be computer literate is no longer an issue for debate. A study in the late 1980s at McMaster University already noted a trend in the increased use of information technology [1]. Today, many medical schools require students to purchase computers [2, 3], and others are developing strategies for integrating medical informatics into the curriculum [4, 5]. The role of information technologies—including using computerized medical records, retrieving computer-based knowledge resources, and understanding the basics of the Internet—is crucial for physicians [6,7]. Soon, “practitioners will have neither the option nor the desire to resist if they intend to practice the most effective style of medicine” [8]. Strategies for use of information technologies must take into account the skills of incoming medical students and their need for training in certain areas [9–12]. Faughan and Elson predict that ”ubiquitous, simple network computing and ‘power tools' for managing medical knowledge” have implications for how schools cover such educational topics as patient confidentiality, systems thinking, error management, and knowledge resource evaluation [13].

To these ends, the School of Medicine at the Medical College of Virginia Campus of Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) supports the Association of American Medical Colleges' (AAMC) belief that “to practice medicine in the twenty-first century, medical students … must be given a strong grounding in the use of computer technology to manage information, support patient care decisions, select treatments, and develop their abilities as lifelong learners” [14].

In June 1998, the AAMC's Medical Informatics Advisory Panel issued learning objectives for medical informatics that deans and faculty could use as a guide [15]. In response, VCU established a Medical Informatics Curriculum Committee to identify what medical students should be able to do with information technology and what knowledge and attitudes about information technology they require for the five major roles played by physicians: life-long learner, clinician, educator or communicator, researcher, and manager. The long-term goal is to implement changes necessary to ensure that VCU medical students acquire information technology competencies.

BACKGROUND

The School of Medicine operates the Computer Based Instruction Lab (CBIL) to support the curricular needs of medical students and faculty of Virginia Commonwealth University, School of Medicine, Medical College of Virginia Campus. CBIL builds on a thirty-year history of the School of Medicine providing instructional materials directly through a School of Medicine Learning Resource Center. CBIL is not affiliated with the health sciences library but is managed by a professional librarian and staffed by library and computer specialists, as well as students.

CBIL has forty-four networked microcomputer workstations, Novell and NT servers, videodisc players, videocassette recorders, and Telex thirty-five millimeter slide viewers. CBIL contains instructional resources that include approximately 150 computer-based instruction programs, sixty-seven of which have been developed by School of Medicine faculty, staff, and students. Selected programs are included on a CD-ROM distributed annually to all medical students free of charge. Information resources on the Web may be accessed via CBIL* or from off campus.

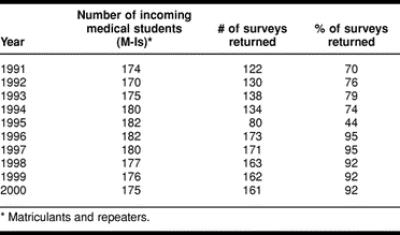

Since August 1991, medical students have been surveyed with a written questionnaire on their levels of computer literacy. The average response rate was 81% (Table 1). The purpose of the survey is to learn the level of knowledge, skill, and experience with computer technology of the school's entering medical students to provide guidance with instructional services, facilities, and other resources. The survey was initiated by the faculty in the Office of Continuing Medical Education (formerly the Office of Medical Education) and since 1995 managed by faculty in the Office of Faculty and Instructional Development. The appendix contains the survey instrument, Medical Student Computer Experience Survey, used for the August 2000 survey.

Table 1 Student body size by year, number, and percentage of respondents

METHODOLOGY

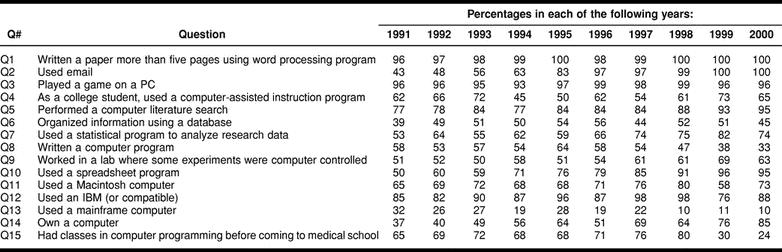

The original 1991 questionnaire of sixteen questions was adapted from instruments used by the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and Informatics in Medical Education and Development (IMED), representing the University of California, University of Southern California, Loma Linda University, and Stanford University. Over the ten-year period in which the survey has been administered, it has evolved to its present form, which contains twenty-three questions, with fifteen questions common to all surveys (Table 2).

