Abstract

Aims and objectives

To provide guidance to nurses by examining how critical care nurses perceive and perform the family support person role during resuscitation.

Background

Nurses can serve as family support person when families witness a loved one's resuscitation. However, few studies have examined the role of family support person to provide nurses with sufficient knowledge to enact the role.

Design

An exploratory‐descriptive qualitative design with individual, semi‐structured interviews.

Methods

Sixteen critical care nurses who had served as family support person completed interviews. The data were analysed by thematic analysis. COREQ guidelines were followed.

Results

Six themes were identified: Hard but Rewarding Role, Be With, Assess, First Moments, Explain and Support. Findings explicated nurses’ perceptions of the role and key role activities.

Conclusions

Nurses perceived the role as hard but rewarding. Role challenges included the need for quick, accurate assessments and interventions to keep family members safe, informed and supported, while allowing them to witness resuscitation. Key role activities included: being fully present and compassionately attentive to family, continuously assessing family members, coordinating the first moments when family presence during resuscitation commences, explaining in simple, tailored terms the resuscitation activities, and supporting the family emotionally and psychologically through a variety of strategies. Nurses noted the high variability in how families respond and the complexity of simultaneously performing the multi‐faceted role activities.

Relevance to clinical practice

To effectively support the growing global trend of family presence during resuscitation, nurses need the knowledge this study provides about how to fulfil the family support person role. Identifying the role activities may facilitate development of clinical guidelines and educational preparation for the role. Nurses can refine the many skills this role requires, building their competence and confidence, to increase opportunities for family members to experience family presence during resuscitation in a safe, and high‐quality manner.

Keywords: critical care nursing, family presence during resuscitation, family support person, family‐witnessed resuscitation

What does this add to the greater global community?

This study is the first to explicate the family support person role from the perspectives and experiences of critical care nurses.

Nurses are uniquely prepared, educationally and experientially, to fulfil this professional, clinical autonomous role.

Identifying role activities can lead to development of clinical guidelines and educational preparation to guide nurses to effectively support families during resuscitation.

1. INTRODUCTION

Family support persons play a pivotal role when family members are present during the resuscitation of a hospitalised loved one. Although controversy over family presence during resuscitation (FPDR) has swirled for decades, trends now reflect a growing recognition of the benefits of FPDR as an evidence‐based aspect of family‐centred care (Toronto & LaRocco, 2019). Professional organisations advocate for FPDR and call for a healthcare professional to fill the role of family support person (FSP) (American Association of Critical‐Care Nurses [AACN], 2016; Davidson et al., 2017). Nurses can fulfill the FSP role; however, few studies have examined this role, and no clinical guidelines exist for nurses who serve as FSP. As a result, nurses report feeling unprepared to support family members and may be reluctant to step into this role in the midst of a crisis. Without an FSP, families may not be invited into the resuscitation and may miss being with their loved one in the last moments of life (Powers, 2017). Research is needed to examine the nature of the FSP role, including nurses’ perceptions of the role and how they enact it. A deeper understanding of the FSP role can guide nurses in promoting positive family outcomes and improve the integration of FPDR into practice.

2. BACKGROUND

Family‐centred care is grounded in respect for family wishes, engagement of family in patient care and provision of information to aid decision‐making (Institute for Patient‐ and Family‐Centered Care, n.d.). Family‐centred care is especially important in critical care settings because it can help mitigate symptoms of post‐intensive care syndrome among family members (Davidson et al., 2017). A philosophical commitment to family‐centred care is exemplified when family are offered the option to be present at the bedside of a loved one during resuscitation.

Research indicates a majority of family members worldwide prefer FPDR (Tíscar‐González et al., 2021). A plethora of studies, ranging from qualitative studies to randomised controlled trials and meta‐analyses, demonstrate the benefits of FPDR. Benefits include mutual exchange of information between family and the team, opportunity for family to receive support during the resuscitation, and improved grief experience by sharing last moments with their loved one and witnessing resuscitation efforts (Toronto & LaRocco, 2019; Vardanjani et al., 2021). Despite the shown benefits of FPDR, the practice remains controversial among healthcare professionals who often cite disproven risks, such as the potential for family members to experience psychological trauma and interfere with patient care (Twibell et al., 2018). While staff resistance and other obstacles (i.e. staff shortages, lack of space in patient rooms) are known barriers to consistent implementation of FPDR (Kleinpell et al., 2018), the lack of healthcare personnel prepared to serve as FSP is a major barrier. In a study of critical care nurses across the United States, 74% of 380 respondents perceived an FSP as essential to effective FPDR. Although they expressed interest in being an FSP, nurse respondents asked for guidance so they could effectively support family members (Powers, 2017).

The AACN and Society for Critical Care Medicine advocate for FPDR with an FSP (AACN, 2016; Davidson et al., 2017). However, neither organisation offers specific direction for fulfilling the role. Only two studies have explored the FSP role, with samples of three chaplains and four nurses (James et al., 2011) and ten social workers (Firn et al., 2017). These studies suggest being an FSP requires specialised skills for assessing the family, providing information and supporting grief responses (Firn et al., 2017; James et al., 2011). Nurses may be well‐suited for the FSP role because of their assessment skills, resuscitation knowledge, holistic approach to care delivery and availability at the bedside. Though well‐suited for the role, evidence is lacking about how nurses can fill the scope and activities of the FSP role. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine how critical care nurses perceive and perform the FSP role during resuscitation.

3. METHODS

3.1. Study design and research questions

An exploratory‐descriptive qualitative design addressed two research questions: (1) How do critical care nurses perform the FSP role during resuscitation? and (2) How do critical care nurses prepare for the FSP role, and what are their perceptions of the training needed? This article presents findings for the first research question focused on role performance. Due to the different foci of the research questions and to ensure comprehensive presentation of the findings, results for the second research question (preparation for role) will be published separately. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ checklist) (Tong et al., 2007) was followed when preparing this manuscript (File S1).

3.2. Setting and participants

Purposive and snowball sampling produced a sample of 16 nurses from the southeast United States. Inclusion criteria were current or recent employment as a registered nurse (RN) in adult critical or progressive care units and having experience as an FSP. Paediatric RNs were not recruited, as the nature of paediatric resuscitations can differ from adult resuscitations, and the FSP role may be performed differently with parents. Other professionals (e.g. social workers and chaplains) were excluded. Although there was no specified stratification plan for the sample, efforts were made to recruit participants from varying hospital sizes and locales (large urban, medium suburban, small rural), unit types (general and specialty critical care, progressive care) and work shifts (days, nights).

