Abstract

Using the county-level data of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in the United States, we test the relationship between communities’ social capital and philanthropic resource mobilization during a pandemic and how this relationship is moderated by the racial diversity and the severity of the pandemic in the community. The analysis suggests that the collective monetary contributions to frontline nonprofits responding to pandemics are closely related to the level of social capital in the community. The results also reveal that the positive relationship between social capital and resource mobilization is reinforced in racially diverse communities and when communities are affected by pandemics more severely. Our findings suggest that building inclusive communities by embracing diverse racial groups and individuals will contribute to communities’ resilience to pandemics and other disasters.

Keywords: pandemics, local philanthropy, resource mobilization, social capital, racial diversity

Introduction

A disaster is a traumatic event that creates social disruption and depletes collective resources of a community (Aldrich and Meyer 2015). When a disaster strikes, it is critical for a community to have the capacity to mitigate the damages caused by it and return to normalcy by mobilizing available resources. This collective capacity of mobilizing resources among community members and coordinating cooperative behaviors across sectors contributes to risk reduction through the process of disaster preparedness, response, and recovery; therefore, these factors/qualities determine a community’s disaster resilience (Cutter, Ash, and Emrich 2014). A community’s collective capacity is especially important when government assistance and relief activities are inconsistent or unreliable due to procedural and manufacturing delays (Sadiq and Kessa 2020).

In the United States, nonprofit organizations play a primary role in responding to crises on the frontlines and collaborating with governments and other private sector organizations (Brudney and Gazley 2009; Domingue and Emrich 2019). In response to pandemics and their aftermath, social actors must collectively mobilize available resources for local nonprofit organizations by working on the frontlines and providing indispensable services to affected and vulnerable populations (Domingue and Emrich 2019). The demand for health and human services increases during a pandemic, whereas the resources for the organizations that provide such services decrease. Accordingly, communities’ capacity for mobilizing philanthropic resources for frontline service organizations becomes even more important (Plough et al. 2013). Recently, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, community foundations and other charities started fundraising programs to support health care and human service organizations who fought the pandemic on the frontline (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2021). For example, local United Way affiliates around the world have raised COVID-19 response funds to be allocated to small, local nonprofits that were providing essential services to the affected populations (Paarlberg et al. 2020).

Disaster management experts recommend that disaster responses be tailored to the local context (Paarlberg et al. 2020; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe 2020). Communities differ significantly in their capacities to mobilize necessary resources in response to crises, and such capacities are shaped by local context, including communities’ social and economic infrastructure (Amenta and Zylan 1991). Among essential community characteristics, community social capital, which reflects the set of collective values, norms, and beliefs, can be transferred to resources and bring tangible benefits to community members (Borgonovi, Andrieu, and Subramanian 2021; Glanville, Paxton, and Wang 2016). Social capital leads to civic engagement embedded in social interaction, ties, and structures, which motivates people to mobilize resources through protective or adaptive action in response to external disturbances (Bixler et al. 2021; Lin, Fu, and Hsung 2001). The collective ability for resource mobilization, in turn, determines the success of the post-disaster recovery (Aldrich 2012). Research indeed finds that social capital contributes to decreasing mortality rates and enhancing community resilience in the case of external shocks such as contagious diseases and natural disasters (Bhowmik et al. 2021).

Although existing research has examined the impacts of social capital on public health outcomes, little is known about how social capital influences community resource mobilization during a pandemic. 1 This study examines how social capital contributes to a community’s resource mobilization during a pandemic, using the case of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. The H1N1 virus (i.e., a novel influenza A type) emerged in the spring of 2009 and quickly spread across the United States, causing more than 12,000 deaths nationally (CDC 2010). This study focuses on the local context of U.S. counties and tests how social capital relates to communities’ collective capacity to mobilize resources, such as medical assistance and humanitarian aids, for the frontline nonprofits responding to the pandemic-caused problems.

In addition to the social capital-resource mobilization relationship, this study examines the role of racial diversity in community resource mobilization during the pandemic. Putnam (2007) suggested that racial diversity in a community is negatively correlated with its social cohesion, solidarity, and civic-mindedness. Research also finds that antagonism and violence against outgroup members, including immigrants and racial and ethnic minorities, arise during and in the aftermath of a pandemic (Dutta and Rao 2015). However, other scholars suggest that diversity fosters social cohesion and collective action rather than precluding them (e.g., Bloemraad 2006; Gesthuizen, van der Meer, and Scheepers 2009). This study examines how racial diversity moderates the relationship between communities’ social capital and resource mobilization. Figure 1 offers a summary of our research model.

Figure 1.

Research model.

Literature Review

Resource Mobilization as a Response to External Threats: Contagious Diseases

The literature on contagious disease outbreaks, epidemics, and pandemics has adopted the disaster and disaster reduction frameworks (Rao and Greve 2018; Toyoda et al. 2021). Both natural disasters and contagious disease outbreaks are catastrophic events that cause economic, emotional, and social disruptions in communities and require prompt and collective action (Peek et al. 2020). In responding to both natural disasters and pandemics, the level of community cohesion and trust plays a crucial role since it determines information sharing and communication among community members (Scanlon and McMahon 2011).

However, unlike natural disasters, the impacts of epidemics and pandemics are not limited to economic and social infrastructure, as they also evoke xenophobia that is a cognitive threat to a community (Crandall and Schaller 2005). Scholars explain that contagion anxiety is socially driven, generating fear and eroding social cohesion among an array of diverse social actors (Dutta and Rao 2015; Picou, Marshall, and Gill 2004). For example, the Spanish flu of 1918 marred social integration in local and global communities, causing a loss of trust in existing institutions and estrangement and antagonism among different social and demographic groups (Dutta and Rao 2015; Picou et al. 2004).

The impacts of a pandemic often overwhelm the existing public health system, exposing the limitations of government capacity to respond to the increased demand for health care, as witnessed in the cases of 2009 H1N1 and COVID-19 (Baker, Peckham, and Seixas 2020). In times of such crises, nonprofits play an integral role in tackling various social and economic issues caused by pandemics. The critical role of nonprofit organizations, responding to external threats, suggests that a community’s capacity to mobilize resources for these organizations helps mitigate the adverse impacts of the pandemic (Paarlberg et al. 2020).

The resource mobilization mechanism during and after a pandemic involves community actors, both individuals and organizations, collectively mobilizing resources for the frontline nonprofits. The resource mobilization theory suggests that social actors in conscious communities engage in collective resource mobilization to address social problems (McCarthy and Wolfson 1996). The theory stresses the importance of social networks in the mobilization of members that support social actions and voluntary associations (Hasenfeld and Gidron 2005). According to this perspective, community resource mobilization is determined by a community’s capacity to act collectively based upon available resources (Amenta and Zylan 1991; Carbone and McMillin 2019; McCarthy and Zald 1977). When dealing with a contagious disease outbreak, communities’ collective capacity to mobilize resources for philanthropic organizations working on the frontline (e.g., community hospitals and human service organizations) can provide immediate needs (i.e., medical supplies or indispensable necessities) to affected populations, help expedite the post-pandemic recovery process, and contribute to preparing for the next wave of outbreaks (Magis 2010).

Social Capital for Resource Mobilization

Studies find that strong civic capacity facilitates the mobilization of collective resources for indispensable and humanitarian needs in response to external threats such as contagious diseases and natural disasters (Greve and Rao 2014). A community’s civic capacity is determined by its social capital, which connects people and builds trust among community members (Aldrich et al. 2021; Aldrich and Meyer 2015; Brown and Ferris 2007). Social capital is generally defined as “networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefits” (Putnam 1995:67), and scholars view social capital as a source of the collective ability to tackle grand societal challenges and build resilient communities (Aldrich 2012). Communities in terms of geographic areas are institutional fields that provide community members with the spatial platform for social interaction, and building social capital within a geographic community promotes mutual trust and advances reciprocal understanding (Marquis, Davis, and Glynn 2013; Whitham 2019). Trust and reciprocity, in turn, allow communities to overcome adverse events and adapt to extreme changes caused by external disturbances such as natural disasters (Nakagawa and Shaw 2004).

