Abstract

Patients with psoriasis have a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors. This study evaluated cardio-vascular screening practices and statin prescribing habits among dermatologists, rheumatologists and primary care physicians (PCPs) through an online questionnaire, which was distributed through the Spanish scientific societies of the above-mentioned specialties. A total of 299 physicians (103 dermatologists, 94 rheumatologists and 102 PCPs) responded to the questionnaire. Of these, 74.6% reported screening for smoking, 37.8% for hypertension, 80.3% for dyslipidaemia, and 79.6% for diabetes mellitus. Notably, only 28.4% performed global screening, defined as screening for smoking, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and diabetes mellitus by the same physician, and 24.4% reported calculating 10-year cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, probably reflecting a lack of comprehensive cardiovascular risk assessment in these patients. This study also identified unmet needs for awareness of cardiovascular comorbidities in psoriasis and corresponding screening and treatment recommendations among PCPs. Of PCPs, 61.2% reported not being aware of the association between psoriasis and CVD and/or not being aware of its screening recommendations, and 67.6% did not consider psoriasis as a risk-enhancing factor when deciding on statin prescription. Thirteen dermatologists (12.6%) and 35 rheumatologists (37.2%) reported prescribing statins. Among those who do not prescribe, 49.7% would be willing to start their prescription.

SIGNIFICANCE

Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk of cardiovascular events. This is partly due to a higher prevalence of smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidaemia. This study found that less than 30% of the physicians evaluated (dermatologists, rheumatologists and primary care physicians) performed global screening, defined as screening for hypertension, dyslipidaemia, smoking and diabetes mellitus by the same physician. In addition, more than 60% of the primary care physicians stated that they were unaware of the association between psoriasis and cardiovascular disease. Regarding treatment, 50% of dermatologists and rheumatologists who do not prescribe statins would be willing to start prescribing them.

Key words: cardiovascular disease, diagnosis, hearth disease risk factor, psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated skin disease, which is associated with accelerated atherosclerosis (1, 2) and an increased risk of major cardiovascular events (3–6). Myocardial infarction occurs, on average, 5 years earlier in people with psoriasis than in the general population (7). This elevated cardiovascular risk could be driven by both systemic inflammation in moderate-to-severe forms of the disease (8–10) and a higher prevalence of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF), such as obesity, smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, metabolic syndrome or sedentary lifestyle (11–14). Interestingly, disease severity is associated with an increased likelihood of having CVRFs (15, 16), and with poorer control of hypertension in a dose-dependent manner (17). Primary care-based and dermatologist-based screening studies have shown that CVRFs are underdiagnosed in these patients, with 27.5–48% of patients with psoriasis having at least 1 undetected CVRF (18, 19). Moreover, an international cross-sectional study that included 2,254 patients with psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis found that 65.6% of those with dyslipidaemia were not adequately treated with statins (20).

On this basis, a European working group and the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF)/American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) have independently developed position statements for the diagnosis and treatment of psoriasis comorbidities, including CVRFs screening recommendations (21, 22). Both documents recommend following national guidelines, considering earlier and more frequent assessment in those patients with moderate-to-severe forms of the disease. The most followed guidelines for primary cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention are those from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) (23, 24), which recommend a global approach based on the estimation of 10-year CVD risk with different scores, rather than an approximation based on individual CVRFs. These scores are easily calculated through free online or mobile applications in which demographic information, smoking status, blood pressure, cholesterol values and diabetes mellitus status must be entered. Statins are usually indicated when blood cholesterol levels are above treatment goals, which are defined according to 10-year risk of CVD. Psoriasis is not quantitatively included in these tools, but it is considered as a risk-enhancing factor that can tip the balance towards more proactive treatment in borderline cases (23).

Despite the screening recommendations for comorbidities in patients with psoriasis, the extent to which these guidelines are implemented in clinical practice is unclear, and which specialist should assume the burden of this CVD prevention remains controversial. Although a primary care-based management of CVRFs is recommended, screening measures are usually shared by both specialists and primary care physicians (PCP), and NPF/AAD guidelines open the door to hypertension and dyslipidaemia treatment by the dermatologists (21).

The principal aim of this study was to evaluate screening practices among dermatologists, rheumatologists and PCPs regarding CVRFs, especially focusing on a global approach through calculation of 10-year risk of CVD. This study also examined statin prescribing habits among the above-mentioned specialties, exploring whether dermatologists and rheumatologists viewed statin prescription feasible.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study setting and instrument

From September 2021 to February 2022, an online questionnaire was distributed via e-mail to dermatologists from the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) and from the Spanish Group of Psoriasis (GPS), to rheumatologists from the Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER) and to PCPs from the Spanish Society of Primary Care Physicians (SEMERGEN). Each of the above-mentioned societies sent the survey to all their members via their institutional e-mail list. The Institutional Review Board of the Hospital Universitario Ramon y Cajal considered that the study protocol was exempt from review given its design.

