Abstract

Although understanding the role of the environment is central to language acquisition theory, rarely has this been studied for children’s phonetic development, and receptive and expressive language experiences in the environment are not distinguished. This last distinction may be crucial for child speech production in particular, because production requires coordination of low-level speech-motor planning with high-level linguistic knowledge. In this study, the role of the environment is evaluated in a novel way—by studying phonetic development in a bilingual community undergoing rapid language shift. This sociolinguistic context provides a naturalistic gradient of the amount of children’s exposure to two languages and the ratio of expressive to receptive experiences. A large-scale child language corpus encompassing over 500 hours of naturalistic South Bolivian Quechua and Spanish speech was efficiently annotated for children’s and their caregivers’ bilingual language use. These estimates were correlated with children’s patterns in a series of speech production tasks. The role of the environment varied by outcome: children’s expressive language experience best predicted their performance on a coarticulation-morphology measure, while their receptive experience predicted performance on a lower-level measure of vowel variability. Overall these bilingual exposure effects suggest a pathway for children’s role in language change whereby language shift can result in different learning outcomes within a single speech community. Appropriate ways to model language exposure in development are discussed.*

Keywords: speech production, first language acquisition, field phonetics, morphology, language shift, Quechua, Spanish

1. Introduction.

This study investigates how young children’s bilingual language use and exposure predict their spoken phonetic development. Understanding the role of the language environment is foundational to child language acquisition, and to linguistics more broadly, with implications for language learning, transmission, and change (Cournane 2017, Cristia 2020, Meakins & Wigglesworth 2013, Smith, Durham, & Fortune 2009, Yang et al. 2017). Contemporary language acquisition theories ascribe different importance to the child’s environment: on the one hand, theorists agree that the language-learning environment facilitates and can predict development, but on the other hand, they acknowledge discrepancies between exposure and children’s observed speech-language patterns (Aslin & Newport 2009, Gagliardi & Lidz 2014).

What is the role of the language environment—the language that children are exposed to and learn from—for children’s spoken phonetic development? Rarely has the environment been studied for children’s phonetic outcomes (cf. Cristia 2011, Liu, Kuhl, & Tsao 2003), yet fine-grained measures of acoustic phonetics for children’s speech could unearth subtle differences in environmental experience or rule them out more conclusively. Furthermore, when evaluating the role of the environment in phonetics, is it relevant to distinguish between children’s receptive experience, such as the type or quantity of child-directed speech a child hears, and expressive language experience, such as how often a child talks or the size of their expressive lexicon?

Complete answers to both of these questions require that researchers study children from different language environments—children with different receptive and expressive language experiences. In the past, the role of receptive versus expressive experience was evaluated by studying the influence of lexicon size or degree of phonological awareness on speech development (Caudrelier et al. 2019, DePaolis, Vihman, & Keren-Portnoy 2011, Noiray et al. 2019; but see Mayr, Howells, & Lewis 2015). In this study, the role of the language environment in phonetic development is evaluated in a novel way: by studying speech development in a bilingual community undergoing rapid language shift. Bilingual communities provide a gradient of child language experience because the proportion of each language used varies by child—even in situations of stable language transmission (Gathercole & Thomas 2009). The context of language shift is an even more unique study for the role of the language environment because receptive language abilities (comprehension) outlast expressive language abilities (production) during multigenerational language shift. Thus, in a cross-sectional study in a community undergoing language shift, there is an additional gradient of children’s language experience: the ratio of comprehension to production experience, which may differ by language. For example, children may frequently receive input in the parents’ (minoritized) language spoken in the home—which the children do learn to speak—but express themselves at school or with peers in the majority language, which dominates in the media and many sectors of public life. As a result, the roles of expressive and receptive language can be evaluated within individual children. This distinction is critical because, for child speech production outcomes, expressive experience in particular may be required to coordinate higher-level linguistic planning with low-level speech-motor coordination (DePaolis et al. 2011, Icht & Mama 2015, Zamuner et al. 2018). To acquire adult-like speech patterns, children need to practice not just hearing ambient speech but producing it: accessing the semantic content, decomposing it into words, morphemes, and phonemes, and then organizing their speech articulators to produce these linguistic units in the correct order with appropriate amounts of coarticulatory overlap. Thus, children’s speech production patterns could vary by receptive language experience, like child-directed speech exposure, but they could also vary by expressive language experience, like the size of the expressive lexicon.

With regard to the potential role of the language environment for children’s speech development, this article has two goals. First, it estimates the different bilingual language experiences of children simultaneously acquiring South Bolivian Quechua and Spanish: a highly ecologically valid corpus of daylong audio recordings of children’s language environments, spanning over 500 hours of naturalistic, in-situ child language use and exposure, is efficiently annotated to estimate children’s language dominance. Second, the children’s bilingual language experiences are correlated with a series of speech production patterns, invoking phonetics, phonology, and morphology. Based on these, this article will demonstrate (i) whether individual differences in bilingual language exposure can predict variability in speech-language production in these children and (ii) what type of exposure—receptive versus expressive—best predicts this variability.

2. Background.

2.1. Environmental effects in language development.

The speech and language that children are exposed to in their daily environments have been shown to predict individual differences in development. Speech input from adult caregivers predicts children’s lexical processing speed (Weisleder & Fernald 2013), syntactic complexity (Huttenlocher et al. 2002), expressive and receptive vocabulary sizes (Hoff 2003, Mahr & Edwards 2018), and phonological development (Cristia 2011, Ferjan Ramírez et al. 2019, Garcia-Sierra, Ramírez-Esparza, & Kuhl 2016, Liu et al. 2003). Infants and young children are capable of tracking statistical patterns from their input, such as phoneme or word cooccurrences, and reflecting those patterns during phoneme-discrimination and word-segmentation tasks (Maye, Werker, & Gerken 2002, Pelucchi, Hay, & Saffran 2009), consonant production (Edwards & Beckman 2008, Zamuner 2009), and early, prelexical vocalizations (de Boysson-Bardies & Vihman 1991, Ha et al. 2021).

Nevertheless, the extent of environmental effects upon speech and language development is far from clear. For one thing, there may be insufficient distributional information in children’s ambient environments to derive all meaningful phonological and grammatical categories (i.e. poverty of the stimulus), necessitating other language-learning mechanisms (Swingley 2009, Yang 2004).1 Another possibility is that, even if there were ample information, children may not take in all ambient cues (Lidz & Gagliardi 2015, Pearl & Lidz 2009). Instead, perceptual intake from the ambient language may interact with the child’s current grammar and/or developmental stage. For example, Weisleder and Fernald (2013) found that a relationship between child-directed speech exposure and vocabulary size in two-year-olds was mediated by children’s lexical processing speed. While Weisleder & Fernald 2013 is often cited in support of the idea that the environment is critical for language development, that study can likewise demonstrate how the ability to take language in at certain developmental time periods predicts later speech-language development.

A number of studies on children’s artificial language learning and crosslinguistic development show similar discrepancies between input and output. Despite variable (or absent) patterns in artificial language training data, children still prefer harmonic vowels (Mintz et al. 2018), regularize word order (Culbertson & Newport 2015), and systematize determiner use (Hudson Kam & Newport 2009) during testing, suggesting that young learners bring substantial cognitive biases to the learning process (see Culbertson & Schuler 2019 for an overview). Similarly, many crosslinguistic and cross-cultural surveys of language development find that children’s early speech-language milestones (e.g. the quantity of C-V vocalizations, early word combinations) are immune to exposure, at least before a certain age (Casillas, Brown, & Levinson 2020, Cychosz, Cristia, et al. 2021).

