Abstract

In presence of violent extremism, children in Pakistan are at high risk for child sexual abuse (CSA), especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. Effective approaches for preventing CSA include enhancing resilience resources in violence-affected societies. Previous research suggests that video-based curricula effectively enhances learning in primary schoolchildren. We pilot tested a video literacy program to build awareness in children, creating a ‘personal safety and space bubble’ as an educational approach for prevention of sexual abuse with an experimental 6 weeks long pre- and post-test design. We conducted qualitative interviews with students, teachers, and parents and identified themes using frequency analyses. Results showed a 96.7% increase in awareness about ‘personal safety and space bubble’. The pilot study is valuable for public health researchers and policy makers seeking to curtail sexual abuse in extreme violence affected Pakistan. Primary schools can use such interventional cartoons to enhance awareness about child sexual abuse.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1057/s41271-023-00408-7.

Keywords: Child sexual abuse (CSA), Video literacy, Cartoons, Resilience, Violent extremism, Sexual abuse awareness

Key messages

COVID-19 has exacerbated risk of child sexual abuse in terror-stricken countries like Pakistan that are fighting violent extremism.

Increasing awareness in children about personal rights, their ‘space bubble’ and safety through animated cartoons proved effective in a Pakistani pilot video literacy program.

We recommend video literacy programs for primary school curriculum to mitigate risk of sexual abuse, develop emotional resilience and awareness.

Introduction

According to the Human Rights Watch [1], child sexual abuse (CSA) in Pakistan remains disturbingly common with 6 daily cases reported across Pakistan in the first half of 2020. In the first 6 months of 2020, The News International, a national news outlet, reported at least 173 children had been gang-raped, and 227 had been victims of attempted sexual assault. Of the total reported sexual abuse cases, 47% were boys and 53% were girls [2]. Cases remain consistently under-reported in Pakistan [3]. Cultural, religious, legal, state, and gender or sexual barriers exacerbate stigma associated with seeking proper help [4]. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidence of child sexual abuse in Pakistan increased by 30% in 2021 compared to the previous year. Surges in ‘dark web’ (a collection of hidden internet sites only accessible through specialized soft-wares to maintain anonymity) gangs dealing in child pornography and lockdowns during the pandemic were correlated to the increased incidences of child sexual abuse. During this time, children’s internet usage increased, and supervision decreased, while Pakistan closed schools [5]. Sustainable Social Development Organization (SSDO), a non-governmental organization, reported an increase in rates of domestic violence including CSA almost 400% in one quarter during the COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020 in Pakistan [6]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, parents in Pakistan reported adverse effects on their children’s mental health, including increased aggression and anxiety [7].

The term ‘child sexual abuse’ or CSA characterizes a traumatic and abusive experience among younger children and teens including sexual assault, rape, and incest, and commercial sexual exploitation of minors. CSA may include any sort of sexual act between an adult and minor, or between two minors, where one uses power to exert dominance over the other. The term indicates that a minor is coerced or persuaded to perform or engage in any sort of sexual act. CSA also covers acts without contact, such as exhibitionism, being exposed to pornography, voyeurism, and communication in a sexual manner through the phone, other digital devices, or otherwise [8]. CSA perpetrators include a broad variety of offenders including men and women, strangers, trusted family, friends, family friends, people of all sexual orientations, and from all socio-economic classes and cultural backgrounds. The World Health Organization’s definition of CSA emphasizes the involvement of a child in a sexual act (direct or non-contact) without the child’s full comprehension, informed consent, or developmental preparedness to give consent. Thus, all sexual acts between an adult and minor (even with ill-informed assent) is by definition child sexual abuse [9]. In most countries, acts described here amount to crimes for which perpetrators may be punished by law.

Another key concept for understanding and responding to child abuse is violent extremism. This term connotes that children’s psychological health is compromised, even if they are passive agents in the affected community. Groups that perpetrate violent extremism may go so far as to recruit children at an impressionable and developmentally vulnerable age and subject them to various forms of abuse. Hence, risks for children sexual abuse increase markedly with the element of violent extremism [10]. By subjecting children to violence and witnessing its effects, perpetrators also inflict emotional abuse, whereby the children lose the ability to regulate their emotions effectively and may consider violence as an accepted form of retaliatory behavior as they become de-sensitized to it [10, 11]. Children at risk of sexual abuse are often subjected to other forms of abuse or neglect, such as insufficient family support, high stress households (due to poverty), parental substance abuse, low levels emotional support and warmth, among others. Not infrequently, these children develop learning or physical disabilities, mental health issues, and may resort to substance abuse. These risks increase as children enter adolescence. Emancipated children or others living out-of-home become vulnerable to sex trafficking and sexual acts exchanged for contributions to meeting basic survival needs such as food, shelter, money, or drugs. Children living in a terror-stricken or conflict-ridden society experience higher risks of sexual abuse than their counterparts in safer settings [9, 10]. The psychological trauma and harm that children may encounter while entrenched in affected communities, results in long-term consequences to their physical health, as well as moral and psychological health [10].