Natural disasters (e.g., hurricanes, tornadoes, storms, flooding) occur for a relatively short period and their aftermath requires physical collective action to return to normalcy. By comparison, contagious disease outbreaks have longer-term adverse impacts on local economies and sociable communities and require the practice of social distancing. The practice of social distancing can weaken social cohesion among community members because it causes social anxiety and diminishes social interaction (Dutta and Rao 2015). In such a situation, the existing social capital accumulated over time enables information sharing and helps maintain the embedded resources and benefits in communities that can be transmitted or mobilized to the underserved places or groups (Jones et al. 2009). Therefore, social capital plays a critical role in rebuilding the community’s capacity and collective motivation for resource mobilization to fight a pandemic.

Research generally finds that social capital is positively related to both individual and aggregated levels of physical health outcomes including mortality and life expectancy (Rodgers et al. 2019). Thus, a community’s capacity to respond to public health risks decreases when social capital is low (Szreter and Woolcock 2004). Likewise, high social capital is related to an effective response and sustainable recovery for communities, as found during the COVID-19 pandemic (Pitas and Ehmer 2020). Chuang and colleagues (2015) and Rönnerstrand (2014) also suggested that high levels of social capital relates to better preparedness against pandemics, including vaccination and other collective behaviors for protection. However, the impacts of social capital on the spread of contagious diseases has been found to be more complicated (Aldrich 2012; Rodgers et al. 2019). For instance, in the study of HIV infection, Frumence and colleagues’ (2014) study reported that a low level of social capital is associated with the greater likelihood of HIV infection. Mukoswa and colleagues (2017) also found that a high level of social capital (i.e., social network diversity) is associated with poor HIV treatment outcomes.

When facing a pandemic, a community’s existing resources for nonprofits working on the frontlines are quickly depleted especially when there is a lack of or delay in government resource allocation. Communities’ social capital helps the members bind together and strengthens the collective ability to mobilize resources for the frontline nonprofits in response to a pandemic (Adger 2003; Putnam 2000). The accumulated social trust and cohesion represented by social capital becomes more important when physical cooperative behaviors that build further social capital are less likely to occur due to the practice of social distancing. Therefore, in communities with a high level of social capital, collective resources can be quickly mobilized to address immediate health issues and to redistribute resources to affected populations in need. By contrast, resource mobilization for community nonprofits might be stagnant or halted in communities with a low level of social capital (Schaller 2011; Schaller and Neuberg 2012).

Hypothesis 1: The level of social capital in a community is positively associated with resource mobilization for community nonprofits responding to pandemics.

Literature suggests that the importance of a community’s social capital in resource mobilization increases as the extremity of the situation increases (Adger 2003). Social capital assists communities in overcoming constraints to resource mobilization when they face external threats such as contagious disease, natural disasters, or environmental pollution (Aldrich 2012; Hwang and Young 2020). Although contagious disease outbreaks generate social fear, loss of trust in authorities, and disturbance, empathy can be built in response to threats of pandemics in communities with large reserves of social capital. These communities are more capable of mobilizing philanthropic resources to fight pandemics (Rao and Greve 2018). In this study, we hypothesize that the relationship between social capital and resource mobilization for local philanthropic activities is moderated by the severity of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.

Hypothesis 2: The positive relationship between social capital and resource mobilization for community nonprofits is stronger in communities that are affected by pandemics more severely.

The Moderating Effect of Racial Diversity on the Relationship between Social Capital and Resource Mobilization

There exist different perspectives on how racial diversity affects community social capital (Portes and Sensenbrenner 1993). Putnam’s (2007) constrict theory suggests that cultural and racial homogeneity increases social capital, meaning that individuals are more likely to be connected in a racially homogeneous community and to trust like-minded and similar individuals (Savelkoul, Gesthuizen, and Scheepers 2011). Research finds that racial diversity is related to a lower level of aggregate social capital, suggesting that it is easier to foster social capital in homogenous communities (Hero 2003; Putnam 2000). According to the constrict theory, racial diversity erodes social capital in the community, resulting in the decline of trust and engagement in civic society, including philanthropic action such as volunteering (Rotolo and Wilson 2014). This suggests that racial diversity in a community is negatively associated with its core capacity to mobilize resources for community development (Putnam 2007).

However, more recent studies have provided a counterargument to Putnam’s constrict theory, suggesting a positive relationship between racial diversity and social capital in a community (Gerritsen and Lubbers 2010; Huijts, Kraaykamp, and Scheepers 2014). Scholars explain that it is not conclusive that racial diversity undermines social capital due to the complexity of community characteristics (Portes and Vickstrom 2011). Contrary to the constrict theory, the contact theory suggests that racially diverse communities can build strong social capital through routinized and accrued resolutions on shared anger and repeated social conflicts (Gereke, Schaub, and Baldassarri 2018; Hays 2015). According to the contact theory, racial diversity in a community has a catalytic effect on the role of social capital in motivating its members to engage in local philanthropic activities responding to external threats, thus contributing to the community’s resourcefulness (Hwang and Joo 2021).

Research also suggests that individuals and organizations in racially diverse communities are likely to experience repeated common conflicts and resolutions, which enables them to build social capital on collective efficacy (Abascal and Baldassarri 2015; Baldassarri and Abascal 2020). Therefore, racially homogeneous communities are more likely to suffer subsequent social and economic problems caused by pandemics or epidemics, whereas racially diverse communities can bridge members from different backgrounds and amplify the impact of social capital on collective action (Letki 2008). In this study, we posit that racial diversity interacts with social capital to facilitate resourcefulness and engagement in collective action during and in the aftermath of a pandemic. Hence, we hypothesize that racial diversity in a community has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between community social capital and resource mobilization for the frontline nonprofits during and in the aftermath of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.

Hypothesis 3: Racial diversity in a community has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between social capital and resource mobilization for community nonprofits responding to pandemics.

Method

Data

This study examines the relationship between social capital and resource mobilization, using the case of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in the United States. In the spring of 2009, a novel H1N1 virus emerged and spread quickly around the world (CDC 2020). World Health Organization declared the H1N1 pandemic as the first pandemic of the 2000s, and the virus infected an estimated 1.4 billion people, resulting in 936,000 hospitalizations and 75,000 deaths (CDC 2020). In the United States, the H1N1 respiratory infection began to spread in early April 2009, and all 50 states had confirmed cases of H1N1 infection by June 19. Within a year, the pandemic affected 60.8 million people and caused 12,469 deaths in the country, with one million confirmed cases in its first wave from April to July 2009 (CDC 2020). During the pandemic’s first wave, the CDC announced 43,771 hospitalization cases and 302 H1N1 virus-related deaths.

This study uses the pandemic’s first wave data in U.S. counties. The choice of a county as the unit of analysis is based on the following reasons. First, the federal government declares a state of emergency for natural disasters and outbreaks at the county level, and the responses and recovery plans are implemented at the county level as well (Domingue and Emrich 2019). Second, U.S. counties play an important role in implementing social and economic policies, and using county-level data allows for better representation of communities than would city-level data (Hoyman et al. 2016; Powers, Matthews, and Mowen 2021). Third, frontline nonprofits, such as community hospitals and human service organizations that respond to pandemic outbreaks, typically operate on the county level (Paarlberg et al. 2020). Overall, U.S. counties in the context of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic are the closest to the concept of community, defined as a socioeconomical system (Pahl 1970) and spatial platform for social interaction (Marquis et al. 2013), among other geographic units of analysis such as census tracts, zipcodes, cities, and states. We also used supplemental data from the following sources: the National Center for Charitable Statistics (NCCS) Core File, the U.S. Census Bureau, the Northeast Regional Center for Rural Development at Pennsylvania State University (PSU), and the CDC. Table 1 provides more details about our collected data.

Table 1.

