Abstract

Background:

Adult cancer survivors (ACS) are at increased risk for developing various comorbid conditions and having poor health-related quality of life (HRQOL) when compared to adults with no history of cancer. The effect of social and emotional support on HRQOL among ACS is not fully elucidated. The purpose of this study was to understand the role of social and emotional support on HRQOL in ACS and to examine if the association between social and emotional support and HRQOL is modified by gender, time since cancer diagnosis, or marital status.

Methods:

Data for this study were obtained from the 2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Statistical analysis was based on ACS with complete data (n = 23,939) on all variables considered. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to model the association between social and emotional support and indicators of HRQOL (i.e., general health, physical health, mental health, and activity limitation). To examine if gender, marital status, or the number of years since cancer diagnosis modify the association, separate stratified analyses were conducted.

Results:

When compared to ACS who reported that they Rarely/Never received social and emotional support, those who reported that they Always received were 32 % less likely to report Fair/Poor General health, 23 % less likely to report frequent unhealthy days of Physical health, 73 % less likely to report frequent unhealthy days of Mental health and 38 % less likely to report frequent unhealthy days of Activity limitation. Social and emotional support was positively associated with all four domains of HRQOL among ACS who were female, unmarried, or greater than 5 years since cancer diagnosis, while this positive association was evident only with one or two domains of HRQOL among their corresponding counterparts (i.e., male, married, less than 5 years since diagnosis).

Conclusions:

Social and emotional support is an important factor directly related to a better HRQOL, but it is modified by gender, marital status, and time since diagnosis. Findings from this study should inform health care providers about the importance of a support system for ACS in improving their overall quality of life.

Keywords: Adult cancer survivors, Social and emotional support, HRQOL, Health related quality of life, BRFSS

1. Introduction

Advances in early stage diagnosis and cancer treatments in the United States (U.S.) led to increasing number of cancer survivors during the past three decades. The 5-year cancer survival rate during 2011–2017 was 66.2 % [1]. As of January 1, 2019, an estimated 16.9 million cancer survivors lived in the U.S. and this number is expected to increase to more than 22.1 million by 2030. Among those currently living in the U.S., majority of them (67 %) were diagnosed 5 or more years ago [2]. As cancer is changing from a life-threating disease into a chronic condition [3], adult cancer survivors (ACS) are at increased risk for developing various comorbid conditions and having poor health related quality of life (HRQOL) when compared to adults with no history of cancer [4–9]. HRQOL is a multidimensional construct comprising individual’s self-rated general, physical, mental, and social functioning [10]. As such, there has been a growing interest in evaluating the determinants (e.g., social and emotional support) that may attenuate some of the negative effects of cancer and cancer treatment on HRQOL of the cancer survivors [11].

Social support includes both structural and functional support. Structural support is about the composition of a social network or sources of support while functional support is about the provision of specific resources or types of support (e.g., emotional support). Emotional support is well documented to facilitate the psychological adjustment to cancer [12]. It is the perceived availability of caring, trusting individuals with whom life experiences can be shared. It involves the provision of love, trust, empathy, and caring, and is the most often thought of support protecting individuals from potentially adverse effects of stressful events in life [13–15].

Lack of social and emotional support is shown to be significantly associated with poor HRQOL in a large community sample of adults in the U.S. [16]. And, several other studies have reported positive impact of social support on HRQOL in populations involving older adults [17], migrant workers [18], HIV-infected individuals [19], kidney disease patients [20], patients with multiple sclerosis [21], and individuals with hip and knee osteoarthritis [22]. However, the effect of social and emotional support on HRQOL among ACS is not fully elucidated. The purpose of this study was to understand the role of social and emotional support on HRQOL in ACS and to examine if the association between social and emotional support and HRQOL is modified by gender, time since cancer diagnosis, or marital status.

2. Methods

2.1. General study design and population

Data for this study were obtained from the 2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). The BRFSS is a federally funded telephone survey designed and conducted annually by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in collaboration with state health departments in all 50 states, Washington, DC; Puerto Rico; the US Virgin Islands; and Guam. The survey collects data on health conditions, preventive health practices and risk behaviors of the adults’ selected [23]. The BRFSS methods, sample selection, including the weighting procedure and technical information, are described elsewhere [24]. All BRFSS questionnaires, data and reports are available at http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/. The median cooperation / response rates according to the Council of American Survey Research Organizations (CASRO) were 75.0 % and 52.5 % [25].

