Abstract

Introduction: Prenatal ultrasound (US) anomalies are detected in around 5%–10% of pregnancies. In prenatal diagnosis, exome sequencing (ES) diagnostic yield ranges from 6% to 80% depending on the inclusion criteria. We describe the first French national multicenter pilot study aiming to implement ES in prenatal diagnosis following the detection of anomalies on US.

Patients and methods: We prospectively performed prenatal trio-ES in 150 fetuses with at least two US anomalies or one US anomaly known to be frequently linked to a genetic disorder. Trio-ES was only performed if the results could influence pregnancy management. Chromosomal microarray (CMA) was performed before or in parallel.

Results: A causal diagnosis was identified in 52/150 fetuses (34%) with a median time to diagnosis of 28 days, which rose to 56/150 fetuses (37%) after additional investigation. Sporadic occurrences were identified in 34/56 (60%) fetuses and unfavorable vital and/or neurodevelopmental prognosis was made in 13/56 (24%) fetuses. The overall diagnostic yield was 41% (37/89) with first-line trio-ES versus 31% (19/61) after normal CMA. Trio-ES and CMA were systematically concordant for identification of pathogenic CNV.

Conclusion: Trio-ES provided a substantial prenatal diagnostic yield, similar to postnatal diagnosis with a median turnaround of approximately 1 month, supporting its routine implementation during the detection of prenatal US anomalies.

Keywords: exome sequencing (ES), chromosomal microarray, prenatal, fetal, diagnostic yield

1 Introduction

Isolated or multiple congenital anomalies (MCA) affect around 2% of pregnancies, possibly secondary to maternal etiologies (placental, infectious, toxic) but mainly due to genetic disorders (Wojcik et al., 2019). These disorders are a genuine medical challenge, particularly because of their perinatal mortality that is around 20% (Best et al., 2018; Normand et al., 2018). The rapid identification of a causal diagnosis is therefore essential for adapting prenatal/perinatal management and providing genetic counseling for the current pregnancy and any subsequent pregnancies. According to the recommendations of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, current prenatal genetic investigations are based on the standard karyotype and chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) in fetuses with one or more US anomalies (Committee on Genetics and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; Committee Opinion no. 2016). When a causal diagnosis is suspected on US anomalies, targeted gene sequencing or fluorescence in situ hybridization can also be performed. The CMA identifies causal diagnosis in around 6% of fetuses with US anomalies and normal karyotype (Levy and Wapner, 2018). Despite CMA and targeted analyses, about 70% of fetuses with MCA remain without molecular diagnosis (Best et al., 2018; Normand et al., 2018).

In the last decade, exome/genome sequencing (ES/GS) became the first-tier genetic test for the causal diagnosis of individuals with congenital anomalies. Postnatal clinical ES yield ranges from 30% to 50% depending on the clinical cohort and the strategy used (solo/trio) (Clark et al., 2018). Few countries have implemented or performed ES in prenatal settings, with a highly variable yield, ranging from 6% to 92% (Best et al., 2018; Ferretti et al., 2019; Guadagnolo et al., 2021). This variation reflects the heterogeneity of the fetal cohorts (which includes MCA or isolated malformations), the ES strategy (solo or trio), and on tests performed before ES (CMA, panel sequencing) (Diderich et al., 2021). Many challenges have to be overcome before ES can be used routinely in prenatal diagnosis, such as variant interpretation on partial phenotypes mostly based on imagery (US, X-ray, and/or magnetic resonance imaging), the poor prenatal description of Mendelian disorders (Aggarwal et al., 2020), and timing constraints inherent to the ongoing pregnancy.

When MCA is detected using prenatal US, a rapid etiological diagnosis can clarify the prognosis and help with decision-making, i.e., medical termination of pregnancy (ToP) or conservative procedures, as well as perinatal management. Here, we report the first French national pilot study of trio-ES in prenatal diagnosis. We evaluate the feasibility of delivering a result in less than 4 weeks for being compatible with pregnancy management, identify the technical or organizational obstacles, and evaluate the diagnostic yield of first-line trio-ES or after CMA and the effect on the continuation and monitoring of pregnancy.

2 Patients and methods

2.1 Patients

Pregnancies [10–32 weeks of gestation (WG)] were prospectively included following the detection of US anomalies, specifically i) two major anomalies, ii) one major and one minor anomaly, or iii) one anomaly (major or minor) with a strong suspicion of genetic cause (such as corpus callosum anomaly). Isolated nuchal translucency and hygroma were excluded. The definition of major and minor anomalies was based on a previous publication (DeSilva et al., 2016). Abnormalities were considered major if they had an impact on life expectancy, health status, and physical or social functioning (not applicable in prenatal settings) (DeSilva et al., 2016). On the contrary, abnormalities were considered minor when they had little or no impact on health and functioning. Because the identification of a causal diagnosis was intended to help in parental decision-making about the pregnancy, couples with an immediate referral for ToP were not included. Appropriate written consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the ethics committee that approved the ANDDI-PRENATOME study (NCT03964441). The clinical features were collected in an electronic case report form devoted to the study and by using Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO). Routine CMA was performed before or concomitantly to trio-ES. When ES was performed concomitantly to CMA, we referred to this strategy as the first-line (FL), and when ES was performed after CMA, we referred to it as the second-line (SL).

2.2 Exome sequencing and variant interpretation

Exome sequencing (ES) was performed using a trio-based strategy (fetus and both parents) from DNA extracted from amniotic fluid (15 ml) or fetal blood samples (6 ml) and parental blood samples (10 ml). The FastQ file generation was outsourced to a single sequencing platform (from DNA to raw data) and performed on a NovaSeq 6000 device (Illumina) with the enriched version of the TWIST-HCE (Human Core Exome) Kit (Twist Bioscience), according to the supplier's protocol. Vcf files were generated with the local bioinformatics solution (Tran Mau-Them et al., 2021). CNV detection was done with an Exome Hidden Markov Model (XHMM) (Fromer et al., 2012).

Each selected variant was ranked into one of the five categories from the ACMG recommendations (Richards et al., 2015). The variants that were considered pathogenic and likely pathogenic were returned to the referring clinicians, as were some variants of uncertain significance (VUS), when the multidisciplinary team considered that their implication in the phenotype was very likely and/or when additional investigations and/or family segregation could be performed to confirm or exclude the pathogenicity of the variants.

Variant confirmation and parental segregation were confirmed by Sanger sequencing (primers and conditions available on request). CNV was confirmed by qPCR (primers and conditions available on request) unless identified by CMA.

2.3 Analytical stages and pregnancy issues

To evaluate the time required to return the results (with confirmation for positives and without confirmation for negatives), we considered the day of arrival of the three samples (fetus and both parents) at the laboratory as day 0, since we observed outliers caused by shipment duration or delays in the reception of parental samples that were independent from our laboratory. At every step of the process, durations were measured from D0 to the end point (day of emailed molecular report), namely, from reception to outsourcing, from outsourcing to raw data reception, from raw data reception to vcf generation, from vcf generation to multidisciplinary meeting (MDM), from MDM to Sanger sequencing (if variant retained), and from Sanger sequencing to molecular report (end point). The fetal prognosis issued of molecular diagnosis, as well as of pregnancy outcome, was systematically collected.

