This cohort study assesses whether an association exists between psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior in parents and development of the same outcomes in their offspring in a Swedish cohort.

Key Points

Question

Are primary antibody immunodeficiencies (PIDs) in parents associated with an increased risk of their offspring developing psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior?

Findings

In this cohort study of 4 294 169 offspring of parents with and without PIDs, offspring of mothers—but not fathers—with PIDs had an increased risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior. The risk remained after adjusting for parental psychopathology and autoimmune diseases and after excluding offspring with PIDs and autoimmune diseases.

Meaning

This study found that maternal PIDs were associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior in offspring; this finding aligns with a maternal immune activation hypothesis of mental disorders, but the precise mechanisms need to be elucidated.

Abstract

Importance

Maternal immune activation (MIA) leading to altered neurodevelopment in utero is a hypothesized risk factor for psychiatric outcomes in offspring. Primary antibody immunodeficiencies (PIDs) constitute a unique natural experiment to test the MIA hypothesis of mental disorders.

Objective

To assess the association of maternal and paternal PIDs with psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior in offspring.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Cohort study of 4 294 169 offspring of parents with and without PIDs living in Sweden at any time between 1973 and 2013. Data were extracted from Swedish nationwide health and administrative registers and were analyzed from May 5 to September 30, 2022. All individuals with diagnoses of PIDs identified between 1973 and 2013 from the National Patient Register were included. Offspring were included if born before 2003. Parent-offspring pairs in which both parents had a history of PIDs were excluded.

Exposures

Lifetime records of parental PIDs according to the International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision (ICD-8); International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9); and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnostic codes.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Lifetime records of 10 psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior identified using ICD-8, ICD-9, and ICD-10 diagnostic codes, including suicide attempts and death by suicide, among offspring. Covariates included sex, birth year, parental psychopathology, suicide attempts, and autoimmune diseases. Additional analyses excluded offspring with their own PIDs and autoimmune diseases. Poisson regression models were fitted separately for mothers and fathers to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% CIs for the risk of psychiatric and suicidal behavior outcomes in the offspring of PID-exposed vs PID-unexposed mothers or fathers.

Results

The cohort included 4 294 169 offspring (2 207 651 males [51.4%]) and 3 954 937 parents (1 987 972 females [50.3%]). A total of 7270 offspring (0.17%) had parents with PIDs, and 4 286 899 offspring had parents without PIDs. In fully adjusted models, offspring of mothers with PIDs had an increased risk of any psychiatric disorder, while no such risks were observed in offspring of fathers with PIDs (IRR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.10-1.25 vs IRR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.94-1.14; P < .001). Likewise, an increased risk of suicidal behavior was observed among offspring of mothers with PIDs but not offspring of fathers with PIDs (IRR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.06-1.36 vs IRR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.91-1.34; P = .01). For the offspring of mothers with PIDs, the risk of developing any psychiatric disorder was significantly higher for those with mothers with 6 of 10 individual disorders, with IRRs ranging from 1.15 (95% CI, 1.04-1.26) for anxiety and stress-related disorders and 1.15 (95% CI, 1.03-1.30) for substance use disorders to 1.71 (95% CI, 1.37-2.14) for bipolar disorders. Offspring of mothers with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases had the highest risk for any psychiatric disorder (IRR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.11-1.38) and suicidal behavior (IRR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.17-1.78).

Conclusions and Relevance

Findings of this cohort study suggest that maternal, but not paternal, PIDs were associated with a statistically significant increased risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior in the offspring, particularly when PIDs co-occur with autoimmune diseases. These findings align with the MIA hypothesis of mental disorders, but the precise mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

Introduction

The term maternal immune activation (MIA) is used to describe a state of heightened or aberrant maternal immune activity during pregnancy, either through infection or other inflammatory states, which is known from animal studies to have detrimental implications for the offspring’s neurodevelopment in utero.1,2 Preclinical studies1 have reported adverse neurobehavioral, neurophysiological, and neuroanatomical outcomes in offspring secondary to MIA. In humans, growing evidence from observational studies suggests that disruption of the maternal immune system during pregnancy might be associated with an increased risk of psychiatric disorders in the offspring, including autism spectrum disorders,3,4,5 bipolar disorder,6,7 and schizophrenia.6,8,9 Evidence regarding MIA and risk of suicidal behavior (including suicide attempts and death by suicide) is much more limited10,11 and in need of formal investigation. The mechanisms underlying these putative associations are likely complex and multifactorial, encompassing a range of genetic and environmental mechanisms as well as their interaction.1

Primary antibody immunodeficiencies (PIDs) are rare deficiencies of the immune system that are associated with adverse health outcomes, such as recurrent infections, allergies, and autoimmune diseases.12 We have previously shown that individuals with PIDs, particularly women, have an increased risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior, and the association is more pronounced for individuals affected by both PIDs and autoimmune diseases.13 Primary antibody immunodeficiencies affect both sexes, creating a natural experiment that can help assess differential associations of maternal vs paternal PIDs for offspring outcomes. Specifically, while both mothers and fathers share approximately 50% of their segregating genes with their offspring, only mothers share an intrauterine environment with their offspring at a crucial time in neurodevelopment. This fact offers an opportunity to partially separate the implications of genetic and environmental factors of PIDs for the behavioral outcomes of children exposed to these parental conditions.

