Abstract

Riboswitches are a class of RNA motifs in the untranslated regions of bacterial messenger RNAs (mRNAs) that can adopt different conformations to regulate gene expression. The binding of specific small molecule or ion ligands, or other RNAs, influences the conformation the riboswitch adopts. Single Molecule Kinetic Analysis of RNA Transient Structure (SiM-KARTS) offers an approach for probing this structural isomerization, or conformational switching, at the level of single mRNA molecules. SiM-KARTS utilizes fluorescently labeled, short, sequence-complementary DNA or RNA oligonucleotide probes that transiently access a specific RNA conformation over another. Binding and dissociation to a surface-immobilized target RNA of arbitrary length are monitored by Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence Microscopy (TIRFM) and quantitatively analyzed, via spike train and burst detection, to elucidate the rate constants of isomerization, revealing mechanistic insights into riboswitching.

Keywords: Bacterial gene regulation, conformational dynamics, riboswitch, RNA folding, single molecule fluorescence microscopy

1. Introduction

RNAs are dynamic biomolecules that not only encode genetic information but also modulate many biological processes. RNA molecules are able to interconvert dynamically between complex structures with a range of functionalities (e.g., catalysis, gene regulation), making them an important class of biomolecules to study for understanding biology (Al-Hashimi & Walter, 2008; Cech & Steitz, 2014; Strobel, Yu, & Lucks, 2018).

Riboswitches, regulatory RNA elements found in the 5’ untranslated region (5’UTR) of some prokaryotic messenger RNAs (mRNAs), adopt different structural ensembles as a function of cellular conditions. These conformations can either promote or inhibit the expression of the gene(s) in the coding region of the hosting mRNA (i.e., acting in “cis”). Small molecule ligands preferentially bind to one conformation (via a highly specific aptamer domain), thereby stabilizing it. This feature allows for the concentration of the ligand to act as a rheostat that dynamically enhances the presence of a specific RNA conformation, in turn modulating gene expression (Garst, Edwards, & Batey, 2011). This dynamic structure-function relationship helps shape prokaryotic gene expression profiles (Sherwood & Henkin, 2016).

Single molecule approaches can detect and quantify individual biomolecular events. A subset of these techniques are suitable to probe the dynamic nature of riboswitch structure from which its modulation of protein expression can be inferred (Blanco & Walter, 2010; Ray, Chauvier, & Walter, 2019; Ray, Widom, & Walter, 2018; Schmidt, Gao, Little, Jalihal, & Walter, 2020; Uhm & Hohng, 2020).

