Abstract

Purpose

To quantify the relationship between diabetes and fatigue from pre-chemotherapy to 6 months post-chemotherapy for women with breast cancer compared to women without a history of cancer (controls).

Methods

This was a secondary analysis from a nationwide prospective longitudinal study of female patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy and controls. Diabetes diagnosis (yes/no) was obtained at baseline, and cancer-related fatigue was measured using the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory (MFSI) pre-, post-, and 6-months post-chemotherapy in patients; controls were assessed at equivalent time points. Repeated measures mixed effects models estimated the association between fatigue and diabetes controlling for cancer (yes/no), body mass index, exercise and smoking habits, baseline anxiety and depressive symptoms, menopausal status, marital status, race, and education.

Results

Among 439 patients and 235 controls (52.8±10.5 years old), diabetes was twice as prevalent among patients as controls (11.6% vs. 6.8%). At baseline, diabetes was associated with worse fatigue (4.1±1.7 points, p=0.017). Also, diabetes was associated with clinically meaningful worse fatigue throughout the study period among all participants (5.2±1.9 points, p=0.008) and patients alone (4.5±2.0, p=0.023). For the MFSI subdomains among patients, diabetes was associated with worse general (p=0.005) and mental fatigue (p=0.026).

Conclusions

Diabetes was twice as prevalent in women with breast cancer compared to controls, and diabetes was associated with more severe cancer-related fatigue in patients before and after chemotherapy and at 6 months post-chemotherapy. Interventions that address diabetes management may also help address cancer-related fatigue during chemotherapy treatment.

Keywords: Cancer-related fatigue, Chemotherapy, Diabetes, Metabolism, Supportive care

Introduction

Cancer-related fatigue is a debilitating symptom of cancer and side effect of treatment that affects at least 30–90% of patients [1–3]. Further, in approximately one-third of patients, fatigue can persist for years into survivorship [4, 5]. By definition, cancer-related fatigue is chronic, not proportional to recent activity, and not relieved by additional sleep or rest [6]. Its severity can impair the ability to perform activities of daily living, greatly reduce quality of life, and increase mortality [6–8]. There are few effective preventive strategies or treatments for cancer-related fatigue, in part because its etiology and pathophysiology are still being characterized. However, metabolic dysfunction has recently been proposed as one factor in the etiology of cancer-related fatigue [9–11]. For example, obesity, a prevalent metabolic co-morbidity, is a known risk factor for cancer-related fatigue [6, 12].

Diabetes mellitus is the most common metabolic disorder in the United States with a prevalence of at least 10.5% of all Americans [13]. At the same time, the coexistence of diabetes and cancer, specifically breast cancer, is increasingly common. Diabetes and poor glycemic control are risk factors for morbidity from cancer and its treatments. For example, in a study by Srokowski et al., patients with stage I-III breast cancer and diabetes were 1.4-times more likely to be hospitalized for chemotherapy toxicities than patients without diabetes [14]. In a study among patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, patients with diabetes needed more chemotherapy dose adjustments, had more delays between cycles, and had fewer cycles because of severe side effects compared to patients without diabetes [15]. While glycemic control does not always worsen with cancer treatment [16], ancillary medications that are commonly prescribed with chemotherapy such as steroids can interfere with glycemic control and even induce diabetes mellitus [17]. There is also substantial co-occurrence between symptoms of diabetes, symptoms of cancer, and side effects of treatment [18]. As such, diabetes is sometimes associated with increased prevalence and severity of specific symptoms/side effects including fatigue, pain, cognitive impairment, anxiety, depression, and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, some of which are pre-existing and some of which develop during cancer treatment [19]. The shared symptomatic burden and potentially overlapping metabolic mechanisms of cancer-related fatigue and diabetes support a rationale that diabetes might exacerbate cancer-related fatigue.

We hypothesized that diabetes would be associated with more severe cancer-related fatigue during curative chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer and into early survivorship. Using data from a large, nationwide longitudinal trial that followed patients with breast cancer from pre-chemotherapy to 6 months post-chemotherapy, we assessed whether diabetes was associated with worse fatigue controlling for relevant demographics, clinical characteristics, and lifestyle behaviors. We also assessed whether diabetes status was associated with a greater change in fatigue from baseline to post-chemotherapy and baseline to 6 months post-chemotherapy treatment.

Methods

Study design and participants

An observational cohort study was conducted through the University of Rochester Cancer Center (URCC) NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) Research Base to assess the trajectory of chemotherapy-induced toxicities among breast cancer patients at pre-chemotherapy, post-chemotherapy, and 6 months post-chemotherapy compared to age- and gender-matched controls without cancer (URCC10055; clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01382082). The full methods and primary aims of the parent study were published previously [20, 21]. In the parent study, patients were recruited from 22 NCORP locations across the United States from 2011–2013. Controls were recruited within two months of each patient from the same geographic region as the oncology practice and could be a friend, family member, or coworker of the participant, or unrelated. Patients were over-recruited compared to controls to originally test the impact of type of chemotherapy administered (e.g., anthracycline vs. non-anthracycline) on cognitive function [20].