In this study, we leveraged a uniquely large cohort of individuals with PIDs to assess the association of maternal and paternal PIDS with psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior (suicide attempts and death by suicide) in offspring. Specifically, we hypothesized that the offspring of mothers, but not fathers, with a PID diagnosis would have a higher risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior compared with the offspring of parents without PIDs from the general population.

Methods

This cohort study included all individuals living in Sweden from 1973 through 2013. Study approval was provided by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (reference 2013/862-31/5), which waived the requirement for informed consent because the study was register based, and individuals were not identifiable. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Data Sources

Swedish nationwide health and administrative registers were linked using the unique Swedish national identification number.14 Data on demographic characteristics, migration, and kinship were extracted from the Total Population Register, the Migration Register,15 and the Multi-Generation Register,16 whereas dates and causes of death were collected from the Cause of Death Register.17 Prescribed and dispensed medication data, which were available from July 2005, were extracted from the Prescribed Drug Register.18 From the National Patient Register, information was obtained on diagnoses given in inpatient (from 1964, with nationwide coverage for psychiatric disorders from 1973) and outpatient (since 2001) specialist services.19 All diagnoses were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision (ICD-8; 1969-1986), International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9; 1987-1996), and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10; 1997-present) codes.

Study Population

All individuals with diagnoses of PIDs identified between 1973 and 2013 from the National Patient Register were considered to have PID exposure. Register-based data on exposures, outcomes, and covariates were collected throughout 2013. Each study participant was linked to their biological offspring identified via the Multi-Generation Register. Only singleton offspring were included in the cohort. We excluded from the study cohort those parent-offspring pairs in which both parents had a history of PIDs (6 parents and 6 offspring). Offspring identification was limited to before 2003, to allow for the offspring to reach age 10 years by the end of 2013. Offspring of mothers with PIDs and offspring of fathers with PIDs were compared separately with the offspring of families in which neither the mother nor father had PID exposure.

Variables

Parental PID exposure was defined as a history of any PID diagnosis affecting antibodies recorded in the National Patient Register between 1973 and 2013 (see ICD codes in eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Individuals whose parents had no history of PIDs were considered to be unexposed to PIDs.

A lifetime record of a major psychiatric disorder or a suicide attempt in the National Patient Register (as inpatient or outpatient care) or a record of death by suicide in the Cause of Death Register constituted the outcomes. Psychiatric disorders included 10 individual disorders, namely, obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders, major depression disorder and other mood disorders, anxiety and stress-related disorders, eating disorders, substance use disorders, and Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders (ICD codes are listed in eTable 2 in Supplement 1), and a composite variable for any psychiatric disorder. For suicidal behavior outcomes, we retrieved data on all lifetime records of suicide attempts and all deaths by suicide (ICD codes are provided in eTable 3 in Supplement 1). We also constructed a composite variable for any suicidal behavior. Minimum age limits were applied for identification of outcomes to avoid diagnostic misclassification (eTables 2 and 3 in Supplement 1).

We followed the recommendations for selecting confounders described by VanderWeele.20 Covariates included parental birth year, offspring’s birth year and sex, parental psychopathology, parental suicide attempts and suicide deaths (ICD codes in eTables 2 and 3 in Supplement 1), and parental autoimmune diseases (ICD codes in eTable 4 in Supplement 1).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from May 5 to September 30, 2022. Poisson regression models with robust SEs were fitted separately for mothers and fathers to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% CIs for the risk of psychiatric and suicidal behavior outcomes in the offspring of PID-exposed vs PID-unexposed mothers or fathers. Model 1 was minimally adjusted for parental birth year and offspring sex and birth year, and model 2 was additionally adjusted for parental psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior. Model 3 was fully adjusted and included the adjustments for models 1 and 2 as well as for any parental autoimmune disease.

For a subcohort of individuals born in 1973 or later, the expected cumulative incidence of any psychiatric disorder was estimated for offspring of mothers and fathers with PIDs (separately) using Kaplan-Meier survival estimates (under the assumption of no competing risks). These analyses ensure complete identification of offspring psychiatric outcomes because nationwide coverage for psychiatric disorders was introduced in the National Patient Register in 1973.

To identify any possible cumulative effects, we evaluated if offspring of mothers and fathers who had both PIDs and autoimmune diseases had higher risks than those exposed to either parental PIDs or autoimmune diseases alone compared with mothers and fathers with neither PIDs nor autoimmune diseases. Adjustments were made for parental birth year and offspring sex and birth year and parental psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior.

Sensitivity analyses were performed by repeating the main analysis in 3 separate analyses that excluded offspring with (1) their own record of PIDs, (2) their own record of autoimmune diseases, or (3) their own records of both PIDs and autoimmune diseases. Data management was performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc), and analyses were performed using Stata, version 17.0 (StataCorp, LLC). The threshold for statistical significance was 2-sided P < .05.