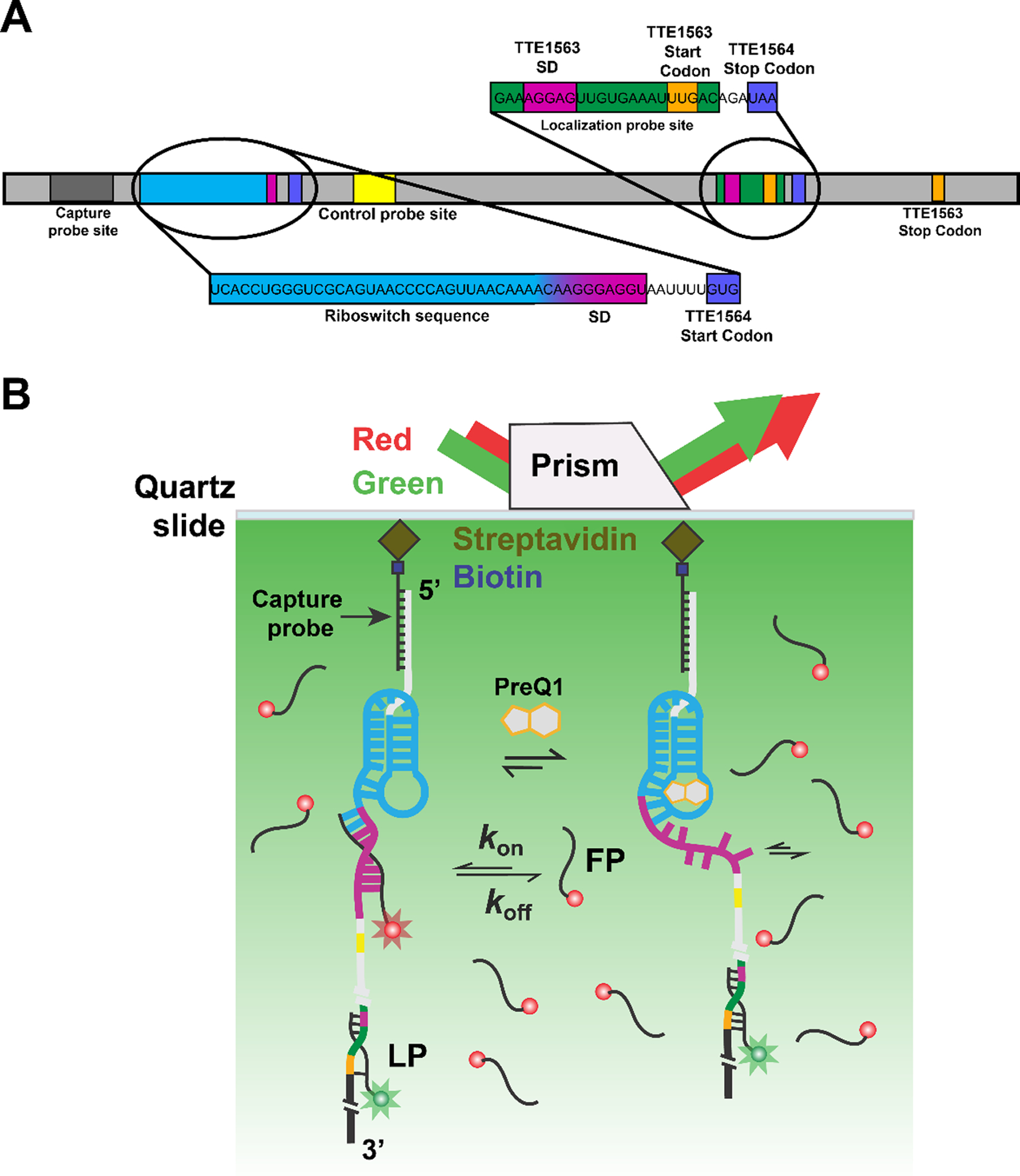

This chapter provides a protocol (focusing on probe design, reconstitution, immobilization, data acquisition and analysis) for SiM-KARTS (Single Molecule Kinetic Analysis of RNA Transient Structure), whereby riboswitch dynamics are probed, in real-time, without the limitations associated with direct labeling of target RNA (Figure 1) (Chauvier, Cabello-Villegas, & Walter, 2019; Rinaldi, Lund, Blanco, & Walter, 2016). In brief, by hybridizing a biotinylated nucleic acid capture probe (CP) and a fluorescently labeled nucleic acid localization probe (LP) to distal ends of the riboswitch hosting mRNA of interest, surface immobilization and localization are enabled, respectively (Figure 1). Next, a transiently binding, fluorescently labeled nucleic acid, the fluorescence probe (FP), is added in excess. It is designed to preferentially bind to one of the riboswitch conformations, whereas it is occluded from any other (Figure 1B). The transient binding and dissociation of the FP is recorded by Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence Microscopy (TIRFM) (Chauvier et al., 2019). The repeated binding events are recorded as spike trains in the fluorescence intensity originating from an individual riboswitch on the surface as a function of time (Figs. 2, 3). To discriminate between LP and FP, the probes are labeled with two different fluorophores that have easily distinguishable spectroscopic properties, typically emission wavelength (Figure 1B) (Chauvier et al., 2019). This strategy permits the extraction of distinct kinetic patterns, or temporal fingerprints, of the binding of FP to a specific region of target RNA that can be used to discriminate between, and measure the interconversion of, multiple conformations of an embedded riboswitch. SiM-KARTS can be applied under potentially many buffer and biological matrix conditions across a wide range of timescales (Chauvier et al., 2019; Ray et al., 2019; Rinaldi et al., 2016; Suddala et al., 2019).

Fig. 1.

SiM-KARTS measurements of an mRNA with embedded preQ1 riboswitch. (A) The preQ1 riboswitch containing mRNA. The transcript is immobilized onto the microscope slide after hybridization of the biotinylated capture probe (CP) to the corresponding recognition site on the target. The distally hybridized localization probe (LP) allows for the localization of single immobilized mRNA molecules. Transiently binding fluorescence probe (FP, here against the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence of the TTE1564 protein) senses structural changes of the riboswitch. (B) Experimental schematic of the SiM-KARTS assay using a prism-based TIRFM setup. After the RNA complex is immobilized onto a microscope slide via streptavidin and biotinylated BSA (biotin-BSA, not shown for simplicity), it is illuminated with a 532 nm wavelength laser (exciting the LP) to identify the RNA complex. A red laser (638 nm) is used to excite the FP, whose repeated binding to the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence results in spikes of fluorescence. In the presence of preQ1, the accessibility of the binding site of the FP changes.

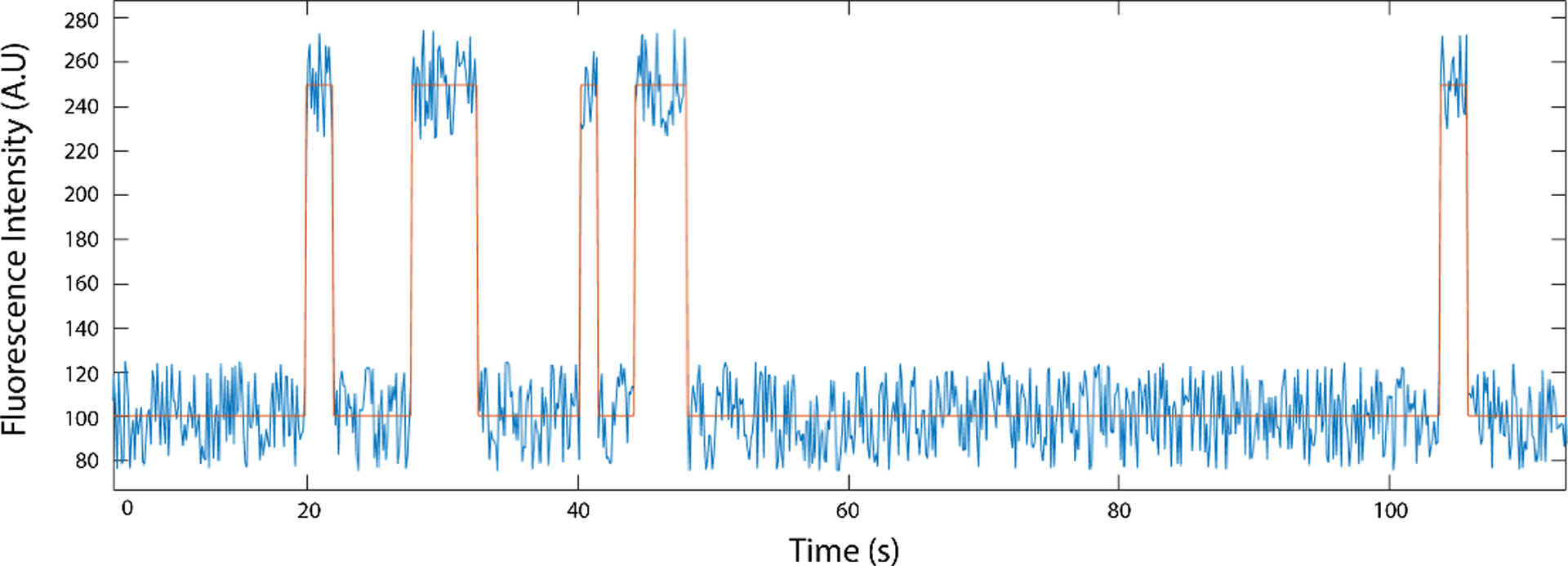

Fig. 2.