Survey questions were developed and reviewed by an expert panel of clinicians (EBR, AGC, ABM, IGD, JMG) and a survey methodology expert (CAR). Questions included: demographic data, degree of training and specialization, CVRF screening habits and factors that could affect the screening ratio. Questions related to statin prescription habits were included in the dermatologists’ and rheumatologists’ questionnaires. For PCPs, a final question was included, assessing whether they consider psoriasis as a risk-enhancing factor when prescribing statins.

Questions were designed according to recommendations from the most relevant CVD primary prevention guidelines (23, 24), guidelines for the diagnosis and management of individual CVRFs (25–30) and position statements for the management of comorbidities in psoriasis (21, 22). Table SI summarizes baseline screening recommendations and their periodicity for each CVRF.

The questionnaire is provided in Appendix S1.

The study followed the relevant portions of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline (31) and the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) reporting guideline (32).

Outcomes and study covariates

The primary outcome of this study was to evaluate the screening rates of smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes mellitus among dermatologists, rheumatologists and PCPs in patients with psoriasis. Global screening (GS) was defined as screening for smoking, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes mellitus by the same physician, since these are the 4 CVRFs needed to estimate 10-year CVD risk. This study also assessed if the 10-year CVD risk estimation via the SCORE Risk Charts or the Pooled Cohort ASCVD Risk Equation was calculated in these patients.

Secondary outcomes were: (i) to compare screening rates among the above-mentioned specialties; (ii) to identify factors associated with a higher or lower frequency of screening; and (iii) to explore statin prescribing habits among dermatologists and rheumatologists and factors that could help their implementation.

Statistical analysis

In the descriptive analysis, categorical variables were described using absolute frequencies and percentages. Exact 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were provided for selected parameters.

Univariable logistic regression was used to evaluate differences in screening rates between dermatologists, rheumatologists and PCPs. A multivariable logistic regression model was built to identify predictors (independent variables) of GS, 10-year CVD risk calculation and statin prescription. Medical specialty, sex, practice setting (public, private or both), years since completing residency training, number of patients with psoriasis treated per month, participation in a specialized psoriasis outpatient clinic, participation in research projects related to psoriasis and university teaching were evaluated. As a first step, a univariable logistic regression was performed between each of the aforementioned variables and the dependent variables GS, 10-year CVD risk calculation and statin prescription. Variables with p < 0.20 were included in the multivariable model (33). Variables with p > 0.20, but which were identified as potential confounders, were also included. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses. Statistical analyses were completed using SPSS v.25.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

A total of 103 out of 1,930 dermatologists (response rate 5.3%), 94 out of 1,879 rheumatologists (response rate 5.0%) and 102 out of 412 PCPs surveyed (response rate 24.8%) responded to the questionnaire. Table I shows the baseline characteristics of the participants. Baseline characteristics of dermatologists and rheumatologists were similar in terms of sex, percentage of fellows and private practice to those of the AEDV and SER members, respectively (Tables SII and SIII).

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the respondents

| Dermatologists (n=103) | Rheumatologists (n=94) | PCPs (n=102) | Total (n=299) | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 65 (63.1) | 63 (67.0) | 61 (59.8) | 189 (63.2) | 0.467 |

| Practice setting, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Public hospital/clinic | 43 (41.7) | 72 (76.6) | 96 (94.1) | 212 (70.9) | |

| Private hospital/clinic | 18 (17.5) | 9 (9.6) | 4 (3.9) | 30 (10.0) | |

| Both | 42 (40.8) | 12 (12.8) | 2 (2.0) | 56 (18.8) | |

| Years since completing residency training, n (%) | 0.621 | ||||

| Fellow | 9 (8.7) | 3 (3.2) | 10 (9.8) | 22 (7.4) | |

| 1–10 | 25 (24.3) | 29 (30.9) | 21 (20.6) | 75 (25.3) | |

| 11–20 | 24 (23.3) | 22 (23.4) | 20 (19.6) | 66 (22.2) | |

| 21–30 | 27 (26.2) | 22 (23.4) | 29 (28.4) | 78 (26.3) | |

| > 30 | 17 (16.5) | 17 (18.1) | 22 (21.6) | 56 (18.9) | |

| Psoriasis patients treated per month, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 5 | 7 (6.8) | 4 (4.3) | 62 (60.8) | 73 (24.4) | |

| 5–20 | 32 (31.1) | 46 (48.9) | 40 (39.2) | 118 (39.5) | |

| > 20 | 64 (62.1) | 44 (46.8) | 0 (0) | 108 (36.1) | |

| Specialization, n (%) | |||||

| Specialized psoriasis outpatient clinic | 41 (39.8) | 8 (8.5) | 2 (2.0) | 41 (17.3) | < 0.001 |

| Research projects | 47 (45.6) | 30 (30.5) | 0 (0) | 77 (26.1) | < 0.001 |

| University teaching | 25 (24.3) | 17 (18.1) | 1 (1) | 43 (14.6) | < 0.001 |

PCPs: primary care physician.