Results

The cohort included 4 294 169 offspring (2 086 518 females [48.6%] and 2 207 651 males [51.4%]) and 3 954 937 parents (1 987 972 females [50.3%] and 1 966 965 males [49.7%]). A total of 7270 offspring (0.17%) of parents with PIDs (3738 males [51.4%] and 3532 females [48.6%]) and 4 286 899 offspring of parents without PIDs (2 203 913 males [51.4%] and 2 082 986 females [48.6%]) were identified from the registers. Table 1 reports the descriptive characteristics of the parent and offspring cohorts.

Table 1. Descriptive Characteristics of the Parental and Offspring Cohorts.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | Fathers | Offspring | |||||

| With PIDs (n = 2172) | Without PIDs (n = 1 985 800) | With PIDs (n = 1176) | Without PIDs (n = 1 965 789) | Of mother with PIDs (n = 4676) | Of father with PIDs (n = 2594) | Of parents without PIDs (n = 4 286 899) | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2269 (48.5) | 1263 (48.7) | 2 082 986 (48.6) |

| Male | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2407 (51.5) | 1331 (51.3) | 2 203 913 (51.4) |

| Year of birth | |||||||

| Before 1950 | 1084 (49.9) | 709 978 (35.8) | 623 (53.0) | 839 467 (42.7) | 0 | 0 | 30 (0) |

| 1950-1959 | 518 (23.9) | 506 244 (25.5) | 277 (23.6) | 495 160 (25.2) | 168 (3.6) | 69 (2.7) | 107 072 (2.5) |

| 1960-1969 | 439 (20.2) | 512 933 (25.8) | 217 (18.5) | 465 730 (23.7) | 1225 (26.2) | 530 (20.4) | 738 828 (17.2) |

| 1970-1979 | 125 (5.8) | 241 294 (12.2) | 59 (5.0) | 160 465 (8.2) | 1331 (28.5) | 748 (28.8) | 1 004 768 (23.4) |

| 1980-1989 | 6 (0.3) | 15 351 (0.8) | 0 | 4967 (0.3) | 927 (19.8) | 605 (23.3) | 1 044 135 (24.4) |

| 1990-1999 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 844 (18.1) | 503 (19.4) | 1 101 133 (25.7) |

| 2000-2002 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 181 (3.9) | 139 (5.4) | 290 933 (6.8) |

| PIDsa | NA | NA | NA | NA | 99 (2.1) | 29 (1.1) | 2670 (0.1) |

| Autoimmune diseases | 681 (31.4) | 201 172 (10.1) | 312 (26.5) | 156 740 (8.0) | 396 (8.5) | 189 (7.3) | 245 489 (5.7) |

| Any parental psychiatric disorder | 542 (25.0) | 248 405 (12.5) | 203 (17.3) | 232 145 (11.8) | NA | NA | NA |

| Parental suicide attempts or deaths | 184 (8.5) | 73 648 (3.7) | 52 (4.4) | 72 461 (3.7) | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; PIDs, primary immunodeficiencies.

Data on PIDs reported for offspring (number of individuals with PIDs) correspond to their own records of PIDs.

Main Analyses

Of 4676 offspring of mothers with PIDs, 801 (17.1%) had a record of any psychiatric disorder, whereas 545 224 offspring (12.7%) of mothers without PIDs had a record of any psychiatric disorder, translating into a 17% increased risk for offspring of mothers with PIDs in the fully adjusted model (IRR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.10-1.25) (Table 2). The risk was significantly higher for 6 of 10 groups of psychiatric disorders, namely attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (IRR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.12-1.52), autism spectrum disorders (IRR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.17-1.91), bipolar disorders (IRR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.37-2.14), major depression disorder and other mood disorders (IRR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.11-1.36), anxiety and stress-related disorders (IRR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.04-1.26), and substance use disorders (IRR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.03-1.30) (Table 2). By contrast, among 2594 offspring of fathers with PIDs, no increased risk of any psychiatric disorder (IRR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.94-1.14) was observed compared with offspring of parents without PIDs (eTable 5 in Supplement 1). The only exception was bipolar disorders (IRR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.06-2.11), but analyses were based on a small number of cases and should be interpreted cautiously. A formal test of heterogeneity comparing the IRR for the risk of any psychiatric disorder in offspring of mothers vs fathers was statistically significant (χ2, 25.91; P < .001).

Table 2. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Mothers With and Without PIDs.

| Outcomea | Offspring of mothers, No. (%) | IRR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With PIDs (n = 4676) | Without PIDs (n = 4 286 899) | Model 1b | Model 2c | Model 3d | |

| Any psychiatric disorder | 801 (17.1) | 545 224 (12.7) | 1.33 (1.25-1.42) | 1.19 (1.12-1.27) | 1.17 (1.10-1.25) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 39 (0.8) | 24 136 (0.6) | 1.50 (1.10-2.05) | 1.35 (0.99-1.85) | 1.33 (0.97-1.82) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 150 (3.2) | 106 306 (2.5) | 1.59 (1.36-1.86) | 1.34 (1.15-1.57) | 1.30 (1.12-1.52) |

| Autism spectrum disorders | 62 (1.3) | 39 788 (0.9) | 1.75 (1.37-2.24) | 1.53 (1.20-1.96) | 1.49 (1.17-1.91) |

| Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders | 63 (1.4) | 36 345 (0.9) | 1.33 (1.04-1.70) | 1.15 (0.90-1.47) | 1.15 (0.90-1.47) |

| Bipolar disorders | 77 (1.7) | 31 385 (0.7) | 2.00 (1.60-2.49) | 1.73 (1.39-2.16) | 1.71 (1.37-2.14) |

| Major depression disorder and other mood disorders | 335 (7.2) | 203 516 (4.8) | 1.41 (1.27-1.56) | 1.25 (1.13-1.39) | 1.23 (1.11-1.36) |

| Anxiety and stress-related disorders | 391 (8.4) | 257 885 (6.0) | 1.31 (1.19-1.44) | 1.17 (1.06-1.28) | 1.15 (1.04-1.26) |

| Eating disorders | 42 (0.9) | 32 707 (0.8) | 1.27 (0.94-1.71) | 1.20 (0.89-1.62) | 1.19 (0.88-1.60) |

| Substance use disorders | 257 (5.5) | 163 887 (3.8) | 1.35 (1.20-1.52) | 1.17 (1.04-1.31) | 1.15 (1.03-1.30) |

| Any suicidal behavior | 218 (4.7) | 132 867 (3.1) | 1.39 (1.22-1.58) | 1.21 (1.07-1.38) | 1.20 (1.06-1.36) |

| Suicide attempt | 204 (4.4) | 125 533 (2.9) | 1.39 (1.22-1.59) | 1.22 (1.06-1.39) | 1.20 (1.05-1.37) |

| Death by suicide | 16 (0.3) | 10 573 (0.3) | 1.10 (0.67-1.79) | 0.93 (0.57-1.52) | 0.94 (0.57-1.53) |

Abbreviations: IRR, incidence rate ratio; PIDs, primary immunodeficiencies.

Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders are not reported separately due to underpowered analysis. Total numbers and percentages of specific outcomes may not sum to the combined outcomes as the study participants may have had more than 1 specific outcome.

Adjusted by birth year in parents and offspring and sex in offspring.

Adjusted by birth year in parents and offspring, sex in offspring, and any psychiatric disorder or suicidal behavior in parents.

Adjusted by birth year in parents and offspring, sex in offspring, any psychiatric disorder or suicidal behavior in parents, and any autoimmune disease in parents.

Of 4676 offspring of mothers with PIDs, 218 individuals (4.7%) had a record of any suicidal behavior, whereas 132 867 (3.1%) of offspring of mothers without PIDs had a record of any suicidal behavior, translating into a 20% increased risk in the fully adjusted model (IRR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.06-1.36) (Table 2). By contrast, among 2594 offspring of fathers with PIDs, no increased risk of suicidal behavior (97 [3.7%]; IRR, 1.10; 95% CI, 0.91-1.34) was observed compared with offspring of parents without PIDs (eTable 5 in Supplement 1). A formal test of heterogeneity comparing the IRR for the risk of any suicidal behavior in offspring of mothers vs fathers was statistically significant (χ2, 8.70; P = .013).