Variables.

| No. | Variable | Study indicator | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Resource mobilization | Difference of contributions in years (natural log) | National Center for Charitable Statistics (2010, 2011, 2012) |

| 2 | Social capital | Social capital index | Northeast Regional Center for Rural Development (2009) |

| 3 | Racial diversity | Gini Simpson index ranging from 0 (no diversity) to 1 (perfect diversity) | U.S. Census ACS 5-year estimates (2005–2009) |

| 4 | Pandemic's severity | Categorical variables (0 = no severity, 1 =low severity; 2 = high severity) | U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2009) |

| 5 | Socioeconomic status (SES) | A factor score of poverty and unemployment rate | U.S. Census ACS 5-year estimates (2006–2010) |

| 6 | Economic inequality | Gini coefficient ranging from o (perfect equality) to 1 (perfect inequality) | U.S. Census ACS 5-year estimates (2006–2010) |

| 7 | Total population | Total population of a county (scaled by 1,000) | U.S. Census ACS 5-year estimates (2006–2010) |

| 8 | Public Funding | Public Health Emergency Response (PHER) at the state-level (natural log) | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| 9 | Political stance | % of residents voting for Democrat candidates in the 2008 election | U.S. Census |

| 10 | Elder population | % of the population 65 of age or older | U.S. Census ACS 5-year estimates (2006–2010) |

| 11 | Housing price | Average home price within the county (scaled by 1,000) | U.S. Census ACS 5-year estimates (2006–2010) |

| 12 | Local government | % of total local government employees working for local governments | U.S. Decennial Census of Population and Housing (2010) |

| 13 | Region | Four regions: Northeast, South, Midwest, and West | U.S. Census |

Note. ACS = American community survey.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is the collective resource mobilization in a county for frontline nonprofit organizations providing essential services during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. To identify local frontline nonprofits responding directly to epidemics and pandemics, we reviewed the National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities (NTEE) core codes that classify all registered 501(c)3 nonprofits into 10 major categories, 26 subcategories, and 645 categories based on specialized programs and activities. We selected 20 categories related to public health (E20, E21, E22, E32, and E70), food and nutrition (K30, K31, K34, K35, and K36), housing (L21, L24, and L41), and foundations and giving programs (T30, T31, T40, T50, T70, P60, and P70) that tend to work on the frontline fighting pandemics and epidemics. These organizations are directly involved in providing necessary goods and services to vulnerable populations during and after the pandemic (Paarlberg et al. 2020).

In this study, the support for these organizations represents communities’ collective action to mobilize resources when coping with community challenges or external threats (King 2008). Among different types of philanthropic activities, monetary contributions given to frontline nonprofits in a county during the H1N1 pandemic are used as a proxy for collective resource mobilization (Longhofer, Negro, and Roberts 2019). The dependent variable for a collective response to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic measures the differences of aggregate contributions to these organizations between pre-pandemic (2010) and post-pandemic years (2011 and 2012) using the following process. First, we obtained the sum of monetary contributions made to the 20 types of nonprofits in each county in the three years of 2010, 2011, and 2012. We then divided the monetary contributions by the county’s total population to get the county’s per capita contribution each year. 2 Next, the per capita contribution was adjusted for inflation, considering the lingering effects of the Great Recession of 2008 on inflation over years. 3 Finally, we combined the 2011 and 2012 per capita contributions to these organizations in a county and then subtracted it from the 2010 per capita contributions, in order to account for the long-term effects of the pandemic on the economy and society (Greve and Rao 2014). 4 Due to the high skewness of the distribution (16.08), we use the natural logarithm of per capita contributions as the dependent variable.

Independent and Moderating Variables

The first independent variable is a community’s social capital. Although there exist several state- and country-level social capital measurements, there are only two indices of county-level social capital during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic (Owusu-Edusei et al. 2020; U.S. Joint Economic Committee 2018). Between two measurements, we employ the social capital index from the Northeast Regional Center for Rural Development at Pennsylvania State University (PSU), developed by Rupasingha, Goetz, and Freshwater (2006) instead of Kyne and Aldrich’s (2020) social capital index for the following reasons: (1) the Penn State Social Capital Measurement captures multiple dimensions of social fabrics within a community, including the number of associations, voting rates, census responses, and density of charitable organizations per 10,000 people; (2) the Penn State Social Capital Measurement is based on Putnam’s social capital construction and generally considered more comprehensive and reliable than Kyne and Aldrich’s (2020) social capital index when measuring community volunteerism and social trust, especially in the U.S. context (Borgonovi and Andrieu 2020; Powers et al. 2021); (3) Although Kyne and Aldrich’s (2020) index offered three different measures of bridging, bonding, and linking social capital, it has not been as widely adopted as Putnam’s social capital construction (Fraser, Aldrich, and Page-Tan 2021); and (4) using the Penn State Social Capital Measurement allows us to verify Putnam’s constrict theory directly by using the measures based on his own theory to test the moderating effect of racial diversity on social capital-resource mobilization relationship in the case of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.

The second independent variable is racial diversity in a county. Counties’ racial diversity index was calculated as follows:

where n represents the number of people in a county who identified as each (i) of the six racial groups (i.e., Non-Hispanic white, black, Hispanic or Latino, Asian, American Indian or Native Hawaiian, and other races), N represents the total population, and m represents the number of racial categories in the county. 5 The racial diversity index ranges from 0 (perfectly homogeneous) to 1 (perfectly diverse). This variable is also employed as a moderator of the relationship between social capital and the dependent variable.

The third independent variable is the severity of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic’s impact. We used the number of H1N1-related hospitalizations per 1,000 population to measure the severity of the pandemic in communities. Based on this number, three levels of severity were classified: no hospitalization cases, low severity, and high severity (Aguinis, Edwards, and Bradley 2017). 6 Among 3,150 US counties in the study, H1N1-associated hospitalization cases were reported in 958 counties: 2,192 counties had no reported hospitalization cases. Using the mean of hospitalization cases per 1,000 population (2) as a threshold, 958 counties are classified in two categories: the low level of severity (in 719 counties) and the high level of severity (in 239 counties). Figure 2 illustrates the levels of severity across all U.S. counties during the first wave. This variable was used as a moderator in the moderated multiple regression (MMR) to test whether the relationship between the social capital and resource mobilization is contingent on the severity of the pandemic (Aguinis and Gottfredson 2010).

Figure 2.

2009 H1N1 hospitalizations from April 2009 to July 2009.

Control Variables

The model includes a set of community characteristics as control variables. First, it controls for community socioeconomic status, including the county’s poverty rate, unemployment rate, economic inequality, and the average home price. A composite index of economic condition is created using a factor score due to the high correlation between poverty and unemployment rates, and the Gini coefficient in each county, ranging from 0 to 1, is used as the economic inequality measure. The average housing price is also included as a control variable due to its high correlation with community wealth (Brady 2011). Second, older adults are generally more vulnerable to contagious diseases as well as to respiratory infectious diseases in particular (Viegi et al. 2009). Therefore, we include the percentage of the population 65 of age or older at the county level. Third, counties’ total population and census region information are also included as control variables (e.g., the Northeast, South, West, and Midwest). Fourth, as a measure of government resources for relief, we employ a state-level public health emergency response (PHER) fund by Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic (CDC 2021). Fifth, the model includes the percentage of employees working for local government in order to control for the local government’s capacity to capitalize on existing resources and promote collective action (Kyne and Aldrich 2020; Murphy 2007). Finally, considering that communities’ responses to pandemics and other disasters are highly politicized, the proportion of residents who voted for the Democrat candidate in the 2008 presidential election is included to control for the differences in political stance across communities.

Statistical Model

To test the relationship between social capital and resource mobilization during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic with moderating effects of racial diversity and the severity of the pandemic on the relationship, we constructed a cross-sectional data set to run the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models. In particular, we use the MMR models to analyze the interaction effect between social capital and the pandemic’s severity and tested the moderating effect of racial diversity on the primary relationship between social capital and resource mobilization for local nonprofits (Aguinis and Gottfredson 2010; Aguinis and Pierce 1998). As a supplementary analysis to confirm the results of our MMR models, we also ran a three-way interaction model by including all three independent variables (e.g., social capital, racial diversity, and the severity of the pandemic’s impact). The three-way interaction term allows us to estimate the interaction with both pandemic’s severity and racial diversity in a county as moderators (Dawson and Richter 2006). Finally, since this analysis focuses on the aftermath of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic (t = 2010), we run the model using two lagged terms for the independent and control variables (t − 1 or t − 2) in order to alleviate endogeneity concerns. 7

Results

Table 2 provides a summary of descriptive statistics and correlations for all variables. The mean variance inflation factor (VIF) of the base models ranges from 1.60 to 1.66, which suggests that multicollinearity is not of concern. To investigate the relationship between social capital and resource mobilization, we tested linear regression models without interaction or moderation effects (Models 1, 2, and 3 for Hypothesis 1), a model with the interaction between social capital and the pandemic’s severity (Model 4 for Hypothesis 2), and models with the moderating effect of racial diversity and severity (Models 5 and 7 for Hypothesis 3). Table 3 presents the results of the regression analyses.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations.

