Abstract

Background:

Research on intimate partner violence (IPV) faces unique challenges to recruitment and retention. Little is known about successful strategies for recruiting and retaining in research women who have experienced IPV, and their experiences of research participation.

Purpose:

This article presents findings on recruitment, retention, and research participation experiences from a longitudinal observational study of IPV among women receiving care through the Veterans Health Administration.

Methods:

Administrative tracking data were analyzed to identify strengths, challenges, and outcomes of multiple recruitment strategies for an observational study of women patients who had experienced past-year IPV. Qualitative interviews with a purposively selected subset of the larger sample were used to identify motivations for and experiences of study participation.

Results:

Of the total sample (N = 169), 92.3% were recruited via direct outreach by the research team (63.3% via letter, 29.0% in person), compared with provider or patient self-referral (3.6% and 4.1%, respectively); 88% returned for a follow-up assessment. In qualitative interviews (n = 50), participants expressed a desire to help others as a primary motivation for study participation. Although some participants experienced emotional strain during or after study visits, they also expressed perceiving value in sharing their experiences, and several participants found the experience personally beneficial. Participants expressed that disclosure was facilitated by interviewers’ empathic and neutral stance, as well as the relative anonymity and time-limited nature of the research relationship.

Conclusions:

Direct outreach to women Veterans Health Administration patients to participate in research interviews about IPV experience was feasible and effective, and proved more fruitful for recruitment than reliance on provider or patient self-referral. Women who have experienced IPV may welcome opportunities to contribute to improvements in care through participation in interviews.

Research with human participants often presents both recruitment and retention challenges, with many studies failing to meet recruitment targets within initial timelines (Treweek et al., 2013). Studies focused on sensitive topics and/or small or minority populations can face particular challenges. Intimate partner violence (IPV), including psychological, physical, and/or sexual violence and abuse by a current or former intimate partner, is a sensitive topic, associated with wide-ranging adverse impacts on health and well-being, particularly among women (Black et al., 2011; Dichter, Cerulli, & Bossarte, 2011; Dichter et al., 2017a,b). Owing to concerns regarding stigma, emotional distress, and potential for increased violence (i.e., perpetrator retaliation) resulting from the disclosure of IPV experience, research with women who have experienced IPV requires safety and confidentiality measures that may pose challenges to common recruitment and data collection strategies (Logan, Walker, Shannon, & Cole, 2008; McFarlane, 2007). For example, recruitment materials may need to omit specific reference to violence or abuse to protect participant safety and privacy while still ensuring that potential participants understand the study focus (Logan et al., 2008).

Women military veterans face disproportionately high rates of lifetime IPV, making this an important population to include in IPV research (Dichter et al., 2011). Women comprise the fastest-growing segment of the veteran population yet remain a numerical minority among both the larger veteran population and those receiving care in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), posing additional challenges to inclusion in clinical research (Frayne et al., 2013). We know little about successful strategies for recruiting and retaining women veterans in VHA-based research and about their research participation experiences, and still less about engaging women veterans who have experienced IPV.

Responding to calls for improved reporting of recruitment and retention in IPV research (Dutton, Holtzworth-Munroe, Jouriles, McDonald, & McFarlane, 2003), we seek to add to the growing knowledge base by presenting findings and lessons learned from a study of IPV among women patients of two VHA medical centers. These findings may help to inform other research on IPV and/or with women veterans. We discuss recruitment strategies—including challenges and successes-—and outcomes, based on an analysis of study tracking data, and present findings on participants’ motivations for and experiences with study participation from qualitative interviews.

Current Study

Data were collected as part of a longitudinal nonintervention study on health, safety, empowerment, and engagement with IPV-related services among women VHA patients with self-reported IPV in the 12 months before enrollment. We sought to enroll a convenience sample of 80 participants at each of two VHA sites (160 total) to complete structured interviews at baseline and 6- to 9-month follow-up, and, for a subset of participants (25 per site; 50 total), an in-depth qualitative interview at follow-up. Participants in qualitative interviews were selected based on interest, availability, and willingness to participate in a recorded interview, and with the aim of achieving diversity in demographics, IPV experience, and service receipt. All interviews were conducted by one of four masters- or doctoral-level interviewers experienced in interview methods on sensitive topics, in person at the local VHA facility (with the exception of one follow-up and qualitative interview conducted by telephone). Participants received $20 for completion of the baseline interview, $30 for the follow-up interview, and $50 for participation in a qualitative interview. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Crescenz VA Medical Center (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and the VA Portland Healthcare System (Portland, Oregon).