Table 2 Fifteen questions common to all ten questionnaires and percentage of affirmative responses by year

Different ways in which the survey has been administered include: the distribution and collection during orientation for incoming medical students (M-I) in either one large group or in small groups in CBIL and mailing of the survey to students' homes separately or as part of the admissions package.

RESULTS

The School of Medicine has identified six key informatics objectives that students are expected to attain by the time they complete their undergraduate medical education. These objectives state that medical students should be able to:

access computer-based instruction for self-study learning in medical education;

search the medical literature using MEDLINE, MICROMEDEX, and other online full text and bibliographic systems;

utilize diagnostic decision-support systems as an additional method of learning medical diagnosis and problem solving;

utilize email, the Internet, and other online information resources to obtain information quickly and efficiently;

utilize patient information systems to manage medical records in the practice of medicine; and

develop proficiency in completing computerized examinations.

By knowing the level of technological experience that medical students have when they arrive, CBIL is able to utilize the most appropriate strategies, methods, and resources to help students meet these goals. This knowledge allows CBIL to plan educational activities that address deficiencies in knowledge, such as students having little experience with computer literature searching, and to reconfigure hardware, such as moving from a half Macintosh computer/half IBM-compatible personal computer (PC) lab to predominantly PC, in response to student needs. The information has also prompted the production of CD-ROMs containing CBIL-developed computer-based instructional programs, because more than 85% of students have their own computers. The CDs allow them to study on their own, at their own pace, at home, or at other sites distant from the medical school. Survey data are shared with teaching faculty, who also use the information to plan course delivery in CBIL, in labs, and via the Web.

As responses to questions 1 and 3 indicated, virtually all surveyed M-I students have had experience with the basic computer skills of word processing and playing computer games. This information let CBIL staff know that most entering medical students had at least a rudimentary understanding of basic computer navigation—use of pull-down menus to open, save, and print files and familiarity with use of the mouse and keyboard. Training resources could be redirected from these basic skills to higher-level computer functions. Responses to question 2 about the use of email, on the initial survey in 1991, showed that only 43% of M-Is had experience with it. As a way to ensure that students learned this important skill, CBIL and the Curriculum Office collaborated to deliver grades to students in their email accounts beginning in 1993. Although use of email is common now, this strategy provided a powerful motivation for students to become familiar with email in 1993, when it was not as ubiquitous. By the 2000 survey, 100% of students were familiar with email when they arrived in medical school and email delivery of grades was well integrated into the medical school culture. Because of the students' comfort with using email, CBIL staff only needed a few minutes to teach students the specifics of their email program, rather than the concept of email in general. This training takes place during the first week of school, as part of the CBIL student orientations that cover all pertinent aspects of the computer lab.

Responses to question 4, which asks about experience with computer-assisted instruction (CAI), indicated that the first-year medical students' exposure to CAI has remained fairly steady throughout the survey period. In 1991, 62% of students had used these programs and 65% in 2000. The implications for our medical students are significant, because more than sixty programs covering required curricular materials are available to students in computerized format. Knowing that approximately 35% of incoming students are unfamiliar with CAI helps CBIL staff plan their training strategies, so they can help these students quickly become comfortable with the use of this software, because CAI is integrated into all ten courses in year 1, fifteen in year 2, and seven in year 3. Year 4 offers more than 400 electives, which have varying degrees of computer integration. CBIL staff work with medical students when they need assistance using these programs, at a service desk and with written and classroom tutorials.

Responses to question 5 indicated that 77% of students have performed their own literature searches prior to coming to medical school in 1991 and that figure rose to 95% by 2000. This proved to be an inadequate appraisal of students' searching competence for the health sciences literature. The question assumed a minimum level of skill and competency that accompanied students' searching experience. Wildemuth and Moore, in a study of end-user search behavior, also found students generally were satisfied with their searching ability, while librarians reviewing the searches found missed opportunities in almost all the searches [16]. CBIL's director, also a medical librarian and the only library professional in the School of Medicine, discovered in the course of conducting training classes that this assumption that students had adequate searching skills was not the case. One of the most significant observations was that not only did most of the students lack the knowledge and strategies to search the medical literature efficiently and effectively, they believed that they were proficient and thus were reluctant to accept help. It was only when they were required to complete assignments for which they were graded on the quality of their searching skills that they began to acknowledge their deficits.

