Abstract

Aim

To explore factors that influence registered nurses' intention to stay working in the healthcare sector.

Design

A systematic review and narrative synthesis.

Methods

CINAHL, Medline and Cochrane library databases were searched from Jan 2010 to Jan 2022 inclusive and research selected using a structured criterion, quality appraisal and data extraction and synthesis were guided by Campbell's Synthesis Without Meta‐analysis.

Results

Thirty‐four studies identified that nurses stay if they have job satisfaction and/or if they are committed to their organizations. The factors permeating these constructs weigh differently through generations and while not an infallible explanation, demonstrate stark differences in workplace needs by age, which influence the intention to stay, job satisfaction, organizational commitment and ultimately nurse turnover.

Public Contribution

Environmental, relational and individual factors have bearing on improving nurse satisfaction and commitment. Understanding why nurses stay through a generational behavioural and career stage lens can bolster safeguarding nurse retention.

Keywords: intention to stay, nurse retention, systematic review, turnover

1. INTRODUCTION

In 2020, the global nursing workforce totalled 27.9 million, with an estimated vacancy position of 5.9 million (World Health Organization, 2020). Nurses account for almost 50% of the global healthcare workforce and their deficits pose the single biggest challenge for many healthcare systems. Nursing workforce shortages have far‐reaching and cumulative impacts on patient ratios, staff dissatisfaction, occupational stress and burnout and staff retention to the ultimate detriment of patient safety and quality of care (Aiken & Fagin, 2018). What is lesser appreciated, is by what means employers can safeguard and protect nurses already working within our healthcare systems to stay (Kelly et al., 2022; Shembavnekar et al., 2022).

Many compounding reasons for healthcare workforce shortages created a challenge pre‐Covid‐19 pandemic which has successively significantly exacerbated this existing global problem. The stark situational reality is that the demand for nurses is putting demand on nurses, by increasing workloads and pressures (Buchan et al., 2022). Buchan argues that workforce deficits within themselves perpetuate a cyclical chain of events, corroding nurses experience at work and thus negatively impacting retention. The consequences of working in physically and emotionally draining environments are likely to be only the tip of the iceberg, propositioning, a continuing aggregating threat to the sustainability of nursing populations (Kelly et al., 2022; Shembavnekar et al., 2022).

For every nurse that leaves there is a detrimental impact on the working experiences of nurses who remain when job pressures and workloads increase. Nurse leavers are also commercially costly due to the loss of productivity from having a skilled worker and logistical expenses of replacing employees. It is suggested that the financial impact of nurse leavers is hard to quantify yet replacing one nurse alone is said to exceed an annual salary, with totals rising the longer a vacancy remains unfilled (Oxford Economics, 2014). This issue is of spiralling concern as there is presently insufficient replenishing stocks to replace leavers, meaning the effect on a nurse's experience of work and the impacting costs are predicted to grow (Buchan et al., 2022).

With the shortage of nurses worldwide forecast to surpass 9 million by 2030, it is imperative to consider the global patterns of our nursing population. It is calculated that one out of six nurses is expected to retire in the next 10 years, and therefore to match leavers with joiners, while simultaneously filling the existing vacancy position, nurse graduates must increase by an average of 8% per year up until 2030 (State of the World's Nursing (SOWN), 2020). Balancing the inflows of stock from domestic nursing programmes with outflows such as nurse graduates who fail to maintain employment, nurses who decide to work outside the health sector, retirements and migration abroad suggests a challenge that exceeds the sole reliance on replenishing stocks (Ryan et al., 2019; State of the World's Nursing (SOWN), 2020).

It is seemingly evermore improbable that globally, we will be able to recruit into fixing the nursing workforce problem, and it is suggested that one part of the solution lies in retaining nurses already working within our healthcare systems. It is propositioned that significant gains to the nursing workforce are in the main, achievable through the implementation of effective strategies to retain existing staff and that nurse retention is the critical factor in counterbalancing the demand–supply equation (Sherman, 2014; Theucksuban et al., 2022; Van den Heede et al., 2013). Thus, there is an urgency to understand how to improve nurse retention to realise a turning point and support more nurses to stay (World Health Organization (WHO), 2020).

1.1. Background

Historically, the fulcrum of inquiry into workforce shortages has explored determinants of why nurses leave (Buchan et al., 2022; Shembavnekar et al., 2022). The concept of retention is complex and multidimensional and is, itself, as suggested, a major determining factor in nurse turnover. Turnover can be explained as both leaving one healthcare position for another or leaving healthcare altogether. Seminal work defined ‘intention to stay’ as the nurse's perception of their likelihood of staying in their current job or the stated probability of staying with the current organization (McCloskey & McCain, 1987). Chen, Perng, et al. (2016) and Cowden and Cummings (2012) argue that ‘intention to stay’ is a strong predictor of retention, yet the concept has perhaps until recently attracted limited attention. ‘Why nurses leave’ and ‘why nurses stay’ are not mutually exclusive domains; they clearly interlock and should be investigated as part of a single paradigm accordingly (Lee et al., 2019). That said, how these fundamental concepts are interpreted by employers must be independently considered. Much is known about the regressive lag indicators and corrosive factors that cause intention to leave, which in up to 80% of cases can result in actual leavers (Applebaum et al., 2010; Kagwe et al., 2019; Perry et al., 2018), and yet there is limited insight into the forward‐looking indicators of why nurses stay and the potential of the positive impact on turnover. For that reason, while ever these factors remain undefined nurse retention is not being approached from a solution‐focused perspective (Kelly et al., 2022; Theucksuban et al., 2022); a seemingly missed opportunity in the face of the reality of the brittle global nurse workforce position.

The ultimate aim is for healthcare systems worldwide to improve self‐sufficiency in balancing growing nurse demand with nurse supply, and yet this is seemingly evermore unattainable while ever the challenges caused by growing pressures are in themselves making the problem greater (Buchan et al., 2022). Market forces dictate when demand outstrips supply, the value of the commodity increases (Sherman, 2014). When nurses are in demand, they can move easily within the labour market in search of better terms and conditions as they are the consumers, this means if nurses do not have their workplace needs met they can leave or move between healthcare providers at liberty (Cowden & Cummings, 2012). This behaviour causes intensifying disruption to an already challenged system, and therefore understanding and supporting staff to stay, will realise marginal gains, which in turn will increase productivity and moderate demand (Moscelli et al., 2022). Hence the corollary; if we change stance from exploring attrition from the perspective of salient antecedent ‘push’ factors that cause nurses to leave, such as burnout and other factors causing dissatisfaction (Flinkman et al., 2008), to explore the determinant ‘pull’ factors of why nurses stay, we can strategically target safeguarding the working experiences of nurses and positively influence the global nursing workforce position by improving retention (Sherman, 2014).

2. THE REVIEW

2.1. Aim

The aim of this literature review is to systematically explore factors that influence registered nurses' intention to stay working in the health and care sector.

The specific objectives structuring the review are

to determine individual components that positively impact a nurses experience at work

to understand the contemporary motivations and challenges of nurses intention to stay

to develop a nurse retention framework to inform workforce retention strategies

2.2. Design

The design is a systematic review and narrative synthesis in accordance with guidelines for Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (Moher et al., 2008; PRISMA Statement, Moher et al., 2015). This design was chosen because a synthesis of evidence using meta‐analysis presented a challenge as the review objectives are multifactorial. In addition, topical studies revealed extensive heterogeneity not only in the range of factors under assessment but also in the definition of the criterion with many studies using proxy measures such as job satisfaction which represented an interim step towards the aim of establishing causality.

2.3. Search methods

Searches were conducted to identify research using key search terms in the CINAHL, Medline and Cochrane Library databases. The search terms were selected and piloted by the research team with the aid of an information technologist. The final search was undertaken and included research accepted for publication from January 2010 to January 2022.