Methods

Tracking Recruitment Strategies

Our recruitment strategy underwent multiple revisions owing to logistical challenges and low yield with early recruitment efforts. Strategies used (discussed in more detail elsewhere in this article) included provider referral, in-clinic research team recruitment, direct mail outreach, and flyers for self-referral. We maintained detailed project administrative notes to track the strategy through which each participant was recruited, as well as the benefits and limitations of each strategy (reported in the Results). Additionally, for direct outreach to patients via recruitment letters, we tracked the number of letters mailed and the results of each step of follow-up contact by research staff.

Tracking Retention

At the time of enrollment, participants completed contact forms, listing preferred modes and times of contact, a safe person to contact in case they could not be reached at follow-up, and safety words to signal that it was not safe to talk or immediate help was needed. Research staff initiated follow-up contact 6 months after baseline. Participants were considered lost to follow-up if they were unavailable or unwilling to participate in the follow-up assessment, did not respond to follow-up contacts, or had not presented for a scheduled follow-up visit by 9 months after baseline.

Analysis of Interview Data: Experience of Study Participation

As part of in-depth, semistructured, qualitative interviews on experiences with IPV and related help seeking, participants were also asked about their experience of participating in the study, including what motivated them to participate and what it was like sharing their IPV experiences in the research context. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim; transcripts were coded utilizing Atlas.ti (Version 7) (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). We used a team-based inductive approach to data analysis (Thomas, 2006), including detailed coding, templates, and memoing, to identify themes that emerged from the data (Birks, Chapman, & Francis, 2008; Strauss, 1987).

Based on a review of early transcripts and overall study aims, the study team developed a codebook, including code names, definitions, and exemplar quotes from the transcripts. To establish consistency in code application among coders, rotating pairs of coders independently coded a subset of transcripts from each site; coders then compared their coding with their partner’s coding for the same transcript and noted discrepancies and questions, which were discussed with the larger team and resolved through consensus. This process was repeated until coders agreed that no further refinements to the codebook were needed and comparisons of coding revealed no more than stylistic differences.

After establishment of intercoder agreement, each transcript was assigned to a primary and secondary coder. The primary coder applied codes as defined in the codebook using line-by-line coding. The secondary coder then reviewed the coded transcript and provided feedback about areas of disagreement or oversight. Any unresolved differences were discussed with the larger team and resolved via consensus. The secondary coder/reviewer also drafted a templated summary of the interview; when viewed in a data matrix, summaries provided a quick overview of the overall dataset as well as the range of participant responses within particular topic areas.

The code for research experience, defined as “feedback and reflections on experience of participating in the study,” and the corresponding sections of the templated summary, served as the basis for the analysis presented here. Through a close review of these sections of the data, the investigative team identified key themes that were then further refined and elaborated through an iterative process of analytic memoing and team discussion to ensure that the full range of reported research experiences were conveyed by the thematic framing. The analytic process included an examination of the potentially dissenting experiences that disconfirmed or required expansion of preliminary themes to incorporate the full range of reported participant experiences.

Recruitment Strategies

Multiple recruitment strategies were used, sequentially or concurrently, to identify potential participants. To protect safety and privacy of potential participants, written recruitment materials did not specifically refer to IPV. Phone calls to potential participants followed a safety protocol to ensure sufficient privacy; once privacy was established, research staff provided details about the study, assessed eligibility, and scheduled study visits with eligible and interested patients.

Strategy I: provider referral

The initial recruitment strategy relied on health care providers referring potentially eligible patients to the research study. Providers in the women’s health clinics at the two participating facilities were asked to inform patients who disclosed recent IPV experience about the study and obtain their permission to refer them to the research team for further details. This strategy was selected to balance specificity in recruitment by targeting patients who had experienced past-year IPV with concerns for patient safety and privacy. With provider referral, patients would be aware that the study focused on IPV before any contact with the research team, and contact would be with prior patient permission. However, recruitment with this method was limited to patients who had disclosed IPV experience to their providers.

