Abstract

Objective

To review the evidence from clinical trials of follow up of patients after curative resection for colorectal cancer.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of intensive compared with control follow up.

Main outcome measures

All cause mortality at five years (primary outcome). Rates of recurrence of intraluminal, local, and metastatic disease and metachronous (second colorectal primary) cancers (secondary outcomes).

Results

Five trials, which included 1342 patients, met the inclusion criteria. Intensive follow up was associated with a reduction in all cause mortality (combined risk ratio 0.81, 95% confidence interval 0.70 to 0.94, P=0.007). The effect was most pronounced in the four extramural detection trials that used computed tomography and frequent measurements of serum carcinoembryonic antigen (risk ratio 0.73, 0.60 to 0.89, P=0.002). Intensive follow up was associated with significantly earlier detection of all recurrences (difference in means 8.5 months, 7.6 to 9.4 months, P<0.001) and an increased detection rate for isolated local recurrences (risk ratio 1.61, 1.12 to 2.32, P=0.011).

Conclusions

Intensive follow up after curative resection for colorectal cancer improves survival. Large trials are required to identify which components of intensive follow up are most beneficial.

What is already known on this topic

There is a lack of direct evidence that intensive follow up after initial curative treatment for colorectal cancer leads to increased survival

Guidelines are inconclusive and clinical practice varies widely

What this study adds

The cumulative analysis of available data supports the view that intensive follow up after curative resection for colorectal cancer improves survival

If computed tomography and frequent measurements of serum carcinoembryonic antigen are used during follow up mortality related to cancer is reduced by 9-13%

This survival benefit is partly attributable to the earlier detection of all recurrences, particularly the increased detection of isolated recurrent disease

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the second most common malignancy in Western societies and the second leading cause of death related to cancer.1 At the time of initial diagnosis, about two thirds of patients undergo resection with curative intent, but 30-50% of these patients will relapse and die of their disease.2 Some authors have postulated that intensive follow up would lead to early detection of recurrent disease or metachronous (second colorectal primary) tumours, or both, and thus improve survival, while others have questioned the need for follow up at all.3 This is reflected in current UK guidelines for the management of patients with colorectal cancer, which state that there is “no evidence” of survival benefit with intensive follow up4 or that it is “not worth while.”5 There is currently wide variation in follow up.6–8 For example, the Wales and Trent audits reported that among colorectal and gastrointestinal surgeons, 57% included the use of colonoscopy in their surveillance programme at a frequency of three times over five years to annually. Furthermore, some 13% of gastrointestinal surgeons offered no routine testing at all.6 Among these many different protocols, the costs to health services are considerable and need to be justified with evidence.

Several randomised controlled trials have addressed this issue, but none had sufficient statistical power. Two meta-analyses on studies of follow up after treatment of colorectal cancer have been published, but one was based entirely on non-randomised data9 and the other on combined randomised trials with cohort studies.10 We carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials to determine whether there is any benefit of intensive follow up strategies after curative resection for colorectal cancer.

Methods

Search strategy—Using Cochrane methodology11 we searched Medline, Embase, CANCERLIT, and the Cochrane controlled trials register for relevant studies (box B1). We considered trials in any language. We supplemented electronic searches by hand searching reference lists, reviews, and abstracts from meetings. National trial registers were also searched for unpublished trials. In addition, we contacted the editorial base of the Cochrane colorectal cancer group.

Box 1.

Search methods

- Medline (SilverPlatter)

- Embase (Ovid)

- CANCERLIT (Ovid)

- Cochrane controlled trials register (issue 1: 2001)

- MESH terms “colorectal neoplasm,” “colonic neoplasm,” “rectal neoplasm,” “follow-up,” “surveillance”

- Selected articles, review articles, and commentaries

- American Gastroenterology Association (1996-2001)

- American Society for Cancer Research (1996-2001)

- American Society for Colon and Rectal Surgeons (1996-2001)

- United Kingdom National Research Register of ongoing health research (www.doh.gov.uk/research/nrr.htm)

- Computer Retrieval of Information on Scientific Projects (CRISP) database (www-commons.cit.nih.gov/crisp)

- Current Science register of controlled trials (www.controlled-trials.com)

- US cancer-specific register of controlled trials (www.nci.nih.gov/search/clinical_trials/)

- British Journal of Surgery Scientific Surgery Archive of meta-analyses and randomised controlled trials (www.bjs.co.uk/searchSSurgery.asp)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria—We evaluated each trial for inclusion in the meta-analysis on the basis of four criteria: study design (randomised controlled trial), target population (patients with colorectal cancer treated surgically with curative intent), timing of randomisation (at or shortly after surgery), and availability of survival data related to cancer. We included studies that compared intensive follow up strategies with control follow up regimens, as defined by the individual trials. We excluded studies that included patients with advanced disease (Dukes' stage D), when curative resection is generally not possible.