People younger than 19 years of age comprise more than 52% of the Pakistani population and these young people spend most of their time outside their homes in educational establishments. Thus, prevention programs in the early years of school present a viable opportunity for intervention. A review by Ali [12] postulates a dire need for improving national legislation to protect children from sexual abuse, made more urgent by increasing incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous research shows that videos, animations, cartoons, and various multimedia approaches are effective for enhancing children’s learning [13–18], including use of multimedia to increase child sexual abuse awareness [19, 20]. Multiple stimulatory channels (audio and video) increase information retention [21]. Traditional classroom learning may be monotonous compared to videos and cartoons for reducing children’s anxiety, stress and managing disruptive behavior in class [16].

Thus, we undertook a video literacy pilot program for primary school children to build awareness in children about their personal safety and ‘space bubble’ as a means to prevention of sexual abuse. We used the term ‘space bubble’ with the children to make the content more age-appropriate and to avoid any confusion. We used a pre- and post-test experimental design to study the efficacy of the program for enhancing awareness and emotional resilience against sexual harassment, including that provoked by extremist elements in society. This pilot program addresses the issue of violent extremism by measuring awareness in children about their rights while educating them to draw on resilience in these situations to equip them to deal with extremist influences or perpetrators of sexual assault later in life.

Data and methods

Ethical approval and considerations

We initiated a video literacy program to pilot with a sample population of two primary schools in the Islamabad-Rawalpindi region of Pakistan: one private (Islamabad) and one public (Rawalpindi). We discussed the study design and objectives in detail with the schools’ higher management and they agreed and signed formal agreements and Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs). Due to COVID-19 protocols, the schools alternated between 1 week online and 1 week on campus. Thus, the school needed to provide access to the researchers to join online classes with the students in the presence of the teacher. Schools needed to permit a researcher to sit in the class, observe and record qualitative data from students, teachers, and parents. The school and the concerned teachers had to agree to participate in training for the exercises using the special cartoons. Children and their parents participated only if they agreed to be part of the study and signed consent forms, one for the students, and another for parents. Due to the sensitive content of sexual abuse that could trigger an unwarranted reaction in some students, parents and the teachers ensured that students with mental health issues or who were under treatment would not participate. We also excluded any parents and students who did not want to partake in the study. We minimized researcher-based bias by assuring presence of at least 2 researchers and an assigned teacher for daily observation.

At each stage, we maintained complete transparency with the school administration about the tools and methods. We ensured anonymity of the data and integrity by assigning a code name to every student, parent, and faculty member. We designed the study prior to COVID-19, but the pandemic hit as we began collecting data, thus we adapted the protocol. The schools, and the research grant awarding body granted ethical approval of all protocols.

School selection, enrollment, and randomization

We selected schools in Islamabad/Rawalpindi region of Pakistan due to pilot study’s financial and geographical limitations. In two selected schools, students shared similar socio-economic background, with middle white collar, working-class parents. To ensure sufficient pool of students for randomization into control and experimental groups we sought schools with 80 or more primary school children.

The school administration randomly assigned students aged 9–12 to the experimental (N = 120) and control (N = 40) groups as displayed in (Table 1), ensuring that no profiling (assigning good scoring students to experimental group and average scoring students to the control group and vice versa) is done. Experimental and control group students did not interact with each other because one group was on campus and the other at home based on the already-in-place COVID-19 school protocols.

Table 1.

Age and gender distribution of students in experimental and control groups

| Age (years) | Experimental group | Control group |

|---|---|---|

| 120 (M = 59, F = 61) | 40 (M = 15, F = 25) | |

| 9 | 19 | 7 |

| 10 | 80 | 24 |

| 11 | 19 | 7 |

| 12 s | 2 | 2 |

Intervention: the animated cartoon entitled ‘Right to safety and space bubble’

Our intervention focused on anti-sexual exploitation awareness—keeping in view the cultural and religious sensitivity. We never used the word ‘sexual exploitation’ to avoid controversies and be age-sensitive. ‘Right to safety’ and ‘personal safety’ was used interchangeably, however the conversation with students mostly dealt with the concept of their ‘space bubble’. We consulted specialists, clinical psychologists, neuroscientists, and EI researchers, to develop the storyline, and to anticipate the effect on a victim, and the ‘bystander effect’for our interventional cartoon based curriculum. A senior Professor of Clinical Psychology with years of professional experience in play therapy vetted the final storylines. Animators then worked from these to develop the cartoon. We signed a non-disclosure agreement to ensure that the cartoons would not become available online (to avoid potential for parental intervention that could have biased results). The research team controlled the screen to restrict access to others, including parents.

Measurement scale

We used the 10-question Children’s Knowledge of Abuse Questionnaire [22] to assess students’ awareness of personal rights and safety both before and after the intervention. Students answered whether they felt the statements were correct or incorrect. We compared the percentages of correct responses in the pre- and post-intervention for both experimental and control students.

Pre- and post- data collection and analysis

We conducted qualitative interviews with students, teachers, and parents of experimental and control groups to understand the pre- and post-test comprehension of child sexual abuse and subjective changes associated with the intervention.