3 Results

3.1 Patients

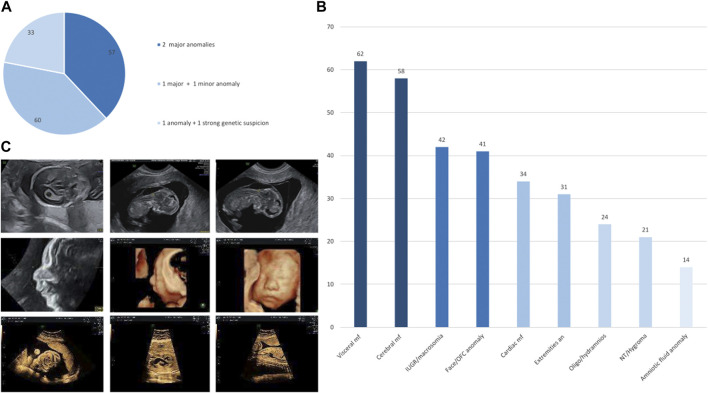

Between June 2019 and November 2021, we prospectively included 150 pregnancies from 19 different French centers (which included those on Réunion Island). Of the 150 couples, 111 (74%) were Caucasian and 6 (4%) were consanguineous. The term for pregnancies upon fetal sampling ranged from 10 to 31 WG (mean: 20 WG). Fetal ultrasound showed at least two major anomalies in 57/150 pregnancies (38%), one major and at least one minor anomaly in 60/150 pregnancies (40%), and one anomaly (major or minor) with a strong suspicion of genetic cause in 33/150 pregnancies (22%; Figure 1A). The ultrasound results included a wide spectrum of signs ranging from amniotic fluid anomaly in 14/150 pregnancies (9.3%) to visceral malformation in 62/150 pregnancies (41.3%) (Figure 1B). Isolated hygroma was seen on ultrasound in one consanguineous couple.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Percentage of fetuses included in the defined subgroups, namely, two major anomalies, one major and one minor anomaly, and one anomaly with a strong suspicion of genetic disorder. (B) Histograms of the distribution of anomalies in the entire cohort, ranging from the most frequent sign on the left to the most uncommon sign on the right. IUGR, intra uterine growth restriction; NT, nuchal translucency; OFC, occipitofrontal circumference. (C) Ultrasonography images of the fetus referred for persistent increased nuchal translucency with pathogenic truncating homozygous ASCC1 variant associated with a truncating homozygous variant of unknown significance in CSPP1 (top) and of the fetus referred for retrognathia, complex heart defect, and small stomach with a pathogenic truncating homozygous EFEMP2 variant associated with a truncating homozygous variant of unknown significance in RAG1 (middle and bottom).

3.2 Molecular results

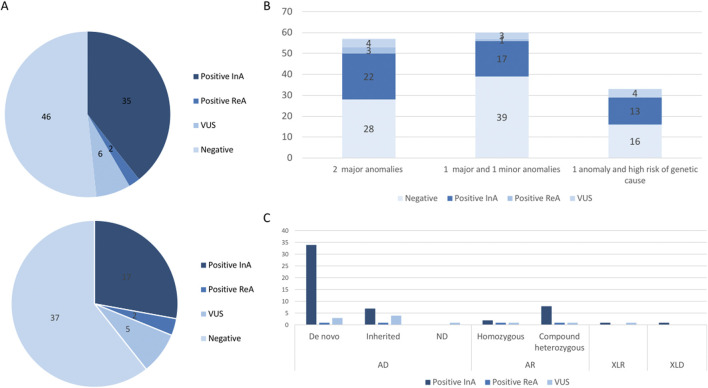

First-line trio-ES diagnostic strategy was performed in 89/150 fetuses. A causative molecular diagnosis (likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants) was identified in 35/89 fetuses in the initial analysis (39%; Figure 2A). CNV identification was concordant between trio-ES and CMA. Second-line trio-ES was performed in 61/150 fetuses, and a causative molecular diagnosis (likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants) was identified in 17/61 fetuses in the initial analysis (27%; Figure 2A). No additional causative CNV was identified by trio-ES. The diagnostic yield was the highest in the “2 major anomalies” subgroup with 22/57 (38%) fetuses being diagnosed, rising to 25/57 (43%) with positive reanalysis included (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

(A) Molecular results in the first-line trio-ES subgroup (top) and in the second-line trio-ES subgroup (below). CNV, copy number variant; InA, initial analysis; ReA, reanalysis; SNV, single nucleotide variant; VUS, variant of unknown significance. (B) Histograms of the molecular results stratified by a clinical subgroup, namely, two major anomalies, one major and one minor anomaly, and one anomaly with a strong suspicion of a genetic disorder. (C) Mode of inheritance for the identified variants and molecular results. AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; FL, first-line analysis; SL, second-line analysis; VUS, variant of unknown significance; XLD, X-linked dominant; XLR, X-linked recessive.

In total, trio-ES identified a causative molecular diagnosis (likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants) in the initial analysis in 52/150 fetuses (34%), which included SNV/indel in 43/52 (83%), CNV in 8/52 (15%), and SNV/CNV in 1/52 (2%; Table 1). Pathogenic variants involved in autosomal dominant disorders were identified in 40/52 fetuses, which included de novo (32/40) or inherited (6/40) variants and de novo mosaic CNV (2/40). The six inherited SNVs were transmitted by a symptomatic parent (COL1A2, IGF1R, and TBX3) or an asymptomatic parent (ACTB, EYA1, and GREB1L). Pathogenic variants involved in recessive disorders were identified in 10/52 fetuses, which included compound heterozygous SNV/indel variants (8/10) and homozygous SNVs (2/10). Pathogenic variants involved in X-linked dominant and recessive disorders were identified in 2/52 fetuses, which included one hemizygous SNV and one heterozygous SNV (Figure 2C). Of note, the causative variants in genes implicated in RASopathies were identified in 7/52 fetuses (13%). All seven fetuses had at least four US signs (6/7 with polyhydramnios, 5/7 with macrosomia, and 4/7 with renal anomalies), leading to ToP in 5/7 (4/5 before molecular results).

TABLE 1.