2.2. Cancer survivors

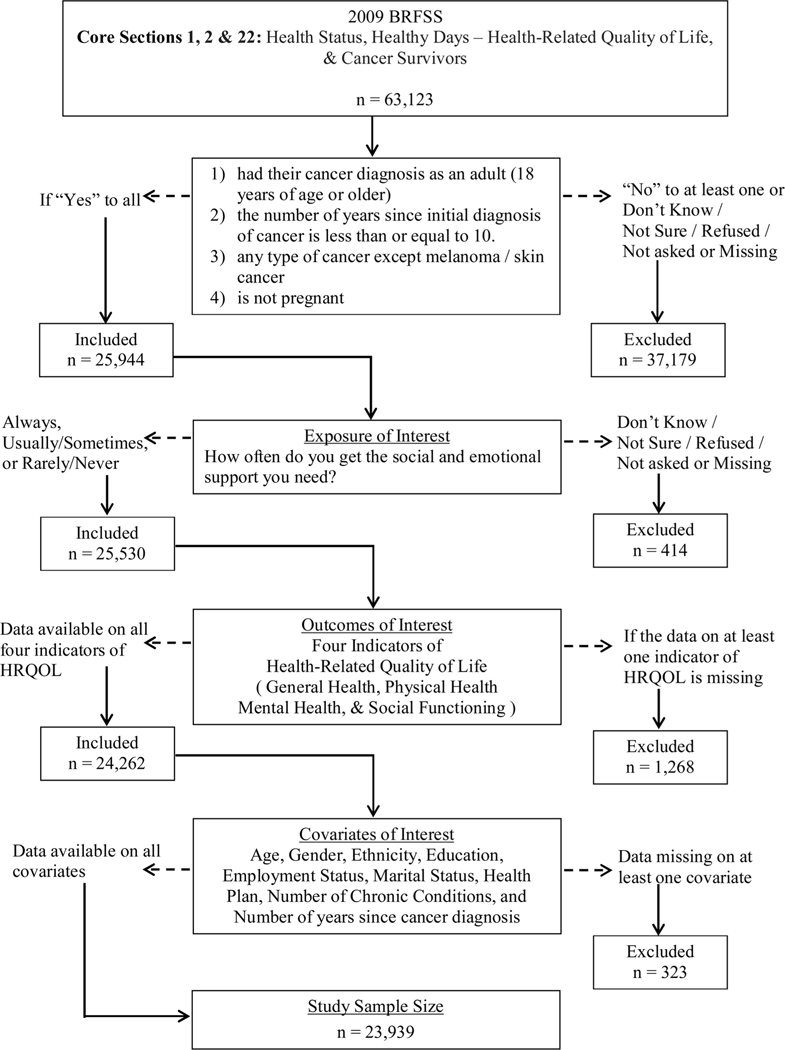

In the 2009 BRFSS, 63,123 respondents with an affirmative answer to the following question: “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that you had cancer?” were identified as cancer survivors. These respondents were further asked about i) how many different types of cancer they had, ii) their age at initial diagnosis, and iii) the type of cancer they have been diagnosed with. In this study, we restricted our study sample to those who satisfied the following criteria: 1) had their cancer diagnosis as an adult (18 years of age or older), 2) the number of years since initial diagnosis of cancer is less than or equal to ten, 3) any type of cancer except melanoma / skin cancer, and 4) is not pregnant. This resulted in 25,944 adult cancer survivors (ACS). Individuals with missing information on variables of exposure of interest (n =414), outcomes of interest (n =1,268), or covariates of interest (n = 232) are excluded which resulted in 23,939 subjects as the final sample size of the study (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchar of Study Population and Sample Size.

2.3. Social and emotional support (SES): primary exposure of interest

SES was assessed by asking the question: “How often do you get the social and emotional support you need?” Possible responses were: Always, Usually, Sometimes, Rarely, or Never. In our analysis, we divided these responses into three categories: Always, Usually/Sometimes, and Rarely/Never. Since the actual support received was not measured objectively in this study, responses from the study participants to this question on SES are considered as perceived rather than received.

2.4. Health related quality of life (HRQOL): outcomes of interest

Four HRQOL indicators were examined as outcomes of interest: general health was assessed by asking participants to rate their overall health. Possible responses were “Excellent”, “Very good”, “Good”, “Fair”, or “Poor”. The responses were dichotomized into two groups: “Excellent / Very good / Good” and “Fair / Poor”. The other three HRQOL indicators are physical health, mental health and social functioning, which were assessed by asking the respondents to self-rate their health in the past 30 days: “Now thinking about your physical health, which includes physical illness and injury, for how many days during the past 30 days was your physical health not good?” (physical health); “Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?” (mental health); “During the past 30 days, for about how many days did poor physical or mental health keep you from doing your usual activities, such as self-care, or recreation?” (social functioning). Responses were dichotomized into <14 (infrequent) and ≥14 (frequent) unhealthy days for each indicator.

2.5. Covariates of interest

Socio-demographic variables: age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education, employment; Comorbidities: heart attack, coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, asthma, and arthritis; and health plan and number of years since cancer diagnosis, were considered as covariates of interest in this study.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Sampling weights provided in the 2009 BRFSS public-use data that adjust for unequal selection probabilities, survey non-response, and oversampling were used to account for the complex sampling design and to obtain population-based estimates which reflect US non-institutionalized ACS. Weighted prevalence estimates and corresponding 95 % confidence intervals (CI) were computed to describe the characteristics of the study population. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to model the association between social and emotional support and indicators of HRQOL. To explore if gender (male vs. female), marital status (married vs. unmarried), and the number of years since cancer diagnosis (0–5 years vs. 6–10 years), since some cancer survivors may have been under active treatment at the time of the interview, may have modified the association between social and emotional support and indicators of HRQOL, separate stratified analyses were conducted. We determined statistical significance by examining the non-overlapping 95 % confidence intervals.