At the time of study initiation, both study sites had implemented routine IPV screening for all women patients in the clinic using a screening instrument embedded in the electronic health record. Our original plan was to modify this section of the electronic health record to add a prompt reminding providers to inform eligible patients about the study, and, with patient permission, allowing them to directly notify the research team of interested patients. Logistical barriers prohibited the implementation of these modifications, requiring providers to remember without prompting to mention and refer patients to the research study. High clinical demands and staffing turnover in the clinics presented challenges to both routine IPV screening implementation (which limited patient disclosure of IPV to health care providers) and referral to the study.

Strategy II: in-clinic research team recruitment

To enhance recruitment efforts and reach patients who may not have disclosed IPV experience to their providers, we implemented a second recruitment strategy involving research staff taking shifts in the women’s health clinic waiting rooms to directly inform patients about the study and collect contact information from interested patients for research team follow-up. Given the potential for lack of privacy in the waiting room, including the possibility that patients’ partners might be present, conversations with patients did not include specific details about IPV when others were present; instead, such details were discussed during the subsequent phone follow-up. This strategy, although resource intensive, allowed for initial contact between the research team and potential participants and eliminated reliance on clinical providers. However, neither strategy reached patients who did not present for care during the enrollment period.

Strategy III: direct mail outreach

To address challenges of in-clinic recruitment, we implemented direct outreach to potential participants by mail, followed by telephone contact to provide additional details and assess study interest and eligibility. Batches of 100–200 letters were mailed to patients who had visited the facility within the past 12 months and had a local address in their electronic health record; mailings continued until target enrollment was reached. The letters a) introduced the study without specific mention of IPV for safety considerations, b) invited recipients to contact the research team to either learn more, or to opt out of future contact, and c) informed recipients that the research team may follow up by telephone to provide additional information. This strategy had the benefit of direct contact between the research team and potential participants, and extended the reach of recruitment efforts to patients without clinic visits during the enrollment period.

Secondary recruitment strategy: flyers for self-referral

In addition to the primary recruitment strategies described, flyers were posted in clinical areas of the participating medical centers, inviting patients to contact the research team to receive additional information and, if eligible, volunteer to participate in the study.

Results

Recruitment and Enrollment Results

A total of 169 participants enrolled in the study and completed the baseline assessment. Only six participants, all from study site 1, were recruited through provider referral. Seven participants initiated contact in response to the recruitment flyer. Nearly one-third of participants (29.0%) were recruited through in-clinic research team recruitment, and nearly two-thirds (63.3%) were recruited via direct mailing (Table 1 provides details on participants recruited from each strategy, by study site; Table 2 presents participant characteristics).

Table 1.

Enrollment Results by Recruitment Strategy and Site

| Strategy | Site 1 (n = 88), n (%) |

Site 2 (n = 81), n (%) |

Overall (N = 169), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provider referral | 6 (6.8) | 0 (0) | 6 (3.6) |

| Flyer | 6 (6.8) | 1 (1.2) | 7 (4.1) |

| In-clinic research team recruitment | 30 (34.1) | 19 (23.5) | 49 (29.0) |

| Direct outreach letters | 46 (52.3) | 61 (75.3) | 107 (63.3) |

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Overall Sample (N = 169), n (%) |

Qualitative Sample (n = 50), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||

| 18–29 | 15 (8.9) | 7 (14.0) |

| 30–39 | 41 (24.3) | 11 (22.0) |

| 40–49 | 30 (17.8) | 13 (26.0) |

| 50–59 | 56 (33.1) | 16 (32.0) |

| ≥60 | 27 (16.0) | 3 (6.0) |

| Race | ||

| Black/African American | 66 (39.1) | 19 (38.0) |

| White | 70 (41.4) | 20 (40.0) |

| Asian | 4 (2.4) | 2 (4.0) |

| Native American | 3 (1.8) | 1 (2.0) |

| Multiple or other | 25 (14.8) | 8 (16.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Latina/Hispanic | 15 (8.9) | 5 (10.0) |

| Highest formal education | ||

| High school not completed | 3 (1.8) | 1 (2.0) |

| HS diploma or GED | 16 (9.5) | 2 (4.0) |

| Vocational training | 4 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Some college (no degree) | 72 (42.6) | 20 (40.0) |

| Associate’s degree | 29 (17.2) | 12 (24.0) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 31 (18.3) | 10 (20.0) |