Positive molecular results and variants of unknown significance identified in the 150 fetuses of the cohort. *, positive reclassification; **, negative reclassification; ***, gene not involved in human disorder; #, fetus with a positive variant and variant of unknown significance.

| Fetus | Gene | Variant segregation | Inheritance | Genomic position (hg19) | Protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive variants in ES and CMA in parallel | |||||

| 1 | ACTB | Paternal mosaicism | Autosomal dominant | chr7:g.5568935C>A | p. (Gly74Cys) |

| 2 | ANKRD11 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr16:g.89349019G>A | p. (Arg1311*) |

| 3 | COL4A1 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr13:g.110827050C>A | p. (Gly1082Val) |

| 4 | COL4A1 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr13:g.110804766C>T | p. (Glu1615Lys) |

| 5 | DLL1 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr6:g.170598799delG | p. (Pro51Hisfs*72) |

| 6 | EYA1 | Maternally inherited | Autosomal dominant | chr8:g.72211426G>A | p. (Gln228*) |

| 7 | FGFR3 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr4:g.1806119G>A | p. (Gly380Arg) |

| 8 | FLT4 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr5:g.180040110C>T | p. (Gly1111Glu) |

| 9 | GRIN2B | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr12:g.13717487_13717488del | p. (His895Leufs*15) |

| 10 | GUSB | Maternally inherited | Autosomal recessive | chr7:g.65439612C>T | p. (Arg382His) |

| Paternally inherited | chr7:g.65444769G>A | p. (Leu176Phe) | |||

| 11 | HRAS | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr11:g.534,287_534288delinsAA | p. (Gly12Val) |

| 12 | IGF1R | Maternally inherited | Autosomal dominant | chr15:g.99459270_99459271dup | p. (Pro637Cysfs*6) |

| 13 | L1CAM | Maternally inherited | X-linked recessive | chrX:g.153135930G>A | p. (Pro240Leu) |

| 14 | MRPS22 | Paternally inherited | Autosomal recessive | chr3:g.139067142_139067143ins | p. (Ile161Asnfs*4) |

| Maternally inherited | chr3:g.139069025G>A | p. (Arg170His) | |||

| 15 | NHS | Maternally inherited | X-linked dominant | chrX:g. [17393987C>G; 17393989del] | p. [(Pro36Arg); (Leu38Cysfs*158)] |

| 16 | NIPBL | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr5:g.37057351C>T | p. (Gln2443*) |

| 17 | PTPN11 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr12:g.112915523A>G | p. (Asn308Asp) |

| 18 | SLC26A2 | Paternally and maternally inherited | Autosomal recessive | chr5:g.149359991C>T | p. (Arg279Trp) |

| 19 | SMO | Maternally inherited | Autosomal recessive | chr7:g.128845457T>C | p. (Phe252Leu) |

| Paternally inherited | chr7:g.128846362C>T | p. (Arg400Cys) | |||

| 20 | TBX3 | Paternally inherited | Autosomal dominant | chr12:g.115112386_115112393dup | p. (Glu452Glyfs*183) |

| 21 | TSEN54 | Maternally inherited | Autosomal recessive | chr17:g.73518081G>T | p. (Ala307Ser) |

| Paternally inherited | chr17:g.73518112delC | p. (Pro318Glnfs*24) | |||

| 22 | GREB1L | Maternally inherited | Autosomal dominant | chr18:g.19053061G> | p. (Arg751His) |

| 22 | Del 17q12 | Maternally inherited | Autosomal dominant | 17q12 (34842542–36104877)x1 | ND |

| 23 | CREBBP | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr16:g.3843495G>A | p. (Arg370*) |

| 24 | TUBB | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr6:g.30691800A>G | p. (Met321Val) |

| 25 | PTPN11 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr12:g.112910835A>G | p. (Ile282Val) |

| 26 | NFIA | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr1:g.61554154C>T | p. (Arg121Cys) |

| 27 | ZNF148 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr3:g.124951946G>A | p. (Gln542*) |

| 28 | del16p13.3 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | 16p13.3 (3767420–3860782)x1 | ND |

| 29 | del17q25.3 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | 17q25.3 (79539041–81052322)x1 | ND |

| 30 | del22q11.21 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | 22q11.2 (18893886–21386103)x1 | ND |

| 31 | dup15q11.2 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | 15q11.2 (22833523–25223593)x3 | ND |

| 32 | Trisomy 14 | De novo—somatic mosaicism | Autosomal dominant | ND | ND |

| 33 | Trisomy 17 | De novo—somatic mosaicism | Autosomal dominant | ND | ND |

| 34 | Trisomy 18 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | ND | ND |

| 35 | Tetrasomy 12p | De novo | Somatic mosaicism | 12p11.1-p12.33 (176047–34179852)x4 | ND |

| Positive variants in ES after normal CMA | |||||

| 1 | ASCC1# | Paternally and maternally inherited | Autosomal recessive | chr10:g.73970545dup | p. (Glu53Glyfs*19) |

| 2 | ASXL1 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr20:g.31022449dup | p. (Gly646Trpfs*12) |

| 3 | BRAF | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr7:g.140501302T>C | p. (Gln257Arg) |

| 4 | COL1A2 | Maternally inherited | Autosomal dominant | chr7:g.94053703G>C | p. (Gly874Ala) |

| 5 | DYNC2H1 | Paternally inherited | Autosomal recessive | chr11:g.103091449A>G | p. (Asp3015Gly) |

| Maternally inherited | chr11:g.103124080del | p. (Leu3370Cysfs*35) | |||

| 6 | GNB2 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr7:g.100275036A>G | p. (Lys89Glu) |

| 7 | KAT6B | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr10:g.76789043_76789052del | p. (Ser1487Argfs*59) |

| 8 | KMT2D | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr12:g.49445823delG | p. (Pro548Hisfs*382) |

| 9 | KMT2D | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr12:g.49428657dup | p. (Leu3432Phefs*36) |

| 10 | LINS1 | Maternally inherited | Autosomal recessive | chr15:g.101115226delT | p. (Glu200Lysfs*14) |

| Paternally inherited | chr15:g.101115265_101115266del | p. (Lys186Serfs*17) | |||

| 11 | MTOR | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr1:g.11189846A>C | p. (Phe1888Cys) |

| 12 | NRAS | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr1:g.115258748C>G | p. (Gly12Arg) |

| 13 | PGM1 | Paternally inherited | Autosomal recessive | NM_002633.2: c.423delA | p. (Ala142Glnfs*2) |

| Maternally inherited | NM_002633.2:c.157_158delinsG | p. (Gln53Glyfs*15) | |||

| 14 | PPM1D | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr17:g.58740467C>T | p. (Arg458*) |

| 15 | SOS1 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr2:g.39250269C>T | p. (Gly434Arg) |

| 16 | SOS1 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr2:g.39249914G>A | p. (Arg552Lys) |

| 17 | SCYL2 | Paternally inherited | Autosomal recessive | chr12:g.100676845delG | p. (Asp33Metfs*13) |

| Maternally inherited | chr12:g.100676924dup | p. (Glu60Glyfs*8) | |||

| Variants of unknown significance in ES and CMA in parallel | |||||

| 1 | NUP188* | Maternally inherited | Autosomal recessive | chr9:g.131760903G>A | p.? |

| Paternally inherited | chr9:g.131745626_131745627delinsG | p. (Cys617Trpfs*2) | |||

| 2 | EFEMP2* | Paternally and maternally inherited | Autosomal recessive | chr11:g.65638118A>G | p. (Cys127Arg) |

| RAG1 | Paternally and maternally inherited | Autosomal recessive | chr11:g.36596621C>G | p. (Tyr589*) | |