3.3. Data collection

After ethics review approval, recruitment began by emailing known critical care nurses to identify individuals meeting inclusion criteria. Additionally, an email was sent to members of the local AACN chapter. None of the identified nurses who met the inclusion criteria declined to participate, and none withdrew from the study. Two members of the research team collected data through face‐to‐face individual interviews with participants during June to September 2019. Interviews were conducted in a private setting agreed upon by a participant and researcher. In beginning each interview, researchers reviewed study information, and participants provided written informed consent. Participants then completed a paper‐and‐pencil questionnaire to collect demographic and professional information, including the number of times they had performed the FSP role. Researchers followed a 12‐question interview guide (Table 1), and probing questions explored participant responses and encouraged elaboration. The semi‐structured interviews lasted 32 min on average (range 14–53 min), and participants received a $50 gift card for their time. Researchers recorded field notes at the end of each interview. Interviews were audio‐recorded and professionally transcribed. Ongoing preliminary analyses of interview data identified the point at which no new information was forthcoming. Saturation was reached upon interviewing 16 participants. Repeat interviews were not conducted, and the transcripts and findings were not returned to participants for checking.

TABLE 1.

Interview guide

|

1. Please describe your role as a critical care nurse. 2. Explain the process in your workplace when a patient codes and requires resuscitation. Does this process differ if family members are present at the hospital? 3. Please tell me about your experiences of being an FSP (or family facilitator) during patient resuscitation. 4. Let's discuss how you perform the FSP role. Please describe, step‐by‐step, what you do. In what ways do you work with family members…

5. What do you think are the priority, or most essential, parts of the FSP role? What actions, behaviours, etc. are especially important when performing this role? 6. Are there times when another member of the healthcare team (not nursing) is the FSP? Can you describe how they perform the role? Do you think there is a difference in the way they do it versus the way nurses do it? a 7. Let's go back to when you first started to perform the FSP role…how did you first begin to assume this role? a 8. Describe any role preparation or training you received or undertook, formally and/or informally. a 9. When you first served as an FSP, to what extent did you feel prepared for this role? What factors may have contributed to your feeling of being prepared (or unprepared)? a 10. What training do you think is important to help nurses prepare for the FSP role? a 11. Does your unit have a written policy or protocol that describes what you should do when you are the FSP? If so, please describe. a 12. Are there any other thoughts about FPDR, being an FSP, or role training that you would like to discuss? |

Findings reported in separate manuscript.

3.4. Data analysis

Questionnaire items were analysed descriptively. The verbatim transcripts were reviewed for accuracy by two of the researchers, and printed transcript documents were used for the data analysis. Thematic analysis of the interview data followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) method. To promote trustworthiness through investigator triangulation, three members of the research team participated in the data analysis. Analysis began with each researcher declaring personal biases relevant to the analysis. Each researcher read and re‐read the transcript documents, gradually becoming immersed in the data. Beginning with words and phrases as units of information, individual researchers formulated coding systems, most often using a colour or lettering system. Unit codes were aggregated into clusters or rudimentary themes. Then, all three researchers met virtually to compare their analyses. Analyses were notably similar in focus and scope, allowing for consensus on themes. Each researcher then took two weeks to consider the initial themes and re‐check data sources for each. The team met again to confirm the themes and agree on subthemes. After each group session, team members reflected on key decision points, such as whether themes were clearly distinct and the extent to which themes had subthemes.

Credibility of the analysis process and results was supported by incorporating both individual and group analyses. Dependability of the analysis and results was addressed through prolonged engagement with the data and rechecking codes and themes with the data set at varying points in the analysis. Researchers had between 5 and 40 years of high acuity nursing experience, and all had participated in FPDR as nurses and as FSP. Two of the three had researched FPDR for between 5 and 15 years. Confirmability and transferability were supported by an audit trail recorded during individual and group analyses.

4. RESULTS

Demographic and professional information for the 16 participants is presented in Table 2. Participants were working at seven different facilities. All had bedside experience, and two‐thirds were employed as direct care clinical nurses at the time of data collection. All participants had been an FSP, with two‐thirds having filled the FSP role 1–5 times.

TABLE 2.

Descriptive and professional characteristics of participants (N = 16)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Less than 30 years old | 9 | 56.25% |

| 30–39 years old | 1 | 6.25% |

| 40–49 years old | 2 | 12.5% |

| 50–59 years old | 2 | 12.5% |

| 60 years and older | 2 | 12.5% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1 | 6.25% |

| Female | 15 | 93.75% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White, non‐Hispanic | 14 | 87.5% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 0 | – |

| Black/African American | 1 | 6.25% |

| Asian | 1 | 6.25% |

| American Indian & Alaska Native | 0 | – |

| Native Hawaiian & Other Pacific Islander | 0 | – |

| Highest Nursing Degree Obtained | ||

| Diploma degree | 0 | – |

| Associate degree | 2 | 12.5% |

| Baccalaureate degree | 10 | 62.5% |

| Master's degree | 4 | 25% |

| Doctoral degree | 0 | – |

| Years of RN Experience | ||

| Less than 1 year | 0 | – |

| 1–2 years | 1 | 6.25% |

| 3–5 years | 8 | 50% |

| 6–10 years | 1 | 6.25% |

| 11–15 years | 3 | 18.75% |

| 16–20 years | 0 | – |

| More than 20 years | 3 | 18.75% |

| Years of Critical Care Experience | ||

| Less than 1 year | 0 | – |

| 1–2 years | 1 | 6.25% |

| 3–5 years | 9 | 56.25% |

| 6–10 years | 3 | 18.75% |

| 11–15 years | 1 | 6.25% |

| 16–20 years | 0 | – |

| More than 20 years | 2 | 12.5% |

| Current Job Position | ||

| Bedside nurse | 11 | 68.75% |

| Nursing management | 2 | 12.5% |

| Nursing education | 2 | 12.5% |

| Advanced practice nurse | 1 | 6.25% |

| Hospital Setting When FSP a | ||

| Large Urban | 10 | 62.5% |

| Medium Suburban | 4 | 25% |

| Small Rural | 3 | 18.75% |

| Type of Unit When FSP a | ||

| Progressive Care Unit | 2 | 12.5% |

| General Adult ICU | 12 | 75% |

| Specialty Adult ICU | 8 | 50% |

| Shift Worked When FSP | ||

| Day Shift | 9 | 56.25% |

| Night Shift | 4 | 25% |

| Both Day and Night Shift | 3 | 18.75% |

| Amount of Experience with FPDR | ||

| Less than 5 times | 7 | 43.75% |

| 5–10 times | 4 | 25% |

| 11–20 times | 3 | 18.75% |

| More than 20 times | 2 | 12.5% |

| Number of Times in FSP Role | ||

| Less than 5 times | 11 | 68.75% |

| 5–10 times | 3 | 18.75% |

| 11–20 times | 2 | 12.5% |

| More than 20 times | 0 | – |

Could select more than one; percentage does not total 100%.

Data analysis revealed six themes that addressed the first research question. Four themes encompassed subthemes that further organised and expressed the thematic content. Quotes attributed to specific participants are identified by the assigned number shown in Table 3, which lists participants’ setting, shift and experience.

TABLE 3.