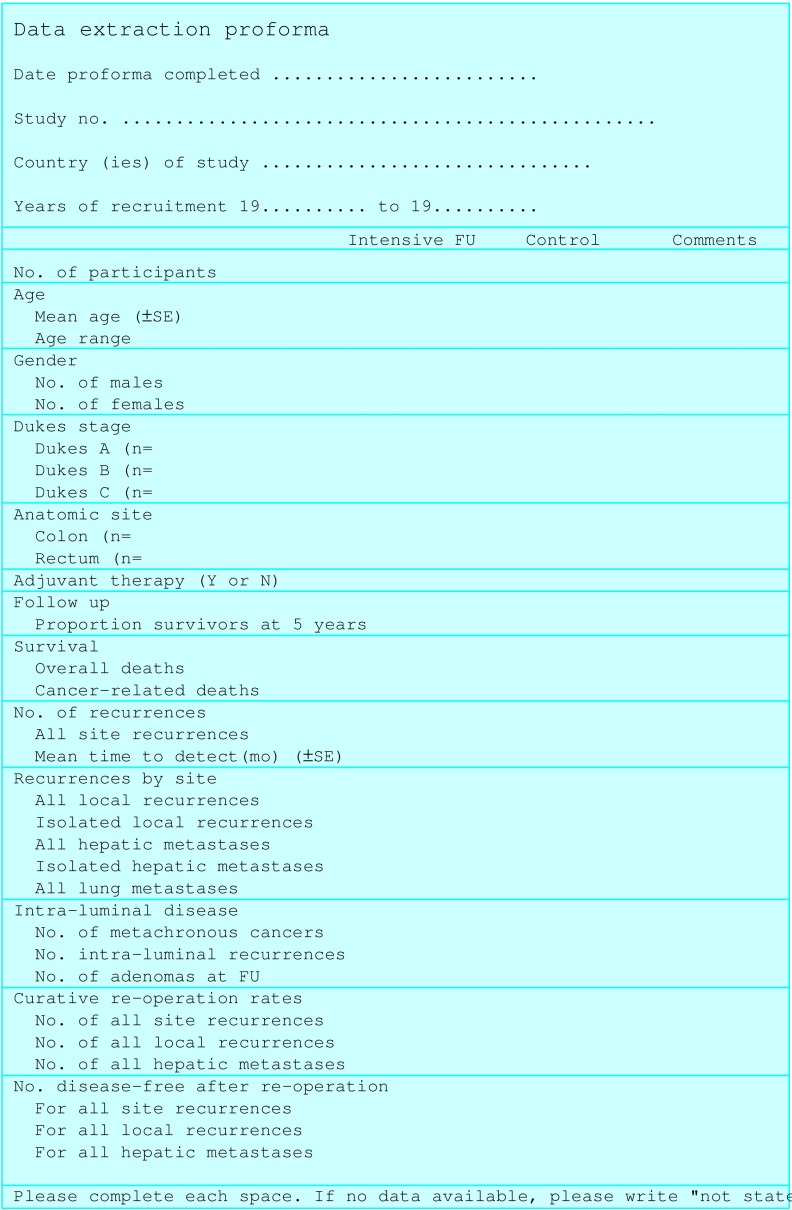

Data extraction—The data were extracted independently by two investigators (AGR and MPS), with disagreements resolved by a third reviewer (STO'D) (fig 1). Data were extracted from the final report for each trial, but preliminary reports were also consulted for additional details on methods.

Figure 1.

Form for data extraction

Outcome measures—The primary outcome was all cause mortality at five years. Secondary outcomes were total number of recurrences, any type of local recurrences, isolated local recurrences, any hepatic metastases, isolated hepatic metastases, lung metastases, intraluminal recurrences, and metachronous (second colorectal primary) cancers.

Assessment of methodological quality—Two of us (AGR and ME) independently assessed adequacy of concealment of patients' allocation to treatment groups, double blinding, and withdrawals.12 Differences in assessments were resolved by consensus.

Subgroup analysis—Different diagnostic tests were used during follow up in different trials. We performed a subgroup analysis based on the a priori hypothesis that the early detection of extramural recurrent disease (namely, local pelvic recurrences and solitary hepatic metastases), with investigations such as computed tomography or frequent measurements of serum carcinoembryonic antigen (at least every three months for two years and then every six months thereafter), or both, was more likely to be effective in improving survival related to cancer than strategies directed only at the detection of intraluminal disease (such as the use of colonoscopy).6

Statistical analysis—We have expressed the main results as combined risk ratios with the fixed effects method and performed tests for heterogeneity.13 We combined data on the duration to first relapse using differences in means.13 We also performed random effects methods for comparison.14 We examined publication bias and related biases in funnel plots and carried out a test of funnel plot asymmetry.15 Sensitivity analyses included assessment of the influence of year of publication, mean ages in trial groups, and Dukes' stages with meta-regression techniques.16 All analyses were performed in Stata version 7.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