χ2 test.

Screening practices for cardiovascular risk factors

Overall, 223 physicians (74.6%, 95% CI 69.9–79.8) reported screening for smoking, 136 (45.5%, 95% CI 39.8–51.2) for obesity, 113 (37.8%, 95% CI 32.3–43.3) for hypertension, 240 (80.3%, 95% CI 75.7–84.8) for dyslipidaemia and 238 (79.6%, 95% CI 75.0–84.2) for diabetes mellitus. Eighty-five physicians (28.4%, 95% CI 23.3–33.6) performed GS and 73 physicians (24.4%, 95% CI 19.5–29.3) reported calculating 10-year CVD risk. Table II summarizes the screening rates for each cardiovascular risk factor among dermatologists, rheumatologists and PCPs and the univariable comparative analysis.

Table II.

Screening practices among the specialists evaluated with univariable logistic regression results

| Dermatologists (n=103) | Rheumatologists (n=94) | PCPs (n=102) | Total (n=299) | ORγ (95% CI) *D vs R; **D vs PCPs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking, n (%) | 81 (78.6 | 86 (91.5) | 56 (54.9) | 223 (74.6) | *OR 0.34 (0.14–0.81) **OR 3.02 (1.64–5.58) |

| Obesity, n (%) | 56 (54.4) | 47 (50.0) | 33 (32.4) | 136 (45.5) | *OR 1.19 (0.68–2.09) **OR 2.49 (1.41–4.40) |

| HTN, n (%) | 22 (21.4) | 34 (36.2) | 57 (55.9 | 113 (37.8) | *OR 0.48 (0.26–0.902) **OR 0.21 (0.12–0.40) |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 80 (77.7) | 92 (97.9) | 68 (66.7) | 240 (80.3) | *OR 0.08 (0.02–0.33) **OR 1.74 (0.94–3.23) |

| DM, n (%) | 77 (74.8) | 87 (92.6) | 74 (72.6) | 238 (79.6) | *OR 0.24 (0.01–0.58) **OR 1.12 (0.60–2.09) |

| Global screening, n (%) | 21 (20.6) | 29 (30.9) | 35 (34.3) | 85 (28.4) | *OR 0.57 (0.3–1.1) **OR 0.49 (0.26–0.92) |

| 10-year cardiovascular risk calculation, n (%) | 12 (11.7) | 12 (12.8) | 49 (48.0) | 73 (24.4) | *OR 0.90 (0.38–2.12) **OR 0.14 (0.07–0.29) |

D: dermatologists; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; DM: diabetes mellitus; HTN: hypertension; OR: odds ratio; PCP: primary care physician; R: rheumatologists; γ: univariable logistic regression.

On multivariable analysis (Table III), dermatologists were less likely to perform GS compared with rheumatologists (OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.15–0.74, p = 0.007) and PCPs (OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.05–0.38, p < 0.001); they were also less likely than PCPs to calculate 10-year CVD risk (OR 0.05, 95% CI 0.02–0.20, p < 0.001).

Table III.

Multivariable regression models for global screening and 10-year CVD risk calculation

| Global screening* | 10-year CVD risk calculation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORa | 95% CIa | p-value | ORa | 95% CIa | p-value | |

| Specialty | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||

| Dermatologists vs rheumatologists | 0.33 | 0.15–0.74 | 0.007 | 0.53 | 0.18–1.54 | 0.241 |

| Dermatologists vs PCPs | 0.14 | 0.05–0.38 | < 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.02–0.20 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men vs women | 0.53 | 0.28–0.97 | 0.040 | — | — | — |

| Practice setting | 0.533 | |||||

| Private vs public | — | — | — | 2.01 | 0.59–6.91 | 0.266 |

| Private + public vs only public | — | — | — | 1.22 | 0.43–3.45 | 0.704 |

| Years of experience | 0.027 | 0.047 | ||||

| 1–10 years vs resident | 0.52 | 0.15–1.80 | 0.304 | 0.68 | 0.20–2.29 | 0.534 |

| 10–20 years vs resident | 0.46 | 0.13–1.66 | 0.235 | 0.28 | 0.08–1.03 | 0.056 |

| 20–30 years vs resident | 1.44 | 0.43–4.78 | 0.552 | 0.92 | 0.27–3.14 | 0.898 |

