Abstract

This research paper is a stringent analysis of the condition of commercial sex workers in India and what is happening to them in this pandemic-stricken time. The study details their economic condition and what is forcing them to borrow money from treacherous lenders despite knowing the risks behind it. Apart from being exploited financially, they are also becoming vulnerable for sexual, emotional, and physical exploitation, worsening their situation even further. The research findings show that 90% of commercial sex workers in red light areas will be forced into a debt trap that is non-repayable in their lifetime, making it a massive movement of commercial sex workers entering into bonded labour, another form of modern-day slavery. Apart from the financial peril, poverty is forcing them to be in a situation of major health hazard. Being deprived of customers for so long, they might be forced to work in this uncertain situation making it an optimum ground for a super-spread of the virus. A rapid assessment method has been used to collect the data from numerous commercial sex workers across the nation. The collected data are analysed using qualitative analysis and also visualized for better understanding. As a means to provide tangible alternative solutions to the problem, the study strongly recommends occupational training programs for commercial sex workers that provide a transition into alternative livelihoods, government action against predatory high-interest loans, and the redevelopment of red light areas where economic returns can be reinvested into commercial sex worker retraining programs.

Keywords: Commercial sex workers, red light area, debt bondage, modern slavery, reinvention, alternate livelihood, occupational upskilling

Introduction: a global perspective

COVID-19 has created extreme financial hardships for commercial sex workers across the world. Since people who seek their services are mostly workers with daily wages, the situation is worsening day by day. Apart from the financial issues, increased prevalence of underlying health conditions among sex workers might increase the risk of COVID-19 progressing to severe illness (Daly et al., 2016; UNAIDS, 2020a). Existing mental health problems are likely to be exacerbated by anxiety over income, food, and housing, alongside concerns about infection from continuing to work in the absence of social protection. Such a situation will be utilized by moneylenders to chain the workers to brothels for a long time. In the trafficking discourse and international law, debt-bonded sex workers have been defined as ‘victims of trafficking’. The hyper exploitative contractual arrangements faced by debt-bonded sex workers may be the most common form of contemporary forced labour practices in modern industry.

The story is the same in India with a million commercial sex workers across the nation in various red light areas. Such an explosive situation is the sole driving force behind the present study, whose objectives are:

to understand the demographic details of the major red light areas in India;

to analyse the on-the-ground financial situation and flow of funds in red light areas and their impact on commercial sex workers;

to describe the basic needs of commercial sex workers in red light areas and examine their vulnerability;

to analyse the long-term impact of debt on the commercial sex workers; and

to examine the need for economic empowerment of commercial sex workers.

Customers of commercial sex workers will be impacted by the economic slowdown due to COVID-19; their visits to red light areas will be cut down drastically (Tatke, 2020). For Sonagachi in Kolkata (the biggest red light area in India), the customer footfall of 20,000 daily has fallen to zero customers according to recent reports (Mukherjee, 2020). Many commercial sex workers are in debt regarding their rent and needing a place to stay (Tatke, 2020). Many have left for their villages due to lack of access to daily essentials (Kulkarni, 2020). To address the financial problems faced by the vulnerable sections of society, the Government of India declared a financial assistance package of INR500 to be transferred to citizens’ accounts; however, due to the majority of commercial sex workers living in red light areas having no bank accounts, AADHAAR card (a verifiable 12-digit identification number issued to all citizens of India by the Unique Identification Authority of India), or proof of residence, they are deprived of any such beneficiary scheme (Kajal, 2020).

Many HIV-positive commercial sex workers residing in Sonagachi are not able to buy medication due to lack of earnings (Kajal, 2020). As co-morbidity is higher in COVID-19 cases (Yang et al., 2020), the HIV-infected segment is a highly vulnerable at-risk group. Recently, after the lockdown declared in India on 23 March 2020, due to the COVID-19 epidemic, the Mumbai red light area witnessed 35 deaths within a few days during lockdown conditions. The deaths were suspected to be due to the non-availability of medication for prolonged illnesses such as tuberculosis, hepatitis, and HIV-AIDS. The red light area population does not have access to medical assistance, and any lack of money due to the debt trap adds a serious threat to their health and well-being. Fifty per cent of commercial sex workers in Maharastra, 40% in Tamil Nadu, and 20% in Karnataka are dependent on sex work and have no insurance as a backup (Chachra, 2019). They are financially insecure with no savings and may not be able to afford the cost of hospitalization if they contract COVID-19. The families of commercial sex workers have been turning to the helpline because of their plight. Many of them are saying that they have not had food for days in situations where police are forcing commercial sex workers and their families to stay inside (Chakraborty and Ramaprasad, 2020).

The study recommends that there is a dire need for governments to provide financial assistance to create vocational training opportunities leading to alternative employment for commercial sex workers as an exit strategy to save lives and prevent further financial exploitation of commercial sex workers due to the COVID-19 epidemic situation in India.

It may be helpful for readers to have the operational definitions for key terms used in this study. A debt trap is when a borrower is forced to re-borrow a loan adding to their debt amount because he or she is unable to pay back the principal on the loan (Gadre et al., 2019). Debt traps are primarily caused by high-interest rates and usually practiced by predatory lenders. Predatory lenders are moneylenders who make use of the plight of commercial sex workers by lending them money at a preposterous interest rate. The shadow pandemic is the term used to denote the Covid-19 pandemic and the debt-trap situation being seen as another pandemic for the commercial sex workers as the predatory lenders exploit their vulnerability.

Literature review

In their research on sexual exploitation of women in India, Joffres et al. (2008) raised concerns about the alarming increase in such crimes. The authors observed that trafficking for commercial sex work is a demand-based phenomenon. To meet the demands raised at the destination zones, traffickers target easily available vulnerable populations from source areas.

To keep the victims tied to their situations they are constantly kept in a state of financial dependence on exploiters. Nearly 80% of more than 800,000 women and children annually across the world end up in the forced sex trade and that makes India one of the severely affected Asian countries (nearly 90% of trafficking is such in India). The author is trying to provide some facts about the whole situation through showing the scenario where women and children are always strategically kept financially dependent by people who have a vested interest.

There is also an increase in criminal networks involved in the recruitment of young women and children, forcing them into the sex trade (Asian Development Bank, 2003; International Labour Organization, 2006). The most common form of commercial sexual exploitation involves the recruitment of young women by traffickers, who are then sold to a pimp/brothel-keeper, and coerced into prostitution. The recruitment strategies include a false promise of employment, offering financial help to families under a debt burden, abduction, and paying a dowry to young girls’ families by marrying them and eventually selling them to brokers who are connected to brothels (Sinha, 2006). Some of the biggest supply states are Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, and Uttar Pradesh. The biggest demand centre or destination areas for minor girls include West Bengal, Maharashtra, and Delhi, as they have the most prominent red light areas (Sinha, 2006) that are currently active.