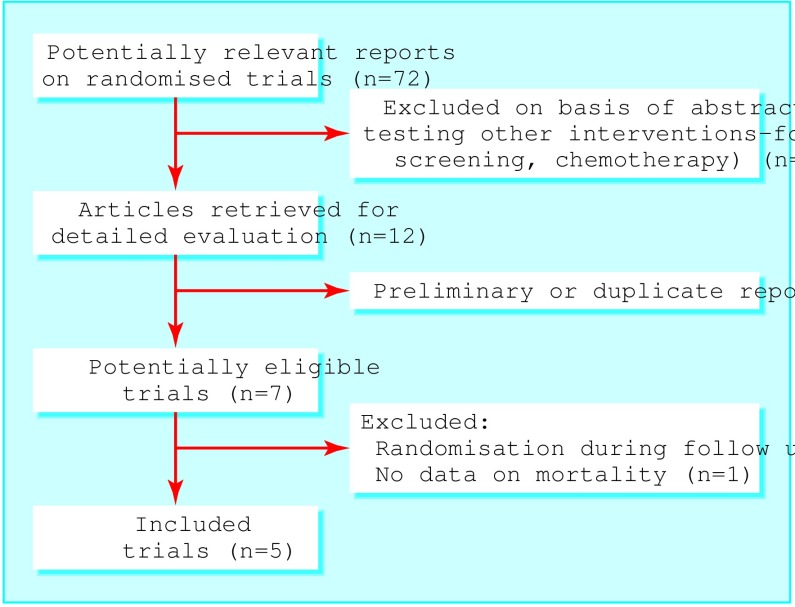

Figure 2 shows the summary profile of the search. We identified seven potentially eligible randomised controlled trials,17–23 five of which met our inclusion criteria.17–21 Two trials reported preliminary results24,25; two also published on related topics.26–28 We also identified six ongoing trials or trials in preparation (box B2). We excluded the study by Northover et al because participants with a raised carcinoembryonic antigen concentration were randomised during follow up rather than at the time of surgery.22 We also excluded the study by Barillari et al because randomisation was limited to less than half the participants, and the main outcome measured was the number of metachronous colorectal tumours detected rather than survival.23

Figure 2.

Summary of systematic review profile

Box 2.

Randomised trials in preparation or ongoing

Study characteristics

The five included trials comprised 1342 participants: 666 assigned to intensive follow up and 676 assigned to control. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the participants enrolled in these trials. In the trial by Makela et al patients in the intensive group were on average six years younger than those in the control group.17 In two other trials there were smaller age differences in the same direction.19,20 There was an imbalance in the sex distribution in one trial.18 All but one study20 included patients with Dukes' stage A disease. The proportion of patients with Dukes' stage C disease was higher in the control group than in the intensive group in two trials,19,21 whereas the opposite was the case in another trial.18 The study periods predated the widespread use of adjuvant chemotherapy, and only one study used adjuvant radiotherapy for rectal cancers.20

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of five randomised trials on follow up after curative resection for colorectal cancer

| Study |

No

of patients

|

Mean

(SD) age

(years)*

|

Men/women

|

Colon/rectum

|

Dukes'

stage

(A/B/C)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensive | Control | Intensive | Control | Intensive | Control | Intensive | Control | Intensive | Control | |||||

| Extramural detection trials | ||||||||||||||

| Makela et al, 199517 | 52 | 54 | 63 (9) | 69 (8) | 25/27 | 27/27 | 36/16 | 39/15 | 13/24/15 | 15/24/15 | ||||

| Ohlsson et al, 199518 | 53 | 54 | 66 (9) | 66 (9) | 20/33 | 31/23 | 34/19 | 3717 | 10/21/22 | 9/26/19 | ||||

| Schoemaker et al, 199819 | 167 | 158 | 67 (9) | 69 (7) | 109/58 | 98/60 | 121/46 | 117/41 | 41/79/47 | 30/74/54 | ||||

| Pietra et al, 199820 | 104 | 103 | 62 (12) | 64 (9) | 56/46 | 53/50 | 73/31 | 66/37 | 0/62/42 | 0/60/43 | ||||

| Intramural detection trial | ||||||||||||||

| Kjeldsen et al, 199721 | 290 | 307 | 64 (6) | 64 (6) | 168/122 | 158/149 | 156/134 | 158/149 | 68/148/74 | 70/145/92 | ||||

SD estimated from stated ranges.

The tests and the frequency of their use varied considerably (table 2).2 No study directly compared specific tests, but in four trials computed tomography and frequent measurements of carcinoembryonic antigen were limited to the intensive arms.17–20 We characterised these trials as the extramural detection group. The Danish study focused heavily on the increased detection of intraluminal disease and thus formed the intramural detection group.21

Table 2.

Detailed characteristics of surveillance programmes used in five randomised trials of intensive versus control follow up of patients after curative resection for colorectal cancer

| Study | Intensive follow up | Control follow up |

|---|---|---|

| Makela et al, 199517 | Seen in clinic 3 monthly for first 2 years, then 6 monthly: physical examination, full blood count, faecal occult blood test, carcinoembryonic antigen levels, and chest x ray. Yearly colonoscopy. Sigmoidoscopy 3 monthly for rectal and sigmoid cancers. Ultrasonography of liver 6 monthly. Computed tomography yearly. All followed up to 5 years | Seen in clinic 3 monthly for first 2 years, then 6 monthly: physical examination, full blood count, faecal occult blood test, carcinoembryonic antigen levels, and chest x ray. Yearly barium enema. Rigid sigmoidoscopy 3 monthly for rectal cancers. All followed up to 5 years |

| Ohlsson et al, 199518 | Seen in clinic 3 monthly for the first 2 years, then 6 monthly: physical examination, rigid proctosigmoidoscopy, liver function tests, carcinoembryonic antigen levels, faecal occult blood test, chest x ray. Colonoscopy at 3, 15, 30, and 60 months, computed tomography after abdominoperineal resection at 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. All followed up to 5 years | No systematic follow up. Patients were instructed to leave samples for faecal occult blood test testing every third month during the first 2 years and then every year. All accounted for to 5 years |