| > 20 years vs resident | 1.24 | 0.37–4.14 | 0.732 | 0.35 | 0.10–1.27 | 0.111 |

| Patients with psoriasis treated per month | 0.426 | 0.662 | ||||

| 5–20 vs < 5 | 1.71 | 0.76–3.83 | 0.193 | 0.72 | 0.33–1.57 | 0.406 |

| > 20 vs < 5 | 1.75 | 0.57–5.42 | 0.33 | 0.60 | 1.61–2.22 | 0.442 |

| Specialized psoriasis outpatient clinic | ||||||

| Yes vs no | 2.59 | 1.01–6.69 | 0.049 | 1.95 | 0.61–6.25 | 0.264 |

| Research projects related to psoriasis | ||||||

| Yes vs no | 2.32 | 1.03–5.24 | 0.044 | 3.30 | 1.17–9.34 | 0.024 |

| University teaching including psoriasis | ||||||

| Yes vs no | 1.50 | 0.65–3.48 | 0.344 | 1.47 | 0.51–4.23 | 0.475 |

Variables with no value in any of the columns are those with a p-value > 0.20 in a first univariable logistic regression and which were not identified as potential confounders, as detailed in methods.

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; CVD: cardiovascular disease; OR: odds ratio; PCP: primary care physician.

Defined as screening for smoking, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes mellitus by the same physician.

Among those who do not perform GS, 42 dermatologists (51.2%) and 32 rheumatologists (49.2%) reported referring the patient to a PCP and/or cardiologist (OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.57–2.08, p = 0.811).

Predictors and factors reported as stimuli or obstacles for cardiovascular risk factors screening

Among physician characteristics, the participation in a specialized psoriasis outpatient clinic was independently associated with an increased likelihood of performing GS (OR 2.59, 95% CI 1.01–6.69, p = 0.049). Participation in research projects related to psoriasis was independently associated with an increased likelihood of both GS (OR 2.32, 95% CI 1.03–5.24, p = 0.044) and 10-year CVD risk (OR 3.30, 95% CI 1.17–9.34, p = 0.024). Male physicians were less likely to perform GS than females (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.28–0.97, p = 0.040). The adjusted values for each predictor of GS and 10-year CVD risk calculation in multivariable analysis are detailed in Table III.

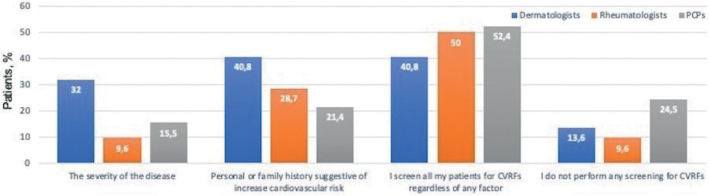

When asked about factors that prompt physicians to screen for CVRFs in psoriasis (more than 1 answer was possible), 33 dermatologists (32.0%), 9 rheumatologists (9.6%) and 16 PCPs (15.5%) answered the severity of the disease, whereas 40 dermatologists (40.8%), 27 rheumatologists (28.7%) and 22 PCPs (21.4%) answered a personal or family history suggestive of increased cardiovascular risk.

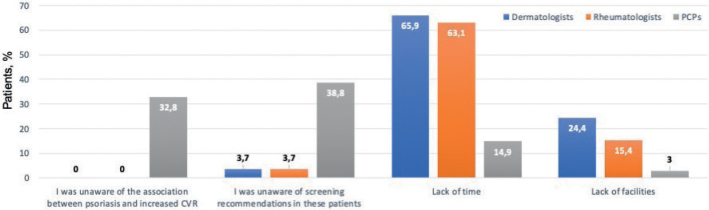

Regarding the reasons for not screening for CVRFs (more than 1 answer was possible), the most frequent response among those who did not perform GS was lack of time, reported by 105 physicians (65.9% of dermatologists, 63.1% of rheumatologist and 14.9% of PCPs, p < 0.001). Interestingly, unawareness of the association between psoriasis and increased CVR and unawareness of screening recommendations in psoriasis patients were answered essentially by PCPs (0.0% of dermatologists, 0.0% of rheumatologists and 32.8% of PCPs, p < 0.001, and 3.7% of dermatologists, 4.6% of rheumatologists and 38.8% of PCPs, p < 0,001, respectively). Figs 1 and 2 summarize the reasons reported.

Fig. 1.

Factors that prompt cardiovascular risk factor (CVRF) screening. Bars indicate percentage of physicians within each specialty that marked every option. PCP: primary care physician.

Fig. 2.

Reasons for not screening for cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs). Bars indicate percentage of physicians within each specialty that marked every option. PCP: primary care physician.

Statin prescription

When PCPs were asked whether they considered psoriasis as a risk-enhancing factor when prescribing statins, 69 physicians (67.6%) answered that they did not.

Thirteen dermatologists (12.6%, 95% CI 6.1–19.1) and 35 rheumatologists (37.2%, 95% CI 27.3–47.2) reported statin prescription according to ESC/AHA guidelines. The difference was significant (OR 0.04, 95% CI 0.01–0.16, p < 0.001) after adjustment for years since completing residence, number of psoriasis patients seen per month, participation in a specialized psoriasis outpatient clinic, participation in research projects related to psoriasis and university teaching including psoriasis lectures (Table SIV).