Example single molecule fluorescence trace (blue), idealized here by intensity thresholding (orange).

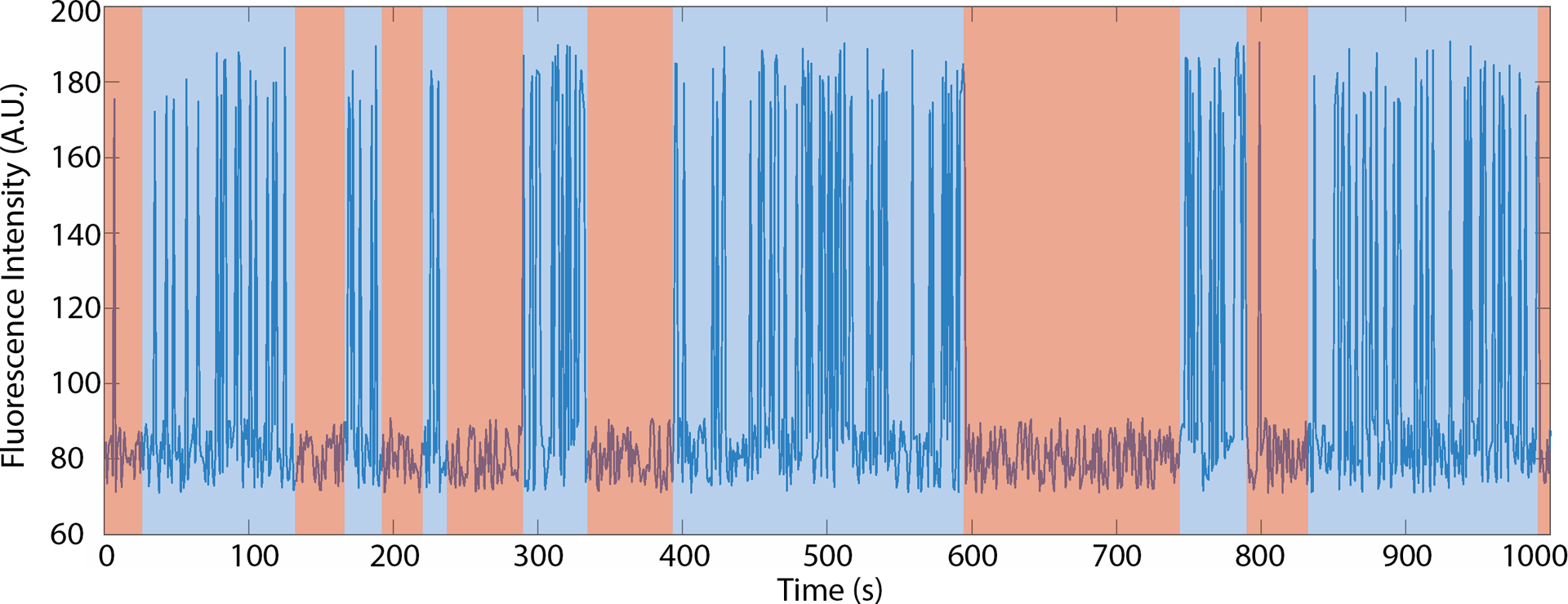

Fig. 3.

Extraction of burst behavior of a labeled SiM-KARTS probe binding and dissociating via spike train analysis. The blue line represents simulated data. Boxes indicate the time the RNA is in a conformation where the binding site is readily accessible (blue; burst) or inaccessible (pink; non-burst).

The current protocol is based on an investigation of a 7-aminomethyl-7-deazaguanine (preQ1)-sensing riboswitch (Rinaldi et al., 2016). The preQ1 riboswitch from Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis (Tte) regulates gene expression by forming a pseudoknot that partially masks its Shine-Dalgarno, or SD, sequence (Eichhorn, Kang, & Feigon, 2014; Suddala et al., 2013). In the absence of preQ1, the SD sequence is more readily available to hybridize to the anti-SD sequence of 16S ribosomal RNA, resulting in the translation of two downstream proteins, TTE_RS07450 and TTE_RS07445, involved in cellular preQ1 metabolism (Rinaldi et al., 2016).

SiM-KARTS interrogates the conformational changes of a target system via binding and dissociation of an FP. It can, in principle, probe any nucleic acid that isomerizes between different secondary structures so long as: i) there is a portion of the target that alternates between being single- and double-stranded forms that can accommodate binding a short (typically <10 nucleotide complementarity) nucleic acid labeled with a fluorescent dye; ii) the binding events are long enough to be resolved by single molecule TIRFM (typically ~100 ms or longer desired); and iii) the probe generates a distinct, site-specific kinetic fingerprint of binding and dissociation events that depends on the RNA conformation. Of note, targeting a conformational change provides an intrinsic control for any perturbation the FP may have on the structure probed since only the relative (ratiometric) change is evaluated as a readout of the underlying conformational equilibrium.

2. Materials

The materials presented here describe the representative experiments in (Rinaldi et al., 2016). To generalize this materials section, the reader will want to replace the ligand, imaging buffer, mRNA transcript, and probes to pertain to the specific riboswitch or RNA under study. All solutions should be prepared in doubly deionized water (ddH2O), obtained by further purifying deionized water to a resistivity of 18 MΩ cm, and using the highest purity of reagents available.

2.1. Ligand 7-aminomethyl-7-deazaguanine (preQ1)

PreQ1 can be synthesized according to (Akimoto, Imamiya, Hitaka, Nomura, & Nishimura, 1988) or simply purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Cat. Number: SML0807). Care needs to be taken to dissolve the preQ1 into a high stock concentration (1 mM) since it is multi-protic so that the pH needs to be adjusted to neutrality.