| 3 | CUX1 | Maternally inherited | Autosomal dominant | chr7:g.101921327C>A | p. (Tyr541*) |

| 4 | DLL1 | Maternally inherited | Autosomal dominant | chr6:g.170597444C>A | p. (Gly185*) |

| 5 | DNAH11 | Maternally inherited | Autosomal recessive | chr7:g.21627820G>T | p.? |

| Paternally inherited | chr7:g.21856224G>A | p. (Arg3491His) | |||

| 6 | GREB1L | Maternally inherited | Autosomal dominant | chr18:g.19019482A>T | p. (Asp278Val) |

| 7 | del1q21.1 | ND | Autosomal dominant | 1q21.1 (145414780–145826931)x1 | ND |

| 8 | del6p21.32 (BRD2***) | De novo | Autosomal dominant | 6p21.32 (32940674–32947911)x1 | ND |

| Variants of unknown significance in ES after normal CMA | |||||

| 1 | CSPP1# | Paternally and maternally inherited | Autosomal recessive | chr8:g.67986545_67986546del | p. (Lys56Serfs*6) |

| 2 | FGF8* | Paternally inherited | Autosomal dominant | chr10:g.103530204C>T | p. (Arg195Gln) |

| 3 | MYCN* | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr2:g.16082365C>T | p. (Pro60Leu) |

| 4 | dupXq28 (IDS**) | Maternally inherited | X-linked recessive | Xq28 (148564275–148798438)x3 | ND |

| 5 | KAT7*** | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr17:g.47900657A>G | p.Ser494Gly |

| 6 | KMT2E | Maternally inherited | Autosomal dominant | chr7:g.104753422del | p. (His1740Profs*132) |

| 7 | LZTR1 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | chr22:g.21342341A>G | p. (Asn148Ser) |

| dup1q21.1-1q21.2 | De novo | Autosomal dominant | 1q21.1q21.2 (146397357–148344744)x3 | ND | |

In one of the 52 fetuses, a dual diagnosis was obtained with the identification of a GREB1L pathogenic missense variant associated with a partial heterozygous deletion of chromosome 17 encompassing HNF1B.

In 16/150 fetuses (11%), trio-ES identified interesting VUS (Table 1). Variants in 3/16 fetuses were returned to the clinician during pregnancy asking for additional phenotypical features and/or to share data, leading to the reclassification as causative. For a FGF8 sporadic missense variant, brain MRI identified lobar holoprosencephaly, supporting the pathogenicity of the variant and leading to ToP because of the poor neurodevelopmental prognosis. For a MYCN sporadic missense variant, only one living patient had previously been reported with a similar phenotype and a causative missense variant located in the same protein region (Kato et al., 2019). ToP was performed because of the MCA phenotype being associated with bilateral postaxial polydactyly, macrocephaly (99th centile), lateral ventricles at the normal limits, and hydramnios. Fetal autopsy allowed specifying the phenotype and international data-sharing looked for recurrence and genotype–phenotype correlation. Ultimately, this team performed functional assays that confirmed the pathogenic role of our variant after pregnancy outcome (manuscript in progress). For an EFEMP2 homozygous missense variant, postnatal clinical examination confirmed cutis laxa, with the knowledge of a similar phenotype in a previously deceased fetus, highly suggestive of an autosomal recessive disorder in a consanguineous family. In 1/16 fetuses, additional investigations led to reclassify the VUS as likely benign. A 234.16 Kb maternally inherited duplication, located in Xq28, possibly resulted in an IDS complex mechanism leading to loss of function (Zanetti et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2019), but iduronate-sulfatase enzymatic activity was normal. In 5/16 fetuses with interesting VUS, additional investigations (reverse phenotyping of the carrying asymptomatic parent) were not contributive to variant reclassification (CUX1, DLL1, KMT2E, and DNAH11).

In addition, trio-ES identified two CNVs classified as “Variable Expression and Incomplete Penetrance” associated with an increased risk of neurodevelopmental disorders (Table 1). These were not reported to the clinicians.

In two fetuses with a causative molecular diagnosis (EFEMP2, ASCC1), trio-ES also identified noteworthy pathogenic variants not linked to the prenatal clinical presentation (Table 1). In the first fetus with the causative homozygous EFEMP2 variant, a homozygous pathogenic truncating RAG1 variant was also identified. Causative biallelic RAG1 truncating variants have been implicated in a postnatal spectrum of severe immunological disorders (Meshaal et al., 2019). In the second fetus (15 WG) with isolated persistent nuchal translucency and a causative homozygous ASCC1 variant, a homozygous pathogenic truncating CSPP1 variant was also identified. Causative biallelic CSPP1 variants have been implicated in Joubert syndrome (MIM:615636) (Tuz et al., 2014). Since the fetus was addressed in the early stages of pregnancy, the phenotypical symptoms of Joubert syndrome were undetectable. Despite the impossibility in considering the RAG1 and CSPP1 pathogenic variants as causative factors for the prenatal presentation, both results were returned to the clinicians because of the importance for genetic counseling due to the autosomal recessive mode of inheritance.

After the publication of the novel implication of NUP188 in a human disorder, the targeted reanalysis of a fetus in our database identified causative compound heterozygous truncating variants after the outcome of pregnancy, 5 months after the first report (Muir et al., 2020).

Finally, considering the initial positive diagnosis and VUS reclassification, a causative diagnosis was made in 56/150 pregnancies (37%). The molecular results and associated phenotypes are described in Supplementary Table S1.

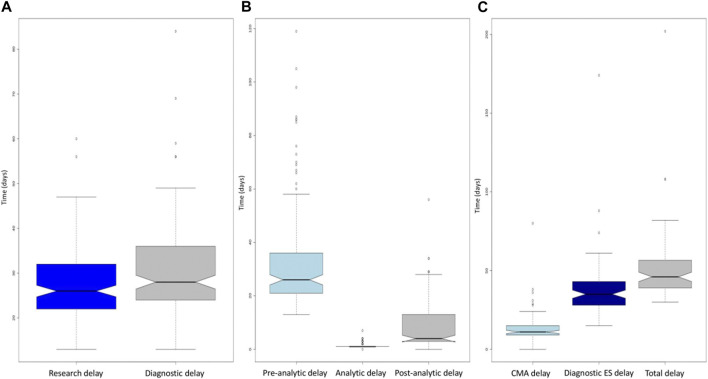

3.3 Analytical stages

For the 150 fetuses, the median duration from the reception of the three samples to the emailing of the molecular report before Sanger confirmation was 26 days [13–60] (Figure 3A). The overall median duration which included Sanger confirmation was 28 days [13–84] for the 150 fetuses, 27 days [13–47] for the negative molecular results and 39 days [18–84] for the positive molecular results. This median duration was increased by 12 days because of the requirement for validation of results by a second orthogonal method to be eligible for medical ToP (Figure 3A). The median pre-analytical stage (from sampling date to raw data reception) was 26 days (13–119), the median analytical stage (from raw data reception to the available vcf file) was 1 day (1–7), and the post-analytical stage (from the available vcf file for interpretation to report) was 4 days (0–56) (Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3.