According to the UJJAWALA scheme (a comprehensive scheme for prevention of trafficking and rescue, rehabilitation, and reintegration of victims of trafficking for commercial sexual exploitation) by the Ministry of Women and Child Development (2019), Government of India, commercial sexual exploitation is the process of exploiting individuals for economic gain, and it is a violation of basic human rights. The document highlighted provisions that aim to combat commercial exploitation covering Article 23 of the Constitution of India, the Indian Penal Code 1860, and the Immoral Trafficking Prevention Act 1956. Despite the legal provisions, the presence of modern slavery ecosystems continues to economically exploit individuals who are conditioned to internalize exploitative norms which are reflective of the poor reporting rate in repressive conditions.

The recent situation of the COVID-19 epidemic has cracked open the restrictive norms of non-reporting and brought the plight of sex workers’ economic exploitation to light. It became evident in a recent study conducted by the Asha Care Trust, which found that 99% of commercial sex workers in Budhwarpeth, Pune, are willing to opt for an alternative livelihood (Bose, 2020) (similar findings were reported in Portland – the US findings being due to the exclusion of women in commercial sex activity from the government’s relief schemes, hence taking away their choice to opt out of the flesh trade), and more than 85% of sex workers were in debt, of whom 98% had borrowed from brothel-keepers/owners/managers.

LaGrone (2020) stated that a lack of governmental support for securing minimum wages for women would push them into unfavourable circumstances. This practice is reported to be subject to further exploitation (Sharma, 2020). A similar situation was reported from Mumbai in Kamathipura and Falkland Road where 50% of respondents were forced to take loans from private moneylenders at exorbitant interest rates (Ganapatye, 2020a). To resolve this issue, Sangini Mahila Cooperative Bank was established in Mumbai for commercial sex workers by the US non-profit Population Service International, which collects savings and submits to the State Bank of India, which also led to the issuing of life insurance policies to the commercial sex workers.

Similar to LaGrone’s (2020) findings in the US, in India, Thomas (2020) reported the need for the Government of India to provide relief for the sex workers during lockdown. The debt bondage system works in normal conditions when the sex workers are always under financial pressure to pay back loans taken that have high interest rates. This system works only when the sex workers are engaging with a high number of customers on a daily basis to meet the repayment of debt bondage; however, this system failed during lockdown where the interest rates were raised by the moneylenders at a time when the earnings of the sex workers almost came down to zero because of a drastic reduction in customer footfall in the red light areas.

Chandra (2020) captured the plight of commercial sex workers in Pune and found that the majority of them were relying on NGOs to provide food as commercial sex workers do not have money to even purchase daily essentials. Due to the debt bondage on commercial sex workers, it may take them many months to resume their routine lifestyle. In desperation to repay loans and make ends meet, sex workers are reportedly risking their lives during the COVID-19 epidemic conditions by returning to the streets for engagement with customers (Chandra, 2020). Taking cognizance of the plight of commercial sex workers, the Supreme Court of India directed States to provide free rations to commercial sex workers and exercise powers to provide relief under the National Disaster Management Act (Thomas, 2020).

Methods used in data gathering

Data collection was conducted using a rapid assessment method. The interview schedule was designed to be administered in 15 minutes or less. A rapid assessment was selected to facilitate the outreach of the data collection team to the respondents during the times of lockdown. A rapid assessment method helps in reaching sample respondents who are less likely to respond to research questions (Wright et al., 2007). Prior to implementing rapid assessment, problems and challenges at the grass-root level were clearly laid out and conveyed to the research associates as part of the orientation for data collection.

The preparation of a structured interview schedule took a week. After the interview, the data collected had to go through validation with relevant literature and review by subject matter experts. One to two days were required for the orientation of research associates, and it took nearly two months (April and May 2020) for data collection. The data were collected in an intermittent manner depending upon the availability of respondents and referrals provided by contacting respondents by snowballing.

On average, it took 10 to 15 minutes for each interview. Research associates were trained to conduct the rapid assessment to understand the needs and financial situation of the respondents. Snowball and convenient methods help in maximizing respondents’ participation. The data collection team also involved representatives of the respondent’s population to get access to more places and helped in building rapport with new respondents.

To develop the interview tool and check its suitability for administering to the respondents, local field investigators were nominated as research associates to provide context in refining the tool. A total of five local research associates were tasked to conduct the rapid assessment in five different cities. All the research associates carried printed interview schedules along with a softcopy on their respective mobiles (in situations where avoiding contact with the respondents was mandatory due to locations falling in hot spots of COVID-19 transmission zones designated by the respective state government). The research associates were remunerated based on the number of rapid assessments conducted along with the allowances for their local travelling, photocopying of the interview schedules, and basic hygiene-related expenses that covered facemasks, hand gloves, and sanitizers.

The survey elements of the study comprise five key red light areas in three different cities in India. These are Sonagachi in Kolkata, GB Road in Delhi, Budhwarpeth in Pune, Kamathipura in Mumbai, and Ganga Jamuna in Nagpur. The data collection process included both primary and secondary sources. The primary sources of data collection included interviews (direct, telephonic, and focused group discussions) with the following respondents, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of respondent population by city.

| Sample number | Respondent type | Delhi | Mumbai | Nagpur | Pune | Kolkata | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Commercial sex worker | 20 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 120* |

| 2. | Informer/pimp/madam/brothel-keeper | 6 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 31 |

| 3. | Social worker | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 8 |

| 4. | Researcher | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 11 |

| 5. | Child welfare committee/shelter home superintendent | 0** | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0** | 4 |

| 6. | Total respondents | 30 | 40 | 35 | 33 | 36 | 174 |

* Number of direct interviews with commercial sex workers: 5 (Delhi), 8 (Mumbai), 10 (Nagpur), 15 (Pune), 12 (Kolkata); and with informers/pimps/madams/brothel-keepers: 6 (Delhi), 6 (Mumbai), 5 (Nagpur), 3 (Pune), 5 (Kolkata). The interviews were conducted by telephone using snowball sampling.

** CWC (Child Welfare Committee) members and SHS (Shelter Home Superintendent) were not available to participate in the present study due to their pre-engagement in COVID-19 relief operations in their respective jurisdiction.

In 2020 (April and May), to understand the on-the-ground financial situations of commercial sex workers in red light areas, a combination of a snowball and convenience sampling method was used through a rapid assessment tool for data collection from 120 commercial sex workers. To validate the findings derived through commercial sex workers on their economic conditions and gain an additional perspective on the economic situations in red light areas, 31 brothel-keepers/pimps were interviewed. In order to get a stakeholder’s perspective on the economic system in red light areas, eight members from non-profit organizations and four child welfare committees/shelter home superintendents were also interviewed. The data were collected through interviews (face-to-face and telephone) and focused group discussions (38 commercial sex workers were reached for participation in focus group discussions from Maharashtra State). The interview schedule used for conducting data collection is detailed in Appendix 1. For the focus group discussions, an interview schedule was used as a reference document to raise questions during the discussions. The face validity of the interview schedule was done based on the suggestions by subject matter experts and the input of women having more than 10 years of their lives spent as a commercial sex worker in red light areas. To improve the validity and reliability of the interview schedule, the questions were framed and the interaction was conducted in a structured manner during the interview process, while for focus group discussions the questions were open-ended and relevant questions were raised depending upon the flow of the progress of group discussion.