Consequently, there is strong evidence for relationships between language input and development, but there are likewise exceptions where children overregularize or have processing or domain-general biases that override statistical distributions in the ambient language. This study contributes meaningfully to our knowledge of the limitations and mechanisms of environmental influence on speech-language development by studying two topics that remain unexplored in this area. First, there has been almost no work evaluating a possible connection between the language environment and children’s spoken phonetic production and variability (one exception is Foulkes, Docherty, & Watt 1999 and subsequent publications on the development of sociolinguistic variants). Yet the documented relationship between the language environment, especially caregiver input, and speech-language outcomes suggests that such a relationship between the environment and phonetic variation is plausible. Finding a relationship between children’s language exposure and phonetic patterning would suggest a mechanism for language change, especially sound change, stemming not from learning errors, as is sometimes assumed in models of child-driven language change, but instead from language contact (Kerswill & Williams 2000). Additionally, the fine-grained measures of acoustic phonetics are ideally suited to the study of environmental effects on child speech-language outcomes in a way that coarser measures, like the presence of certain grammatical features or lexicon size, are not. For one thing, phonetic patterning is highly malleable. In adults, phonetic drift is one of the first consequences of novel linguistic exposure such as second language learning (Chang 2012), and short-term phonetic change (i.e. accommodation) can occur even within individual conversations (Pardo 2006, Pardo et al. 2012) and among children (Nielsen 2014). Furthermore, in the hierarchy of language contact phenomena, sounds change and even phonologize well before grammatical categories (Thomason 2001, van Coetsem 1988). As such, phonetic measures have the potential to uncover subtler, more recent environmental effects—or rule them out more conclusively.

The second way that this work contributes to our understanding of environmental effects is by contrasting the type of experience. These data come from a community undergoing language shift, meaning that receptive versus expressive experience varies by household, providing a gradient of experience within the population. The language environment is almost always instantiated as input from adult caregivers (receptive experience), which leaves open the possibility that the quantity and quality of children’s own productions (expressive experience) could also influence speech outcomes (DePaolis et al. 2011, Icht & Mama 2015, Zamuner et al. 2018). Children’s own speech production could be a vital component of the language environment because it reflects external stimuli: children’s language production varies by interlocutor (parent, peer) and location (home, school). Finding an effect of children’s own production experience would suggest that some of our models of the language environment are insufficient, at least for speech development. Here again phonetic production is an ideal dependent variable because it requires coordination of higher-level linguistic planning with low-level speech-motor planning. Consequently, if there were ever an effect of expressive experience, it would likely manifest in children’s speech production first.

2.2. Exposure effects in bilingual development.

Children’s bilingual development can depend on the relative amount of exposure received in the two languages. For example, Potter et al. (2019) found that bilingual Spanish-English toddlers, differing in language dominance, failed to recognize words from their nondominant language when those words were embedded in sentences spoken in the dominant language. Similar dominance effects have been documented for children’s vocabulary development (Pearson et al. 1997, Place & Hoff 2016, Thordardottir 2011), while results on phonological processing are more mixed. Studies on the nonword repetition paradigm, for example, sometimes find dominance effects (Sharp & Gathercole 2013), but often do not (Brandeker & Thordardottir 2015, Core, Chaturvedi, & Martinez-Nadramia 2017, Farabolini et al. 2021) (see also Mayr et al. 2015 for phoneme accuracy).

Although evidence for the effects of bilingual dominance, and thus exposure, on children’s phonetic patterning is fairly scarce (though see Bijeljac-Babic et al. 2012), these influences are well documented for adults in situations of language contact (Henriksen et al. 2019, Mooney 2019, Onosson & Stewart 2021, Simonet 2011, Yao & Chang 2016, inter alia). For example, Guion (2003) found that age of Spanish acquisition affected the ability of Quichua-Spanish speakers in highland Ecuador to partition the vowel space across the two languages.

Studies like Mayr et al. 2015 and Sharp & Gathercole 2013 evaluated effects of exposure on phonological development by studying communities with active minoritized language transmission.2 However, language transmission as a lens into effects of exposure on phonological development can also be studied in child heritage language learners and caregivers who are second language speakers. Here there is more evidence for exposure effects on phonetic outcomes: for example, bilingual German-Dutch three- to six-year-olds follow the nonnative acoustic (voice onset time) patterns of their L2 Dutch mothers (Stoehr et al. 2019). Among child heritage language learners, Mayr and Siddika (2018) found successively larger effects of English on Sylheti stop production across generations of English-Sylheti heritage families in the UK. And Khattab (2003) hypothesized that the lack of a voicing lead in the speech of two bilingual Lebanese Arabic-English children (ages five and seven years) was caused by not receiving sufficient early input in the contrast and/or the lack of this cue in the mother’s speech.

Many of the above studies established correlational relationships between bilingual language exposure and learning outcomes. However, outcomes are usually limited to coarse measures of lexical growth and phonological processing. The instantiation of the language environment was similarly limited: for the children, either bilingual language experience was quantified simply as input from caregivers via background questionnaire (e.g. Pearson et al. 1997, Place & Hoff 2011, Thordardottir 2011), or expressive and receptive experiences in the child’s environment were not distinguished (e.g. Gathercole & Thomas 2009, Mayr et al. 2015, Stoehr et al. 2019).

The language environment may predict children’s speech-language outcomes, but to test this, language exposure and use estimates from children’s ambient environments must be quantified in a robust, reliable way from a large, naturalistic sample. The learning outcomes should also be sufficiently fine-grained to capture, or rule out, environmental influences. To that end, the current work estimates children’s language exposure by annotating a large-scale, naturalistic child language corpus to estimate children’s bilingual language exposure. Then, estimates derived from this corpus are compared to children’s patterning on multiple measures of phonetic variability. Crucially, this research is conducted in a bilingual community undergoing language shift, where children’s exposure to and use of their two languages, as well as the ratio of expressive to receptive language experiences, varies considerably by household.

3. Current study.

3.1. The speech community.

Data for this study were collected from children simultaneously acquiring South Bolivian Quechua and Spanish in and around a mid-size town in the south Bolivian department of Chuquisaca. South Bolivian Quechua, henceforth ‘Quechua’, is a Quechua II-C language spoken by more than 1.6 million people in this region of Bolivia and northwest Argentina. (Quechuan languages have traditionally been divided into two primary genealogies: Quechua I and Quechua II, with further subdivisions within Quechua II that correlate with geographic location; Torero 1964.) The phonological inventory includes three phonemic /a, i, u/ vowels and two allophonic [e, o] vowels derived in uvular contexts (Gallagher 2016). Consonant contrasts include voiceless stops, aspirated stops, and ejectives at four places of articulation (/p, t, k, q/) and a three-way alveopalatal, stop-aspirated, stop-ejective distinction /tʃ, tʃh, tʃ’/. Nasals are contrasted along three places of articulation: /m, n, ɲ/; the velar nasal [ŋ] is allophonic. Quechua is also a highly agglutinating language, with over 200 productive nominal and verbal suffixes that encode argument structure and grammatical relations.

In southern Bolivia, Quechua and Spanish have been in intense contact for over four hundred years (Muysken 2019). Today, Spanish tends to dominate the media, educational, and political landscape in the country. The result is that, as in many situations of colonization, there is rampant language shift from Quechua and other Indigenous languages of the country to Spanish. Despite legislation encouraging the implementation of bilingual education in Bolivia, many public schools continue to be conducted primarily in Spanish (Hornberger 2009). Consequently, almost all school-age children who speak Quechua in the home in this region become bilingual in Spanish. Nevertheless, even if the medium in schools is Spanish, some Quechua-speaking teachers use Quechua vocabulary items with their students, and written Quechua words and vignettes are frequently introduced in Spanish-medium textbooks. In the community where I work, I have observed that most peer-to-peer interaction at school is conducted in Spanish (although this cannot be divorced from author positionality; see below). An additional consequence of these sociolinguistic and educational policies is that even though Quechua has an established writing system in Bolivia, children learn to read and write in Spanish, but many do not have the same opportunity in Quechua.

Quechua has a strong spoken presence in southern Bolivia, particularly among adults, but intergenerational transmission within families who—for reasons economic or otherwise—have relocated closer to towns or urban areas is highly variable. Consequently, the morphosyntax and phonology of the Quechua variety studied here are reported to differ significantly from varieties spoken in more rural areas of the department (Camacho Rios 2019). There are no reported statistics of intergenerational Quechua language transmission in this speech community, but on the basis of several summers of fieldwork in the area, I estimate an intergenerational transmission rate of approximately 50% (i.e. 50% of children in the area with Quechua-speaking parents learn to speak Quechua). All children in the current study were bilingual Quechua-Spanish speakers, but the ongoing language shift within the community meant that expressive and receptive language experiences, in addition to bilingual language dominance, varied by child. For example, a child could be Quechua-dominant if they speak predominantly Quechua in their everyday interactions and/or if most of their input in the home is in Quechua.