We administered a pre-test questionnaire to the experimental and control groups. To build rapport during the pre-test phase, we began with enjoyable ‘ice breaker’ conversations so the students, then at ease, could talk about their experiences and learning on the sensitive topic.

We then engaged the experimental group in 6 weeks of intervention (30 sessions in 1-h units, 5 days a week). The experimental group students watched the animated cartoon daily, then did exercises including answering questions, drawing, participating ‘in role plays’, discussions, and entertaining activities to keep students engaged and motivated. We used special props we designed to re-enforce the concepts. Practical demonstrations of their ‘space bubble’ i.e. a one-arm distance around them, was repeatedly given. We also administered written and oral exercises we had formulated to enhance the video-literacy curriculum.

At the end of the 6 weeks, we administered post-test questionnaires with students, parents, and teachers. We did not apply any intervention to the control group but did administer the post-test assessment. We also asked parents to report on any change in the behavior of their children during and after the intervention, nothing more.

We then anonymized and analyzed data. We used McNemar’s Test for Paired Samples Proportions for pre- and post-test measures of correct responses using SPSS. We used NVivo to analyze themes from the interviews and Frequency Analyses. We illustrated answers for representative qualitative questions by populating ‘word clouds’ which indicate frequency of answers by size of the words.

Results

Students

We assessed the results of testing with an adapted version of the Children’s Knowledge of Abuse Questionnaire as the percentage of correct answers to simple statements related to questioning good and bad touch, asserting their personal ‘space bubble’ and speaking up against perpetrators. Table 2 shows the correct response percentages both pre- and post-test of students in the experimental and control groups. For the former, all responses to the statements changed after the intervention (all p < 0.05). The findings suggest that the intervention was effective in dispelling some previously held notions about violation of safety and personal rights. The control group students did not show any difference in their correct response percentages (all p > 0.05, McNemar’s Test with binomial distribution used, Table 2).

Table 2.

Percent of correct responses to the Children’s Knowledge of Abuse Questionnaire (CKAQ) Items in pre- and post-test in experimental (N = 120) and control (N = 40) groups

| Experimental (N = 120) | Control (N = 40) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statements | Pre-test correct (%) | Post-test correct (%) | McNemar’s χ2 (p value)* | Pre-test correct (%) | Post-test correct (%) | McNemar’s test p value** |

| 1. You always have to keep secrets | 55.8 | 36.7 | 7.68 (0.005) | 25.0 | 30.0 | 0.824 |

| 2. Sometimes it’s OK to say ‘no’ to a grown-up | 45.8 | 78.3 | 21.55 (< 0.001) | 57.5 | 52.5 | 0.815 |

| 3. Even hugs and kisses can turn into not OK touches if they go on too long | 50.8 | 87.5 | 31.88 (< 0.001) | 77.5 | 72.5 | 0.774 |

| 4. If a grown-up tells you to do something you always have to do it | 38.3 | 15.0 | 15.19 (< 0.001) | 27.5 | 22.5 | 0.804 |

| 5. Even someone you like could touch you in a way that feels bad | 44.2 | 87.5 | 43.35 (< 0.001) | 62.5 | 62.5 | 1.00 |

| 6. You have to let grown-ups touch you whether you like it or not | 30.0 | 7.5 | 17.33 (< 0.001) | 12.5 | 20.0 | 0.549 |

| 7. If someone touches you in a way that does not feel good, you should keep on telling until someone believes you | 62.5 | 83.3 | 11.76 (< 0.001) | 72.5 | 72.5 | 1.00 |

| 8. Someone you know, even a relative, might want to touch your private parts in a way that feels confusing | 50.8 | 73.3 | 9.52 (0.002) | 62.5 | 65.0 | 1.00 |

| 9a. If someone touches you in a way you don’t like, it’s your own fault | 42.5 | 26.7 | 6.89 (0.008) | 17.5 | 35.0 | 0.092 |

| 9b. Some touches start out feeling good then turn confusing | 39.2 | 80.8 | 35.31 (< 0.001) | 55.0 | 47.5 | 0.678 |

| 10a. If someone touches you in a way you don’t like, you should just keep quiet about it | 30.8 | 8.3 | 16.49 (< 0.001) | 12.5 | 22.5 | 0.344 |

| 10b. Sometimes someone in your family might want to touch you in a way you don’t like | 35.0 | 54.2 | 7.45 (0.006) | 35.0 | 22.5 | 0.332 |

*McNemar’s Test for difference in Proportion of correct and incorrect answers in pre- and post-test, N = 120, p < 0.05 considered significant

**McNemar’s Test for difference in Proportion of correct and incorrect answers, with binomial distribution, in pre- and post-test, N = 40, p < 0.05 considered significant

We posed a baseline qualitative question about the student’s awareness of their personal safety and ‘space bubble’ during the pre-test; none of the students replied ‘yes’. After the intervention, 96.7% of the students in the experimental group replied in the affirmative and were, in varying degrees, able to define the term ‘space bubble’.