Participant information

| Participant number | Hospital setting | Unit type(s) | Shift(s) worked | Years critical care experience | Number of times in FSP role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Rural | General | Days | 10 | <5 |

| P2 | Urban | General, Neuro | Days, Nights | 7 | 11–20 |

| P3 | Rural | General | Days | 3 | <5 |

| P4 | Urban | Neuro | Days | 4 | <5 |

| P5 | Urban | General, Neuro | Days | 25 | 5–10 |

| P6 | Suburban | Cardiac | Days | 4 | <5 |

| P7 | Suburban | General | Days, Nights | 5 | <5 |

| P8 | Urban | General | Nights | 33 | <5 |

| P9 | Urban | General | Days, Nights | 1 | <5 |

| P10 | Urban | General, Surgical‐trauma, Progressive | Nights | 13 | 5–10 |

| P11 | Urban | Cardiac | Nights | 3 | <5 |

| P12 | Urban, Rural | General, Surgical‐trauma | Nights | 4 | 5–10 |

| P13 | Urban | General, Progressive | Days | 10 | 11–20 |

| P14 | Suburban | General | Days | 4 | <5 |

| P15 | Suburban | General | Days | 4 | <5 |

| P16 | Urban | Neuro | Days | 3 | <5 |

4.1. Theme 1: Hard but rewarding role

Participants described their FSP experiences as hard but rewarding, recalling it as a ‘tough role’ P6 and ‘odd, challenging role’ P2. Being an FSP was especially ‘hard because you don't know what to say in those situations’ P6, and participants feared saying something that might make the situation worse. The FSP role was more challenging when a resuscitation happened unexpectedly or when family could not decide about stopping or continuing resuscitation.

Being an FSP is hard because nurses may experience intense emotions: ‘It was very traumatic for me…emotional for me…so that was really hard’ P2. When describing an FSP experience, one participant became notably tearful. Yet, when asked about strategies for coping afterwards, this participant said, ‘we still have the rest of the shift to go through…I just carried on as we nurses do’ P8. No participants discussed debriefing opportunities.

Although hard, participants felt the rewards outweighed challenges of the role. Inviting FPDR was viewed as providing ‘family‐centered care because [the family] were asked if they wanted to be in the room…they felt like “okay, you're not taking me away from my loved one”’ P6. Participants emphasised the importance of the FSP role in helping family make decisions: ‘At first it was uncomfortable for me, but it should be done, and they should be able to be there. It's important for them to see our efforts and what we're doing, to be able to have that decision to stop or continue’ P2. They also felt facilitated FPDR helps family members cope. Two participants commented: ‘She needed love and [someone] to pay her attention. And I just chose myself…I felt it was important’ P8 and ‘They tell you, “Thank you so much for everything.” And it is overwhelming’ P11.

Being an FSP was also personally rewarding: ‘It's very rewarding in the fact that you get to be with somebody in their most vulnerable time’ P13. Further, one believed being an FSP ‘helped me as a person…I feel like I look at life differently’ P16. The benefit of facilitated FPDR to the healthcare team was also explained: ‘ICU is a hard job, and sometimes we mask it by humor or something. It's [Dialog is] more appropriate if they're in the room. Almost feels you are more connected to the patient if they're there’ P11.

4.2. Theme 2: Be with

The words ‘be with’ and ‘be there’ were used by participants when describing the entirety of the FSP role. Examples included ‘the biggest thing is to be there’ P14, ‘you just be with them until whatever the outcome is’ P9 and ‘just be there with them…sometimes just having the presence, someone with you, goes a long way’ P4. Respondents stressed FSPs must stay with the family and not leave them: ‘You stand with them. Never leave them alone. Most people never experienced this in their life. So, you do have to give them a “You're not alone. Do you need me to hold your hand? If you need to hug me, if you need to lean on me, here I am”’ P13. Those who had witnessed family members unattended during resuscitation felt that being alone could be harmful: ‘They're confused…they don't understand. They're more upset if they don't have somebody’ P12. Family being unattended was more likely to occur in smaller hospitals and on night shift due to less staff, or ‘cavalry’ P10, arriving to assist with resuscitative care.

Participants indicated that to ‘be with’ the family, FSPs could not have an active role in resuscitating the patient. However, they could provide information to the resuscitation team, if needed. Never straying from their focus on being with the family, FSPs followed if the family stepped out of the patient room: ‘They kind of escorted themselves out because it was too much for them to see, and I just went with them’ P4.

Being with the family sometimes included the use of touch. Two participants explained: ‘I was right there with her, the whole time comforting her and patting her on the back. I didn't really talk a lot. I just let her know “I’m there with you, for you”’ P8 and ‘I put my hand on their shoulder while they just watch…so they don't feel so absent in the room’ P14. Participants stressed FSPs must sincerely demonstrate caring, and, if not sincere, it can negatively affect the family: ‘I think that's the big part…do you care or are you just trying to get this over with? They'll pick up on that if you don't’ P8.

4.3. Theme 3: Assess

A major aspect of the FSP role is assessing the family. Subthemes were ‘continuous assessment’ and specifically looking out for ‘family well‐being’ and ‘team disruption’.

4.3.1. Continuous assessment

Participants began to assess the family with their first contact and continued throughout the resuscitation. The first focus of their assessment was to gauge the family's emotional state: ‘I’m just trying to get a feel for them and where they are emotionally. You can read people's body language, their faces, their emotions…if they're going to be totally shocked by it, if they're expecting it. That can tell you how it's going to go when you bring them into the room’ P4. The initial assessment was especially important and more challenging if the FSP had not met the family.

After initial assessment, FSPs must ‘continue to assess…because that is your priority’ P13, collecting both verbal and non‐verbal data: ‘Once we got to the room and I saw how they responded, that's when I would be like, “Are you okay? Do you want me to explain things to you?” I paid attention to their non‐verbal cues and made sure they were okay’ P14 and ‘Just like with any patient, you're assessing the situation: What is it that they need? Are they crying? Are they doing the sign of the cross?’ P13. Performing ongoing assessment helps FSPs determine the family's level of understanding and desire for information, as well as their emotional state and need for support: “You assess and fill those knowledge gaps to help them understand. And you respond to their emotional response…what do they need?” P10.

4.3.2. Family well‐being

Another aspect of assessing was noticing family members’ emotional well‐being and knowing when to intervene to ensure safety. One participant explained: ‘I was genuinely worried for her safety because she was about to pass out. She was leaning up against the door. So, I got her a chair’ P9. At times, participants ‘helped them get out’ P7 to the hallway or ‘asked if they want to go to the waiting room or somewhere quiet or take a walk…just asking if they need to take a moment to step away so they're not right outside the room hearing all the things still going on’ P4. There were instances where families then desired to re‐enter the room: ‘They just need that intermittent break and then they'll come back’ P15. Though not common, some worked to protect family by suggesting they look away during traumatic procedures. One recalled saying: ‘At this point, we're going to shock them. This might be too much for you to watch. You might want to turn your head when they say all clear because it's going to give them a jolt.” You prepare them at each step what's going on, and it gives them that option’ P13.