I have been conducting linguistic fieldwork annually in these communities since 2017, following a linguistic field methods course on South Bolivian (Cochabamba) Quechua at the University of California, Berkeley, in 2016, though this was halted due to COVID-19. During my fieldwork, I took on roles as language researcher and teacher/junior colleague at the primary school where I volunteered. Regarding researcher positionality, I am not a member of this speech community, but a white woman from the United States where, at the time of data collection, I was a Ph.D. student in linguistics. My foreignness was relatively uncommon in the speech community, making it all the more important to obtain naturalistic, unimpeded observations of language behavior (i.e. to avoid the observer’s paradox). The overarching plan of the research program is to document ongoing synchronic and diachronic phonetic variation in these communities via controlled phonetic elicitation and naturalistic observation of child and adult behavior. The naturalistic observational data, in particular, are archived so that the community can benefit from these records of spontaneous, contextualized speech from adults and children with distinct language-learning backgrounds (see §4.2 and §6.4 for detail).

3.2. Measures of phonetic variability.

Two measures of phonetic variability in the children’s speech are studied to evaluate the role of language exposure: (i) within-category vowel dispersion and (ii) V-C coarticulation across different word environments. These phonetic outcomes were chosen for the distinct demands they place on the developing speech apparatus and speech-planning capacities.

Infants establish early auditory-acoustic vowel categories on the basis of their ambient language during the first months of life (Werker & Curtin 2005). Thus, although vowels are some of the first sounds that infants produce (Oller 2000), acoustic-auditory perceptual categories predate vocalizations by several months in development. During the vocal exploration and babbling periods over the first months and years of life, infants compare their foundational acoustic-auditory categories to the acoustic consequences of their vocalic productions, or their auditory feedback, and update their speech-motor plans accordingly. With further vocal production, feedback, and updates, infants and children can then approximate adult-like speech production and variability (Guenther 2006, Moulin-Frier, Nguyen, & Oudeyer 2014, Perkell 2012). The result is that, by early childhood, children have been honing their speech production, especially their vocalic production, for years.

In toddlerhood, the gradient nature of vowel acoustics, compared to the more quantal function that characterizes consonants (Stevens 1989), is relatively forgiving of the high acoustic and articulatory variability in child speech (Lee, Potamianos, & Narayanan 1999): a child who undershoots the articulatory target for /u/ may produce a more centralized or fronted /u/-like variant, but the same degree of undershoot for /l/ would likely result in a complete phonemic substitution like [w] or [j]. Finally, through middle childhood, vocalic development is characterized by a reduction in variability (Lee et al. 1999, Vorperian & Kent 2007), suggesting that speech-motor plans update continuously until at least puberty.

Overall, over the course of development, children get ample early practice refining their vocalic production because vowel-like vocalizations are some of the first sounds for which infants are able to incorporate auditory feedback and update speech-motor plans. Vowels are rarely a source of children’s early phonemic speech errors (Stoel-Gammon & Herrington 1990), and vowel articulation appears to be mostly robust to developmental changes in the vocal tract (Ménard et al. 2007, Turner et al. 2009).

Coarticulation, or the temporal and gestural overlap of two adjacent speech segments, follows a different developmental trajectory. Infants do not begin to produce C-V transitions until the onset of canonical babbling, typically between seven and ten months (Oller et al. 1997). Like vocalic development, auditory feedback—where infants compare their acoustic output to phonemic categories—is likely at play during the development of C-V transitions. However, somatosensory feedback, or tactile consequences of speech production like the position of the tongue and lips, likely also plays a role in coarticulatory development, given the motor demands of shifting articulation from one sound to another.

After the transition from babbling to word production in toddlerhood, the majority of phonological errors are consonantal—like fricative stopping (/s/ > [t]; Chiat 1989), velar fronting (/g/ > [d]; Inkelas & Rose 2007), and cluster reduction (/pl/ > [p]; Vihman 2014)—highlighting the increased motor demands of consonants over vowels. And then, even once typically developing children shed these early phonological errors, they still do not master appropriate amounts of coarticulatory overlap until puberty (Zharkova et al. 2014). Until that time, children exhibit excessive intrasyllabic coarticulation in their speech and are able to distinguish between adjacent segments only as their fine motor control develops, the lexicon grows, and phonological awareness increases (Barbier et al. 2020, Noiray et al. 2019, Popescu & Noiray 2021, Zharkova, Hewlett, & Hardcastle 2011). Thus, children exhibit protracted coarticulatory development until early adolescence when they have acquired both sufficient linguistic and speech-motor experience to approximate adult-like segmental overlap.

In this work, the study of children’s coarticulation differs in one additional way from the study of vowel development. Here, the degree of coarticulation in child speech is measured in two distinct environments: within morphemes and across morpheme boundaries. As such, not only does this coarticulation place more motor demands upon the children than vowels do, but it also places increased linguistic demands as the children must coordinate consonant-vowel transitions and implicate their knowledge of word forms. There is evidence that children as young as two years are capable of distinguishing between word environments in their speech. For example, children (and adults) may coarticulate more across morpheme boundaries in morphologically complex words than within phonologically equivalent, morphologically simple words (Song, Demuth, Shattuck-Hufnagel, & Ménard 2013) and lengthen fricatives in morphologically complex words (e.g. toes) compared to simple words (e.g. nose) (Song, Demuth, Evans, & Shattuck-Hufnagel 2013, but see Mousikou et al. 2021). Consequently, the question is likely not whether children can distinguish between word environments in their speech, but rather how much they can do so and as a function of what kind of language experience, if any.

Comparing vowel production to coarticulation in different word environments should be especially important in order to contrast the roles of expressive and receptive experiences in the children’s language environments. Transitioning between a vowel and consonant is a highly motorized skill, refined over time with practice and increased lingual, labial, and glottal control. So if there is an effect of the ambient environment on children’s coarticulation, it is reasonable to predict that it would stem primarily from children’s own expressive experiences: children who speak more in their daily lives may have more mature coarticulation patterns. By contrast, infants formulate their early acoustic-auditory vowel categories from their ambient language, establishing these categories before they produce even their earliest vowel-like vocalizations. Infants and children then continuously update their vowel articulation throughout development to match the categories. So, we may expect especially strong effects of receptive experience on vowel development. However, this straightforward hypothesis of expressive experiences predicting coarticulation development and receptive experiences predicting vowel development is complicated by its implication that linguistic (morphological) structure must be involved in the study of coarticulation. In that case, it is possible that receptive experience will better predict coarticulation differences by word environment because children may model the degree of their coarticulation in the two environments after the bilingual input they hear in their ambient environments. In other words, we are no longer simply investigating children’s ability to differentiate between adjacent, context-free phonemes during speech production. By implicating morphology, we are probing children’s experience with additional levels of language, especially the lexicon and productive morphology, which develop primarily via receptive experience.

3.3. Hypotheses.

The goal of this article is to evaluate the role of the language-learning environment and of expressive versus receptive language experiences in children’s speech development. To do so, a large-scale, naturalistic child language corpus of bilingual Quechua-Spanish speech was collected. The corpus consists of daylong audio recordings made using small, lightweight recorders that children wore over the course of an entire day. Recordings were annotated for children’s and caregivers’ bilingual language practices. The estimates derived from the annotations, as well as information about the caregivers’ language dominance, were then used to predict variability in the children’s Quechua speech.

Two hypotheses are put forward for this work, one for each phonetic outcome, with differing predictions for expressive and receptive Quechua language experience:

- Hypothesis 1: Children who use more Quechua will have tighter, more compact vowel categories in their Quechua speech.

- 1a. Specifically, children with more receptive Quechua language experience—those who hear more Quechua in their everyday environments and whose caregivers reported themselves to be monolingual in Quechua or Quechua-dominant bilinguals—will have more compact vowel categories in their Quechua speech.

- Hypothesis 2: Children who use more Quechua will distinguish more between word environments in morphologically complex Quechua words.

- 2a. Specifically, children with more expressive Quechua language experience—those who use more Quechua in their everyday environments—will show larger coarticulation differences between word environments in their Quechua speech.

Similar hypotheses are proposed for Spanish-dominant children, who should have more dispersed vowel categories and show smaller coarticulation differences between Quechua word environments than children who use relatively more Quechua. The hypotheses for both phonetic outcomes align with findings on bilingual exposure and dominance effects for children’s language development: for bilingual children, dominance in one language predicts larger vocabularies, faster speech processing, and more accurate consonant production (e.g. Mayr et al. 2015, Place & Hoff 2011, Potter et al. 2019). It is thus reasonable to propose that bilingual dominance could also predict phonetic production outcome measures.