| Master’s degree | 10 (5.9) | 4 (8.0) |

| Doctoral degree | 4 (2.4) | 1 (2.0) |

| Current financial situation | ||

| Can’t make ends meet | 33 (19.5) | 9 (18.0) |

| Just enough to get by | 99 (58.6) | 30 (60.0) |

| Comfortable | 37 (21.9) | 11 (22.0) |

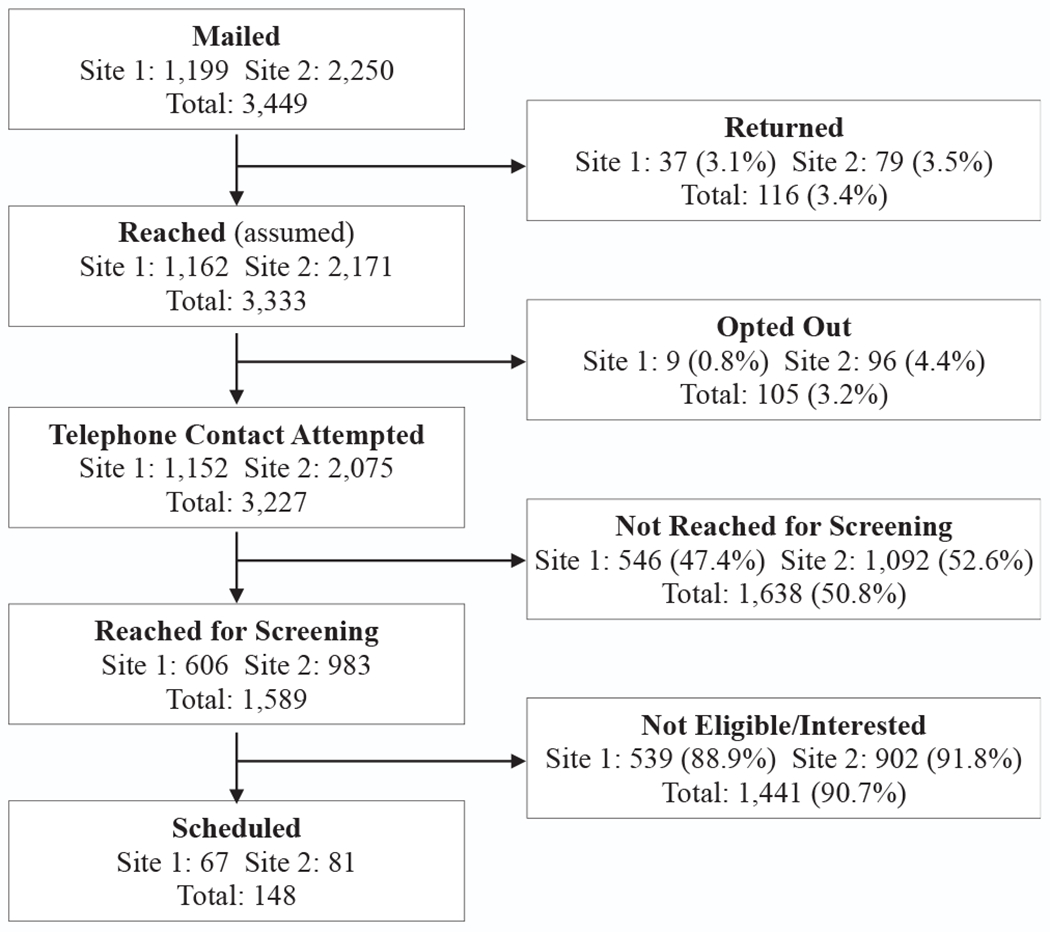

Letters were mailed to 3,449 patients across the two sites. Of these, 1,589 (46%) were reached by telephone and assessed for eligibility; 148 (9.3%) were both eligible and interested in participating. Thus, 4.3% of the letters resulted in individuals recruited to participate (the actual number of participants recruited via letters is smaller than the number reached via letters who scheduled visits owing to no shows or cancellations). Figure 1 provides a flowchart of the outcomes from this approach.

Figure 1.

Direct mail/contact from research team outcomes. Note: Site 1 required letter recipients to contact study team by telephone to opt out of further communication. Site 2 allowed for opt out via telephone, mail, or e-mail, likely accounting for higher numbers of individuals opting out in that site.