This was a secondary analysis to assess the associations between diabetes and cancer-related fatigue at pre-, post-, and 6 months post-chemotherapy. In this study, participants had to be female, have a diagnosis of stage I to IIIC breast cancer, be scheduled for chemotherapy, be chemotherapy naïve, be at least 21 years old, have no central nervous system or neurodegenerative diseases, have no recent psychiatric illness leading to hospitalization, and have no plan to receive radiation therapy concurrent with their chemotherapy. Controls were matched within five years of age to the patient and met all eligibility criteria except for the cancer diagnosis. Assessments occurred at baseline (within the seven days prior to the first chemotherapy administration), post-chemotherapy (within one month of the last chemotherapy administration), and six months post-chemotherapy (within a one-month range), or at equivalent time points for controls. Participants were excluded from this analysis if diabetes status and/or fatigue data were not available (of 943 total participants, 269 were excluded; 141 patients and 128 controls did not have diabetes status and 24 participants did not have fatigue data at baseline. [Diabetes status was missing for our early participants because it was added to the data collection form after study initiation]).

Assessment of fatigue

Patient-reported fatigue was assessed using the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form (MFSI-SF), which has demonstrated validity among patients with cancer [22]. The MFSI-SF is a 30-item questionnaire that inquires about how true each statement has been over the last week and requests a response on a five-point scale from 0, “Not at all,” to 4, “Very much.” The questionnaire yields a final total score that ranges from −24 to 96 with a greater score indicating greater fatigue. The MFSI-SF assesses five subdomains—general, physical, mental, and emotional fatigue, and vigor; for the first four subdomains, a higher score indicates worse fatigue, whereas a higher vigor score indicates less fatigue.

Assessment of demographics and clinical characteristics including diabetes

Demographic information, clinical characteristics, and lifestyle behaviors were obtained from medical records and/or self-reported via study-specific forms at baseline; self-reported diabetes status was confirmed from medical records if information was available. Diabetes diagnosis was captured as a binary variable (no, not diagnosed with diabetes, or yes, diagnosed with diabetes). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from height and weight measured at baseline and was used as a continuous variable. Exercise was determined from self-reported current exercise habits at baseline (no or yes=physical activity performed purposefully to increase physical fitness 3–5 times per week for 20–60 minutes per session at a level that increases breathing rate and induces sweating). Smoking was categorized using self-reported habits where Never=smoked <100 cigarettes in their lifetime, Former=smoked ≥100 cigarettes in their lifetime but do not smoke currently, and Current=currently in the habit of smoking cigarettes. Current menopausal status was coded categorically as pre-menopausal, peri-menopausal, post-menopausal, or medically induced. Marital status was determined using self-reported living situation (long term relationship [LTR]=married and living with spouse or long-term committed relationship and noLTR=single, widowed, separated, or divorced). Race was self-reported and was analyzed as a binary variable (White or non-White). Education was considered a binary variable (1: <High school, High school graduate, or GED; or 2: At least some college). Hypertension was assessed as a diagnosis of hypertension and was categorized as yes or no. Anxiety was assessed using the Spielberger Trait Anxiety Inventory [23]; depressive symptoms were assessed using a single item, “I feel depressed,” with responses “not at all,” “a little bit,” somewhat,” “quite a bit,” or “very much;” and reading ability, a proxy for cognitive reserve, was assessed using the Wide Range Assessment Test-Fourth Edition (WRAT-4) reading subscale; all were treated as continuous variables [20]. There was <5% missing data for all covariates.

Statistics

All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and JMP Pro (v. 14.1.0, SAS Institute). The distribution of baseline characteristics was evaluated for those with and without diabetes, and the mean (standard deviation) and n (%) are reported for continuous and categorical measures, respectively.

Baseline correlations were conducted to determine the relationships between cancer and diabetes and fatigue before chemotherapy using linear regression. To determine the association between diabetes and cancer-related fatigue as measured using total MFSI score (the primary outcome) over all three time points, a repeated measures model with compound symmetry structure was developed with time (pre-chemotherapy, post-chemotherapy, 6 months post-chemotherapy), group (individuals with cancer receiving chemotherapy or individuals without cancer [control]), diabetes (yes or no), group×time, group×diabetes, time×diabetes, and group×time×diabetes interactions included as fixed effects. Relevant covariates were identified from the literature and defined a priori—age, BMI, exercise, and smoking; these were fixed in the model. Other potential covariates—menopausal status, marital status, race, education, hypertension, anxiety, depression, and cognitive reserve—were added sequentially to assess their effects on the parameter estimate for the influence of diabetes on cancer-related fatigue (βDiab). If the p-value for the covariate was <0.1 and/or the effect estimate for diabetes changed more than 10%, the covariate was retained in the model. Then the predefined comparison cancer (diabetes yes or no) and control (diabetes yes or no) were evaluated from least square mean estimates by linear contrasts and assessed using t-statistics. To assess the effects of diabetes on change in fatigue at post- and 6 months post-chemotherapy, conditional analysis was performed with baseline fatigue score as a covariate in addition to group, diabetes, group×diabetes, and the other covariates as described above. In addition, among patients only, we assessed whether chemotherapy regimen (anthracycline vs. non-anthracycline) was associated with fatigue overall and stratified by diabetes status. We also evaluated the effect of diabetes on the subdomains of the MFSI. For this analysis, a p-value of <0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