The agreed search terms were as follows:

Why OR inten** OR reason

AND

nurs** OR nurse OR nursing

AND

stay** OR continu**

There are many small samples, single‐site studies exploring nurse retention. To be confident in the replicability and reliability of new knowledge, research papers were selected for full review if they met the following inclusion criteria: peer‐reviewed research, published in the English language, with outcomes from instruments specifically measuring nurses' intention to stay or factors contributing to nursing intention to stay, including nurses working in any international health or social care setting (see Table 1). To augment consistency, the review included any study methodology using a quantitative design and represented by Cronbach's α value of >0.7. Mixed method studies focussed on qualitative synthesis, and fully qualitative studies were excluded. Further exclusions included studies that focused on why nurses leave. Studies of Student Nurses, Nursing Associates, Midwives and Allied Health Professionals were also excluded.

TABLE 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

|

|

|

|

2.4. Search outcome

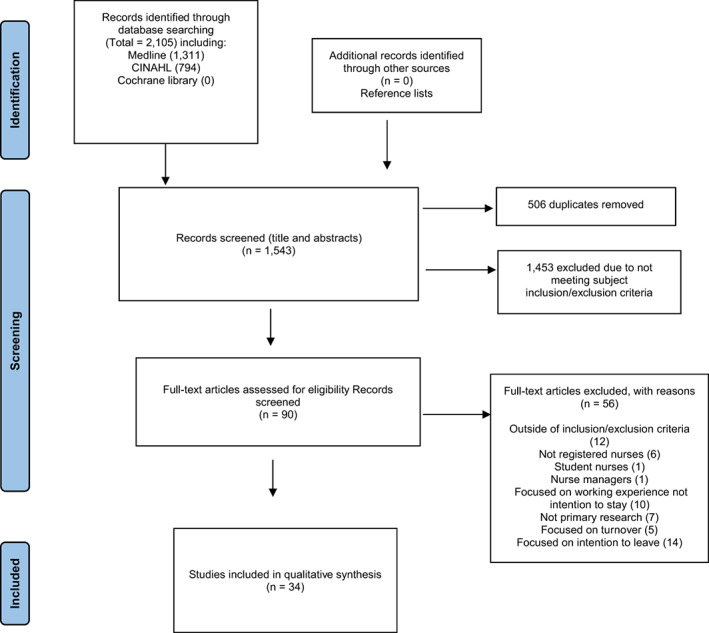

Searches led to 2105 articles found; after duplicates were removed, 1543 remained and were screened by abstract and title (Figure 1). After applying eligibility criteria to the abstract and title, a further 1453 articles were excluded leaving a total of 90 articles for full‐text review. Following full‐text review, a further 56 were excluded, leaving 34 articles for inclusion in the analysis (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

The search strategy in full (SNR)

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Author, year and country | Design | Sample size | NICE | Measurement/Cronbach's α scores | Categories | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AbuAlRub et al., 2012. Jordan | Descriptive correlation design | 381 | ++/++ |

Safety climate Teamwork Leadership style ITS |

Strong correlation between safety climate and teamwork. Moderate correlation between safety climate and ITS and teamwork and ITS. Findings weighted by age and years of experience. Nurses with 10 years plus experience have higher perceptions of safety climate than nurses who had 1–3 years of experience. Older nurse ITS is greater than younger nurses. | |

| AbuAlRub & Alghamdi, 2012. Jordan | Descriptive correlation design | 308 | ++/++ |

Job satisfaction Leadership style |

Weak positive correlation with leadership styles and ITS. Increased satisfaction with transformational leadership styles. | |

| AbuAlRub & Nasrallah, 2017. Jordan | Descriptive correlation design | 295 | ++/++ |

Transformational leadership Organizational culture ITS |

Strong positive correlation between organizational culture and the level of intent to stay at work. Transformational leadership styles enhance positive hospital culture and improve the intention to stay working. | |

| Al‐Hamdan et al., 2016. Jordan | Cross‐sectional survey | 362 | ++/++ |

Conflict management styles ITS |

Integrative, obliging or avoiding conflict management styles have moderate to high ITS. Poor conflict management affects staff retention and morale. Weighted by age and years of experience. Older and/or more experienced nurses are more likely to stay due to seniority and fixed working patterns | |

| Al‐Hamdan et al., 2017. Jordan | Cross‐sectional survey | 650 | ++/++ |

Job satisfaction Work environment ITS |

Significant correlation between job satisfaction and work environment. Policymakers should be encouraged to take action to improve working conditions for nurses. | |

| Al‐Hamdan et al., 2019. Jordan | Cross‐sectional survey | 280 | ++/++ |

Emotional intelligence ITS |

Emotional intelligence is significantly correlated with ITS. Higher levels of emotional intelligence are strongly associated with lower burnout and stress levels among nurses. Findings are weighted by age, marital status and qualification status. Nurses aged over 30 years tended to report greater ITS. | |

| Atiyeh & AbuAlRub, 2017. Jordan | Cross‐sectional survey | 268 | ++/++ |

|

Leadership Trust ITS |

If trust increases ITS increases |

| Borhani et al., 2014. Iran | Cross‐sectional survey | 220 | ++/++ |

Moral distress Professional stress ITS |

There was a significant correlation between moral distress professional stress and age, number of years in service and work setting. Neutral correlation between moral distress and professional stress and ITS which was explained due to external environmental constraints preventing nurses from leaving. | |

| Brewer et al., 2016. USA | Cross‐sectional 10‐year longitudinal panel design | 1037 | ++/++ |

Organizational commitment ITS Job satisfaction Transformational leadership |

Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, mentor support, promotional opportunities and age, positively associated with ITS Leaders can retain nurses by creating a positive work environment |

|

| Chen, Perng, et al., 2016. Taiwan | Cross‐sectional survey | 1246 | ++/++ |

|

Work values Personality traits ITS |

ITS links to personality traits. Nurses with conscientiousness and emotional stability had a high intention to stay. There is a significant but weak correlation between ITS and age. Senior and experienced nurses had greater ITS. |

| Chen, Ho, et al., 2016. Taiwan | Cross‐sectional survey | 791 | ++/++ |

Organizational‐based self‐esteem Job satisfaction Social support ITS |

ITS increased with enhanced social support and Organizational Based Self Esteem Social support and job satisfaction showed a positive effect on ITS |

|

| Chenoweth et al., 2014. Australia | Cross‐sectional survey | 3983 | ++/++ |

|

Job satisfaction | Work satisfaction levels are higher for 50 years and over at 85%, and 35–49 years at 68% and 35 years and under 22% |

| Dechawatanapaisal, 2018. Thailand | Cross‐sectional survey | 1966 | ++/++ |

Leader–member exchange Job embeddedness |

There is a direct relationship between leader–member exchange quality and job embeddedness Job embeddedness mitigates turnover intention, increasing ITS |

|

| Eltaybani et al., 2018 | Cross‐sectional survey | 3385 | ++/++ |

Intention to stay Burnout Engagement Somatic Symptom Burden |

ITS is positively associated with nurses’ age, manager support, perceived quality of care, educational opportunities, work environment, speciality and pay. | |

| Gellatly et al., 2014. Canada | Cross‐sectional survey | 336 | ++/++ |

|

Nurse commitment Work relationships |

High continuous commitment in combination with highly effective and normative commitment has a positive effect on ITS |

| Gholami et al., 2019. Iran | Cross‐sectional survey | 160 | ++/++ |

Job empowerment Trust Organizational commitment |

Significant and meaningful correlation between perception of job empowerment, organizational commitment and trust. |

|

| Hewko et al., 2015. Canada | Web survey | 95 | ++/++ |

|

Workload Patient care Resources Empowerment Recognition |

Managers intending to leave reported significantly lower job satisfaction, higher burnout and lower satisfaction with their supervisors. The most important factor reported by managers intending to stay was work–life balance followed by support from their immediate supervisor, the ability to ensure the quality of care, empowerment and job security. |

| Jiang et al., 2017. Shanghai | Cross‐sectional survey | 976 | ++/++ |

|

Job satisfaction Burnout ITS |

Nurse satisfaction is a protective factor of intention to leave. Burnout (emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation) were risk factors for leaving. A significant difference between age, work experience and ITS. |

| Kerzman et al., 2020. Israel | Matching case–control study and Survey | 300 | ++/++ |