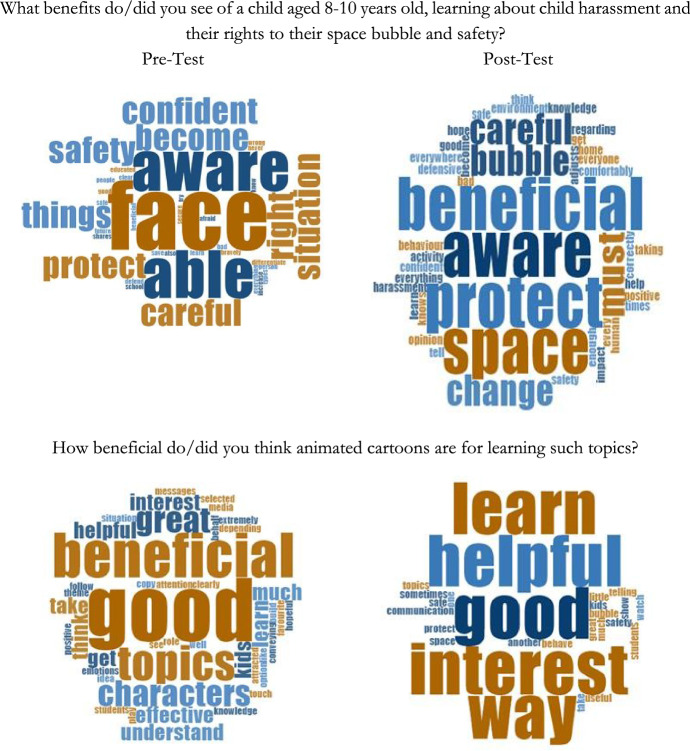

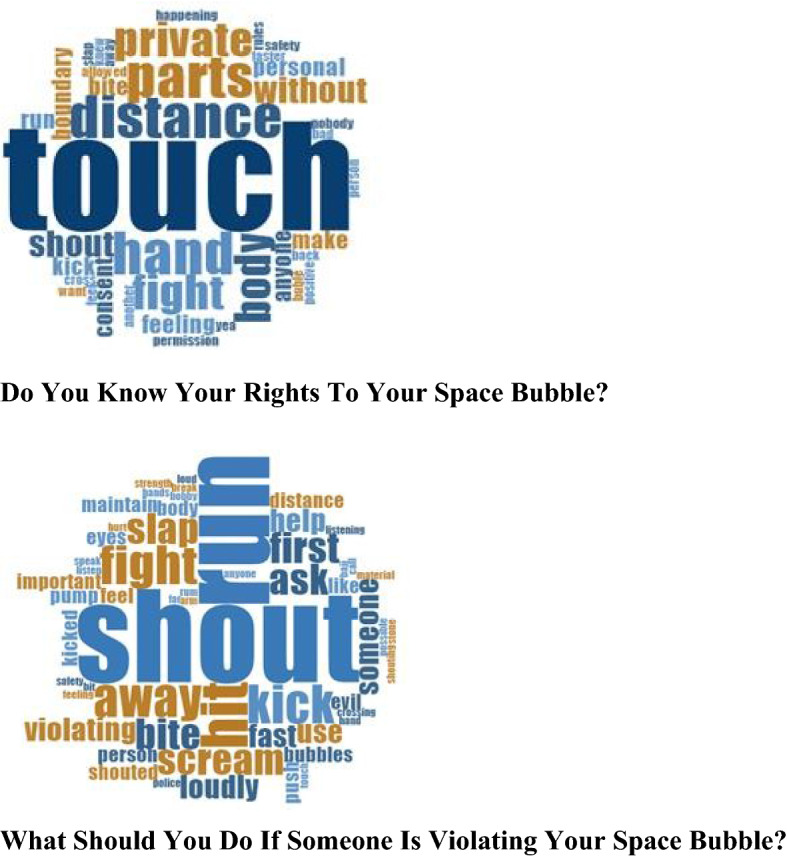

The experimental group students also answered qualitative questions related to the cartoon storylines, with moral reasoning prompts. Their responses illustrate their understanding of the concepts and clarity about what to do in situations involving harassment and violation of personal space (See Supplemental Material). Figure 1 contains representative questions and their respective word cloud answers.

Fig. 1.

Children’s qualitative response word clouds for cartoon-related questions

During the intervention, the students engaged increasingly with the cartoon and discussed their own experiences more openly–about dealing with strangers, feelings of discomfort, and ways they had defended themselves in the past. By the end of the program, the students demonstrated the one-hand distance rule that they had learned during the intervention to indicate the extent of their space bubbles. One student clarified that “Our space bubble is a hand-distance from your left, right, front and back and no one can enter it without our consent.” Towards the conclusion of the program, several students narrated some personal incidents: 3–4 students described how strangers had offered them food outside their schools, and how they had refused. Another student commented on precautions, such as making sure no one would follow students to their homes. Students were also made aware what they can do to save themselves, strategies like assertively saying no, shouting, seeking help from elders and running away from danger etc. were discussed.