CBIL and library faculty conducted small group classes on searching medical literature, including MEDLINE and Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) and the Web for M-I “Genetics.” For year 2 (M-II) “Foundations of Clinical Medicine” (FCM) and year 3 (M-III) “Internal Medicine,” MEDLINE was taught, and “Surgery Clerkship” teaching included MD Consult. In addition, classes on MICROMEDEX were added to the FCM curriculum to assist students who were assigned to complete a patient history at a long-term-care facility, a component of which was the collection of data on medications.

Questions 6 to 10 and 15 do not relate directly to skills required for students presently in medical school at VCU. They are included in the survey to give researchers a feel for the breadth of students' technology experience in general, as well as providing future information for them, if and when these skills are integrated into the curriculum. For those students who are interested in learning about databases or spreadsheets for special assignments or electives, CBIL staff are available to provide instruction in the form of short “lunch and learn” classes that are focused on specific student interests and are conveniently scheduled. For those students interested in learning more about statistical programs to analyze research data, writing computer programs, or using computer control of laboratory experiments, CBIL staff are able to refer them to educational resources in the university or the community, where they can obtain this information. For those students who enter medical school with previous experience in these areas of statistical analysis, programming, or spreadsheets and databases, CBIL is provided with a source of possible workers for summer projects or research opportunities that come about from time to time.

The information gathered in questions 11 to 14 related to using or owning a computer. The number of students who previously had exposure to mainframe computers declined from 32% in 1991 to 10% in 2000. In addition, students' usage of PCs averaged 89% for the ten-year survey period. Students' exposure to Macintosh computers ranged from 58% to 80% during the same period, but the general usage of Macintosh computers has been declining as demonstrated by software manufacturers' focus on programs that only work on PCs. In addition, of the 85% of students who owned computers in 2000, fewer than 10% owned Macintosh computers.

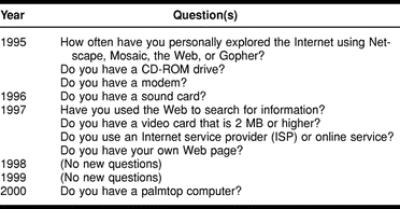

Starting with the 1995 survey, additional questions were added that reflected the changes in technology that have occurred since 1991 (Table 3). These questions involved use of and access to the Internet; hardware enhancements such as CD-ROM drives, video cards, and processor speeds; and use of personal digital assistants (PDAs). CBIL has made three strategic educational modifications in response to learning that, of the students who owned computers, 46% of them had CD-ROM drives and access to the Internet. A fourth change was a move toward a predominantly PC lab. In addition, a fifth major technology-driven modification was implemented in response to the national board's plan to move from a paper to a computerized examination. A sixth change was based on student interest in PDA technology.