Those who do not routinely prescribe statins were asked if they would be willing to start prescribing them. Forty-seven out of 90 dermatologists (52.2%) and 27/59 rheumatologists (45.8%) would start prescribing statins.

Table IV summarizes the statin prescription habits and the reasons for initiating or not initiating their prescription among dermatologists and rheumatologists.

Table IV.

Statin prescription habits and predisposition to start prescribing them

| Dermatologists (n = 103) | Rheumatologists (n = 94) | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current prescription of statins, n (%) | 13 (12.6) | 35 (37.2) |

*OR 0.24 (0.12–0.50) **OR 0.04 (0.01–0.16) |

| Would you be willing to start prescribing statins?a | |||

| Yes (%) | 47 (52.2) | 27 (45.8) | |

| I would start prescribing after attending specific training courses for dermatologists or rheumatologists | 43 (91.5) | 27 (100) | |

| Others motivesb | 4 (8.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No (%) | 43 (47.8) | 32 (54.2) | |

| This exceeds the role of a dermatologists | 15 (35.0) | 9 (28.1) | |

| I do not have enough time to determine the need for statins | 23 (53.5) | 19 (59.4) | |

| I do not have the necessary material means to determine the need for statins | 14 (32.6) | 4 (12.5) | |

More than 1 answer was possible.

Respondents could provide free text: “I would prescribe if the prescription of statins was included in protocols developed for dermatologists” was answered by 1 dermatologist and “Clearer criteria for prescribing statins” by another. Two respondents marked the free-text option, but did not provide any text.

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Univariable logistic regression;

multivariable logistic regression, adjusted for years since completing residence, number of psoriasis patients seen per month, participation in a specialized psoriasis outpatient clinic, participation in research project related with psoriasis and university teaching including psoriasis lessons.

DISCUSSION

The most relevant findings of this survey study are: (i) a comprehensive approach to cardiovascular risk in patients with psoriasis is apparently lacking. Overall, only 28.4% of the specialists surveyed performed GS, and 24.4% reported calculating 10-year CVD risk. (ii) PCPs were insufficiently aware of the increased cardiovascular risk experienced by patients with psoriasis and the implications that this entity has on CVRFs screening and management. The fact that almost 70% of them did not consider psoriasis as a risk-enhancing factor when deciding on statin prescription is noteworthy. (iii) Dermatologists and rheumatologists reported a high predisposition to start prescribing statins.

Parsi et al. (34) studied the cardiovascular screening practices in patients with psoriasis among PCPs and cardiologists launching a questionnaire based on 2008 NPF and American Journal of Cardiology recommendations. Manalo et al. (35) explored the same topic among dermatologists. Both studies showed less than half of the above-mentioned specialists screened for hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes mellitus according to guidelines. In this regard, 2 studies analyse data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), a cross-sectional ongoing survey of non- federally employed, office-based physician practices in the USA. Blood pressure values were included in 32.2–36.4% of psoriasis outpatient visits, glucose levels in 4.9–5.9%, cholesterol levels in 9–9.2% and body mass index (BMI) values in 26–29.9% (36, 37). In the current study, although hypertension was screened by only 21.4% of dermatologists, 36.2% of rheumatologists and 55.9% of PCPs, screening rates for dyslipidaemia (80.3%) and diabetes mellitus (79.6%) were higher compared with those previously reported, especially among dermatologists and rheumatologists. Screening rates for smoking were also acceptable (74.6%).

The gap between elevated screening rates for most CVRFs included in 10-year CVD risk scores and low frequency of GS could indicate a fractional approach to cardiovascular risk assessment in these patients and the absence of a strategy that integrates all aspects of their cardiometabolic map. It is essential to identify the barriers behind these gaps, since the absence of a comprehensive cardiovascular approach could preclude not only the correct assessment of these patients, but also their adequate management. Serum lipid profile and blood glucose determinations are easily ordered and integrated in blood tests that dermatologists and rheumatologists usually request before starting systemic medication or in their controls. However, blood pressure measurement is time-consuming and requires specific (albeit cheap and accessible) equipment. In this regard, lack of time and lack of facilities were the reasons for not screening most commonly reported among dermatologists and rheumatologists. Interestingly, the GS rate among these specialists is twice the rate of 10-year CVD risk calculation. Therefore, there appear to be dermatologists and rheumatologists who are collecting all the required information, but who are not calculating the scores, even though this can be done through free, fast and easy-to-use apps (ESC CVD Risk Calculation App® or ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus®) or web pages (38, 39). A lack of confidence in these prediction systems could be behind this discrepancy. Several studies have pointed out that they may underestimate the actual CVD risk in patients with chronic inflammatory states such as psoriasis, especially in moderate-to-severe forms of the disease (40, 41). However, clinical practice guidelines still consider the calculation of 10-year CVD risk as the basis for preventive measures, considering psoriasis as a risk-enhancing factor that may guide primary preventive measures in intermediate risk patient (23, 24). Lack of familiarity with CVD prediction systems, usually outside the scope of practice of dermatologists and rheumatologists, could also contribute to this gap.