Retention Results

Of the 169 participants who completed the baseline assessment, a total of 149 (88%) completed the follow-up assessment. Of the 12% of participants lost to follow-up, 9 (45%) could not be reached to schedule a follow-up visit, 4 (20%) scheduled but did not present for a visit within the follow-up period, and 7 (20%) chose not to participate or were unable to attend a follow-up visit owing to having moved from the region (n = 3), time demands (n = 3), or poor health (n = 1).

Participation Experience Results

A total of 50 participants (25 per site) completed a qualitative interview at follow-up. Findings from qualitative interviews provide insight into participants’ motivations for enrolling in the study and their experience of participation. Themes, contained within four domains, are listed in Table 3 and described below, along with illustrative quotes from participants.

Table 3.

Participant Experience Results

| Theme Number | Theme Title | Theme Description | Example Quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Desire to help others as a motivation to participate | Participants wanted to share their experiences to help others facing similar experiences or challenges. | “If it’s going to help other women, then I’m willing to share.” |

| 2 | Participating in research interviews on IPV may have direct benefits for participants | Participants described the experience of sharing their own stories in this context as helpful for themselves. | “I like talking about my experiences because it helps me.” |

| 3 | Participating in research interviews on IPV can be emotionally straining | Participants commented that talking about their experiences with IPV was not always easy or comfortable. | “…when I have to talk about it – not have to – but when I address it, the emotions, the feelings are still right there.” |

| 4 | Comfort with the interviewer can facilitate participation and sharing | Participants attributed their willingness to open up in interviews to comfort with the interviewer. | “I feel like you are listening to understand not just listening to judge me or to diagnose me or anything like that.” |

Abbreviation: IPV, interpersonal violence.

Theme 1: desire to help others as a motivation to participate

Generally, participants indicated that they were motivated to participate and share their experiences in order to help others facing similar challenges. They stressed the need for greater attention to IPV by providers and the public (“It needs to be talked about. It needs to be exposed” [P11004]). Participants overwhelmingly indicated that they felt (and/or hoped) that their participation in the study may help others who have experienced or might experience IPV, even if they did not experience direct benefits. Participants stated, for example:

I think it might help somebody… It might even help me. (P11004)

If it’s going to help other women, then I’m willing to share. (P11006)

Hopefully whatever I contributed will help someone else down the line. (P11009)

Some participants expressed a sense of responsibility to speak out for others who, for various reasons, may not be able to share their voices:

This is not just about me. This is about all of us as women. This is about all of us as vets. If all of us as vets stay quiet, then we can’t help other vets that are either here with us now or that’s coming up. If we don’t talk about it, we can’t make it better for them, too… The only thing I was hoping to get out [of participating in the study] was my voice, and, like I said, to help someone else, because not everybody can talk about it. (P21002)

Participants appreciated the opportunity to provide feedback about existing services and offer input on how these could be made more responsive to the needs of people in similar situations:

It’s nice to every now and then have somebody stop and say, “Tell me about your experience. How has this been working for you? Has it been helping you? Is there something I can do to help you more?” And I think that’s a good thing because it helps… us provide better services for people that need them. (P21009)

This altruistic motivation to participate was inextricably tied to questions about how study results would be applied to programs, policies, or practice. Participants wanted to ensure that their contributions would be used to inform such efforts:

I just want to be able to help somebody. That’s why I ask, what happens in the end? Have I—or, what I said—made a difference for somebody else? (P11011)

Theme 2: participating in research interviews on IPV may have direct benefits for participants

In addition to positive feelings about potentially helping others with similar experiences, some participants expressed a sense of having benefited personally from participating in the study. Several participants described the experience of sharing their own stories in this context as “therapeutic,” “eye-opening,” and motivating to seek help and/or speak out further:

It was a great relief to share some of those things. I thought it would be hard, but, no, it was actually a relief. I think it was helpful. And it makes me think about seeking more help. (P11006)

I like talking about my experiences because it helps me. There are some things that I want—wish—I could forget that you just can’t. But at the same time, being able to talk about those things makes me stronger, makes me feel more confident in myself. (P20126)

I’m glad that I was approached [to participate in the study]. I’m glad that you all have taken the time. It’s made me incredibly introspective… So it’s been therapeutic for me to … think about the whole process. (P12005)