Table 3 New questions added

DISCUSSION

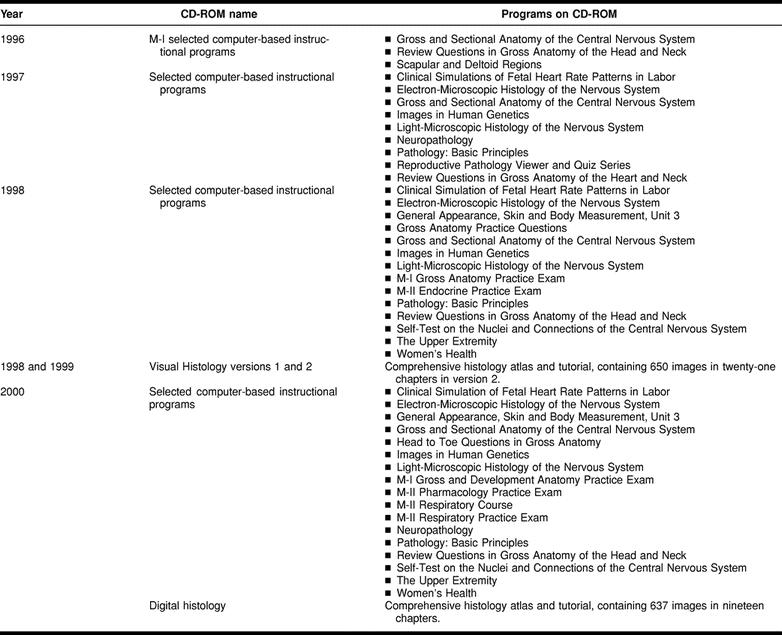

The first change was to begin producing individual CD-ROMs in 1996 that were distributed to students free of charge. They contained the required educational computer-based instructional programs that had been produced in CBIL with VCU faculty authors. This was a way of expanding students' access to these programs beyond the forty-four computer stations in CBIL. The CD-ROMs contain three to seventeen computer-based instructional programs, developed and revised annually by CBIL with School of Medicine faculty authors (Table 4).

Table 4 CD-ROMs produced by the Computer Based Instruction Lab (CBIL) and distributed to undergraduate medical students

The second change, implemented in 1997, was to begin delivering evaluation instruments to students via the Internet. Surveys are embedded in student email messages, to which they are able to respond quickly via an Internet link. Once the format for processing surveys was developed, administering student surveys became relatively quick and easy. Student feedback has been solicited on technology fee usage, PDA pilot experiences, evaluation of computer exams, numerous courses, computer-based instructional programs, and an ever-expanding list of topics for which data collection is desirable.

The third change, implemented in 1998, came about because of the general decline in Macintosh computers in the world at large and the small number of incoming medical students who owned them. With the decrease in focus on Macintosh computers by software manufacturers and students, CBIL decided to begin moving their laboratory configuration from half PC and half Macintosh computer to almost exclusively PC hardware. Hardware upgrades are scheduled in three-year cycles, and, with the last Macintosh upgrade, most of the replacements were PCs. CBIL replaced all of their Macintosh computers, except six machines, with PCs with the last upgrade.

Because of the increasing number of students who had access to the Internet, owned computers, and wanted to access educational materials in an electronic format from home, CBIL collaborated with the School of Medicine's Curriculum Office to implement the fourth change. An electronic curriculum Website was developed to incorporate educational resources available for each School of Medicine course. This development also supported the dean's request for the school to move aggressively with “electrifying” the curriculum.

The site is organized by each of the four years of the medical school curriculum. Resources included in the Website consist of electronic syllabi, course schedules, discussion forums, interactive quizzes, computer-based instructional programs produced by CBIL or purchased commercially, PowerPoint presentations, images, charts, streaming audio and video, sample exams, Web links, and CBIL's educational resource lists. Discussion forums have also been established for each M-I and M-II course and each M-III clerkship. The Curriculum Office and instructional faculty moderate these discussion forums. They enhance lectures, labs, and group discussions, allowing students to post questions by course and enabling course directors, faculty lecturers, and other students to respond.

The fifth change came about because in 1996 the National Board of Medical Examiners announced a change in format from paper to computer examinations. CBIL and the Curriculum Office wanted to make sure that School of Medicine students could concentrate on the content they needed to learn and would have little anxiety about taking an examination on the computer. Over the next year, a computer-based exam was developed by CBIL staff in concert with faculty curriculum leaders. Beginning in the 1997/98 school year, CBIL administered one examination each to M-I (head and neck anatomy section of the “Gross and Developmental Anatomy” course) and M-II (“Endocrine” course) medical students. In 1998/99, the same two courses included computerized exams. In addition, computer exams were given in M-II “Respiratory” and as a second semester exam in the M-II “Foundations of Clinical Medicine” course. For the 1999/2000 school year, twelve computerized exams were administered: four “Histology” practicals, the “Gross and Developmental Anatomy” exam, and the “Behavioral Sciences” exam for M-I students. M-II exams included “Pharmacology,” “Hematology/Oncology,” “Endocrine,” “Respiratory,” “Neurobehavioral Sciences,” and “Foundations of Clinical Medicine.” During the 2000/01 school year, exams were scheduled in “Histology” (five), “Behavioral Sciences I,” “Hematology/Oncology,” “Endocrine,” “Respiratory,” “Behavioral Sciences II,” and “Foundations of Clinical Medicine.” The computer examination program was developed in CBIL with faculty curriculum leaders and incorporated student feedback. It has been enhanced every year, adding images and features such as literature searching, Web essay questions, answer strikeout, and note-taking capability. This year the students had an opportunity to review on computers the exam questions they missed.