Parents

We illustrate parents’ qualitative responses in the word clouds in Fig. 2. When asked “After the activity, has your child opened up about abuse, bullying or mean behavior by other children during school or otherwise?” of the experimental group parents, 66% replied in the affirmative. Although 89% of the parents interviewed had already said ‘yes’ to “Do you think educating your children about harassment and knowledge about sexual abuse is beneficial?” before the intervention, the percentage rose to 94.6% after. We asked the parents during the post-test “Have you observed any positive changes in your child's behavior during and after the activity?” Although the majority (41.4%) did not observe any notable change, some noted a slight shift; 29.3% of the responding parents indicated that there have been some positive changes. During interviews, several parents affirmed that it was very beneficial for their children to learn about safety and personal rights and that these children felt safe talking to their parents about this topic after the activity.

Fig. 2.

Parent’s word cloud responses to selected questions in the pre- and post-test evaluation

Teachers

The teachers also reported differences in children’s behavior regarding the cartoon theme. According to the participating teachers (n = 4), 10% of the experimental group children improved very little, 22.5% improved moderately, and the majority (67.5%) of the students improved a great deal. Teachers reported that the students were much more responsive and open to discussing their personal rights and safety bubble after the intervention as many understood the key concepts and had words to express their concerns. After the intervention, about one third of the experimental group students were willing to talk about instances of harassment or exploitation. No such discussions took place during the pre-test, even when researchers asked students about such instances.

Discussion

The presented study employed a most effective medium, cartoons [13], to teach students about safety and mitigating sexual exploitation. Teaching primary school children about sexual abuse has been difficult, given a taboo against doing so in Pakistani society. The current project aimed to test children’s knowledge levels about sexual abuse before and after an intervention using a structured quasi-experimental and multi method approach. Previous studies, including that of Hyder and Malik [23] highlighted the gravity of child sexual abuse in Pakistan and called for awareness and safeguarding the rights of the children. But the majority of these studies were observational, without rigorous research protocols or data collection.

It is the magnitude of the child sexual abuse problem in Pakistan that makes effective intervention so important. According to estimates, as many as 15–25% of children are subjected to sexual abuse. A study of 300 school-going children in the Islamabad/Rawalpindi area found 17% to be survivors of sexual abuse (1 in 5 boys, and 1 in 7 girls), the majority of whom (72%) were under the age of 13 [24]. Our interviews also revealed that at least one quarter of the experimental group students had experienced some form of sexual abuse or harassment. Using our approach to help students understand the gravity of the situation, we observed that in our sample of 120 students, around 30 students had experienced harassment or perpetrating behavior from strangers. One reason for this difference from previous studies was the inadequacy of sample sizes and study design.

News reports allow us to gauge the scale of child sexual abuse in Pakistan, but apart from those, Pakistan lacks reporting and methodological means to assess the incidents more accurately [4]. According to a review of child sexual abuse prevalence studies by Townsend and Rheingold [8], about 1 in 10 children is likely to be sexually abused before their 18th birthday. Girls experience more contact sexual abuse before they turn 18 than boys: 1 in 7 girls and 1 in 25 boys. Prevalence studies raise concerns about the validity and reporter biases [9]. We believe under-reporting of such abuse in Pakistan’s statistics obscures the magnitude of the problem and inhibits formulation and management of more effective policies.

A non-government organization, Sahil, reviewed national and local news and reported 3445 cases of child abuse in 2017, with an estimate that for 28% of these cases, no one reported them to the police, or the police themselves refused to register them. Such under-reporting is exacerbated by absence of mandatory reporting of sexual abuse in Pakistan. Pakistan has no legal definition of child abuse and neglect; it relies on WHO definitions and classification [3]. Pakistan struggles to address the problem as do most developing countries in Asia. Hindrances are many: legal, state, religious, cultural, family, and sexual or gender barriers. Rights of children are protected in the Constitution, but because of the stigma, lack of education, lack of human development infrastructure and the children’s vulnerable stage of development, the problem is still prevalent [4].

Pakistan has an infamous history of violent extremism and efforts to prevent it. The country has served as a front-line location for anti-terrorism efforts but other countries also perceive it as a sponsor for international terrorism, especially after the events known as ‘9/11’ in 2000 [25]. Pakistan suffers a substantial economic burden based on this history, even as its residents bear the brunt of psychological impact of terror [26]. Children and young adults are especially vulnerable as targeted populations as terrorists aim attacks on educational institutes [27]. They are also at a malleable developmental stage of psychological and moral development [28].

Unfortunately, scarce data exists on the impact of violent extremism on child sexual abuse related incidents in Pakistan. Violent extremism groups recruit and lure children to join them, then subject them to sexual abuse, using coercive powers to exploit their vulnerabilities. Some argue that child sexual abuse is a consequence of violent extremism [10]. Children raised in abusive environments caused by violent extremist groups are more likely to show violent behaviors than children in normal, unaffected households and may become perpetrators of sexual abuse [9, 10].