| Schoemaker et al, 199819 | Seen in clinic 3 monthly for first 2 years, then 6 monthly for 5 years; physical examination, full blood count, liver function tests, and Haemoccult II. Yearly chest x ray and computed tomography of liver. Yearly colonoscopy. Carcinoembryonic antigen measurements were performed but not used to trigger further examinations. 94% followed up to 5 years | Seen in clinic 3 monthly for first 2 years, then 6 monthly for 5 years; physical examination, full blood count, liver function tests, carcinoembryonic antigen levels, and Haemoccult II. Carcinoembryonic antigen measurements were performed but not used to trigger further examinations. 95% followed up to 5 years |

| Pietra et al, 199820 | Seen in clinic 3 monthly for first 2 years, then 6 monthly for next 3 years, thereafter yearly; physical examination, ultrasonography of liver, carcinoembryonic antigen levels. Yearly colonoscopy, chest x ray, and computed tomography. All followed up to 5 years | Seen in clinic 6 monthly for first year, then yearly; physical examination, ultrasonography of liver, carcinoembryonic antigen levels. Yearly colonoscopy and chest x ray. All followed up to 5 years |

| Kjeldsen et al, 199721 | Physical examination, digital rectal examination, gynaecological examination, Haemoccult-II, colonoscopy, chest x ray, full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, liver function tests, at 6 monthly in first 3 years, then 12 monthly for next 2 years, then 5 yearly. 79% followed up to 5 years | Physical examination, digital rectal examination, gynaecological examination, Haemoccult-II, colonoscopy, chest x ray, full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, liver function tests, at 5 and 10 years. 73% followed up to 5 years |

Methodological quality of trials

In general methods were poorly reported. Two trials randomised patients by open cards or random number tables.19,20 Randomisation was stratified by site and Dukes' stage in two trials,19–21 but block sizes were not reported. Blinding of clinicians or assessors was not mentioned except for one trial, which reported that computed tomograms were evaluated by an “independent radiologist.”19 Completeness of follow up among survivors was good, with 100% at five years in three studies (table 2).

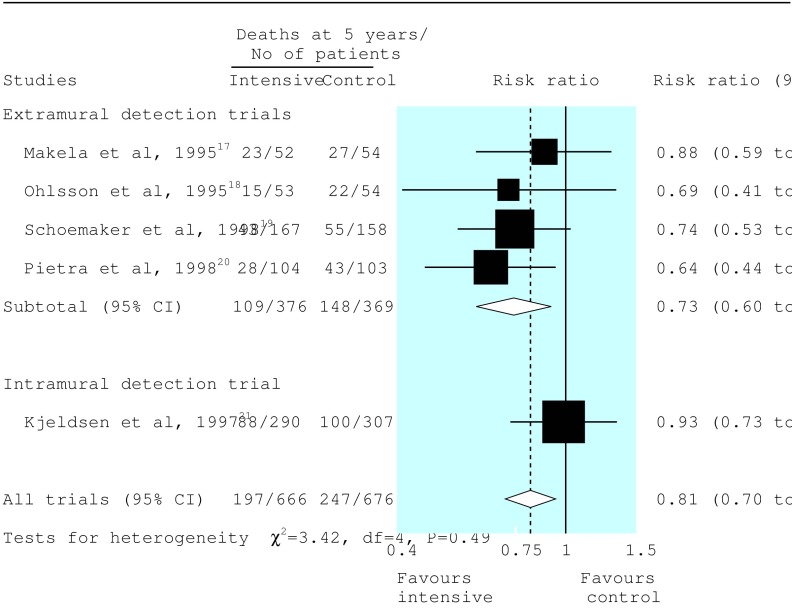

All cause mortality

Data on all cause mortality were available in all studies. Data on mortality related to cancer were available in only two studies.18,21 At five years, 197 of 666 patients (30%) allocated to intensive follow up and 247 of 676 (37%) allocated to control groups had died. By the fixed effects method, the combined risk ratio was 0.81 (95% confidence interval 0.70 to 0.94, P=0.007) in favour of intensive follow up (fig 3). Similar values for risk ratios were estimated by the random effects method (table 3). There was no significant heterogeneity.

Figure 3.

Pooled analysis with summary estimates (fixed effects method) for five year survival: data categorised into detection groups in accordance with a priori hypothesis (see methods)

Table 3.

Details of summary effects for various end points in patients with colorectal cancer according to intensive or control follow up. Figures are numbers (percentage) of patients and risk ratios (95% confidence interval)

| Intensive follow up | Control follow up | Fixed effects* | Random effects† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All cause mortality | ||||

| Makela et al, 199517 | 23/52 (44) | 27/54 (50) | 0.88 (0.59 to 1.33) | |

| Ohlsson et al, 199518 | 15/53 (28) | 22/54 (41) | 0.69 (0.41 to 1.19) | |

| Schoemaker et al, 199819 | 43/167 (26) | 55/158 (35) | 0.74 (0.53 to 1.03) | |

| Pietra et al, 199820 | 28/104 (27) | 43/103 (42) | 0.64 (0.44 to 0.95) | |

| Subgroup‡ | 109/376 (29) | 148/369 (40) | 0.73 (0.60 to 0.89) | 0.74 (0.61 to 0.91) |