4.3.3. Team disruption

While assessing emotional status, participants were also looking for the potential for family to become hysterical and disrupt team efforts. Though described as rare, participants were still on alert: ‘I've never had to escort them out for any reason. If I would have needed to…if they're completely hysterical and it's interfering with care…and that's in any situation with healthcare though, use nursing judgment…you have the sixth sense of, “This isn't going to go well”’ P16. While some described helping family ‘calm down’ P9 in the room, others discussed having family step out by ‘kind of easing them out of the room. Not telling them, “Hey, you got to get out of here!” But just in a calm voice saying, “Let's take a break, let's take a breather and reset,” because it is hard’ P6. There were others who had asked family to leave but ensured they could still see in: ‘There have been just a handful of instances where they're so hysterical that it's hard to concentrate and communicate…and asked them to step out of the room, still being able to see in the windows’ P2. If family stepped out, they were accompanied by the FSP so they could continue to receive explanations and support.

4.4. Theme 4: First moments

At the start of a resuscitation, participants first verified all patient care roles were filled prior to focusing on the family. A nurse manager participant described this process: ‘When the code calls, I run out there. I make sure they are responding appropriately…the code cart is there, people are doing compressions…because if not, I’ll intervene. My next look is where's the family?’ P5. Next, participants began a quick First Moments process that consisted of ‘ask’, ‘prepare’ and ‘position’ the family.

4.4.1. Ask

Participants first greeted the family and described their purpose: ‘Introduce yourself so they understand who you are and that you're there to answer any questions they have, and you'll be explaining what's going on’ P7. Next, they assessed the family member's relation to the patient and their decision‐making capacity: ‘It's important to know that's the right person in the room. Is this great cousin twice removed versus is this the decision maker who is going to be able to decide code status? I think sometimes it's situational awareness’ P10. Another described that they typically recognise family members of patients, ‘or we'll get in report: “That person is in the room, they've been here all day.” But if we don't recognize them, we take them out…just HIPAA’ P11. Others asked about their relation: ‘If I don't know them, I’ll just press and say, “What's your relation to the patient?”’ P4.

Next, participants asked the family if they wanted to witness the resuscitation. One pre‐condition was establishing the number of family members who could fit in the room. Most FSPs invited 1–3 family members, due to room size restrictions: ‘If there's a bunch of people, we say, “We can only have two or three people in the room right now.” And they're pretty good at deciding in that situation. I’ve never had anyone argue…they pretty much listen to you in that moment’ P12. If family was not in the room at the code onset (i.e. in waiting room), participants went to them and asked if they wanted to witness the resuscitation. If they were already in the room, participants asked: ‘Would you like to stay and watch, or do you want me to escort you out? What do you feel is going to be best for you?’ P4. Offering the option was important because ‘in the moment, sometimes the family member is just stuck. It helps having someone ask what they prefer: “Do I stay beside you in the room, or do you want to step away from the chaos?”’ P6. No participants discussed asking patients about FDPR wishes, and only one discussed an impending code with family in advance: ‘Gave them a heads‐up, and that's when they both said, “I want to…” They both asked’ to be present P8.

4.4.2. Prepare

Participants prepared the family by giving general information on the events occurring: ‘Usually start by saying your loved one's heart has stopped, here's the reason why if we know the reason, and kind of walk through what we've done. Then ask, “Would you like to be present and observe what we're doing to try to save their life?”’ P2. Others provided more detail about what they would see: ‘“Before we go in the room, I just want to explain what you're about to see.” I tell them if they're on a ventilator, what that looks like. I explain if it's traumatic, there might be a lot of blood’ P12 and ‘“The team has them disrobed so they can do compressions to try to get their heart to go back, and there's respiratory therapy who is breathing.” Just go through what they're going to see’ P3.

The FSPs also prepared the resuscitation team by informing them that family was present or about to enter: ‘“The family is coming in” or “We have family back here”’ P11. One discussed introducing the family to the physician leading the resuscitation, ‘This is Ms. X. This is her husband’ P10. Participants noted some physicians asked for family to come in; however, some were resistant. A nurse manager participant discussed advocating for the family when a physician expressed resistance: ‘If the provider says no, all due respect though, I will talk to them, “Look, they have the right.” We have to be the advocate because sometimes providers see the medicine, and they need to see the patient, family’ P5.

4.4.3. Position

Next, participants focused on positioning the family in the room. Ensuring the family was not in the team's way was repeatedly discussed: ‘Get them to an area where they're not in the way, but can still see everything’ P12. This was accomplished by positioning the family ‘in a pocket in the back of the room’ P2 or ‘pulling them in a corner’ P5. Having a chair close by was repeatedly suggested. While some FSPs stood with the family as they watched the resuscitation, others preferred ‘to sit them down so they're not in the midst of all the chaos’ P4. Another felt sitting together helps build trust: ‘I had just walked into the room, so I didn't build that rapport or trust yet. So, you have to do all those little things they teach you in nursing school to build rapport really fast. I sit down at their level…just so they knew they were in control’ P16.

When participants positioned the family, they made sure they could ‘see everything happening. I feel that's big because they can see we're doing everything we can’ P12. At the same time, some acknowledged family members needed to look away at times: ‘Some of it, she chose to turn her back to’ P8. One felt hearing was as helpful as seeing: ‘I think that hearing sometimes is the most pivotal piece. I think they don't always realize what's going on just seeing; the verbalization piece gives them a better understanding. They hear what's going on and know the gravity of the situation…so if the provider comes to them to question if they're continuing, they're able to make a better judgement based on observations and the things they've heard’ P10. Yet, due to small rooms, some participants had to position the family just outside the room, making sure they could still see in through the doorway or window. Some families preferred to be outside the room: ‘They didn't want to step in because we were very busy, but they did get full view. They got to see the CPR, defibrillation, pulse checks’ P8. However, some cautioned against positioning the family where the resuscitation team could not see them: ‘When the family's not in the room, but they're still right outside the room, we're not cognizant of them. So, things could be said that would maybe be perceived as inappropriate…it could be very problematic’ P7.

4.5. Theme 5: Explain

Many participants felt explaining the team's care to the family was one of the most important aspects of the FSP role, and ‘sometimes the answers are the support they need’ P10. The theme Explain consisted of three subthemes: ‘tailoring explanations’, ‘simple terms’ and ‘facilitating decision‐making’.

4.5.1. Tailoring explanations

Participants began offering explanations when preparing the family and continued throughout the resuscitation and aftercare. Explaining was perceived as crucial because family members ‘really don't understand’ P4. Typically, FSPs explained by ‘talking them through what was happening as it was happening’ P7 and ‘describing each step we're doing and why we keep doing what we're doing’ P1. To explain the patient's situation, FSPs need to be able to assess progress of the resuscitation from a distance. When the family and FSP were in the hallway, explaining was challenging: ‘The one that stepped out of the room…I was trying to explain what was going on, not realizing they had gone all the way from trying to intubate then nasal intubate then trach. And this was somebody that had not wanted to be intubated more than 24 hours’ P16.