2.2. Riboswitch containing mRNA transcript

The mRNA transcript containing the 5’UTR riboswitch is typically generated by in vitro transcription (Rinaldi et al., 2016; Rinaldi, Suddala, & Walter, 2015).

2.3. Biotinylated bovine serum albumin (1 mg/ml)

Biotin-BSA can be purchased from diverse commercial sources, such as Sigma Aldrich (CAS Number 9048–46-8).

2.4. T50 buffer

10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl.

2.5. Oxygen scavenging stock solution with TROLOX (OSST)

Each component is stored individually and combined immediately prior to usage; the mixture can be stored for up to 2 hours:

Protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase (PCD), 1 μM in 100 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 50% (v/v) glycerol. Stored at −20 °C. PCD is obtainable from Sigma Aldrich, CAS number 9029–47-4.

Protocatechuic acid (PCA), 100 mM dissolved in ddH2O, adjusted with 5 M KOH to pH 8.3. Stored at −20 °C. PCA is obtainable from Sigma Aldrich, CAS number 99–50-3.

TROLOX, 100 mM dissolved in ddH2O, adjusted with 5 M KOH to ~pH 10, filtered with 0.2 μm filter and stored at −20 °C. (See Note 1.) TROLOX is obtainable from Fisher Scientific, CAS number 53188–071.

2.5. 2x reconstitution buffer

100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 at 25 °C, 1200 mM NaCl and 40 mM MgCl2.

2.6. Imaging buffer

1x reconstitution buffer supplemented with OSST (5 mM PCA, 50 nM PCD and 2 mM TROLOX).

2.7. Preparation of slides with microfluidic channel

Protocols for preparation of a microfluidic channel on a slide can be found in (Chauvier et al., 2019; Uhm & Hohng, 2020). In brief, a quartz slide (G. Finkenbeiner, 1” × 3” × 1mm microscope slides) has two 1 mm holes drilled in it approximately one inch apart. The flow channel is then created by placing double-sided adhesive tape (3M catalogue no. 3136) to form a thin channel that starts and ends at the holes. A microscope coverslip is attached to the adhesive tape, completing the flow channel. During the SIM-KARTS experiment, fluids can be passed through the channel by tubing fixed to the holes (typically with epoxy) or via wicking action.

2.8. Oligonucleotides

Oligonucleotide probes are obtainable from, e.g., Integrated DNA Technologies. TYE563 can be substituted with Cy3. For a detailed description of probe design, see Notes 2–6. In the following, the probes are written in 5’ to 3’ direction.

Capture probe (CP):

GCCTCTTAGCAACTTGTAGTAGGAGTTCCAAAAAAAAAA-biotin, which acts as an immobilization anchor of the RNA transcript onto the microscope slide.

Localization probe (LP):

TYE563-+GT+CAAATTT+CA+CAA+CT+C+CTTT+C, where a preceding “+” indicates a locked nucleic acid (LNA) nucleotide, which increases the hybridization stability; the LP serves to identify single target RNA molecules.

Fluorescent probe (FP):

Cy5-GAUCACCUCCUU, which serves as anti-SD probe to read out conformational changes of the riboswitch containing mRNA.

Control probe:

Cy5-GCAACAAGAGC; acts as an internal control for specific structural changes of preQ1 riboswitch containing mRNA due to preQ1; ligand addition should not affect its binding behavior, in contrast to the FP’s behavior.

2.9. Microscope and Hardware

A microscope capable of objective, or prism, TIRFM is needed. For details on model instruments please see recent reviews (Gibbs, Kaur, Megalathan, Sapkota, & Dhakal, 2018; Roy, Hohng, & Ha, 2008). In short, our setup consists of two lasers, a Venti 532 (Laser Quantum) and an Obis 637 (Coherent), to excite the LP and FP, respectively, power of laser beams range between 50 and 100 mW over an area of typically 1.76 mm2. Sample is loaded into a custom quartz microfluidic flow cell (Roy et al., 2008), which is mounted on an inverted fluorescence microscope (IX71 Olympus). The fluorescence emission from the LP and FP are split with a dichroic mirror and laser scatter is removed via bandpass filters. Fluorescence is recorded with a sCMOS (scientific complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor) camera (ORCA 3, Hamamatsu).

2.10. Software

Analysis of single molecule movies requires software for creating single molecule data traces. Multiple such programs are available for download (e.g., SPARTAN (Juette et al., 2016)), MASHFRET (Hadzic, Kowerko, Börner, Zelger-Paulus, & Sigel, 2016); we use homebuilt scripts. The only requisite is that the fluorescence data can be exported in a comma separated values (CSV) format for processing with our SiM-KARTS pipeline. The SiM-KARTS burst detection algorithm (https://github.com/RobbWelty/SiMKARTS) requires MATLAB (version 6.5 or later with the statistical toolbox). However, the process is generalizable and can be rewritten into a different language if desired.

3. Methods

3.1. Preparation of RNA complex for SiM-KARTS

Denature riboswitch containing mRNA transcript, LP and CP (2 nM each) at 70 °C in the presence of 1x reconstitution buffer for typically 2 min.

Allow the reaction to cool to room temperature (~21 °C) over 20 min in the presence (≥10 μM for saturation in the case of preQ1) or absence of ligand.

Dilute the reaction mixture to 40 pM in >200 μL using the same buffer in the presence or absence of ligand and supplemented with a 12.5-fold excess of both LP and CP to ensure the complex stays intact upon dilution. The complex can be chilled on ice. (See note 7.)

3.2. Immobilization of reconstituted preQ1 riboswitch containing mRNA complex onto microscope slides

All binding and washing steps are typically performed at room temperature.

Flow 200 μL of biotin-BSA (1 mg/ml) through the microfluidic channel and allow to bind for 10 min. (This step passivates the glass surface as well as introduces anchoring moieties for the mRNA complex.)