The secondary sources of data collection included an extensive review of papers published in journals, articles, and studies related to the economic impact/vulnerabilities of commercial sex workers in India and abroad (to understand the nuances and context). Since the sample size was not large, the research relied on the secondary source of data collection including referring to peer-reviewed literature, contacting subject matter experts (field investigators and academicians), and incorporating their inputs in the framing of a structured interview schedule and validation of information generated through primary data collection.

Ethical concerns about the interview and how they were addressed

In order to ensure voluntary participation, informed verbal consent from all the respondents was done prior to data collection. Research participants were given complete freedom of self-determination to participate in the study. All the respondents were informed about the risks involved and the probable impact of their involvement in the present study. Some of the respondents were incentivized for their participation to compensate for their loss of earnings due to participation in the present study. The rights of respondents and cultural values were taken into consideration while seeking informed consent from the respondents. Responses of all the respondents are properly protected for confidentiality and maintaining privacy. To safeguard any possibility of leakage of sensitive data, the data collection process avoided audio or video recordings. During telephone interviews, no personal details were recorded to ensure that the respondent could not be linked with the main data. Data collected from the field were coded and stored in organized file formats in password-protected secured systems accessible only by the research team. To avoid misleading findings, sample selection was done based on the approach proposed by subject matter experts. The data collection and analysis were conducted by individuals with proper orientation of ethics. During the COVID-19 lockdown situation, the well-being of the respondents and research associates was given prime importance by following safety and social distancing guidelines, like the use of personal protective equipment such as face masks and face shields, as issued by the Government of India.

Data analysis and findings with respect to demographics

The population for the survey elements the study includes red light areas in India. The five cities considered for the study of red light areas are Mumbai (Kamathipura and Grant Road), Nagpur (Ganga Jamuna), Delhi (GB Road), Kolkata (Sonagachi), and Pune (Budhwar Peth).

While each of these cities has one area each, the rest of the cities in India amount to a total of 110 red light areas. In 829 brothels in Kamathipura and Grant Road, there are about 5,500 commercial sex workers. This translates to 6.6 commercial and three non-commercial sex workers per brothel. In 300 brothels in Ganga Jamuna, there are about 1,400 commercial sex workers. This translates to 4.6 commercial and three non-commercial sex workers per brothel.

In 110 brothels in GB Road, there are about 3,500 commercial sex workers. This translates to 31.8 commercial and five non-commercial sex workers per brothel. In Kolkata’s Sonagachi, there are 1,200 brothels, in which there are 11,000 commercial sex workers. Thus, in Sonagachi, there are 9.2 commercial and 2.5 non-commercial sex workers per brothel.

Similarly, in Budhwar Peth in Pune, there are 450 brothels with 5,000 commercial sex workers. Thus, the ratio of commercial and non-commercial sex workers in Budhwar Peth is 11.1:3. The rest of the cities in the country have 72,111 brothels with 423,100 commercial sex workers. There are 5.9 commercial and three non-commercial sex workers per brothel in the rest of the cities in the country. Age-wise, the majority of respondents belonged to the 26 to 35 years category in New Delhi (60%), Kolkata (80%), Mumbai (52%), Pune (60%), and Nagpur (40%). The majority of the respondents had not received any formal education in New Delhi (60%), Kolkata (64%), Mumbai (48%), Pune (60%), or Nagpur (64%). The majority of the respondents were found to be residing in the red light areas for more than 15 years in New Delhi (60%), Kolkata (84%), Mumbai (60%), Pune (48%), and Nagpur (40%). In New Delhi, the majority of the respondents belonged to West Bengal (45%). In Kolkata, the majority of the respondents came from different parts of West Bengal (56%); similarly, in Mumbai, the majority of the respondents came from different parts of Maharashtra (40%). In Pune, the majority of the respondents belonged to West Bengal (40%). In Nagpur, 48% of the respondents belonged to Madhya Pradesh. The majority of respondents had more than four family members in New Delhi (50%), Kolkata (52%), and Mumbai (40%). In Pune, the majority of respondents had less than two family members (64%), whereas, in Nagpur, the majority of the respondents did not have any family members (40%). With 1,105 red light areas all over the country, there are about 75,000 brothels with 450,000 commercial sex workers. Overall, there are six commercial and 2.5 non-commercial sex workers per brothel. As indicated by UNAIDS (2020b), the number of commercial sex workers was reported to be around 650,000 in India in 2016. However, gauging from the yearly trend of a declining number of commercial sex workers, the number of commercial sex workers for this study is adjusted to an estimated 450,000 commercial sex workers.

The on-the-ground financial situation and flow of funds in red light areas and their impact on commercial sex workers

In all five of the red light areas located in five cities (Delhi, Kolkata, Pune, Nagpur, and Mumbai), the majority of respondents of older age groups were found to be long-term residents of red light areas. Young respondents earn more and are likely to stay for longer periods in red light areas. Presently, out of fear of transmission, the police prevent respondents from working. However, it was observed in Mumbai, Nagpur, and Delhi that the need for money was desperate to the extent of respondents secretly engaging during the lockdown as well (in small brothels) due to daily rent payment schemes (INR300 to INR600).

Generally, in small brothels, the respondents share 50% of their earnings with their brothel-keeper, whereas, in medium- and large-sized brothels, the respondents share 70% of their earnings. Loans offered by small brothels range from INR60,000 to INR100,000, and for big brothels, range from INR100,000 to INR200,000. The majority of respondents were not able to leave red light areas due to non-payment of recurring debts, and brothel-keepers were lending money to respondents thereby cumulating the loan amount. Larger loan amounts were selectively given to older and more trusted commercial sex workers who constituted about 20% of the commercial sex workers living in red light areas. The average interest rate for recurring debt on commercial sex workers in red light areas before and after lockdown has almost doubled from 7% to 12%. The main reason why respondents in red light areas took loans from moneylenders during lockdown was to meet daily expenses, to meet their family’s needs, for rent, for repayment of loans, etc. In the case of emergency situations, the loan amount can be large considering their earning and spending patterns.

How do the respondents spend their earnings?

Respondents primarily spent on their children’s education, on gold, and on repayment of their home loan. The respondents operating in the Parda System (within a small brothel, to make many commercial sex workers work in a confined place, the brothel-keeper would create a separate workplace for commercial sex workers by hanging curtains; in one common room, there will be multiple beds separated only by hanging curtains) in small brothels (in Mumbai, Kolkata, and Pune) shared 50% of their earnings with brothel-keepers and pimp(s). This share also covered loan interest, condoms, rent, and other services/facilitation charges.

We share 50% of our earnings with our brothel-keeper…that’s the way it is here. From the remaining, we send to our families in villages and the rest is used for our own expenses. Sometimes when our family needs urgent money, we have to take extra loans from the brothel-keeper. Nothing much remains for savings. (Ganga, 1 Mumbai)

In medium- and large-sized brothels, respondents shared 70% of their earnings with the brothel-keeper and the pimps: ‘In small brothels, pimp takes away 50% of our earnings per client and in big brothels, they take away around 70% of our earnings. This is a fixed system here…been here for many years’ (Vaigai, Mumbai).