Tailoring explanations to answer family questions were a key aspect of the FSP role. Some participants had experiences in which the family did not have many questions: ‘They don't know questions to ask…their focus is on their loved one and get them to breathe again, get their heart going again. That's their number‐one thing’ P13. Others described being asked a multitude of questions about the care being provided: ‘We answer questions: “Why are they doing compressions?” I’ll explain the circulation problem. “What are they pushing into their IV? Why are they shocking? Why aren't they shocking?”’ P11. Family also asked if the patient could feel the care interventions: ‘His wife was asking…worried he was feeling pain. And told her he's unresponsive right now’ P9. Some questions were harder to answer: ‘The family member asks, “Are they going to be okay?” Or they're pleading, “Please tell me it's going to be okay. Get them back.” I just say what we're doing, “We're doing CPR”’ P15.

Participants gauged the extent of explanation desired by assessing family members. The FSPs frequently ‘asked if they had any questions about what was going on, or if they needed to talk through anything’ P6. Participants also relied on non‐verbal cues: ‘I just kind of play it by ear and see their reaction. One daughter turned her back and couldn't watch. Where the other daughter told us, “I want to know everything that's going on.” The first one…she just needed comfort and love. She didn't want a play‐by‐play; she just wanted to be in his presence. The second one definitely wanted a didactic, and that's what I gave her’ P8.

4.5.2. Simple terms

Participants stressed the importance of explaining ‘in simple terms what's happening and why the code team is doing what they're doing’ P2. The FSP also needs to interpret words the team is saying. For example, ‘Why are they giving epi? What is epi?’ And…”You know what adrenaline is? We're trying to restart the heart.” Just trying to put it into terms they might understand’ P11. Tailoring explanations often required using layman's terms: ‘I tried to use wording she would understand. She knew he had the ICD in place…I just told her it was firing at the wrong times, and it was irritating his heart’ P9. While FSPs based their explanations on the family member's level of understanding, they stressed: ‘Don't talk over their head…even if they do have a basic understanding, in that moment there's so much going on. You need to use basic terms’ P12. Using simplified language makes it less overwhelming: ‘In simple form because they're already overwhelmed. The only thing they care about is that person in that bed’ P13.

When asked how they determined whether family understood their explanations, one participant stated: ‘That's hard because it's not one of those teach‐back moments…I don't know if they really understand. You can usually tell if some people are getting it based off their facial expressions. But it's so hard because everybody responds to those situations differently’ P12. Another described relying on non‐verbal cues: ‘Sometimes you gauge folks based on their reactions. Like you can tell me you understand, but you still have a perplexed look on your face’ P10.

Finally, two participants brought up challenges faced when supporting families who did not speak English. In one case, a Spanish‐speaking colleague came to serve as FSP; however, this was not always possible. In these situations, an in‐house interpreter was able to come to the room ‘and sit with us…the three of us together in the corner’ P12. They also could access remote interpreters, but the family had to go into the hallway to hear.

4.5.3. Facilitating decision‐making

Participants felt explaining was important because the family would likely need to make a decision about whether to continue or end the resuscitation: ‘Just be very informative and supportive. Because it's a lot to take in all at once, and then they might have to make a decision 5 or 10 seconds later’ P14. By providing explanations, FSPs helped build family trust in the team's care, which is important to help them make decisions: ‘I feel like families have an easier time making that decision if they understand that you did everything…it increases trust’ P16. To build trust, there needs to be an ‘open line of communication. Let them know you're going to be up‐front, honest, and provide the information needed to feel confident in making decisions’ P4. To ensure trust was not jeopardised, participants chose their words carefully: ‘Do not say, “It's going to be ok.” Don't give false hope. If you know this outcome is going to be bad, you can kind of prepare them. Don't say, “We're going to get their heart restarted”…say, “We're going to try.” Don't use definitive words’ P12.

Participants described what they said to prepare family to make a decision: ‘”We've been doing this for 30 min and every time that Epi wears off, we're just going through that same cycle.” I just tried to be vague but informative at the same time. Giving them the basic facts of, you know, I don't think this is going so well, it's not working’ P14. One participant indicated that family often needed to be told what their options are as follows: ‘It's that length where we're at 30 minutes and I would be like, “What do you want to do?” And that's when they're like, “What can I do?” And we'll give them options. Because they can't think. We're their voice’ P5. To aid decision‐making, participants also made statements to empower the family: ‘I’ve said before, “if you want us to stop, you tell us”’ P2. They also helped family consider what the patient would want: ‘If this is what you feel [the patient] would want, we will continue. But if we think they may be tied to this forever, is that what they would want?’ P16. When a family member expressed their wishes about next steps, FSPs verbalised their decisions to the team.

4.6. Theme 6: Support

In addition to being with the family and providing explanations, participants also performed other actions to provide support: ‘compassionate demeanor’, ‘to touch or not’, ‘intentional silence’, ‘meeting needs’ and ‘time with the patient’.

4.6.1. Compassionate demeanour

All participants agreed on how FSPs should present themselves when interacting with families. Specifically, FSPs need to have a ‘calm, calm demeanor’ P10, to ‘talk slow, calm, and watch your tone…you need to have compassion in your voice’ P12, and to ‘have a softness…you can't be harsh, you have to soften your words when you're talking to them’ P1. Another elaborated stating: ‘You got to be kind and patient. You cannot be short or to‐the‐point. You got to have that warm, fuzzy feeling and have a lot of compassion. Because that's what they need’ P13. One participant described performing the FSP role with ‘pure comfort and love’ P8.

4.6.2. To touch or not

While touch may be viewed as a way to let family know the FSP is with them, FSPs have to consider how much touch to use, if any, when offering direct physical support. Most often, participants used touch by holding the family member's hand, putting their hand on their shoulder, rubbing their back and giving a hug. One participant remarked: ‘Just a simple touch. Touch is really impactful. They can pick up your energy, they can feel a comforting touch’ P13. Yet, participants acknowledged that not all family members want touch, and FSPs need to assess their desire for and response to touch. Use of touch was guided by reading non‐verbal cues: ‘She wanted no touch at all…you could feel it. There are just things you have to go on instinctively. And when it was over, I just said “I’m really sorry,” but she didn't want any hugs either. She said goodbye and that was it’ P8.

To provide support, some participants asked family members if they wanted to move to the bedside and touch the patient or hold their hand. However, this depended on whether there was enough room at the bedside and the family's demeanour: ‘If they have a lot of lines, vent, all that stuff, I say, “Just watch out for all these lines. But you can hold their hand, talk to them, pray with them, whatever you want to do”’ P15. One participant explained the importance of helping the family member touch the patient: ‘If there is room to get to their hand, that's where we'd like to have them. That way they're kind of right there and comforting them. And it's comforting for us to see someone with the patient while we do all this stuff. In a perfect world, they're at the bedside’ P11.

