Abstract

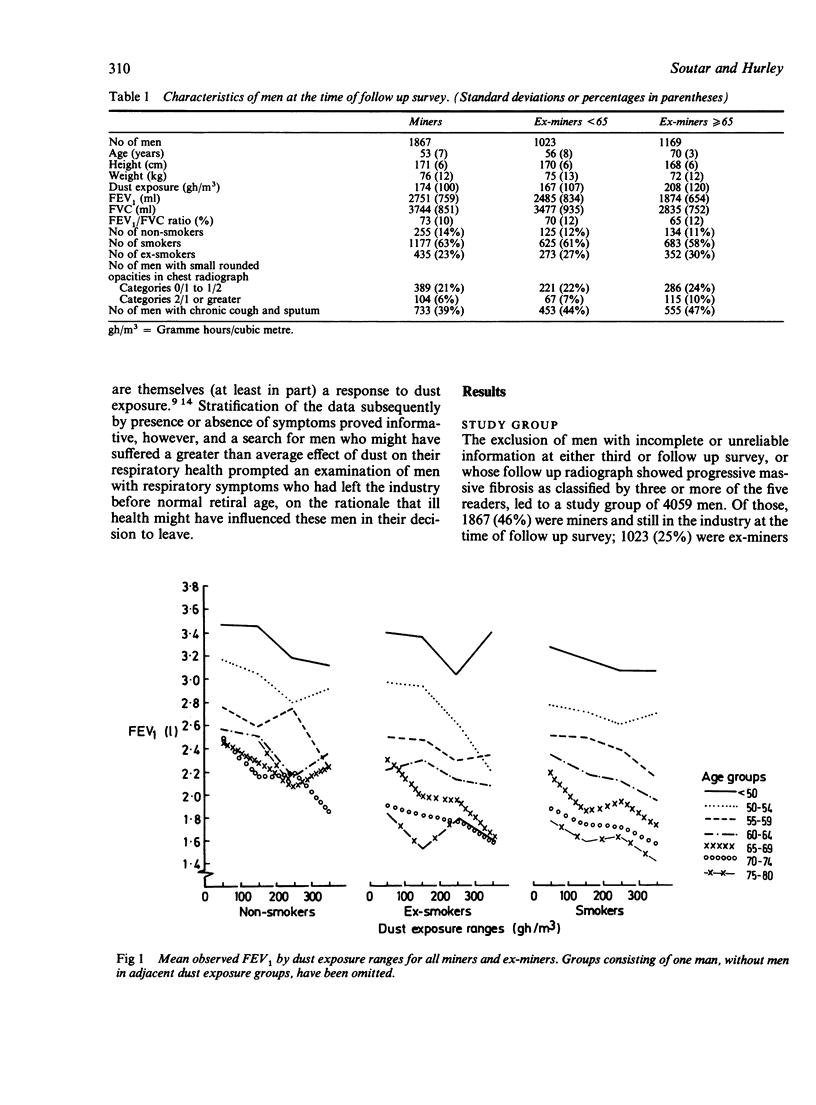

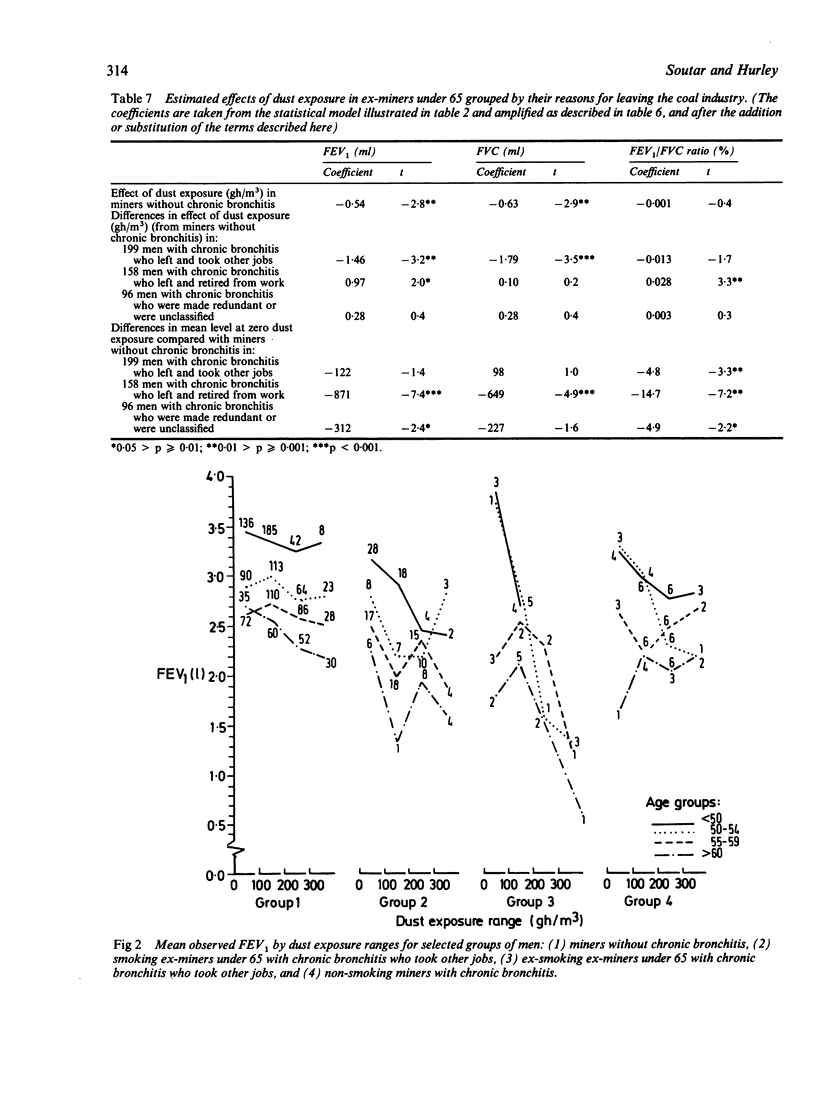

A sample of men working in the British coal industry in the 1950s has been followed up and examined 22 years later. The relations between lung function and individual cumulative exposure to respirable dust have been studied in 1867 men who were still working in the industry at the time of follow up and 2192 men who had left. Levels of forced expired volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and FEV1/FVC ratio at follow up were found to be inversely related to exposure to respirable dust after allowing for other factors, even in men without pneumoconiosis. The magnitude of this estimated effect was equivalent to a loss of 228 ml FEV1 in response to an exposure of 300 gh/m3, a moderately high exposure for this group. Ex-miners aged under 65 had worse lung function than miners on average, suggesting that ill health had encouraged some of these men to leave the industry. Whereas a more severe response to dust exposure among ex-miners under 65 was suggested, this difference could easily have arisen by chance. The presence of symptoms of chronic bronchitis was associated with reduced levels of lung function, however, and, additionally, ex-miners under 65 with chronic bronchitis showed a more severe response of the FVC to dust exposure than miners without these symptoms. Among these ex-miners with chronic bronchitis a small group of men who had taken other jobs showed a much more severe effect of dust exposure on their lung function than the average, likely in heavily exposed men to contribute importantly to disability. Men in this group who had given up smoking showed and even more severe effect of dust exposure, equivalent to a loss of 940 ml FEV1 in response to an exposure of 300 gh/m3. These results indicate that exposure to respirable dust can occasionally cause severe respiratory impairment in the absence of progressive massive fibrosis. Dust exposure was related to a parallel reduction of FEV1 and FVC, implying that the pathology of dust induced lung damage differs form that induced by smoking. This pattern of abnormality was shown by some non-smokers, whereas smokers and ex-smokers apparently severely affected by dust showed a classic obstructive pattern of abnormality with pronounced reduction of the FEV1/FVC ratio.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Attfield M. D. Longitudinal decline in FEV1 in United States coalminers. Thorax. 1985 Feb;40(2):132–137. doi: 10.1136/thx.40.2.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copland L., Burns J., Jacobsen M. Classification of chest radiographs for epidemiological purposes by people not experienced in the radiology of pneumoconiosis. Br J Ind Med. 1981 Aug;38(3):254–261. doi: 10.1136/oem.38.3.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen E. A., Wegman D. H., Louis T. A. Effects of selection in a prospective study of forced expiratory volume in Vermont granite workers. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983 Oct;128(4):587–591. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.128.4.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson J. L., Reger R. B., Morgan W. K. Maximal expiratory flows in coal miners. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977 Aug;116(2):175–180. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1977.116.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley J. F., Burns J., Copland L., Dodgson J., Jacobsen M. Coalworkers' simple pneumoconiosis and exposure to dust at 10 British coalmines. Br J Ind Med. 1982 May;39(2):120–127. doi: 10.1136/oem.39.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley J. F., Soutar C. A. Can exposure to coalmine dust cause a severe impairment of lung function? Br J Ind Med. 1986 Mar;43(3):150–157. doi: 10.1136/oem.43.3.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen M. Smoking and disability in miners. Lancet. 1980 Oct 4;2(8197):740–740. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)91952-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love R. G., Miller B. G. Longitudinal study of lung function in coal-miners. Thorax. 1982 Mar;37(3):193–197. doi: 10.1136/thx.37.3.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclaren W. M., Soutar C. A. Progressive massive fibrosis and simple pneumoconiosis in ex-miners. Br J Ind Med. 1985 Nov;42(11):734–740. doi: 10.1136/oem.42.11.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller B. G., Jacobsen M. Dust exposure, pneumoconiosis, and mortality of coalminers. Br J Ind Med. 1985 Nov;42(11):723–733. doi: 10.1136/oem.42.11.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan W. K., Burgess D. B., Lapp N. L., Seaton A. Hyperinflation of the lungs in coal miners. Thorax. 1971 Sep;26(5):585–590. doi: 10.1136/thx.26.5.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan W. K., Lapp N. L., Seaton D. Respiratory disability in coal miners. JAMA. 1980 Jun 20;243(23):2401–2404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogan J. M., Attfield M. D., Jacobsen M., Rae S., Walker D. D., Walton W. H. Role of dust in the working environment in development of chronic bronchitis in British coal miners. Br J Ind Med. 1973 Jul;30(3):217–226. doi: 10.1136/oem.30.3.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruckley V. A., Gauld S. J., Chapman J. S., Davis J. M., Douglas A. N., Fernie J. M., Jacobsen M., Lamb D. Emphysema and dust exposure in a group of coal workers. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984 Apr;129(4):528–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soter N. A., Wasserman S. I., Austen K. F. Cold urticaria: release into the circulation of histamine and eosinophil chemotactic factor of anaphylaxis during cold challenge. N Engl J Med. 1976 Mar 25;294(13):687–690. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197603252941302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]