Responding to questions about violence in their relationships helped some participants to identify and reflect on trajectories and patterns in their relationships, and several women expressed a new sense of perspective on their own experiences as a result of study participation:

During the research, it made me dig deep… made me go home and realize there was something wrong… I think that this research experience made me look at myself in a whole different way. (P11008)

One participant described how her participation confirmed her decision to leave an abusive partner:

I got a lot in the study. It has me really thinking about that relationship and where it stands… Just sharing everything that I’ve dealt with in the last almost seven, eight, nine months, more than that, about almost a year, it’s shown me that it’s going downhill. It’s not uprising and uplifting and so my decision-making is good. (P11018)

Theme 3: participating in research interviews on IPV can be emotionally straining

Participants commented that talking about their experiences with IPV was not always easy or comfortable, yet also noted that they saw value in doing so—for others as well as for themselves:

Interviewer: What was it like to be asked these questions?

Participant: Like eating gravel. [laughter] …It was hard. And at the same time, it’s something that needs to be done. It’s something that it’ll make that next patient seem like more of a whole, than just addressing the parts… Hard, but necessary. (P21003)

Another participant noted that the research interview prompted greater awareness of the extent to which painful memories she thought she had laid to rest were still very much alive for her:

It’s been eye-opening because of how certain things still have an emotional effect on me. I thought I had convinced myself to get past these areas, but, yet, when I address it, the emotions, the feelings are still right there. (P11009)

When emotions were particularly raw, participation in the research interview could arouse challenging feelings:

The first [interview] was harder than the other two, and that’s because everything was more fresh. And I had not— I was not as strong as I am now. And so that one affected me for a few days after, as far as the emotion of it and the reliving of some of those circumstances. (P21017)

While recognizing that the interviews could produce feelings of emotional distress or discomfort (which was anticipated and noted in the informed consent process), no participants in the in-depth interviews indicated experience of severe emotional distress or disturbance as a result of participating in the research interviews.

Theme 4: comfort with the interviewer can facilitate participation and sharing

Characteristics of the interviewer and research staff involved in recruitment were important for participants’ willingness to share their experiences and perspectives. Some participants noted that they had shared information in the study interviews that they had not shared with others, including their health care providers, either because no one had directly asked about such experiences previously or because they had not felt comfortable sharing so openly in other contexts. In addition to feeling motivated to share for the sake of helping others in similar situations, participants attributed their willingness to open up during research interviews to the comfort they felt with the interviewer, whom they experienced as empathic, genuinely interested, and nonjudgmental:

It’s uncomfortable, especially at first. But then… I don’t get so uncomfortable. Maybe because it’s just how you are. I feel like you are listening to understand, not just listening to judge me or to diagnose me or anything like that. (P11016)

You’re comfortable to talk to. [It’s important to] make sure that people feel comfortable and they don’t feel interrogated. Because you already feel dirty. You already feel judged. You don’t wanna sit in a room and talk to someone and still let them question you in a way where you still feel like I’m being judged. So I liked this. This was comfortable. (P12002)

Further, some participants found that the time-limited nature and contained focus of the research relationship facilitated their sharing. Knowing that they would likely not encounter the interviewer beyond the study provided a sense of anonymity that eased concerns about shame and stigma; the research context also eliminated concerns about potential clinical action and/or documentation in response to disclosures.

It’s a relief to open up really and know that… I’m not seeing you every day, where I feel like, oh she’s seeing me and she knows all this about me. It’s different. And maybe that’s one of the reasons why it’s so hard for me to open up to friends or family. It’s like they know this about me. They know this. (P11021)

Discussion

This study contributes to knowledge on recruitment and research participation for women experiencing recent IPV. Our findings indicate that women who have experienced recent IPV may be willing and interested, even eager, to participate in observational research focused on IPV, even if the research does not necessarily offer any direct benefits to participants. However, successful achievement of recruitment targets may be impacted by the recruitment strategy used. In this study, direct recruitment by the research team had the advantages of allowing potential participants to learn about the study from the researchers and removing demands on clinical staff. Further, we found that participants were willing to share information with the research team that they were not necessarily willing to disclose to their health care providers.