| No. | Variable | M | SD | Minimum | Maximum | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Resource mobilization | 6.90 | 0.18 | 1.00 | 9.09 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 2 | Social capital | −0.01 | 1.34 | −3.94 | 17.55 | .03 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 3 | Racial diversity | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.74 | .08 | −.36 | 1.00 | |||||

| 4 | Severity of the pandemic | 0.38 | 0.62 | 0.00 | 2.00 | .12 | −.15 | .14 | 1.00 | ||||

| 5 | Socioeconomic status | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.31 | −.03 | −.41 | .30 | −.09 | 1.00 | |||

| 6 | Economic inequality | 0.43 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.65 | .16 | −.12 | .33 | .03 | .52 | 1.00 | ||

| 7 | Total population | 93.55 | 299.70 | 0.04 | 9,604.87 | .17 | −.16 | .26 | .22 | −.04 | .14 | 1.00 | |

| 8 | Public funding | 17.10 | 0.78 | 15.26 | 18.91 | −.03 | −.29 | .27 | .15 | .13 | .07 | .18 | 1.00 |

| 9 | Political stance | 41.44 | 13.79 | 4.91 | 92.46 | .21 | −.06 | .18 | .23 | .22 | .20 | .26 | .07 |

| 10 | Elder population | 0.30 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 18.62 | −.11 | .43 | −.14 | −.16 | −.15 | −.06 | −.11 | −.14 |

| 11 | Housing price | 131.62 | 85.65 | 29.70 | 868.00 | .21 | −.07 | .18 | .25 | −.30 | −.01 | .39 | .19 |

| 12 | Local government | 18.93 | 7.10 | 3.88 | 100.00 | −.14 | .12 | .13 | −.10 | .10 | .02 | −.11 | .02 |

| 13 | Region: Northeast | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 1.00 | .10 | −.04 | −.09 | .24 | −.14 | −.02 | .14 | .11 |

| 14 | Region: South | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −.10 | −.37 | .47 | −.09 | .36 | .33 | −.05 | .20 |

| 15 | Region: West | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 1.00 | .04 | .09 | −.02 | .03 | −.07 | −.07 | .06 | −.11 |

| No. | Variable | M | SD | Minimum | Maximum | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| 9 | Political stance | 41.44 | 13.79 | 4.91 | 92.46 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 10 | Elder population | 0.30 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 18.62 | −.23 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 11 | Housing price | 131.62 | 85.65 | 29.70 | 868.00 | .34 | −.16 | 1.00 | |||||

| 12 | Local government | 18.93 | 7.10 | 3.88 | 100.00 | −.08 | .38 | −.09 | 1.00 | ||||

| 13 | Region: Northeast | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 1.00 | .23 | −.09 | .23 | −.05 | 1.00 | |||

| 14 | Region: South | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.00 | 1.00 | −.20 | −.09 | −.15 | −.04 | −.25 | 1.00 | ||

| 15 | Region: West | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 1.00 | .09 | .05 | .25 | .14 | −.12 | −.40 | 1.00 | |

Table 3.

Moderated Multiple Regression Results.

| DV: Resource mobilization | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social capital | 0.00633** (0.00297) |

0.00778*** (0.00298) |

0.00844*** (0.00300) |

0.00649** (0.00314) |

0.00620 (0.00448) |

0.00761** (0.00301) |

0.00545 (0.00477) |

| Racial diversity | 0.0890*** (0.0216) |

0.0853*** (0.0217) |

0.0886*** (0.0217) |

0.0888*** (0.0223) |

–0.446** (0.203) |

0.0698*** (0.0243) |

|

| Severity of the pandemic | 0.00923* (0.00516) |

0.0103** (0.00518) |

0.00930* (0.00516) |

0.00964* (0.00516) |

–0.00807 (0.00975) |

||

| Social capital × Severity | 0.00820** (0.00394) |

0.00316 (0.00660) |

|||||

| Social capital × Racial diversity | 0.00881 (0.0131) |

0.000105 (0.0145) |

|||||

| Racial diversity × Economic inequality | 1.216*** (0.463) |

||||||

| Racial diversity × Severity | 0.0796** (0.0315) |

||||||

| Social capital × Severity × Diversity | 0.0385* (0.0232) |

||||||

| Socioeconomic status | –0.162 (0.112) |

–0.157 (0.112) |

–0.131 (0.113) |

–0.127 (0.113) |

–0.139 (0.114) |

–0.145 (0.113) |

–0.122 (0.114) |

| Economic inequality | 0.907*** (0.103) |

0.862*** (0.103) |

0.852*** (0.103) |

0.851*** (0.103) |

0.852*** (0.103) |

0.491*** (0.172) |

0.836*** (0.103) |

| Total population | 3.74e-05*** (1.11e-05) |

2.79e-05** (1.13e-05) |

2.68e-05** (1.13e-05) |

2.92e-05** (1.14e-05) |

2.77e-05** (1.14e-05) |

2.35e-05** (1.14e-05) |

2.88e-05** (1.16e-05) |

| Public funding | –0.0136*** (0.00411) |

–0.0154*** (0.00412) |

–0.0159*** (0.00413) |

–0.0149*** (0.00416) |

–0.0160*** (0.00414) |

–0.0160*** (0.00413) |

–0.0144*** (0.00417) |

| Political stance | 0.00108*** (0.000268) |

0.000877*** (0.000272) |

0.000820*** (0.000274) |

0.000802*** (0.000274) |

0.000819*** (0.000274) |

0.000766*** (0.000274) |

0.000780*** (0.000274) |

| Elder population | –0.0129*** (0.00464) |

–0.0120*** (0.00463) |

–0.0118** (0.00463) |

–0.0111** (0.00464) |

–0.0113** (0.00468) |

–0.0122*** (0.00463) |

–0.0109** (0.00469) |

| Housing price | 0.000275*** (4.62e-05) |

0.000259*** (4.63e-05) |

0.000257*** (4.63e-05) |

0.000253*** (4.63e-05) |

0.000254*** (4.65e-05) |

0.000261*** (4.63e-05) |

0.000240*** (4.67e-05) |

| Local government | –0.00235*** (0.000462) |

–0.00279*** (0.000473) |

–0.00275*** (0.000474) |

–0.00276*** (0.000473) |

–0.00276*** (0.000474) |

–0.00264*** (0.000475) |

–0.00268*** (0.000474) |

| Region: Northeast | 0.00980 (0.0130) |

0.0132 (0.0130) |

0.0100 (0.0131) |

0.0102 (0.0131) |

0.00953 (0.0131) |

0.00976 (0.0131) |

0.0122 (0.0132) |

| Region: South | –0.0297*** (0.00823) |

–0.0450*** (0.00901) |

–0.0439*** (0.00903) |

–0.0448*** (0.00903) |

–0.0448*** (0.00913) |

–0.0420*** (0.00905) |

–0.0455*** (0.00912) |

| Region: West | –0.00764 (0.00947) |

–0.0126 (0.00952) |

–0.0127 (0.00952) |

–0.0113 (0.00954) |

–0.0127 (0.00952) |

–0.0112 (0.00952) |

–0.0102 (0.00954) |

| Constant | 6.743*** (0.0803) |

6.794*** (0.0810) |

6.803*** (0.0812) |

6.787*** (0.0815) |

6.807*** (0.0814) |

6.961*** (0.101) |

6.791*** (0.0818) |

| Observations | 3,150 | 3,150 | 3,150 | 3,150 | 3,150 | 3,150 | 3,150 |

| R 2 | .119 | .123 | .124 | .126 | .124 | .126 | .128 |

Note. Standard error in parentheses. DV = dependent variable.

p < .10. **p < .05. ***p < .01 (two-tailed test).

The results in Model 1 of Table 3 reveal a positive association between community social capital and resource mobilization during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic (β = 0.0063, p < 0.05 in Model 1), supporting Hypothesis 1. Interpreting coefficients when the dependent variable is in a logarithmic form requires exponentiating the coefficient, subtracting one from the exponentiated number, and then multiplying this by 100 (Benoit 2011). Hence, the coefficient of social capital 0.0063 means that every one-unit in social capital index increases, our dependent variable increases by about 0.63 percent when other variables are controlled: [(exp( – 1) × 100]. In Model 2, the coefficient of racial diversity is 0.089 (p < 0.01), which indicates every one-unit in racial diversity index increases, the dependent variable increases by about 9.3 percent when others are controlled. In Model 3, a linear regression analysis including all variables indicates that social capital and racial diversity are positively associated with resource mobilization, which affirms that Hypothesis 1 is supported.