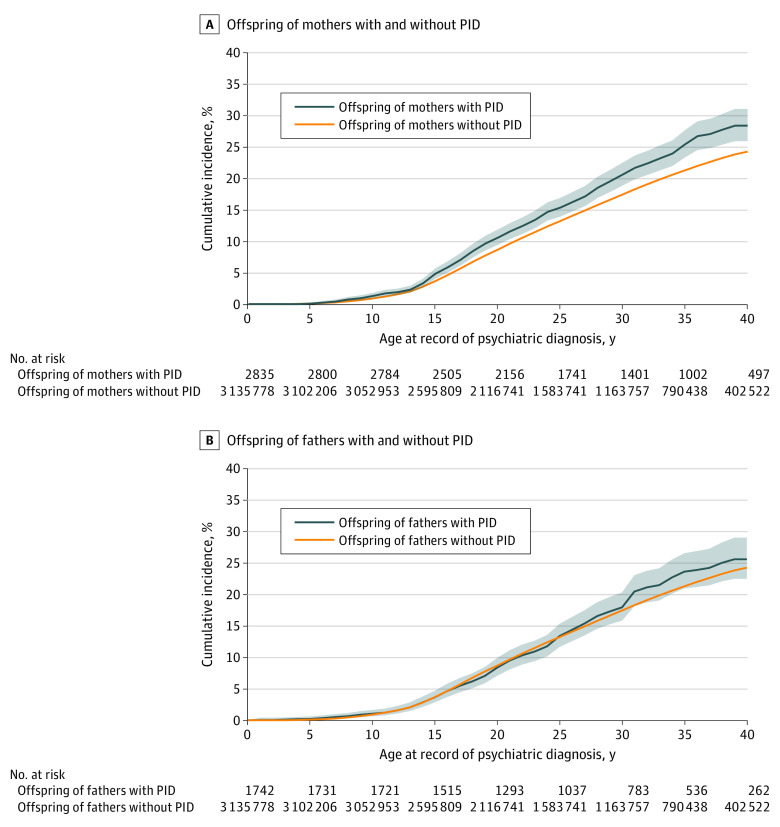

In the subcohort of offspring born in 1973 or later (4577 of 3 138 613 [0.2%] were offspring of parents with PIDs), the Kaplan-Meier expected cumulative incidence of any psychiatric disorder in 2835 offspring of mothers with PIDs at the end of the study was 28.4% (95% CI, 25.9%-31.0%) compared with 24.3% (95% CI, 24.2%-24.4%) in offspring of mothers without PIDs (Figure). This finding corresponds with a fully adjusted IRR of 1.16 (95% CI, 1.07-1.26) (eTable 6 in Supplement 1). By contrast, the cumulative incidence of any psychiatric disorder in the 1742 offspring of affected fathers was comparable to that of fathers without PIDs (25.6%; 95% CI, 22.5%-29.0% vs 24.3%; 95% CI, 24.2%-24.4%), corresponding with a fully adjusted IRR of 1.06 (95% CI, 0.95-1.19) (eTable 7 in Supplement 1).

Figure. Cumulative Incidence of Any Psychiatric Disorder in the Offspring of Mothers or Fathers With Primary Immunodeficiencies (PIDs) vs Offspring of Mothers and Fathers Without PIDs.

The sample is from a subcohort of individuals born in 1973 or later. The shaded areas represent 95% CIs.

Contribution of Autoimmune Diseases

The offspring of mothers with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases had the highest risks of developing any psychiatric disorder (IRR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.11-1.38) and suicidal behavior (IRR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.17-1.78) compared with offspring of mothers with either PIDs or autoimmune diseases alone, although the 95% CIs overlapped (Table 3). The cumulative effect was particularly observed for autism spectrum disorders, bipolar disorders, and suicide attempts (Table 3). By contrast, the offspring of fathers with PIDs alone did not have an increased risk of either psychiatric disorders or suicidal behavior, whereas the offspring of fathers with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases had increased risks only for some of the individual disorders, likely due to the contribution of autoimmune diseases rather than PIDs (eTable 8 in Supplement 1).

Table 3. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Mothers With Only PIDs, Only ADs, or Both.

| Outcomea | Offspring of mothers without PIDs or ADs, No. (%) (n = 3 540 769) | Offspring of mothers with only PIDs | Offspring of mothers with only ADs | Offspring of mothers with both PIDs and ADs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) (n = 2937) | IRR (95% CI)b | No. (%) (n = 746 130) | IRR (95% CI)b | No. (%) (n = 1739) | IRR (95% CI)b | ||

| Any psychiatric disorder | 438 320 (12.4) | 497 (16.94) | 1.19 (1.11-1.29) | 106 904 (14.33) | 1.11 (1.10-1.12) | 304 (17.48) | 1.24 (1.11-1.38) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 19 507 (0.6) | 26 (0.9) | 1.49 (1.04-2.14) | 4629 (0.62) | 1.13 (1.08-1.17) | 13 (0.75) | 1.11 (0.60-2.06) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 86 696 (2.5) | 89 (3.0) | 1.26 (1.03-1.53) | 19 610 (2.63) | 1.19 (1.17-1.21) | 61 (3.51) | 1.62 (1.26-2.08) |

| Autism spectrum disorders | 32 641 (0.9) | 34 (1.2) | 1.34 (0.98-1.85) | 7147 (0.96) | 1.18 (1.15-1.22) | 28 (1.61) | 2.06 (1.40-3.03) |

| Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders | 28 813 (0.8) | 37 (1.3) | 1.10 (0.81-1.49) | 7532 (1.01) | 1.02 (0.99-1.05) | 26 (1.50) | 1.27 (0.84-1.92) |

| Bipolar disorders | 24 844 (0.7) | 43 (1.5) | 1.58 (1.19-2.10) | 6541 (0.88) | 1.10 (1.07-1.14) | 34 (1.96) | 2.11 (1.48-3.01) |

| Major depression disorder and other mood disorders | 161 527 (4.6) | 203 (6.9) | 1.23 (1.08-1.39) | 41 989 (5.63) | 1.13 (1.11-1.14) | 132 (7.59) | 1.37 (1.15-1.63) |

| Anxiety and stress-related disorders | 205 341 (5.8) | 233 (7.9) | 1.15 (1.02-1.29) | 52 544 (7.04) | 1.12 (1.11-1.13) | 158 (9.09) | 1.26 (1.08-1.48) |

| Eating disorders | 26 914 (0.8) | 27 (0.9) | 1.27 (0.89-1.81) | 5793 (0.78) | 1.09 (1.05-1.13) | 15 (0.86) | 1.08 (0.62-1.89) |

| Substance use disorders | 130 863 (3.7) | 163 (5.6) | 1.18 (1.03-1.36) | 33 024 (4.43) | 1.09 (1.07-1.10) | 94 (5.41) | 1.18 (0.96-1.46) |

| Any suicidal behavior | 105 909 (3.0) | 122 (4.2) | 1.13 (0.96-1.33) | 26 958 (3.61) | 1.09 (1.07-1.11) | 96 (5.52) | 1.44 (1.17-1.78) |

| Suicide attempt | 100 130 (2.8) | 116 (4.0) | 1.13 (0.95-1.34) | 25 403 (3.40) | 1.09 (1.08-1.11) | 88 (5.06) | 1.45 (1.17-1.80) |

Abbreviations: ADs, autoimmune diseases; IRR, incidence rate ratio; PIDs, primary immunodeficiencies.

Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders and death by suicide are not reported separately due to underpowered analysis. Total numbers and percentages of specific outcomes may not sum to the combined outcomes as the study participants may have had more than 1 specific outcome.

Adjusted results by birth year in parents and offspring, sex in offspring, and any psychiatric disorder or suicidal behavior in parents.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses were performed after excluding offspring who themselves had a diagnosis of PIDs, autoimmune diseases, or both from the cohort. The results were similar to those in the main analysis (eTables 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

Using PIDs as a model, this study aimed to test the MIA hypothesis of mental disorders and of suicidal behavior in a nationwide cohort in Sweden. Consistent with our a priori hypothesis, the offspring of mothers, but not fathers, with a diagnosis of PIDs had an increased risk of both psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior. Overall, the magnitude of the risk was small (17% increased risk of psychiatric disorders and 20% increased risk of suicidal behavior) but was higher for some individual outcomes such as bipolar disorders (71% increased risk) and autism spectrum disorders (49% increased risk). The observed associations were attenuated but remained statistically significant after controlling for parental psychopathology, parental suicidal behavior, parental autoimmune diseases, and the exclusion of offspring who themselves had PIDs or autoimmune diseases. The latter is relevant because the association between autoimmune diseases and psychiatric disorders21,22,23,24,25 and suicidal behavior26 has been well documented. These findings suggest that maternal PIDs may be a risk factor for the development of a psychiatric condition in offspring, further highlighting the importance of the fetal environment in neurodevelopment. To our knowledge, the association between maternal PIDs, as a model of MIA, and suicidal behavior is a novel finding that contributes to understanding the complex array of risk factors involved in suicide.

A previous study13 reported that individuals with comorbid diagnoses of PIDs and autoimmune diseases have particularly high risks of a range of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior themselves. In the current study, we also found evidence that the offspring of mothers with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases have the highest risks of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior, most notably for autism spectrum disorders, bipolar disorders, and suicide attempts. Together, these findings suggest a dose-response or multiple-hit scenario whereby multiple adverse immune events in utero may cumulatively contribute to the risk of mental disorders and suicidal behavior in the offspring. If replicated, these results call for an increased awareness that the children of mothers with PIDs, and particularly those with PIDs and autoimmune diseases, may be more likely to develop psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior.

While our data cannot pinpoint a precise causal mechanism underlying the observed associations, the results add to the existing literature suggesting that the intrauterine immune environment may have implications for fetal neurodevelopment27 and that a compromised maternal immune system during pregnancy may be a risk factor for psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior in their offspring in the long term.3,4,5,6,7,8,9,23,28,29 One plausible mechanism is that an altered fetal immune environment, secondary to maternal PIDs, may be associated with the creation of reactive antibodies to fetal proteins transferred via the placenta, which can in turn impact neural development.4,30 While genetic contributions to the observed associations cannot be fully ruled out, the lack of significant associations between paternal PIDs and the outcomes of interest suggests that this is a less likely explanation.

Additional environmental factors should also be considered, such as infections during pregnancy, which are common in individuals with PIDs, as well as prenatal maternal stress.31 Interestingly, the hypothesized causal role of infections during pregnancy on offspring psychiatric outcomes has been questioned by a growing number of observational studies,32,33,34,35 suggesting that familial confounding is a more plausible explanation. Mothers are generally more likely than fathers to spend time with their offspring after birth, particularly after a separation or divorce, so disruption of the early life environment (eg, impaired parenting due to recurrent health issues, particularly in mothers who also struggle with their own mental health) could also be a contributing environmental factor affecting the reported associations.36

Strengths and Limitations

This study has strengths, including the uniquely large, population-based sample of individuals with PIDs and their offspring; the use of nationwide Swedish registers with longitudinal and standardized data collection, which minimizes the risk of selection, recall, and report biases; and the strict control of potential confounders.

This study also has limitations, including those inherent to register-based analyses. First, while we had strong hypotheses regarding the specific associations between maternal vs paternal PIDs and the offspring outcomes of interest, we did not have specific hypotheses regarding individual mental disorders and suicidal behavior. Thus, results regarding individual outcomes should be regarded as exploratory and require replication. Second, the date of the record for both exposure and outcomes may not correspond with the actual date of disorder onset. However, because PIDs generally start during childhood, it is reasonable to assume that the exposures preceded the outcomes. Third, the study period may have been insufficient to capture some later-onset disorders, such as schizophrenia. While we could detect a robust signal regarding the composite mental disorders variable, estimates regarding individual disorders should be interpreted with caution. Fourth, the potential contribution to other factors that may affect MIA, such as infections or medication use (eg, antibiotics) during pregnancy, was not explored. However, as mentioned previously, the idea that intrauterine infections play a causal role in offspring psychiatric disorders has been questioned.32,33,34,35 Fifth, other factors that may potentially affect the associations of interest, such as smoking during pregnancy, breastfeeding, skin-to-skin contact at birth, or maternal stress, could not be studied due to data unavailability. Sixth, the National Patient Register only includes records from outpatient specialist care since 2001; the lack of information from primary care physicians may lead to underreporting of mild or moderate PIDs or psychiatric conditions. Finally, the risk of surveillance bias cannot be fully ruled out, as individuals with PIDs are more likely to have contact with health care practitioners, thus increasing the likelihood that their offspring receive psychiatric diagnoses. However, many of our outcomes were sufficiently severe (eg, autism spectrum disorders, psychosis, suicidal behavior) to require medical attention, minimizing the risk of such bias.

