Abstract

This cross-sectional study assesses non–self-inflicted firearm-related deaths occurring at inpatient or outpatient facilities, hospice care, nursing homes, home, or other settings from 1999 to 2021.

The increase in firearm death rates in the US has been attributed to many factors, including higher gun sales, social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, and lack of new federal firearm legislation.1 Studies suggest that both the risk and lethality of firearm injuries have increased, partly due to larger magazine capacity and growing use of high-caliber weapons.2,3,4,5 Location of death after traumatic injury informs resource organization for both treatment and prevention. Deaths at the scene of injury serve as a proxy for increasing lethality because those patients do not survive transport to a medical facility; however, locations of firearm deaths remain poorly characterized. In this study, we sought to analyze patterns in location of death from firearm injury in the US between 1999 and 2021.

Methods

We obtained data for firearm deaths due to assaults, unintentional injuries, and unknown intent from the 1999 to 2021 Multiple Cause of Death file of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) WONDER (Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research) database.6 This study used publicly available anonymous data and thus did not meet institutional review board review requirements. We followed the STROBE reporting guideline.

Self-inflicted firearm deaths were excluded because most such deaths occurred at the scene. The primary outcome was location of death, which was defined using CDC categories: inpatient medical facility; outpatient medical facility, including emergency department (ED); death on arrival at medical facility; hospice facility; nursing home or long-term care facility; decedent home; medical facility with unknown status; other place; and unknown. Deaths at other place and decedent home were combined and classified as deaths at the scene.

Linear regression analyses were performed to examine the association between year and percentage of firearm deaths occurring at specific locations. Regression models were run for each location separately. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant. For significant results, annual percent change (APC) was calculated with 95% CI. Analysis was conducted with RStudio 2022.07.01+554 (RStudio Team).