Statistical analysis was based on ACS with complete data (n = 23,939) on all variables considered in this study (Fig. 1). All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) using SAS survey procedures (PROC SURVEYFREQ, PROC SURVEYMEANS, PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC) to account for the complex sampling design. Differences were considered significant at P < .05 using two-tailed tests.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-demographic characteristics of ACS

A little more than half of the ACS reported that they “Always” received social and emotional support [52.8 % (95 % CI: 51.6%–54.1%)], almost forty percent reported that they “Usually / Sometimes” received social and emotional support [39.3 % (95 % CI: 38.0%–40.5%)], and less than one-tenth of them reported they “Never” received social and emotional support [7.9 % (95 % CI: 7.3%–8.6%)]. Table 1 describes the sample characteristics of ACS. The average age of ACS in this study was about 61 years. They were predominantly female (55.5 %), White non-Hispanic (78.7 %), married (66.4 %), college graduates (36.1 %), and not employed (60.8 %). The average number of years since cancer diagnosis was about four and half years and less than ten percent of ACS reported being diagnosed with two or more types of cancer. More than ninety percent reported having a health plan and a little over sixty percent reported having at least one other chronic disease other than cancer. Three out of 10 ACS reported “Fair/Poor” health in general, less than fifteen percent reported frequent unhealthy days of mental health and social functioning during the past 30 days of the month.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of adult cancer survivors, according to perceived social and emotional support.

| Overall (n = 23939) | Rarely/Never (n = 2068) | Usually/Sometimes (n = 9622) | Always (n = 12249) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted “n” | Mean or Proportion (95 % CI) | Mean or Proportion (95 % CI) | Mean or Proportion (95 % CI) | Mean or Proportion (95 % CI) | ||||

| Sociodemographic | ||||||||

| Age | 23939 | 60.6(60.2, 61.0) | 61.9 | (60.1, 63.6) | 59.4 | (58.7, 60.1) | 61.3 | (60.7, 61.9) |

| Years since cancer diagnosis | 23939 | 4.4(4.3, 4.5) | 4.5 | (4.3, 4.8) | 4.4 | (4.3, 4.6) | 4.4 | (4.3, 4.5) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 9684 | 44.5(43.3, 45.8) | 51.5 | (47.2, 55.9) | 40.5 | (38.5, 42.5) | 46.5 | (44.7, 48.3) |

| Female | 14255 | 55.5(54.2, 56.7) | 48.5 | (44.1, 52.8) | 59.5 | (57.5, 61.5) | 53.5 | (51.7, 55.3) |

| Education | ||||||||

| High School or less | 2112 | 9.0(8.2, 9.8) | 19.3 | (15.7, 22.9) | 8.0 | (6.9, 9.1) | 8.2 | (7.2, 9.3) |

| High School graduate | 7238 | 27.1(26.0, 28.1) | 34.5 | (30.6, 38.3) | 26.1 | (24.4, 27.9) | 26.6 | (25.1, 28.1) |

| Some college or technical School | 6474 | 27.8(26.6, 29.0) | 26.6 | (22.4, 30.8) | 27.9 | (26.0, 29.7) | 28.0 | (26.3, 29.7) |

| College graduate | 8115 | 36.1(34.9, 37.3) | 19.6 | (16.5, 22.8) | 38.0 | (36.1, 40.0) | 37.2 | (35.5, 38.9) |

| Marriage | ||||||||

| Married | 13450 | 66.4(65.3, 67.6) | 49.1 | (44.8, 53.4) | 63.1 | (61.2, 65.0) | 71.5 | (69.9, 73.1) |

| Previously Marrieda | 8566 | 25.1(24.0, 26.1) | 37.7 | (33.9, 41.6) | 27.2 | (25.5, 28.8) | 21.6 | (20.2, 23.0) |

| Unmarried | 1923 | 8.5(7.7, 9.3) | 13.2 | (9.4, 16.9) | 9.7 | (8.5, 10.9) | 6.9 | (5.8, 7.9) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White Non-Hispanic | 20687 | 78.7(77.2, 80.1) | 70.1 | (65.6, 74.7) | 79.3 | (77.1, 81.5) | 79.5 | (77.5, 81.4) |

| Black Non-Hispanic | 1347 | 7.8(6.9, 8.7) | 12.4 | (8.1, 16.7) | 7.6 | (6.2, 8.9) | 7.2 | (6.0, 8.4) |

| Hispanic | 913 | 8.4(7.3, 9.5) | 9.5 | (7.0, 12.1) | 7.6 | (5.9, 9.2) | 8.8 | (7.1, 10.5) |

| Other Non-Hispanicb | 992 | 5.2(4.4, 6.0) | 8.0 | (5.4, 10.5) | 5.5 | (4.1, 7.0) | 4.5 | (3.5, 5.5) |

| Employment Status | ||||||||

| Employed | 8204 | 39.2(37.9, 40.5) | 26.6 | (22.8, 30.4) | 42.9 | (40.9, 45.0) | 38.2 | (36.4, 40.1) |

| Out of work | 923 | 5.3(4.6, 6.0) | 6.7 | (4.7, 8.7) | 5.6 | (4.5, 6.6) | 4.9 | (3.9, 5.9) |

| Retired | 2075 | 8.4(7.7, 9.0) | 14.9 | (12.3, 17.6) | 8.4 | (7.3, 9.3) | 7.4 | (6.5, 8.3) |

| Unable to work | 1585 | 8.0(7.2, 8.8) | 8.6 | (4.7, 12.5) | 7.3 | (6.3, 8.4) | 8.5 | (7.2, 9.7) |

| Homemaker/Student | 11152 | 39.1(38.0, 40.3) | 43.2 | (39.1, 47.3) | 35.8 | (33.9, 37.7) | 41.0 | (39.3, 42.7) |