The hypotheses are evaluated in a bilingual community undergoing language shift from the minoritized language, Quechua, to the dominant colonizing language, Spanish. This language shift has created a gradient of child language experience within the community, as bilingual language dominance, as well as receptive and expressive experiences, varies by child.

4. Methods.

4.1. Participants.

Families were recruited through the researcher’s personal contacts in communities surrounding a mid-size town in southern Bolivia. Participants included forty children ages four years to eight years, eleven months (twenty girls, twenty boys). Participants’ families all reported speaking Quechua at home. See Table 1 for further demographic information on the participants.

Table 1.

Demographic information for child participants.

| age | N | age range | gender | N caregivers w/< 6 yrs education |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 5 | 4;0–4;11 | 2 M; 3 F | 2 |

| 5 | 7 | 5;0–5;11 | 2 M; 5 F | 6 |

| 6 | 8 | 6;1–6;8 | 5 M; 3 F | 6 |

| 7 | 14 | 7;1–7;11 | 8 M; 6 F | 9 |

| 8 | 6 | 8;1–8;11 | 3 M; 3 F | 6 |

Most children had normal speech and hearing development, per parental report. The caregivers of three children (two seven-year-olds, one five-year-old) stated that their child was late to begin talking, and another three children’s caregivers did not report late-talker history. These communities are medically underserved, so some language delays or impairments may go unreported. Three children had lost one or more of their front teeth (top or bottom) at the time of recording. (The absence of front teeth could have consequences for acoustics: for example, anterior fricatives.) An attempt was made to complete a hearing test with the children. However, it became clear after trying with a few of the children that false positives were being collected (i.e. children would fail to respond to any of the hearing test stimuli) as the children were nervous about making a mistake. Consequently, it cannot be said with absolute confidence that all children would have passed a standard hearing screening.

Thirty-seven children (92.50%) were regularly attending school at the time of data collection. The other three children were four-year-olds, as pre-kindergarten education is available but not compulsory in the communities. Most children attended school in the morning for an average of four hours (range: 3–5). Three children instead attended school in the afternoon for six hours.

Socioeconomic status (SES), usually implemented as maternal education level in developmental research, is an important predictor of child language acquisition in the United States (Hoff 2003, Pace et al. 2017). However, it is not clear that SES is predictive of language outcomes in all cultural contexts, and it is unknown whether SES predicts language outcomes in Bolivia, in these speech communities, or for children learning Quechua. SES information was nevertheless collected, as it is an important predictor of developmental outcomes in many other cultural contexts.

There were thirty unique caregivers—usually the mother but the grandmother in one family—due to eight children being sibling pairs (no twins) and one three-sibling group. The distribution of maternal education in the sample of unique caregivers was: seventeen caregivers (56.67%) had attended some primary school (less than six years of education), four (13.33%) had completed primary school (six years of education), four (13.33%) had completed the equivalent of middle school (ten years of education), one (3.33%) had completed secondary/high school (thirteen years of education), and three (10%) had not received any formal schooling. One caregiver did not report.

Caregivers’ language practices.

An additional indicator of SES in this community may be the central caregiver’s familiarity with Spanish. This is generally correlated with the mother’s education level in the speech community, since usually only women who have had the opportunity to attend school learn to speak or read Spanish. All caregivers spoke Quechua as a first language, and some additionally spoke Spanish, with varying levels of fluency. To get a description of the caregivers’ Quechua-Spanish bilingual language practices, the researcher walked each primary caregiver through a brief oral survey. For the thirty unique central caregivers, the level of reported Quechua-Spanish bilingualism was: seven (23.33%) were monolingual Quechua speakers, four (13.33%) were Quechua-dominant but spoke/understood some Spanish, eighteen (60%) were bilingual Quechua-Spanish speakers, and one did not report. For the fathers, the level of Quechua-Spanish bilingualism was: one (3.33%) was a monolingual Quechua speaker, four (13.33%) were Quechua-dominant but spoke/understood some Spanish, twenty-two (73.33%) were bilingual Quechua-Spanish speakers, and three did not report.

Families were additionally asked about the language practices of the central caregivers’ parents, as monolingual grandparents may enhance intergenerational minoritized language transmission. Twenty-six caregivers (86.67% of the thirty unique caregivers) reported that both of their parents spoke only Quechua, two (6.66%) reported that their father spoke some Spanish but their mother was a monolingual Quechua speaker, and two (6.66%) reported that both of their parents spoke Spanish and Quechua.

Information on the central caregivers’ code-switching habits was also collected. The central caregiver responded to the following questions on code-switching behaviors:

Do you start sentences in Spanish and finish them in Quechua? That is to say, do you use both languages in the same sentence?

Do you start sentences in Quechua and finish them in Spanish?

Do you use Quechua words when you speak Spanish?

Do you use Spanish words when you speak Quechua?

Responses to these questions are listed in Table 2. The questions were generally not applicable to the seven monolingual caregivers.

Table 2.

Primary caregiver responses to survey questions on bilingual language practice.

| question | yes | no | no response/NA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you start sentences in Spanish and finish them in Quechua? | 17 (56.67%) | 5 (16.67%) | 8 (26.67%) |

| Do you start sentences in Quechua and finish them in Spanish? | 17 (56.67%) | 5 (16.67%) | 8 (26.67%) |

| Do you use Quechua words when you speak Spanish? | 18 (60.00%) | 4 (13.33%) | 8 (26.67%) |

| Do you use Spanish words when you speak Quechua? | 17 (56.67%) | 6 (20.00%) | 7 (23.33%) |

4.2. Procedure.

There were two phases in the study: the daylong recording collection to construct the corpus and the word-elicitation tasks. For both phases, families were visited in their homes or in a central area in the community to explain the experimental procedure.

Daylong recordings.

The daylong recordings reported here come from a larger corpus of nearly 100 infants and children acquiring Quechua and Spanish. The entire corpus is housed in the HomeBank language repository (see Cychosz 2018 for access information). This study reports on forty children from the corpus. To collect the recordings, families were given a small, lightweight recorder: either a 3”×5” Language ENvironment Analysis (LENA) Digital Language Processor (Greenwood et al. 2011), or a 2”×5” Zoom H1n Handy recorder. To explain the recording procedure to participants, the researcher demonstrated how to turn the recorder on and off and how to pause the recording, among other functions. To obtain fully informed consent for the daylong recording, the researcher explained the radius that the recorder could capture and that families had the option to delete the recording after completing it. Families were encouraged to ask questions, practice using the recorder, and make sample recordings to become familiar with the technology. Per university IRB specifications, families could pause the recording whenever they wanted, and many families elected to do so at various points. Additionally, families were instructed to either remove or pause the recorder when the child attended school and when the child was sleeping. In practice, some families forgot to turn the recorder off when the child napped, so prior to annotation an additional preprocessing step was taken to identify portions of the recording where the child might be sleeping.

Children were not required to wear the recorder to school because the children’s schools were led almost entirely in Spanish, and the children spoke Spanish at school (I volunteer at a primary school in the community where I have observed many school language practices). Since all of the school-age children spent a similar amount of time at school (see §4.1), there was no need to sample school language use. Also, there was no reliable way to obtain informed consent from everyone who might appear on the recording during the school day.

After the daylong recording procedure had been explained, families were given a small cotton t-shirt. Each t-shirt had a cotton pocket sewed to the front with a Velcro or snap-button flap to close the pocket and hold the recorder inside (Figure 1). Families were told to record for at least twelve hours, at which time they could stop. These twelve hours could be nonconsecutive, since families were allowed to pause the recording and children did not wear the recorder to school.

Figure 1.

Daylong recording collection materials.3

Most families completed three daylong recordings. Families were visited on three different days. At each visit, the researcher checked that the families had completed the recording and exchanged the previous shirt and recorder for a clean shirt and empty recorder. In all, thirty-nine children (97.50%) successfully completed at least three daylong recordings, while one child completed only one recording because he left on a trip after the first day.