Qualification status Autonomy Career aspiration Working conditions |

Leavers had lower levels of autonomy and higher aspirations for professional advancement. Less experience and higher stress have a higher intent to leave. Newly qualified have higher levels of stress and lower satisfaction. Staying nurses had lower educational qualifications, higher autonomy and greater seniority. Distance from work, working conditions and professional development were reasons for leaving. | |

| Larrabee et al., 2010. USA | Predictive non‐experimental survey | 464 | ++/++ |

|

Stress resilience Psychological empowerment Job satisfaction ITS |

Job satisfaction is a major predictor of ITS. Job stress and psychological empowerment are predictors of job satisfaction. Nurses over 30 are significantly more likely to stay than nurses younger than 30 years. ITS correlated with age, years since qualifying and education |

| Lee et al., 2019. Korea | Cross‐sectional survey | 267 | ++/++ |

Organizational commitment Burnout ITS |

Organizational commitment, practice environment and burnout influence the intention to leave. Organizational commitment influences ITS. Intention to leave was higher in nurses aged 26–40 than in those aged 41 and over. Higher also in lower education levels, working in a non‐specialist area and those reporting as areligious. | |

| Li et al., 2020. China | Cross‐sectional survey | 3252 | ++/++ |

Support Job control Job satisfaction ITS |

Job control, perceived organizational support and job satisfaction, significantly and directly affect ITS. | |

| Liang et al., 2016. Taiwan | Survey | 414 | ++/++ |

|

Nurse characteristics Leadership characteristics Safety climate Emotional Labour ITS |

Positive correlation between safety climate and emotional labour. Emotional labour and safety climate mediate ITS. Leadership characteristics indirectly affect ITS. Transformational leadership directly influences the safety climate and safety climate mediates ITS. ITS positively correlates with age. |

| Lin et al., 2011. Taiwan | Cross‐sectional survey | 524 | ++/++ |

|

Practice environment ITS |

Work environment is a predominant factor in ITS. Manager support, peer support, unit support and a manageable workload increase the intention to stay |

|

Lyu et al., 2022 |

Cross‐sectional survey | 430 | ++/++ |

|

ITS Transformational leadership Work group cohesion Career growth Organizational commitment Job satisfaction |

Career growth, work group cohesion, job satisfaction, transformational leadership and organisational commitment were positively correlated with ITS at a moderate level. |

| Meng et al., 2015. China | Cross‐sectional survey | 219 | ++/++ |

|

Structural empowerment Psychological empowerment Burnout ITS |

High levels of structural empowerment and psychological empowerment have a significant positive effect on ITS. Psychological empowerment has a mediating role in burnout. Fostering meaningfulness, developing loyalty, and aligning with professional goals can reduce emotional exhaustion. |

| Nylén‐Eriksen et al., 2020. Norway | Descriptive comparative study | 297 | ++/++ |

|

Job involvement ITS |

Higher levels of job involvement linked with ITS. |

| Reinhardt et al., 2020. USA | Descriptive correlation study | 258 | ++/++ |

Work environment Belonging ITS |

Supportive workplace characteristics, affiliation and belonging are associated with increased ITS. Constructs of a healthy work environment, control of practice, autonomy, organizational support, moderate/manageable stress levels, collegial interaction, affiliation, conflict management and belonging increase employee engagement and ITS | |

| Robson & Robson, 2015. UK | Survey | 370 | ++/++ |

|

Leader‐ member exchange Work–family conflict Work attachment Importance of work to the individual Intention to stay |

Significant association with leader–member exchange, work–family conflict, attachment and importance of work and ITS. |

| Shacklock & Brunetto, 2011. Australia | Survey | 900 | ++/++ |

|

Meaning of work Attachment to work Generational preferences Work–family conflict Supervisor relationship ITS |

Intention to continue is significantly related to six independent variables; Work–family conflict, perception of autonomy at work, attachment to work, interpersonal relationships at work and the importance of work to the individual. |

| Wang et al., 2011. China | Descriptive correlation study | 560 | ++/++ |

Job satisfaction Organizational commitment ITS |

Significant significance between organizational commitment and ITS and a statistical significance between job satisfaction and ITS. Age and job position significantly related to organizational commitment and job satisfaction and ITS | |

| Wang et al., 2012. China | Cross‐sectional survey | 919 | ++/++ |

Organizational commitment Praise and recognition Professional advancement |

Normative commitment, economic costs commitment, age, limited alternatives for employment, praise and recognition, professional advancement opportunities and hospital classification were significantly significant to ITS. Demographically there were significant correlations between age, for each year of experience resulted in a 14% increase in nurse ITS. | |

| Wang et al., 2018. China | Cross‐sectional survey | 535 | ++/++ |

|

Transformational leadership Emotional intelligence |

Transformational leadership and emotional intelligence are significant predictors of ITS. Nurse emotional intelligence mediates the relationship between emotional intelligence and ITS. |

| Yarbrough et al., 2017. US | Descriptive correlation study | 67 | ++/++ |

Professional values Job satisfaction Career development Intention to stay |

Strong positive correlation between professional values, career development and job satisfaction; and a strong positive correlation between career development and ITS. Perceived value conflict negatively affects retention. Positive practice environments promote retention. There is a link between tenure and ITS |

The two authors independently screened titles and abstracts against the review eligibility criteria. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were retrieved and independently screened for their eligibility. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion, although these were minimal, and all decisions were recorded. The data extraction from full‐text articles of each study was carried out using a data extraction form which was piloted prior to use.

2.5. Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal was undertaken using the NICE quality appraisal checklist (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2012). This tool assesses the internal and external validity of research studies based on key features of their study design. The instrument contains five sections rated with five responses: ++, +, −, NR (not reported) and NA (not applicable). Section 1 assesses the external validity of a study, and Sections 2–5 confirm internal validity. To sum up, the overall quality of a study in respect of its internal and external validity is awarded three grades: ++ (high), + (medium) and − (low).

The results of the quality appraisal can be found in Table 2. Among the 34 studies assessed, the internal validity of all 34 studies was ranked with the highest grade (++). For that reason, the overall quality of the included studies with regard to internal and external validity is on a high level.

2.6. Data abstraction and synthesis

Due to the heterogeneity of the included study designs and the outcomes presented, a meta‐analysis could not be utilized. Therefore, a narrative synthesis of the data is applied guided by the Synthesis Without a Meta‐Analysis approach was applied (SWiM) (Campbell et al., 2019, 2020). This approach allowed an increased assurance of reliability, replicability, quality and rigour and afforded a trustworthiness and auditable decision trail (Lorelli, 2017). Table 2 provides evidence of the outcomes of abstraction and synthesis processes guided by Campbells nine key stages that include (1) grouping studies for synthesis according to the intervention model, (2) describing the standardized metric and transformation methods used, (3) highlighting the study synthesis methods, (4) highlighting the criteria used to prioritize results for summary and synthesis, (5) investigating heterogeneity in reported effects. Stages (6) and (7) detail the certainty of evidence and data presentation methods and with stage (8), the results are reported and finally, stage 9 concludes with limitations of the synthesis. The inferences and narrations structured in the results section were further synthesized and developed into the conceptual framework presented in Table 3 (Campbell et al., 2019, 2020).

TABLE 3.

Theoretical framework: protective factors informing nurses intention to stay

| Intention to stay | ||

|---|---|---|

| Job satisfaction | Organizational commitment | |

| i) Environmental factors: organizational culture | ii) Relational factors: professional dynamics | iii) Individual factors: psychosocial, emotional and professional cultures |

|

Conditions of work Work environment Safety climate Workplace culture Organizational support Pressure management Flexible working Perceived development |

Leadership Teamwork Trust Organizational conflict Job embeddedness Social support Belonging |

Stress Morale distress/emotional labour Emotional intelligence/personality Burnout Work–family conflict Resilience Autonomy Job control Empowerment Professional values |

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study characteristics

Thirty‐four studies from 13 different nations were included: Australia: n = 2, Canada: n = 2, UK: n = 1, USA: n = 4, China: n = 6, Iran: n = 2, Japan: n = 1, Israel: n = 1, Jordan: n = 7, Korea: n = 1, Norway: n = 1, Taiwan: n = 4 and Thailand n = 2. Sample sizes ranged from 67 to 3983. Intention to stay data was examined directly or indirectly in all studies.