| Other Variables of Interest | ||||||||

| General Health | ||||||||

| Excellent/Very Good | 16385 | 69.0(67.8, 70.2) | 53.2 | (48.9, 57.4) | 70.0 | (68.1, 71.9) | 70.6 | (69.0, 72.3) |

| Fair/Poor | 7554 | 31.0(29.8, 32.2) | 46.8 | (42.6, 51.1) | 30.0 | (28.1, 31.9) | 29.4 | (27.7, 31.0) |

| Physical Health | ||||||||

| 0 – 13 days | 18647 | 77.5(76.4, 78.6) | 66.9 | (63.0, 70.7) | 77.9 | (76.2, 79.6) | 78.8 | (77.3, 80.3) |

| 14 – 30 days | 5292 | 22.5(21.4, 23.6) | 33.1 | (29.3, 37.0) | 22.1 | (20.4, 23.8) | 21.2 | (19.7, 22.7) |

| Mental Health | ||||||||

| 0 – 13 days | 21218 | 87.5(86.7, 88.4) | 71.2 | (66.9, 75.5) | 85.4 | (84.0, 86.8) | 91.6 | (90.5, 92.7) |

| 14 – 30 days | 2721 | 12.5(11.6, 13.3) | 28.8 | (24.5, 33.1) | 14.6 | (13.2, 16.0) | 8.4 | (7.3, 9.5) |

| Poor Health | ||||||||

| 0 – 13 days | 20731 | 86.1(85.1, 87.0) | 76.0 | (71.9, 80.2) | 85.7 | (84.3, 87.2) | 87.8 | (86.6, 89.0) |

| 14 – 30 days | 3208 | 13.9(13.0, 14.9) | 24.0 | (19.8, 28.1) | 14.3 | (12.8, 15.7) | 12.2 | (11.0, 13.4) |

| Number of cancer type | ||||||||

| One | 21453 | 90.3(89.6, 91.0) | 91.1 | (89.2, 93.0) | 90.9 | (89.9, 91.9) | 89.8 | (88.7, 90.9) |

| Two | 2149 | 8.5(7.8, 9.2) | 8.1 | (6.2, 9.9) | 8.1 | (7.2, 9.1) | 8.8 | (7.8, 9.9) |

| Three or more | 337 | 1.2(0.9, 1.4) | 0.8 | (0.4, 1.3) | 1.0 | (0.6, 1.3) | 1.4 | (1.0, 1.7) |

| Health Plan | ||||||||

| No | 1143 | 6.5(5.7, 7.3) | 10.0 | (6.5, 13.5) | 7.2 | (6.1, 8.4) | 5.4 | (4.3, 6.5) |

| Yes | 22796 | 93.5(92.7, 94.3) | 90.0 | (86.5, 93.5) | 92.8 | (91.6, 93.9) | 94.6 | (93.5, 95.7) |

| Number of Chronic Conditions | ||||||||

| 0 | 8273 | 38.3(37.0, 39.6) | 29.0 | (24.7, 33.3) | 38.4 | (36.4, 40.4) | 39.6 | (37.7, 41.4) |

| 1 | 9396 | 38.1(36.8, 39.3) | 38.0 | (33.8, 42.1) | 38.0 | (36.1, 40.0) | 38.1 | (36.4, 39.8) |

| 2 | 4104 | 15.6(14.7, 16.5) | 20.9 | (17.6, 24.1) | 15.9 | (14.4, 17.4) | 14.6 | (13.5, 15.7) |

| ≥3 | 2166 | 8.1(7.5, 8.7) | 12.1 | (9.7, 14.6) | 7.7 | (6.6, 8.7) | 7.7 | (7.0, 8.5) |

Previously Married includes those divorced, widowed, or separated.

Other Non-Hispanic includes Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, American Indian, Alaskan Native, multiracial and other race, non-Hispanic.

3.2. Socio-demographic characteristics of ACS across the three groups of perceived social and emotional support

There was no difference in the average number of years since cancer diagnosis across the three groups of perceived social and emotional support. Though there was no statistically significant difference between the proportion of males and females who reported that they “Rarely/Never” received social and emotional support, the proportion of females who reported that they “Usually/Sometimes” or “Always” received social and emotional support was significantly higher than in the males. The proportion of college graduates in the “Rarely/Never” category of social and emotional support was significantly lower when compared to the other two categories of social and emotional support. The proportion of ACS who reported being married was the highest in the “Always” (71.5 %) category of social and emotional support, following by the “Usually/Sometimes” (63.1 %), and “Rarely” (49.1 %) categories, and these differences in proportions were significant. The proportion of ACS in the “Rarely/Never” category of social and emotional support who were employed, have no chronic diseases other than cancer was significantly lower when compared to the other two categories of social and emotional support. There were no significant differences between the three categories of social and emotional support for ethnicity, having a health plan, and number of cancer types.