(A) Boxplot of the time required to obtain the report without confirmation (dark blue) and with confirmation (gray) for the entire cohort. The diagnosis delay boxplot is above the research delay one, corresponding to the mandatory diagnostic validation. (B) Boxplot of the pre-analytical (light blue), analytical (dark blue), and post-analytical (gray) turnaround times for the entire cohort. Note the minimal dispersion of the analytical boxplot when compared to the pre- and post-analytical ones. (C) Boxplots of the turnaround times for CMA (light blue), exome (dark blue), and combined CMA and exome (gray). CMA, chromosomal microarray. For the three boxplots, the threshold represents the minimum value, first quartile, mean, third quartile, and maximum. The dots represent outliers.

For first-line trio-ES (81/150), the mean differential duration between the two results was 20 days (0–66). In two pregnancies, the trio-ES result occurred before the CMA. In all other cases, the CMA results were reported first.

3.4 Pregnancy outcomes

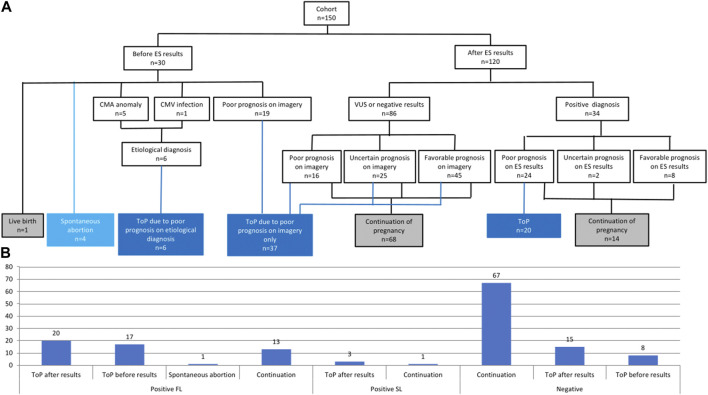

Among the 150 pregnancies, 30 ended before the final molecular report was received (1 live birth, 4 spontaneous abortions, and 25 ToP) (Figure 4A). ToP was performed because the US signs progressed in favor of a poor diagnosis/prognosis (19/25), chromosomal anomalies were identified by CMA (5/25), or due to cytomegalovirus infection (1/25; Figure 4A).

FIGURE 4.

(A) Flowchart of pregnancy issue results separated between the availability of the ES results. CMA, chromosomal micro array; CMV, cytomegalovirus; ES, exome sequencing; ToP, termination of pregnancy; VUS, variants of unknown significance. (B) Pregnancy outcomes in the entire cohort depending on molecular results (positive or negative). FL, first line; SL, second line; ToP, termination of pregnancy.

Among the 120 other pregnancies in which the ES result was returned during pregnancy, two-thirds of couples (82/120) decided to continue the pregnancy, mainly because of the favorable or uncertain prognosis on imagery with a negative or VUS ES result (66/82), and also when the positive ES result gave a favorable prognosis (8/82). One-third of the couples (38/120) decided to undergo ToP procedure because of the poor prognosis associated with the ES result (20/38) or the poor or uncertain prognosis on imagery despite negative ES results (18/38) (Figure 4A). Among the 34 couples with positive ES results, 14 decided to continue the pregnancy because of a favorable prognosis on ES results (8/14), and also despite uncertain (2/14) or poor prognosis (4/4) on ES results. ES results helped considerably with parental decision-making in 94/120 pregnancies (78%). More specifically, positive ES results helped decision-making in 28/34 pregnancies (82%) since poor prognosis led to ToP in 20/34 cases and favorable prognosis led to the continuation of pregnancy in 8/34 cases. Negative or VUS ES results helped with decision-making in 66/86 pregnancies (77%), leading to continuation of pregnancy when the imagery suggested uncertain or favorable prognosis (Figure 4A).

Five of the 20 couples (25%) who obtained causative molecular diagnosis and underwent ToP asked for prenatal molecular diagnosis after confirming a subsequent pregnancy. For three families with autosomal or X-linked dominant disorders (GREB1L, NHS, and PTPN11), extended family segregation was performed by Sanger sequencing, resulting in a molecular diagnosis for six additional individuals.

4 Discussion

We report the results of the first French national multicenter study of trio-ES implementation in routine prenatal diagnosis.

This study demonstrates the feasibility of centralizing testing for multiple clinical centers in a single molecular diagnostics laboratory. A total of 150 prenatal samples were sent from 19 different French clinical centers (which included one in Reunion Island, located 9,000 km away from the laboratory) to a single laboratory that processed samples into DNA, performed bioinformatics analyses and variant interpretation, and edited the final reports. Only the sequencing step was outsourced to a single sequencing platform (from DNA to raw data). There is a financial advantage to this approach since not all laboratories can afford to invest in equipment or personnel dedicated to a fast circuit. Indeed, the discontinuous arrival of urgent samples requires either a sustained standard flow with on-demand insertion of samples or the availability of a dedicated second sequencing device used only for urgent requests, thus creating additional costs. Exclusively outsourcing data production remains economically affordable for most laboratories, which can still maintain bioinformatics and biological analysis expertise on site. A disadvantage is that additional time is then required since the outsourcing step is one of the longest in the process (median of 14 days) (Figure 3A). Although raw data outsourcing appears fast, reporting time for trio-ES could be reduced with a local solution. Sanger confirmation is the second longest step in the process (median of 14 days) (Figure 3A). This could call into question the need to confirm trio-ES in the context of pregnancy when quality metrics are met. Indeed, Sanger confirmation of variants identified by NGS seems to have equal or limited utility (Beck et al., 2016; Fridman et al., 2021). Information about Sanger validation is available in only 8 of the 11 published prenatal studies (Supplementary Table S2): 5 studies used it in all cases, 2 upon inheritance or due to quality metrics, and 1 in no case. Nevertheless, a final molecular report was returned with a median duration of 28 days, which remains compatible with decision-making during pregnancy. In one case, the total duration was of 84 days. When looking back at the data, this outlier could be explained by several accumulative factors, namely, i) the receipt of the sample in mid-December, during the holiday period, with insufficient staff, ii) the period of 2020, when France was in the second stage of the COVID-19 epidemic, and iii) national curfew imposed in mid-January 2021. All these factors forced the actors of this project to adapt to the exceptional circumstances in a degraded mode and to urgently set up new organizations, which delayed the processing of this particular sample.

The overall diagnostic yield of first-line trio-ES in our cohort (41%) reflects the rate that could be expected in routine prenatal diagnosis on malformations detected by prenatal ultrasound. While this rate is higher than in the larger published cohorts (Supplementary Table S2), studies with a diagnostic yield inferior to 20% performed on larger cohorts might be explained by less severe US anomalies, particularly isolated hygroma or increased nuchal translucency (Best et al., 2018; Ferretti et al., 2019). For these reasons, our study included only fetuses with at least two US anomalies or with one US anomaly associated with a minor or major anomaly that is known to be frequently linked to a genetic etiology, excluding isolated hygroma or increased nuchal translucency. Finally, the diagnostic yield ranged from 24% to 33% in the cohorts with similar inclusion criteria (Supplementary Table S2), which suggests that prenatal ES should not be employed in cases of isolated hygroma or increased nuchal translucency (Mellis et al., 2022; Pauta et al., 2022).