Results

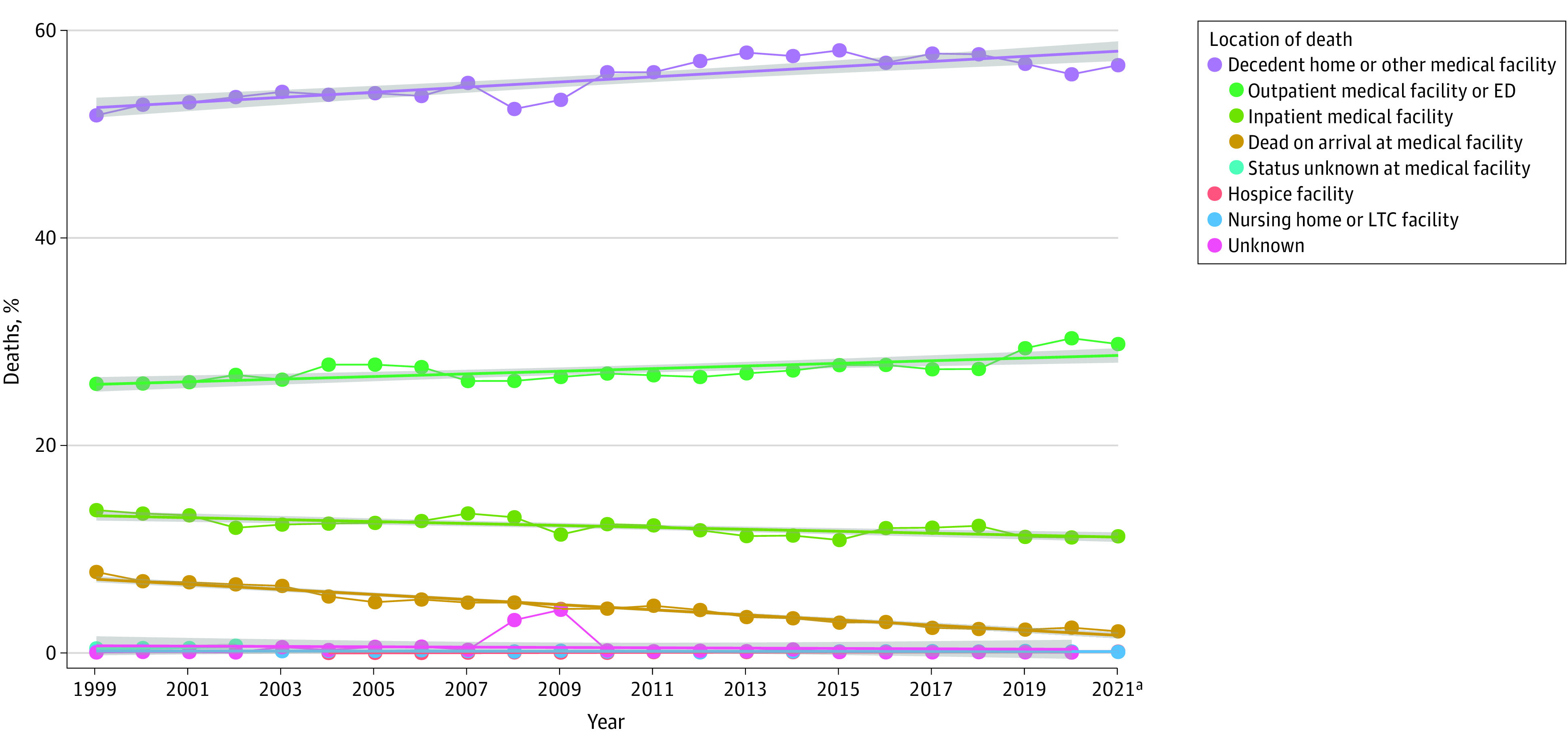

Between 1999 and 2021, 306 772 deaths from non–self-inflicted firearm injury occurred in the US. The proportion of deaths at the scene increased from 51.8% (n = 6036) in 1999 to 56.6% (n = 10 141) in 2021 (Figure). Combined linear regression analyses demonstrated a significant proportional increase in deaths at the scene with each year (mean APC, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.17-0.32; P < .001). The proportion of deaths in the ED increased from 25.9% (n = 3022) in 1999 to 29.9% (n = 5315) in 2021 (mean APC, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.07-0.18; P < .001), while deaths on arrival decreased from 7.8% (n = 910) in 1999 to 1.9% (n = 338) in 2021 (mean APC, −0.25; 95% CI, −0.27 to −0.22; P < .001). Additionally, the proportion of inpatient deaths decreased from 13.8% (n = 1605) to 11.3% (n = 2015) in the same period (mean APC, −0.09; 95% CI, −0.13 to −0.06; P < .001).

Figure. Percentage of Firearm Deaths by Location Between 1999 and 2021.

Locations were hospice, medical facility (ie, death on arrival, inpatient, outpatient or emergency department [ED], and status unknown), nursing home or long-term care (LTC), decedent home, other place, and unknown. Other place and decedent home were combined and classified as deaths at the scene. Circles indicate percentage of deaths, lines indicate linear regression analyses, and shaded areas indicate 95% CIs.

aProvisional mortality statistics were from CDC WONDER.6

Discussion

In the US, there was a significant increase in the proportion of deaths at the scene of firearm injury over the past 20 years. This phenomenon was accompanied by a corresponding decline in the proportion of firearm deaths at inpatient setting, suggesting that the heightened lethality of firearm injury was associated with an increase in deaths among people who never reached a medical facility.

A study limitation was our assumption that death at other place indicated deaths at the scene prior to arriving at a medical facility. Definitions characterizing the differences between death on arrival and death at outpatient facility or ED were unavailable.

Compared with deaths at medical facilities, early deaths from firearm injury increased significantly over the past 2 decades, implying increased injury lethality. Further investigation of the temporal and geospatial distributions of prehospital deaths, weapons used, patterns of injury, and variations by race and ethnicity and age is needed to guide effective interventions.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Houry DE, Simon TR, Crosby AE. Firearm homicide and suicide during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for clinicians and health care systems. JAMA. 2022;327(19):1867-1868. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.6924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tessler RA, Arbabi S, Bulger EM, Mills B, Rivara FP; Trends in firearm injury and motor vehicle crash case fatality by age group 2003-2013. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(4):305-310. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sauaia A, Gonzalez E, Moore HB, Bol K, Moore EE. Fatality and severity of firearm injuries in a Denver trauma center, 2000-2013. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2465-2467. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braga AA, Cook PJ. The association of firearm caliber with likelihood of death from gunshot injury in criminal assaults. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(3):e180833. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.George J. Shoot to kill: why Baltimore is one of the most lethal cities in the U.S. The Baltimore Sun. September 30, 2016. Accessed January 31, 2023. https://data.baltimoresun.com/news/shoot-to-kill/

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Multiple Cause of Death, 1999-2020. CDC WONDER Online Databases. Accessed January 31, 2023. https://wonder.cdc.gov/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Sharing Statement