3.3. Health related quality of life across the three groups of perceived social and emotional support

Adult cancer survivors in “Rarely/Never” category of social and emotional support were significantly higher in proportion to report “Fair/Poor” general health [46.8 % (95 % CI: 42.6%–51.1%)], when compared to those in the “Usually/Sometimes” category [30.0 % (95 % CI: 28.1%–31.9%)], and those in the “Always” category [29.4 % (95 % CI: 27.7%–31.0%)] of social and emotional support. This pattern was also true with frequent unhealthy days of physical health and social functions in the past 30 days of the month, and ii) frequent unhealthy days of social functioning in the past 30 days. Notably, the proportion of adult cancer survivors in “Rarely/Never” category of social and emotional support who reported frequent unhealthy days of mental health in the past 30 days of the month was significantly higher [28.8 % (95 % CI: 24.5%–33.1%)], followed by those in the “Usually/Sometimes” category [14.6 % (95 % CI: 13.2%–16.0%)], and those in the “Always” category [8.4 % (95 % CI: 7.3 %–9.5 %)] of social and emotional support.

Table 2 presents model based unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios with 95 % CIs for frequent unhealthy days during the past 30 days of all four indicators of HRQOL in all ACS who reported that they “Always” or “Usually/Sometimes” received social and emotional support when compared to those who reported that they “Rarely/Never” received (reference group). After adjusting for all socio-demographic variables, perceived SES was negatively associated with frequent unhealthy days in the past 30 days of the month for all four indicators of HRQOL. When compared to ACS who reported that they “Rarely/Never” received social and emotional support, those who reported that they “Always” received were 32 % less likely to report “Fair/Poor” general health (AOR: 0.68 [95 % CI: 0.55 – 0.85]), 23 % less likely to report frequent unhealthy days of physical health during the past 30 days (AOR: 0.77 [95 % CI: 0.62 – 0.95]), 73 % less likely to report frequent unhealthy days of mental health during the past 30 days (AOR: 0.27 [95 % CI: 0.21 – 0.34]), and 38 % less likely to report frequent unhealthy days of physical health during the past 30 days (AOR: 0.62 [95 % CI: 0.48 – 0.79]). ACS who reported that they “Usually/Sometimes” received social and emotional support has similar finding when compared to those who reported that they “Rarely/Never” received (reference group).

Table 2.

Social and Emotional Support and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Adult Cancer Survivors.

| Variables | Rarely/Never (n = 2068) | Emotional Support Usually/Sometimes (n = 9622) | Always (n = 12249) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Health * | |||

| UOR (95 %CI) | Referent | 0.49(0.40 – 0.59) | 0.47(0.39− 0.57) |

| AOR (95 %CI) | Referent | 0.70(0.56 – 0.87) | 0.68(0.55 – 0.85) |

| Frequent Physical Distress (≥ 14 days) | |||

| UOR (95 %CI) | Referent | 0.57(0.47 – 0.70) | 0.54(0.45 – 0.66) |

| AOR (95 %CI) | Referent | 0.80(0.64 – 0.10) | 0.77(0.62 – 0.95) |

| Frequent Mental Distress (≥ 14 days) | |||

| UOR (95 %CI) | Referent | 0.42(0.33 – 0.54) | 0.23(0.18 – 0.29) |

| AOR (95 %CI) | Referent | 0.48(0.38 – 0.60) | 0.27(0.21 – 0.34) |

| Frequent Activity Limitation (≥ 14 days) | |||

| UOR (95 %CI) | Referent | 0.53(0.41 – 0.68) | 0.44(0.34 – 0.57) |

| AOR (95 %CI) | Referent | 0.91(0.75–1.10) | 0.62(0.48 – 0.79) |

UOR: Unadjusted Odds Ratio; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; 95 % CI: 95 % Confidence Interval.

“Excellent” or “Very Good” or “Good” General Health.

3.4. Model based prevalence odds ratios for “Fair/Poor” general health, frequent unhealthy days of physical, mental health, and social functioning by gender, marital status, and number of years since cancer diagnosis

Tables 3–5 present results from three different stratified analysis: i) gender (males vs. females), ii) number of years since cancer diagnosis (0–5 years vs. 6–10 years), and iii) marital status (married vs. unmarried). When compared to female ACS who reported that they “Rarely/Never” received social and emotional support, those who reported that they “Always” or “Usually/Sometimes” received were significantly less likely to report “Fair/Poor” general health and frequent unhealthy days of physical health, mental health, and social functioning, during the past 30 days. However, among males, such finding was only significant for frequent unhealthy days of mental health during the past 30 days (Table 3).

Table 3.

Social and Emotional Support and HRQoL among adult cancer survivors by Gender.

| Variables | Emotional Support (MALE) | Emotional Support (FEMALE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rarely/Never (n = 2068) | Usually/Sometimes (n = 9622) | Always (n = 12249) | Rarely/Never (n = 2068) | Usually/Sometimes (n = 9622) | Always (n = 12249) | |

| General Health * | ||||||

| UOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.56(0.43 – 0.73) | 0.59(0.46 – 0.76) | Referent | 0.40(0.30 – 0.54) | 0.37(0.28 – 0.50) |

| AOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.75(0.56–1.01) | 0.78(0.59–1.04) | Referent | 0.64(0.46 – 0.88) | 0.59(0.43 – 0.82) |

| Frequent Physical Distress (≥ 14 days) | ||||||

| UOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.71(0.54 – 0.93) | 0.71(0.54 – 0.92) | Referent | 0.46(0.34 – 0.61) | 0.42(0.32 – 0.56) |

| AOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.85(0.63–1.15) | 0.86(0.64–1.16) | Referent | 0.68(0.50 – 0.92) | 0.63(0.47 – 0.86) |

| Frequent Mental Distress (≥ 14 days) | ||||||

| UOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.61(0.44 – 0.84) | 0.36(0.26 – 0.51) | Referent | 0.29(0.21 – 0.40) | 0.15(0.11 – 0.21) |

| AOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.64(0.44 – 0.92) | 0.39(0.27 – 0.56) | Referent | 0.39(0.29 – 0.52) | 0.21(0.15 – 0.29) |

| Frequent Activity Limitation (≥ 14 days) | ||||||

| UOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.75(0.54–1.03) | 0.68(0.50 – 0.92) | Referent | 0.38(0.27 – 0.55) | 0.31(0.21 – 0.44) |

| AOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.94(0.65–1.34) | 0.85(0.60–1.20) | Referent | 0.58(0.40 – 0.84) | 0.45(0.32 – 0.65) |

UOR: Unadjusted Odds Ratio; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; 95 % CI: 95 % Confidence Interval.