Using education as means to prevent and counter devastating psychological and physical effects of war or terror-related activities on children is very effective [29–33]. An approach used to prevent violent extremism is that of enhancing resilience and cognitive resources in already affected individuals [34, 35]. Sas et al. suggest that investing in primary education is beneficial as the children’s behavioral development starts to progress at this stage [36]. Shah et al. proposed that to improve children’s psychological wellbeing and diminish fear of terrorism in Pakistan, it is useful to engage them in emotional intelligence training with the help of teachers, parents, and counsellors [28]. Such training helps children to learn how to regulate their emotions when faced with adversity or stressful situation [37–40].

Developmentally, children who are abused may resort to regressive behaviors such as bed-wetting, changes in personality and emotional maturity, withdrawal, sleep and appetite disturbances, and even inappropriate sexual activity. In the long term, child sexual abuse survivors may experience post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression, substance abuse, or suicidal tendencies [41]. They remain at risk of heightened sexual activity and sexual abuse later in life [42]. Their neurodevelopmental progress may also be affected. Structural and functional MRI studies have shown substantial differences in the brain scans of child victims of abuse compared to their non-abused peers [43]. Evaluation of education programs for prevention of sexual abuse to increase children’s knowledge of the risk and enhance their self-protection skills showed positive results [44]. A study in Malaysia evaluated the level of awareness in children about sexual abuse using persuasive multimedia learning applications. It found benefits of multimedia approaches in increasing awareness and pointed to a lack of educational materials for teaching children about personal safety [19, 45]. In an interventional study performed by Naeem et al. [41] from March through June of 2018, the researchers engaged women primary school teachers in a health education program centered on child sexual abuse. Comprehensive presentations characterized the teaching and the curriculum included videos and written educational materials. A pre- and post-test comparison showed that the health education intervention program was instrumental in dispelling teachers’ misconceptions about child sexual abuse and increased their awareness and knowledge of child sexual abuse [41].

The Child Protection and Welfare Bureau in Punjab, Pakistan has had some success in enabling curriculum changes in the province but much more can be done in with curricula in educational settings to address the sexual abuse in Pakistan [4]. Use of multimedia to create awareness about CSA has been effective, however, there is still a lack of well researched educational materials that teach about personal safety [19, 45].

This study tried to fill a gap to help students to protect themselves by creating a well-researched video literacy tool validated by subject matter experts. The presented study is helping students to retain the learning from the intervention, a step toward helping students to develop emotional resilience and safeguard themselves. Our data indicate that 96.7% of the experimental cohort students had learned the concept of personal safety and ‘space bubble’ to avoid sexual abuse. Similar studies seldom measure the actual efficacy experimentally. Thus, future studies can build on this pilot, with sound methods and a proven curriculum. Additional programs and curricula improved through future research will help children become more resilient in the long run.

Our research team learned that the students were more responsive during the in-person sessions, rather than during the online sessions. In-person sessions featuring discussions and role-playing create a more favorable atmosphere for increasing open communication. Parents reported that their children were enthusiastic and looked forward to each session. Teachers also looked forward to the classroom sessions and students asked them if the cartoons were available on the internet. We believe that the most important change by the end of the program was the notable increase in children’s capacity to talk about abuse or harassment they had experienced. At the start, no student had heard the term ‘space bubble’, nor did they have any strategies to protect themselves.

We were aware of the sensitive nature of the content, so we developed the cartoons with special focus on the character likeability, their indigenous nature, with relatable dialogues––while capturing the root issues like consent, personal space and learning when to say no. Since these things resonated with the children quite quickly, their learning curve was very impressive. They had embraced the increasingly familiar characters in the cartoons and were starting to embody their positive characteristics. The children’s positive response is evidence that developing relatable and dialogue-driven storylines to convey content related to emotional resilience and awareness of children’s rights is an effective and rewarding experience for children and can serve the education sector. By the end, most of the experimental group students demonstrated their own space bubbles and knowledge about their rights. With CSA cases rising consistently in Pakistan over the years [24], educating the children as well as giving them a learning medium which they enjoy is vital.

We take a step forward towards understanding child sexual abuse in Pakistan. Our unique research-based intervention to teach children about their personal safety and space bubble, allowed for educating children about where to seek help if they feel uncomfortable around a possible perpetrator. Even a pilot program with 6-weeks of carefully curated research-based content showed clear enhancement in children’s awareness about sexual abuse. We recommend inclusion of this type of video literacy program in the future. Owing to the nature of the experimental design and the restrictions placed on the study design due to COVID-19 protocols, more studies with longer duration, in-person sessions, larger sample sizes and more content addressing more themes of emotional resilience are warranted. This media approach to enhancing emotional resilience may be the most rapid and effective way to address violent extremism for the future generations. An age-appropriate theme and carefully validated content can make the learning experience enjoyable and retain the learning throughout their developmental years.

Conclusions

Results are sufficiently encouraging to warrant a full-scale study to validate the current findings. We recommend that more studies to replicate the results of the pilot study at a larger scale for validity and generalization of the results. Future studies should incorporate students from a wider socio-economic and geographical stratum to inform directions for policy recommendations for curriculum development. Public education campaigns have the potential to destigmatize child sexual abuse, when used in a setting designed to protect children, a setting where adults are increasingly aware of ways to report, register and initiate response protocols on site. Programs like this can act as case studies of how to navigate methodological and cultural barriers in implementing child sexual abuse awareness in societies where the subject may be sensitive in nature.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The data analysis was done by the firm CBSR.