The daylong recordings were used to estimate each child’s dual language exposure. Children’s language exposure was estimated in this way instead of via written background questionnaire for several reasons. First, literacy levels and familiarity with behavioral research varied greatly between participant families, including in ways that created confounds with the parameters of interest (monolingual and Quechua-dominant mothers had less opportunity to attend school). Carrying out an extensive written questionnaire, such as the ‘bilingual background interview’ (Marchman & Martínez-Sussmann 2002), was thus not feasible. Second, Quechua is often undervalued and frequently stigmatized in Bolivia, so there was concern that social desirability biases could cause parents to underreport their children’s Quechua language exposure. Nevertheless, it is the case that one or even many daylong recordings collected at a single timepoint cannot capture the complexities of a child’s language exposure, a point to which we returned in the discussion (§6).

Word-elicitation task stimuli.

Following the daylong recording procedure, each child completed a series of picture-prompted speech production tasks: (i) Quechua real-word repetition, including a morphological extension component, (ii) Quechua nonword repetition, (iii) Spanish nonword repetition, and (iv) additional Quechua real-word repetition with morphological extension. Nonword repetition results are not discussed in this article.

Although the children were bilingual Quechua-Spanish speakers, their phonetic development was measured in Quechua, not Spanish, for three reasons. First, Quechua’s agglutinating structure permitted easier manipulation of word environment. Coarticulatory differences by word environment could also be studied in a more fusional language like Spanish, but it was anticipated that there would be more variability in coarticulatory differences by word environment in Quechua. Additionally, Quechua is a much more morphologically rich and productive language than Spanish, providing a variety of suffixes with different phonological structures for creating the stimuli. Finally, there was interest in evaluating the effect of vowel frequency on vowel variability, and Quechua, with three phonemic and two less-frequent allophonic vowels, permitted that manipulation. For reasons of time, it would not have been feasible to carry out these tasks a second time in Spanish.

The real-word repetition tasks contained fifty-six high-frequency Quechua nouns (plus six training trials) familiar to children learning Spanish and Quechua. Children’s recognition of the test items was confirmed via a pre-test. Female caregivers likewise confirmed that children as young as three years of age would recognize the items. An adult female bilingual Quechua-Spanish speaker recorded the real words for the experimental stimuli, and these recordings were digitized at a sampling frequency of 44.1 kHz using a portable Zoom H1n Handy recorder. Stimuli were normed for amplitude between words but not for duration, since some words had ejectives, fricatives, and so forth that are longer. The real-word picture stimuli were color photographs of the objects.

Children in these communities can have limited exposure to technology. Consequently, rather than photos presented on a screen, picture stimuli were presented on individual pages clipped into an 11”×12.4” plastic binder. For this reason, instead of randomizing the word lists between participants, two different randomized lists were created and were counterbalanced between participants. Repetitions of the same stimulus were always separated by at least two different stimuli and were presented with a novel photo of the item each time.

A subset of the lexical stimuli are analyzed in this article: twenty-four items for the vowel analysis and forty-six for coarticulation (see Tables A1–A3 in the appendix for stimuli lists). The stimuli for the coarticulation analysis were chosen because they contained the sequence [ap] or [am] either within a morpheme (e.g. papa ‘potato’) or crossing a morpheme boundary (e.g. thapa-pi ‘prairie-loc’) in the syllable carrying primary stress. (Quechua is generally an open-syllable language, so nearly all VC syllables cross syllable boundaries.) The only exception to the stress criterion was the word hamˈpiri ‘healer’ and its inflection hampiˈri-pi ‘healer-loc’, where the [am] sequence did not co-incide with primary stress. This item was included to ensure sufficient items for the within-morpheme condition while still adhering to the criteria of high frequency, easily recognizable for children, and so forth.

The VC sequences [ap] and [am] were chosen for examining coarticulatory effects for several important reasons. First, Quechua nominal case-marking suffixes are consonant-initial (e.g. -q ‘genitive’, -manta ‘ablative’), so it is not possible to elicit a CV sequence that crosses a noun–case marker boundary. Also, coarticulatory measures are highly dependent upon segmentation decisions. The acoustic delimitation between vowels and voiceless stops/vowels and nasals is relatively obvious and not subjective.4

The two suffixes elicited for the coarticulation analysis, the locative -pi and the allative -man (pronounced [maŋ]), were chosen because inflected nouns are easier to represent in photos than derived word forms are (e.g. puñu-y ‘to sleep’ → puñu-chi-y ‘to make (one) sleep’). Also, nouns are grammatical in Quechua with just one suffix, while conjugated verbs sometimes require multiple suffixes (as seen in the previous example). Finally, absent a large, fully transcribed corpus of child-directed Quechua speech, which is not available, it is reasonable to assume that the locative -pi and allative -man on high-frequency nouns would be relatively frequent in the children’s input. Thirty-five unique items were used to elicit the across-morpheme-boundary condition, and eleven unique items were used in the within-boundary condition. This represents more distinct lexical items than most previous studies of morphological effects on speech production in children or adults have used (Lee-Kim, Davidson, & Hwang 2013, Song, Demuth, Shattuck-Hufnagel, & Ménard 2013).

The stimuli used for the vowel analysis were selected because the target vowels /a, i, u/ fell in stressed and, where possible, word-medial position. Taking vowels from word-medial position avoids the effect of word-final devoicing and loss of spectral energy. Additionally, words were selected to avoid flanking consonants that would exert the strongest coarticulatory effects on the vowels (glides and laterals). Finally, note that the allophonic mid vowels [e] and [o] are derived only in uvular environments (see Gallagher 2016 for further detail), so the flanking consonant in the words used to elicit [e] and [o] was almost always uvular.

Coarticulation between vowels and neighboring sounds is a real concern for a study of vowel variability. However, recall that all of the vowel stimuli came from the same words (thus the vowel’s environment and coarticulatory influences should be relatively constant between children). Vowels were elicited in real words instead of nonce words because the objective was to elicit quechua vowels, not Spanish. But since the two languages’ vowel categories completely overlap (both languages have five vowels [a, e, i, o, u], though the mid vowels are allophonic in Quechua), it could be difficult to determine which language system the participants were using. If the task was to repeat context-neutral vowels (e.g. ‘say [æ] like cat’), there was concern that the children would default to Spanish vowels instead of Quechua. This was especially relevant since many of the children were tested in an environment where they are used to speaking Spanish (school) by someone who looks more likely to be a Spanish speaker than a Quechua speaker (the white researcher). Because the vowels were elicited within Quechua words, there was little doubt that the children were producing Quechua vowels, not Spanish.

Word-elicitation task procedure.

For the word-elicitation tasks, participants sat side by side with the experimenter. The prerecorded audio stimuli were played from an iTunes playlist run on an iPhone 6. Participants wore AKG K240 binaural studio headphones; the experimenter wore Apple earpods to follow along with the experiment. Both sets of headphones were connected to the iPhone with a Belkin headphone splitter. For each trial, the participant first heard the audio stimulus (a bare noun) while presented with the accompanying photo in the binder. The participant was asked to simply repeat the bare noun. Then, the inflected form of the target word was elicited (with locative -pi in the first real-word repetition task and the allative -man in the second) by placing a large plastic toy insect on top of the visual stimulus and asking the child ‘Where is the bug?’. The child would then respond with the inflected word form (e.g. llama-pi (llama-loc) ‘on the llama’).

The participants repeated after a model speaker, instead of spontaneously naming the item in the photo, because in a previous version of this word-elicitation task, with different children, it was found that the youngest children frequently became too nervous and hesitant to follow the task when not auditorily prompted with the word. Elicited imitation paired with a visual stimulus is also a common elicitation technique in child speech research (Erskine, Munson, & Edwards 2020, Song, Demuth, Shattuck-Hufnagel, & Ménard 2013).

There were two exceptions to participant inclusion. First, four children completed a different, pilot version of the morphological extension task; consequently, only vowel data from these children are analyzed. Second, in pilot testing, four-year-olds could not reliably complete the morphological extension task (not because they showed evidence of morphological unproductivity; they just had a harder time understanding the task). So the five four-year-olds contribute only vowel data, not coarticulation data, to the analysis.

Altogether, the word-elicitation tasks took approximately thirty to forty minutes per child. For the daylong recordings and word-elicitation tasks, each family was compensated with a small monetary sum. The families also usually kept the t-shirt, and the children could pick items from a bag of toys.

4.3. Child language corpus analysis.

Daylong recording selection.