4.6.3. Intentional silence

Participants noted the importance of periodic silence, a break from the FSP’s continual explanations: ‘There's sometimes pauses and silence. Just being there and waiting to hear what they're thinking and feeling, versus just throwing everything at them, “They're doing this, this, this.” I don't think that would've been as helpful as holding their hand, sitting there’ P16. Times of silence were also deemed helpful to ‘just let them take it in, however long that is, and let them guide things’ P14. Participants again relied on their assessment to determine when to use silence: ‘Some people don't really want to talk, and sometimes we're just sitting there in silence. Some people want to talk about everything. Some people want you to leave them alone. You have to gauge people, read body language’ P12.

4.6.4. Meeting needs

It was felt that FSPs must be ‘adaptable to what [family members] need because every situation is going to be different’ P2. Some described asking family about their needs: ‘If he needs anything, does he need to sit down, did he need some tissues?.. “What can I do for you?”’ P14. To best understand family needs, FSPs must ‘listen to what their needs are…it's not just a grab some tissues and water’ P10. Participants also assessed non‐verbal cues; however, this was not always easy: ‘Some family members are very calm, and you almost don't know how to read them. Trying to provide empathy can be more challenging for those who are more stoic and reserved. Whereas someone who is openly upset, you know that you're comforting. Someone who says “I don't understand what's going on,” you are explaining what's happening. I think those are the three personality types I’ve seen over the years. But those who were more reserved, were the more difficult’ P10.

Mixed perspectives on addressing spiritual needs of families were expressed. While some participants had prayed with family and felt it was helpful, others did not because ‘I don't know somebody's religion…I wouldn't want to offend’ P16. Some asked the family if they wanted to pray or they relied on assessments to determine spiritual needs: ‘I said, “Your dad is going to heaven,” that kind of stuff. I know people have different beliefs, but she expressed, “My daddy will not suffer anymore, and he'll be in heaven with my mom.” So, I knew’ P8.

As a way of meeting family needs, some participants acknowledged reaching out for additional support persons, such as a chaplain. Others suggested asking the family if they want a chaplain's presence. Participants also asked whom they could contact in terms of family or friends: ‘They get to the point where you say, “This might not have the best outcome. Can I call some other family members? You're going to need some more support here other than just us. You're going to want the people you know the best.” And usually when codes start and there's only one family member, we're already calling to say, “You need to get here as soon as possible.” But we also don't say, “We're in the middle of a code.” We don't want them having a wreck’ P13. Because FSPs need to stay with the family, they often asked another nurse or supervisor to make phone calls.

4.6.5. Time with the patient

Participants were asked how they support family when resuscitations concluded. If it is a positive outcome (i.e. patient survives), participants usually ‘ask them to step out because there's a lot that needs to be done for the patient in terms of different tests, procedures: “We got their heartbeat back, but they're still very critical…we're going to need you to step out so we can continue working.” Most families are agreeable with that’ P14. Typically, the family then receives an explanation of the situation from the physician and nurse, and then can return to the bedside. If the patient coded on a progressive care unit, FSPs accompanied the patient and family to the ICU: ‘We typically stay with that family to get them to that higher level of care, keeping the other charge nurse aware this individual is present. I’ve had to sit with some family in waiting rooms. They get [the patient] settled and then let the family come back. Not a prolonged period of time, but that feels like hours to that loved one who doesn't know what's going on behind those doors’ P10. Another participant from progressive care stopped in to see the family the next day, a recommended practice to provide support: ‘If you're going to be back, just go and check on them and say, “Just checking on you.” That action means more than anything’ P13.

If it is a negative outcome (i.e. patient dies), participants ‘offer family the chance to stay with the patient and let them know we can get the patient cleaned up so they can spend time with them. Kind of giving the family options for what they feel is best for them’ P4. Participants discussed bed availability as a barrier to giving family extended time in the room with their loved one: ‘Sometimes they give us an hour to get the family out of the room, and sometimes we get longer. Depends on how many empty beds we have. I had one I did have to push out faster than I was comfortable with. I'll usually try to push back’ P16.

After the death of a patient, participants indicated there were no limits on the number of family members allowed in the room. If no other family was present, some FSPs stayed in the room, sitting with the family member. They also ensured the family received an explanation of what happened and access to additional support: ‘The physician, primary nurse, and person who's been with the family in a private area…explain what happened, why we think it happened, and offer as much support as they need. We offer a chaplain, case manager, and social worker to try to help them grieve and work through what needs to be done next’ P2. Other measures of support were having a moment of silence and providing heartbeats in a bottle (EKG of last heartbeat placed into a vial). Some participants knew their unit sent families a card; however, they were unaware of any other follow‐up. Yet, one nurse manager participant who had given their business card to all patients/families shared: ‘I had a patient's family member call weeks after to say, “You gave a medication, and it spiked the heart rate. Why did it drop again?” Because they're trying to remember everything that happened that they didn't ask in that moment because it wasn't their primary focus’ P13.

5. DISCUSSION

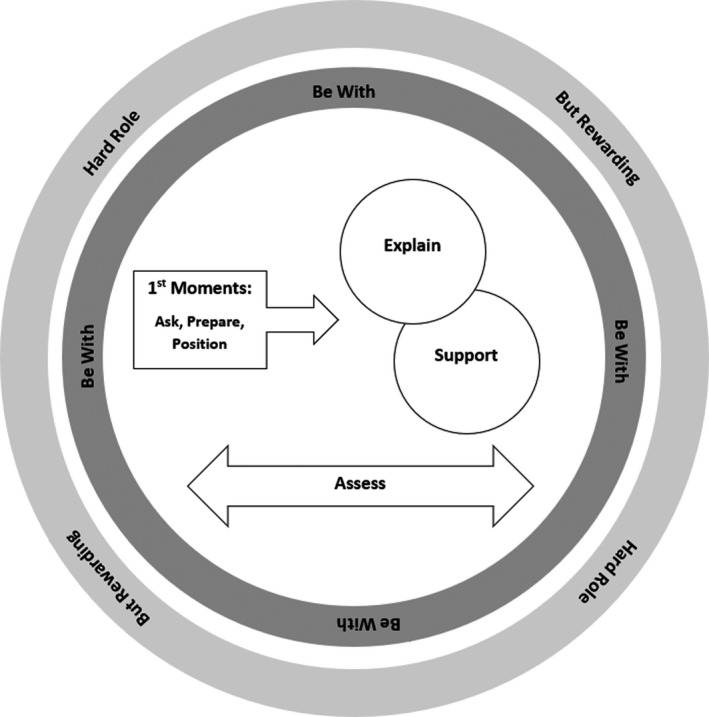

This study extends what is known about the FSP role by explicating how this role is perceived and enacted by nurses. Six themes captured the essence of participants’ accounts and how they functioned in the FSP role. The six themes were interconnected, with overlap, as depicted in Figure 1. Although the sample was intentionally diverse in unit type, hospital locale and shifts worked, consensus on the six themes across participants was clear with no notable differences except for staffing issues in smaller hospitals and on night shift that limited nurse availability to serve as FSP.

FIGURE 1.

Diagram of family support person role

Despite continued controversy surrounding FPDR, participants in this study agreed it was a favourable practice. As all participants had FPDR and FSP experience, this finding is consistent with studies showing heightened support among healthcare professionals who have experienced FPDR (Bellali et al., 2020; Powers & Reeve, 2018; Twibell et al., 2018). Newly documented in this study was participants’ perspective that their role as an FSP created a better FPDR experience for families. Participants also found it satisfying to be an FSP, as families were grateful for their guidance in a time of crisis. Yet, most of the FSPs described the role as challenging, primarily due to two reasons: participants were uncertain of how to communicate with families, and they experienced intense emotions when enacting the role. This underscores the importance of role preparation and staff support interventions, which have been recommended in prior studies (Firn et al., 2017; Giles et al., 2016; James et al., 2011; Powers, 2018; Sak‐Dankosky et al., 2018; Twibell et al., 2018).

The most pervasive consensus across participants was that the FSP should ‘Be With’ families who are witnessing a resuscitation. Participants’ descriptions of being with reflect the broader concept of nursing presence, which recently has been explicated in nursing discourse and declared a core relational skill for nurses (Fallahnezhad et al., 2021; Gelogahi et al., 2018; Mohammadipour et al., 2017). Enactment of presence typically includes nurses’ use of self through therapeutic communication and physical and psychological availability, which includes full attentiveness and intentional active listening (Mohammadipour et al., 2017; Stockmann, 2018). Participants in this study similarly emphasised being physically and directly present with the family, while being attentive and compassionate, with singleness of focus devoid of other care responsibilities. Interestingly, the theme of Be With was not noted in the two prior studies conducted with social workers and chaplains (Firn et al., 2017; James et al., 2011). Nurses with refined relational skills and the capacity for being fully present may bring a unique contribution to the FSP role that other professionals do not.

Being with the family began in the first moments of the resuscitation. Participants described building trust, noting it was important for family to understand the FSP was solely available to them. They described more ease with initiating FPDR among families they knew, while social workers and chaplains typically lacked a pre‐existing rapport, which was perceived as challenging (Firn et al., 2017; James et al., 2011). In these first moments of nurse‐family interaction, FSPs assessed many data points, quickly focusing on family openness for FPDR. Participants described various methods of assessment and utilising verbal and non‐verbal cues to tailor explanations and support. They emphasised the high variability in responses from families, making assessment both crucial and challenging. Firn et al. (2017) and James et al. (2011) also cited assessment as a vital role component; however, our findings provide further insight about specific data to assess and when to intervene, for example, when to use touch and how to offer information as resuscitation progressed. As reflected in the data and in a prior study of nursing presence, being fully attentive with families increases ease in assessment and reveals data that could be missed otherwise (Hansborough & Georges, 2019).

Just as being with and assessing the family began in the first moments, so did offering explanations. Participants prepared family to enter the resuscitation room by explaining what they would see and then continued to explain resuscitation activities in simple terms, tailored to their level of comprehension. It was felt that keeping families aware of how the resuscitation was evolving was vital to prepare them to make decisions about whether to continue resuscitation. Participants in the James et al. (2011) study similarly deemed explanations an essential part of the FSP role; however, explaining resuscitation activities was more difficult for chaplains. Firn et al. (2017) discussed how social workers helped families engage in decision‐making; however, explaining care was not highlighted. Our findings reflect the clinical knowledge nurses possess to narrate care.

While explanations were a type of support, participants offered multiple other support measures. Participants stressed the need to speak calmly and compassionately, offering comforting touch when indicated. Explanations were strategically balanced with periods of silence so family members could process, an approach used by nurses present with persons in crisis (Mohammadipour et al., 2017). Participants continued to offer support after resuscitation, staying with the family until the patient was stabilised, or if a negative patient outcome, FSPs arranged for them to have time in the room and remained available. Participants in this study knew of no support for families upon leaving the hospital following a patient's demise. How nurses and hospitals can support families post‐FPDR is one of many inquiries yet to be explored as nurses implement family‐centred care and create further evidence about the novel FSP role.

5.1. Practice recommendations

Findings are relevant for nurses and healthcare organisations committed to family‐centred care and FPDR. When creating clinical guidelines for FPDR, content can be included on the FSP role, especially as future studies continue to explicate role activities. Through high‐ or low‐fidelity simulations, educators can support nurses in developing necessary skills to function in the FSP role. This study offers wording nurses can consider when refining communication skills. We also suggest the implementation of formal debriefing for nurse FSPs. Finally, participants did not know of post‐hospital support for families who experienced FPDR, and this is an identified need.

6. RESEARCH RECOMMENDATIONS

This study adds to the limited knowledge about enacting the FSP role. Study replication in other locales may yield more evidence to guide formation of clinical guidelines. The FSP role as enacted by non‐critical care nurses and those who work in paediatric care settings should be explored as it is possible that aspects of the role are performed differently in these settings. Family members’ experiences with FSPs can be studied to capture their role perceptions and preferences. Future qualitative studies may focus specifically on the ‘Be With’ theme, with the aim of connecting this aspect of the FSP role with the broader concept of nursing presence. Questions remain about how nurses can best prepare for the FSP role and who indeed is the clinician most qualified to serve as FSP. Once evidence accumulates and clinical guidelines are developed, research can examine the outcomes of family members who are cared for by nurses serving in a standardised FSP role. Lastly, nurses’ outcomes should be examined to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions to support FSPs.

6.1. Limitations

A study limitation is the small sample size; however, the point of data saturation was clear after 16 participants provided data. Next, it was a self‐selected sample, and nurses who volunteered to participate may have been more committed to the FSP role and may have had more positive experiences than nurses who did not volunteer. Some participants were recruited through AACN, an organisation supportive of FPDR, suggesting participants may have been more favourable about FPDR than the general nursing population. Similarly, the sample consisted of nurses who worked in critical and progressive care, and their FSP experiences may differ from nurses working in other settings where cardiac arrest occurs less frequently. Next, participants were not asked how recently they functioned in the role, so limited recall from experiences could have influenced data shared. Finally, participants were from one geographical locale, which could affect transferability of results to other locales. Despite these limitations, our findings provide novel insight into the FSP role as perceived and enacted by critical care nurses.

7. CONCLUSION

This study was the first to explicate the role activities of the FSP through data provided by critical care nurses experienced in the role. Findings reflect both the benefits and challenges of the FSP role. Key role activities were being present with family, continuously assessing family and environment, offering explanations and providing multi‐faceted support. The findings provide direction for future studies of the FSP role, eventual formation of clinical guidelines and design of education to prepare nurses to enact the role.