| Kjeldsen et al, 199721 | 88/290 (30) | 100/307 (33) | 0.93 (0.73 to 1.18) | |

| Pooled effect§ | 197/666 (30) | 247/676 (27) | 0.81 (0.70 to 0.94) | 0.81 (0.68 to 0.96) |

| All site recurrences | ||||

| Makela et al, 199517 | 22/52 (42) | 21/54 (39) | 1.09 (0.69 to 1.73) | |

| Ohlsson et al, 199518 | 17/53 (32) | 18/54 (33) | 0.96 (0.56 to 1.66) | |

| Schoemaker et al, 199819 | 56/167 (34) | 64/158 (41) | 0.83 (0.62 to 1.10) | |

| Pietra et al, 199820 | 41/104 (39) | 41/103 (40) | 0.99 (0.71 to 1.39) | |

| Subgroup‡ | 136/376 (36) | 144/367 (39) | 0.93 (0.77 to 1.12) | 0.93 (0.77 to 1.12) |

| Kjeldsen et al, 199721 | 76/290 (26) | 80/307 (26) | 1.01 (0.77 to 1.32) | |

| Pooled effect§ | 212/666 (32) | 224/676 (33) | 0.95 (0.82 to 1.11) | 0.95 (0.82 to 1.11) |

| All local recurrences | ||||

| Makela et al, 199517 | 10/52 (19) | 9/54 (17) | 1.15 (0.51 to 2.61) | |

| Ohlsson et al, 199518 | 11/53 (21) | 8/54 (15) | 1.40 (0.61 to 3.21) | |

| Schoemaker et al, 199819 | 7/167 (4) | 11/158 (7) | 0.60 (0.24 to 1.51) | |

| Pietra et al, 199820 | 26/104 (25) | 20/103 (19) | 1.29 (0.77 to 2.16) | |

| Subgroup‡ | 54/376 (14) | 48/367 (13) | 1.12 (0.79 to 1.52) | 1.14 (0.80 to 1.63) |

| Kjeldsen et al, 199721 | 49/290 (17) | 42/307 (14) | 1.24 (0.84 to 1.81) | |

| Pooled effect§ | 103/666 (15) | 90/676 (13) | 1.17 (0.91 to 1.52) | 1.19 (0.91 to 1.54) |

| Isolated local recurrences | ||||

| Makela et al, 199517 | 3/52 (6) | 2/54 (4) | 1.56 (0.27 to 8.95) | |

| Ohlsson et al, 199518 | Not stated | |||

| Schoemaker et al, 199819 | Not stated | |||

| Pietra et al, 199820 | 20/104 (19) | 8/103 (8) | 2.48 (1.14 to 5.37) | |

| Subgroup‡ | 23/156 (15) | 10/157 (6) | 2.30 (1.13 to 4.64) | 2.30 (1.13 to 4.66) |

| Kjeldsen et al, 199721 | 42/290 (14) | 32/307 (10) | 1.39 (0.90 to 2.14) | |

| Pooled effect§ | 65/446 (15) | 42/464 (9) | 1.61 (1.12 to 2.32) | 1.59 (1.10 to 2.30) |

| All hepatic metastases | ||||

| Makela et al, 199517 | 5/52 (10) | 2/54 (4) | 2.60 (0.53 to 12.8) | |

| Ohlsson et al, 199518 | 3/53 (6) | 7/54 (13) | 0.44 (0.12 to 1.60) | |

| Schoemaker et al, 199819 | 20/167 (12) | 23/158 (15) | 0.82 (0.47 to 1.44) | |

| Pietra et al, 199820 | 21/104 (20) | 32/103 (31) | 0.65 (0.40 to 1.05) | |

| Subgroup‡ | 49/376 (13) | 64/367 (17) | 0.75 (0.53 to 1.05) | 0.74 (0.50 to 1.10) |

| Kjeldsen et al, 199721 | 22/290 (8) | 27/307 (9) | 0.86 (0.50 to 1.48) | |

| Pooled effect§ | 71/666 (11) | 91/676 (13) | 0.78 (0.59 to 1.05) | 0.77 (0.58 to 1.03) |

| Isolated hepatic metastases | ||||

| Makela et al, 199517 | 2/52 (4) | 0/54 (0) | 5.19 (0.26 to 105) | |

| Ohlsson et al, 199518 | Not stated | |||

| Schoemaker et al, 199819 | 14/167 (8) | 12/158 (8) | 0.95 (0.47 to 1.92) | |

| Pietra et al, 199820 | 4/104 (4) | 3/103 (3) | 1.32 (0.30 to 5.75) | |

| Subgroup‡ | 20/323 (6) | 15/315 (5) | 1.13 (0.61 to 2.08) | 1.02 (0.51 to 2.02) |

| Kjeldsen et al, 199721 | Not stated | |||

| Pooled effect§ | 20/323 (6) | 15/315 (5) | 1.13 (0.61 to 2.08) | 1.02 (0.51 to 2.02) |