To get the best estimate of each child’s language environment, the research team annotated the longest duration recording for each child. The average duration of the daylong recordings used for bilingual language estimation was 12.12 hours (range 7.63–16 hours), with no notable durational outliers within any age group (Table 3). Supplement 1 in the online supplementary materials includes more detailed information about corpus construction and annotation.5

Table 3.

Daylong audio recording information by age group.

| age | avg recording duration (hrs) | range (hrs) | avg # of potential 30 s clips to annotate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 12.17 | 8.77–16 | 1,400 |

| 5 | 12.29 | 8.92–16 | 1,454 |

| 6 | 12.12 | 7.63–16 | 1,369 |

| 7 | 12.13 | 9.48–16 | 1,469 |

| 8 | 11.00 | 11.24–13.75 | 1,274 |

Processing daylong recordings.

Researchers who collect daylong recordings rarely transcribe the recordings in their entirety, instead transcribing consciously sampled portions. Some laboratories have, for example, selected audio samples from different parts of the day within the recording (e.g. Weisleder & Fernald 2013) or samples containing large numbers of words spoken by adults (e.g. Ferjan Ramírez et al. 2019). This study instead employs a general sampling-with-replacement technique to selectively annotate portions of each daylong recording. This method has been shown to result in the most efficient, representative estimation of bilingual language exposure from daylong audio recordings (Cychosz, Villanueva, & Weisleder 2021). The entire recording selection and annotation workflow used is outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Audio clip generation, selection, and annotation workflow.

First, the recordings were chopped into thirty-second clips, as the random sampling annotation technique was validated on thirty-second clips (Cychosz, Villanueva, & Weisleder 2021). Clips were annotated using a custom graphical user interface (GUI) application that randomly selected a clip, with replacement, from a given participant’s clips.6 The researcher would listen to the drawn clip and categorize the speaker(s) and language(s) heard. Research personnel had the option to repeat the clip as many times as they would like. Clips where the child was sleeping, the researcher was present, or there was 0% reported vocal activity (determined by running a standard vocal activity detector; Usoltsev 2015) were drawn but not annotated. For each clip, annotators made the following decisions.

Language?: Quechua, Spanish, mixed, no speech, personal identifying information, researcher present, or unsure

Speaker?: target child, target child & adult, other child, other child & adult, adult, or unsure

Media present?: yes or no

If there was no speech in the clip, annotators selected ‘no speech’. If only Spanish was spoken (regardless of quantity), the researcher marked ‘Spanish’. Similarly, the researcher marked ‘Quechua’ for monolingual Quechua clips. If the researcher heard both Quechua and Spanish in the clip—whether code-switching within a sentence or two different conversations—they marked ‘mixed’. For speaker annotation, the ‘target child’ was the child wearing the recorder and ‘other child’ was anyone whose voice sounded prepubescent. Personnel were instructed to annotate ‘target child and adult’ if a clip contained the target child, another child, and an adult. See https://github.com/megseekosh/Categorize_app_v2/blob/master/FAQs_bilingual.MD for further details on annotation decisions, including a list of frequently asked questions used to standardize annotation between research personnel.

When the language or speaker in a clip was unclear (e.g. a caregiver singing nonce words, other nonlanguage vocalizations), research personnel could select ‘unsure’. Language and speaker were coded separately, so annotators could still code for speaker or language even if the other category was unclear. The ‘unsure’ annotation was most often used for clips where a conversation was taking place in the background of the recording that made it difficult to determine the language and/or speaker. The team of annotators considered the possibility that it may be difficult to ascertain the speaker or language in some clips because those clips are noisier and contain multiple interlocutors. These noisy clips, with multiple interlocutors, might be more likely to contain mixed speech, so disregarding them could lead the team to inadvertently disregard clips of a certain category (i.e. mixed speech). In practice, however, the ‘unsure’ clips almost always contained background speech without a discernible speaker or language, so the team felt confident in excluding ‘unsure’ clips from further analysis.

The choice for media was binary—’present’ or ‘absent’—because (i) it was often difficult to determine if the media in the recording was radio or TV and (ii) almost all of the media was in Spanish, making it irrelevant to mark the language. In other words, when media was present, it was in Spanish.

As annotators drew and listened to the thirty-second clips, they were simultaneously running a Jupyter notebook to mark progress toward annotation. The notebook recorded the proportion of Quechua, Spanish, and mixed clips to total clips for each child. Human annotation was cut off when two criteria were met. First, the proportion and variance (variance measured over a moving window of sixty language-proportion estimates) between language categories had to asymptote (that is, approach but not touch a horizontal line, exemplified in Figures 3 and 4). Second, fifty language clips from each child had to be annotated (language clips include those annotated as Quechua, Spanish, or mixed, but not as ‘unsure’ or ‘no speech’). The fifty-clip criterion was included as an additional precautionary measure to ensure sufficient transcription even if stability between language-category proportion and variance was reached. Given these predetermined criteria, the team was more confident that their annotations were accurately reflecting the child’s language environment.

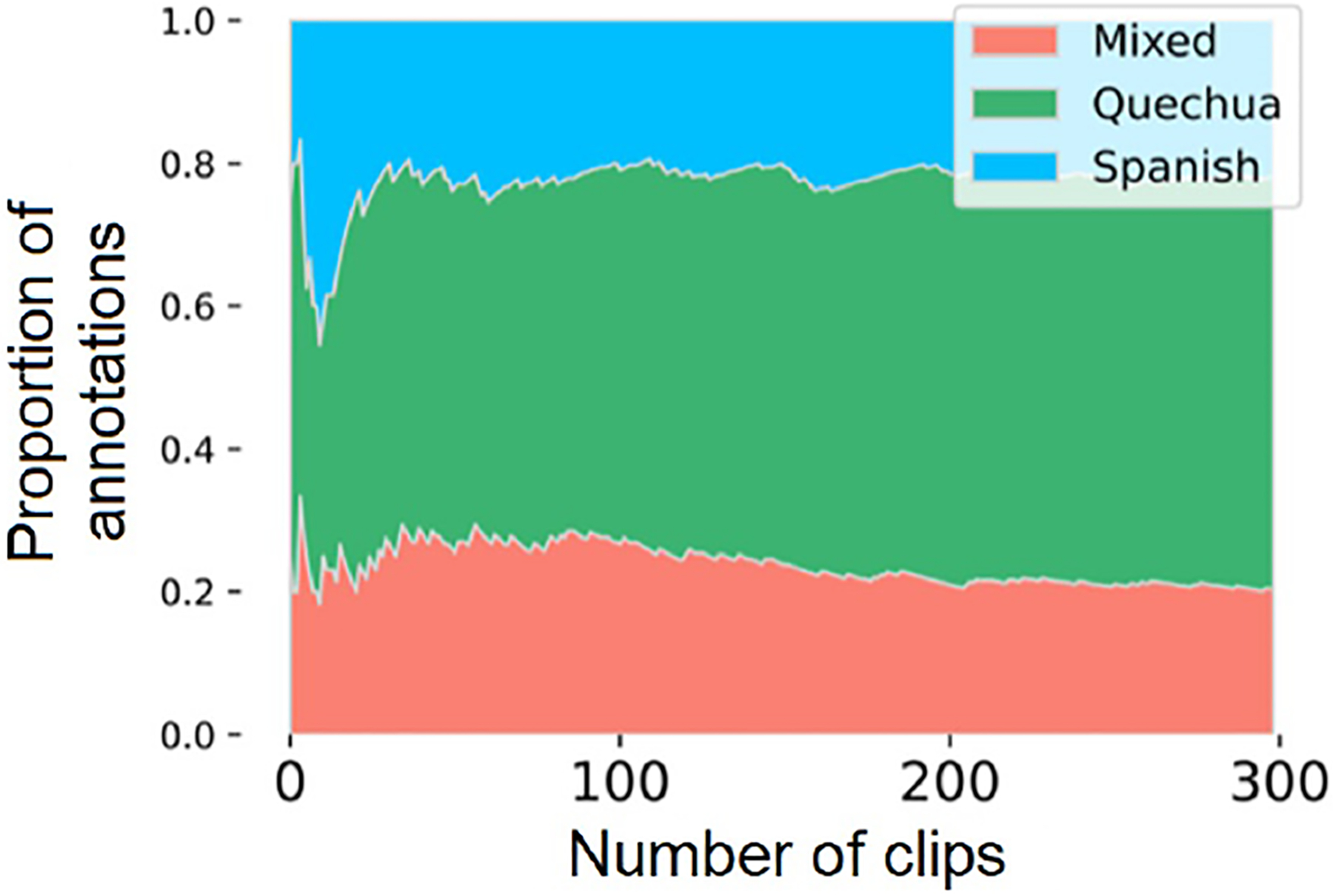

Figure 3.