Monthly earnings and expenditure at the time of starting as commercial sex workers

One of the respondents from Nagpur stated that minor victims were likely to earn INR70,000 per month, whereas in the case of majors – those aged above 18 – their average earnings would be around INR50,000 per month. Fifty per cent of earnings go to their brothel-keeper/manager and paying rent. On average, respondents were left with an average of INR12,000–15,000 per month for their expenses, for sending to their family, for addressing their daily needs, and for paying debt. On average, the respondents spent INR12,000–15,000 per month on payment of mess charges, beauticians, clothes, room rent (ranges from INR2,000 to INR6,000 per month), self-help group savings, payments to policemen, rented room maintenance, and cleaning. For those who were travelling, a significant amount of money was spent on travel, food, and rent payments. In situations where brothel-keepers pay for maintenance (electricity and water), and extortion money to criminal network members/police, the respondents have to pay for it as well.

Loans taken from pimps/managers before the coronavirus pandemic, amount, and interest rates

In 90% of small brothels in all red light areas, respondents would take loans ranging from INR60,000 to INR100,000 from managers on a quarterly basis, and would repay them by noting down the number of customers attended; the manager would calculate the customers attended by the respondents every month and reduce the repayment amount. This repayment cycle goes on until the respondents are in need of more money and have to take another loan from the manager. The manager/moneylender gets repayments from respondents significantly larger than the loan amount given to them due to high interest rates, undocumented contracts/oral agreements, and the respondent losing track of repayments (similar observations have been made by Ganapatye (2020b)). Hence, the respondents are further made to live in a state of recurring debt bondage. In big brothels where the respondents were charging comparatively more from clients, they took loans of more than INR1–200,000 and the repayment method remained the same, based on the number of customers the respondents engaged. A commercial sex worker cannot quit sex work and leave the brothels before clearing her loan amount: ‘We have to pay regular instalments to the brothel-keeper or moneylender. These things go in our minds even when we are performing sexual acts with our clients. I think of repayment of debt all the time’ (Narmada, Pune).

From the respondents of this study, more than 90% of respondents in three cities had taken loans from pimps/managers before the lockdown. There was a sense of anxiety and concern amongst the respondents about repayment of loans. Previous research studies have shown that commercial sex workers are subject to more violence than any other group of women due to economic dynamics in red light areas (Hunter, 1994).

Striking difference in loans before and during the lockdown situation

In Delhi and Mumbai, the interest rate on loans changed from 7% to 12% during the lockdown. The respondents stated that brothel-keepers themselves were taking loans from moneylenders and from other brothel-keepers. The respondents were taking loans at higher interest rates compared to brothel-keepers. Before lockdown, the average loan amount taken by respondents ranged from INR50,000 to INR100,000 per quarter, and post lockdown had increased to INR150,000–200,000 per quarter.

Loan taken from a pimp/manager during the lockdown

The majority of respondents were indebted to loans taken from moneylenders (pimp, brothel-keeper, managers). Only a few had taken loans from banks (the ones who had government IDs).

Many respondents had taken loans during lockdown and post lockdown, which made their life in the brothels impossible until the loan was settled. The brothel-keepers and managers were providing them with food and other basic needs, which further added to their debt:

Anything that we are not able to pay is adding up to the loan…the room rent, daily food, toiletries, essentials, medicines, masks, and gloves, every small thing is adding to the loan…the debt is increasing daily and with higher interest rates…feel worried. (Indus, Pune)

Amount of loan repayment before lockdown (daily/weekly/monthly/yearly)

The loan repayment totally depended on the earnings of the respondents; this varied from time to time depending on the customers. On average, 50% went to the brothel-keeper, 30% for family, and 20% on interest, food, rent, and medical needs. At the end of any month, despite the fact that the respondents’ earnings may have been, on average, INR50,000, they had nothing left to carry forward to the next month, and the majority of them had to start afresh.

On a monthly calculation of how many customers the respondents attended and how much they earned (considering the average figures calculated for the three cities), if the rate of the services offered by the respondent is INR1,200, she gets INR600 and INR600 will go to the room owner or brothel-keeper. If a respondent attends 10 customers daily and her rate is INR1,200, she will earn 600 × 10 = INR6,000. The brothel-keeper will further deduct the loan repayment amount from the earned INR6,000. Eventually, the commercial sex workers respondents would get a significantly lesser amount than INR6,000.

Mortgaged valuables to pimp/manager due to the COVID-19 situation

Many respondents had pledged their gold jewellery during the lockdown crisis. Brothel-keepers act as the middleman between the respondent and the gold loan moneylenders. Brothel-keepers take a share of the repayment of money paid to gold loan lenders, further exacerbating the losses and debt incurred by the respondents.

Basic needs of commercial sex workers in the red light area and examination of their vulnerability

Role of loan repayment in getting out of commercial sex work

In cases where commercial sex workers have a long-term positive relationship with their managers, they were allowed to move out of a red light area with a promise to repay the loan later. The majority of the respondents were of the opinion that the loan amount becomes a strong coercive binding force for commercial sex workers to stay in a red light area: ‘We cannot imagine running away without paying back the loan amount. The loan debt needs to be settled. There is no other option’ (Yamuna, Kolkata).

Post lockdown, the interest rates for loans have increased drastically (from 7% to 12%). Nearly 90% of the respondents from five cities were worried that they will not be able to repay their loans taken during lockdown, especially given the very high interest rates.

We got to take loans for medical illness and support our families…now that loans are so high, I am afraid that how am I ever going to repay it. (Saraswati, Nagpur)

Taking a loan even for toiletries and daily essentials, with a high-interest rate and on top of that is high rent to be paid monthly…it will be a difficult time ahead. (Gomti, Delhi)

Ninety-five per cent of respondents from the five cities felt that they were not able to leave the red light area without repayment of the loan amount.

Prime reason why borrowing has become common practice

We are so desperate to earn money and pay our dues…some of us are engaging with customers in this coronavirus time also…what to do, we have to pay rent…we will die anyway if we don’t earn. (Kauvery, Mumbai)

A significant number of the respondents were pressured by their landlords to pay rent for their houses, and had to mortgage or sell their gold to get some money to pay the rent. Many of the commercial sex workers had family members who depended on them back in their hometowns, and they were forced to take loans to send money back home during the lockdown. Multiple women also said that their children are their reason for survival, and they want their children to study and have opportunities to grow, but now they did not even have enough money to pay the school fees, which forced them to withdraw their children’s names from the schools. Some respondents had to take loans to pay the fees of their children. Some respondents had ambitiously admitted their children to private schools for better life opportunities and bearing an additional burden of paying exorbitant school fees. In Pune, all the women had taken loans, and these loans ranged from INR10,000 to INR100,000. The reasons for these loans were rent, electricity bills, children’s school fees, and medical expenses for themselves and their families. One of the respondents needed INR800 every month for her medical expenses. There are certain fixed amounts to be paid by the respondents on a monthly basis, which adds to the financial distress of paying on a regular basis. Most of the respondents expressed fear over the consequences due to their uncertainty of not being able to pay their monthly expenses.