| All lung metastases | ||||

| Makela et al, 199517 | 1/52 (2) | 3/54 (6) | 0.35 (0.04 to 3.22) | |

| Ohlsson et al, 199518 | 3/53 (6) | 2/54 (4) | 1.53 (0.27 to 8.78) | |

| Schoemaker et al, 199819 | 8/167 (5) | 10/158 (6) | 0.76 (0.31 to 1.87) | |

| Pietra et al, 199820 | 0/104 (0) | 1/103 (1) | 0.33 (0.01 to 8.01) | |

| Subgroup‡ | 12/376 (3) | 16/367 (4) | 0.74 (0.36 to 1.51) | 0.75 (0.36 to 1.08) |

| Kjeldsen et al, 199721 | 7/290 (2) | 16/307 (5) | 0.46 (0.19 to 1.11) | |

| Pooled effect§ | 19/666 (3) | 32/676 (5) | 0.61 (0.35 to 1.05) | 0.62 (0.35 to 1.08) |

| Intraluminal recurrences | ||||

| Makela et al, 199517 | 2/52 (4) | 1/54 (2) | 2.08 (0.19 to 22.2) | |

| Ohlsson et al, 199518 | 2/53 (4) | 2/54 (4) | 1.02 (0.15 to 6.97) | |

| Schoemaker et al, 199819 | 3/167 (2) | 5/158 (3) | 0.57 (0.14 to 2.34) | |

| Pietra et al, 199820 | 1/104 (1) | 1/103 (1) | 0.99 (0.06 to 15.6) | |

| Subgroup‡ | 8/376 (2.1) | 9/367 (2.5) | 0.88 (0.34 to 2.23) | 0.87 (0.33 to 2.28) |

| Kjeldsen et al, 199721 | 10/134 (7) ¶ | 6/149 (4) ¶ | 1.85 (0.69 to 4.96) | |

| Pooled effect§ | 18/510 (3.5) | 15/518 (2.8) | 1.25 (0.64 to 2.44) | 1.26 (0.63 to 2.51) |

| Metachronous cancers | ||||

| Makela et al, 199517 | 1/52 (2) | 0/54 (0) | 3.11 (0.13 to 74.7) | |

| Ohlsson et al, 199518 | 0/53 (0) | 1/54 (2) | 0.34 (0.01 to 8.15) | |

| Schoemaker et al, 199819 | 3/167 (2) | 2/158 (1) | 1.42 (0.24.8.38) | |

| Pietra et al, 199820 | 0/104 (0) | 1/103 (1) | 0.33 (0.01 to 8.01) | |

| Subgroup‡ | 4/376 (1.1) | 4/367 (1.1) | 0.98 (0.30 to 3.19) | 1.01 (0.28 to 3.63) |

| Kjeldsen et al, 199721 | 7/290 (2) | 3/307 (1) | 2.47 (0.64 to 9.46) | |

| Pooled effect§ | 11/666 (1.7) | 7/676 (1.0) | 1.50 (0.63 to 3.54) | 1.55 (0.28 to 3.63) |

Mantel and Haenszel.

DerSimonian and Laird.

Extramural detection trials.

Extramural and intramural detection trials.

Data based on rectal cancers only.

The effect on mortality was most pronounced in the four extramural detection trials that used computed tomography and frequent measurements of serum carcinoembryonic antigen (combined risk ratio 0.73, 0.60 to 0.89, P=0.002). The five year mortality in the control groups ranged from 35% to 50%, which translates into an absolute reduction in mortality of 9% to 13% or a number needed to treat (the number of patients needed to prevent one death) of eight to 11. Little effect was seen in the Danish trial, which used only investigations to detect intramural disease (risk ratio 0.93, 0.73 to 1.18, P=0.88).

Recurrences, metastases, and metachronous cancers

There were no differences in rates of recurrence in all sites between the two groups: 212/666 (32%) for intensive versus 224/676 (33%) for control follow up. However, recurrences were detected 8.5 months (95% confidence interval 7.6 to 9.4 months) earlier with intensive follow up (table 4). Subgroup analysis in accordance with the a priori hypothesis revealed no distinct patterns.

Table 4.

Mean (SD) time (months) to first relapse in patients with colorectal cancer according to intensive or control follow up

| Intensive follow up | Control follow up | Differences in means (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Makela et al, 199517 | 10.0 (5.0) | 15.0 (10.0) | −5.00 (−7.99 to −2.01) |

| Ohlsson et al, 199518 | 20.4 (8.0)* | 24.0 (7.0)* | −3.60 (−6.45 to −0.75) |

| Schoemaker et al, 199819 | Not stated | ||

| Pietra et al, 199820 | 10.3 (2.7) | 20.2 (6.1) | −9.90 (−11.19 to −8.61) |

| Subgroup† | −8.32 (−9.41 to −7.23) | ||

| Kjeldsen et al, 199721 | 17.7 (8) § | 26.5 (8.0) § | −8.80 (−10.25 to −7.35) |

| Pooled effect‡ | −8.50 (−9.37 to −7.62) | ||

Estimated from ranges stated.

Extramural detection trials.

Extramural and intramural detection trials.

Estimated from geometric curves.