Example area plot of language proportions by number of clips annotated. Area plots were used to track progress toward language proportion stability during daylong recording annotation.

Figure 4.

Example plot of Spanish language proportion variance by number of clips annotated. Variance was computed over a moving window of sixty clips. This plot was used to track progress toward variance stability during daylong recording annotation.

The research team was able to make stable estimates of each child’s bilingual language exposure by listening to and annotating an average of 185.3 thirty-second clips from a given recording (SD = 69.72, range = 84–385), or an average of 92.66 minutes total from each recording.7 Given that recording length varied (Table 3), the annotated clips made up an average of 13.13% of each recording (SD = 5.47, range = 4.38–29.90%). Thus, the number of clips annotated for a given child varied as a function of the unpredictability of language categories in the child’s environment. But the criterion for variance between the annotated categories was the same for all children. Overall, this procedure resulted in the annotation of a total of 3,706.5 minutes, or 61.78 hours, across the forty children.

Research personnel.

Three undergraduate student research assistants and the lead researcher (the author) annotated the daylong recordings. All research assistants were fluent Spanish speakers participating in a linguistics research training program. The annotation personnel underwent a stringent training procedure prior to and during annotation (see Supplement 1 for details).

Interrater reliability scores between the lead researcher and all personnel members were calculated to ensure fidelity to the coding scheme. Seventy-two clips were randomly selected from one participant’s recording.8 Each personnel member then annotated the clips according to the established annotation procedure. The interrater reliability between personnel members (lead researcher and three assistants) and the remaining team was as follows: 94.44% agreement (lead researcher), 93.06%, 94.44%, and 98.61% agreement for each of the three assistants (Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.87 for the entire team).

Intrarater reliability was also collected for all annotation personnel: the lead researcher had 99.17% intrarater agreement (Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.99), research assistant 1 had 97.62% agreement (Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.93), research assistant 2 had 99.29% (Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.93), and research assistant 3 had 100% (Krippendorff’s alpha = 1.0). In all, these inter- and intrarater agreement scores were satisfactory to conclude that raters were calibrated and annotating uniformly.

4.4. Acoustic analysis.

Participants’ audio files from the word-elicitation tasks were first manually aligned to the word level in Praat (Boersma & Weenink 2020) and to the phone level using a Quechua forced aligner trained on the participants’ data (McAuliffe et al. 2017). The phone-level alignment was hand-corrected by one of two trained phoneticians. Alignment was conducted auditorily and by reviewing the acoustic waveform and broadband spectrogram. These acoustic analyses are sensitive to alignment decisions, so a number of parameters were set prior to alignment. Word-initial plosive, affricate, and ejective onset corresponded to burst onset. Onset of periodicity and formant structure in the waveform and spectrogram marked vowel onset. Nasals were identified by anti-formants and dampened amplitude. Glide-vowel sequences were delimited visually, or, when this was not possible, half of the vowel-glide sequence was attributed to the vowel and half to the glide. There is some variability in the realization of mid vowels in Quechua speakers; vowels were transcribed phonemically.

Interrater agreement between the phoneticians aligning the files was evaluated. Both phoneticians aligned two randomly selected recordings, one from a child aged five years, nine months and another from a child aged seven years, four months. The difference between the aligners’ average consonant duration was 4 ms, and vowel duration was 2 ms for the first child. Pearson correlations between the aligners for this child were significant for consonants: r = 0.86, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.83, 0.89], and for vowels: r = 0.94, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.93, 0.96]. For the second child, the difference between aligners’ average consonant duration was 2 ms, and vowel duration was 2 ms. Pearson correlations between the aligners were significant for consonants: r = 0.98, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.97, 0.98] and for vowels: r = 0.95, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.94, 0.96], suggesting fidelity to the alignment protocol.

Coarticulation analysis.

The high frequencies and breathiness of child speech can make it difficult to implement some traditional acoustic measures of coarticulation such as peak equivalent rectangular bandwidth (ERBN) (Reidy et al. 2017), center of gravity, or formant transitions and/or spectral peaks (Lehiste & Shockey 1972, Öhman 1966). To circumvent these issues, this study measures coarticulation as the spectral distance between two phones, a technique that has been validated for children’s speech and a variety of consonants (Cychosz et al. 2019, Gerosa et al. 2006). For this measure, a custom Python script running librosa functions (McFee et al. 2015) (available in the project’s Github repository) computed the mel-frequency log spectra over the middle third of two adjacent phones (e.g. [a] and [p]) that fell within morpheme boundaries (e.g. api ‘corn/citrus drink’) and across morpheme boundaries (e.g. llama-pi ‘llama-loc’). Then, the average spectrum for each phone was computed, and the Euclidean distance between those averages was measured. Finally, to compute the coarticulatory differences by word environment, the difference in coarticulation between the across-morpheme environment and the within-morpheme environment was calculated. This computed difference is a measure of how different the degree of coarticulation is, so a larger difference indicates that a speaker differentiates more between the two word environments.

Vowel analysis.

Because vowel formant frequencies can be difficult to track reliably in children’s speech, a triple formant tracker running three trackers (inverse filter-control (Watanabe 2001), Entropic Signal Processing System’s (ESPS) ‘covariance’, and ESPS’s ‘autocorrelation’) was built.9 The tracker produced three measurements (one from each tracker) for the first two formant frequencies (F1 and F2) at the vowel midpoint. The median formant measurement was then used in the analysis. In this way, anomalous measurements from any single tracker did not have an outsize influence. Formant frequencies were Lobanov-normalized to control for between-child anatomical differences (Lobanov 1971). Additional steps taken to clean and standardize the formant measures are outlined in Supplement 2.

Vowel dispersion was implemented as the average Euclidean distance in F2/F1 space from the vowel category mean, resulting in a single coefficient per vowel category.10 This category dispersion coefficient reflects both the mean value of each vowel category and its variability along the F1 and F2 dimensions. A larger dispersion coefficient indicates that the acoustic vowel category is more disperse.

5. Results.

The first section of the results (§5.1) presents descriptive analyses of the proportion of Quechua, Spanish, and mixed Quechua-Spanish speech clips (henceforth ‘mixed’) in the daylong recordings. These analyses quantify the variation in bilingual language exposure between children, as well as how this exposure varies by child age and the primary caregiver’s language dominance. The second section (§5.2) examines how individual differences in language exposure predict the phonetic outcomes measured. It is expected that children with more Quechua-dominant caregivers—who hear more Quechua—will have tighter vowel categories (a smaller vowel dispersion coefficient). Likewise, it is expected that children who use more Quechua will be more likely to distinguish via coarticulation between word environments in their speech production.

All analyses were conducted in the RStudio computing environment (version: 1.2.5033; RStudio Team 2020). Data visualizations were created with ggplot2 (Wickham 2016). Modeling was conducted using the lme4 (Bates et al. 2015) and lmerTest (Kuznetsova, Brockhoff, & Christensen 2017) packages, and summaries were presented with Stargazer (Hlavac 2018). The significance of potential model parameters was determined using a combination of log-likelihood comparisons between models, Akaike information criterion (AIC) estimations, and p-values procured from model summaries. Scripts to replicate these results are available in the project’s Github repository.

5.1. Descriptive analyses of bilingual language exposure.

Figure 5 shows the distribution of the language categories Quechua, Spanish, and mixed, as well as clips annotated ‘unsure’ or ‘no speech’, by the central caregiver’s language profile (a table listing the number of clips in each language by maternal profile is included in Supplement 3). Henceforth the central caregiver is referred to as the mother, though one of the caregivers was the child’s grandmother. The maternal language profile was determined from the brief background survey completed during testing. Three maternal language profiles were compared: mothers who were monolingual Quechua speakers (n = 10), Quechua-dominant speakers (n = 6), and bilingual Quechua-Spanish speakers (n = 23). One family did not report the mother’s bilingual language profile. Unsurprisingly, a larger number of monolingual Quechua clips were found in the recordings of the children with monolingual mothers (n = 381, 18.07%) than of the children with Quechua-dominant mothers (n = 163, 11.71%) or bilingual Quechua-Spanish mothers (n = 353, 9.29%). Children with monolingual mothers are exposed to more Quechua than children with Quechua-dominant or bilingual mothers. The percentage of Spanish clips did not vary greatly by language profile. See appendix Table A4 and Figure A1 for a distribution of clip annotation categories and percentages for each individual child.11

Figure 5.