Analysing the long-term devastating impact of the debt

To understand the long term financial impact of the debt on the commercial sex workers, data were collected based on the average number of engagements per commercial sex worker and potential client meetings by a pimp taking into account the current debt taken by commercial sex workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, pre-COVID-19 baseline loan amounts, the rate of interest on the debt taken by commercial sex workers, the monthly expenditure including payout to brothel owners, and the monthly transfer of funds to family back home.

Based on the interviews with respondents residing in red light areas in the current economic conditions, the following observations were recorded:

Once the lockdown is released and red light areas are reopened, there will be at least three months of slowdown in commercial sex activities post the reopening of red light areas.

The number of people visiting the brothels after the lockdown will be half the usual or even less as compared to the pre-COVID situation.

As a consequence of a drastic reduction in the number of customers visiting red light areas, the corresponding earnings of the commercial sex workers will be reduced to half or even less.

The expenses breakdown of the monthly earnings of the respondents will remain the same as during the COVID-19 situation (50% to brothel-keepers, 30% to families, and 20% for self/repayment of debt).

Debt-trap analysis

The above data were central in the process of analysis of the economic conditions of respondents in the red light area with reference to the impact caused by COVID-19. The scenario building enabled the researchers to look at three options:

in the context of the existing scenario when lockdown will be released by 31 May 2020;

the possibility of extension of the lockdown by another month; and

if the lockdown in the red light area is extended up to 31 December 2020.

The aim of these three scenarios is to understand the current situation and forecast possible consequences of the COVID-19 epidemic on the economy of respondents living in red light areas across the country. The three scenarios taken for the study are:

Scenario 1: if the lockdown is released by 31 May 2020.

Scenario 2: if the lockdown is extended up to three months until 30 June 2020.

Scenario 3: if there is no work up to nine months until 31 December 2020.

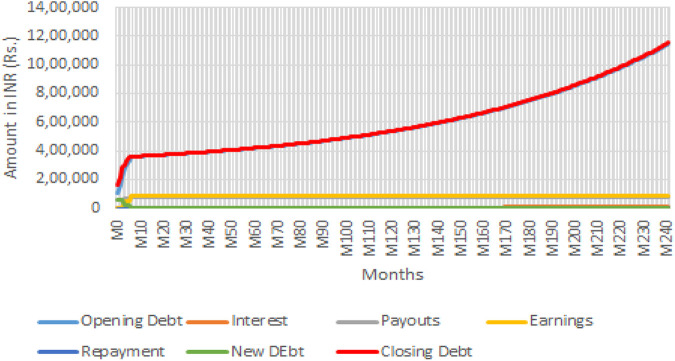

In Table 2, it is shown that the average debt on respondents prior to the lockdown situation was INR109,142 and this debt would take 4.3 years to repay. However, in scenarios 1, 2, and 3 with no earnings and debt with their interest rate, by the time lockdown opens, the average debt on respondents will be INR221,886 (by the end of two months of lockdown), INR279,105 (by the end of three months of lockdown), or INR695,982 (by the end of nine months of no work). The graph in Figure 1 shows the forecast of the debt trap for respondents in different situations in times ahead, starting with the pre-COVID situation.

Table 2.

Economic analysis of commercial sex workers’ financial situation in three different scenarios with reference to the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Particulars |

Scenario 1 If the lockdown is released by 31 May 2020 (2 months) |

Scenario 2 If the lockdown is extended up to 30 June 2020 (3 months) |

Scenario 3 If there is no work up to 31 Dec 2020 (9 months) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lockdown period (months) | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| 2 | Slowdown period (months) | 3 (June–Aug 2020) | 3 (July–Sep 2020) | 3 (Jan–Mar 2021) |

| 3 | Average debt per commercial sex worker at the beginning of lockdown | INR109,142 | INR109,142 | INR109,142 |

| 4 | Monthly payout (expenditure + pay to brothel owner) – 50% to brothel-keepers, 30% to family, and 20% for self- expenditure and loan payouts | INR55,000 | INR55,000 | INR55,000 |

| 5 | Daily earnings | INR2,750 | INR2,750 | INR2,750 |

| 6 | Monthly earnings | INR82,500 | INR82,500 | INR82,500 |

| 7 | Payout to family (% of monthly earnings) | 30% | 30% | 30% |

| 8 | Rate of interest | 12% | 12% | 12% |

| 9 | Debt at the end of lockdown | INR221,886 | INR279,105 | INR695,982 |

| 10 | Repayment period prior to lockdown (assuming no pandemic, regular earning, and no accrued loan) | 4.3 years | 4.3 years | 4.3 years |

| 11 | Repayment period post lockdown | Not repayable (forced into debt trap) | Not repayable (forced into debt trap) | Not repayable (forced into debt trap) |

Figure 1.

Scenario: debt repayment schedule without the impact of lockdown.

Scenario: debt repayment without the impact of COVID-19, regular trade ongoing

As shown in Figure 1, in the pre-COVID-19 situation, the x-axis represents months, and the y-axis represents the amount in INR. Debt repayment is dependent upon consistent payout and earning amounts with no new additional debt taken. In these conditions, the debt repayment would have closed the debt cycle for respondents in four years and two months.

Scenario 1: debt repayment impact – two months of lockdown (until May 2020) and three months of slowed-down business

The debt repayment post two months lockdown followed by three months slowdown in economic activity in the red light area will have a drastic impact on the economic aspect of respondents’ lives (Figure 2). The opening debt begins at INR109142 (yellow line) and the closing debt (red line) starts mounting from there onwards indefinitely due to increasing interest rates, a large amount of increasing monthly payouts, reduction in earnings during initial months after the lockdown, and new debt taken during initial months after the lockdown.

Figure 2.

Debt repayment schedule post lockdown (two months lockdown + three months slowdown).

The average debt of respondents would increase by up to 50% in month 1, by 33% in month 2, and will increase to 10% per month during the months of slowdown.

Scenario 2: debt repayment impact – three months of lockdown (until June 2020) and three months of slowing-down business

The debt repayment post three months lockdown followed by three months slowdown in economic activity in red light areas will have a drastic impact on the economic aspect of respondents’ lives (Figure 3). The opening debt begins at INR109,142 (blue line) and the closing debt (red line) starts mounting from there onwards indefinitely due to increasing interest rates, a large amount of increasing monthly payouts, reduction in earnings during the initial months after the lockdown, and new debt taken during the initial five months after the lockdown.

Figure 3.

Debt repayment schedule post lockdown (three months lockdown + three months slowdown).

The average debt of respondents would increase by up to 50% in month 1, 33% in month 2, and 25% in month 3, and will increase to 10% per month during the months of slowdown.