“Excellent” or “Very Good” or “Good” General Health.

Table 5.

Social and Emotional Support and HRQoL among adult cancer survivors by years since diagnosis.

| Variables | Emotional Support (0− 5 years) | Emotional Support (6–10 years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rarely/Never (n = 2068) | Usually/Sometimes (n = 9622) | Always (n = 12249) | Rarely/Never (n = 2068) | Usually/Sometimes (n = 9622) | Always (n = 12249) | |

| General Health * | ||||||

| UOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.57(0.44 – 0.73) | 0.58(0.45 – 0.74) | Referent | 0.37(0.27 – 0.49) | 0.32(0.24 – 0.43) |

| AOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.83(0.62–1.11) | 0.88(0.66–1.17) | Referent | 0.53(0.39 – 0.71) | 0.45(0.34 – 0.60) |

| Frequent Physical Distress (≥ 14 days) | ||||||

| UOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.67(0.52 – 0.87) | 0.64(0.50 – 0.83) | Referent | 0.42(0.31 – 0.57) | 0.39(0.29 – 0.53) |

| AOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.98(0.73–1.30) | 0.95(0.72–1.25) | Referent | 0.56(0.40 – 0.77) | 0.53(0.38 – 0.73) |

| Frequent Mental Distress (≥ 14 days) | ||||||

| UOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.43(0.31 – 0.58) | 0.25(0.18 – 0.35) | Referent | 0.42(0.30 – 0.60) | 0.19(0.13 – 0.29) |

| AOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.50(0.37 – 0.67) | 0.30(0.22 – 0.40) | Referent | 0.44(0.31 – 0.62) | 0.22(0.15 – 0.32) |

| Frequent Activity Limitation (≥ 14 days) | ||||||

| UOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.59(0.42 – 0.83) | 0.51(0.36 – 0.72) | Referent | 0.43(0.30 – 0.62) | 0.33(0.23 – 0.48) |

| AOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.84(0.61–1.17) | 0.74(0.54–1.01) | Referent | 0.60(0.40 – 0.88) | 0.46(0.32 – 0.68) |

UOR: Unadjusted Odds Ratio; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; 95 % CI: 95 % Confidence Interval.

“Excellent” or “Very Good” or “Good” General Health.

Similarly, receiving social and emotional support “Always” or “Usually/Sometimes” was protective only against frequent unhealthy days of mental health during the past 30 days among ACS whose number of years since cancer diagnosis was 0–5 years but was protective against poor HRQOL on all four indicators among ACS whose number of years since cancer diagnosis was 6–10 years (Table 4).

Table 4.

Social and Emotional Support and HRQoL among adult cancer survivors by marital status.

| Variables | Emotional Support (Married) | Emotional Support (Unmarried) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rarely/Never (n = 2068) | Usually/Sometimes (n = 9622) | Always (n = 12249) | Rarely/Never (n = 2068) | Usually/Sometimes (n = 9622) | Always (n = 12249) | |

| General Health * | ||||||

| UOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.43(0.32 – 0.57) | 0.47(0.36 – 0.62) | Referent | 0.63(0.49 – 0.83) | 0.56(0.43 – 0.74) |

| AOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.65(0.48 – 0.89) | 0.70(0.52− 0.96) | Referent | 0.78(0.57–1.05) | 0.65(0.48 – 0.88) |

| Frequent Physical Distress (≥ 14 days) | ||||||

| UOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.63(0.46 – 0.86) | 0.59(0.44 – 0.80) | Referent | 0.58(0.45 – 0.76) | 0.62(0.47 – 0.82) |

| AOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.97(0.70–1.34) | 0.88(0.64–1.19) | Referent | 0.67(0.49 – 0.91) | 0.71(0.52 – 0.98) |

| Frequent Mental Distress (≥ 14 days) | ||||||

| UOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.52(0.36 – 0.75) | 0.29(0.20 – 0.42) | Referent | 0.39(0.28 – 0.53) | 0.21(0.15 – 0.30) |

| AOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.64(0.45 – 0.90) | 0.36(0.25 – 0.51) | Referent | 0.39(0.29 – 0.53) | 0.21(0.16 – 0.29) |

| Frequent Activity Limitation (≥ 14 days) | ||||||

| UOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 0.66(0.45 – 0.98) | 0.54(0.37 – 0.78) | Referent | 0.47(0.34 – 0.66) | 0.45(0.31 – 0.64) |

| AOR (%95 %CI) | Referent | 1.05(0.70–1.58) | 0.81(0.55–1.17) | Referent | 0.54(0.38 – 0.75) | 0.50(0.35 – 0.72) |

UOR: Unadjusted Odds Ratio; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; 95 % CI: 95 % Confidence Interval.