Interestingly, variants involved in RASopathies were detected in 13% of our cohort, which is consistent with previous prenatal cohorts suspected of such syndromes [diagnostic yield ranging from 9.5% to 14% (Stuurman et al., 2019; Mangels et al., 2021; Scott et al., 2021)].

De novo variants with an autosomal mode of inheritance accounted for the majority of causative diagnoses (32/52; 61%), which included 14 missense variants that would have been difficult to interpret without parental segregation. Therefore, a trio-based ES strategy should be favored in a context of prenatal diagnosis, even if the cost is higher than that of solo-based strategy. Indeed, the major interest of trio-based ES remains the rapid identification of sporadic variants (Gabriel et al., 2021). Moreover, trio-ES makes it possible to determine the phase of biallelic compound heterozygous variants. It also helps to highlight interesting VUS such as the MYCN missense variant, which was retained because of de novo occurrence and the absence from the Genome Aggregation Database. MYCN loss-of-function variants are known to be implicated in the Feingold disorder (microcephaly and absent/hypoplastic phalanx), with a mirror phenotype of the fetus (macrocephaly and polydactyly). One living individual has been reported with a similar phenotype and close missense variant (Richards et al., 2015). Data sharing and functional studies led to reclassify this variant as causative in a new MYCN-related phenotype (manuscript in progress).

It is also important to keep in mind that the extreme spectrum of Mendelian disorders remains elusive in prenatal settings, with variant interpretation based mostly on US signs and sometimes X-rays or MRI. Since some organs are in formation and maturation during fetal development, the identification of molecular causes and genotype–phenotype correlations can be difficult, requiring additional imaging/tests. For example, for the FGF8 missense variant, brain MRI subsequently confirmed complete lobar holoprosencephaly, further confirming the pathogenicity of the variant. While additional tests can validate the pathogenicity of a variant, some results can also exclude them, for instance, the normal iduronate-sulfatase activity that excluded the pathogenicity of the IDS variant.

The diagnostic yield of first-line trio-ES was 9% for causative CNV (8/89), similar to current prenatal CMA results since pathogenic CNV were identified in 3%–6.5% of the fetuses with normal karyotypes (Callaway et al., 2013). Moreover, CMA and trio-ES were fully concordant for causal CNV identification, which may put the role of CMA in prenatal health up for debate. Indeed, if CMA had been performed as a first-line test, trio-ES would have been delayed by several days or weeks for the large majority of couples with normal CMA results (75/80; 93%). In addition, there is a risk of not performing ES after positive CMA, ruling out the possibility in identifying dual diagnosis such as the 17q12 deletion and a pathogenic inherited missense GREB1L in a fetus with polyhydramnios and enlarged kidneys. Since the deletion encompasses HNF1B, which can involve renal cysts, the GREB1L variant would have been missed if the CMA had been performed before trio-ES. The main advantage of CMA remains that it has faster processing time than ES (CMA reports emitted faster than ES-trio in 97% cases). In the prenatal setting, performing trio-ES as a first-line test concomitantly to CMA or CMA after negative trio-ES (depending on the CNV detection pipeline used for ES) could be suggested.

Despite concerns about the time required for the analyses, almost all reports were returned before the predicted term of pregnancy (except for NUP188, which was identified after ToP), which means that they could theoretically have been used in prenatal management. Nevertheless, 23/150 pregnancies (15%) were terminated before the molecular report was obtained because an unfavorable fetal prognosis was identified on US, emphasizing the need to shorten turnaround times. However, it is worth reassessing the initial indications for prenatal ES. Indeed, the analysis of ES data with detailed phenotyping after fetal autopsy and without the pressure of an emergency context would be easier for clinical laboratories than performing prenatal ES. The indications of prenatal ES should be therefore discussed by a multidisciplinary team and offered to couples when fetal prognosis based on ultrasound features remains uncertain and a molecular diagnosis would genuinely help with decision-making. For example, in a 25 WG fetus with a highly variable fetal prognosis (corpus callosum agenesis and ventriculomegaly without any other malformations) (Yeh et al., 2018; Bernardes da Cunha et al., 2021), ES evidenced a causative maternally inherited hemizygous L1CAM missense variant with a poor neurodevelopmental prognosis (MIM:304100), leading to ToP after the molecular result. The heterozygous mother may also benefit from early prenatal diagnosis for future pregnancies. In a 30 WG fetus with intrauterine growth restriction and hypotelorism leading to unknown fetal prognosis, ES evidenced a causative heterozygous IGF1R truncating variant inherited from the mother, who was of short stature. This finding confirmed the diagnosis of resistance to insulin-like growth factor I (MIM:270450), which has a favorable neurodevelopmental prognosis, and the pregnancy was therefore maintained (Supplementary Table S1).

Altogether, diagnostic results were returned to 120/150 (80%) couples with ongoing pregnancies, which included 34 with a causative diagnosis and 86 with negative or VUS results. In 28/34 fetuses with causative diagnosis (82%), the results were helpful for pregnancy management: a poor prognosis led to ToP while a reassuring prognosis led to the continuation of pregnancy with monitoring. Among the 86 fetuses with no causal diagnosis, parents tended to continue with the pregnancy (68/86; 79%). Altogether, the results had a potential effect on pregnancy management in 78% of cases, a rate which is similar to a previously published report (67%) (Dempsey et al., 2021).

The VUS of interest were returned to couples in 17/150 pregnancies (11%) because their implication in the phenotype seemed very likely and/or additional investigations could be performed to confirm or rule out pathogenicity. Finally, 4/17 VUS were reclassified as pathogenic and 1/17 as likely benign. Returning VUS to the couples in prenatal setting remains difficult due to the uncertain involvement of these variants in fetal phenotypes (Narayanan et al., 2018; Richardson and Ormond, 2018; Werner-Lin et al., 2019; Harding et al., 2020). Therefore, it will be important to establish guidelines to specify the VUS that should be returned to couples. VUS should also be discussed on a case-by-case basis when laboratories do not have clear policies about reporting during pregnancy. This question appears to be up for debate since two previous studies systematically reported VUS, whereas three did not, and five studies (including ours) decided on a case-by-case basis, highlighting the complexity of managing these data in the prenatal period and the need for consensual guidelines (Supplementary Table S2).