Scenario 3: debt repayment impact – nine months of no work (until December 2020) and three months of slowing-down business

The average closing debt on respondents by the end of nine months of no work would be INR695,982 (Figure 4). After the reopening of red light areas, the three months of slowdown would add further debt onto respondents and leave them with an average closing debt of INR788,278. With increased interest rates, a slow rate of earning generation, and a high amount of payouts to moneylenders, the respondents will be trapped in debt bondage, which would be unpayable in their lifetime. In such situations, the debt is likely to be passed on to their next-generation kin who may have to engage in sex work early in their life to support debt repayment (International Justice Mission, 2017).

Figure 4.

Debt repayment schedule post lockdown (nine months no work+ three months slowdown).

The debt trap and its relation with modern-day slavery

Indicators of modern slavery are signs of physical or psychological abuse, fear of authorities, no ID documents, poor living conditions and working long hours for little or no pay (Grierson, 2017). The UK Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, Kevin Hyland, described modern slavery as where somebody takes control of a person and turns them into a commodity (Rose and Cumming, 2017). One of the primary factors behind modern slavery is personal or commercial gain (Kelly, 2017) by exploiting others. The loss of control caused by debt bondage is a coercive force that entraps commercial sex workers in the red light area, eliminating their autonomy through an economic system of debt bondage to the brothel-keeper and other red-light-area-based workers. The shift in time frame required to repay loans from a finite period of time to a state of indefinite debt bondage puts these women into a state of inescapable bonded labour.

According to the Bonded Labour (Abolition) Act of the Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India (1976), a bonded labourer is defined as a ‘debtor who enters into an agreement with the creditor that she/he would render service to for a specified or unspecified period, either without wages or for nominal wages, in consideration of loan’. The law has a loophole, and it is being used to keep commercial sex workers in a kind of modern day slavery in India.

Why economic empowerment is essential for commercial sex workers

Recent studies have shown that commercial sex workers are likely to accelerate the transmission of COVID-19 if they continue to work in red light areas in India (Koshy, 2020). In Germany, lawmakers called for a permanent closure of brothels, stating that commercial sex workers are potential ‘super spreaders’ as the sexual activities are an obvious violation of social distancing measures (Douglas, 2020). The German lawmakers strongly suggested to the German government for a permanent closure of red light areas and to provide apprenticeships, training, or job security to commercial sex workers. It is evident that reopened brothels will severely exploit commercial sex workers: ‘I want to have a different life, but since I have so much loan to repay, I can’t leave. If I get an alternative solution, I will leave sex trade for this sustainable work’ (Koshi, Pune).

The economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on commercial sex workers in India have alarming ramifications. The exploitative economic conditions in red light areas will cause a severe debt crisis. The findings of the study clearly show that the lockdown situation has raised serious concerns about the economic independence, survival, health risks, and negative economic effects of commercial sex workers during and after the lockdown.

The vulnerability of commercial sex workers is aggressively exploited by criminals by burdening commercial sex workers under additional debt with high interest rates. The commercial sex workers are left with no choice but to enter into a debt trap for their life, otherwise they and their families may starve due to the lockdown situation. The contemporary situation for commercial sex workers in India represents the single largest movement of human beings into modern slavery in the history of mankind in a span of two months.

The conducive factors for driving modern slavery are the absence of effective implementation of the law and normalization of continued exploitation of commercial sex workers in red light areas through an inability to leave a controller and occupation due to fear and coercion and inability to ever repay the controller creating an inescapable trap with no endpoint. Through the current analysis of the economic indebtedness, it is evident that the contemporary situation in red light areas of India is a modern slavery crisis.

The data clearly reveal through the financial analysis that there is a crisis, and there is an immediate need to assess the alternatives to sex work within the red light area population so that with minimum to no health consequences, commercial sex workers may be provided relief and alternate skills/options for establishing earnings and independence in their lives.

Farley et al. (2004) stated that the majority of women in sex work need an ‘exit from prostitution, housing, medical care and sustainable employment’. As a solution, the study strongly recommends empowering commercial sex workers with alternative occupational skills through training programs and sustaining alternative means of livelihood in the larger public interest, as was mentioned by the Supreme Court of India (Deccan Herald, 2011). The Supreme Court Justices Markandeya Katju and Gyan Sudha Mishra (19 July 2011) stated that ‘a sex worker can live a dignified life only if she earns through technical skills rather than selling her body’.

The Central Sector Scheme of the Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India (2016–2017) has provisions for implementing employable skill development training as a compulsory element of a rehabilitation package for commercial sex workers. Government proactive action towards the recommendations of the present study would be highly important for mitigation of the disastrous health consequences for citizens and the successful protection of commercial sex workers with alternative livelihoods.

Limitations of the assessment

There are some limitations to the current analysis. They include that the rapid assessment method had restricted scope so that the respondents were able to respond to a limited number of questions.

The data collection process was initiated post lockdown scenario and the respondents shared the details of finance-related information about pre-lockdown activities retrospectively.

It was observed that a few respondents were struggling to provide exact estimates of economic details, maybe due to their lack of overall understanding of financial aspects related to them, or they were finding it difficult to remember and share estimates due to possible variance in monthly earnings, payouts, and savings.

Another limitation was to operate during lockdown situations, which restricted the process of data collection. As there was an evident reduction in the customer footfall in red light areas, commercial sex workers and pimps were found to be more inclined to engage with customers. However, the data collection method – a rapid assessment survey – was appropriate, and the team also moderated the interviews with the respondents to capture key aspects relating to economic activities.

The data collection team faced difficulties in gathering sensitive data while adhering to social distancing norms in densely populated locations. In such scenarios, nearly 25% of the interviews were postponed and scheduled during convenient (for the respondents) and suitable (for the research associate) conditions.

Another limitation of the study is a poor response rate due to associating factors of perception of fear of victimization by brothel-keepers, pimps, or other commercial sex workers. Only 30% of the total respondents accepted to be participants in the present study.

Tackling this challenge is the dire need of the hour

In light of the above analysis and discussion, the various aspects that can be covered to address this crisis can be as follows. First, there is a need to raise the issue to ensure a high level of awareness amongst sex workers and provide a list of schemes for their utilization. To establish a task force at Centre, State, District, and at a local level for the implementation of a reinvention model that can mitigate risk and reduce the health crisis.

Existing laws against predatory moneylenders to curb money lending practices at exorbitant rates have to be strengthened and it must be ensured that they (for charging interest rates exceeding 2% or more above the interest rates fixed by commercial banks on loans) are in alignment with Tamil Nadu’s Prohibition of Charging Exorbitant Interest Act 2003 and the Kerala Prohibition of Charging Exorbitant Interest Act 2012 (Gopakumar, 2016).

To break the chain of debt, there need to be alternative livelihood plans that offer identity (government-authorized personal ID proofs) and financial security. One might be to replicate the Sangini cooperative banking service model run by Population Services International in Mumbai’s Kamathipura, which collected money from sex workers and pooled it into a single interest-bearing account at the State Bank of India. The services are also provided to sex workers without identity cards and the operations at Sanini are based on the identification of sex workers using a digital webcam photo database (The Economic Times, 2008). Opening bank accounts, taking loans for starting new ventures, and starting savings for the future are some of the perks.