“Excellent” or “Very Good” or “Good” General Health.

Finally, when compared to “Rarely/Never” category of social and emotional support, being in one of the other two categories (“Always” or “Usually/Sometimes”) significantly reduced the likelihood to report poor HRQOL on all four indicators among unmarried ACS while this protective effect was significant only for general health and frequent unhealthy days of mental health during the past 30 days among married ACS (Table 5).

4. Discussion

The current study examined the association between social and emotional support and health related quality of life among a community dwelling sample of adult cancer survivors in the US. We found ACS who reported receipt of social and emotional support were more likely to report positive HRQOL. In addition, this study also examined the association between social and emotional support and HRQOL across gender (male vs. female), marital status (married vs. unmarried), and the number of years since cancer diagnosis (0–5 years vs. 6–10 years). Social and emotional support was positively associated with all four domains of HRQOL among ACS who were female, unmarried, or in the 0–5 years since cancer diagnosis, while this positive association was evident only with one or two domains of HRQOL among their corresponding counterparts. Findings from this study should inform health care providers about the importance of a support system for ACS in improving their overall quality of life.

Consistent with findings of previous research among cancer survivors of certain types of cancer [26–29], our results suggest that social and emotional support is an important factor directly related to a better HRQOL. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report the positive association between social and emotional support and HRQOL among adult cancer survivors of all types of cancer, except melanoma / skin cancer, with the number of years since initial diagnosis of cancer is ≤ 10 in a nationally representative community dwelling sample in the US. Additionally, though the mechanisms through which social support impacts health may differ by gender is well documented [30], the previous studies mainly focused only on few domains of HRQOL. Our study incorporated four domains of HRQOL and found that the magnitude of the association between social and emotional support and HRQOL is stronger among females compared with males. Social and emotional support was positively associated with all four domains of HRQOL among ACS who were female while this positive association was statistically significant only with one domain of HRQOL (i.e., mental health) among their male counterparts. Females are thought to be more emotional than males and they seek social and emotional support more than males do [31]. This could be a possible explanation for finding stronger association between social and emotional support and HRQOL among females than males ACS.

Although our study has important findings, it is not without limitations. First, the study findings are based on self-reported BRFSS data which may be subject to recall-bias. For example, social and emotional support is a self-reported perception of support rather than received. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the BRFSS prevents us from making conclusive inference about the temporal sequence of the association between social and emotional support and HRQOL among ACS. Third, as the BRFSS data are limited to non-institutionalized individuals, the findings of the study may not be generalizability to all ACS in the US.

In summary, these findings show that social and emotional support is an important factor directly related to a better HRQOL, but it is modified by gender, marital status, and time since diagnosis. Findings from this study should inform health care providers about the importance of a support system for ACS in improving their overall quality of life. These findings have important implications for the health care providers in helping them design more effective interventions which tailor to and target specific subgroups to improve their HRQOL.

Funding source

No external funding was secured for this study.