Biographies

Faryal Razzaq

Ph.D. is Managing Director, Centre for Ethical Leadership at the Karachi School of Business and Leadership (KSBL). She is also the Founder and CEO of The FEEEL (Pvt) Ltd.

Amna Siddiqui

M.Sc. is Research Executive at The FEEEL (Pvt) Ltd as Research Executive.

Sana Ashfaq

is a MBBS doctor is working as House Officer at Islamabad Medical and Dental College, Pakistan.

Muhammad Bin Ashfaq

is a second year MBBS student at the Rawal Institute of Health Sciences, Pakistan.

Funding

This experimental research was funded by the Pakistan Community Resilience Research Network grant (RGIK-14.2) from Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI), Pakistan and Creative Learning, USA.

Data availability

We are very open and assure that we will provide any original data sheets if required. That the data was authentic and collected and analysed through highest research standards. All the other authors contributed towards, data collection or literature review etc. We hope that this research-based video literacy program can be adopted widely to create awareness and understand predatory behaviours and know safety tips for school children.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Faryal Razzaq, Email: faryalrazzaq11@gmail.com.

Amna Siddiqui, Email: amna.siddiqui.92@gmail.com.

Sana Ashfaq, Email: sanaashfaq.18@imdcollege.edu.pk.

Muhammad Bin Ashfaq, Email: muhammadbinashfaq7403@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Human Rights Watch. World report 2021: rights trends in Pakistan; 2021

- 2.The News International. Child sexual abuse cases per day shot up in first half of 2020 in Pakistan: report. News Int.; 2020

- 3.Mehnaz A. Child abuse in Pakistan-current perspective. Natl J Health Sci. 2018;3:114–117. doi: 10.21089/njhs.34.0114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Granich S, Jabeen T, Omer S, Arshad M. Addressing the issue of child sexual abuse in Pakistan: a conceptual analysis. Int Soc Work 2021;00208728211031955

- 5.Gannon K, Ahmed M. Aid group reports surging numbers in child abuse in Pakistan|AP News. In: Assoc. Press. 2022. https://apnews.com/article/covid-health-pakistan-child-abuse-islamabad-f5a3c5b67ee0bbc37c4918bd3a89c105.

- 6.Shakil F. Child rape soars behind Covid-closed doors in Pakistan. In: Asia Times. 2020. https://asiatimes.com/2020/10/child-rape-soars-behind-covid-closed-doors-in-pakistan/.

- 7.Shafiq F, Bhamani S, Rahim KA, Gujrati M, Raza A, Sheikh L. Child wellbeing during COVID-19: a cross-sectional study from Pakistan. Pak J Med Dent. 2022 doi: 10.36283/pjmd11-2/013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Townsend C, Rheingold AA. Estimating a child sexual abuse prevalence rate for practitioners: a review of child sex abuse prevalence studies; 2013

- 9.Murray LK, Nguyen A, Cohen JA. Child sexual abuse. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2014;23:321–337. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honnavalli V, Neo LS, Gan R, Tee SH, Khader M, Chin J. Understanding violent extremism and child abuse: a psychological analysis. Child Abus Negl Forensic Issues Evid Impact Manag. 2019 doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-815344-4.00005-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lasser J, Adams K. The effects of war on children: School psychologists’ role and function. Sch Psychol Int. 2007;28:5–10. doi: 10.1177/0143034307075669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ali MI. Protection of children from sexual abuse in early years education in Pakistan: challenges and issues. J Early Child Care Educ. 2018;2:113–134. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beheshti M, Taspolat A, Kaya OS, Sapanca HF. Characteristics of instructional videos. World J Educ Technol Curr Issues. 2018;10:61–69. doi: 10.18844/wjet.v10i1.3186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eker C, Karadeniz O. The effects of educational practice with cartoons on learning outcomes. Int J Humanit Soc Sci. 2014;4:223–234. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shreesha M, Tyagi SK. Does animation facilitate better learning in primary education? A comparative study of three different subjects. Creat Educ. 2016;07:1800–1809. doi: 10.4236/ce.2016.713183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahrani T, Soltani R. The pedagogical values of cartoons. Res Humanit Soc Sci. 2011;1:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willmot P, Bramhall M, Radley K. Using digital video reporting to inspire and engage students. High Educ Acad 2012; 1–7

- 18.Habib K, Soliman T. Cartoons’ effect in changing children mental response and behavior. Open J Soc Sci. 2015;3:248. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Othman A, Yahaya WWAJ (2015) Application of Persuasive Multimedia to Raise Children’s Awareness of Child Abuse Among Primary School Students. In: 2nd Int. Conf. Educ. Soc. Sci. pp 355–361