Model 4 tests the moderating effects of the severity of the pandemic on the relationship between social capital and the dependent variable, and the MMR results suggest that the association between social capital and resource mobilization is stronger in the counties hit by the pandemic more severely (β = 0.0082, p < 0.05). Figure 3 shows a significant and positive interaction effect of social capital and the severity of the pandemic on philanthropic resource mobilization: there is a positive relationship between social capital and resource mobilization, and the relationship was stronger in the communities that were affected by H1N1 more severely. In Figure 3, it appears that the 95 percent confidence intervals overlap across the levels of severity, especially between the high and low levels of severity. Research suggests that assessing the significance of nonlinear interaction effect via confidence intervals alone is limited (Belia et al. 2005; Mize 2019). The only way to know whether there are statistically significant group differences is, in fact, to test for the differences (Mize 2019). Overall, in spite of the overlapping intervals, the significant differences of predicted groups means across the levels suggest that the relationship between social capital and resource mobilization is moderated by the severity of pandemic (Belia et al. 2005). This finding supports Hypothesis 2.

Figure 3.

Moderating effects of the severity of the pandemic on the social capital-resource mobilization relationship.

Models 5 and 7 test Hypothesis 3 on the moderating effects of racial diversity. The results of Model 5 reveal a positive moderating effect of a community’s racial diversity on the relationship between its social capital and resource mobilization, but it is not statistically significant (β = 0.0088, p > 0.1). We then ran a three-way interaction among racial diversity, social capital, and the pandemic’s severity in Model 7 as a robustness check, and the results show positive and statistically significant coefficients (β = 0.0385, p < 0.1). Figure 4 is the linear prediction plot of the three-way interaction, indicating a significant and positive interaction effect of racial diversity and social capital on resource mobilization moderated by the level of severity of the pandemic. 8 In counties with no hospitalization cases, racial diversity is not positively associated with resource mobilization or social capital index (the first graph in Figure 4). By contrast, in counties with two or fewer than two hospitalization case(s) per 1,000 population (low severity), racial diversity has a positive moderating effect on the social capital-resource mobilization relationship.

Figure 4.

Three-way interaction among racial diversity, severity of the pandemic, and social capital on resource mobilization.

Moreover, this interaction effect becomes greater in counties with more hospitalization cases per 1,000 population (high severity). Figure 4 depicts how the social capital-resource mobilization relationship changes depending on the three different levels of pandemic severity and racial diversity. The differences of predicted groups means become greater as the level of severity increases. Although the 95 percent confidence intervals overlap across three levels of racial diversity (see Figure 4), the statistical significance in Model 7 may indicate that the predicted group difference is significant across three types of communities based on the levels of racial diversity (Mize 2019). Overall, these results partially support Hypothesis 3, suggesting that a community’s social capital enhances its resource mobilization for local nonprofit organizations, and its racial diversity plays a moderating role in enhancing the effect of the social capital on resource mobilization for local nonprofits fighting the pandemic on the frontline.

The results also reveal interesting patterns between some of the control variables and the dependent variable. First, a variable for the emergency federal funding to state government is negatively associated with the resource mobilization during the pandemic. The proxy variable for local government capacity is also negatively associated with the resource mobilization. These results offer evidence for the crowding out effect of government resources on local philanthropic resources (Payne 1998). Second, the socioeconomic status index is negatively associated with the resource mobilization, but the relationship is not statistically significant. Research finds that there is the tradition of compassion and mutual help in economically disadvantaged communities, which may explain the negative association between a community’s economic situation and philanthropic resource mobilization (Bennett 2012; Piff et al. 2010). Third, the results reveal a positive association between economic inequality and resource mobilization. Although the causal mechanism between economic inequality and resource mobilization is beyond the scope of this study, it is possible that the wealthy may be more sympathetic to vulnerable populations affected by external threats in a community with greater economic inequality (Berrebi, Karlinsky, and Yonah 2021; Piff et al. 2010).

In addition, we tested an interaction effect of racial diversity and economic inequality on resource mobilization. The results of Model 6 show a positive interaction (β = 1.216, p < 0.01), also shown in Figure 5. Figure 5 reveals that racial diversity is positively associated with resource mobilization in communities with high economic inequality. Although the confidence intervals for the three levels of economic inequality all overlap, the significant differences in mean values across the groups suggest that the relationship between social capital and resource mobilization is moderated by the levels of economic inequality (Belia et al. 2005; Mize 2019). In this study, the significant coefficients of a moderating effects in a regression model and the significant difference across predicted group means suggest that the role of social capital varies depending on racial diversity and the severity of a pandemic. The results also imply that racial diversity is negatively associated with resource mobilization in communities with a low level of economic inequality. This contrasting relationship calls for further research. 9

Figure 5.

Interaction between income inequality and racial diversity on resource mobilization.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study examined how a set of community characteristics relates to the resource mobilization for frontline nonprofits responding to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, using the theoretical framework of social capital and resource mobilization theories (McCarthy and Zald 1977). This study also tested the moderating effects of racial diversity on the relationship between social capital and resource mobilization. Our analysis of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic data reveals that a community’s social capital is positively associated with its philanthropic resource mobilization for local nonprofits fighting the pandemic. The findings suggest that a community’s racial diversity has a moderating effect on the relationship between its social capital and resource mobilization. Last, the findings reveal that the positive relationship between a community’s social capital and philanthropic resource mobilization for collective action is stronger in communities that are more severely affected by the pandemic.

Scholars suggest that a community’s social capital enhances its capacity to mobilize physical, financial, and social resources for relief activities during and after a disaster (Aldrich and Meyer 2015; Chamlee-Wright and Storr 2011). This study contributes to the literature by finding that the positive impacts of social capital on communities’ responsiveness to pandemics and their recovery from disasters are contingent upon various socioeconomic contexts. Research finds that, during emergency situations, social capital often connects individuals and groups with homogenous characteristics, which weakens the effectiveness of social capital in collective response to crises (Klinenberg 2003). In this case, high levels of social capital, especially in racially homogeneous communities, may impede the recovery process from external threats (Hawkins and Maurer 2010; Monteil, Simmons, and Hicks 2020).

Existing research suggests that contagious diseases evoke antagonism against outgroup populations such as immigrants and racial minorities (Crandall and Schaller 2005; Dutta and Rao 2015). However, our findings reveal that resource mobilization for frontline nonprofits is more likely to occur in a more racially diverse community. These findings imply that racial diversity in a community contributes to enhancing the community’s capacity for resource mobilization in response to crises, which contradicts Putnam’s (2007) constrict theory. Diverse communities, in terms of racial identities and socioeconomic statuses, have more heterogeneous social networks and human capital pools, which contribute to the community’s resourcefulness. Resourcefulness of a community then promotes collective resource mobilization for disaster relief activities (Paarlberg, Hoyman, and McCall 2018).

Putnam (2007) suggested that cooperative and collective behaviors are limited in racially diverse communities because racial diversity erodes social capital and trust (Habyarimana et al. 2009). However, our findings reveal that, when facing imminent external threats, like the H1N1 pandemic of 2009, social capital is positively associated with the collective capacity for resource mobilization: the effects of social capital on resource mobilization increases in a racially diverse community (Figure 4). On the other hand, the benefits of social capital on the community outcomes interacting with racial diversity differ within community contexts because the benefits of social capital is not equally distributed across communities (Hawes and Rocha 2011; Hero 2007). According to Hawes and McCrea (2018), social capital reinforces social pressures through institutional norms and sanctions, which leads to the unequal distribution of social capital to racial minorities. Racial minorities have social and economic disadvantages in accessing information through their limited social networks (Hero 2003, 2007; Meier and Stewart 1991). For instance, studies show that, while social capital in general is linked to more equal outcomes of health care and education services, access to such services are more unequally distributed within racially diverse communities (Hawes and Rocha 2011; Zhu 2017).