Conversely, blood pressure measurement and calculation of 10-year CVD risk scores are integrated in routine workup performed by PCPs. This may explain a higher rate of that variable, despite the fact that screening for most individual CVRFs was less frequent among PCPs than among dermatologists and rheumatologists. However, the reported rate of 10-year CVD risk calculation was still less than 50%. In this regard, 61.2% of PCPs reported not being aware of the association between psoriasis and increased cardiovascular risk and/or not being aware of its screening recommendations, and 67.7% of them did not consider the presence of psoriasis when deciding on statin prescription, despite ESC and AHA guideline recommendation (23, 24). This is especially relevant considering that patients with psoriasis are nowadays referred to their PCPs for screening and management of CVRFs.

The severity of the disease may influence the screening rates among different specialists. Patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis have a higher risk of cardiovascular events, and may also be more involved with dermatologists and rheumatologists. However, the questionnaire asked about factors that prompt screening, and less than 30% of the specialists surveyed answered the severity of the disease. This could reflect the lack of clear recommendations from clinical practice guidelines. The AAD/NPF guidelines recommends earlier and more frequent screening for CVRFs in patients with moderate-to-severe forms of the disease, but without providing concrete ages of onset or intervals (21). In the coming years, more studies and clearer positions may be needed to define the best screening strategy in this particularly high-risk subgroup of patients.

The strategy chosen to try to improve cardiovascular outcomes of patients with psoriasis should be adapted according to available resources and the structure of each healthcare system. In the US, 16.9% of women and 21.6% of men with psoriasis had no encounters with a PCP in the year following their first visit to a dermatologist (42), whereas in Spain psoriatic patients seem to be more engaged with their PCPs, with a mean of 8.7 visits per year (43). Barbieri et al. (44) explore dermatologists’ perspectives on a specialist-led model of cardiovascular screening and management. More than two-thirds of dermatologists (69.3%) agreed that screening for CVRFs was doable, and 36.1% considered that prescribing statins was feasible. To facilitate the lipid management in specialty care clinics, they propose the use of a care coordinator. The specialists measure or identify individual CVRFs and the care coordinators review test results and other sociodemographic information to calculate 10-year CVD risk score. Finally, a protocolized clinician decision support system would help them to determine whether statin therapy or blood pressure management are indicated. The current study also shows that, although current prescription rates of statins by dermatologists and rheumatologists were low, nearly 50% of those who did not prescribe statins would be willing to start prescribing them after attending specific training courses. However, PCPs have greater expertise in the management of statins and antihypertensives and can offer a more comprehensive view of the patient. Allocating more resources to training PCPs in the cardiovascular comorbidities of psoriasis could be a more reasonable and efficient measure in settings where patients with psoriasis are properly engaged with them, always ensuring good communication with hospital specialists.

Study limitations

Limitations of the study should be considered in the context of its design. Response and sampling bias are both inherent to questionnaire-based studies. To mitigate the sampling bias, the online survey was distributed through national email lists; hence we could assume a wide geographical distribution of the questionnaire. Although the response rate among PCPs was acceptable, the low response rate among dermatologists and rheumatologists severely limits our ability to generalize the results. The response rate among dermatologists in the study by Barbieri et al. was, surprisingly, very similar (5.2%) to that of the current study, with considerably fewer responses from rheumatologists (42). Both survey respondents and members of the AEDV and SER showed relatively similar demographic characteristics in terms of sex, private practice and percentage of fellows, which would support that the respondents might adequately represent the population from which they were sampled. Parsi et al. (34) reported a response rate of 21% among PCPs and cardiologists, similar to that observed among PCPs in the current study. Cardiologists were not asked, as they are more involved in the treatment of established cardiovascular diseases than in screening practices in our setting. Finally, a considerable proportion of dermatologists and rheumatologists who responded to the questionnaire came from an academic setting. They may be more likely to be aware of new scientific publications and to consider the patient’s comorbidities compared with their colleagues, which may bias these results. Actual screening rates could therefore be lower than reported.

Conclusion

The deficit of a comprehensive approach to cardiovascular risk in patients with psoriasis highlighted by the current study could hinder the adequate treatment of their modifiable CVRFs, which is of utmost importance given their increased risk of CVD. Obstacles behind the screening difficulties for each specialist need to be identified. PCPs showed considerable rates of unawareness of the link between psoriasis and CVD and the corresponding screening and treatment recommendations. Allocating more resources to training PCPs in psoriasis comorbidities seems a reasonable measure if we want to increase their involvement in the management of the cardiovascular comorbidities of these patients. In scenarios where PCP-based CVRFs management strategies are ineffective, specialist-based models could be considered in light of their high predisposition to prescribe statins.