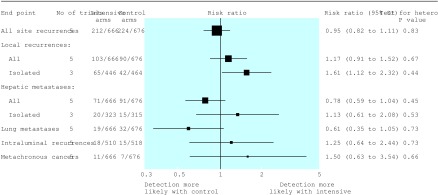

The detection rates for all local recurrences and all hepatic and lung metastases were similar in the two groups (fig 4, table 3). However, on the basis of data from three trials, intensive follow up was associated with a significant increase in detection of isolated local recurrences (15% v 9%: risk ratio 1.61, 1.12 to 2.32, P=0.011). Intensive follow up was also associated with a small non-significant increase in detection of hepatic metastases. Overall, rates of intraluminal recurrence and detection of metachronous cancer were low (3.2% and 1.3%, respectively), and there were no differences between follow up regimens.

Figure 4.

Pooled data and summary risk ratios (fixed effects method) for recurrences, metastases, and metachronous (second colorectal primary) cancers

Sensitivity analysis

We found no influence of year of commencement or publication, mean age, or proportion of Dukes' stage C cancers on any outcome (P>0.10). There was no clear evidence of funnel plot asymmetry in any analysis (P>0.10)

Discussion

The findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials support the view that intensive follow up after curative resection for colorectal cancer improves survival at five years.

Survival benefit

This is the strongest evidence to date to show the beneficial effects of intensive follow up. Individual trials have been inconclusive, probably because of small sample sizes. Our analysis shows that using modern follow up regimens (including computed tomography or frequent measurements of serum carcinoembryonic antigen, or both) there was an absolute reduction in mortality of 9-13%. This improvement compares favourably with, for instance, the 5% benefit observed for adjuvant chemotherapy in Dukes' stage C disease4–29 and is applicable to a wider range of clinical stages of colorectal cancer.30 In addition, the trials we included predated multidisciplinary approaches to the treatment of colorectal cancer, including the wider practice of hepatic resections for metastases, pelvic exenterations for recurrent pelvic disease, and the use of combined therapies for advanced disease. These approaches influence survival,4 and the potential survival benefits from intensive follow up may be even greater than those expressed in this analysis.30

Quality of trials

The quality of included studies should be considered in the interpretation of our findings. None of the trials reported adequate concealment of allocation nor comprehensive blinding of outcome assessment. Only two studies stated that randomisation was stratified for major prognostic factors. Despite these shortcomings, the strength of the present analysis is that it was limited to randomised controlled trials and that it supersedes previous meta-analyses, which were based on predominantly retrospective data.9,10

Mechanisms and future trials

Intensive follow up may improve survival in people with colorectal cancer because of earlier detection and treatment of recurrent disease. It may also be associated with non-specific factors, such as improved psychological wellbeing in patients. The detection rates in this analysis for all local recurrences and hepatic metastases were similar to those quoted in the literature,31–33 but intensive follow up was associated with a reduced time to first relapse and increased detection of isolated local recurrences. This lends support to the former hypothesis. The importance of psychological factors remains unclear for patients with colorectal cancer. The GIVIO study showed that increased psychological support influences survival in patients with breast cancer but not in those with colorectal cancer.34 On the other hand, increased psychological support may influence outcome in particular groups of patients with gastrointestinal cancer.35

Many clinicians favour colonoscopic surveillance (intramural detection) over investigations aimed at the detection of extramural recurrences.6,8 Our findings show that this is not justified. As seen in previous studies36,37 we found that intraluminal recurrences and metachronous cancers were uncommon, irrespective of the intensity of follow up. Therefore, intensive efforts directed at the detection of intraluminal disease are probably of low benefit. We could not address the impact on outcome of intensive follow up through the detection of adenomas, known precursors of malignancy, but increasingly it is recognised that screening for adenomas is most beneficial in those aged 55-65 years.38 For many patients with colorectal cancer this opportunity may have passed.

We could not evaluate the efficacy of individual investigations used in colorectal cancer surveillance. This review represents a pragmatic evaluation of two broad strategies of surveillance. Future large multicentre trials should use a factorial design to allow separation of the effects of different tests performed during follow up. Application of the principles of intensive follow up in this common cancer has potentially important financial and resource implications for health services. Although estimation of the cost per life years gained is beyond the scope of this paper, the present study should serve as a basis for economic modelling in future trials. Finally, while wide variation in follow up persists in clinical practice, we believe that clinical guidelines should be revised.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Pisani P, Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide mortality from 25 cancers in 1990. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:18–29. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990924)83:1<18::aid-ijc5>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abulafi AM, Williams NS. Local recurrence of colorectal cancer: the problem, mechanisms, management and adjuvant therapy. Br J Surg. 1994;81:7–19. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waghorn A, Thompson J, McKee M. Routine surgical follow up: do surgeons agree? BMJ. 1995;311:1344–1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7016.1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. Guidelines for the management of colorectal cancer. London: Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scotland Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Clinical guidelines for colorectal cancer. 1997. www.sugn.ac.uk/guidelines/published/index.html . www.sugn.ac.uk/guidelines/published/index.html (accessed Feb 2002). (accessed Feb 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mella J, Datta SN, Biffin A, Radcliffe AG, Steele RJ, Stamatakis JD. Surgeons' follow-up practice after resection of colorectal cancer. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1997;79:206–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruinvels DJ, Stiggelbout AM, Klaassen MP, Kievit J, Dik J, Habbema F, et al. Follow-up after colorectal cancer: current practice in the Netherlands. Eur J Surg. 1995;161:827–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Virgo KS, Wade TP, Longo WE, Coplin MA, Vernava AM, Johnson FE. Surveillance after curative colon cancer resection: practice patterns of surgical subspecialists. Ann Surg Oncol. 1995;2:472–482. doi: 10.1007/BF02307079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruinvels DJ, Stiggelbout AM, Kievit J, van Houwelingen HC, Habbema JD, van de Velde CJ. Follow-up of patients with colorectal cancer. A meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 1994;219:174–182. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199402000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen M, Chan L, Beart RW, Jr, Vukasin P, Anthone G. Follow-up of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1116–1126. doi: 10.1007/BF02239433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lefebrve A, Clarke M. Identifying randomised trials. In: Egger M, Davey-Smith G, Altman DG, editors. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. London: BMJ Publishing; 2001. pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jüni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323:42–46. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. In: Egger M, Davey-Smith G, Altman DG, editors. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. London: BMJ Publishing; 2001. pp. 285–312. [Google Scholar]