Moreover, two cases involving consanguineous couples highlighted particular difficulties when diagnosing several autosomal recessive syndromes with unusual or undetectable signs on prenatal US (EFEMP2-RAG1 and ASCC1-CSPP1). Indeed, RAG1 is involved in a severe spectrum of immunodeficiencies that can only be detected after birth (MIM:601457), while CSPP1 is involved in Joubert syndrome (MIM:615636) for which prenatal signs cannot be detected by US at early stages. These examples show the potential interest of detecting variants that do not account for prenatal US signs but could be considered actionable incidental findings for genetic counseling (25% chance of recurrence for subsequent pregnancies). This also emphasizes the need for laboratories performing prenatal ES to carefully establish their policies regarding incidental findings (Vora et al., 2020; Basel-Salmon and Sukenik-Halevy, 2022; Vears and Amor, 2022).

In conclusion, prenatal trio-ES provides a considerable diagnostic yield in fetuses with US abnormalities and appears significantly helpful for couples seeking guidance regarding pregnancy management. It could be therefore routinely implemented when the fetal prognosis remains uncertain on US features and molecular diagnosis would support decision-making. However, the indications should be discussed by a multidisciplinary team. The complete concordance between trio-ES and CMA for diagnosis of CNV suggests that trio-ES is an appropriate first-line test to obtain a causal diagnosis as quickly as possible. Medico-economic studies would now be useful to better understand the cost–benefit ratio of such a rapid prenatal trio strategy in fetuses with US signs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the IntegraGen society and the University of Burgundy Centre de Calcul (CCuB) for technical support and management of the informatics platform and the GeneMatcher platform for data sharing. The authors wish to thank Suzanne Rankin (Dijon Bourgogne University Hospital) for reviewing the English manuscript. Molecular studies with informed consent were done in the framework of the DISCOVERY project (2016-A01347-44). Samples were part of the GAD collection DC 2011-1332. Several authors of this publication are members of the European Reference Network for Developmental Anomalies and Intellectual Disability (ERN-ITHACA).

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from Dijon University Hospital, the ISITE-BFC (PIA ANR), the European Union through the FEDER programs, and the AnDDI-Rares network for ES performed in this study.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/. Accession number: SUB12873630.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Burgundy: GAD n° DC 2011-1332. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants and legal guardian/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to one or several of the following steps; conceptualization: FT, YD, M-LA, CB, and CR; data curation: FT, CD, OB, CC, FP, AG, GV, A-MG, AB, PB, CW, CD, and CR; investigation: FT, AP, HS, AB, AV, A-MG, JD, SN, NB, AS, SM, NM, TR, PS, ES, CVD, OB, CC, FP, ML, SN, CR, CP, AZ, ES, A-MG, DB, GM, MF, AL, CQ, LP, SO, AG, GV, A-MG, AB, AP, JA, CA, PB, CW, CD, SM, MV, MN, BI, JA, RD, NG, MG, M-LJ, ES, PM, FP, MJ, CF, SS, and CP; methodology: FT, YD, MB, ET, MA, CB, CP, LF, and CR; resources: YD, MB, and ET; software: YD, MB, and ET; validation: FT and CR; visualization: CW; writing—review and editing: FT, CR, FP, CW, MV, M-LJ, YD, LF, and CR.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, editors, and reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2023.1099995/full#supplementary-material

Entire fetal cohort with clinical signs, CMA subgroup, molecular results and pregnancy management. CC: Corpus Callosum; CCA: Corpus Callosum agenesis; CMA: Chromosomal microarray; IUGR: Intrauterine growth restriction; INT: Increased nuchal translucency; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; PH: Polyhydramnios; US: Ultrasound.

Previous studies with fetal cohort, genetic investigations, molecular results, variants of unknown significance and Sanger confirmation policy, and turnaround time. CC: Corpus Callosum; CMA: Chromosomal microarray; ES: Exome sequencing; NR: Not reported; QC: quality control; VUS: Variants of unknown significance.