Wash unbound biotin-BSA with 200 μL of T50 buffer.

Flow through 0.2 mg/mL streptavidin and wait for 5 min to ensure saturation.

Flow through 200 μL of 1x reconstitution buffer to wash away unbound excess streptavidin.

Flow through 200 μL diluted and reconstituted riboswitch transcript complex and wait for 5 min to ensure saturation.

Flow through 200 μL of 1x reconstitution buffer to wash away unbound riboswitch transcript complex.

Flow through 200 μL of FP (50 nM) in imaging buffer, wait 5 min for equilibration.

Start imaging.

3.3. Data acquisition

Start image acquisition with both lasers that illuminate both the CP and LP. See notes section for recommendations on hardware settings.

(Optional) Turn off the laser illuminating the LP after some number (e.g., 100) frames, to reduce background from scattered laser illumination.

After acquisition, move the microscope slide to a new field of view and record another movie.

Repeat step 4 until you have produced the desired number of movies (typically 5 to 10 movies are sufficient to generate at least 200 single molecule traces, but this will depend heavily on the biochemical and microscope system used).

3.4. Data Analysis

After the movies have been taken, the fluorescence intensities of the FPs must be extracted for the time course of the movie (see note 8). There are many programs available for this purpose, including SPARTAN (Juette et al., 2016), MASH FRET (Hadzic et al., 2016), and multiple proprietary homebuilt scripts. To complete SiM-KARTS analysis, using the tools provided in this chapter, the only requisite is that the fluorescence intensity for single molecules over the time of the movie, called traces, must be in a CSV format with the columns corresponding to individual LP positions and the rows corresponding to the time the intensity was collected. To increase the accuracy of spot selection, we recommend mapping the coordinates of the LP and FP movies. This is typically accomplished by taking an image of fluorescent beads, such as Invitrogen’s FlouSpheres (catalogue no. F8803) that emit fluorescence that is detectable in both the LP and CP channels, and then determining the coordinates of the detected spots, in both channels, through a spatial mapping algorithm. This allows for the matching of individual spots that have both an LP and FP binding. This functionality comes standard in the aforementioned trace creation software packages.

3.5. Trace Idealization

Once the fluorescence trajectories from each single molecule position have been generated, they will need to be idealized. Trace idealization is the process where the raw trace data is converted into a binary signal that identifies when the signal is higher than the background, which corresponds to the FP being bound (Figure 2). There are many ways of doing this, please see note 9.

3.6. Calculating the Fano Factor

A first-pass analysis approach, to determine if the signal indicates changes in the underlying conformation of the riboswitch, is with a Fano factor analysis (Fano, 1947). Whereby the Fano factor, a statistical construct defined as the variance divided by the mean, of the spikes (FP binding events) is calculated. The behavior of FPs binding a riboswitch, in a single conformation, is accurately modeled with a Poisson distribution (Rinaldi et al., 2016), and the Fano factor of such a Poisson process is 1 (i.e., the variance and mean are equivalent) (Eden & Kramer, 2010). However, if the riboswitch alternates between two conformations that have distinct FP binding kinetics, the signal will not be Poissonian. By calculating the Fano factor, dividing the variance of spike counts by the mean spike count for a given time interval, we can determine if the binding is a simple Poisson process or not. As long as the timescale of riboswitch isomerization is shorter than the entire SiM-KARTS movie taken, then the calculated Fano factor will deviate from 1. It is good practice to calculate Fano Factors for various time windows, which gives a quick indication of the timescale of riboswitch isomerization.

3.7. Calculate the Burst and Dwell Times

If the Fano factor analysis indicates more than one riboswitch conformation, then further analysis is warranted to extract burst and non-burst segments of each trace, as described in the following.