- 14.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson SG, Sharp S. Explaining heterogeneity in meta-analysis: a comparison of methods. Stat Med. 1999;18:2693–2708. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19991030)18:20<2693::aid-sim235>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makela JT, Laitinen SO, Kairaluoma MI. Five-year follow-up after radical surgery for colorectal cancer. Results of a prospective randomized trial. Arch Surg. 1995;130:1062–1067. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430100040009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohlsson B, Breland U, Ekberg H, Graffner H, Tranberg KG. Follow-up after curative surgery for colorectal carcinoma. Randomized comparison with no follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:619–626. doi: 10.1007/BF02054122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoemaker D, Black R, Giles L, Toouli J. Yearly colonoscopy, liver CT, and chest radiography do not influence 5-year survival of colorectal cancer patients. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:7–14. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70626-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pietra N, Sarli L, Costi R, Ouchemi C, Grattarola M, Peracchia A. Role of follow-up in management of local recurrences of colorectal cancer: a prospective, randomized study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1127–1133. doi: 10.1007/BF02239434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kjeldsen BJ, Kronborg O, Fenger C, Jorgensen OD. A prospective randomized study of follow-up after radical surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1997;84:666–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Northover J, Houghton J, Lennon T. CEA to detect recurrence of colon cancer. JAMA. 1994;272:31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barillari P, Ramacciato G, Manetti G, Bovino A, Sammartino P, Stipa V. Surveillance of colorectal cancer: effectiveness of early detection of intraluminal recurrences on prognosis and survival of patients treated for cure. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:388–393. doi: 10.1007/BF02054052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kronborg O, Fenger C, Deichgraber E, Hansen L. Follow-up after radical surgery for colorectal cancer. Design of a randomized study. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1988;149:159–162. doi: 10.3109/00365528809096975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makela J, Laitinen S, Kairaluoma MI. Early results of follow-up after radical resection for colorectal cancer. Preliminary results of a prospective randomized trial. Surg Oncol. 1992;1:157–161. doi: 10.1016/0960-7404(92)90029-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCall JL, Black RB, Rich CA, Harvey JR, Baker RA, Watts JM, et al. The value of serum carcinoembryonic antigen in predicting recurrent disease following curative resection of colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:875–881. doi: 10.1007/BF02052591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kjeldsen BJ, Kronborg O, Fenger C, Jorgensen OD. The pattern of recurrent colorectal cancer in a prospective randomised study and the characteristics of diagnostic tests. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1997;12:329–334. doi: 10.1007/s003840050118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kjeldsen BJ, Thorsen H, Whalley D, Kronborg O. Influence of follow-up on health-related quality of life after radical surgery for colorectal cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:509–515. doi: 10.1080/003655299750026254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dube S, Heyen F, Jenicek M. Adjuvant chemotherapy in colorectal carcinoma: results of a meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:35–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02055679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Renehan AG, O'Dwyer ST. Surveillance after colorectal cancer resection [letter] Lancet. 2000;355:1095–1096. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)72214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malcolm AW, Perencevich NP, Olson RM, Hanley JA, Chaffey JT, Wilson RE. Analysis of recurrence patterns following curative resection for carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1981;152:131–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phillips RK, Hittinger R, Blesovsky L, Fry JS, Fielding LP. Large bowel cancer: surgical pathology and its relationship to survival. Br J Surg. 1984;71:604–610. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800710813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Willett CG, Tepper JE, Cohen AM, Orlow E, Welch CE. Failure patterns following curative resection of colonic carcinoma. Ann Surg. 1984;200:685–690. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198412000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.GIVIO Investigators. Impact of follow-up testing on survival and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients. A multicenter randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1994;271:1587–1592. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510440047031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuchler T, Henne-Bruns D, Rappat S, Graul J, Holst K, Williams JI, et al. Impact of psychotherapeutic support on gastrointestinal cancer patients undergoing surgery: survival results of a trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:322–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lockhart-Mummery HE, Heald RJ. Metachronous cancer of the large intestine. Dis Colon Rectum. 1972;15:261–264. doi: 10.1007/BF02589884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cunliffe WJ, Hasleton PS, Tweedle DE, Schofield PF. Incidence of synchronous and metachronous colorectal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1984;71:941–943. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800711210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atkin WS, Cuzick J, Northover JM, Whynes DK. Prevention of colorectal cancer by once-only sigmoidoscopy. Lancet. 1993;341:736–740. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90499-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]