References

- Aggarwal S., Vineeth V. S., Das Bhowmik A., Tandon A., Kulkarni A., Narayanan D. L., et al. (2020). Exome sequencing for perinatal phenotypes: The significance of deep phenotyping. Prenat. Diagn 40, 260–273. 10.1002/pd.5616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basel-Salmon L., Sukenik-Halevy R. (2022). Challenges in variant interpretation in prenatal exome sequencing. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 65, 104410. 10.1016/j.ejmg.2021.104410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck T. F., Mullikin J. C., Biesecker L. G. (2016). Systematic evaluation of sanger validation of next-generation sequencing variants. Clin. Chem. 62, 647–654. 10.1373/clinchem.2015.249623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardes da Cunha S., Carneiro M. C., Miguel Sa M., Rodrigues A., Pina C. (2021). Neurodevelopmental outcomes following prenatal diagnosis of isolated corpus callosum agenesis: A systematic review. Fetal Diagn Ther. 48, 88–95. 10.1159/000512534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best S., Wou K., Vora N., Van der Veyver I. B., Wapner R., Chitty L. S. (2018). Promises, pitfalls and practicalities of prenatal whole exome sequencing. Prenat. Diagn 38, 10–19. 10.1002/pd.5102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway J. L., Shaffer L. G., Chitty L. S., Rosenfeld J. A., Crolla J. A. (2013). The clinical utility of microarray technologies applied to prenatal cytogenetics in the presence of a normal conventional karyotype: A review of the literature. Prenat. Diagn 33, 1119–1123. 10.1002/pd.4209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark M. M., Stark Z., Farnaes L., Tan T. Y., White S. M., Dimmock D., et al. (2018). Meta-analysis of the diagnostic and clinical utility of genome and exome sequencing and chromosomal microarray in children with suspected genetic diseases. NPJ Genom Med. 3, 16. 10.1038/s41525-018-0053-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Genetics and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Committee Opinion No (2016). Committee opinion No.682: Microarrays and next-generation sequencing technology: The use of advanced genetic diagnostic tools in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet. Gynecol. 128, e262–e268. 682. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey E., Haworth A., Ive L., Dubis R., Savage H., Serra E., et al. (2021). A report on the impact of rapid prenatal exome sequencing on the clinical management of 52 ongoing pregnancies: A retrospective review. BJOG 128, 1012–1019. 10.1111/1471-0528.16546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSilva M., Munoz F. M., Mcmillan M., Kawai A. T., Marshall H., Macartney K. K., et al. (2016). Congenital anomalies: Case definition and guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine 34, 6015–6026. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diderich K. E. M., Romijn K., Joosten M., Govaerts L. C. P., Polak M., Bruggenwirth H. T., et al. (2021). The potential diagnostic yield of whole exome sequencing in pregnancies complicated by fetal ultrasound anomalies. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 100, 1106–1115. 10.1111/aogs.14053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti L., Mellis R., Chitty L. S. (2019). Update on the use of exome sequencing in the diagnosis of fetal abnormalities. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 62, 103663. 10.1016/j.ejmg.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridman H., Bormans C., Einhorn M., Au D., Bormans A., Porat Y., et al. (2021). Performance comparison: Exome sequencing as a single test replacing sanger sequencing. Mol. Genet. Genomics 296, 653–663. 10.1007/s00438-021-01772-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromer M., Moran J. L., Chambert K., Banks E., Bergen S. E., Ruderfer D. M., et al. (2012). Discovery and statistical genotyping of copy-number variation from whole-exome sequencing depth. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 91, 597–607. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel H., Korinth D., Ritthaler M., Schulte B., Battke F., von Kaisenberg C., et al. (2021). Trio exome sequencing is highly relevant in prenatal diagnostics. Prenat. Diagn 42, 845–851. 10.1002/pd.6081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadagnolo D., Mastromoro G., Di Palma F., Pizzuti A., Marchionni E. (2021). Prenatal exome sequencing: Background, current practice and future perspectives-A systematic review. Diagn. (Basel) 11, 224. 10.3390/diagnostics11020224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding E., Hammond J., Chitty L. S., Hill M., Lewis C. (2020). Couples experiences of receiving uncertain results following prenatal microarray or exome sequencing: A mixed-methods systematic review. Prenat. Diagn 40, 1028–1039. 10.1002/pd.5729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K., Miya F., Hamada N., Negishi Y., Narumi-Kishimoto Y., Ozawa H., et al. (2019). MYCN de novo gain-of-function mutation in a patient with a novel megalencephaly syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 56, 388–395. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy B., Wapner R. (2018). Prenatal diagnosis by chromosomal microarray analysis. Fertil. Steril. 109, 201–212. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H. Y., Tu R. Y., Chern S. R., Lo Y. T., Fran S., Wei F. J., et al. (2019). Identification and functional characterization of IDS gene mutations underlying Taiwanese hunter syndrome (mucopolysaccharidosis type II). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 114. 10.3390/ijms21010114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangels R., Blumenfeld Y. J., Homeyer M., Mrazek-Pugh B., Hintz S. R., Hudgins L. (2021). RASopathies: A significant cause of polyhydramnios? Prenat. Diagn 41, 362–367. 10.1002/pd.5862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellis R., Eberhardt R. Y., Hamilton S. J., Page C., McMullan D. J., Kilby M. D., et al. (2022). Fetal exome sequencing for isolated increased nuchal translucency: Should we be doing it? BJOG 129, 52–61. 10.1111/1471-0528.16869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshaal S. S., El Hawary R. E., Abd Elaziz D. S., Eldash A., Alkady R., Lotfy S., et al. (2019). Phenotypical heterogeneity in RAG-deficient patients from a highly consanguineous population. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 195, 202–212. 10.1111/cei.13222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir A. M., Cohen J. L., Sheppard S. E., Guttipatti P., Lo T. Y., Weed N., et al. (2020). Bi-Allelic loss-of-function variants in NUP188 cause a recognizable syndrome characterized by neurologic, ocular, and cardiac abnormalities. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 106, 623–631. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan S., Blumberg B., Clayman M. L., Pan V., Wicklund C. (2018). Exploring the issues surrounding clinical exome sequencing in the prenatal setting. J. Genet. Couns. 27, 1228–1237. 10.1007/s10897-018-0245-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normand E. A., Braxton A., Nassef S., Ward P. A., Vetrini F., He W., et al. 2018, Clinical exome sequencing for fetuses with ultrasound abnormalities and a suspected Mendelian disorder. Genome Med. (201) 10:74. 10.1186/s13073-018-0582-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauta M., Martinez-Portilla R. J., Borrell A. (2022). Diagnostic yield of next-generation sequencing in fetuses with isolated increased nuchal translucency: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 59, 26–32. 10.1002/uog.23746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S., Aziz N., Bale S., Bick D., Das S., Gastier-Foster J., et al. (2015). Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of medical genetics and Genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet. Med. 17, 405–424. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A., Ormond K. E. (2018). Ethical considerations in prenatal testing: Genomic testing and medical uncertainty. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 23, 1–6. 10.1016/j.siny.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott A., Di Giosaffatte N., Pinna V., Daniele P., Corno S., D'Ambrosio V., et al. (2021). When to test fetuses for RASopathies? Proposition from a systematic analysis of 352 multicenter cases and a postnatal cohort. Genet. Med. 23, 1116–1124. 10.1038/s41436-020-01093-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuurman K. E., Joosten M., van der Burgt I., Elting M., Yntema H. G., Meijers-Heijboer H., et al. (2019). Prenatal ultrasound findings of rasopathies in a cohort of 424 fetuses: Update on genetic testing in the NGS era. J. Med. Genet. 56, 654–661. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran Mau-Them F., Duffourd Y., Vitobello A., Bruel A. L., Denommé-Pichon A. S., Nambot S., et al. (2021). Interest of exome sequencing trio-like strategy based on pooled parental DNA for diagnosis and translational research in rare diseases. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 30, e1836. 10.1002/mgg3.1836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuz K., Bachmann-Gagescu R., O'Day D. R., Hua K., Isabella C. R., Phelps I. G., et al. (2014). Mutations in CSPP1 cause primary cilia abnormalities and Joubert syndrome with or without Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 94, 62–72. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vears D., Amor D. J. (2022). A framework for reporting secondary and incidental findings in prenatal sequencing: When and for whom? Prenat. Diagn 42, 697–704. Epub ahead of print. 10.1002/pd.6097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vora N. L., Gilmore K., Brandt A., Gustafson C., Strande N., Ramkissoon L., et al. (2020). An approach to integrating exome sequencing for fetal structural anomalies into clinical practice. Genet. Med. 22, 954–961. 10.1038/s41436-020-0750-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner-Lin A., Mccoyd J. L. M., Bernhardt B. A. (2019). Actions and uncertainty: How prenatally diagnosed variants of uncertain significance become actionable. Hastings Cent. Rep. 49 (1), S61–S71. 10.1002/hast.1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik M. H., Schwartz T. S., Thiele K. E., Paterson H., Stadelmaier R., Mullen T. E., et al. (2019). Infant mortality: The contribution of genetic disorders. J. Perinatol. 39, 1611–1619. 10.1038/s41372-019-0451-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh H. R., Park H. K., Kim H. J., Ko T. S., Won H. S., Lee M. Y., et al. (2018). Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with prenatally diagnosed corpus callosal abnormalities. Brain Dev. 40, 634–641. 10.1016/j.braindev.2018.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanetti A., Tomanin R., Rampazzo A., Rigon C., Gasparotto N., Cassina M., et al. (2014). A hunter patient with a severe phenotype reveals two large deletions and two duplications extending 1.2 Mb distally to IDS locus. JIMD Rep. 17, 13–21. 10.1007/8904_2014_317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Entire fetal cohort with clinical signs, CMA subgroup, molecular results and pregnancy management. CC: Corpus Callosum; CCA: Corpus Callosum agenesis; CMA: Chromosomal microarray; IUGR: Intrauterine growth restriction; INT: Increased nuchal translucency; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; PH: Polyhydramnios; US: Ultrasound.

Previous studies with fetal cohort, genetic investigations, molecular results, variants of unknown significance and Sanger confirmation policy, and turnaround time. CC: Corpus Callosum; CMA: Chromosomal microarray; ES: Exome sequencing; NR: Not reported; QC: quality control; VUS: Variants of unknown significance.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/. Accession number: SUB12873630.