All the papers included in the review applied the instrument Cronbach α as an internal coefficient measure of reliability. All reported findings within the included studies had a Cronbach α score >0.70 and, while acknowledging with caution the limitations of Cronbach Alpha, this tested instrument alongside commentary confirmed a construct validity, verified quality and assured consistency and replicability of research findings (Taber, 2017).

3.2. Intention to stay

Intention to stay was directly identified in 30 papers; 17 applied a theoretical intention to stay instrument. Seven different intentions to stay instruments were applied across the 17 papers namely Boyle et al. (1999), McCloskey and McCain (1987), Nedd (2006), Price and Muleller (1981), Tao and Wang (2010), Turnley and Feldman (1998) and Wang et al. (2012). Of the four studies that did not directly examine intention to stay, all identified a correlation through a direct relationship with either job satisfaction or organizational commitment.

There were two overarching outcomes namely (i) job satisfaction and (ii) organizational commitment that impacted ‘intention to stay’. Twenty‐six factors were identified that positively correlate to either job satisfaction or organizational commitment. These were developed into three groups: (i) environmental factors (including organizational culture) (ii) relational factors (including professional dynamics) and (iii) individual factors (including psychosocial, emotional and professional cultures) (Table 2).

3.2.1. Job satisfaction

Thirteen papers examined job satisfaction and its relationship with the intention to stay (AbuAlRub & Alghamdi, 2012; Al‐Hamdan et al., 2017; Brewer et al., 2016; Chen, Perng, et al., 2016; Chenoweth et al., 2014; Hewko et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2017; Larrabee et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; Lyu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012).

Job satisfaction occurs when employees feel that their needs are being met when they remain motivated and are able to overcome the challenges of employment. Job satisfaction is a principle protective factor of intention to stay (Jiang et al., 2017). Many factors influence job satisfaction, such as leadership (AbuAlRub & Alghamdi, 2012; Brewer et al., 2016), work environment (Al‐Hamdan et al., 2017; Hewko et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2012), organizational commitment (Brewer et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012), emotional intelligence (Chen, Perng, et al., 2016), career development (Brewer et al., 2016), social support (Chen, Perng, et al., 2016; Li et al., 2020), belonging (Jiang et al., 2017), group cohesion (Lyu et al., 2022), empowerment (Hewko et al., 2015), autonomy (Jiang et al., 2017), job control (Li et al., 2020), absence of burnout (Hewko et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2019) and stress management (Larrabee et al., 2010). These factors contribute to the feeling of fulfilment and/or enjoyment a nurse experiences when satisfied at work.

3.2.2. Organizational commitment

Six papers explored organizational commitment and its relationship with intention to stay (Brewer et al., 2016; Gellatly et al., 2014; Gholami et al., 2019; Lyu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012). Organizational commitment is linked to job satisfaction when nurses are satisfied and feel a sense of obligation to work, organizational commitment acts as a stabiliser which positively reinforces behavioural intent to stay (Wang et al., 2011).

Environmental factors: organizational culture

There are eight environmental factors within the group organizational culture: conditions of work, work environment, safety climate, workplace culture, organizational support, pressure management, flexible working and perceived development (AbuAlRub et al., 2012; AbuAlRub & Nasrallah, 2017; Al‐Hamdan et al., 2017; Eltaybani et al., 2018; Gholami et al., 2019; Hewko et al., 2015; Larrabee et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2019; Liang et al., 2016; Meng et al., 2015; Nylén‐Eriksen et al., 2020; Reinhardt et al., 2020; Robson & Robson, 2015; Shacklock & Brunetto, 2011, Wang et al., 2012; Yarbrough et al., 2017).

Work environment is a complex dynamic system that influences job satisfaction, organizational commitment and intention to stay. The eight environmental factors associate with the intention to stay are examined in 17 studies, thus illustrating the significant effect on organizational culture and its importance in influencing nurse retention.

Relational factors: professional dynamics

There are seven relational factors within the group of professional relationships and dynamics: leadership, teamwork, trust, organizational conflict, job embeddedness, social support and belonging. Almost half (15) of all studies reported findings on relational factors (AbuAlRub et al., 2012; AbuAlRub & Alghamdi, 2012; AbuAlRub & Nasrallah, 2017; Al‐Hamdan et al., 2016; Atiyeh & AbuAlRub, 2017; Chen, Ho, et al., 2016; Dechawatanapaisal, 2018; Hewko et al., 2015; Li et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2016; Lyu et al., 2022; Reinhardt et al., 2020; Robson & Robson, 2015; Shacklock & Brunetto, 2011; Yarbrough et al., 2017; Eltaybani et al., 2018).

Professional relationships are a significant contributing factor in a nurse's intention to stay and leadership and teamwork are highlighted in nine studies (AbuAlRub & Alghamdi, 2012; AbuAlRub & Nasrallah, 2017). Teamwork is positively linked with nurses feeling safer at work and with increased job satisfaction (AbuAlRub et al., 2012). Transformational and relational leadership is recognized to positively influence culture (AbuAlRub & Nasrallah, 2017; Lyu et al., 2022; Robson & Robson, 2015; Shacklock & Brunetto, 2011), promote job embeddedness (Dechawatanapaisal, 2018), positively impact on the work environment, burnout and empowerment (Eltaybani et al., 2018; Hewko et al., 2015), improve safety climate and emotional labour (Liang et al., 2016), promote autonomy and flexible working and support employees to balance work with home commitments (Robson & Robson, 2015; Shacklock & Brunetto, 2011).

Individual factors: psychosocial, emotional and professional culture

Sixteen studies examine individual factors of psychosocial, emotional and professional culture identifying 10 individual factors. These include stress (Borhani et al., 2014; Larrabee et al., 2010), moral distress/emotional labour (Borhani et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2017), emotional intelligence/personality (Al‐Hamdan et al., 2019; Chen, Perng, et al., 2016; Gholami et al., 2019), burnout (Hewko et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2017; Kerzman et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2019; Meng et al., 2015), work–family conflict (Robson & Robson, 2015; Shacklock & Brunetto, 2011), resilience (Larrabee et al., 2010), autonomy (Jiang et al., 2017; Kerzman et al., 2020; Robson & Robson, 2015; Shacklock & Brunetto, 2011), job control (Li et al., 2020), empowerment (Eltaybani et al., 2018; Hewko et al., 2015; Meng et al., 2015), career growth (Lyu et al., 2022) and professional values (Yarbrough et al., 2017). Nursing is not only physically demanding, the ethical nature and emotional labour of caring mean that nurses must be protected to manage stress and to feel empowered to feel in control of the situations they face.

These individual ‘protective factors’, when collated, inform the three‐overarching environmental, relational and individual constructs that group the protective factors into manageable areas to instruct understanding of why nurses stay. Nurses must be satisfied with the work environment, culture and conditions and be able to access constructive professional relationships while also having the personal ability to navigate the psychosocial and emotional dimensions of the job. These protective factors identify the nuance of what nurses need from organizations, leaders and themselves to influence them to want to stay.

Intergenerational principles

While the focus of the review was to understand why registered nurses stay working in the healthcare and social care sector, an incidental yet remarkable finding suggested factors varied noticeably between generations, age and career tenure. Fifteen studies present findings weighted by age or career tenure, relating to how ‘younger’ nurses (who have often worked fewer years in employment) have a lesser intention to stay working compared to their ‘older’ counterparts (AbuAlRub et al., 2012; Al‐Hamdan et al., 2016; Al‐Hamdan et al., 2019; Borhani et al., 2014; Chenoweth et al., 2014; Chen, Perng, et al., 2016; Dechawatanapaisal, 2018; Jiang et al., 2017; Larrabee et al., 2010; Liang et al., 2016; Robson & Robson, 2015; Shacklock & Brunetto, 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012; Yarbrough et al., 2017). This is an important sycophantic finding when considered in the round of targeting retention interventions to support nurses to stay.