Conclusions

The findings of this cohort study suggest that maternal, but not paternal, PIDs are associated with a small but statistically significant increased risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior in offspring, particularly when they co-occur with autoimmune diseases. While the mechanisms are likely multifactorial, the results support the MIA hypothesis as a potential contributor to altered neurodevelopment, psychiatric disorders, and suicidal behavior in offspring.

eTable 1. List of Swedish International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Codes to Collect Records of Primary Antibody Immunodeficiencies From the National Patient Register

eTable 2. List of Swedish International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Codes to Collect records of Psychiatric Disorders From the National Patient Register

eTable 3. List of Swedish International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Codes to Define Suicidal Behavior From the National Patient Register and the Cause of Death Register

eTable 4. List of Swedish International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Codes to Collect Records of Autoimmune Diseases From the National Patient Register

eTable 5. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Fathers With Primary Immunodeficiencies

eTable 6. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Mothers With Primary Immunodeficiencies in a Sub-cohort of Individuals Born in 1973 or Later

eTable 7. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Fathers With Primary Immunodeficiencies in a Sub-cohort of Individuals Born in 1973 or Later

eTable 8. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Fathers With Only Primary Immunodeficiencies, Only Autoimmune Disease, or Both

eTable 9. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Mothers With Primary Immunodeficiencies, Excluding Offspring With Own Record of Primary Immunodeficiency

eTable 10. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Mothers With Primary Immunodeficiencies, Excluding Offspring With Own Record of Autoimmune Disease

eTable 11. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Mothers With Primary Immunodeficiencies, Excluding Offspring With Own Record of Primary Immunodeficiency and Autoimmune Disease

eTable 12. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Fathers With Primary Immunodeficiencies, Excluding Offspring With Own Record of Primary Immunodeficiency

eTable 13. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Fathers With Primary Immunodeficiencies, Excluding Offspring With Own Record of Autoimmune Disease

eTable 14. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Fathers With Primary Immunodeficiencies, Excluding Offspring With Own Record of Primary Immunodeficiency and Autoimmune Disease