Supplementary Material

Cardiovascular Screening Practices and Statin Prescription Habits in Patients with Psoriasis among Dermatologists, Rheumatologists and Primary Care Physicians

Cardiovascular Screening Practices and Statin Prescription Habits in Patients with Psoriasis among Dermatologists, Rheumatologists and Primary Care Physicians

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr Ignacio Garcia Doval for his invaluable help in preparing the survey; the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) and its Psoriasis Working Group (GPS), the Spanish Society of Rheumatology (SER) and the Spanish Society of Primary Care Physicians (SEMERGEN) for enabling us to distribute the survey among their members; and to all colleagues who answered the questionnaire.

IRB approval status

This study was deemed exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board of Hospital Universitario Ramon y Cajal.

Conflicts of interest

PdlC received consultancy/speaker’s honoraria from and/or participated in clinical trials sponsored by Abbvie, Almirall, Astellas, Biogen, Boehringer, Celgene, Janssen., LEO Pharma, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi and UCB, not related with the submitted work. LP received consultancy/speaker’s honoraria from and/or participated in clinical trials sponsored by Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Leo-Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz, Sanofi, and UCB. NNM is a full-time US government employee and has served as a consultant for Amgen, Eli Lilly, and Leo Pharma, receiving grants/other payments; as a principal investigator and/or investigator for AbbVie, Celgene, AstraZeneca, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Novartis, and Abcentra, receiving grants and/or research funding; and as a principal investigator for the NIH, receiving grants and/or research funding. JMG served as a consultant for Abbvie, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celldex (DSMB), FIDE (which is sponsored by multiple pharmaceutical companies) GSK, Happify, Lilly (DMC), Leo, Janssen Biologics, Neumentum, Novartis Corp, Pfizer, UCB (DSMB), Neuroderm (DSMB), Regeneron, Trevi, and Mindera Dx., receiving honoraria; and receives research grants (to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania) from Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer Inc.; and received payment for continuing medical education work related to psoriasis that was supported indirectly by pharmaceutical sponsors. Dr Gelfand is a co-patent holder of resiquimod for treatment of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Dr Gelfand is a Deputy Editor for the Journal of Investigative Dermatology receiving honoraria from the Society for Investigative Dermatology, is Chief Medical Editor for Healio Psoriatic Disease (receiving honoraria) and is a member of the Board of Directors for the International Psoriasis Council, receiving no honoraria. AG-C has served as a consultant for Abbie, Janssen, Novartis, Lilly, Almirall, Celgene, and Leo Pharma, receiving grants/other payments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lerman JB, Joshi AA, Chaturvedi A, Aberra TM, Dey AK, Rodante JA, et al. Coronary plaque characterization in psoriasis reveals high-risk features that improve after treatment in a prospective observational study. Circulation 2017; 136: 263–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez-Cantero A, Gonzalez-Cantero J, Sanchez-Moya AI, Perez-Hortet C, Arias-Santiago S, Schoendorff-Ortega C, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in psoriasis. Usefulness of femoral artery ultrasound for the diagnosis, and analysis of its relationship with insulin resistance. PloS One 2019; 14: e0211808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA 2006; 296: 1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, Azfar RS, Kurd SK, Wang X, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 2009; 129: 2411–2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhana A, Yen H, Yen H, Cho E. All-cause and cause-specific mortality in psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: 1332–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samarasekera EJ, Neilson JM, Warren RB, Parnham J, Smith CH. Incidence of cardiovascular disease in individuals with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol 2013; 133: 2340–2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karbach S, Hobohm L, Wild J, Münzel T, Gori T, Wegner J, et al. Impact of psoriasis on mortality rate and outcome in myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc 2020; 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garshick MS, Barrett TJ, Wechter T, Azarchi S, Scher JU, Neimann A, et al. Inflammasome signaling and impaired vascular health in psoriasis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2019; 39: 787–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karbach S, Croxford AL, Oelze M, Schüler R, Minwegen D, Wegner J, et al. Interleukin 17 drives vascular inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and arterial hypertension in psoriasis-like skin disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014; 34: 2658–2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehta NN, Teague HL, Swindell WR, Baumer Y, Ward NL, Xing X, et al. IFN-γ and TNF-α synergism may provide a link between psoriasis and inflammatory atherogenesis. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 13831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55: 829–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. Psoriasis and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013; 68: 654–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Dhillon JS, Armstrong EJ. Psoriasis and smoking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol 2014; 170: 304–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng Q, Sun XY, Miao X, Xu R, Ma T, Zhang YN, et al. Association between physical activity and risk of prevalent psoriasis: a MOOSE-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; 97: e11394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langan SM, Seminara NM, Shin DB, Troxel AB, Kimmel SE, Mehta NN, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study in the United Kingdom. J Invest Dermatol 2012; 132: 556–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wan MT, Shin DB, Hubbard RA, Noe MH, Mehta NN, Gelfand JM. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes: a prospective population-based cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 78: 315–322.e311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeshita J, Wang S, Shin DB, Mehta NN, Kimmel SE, Margolis DJ, et al. Effect of psoriasis severity on hypertension control. JAMA Dermatol 2015; 151: 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutter MK, Kane K, Lunt M, Cordingley L, Littlewood A, Young HS, et al. Primary care-based screening for cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2016; 175: 348–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cea-Calvo L, Vanaclocha F, Belinchón I, Rincón Ó, Juliá B, Puig L. Underdiagnosis of cardiovascular risk factors in outpatients with psoriasis followed at hospital dermatology offices: the PSO-RISK study. Acta Derm Venereol 2016; 96: 972–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eder L, Harvey P, Chandran V, Rosen CF, Dutz J, Elder JT, et al. Gaps in diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriatic disease: an international multicenter study. J Rheumatol 2018; 45: 378–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, Gelfand JM, Lichten J, Mehta NN, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: 1073–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dauden E, Blasco AJ, Bonanad C, Botella R, Carrascosa JM, González-Parra E, et al. Position statement for the management of comorbidities in psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 2058–2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019; 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, Carballo D, Koskinas KC, Bäck M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J 2021; 42: 3227–3337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 3021–3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for high blood pressure in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2015; 163: 778–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis 2019; 290: 140–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019; 139: e1082–e1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jellinger PS, Handelsman Y, Rosenblit PD, Bloomgarden ZT, Fonseca VA, Garber AJ, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Guidelines for Management of Dyslipidemia and Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Endocr Pract 2017; 23: 1–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Diabetes Association . 2.Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes – 2019. Diabetes Care 2019; 42: S13–s28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007; 370: 1453–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Association for Public Opinion Research . Survey disclosure checklist. May 13, 2019. [Accessed 2022, Feb 3]. Available from: https://www.aapor.org/Standards-Ethics/AAPOR-Code-of-Ethics/Survey-Disclosure-Checklist.aspx.

