Abstract

A gold nanoparticle-based label-free colorimetric assay was developed to detect the shrimp allergenic protein tropomyosin (TM), an important biomarker responsible for severe clinical reactivity to shellfish. In a gold nanoparticles (AuNPs)-tropomyosin-binding aptamer (TMBA) complex, the aptamer adsorbs onto the surface of AuNPs and dissociates in the presence of TM. In addition, AuNPs tend to aggregate in the presence of ionic salt, revealing a color change (i.e., wine-red to purple/blue) with a shift in the maximum absorption peak from 520 nm. In the presence of specific binding TM, the aptamer folds into a tertiary structure where it more efficiently stabilizes AuNPs toward the salt-induced aggregation with a hypsochromic shift in the absorption spectra compared to the stabilized AuNPs by aptamer alone. Based on the aggregation and sensitive spectral transformation principle, the AuNPs-based colorimetric aptasensor was successfully applied to detect TM with a range of 10–200 nmol/L and a low detection limit of 40 nmol/L in water samples. The reliability, selectivity, and sensitivity of the aptasensor was then tested with food samples spiked with TM. The observed detection limit was as low as 70 nmol/L in shrimp, 90 nmol/L in tofu, and 80 nmol/L in eggs, respectively. We anticipate the proposed AuNPs-based colorimetric aptasensor assay possesses a high potential for the easy and efficient visual colorimetric detection of TM.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42995-020-00085-5.

Keywords: Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), Aptamer, Aggregation, Colorimetric assay, Shellfish allergenic protein, Shrimp tropomyosin (TM)

Introduction

Seafood plays an important role in human nutrition and health. The increased consumption of shellfish has resulted in more frequent reports of adverse reactions and health problems, making it a global concern (Davis et al. 2020; Sicherer and Sampson 2010). Among various seafood allergies, crustacean allergy attributed to shrimp is the most frequently reported and is often associated with IgE-mediated type I hypersensitivity reactions in food allergic patients (Kettlehut and Metcalfe 1988). The different hypersensitive reactions involved in food-induced allergies mediated by the immune system in human body are mostly evidenced as proteins (Cucu et al. 2013). Of various seafood allergenic proteins, shrimp tropomyosin (TM) is a heat-stable and cross-reactive allergen known to cause allergic reactions in humans. Shrimp is consumed all over the world due to its high nutritional value and perceived delicacy. As a result, adverse reactions due to increasing rates of shrimp consumption has affected people’s quality of life and has persisted to be one of the most frightening situations among children and infants (Pedrosa et al. 2015). Considering the possible severity of allergic reactions and no effective medical treatment available, complete avoidance of specific allergen-containing food is the only way to manage seafood allergies (Alves et al. 2016). Such circumstances need to be addressed as they pose a food safety risk, where food-induced severe allergic reactions in sensitive individuals remains a life-threatening event.

At present, immunochemical techniques, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and western blotting, are typically employed to detect allergenic proteins, especially tropomyosin, in food. However, such approaches are highly dependent on the immuno-interaction due to their corresponding selectivity and sensitivity (Lin et al. 2017; Lv et al. 2019; Ren et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2014; Zhou and Tang 2020). Owing to the cross-reactivity of antibodies with other proteins in the sample, purification within SDS-page or affinity tags (e.g., biotin) is a prerequisite to avoid false positives (Prado et al. 2016). Moreover, antibody production is expensive, time-consuming, labor intensive, and is not stable.

Recently, researchers from all over the world have begun using gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) to develop colorimetric-sensing platforms. They are used because of their unique physical and chemical properties (e.g., size and distance-dependent optical properties, high stability, quick response time, low toxicity and easy functionalization) (Aldewachi et al. 2018; Amendola et al. 2014; Jazayeri et al. 2018; Yu et al. 2020). Among various detection probes for analytes, AuNPs-based colorimetric sensor arrays are specifically prevalent, offering several advantages (e.g., simple synthesis procedures, low-cost, high extinction coefficient, instrument-free, and rapid detection via naked eye under visible light) (Li et al. 2019a, b; Sun et al. 2019b). Notably, surface plasmon resonance (SPR)-based sensor arrays are the most eminent among various label-free biosensing techniques, rendering sensitive, robust, and easy detection of various analytes (Unser et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2019).

The most common material used in SPR sensors is AuNPs. It is a well-established that the changes occurring in the colloidal solution of AuNPs from red to purple/blue color during aggregation or purple/blue to red during redispersion are mainly due to the varying interparticle plasmon coupling and the surface plasmon band shift (Ghosh and Pal 2007; Kreibig and Genzel 1985; Srivastava et al. 2005; Su et al. 2003; Yu et al. 2020). The change in the color of colloidal AuNPs solution through aggregation/redispersion of nanoparticles forms the basis for fabrication of various AuNPs-based colorimetric sensor arrays (Chang et al. 2019; Priyadarshini and Pradhan 2017; Sun et al. 2019b). The AuNPs-based colorimetric sensor assays, known to possess high sensitivity because of the high extinction coefficient of AuNPs, is over 1000 times higher compared to the organic dyes (Ghosh and Pal 2007; Liu et al. 2007; Zhao et al. 2008). Notably, (Li and Rothberg 2004a) reported the adsorption properties of unmodified gold nanoparticles in colloidal solution, where the single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) effectively adsorbs onto the surface of AuNPs and inhibits AuNPs from salt-induced aggregation, such as sodium chloride (NaCl). In addition, their study also revealed that ssDNA exhibited strong electrostatic interactions with citrate-coated AuNPs, unveiling the potential to construct AuNPs-based colorimetric sensor arrays (Li and Rothberg 2004a, b). In the past decade, several studies focusing on colorimetric sensor arrays also demonstrated the stabilization/dispersion of AuNPs coated with ssDNA on elevated salt concentrations (Lee et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2011; Shen et al. 2009). Such mechanisms between ssDNA and AuNPs have been widely exploited for developing colorimetric sensor arrays that can detect various analytes (e.g., mercury, dopamine, and thrombin). In such sensor arrays, the aptamers reported are the well characterized ssDNA, which are responsible for the stabilization of AuNPs against salt-induced aggregation (Li et al. 2019a, b; Phanchai et al. 2018; Zheng et al. 2011).

Aptamers have emerged as a class of recognition elements that can bind with a wide range of analytes, such as proteins, metal ions, organic molecules and cells (Grechkin et al. 2020; Jia et al. 2020; Saad et al. 2020; Stojanovic and Landry 2002; Sun et al. 2019a; Wang et al. 2020; Yao et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2020b). Aptamers have been extensively studied as biomaterials in numerous diagnostic applications (e.g., detection of infectious agents, food inspection, antigens/toxins (bacteria), biomarkers (cancer)) (Chandola et al. 2016; Ratajczak et al. 2018, 2019; Song et al. 2019; Zheng et al. 2019). Aptamers in comparison with their antibody counterparts exhibit several advantages for the fabrication of biosensors particularly the colorimetric-based sensor arrays. Advantages include cost-efficient synthesis/modification, high stability and reproducibility, high affinity and selectivity to the target, and flexibility for signal transduction and detection (António et al. 2020; Dollins et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2020a). Of note, in bioanalysis, aptamers have been reckoned as superior to their counterparts (i.e., antibodies) mainly due to the lack of immunogenicity (Nimjee et al. 2005) and stability against biodegradation and denaturation (Liu and Lu 2006). Moreover, one of the properties of aptamers is to undergo target-induced conformational variations. These conformational variations are structural changes resulting from free uncoiled ssDNAs to folded structures upon binding with specific ligands that feature higher rigidity, forming the basis of various aptamer-based sensing approaches, such as colorimetric (Kasoju et al. 2020; Tian 2019), electrochemical (Amor-Gutiérrez et al. 2020; Li et al. 2019a, b), and fluorescent methods (Kim et al. 2010; Li et al. 2019a, b) . In published studies, detection of allergens has been demonstrated by employing aptamer-based assays combined with various novel nanomaterials, such as gold nanoparticles (Lerga et al. 2020), quantum dots (Qdots) (Zhou et al. 2020), graphene oxides (Chinnappan et al. 2020), and magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) (Xu et al. 2020), etc.

To fabricate AuNPs-based colorimetric aptasensors, several researchers have already exploited the potencies of both AuNPs and aptamers revealing numerous advantages (e.g., simple detection, high selectivity, sensitivity, and outstanding throughput) (António et al. 2020; Chen et al. 2020; Gao et al. 2020; Lee et al. 2019; Ma et al. 2018; Sheng et al. 2020; Wu et al. 2012; Xu et al. 2020) . By integrating AuNPs and aptamers to construct colorimetric-based sensor arrays based on the principles of a study published by Wei et al. (2007), we developed a simple, rapid, naked eye detection method for seafood allergenic proteins, such as TM.

In the present study, we developed an AuNPs aggregation-based colorimetric aptasensor. We used an ssDNA aptamer as a molecular recognition element because it has high selectivity and affinity toward TM, revealing its potential as to detect allergenic proteins in food.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of gold nanoparticles

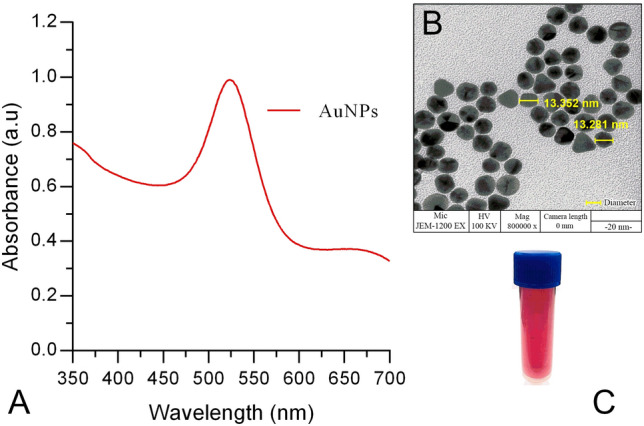

Approximately 13 nm AuNPs were synthesized using the Turkevich method. The colloidal solutions of spherical AuNPs were wine red (Fig. 1c). The particles absorbed light due to the surface plasmon absorption band with a maximum at 520 nm (Baptista et al. 2008), as shown in Fig. 1a. The concentration of the newly synthesized AuNPs shown in Fig. 1a was determined to be 2.64 nmol/L, using the extinction coefficient 1.39 × 108 mol L−1 cm−1. The morphology, size, and shape of synthesized AuNPs were characterized using transmission electron microscopy as shown in Fig. 1b. The citrate reduced AuNPs with diameters ranging from 10 to 20 nm, demonstrating the plasmonic peak at 520 nm are stable and spherical as described in a previous report (Frens 1973). The TEM image also revealed that the gold colloid is in a monodispersional state, which is due to the negatively charged layer of citrate ions (Verma et al. 2014), which as shown in Fig. 1b repelled each other. The zeta potential of the prepared AuNPs were examined using a ZetaSizer instrument, in which the polydispersity Index was observed under 0.3 PDI (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Fig. 1.

a UV–visible absorption spectrum of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs); b TEM image of citrate-stabilized gold nanoparticles (AuNPs); and c typical wine red color of the colloidal AuNPs

Interaction of aptamer TMBA and TM with AuNPs

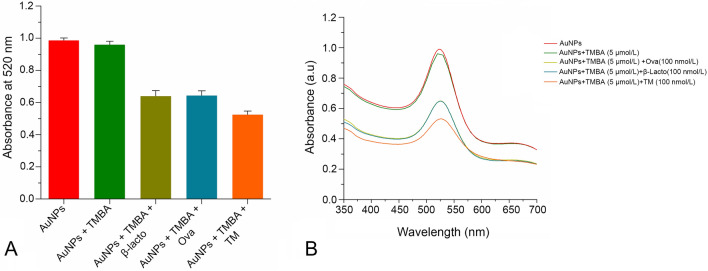

The interaction of TMBA and TM with AuNPs was investigated by observing the change in the absorbance spectra at 520 nm as shown in Fig. 2a, b. Briefly, 200 µl of AuNPs, 30 µl (5 µmol/L) TMBA, and 30 µl (100 nmol/L) TM and two control proteins were individually mixed as follows: (a) AuNPs; (b) AuNPs-TMBA; (c) AuNPs-TMBA-β-lactoglobulin; (d) AuNPs-TMBA-ovalbumin and (e) AuNPs-TMBA-tropomyosin, respectively. A slight change in the absorbance spectra of AuNPs with addition of TMBA without TM was observed, whereas with addition of both TMBA and TM the maximum change in the absorbance spectra of AuNPs was observed. However, compared to the AuNPs-TMBA-TM, the absorbance spectra of AuNPs upon addition of TMBA and two control allergenic proteins separately [i.e., β-lactoglobulin (AuNPS-TMBA-β-lactoglobulin) and ovalbumin (AuNPS-TMBA-Ovalbumin)] resulted in an equal change in the absorbance spectra of AuNPs. This showed that the maximum change only occurred with TMBA-TM (aptamer-TM) at 520 nm (Fig. 2b), respectively. Thus, there is a strong and significant interaction of TMBA/TM with AuNPs. Several studies were conducted to investigate the mechanism and kinetics of biomolecules (ssDNA) having different structural and charge properties than AuNPs (Demers et al. 2002; Li and Rothberg 2004b; Nelson and Rothberg 2011). The secondary structure of the aptamer played a vital role in recognition-based target binding between an aptamer sequence and its specific target (Sullivan et al. 2019). In addition, various folds allowed the aptamer to exploit various binding mechanisms (e.g., molecular shape complementarity or intercalation in the case of small molecules binding double-stranded regions of the aptamer). Aptamers, upon folding, attain a unique three-dimensional structure so can interact with virtually any ligand having a complementary structure (Battig and Wang 2014; Tapp et al. 2018). The tropomyosin-binding aptamer used in this study is known to have a secondary structure reported (Zhang et al. 2017), with highest affinity binding to tropomyosin and freely folds without any chemical modifications. Considering such advantages, we applied a tropomyosin-binding aptamer in an AuNPs-based colorimetric based sensor array for detection of our target analyte.

Fig. 2.

a Interaction of tropomyosin binding aptamer (TMBA) and target protein tropomyosin (TM) with gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) observed at 520 nm maximum absorbance wavelength and b interaction of aptamer and its target protein with AuNPs via UV–visible Spectroscopy

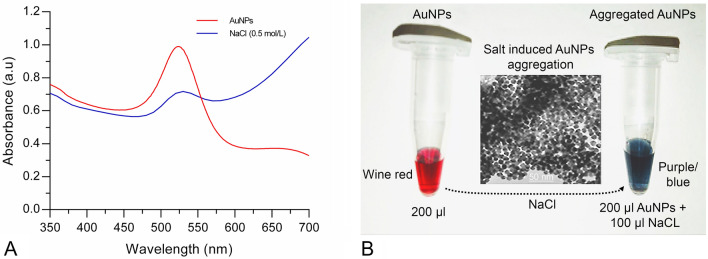

Aggregation phenomenon of AuNPs

Almost all colorimetric sensor arrays involving gold nanoparticles are based on salt-induced aggregation of AuNPs (i.e., color change of AuNPs colloidal solution from wine red to purple/blue or purple/blue to wine red (aggregation/redispersion)) (Chang et al. 2019; Su et al. 2003). The change in the colloidal gold absorption spectra with the addition of (0.5 mol/L) NaCl was examined (Fig. 3a). In addition, the color change of the colloidal gold and the aggregation of nanoparticles were also observed by the naked eye and TEM (Fig. 3b). Thus, the phenomenon of AuNPs aggregation forms the basis for colorimetric-based sensor arrays opening up the possibility of rapid, simple, reliable detection for various analytes.

Fig. 3.

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) aggregation phenomenon a UV–Vis spectra and b naked eye with TEM

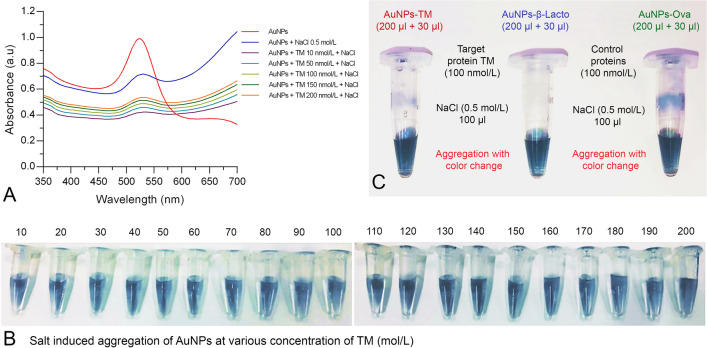

Interaction/binding of TM with AuNPs via induced aggregation

This study was conducted to determine if TM interacts with AuNPs and if there is any binding or adsorption on to the surface of AuNPs. In this experiment, various concentrations of TM were prepared (10–200 nmol/L), mixed with AuNPs, then incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Briefly, 30 µl of TM at various concentrations were added separately in a vial containing 200 µl AuNPs. Then, 100 µl NaCl (0.5 mol/L) was added into the AuNPs-TM complex to observe induced aggregation colorimetrically as well as via UV–Vis spectroscopy. In all, the AuNPs vials containing different TM concentrations (10–200 nmol/L) and with subsequent addition of NaCl resulted in aggregation observed by color change (i.e., from wine red to blue). Upon addition of NaCl, the resulting aggregation was determined from the changes in the absorbance spectra of AuNPs with each different concentration of TM compared to the AuNPs-NaCl absorbance spectra (without TM) (Fig. 4a, b). It is clear in both figures that there is no adsorption of TM onto AuNPs, particularly where colloidal AuNPs causes aggregation due to the addition of elevated NaCl salt concentration (0.5 mol/L). Moreover, to better understand whether the induced aggregation occurs only upon addition of TM or with other control allergenic proteins (e.g., β-lactoglobulin and ovalbumin), a colorimetric analysis was conducted. Briefly, 30 µl (100 nmol/L) of TM (target), β-lactoglobulin and ovalbumin (controls) were mixed with vials containing 200 µl AuNPs, followed by incubation for 5 min at room temperature. Later, AuNPs-TM, AuNPs-β-lactoglobulin, and AuNPs-ovalbumin were separately added with NaCl to determine if there was any induced aggregation of AuNPs in the control samples. As expected, we found a similar change of aggregation observed in both the control samples compared with TM (Fig. 4c). Finally, we concluded that there is no adsorption of TM or other control allergenic proteins onto AuNPs. Hence, for the above reasons the tropomyosin-binding aptamer (TMBA) was further applied to selectively detect TM by UV–Visible spectroscopy as well colorimetric naked eye recognition.

Fig. 4.

Investigation of gold nanoparticles-tropomyosin (AuNPs-TM) interaction/binding via induced aggregation a UV–Vis spectroscopy; b visual colorimetric salt-induced aggregation of AuNPs-TM (at various concentration of TM); and c visual colorimetric salt-induced aggregation of AuNPs-TM and AuNPs-control allergenic proteins at 100 nmol/L NaCl concentration

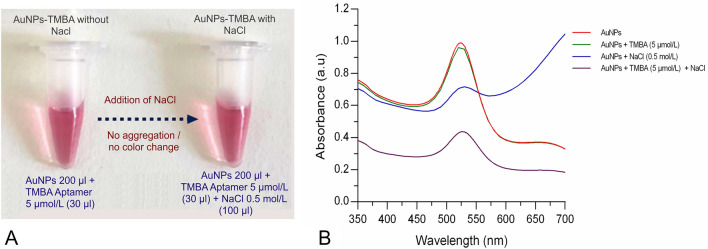

Aptamer TMBA adsorption onto AuNPs and protection against induced aggregation

We demonstrated interaction/binding of TM with AuNPs via induced aggregation. Specifically, TM or control allergenic proteins did not bind/adsorbed with/onto AuNPs and NaCl-induced aggregation of AuNPs occurred in all cases observed with color change (i.e., from wine red to blue). To achieve our target, we applied TMBA to form an AuNPs-aptamer complex that recognized TM specifically. This experiment was conducted to determine if the TMBA adsorbs/binds with/onto AuNPs and if aggregation occurs or not upon addition of elevated salt concentration. Briefly, two separate vials containing 30 µl of (5 µmol/L) TMBA was mixed into 200 µl AuNPs and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Further, investigation for induced aggregation or color change (i.e., AuNPs-TMBA and AuNPs-TMBA-NaCl) were determined as shown in Fig. 5a. Upon addition of 100 µl (0.5 mol/L) NaCl into an incubated vial separately containing 200 µl AuNPs and 30 µl (5 µmol/L) of TMBA, aggregation did not occur, clearly seen with no color change in vials containing AuNPs-TMBA-NaCl. Such phenomenon occurred mainly because of the adsorption characteristic of ssDNA aptamer onto the AuNPs surface, which protects the aggregation of AuNPs against elevated salt aggregation. Further, to determine the mechanism of the AuNPs-TMBA and AuNPs-TMBA-NaCl interaction, UV–Vis spectroscopy was performed (Fig. 5b), revealing the interaction of aptamer with AuNPs upon addition of NaCl. In the results section describing the interaction of aptamer TMBA and TM with AuNPs, we determined that upon addition of TMBA in AuNPs there was a slight change in the absorbance spectra, while aggregation in AuNPs occurred with addition of NaCl (AuNPs-NaCl) without TMBA. Upon addition of NaCl into an AuNPs-TMBA complex in order to investigate salt-induced aggregation (i.e., AuNPs-TMBA-NaCl), a significant change in the absorbance spectra was observed. A major change in the AuNPs-TMBA absorbance spectra was observed with the addition of NaCl, whereas, there was no absorbance shift or color change from red to blue (Fig. 5b) compared to the AuNPs-NaCl aggregation absorbance spectra (blue) (Fig. 3a), respectively.

Fig. 5.

Mechanism of tropomyosin binding aptamer (TMBA) adsorption onto AuNPs with/without NaCl induced aggregation; a colorimetric investigation; and b UV–vis spectroscopy

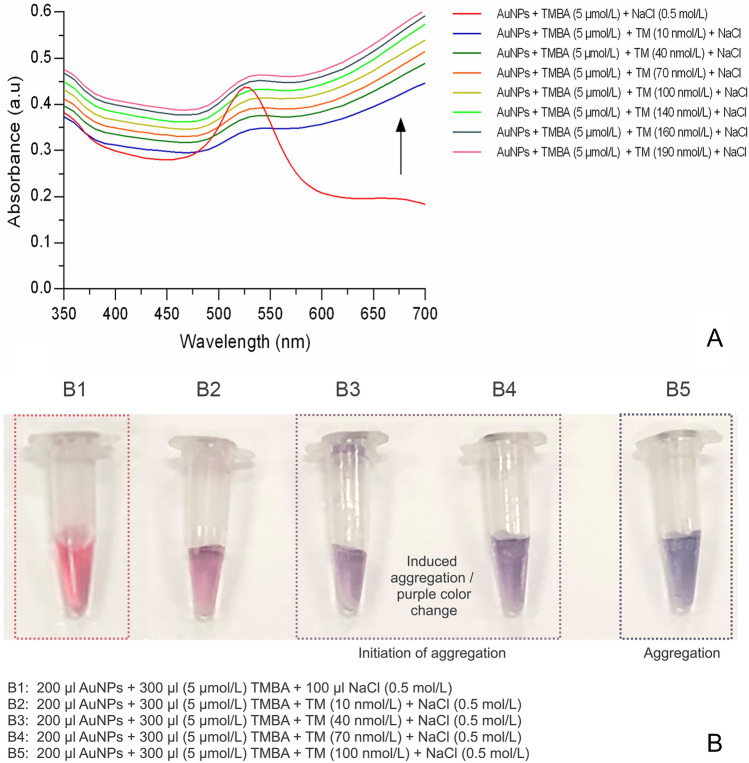

Determination of TM using AuNPs-TMBA complex with NaCl-induced aggregation

In the previous result part (i.e., Aptamer TMBA adsorption onto AuNPs and protection against induced aggregation), the TMBA was shown to adsorb onto the AuNPs and protect itself against salt-induced aggregation with no evidence color change (Fig. 5a, b). Moreover, in the same section, the investigation of TM with the AuNPs-TMBA complex, a significant interaction was specifically observed with TM compared to the other two control allergenic proteins (Fig. 2). Hence, considering all the above mechanisms, TM was applied to the AuNPs-TMBA complex for recognition via salt-induced aggregation. Briefly, 200 µl AuNPs were put into separate vials and 30 µl (5 µmol/L) TMBA was mixed and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. After incubation, TM, at various concentrations ranging from 10 nmol/L to 200 nmol/L, was mixed into different vials containing AuNPs-TMBA complex. These vials were then incubated for 5 min at room temperature. UV–Vis spectroscopy and visual colorimetric results for AuNPs-TMBA-NaCl and AuNPs-TMBA-TM-NaCl were then obtained.

As soon as TM was applied to the AuNPs-TMBA complex, NaCl induced-aggregation was initiated with significant colorimetric changes (i.e., the vial containing AuNPs-TMBA-NaCl, revealing no color change). However, with AuNPs-TMBA-TM-NaCl, the color changed from red to purple remained blue (revealing induced aggregation). In addition, changes in the absorbance spectra of AuNPs-TMBA complex upon addition of various concentrations of TM initiated by salt-induced aggregation were also observed as shown in Fig. 6. The plot of the salt-induced aggregation increasing with increasing TM concentrations was represented as the absorbance spectra at 520 nm maximum wavelength, which was consistent with the mechanism as shown in the supplementary file (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S3), respectively.

Fig. 6.

Determination of tropomyosin (TM) using AuNPs-TMBA complex via salt-induced aggregation a UV–Vis spectroscopy of AuNPs-TMBA-TM-NaCl and b visual colorimetric representation of TM recognition via induced aggregation

The mechanism of the colorimetric effects between AuNPs-TMBA and AuNPS-TMBA-TM can be explained as follows. It is established that AuNPs prepared using a citrate reduction method are stable due to the negative capping agent’s (i.e., citrate) electrostatic repulsion against van der Waals attraction between AuNPs (Grabar et al. 1995; Li and Rothberg 2004a, b). Thus, addition of elevated salt screens the repulsion between the unmodified negative-charged AuNPs causing the aggregation of AuNPs, revealing a color change (i.e., wine red-to-blue, respectively). Moreover, previous reports indicated there is a stronger coordination interaction between the nitrogen atoms of the unfolded ssDNA and AuNPs than electrostatic repulsion between the negative-charged phosphate backbone and the negative-charged AuNPs (Li and Rothberg 2004a; Wang et al. 2006). Hence, the TMBA adsorbs onto AuNPs and increases the stability of AuNPs against salt-induced aggregation, which folds further in recognition/binding with target TM identified by a color change from red to purple then blue during aggregation, respectively.

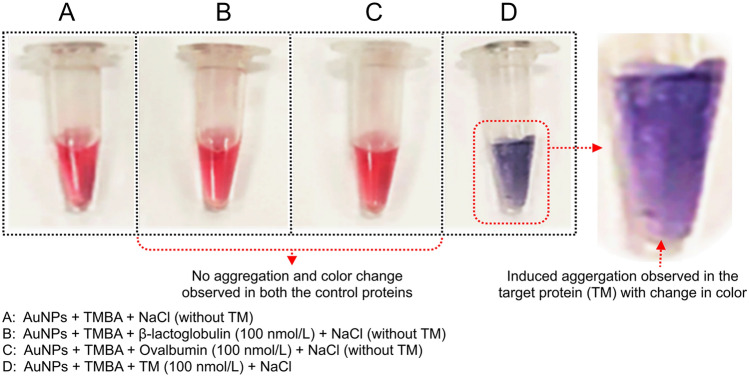

Selectivity and sensitivity of AuNPs-aptamer based colorimetric sensor array

In the results section (i.e., Determination of tropomyosin using AuNPs-TMBA complex with NaCl induced aggregation), we reported that the induced aggregation did not occur in the presence of TMBA. However, with addition of TM in AuNPs-TMBA complex, NaCl-induced aggregation changes were observed in the absorbance spectra as well as colorimetric changes as shown in Fig. 6. Thus, we decided to validate our AuNPs aptamer-based colorimetric sensor array for selective and sensitive detection of TM. We used two control allergenic proteins (β-lactoglobulin and ovalbumin) against the TMBA. The colorimetric detection sensitivity of TM using the AuNPs-aptamer sensor was observed in the range of 70–100 nmol/L, where at 70 nmol/L concentration the color of the AuNPs colloidal solution changed from red to purple then to blue with aggregation initiated at 100 nmol/L (Figs. 6b and 7). The selectivity of the AuNPs-aptamer colorimetric sensor for TM was examined employing two control allergenic proteins (i.e., β-lactoglobulin and ovalbumin). No color change (aggregation) was observed upon addition of NaCl in AuNPs-TMBA-β-lactoglobulin and AuNPs-TMBA-ovalbumin complexes per the similar procedure followed for TM (Fig. 5a). Our results revealed that salt-induced aggregation of AuNPs using TMBA as a target recognition element for TM detection only occurred with TMBA-TM binding, revealing it to be a highly specific and sensitive colorimetric-based sensor array.

Fig. 7.

AuNPs-aptamer based colorimetric sensor array: selectivity and sensitivity of tropomyosin (TM) detection

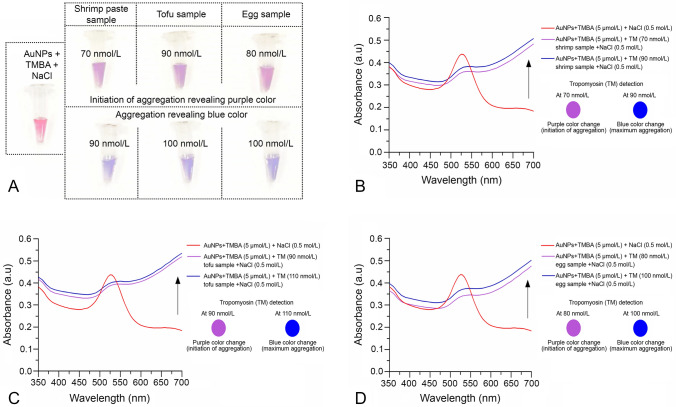

TM detection in food samples using AuNPs-aptamer colorimetric sensor array

To implement the AuNPs aptamer-based colorimetric sensor array for detection of TM in food samples, four observations were completed using three different food products obtained from a local supermarket in Qingdao, China. Briefly, 30 µl (5 µmol/L) TMBA was mixed into 200 µl AuNPs and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. The three food samples spiked with TM (30 µl) at various concentrations (10–200 nmol/L) were added separately to an AuNPs-TMBA complex and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. After incubation, salt-induced aggregation was carried out using 100 µl NaCl (0.5 mol/L) in the AuNPs-TMBA-TM complex. The visual detection of color change (aggregation) was obtained as shown in Fig. 8a. The initiation of salt-induced aggregation (i.e., colorimetric changes observed in the three different food samples) were recorded at 70 nmol/L (shrimp), 90 nmol/L (tofu), and 80 nmol/L (egg), revealing purple color and maximum aggregation occurring at 90 nmol/L, 110 nmol/L, and 100 nmol/L with a blue color change, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). The UV–visible spectroscopy of salt-induced aggregation of AuNPs used to recognize TM spiked food samples was carried out as shown in Fig. 8b shrimp sample, (c) tofu and (d) egg, respectively. In addition, the plot of the spectral absorbance vs. increasing TM concentrations was also carried out at 520 nm maximum wavelength for all three TM spiked food samples (Supplementary Fig. S4 a–c).

Fig. 8.

Colorimetric detection of tropomyosin (TM) in real food samples a visual naked eye detection and b–d UV–Vis spectroscopy of real food samples for recognition of TM via salt-induced aggregation of AuNPs

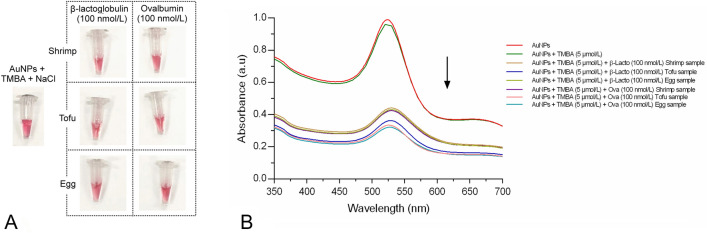

Selectivity validation of AuNPs-aptamer based colorimetric sensor array for TM using control proteins spiked in food samples

In the final experiment, all three food samples were spiked with control proteins (β-lactoglobulin and ovalbumin) at 100 nmol/L separately to reveal the selectivity of the AuNPs-aptamer sensor array toward TM protein via visual colorimetric detection as shown in Fig. 9a. No color change was observed in any food sample spiked with both the control proteins. In addition, the UV–visible spectroscopy was carried out using food samples spiked with control proteins to observe spectral changes. As expected, there was no aggregation found in any samples although there was a significant reduction in the peaks of all three food samples spiked with control proteins. The maximum reduction in the absorbance peaks was observed in β-lactoglobulin spiked tofu and egg samples and ovalbumin spiked tofu and egg samples, respectively (Fig. 9b). These results validate that our AuNPs-aptamer colorimetric sensor array specifically recognized TM via salt-induced aggregation.

Fig. 9.

Selectivity validation of AuNPs-aptamer colorimetric sensor array a colorimetric visual observation and b UV–visible spectroscopy of control proteins spiked food samples

Conclusion

In conclusion, a simple rapid and selective AuNPs-aptamer colorimetric-based sensor array was fabricated to detect shrimp TM. The main advantage of this colorimetric sensor is the easy and cost-effective preparation of AuNPs, combining it with the ssDNA aptamer without involving complex protocols. The only disadvantage is the stability of AuNPs, which loses potency (aggregation) after five months. Our results showed that implementing AuNPs and aptamer, with their outstanding properties (i.e., AuNPs salt-induced aggregation and aptamer adsorption onto AuNPs and binding with TM employs “AuNPs-aptamer” as a selective recognition complex) can obtain a colorimetric visual detection of TM. The induced aggregation of AuNPs colloidal solution occurred upon addition of NaCl into the complex AuNPs-TMBA-TM, which can possibly be analyzed within 10–15 min. As a result, TM can be easily recognized and determined through the naked eye and UV–Vis spectroscopy as well. The detection limit of TM using the colorimetric sensor array is in the range of 70–100 nmol/L in water samples and as low at 70 nmol/L (shrimp), 90 nmol/L (tofu), and 80 nmol/L (egg) in food samples, respectively. The results validated that our method is efficient for simple, convenient and rapid high selectivity detection of TM. Thus, this colorimetric-based approach possesses a high potential in food safety applications for the qualitative detection of allergenic food proteins, such as TM, mainly due to easy fabrication and operation of a colorimetric sensor array, which is based on AuNPs-aptamer holding excellent selectivity and sensitivity towards its targets.

Materials and methods

Materials

All chemicals used in this study were of analytical reagent grade and used without further purification. Tetrachloroauric acid (HAuCl4), trisodium citrate (C6H5Na3O7), nitric acid (HNO3), hydrochloric acid (H2SO4), sodium chloride (NaCl), β-lactoglobulin, and ovalbumin were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, China. A 96-well polystyrene microplate (12 strips of 8 wells) was purchased from Corning (Corning, NY, USA). The solutions were prepared using ultra-high purity water from a Millipore water purification system. Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) was obtained from a local fish market, Qingdao, Shandong Province, China. The sequence of the tropomyosin-binding aptamer (Zhang et al. 2018) 5′-TACTAACGGTACAAGCTACCAGGCCGCCAACGTTGACCTAGAAGCACTGCCAGACCCGAACGTTGACCTAGAAGC-3′, was chemically synthesized by Sangon Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), further dissolved in ultrapure water, then stored at 4 °C prior to use. The tropomyosin-binding aptamer was denoted as TMBA. The UV–visible absorption spectra of ssDNA and spectral measurements of the colloidal gold solution were performed using a PowerWave XS Microplate Spectrophotometer, BioTek Instruments (American BioTek Manufacturing Inc). The Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) was carried out on JEM-1200EX Instrument (JEOL Co. Ltd, Japan) provided by Qingdao Medical Hospital, Qingdao, China.

Extraction and purification of Tropomyosin (TM)

TM Extraction

Fresh shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) was obtained from a local seafood market (Qingdao, China) then properly iced. TM was extracted from a muscle sample using a previously established method with slight modifications (Seiki et al. 2007). Briefly, 1 g of muscle sample was homogenized using 10 ml of phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for 1 h at room temperature. Followed by centrifugation at 3000 g for 20 min, the suspension was then confirmed for the ultimate tropomyosin-containing fractions.

TM Purification

The extracted shrimp TM was then purified by employing a combination of ammonium sulfate and isoelectric precipitation using a previously established protocol (Bailey 1948; Lasekan and Nayak 2016) with slight modifications developed in our laboratory. The shrimp muscle was blended using a food processor, homogenized, centrifuged, and suspended to obtain the contents. Later on, the contents were treated with cold acetone to obtain a powder form. The precipitate was suspended and centrifuged again, while the extracts were fractioned using ammonium sulfate and isoelectric precipitation. Finally, the precipitate was dissolved and dialyzed overnight, followed by heating in a water bath at normal boiling temperature for 10 min. TM was obtained then stored at − 20 °C prior to use.

Synthesis of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs)

To avoid contamination during the synthesis, glassware used in our experiments were soaked for 15–20 min in aqua regia solution (mixture of nitric acid and hydrochloric acid optimally in a molar ratio of 1:3) then rinsed with Milli-Q water until the aqua regia solution was thoroughly neutral. Later on, all the treated glassware were oven dried at 60 °C for 2 h, allowed to cool, wrapped in plastic sheets to avoid long-term contamination, then stored prior to use for the synthesis. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) were synthesized as per the Turkevich method (Frens 1973), which is a classical citrate reduction method. In a three-necked conical flask, the aqueous solution of HAuCl4 (200 ml, 1 mmol/L) was heated to boiling while vigorous stirring, followed by rapid injection of 1% (20 ml, 38.8 mmol/L) of trisodium citrate solution to obtain ~ 13 nm colloidal AuNPs. The reaction solution was continuously boiled (approximately 20 min) until the color changed from pale yellow to wine red. The reaction solution was allowed to cool at room temperature. Synthesized colloidal AuNPs were collected, sealed, and stored at 4 °C to protect from light. The particle concentration of AuNPs was estimated to be approximately 2.64 nmol/L, which was determined according to Beer’s law by using the extinction co-efficient of 1.39 × 108 (mol/L)−1 cm−1 for ~ 13 nm AuNPs in diameter at 520 nm (Grabar et al. 1995; Mucic et al. 1998).

Preparation of protein stock solutions

The target protein (tropomyosin) and control allergenic proteins (β-lactoglobulin and ovalbumin) stock solutions were prepared by spiking with different concentrations at 10–200 nmol/L in the ultrapure water solution and stored at − 20 °C prior to use for detection using AuNPs-aptamer colorimetric sensor array.

Colorimetric assay procedure

Briefly, 200 µl of AuNPs were added separately in vials. To this 30 µl of tropomyosin-binding aptamer was mixed at a concentration of 5 µmol/L. The target protein TM and 30 µl control allergenic proteins (β-lactoglobulin and ovalbumin) of different concentrations ranging from 10 nmol/L to 200 nmol/L were then added separately to the vials containing AuNPs-aptamer complex. The mixture was incubated at room temperature (RT) for 5 min. Later, to examine the induce aggregation, 100 µl of (0.5 mol/L) NaCl solution was added into AuNPs-aptamer complex. The induce aggregation of AuNPs was determined using target protein with/without tropomyosin-binding aptamer and control allergenic proteins with TMBA, resulting in a change in color and absorbance spectra following the mechanism, respectively, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. All experiments were conducted at least three times in triplicate. The colorimetric assay procedure for tropomyosin selectivity compared with other control proteins (β-lactoglobulin and ovalbumin) is shown in Supplementary Figs. S2.

Sample description and digestion for tropomyosin detection in food samples

To verify the feasibility of our AuNPs-aptamer colorimetric sensor array for TM detection in food samples, three food product samples – shrimp paste, tofu, and egg—were obtained from a local seafood supermarket (Li Qun, Qingdao, China) and stored at − 20 °C in special freezer bags until analysis. The three food samples were pretreated and spiked with the target protein TM and control proteins (β-lactoglobulin and ovalbumin). Food samples not completely thawed were cut into small pieces then uniformly ground using a food processor and stored again at − 20 °C. About 50 mg of each sample was transferred separately into 1 ml Milli-Q water and held overnight at 4 °C. The mixture was then centrifuged at 10,000 for 30 min and clear supernatants obtained. All three food extracts were further diluted 1:100 by adding Milli-Q water followed by spiking the TM (10 nmol/L to 200 nmol/L) and control proteins (100 nmol/L), respectively. Four observations were made: (1) colorimetric detection of TM in three food samples; (2) UV–Vis spectral observations of the three food samples spiked with TM; (3) plot of the increasing absorbance spectra at 520 nm vs increasing TM concentrations in food samples; and (4) selectivity of the AuNPs-aptamer colorimetric sensor array using control proteins represented through colorimetric visual and UV–Vis spectroscopy, respectively.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank College of Food Science and Engineering, Food Safety Laboratory, Ocean University of China for providing the research. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771892).

Author contributions

Design of the AuNPs-based colorimetric sensor array and experiments: TRP; aptasensor conceptualization: TRP, MAS and ZL; funding acquisition: HL and ZL; software: HZ, XL and KW; manuscript writing: TRP; manuscript review and editing: TRP and ZL.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Animal and human rights statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Aldewachi H, Chalati T, Woodroofe M, Bricklebank N, Sharrack B, Gardiner P. Gold nanoparticle-based colorimetric biosensors. Nanoscale. 2018;10:18–33. doi: 10.1039/C7NR06367A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves RC, Barroso MF, González-García MB, Oliveira MBP, Delerue-Matos C. New trends in food allergens detection: toward biosensing strategies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56:2304–2319. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2013.831026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amendola V, Meneghetti M, Stener M, Guo Y, Chen S, Crespo P, García MA, Hernando A, Pengo P, Pasquato L. Physico-chemical characteristics of gold nanoparticles. Compr Anal Chem. 2014;66:81–152. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63285-2.00003-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amor-Gutiérrez O, Selvolini G, Fernández-Abedul MT, de la Escosura-Muñiz A, Marrazza G. Folding-based electrochemical aptasensor for the determination of β-lactoglobulin on Poly-L-Lysine modified graphite electrodes. Sensors. 2020;20:2349. doi: 10.3390/s20082349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- António M, Ferreira R, Vitorino R, Daniel-da-Silva AL (2020) A simple aptamer-based colorimetric assay for rapid detection of C-reactive protein using gold nanoparticles. Talanta: 120868 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bailey K. Tropomyosin: a new asymmetric protein component of the muscle fibril. Biochem J. 1948;43:271. doi: 10.1042/bj0430271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista P, Pereira E, Eaton P, Doria G, Miranda A, Gomes I, Quaresma P, Franco R. Gold nanoparticles for the development of clinical diagnosis methods. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:943–950. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1768-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battig MR, Wang Y (2014) Nucleic acid aptamers for biomaterials development. In: Sangamesh K, Cato L, Meng D (eds.) Natural and synthetic biomedical polymers, Elsevier, pp 287–299

- Chandola C, Kalme S, Casteleijn MG, Urtti A, Neerathilingam M. Application of aptamers in diagnostics, drug-delivery and imaging. J Biosci. 2016;41:535–561. doi: 10.1007/s12038-016-9632-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CC, Chen CP, Wu TH, Yang CH, Lin CW, Chen CY. Gold nanoparticle-based colorimetric strategies for chemical and biological sensing applications. Nanomaterials. 2019;9:861. doi: 10.3390/nano9060861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Sheng R, Wang P, Ouyang Q, Wang A, Ali S, Zareef M, Hassan MM. Ultra-sensitive detection of malathion residues using FRET-based upconversion fluorescence sensor in food. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2020;241:118654. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2020.118654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnappan R, Rahamn AA, AlZabn R, Kamath S, Lopata AL, Abu-Salah KM, Zourob M. Aptameric biosensor for the sensitive detection of major shrimp allergen, tropomyosin. Food Chem. 2020;314:126133. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.126133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucu T, Jacxsens L, De Meulenaer B. Analysis to support allergen risk management: which way to go? J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:5624–5633. doi: 10.1021/jf303337z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CM, Gupta RS, Aktas ON, Diaz V, Kamath SD, Lopata AL. Clinical management of seafood allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demers LM, Östblom M, Zhang H, Jang N-H, Liedberg B, Mirkin CA. Thermal desorption behavior and binding properties of DNA bases and nucleosides on gold. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:11248–11249. doi: 10.1021/ja0265355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollins CM, Nair S, Sullenger BA. Aptamers in immunotherapy. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:443–450. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frens G. Controlled nucleation for the regulation of the particle size in monodisperse gold suspensions. Nat Phys Sci. 1973;241:20–22. doi: 10.1038/physci241020a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Xiang W, Deng Z, Shi K, Wang H, Shi H. Cocaine detection using aptamer and molybdenum disulfide-gold nanoparticle-based sensors. Nanomedicine. 2020;15:325–335. doi: 10.2217/nnm-2019-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh SK, Pal T. Interparticle coupling effect on the surface plasmon resonance of gold nanoparticles: from theory to applications. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4797–4862. doi: 10.1021/cr0680282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabar KC, Freeman RG, Hommer MB, Natan MJ. Preparation and characterization of Au colloid monolayers. Anal Chem. 1995;67:735–743. doi: 10.1021/ac00100a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grechkin YA, Grechkina SL, Zaripov EA, Fedorenko SV, Mustafina AR, Berezovski MV. Aptamer-conjugated Tb (III)-doped silica nanoparticles for luminescent detection of leukemia cells. Biomedicines. 2020;8:14. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazayeri MH, Aghaie T, Avan A, Vatankhah A, Ghaffari MR. Colorimetric detection based on gold nano particles (GNPs): an easy, fast, inexpensive, low-cost and short time method in detection of analytes (protein, DNA, and ion) Sens Biosens Res. 2018;20:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jia M, Sha J, Li Z, Wang W, Zhang H. High affinity truncated aptamers for ultra-sensitive colorimetric detection of bisphenol A with label-free aptasensor. Food Chem. 2020;317:126459. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasoju A, Shrikrishna NS, Shahdeo D, Khan AA, Alanazi AM, Gandhi S. Microfluidic paper device for rapid detection of aflatoxin B1 using an aptamer based colorimetric assay. RSC Adv. 2020;10:11843–11850. doi: 10.1039/D0RA00062K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettlehut B, Metcalfe D. Allergy: principles and practice. 3. St Louis: The CV Mosby Co.; 1988. Adverse reactions to foods; pp. 1481–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Kim YS, Kim JH, Kim IA, Lee SJ, Jurng J, Gu MB. A novel colorimetric aptasensor using gold nanoparticle for a highly sensitive and specific detection of oxytetracycline. Biosens Bioelectron. 2010;26:1644–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2010.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreibig U, Genzel L. Optical absorption of small metallic particles. Surf Sci. 1985;156:678–700. doi: 10.1016/0039-6028(85)90239-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lasekan AO, Nayak B. Effects of buffer additives and thermal processing methods on the solubility of shrimp (Penaeus monodon) proteins and the immunoreactivity of its major allergen. Food Chem. 2016;200:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Wang Z, Liu J, Lu Y. Highly sensitive and selective colorimetric sensors for uranyl (UO22+): Development and comparison of labeled and label-free DNAzyme-gold nanoparticle systems. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14217–14226. doi: 10.1021/ja803607z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EH, Lee SK, Kim MJ, Lee SW. Simple and rapid detection of bisphenol A using a gold nanoparticle-based colorimetric aptasensor. Food Chem. 2019;287:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerga TM, Skouridou V, Bermudo MC, Bashammakh AS, El-Shahawi MS, Alyoubi AO, O’Sullivan CK. Gold nanoparticle aptamer assay for the determination of histamine in foodstuffs. Microchim Acta. 2020;187:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00604-020-04414-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Rothberg L. Colorimetric detection of DNA sequences based on electrostatic interactions with unmodified gold nanoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14036–14039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406115101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Rothberg LJ. Label-free colorimetric detection of specific sequences in genomic DNA amplified by the polymerase chain reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10958–10961. doi: 10.1021/ja048749n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Yu Z, Han X, Lai RY. Electrochemical aptamer-based sensors for food and water analysis: a review. Anal Chim Acta. 2019;1051:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2018.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wang Z, Sun L, Liu L, Xu C, Kuang H. Nanoparticle-based sensors for food contaminants. Trends Anal Chem. 2019;113:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2019.01.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Zhou Q, Tang D, Niessner R, Knopp D. Signal-on photoelectrochemical immunoassay for aflatoxin B1 based on enzymatic product-etching MnO2 nanosheets for dissociation of carbon dots. Anal Chem. 2017;89:5637–5645. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Lu Y. Fast colorimetric sensing of adenosine and cocaine based on a general sensor design involving aptamers and nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int. 2006;45:90–94. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Atwater M, Wang J, Huo Q. Extinction coefficient of gold nanoparticles with different sizes and different capping ligands. Colloids Surf B. 2007;58:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Cao Z, Lu Y. Functional nucleic acid sensors. Chem Rev. 2009;109:1948–1998. doi: 10.1021/cr030183i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Wang Z, Jiang X. Gold nanoparticles for the colorimetric and fluorescent detection of ions and small organic molecules. Nanoscale. 2011;3:1421–1433. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00887g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv S, Zhang K, Zhu L, Tang D. ZIF-8-assisted NaYF4:Yb, Tm@ZnO converter with exonuclease III-powered DNA walker for near-infrared light responsive biosensor. Anal Chem. 2019;92:1470–1476. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q, Wang Y, Jia J, Xiang Y. Colorimetric aptasensors for determination of tobramycin in milk and chicken eggs based on DNA and gold nanoparticles. Food Chem. 2018;249:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucic RC, Storhoff JJ, Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL. DNA-directed synthesis of binary nanoparticle network materials. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:12674–12675. doi: 10.1021/ja982721s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EM, Rothberg LJ. Kinetics and mechanism of single-stranded DNA adsorption onto citrate-stabilized gold nanoparticles in colloidal solution. Langmuir. 2011;27:1770–1777. doi: 10.1021/la102613f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimjee SM, Rusconi CP, Sullenger BA. Aptamers: an emerging class of therapeutics. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:555–583. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.062904.144915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrosa M, Boyano MT, García AC, Quirce S. Shellfish allergy: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;49:203–216. doi: 10.1007/s12016-014-8429-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phanchai W, Srikulwong U, Chompoosor A, Sakonsinsiri C, Puangmali T. Insight into the molecular mechanisms of AuNP-based aptasensor for colorimetric detection: a molecular dynamics approach. Langmuir. 2018;34:6161–6169. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b00701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado M, Ortea I, Vial S, Rivas J, Calo MP, Barros VJ. Advanced DNA-and protein-based methods for the detection and investigation of food allergens. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56:2511–2542. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2013.873767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priyadarshini E, Pradhan N. Gold nanoparticles as efficient sensors in colorimetric detection of toxic metal ions: a review. Sensor Actuat B Chem. 2017;238:888–902. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2016.06.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak K, Krazinski BE, Kowalczyk AE, Dworakowska B, Jakiela S, Stobiecka M. Optical biosensing system for the detection of survivin mRNA in colorectal cancer cells using a graphene oxide carrier-bound oligonucleotide molecular beacon. Nanomaterials. 2018;8:510. doi: 10.3390/nano8070510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak K, Lukasiak A, Grel H, Dworakowska B, Jakiela S, Stobiecka M. Monitoring of dynamic ATP level changes by oligomycin-modulated ATP synthase inhibition in SW480 cancer cells using fluorescent “On-Off” switching DNA aptamer. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2019;411:6899–6911. doi: 10.1007/s00216-019-02061-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren R, Cai G, Yu Z, Zeng Y, Tang D. Metal-polydopamine framework: an innovative signal-generation tag for colorimetric immunoassay. Anal Chem. 2018;90:11099–11105. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b03538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad M, Chinerman D, Tabrizian M, Faucher SP. Identification of two aptamers binding to Legionella pneumophila with high affinity and specificity. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-65973-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiki K, Oda H, Yoshioka H, Sakai S, Urisu A, Akiyama H, Ohno Y. A reliable and sensitive immunoassay for the determination of crustacean protein in processed foods. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:9345–9350. doi: 10.1021/jf0715471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q, Nie Z, Guo M, Zhong C-J, Lin B, Li W, Yao S. Simple and rapid colorimetric sensing of enzymatic cleavage and oxidative damage of single-stranded DNA with unmodified gold nanoparticles as indicator. Chem Commun. 2009;8:929–931. doi: 10.1039/b818081d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng Y-M, Liang J, Xie J. Indirect competitive determination of tetracycline residue in honey using an ultrasensitive gold-nanoparticle-linked aptamer assay. Molecules. 2020;25:2144. doi: 10.3390/molecules25092144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song SH, Gao ZF, Guo X, Chen GH. Aptamer-based detection methodology studies in food safety. Food Anal Methods. 2019;12:966–990. doi: 10.1007/s12161-019-01437-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S, Frankamp BL, Rotello VM. Controlled plasmon resonance of gold nanoparticles self-assembled with PAMAM dendrimers. Chem Mater. 2005;17:487–490. doi: 10.1021/cm048579d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stojanovic MN, Landry DW. Aptamer-based colorimetric probe for cocaine. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9678–9679. doi: 10.1021/ja0259483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su KH, Wei QH, Zhang X, Mock J, Smith DR, Schultz S. Interparticle coupling effects on plasmon resonances of nanogold particles. Nano Lett. 2003;3:1087–1090. doi: 10.1021/nl034197f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan R, Adams MC, Naik RR, Milam VT. Analyzing secondary structure patterns in DNA aptamers identified via CompELS. Molecules. 2019;24:1572. doi: 10.3390/molecules24081572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Lu J, Zhang L, Chen Z. Aptamer-based electrochemical cytosensors for tumor cell detection in cancer diagnosis: a review. Anal Chim Acta. 2019;1082:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2019.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Lu Y, He L, Pang J, Yang F, Liu Y. Colorimetric sensor array based on gold nanoparticles: design principles and recent advances. Trends Anal Chem. 2019;122:115754. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2019.115754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tapp MJ, Slocik JM, Dennis PB, Naik RR, Milam VT. Competition-enhanced ligand selection to identify DNA aptamers. ACS Comb Sci. 2018;20:585–593. doi: 10.1021/acscombsci.8b00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J. Aptamer-based colorimetric detection of various targets based on catalytic Au NPs/Graphene nanohybrids. Sens Biosens Res. 2019;22:100258. [Google Scholar]

- Unser S, Bruzas I, He J, Sagle L. Localized surface plasmon resonance biosensing: current challenges and approaches. Sensors. 2015;15:15684–15716. doi: 10.3390/s150715684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma HN, Singh P, Chavan R. Gold nanoparticle: synthesis and characterization. Vet World. 2014;7:72. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2014.72-77. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Liu X, Hu X, Song S, Fan C. Unmodified gold nanoparticles as a colorimetric probe for potassium DNA aptamers. Chem Commun. 2006;13:3780–3782. doi: 10.1039/b607448k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DP, Loo JFC, Chen JJ, Yam Y, Chen SC, He H, Kong SK, Ho HP. Recent advances in surface plasmon resonance imaging sensors. Sensors. 2019;19:1266. doi: 10.3390/s19061266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Sun Y, Zhao Q. A sensitive thrombin-linked sandwich immunoassay for protein targets using high affinity phosphorodithioate modified aptamer for thrombin labeling. Talanta. 2020;207:120280. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.120280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Li B, Li J, Wang E, Dong S. Simple and sensitive aptamer-based colorimetric sensing of protein using unmodified gold nanoparticle probes. Chem Commun. 2007;12:3735–3737. doi: 10.1039/b707642h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Chu H, Mei Z, Deng Y, Xue F, Zheng L, Chen W. Ultrasensitive one-step rapid detection of ochratoxin A by the folding-based electrochemical aptasensor. Anal Chim Acta. 2012;753:27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Dai B, Zhao W, Jiang L, Huang H. Electrochemical detection of β-lactoglobulin based on a highly selective DNA aptamer and flower-like Au@BiVO4 microspheres. Anal Chim Acta. 2020;1120:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2020.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao D, Li C, Wang H, Wen G, Liang A, Jiang Z. A new dual-mode SERS and RRS aptasensor for detecting trace organic molecules based on gold nanocluster-doped covalent-organic framework catalyst. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2020;319:128308. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2020.128308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Song Z, Peng J, Yang M, Zhi H, He H (2020) Progress of gold nanomaterials for colorimetric sensing based on different strategies. Trends Anal Chem 127: 115880

- Zhang H, Lu Y, Ushio H, Shiomi K. Development of sandwich ELISA for detection and quantification of invertebrate major allergen tropomyosin by a monoclonal antibody. Food Chem. 2014;150:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.10.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wu Q, Wei X, Zhang J, Mo S. DNA aptamer for use in a fluorescent assay for the shrimp allergen tropomyosin. Microchim Acta. 2017;184:633–639. doi: 10.1007/s00604-016-2042-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wu Q, Sun M, Zhang J, Mo S, Wang J, Wei X, Bai J. Magnetic-assisted aptamer-based fluorescent assay for allergen detection in food matrix. Sens Actuat B Chem. 2018;263:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2018.02.098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Belwal T, Li L, Lin X, Xu Y, Luo Z. Nanomaterial-based biosensors for sensing key foodborne pathogens: advances from recent decades. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2020;19:1465–1487. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Lu N, Zhang J, Yan R, Li J, Wang L, Wang N, Lv M, Zhang M. Ultrasensitive aptamer-based protein assays based on one-dimensional core-shell nanozymes. Biosens Bioelectron. 2020;150:111881. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2019.111881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W, Brook MA, Li Y. Design of gold nanoparticle-based colorimetric biosensing assays. Chem Bio Chem. 2008;9:2363–2371. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Wang Y, Yang X. Aptamer-based colorimetric biosensing of dopamine using unmodified gold nanoparticles. Sens Actuat B Chem. 2011;156:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2011.03.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Lang Y, Yu J, Han Z, Chen B, Wang Y. Affinity binding of aptamers to agarose with DNA tetrahedron for removal of hepatitis B virus surface antigen. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2019;178:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Tang D. Recent advances in photoelectrochemical biosensors for analysis of mycotoxins in food. Trends Anal Chem. 2020;124:115814. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2020.115814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Ai R, Weng J, Li L, Zhou C, Ma A, Fu L, Wang YA. A “on-off-on” fluorescence aptasensor using carbon quantum dots and graphene oxide for ultrasensitive detection of the major shellfish allergen Arginine kinase. Microchem J. 2020;158:105171. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2020.105171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.