Portes and Vickstrom (2011) also argue that the negative relationship between social capital and racial diversity is at least in part due to the economic inequality and income disparities across races which can disintegrate the entire social structures. Our supplementary findings (Table A1 and Figure A1 in the appendix) suggest that the effect of social capital on resource mobilization is highly affected by the levels of racial diversity and economic inequality in the case of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, which supports their argument. Our supplementary findings also provide implications for future research about how the relationship between social capital and resource mobilization may differ, contingent upon racial diversity and economic inequality in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic. As social structures become complex and interdependent, a concept of social capital shifts from mechanical solidarity based on similarity and homogeneity to organic solidarity stemming from differentiated and heterogeneous society as “movement society” adopt to social change (Durkheim [1893] 1984; McAdam et al. 2005). This implies that equal distribution of economic resources and inclusion of diverse groups and individuals in a community contribute to its capacity for addressing grand societal challenges. Further research on how social capital relates to resource mobilization in different racial, economic, and other social contexts will contribute to better understanding the role of social capital.

During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, the inconsistencies in federal policies left local governments and agencies having to decide appropriate actions on their own (Glanz, Bloch, and Singhvi 2020). In the meantime, many people relied on the frontline nonprofit organizations for various needs such as public health, housing, and food security. Mobilization of philanthropic resources for these organizations enables them to provide medical and humanitarian services when the public sector organizations have limited capacity to respond promptly (Brudney and Gazley 2009). This study makes a unique contribution to the literature by providing evidence that racial diversity in communities positively moderates the relationship between social capital and resource mobilization.

COVID-19 has had tremendous impacts on our lives and it will impact us for years to come. Compared with the H1N1 pandemic case, communities’ collective responses during the COVID-19 pandemic vary substantially by their political stances, and this may distort the public health outcome of the COVID-19 (Fraser et al. 2021; Stuart, Petersen, and Gunderson 2022). Moreover, COVID-19 is known to spread more easily than H1N1 and has been observed to have more superspreading events than H1N1 (Vessey and Betz 2020). The high transmissibility of COVID-19 contributed to the widespread fear of contagion, which implies that the culture of diversity and inclusion in a community will play an even more important role in the resource mobilization for mitigating the adverse impacts of the pandemic.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, there is a limitation for generalizability because our data are limited to the H1N1 pandemic of 2009. This study draws upon the disasters frame since natural disasters and contagious disease infections share similarities in terms of their impacts and communities’ coping strategies (Rao and Greve 2018). Although social capital facilitates post-disaster recovery (Chamlee-Wright and Storr 2011), epidemics and pandemics also create cognitive threats to sociable communities, generating fear and eroding social cohesion, unlike natural disasters whose impacts tend to be limited to economic and social infrastructures (Crandall and Schaller 2005; Picou et al. 2004). In particular, throughout history, pandemics and disasters have been associated with stigmatization and “othering” of people, targeted to certain racial and ethnic groups (Gover, Harper, and Langton 2020; Peek and Meyer 2016). For instance, the SARS outbreak of 2002–2004 and COVID-19 fueled anti-Asian racism and xenophobia. The 2009 H1N1 pandemic did not create as much antagonism toward specific racial groups as did SARS or COVID-19 (Rothgerber et al. 2020), and we used the composition of multiple racial groups. Using detailed information about communities’ racial composition will help understand the effect of racial diversity on social capital in times of highly politicized pandemics and other disasters.

Next, the social capital index (Penn State Social Capital Measurement) used in this study is a county-level aggregate measure. Without individual-level social capital information, our findings cannot be generalized to understand why people donate to a nonprofit organization fighting a pandemic. The Penn State Social Capital Measurement is also based on the overall measures of social capital and does not distinguish different types of social capital, such as bonding, bridging, and linking types (Kyne and Aldrich 2020). Although the Penn State Social Capital Measurement is currently the most widely used measure of community social capital (Powers et al. 2021; Rupasingha and Goetz 2008; Rupasingha et al. 2006), future research can adopt different indices of social capital to better understand the community social capital-resource mobilization link.

The 2009 H1N1pandemic was the first pandemic in the 2000s, and this study offers useful insights on communities’ response to other pandemic situations, including COVID-19. This study’s findings suggest that existing social capital in a community is closely related to its resource mobilization for its fight against pandemics (Borgonovi and Andrieu 2020). The findings also imply that enhancing community social capital and creating diverse and inclusive culture facilitate the mobilization of philanthropic resources. Pandemics and other disasters tend to have disproportionate impacts on marginalized communities and individuals, and enhanced social capital and diverse and inclusive culture may contribute to minimizing pandemics’ impacts (Lee and Hwang 2020). Therefore, establishing and implementing inclusive public policies that embrace social and racial diversity in communities should be a priority of local government policy making.

Appendix

Table A1.

Multiple Regression Results: Moderating Effects of Economic Inequality.

| DV: Resource mobilization | Model A1 | Model A2 | Model A3 | Model A4 | Model A5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social capital | 0.00939*** (0.00299) |

0.00739* (0.00448) |

0.00919 (0.00678) |

0.00842*** (0.00301) |

0.0351*** (0.0109) |

| Racial diversity | 0.0836*** (0.0218) |

0.0868*** (0.0224) |

0.0835*** (0.0219) |

−0.0754 (0.0561) |

−0.132** (0.0607) |

| Economic inequality | 0.0385*** (0.00515) |

0.0384*** (0.00515) |

0.0385*** (0.00515) |

0.0175** (0.00852) |

0.0185** |

| (0.00892) | |||||

| Severity of the pandemic | 0.00924* (0.00517) |

0.00930* (0.00517) |

0.00924* (0.00518) |

0.00959* (0.00517) |

0.00945* (0.00516) |

| Social capital × Racial diversity | 0.00789 (0.0131) |

−0.157*** (0.0398) |

|||

| Social capital × Economic inequality | 0.000101 (0.00302) |

−0.0139*** (0.00511) |

|||

| Economic inequality × Racial diversity | 0.0751*** (0.0244) |

0.0993*** (0.0260) |

|||

| Social capital × Economic inequality × Racial diversity | 0.0739*** (0.0171) |

||||

| Socioeconomic status | −0.0313 (0.110) |

−0.0380 (0.110) |

−0.0311 (0.110) |

−0.0504 (0.110) |

−0.0931 (0.111) |

| Total population | 2.85e-05** (1.13e-05) |

2.94e-05** (1.14e-05) |

2.86e-05** (1.14e-05) |

2.48e-05** (1.14e-05) |

2.77e-05** (1.15e-05) |

| Public funding | −0.0159*** (0.00414) |

−0.0160*** (0.00415) |

−0.0159*** (0.00414) |

−0.0160*** (0.00414) |

−0.0155*** (0.00413) |

| Political stance | 0.000834*** (0.000274) |

0.000832*** (0.000274) |

0.000834*** (0.000275) |

0.000763*** (0.000275) |

0.000726*** |

| (0.000274) | |||||

| Elder population | −0.0116** (0.00464) |

−0.0112** (0.00469) |

−0.0116** (0.00465) |

−0.0120*** (0.00463) |

−0.0122*** (0.00468) |

| Housing price | 0.000276*** (4.62e-05) |

0.000273*** (4.64e-05) |

0.000276*** (4.64e-05) |

0.000283*** (4.62e-05) |

0.000280*** (4.64e-05) |

| Local government | −0.00275*** (0.000475) |

−0.00275*** (0.000475) |

−0.00275*** (0.000475) |

−0.00260*** (0.000476) |

−0.00243*** (0.000478) |

| Region: Northeast | 0.0115 (0.0131) |

0.0111 (0.0132) |

0.0115 (0.0131) |

0.0117 (0.0131) |

0.0102 (0.0131) |

| Region: South | −0.0408*** (0.00900) |

−0.0416*** (0.00910) |

−0.0408*** (0.00901) |

−0.0389*** (0.00901) |

−0.0421*** (0.00915) |

| Region: West | −0.0130 (0.00954) |

−0.0130 (0.00954) |

−0.0130 (0.00954) |

−0.0117 (0.00953) |

−0.0130 (0.00952) |

| Constant | 7.078*** (0.0706) |

7.082*** (0.0708) |

7.078*** (0.0706) |

7.121*** (0.0719) |

7.117*** (0.0720) |

| Observations | 3,150 | 3,150 | 3,150 | 3,150 | 3,150 |

| R 2 | .121 | .121 | .121 | .124 | .129 |

Note. Standard error in parentheses. In Models A4 and A5, an economic inequality variable is categorical ranging from 1 (low economic inequality) to 3 (high economic inequality). DV = dependent variable.

p < .10. **p < .05. ***p < .01 (two-tailed test).