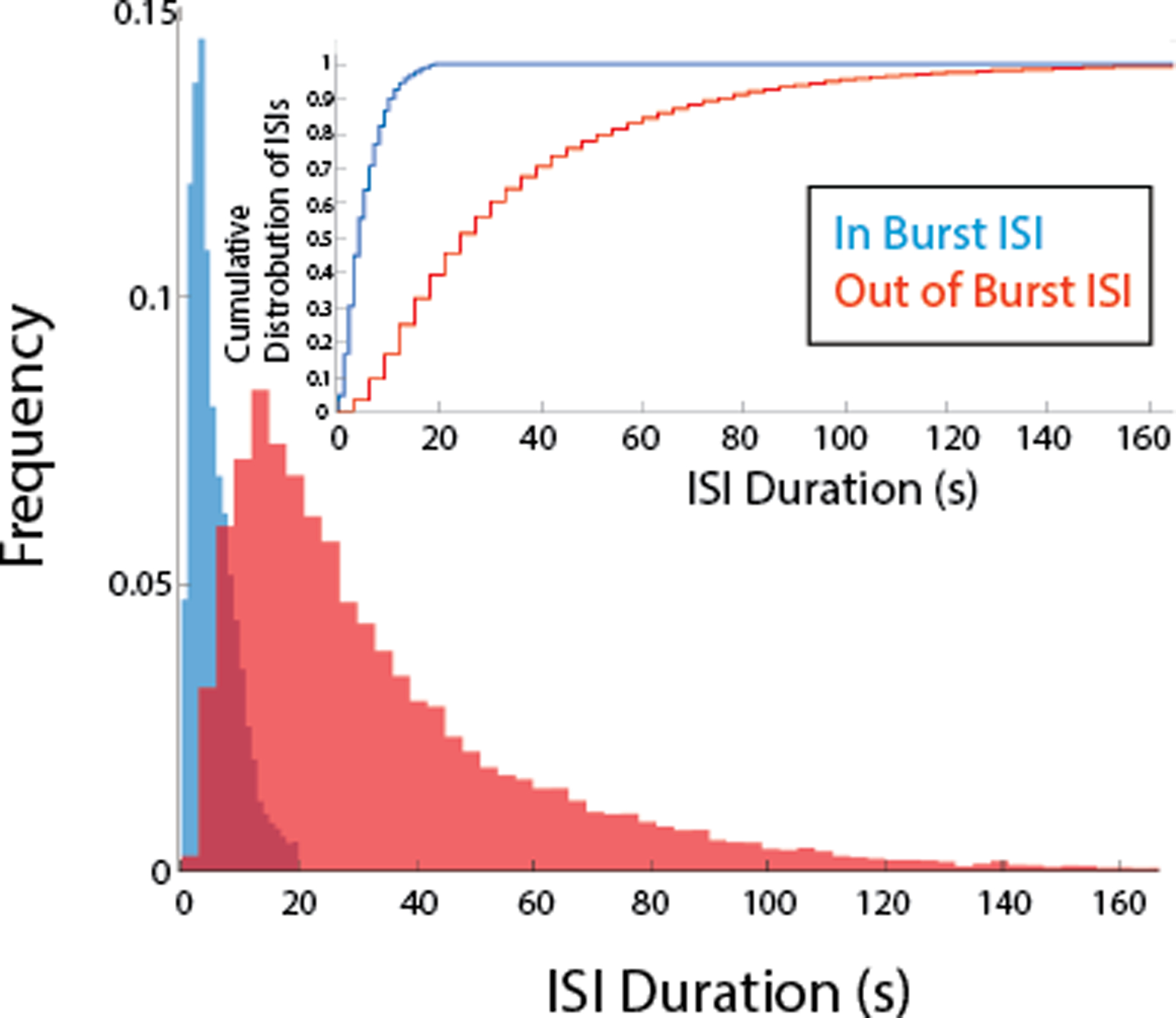

Feed the idealization of all traces into the burst detection script (https://github.com/RobbWelty/SiMKARTS). The script will produce the burst length time, the dwell time of interval between spikes (inter-spike interval, or ISI) during and outside of the bursts (i.e., in the non-burst segments).

Construct cumulative density plots with the output from the burst detection algorithm.

Fit the burst time cumulative distribution function with a single-exponential equation to get the isomerization rate of the riboswitch from SD accessible to inaccessible conformations.

Fit the “in burst” dwell times with a single-exponential function to obtain the binding rate constant of the LP to the more SD accessible conformation.

Fit the “Out of burst”, or non-burst, dwell times with a single-exponential function to obtain the binding rate constant of the FP to the more SD inaccessible conformation.

5. Conclusions

SiM-KARTS represents a powerful method for quantifying RNA structural dynamics on the single-molecule level. By monitoring the binding and dissociation of fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes designed to target a specific section(s) of the RNA sequence, the relative populations and the kinetics of isomerization can be inferred via spike train burst analysis.

This technique was primary designed to interrogate a site-specific structural element of an RNA. Here, we have described an exemplary protocol for the investigation of a preQ1-sensing riboswitch, but SiM-KARTS can be applied to probe any length and type of RNA in its native state, including those directly isolated from a physiological source (e.g., cellular extracts or biofluids) without the need for labeling, which is a significant source of challenge for other single molecule techniques. Due to the rapid exchange of FPs, the observation window can be significantly longer than direct labeling techniques that suffer from slow photobleaching, making it possible to interrogate RNA molecules on the tens-of-minutes timescale. Moreover, SiM-KARTS has the potential to read out secondary as well as tertiary structural dynamics in real-time and is mostly limited by the photon emission rates needed to generate a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio at a desired detection speed. In the future, labeling the FP with multiple fluorophores can be used to improve signal-to-noise; and, in principle, any fluorophore labeled entity (such as a 30S ribosomal subunit) can be used for probing structural change within a biological context of interest (Chatterjee, Chauvier, Dandpat, Artsimovitch, & Walter, 2021). In general, the conceptual design of SiM-KARTS can be adapted to many types of biomolecular interactions in which equilibrium or non-equilibrium processes need to be monitored including not only riboswitches but also, e.g., RNA thermosensors.

6. Notes

Materials

-

1

The OSST composition should take into consideration the specific properties of the biochemical system being targeted. The PCA/PCD system has been observed to affect the rates of enzymes that use NTPs as cofactors (Widom et al., 2018). Alternatively, 44 mM glucose, 165 U/mL glucose oxidase form Aspergillus niger, in conjunction with 2,170 U/mL catalase from Corynebacterium glutamicum, can be used for scavenging oxygen (Aitken, Marshall, & Puglisi, 2008).

Capture probe (CP) and localization probe (LP)

-

2

To achieve specific immobilization of the target RNA to the microscope slide, the CP (usually DNA, sometimes containing LNA residues for stabilization) should be terminally labeled with biotin. Alternatively, the target RNA can be directly functionalized with biotin, which removes the need for a CP. While direct labeling may seem more efficient, the advantage to using a CP is two-fold. First, the same CP potentially can be used with multiple RNA systems. Second, as the RNA of interest is typically the limiting reagent, the labeling efficiency can severely reduce the yield of labeled RNA and introduce additional cumbersome steps that may modify the RNA fold in unexpected ways.

-

3

LP design is similar to CP but labeled with a fluorophore (usually a Cy3 or equivalent) instead of biotin. Alternatively, instead of using separate CP and LP, a single oligonucleotide can be synthesized bearing both modifications (biotin and fluorophore), allowing it to act as both CP and LP. However, in this case, many more Cy3 labeled spots may be observed that are not associated with an RNA, and no readout of the integrity of a bound RNA is obtained.

-

4

The key to successful CP and LP design is to ensure that they are bound stably to the RNA transcript throughout the entire experiment. While there are tools for predicting hybridization energies (Markham & Zuker, 2005) a simple method is to use the web-based melting prediction software provided by commercial synthetic oligonucleotide providers (such as Oligoanalyzer from Integrated DNA Technologies Inc. IDT; or tools from Qiagen). The probes should have a high predicted melting temperature (Tm) of >60 °C (as a proxy for a binding equilibrium constant) and a very low self-structure score (below the experimental temperature). To assure the full integrity of immobilized target RNA, CP and LP should be designed to bind different sections of the RNA sequence, ideally at opposite ends of the target RNA. Modified and HPLC purified CP and LP can be purchased from commercial suppliers.