Another is a fully functioning rehabilitation centre that has dedicated units for preparation, awareness, knowledge, channelling, monitoring, and evaluation programs to prevent commercial sex workers from going back to prostitution.

The government should design local intervention programs through social service units to break the supply chain of victims from source areas.

Former sex workers may be given an important role as change-makers to share their views in designing effective intervention programs and mentoring newly enrolled commercial sex workers at different stages by sharing their own feelings and thoughts.

A mass-media drive needs to be initiated to make commercial sex workers feel heard and also to change the mindset of society to become more accepting of commercial sex workers’ reintegration into that society.

For the successful extraction of commercial sex workers from exploitative loan practices in red light areas, the Government of India should implement the revised scheme and guidelines of the Central Sector Scheme for Rehabilitation of Bonded Labourer, Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India (2016) that provides rehabilitation assistance up to INR300,000 granted by the District Magistrate for commercial sex workers living in sexually exploitative conditions in brothels.

In addition, the commercial sex workers are entitled to the Centre or State government’s assistance for land allotment, development, provision for low-cost dwelling units, animal husbandry, dairy, poultry, wage employment, supply of essential commodities, and education for children.

Commercial sex workers need immediate earnings to sustain themselves; they will also require intensive skilling, counselling, and soft skills/technical skills and certification to be able to get sustainable jobs. Therefore, there is a need for a blended form of training that provides a stipend and skills training that leads to jobs or entrepreneurship.

Conclusion

The findings produced by this research paper are solid and ample evidence to cement the claim that this debt trap is an organized activity to suck the blood and life out of commercial sex workers. The current COVID-19 situation has devastated commercial sex workers. However, their dilemma has been strategically used by moneylenders as insurance for a heightened money flow channel in the days to come.

To save commercial sex workers from this modern-day slavery, there are suggestions listed in this research paper that have a high chance to keep them away from the trap forever. The study also gives suggestions about the action to be initiated by the government and the non-governmental agencies should include, among others, the proactive action of capacity building for alternate employment. The current health findings prove that red light areas should remain closed indefinitely (Kumarvikram, 2020). If red light areas are reopened, despite the major negative health consequences, it will not improve the economic conditions for commercial sex workers as the projected reduction in customer visits over the next months will move commercial sex workers further into a debt trap given that their earnings will be highly reduced.

A robust model of tangible alternative solutions for occupational upskilling of commercial sex workers in red light areas is also included in the paper. The returns to the economy generated by commercial sex workers’ engagement in alternative livelihood can be reinvested into their retraining programs and would save many lives and prevent a mass movement of Indians into slavery.

Appendix 1

Interview schedule

| Particulars | Focus area | Questions |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Introduction to study and informed consent | Q 1.1. What do you understand about the objectives of this study? Q 1.2. What could be possible risks of participating in this study? Q 1.3. What could be possible benefits of participating in this study? |

| 2. | Demographic details | Q 2.1. What is your age? Q 2.2. Which is your place of origin? Q 2.3. What is your educational qualification? Q 2.4. For how long are you staying in the red light area? Q 2.5. How many family members are you supporting? |

| 3. | Economic systems in red light area | Q 3.1. What was your earning p.m. when you were newly recruited to work in red light areas? Q 3.2. What is your current earnings p.m.? Q 3.3. What is your current expenditure p.m.? Q 3.4. What is your current savings p.m.? Q 3.5. What is the share of your monthly earnings with others? Q 3.6. What is the change in the number of customers due to lockdown? |

| 4. | Financial exploitation | Q 4.1. What was the loan taken by you prior to lockdown? Q 4.2. What is the loan taken by you during lockdown? Q 4.3. What is the current total loan amount to be repaid by you? Q 4.3. What is the duration for which you used to take out a loan prior to lockdown? Q 4.4. What is the duration for which you took out a loan during lockdown? Q 4.5. What was the interest rate on the loan taken by you prior to lockdown? Q 4.6. What is the interest rate on the loan taken by you during lockdown? Q 4.7. What is the reason behind taking out a loan? Q 4.8. How much time did it take to repay the loan before lockdown? Q 4.9. How much is your monthly payout to repay the loan? |

Note

The names of the respondents are changed in this and the following quotations.

References

- Asian Development Bank (2003) Combating trafficking of women and children in south Asia – Regional synthesis paper for Bangladesh, India, and Nepal. Available at: http://www.adb.org/Documents/Books/Combating_Trafficking/Regional_Synthesis_Paper.pdf (accessed 21 June 2020).

- Bose M. (2020) Maharashtra: 99% of commercial sex workers in Pune look for alternative livelihood. Deccan Herald, 15 September. Available at: https://www.deccanherald.com/national/west/maharashtra-99-of-commercial-sex-workers-in-pune-look-for-alternative-livelihood-887888.html(accessed 23 September 2020).

- Chachra M. (2019) HIV rates are down. There’s little else going for India’s sex workers. IndiaSpends, 9 August. Available at: https://www.indiaspend.com/hiv-rates-are-down-theres-little-else-going-for-indias-sex-workers/(accessed 14 May 2020).

- Chakraborty R, Ramaprasad H. (2020) ‘They are starving’: Women in India’s sex industry struggle for survival. The Guardian, 29 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/apr/29/they-are-starving-women-in-indias-sex-industry-struggle-for-survival(accessed 15 May 2020).

- Chandra J. (2020) Virus effect: Sex workers worry about the months to come. The Hindu, 20 April. Available at: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/virus-effect-sex-workers-worry-about-the-months-to-come/article31384288.ece(accessed 18 September 2020).

- Daly R, Khatib N, Larkins A, et al. (2016) Testing for latent tuberculosis infection using interferon gamma release assays in commercial sex workers at an outreach clinic in Birmingham. International Journal of Sexually Transmitted Diseases 27: 676–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deccan Herald (2011) Supreme Court sets panel for sex workers rehabilitation. Deccan Herald, 19 July. Available at: https://www.deccanherald.com/national/sc-sets-up-panel-for-sex-workers-rehabilitation-171482.html(accessed 22 October 2020).

- Douglas E. (2020) German lawmakers call for buying sex to be made permanently illegal. DW.com, 20 May. Available at: https://www.dw.com/en/german-lawmakers-call-for-buying-sex-to-be-made-permanently-illegal/a-53504221(accessed 9 June 2020).

- Farley M, Cotton A, Lynne J, et al. (2004) Prostitution and trafficking in nine countries: An update on violence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Trauma Practice 2(3–4): 33–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gadre G, Bhargava A, Mehta L. (2019) How to get out of a debt trap? The Economic Times, 11 November. Available at: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/wealth/borrow/how-to-get-out-of-a-debt-trap/articleshow/71981849.cms?from=mdr(accessed 24 October 2020).