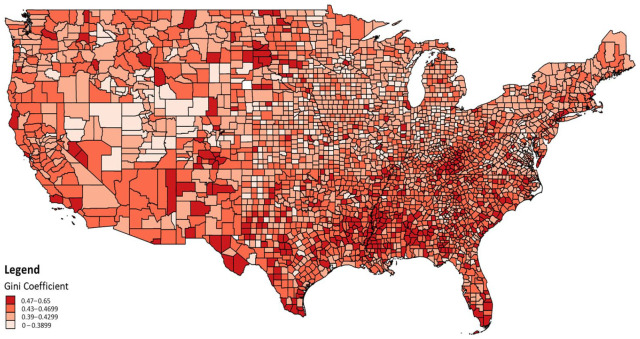

Figure A1.

Economic inequality represented by Gini coefficient across U.S. counties.

Source. From Lee and Hwang 2020.

Figure A2.

Three-way interaction among economic inequality, racial diversity, and social capital on resource mobilization.

An exception is Rao and Greve’s (2018) study which examined how the cooperative movement of Norwegian retail associations strengthened the community capacity to form new nonprofit organizations in the aftermath of the Spanish flu pandemic between 1918 and 1920. The relationship between social capital and community capacity during pandemics has not been tested in more recent contexts.

Our dependent variable, the difference in per capita aggregate monetary contribution to the frontline nonprofits, is obtained from the NCCS Core File in 2010, 2011, and 2012. The NCCS Core File lists all 501(c)3 nonprofits that file 990 forms to the IRS. In the NCCS Core File, we aggregated “total contribution” variable, which represents monetary contributions, gifts, and grants from individuals and organizations. This variable may include government grants, which are not reported as a separate category in the NCCS Core File. This prevents the study from identifying aggregated monetary contributions from community residents and organizations unfortunately. Despite the limitation, studies report that today’s nonprofit organizations receive relatively little revenue from government (median = 0) in the form of grants and most government funding comes in the form of fees for service (Kerlin and Pollak 2011; Tinkelman and Neely 2011).

When the 2008 financial crisis hit the United States, inflation spiked, which escalated economic insecurity and uncertainty among nonprofit organizations in the following years (Lee and Shon 2018).

The year 2012 is considered the end of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, and the CDC released the final mortality report for the H1N1 2009 in 2012.

This measure was adopted from U.S. Census Bureau’s classification.

This study uses the number of hospitalization cases as a proxy for severity because the number of confirmed cases was too large and the mortality rate was too low to measure the impact of H1N1 infection on frontline nonprofit organizations ( Lee and Hwang 2020; Narain, Kumar, and Bhatia 2009). CDC also stopped reporting the number of confirmed cases by July 23, 2009. In addition, the majority of those who were tested positive experienced mild, self-limiting or no symptom (Narain et al. 2009), with little impact on public health (Presanis et al. 2011). The number of hospitalization cases was then transformed to a categorical moderator (no hospitalization, low severity and high severity). If county’s hospitalization cases per 1,000 population are two or below, it is categorized as the low level of severity. If greater than two, it is categorized as the high level of severity.

A control variable for the percentage of local government employees in the total population with employment is obtained from Decennial Census of Population and Housing in 2010. The data set was released on April 1, 2010.

Figure 4 visualizes a complex relationship among social capital, racial diversity, and the severity of H1N1 pandemic. A severity variable is categorical; however, racial diversity and social capital variables are continuous variables. The counties with the racial diversity index one standard deviation (0.181) or above the mean (0.280) are classified as high diversity communities and the counties with the racial diversity index one standard deviation below or less as low diversity communities. Figure 5 is also based on this categorization of racial diversity.

We also ran a three-way interaction of social capital, racial diversity, and economic inequality on resource mobilization (see Table A1 in the appendix). To run a three-way interaction, the economic inequality variable (Gini coefficient) was transformed to numbers from 1 (low economic inequality; below 25 percent of distribution) to 3 (high economic inequality; above 75 percent of distribution). Figure 5 for Model 6 in Table 3 shows the interaction between racial diversity and economic inequality on resource mobilization; however, this interaction is not directly related to social capital. Our additional analyses in Table A1 also shows the intertwined relationship among communities’ social capital, racial diversity, and economic inequality on resource mobilization (Portes and Vickstrom 2011; Uslaner and Brown 2005). Figure A1 visually presents economic inequality measured by Gini coefficient across all U.S. counties. Figure A2 depicts the results of Model A5 in Table A1, which show that, in communities with high and low levels of economic inequality, racial diversity has contrasting moderating effects on the social capital and resource mobilization relationship. In communities with the mid-level of economic inequality, however, racial diversity has a consistently positive moderating effect on resource mobilization. While racial diversity is negatively associated with resource mobilization in communities with low economic inequality, it moderates the relationship between social capital and the collective outcome of a community with high economic inequality. Thus, our supplementary findings suggest that the effect of social capital on collective action (resource mobilization in this study) is compounded by economic inequality in the community, which contradicts Putnam’s argument (Portes and Vickstrom 2011).

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Hyunseok Hwang  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7285-3764

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7285-3764

References

- Abascal Maria, Baldassarri Delia. 2015. “Love Thy Neighbor? Ethnoracial Diversity and Trust Reexamined.” American Journal of Sociology 121:722–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adger W. Neil. 2003. “Social Capital, Collective Action, and Adaptation to Climate Change.” Economic Geography 79:387–404. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis Herman, Edwards Jeffrey R., Bradley Kyle J.2017. “Improving Our Understanding of Moderation and Mediation in Strategic Management Research.” Organizational Research Methods 20:665–85. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis Herman, Gottfredson Ryan K.2010. “Best-Practice Recommendations for Estimating Interaction Effects Using Moderated Multiple Regression.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 31:776–86. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis Herman, Pierce Charles A.1998. “Testing Moderator Variable Hypotheses Meta-Analytically.” Journal of Management 24:577–92. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich Daniel P.2012. Building Resilience: Social Capital in Post-Disaster Recovery. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich Daniel P., Kolade Oluwaseun, McMahon Kate, Smith Robert. 2021. “Social Capital’s Role in Humanitarian Crises.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34:1787–809. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich Daniel P., Meyer Michelle A.2015. “Social Capital and Community Resilience.” American Behavioral Scientist 59:254–69. [Google Scholar]

- Amenta Edwin, Zylan Yvonne. 1991. “It Happened Here: Political Opportunity, the New Institutionalism, and the Townsend Movement.” American Sociological Review 56:250–65. [Google Scholar]

- Baker Marissa G., Peckham Trevor K., Seixas Noah S.2020. “Estimating the Burden of United States Workers Exposed to Infection or Disease: A Key Factor in Containing Risk of COVID-19 Infection.” PLoS ONE 15:e0232452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldassarri Delia, Abascal Maria. 2020. “Diversity and Prosocial Behavior.” Science 369:1183–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belia Sarah, Fidler Fiona, Williams Jennifer, Cumming Geoff. 2005. “Researchers Misunderstand Confidence Intervals and Standard Error Bars.” Psychological Methods 10:389–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett Roger. 2012. “Why Urban Poor Donate: A Study of Low-Income Charitable Giving in London.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 41:870–91. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit Kenneth. 2011. “Linear Regression Models with Logarithmic Transformations.” Retrieved August 6, 2022 (https://links.sharezomics.com/assets/uploads/files/1600247928973-from_slack_logmodels2.pdf).