- 33.Zhang Z. Model building strategy for logistic regression: purposeful selection. Ann Transl Med 2016; 4: 111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parsi KK, Brezinski EA, Lin TC, Li CS, Armstrong AW. Are patients with psoriasis being screened for cardiovascular risk factors? A study of screening practices and awareness among primary care physicians and cardiologists. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012; 67: 357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manalo IF, Gilbert KE, Wu JJ. Survey of trends and gaps in dermatologists’ cardiovascular screening practices in psoriasis patients: areas still in need of improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 73: 872–874.e874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alamdari HS, Gustafson CJ, Davis SA, Huang W, Feldman SR. Psoriasis and cardiovascular screening rates in the United States. J Drugs Dermatol 2013; 12: e14–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh P, Silverberg JI. Screening for cardiovascular comorbidity in United States outpatients with psoriasis, hidradenitis, and atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res 2021; 313: 163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.European Association of Preventive Cardiology . HeartScore. [Accessed 2022, April 1]. Available from: https://www.heartscore.org/en_GB/

- 39.American Heart Association . 2018 Prevention guidelines tool CV risk calculator. [Accessed 2022, April 1] Available from: https://static.heart.org/riskcalc/app/index.html#!/baseline-risk.

- 40.Mehta NN, Yu Y, Pinnelas R, Krishnamoorthy P, Shin DB, Troxel AB, et al. Attributable risk estimate of severe psoriasis on major cardiovascular events. Am J Med 2011; 124: 775.e1–775.e7756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gonzalez-Cantero A, Reddy AS, Dey AK, Gonzalez-Cantero J, Munger E, Rodante J, et al. Underperformance of clinical risk scores in identifying imaging-based high cardiovascular risk in psoriasis: results from two observational cohorts. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2022; 29: 591–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barbieri JS, Mostaghimi A, Noe MH, Margolis DJ, Gelfand JM. Use of primary care services among patients with chronic skin disease seen by dermatologists. JAAD Int 2021; 2: 31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Puig L, Ferrándiz C, Pujol RM, Vela E, Albertí-Casas C, Comellas M, et al. Burden of psoriasis in Catalonia: epidemiology, associated comorbidities, health care utilization, and sick leave. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed) 2021; 112: 425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barbieri JS, Beidas RS, Gondo GC, Fishman J, Williams NJ, Armstrong AW, et al. Analysis of specialist and patient perspectives on strategies to improve cardiovascular disease prevention among persons with psoriatic disease. JAMA Dermatol 2022; 158: 252–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cardiovascular Screening Practices and Statin Prescription Habits in Patients with Psoriasis among Dermatologists, Rheumatologists and Primary Care Physicians

Cardiovascular Screening Practices and Statin Prescription Habits in Patients with Psoriasis among Dermatologists, Rheumatologists and Primary Care Physicians