- Ganapatye S. (2020. a) Nearly 50% sex workers saddled with debt. Mumbai Mirror, India Times, 22 May. Available at: https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/mumbai/other/nearly-50-sex-workers-saddled-with-debt/articleshow/75768696.cms(accessed 22 May 2020).

- Ganapatye S. (2020. b) Sex workers break free from their trade with aid; start selling clothes, fish and tea. Mumbai Mirror, India Times, 17 September. Available at: https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/mumbai/other/sex-workers-break-free-from-their-trade-with-aid/articleshow/78157803.cms(accessed 1 October 2020).

- Gopakumar KC. (2016) Provision in law against moneylenders rarely enforced. The Hindu, 23 May. Available at: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/provision-in-law-against-moneylenders-rarely-enforced/article6024791.ece(accessed 10 October 2020).

- Grierson J. (2017) Tens of thousands of modern slavery victims in UK, NCA says. The Guardian, 10 August. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/aug/10/modern-slavery-uk-nca-human-trafficking-prostitution(accessed 22 May 2020).

- Hunter SK. (1994) Prostitution is cruelty and abuse to women and children. Michigan Journal of Gender and Law 1: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- International Justice Mission (2017) Commercial sexual exploitation of children in Mumbai. Findings in public establishments, private networks and survivor’s perspective. Available at: https://www.ijmindia.org/files/library/CSES%20Study%20Report%20Rev%20%28Final%20Prevalence%20Study%29.pdf(accessed 28 May 2020).

- International Labour Organization (2006) Demand side of human trafficking in Asia: Empirical findings. Regional Project on Combating Child Trafficking for Labour and Sexual Exploitation (TICSA-II). Bangkok, Thailand: International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Joffres C, Mills E, Joffres M, et al. (2008) Sexual slavery without borders: Trafficking for commercial sexual exploitation in India. International Journal for Equity in Health 7(1): 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajal K. (2020) Sex workers, high-risk for COVID-19, seek government help. IndiaSpend Report, 14 April. Available at: https://www.indiaspend.com/sex-workers-high-risk-for-covid-19-seek-government-help/(accessed 14 May 2020).

- Kelly A. (2017) ‘Human life is more expendable’: Why slavery has never made more money. The Guardian, 31 July. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/jul/31/human-life-is-more-expendable-why-slavery-has-never-made-more-money(accessed 26 May 2020).

- Koshy J. (2020) Commercial sex workers could spike COVID-19 cases in India. The Hindu, 17 May. Available at: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/coronavirus-commercial-sex-work-could-spike-covid-19-cases-in-india-says-study/article31608856.ece(accessed 9 June 2020).

- Kulkarni S. (2020) Sex workers in Budhwar Peth apply to return to native place, say they want to go home. The Indian Express, 7 May. Available at: https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/pune/sex-workers-in-budhwar-peth-apply-to-return-to-native-place-say-they-want-to-go-home-6399121/(accessed 17 May 2020).

- Kumarvikram (2020) Keep red light areas closed post-coronavirus lockdown: Yale School of Medicine. The New Indian Express, 17 May. Available at: https://www.newindianexpress.com/thesundaystandard/2020/may/17/keep-redlight-areas-closed-post--coronavirus-lockdown-yale-school-of-medicine-2144242.html(accessed 17 May 2020).

- LaGrone L. (2020) Excluding those in sex industry from Covid-19 relief is a mistake. Washington Post, 23 April. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/04/23/excluding-those-sex-industry-covid-19-relief-is-mistake/(accessed 1 October 2020).

- Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India (1976) The Bonded Labour (Abolition) Act. Available at: https://labour.gov.in/sites/default/files/TheBondedLabourSystem(Abolition)Act1976.pdf(accessed 4 June 2020).

- Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India (2016) Central Sector Scheme for Rehabilitation of Bonded Labourer F. No. S-11012/01/2015-BL. Available at: https://labour.gov.in/sites/default/files/OM_CSS_Rehab_BL_2016_1.pdf(accessed 5 June 2020).

- Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India (2016–2020) Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana Guidelines. Available at: https://www.msde.gov.in/assets/images/pmkvy/PMKVY%20Guidelines%20(2016-2020).pdf(accessed 9 June 2020).

- Ministry of Women and Child Development (2019) A comprehensive scheme for prevention of trafficking and rescue, rehabilitation and reintegration of victims of trafficking for commercial sexual exploitation. Available at: https://wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/Draft%20proposed%20guidelines%20of%20Ujjawala%20Scheme.pdf(accessed 20 August 2020).

- Mukherjee J. (2020) ‘Covid-19 is worse than HIV’: Left penniless during lockdown, Kolkata’s sex workers find help. News18, 13 April. Available at: https://www.news18.com/news/buzz/covid-19-is-worse-than-hiv-left-penniless-during-lockdown-kolkatas-sex-workers-find-help-2574175.html(accessed 15 May 2020).

- Rose E, Cumming E. (2017) Slaves on our streets: Abigail’s story of entrapment and prostitution provides a glimpse of a brutal reality. The Independent, 12 September. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/modern-slavery-campaign-abigiails-story-case-study-prostitution-sex-slavery-human-trafficking-london-a7942326.html(accessed 23 May 2020).

- Sharma S. (2020) COVID-19 impact: Sex workers in Mumbai, Pune look for alternative livelihood. CNBC TV-19, September 18. Available at: https://www.cnbctv18.com/india/covid-19-impact-sex-workers-in-mumbai-pune-look-for-alternative-livelihood-6949871.htm(accessed 1 October 2020).

- Sinha I. (2006) Trafficking and children at risk. Sanlaap. http://www.ashanet.org/focusgroups/sanctuary/articles/sanlaap_trafficking.doc (accessed 15 April 2020).

- Tatke S. (2020) India’s sex workers fight for survival amid coronavirus lockdown. Aljazeera News. available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/india-sex-workers-fight-survival-coronavirus-lockdown-200412073813464.html(accessed 15 May 2020).

- The Economic Times (2008) Indian bank helps sex workers save. The Economic Times, 16 June. Available at: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/banking/finance/banking/indian-bank-helps-sex-workers-save/articleshow/3132957.cms?from=mdr(accessed 25 July 2020).

- Thomas A. (2020) Provide food to sex workers during lockdown: SC tells Centre, states. The Hindustan Times, 22 September. Available at: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/provide-food-to-sex-workers-during-lockdown-sc-tells-centre-states/story-JlAtJ064xSaw9QB4WRzrPK.html(accessed 10 October 2020).

- UNAIDS (2020. a) Population size estimates of sex workers in India. Available at: http://kpatlas.unaids.org/dashboard(accessed 14 May 2020).

- UNAIDS (2020. b) COVID-19 responses must uphold and protect the human rights of sex workers. Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2020/april/20200424_sex-work (accessed 22 May 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Wright MT, Block M, von Unger H, et al. (2007) Participatory quality development. Available at: https://www.iqhiv.org/fileadmin/stuff/pdf/Tool-PQD-EN.pdf(accessed 22 October 2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, et al. (2020) Prevalence of comorbidities in the novel Wuhan coronavirus (COVID-19) infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]