Financial disclosure

Authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dr. Cheruvu: conceptualized and designed the study, designed the analytic plan, conducted the analyses, drafted, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Gudina: conducted the analyses, drafted, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Drs. Gilmore, Kleckner, Arana-Chicas, Kehoe, Belcher, and Cupertino: reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group . U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, Based on 2020 Submission Data (1999–2018): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/#/Survival/ [accessed July 7, 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- [2].American Cancer Society, Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Facts & Figures 2019–2021, Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2020. [Accessed December 8, 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ganz PA, Why and how to study the fate of cancer survivors: observations from the clinic and the research laboratory, Eur. J. Cancer 39 (2003) 2136–2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Harphman WS, Long-term survivorship: late effects, in: Berger A, Portenoy RK, Weissman DE (Eds.), Principles and Practice of Supportive Oncology, Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1998, pp. 889–907. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Holmes HM, Nguyen HT, Nayak P, Oh JH, Escalante CP, Elting LS, Chronic conditions and health status in older cancer survivors, Eur. J. Intern. Med 25 (April (4)) (2014) 374–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Berry NM, Miller MD, Woodman RJ, Coveney J, Dollman J, Mackenzie CR, Koczwara B, Differences in chronic conditions and lifestyle behaviour between people with a history of cancer and matched controls, Med. J. Aust 201 (July (2)) (2014) 96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Baker F, Haffer SC, Denniston M, Health-related quality of life of cancer and noncancer patients in Medicare managed care, Cancer 97 (Feburary (3)) (2003) 674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Richardson LC, Wingo PA, Zack MM, Zahran HS, King JB, Health-related quality of life in cancer survivors between ages 20 and 64 years: population-based estimates from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, Cancer 112 (March (6)) (2008) 1380–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Reeve BB, Potosky AL, Smith AW, Han PK, Hays RD, Davis WW, Arora NK, Haffer SC, Clauser SB, Impact of cancer on health-related quality of life of older Americans, J. Natl. Cancer Inst 101 (June (12)) (2009) 860–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lim JW, Zebrack B, Social networks and quality of life for long-term survivors of leukemia and lymphoma, Support. Care Cancer (Feburary (2)) (2006) 185–192, 10.1007/s00520-005-0856-x. Epub 2005 Jul 9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [11].Sapp AL, Trentham-Dietz A, Newcomb PA, Hampton JM, Moinpour CM, Remington PL, Social networks and quality of life among female long-term colorectal cancer survivors, Cancer. 98 (October (8)) (2003) 1749–1758, 10.1002/cncr.11717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Epping-Jordan JE, Compas BE, Osowiecki DM, Oppedisano G, Gerhardt C, Primo K, Krag DN, Psychological adjustment in breast cancer: processes of emotional distress, Health Psychol. 18 (July (4)) (1999) 315–326, 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Waters EA, Liu Y, Schootman M, Jeffe DB, Worry about cancer progression and low perceived social support: implications for quality of life among early-stage breast cancer patients, Ann. Behav. Med 45 (Feburary (1)) (2013) 57–68, 10.1007/s12160-012-9406-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Caravati-Jouvenceaux A, Launoy G, Klein D, Henry-Amar M, Abeilard E, Danzon A, Pozet A, Velten M, Mercier M, Health-related quality of life among long-term survivors of colorectal cancer: a population-based study, Oncologist 16 (11) (2011) 1626–1636, 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0036. Epub 2011 Oct 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Arndt V, Merx H, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H, Quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer 1 year after diagnosis compared with the general population: a population-based study, J. Clin. Oncol 22 (December (23)) (2004) 4829–4836, 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.018. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol. 2005 Jan 1;23(1):248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].LeMasters T, Madhavan S, Sambamoorthi U, Kurian S, A population-based study comparing HRQoL among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors to propensity score matched controls, by cancer type, and gender, Psychooncology 22 (October (10)) (2013) 2270–2282, 10.1002/pon.3288. Epub 2013 Apr 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kim J, Lee JE, Social support and health-related quality of life among elderly individuals living alone in South Korea: a cross-sectional study, J. Nurs. Res 26 (October (5)) (2018) 316–323, 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kong LN, Zhang N, Yuan C, Yuan W. Yu ZY, Zhang GL, Relationship of social support and health-related quality of life among migrant older adults: the mediating role of psychological resilience, Geriatr Nurs. 42 (November (1)) (2020) 1–7, 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.10.019. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Oetzel J, Wilcox B, Archiopoli A, Avila M, Hell C, Hill R, Muhammad M, Social support and social undermining as explanatory factors for health-related quality of life in people living with HIV/AIDS, J. Health Commun 19 (6) (2014) 660–675, 10.1080/10810730.2013.837555. Epub 2014 Jan 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ibrahim N, Teo SS, Che Din N, Abdul Gafor AH, Ismail R, The role of personality and social support in health-related quality of life in chronic kidney disease patients, PLoS One 10 (July (7)) (2015) e0129015, 10.1371/journal.pone.0129015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hyarat SY, Subih M, Rayan A, Salami I, Harb A, Health related quality of life among patients with multiple sclerosis: the role of psychosocial adjustment to illness, Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs 33 (Feburary (1)) (2019) 11–16, 10.1016/j.apnu.2018.08.006. Epub 2018 Aug 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ethgen O, Vanparijs P, Delhalle S, Rosant S, Bruyère O, Reginster JY, Social support and health-related quality of life in hip and knee osteoarthritis, Qual. Life Res 13 (March (2)) (2004) 321–330, 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018492.40262.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Operational and User’s Guide. Version 3.0, 2006. Available at ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/data/brfss/userguide.pdf [Accessed August 1, 2019].

- [24].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, BRFSS Overview, Available at http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2010/overview_10.rtf [Accessed August 1, 2019], 2010.

- [25].Tai E, Buchanan N, Townsend J, Fairley T, Moore A, Richardson LC, Health status of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors, Cancer. 118 (October (19)) (2012) 4884–4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gonzalez-Saenz de Tejada M, Bilbao A, Bare M, Briones E, Sarasqueta C, Quintana JM, Escobar A, CARESS-CCR Group, Association between social support, functional status, and change in health-related quality of life and changes in anxiety and depression in colorectal cancer patients, Psychooncology. 26 (September (9)) (2017) 1263–1269, 10.1002/pon.4303. Epub 2016 Dec 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Geue K, Götze H, Friedrich M, Leuteritz K, Mehnert-Theuerkauf A, Sender A, Stöbel-Richter Y, Köhler N, Perceived social support and associations with health-related quality of life in young versus older adult patients with haematological malignancies, Health Qual. Life Outcomes 17 (August (1)) (2019) 145, 10.1186/s12955-019-1202-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Capistrant BD, Lesher L, Kohli N, Merengwa EN, Konety B, Mitteldorf D, West WG, Rosser BRS, Social support and health-related quality of life among gay and bisexual men with prostate Cancer, Oncol. Nurs. Forum 45 (July (4)) (2018) 439–455, 10.1188/18.ONF.439-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhang H, Zhao Q, Cao P, Ren G, Resilience and quality of life: exploring the mediator role of social support in patients with breast cancer, Med. Sci. Monit 23 (December) (2017) 5969–5979, 10.12659/msm.907730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Shumaker SA, Hill DR, Gender differences in social support and physical health, Health Psychol. 10 (2) (1991) 102–111, 10.1037//0278-6133.10.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cho D, Park CL, Blank TO, Emotional approach coping: gender differences on psychological adjustment in young to middle-aged cancer survivors, Psychol. Health 28 (8) (2013) 874–894, 10.1080/08870446.2012.762979. Epub 2013 Feb 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]