4. DISCUSSION

This review explores and lists the fundamental and complex reasons why nurses stay working in health and care roles. The key findings suggest that nurses will stay when the workplace culture and conditions meet their personal and professional needs. Nurses stay when professional relationships are supportive, trusting and enable them to feel safe and belong (Lyu et al., 2022; Reinhardt et al., 2020). Alongside this, nurses are more likely to stay if they are motivated to remain engaged and connected and when they can master the challenges of working environment (AbuAlRub & Nasrallah, 2017; Larrabee et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012). Intrinsically, nurses stay when they perceive they can manage their personal stress and the emotional burdens contingent on caring for others, and when they are able to work autonomously and feel empowered (Jiang et al., 2017; Kerzman et al., 2020). It is also imperative that nurses can provide care corresponding to their professional values and that they have opportunities to professionally grow (Lyu et al., 2022; Yarbrough et al., 2017). These are the factors that meet the requirements for job satisfaction and organizational commitment and this review evidences that nurses stay when these conditions are obtainable at work. These factors can be described as ‘protective factors’ and are salient antecedent pull factors that protect and safeguard the intention to stay (Table 3).

Expectancy theory suggests that employees have expectations and values, which if aligned, increase the likelihood of remaining a member of the organization (Vroom, 1964; Weninger, 2020). This principle underpins the ‘Effort–Reward Imbalance’ theory which establishes that the amount of effort an employee puts into employment must be equally rewarded through their needs and expectations being met to avoid them feeling an imbalance. A perceived effort–reward imbalance, such as a nurse feeling that they are giving more than they are getting can be demotivating and linked directly to the intention to leave (Eltaybani et al., 2018; Lyu et al., 2022; Weninger, 2020; Wieck et al., 2009). In the case of the study findings, it is clearly visible what nurses need from employment in order to be rewarded with job satisfaction and in turn stay committed to an organization. What perhaps requires complementary reflection is the relationship of the power correlation with the factors that support nurses to sit and their nuance with age and career tenure. Knowing what matters most to nurses and at what age and career stage is preponderant contemporary information for nurse leaders, hiring and other support or retention initiatives when looking to improve nurse retention.

Protective factors represent the generic factors of all age and career tenure nurses require to stay working for longer. Appreciating that in a wider professional sense nurses share more than divides them, all things being equal, protective factors would have the same weighting for all nurses (Robson & Robson, 2015; Yarbrough et al., 2017). It is, however, clear from the research findings of many studies that this is not the case, and that nurses across different ages and tenures of career have unique priorities of employment needs, meaning the innate environmental, relational and individual priorities are weighted, offering the suggestion of the opportunity to not only understand how to protect nurses to stay but the added benefit of knowing that targeting cohorts of the nursing workforce that are vulnerable to leaving will realise amplifying retention outcomes (AbuAlRub et al., 2012; Al‐Hamdan et al., 2016; Al‐Hamdan et al., 2019; Borhani et al., 2014; Chen, Perng, et al., 2016; Chenoweth et al., 2014; Dechawatanapaisal, 2018; Jiang et al., 2017; Larrabee et al., 2010; Liang et al., 2016; Shacklock & Brunetto, 2011).

As identified, nurse behaviours differ by a generation with needs and motivations diverging considerably across the nursing workforce (Cahill, 2012; Shacklock & Brunetto, 2011). While acknowledged to not be a universal remedy, generational theories highlight how each person evolves within a cohort of peers that encounter similar life experiences, which subsequently shape distinct generational characteristics, attitudes, beliefs, work habits, expectations and behaviours (Piper, 2012; Sherman, 2014). For example, millennials and generation Z workers (Table 4) are said to have the same workplace values as their nursing predecessors, such as altruism and the desire to provide excellent patient care. Yet, there is a stark difference across age groups so far as workplace needs, motivations and challenges are concerned. ‘Younger’ or early career nurses (ECN) are more transient and have a lesser attachment to organizations and to work than ‘older’ nurses, all having a critical effect on the intention to stay (Shacklock & Brunetto, 2011; Wieck et al., 2009). It should be acknowledged that the amount of ‘effort’ required to learn new skills is greater for our ECNs when starting out in a profession, contrasting with mid and late‐career nurses. This reflects the thinking of Alderfer's (1972) Existence, Relatedness and Growth (ERG) theory which suggests that to stay motivated and progress towards an understanding of how to satisfactorily work in the nursing profession, ECNs must be supported and empowered to not feel frustrated and overburdened leading to them feeling too challenged, we see this narrative come through in the research findings. When this vulnerable cohort of nurses is not given this support can lead to regression and slow growth in practice development, therefore increasing the threat of leaving (Lyu et al., 2022).

TABLE 4.

Generational age profiles

| Generation | Years born | Ages |

|---|---|---|

| Baby Boomers | 1946–1964 | 57–75 |

| Generation X | 1965–1980 | 41–56 |

| Millennials | 1981–1999 | 27–41 |

| Generation Z | Mid 1990s to late 2000s | <27 years |

Behavioural theory explains how individuals make decisions based on the parameters of the personal and situational requirements needed to reach a solution. ‘Maximizing’ is a form of decision‐making where every attempt to select the very best decision for the outcome is made (Richie & Martin, 1999). Either consciously or subconsciously, ECNs ‘maximize’ in their decision on where they choose to work and with whom to try their best to maintain an ‘effort–reward’ equilibrium and survive the widely evidenced hazard of leaving nursing in the early years of the profession. ECNs are more willing, and likely more able, to leave employment for better leadership and social support (Liang et al., 2016) or a working environment that affords them to manage the pressure or to avoid feeling overwhelmed and burnout (Jiang et al., 2017) that will in the purest sense manage the effort they see as their contribution to the profession, by keeping them satisfied at work.

In turn, ‘older’ nurses have a higher propensity to continue in their role than ‘younger’ nurses; mid‐career nurses, namely, those older than 30 years of age are significantly more likely to stay than nurses younger than 30 (Larrabee et al., 2010; Lyu et al., 2022; Robson & Robson, 2015). While mid and later‐career nurses do not appear to demonstrate the same seeking behaviour and exhibit a comparatively lower threat to exit, they still have their own unique and multifaceted employment needs and challenges which must not be overlooked. Nurses do not leave employment suddenly; a nurse's decision to leave is the result of an intricate multi‐step process that happens over a period of time as they become disenchanted and then subsequently disconnect, corroding job satisfaction and as such intention to stay (Cowden & Cummings, 2012; Lin et al., 2011).

Of the two key elements, job satisfaction was identified as the principal positive factor that ultimately influences retention. Organizational commitment, on the other hand, can be both a positive and a negative reason for why nurses stay working (Gellatly et al., 2014; Lyu et al., 2022). Organizational commitment was recognized to be greater in later‐career nurses, however, this was not always positively related directly to job satisfaction, older nurses sometimes had a forced commitment to staying if they did not have the opportunity to find a similar grade position elsewhere or lacked the motivation to leave (Brewer et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012). Organizational commitment, irrespective of age and career stage, was greatest overall when nurses enjoyed work and felt a sense of duty to their job (Gellatly et al., 2014; Gholami et al., 2019). Younger nurses however are peripatetic, readily job hopping to find greater meaning from work and/or to achieve job empowerment and/or in order to provide better patient care; subsequently, fulfilling their individual expectations and job satisfaction needs over loyalty and job security (Yarbrough et al., 2017).

The environmental construct and perceptions of work environment, work conditions and organizational culture are important protective factors in nurse retention. Work environment, work conditions and organizational culture have an associated interdependence with job control, emotional intelligence, empowerment and autonomy (Hewko et al., 2015; Li et al., 2020; Meng et al., 2015). Years of nursing experience are directly associated with increased satisfaction, with nurses who have more than 10 years of experience reporting higher perceptions of safety and trust than nurses who have 1–2 years of experience (Atiyeh & AbuAlRub, 2017; Shacklock & Brunetto, 2011; Yarbrough et al., 2017). It is argued that this is because older nurses or nurses who have worked longer in the role have higher levels of intrinsic or learned ability to manage the pressure that enables them to better navigate the conditions of work (Gholami et al., 2019).

Remarkably, the work–life balance environmental factor weighed equal priority across all ages and career stages (Robson & Robson, 2015; Shacklock & Brunetto, 2011). All nurses want organizations to provide flexibility and family/life friendly workplace policies, equitable remuneration and ongoing education and skills development irrespective of their age and career stage (Chenoweth et al., 2014). Intriguingly, debate suggests that the most satisfied nurses are those who have several years of experience that have recently moved into a new job; this opens the door to the suggestion that while nurses staying in the profession is needed, nurses staying working in the same area when dissatisfied may be intrinsically and extrinsically counterintuitive if they feel demotivated or disengaged (Eltaybani et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2012).