Among 674 total participants in this analysis, 439 were patients with cancer and 235 were controls. See Table 1 for a description of the demographics, clinical characteristics, and lifestyle habits of the cohort. Participants were 52.8±10.5 years old, 69.6% were overweight or obese, 73.3% were married or in a long-term relationship, 90.5% were White, and 81.9% had at least some college education. Among patients, 26.2% had stage I cancer, 49.9% had stage II, and 18.7% had stage III. A total of 51 patients with cancer had had a diagnosis of diabetes (11.6%), and 16 controls had diabetes (6.8%, p=0.007, χ2 test).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | Total participants (n=674) | Cancer with diabetes (n=51) | Cancer without diabetes (n=388) | Control with diabetes (n=16) | Control without diabetes (n=219) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age | 52.8±10.5 | 58.6±8.6 | 52.5±10.7 | 53.3±9.8 | 52.0±10.2 |

| Body mass index | |||||

| Underweight or normal weight (<25 kg/m2) | 202 (30.0%) | 5 (9.8%) | 122 (31.4%) | 3 (18.8%) | 72 (33.3%) |

| Overweight (≥25 and <30 kg/m2) | 180 (26.7%) | 6 (11.8%) | 95 (24.5%) | 2 (12.5%) | 77 (35.6%) |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 289 (42.9%) | 40 (78.4%) | 171 (44.1%) | 11 (68.8%) | 67 (31.0%) |

| Regular exercise | |||||

| Yes | 334 (49.6%) | 20 (39.2%) | 180 (46.4%) | 5 (31.3%) | 129 (59.7%) |

| No | 340 (50.4%) | 31 (60.8%) | 208 (53.6%) | 11 (68.8%) | 90 (41.7%) |

| Smoking habits | |||||

| Never | 403 (59.8%) | 34 (66.7%) | 219 (56.4%) | 9 (56.3%) | 141 (65.3%) |

| Former | 198 (29.4%) | 16 (31.4%) | 117 (30.2%) | 6 (37.5%) | 59 (27.3%) |

| Current | 64 (9.5%) | 1 (2.0%) | 47 (12.1%) | 1 (6.3%) | 15 (6.9%) |

| Menopausal status | |||||

| Pre-menopausal | 209 (31.0%) | 4 (7.8%) | 136 (35.1%) | 4 (25.0%) | 65 (30.1%) |

| Post-menopausal | 346 (51.3%) | 34 (66.7%) | 200 (51.5%) | 7 (43.8%) | 105 (48.6%) |

| Peri-menopausal | 67 (9.9%) | 6 (11.8%) | 27 (7.0%) | 3 (18.8%) | 31 (14.4%) |

| Medically induced | 52 (7.7%) | 7 (13.7%) | 25 (6.4%) | 2 (12.5%) | 18 (8.3%) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/long-term relationship | 494 (73.3%) | 33 (64.7%) | 289 (74.5%) | 8 (50.0%) | 164 (75.9%) |

| Single, divorced, widowed, separated | 180 (26.7%) | 18 (35.3%) | 99 (25.5%) | 8 (50.0%) | 55 (25.5%) |

| Race | |||||

| White | 610 (90.5%) | 37 (72.5%) | 354 (91.2%) | 15 (93.8%) | 204 (94.4%) |

| Other | 64 (9.5%) | 14 (27.5%) | 34 (8.8%) | 1 (6.3%) | 15 (6.9%) |

| Education | |||||

| High school/GED or less | 122 (18.1%) | 15 (29.4%) | 84 (21.6%) | 3 (18.8%) | 20 (9.3%) |

| At least some college | 552 (81.9%) | 36 (70.6%) | 304 (78.4%) | 13 (81.3%) | 199 (92.1%) |

| Hypertension | |||||

| Yes | 194 (28.8%) | 35 (68.6%) | 99 (25.5%) | 9 (56.3%) | 51 (23.6%) |

| No | 479 (71.1%) | 16 (31.4%) | 288 (74.2%) | 7 (43.8%) | 168 (77.8%) |

| Baseline anxiety * | 33.4±12.0 | 36.9±13.3 | 36.0±12.3 | 26.8±5.7 | 28.4±9.8 |

| Baseline depression † | 0.58±0.87 | 0.73±0.92 | 0.67±0.91 | 0.75±1.13 | 0.37±0.72 |

| Baseline cognitive reserve ‡ | 63.1±5.4 | 61.5±7.7 | 62.8±5.7 | 64.4±4.1 | 63.8±4.1 |

| Cancer stage | |||||

| I | 15 (29.4%) | 100 (25.8%) | |||

| II | 21 (41.2%) | 198 (51.0%) | |||

| III | 11 (21.6%) | 71 (18.3%) | |||

| Unknown | 4 (7.8%) | 19 (4.9%) | |||

| Chemotherapy regimen | |||||

| Anthracycline | 20 (39.2%) | 182 (46.9%) | |||

| Non-anthracyline | 26 (51.0% | 189 (48.7%) | |||

| Unknown§ | 5 (9.8%) | 17 (4.4%) | |||

| Radiation (Between post-chemotherapy and 6 months post-chemotherapy assessments) | |||||

| Yes | 24 (47.1%) | 206 (53.1%) | |||

| No or unknown | 27 (52.9%) | 182 (46.9%) | |||

Anxiety was measured using the Spielberger Trait Anxiety Inventory

Depression was assessed using a single item, “I feel depressed,” anchored with responses 0, “not at all” to 4, “very much”

Reading ability, a proxy for cognitive reserve, was assessed using the Wide Range Assessment Test-Fourth Edition (WRAT-4) reading subscale