7.1. Relevance to clinical practice

The FSP role as described in this study represents a professional, clinical autonomous nursing role. Nurses are educationally and experientially prepared to assess families in crisis; quickly develop a trusting relationship; communicate therapeutically; and make independent decisions in selecting from a variety of support approaches. Practising with a high level of autonomy has been linked to improved health outcomes and nurses’ work satisfaction (Labrague et al., 2019; Pursio et al., 2021). Clinical nurses, managers and hospital shared governance systems can empower and prepare nurses to serve as FSPs by creating guidelines allowing nurse‐facilitated FPDR and including content on the FSP role. Continued explication of the FSP role may yield new insights into the role and how nurses can prepare.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design: KP; Participant recruitment and data collection: KP and JMD; Data analysis and manuscript writing: KP, JMD and KRT.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

Powers, K. , Duncan, J. M. , & Renee Twibell, K. (2023). Family support person role during resuscitation: A qualitative exploration. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 32, 409–421. 10.1111/jocn.16248

Funding information

This work was supported, in part, by funds provided by the University of North Carolina at Charlotte

REFERENCES

- American Association of Critical‐Care Nurses (2016). AACN practice alert: Family presence during resuscitation and invasive procedures. Critical Care Nurse, 36, e11–e14. 10.4037/ccn2016980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellali, T. , Manomenidis, G. , Platis, C. , Kourtidou, E. , & Galanis, P. (2020). Factors associated with emergency department health professionals’ attitudes toward family presence during adult resuscitation in 9 Greek hospitals. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 39(5), 269–277. 10.1097/dcc.0000000000000417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, J. E. , Aslakson, R. A. , Long, A. C. , Puntillo, K. , Kross, E. , Hart, J. , Cox, C. E. , Wunsch, H. , Wickline, M. A. , Nunnally, M. E. , Netzer, G. , Kentish‐Barnes, N. , Sprung, C. L. , Hartog, C. S. , Coombs, M. , Gerritsen, R. T. , Hopkins, R. O. , Franck, L. S. , Skrobik, Y. , … Curtis, J. R. (2017). Guidelines for family‐centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Critical Care Medicine, 45, 103–128. 10.1097/ccm.0000000000002169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallahnezhad, T. , Norouzadeh, R. , Samari, B. , Ebadi, A. , Abbasinia, M. , & Aghaie, B. (2021). Nurses’ presence at the patient bedside: Challenges experienced by nurses. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-513295/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Firn, J. , DeVries, K. , Morano, D. , & Spano‐English, T. (2017). Social workers’ experiences as the family support person during cardiopulmonary resuscitation attempts. Social Work in Health Care, 56, 541–555. 10.1080/00981389.2017.1292986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelogahi, Z. K. , Aghebati, N. , Mazloum, S. R. , & Mohajer, S. (2018). Effectiveness of nurse's intentional presence as a holistic modality on depression, anxiety, and stress of cardiac surgery patients. Holistic Nursing Practice, 32(6), 296–306. 10.1097/hnp.0000000000000294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles, T. , de Lacey, S. , & Muir‐Cochrane, E. (2016). Factors influencing decision‐making around family presence during resuscitation: A grounded theory study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72, 2706–2717. 10.1111/jan.13046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansbrough, W. B. , & Georges, J. M. (2019). Validation of the presence of nursing scale using data triangulation. Nursing Research, 68(6), 439–444. 10.1097/nnr.0000000000000381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Patient‐ and Family‐Centered Care (n.d.). Core concepts of patient‐ and family‐centered care. http://www.ipfcc.org/about/pfcc.html

- James, J. , Cottle, E. , & Hodge, D. (2011). Registered nurse and health care chaplains experiences of providing the family support person during family witnessed resuscitation. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 27, 19–26. 10.1016/j.iccn.2010.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinpell, R. , Heyland, D. K. , Lipman, J. , Sprung, C. L. , Levy, M. , Mer, M. , Koh, Y. , Davidson, J. , Taha, A. , & Curtis, J. R. (2018). Patient and family engagement in the ICU: Report from the task force of the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine. Journal of Critical Care, 48, 251–256. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrague, L. J. , McEnroe‐Petitte, D. M. , & Tsaras, K. (2019). Predictors and outcomes of nurse professional autonomy: A cross‐sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 25, e12711. 10.1111/ijn.12711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadipour, F. , Atashzadeh‐Shoorideh, F. , Parvizy, S. , & Hosseini, M. (2017). Concept development of “nursing presence”: Application of Schwartz‐Barcott and Kim's hybrid model. Asian Nursing Research, 11(1), 19–29. 10.1016/j.anr.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers, K. A. (2017). Barriers to family presence during resuscitation and strategies for improving nurses’ invitation to families. Applied Nursing Research, 38, 22–28. 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers, K. A. (2018). Family presence during resuscitation: The education needs of critical care nurses. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 37(4), 210–216. 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers, K. , & Reeve, C. L. (2018). Factors associated with nurses’ perception, self‐confidence, and invitations of family presence during resuscitation in the intensive care unit: A cross‐sectional survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 87, 103–112. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pursio, K. , Kankkunen, P. , Sanner‐Stiehr, E. , & Kvist, T. (2021). Professional autonomy in nursing: An integrative review. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(6), 1565–1577. 10.1111/jonm.13282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sak‐Dankosky, N. , Andruszkiewicz, P. , Sherwood, P. R. , & Kvist, T. (2018). Health care professionals’ concerns regarding in‐hospital family‐witnessed cardiopulmonary resuscitation implementation into clinical practice. Nursing in Critical Care, 23(3), 134–140. 10.1111/nicc.12294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockmann, C. (2018). Presence in the nurse‐client relationship: An integrative review. International Journal for Human Caring, 22(2), 49–64. 10.20467/1091-5710.22.2.49 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tíscar‐González, V. , Gea‐Sánchez, M. , Blanco‐Blanco, J. , Pastells‐Peiró, R. , De Ríos‐Briz, N. , & Moreno‐Casbas, M. T. (2021). Witnessed resuscitation of adult and pediatric hospital patients: An umbrella review of the evidence. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 113. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. , Sainsbury, P. , & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toronto, C. E. , & LaRocco, S. A. (2019). Family perception of and experiences with family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28, 32–46. 10.1111/jocn.14649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twibell, R. S. , Siela, D. , Neal, A. , Riwitis, C. , & Beane, H. (2018). Family presence during resuscitation: Physicians’ perceptions of risk, benefit, and self‐confidence. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 37(3), 167–179. 10.1097/dcc.0000000000000297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twibell, R. , Siela, D. , Riwitis, C. , Neal, A. , & Waters, N. (2018b) A qualitative study of factors in nurses’ and physicians’ decision‐making related to family presence during resuscitation. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 27, e320–e334. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/jocn.13948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardanjani, A. E. , Golitaleb, M. , Abdi, K. , Kia, M. K. , Moayedi, S. , Torres, M. , & Dehghan‐Nayeri, N. (2021). The effect of family presence during resuscitation and invasive procedures on patients and families: An umbrella review. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 47(5), 752–760. 10.1016/j.jen.2021.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material