-

5

It is important to verify that the probes do not perturb the folding of the target RNA into its natural secondary structure. If one cannot successfully find sections of the natural RNA sequence to attach probes without perturbing the conformation of interest, one solution is to append arbitrary hybridization sequences to the 5’ and/or 3’ ends of target RNA, which can hybridize to either CP and LP or both. The sequence of the appended regions can be designed by computational folding predictions (such as Mfold (Zuker, 2003) or RNA Structure (Reuter & Mathews, 2010)) to avoid interfering with the native fold of the target RNA transcript. The functionality of the target RNA should be checked after hybridization. Efficient hybridization can be verified by non-denaturing gel electrophoresis (Bak, Han, Kim, & Lee, 2015), and the folded secondary structure can be determined via footprinting (Wilkinson, Merino, & Weeks, 2006).

Fluorescent probe (FP)

-

6

First, the FP should have binding and dissociation rates that are (at least) an order of magnitude faster than the isomerization rate of the RNA transcript. Second, SiM-KARTS relies on the rate of the FP binding to the RNA transcript to differ depending on the conformation of the RNA. To optimize for fast FP binding and dissociation, the FP sequence ought to be designed to have a melting temperature close to the experimental temperature. The mean bound time of the FP is ideally 2–5 times longer than the integration time (usually 50–300 ms) of the camera. This helps the trace idealization process and prevents interpreting a single “hot” frame, an artifact caused by electrical fluctuations in the camera, as a binding event. The binding/dissociation rate constants can be empirically optimized by varying the length and GC content of the FP. The dissociation rate constant of a short DNA oligonucleotide, under standard temperature and salt conditions, is exponentially dependent on length. The optimal length of the FP probe with a 50% GC content is between 7 and 8 nucleotides. Modulation of association/dissociation rate constant can be achieved by adjusting the salt concentration (higher monovalent salt concentrations promote binding).

-

7

To ensure that the FP is binding to the desired nucleotides of the mRNA sequence, is it beneficial to use a site-blocking oligonucleotide as a further control. This is an RNA or DNA complementary to the FP binding site as well as regions upstream and downstream. If the mRNA is incubated with the site-blocker and prepared for a SiM-KARTS experiment, the FP should be unable to bind the desired binding site. If FP binding events are still observed in the presence of the site-blocking oligonucleotide, it is an indication that the FP is binding also to another part of the mRNA sequence and the design of the FP needs to be re-evaluated.

Reconstitution of target system

-

8

The reconstitution strategy will depend on the target system. Systematic optimization (of, e.g., the annealing temperature, probe concentration) is necessary to achieve a high reconstitution efficiency. A good starting point is to take the RNA transcript and heat it to 90 °C, include either the CP or LP (as long as they will not bind to an off-target part of the RNA sequence) for 5 min. Let the RNA cool on the bench top or on ice. It may be helpful to keep the RNA and probes at a high (micromolar) concentration during heating/cooling to maximize hybridization. If this is successful, follow an 8:4:1 annealing strategy where the LP is eight-fold, and the RNA is four-fold, higher in concentration than the CP, which maximizes the probability that the surface immobilized RNA will have both the LP and CP bound. If there is a possibility that the LP or CP will bind to off-target sections of the RNA sequence, then add them after the RNA has cooled.

Data Acquisition Settings

-

9

Finding the right balance of hardware settings for single molecule experiments can be a challenge, and SiM-KARTS experiments are no exception. The relationship between laser power, probe bound time and camera exposure time needs to be carefully balanced. First the dwell times of the FP needs to be characterized. Once that time is known, the exposure time of the camera should be adjusted until the mean FP bound time is no less than 3–5 frames, but otherwise as short as possible. This increases temporal resolution while preventing single-frame noise spikes (hot frames) from being counted, which would reduce the accuracy of the data. The laser power should be as high as needed to easily differentiate from bound FP and the background, since higher laser intensities contribute to excess background in some microscope settings. The length of the movie will depend on the rate of FP binding. We recommend taking long (~9000) frame movies to increase the number of binding events observed.

Trace Idealization

-

10

The fluorescence signal from single molecule measurements has associated noise. There are many software packages, such as QuB (Qin & Li, 2004), vbFRET (Bronson, Fei, Hofman, Gonzalez, & Wiggins, 2009), and HAMMY (McKinney, Joo, & Ha, 2006), that help discern the true fluorescence intensity, a process known as idealization. While it is common for idealization to aim to discern fluorescence intensities for multiple chemical states, SiM-KARTS analysis only needs a binary signal corresponding to whether an LP is bound or not. The Burst analysis script provided at (https://github.com/RobbWelty/SiMKARTS) requires traces to be idealized, but will automatically reduce any multistate idealization to a binary trace.

Fig. 4.

Normalized histogram representing the distribution of ISIs during bursts (when the binding site is accessible; in blue) and non-burst (when the binding site is not readily accessible; in red). Inset: Cumulative histogram representation of the same data.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH grant GM131922 to N.G.W. and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) Project-ID 449562930 to A.S.