The relational construct, particularly referring to leadership, is identified to show association with the work environment, work conditions and organizational culture; leaders were often recognized as the conduit for setting the precedent for safety climate (Hewko et al., 2015; Liang et al., 2016; Shacklock & Brunetto, 2011). Positive working relationships protect nurses from leaving (AbuAlRub & Alghamdi, 2012; Brewer et al., 2016; Dechawatanapaisal, 2018). Many of the factors within the relational category are interconnected. Atiyeh and AbuAlRub (2017) describe how trust in managers protects and empowers staff and that when the level of trust increases, the level of work stability and intent to stay at work also increases. Teamworking improves job involvement and autonomy and increases job satisfaction (AbuAlRub et al., 2012; Lyu et al., 2022; Nylén‐Eriksen et al., 2020). Leaders who foster trusting, caring, psychologically safe work environments and respect‐based relationships, boost team morale and develop feelings of embeddedness, all of which directly link to job satisfaction and indirectly link to nurses intention to stay (Chen, Perng, et al., 2016; Li et al., 2020; Reinhardt et al., 2020).

While all nurses mandate the same need for supportive working relationships, there are variations in what nurses at different ages and career stages need from leadership and teams. Older/later‐career nurses value leaders who positively impact their work environment and recognize and respect them for their experience (Brewer et al., 2016). Older employees and mid‐career nurses have high levels of attachment to work, greater organizational involvement and job embeddedness (Dechawatanapaisal, 2018; Robson & Robson, 2015). ECNs on the less experienced end of the career spectrum, however, require supportive relationships to help them safely develop their professional identity to transition into working in the role of a nurse as they navigate to find their professional self (Douglas et al., 2020). These differences manifest themselves in retention behaviours, with older nurses staying longer for leaders they enjoy working with, whereas younger nurses will actively leave jobs in search of better leadership (Eltaybani et al., 2018; Liang et al., 2016).

And finally, nurses must have the capability to manage stress, emotional distress and cope with the poignant burden of caring. Nurses want to feel empowered, have autonomy and job control and feel they are working in ways that are in harmony with their personal and professional values (Eltaybani et al., 2018; Yarbrough et al., 2017). Levels of personal stress vary by age, gender, years since completing pre‐registration education and the number of years in current job (Larrabee et al., 2010). Younger and inexperienced nurses were recognized as having limited personal resilience to cope with complex and stressful working conditions (Kerzman et al., 2020), which consequently negatively affects job satisfaction and increases intentions to leave. Moral and professional distress decrease with age and service years, suggesting that as nurses gain more experience, and in facing more moral challenges and stressors, they build more effective defensive mechanisms and thus are less affected (Borhani et al., 2014; Chen, Ho, et al., 2016). ECN often feel disoriented when they first qualify as nurses and are at greater risk of feeling overwhelmed with their workload and least happy with job control (Douglas et al., 2020). In contrast, mid and late‐career nurses describe wanting more autonomy and control (Yarbrough et al., 2017).

4.1. Limitations

Although this systematic review attempts to reduce bias through transparency, rigour and replicability, there were several limitations at study and outcome levels. Firstly, only English language studies were included. Furthermore, wide variations in the context and programme designs and differences in how the data outcomes were measured meant that we were unable to undertake a meta‐analysis, pool results and arrive at an overall conclusion. Consequently, the majority of the results were interpreted narratively. And lastly, the summary of this review is only as reliable as the methods used to test for effectiveness. Thus, where the quality of the research is possibly contaminated with the risk of bias due to inherent problems in the design and its methodology, this sought to be mitigated by the selection studies with a Cronbach α >0.70.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, workforce deficits pose an enormous challenge for healthcare systems, leaders and individuals. Nursing shortages cause the demand for nurses to rise, which in turn triggers more nurses to leave the profession and without a solution, the challenge is only set to grow. This research is a systematic review and narrative synthesis of the determinants of a nurse's decision to stay. The study identifies organizational, relational or individual factors of a nurse's decision to stay and isolate factors that are weighted by age and career stage. This new knowledge is collated and presented as a Nurse Intention to Stay: Theoretical framework of protective factors (Table 3). The framework has been designed to guide retention strategies and provides a forward‐looking, solutions‐focused knowledge base on which further research can build.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Both authors contributed to the study conception of the review question, searching the literature and conducting all steps of the study. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The research was not supported by funding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There is no conflict of interest to declare for either author.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

As a systematic review, no ethical approvals were required.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

No participants were involved in the study.

Pressley, C. , & Garside, J. (2023). Safeguarding the retention of nurses: A systematic review on determinants of nurse's intentions to stay. Nursing Open, 10, 2842–2858. 10.1002/nop2.1588

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data generated and analyzed is included in the article.

REFERENCES

- AbuAlRub, R. F. , & Alghamdi, M. (2012). The impact of leadership styles on nurse' satisfaction and intention to stay among Saudi nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 20, 668–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AbuAlRub, R. F. , Gharaibeh, H. F. , & Bashayreh, A. E. (2012). The relationships between safety climate, teamwork, and intent to stay at work among Jordanian hospital nurses. Nursing Forum, 47(1), 65–75. 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2011.00253.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AbuAlRub, R. F. , & Nasrallah, M. A. (2017). Leadership behaviours, organizational culture and intention to stay amongst Jordanian nurses. International Nursing Review, 64(4), 520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L. , & Fagin, C. (2018). Evidence‐based nurse staffing: ICN's new position statement. International Nursing Review, 65(4), 469–471. 10.1111/inr.12499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Hamdan, Z. , Manojlovich, M. , & Tanima, B. (2017). Jordanian nursing work environments, intent to stay, and job satisfaction. Journal of Nursing Scholarship: An official publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing, 49(1), 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Hamdan, Z. , Nussera, H. , & Masa'deh, R. (2016). Conflict management style of Jordanian nurse managers and its relationship to staff nurses' intent to stay. Journal of Nursing Management, 24(2), 137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al‐Hamdan, Z. M. , Muhsen, A. , Alhamdan, M. , Rayan, A. , Banyhamdan, K. , & Bawadi, H. (2019). Emotional intelligence and intent to stay among nurses employed in Jordanian hospitals. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(2), 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderfer, C. P. (1972). Existence, relatedness, and growth: Human needs in organizational settings. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, N. J. , & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurements and antecedents of effective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organisation. Journal of Organisational Psychology, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum, D. , Fowler, S. , Fiedler, N. , Osinubi, O. , & Robson, M. (2010). The impact impact of environmental factors on nursing stress, job satisfaction, and turnover intention. Journal of Nursing Administration, 2010, 323–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atiyeh, H. M. , & AbuAlRub, R. F. (2017). The relationship of trust and intent to stay among registered nurses at Jordanian hospitals. Nursing Forum, 52(4), 266–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. , & Avolio, B. (1997). Full range leadership development: Manual for the multifactorial leadership questionnaire. Mindgarden. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. , & Avolio, B. (2004). Manual for multifactorial leadership questionnaire: Sampler set (3rd ed.). Mind Garden Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Borhani, F. , Abbaszadeh, A. , Nakhaee, N. , & Roshanzadeh, M. (2014). The relationship between moral distress, professional stress, and intent to stay in the nursing profession. Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine, 7, 3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, D. , Bott, M. , Hansen, H. , Woods, C. , & Taunton, R. (1999). Managers’ leadership and critical care nurses’ intent to stay. American Journal of Critical Care, 8, 361–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breaugh, J. A. (1999). Further investigations of the work autonomy scales: Two studies. Journal of Business and Psychology, 13, 357–373. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, C. S. , Kovner, C. T. , Djukic, M. , Fatehi, F. , Greene, W. , Chacko, T. P. , & Yang, Y. (2016). Impact of transformational leadership on nurse work outcomes. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(11), 2879–2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan, J. , Catton, H. , & Shaffer, F. (2022). Sustain and retain in 2022 and beyond. International Centre on Nurse Migration. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, T. (2012). Leading a multigenerational workforce: Strategies for attracting and retaining millennials. Frontiers of Health Service Management, 29(1), 3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M. , Katikireddi, S. , Sowden, A. , & Thompson, H. (2019). Lack of transparency in reporting narrative synthesis of quantitative data: A methodological assessment of systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 105, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M. , McKenzie, J. , Sowden, A. , Katikireddi, S. , Brennan, S. , Ellis, S. , Hartmann‐Boyce, J. , Ryan, R. , Shepperd, S. , Thomas, J. , Welch, V. , & Thomson, H. (2020). Synthesis without meta‐analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. British Medical Journal, 368, 16890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. C. , Perng, S. J. , Chang, F. M. , & Lai, H. L. (2016). Influence of work values and personality traits on intent to stay among nurses at various types of hospital in Taiwan. Journal of Nursing Management, 24(1), 30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M. F. , Ho, C. H. , Lin, C. F. , Chung, M. H. , Chao, W. C. , Chou, H. L. , & Li, C. K. (2016). Organisation‐based self‐esteem mediates the effects of social support and job satisfaction on intention to stay in nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 24(1), 88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenoweth, L. , Merlyn, T. , Jeon, Y. , Tait, F. , & Duffield, C. (2014). Attracting and retaining qualified nurses in aged and dementia care: Outcomes from an Australian study. Journal of Nursing Management, 22(2), 234–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corley, M. C. , Elswick, R. K. , Gorman, M. , & Clor, T. (2001). Development and evaluation of a moral distress scale. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33(4), 250–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowden, T. , & Cummings, G. (2012). Nursing theory and concept development: A theoretical model of clinical nurses' intentions to stay in their current positions. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(7), 1646–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, C. D. , Bennett, R. J. , Jex, S. M. , & Burnfield, J. L. (2007). Development of a global measurement of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1031–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechawatanapaisal, D. (2018). Nurses' turnover intention: The impact of leader‐member exchange, organizational identification and job embeddedness. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(6), 1380–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue, M. O. , Piazza, I. M. , Griffin, M. Q. , Dykes, P. C. , & Fitzpatrick, J. J. (2008). The relationship between nurse perceptions of empowerment and patient satisfaction. Applied Nursing Research, 21, 2–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, J. , Bourgeois, S. , & Moxham, L. (2020). Early career nurses: Hoe they stay. Royal College of Nursing, Australia, 27(4), 437–442. [Google Scholar]