- 20.Krahé B, Knappert L. A group-randomized evaluation of a theatre-based sexual abuse prevention programme for primary school children in Germany. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2009;19:321–329. doi: 10.1002/casp.1009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brame CJ. Effective educational videos: principles and guidelines for maximizing student learning from video content. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016;15:es6.1–es6.6. doi: 10.1187/cbe.16-03-0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tutty LM. Children’s Knowledge of Abuse Questionnaires (CKAQ)-short: two brief ten-item measures of knowledge about child sexual abuse concepts. J Child Sex Abus. 2020;29:513–530. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2019.1688443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali Hyder A, Aman Malik F. Violence against children: a challenge for public health in Pakistan. J Heal Popul Nutr. 2007;25:168–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avais MA, Narijo H, Parker M. A review of child sexual abuse in Pakistan based on data from “Sahil” organization. J Islam Med Dent Coll. 2020;9:212–218. doi: 10.35787/jimdc.v9i3.412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nizami AT, Hassan TM, Yasir S, Rana MH, Minhas FA. Terrorism in Pakistan: the psychosocial context and why it matters. BJPsych Int. 2018;15:20–22. doi: 10.1192/bji.2017.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orakzai SB. Pakistan’s approach to countering violent extremism (CVE): reframing the policy framework for peacebuilding and development strategies. Stud Confl Terror. 2019;42:755–770. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2017.1415786. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mian AI. 3.2 terrorism in Pakistan and its impact on children’s mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55:S5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.07.450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah SAA, Yezhuang T, Shah AM, Durrani DK, Shah SJ. Fear of terror and psychological well-being: the moderating role of emotional intelligence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 doi: 10.3390/ijerph15112554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davies L. Learning for state-building: capacity development, education and fragility. Comp Educ. 2011;47:157–180. doi: 10.1080/03050068.2011.554085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sebba J, Robinson C. Evaluation of UNICEF UK’s rights respecting schools award (RRSA). Citeseer; 2010

- 31.Siddiqui N, Gorard S, See BH. Non-cognitive impacts of philosophy for children. Durham: School of Education, Durham University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor E, Taylor PC, Karnovsky S, Aly A, Taylor N. “Beyond Bali”: a transformative education approach for developing community resilience to violent extremism. Asia Pac J Educ. 2017;37:193–204. doi: 10.1080/02188791.2016.1240661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theriault J, Krause P, Young L. Know thy enemy: education about terrorism improves social attitudes toward terrorists. J Educ Psychol Gen. 2017;146:305. doi: 10.1037/xge0000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aly A, Taylor E, Karnovsky S. Moral disengagement and building resilience to violent extremism: an education intervention. Stud Confl Terror. 2014;37:369–385. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2014.879379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stephens W, Sieckelinck S, Boutellier H. Preventing violent extremism: a review of the literature. Stud Confl Terror. 2021;44:346–361. doi: 10.1080/1057610X.2018.1543144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sas M, Ponnet K, Reniers G, Hardyns W. The role of education in the prevention of radicalization and violent extremism in developing countries. Sustain. 2020 doi: 10.3390/su12062320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shah SJ, Shah SAA, Ullah R, Shah AM. Deviance due to fear of victimization: “emotional intelligence” a game-changer. Int J Confl Manag. 2020;31:687–707. doi: 10.1108/IJCMA-05-2019-0081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeidner M, Matthews G. Grace under pressure in educational contexts: emotional intelligence, stress, and coping. In: Emot. Intell. Educ. New York: Springer; 2018. p. 83–110

- 39.Porche DJ. Emotional intelligence: a violence strategy. Am J Mens Health. 2016;10:261. doi: 10.1177/1557988316647332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alonso-Alberca N, San-Juan C, Aldás J, Vozmediano L. Be water: direct and indirect relations between perceived emotional intelligence and subjective well-being. Aust J Psychol. 2015;67:47–54. doi: 10.1111/ajpy.12065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naeem Z, Savul S, Khattak UK, Janjua K. Impact of health education on knowledge on child sexual abuse among teachers in twin cities of Pakistan. Pak J Public Heal. 2018;8:176–180. doi: 10.32413/pjph.v8i4.213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cyr M, McDuff P, Wright J. Prevalence and predictors of dating violence among adolescent female victims of child sexual abuse. J Interpers Violence. 2006;21:1000–1017. doi: 10.1177/0886260506290201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noll JG. Sexual abuse of children-unique in its effects on development? Child Abus Negl. 2008;32:603–605. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rudolph J, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Reviewing the focus: a summary and critique of child-focused sexual abuse prevention. Trauma Violence Abus. 2018;19:543–554. doi: 10.1177/1524838016675478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Othman A, Yahaya WAJW. A preliminary investigation: children’s awareness of child sexual abuse in Malaysia. Int J Soc Sci Humanit. 2013;2:242–247. doi: 10.7763/IJSSH.2012.V2.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

We are very open and assure that we will provide any original data sheets if required. That the data was authentic and collected and analysed through highest research standards. All the other authors contributed towards, data collection or literature review etc. We hope that this research-based video literacy program can be adopted widely to create awareness and understand predatory behaviours and know safety tips for school children.