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Han VX, Patel S, Jones HF, Dale RC. Maternal immune activation and neuroinflammation in human neurodevelopmental disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(9):564-579. doi: 10.1038/s41582-021-00530-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han VX, Patel S, Jones HF, et al. Maternal acute and chronic inflammation in pregnancy is associated with common neurodevelopmental disorders: a systematic review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):71. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01198-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen SW, Zhong XS, Jiang LN, et al. Maternal autoimmune diseases and the risk of autism spectrum disorders in offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Brain Res. 2016;296:61-69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marks K, Vincent A, Coutinho E. Maternal-autoantibody-related (MAR) autism: identifying neuronal antigens and approaching prospects for intervention. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2564. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lombardo MV, Moon HM, Su J, Palmer TD, Courchesne E, Pramparo T. Maternal immune activation dysregulation of the fetal brain transcriptome and relevance to the pathophysiology of autism spectrum disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(4):1001-1013. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pugliese V, Bruni A, Carbone EA, et al. Maternal stress, prenatal medical illnesses and obstetric complications: risk factors for schizophrenia spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2019;271:23-30. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marangoni C, Hernandez M, Faedda GL. The role of environmental exposures as risk factors for bipolar disorder: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord. 2016;193:165-174. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown AS, Derkits EJ. Prenatal infection and schizophrenia: a review of epidemiologic and translational studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):261-280. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karlsson H, Dalman C. Epidemiological studies of prenatal and childhood infection and schizophrenia. In: Khandaker GM, Meyer U, Jones PB, eds. Neuroinflammation and Schizophrenia: Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Springer International Publishing; 2020:35-47. doi: 10.1007/7854_2018_87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orri M, Gunnell D, Richard-Devantoy S, et al. In-utero and perinatal influences on suicide risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(6):477-492. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30077-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Haddad BJS, Jacobsson B, Chabra S, et al. Long-term risk of neuropsychiatric disease after exposure to infection in utero. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(6):594-602. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballow M. Primary immunodeficiency disorders: antibody deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109(4):581-591. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.122466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isung J, Williams K, Isomura K, et al. Association of primary humoral immunodeficiencies with psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior and the role of autoimmune diseases. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(11):1147-1154. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(11):659-667. doi: 10.1007/s10654-009-9350-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy AKE, et al. Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(2):125-136. doi: 10.1007/s10654-016-0117-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekbom A. The Swedish Multi-generation Register. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;675:215-220. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-423-0_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooke HL, Talbäck M, Hörnblad J, et al. The Swedish cause of death register. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(9):765-773. doi: 10.1007/s10654-017-0316-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wettermark B, Hammar N, Fored CM, et al. The new Swedish Prescribed Drug Register—opportunities for pharmacoepidemiological research and experience from the first six months. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(7):726-735. doi: 10.1002/pds.1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.VanderWeele TJ. Principles of confounder selection. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34(3):211-219. doi: 10.1007/s10654-019-00494-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mataix-Cols D, Frans E, Pérez-Vigil A, et al. A total-population multigenerational family clustering study of autoimmune diseases in obsessive-compulsive disorder and Tourette’s/chronic tic disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(7):1652-1658. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song H, Fang F, Tomasson G, et al. Association of stress-related disorders with subsequent autoimmune disease. JAMA. 2018;319(23):2388-2400. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.7028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He H, Yu Y, Liew Z, et al. Association of maternal autoimmune diseases with risk of mental disorders in offspring in Denmark. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e227503. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.7503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hedman A, Breithaupt L, Hübel C, et al. Bidirectional relationship between eating disorders and autoimmune diseases. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(7):803-812. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellul P, Acquaviva E, Peyre H, et al. Parental autoimmune and autoinflammatory disorders as multiple risk factors for common neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12(1):112. doi: 10.1038/s41398-022-01843-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brundin L, Bryleva EY, Thirtamara Rajamani K. Role of inflammation in suicide: from mechanisms to treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(1):271-283. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics . The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e232-e246. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brander G, Rydell M, Kuja-Halkola R, et al. Association of perinatal risk factors with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a population-based birth cohort, sibling control study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(11):1135-1144. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brander G, Rydell M, Kuja-Halkola R, et al. Perinatal risk factors in Tourette’s and chronic tic disorders: a total population sibling comparison study. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(5):1189-1197. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amaya-Uribe L, Rojas M, Azizi G, Anaya JM, Gershwin ME. Primary immunodeficiency and autoimmunity: a comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2019;99:52-72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2019.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Babineau V, Fonge YN, Miller ES, et al. Associations of maternal prenatal stress and depressive symptoms with childhood neurobehavioral outcomes in the ECHO cohort of the NICHD fetal growth studies: fetal growth velocity as a potential mediator. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;61(9):1155-1167. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2022.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brynge M, Sjöqvist H, Gardner RM, Lee BK, Dalman C, Karlsson H. Maternal infection during pregnancy and likelihood of autism and intellectual disability in children in Sweden: a negative control and sibling comparison cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(10):782-791. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00264-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu CY, Jiang HY, Sun JJ. Maternal infection during pregnancy and the risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the offspring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J Psychiatr. 2022;68:102972. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang T, Brander G, Isung J, et al. Prenatal and early childhood infections and subsequent risk of obsessive-compulsive disorder and tic disorders: a nationwide, sibling-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2022;0(0):S0006-3223(22)01433-0. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2022.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blomström Å, Karlsson H, Gardner R, Jörgensen L, Magnusson C, Dalman C. Associations between maternal infection during pregnancy, childhood infections, and the risk of subsequent psychotic disorder—a Swedish cohort study of nearly 2 million individuals. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(1):125-133. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peshko D, Kulbachinskaya E, Korsunskiy I, et al. Health-related quality of life in children and adults with primary immunodeficiencies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(6):1929-1957.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. List of Swedish International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Codes to Collect Records of Primary Antibody Immunodeficiencies From the National Patient Register

eTable 2. List of Swedish International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Codes to Collect records of Psychiatric Disorders From the National Patient Register

eTable 3. List of Swedish International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Codes to Define Suicidal Behavior From the National Patient Register and the Cause of Death Register

eTable 4. List of Swedish International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Codes to Collect Records of Autoimmune Diseases From the National Patient Register

eTable 5. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Fathers With Primary Immunodeficiencies

eTable 6. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Mothers With Primary Immunodeficiencies in a Sub-cohort of Individuals Born in 1973 or Later

eTable 7. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Fathers With Primary Immunodeficiencies in a Sub-cohort of Individuals Born in 1973 or Later

eTable 8. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Fathers With Only Primary Immunodeficiencies, Only Autoimmune Disease, or Both

eTable 9. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Mothers With Primary Immunodeficiencies, Excluding Offspring With Own Record of Primary Immunodeficiency

eTable 10. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Mothers With Primary Immunodeficiencies, Excluding Offspring With Own Record of Autoimmune Disease

eTable 11. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Mothers With Primary Immunodeficiencies, Excluding Offspring With Own Record of Primary Immunodeficiency and Autoimmune Disease

eTable 12. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Fathers With Primary Immunodeficiencies, Excluding Offspring With Own Record of Primary Immunodeficiency

eTable 13. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Fathers With Primary Immunodeficiencies, Excluding Offspring With Own Record of Autoimmune Disease

eTable 14. Risk of Psychiatric Disorders and Suicidal Behavior in Offspring of Fathers With Primary Immunodeficiencies, Excluding Offspring With Own Record of Primary Immunodeficiency and Autoimmune Disease

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement