Abstract

Mangroves comprise a globally significant intertidal ecosystem that contains a high diversity of microorganisms, including fungi, bacteria and archaea. Archaea is a major domain of life that plays important roles in biogeochemical cycles in these ecosystems. In this review, the potential roles of archaea in mangroves are briefly highlighted. Then, the diversity and metabolism of archaeal community of mangrove ecosystems across the world are summarized and Bathyarchaeota, Euryarchaeota, Thaumarchaeota, Woesearchaeota, and Lokiarchaeota are confirmed as the most abundant and ubiquitous archaeal groups. The metabolic potential of these archaeal groups indicates their important ecological function in carbon, nitrogen and sulfur cycling. Finally, some cultivation strategies that could be applied to uncultivated archaeal lineages from mangrove wetlands are suggested, including refinements to traditional cultivation methods based on genomic and transcriptomic information, and numerous innovative cultivation techniques such as single-cell isolation and high-throughput culturing (HTC). These cultivation strategies provide more opportunities to obtain previously uncultured archaea.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s42995-020-00081-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Archaea, Mangroves, Cultivation, Diversity, Metabolisms

Introduction

Mangroves are located in the tropical and subtropical coastal areas of the world. They provide ecological services such as maintaining biodiversity, improving water quality, and protecting coastlines. As one of the world’s most productive ecosystems, mangroves are characterized as an important “blue carbon” reservoir (Alongi 2014). Mangroves are located in a buffer zone connecting land and ocean, supporting relatively high microbial diversity and complex microbial communities (Moopantakath et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2019). Archaea, one of the most important microbial components, are widespread in mangrove ecosystems. In mangroves, the number of archaeal 16S rRNA genes ranges from 107 to 108 copies per gram of wet sediment (Li et al. 2012) and from 107 to 1010 copies per gram of dry sediment (Zhou et al. 2017). The cultivation-independent approaches, such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing and metagenomics, have revealed a high diversity and range of metabolisms in the archaea of mangroves (Bhattacharyya et al. 2015; Pan et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2019). Archaea have thus been proposed to play important roles in nutrient recycling in these ecosystems. However, only a few archaeal lineages have so far been isolated from mangroves and this impedes our understanding of the roles of archaea in these unique ecosystems.

Carl Woese proposed that archaea represented the third domain of life in parallel with bacteria and eukaryote more than 40 years ago (Woese 1990; Woese and Fox 1977). Since then, examinations of biochemical properties have found that archaea share some similarities with bacteria, such as lack of intracellular compartments (Londei 2005) but also have some shared traits with eukarya, such as the absence of peptidoglycan in the cell wall (Kandler and Hippe 1977) and the presence of multiple RNA polymerases (Zillig et al. 1985). Although the Woeseian three-domain tree hypothesis has been adopted as the major theory for the universal tree of life for many years, the debate has always been accompanied by the “eocyte tree hypothesis” (Lake 1988, 1990; Lake et al. 1984), especially because of the discovery of Asgard archaea in recent years, which are proposed to be the closest prokaryotic relatives of eukaryotes (Spang et al. 2015; Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka et al. 2017). Originally, archaea were discovered and described from extreme environments, e.g., hot spring (Hua et al. 2019), hydrothermal vents (Anantharaman et al. 2016), acid mine drainage (Kuang et al. 2013), and highly saline lakes (Sorokin et al. 2017). The development of high-throughput sequencing techniques facilitates the investigation of archaeal diversity. Now it has been recognized that various archaea are distributed globally, e.g., in freshwater, seawater, soils and sediments (Adam et al. 2017; Zhou et al. 2018, 2019).

Our understanding of archaeal diversity has been expanded in recent years due to the discovery of many novel archaeal lineages that have changed the shape of the phylogenetic tree of archaea (Spang et al. 2017). Since 1990, Euryarchaeota and Crenarchaeota had been recognized as the only two phyla. However, more recently, high-throughput sequencing, metagenomics assembly and binning have revealed many new archaeal phyla, based on the phylogenetic and genomic analyses. Until recently, with the exception of Euryarchaeota, three superphyla have been recognized: TACK, DPANN, and Asgard (Spang et al. 2017). The number of archaeal phyla has been expanded from the original two phyla to at least 27 phyla now (Baker et al. 2020), ushering in a new era of archaeal research.

In this review, we first briefly summarize the potential roles of archaea from mangrove ecosystems and then focus on the diversity, metabolism and cultivation of the archaea from these wetlands. We aim to enhance understanding of archaeal diversity and provide cultivation strategies for particular lineage of archaea from mangroves.

The potential roles of archaea in mangrove ecosystems

Mangroves are present in the tropical and subtropical coastal areas of 112 countries and territories. Together they comprise an area of 0.11–0.24 million km2 that extend over a quarter of the world’s coastline (Nellemann et al. 2009). Mangrove ecosystems contain complex environments that have been formed under the influence of tides, the influx of fresh water, high temperature and high humidity (Sahoo and Dhal 2009). The sediments are characteristically anoxic, rich in organic matter and provide eutrophic and brackish environments for a number of archaeal communities (Zhang et al. 2019). Mangroves are also one of the most productive ecosystems in the world and are characterized by high nutrient turnover rates. The diverse archaeal communities living in mangroves are also likely to play crucial roles in global biogeochemical cycles (Sahoo and Dhal 2009). For example, Euryarchaeota are involved in the production and oxidation of methane, a potent greenhouse gas (Taketani et al. 2010b). Ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) in Thaumarchaeota are responsible for ammonia oxidation (Li et al. 2011). Bathyarchaeota and Asgard archaea may be involved in nitrite and sulfur reduction (Cai et al. 2020; Pan et al. 2020). The high rates of organic matter input and low rates of decomposition also contribute to carbon accumulation in mangroves (McKee 2011). Bathyarchaeota and Asgard archaea may play an important role in the degradation of multiple types of organic matters in mangroves (Cai et al. 2020; Pan et al. 2020). Also, Thorarchaeota might be involved in detoxification of arsenic (Liu et al. 2018). Furthermore, archaea possibly have a relationship with the geochemical transformation of iron (Fe) and manganese (Mn) in mangrove sediments (Otero et al. 2014). According to function prediction, archaea are also likely to be important in thiosulfate respiration, sulfur compounds respiration and aerobic chemoheterotrophy in mangroves (Marie Booth et al. 2019).

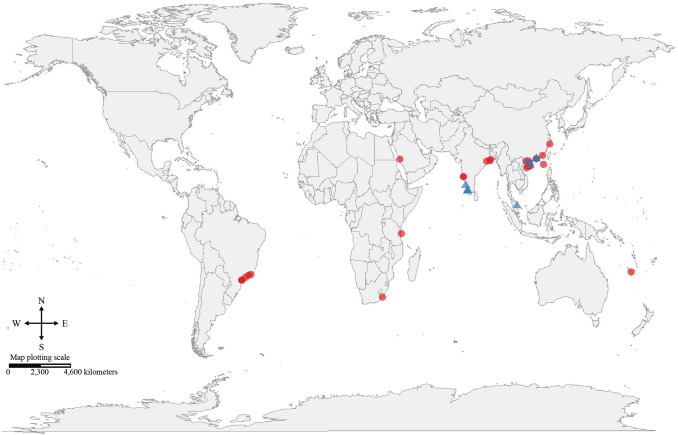

Archaea is an important microbiological component of sediments in mangrove wetlands. They are generally more abundant in deeper sediment layers, with relative abundances ranging from 20.8% to 41.3% of the 16S rRNA gene sequences of prokaryotic communities in mangroves (Luis et al. 2019). The 16S rRNA gene sequence-based approaches and metagenomics have revealed the high diversity of archaea in mangrove sediments. To clearly illustrate the diversity and relative abundance of archaea in mangroves, we undertook a search of 24 studies to identify the archaeal community and metabolic potentials in mangroves across the world (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). The detailed methods are listed in Supplementary Information.

Fig. 1.

Locations of the mangrove sites that obtained from the 24 studies. The sites with 16S sequence data are in red (26 sites), while the sites with Illumina HiSeq data are in blue (9 sites)

Diversity and distribution of archaea in mangrove wetlands

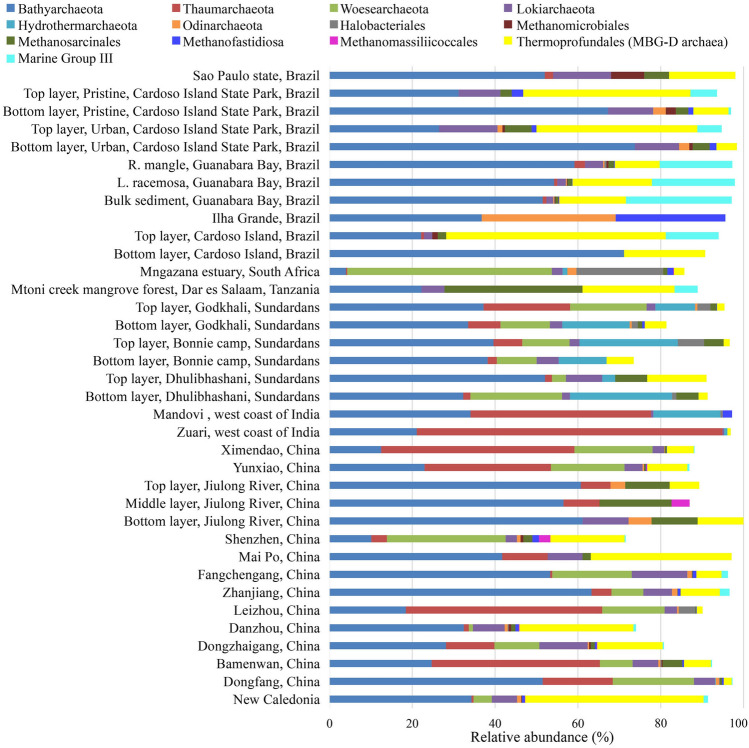

According to the 16S rRNA gene sequence data analysis, the most abundant archaeal groups in mangroves are Bathyarchaeota, Euryarchaeota, Thaumarchaeota, Woesearchaeota and Lokiarchaeota (Fig. 2). Bathyarchaeota, the most dominant archaeal phylum, is widely distributed in sediments of mangroves, accounting for an average of 39.8% of the total archaea (Fig. 2). Previous studies have shown that Bathyarchaeota comprised more than 70% of archaea in the bottom sediment layer of the Cardoso Island State Park, Brazil (Mendes et al. 2012; Otero et al. 2014). Bathyarchaeota occupied about 60% of the total archaea in the Jiulong River, China (Li et al. 2012). Kubo et al. (2012) conducted a comprehensive analysis of the biogeographical distribution of Bathyarchaeota and found that it was the dominant archaeal population in anoxic, low-activity subsurface sediments. So far, based on 16S rRNA gene analysis, 25 subgroups of Bathyarchaeota have been proposed; these subgroups are likely to have different strategies to adapt to the marine and freshwater environments (Zhou et al. 2018). For examples, subgroups 6, 8, 15, and 17 were the major Bathyarchaeotal subgroups in Shenzhen Futian Mangrove Nature Reserve, China (Pan et al. 2019).

Fig. 2.

Archaeal community composition in mangrove ecosystems of different sites. Only taxa that represent > 5% of the relative abundance in at least one site are represented. Minor phyla that represent < 5% of the relative abundance in all sites are not shown

In Euryarchaeota, Thermoprofundales (Marine Benthic Group D, MBG-D), Methanosarcinales, Marine Group III, and Methanofastidiosales were the most abundant orders, representing 13.4%, 3.7%, 2.8%, and 1.2% of the total archaea, respectively (Fig. 2). Thermoprofundales is one of the most frequently encountered archaeal lineages with a widespread distribution and high abundance (Zhou et al. 2019). For example, Thermoprofundales reached 5–53% of the total archaea in the sediment layer of Cardoso Island, Brazil (Mendes et al. 2012; Otero et al. 2014). Thermoprofundales encountered for 43% of the total archaea in sediments of New Caledonia (Luis et al. 2019). Methanogens are also one of the most important groups from the phylum Euryarchaeota. Multiple methanogenic lineages have been identified in mangrove sediments, including Methanobacteriales, Methanocellales, Methanofastidiosa, Methanosarcinales, Methanomicrobiales, and Methanomassiliicoccales (Zhang et al. 2020a). Methanobacteria, Methanococci, and Methanomicrobia represented 5%, 8%, and 35% of the total archaea in Kerala (India), respectively (Imchen et al. 2017). It has been reported that salinity was the major environmental factor regulating the methanogenic community assemblage and different methanogens occupied different niches (Zhang et al. 2020b). Methanococcoides, Methanoculleus, and Methanogenium preferentially existed in saline sediments, whereas Methanomethylovorans, Methanolinea, Methanoregula and Methanomassiliicoccales were more abundant in freshwater-oligohaline sediments (Zhang et al. 2020b).

Thaumarchaeota is one of the most abundant and cosmopolitan phyla in mangrove sediments, accounting for 1–74% of the total archaea (Fig. 2). It is the most abundant phylum (44–74%) on the west coast of India (Singh et al. 2010). Thaumarchaeota is also the dominant phylum in surface sediments of mangroves in Sundarbans (Bhattacharyya et al. 2015). Since Thaumarchaeota are aerobic archaea, they are considerably more abundant in oxic environments and oxic/anoxic interface zones than in the corresponding subsurface samples at the same sampling site (Zhou et al. 2017).

Woesearchaeota is abundant in mangrove sediments in some particular sites, e.g., in the mangrove sediments of Daya Bay (China), and Dongzhaigang (China), accounting for 10–27% of the total archaea (Li et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2018). Lokiarchaeota, formerly named MBG-B (Marine Benthic Group B) and DSAG (Deep Sea Archaeal Group), are also important components of mangrove sediments, accounting for 2–15% of the total archaea (Fig. 2). It has been detected in sediments in the Gulf of Mexico, Bamenwan (China), Shenzhen Futian Natural Reserve (China) and Hong Kong Mai Po wetland (China) (Devereux et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2019; Zhou et al. 2017). As with Bathyarchaeota, Lokiarchaeota are more abundant at greater depths within the sediments than in surface layers. Notably, Hydrothermarchaeota comprised 3–23% of total archaea in the Sundardans area (Bhattacharyya et al. 2015) and Odinarchaeota comprised 32% of total archaea in Ilha Grande, Brazil (Silveira et al. 2013), respectively.

The community composition of archaea showed distinct patterns at different sites. Mangrove archaeal communities were found to change with geographic location, which might be driven by a variety of environmental variables (etc., pH and carbon and nitrogen contents) (Li et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2019). The community composition of archaea at the same site is also dependent on environmental properties such as silt–clay percentage, amount of organic matter and pH (Colares and Melo 2013; Zhou et al. 2017).

Mangrove archaeal communities might also be influenced by factors such as anthropogenic activities, including oil spills, municipal and industrial discharge and shrimp farming (Bhattacharyya et al. 2015; Dias et al. 2011; Taketani et al. 2010a). Mangrove sediments with these contaminants show an increase in the organic carbon content, which leads to alteration of the archaeal community composition. Halobacteriales from the Euryarchaeota was found to be the predominant group in hydrocarbon-polluted mangrove sediments (Mukherji et al. 2020). The release of municipal and aquaculture sewage upstream from estuaries might also promote the growth of Methanosarcinaceae and enhance methane production in mangroves (Zhao et al. 2019).

Depth is another important factor structuring archaeal communities in mangrove sediments, principally driven by oxic state of the sediments (Li et al. 2012; Zhou et al. 2017). Thaumarchaeota and Euryarchaeota predominate in surface sediments, while Bathyarchaeota and Lokiarchaeota dominate in subsurface sediments (Luis et al. 2019; Zhou et al. 2017). Previous study has shown that Bathyarchaeota accounted for 1.6% of total prokaryotic sequences in surface sediments, while it increased to 26% of total 16S rRNA gene sequences of prokaryotic communities in deep layers (Luis et al. 2019).

Mangrove trees may also affect archaeal diversity and composition, as there is extensive nutrient exchange between mangrove plants and various archaeal groups (Li et al. 2016; Pires et al. 2012). Previous studies have shown that the abundance of Methanobacteriales and Methanosarcinaceae was significantly higher in mangrove sediments than in the non-mangrove sediments (Zhao et al. 2019).

Metabolic potentials of archaea in mangrove wetlands

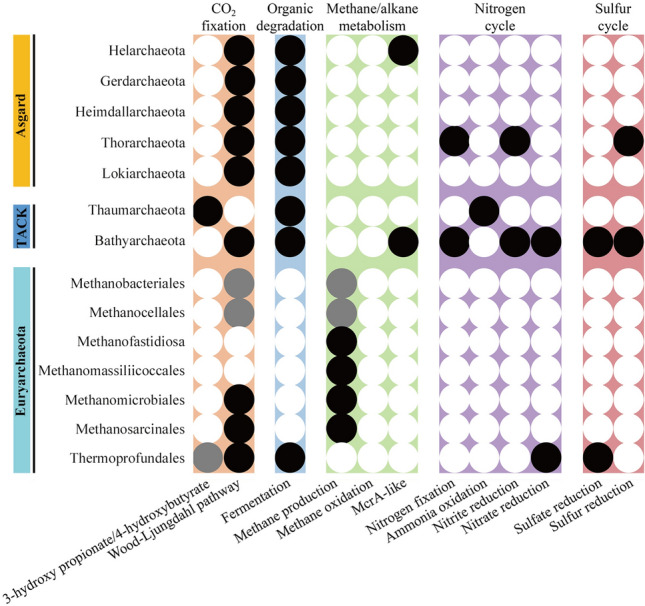

Recently, metagenomics techniques have obtained many metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) of archaea. The MAGs of archaea, recovered from mangrove ecosystems, revealed special metabolic potentials in carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycling, indicating important ecological functions of archaea in mangrove ecosystems (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S2).

Fig. 3.

Archaeal metabolic potentials in mangrove ecosystems. Ecological roles of archaeal lineages in carbon, nitrogen and sulfur cycles based on physiological and genomic information. Black, grey and white circles indicate complete, incomplete and absent pathways, respectively

Multiple archaeal lineages have potential to fix inorganic carbon. Metabolic reconstruction revealed that Thermoprofundales, Bathyarchaeota, Lokiarchaeota, Thorarchaeota, Gerdarchaeota and Helarchaeota, identified from mangroves, have the genetic potential for inorganic carbon fixation via the archaeal Wood-Ljundahl (WL) pathway (Cai et al. 2020; He et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2018; Pan et al. 2020; Sousa et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2019). Analysis of MAGs showed that Thermoprofundales might also encode an incomplete 3-hydroxy propionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle to fix CO2 (Zhou et al. 2019). Recently, the presence of genes for rhodopsins, cobalamin biosynthesis, and the oxygen-dependent metabolic pathways in some Bathyarchaeota subgroup 6 genomes suggest a light-sensing and microoxic lifestyle within this subgroup (Pan et al. 2020).

Mangrove ecosystems contain a large number of organic carbon compounds, including carbohydrates, amino acids, and lipids (Alongi 2014). Previous researches have shown that almost all archaeal groups are predicted to degrade organic carbon into fermentation byproducts (Baker et al. 2020; Li et al. 2015). Thermoprofundales, Bathyarchaeota, Lokiarchaeota, and Thorarchaeota are hypothesized to have a heterotrophic lifestyle. Thermoprofundales are able to transport and assimilate peptides and generate acetate and ethanol through fermentation (Zhou et al. 2019). Several studies have suggested that Bathyarchaeota is capable of utilizing a variety of organic matter types, including cellulose, chitin, aromatic compounds, and fatty acids (He et al. 2016; Lazar et al. 2016; Lloyd et al. 2013; Meng et al. 2014). Lokiarchaeota, Thorarchaeota, and Gerdarchaeota in the Asgard superphylum are hypothesized to be not strictly autotrophic but might also participate in the degradation of organic carbon in mangroves (Cai et al. 2020). The prevalence and high relative abundance of Thermoprofundales, Bathyarchaeota, and Lokiarchaeota indicate that they may contribute to the turnover of organic matter in mangrove ecosystems.

Euryarchaeota undertake methane production, anaerobic methane oxidation and anaerobic oxidation of other short-chain alkanes (i.e., ethane and butane) (Borrel et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2019; Laso-Perez et al. 2019; Lyu et al. 2018). Mangrove sediments are usually muddy, anoxic, and have a high organic carbon content, which is a suitable habitat for methanogens. Sequencing of 16S rRNA genes, metagenomics, and metatranscriptomics has shown that hydrogenotrophic Methanomicrobiales, and H2-dependent methylotrophic Methanomassiliicoccales were highly abundant and active, suggesting that these methanogenic pathways contribute the most to methane emission in mangroves (Xiao et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2020a). MAGs annotations have revealed that methanogens contain genes encoding organic osmotic solute transporters to adapt to the high salinity of mangrove environments. Hydrogenotrophic Methanomicrobiales MAGs encoded multiple membrane-bound hydrogenases and a large number of electron transporters, which is favorable for their adaption to low substrate (H2) environments (Zhang et al. 2020a). Methanomassiliicoccales MAGs contain genes encoding substrate-specific methyltransferases for multiple methylated compounds including methanethiol, methanol, and trimethylamine (TMA) (Zhang et al. 2020a). Methanol can be produced by degradation of lignin or pectin (Lyimo et al. 2009). Methylated amines can be formed from decomposition of choline and glycine betaine, which are osmolytes produced by many marine organisms to cope with osmotic stress. These methylated compounds are not easily utilized by sulfidogenic bacteria, but they can be rapidly fermented by methanogens to methane (Jones et al. 2019). In addition, methyl-coenzyme M reductase (McrA)-like transcripts have been found in Helarchaeota, indicating that Helarchaeota might be involved in short-chain alkane oxidation in mangroves, where ethane and butane originate from oil–gas seepage or human activities (Cai et al. 2020).

Multiple archaea are involved in the global nitrogen cycle. In mangrove ecosystems, AOA in Thaumarchaeota contain the ammonia monooxygenase gene (amoA) that can oxidize ammonia to nitrite (Li et al. 2011). Bathyarchaeotal and Thorarchaeotal genomes contain the nitrogenase iron protein gene (nifH) for nitrogen fixation, indicating that they can use nitrogen to synthesize ammonia (Liu et al. 2018; Pan et al. 2020). Thorarchaeota contain the nitrite reductase gene (nirB) that coverts nitrite to ammonia (Liu et al. 2018). There is genomic evidence that Bathyarchaeota contains the nitrate reductase gene (narH), the nitrite reductase gene (nirB) and mono/di/trimethylamine aminotransferase genes (mttB/mtbB/mtmB), suggesting Bathyarchaeota can utilize diverse nitrogen compounds to produce ammonium and then convert ammonium to urea (Pan et al. 2020). It has been reported that Thermoprofundales contains nitrate reductase genes (nar), suggesting they might participate in the initial step of denitrification (Zhou et al. 2019). The above results indicate that archaea may play an important role in the global nitrogen cycle.

Archaeal MAGs also contain sulfur cycle related genes. Sulfate concentration has previously been reported to range from 1.23 to 3.61 g/kg of dry sediment in mangroves (Wu et al. 2019). Sulfate reduction genes (sat) and phosphoadenosine phosphosulfate reductase (cysC), that participate in the first two steps of assimilatory sulfate reduction, reducing sulfate to sulfite through adenylyl-sulfate, can be identified in MAGs of Bathyarchaeota and Thermoprofundales, suggesting they probably depend on sulfate assimilation (Pan et al. 2020; Zhou et al. 2019, 2018). Furthermore, Bathyarchaeota and Thorarchaeota contain the hydrogenase/sulfur reductase gene (hydA) to reduce S to sulfide (Liu et al. 2018; Pan et al. 2020). All of these results indicate the role of archaea in the global sulfur cycle. In addition, annotation of Thorarchaeota MAGs reveals that they are involved in arsenic detoxification, suggesting that they could be applied to bioremediation of As-contaminated sediment or water (Liu et al. 2018).

Archaeal isolation from mangrove sediments

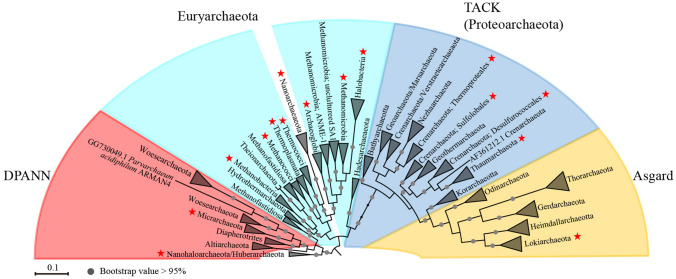

Cultivation-independent approaches provide a great many insights into the diversity, ecology, and metabolism of archaea. However, only seven phyla (i.e., Euryarchaeota, Crenarchaeota, Thaumarchaeota, Nanoarchaeota, Nanohaloarchaeota, Micrarchaeota, and Lokiarchaeota) have been isolated and cultured, while the other archaeal phyla have not yet been cultured (Baker et al. 2020). Euryarchaeota contains the most isolates, including members in the classes Archaeoglobi (Hartzell and Reed 2006), Halobacteria (Oren 2006), Thermococci (Bertoldo and Antranikian 2006; Zhao et al. 2015), Thermoplasmata (Huber and Stetter 2006a), as well as methanogens in the class Methanobacteria (Bonin and Boone 2006), Methanococci (Whitman and Jeanthon 2006), Methanopyri, Methanomicrobia (Garcia et al. 2006; Kendall and Boone 2006). In recent decades, the class Methanonatronarchaeia and the order Methanomassiliicoccales in the class Thermoplasmata have also been isolated (Dridi et al. 2012; Sorokin et al. 2017). There are pure cultures of three orders of the class Thermoprotei within the phylum Crenarchaeota, including Thermoproteales (Huber et al. 2006b), Sulfolobales (Huber and Prangishvili 2006c), and Desulfurococcales (Huber and Stetter 2006d). In Thaumarchaeota, Nitrosopumilus maritimus SCM1 has been isolated from a marine aquarium (Konneke et al. 2005). A few members of the Nanoarchaeota (Huber et al. 2002, 2006e; Wurch et al. 2016), Nanohaloarchaeota (Hamm et al. 2019), and Micrarchaeota (Krause et al. 2017) are co-cultured with their hosts. In the Asgard superphylum, a co-culture of a Lokiarchaeota, named as Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum MK-D1, and one methanogen Methanogenium has recently been obtained from deep marine sediments (Imachi et al. 2020). No pure cultures of Bathyarchaeota have so far been successfully established. Recently, Bathyarchaeota subgroup 8 has been enriched from estuarine sediments in a consortium using lignin as an energy source (Yu et al. 2018). Here, we present an overview of the 16S rRNA gene-based phylogenetic tree of archaea with cultured archaeal lineages marked with red five-pointed stars (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table S3), which indicates the demand for isolates of the underexplored groups. Figure 4 was adapted from Sun et al. (2019) and supplemented with new published data (Cai et al. 2020; Jay et al. 2018; Probst et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2019).

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic tree based on archaeal 16S rRNA gene sequences. Those with red five-pointed stars are groups that have cultivated members. Figure 4 was adapted from Sun et al. (2019) and supplemented with new published data (Cai et al. 2020; Jay et al. 2018; Probst et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2019). The phylogeny was generated with 1002 archaeal 16S rRNA gene sequences whose length longer than 660 bp using FastTree. Bootstraps are based on 1000 replicated trees. The alignment was generated with MUSCLE. Helarchaeota in the Asgard superphylum was not included in the phylogenetic tree, since there was no Helarchaeotal 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained from MAGs or references

Nitrogen-fixing bacteria, phosphate solubilizing bacteria, and sulfate-reducing bacteria (e.g., Bacillales, Actinomycetales, Vibrionales) and fungi (e.g., Pestalotipsis foedans, Fusarium solani) have been isolated from mangrove environments (Sahoo and Dhal 2009). However, there have been few isolations of archaea from mangroves (Supplementary Table S4). A few methylotrophic methanogens have been isolated and cultured from mangrove sediments. For example, Methanolacinia paynteri was isolated from the mangrove swamps located in the Cayman Islands (Rivard et al. 1983). Methanococcoides methylutens, which grew on trimethylamine (TMA) and methanol, was isolated and characterized from the mangrove sediments of Southeast India (Mobanraju et al. 1997). Methanosarcina semesiae was isolated from mangrove sediments in Tanzania (Lyimo et al. 2000). A mesophilic methylotrophic methanogenic archaeon Methanococcoides strain MM1 was isolated from mangrove sediments in Tanzania, which was capable of utilizing methanol and methylated amines as the only substrates (Lyimo et al. 2009). Mangroves at some sites are strongly affected by anthropogenic activities and disturbances. Haloarchaea are extremophiles surviving in extreme salinities and are involved in bioremediation of contaminations. Two major haloarchaeal genera Haloferax and Haladaptatus have recently been successfully isolated form hydrocarbon polluted mangrove sediments in Sundarban area, which could be used to reduce the chemical oxygen demand (COD) of polluted mangrove sediments (Mukherji et al. 2020).

Future cultivation strategies and suggestions for mangrove archaea

Obtaining pure cultures remains a priority for microbial ecological studies. For example, pure cultures are essential for a comprehensive understanding of the physiology and biochemistry of microbes and offer solid evidence for their ecological functions. Pure cultures enable the discovery of functionally important products such as new antibiotics and other secondary metabolites (Zhao et al. 2019). Nearly all existing archaeal strains were isolated and described more than ten years ago and only a few novel strains have been pure cultured using traditional enrichment and isolation methods, such as single colony picking and serial dilution-to-extinction, within the last ten years. There are several reasons why traditional archaeal cultivation methods have reached a plateau (Sun et al. 2019). Firstly, many archaea, such as the DPANN superphylum, may be symbionts or have interactions with other microbial species and so they cannot be isolated as single strains (Moissl-Eichinger et al. 2017). Secondly, the slow growth rates and low abundances of archaea also make them difficult to culture. Thirdly, limited knowledge of archaeal metabolisms impedes the establishment of suitable culture media and growth conditions for isolation.

In the recent decades, exciting progress has been made in cultivation techniques. There are two major strategies that could be taken advantage of for future archaeal isolation. The first strategy is the refinement of conventional cultivation processes based on genetic and transcriptomic information. When strains are enriched or cultivated, metagenomic and transcriptional data can be used as guidelines for selecting culture media and growth conditions (Laso-Perez et al. 2018). For example, a reconstruction of the metabolism of Bathyarchaeota, Thermoprofundales, and Asgard archaea predicts their substrate preferences for organic matter (Cai et al. 2020; Pan et al. 2020; Zhou et al. 2019). Mangrove sediments are typically rich in organic matter. Bathyarchaeota, Thermoprofundales and Lokiarchaeota are abundant in mangroves. Hence, a variety of organic compounds (such as amino acid, peptide, lipid, lignin) could be added as substrates to enrich and culture Bathyarchaeota, Thermoprofundales and Lokiarchaeota from mangroves. Genome-guided isolation could be also applied to the culture of methylotrophic methanogens. Methanogenesis is a dominant terminal processes in the degradation of organic matter in mangroves (Lyimo et al. 2009). According to genome annotation, Methanosarcinales, Methanofastidiosa, and Methanomassiliicoccales are able to utilize methylotrophic compounds (methanol, methanethiol, and trimethylamine) as substrates for methanogenesis (Zhang et al. 2020a). Therefore, a variety of methylated compounds could be added as substrates to enrich and culture methylotrophic methanogens. Sulfate is available and sulfate reduction predominates in mangroves. Archaea involved in sulfate reduction, such as Bathyarchaeota and Thermoprofundales, could be a target for isolation (Pan et al. 2020; Zhou et al. 2019). Furthermore, co-occurrence networks are used to analyze potential interactions and seek “key node” microbes in a microbial communities (Xian et al. 2020). Co-cultures of Rice Cluster I with propionate-oxidizing H2-producing bacterium and Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum MK-D1 with Methanogenium are two successful examples for microbial interaction (Imachi et al. 2020; Sakai et al. 2008). Co-occurrence networks in mangroves have shown that methanogens have significant non-random association with Woesearchaeota (Zhang et al. 2020a). Above all, specific substrate or co-culture microbes can be added to promote the growth of target archaea based on guidance from genomic information and co-occurrence analysis.

For the second strategy, numerous innovative culture techniques have been applied to microbial cultivation, such as single cell isolation using microfluidics (Boitard et al. 2015; Kaminski et al. 2016), capillary tube, encapsulation techniques, optical and raman tweezers (Park and Chiou 2011), and high-throughput cultivation (HTC) methods such as Microtite plates (MTP), a Million-Well Growth Chip (Hesselman et al. 2012; Ingham et al. 2007) and culturomics (Lagier et al. 2012). Single cell isolation, which is different from traditional “first culture then isolate” method, mainly includes three steps: (1) separate single cells, (2) detect the target cell, and (3) obtain pure culture of the cell. Optical tweezers, one of the single cell isolation techniques, has been successfully used for the isolation of the DPANN archaea Nanoarchaeota (Wurch et al. 2016). Raman-Activated Droplet Sorting (RADS), another single cell isolation technique, can achieve a higher throughput, preserve the vitality of cells and facilitate downstream single-cell cultivation (Wang et al. 2017). High-throughput cultivation means that microbes are indiscriminately isolated using a variety of culture media (Mu et al. 2018). Substrate concentrations in each well are three orders of magnitude lower than those in common laboratory media, which is suitable for growth of oligotrophic archaea (Welte 2018). These innovative methods show great potential for the isolation and culture of single archaeal cell from mix microbial community in mangroves.

Outlook

Mangroves are a unique coastal ecosystem that provides a wide range of microbial resources. Recent culture-independent and culture-dependent studies have revealed the large diversity and important potential functions of archaea in biogeochemical cycles in mangroves. Additional understanding of the taxonomy and metabolic potential of archaea will come from future genomic interpretation. However, there is still a need for more studies on archaea isolation and cultivation to verify their physiological and ecological roles. Using both refined traditional isolation methods and innovative isolation techniques, more previously uncultivable archaea will be successful cultivated or enriched in future. This will open the door for the enhancement of our understanding of archaeal ecological process and evolution.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 91851105, 31970105, 31622002, and 42007217), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (grant no. JCYJ20170818091727570 and KQTD20180412181334790), the Key Project of Department of Education of Guangdong Province (grant no. 2017KZDXM071), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (no. 2018M630977), the CAS Interdisciplinary Innovation Team (grant No. JCTD-2018-16).

Author contributions

ML provided the idea and revised the manuscript. C-JZ collected and analyzed data with help from Y-LC, Y-HS, JP and M-WC. C-JZ contributed in preparing the manuscript with the help of all authors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Animal and human rights statement

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

SPECIAL TOPIC: Cultivation of uncultured microorganisms.

Edited by Chengchao Chen.

References

- Adam PS, Borrel G, Brochier-Armanet C, Gribaldo S. The growing tree of Archaea: new perspectives on their diversity, evolution and ecology. ISME J. 2017;11:1–9. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alongi DM. Carbon cycling and storage in mangrove forests. Ann Rev Mar Sci. 2014;6:195–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010213-135020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharaman K, Breier JA, Dick GJ. Metagenomic resolution of microbial functions in deep-sea hydrothermal plumes across the Eastern Lau Spreading Center. ISME J. 2016;10:225–239. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BJ, De Anda V, Seitz KW, Dombrowski N, Santoro AE, Lloyd KG. Diversity, ecology and evolution of Archaea. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:887–900. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0715-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoldo C, Antranikian G (2006) The order thermococcales. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer KH, Stackebrandt E (eds) The Prokaryotes. Springer, New York, pp 69–81

- Bhattacharyya A, Majumder NS, Basak P, Mukherji S, Roy D, Nag S, Haldar A, Chattopadhyay D, Mitra S, Bhattacharyya M, Ghosh A. Diversity and distribution of Archaea in the mangrove sediment of Sundarbans. Archaea. 2015;2015:968582. doi: 10.1155/2015/968582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boitard L, Cottinet D, Bremond N, Baudry J, Bibette J. Growing microbes in millifluidic droplets. Eng Life Sci. 2015;15:318–326. [Google Scholar]

- Bonin AS, Boone DR. The order Methanobacteriales. Prokaryotes. 2006;3:231–243. [Google Scholar]

- Borrel G, Adam PS, McKay LJ, Chen LX, Sierra-Garcia IN, Sieber CMK, Letourneur Q, Ghozlane A, Andersen GL, Li WJ, Hallam SJ, Muyzer G, de Oliveira VM, Inskeep WP, Banfield JF, Gribaldo S. Wide diversity of methane and short-chain alkane metabolisms in uncultured archaea. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:603–613. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0363-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai M, Liu Y, Xiuran Y, Zhou Z, Friedrich MW, Richter-Heitmann T, Nimzyk R, Kulkarni A, Wang X, Li W, Pan J, Yang Y, Gu J-D, Li M. Diverse Asgard archaea including the novel phylum Gerdarchaeota participate in organic matter degradation. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63:886–897. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1679-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SC, Musat N, Lechtenfeld OJ, Paschke H, Schmidt M, Said N, Popp D, Calabrese F, Stryhanyuk H, Jaekel U, Zhu YG, Joye SB, Richnow HH, Widdel F, Musat F. Anaerobic oxidation of ethane by archaea from a marine hydrocarbon seep. Nature. 2019;568:108–111. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colares GB, Melo VMM. Relating microbial community structure and environmental variables in mangrove sediments inside Rhizophora mangle L. habitats. Appl Soil Ecol. 2013;64:171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Devereux R, Mosher JJ, Vishnivetskaya TA, Brown SD, Beddick DL, Yates DF, Palumbo AV. Changes in northern Gulf of Mexico sediment bacterial and archaeal communities exposed to hypoxia. Geobiology. 2015;13:478–493. doi: 10.1111/gbi.12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias ACF, Dini-Andreote F, Taketani RG, Tsai SM, Azevedo JL, de Melo IS, Andreote FD. Archaeal communities in the sediments of three contrasting mangroves. J Soils Sediments. 2011;11:1466–1476. [Google Scholar]

- Dridi B, Fardeau ML, Ollivier B, Raoult D, Drancourt M. Methanomassiliicoccus luminyensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a methanogenic archaeon isolated from human faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62:1902–1907. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.033712-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia J-L, Ollivier B, Whitman WB. The order Methanomicrobiales. Prokaryotes. 2006;3:208–230. [Google Scholar]

- Hamm JN, Erdmann S, Eloe-Fadrosh EA, Angeloni A, Zhong L, Brownlee C, Williams TJ, Barton K, Carswell S, Smith MA, Brazendale S, Hancock AM, Allen MA, Raftery MJ, Cavicchioli R. Unexpected host dependency of Antarctic Nanohaloarchaeota. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:14661–14670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905179116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell P, Reed DW (2006) The genus archaeoglobus. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer KH, Stackebrandt E (eds) The prokaryotes. Springer, New York, pp 82–100

- He Y, Li M, Perumal V, Feng X, Fang J, Xie J, Sievert SM, Wang F. Genomic and enzymatic evidence for acetogenesis among multiple lineages of the archaeal phylum Bathyarchaeota widespread in marine sediments. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16035. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselman MC, Odoni DI, Ryback BM, de Groot S, van Heck RG, Keijsers J, Kolkman P, Nieuwenhuijse D, van Nuland YM, Sebus E, Spee R, de Vries H, Wapenaar MT, Ingham CJ, Schroen K, Martins dos Santos VA, Spaans SK, Hugenholtz F, van Passel MW. A multi-platform flow device for microbial (co-) cultivation and microscopic analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Z-S, Wang Y-L, Evans PN, Qu Y-N, Goh KM, Rao Y-Z, Qi Y-L, Li Y-X, Huang M-J, Jiao J-Y, Chen Y-T, Mao Y-P, Shu W-S, Hozzein W, Hedlund BP, Tyson GW, Zhang T, Li W-J. Insights into the ecological roles and evolution of methyl-coenzyme M reductase-containing hot spring Archaea. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4574. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12574-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber H, Hohn MJ, Rachel R, Fuchs T, Wimmer VC, Stetter KO. A new phylum of Archaea represented by a nanosized hyperthermophilic symbiont. Nature. 2002;417:63–67. doi: 10.1038/417063a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber H, Stetter KO (2006a) Thermoplasmatales. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer KH, Stackebrandt E (eds) The Prokaryotes. Springer, New York, pp 101–112

- Huber H, Huber R, Stetter KO (2006b) Thermoproteales. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer KH, Stackebrandt E (eds) The Prokaryotes. Springer, New York, pp 10–22

- Huber H, Prangishvili D (2006c) Sulfolobales. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer KH, Stackebrandt E (eds) The Prokaryotes. Springer, New York, pp 23–51

- Huber H, Stetter KO (2006d) Desulfurococcales. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer KH, Stackebrandt E (eds) The Prokaryotes. Springer, New York, pp 22–68

- Huber H, Hohn MJ, Rachel R, Stetter KO (2006e) Nanoarchaeota. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer KH, Stackebrandt E (eds) The Prokaryotes. Springer, New York, pp 274–280

- Imachi H, Nobu MK, Nakahara N, Morono Y, Ogawara M, Takaki Y, Takano Y, Uematsu K, Ikuta T, Ito M, Matsui Y, Miyazaki M, Murata K, Saito Y, Sakai S, Song C, Tasumi E, Yamanaka Y, Yamaguchi T, Kamagata Y, et al. Isolation of an archaeon at the prokaryote–eukaryote interface. Nature. 2020;577:519–525. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1916-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imchen M, Kumavath R, Barh D, Avezedo V, Ghosh P, Viana M, Wattam AR. Searching for signatures across microbial communities: Metagenomic analysis of soil samples from mangrove and other ecosystems. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8859. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09254-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham CJ, Sprenkels A, Bomer J, Molenaar D, van den Berg A, van Hylckama Vlieg JE, de Vos WM. The micro-Petri dish, a million-well growth chip for the culture and high-throughput screening of microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18217–18222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701693104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay ZJ, Beam JP, Dlakić M, Rusch DB, Kozubal MA, Inskeep WP. Marsarchaeota are an aerobic archaeal lineage abundant in geothermal iron oxide microbial mats. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:732–740. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HJ, Krober E, Stephenson J, Mausz MA, Jameson E, Millard A, Purdy KJ, Chen Y. A new family of uncultivated bacteria involved in methanogenesis from the ubiquitous osmolyte glycine betaine in coastal saltmarsh sediments. Microbiome. 2019;7:120. doi: 10.1186/s40168-019-0732-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski T, Scheler O, Garstecki P. Droplet microfluidics for microbiology: techniques, applications and challenges. Lab Chip. 2016;16:2168–2187. doi: 10.1039/c6lc00367b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandler O, Hippe H. Lack of peptidoglycan in the cellwalls of Methanosarcina barkeri. Arch Microbiol. 1977;113:57–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00428580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall MM, Boone DR. The order Methanosarcinales. Prokaryotes. 2006;3:244–256. [Google Scholar]

- Konneke M, Bernhard AE, de la Torre JR, Walker CB, Waterbury JB, Stahl DA. Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon. Nature. 2005;437:543–546. doi: 10.1038/nature03911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause S, Bremges A, Munch PC, McHardy AC, Gescher J. Characterisation of a stable laboratory co-culture of acidophilic nanoorganisms. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3289. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03315-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang JL, Huang LN, Chen LX, Hua ZS, Li SJ, Hu M, Li JT, Shu WS. Contemporary environmental variation determines microbial diversity patterns in acid mine drainage. ISME J. 2013;7:1038–1050. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo K, Lloyd KG, Biddle JF, Amann R, Teske A, Knittel K. Archaea of the Miscellaneous Crenarchaeotal Group are abundant, diverse and widespread in marine sediments. ISME J. 2012;6:1949–1965. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagier J-C, Armougom F, Million M, Hugon P, Pagnier I, Robert C, Bittar F, Fournous G, Gimenez G, Maraninchi M, Trape J-F, Koonin EV, Scola BL, Raoult D. Microbial culturomics: paradigm shift in the human gut microbiome study. Clin Microbiol Infec. 2012;18:1185–1193. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake JA. Origin of the eukaryotic nucleus determined by rate-invariant analysis of rRNA sequences. Nature. 1988;331:184–186. doi: 10.1038/331184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake JA. Archaebacterial or eocyte tree? Nature. 1990;343:418–419. [Google Scholar]

- Lake JA, Henderson E, Oakes M, Clark MW. Eocytes: a new ribosome structure indicates a kingdom with a close relationship to eukaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:3786–3790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.12.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laso-Perez R, Hahn C, van Vliet DM, Tegetmeyer HE, Schubotz F, Smit NT, Pape T, Sahling H, Bohrmann G, Boetius A, Knittel K, Wegener G (2019) Anaerobic degradation of non-methane alkanes by "Candidatus Methanoliparia" in hydrocarbon seeps of the Gulf of Mexico. mBio 10: e01814–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Laso-Perez R, Krukenberg V, Musat F, Wegener G. Establishing anaerobic hydrocarbon-degrading enrichment cultures of microorganisms under strictly anoxic conditions. Nat Protoc. 2018;13:1310–1330. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2018.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar CS, Baker BJ, Seitz K, Hyde AS, Dick GJ, Hinrichs KU, Teske AP. Genomic evidence for distinct carbon substrate preferences and ecological niches of Bathyarchaeota in estuarine sediments. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:1200–1211. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Cao H, Hong Y, Gu JD. Spatial distribution and abundances of ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) in mangrove sediments. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;89:1243–1254. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2929-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Wang F, Chen Z, Yin X, Xiao X. Stratified active archaeal communities in the sediments of Jiulong River estuary. China Front Microbiol. 2012;3:311. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Baker BJ, Anantharaman K, Jain S, Breier JA, Dick GJ. Genomic and transcriptomic evidence for scavenging of diverse organic compounds by widespread deep-sea archaea. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8933. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Guan W, Chen H, Liao B, Hu J, Peng C, Rui J, Tian J, Zhu D, He Y. Archaeal communities in the sediments of different mangrove stands at Dongzhaigang, China. J Soil Sediment. 2016;16:1995–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Tong T, Wu S, Chai M, Xie S. Multiple factors govern the biogeographic distribution of archaeal community in mangroves across China. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2019;231:106414. [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Huang H, Bao S, Tong Y. Microbial community structure of soils in Bamenwan mangrove wetland. Sci Rep. 2019;9:8406. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44788-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhou Z, Pan J, Baker BJ, Gu JD, Li M. Comparative genomic inference suggests mixotrophic lifestyle for Thorarchaeota. ISME J. 2018;12:1021–1031. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0060-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd KG, Schreiber L, Petersen DG, Kjeldsen KU, Lever MA, Steen AD, Stepanauskas R, Richter M, Kleindienst S, Lenk S, Schramm A, Jorgensen BB. Predominant archaea in marine sediments degrade detrital proteins. Nature. 2013;496:215–218. doi: 10.1038/nature12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londei P. Evolution of translational initiation: new insights from the archaea. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:185–200. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luis P, Saint-Genis G, Vallon L, Bourgeois C, Bruto M, Marchand C, Record E, Hugoni M. Contrasted ecological niches shape fungal and prokaryotic community structure in mangroves sediments. Environ Microbiol. 2019;21:1407–1424. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyimo TJ, Pol A, Jetten MS, den Camp HJ. Diversity of methanogenic archaea in a mangrove sediment and isolation of a new Methanococcoides strain. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;291:247–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyimo TJ, Pol A, den Camp HJMO, Harhangi HR, Vogels GD. Methanosarcina semesiae sp. nov., a dimethylsulfide-utilizing methanogen from mangrove sediment. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:171–178. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-1-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu Z, Shao N, Akinyemi T, Whitman WB. Methanogenesis. Curr Biol. 2018;28:727–732. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie Booth J, Fusi M, Marasco R, Michoud G, Fodelianakis S, Merlino G, Daffonchio D. The role of fungi in heterogeneous sediment microbial networks. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7537. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43980-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee KL. Biophysical controls on accretion and elevation change in Caribbean mangrove ecosystems. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2011;91:475–483. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes LW, Taketani RG, Navarrete AA, Tsai SM. Shifts in phylogenetic diversity of archaeal communities in mangrove sediments at different sites and depths in southeastern Brazil. Res Microbiol. 2012;163:366–377. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng J, Xu J, Qin D, He Y, Xiao X, Wang F. Genetic and functional properties of uncultivated MCG archaea assessed by metagenome and gene expression analyses. ISME J. 2014;8:650–659. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobanraju R, Rajagopal BS, Daniels L, Natarajan R. Isolation and characterization of a methanogenic bacterium from mangrove sediments. J Mar Biotechnol. 1997;5:147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Moissl-Eichinger C, Pausan M, Taffner J, Berg G, Bang C, Schmitz RA. Archaea are interactive components of complex microbiomes. Trends Microbiol. 2017;26:70–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moopantakath J, Imchen M, Siddhardha B, Kumavath R. 16s rRNA metagenomic analysis reveals predominance of Crtl and CruF genes in Arabian Sea coast of India. Sci Total Environ. 2020;743:140699. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu DS, Liang QY, Wang XM, Lu DC, Shi MJ, Chen GJ, Du ZJ. Metatranscriptomic and comparative genomic insights into resuscitation mechanisms during enrichment culturing. Microbiome. 2018;6:230. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0613-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherji S, Ghosh A, Bhattacharyya C, Mallick I, Bhattacharyya A, Mitra S, Ghosh A. Molecular and culture-based surveys of metabolically active hydrocarbon-degrading archaeal communities in Sundarban mangrove sediments. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;195:110481. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nellemann C, Corcoran E, Duarte CM, Valdés L, De Young C, Fonseca L, Grimsditch G. Blue carbon. United Nations Environment Programme: A rapid response assessment; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Oren A. The order Halobacteriales. Prokaryotes. 2006;3:113–164. [Google Scholar]

- Otero XL, Lucheta AR, Ferreira TO, Huerta-Díaz MA, Lambais MR. Archaeal diversity and the extent of iron and manganese pyritization in sediments from a tropical mangrove creek (Cardoso Island, Brazil) Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2014;146:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, Chen Y, Wang Y, Zhou Z, Li M. Vertical distribution of Bathyarchaeotal communities in mangrove wetlands suggests distinct niche preference of Bathyarchaeota subgroup 6. Microb Ecol. 2019;77:417–428. doi: 10.1007/s00248-018-1309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, Zhou Z, Beja O, Cai M, Yang Y, Liu Y, Gu JD, Li M. Genomic and transcriptomic evidence of light-sensing, porphyrin biosynthesis, Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle, and urea production in Bathyarchaeota. Microbiome. 2020;8:43. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00820-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S-Y, Chiou P-Y. Light-driven droplet manipulation technologies for lab-on-a-chip applications. Adv OptoElectron. 2011;2011:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Pires AC, Cleary DF, Almeida A, Cunha A, Dealtry S, Mendonca-Hagler LC, Smalla K, Gomes NC. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and barcoded pyrosequencing reveal unprecedented archaeal diversity in mangrove sediment and rhizosphere samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:5520–5528. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00386-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst AJ, Ladd B, Jarett JK, Geller-McGrath DE, Sieber CMK, Emerson JB, Anantharaman K, Thomas BC, Malmstrom RR, Stieglmeier M, Klingl A, Woyke T, Ryan MC, Banfield JF. Differential depth distribution of microbial function and putative symbionts through sediment-hosted aquifers in the deep terrestrial subsurface. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:328–336. doi: 10.1038/s41564-017-0098-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivard CJ, Henson JM, Thomas MV, Smith PH. Isolation and characterization of Methanomicrobium paynteri sp. nov., a mesophilic methanogen isolated from marine sediments. Appl Environ Microb. 1983;46:484–490. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.2.484-490.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo K, Dhal NK. Potential microbial diversity in mangrove ecosystems: A review. Indian J Mar Sci. 2009;38:249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai S, Imachi H, Hanada S, Ohashi A, Harada H, Kamagata Y. Methanocella paludicola gen. nov., sp. nov., a methane-producing archaeon, the first isolate of the lineage 'Rice Cluster I', and proposal of the new archaeal order Methanocellales ord. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008;58:929–936. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65571-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira CB, Cardoso AM, Coutinho FH, Lima JL, Pinto LH, Albano RM, Clementino MM, Martins OB, Vieira RP. Tropical aquatic Archaea show environment-specific community composition. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e76321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SK, Verma P, Ramaiah N, Chandrashekar AA, Shouche YS. Phylogenetic diversity of archaeal 16S rRNA and ammonia monooxygenase genes from tropical estuarine sediments on the central west coast of India. Res Microbiol. 2010;161:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin DY, Makarova KS, Abbas B, Ferrer M, Golyshin PN, Galinski EA, Ciordia S, Mena MC, Merkel AY, Wolf YI, van Loosdrecht MCM, Koonin EV. Discovery of extremely halophilic, methyl-reducing euryarchaea provides insights into the evolutionary origin of methanogenesis. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17081. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa FL, Neukirchen S, Allen JF, Lane N, Martin WF. Lokiarchaeon is hydrogen dependent. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16034. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spang A, Caceres EF, Ettema TJG. Genomic exploration of the diversity, ecology, and evolution of the archaeal domain of life. Science. 2017;357:eaaf3883. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spang A, Saw JH, Jorgensen SL, Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka K, Martijn J, Lind AE, van Eijk R, Schleper C, Guy L, Ettema TJ. Complex archaea that bridge the gap between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Nature. 2015;521:173–179. doi: 10.1038/nature14447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Liu Y, Pan J, Wang F, Li M. Perspectives on cultivation strategies of Archaea. Microb Ecol. 2019;79:770–784. doi: 10.1007/s00248-019-01422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taketani RG, Franco NO, Rosado AS, van Elsas JD. Microbial community response to a simulated hydrocarbon spill in mangrove sediments. J Microbiol. 2010;48:7–15. doi: 10.1007/s12275-009-0147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taketani RG, Yoshiura CA, Dias AC, Andreote FD, Tsai SM. Diversity and identification of methanogenic archaea and sulphate-reducing bacteria in sediments from a pristine tropical mangrove. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2010;97:401–411. doi: 10.1007/s10482-010-9422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Ren L, Su Y, Ji Y, Liu Y, Li C, Li X, Zhang Y, Wang W, Hu Q, Han D, Xu J, Ma B. Raman-activated droplet sorting (RADS) for label-free high-throughput screening of microalgal single-cells. Anal Chem. 2017;89:12569–12577. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b03884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wegener G, Hou J, Wang F, Xiao X. Expanding anaerobic alkane metabolism in the domain of Archaea. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:595–602. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welte CU. Revival of Archaeal methane microbiology. mSystems. 2018;3:e00181–e217. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00181-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman WB, Jeanthon C. Methanococcales. Prokaryotes. 2006;3:257–273. [Google Scholar]

- Woese CR. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woese CR, Fox GE. Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: The primary kingdoms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5088–5090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.11.5088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Li R, Xie S, Shi C. Depth-related change of sulfate-reducing bacteria community in mangrove sediments: The influence of heavy metal contamination. Mar Pollut Bull. 2019;140:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurch L, Giannone RJ, Belisle BS, Swift C, Utturkar S, Hettich RL, Reysenbach AL, Podar M. Genomics-informed isolation and characterization of a symbiotic Nanoarchaeota system from a terrestrial geothermal environment. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12115. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian W-D, Salam N, Li M-M, Zhou E-M, Yin Y-R, Liu Z-T, Ming Y-Z, Zhang X-T, Wu G, Liu L, Xiao M, Jiang H-C, Li W-J. Network-directed efficient isolation of previously uncultivated Chloroflexi and related bacteria in hot spring microbial mats. NPJ Biofilms Microbiom. 2020;6:20. doi: 10.1038/s41522-020-0131-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao KQ, Beulig F, Kjeldsen KU, Jorgensen BB, Risgaard-Petersen N. Concurrent methane production and oxidation in surface sediment from Aarhus Bay Denmark. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1198. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T, Wu W, Liang W, Lever MA, Hinrichs K-U, Wang F. Growth of sedimentary Bathyarchaeota on lignin as an energy source. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:6022–6027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718854115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka K, Caceres EF, Saw JH, Backstrom D, Juzokaite L, Vancaester E, Seitz KW, Anantharaman K, Starnawski P, Kjeldsen KU, Stott MB, Nunoura T, Banfield JF, Schramm A, Baker BJ, Spang A, Ettema TJ. Asgard archaea illuminate the origin of eukaryotic cellular complexity. Nature. 2017;541:353–358. doi: 10.1038/nature21031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Hu BX, Ren H, Zhang J. Composition and functional diversity of microbial community across a mangrove-inhabited mudflat as revealed by 16S rDNA gene sequences. Sci Total Environ. 2018;633:518–528. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CJ, Pan J, Duan CH, Wang YM, Liu Y, Sun J, Zhou HC, Song X, Li M (2019) Prokaryotic diversity in mangrove sediments across Southeastern China fundamentally differs from that in other biomes. mSystems 4:e00442–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang C-J, Pan J, Liu Y, Duan C-H, Li M. Genomic and transcriptomic insights into methanogenesis potential of novel methanogens from mangrove sediments. Microbiome. 2020;8:94. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00876-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang CJ, Chen YL, Pan J, Wang YM, Li M. Spatial and seasonal variation of methanogenic community in a river-bay system in South China. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;104:4593–4603. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-10613-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Yan B, Mo S, Nie S, Li Q, Ou Q, Wu B, Jiang G, Tang J, Li N, Jiang C. Carbohydrate metabolism genes dominant in a subtropical marine mangrove ecosystem revealed by metagenomics analysis. J Microbiol. 2019;57:575–586. doi: 10.1007/s12275-019-8679-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W, Zeng X, Xiao X. Thermococcus eurythermalis sp. nov., a conditional piezophilic, hyperthermophilic archaeon with a wide temperature range for growth, isolated from an oil-immersed chimney in the Guaymas Basin. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65:30–35. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.067942-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Liu Y, Lloyd KG, Pan J, Yang Y, Gu JD, Li M. Genomic and transcriptomic insights into the ecology and metabolism of benthic archaeal cosmopolitan, Thermoprofundales (MBG-D archaea) ISME J. 2019;13:885–901. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0321-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Meng H, Liu Y, Gu JD, Li M. Stratified bacterial and archaeal community in mangrove and intertidal wetland mudflats revealed by high throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2148. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Pan J, Wang F, Gu JD, Li M. Bathyarchaeota: globally distributed metabolic generalists in anoxic environments. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2018;42:639–655. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuy023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zillig W, Stetter K, Schnabel R, Thomm M. DNA-dependent RNA polymerases of the Archaebacteria. In: Woese CR, Wolfe RS, editors. The Bacteria. New York: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 499–524. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.