- Duddle, M. , & Boughton, M. (2009). Development and psychometric testing of the nursing workplace relational environment scale (NWRES). Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(6), 902–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, D. J. , & Ganster, D. C. (1991). The effects of job demand and control on employee attendance and satisfaction. Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 12, 595–608. [Google Scholar]

- Ellett, A. , Ellett, C. , & Ruggutt, J. (2003). A study of personal and organisational factors contributing to employee retention and turnover in child welfare in Georgia. University of Georgia. [Google Scholar]

- Eltaybani, S. , Noguchi‐Watanabe, M. , Igarashi, A. , Saito, Y. , & Yamamoto‐Mitani, N. (2018). Factors related to intention to stay in the current workplace among long‐term care nurses: A nationwide survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 80, 118–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks, C. A. , Squires, J. E. , Cummings, G. G. , Birdsell, J. , & Norton, P. G. (2009). Development and assessment of the Alberta context tool. BMC Health Services Research, 9, 234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks, C. A. , Tourangeau, A. E. , & Humphrey, C. K. (2002). Measuring the hospital practice environment: A Canadian context. Revised Nursing Work Index (NWI‐R). Research in Nursing & Health, 25(5), 256–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flinkman, M. , Laine, M. , Leino‐Kilpi, H. , Hasselhorn, H. M. , & Salanterä, S. (2008). Explaining young registered Finnish nurses' intention to leave the profession: A questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45, 727–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellatly, I. R. , Cowden, T. L. , & Cummings, G. G. (2014). Staff nurse commitment, work relationships, and turnover intentions: A latent profile analysis. Nursing Research, 63(3), 170–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gholami, M. , Saki, M. , Hossein, P. , & Amir, H. (2019). Nurses' perception of empowerment and its relationship with organizational commitment and trust in teaching hospitals in Iran. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(5), 1020–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierk, B. , Kohlmann, S. , Kroenke, K. , Spangenberg, L. , Zenger, M. , Brahler, E. , & Lowe, B. (2014). The Somatic Symptom Scale‐8 (SSS‐8): A brief measure of somatic symptom burden. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graen, G. B. , & Uhi‐Bien, M. (1995). Relationship‐based approach to leadership: Development of leader‐member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi‐level multi‐domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247. [Google Scholar]

- Hewko, S. J. , Brown, P. , Fraser, K. D. , Wong, C. A. , & Cummings, G. G. (2015). Factors influencing nurse managers' intent to stay or leave: A quantitative analysis. Journal of Nursing Management, 23(8), 1058–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, K. S. (2011). Work satisfaction, intention to stay, desires among bedside and advanced practice nurses. Journal of Nursing Administration, 41, 211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw, A. S. , & Atwood, J. R. (1985). Anticipated turnover amongst nursing staff study: Final report (No. R01NU00908). National Institute of Health, National Centre for Nursing Research. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw, A. S. , & Atwood, J. R. (1983). Nursing staff turnover, stress, and satisfaction: Models, measures, and management. Annual Review of Nursing Research, 1(1), 133–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H. , Ma, L. , Gao, C. , Li, T. , Huang, L. , & Huang, W. (2017). Satisfaction, burnout and intention to stay of emergency nurses in Shanghai. Emergency Medicine Journal, 34(7), 448–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagwe, J. , Jones, S. , & Johnson, S. L. (2019). Factors related to intention to leave and job satisfaction amongst registered nurses at a large psychiatric hospital. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 2019, 754–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanungo, R. N. (1982). Measurement of job and work involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67(3), 341–349. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, E. , Stoye, G. , & Warner, M. (2022). Factors associated with staff retention in the NHS acute sector. Institute for Fiscal Studies. IFS‐R216‐Factors‐associated‐with‐staff‐retention‐in‐the‐NHS‐acute‐sector_2.pdf. ims.gov.uk [Google Scholar]

- Kerzman, H. , Van Dijk, D. , Siman‐Tov, M. , Friedman, S. , & Goldberg, S. (2020). Professional characteristics and work attitudes of hospital nurses who leave compared with those who stay. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(6), 1364–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. W. , Price, J. L. , Mueller, C. W. , & Watson, T. W. (1996). The determinants of career intent amongst physicians at a U.S. air force hospital. Human Relations, 49(7), 947–976. [Google Scholar]

- Kouzes, J. , & Posner, B. (2001). LPI participants workbook (2nd Edi. ed.). Joshey‐Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Lake, E. T. (2002). Development of the practice environment scale of the nursing work index. Research in Nursing & Health, 25, 176–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrabee, J. H. , Wu, Y. , Persily, C. A. , Simoni, P. S. , Johnston, P. A. , Marcischak, T. L. , Mott, C. L. , & Gladden, S. D. (2010). Influence of stress resiliency on RN job satisfaction and intent to stay. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 32(1), 81–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger, H. K. , Almost, J. , & Tuer‐Hodes, D. (2003). Work‐place empowerment and magnet hospital characteristics: Making the link. Journal of Nursing Administration, 33, 410–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law, K. , Wong, C. , & Song, L. (2004). The construct and criterion validity of emotional intelligence and its potential utility for management studies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(3), 483–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. A. , Ju, Y. H. , & Lim, S. H. (2019). A study on the intent to leave and stay among hospital nurses in Korea: A cross‐sectional survey. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(2), 332–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y. O. , & Kang, J. (2018). Related factors of turnover intention among Korean hospital nurses: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Korean Journal of Adult Nursing, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter, M. P. , Day, A. , Harvie, P. , & Shaughnessy, K. (2007). Personal and organisational knowledge transfer: Implications for work‐life engagement. Human Relations, 60, 259–283. [Google Scholar]