The sixth change came about in 2000. During this year, students were asked for the first time whether or not they owned a PDA. Almost 10% of the students already owned one, but many more students expressed an interest in finding out about the capabilities of PDAs and their usefulness in the clinical setting. With monies from the student technology fee assessment, CBIL purchased fifteen Handspring Visor Deluxe PDAs with 16 MB of RAM and subscriptions to handheldmed.com's Mobile Practice suite of software. Of all who expressed an interest, fifteen students were randomly chosen to receive a Visor and software. The participation requirements include completing a bimonthly usage or experience report and attending at least two out of five user group meetings. Data are currently being gathered from M-II, M-III, and M-IV medical students to find out how useful the PDAs are in the clinical setting and what software students find most helpful.

CONCLUSION

The information that CBIL obtains from the annual computer literacy survey makes it possible to respond to students' needs and changing environmental conditions as well as to meet the informatics objectives of the School of Medicine. CBIL is currently moving toward becoming an all PC facility, one that administers computerized examinations, conducts Internet evaluations, and produces its own high-quality, computer-based instructional programs that are required in the curriculum. In addition, electronic curriculum development continues to expand. Also, CBIL has responded to students' requests to learn more about uses of PDAs in clinical settings. With all of the changes and adaptations that have already been made in response to the survey data, the temptation is to relax and assume that appropriate innovations are finally in place and the future is taken care of. But with the relentless march of technological change, such as the move toward wireless solutions in a year or two, the focus could change in some unexpected way that would necessitate a shift in direction. So CBIL continues to administer the annual computer literacy survey, to use the information received as wisely as possible to further enhance medical student learning, and to function as an integral part of the undergraduate medical education process. The information not only provides a technological snapshot of the incoming medical school class but, used appropriately, it can give a small window into the future.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Chris Stephens, educational applications developer, and the staff of the Computer Based Instruction Lab, the Curriculum Office, the Office of Student Affairs, the Admissions Office, and the Office of Continuing Medical Education in the School of Medicine for their support of this computer literacy survey project.