Could not be confirmed from clinic notes

Baseline associations between diabetes and fatigue

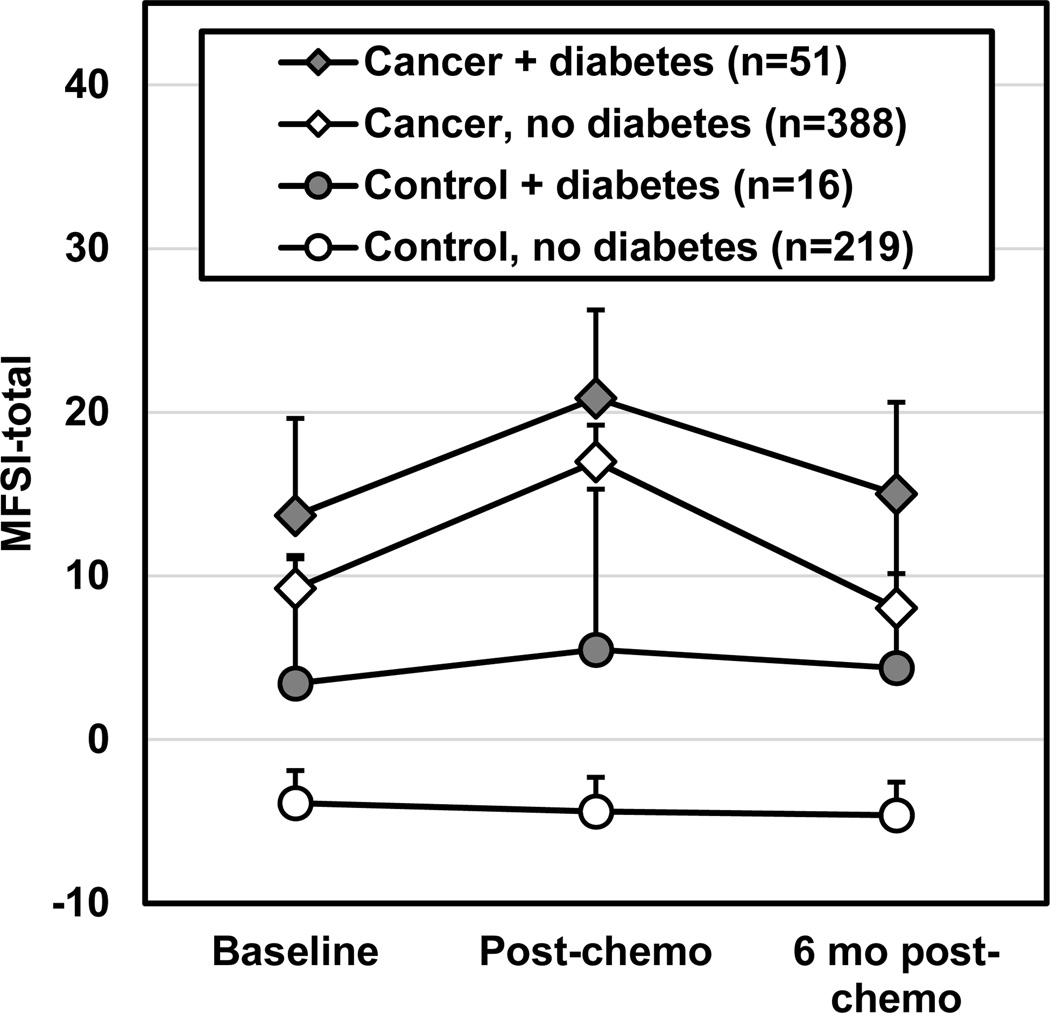

Figure 1 illustrates the unadjusted total MFSI fatigue scores for patients and controls with and without diabetes. At baseline (i.e., before chemotherapy treatment), participants (patients and controls) with diabetes had a greater level of fatigue than those without diabetes (β±SE=4.06±1.70, p=0.017; Supplemental Tables 1A–B). Anxiety explained 35.1% of the variance in fatigue, followed by depressive symptoms (η2p=17.4%). Cancer status explained 2.53% of variance, age explained 1.25%, and diabetes explained 0.88%, which was more than menopausal status, exercise habits, BMI, and smoking status (0.68%, 0.62%, 0.38%, and 0.32%, respectively).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted total score for the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory (MFSI) for patients with cancer (diamonds) and control participants without cancer (circles) from baseline (pre-chemotherapy) to post-chemotherapy and 6 months post-chemotherapy, or equivalent time points for controls. Darkened markers indicate those with a diagnosis of diabetes and open markers are those without diabetes. There is a possible MFSI total score of −24 to 96 with a higher score indicating greater fatigue. Error bars depict 95% confidence interval. Figure was produced in Microsoft Excel 2016.