- Levett‐Jones, T. , & Lathlean, J. (2009). The ascent to competence conceptual framework: An outcome of a study of belongingness. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(200), 2870–2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. , Zhang, Y. , Yan, D. , Wen, F. , & Zhang, Y. (2020). Nurses' intention to stay: The impact of perceived organizational support, job control and job satisfaction. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(5), 1141–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H. Y. , Tang, F. I. , Wang, T. F. , Lin, K. C. , & Yu, S. (2016). Nurse characteristics, leadership, safety climate, emotional labour and intention to stay for nurses: A structural equation modelling approach. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(12), 3068–3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S. Y. , Chiang, H. Y. , & Chen, L. (2011). Comparing nurses' intent to leave or stay: Differences of practice environment perceptions. Nursing & Health Sciences, 13(4), 463–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C. C. , & Shiao, S. Y. (2005). Relationship among social support, trust, organisational relationship and knowledge sharing behaviours based on the perspective of social exchangetheory. Commerce & Management Quarterly, 6, 373–400. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. , Yang, J. , Liu, Y. , Yang, Y. , & Zhang, H. (2015). The use of career growth scale in Chinese nurses: Validity and reliability. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 2(1), 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K. , You, L. , Chen, S. , Hao, Y. , Zhu, X. , Zhang, L. , & Aiken, L. (2012). The relationship between hospital work environment and nurse outcomes in Guangdong, China: A nurse questionnaire survey. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(9‐10), 1476–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorelli, S. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Sage Journals, 16, 160940691773384. 10.1177/1609406917733847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, X. , Siovong, P. , Akkadechanunt, T. , & Juntasopeepun, P. (2022). Factors influencing intention to stay of male nurses: A descriptive predictive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 24, 322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C. , & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey, J. , & McCain, B. (1987). Satisfaction, commitment, and professionalism of newly employed nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 22, 140–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey, J. C. (1990). Two requirements for job contentment: Autonomy and social integration. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 22(3), 140–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, R. R. , & Costa, P. T. (1997). Personality trait structure as a human universal. American Psychologist, 52, 509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaning of Work International Research Team (MOWIRT) . (1987). The meaning of work. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L. , Liu, Y. , Liu, H. , Hu, Y. , Yang, J. , & Liu, J. (2015). Relationships among structural empowerment, psychological empowerment, intent to stay and burnout in nursing field in mainland China‐based on a cross‐sectional questionnaire research. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 21(3), 303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. P. , Stanley, D. J. , Herscovitch, L. , & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta‐analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 61(1), 20–52. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , & Altman, D. (2008). The PRISMA Group: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(2008), e100009. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Shamseer, L. , Clarke, M. , Ghersi, D. , Liberati, A. , Petticrew, M. , Shelkelle, P. , & Stewart, L. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta‐analysis protocols (PRISMA‐P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1. 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscelli, G. M. , Sayli, M. , & Mello, M. (2022). Staff engagement, job Complimentarity and labour supply: Evidence form the English NHS hospital workforce. Discussion paper series. IZA Institute of Labour Economics. https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/15126/staff‐engagement‐job‐complementarity‐and‐labour‐supply‐evidence‐from‐the‐english‐nhs‐hospital‐workforce [Google Scholar]

- Mowday, R. T. , Steers, R. M. , & Porter, L. W. (1979). The measurement of organisational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 14(2), 224–247. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, C. , & McCloskey, J. (1990). Nurses’ job satisfaction. Nursing Research, 39(2), 113–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, M. S. (2002). Using a single item approach to measure facet job satisfaction. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 75, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . (2012). NICE Quality appraisal checklist. Retrieved from. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/appendix‐g‐quality‐appraisal‐checklist‐quantitative‐studies‐reporting‐correlations‐and#checklist

- Nedd, N. (2006). Perceptions of empowerment and intention to stay. Journal of Nursing Economics, 24, 13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer, R. G. , Boles, J. S. , & McMurrian, R. (1996). Development and validation of work‐family conflict and family‐work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 400–410. [Google Scholar]

- Nylén‐Eriksen, M. , Grov, E. K. , & Bjørnnes, A. K. (2020). Nurses' job involvement and association with continuing current position‐A descriptive comparative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(13–14), 2699–2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Economics . (2014). The cost of brain drain: Understanding the financial impact of staff turnover. Retrieved from. https://www.oxfordeconomics.com/resource/the‐cost‐of‐brain‐drain/

- Pei, Y. (2007). Research on the structure of occupational commitment of nurses. Psychological Science, 30(6), 1484–1485. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, S. J. , Richter, J. P. , & Beauvais, B. (2018). The effects of nursing satisfaction and turnover cognitions on patient attitudes and outcomes: A three‐level multisource study. Health Services Research, 53, 4943–4969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper, L. (2012). Generation Y in healthcare: Leading millennials in an era of reform. Frontiers of Health Services Management, 29(1), 16–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price, J. L. (2001). Reflections of the determinants of voluntary turnover. International Journal of Manpower, 22(7), 600–624. [Google Scholar]

- Price, L. , & Muleller, C. (1981). A causal model of turnover for nurses. Academy of Management Journal, 3, 543–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, R. P. , & Shepard, L. J. (1974). The 1972–73 quality of employment survey. Institute of Social Research. University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Rahim, M. (1983). A measure of styles of handling interpersonal conflict. Academy of Management Journal, 26, 368–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt, A. , León, T. , & Amatya, A. (2020). Why nurses stay: Analysis of the registered nurse workforce and the relationship to work environments. Applied Nursing Research, 55, 151316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie, S. , & Martin, P. (1999). Motivation management. Gower. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, A. , & Robson, F. (2015). Do nurses wish to continue working for the UK National Health Service? A comparative study of three generations of nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(1), 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, R. , Palmgreen, P. , & Sypher, H. (1994). Communication research measures: A sourcebook. Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C. , Bergin, M. , White, M. , & Wells, J. (2019). Ageing in the nursing workforce – A global challenge in an Irish context. International Nursing Review, 66, 157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. , Bakker, A. , & Salanova, M. (2016). The Measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross‐national study. Educational and Psychological Management, 66(4), 701–716. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton, J. , Helmreich, R. , Neilands, T. , Rowan, K. , Viella, K. , Boyben, J. , Roberts, P. , & Thomas, E. (2006). The safety attitudes questionnaire: Psychometric properties, benchmarking data and emerging research. BMC Health Services Research, 6, 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexton, J. , Holmueller, R. , Pronovost, V. , Thomas, E. , McFerran, S. , & Nunes, J. (2006). Variation in care giver perceptions of teamwork climate in labour and delivery units. Journal of Perinatology, 26, 463–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shacklock, K. , & Brunetto, Y. (2011). The intention to continue nursing: Work variables affecting three nurse generations in Australia. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(1), 36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shembavnekar, N. , Buchan, J. , Bazeer, N. , Kelly, E. , Beech, J. , Charlesworth, A. , McConkey, R. , & Fisher, R. (2022). NHS workforce projections 2022. The Health Foundation. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/nhs‐workforce‐projections‐2022 [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, R. (2014). Leading generation YNurses. Nurse Leader, 12(3), 28–50. [Google Scholar]

- Shirom, A. , & Melamed, S. (2006). A comparison of the construct validity of two burnout measures in two groups of professionals. International Journal of Stress Management, 13, 176–200. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, P. (1985). Measurements of human service staff satisfaction: Development of the job satisfaction survey. American Journal of Community Psychology, 13, 693–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995a). An empirical test of a comprehensive model of interpersonal empowerment in the workplace. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 601–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995b). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurements, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Staines, G. , & Quinn, R. (1979). American workers evaluate the quality of their jobs. Monthly Labour Review, 102(1), 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- State of the World's Nursing, (SOWN) . (2020). Investing in education, jobs and leadership. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Taber, K. (2017). The use of Cronbach's alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, H. , Hu, J. , Wang, L. , & Lui, X. (2009). Development of a scale for job satisfaction assessment in nurses. Academic Journal of Second Military Medical University, 31(11), 1292–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, H. , & Wang, L. (2010). Establishment of questionnaire for nurse intention to remain employed: The Chinese version. Academic Journal of Second Military Medical University, 31(8), 925–927. [Google Scholar]