Proportion of language categories, by maternal language profile. Numbers on barplot reflect percentages of each category. Note: one family did not report maternal language profile.

Figure 6 presents the distribution of clip annotations by child age (four to eight years; corresponding table is given in Supplement 3). Given the ongoing language shift in this community, we might anticipate more Spanish or mixed speech among the youngest children. Instead, the seven- and eight-year-olds have the largest percentage of Spanish clips, suggesting that factors other than age may predict the proportion of each language in the input. The data also suggest that language environments become more verbal as children age, since far fewer clips in the seven- and eight-year-old groups contained no speech.

Figure 6.

Proportion of language categories, by child age (years). Numbers on barplot reflect percentages of each category.

While there are too few children within each age group to reliably evaluate the effects of maternal language profile by age, a larger proportion of the seven-year-old group had bilingual Quechua-Spanish mothers (Table 4): nine of thirteen seven-year-olds had bilingual mothers compared to three of seven five-year-olds, for example. Nevertheless, maternal language profile cannot entirely explain the differences between age groups: four of six eight-year-olds had monolingual mothers, but a large percentage of their clips (39.3%) were still Spanish.

Table 4.

Maternal language profiles by child age (in years).

| age | monolingual quechua | quechua-dominant | bilingual quechua-spanish | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| 6 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 8 |

| 7 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 13 |

| 8 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

5.2. Correlating language dominance and speech production.

Five parameters, reflecting the child’s expressive and receptive language experiences in Quechua and Spanish, were correlated with the children’s phonetic outcomes. Maternal language profile modeled the mothers’ language dominance from the background survey conducted during testing. The four remaining parameters were calculated from the annotated corpus. See Table 5.

Table 5.

Language exposure parameters used in modeling.

| parameter | type | description |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal language profile | Receptive | Three levels: monolingual Quechua, Quechua-dominant, and bilingual Quechua-Spanish |

| % of child’s monolingual Spanish clips | Expressive | Calculated by dividing the number of monolingual Spanish clips where the target child was speaking by the total number of language clips where the child was speaking* |

| % of child’s mixed language clips | Expressive | Calculated by adding the total number of Quechua clips and mixed clips where the target child was speaking and then dividing it by the total number of clips where the child was speaking† |

| % of other speakers’ monolingual Spanish clips | Receptive | The percentage of monolingual Spanish clips in the recording where an adult or other child—not the target child—was speaking; calculated by dividing the number of Spanish clips where an adult or other child (i.e. sibling) was speaking by the total number of language clips containing an adult or other child |

| % of other speakers’ monolingual Quechua clips | Receptive | Calculated by dividing the number of monolingual Quechua clips where an adult or other child was speaking by the total number of language clips containing an adult or other child |

Notes:

Language clips were defined as those annotated as Spanish, Quechua, or mixed, and not clips annotated as unsure, no speech, or containing personal identifying information.

Both monolingual Quechua clips and mixed Quechua/Spanish clips were used, instead of just monolingual Quechua clips, because some children had very few monolingual Quechua clips in which they were speaking. Figures representing the relationship between both speech production outcomes and just the percentage of monolingual Quechua clips, not including mixed clips, are included in Supplement 3. Similar results were found across the samples.

Vowel category dispersion.

The first parameter studied is the effect of maternal language profile on the children’s three phonemic /a, i, u/ and two allophonic [e, o] Quechua vowels (Figure 7; see Supplement 4 for individual vowel plots). Maternal language profile predicted the children’s vowel dispersion. Children with monolingual mothers appear to have tighter, less variable Quechua vowel categories: their average vowel category dispersion coefficient was consistently smaller than the average coefficient of the children with Quechua-dominant or bilingual mothers, especially for the peripheral, phonemic /a, i, u/ (summary statistics in Table 6). The only exception was for [o], which had an average category dispersion coefficient of 0.60 (SD = 0.39) for the children with Quechua-dominant mothers and 0.63 (SD = 0.37) for the children with monolingual Quechua mothers. The standard deviation of the coefficients also tended to be smaller for the children with monolingual mothers, suggesting that, as a group, they had more uniform vowel variability.

Figure 7.

Children’s vowel spaces by maternal language profile. Ellipses represent 95% CIs, or approximately 2 SDs of all data, assuming a normal t-distribution. Individual points represent a random subset of eight tokens per vowel category.

Table 6.

Average and standard deviation (in parentheses) of vowel category dispersion by phone and maternal language profile.

| [a] | [e] | [i] | [o] | [u] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monolingual Quechua | 0.69 (0.47) | 0.61 (0.36) | 0.44 (0.27) | 0.63 (0.37) | 0.58 (0.41) |

| Quechua-dominant | 1.03 (0.59) | 0.70 (0.30) | 0.60 (0.31) | 0.60 (0.39) | 0.85 (0.55) |

| Bilingual Quechua-Spanish | 0.91 (0.57) | 0.78 (0.51) | 0.63 (0.50) | 0.70 (0.40) | 0.84 (0.60) |

There were also differences between the children with Quechua-dominant mothers and those with bilingual mothers. Children with bilingual mothers had more expansive [e] and [i] categories (larger coefficient), while [a] dispersion was larger for the Quechua-dominant group. When considering differences between language profile groups, it is important to note that the group with bilingual mothers had almost four times as many children (n = 23) as the group with Quechua-dominant mothers (n = 6), and more than twice as many children as the group with monolingual Quechua mothers (n = 10). Still, the differences in vowel patterning suggest that mothers’ language dominance affects the children’s vowel dispersion.

As the vowel plots in Fig. 7 show, there was considerable overlap between the allophonic vowels [e] and [o] and their underlying phonemic forms /i/ and /u/, respectively. This overlap does not appear to qualitatively differ by maternal language profile, even though one could expect children with bilingual mothers to have more distinct [e] and [o] categories—those vowels are phonemic in Spanish, which may be the children’s dominant language. Instead, there are similar amounts of overlap between the allophonic and phonemic vowels across the three maternal language profiles, suggesting that all children employed a Quechua vowel system during the task.

To further evaluate the effect of maternal language profile on the children’s vowel variability, a series of linear mixed-effects models were fit. The dependent variable was the dispersion coefficient of each child’s vowel category or, ideally, five coefficient estimations (one for each vowel) per child, though some vowel categories were removed due to a low number of observations (see tables in Supplement 2 for removal statistics, as well as the number of tokens by vowel category and maternal language profile used in modeling).

First, a baseline model with a random effect of speaker was fit to predict the dispersion coefficients. The parameter phone was then added, which unsurprisingly improved model fit. Next, the parameter maternal language profile, with the levels Monolingual Quechua, Quechua-dominant, and Bilingual Quechua-Spanish, was added. Maternal language profile significantly improved upon a model fit containing Phone and the random effect of Speaker, under an alpha level of 0.10 (model summary presented in Table 7). There was no effect of child age on vowel dispersion. This modeling shows a trend that the mother’s language profile predicts vowel variability in these bilingual children. More specifically, the positive coefficients for the levels of Maternal language profile, with a reference level of Monolingual Quechua, show a trend that children with Quechua-dominant and bilingual Quechua-Spanish caregivers have more variable vowels.

Table 7.

Model predicting vowel category variability.

| estimate β [CI] | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (intercept) | 0.63 [0.47, 0.79] | 7.88 | < 0.001 | *** |

| Phone: [e] | −0.25 [−0.40, −0.09] | −3.16 | 0.002 | ** |

| Phone: [i] | −0.29 [−0.43, −0.15] | −4.10 | < 0.001 | *** |

| Phone: [o] | −0.35 [−0.52, −0.18] | −4.14 | < 0.001 | *** |

| Phone: [u] | −0.14 [−0.29, 0.02] | −1.68 | 0.10 | + |

| Lang. profile: Quechua-dominant | 0.20 [−0.01, 0.41] | 1.86 | 0.07 | + |

| Lang. profile: Bilingual | 0.15 [−0.01, 0.30] | 1.87 | 0.07 | + |

Note:

p < 0.1,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.