Longitudinal effect of diabetes on total fatigue and fatigue subdomains

When incorporating data from all three time points, both diabetes (β±SE=6.92±2.59, p=0.008) and cancer (β±SE=14.19±2.59, p<0.001) were significantly associated with worse fatigue (Figure 1). The association of diabetes with worse fatigue held significant after adjusting for age, BMI, exercise habits, smoking habits, marital status, menopausal status, baseline anxiety, and baseline depression as well as several other relevant covariates (Table 2, β±SE=5.17±1.93, p=0.008), and this relationship held true among cancer patients only (β±SE=4.53±1.99, p=0.023) but not controls due to the larger variation in fatigue values among controls (β±SE=5.81±3.27, p=0.076). Diabetes was associated with worse fatigue on all five subdomains of the MFSI and reached statistical significance for general fatigue (p=0.006) and physical fatigue (p=0.003), though differences did not reach statistical significance for mental fatigue (p=0.105), emotional fatigue (p=0.609) or vigor (p=0.061). In patients only, statistical significance was retained for general fatigue (p=0.005) and achieved for mental fatigue (p=0.026). Interaction terms for cancer, diabetes, and time did not research statistical significance (p>0.05). Supplementary Tables 2A–F depict the final models relating diabetes and fatigue with the appropriate covariates for each of the five MFSI subdomains. Fatigue (MFSI total score) increased significantly from baseline to post-chemotherapy within patients with diabetes treated with an anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimen (11.9±4.3, p=0.006) but not for patients with diabetes treated without anthracyclines (4.0±3.7, p=0.280). However, the overall difference in fatigue was not significantly different for patients with an anthracycline-based vs. non-anthracycline-based regimen (p=0.56).

Table 2.

The association between diabetes and cancer-related fatigue*

| All participants (n=674) | Patients only (n=439) | Controls only (n=235) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean difference† | SE | p-value | Mean difference | SE | p-value | Mean difference | SE | p-value | |

| Total MFSI | 5.17 | 1.93 | 0.008‡ | 4.53 | 1.99 | 0.023‡ | 5.81 | 3.27 | 0.076 |

| General fatigue | 1.84 | 0.67 | 0.006‡ | 1.95 | 0.69 | 0.005‡ | 1.73 | 1.12 | 0.125 |

| Physical fatigue | 1.56 | 0.52 | 0.003‡ | 0.91 | 0.53 | 0.089 | 2.23 | 0.88 | 0.012‡ |

| Mental fatigue | 0.85 | 0.52 | 0.105 | 1.19 | 0.53 | 0.026‡ | 0.50 | 0.88 | 0. 572 |

| Emotional fatigue | 0.19 | 0.37 | 0.609 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.377 | 0.36 | 0.61 | 0.954 |

| Vigor | −0.96 | 0.51 | 0.061 | −0.63 | 0.53 | 0.234 | −1.29 | 0.87 | 0.136 |

Models were adjusted for age, race, marital status, education, body mass index, menopausal status, exercise habits, smoking habits, anxiety, depression, and/or cognitive reserve

Mean difference estimates denote the difference between participants with diabetes (n=67 total, n=51 patients and n=16 controls) and participants without diabetes (n=607 total, n=388 patients and n=219 controls)

p<0.05

The effect of diabetes on changes in fatigue over the course of chemotherapy treatment

Next, we performed multivariate regression models to assess the differences in the change in fatigue (MFSI total) from baseline to post-chemotherapy and baseline to 6-months post-chemotherapy among all participants with and without diabetes. We did not observe significant differences in the worsening of fatigue (i.e., change over time) from baseline to post-chemotherapy between those with and without diabetes in all participants (p=0.39) or among patients only (p=0.71). Similarly, we did not observe significant differences in the change in fatigue from baseline to 6 months post-chemotherapy between those with and without diabetes in all participants (p=0.36) or in patients only (p=0.19), suggesting that those with diabetes recovered to a similar level as those without diabetes by 6 months post-chemotherapy treatment (Supplemental Tables 3A–B).

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to investigate the interrelationship between diabetes and cancer-related fatigue using a longitudinal study with both patients undergoing chemotherapy and individuals without cancer. Diabetes was significantly more prevalent among those with vs. without cancer, and diabetes was associated with more severe fatigue to a clinically meaningful degree. Cancer and diabetes both significantly contributed to fatigue in the multivariate model, suggesting that both are independently associated with fatigue. These data demonstrate the absence a ceiling effect of fatigue from the cancer experience—diabetes contributes to fatigue to a similar degree (mean of 4.7 points on the total MFSI scale) for people without cancer and patients with cancer over our observation period (Figure 1). This difference has shown to be clinically important in patients with breast cancer (4.5–10.8 points on the MFSI-SF [24]).

These data corroborate prior findings that cancer is associated with significant fatigue especially after chemotherapy [24–26] and that fatigue is a common symptom among patients with diabetes without cancer [18]. Our data also build upon findings of Hammer et al. from 244 patients with solid tumors undergoing chemotherapy [27], in which patients were categorized into those without diabetes, with pre-diabetes, and with diabetes according to baseline glycosylated hemoglobin concentrations (HbA1c); those with pre-diabetes and diabetes had clinically meaningful greater fatigue in the morning than those without diabetes, and those with diabetes had greater fatigue in the evening, though differences were not statistically significant [27]. Our data, in a larger sample size (n=439 patients with cancer plus 235 controls) and different study design, confirmed this relationship and achieved statistical significance using a different measure of fatigue (MFSI vs. Lee Fatigue Scale).

Our results corroborate previous literature that describes risk factors for fatigue [6] and interventional studies treating fatigue—namely age (age was associated with less fatigue), exercise habits (regular exercise protected against fatigue) [6], baseline anxiety and depression (strong positive correlations) [6, 28], baseline fatigue scores (positive correlation) [29], menopausal status (medically induced menopause was associated with the worst fatigue, followed by peri- and post-menopausal status, followed by pre-menopausal status) [30], BMI (obesity was associated with worse fatigue than normal weight, especially for physical fatigue [6, 12]), and smoking habits (current smoking was associated with worse fatigue) [31]. With the exception of age and menopausal status, these risk factors can all be addressed via behavioral interventions and highlight the potential for lifestyle interventions (e.g., nutrition, exercise, smoking cessation, sleep habits, cognitive interventions) to ameliorate fatigue before and during treatment via direct or indirect effects on metabolic health.