- Berrebi Claude, Karlinsky Ariel, Yonah Hanan. 2021. “Individual and Community Behavioral Responses to Natural Disasters.” Natural Hazards 105:1541–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmik Joy, Selim Samiya Ahmed, Irfanullah Haseeb Md, Shuchi Jannat Shancharika, Sultana Rumana, Ahmed Shaikh Giasuddin. 2021. “Resilience of small-scale marine fishers of Bangladesh against the COVID-19 pandemic and the 65-day fishing ban.” Marine Policy 134: 104794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bixler R. Patrick, Paul Sandeep, Jones Jessica, Preisser Matthew, Passalacqua Paola. 2021. “Unpacking Adaptive Capacity to Flooding in Urban Environments: Social Capital, Social Vulnerability, and Risk Perception.” Frontiers in Water 3:728730. [Google Scholar]

- Bloemraad Irene. 2006. “Becoming a Citizen in the United States and Canada: Structured Mobilization and Immigrant Political Incorporation.” Social Forces 85:667–95. [Google Scholar]

- Borgonovi Francesca, Andrieu Elodie. 2020. “Bowling Together by Bowling Alone: Social Capital and Covid-19.” Social Science & Medicine 265:113501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgonovi Francesca, Andrieu Elodie, Subramanian S. V.2021. “The Evolution of the Association between Community Level Social Capital and COVID-19 Deaths and Hospitalizations in the United States.” Social Science & Medicine 278:113948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady Ryan R.2011. “Measuring the diffusion of housing prices across space and over time.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 26: 213–31. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Eleanor, Ferris James M.2007. “Social Capital and Philanthropy: An Analysis of the Impact of Social Capital on Individual Giving and Volunteering.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 36:85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Brudney Jeffrey L., Gazley Beth. 2009. “Planing to Be Prepared: An Empirical Examination of the Role of Voluntary Organizations in County Government Emergency Planning.” Public Performance & Management Review 32:372–99. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone Jason T., McMillin Stephen Edward. 2019. “Reconsidering Collective Efficacy: The Roles of Perceptions of Community and Strong Social Ties.” City & Community 18:1068–85. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010. “The 2009 H1N1 Pandemic: Summary Highlights, April 2009-April 2010.” Retrieved May 2020 (https://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/cdcresponse.htm).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. “2009 H1N1 Pandemic.” Retrieved May 2020 (https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/2009-h1n1-pandemic.html).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2022 (https://www.cdc.gov/flu/symptoms/flu-vs-covid19.htm).

- Chamlee-Wright Emily, Storr Virgil Henry. 2011. “Social Capital as Collective Narratives and Post-Disaster Community Recovery.” The Sociological Review 59:266–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang Ying-Chih, Huang Ya-Li, Tseng Kuo-Chien, Yen Chia-Hsin, Yang Lin-hui. 2015. “Social Capital and Health-Protective Behavior Intentions in an Influenza Pandemic.” PLoS ONE 10:e0122970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall Christian S., Schaller Mark. 2005. Social Psychology of Prejudice: Historical and Contemporary Issues. Lawrence, KS: Lewinian Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter Susan L., Ash Kevin D., Emrich Christopher T.2014. “The Geographies of Community Disaster Resilience.” Global Environmental Change 29:65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson Jeremy F., Richter Andreas W.2006. “Probing Three-Way Interactions in Moderated Multiple Regression: Development and Application of a Slope Difference Test.” Journal of Applied Psychology 91:917–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingue Simone J., Emrich Christopher T.2019. “Social Vulnerability and Procedural Equity: Exploring the Distribution of Disaster Aid across Counties in the United States.” The American Review of Public Administration 49:897–913. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim Émile. [1893] 1984. The Division of Labor in Society. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta Sunasir, Rao Hayagreeva. 2015. “Infectious Diseases, Contamination Rumors and Ethnic Violence: Regimental Mutinies in the Bengal Native Army in 1857 India.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 129:36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser Timothy, Aldrich Daniel P., Page-Tan Courtney. 2021. “Bowling alone or distancing together? The role of social capital in excess death rates from COVID19.” Social Science & Medicine 284:114241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frumence Gasto, Emmelin Maria, Eriksson Malin, Kwesigabo Gideon, Killewo Japhet, Moyo Sabrina, Nystrom Lennarth. 2014. “Access to social capital and risk of HIV infection in Bukoba urban district, Kagera region, Tanzania.” Archives of Public Health 72:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gereke Johanna, Schaub Max, Baldassarri Delia. 2018. “Ethnic diversity, poverty and social trust in Germany: Evidence from a behavioral measure of trust.” PLoS One 13:e0199834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen Debby, Lubbers Marcel. 2010. “Unknown Is Unloved? Diversity and Inter-Population Trust in Europe.” European Union Politics 11:267–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gesthuizen Maurice, van der Meer Tom, Scheepers Peer. 2009. “Ethnic Diversity and Social Capital in Europe: Tests of Putnam’s Thesis in European Countries.” Scandinavian Political Studies 32:121–42. [Google Scholar]

- Glanville Jennifer L., Paxton Pamela, Wang Yan. 2016. “Social Capital and Generosity: A Multilevel Analysis.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 45:526–47. [Google Scholar]

- Glanz James, Bloch Mattew, Singhvi Anjali. 2020. “Does My County Have an Epidemic? Estimates Show Hidden Transmission.” The New York Times, April3. Retrieved May 2020 (https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/03/us/coronavirus-county-epidemics.html).

- Gover A. R., Harper S. B., Langton L.2020. “Anti-Asian Hate Crime during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Exploring the Reproduction of Inequality.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 45:647–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve Henrich R., Rao Hayagreeva. 2014. “History and the Present: Institutional Legacies in Communities of Organizations.” Research in Organizational Behavior 34:27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Habyarimana James, Humphreys Macartan, Posner Daniel N., Weinstein Jeremy M.2009. Coethnicity: Diversity and the Dilemmas of Collective Action. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Hasenfeld Yeheskel, Gidron Benjamin. 2005. “Understanding Multi-Purpose Hybrid Voluntary Organizations: The Contributions of Theories on Civil Society, Social Movements and Non-Profit Organizations.” Journal of Civil Society 1:97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hawes Daniel P., McCrea Austin Michael. 2018. “Give Us Your Tired, Your Poor and We Might Buy Them Dinner: Social Capital, Immigration, and Welfare Generosity in the American States.” Political Research Quarterly 71:347–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hawes Daniel P., Rocha Rene R.2011. “Social Capital, Racial Diversity, and Equity: Evaluating the Determinants of Equity in the United States.” Political Research Quarterly 64:924–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins Robert L., Maurer Katherine. 2010. “Bonding, Bridging and Linking: How Social Capital Operated in New Orleans Following Hurricane Katrina.” British Journal of Social Work 40:1777–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hays Richard Allen. 2015. “Neighborhood Networks, Social Capital, and Political Participation: The Relationships Revisited.” Journal of Urban Affairs 37:122–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hero Rodney E.2003. “Social Capital and Racial Inequality in America.” Perspectives on Politics 1:113–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hero Rodney E.2007. Racial Diversity and Social Capital: Equality and Community in America. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyman Michele, McCall Jamie, Paarlberg Laurie, Brennan John. 2016. “Considering the Role of Social Capital for Economic Development Outcomes in US Counties.” Economic Development Quarterly 30:342–57. [Google Scholar]

- Huijts Tim, Kraaykamp Gerbert, Scheepers Peer. 2014. “Ethnic Diversity and Informal Intra- and Inter-Ethnic Contacts with Neighbours in the Netherlands: A Comparison of Natives and Ethnic Minorities.” Acta Sociologica 57:41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Hyunseok, Joo Dongoh. 2021. “How to be resilient? Local philanthropy as a collective response to natural disasters.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 32:430–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Hyunseok, Young Tiffany Amorette. 2020. “How does community philanthropy function?: Direct effects of the social problem and the moderating role of community racial diversity.” The Social Science Journal 57:432–49. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Nikoleta, Sophoulis Costas M., Iosifides Theodoros, Botetzagias Iosif, Evangelinos Konstantinos. 2009. “The Influence of Social Capital on Environmental Policy Instruments.” Environmental Politics 18:595–611. [Google Scholar]

- Kerlin Janelle A., Pollak Tom H.2011. “Nonprofit Commercial Revenue: A Replacement for Declining Government Grants and Private Contributions?” The American Review of Public Administration 4:686–704. [Google Scholar]

- King Brayden. 2008. “A Social Movement Perspective of Stakeholder Collective Action and Influence.” Business & Society 47:21–49. [Google Scholar]

- Klinenberg Eric. 2003. “Review of Heat Wave: Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago.” New England Journal of Medicine 348:666–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyne Dean, Aldrich Daniel P.2020. “Capturing Bonding, Bridging, and Linking Social Capital Through Publicly Available Data.” Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy 11:61–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Young-joo, Hwang Hyunseok. 2020. “Loaded dice: Pandemics and economic inequalities.” International Journal of Policy Studies 11:201–18. [Google Scholar]