Other studies among both veterans (Littman, True, Ashmore, Wellens, & Smith, 2018) and women who have experienced IPV (Logan et al., 2008) have also found altruistic motivations for participating in research and additionally noted the importance of compensation as an incentive to participate. Participants in our study did not indicate compensation as a key motivator to their willingness to participate; however, it is likely that the compensation did provide an incentive for our participants and is important in demonstrating respect for participants’ time and contributions. Furthermore, compensation can be a critical facilitator for inclusion of more socially disadvantaged or economically limited research participants who would not otherwise be able to participate owing to barriers related to costs, for example, of transportation or childcare (Logan et al., 2008; McFarlane, 2007).

The therapeutic effects of participating in research interviews or surveys on IPV were also found in a study using daily assessments (Burge et al., 2017); our findings demonstrate that such effects on participants’ perceptions, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors can occur after as few as one or two interviews. The positive experiences of research interviews as well as the strong retention rate likely reflect the skill of interviewers in demonstrating respect for the sensitive nature of the topic and avoidance of imposing judgement that may be experienced as shaming, stigmatizing, or misunderstanding. Prior studies have found that negative experience of reactions to IPV disclosures (including experience of judgment, stigma, indifference, and ignorant advice) inhibits further sharing (Dichter, Wagner, Goldberg, & Iverson, 2015; Spangaro, Zwi, Poulos, & Man, 2010).

Limitations and Considerations

This study had the advantage of being conducted within an integrated health care system, allowing the research team access to a list of the universe of potential participants along with their contact information. Additionally, study visits were conducted on site at the health care facilities, a location and system familiar to the participants. The lessons learned regarding recruitment challenges and successes may be idiosyncratic to the particular contexts and cannot necessarily be generalized to other studies or settings. In particular, women veterans receiving care from the VHA may have unique characteristics owing to experience of military service or perspectives or norms related to social participation that do not generalize to other populations.

As a criterion of eligibility, all participants had experienced IPV within the year before study enrollment; however, individuals experiencing severe levels of IPV may not have been able to participate in the study owing to limitations imposed by the experience of abuse. The experiences of study participation were collected only from the subset of participants who completed qualitative interviews; we do not know how their perspectives compare with the views of participants who only completed the quantitative portion of the study or who did not complete the follow-up assessment. At the time of the qualitative interviews, participants had already had one or two prior encounters with the research team; perspectives may differ depending on the number and timing of research encounters. Indeed, a few participants indicated increased comfort sharing with research staff at follow-up as compared with baseline encounters. We note that themes derived from our analysis of the qualitative data were not verified with participants and are subject to researcher interpretation based on understanding of the data.

The parent study was not designed as an intervention, although, as our qualitative data indicate, the process of the research interviews may have had therapeutic effects. Motivations for participation, experience of participation, and recruitment and retention may differ for interventional rather than observational studies.

Implications for Policy and/or Practice

These findings provide support for the feasibility and acceptability of engaging women survivors of recent or ongoing IPV in research focused on IPV. It is critical, however, to note that safety measures are of paramount importance when working with women who are at increased safety risk owing to IPV, and that interviewers and research staff must be well-trained and skilled in conducting this work in an empathetic, supportive, confidential, and nonjudgmental manner (Clough et al., 2011; Logan et al., 2008). Given that a discussion of IPV experiences can prompt motivation for further help seeking and may also bring up difficult emotions, it is important to provide research participants with information about accessing services and support.

Participants’ strong desire to help others through their participation in research may serve as a reminder to researchers, service providers, policymakers, and educators to work collaboratively toward the dissemination, uptake, and integration of empirical evidence in their respective fields of practice. Furthermore, given participants’ interest in how study findings might be used, it is important for researchers to consider mechanisms for sharing findings and implications with participants and other stakeholders beyond the typical academic channels (McDavitt et al., 2016). The therapeutic potential inquiry and talking about IPV experience may hold implications for clinical responses to IPV: increasing opportunities for individuals to share their experiences in a safe context to a sensitive, interested, and nonjudgmental listener may improve self-reflection and foster motivation to seek change or further support.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge contributions of Ryan Bender and Shannon Ogden to recruitment and data collection.

Funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development, IIR 15–142 (Dichter). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or U.S. Government.

Biographies

Melissa E. Dichter, PhD, MSW, is a Core Investigator, VA Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion (CHERP) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Assistant Professor in Family Medicine and Community Health at the University of Pennsylvania. Her expertise is in intimate partner violence.