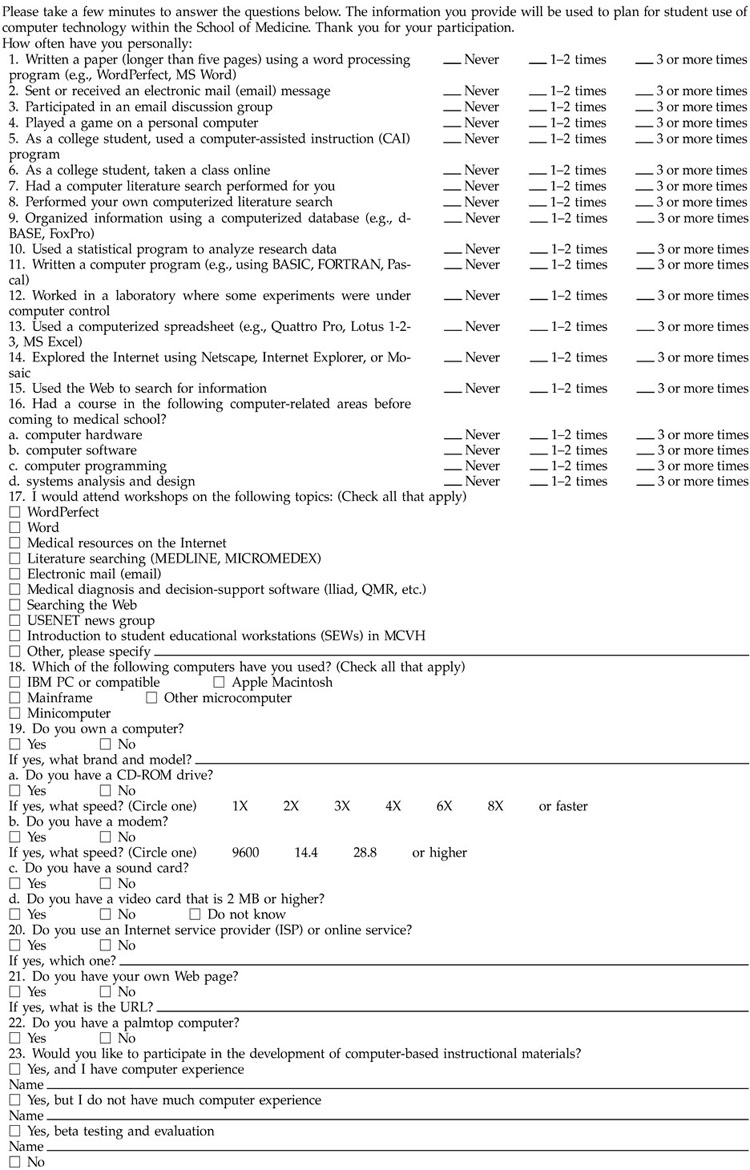

APPENDIX

Medical Student Computer Experience Survey

Computer Based Instruction Laboratory

School of Medicine, Medical College of Virginia Commonwealth University

August 2000

|

Footnotes

* The Computer Based Instruction Lab (CBIL) Website may be viewed at http://www.cbil.vcu.edu.

Contributor Information

Brenda L. Seago, Email: blseago@vcu.edu.

Jeanne B. Schlesinger, Email: jbschles@vcu.edu.

Carol L. Hampton, Email: clhampto@vcu.edu.

REFERENCES

- Haynes RB, McKibbon KA, Bayley E, Walker CJ, and Johnston ME. Increases in knowledge and use of information technology by entering medical students at McMaster University in successive annual surveys. Proc Annu Symp Comp Appl Med Care 1992;560–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elam CL, Rubeck RF, Blue AV, Bonaminio G, and Nora LM. Computer requirements for medical school students—implications for admissions. J Ky Med Assoc. 1997 Oct; 95(10):429–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley RJ. Requiring students to have computers: questions for consideration. Acad Med. 1998 Jun; 73(6):669–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman DM. Integrating informatics into an undergraduate medical curriculum. Medinfo 1995;(8 pt. 2):1139–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koschmann T. Medical education and computer literacy: learning about, through, and with computers. Acad Med. 1995 Sep; 70(9):818–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fain JA. Technological innovation: retooling for the future. Diabetes Educ. 1997 Mar–Apr; 23(2):109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider EC, Eisenberg JM. Strategies and methods for aligning current and best medical practices: the role of information technologies. West J Med. 1998 May; 168(5):311–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider EC, Eisenberg JM. Strategies and methods for aligning current and best medical practices: the role of information technologies. West J Med. 1998 May; 168(5):317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RB, Navin LM, Barrie J, Hillan E, and Kinane D. Computer literacy among medical, nursing, dental and veterinary undergraduates. Med Educ. 1991 May; 25(3):191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faughnan JG, Elson R. Information technology and the clinical curriculum: some predictions and their implications for the class of 2003. Acad Med. 1998 Jul; 73(7):766–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson KE, Silverberg M. A two-year experience teaching computer literacy to first-year medical students using skill-based cohorts. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Apr; 88(2):157–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander S. Assessing and enhancing medical students' computer skills: a two-year experience. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1999 Jan; 87(1):67–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faughnan JG, Elson R. Information technology and the clinical curriculum: some predictions and their implications for the class of 2003. Acad Med. 1998 Jul; 73(7):766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson AG, Anderson MB. Educating medical students: assessing change in medical education—the road to implementation (ACME-TRI report). Acad Med. 1993 Jun; 68(6 suppl.):S1–S46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical School Objectives Project. report II. contemporary issues in medicine: medical informatics and population medicine. [Web document]. Washington, DC: AAMC, 1998. [cited 18 Dec 2001]. <http://www.aamc.org/meded/msop/report2.htm>. [Google Scholar]

- Wildemuth BM, Moore ME. End-user search behaviors and their relationship to search effectiveness. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1995 Jul; 83(3):294–304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]