It is being increasingly recognized that metabolic dysfunction, including glucose regulation, plays a role in the etiology and pathophysiology of cancer-related fatigue [32–35]. In a study of patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy, patients experienced a worsening of all aspects of metabolic syndrome including fasting blood glucose, insulin, and HbA1c [36] (fatigue was not reported in this trial). Metabolic dysfunction can stem from cancer- or treatment-related inflammation or neuroendocrine dysfunction, resulting in dysregulation of insulin and other hormones [9]. Metabolic dysfunction can also result from direct effects of chemotherapy on mitochondrial bioenergetics that can reduce ATP energy production, especially in muscle [35]. Exploration into the chemotherapy-induced pathology of mitochondria in the presence and absence of diabetes and function of key metabolic tissues should be the topic of future research.

These data contribute to the important clinical issue regarding simultaneous treatment of cancer and diabetes—because both diabetes and cancer/chemotherapy add to fatigue, glycemic control should continue during chemotherapy treatment. In one study [37], though not all studies (e.g., [38]), adherence to diabetes medications declined from 75% to 25% during treatment for breast cancer, resulting in elevated HbA1c. Low adherence was associated with more hospitalizations [38]. Unfortunately, we did not have access to medication adherence, clinical control of diabetes, or HbA1c, but it is possible that poor diabetes medication adherence could be associated with worse fatigue. In addition, antiemetics and steroids are commonly prescribed in conjunction with chemotherapy and can adversely affect glycemic control. Metformin, a common drug to stabilize blood glucose among people with diabetes, is a promising antineoplastic agent [39, 40] and future research should assess its efficacy to ameliorate supportive care outcomes. Future work should also assess the effects of other anti-diabetic medications on fatigue during and after cancer treatment.

This study is strong in that it is one of the first to specifically explore the relationships between diabetes and cancer-related fatigue by comparing results in patients with cancer to controls. It involves a large sample of patients with breast cancer from community oncology clinics throughout the United States, which allows for generalizability of the results. It also compares patients to individuals who do not have cancer, allowing us to discern the degree of fatigue that is associated specifically with the cancer experience. Our ability to assess fatigue across three important time points during the cancer experience permitted longitudinal analyses through which we can account for the variability in fatigue over time among controls as well as assess changes in fatigue from before chemotherapy to just after and 6 months after chemotherapy.

However, this study has limitations. For example, we could not distinguish between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes mellitus, which have different pathophysiology, nor did we identify people with pre-diabetes, which could have been a substantial proportion of our population; we also did not assess HbA1c or HOMA-IR to validate diabetes status. Additionally, for most controls, diabetes status could not be verified with medical records (as these individuals were not necessarily under clinical care); because people are more likely to inaccurately report a negative diabetes status rather than a positive diagnosis, there could be more controls with undiagnosed diabetes than patients, so that our estimates might be closer to the null than if everyone were properly categorized. Although it was a relatively large study, there were only 16 controls with diabetes, thereby preventing reliable determination of the association between diabetes and fatigue among patients with breast cancer and controls independently (i.e., we could not reliably conduct statistical inference related to the cancer×diabetes interaction term), though we were able to estimate the contributions of both cancer and diabetes to fatigue. Baseline exercise was included as a confounder due to the relationships between inactivity and diabetes [42] and cancer-related fatigue [5, 43]. However, participants might have been misclassified as being inactive despite being active for their occupation, commute, or other reason that is not deliberate exercise. A more precise, time-varying measure of physical activity and inactivity (e.g., accelerometer) would allow more accurate estimates of the effects of physical activity on the relationship between diabetes and fatigue. Despite this, we still observed an association and the true risk of diabetes on fatigue is likely larger than what we observed. Exercise and smoking habits were self-report, and participants might be more inclined to report healthier habits than actual. This would lead to non-differential misclassification and therefore more conservative effect parameters. Further, BMI served to control for excess fat mass, though it is not always an accurate surrogate [44]. A single-item depression question was used to control for the associations between depression and fatigue rather than a reliable and validated depression questionnaire. Lastly, this cohort was predominately White, highly educated, non-smoking women, so our data should not be generalized to other populations without prudence. This was a secondary analysis, so our observed relationships between diabetes and cancer-related fatigue should be tested for replication in future research.

In conclusion, diabetes was twice as prevalent among patients with cancer as non-cancer controls. Also, diabetes was associated with cancer-related fatigue to a clinically meaningful degree before, during, and after chemotherapy treatment for female breast cancer patients after controlling for demographics, clinical characteristics, and lifestyle factors. If these results are true, glycemic control during the cancer experience could reduce the burden of acute and long-term cancer-related fatigue. Future research is needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying fatigue so that we can develop metabolically targeted therapies. In the meantime, it is important for clinicians to encourage metabolic health, perhaps via healthy lifestyle practices (e.g., diet, exercise, healthy sleep habits, not smoking) as soon as possible in the cancer continuum in order to reduce the burden of diabetes on fatigue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following National Cancer Institute (NCI) Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) affiliate sites who participated in this study: Central Illinois, Columbus, Cancer Research Consortium of West Michigan, Dayton, Delaware, Grand Rapids, Greenville, Hematology-Oncology Associates of Central New York, Kalamazoo, Kansas City, Marshfield, Metro Minnesota, Nevada, North Shore, Pacific Cancer Research Consortium, Southeast Cancer Control Consortium, Southeast Clinical Oncology Research Consortium, Upstate Carolina, Virginia Mason, Wichita, Wisconsin NCORP, and Western Oncology Research Consortium.