Anneliese Sorrentino, MSS, MFT, is a Program Specialist at the VA Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion (CHERP) and a Staff Therapist at Council for Relationships in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her research and clinical interests include trauma, adaptation, and healing relationships.

Terri N. Haywood, MS, MPH, is a Health Science Specialist and Project Manager at Atlanta VA Health Care System in Decatur, Georgia. Her research interests include women veterans, adverse childhood experiences, and perceived discrimination and health outcomes.

Anaiïs Tuepker, PhD, MPH, is a sociologist with the Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care (CIVIC) in Portland, Oregon. Her work examines interprofessional team dynamics in health care, social determinants of health, and improving care for marginalized veterans.

Summer Newell, PhD, MPH, is a Research Associate at the Center to Improve Veteran Involvement in Care (CIVIC) in Portland, Oregon. Her research focuses on women recently released from the criminal justice system.

Meagan Cusack, MSc, is a Program Specialist at the VA Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion (CHERP) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her research interests include homelessness, housing instability, and social determinants of health.

Gala True, PhD, is an investigator with the South Central Mental Illness Research and Education Center at the Southeast Louisiana Veterans Health Care System and Associate Professor of Community and Population Medicine at Louisiana State University School of Medicine.

References

- Birks M, Chapman Y, & Francis K (2008). Memoing in qualitative research: Probing data and processes. Journal of Research in Nursing, 13, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, … Stevens MR (2011). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Burge SK, Ferrer RL, Foster EL, Becho J, Talamantes M, Wood RC, & Katerndahl DA (2017). Research or intervention or both? Women’s changes after participation in a longitudinal study about intimate partner violence. Families, Systems, & Health, 35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough A, Wagman J, Rollins C, Barnes J, Connor-Smith J, Holditch-Niolon P, … Glass N (2011). The SHARE project: maximizing participant retention in a longitudinal study with victims of intimate partner violence. Field Methods, 23, 86–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dichter ME, Cerulli C, & Bossarte RM (2011). Intimate partner violence victimization among women veterans and associated heart health risks. Women’s Health Issues, 21(4 Suppl), S190–S194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter ME, Wagner C, Goldberg EB, & Iverson KM (2015). Intimate partner violence detection and care in the Veterans Health Administration: Patient and provider perspectives. Women’s Health Issues, 22, 555–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter ME, Sorrentino A, Bellamy S, Medvedeva E, Roberts CB, & Iverson KM (2017a). Disproportionate mental health burden associated with past-year intimate partner violence among women receiving care in the Veterans Health Administration. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30, 555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter ME, Wagner C, Borrero S, Broyles L, & Montgomery AE (2017b). Intimate partner violence, unhealthy alcohol use, and housing instability among women veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Psychobgical Services, 14, 246–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Holtzworth-Munroe A, Jouriles E, McDonald R, & McFarlane J (2003). Recruitment and retention in intimate partner violence research. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Frayne SM, Carney DV, Bastian L, Bean-Mayberry B, Sadler A, Klap R, … Lin JY (2013). The VA women’s health practice-based research network: amplifying women veterans’ voices in VA research. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28, 504–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littman AJ, True G, Ashmore E, Wellens T, & Smith NL (2018). How can we get Iraq- and Afghanistan-deployed US Veterans to participate in health-related research? Findings from a national focus group study. BMC Research Methodology, 18, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, Walker R, Shannon L, & Cole J (2008). Combining ethical considerations with recruitment and follow-up strategies for partner violence victimization research. Violence Against Women, 14, 1226–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDavitt B, Bogart LM, Mutchler MG, Wagner GJ, Green HD, Lawrence SJ, … Nogg KA (2016). Dissemination as dialogue: building trust and sharing research findings through community engagement. Preventing Chronic Disease, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane J (2007). Strategies for successful recruitment and retention of abused women for longitudinal studies. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 28, 883–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangaro JM, Zwi AB, Poulos RG, & Man WYN (2010). Who tells and what happens: disclosure and health service responses to screening for intimate partner violence. Health & Social Care in the Community, 18, 671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DR (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative e valuation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Treweek S, Lockhart P, Pitkethly M, Cook JA, Kjeldstrøm M, Johansen M, … Mitchell ED (2013). Methods to improve recruitment to randomised controlled trials: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 3(2), e002360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]