References

- Aitken CE, Marshall RA, & Puglisi JD (2008). An Oxygen Scavenging System for Improvement of Dye Stability in Single-Molecule Fluorescence Experiments. Biophysical Journal, 94(5), 1826–1835. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.117689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimoto H, Imamiya E, Hitaka T, Nomura H, & Nishimura S (1988). Synthesis of queuine, the base of naturally occurring hypermodified nucleoside (queuosine), and its analogues. Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 1(7), 1637–1644. doi: 10.1039/P19880001637 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hashimi HM, & Walter NG (2008). RNA dynamics: it is about time. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 18(3), 321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak G, Han K, Kim KS, & Lee Y (2015). Electrophoretic mobility shift assay of RNA-RNA complexes. Methods Mol Biol, 1240, 153–163. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1896-6_12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco M, & Walter NG (2010). Chapter 9 - Analysis of Complex Single-Molecule FRET Time Trajectories. In Walter NG (Ed.), Methods in Enzymology (Vol. 472, pp. 153–178): Academic Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronson JE, Fei J, Hofman JM, Gonzalez RL, & Wiggins CH (2009). Learning Rates and States from Biophysical Time Series: A Bayesian Approach to Model Selection and Single-Molecule FRET Data. Biophysical Journal, 97(12), 3196–3205. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.09.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cech TR, & Steitz JA (2014). The noncoding RNA revolution-trashing old rules to forge new ones. Cell, 157(1), 77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Chauvier A, Dandpat SS, Artsimovitch I, & Walter NG (2021). A translational riboswitch coordinates nascent transcription–translation coupling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(16), e2023426118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2023426118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvier A, Cabello-Villegas J, & Walter NG (2019). Probing RNA structure and interaction dynamics at the single molecule level. Methods, 162–163, 3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2019.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden UT, & Kramer MA (2010). Drawing inferences from Fano factor calculations. J Neurosci Methods, 190(1), 149–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorn CD, Kang M, & Feigon J (2014). Structure and function of preQ(1) riboswitches. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1839(10), 939–950. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fano U (1947). Ionization Yield of Radiations. II. The Fluctuations of the Number of Ions. Physical Review, 72(1), 26–29. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.72.26 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garst AD, Edwards AL, & Batey RT (2011). Riboswitches: structures and mechanisms. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 3(6), a003533. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs DR, Kaur A, Megalathan A, Sapkota K, & Dhakal S (2018). Build Your Own Microscope: Step-By-Step Guide for Building a Prism-Based TIRF Microscope. Methods and Protocols, 1(4), 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadzic MCA, Kowerko D, Börner R, Zelger-Paulus S, & Sigel RK (2016). Detailed analysis of complex single molecule FRET data with the software MASH (Vol. 9711): SPIE. [Google Scholar]

- Juette MF, Terry DS, Wasserman MR, Altman RB, Zhou Z, Zhao H, & Blanchard SC (2016). Single-molecule imaging of non-equilibrium molecular ensembles on the millisecond timescale. Nature methods, 13(4), 341–344. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham NR, & Zuker M (2005). DINAMelt web server for nucleic acid melting prediction. Nucleic Acids Res, 33(suppl_2), W577–W581. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney SA, Joo C, & Ha T (2006). Analysis of Single-Molecule FRET Trajectories Using Hidden Markov Modeling. Biophysical Journal, 91(5), 1941–1951. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.082487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F, & Li L (2004). Model-Based Fitting of Single-Channel Dwell-Time Distributions. Biophysical Journal, 87(3), 1657–1671. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.037531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S, Chauvier A, & Walter NG (2019). Kinetics coming into focus: single-molecule microscopy of riboswitch dynamics. RNA biology, 16(9), 1077–1085. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2018.1536594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S, Widom JR, & Walter NG (2018). Life under the Microscope: Single-Molecule Fluorescence Highlights the RNA World. Chemical Reviews, 118(8), 4120–4155. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter JS, & Mathews DH (2010). RNAstructure: software for RNA secondary structure prediction and analysis. BMC Bioinformatics, 11(1), 129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi AJ, Lund PE, Blanco MR, & Walter NG (2016). The Shine-Dalgarno sequence of riboswitch-regulated single mRNAs shows ligand-dependent accessibility bursts. Nature Communications, 7(1), 8976. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi AJ, Suddala KC, & Walter NG (2015). Native purification and labeling of RNA for single molecule fluorescence studies. Methods Mol Biol, 1240, 63–95. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1896-6_6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy R, Hohng S, & Ha T (2008). A practical guide to single-molecule FRET. Nature methods, 5(6), 507–516. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A, Gao G, Little SR, Jalihal AP, & Walter NG (2020). Following the messenger: Recent innovations in live cell single molecule fluorescence imaging. WIREs RNA, 11(4), e1587. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood AV, & Henkin TM (2016). Riboswitch-Mediated Gene Regulation: Novel RNA Architectures Dictate Gene Expression Responses. Annual Review of Microbiology, 70(1), 361–374. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel EJ, Yu AM, & Lucks JB (2018). High-throughput determination of RNA structures. Nature Reviews Genetics, 19(10), 615–634. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0034-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suddala KC, Price IR, Dandpat SS, Janeček M, Kührová P, Šponer J, … Walter NG (2019). Local-to-global signal transduction at the core of a Mn(2+) sensing riboswitch. Nat Commun, 10(1), 4304. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12230-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suddala KC, Rinaldi AJ, Feng J, Mustoe AM, Eichhorn CD, Liberman JA, … Walter NG (2013). Single transcriptional and translational preQ1 riboswitches adopt similar pre-folded ensembles that follow distinct folding pathways into the same ligand-bound structure. Nucleic Acids Res, 41(22), 10462–10475. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhm H, & Hohng S (2020). Single-Molecule FRET Assay for Studying Cotranscriptional RNA Folding. Methods Mol Biol, 2106, 271–282. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0231-7_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom JR, Nedialkov YA, Rai V, Hayes RL, Brooks CL 3rd, Artsimovitch I, & Walter NG (2018). Ligand Modulates Cross-Coupling between Riboswitch Folding and Transcriptional Pausing. Mol Cell, 72(3), 541–552.e546. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson KA, Merino EJ, & Weeks KM (2006). Selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension (SHAPE): quantitative RNA structure analysis at single nucleotide resolution. Nature Protocols, 1(3), 1610–1616. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M (2003). Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res, 31(13), 3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]