The results of this study were presented as an oral presentation at the 2021 Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer Annual meeting, with a Young Investigator Award to AK.

Funding:

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) NCI grants UG1CA189961 to KMM and Gary Morrow, T32CA102618 to MCJ and Gary Morrow, R01CA231014 to MCJ, and K07CA221931 to IRK. This publication was supported by funds through the Maryland Department of Health’s Cigarette Restitution Fund Program.

Footnotes

Statements and declarations

Ethics approval:

Ethical approval was obtained from Institutional Review Boards at University of Rochester Cancer Center and each of the 22 recruitment sites prior to enrollment. This trial was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate:

All individual participants included in the study provided informed consent.

Consent for publication:

N/A

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests: Authors report no conflicts of interest.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01382082, first posted June 27, 2011.

Availability of data and code:

The datasets and statistical code generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding and last author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Berger AM, Mooney K, Alvarez-Perez A, Breitbart WS, Carpenter KM, Cella D, Cleeland C, Dotan E, Eisenberger MA, Escalante CP et al. : Cancer-Related Fatigue, Version 2.2015, Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Nat Comp Cancer Netw 2015, 13(8):1012–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Servaes P, Verhagen C, Bleijenberg G: Fatigue in cancer patients during and after treatment: prevalence, correlates and interventions. European Journal of Cancer 2002, 38:27–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Maqbali M, Al Sinani M, Al Naamani Z, Al Badi K, Tanash MI: Prevalence of Fatigue in Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones JM, Olson K, Catton P, Catton CN, Fleshner NE, Krzyzanowska MK, McCready DR, Wong RK, Jiang H, Howell D: Cancer-related fatigue and associated disability in post-treatment cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 2016, 10(1):51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bower JE, Wiley J, Petersen L, Irwin MR, Cole SW, Ganz PA: Fatigue after breast cancer treatment: Biobehavioral predictors of fatigue trajectories. Health Psychol 2018, 37(11):1025–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bower JE: Cancer-related fatigue—mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2014, 11(Oct):597–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horneber M, Fischer I, Dimeo F, Ruffer JU, Weis J: Cancer-related fatigue: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2012, 109(9):161–171; quiz 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofman M, Ryan JL, Figueroa-Moseley CD, Jean-Pierre P, Morrow GR : Cancer-related fatigue: the scale of the problem. Oncologist 2007, 12 Suppl 1:4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saligan LN, Olson K, Filler K, Larkin D, Cramp F, Yennurajalingam S, Escalante CP, del Giglio A, Kober KM, Kamath J et al. : The biology of cancer-related fatigue: a review of the literature. Support Care Cancer 2015, 23(8):2461–2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Higgins CM, Brady B, O’Connor B, Walsh D, Reilly RB: The pathophysiology of cancer-related fatigue: current controversies. Support Care Cancer 2018, 26(10):3353–3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grossberg AJ, Vichaya EG, Gross PS, Ford BG, Scott KA, Estrada D, Vermeer DW, Vermeer P, Dantzer R: Interleukin 6-independent metabolic reprogramming as a driver of cancer-related fatigue. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 88:230–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inglis JE, Janelsins MC, Culakova E, Mustian KM, Lin PJ, Kleckner IR, Peppone LJ: Longitudinal assessment of the impact of higher body mass index on cancer-related fatigue in patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Diabetes Association: CDC National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. In. Arlington, VA; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srokowski TP, Fang S, Hortobagyi GN, Giordano SH: Impact of diabetes mellitus on complications and outcomes of adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27(13):2170–2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Herpt TTW, van de Schans SAM, Haak HR, van Spronsen DJ, Dercksen MW, Janssen-Heijnen MLG: Treatment and outcome in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients with and without prevalent diabetes mellitus in a population-based cancer registry. Journal of Geriatric Oncology 2011, 2(4):239–245. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlin NJ, Dueck AC, Nagl Reddy SK, Verona PM, Cook CB: Implications of breast cancer with diabetes mellitus on patient outcomes and care. Diabetes Management 2014, 4(5):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SY, Kurita N, Yokoyama Y, Seki M, Hasegawa Y, Okoshi Y, Chiba S: Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes mellitus in patients with lymphoma treated with CHOP chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2014, 22(5):1385–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh R, Teel C, Sabus C, McGinnis P, Kluding P: Fatigue in Type 2 Diabetes: Impact on Quality of Life and Predictors. PLoS One 2016, 11(11):e0165652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Storey S, Cohee A, Gathirua-Mwangi WG, Vachon E, Monahan P, Otte J, Stump TE, Cella D, Champion V: Impact of Diabetes on the Symptoms of Breast Cancer Survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 2019, 46(4):473–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janelsins MC, Heckler CE, Peppone LJ, Ahles TA, Mohile SG, Mustian KM, Palesh O, O’Mara AM, Minasian LM, Williams AM et al. : Longitudinal Trajectory and Characterization of Cancer-Related Cognitive Impairment in a Nationwide Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018, 32(36):3231–3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janelsins MC, Heckler CE, Peppone LJ, Kamen C, Mustian KM, Mohile SG, Magnuson A, Kleckner IR, Guido JJ, Young KL et al. : Cognitive Complaints in Survivors of Breast Cancer after Chemotherapy Compared with Age-Matched Controls: An Analysis From a Nationwide, Multicenter, Prospective Longitudinal Study. J Clin Oncol 2017, 35(5):506–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein KD, Jacobsen PB, Blanchard CM, Thors C: Further validation of the multidimensional fatigue symptom inventory-short form. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2004, 27(1):14–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spielberger CD, Sydeman SJ, Owen AE, et al. : Measuring anxiety and anger with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI). In: The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment. edn. Edited by Maruish ME. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999: 993–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan A, Yo TE, Wang XJ, Ng T, Chae JW, Yeo HL, Shwe M, Gan YX: Minimal Clinically Important Difference of the Multidimensional Fatigue Symptom Inventory-Short Form (MFSI-SF) for Fatigue Worsening in Asian Breast Cancer Patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018, 55(3):992–997 e992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams AM, Paterson C, Heckler CE, Barton DL, Ontko M, Geer J, Kleckner AS, Dakhil SR, Mitchell JM, Mustian KM et al. : Cancer-related fatigue, anxiety, and quality of life in breast cancer patients compared to non-cancer controls: A nationwide longitudinal analysis. Breast Cancer Reserach and Treatment in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ancoli-Israel S, Liu L, Marler MR, Parker BA, Jones V, Sadler GR, Dimsdale J, Cohen-Zion M, Fiorentino L: Fatigue, sleep, and circadian rhythms prior to chemotherapy for breast cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer 2006, 14(3):201–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammer MJ, Aouizerat BE, Schmidt BL, Cartwright F, Wright F, Miaskowski C: Glycosylated Hemoglobin A1c and Lack of Association With Symptom Severity in Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy for Solid Tumors. Oncol Nurs Forum 2015, 42(6):581–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh HS, Seo WS: Systematic review and meta-analysis of the correlates of cancer-related fatigue. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2011, 8(4):191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughes A, Suleman S, Rimes KA, Marsden J, Chalder T: Cancer-related fatigue and functional impairment - Towards an understanding of cognitive and behavioural factors. J Psychosom Res 2020, 134:110127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tchen N, Juffs HG, Downie FP, Yi QL, Hu H, Chemerynsky I, Clemons M, Crump M, Goss PE, Warr D et al. : Cognitive function, fatigue, and menopausal symptoms in women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003, 21(22):4175–4183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peppone LJ, Mustian KM, Morrow GR, Dozier AM, Ossip DJ, Janelsins MC, Sprod LK, McIntosh S: The effect of cigarette smoking on cancer treatment-related side effects. Oncologist 2011, 16(12):1784–1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hershey DS: Importance of Glycemic Control in Cancer Patients with Diabetes: Treatment through End of Life. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2017, 4(4):313–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hershey DS, Pierce SJ: Examining patterns of multivariate, longitudinal symptom experiences among older adults with type 2 diabetes and cancer via cluster analysis. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2015, 19(6):716–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammer MJ, Eckardt P, Cartwright F, Miaskowski C: Prescribed Walking for Glycemic Control and Symptom Management in Patients Without Diabetes Undergoing Chemotherapy. Nurs Res 2021, 70(1):6–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang S, Chu S, Gao Y, Ai Q, Liu Y, Li X, Chen N: A Narrative Review of Cancer-Related Fatigue (CRF) and Its Possible Pathogenesis. Cells 2019, 8(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dieli-Conwright CM, Wong L, Waliany S, Bernstein L, Salehian B, Mortimer JE: An observational study to examine changes in metabolic syndrome components in patients with breast cancer receiving neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer 2016, 122(17):2646–2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calip GS, Hubbard RA, Stergachis A, Malone KE, Gralow JR, Boudreau DM: Adherence to oral diabetes medications and glycemic control during and following breast cancer treatment. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015, 24(1):75–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan X, Feng X, Chang J, Higa G, Wang L, Leslie D: Oral antidiabetic drug use and associated health outcomes in cancer patients. J Clin Pharm Ther 2016, 41(5):524–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samuel SM, Varghese E, Varghese S, Busselberg D: Challenges and perspectives in the treatment of diabetes associated breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 2018, 70:98–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans JMM, Donnelly LA, Emslie-Smoth AM, Alessi DR, Morris AD: Metformin and reduced risk of cancer in diabetic patients. BMJ 2005, 330(7503):1304–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schvartsman G, Park M, Liu DD, Yennu S, Bruera E, Hui D: Could Objective Tests Be Used to Measure Fatigue in Patients With Advanced Cancer? J Pain Symptom Manage 2017, 54(2):237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sullivan PW, Morrato EH, Ghushcyan V, Wyatt HR, Hill JO: Obesity, inactivity, and the prevalence of diabetes and diabetes-related cardiovascular comorbidities in the U.S., 2000–2002. Diabetes Care 2005, 28(7):1599–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Servaes P, Verhagen C, Bleijenberg G: Fatigue in cancer patients during and after treatment:prevalence, correlates and interventions. European Journal of Cancer 2002, 38:27–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prentice AM, Jebb SA: Beyond body mass index. Obesity Reviews 2001, 2:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets and statistical code generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding and last author on reasonable request.