Abstract

Background

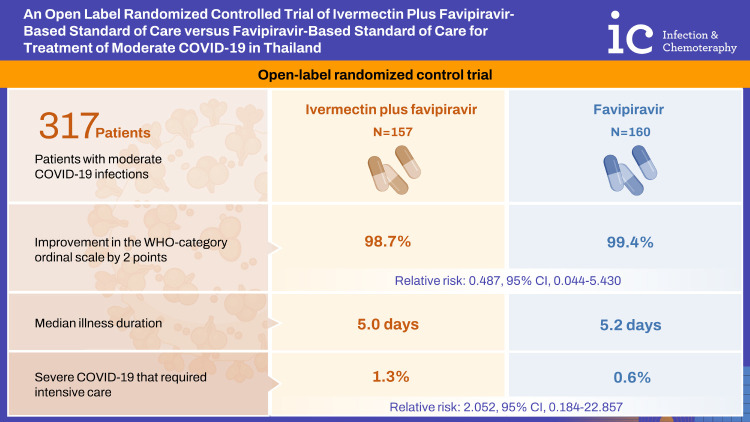

The role of ivermectin in the treatment of moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is controversial. We performed an open label randomized controlled trial to evaluate the role of ivermectin plus favipiravir-based standard of care versus favipiravir-based standard of care for the treatment of moderate COVID-19 infection.

Materials and Methods

An open-label randomized control trial was performed at Thammasat Field Hospital and Thammasat University Hospital from October 1st, 2021 to May 31st, 2022. Patients with moderate COVID-19 infections were randomized to the intervention (ivermectin plus favipiravir-based standard of care) or control group (favipiravir-based standard of care alone). Patients were followed up to 21 days. The primary outcome was the improvement in World Health Organization (WHO) category ordinal scale by 2 points. Secondary outcomes included duration of illness, development of severe COVID-19, and adverse reactions.

Results

There were 157 patients in the intervention and 160 patients in the control group. Characteristics, underlying diseases, and risk factors for severe COVID-19 were comparable in both groups. Improvement in the WHO-category ordinal scale by 2 points was achieved in 98.7% of the intervention group and in 99.4% of the control group (relative risk [RR]: 0.487; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.044-5.430). The median illness duration was 5.0 days (range, 3 - 28 days) in intervention group versus 5.2 days (range, 3 - 28 days) in control group (P = 0.630). Severe COVID-19 that required intensive care occurred in 2 patients (1.3%) in the intervention group and 1 patient (0.6%) in the control group (RR: 2.052; 95% CI: 0.184 - 22.857). No significant difference in serious drug adverse events was seen.

Conclusion

In this study ivermectin plus standard of care was not associated with improvement in the WHO-category ordinal scale, reduced illness duration, or development of severe COVID-19 in moderately ill COVID-19 patients.

Trial Registration

Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: TCTR20220427005

Keywords: Ivermectin, Favipiravir, COVID-19, Treatment, Thailand

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Various drugs have been considered as possible treatment regimens for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) since the start of the global pandemic. Ivermectin, an anti-parasite drug, has the proposed mechanism of inhibiting Importin alpha, which may reduce severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) replication [1]. After initial infection with SARS-CoV-2, the viral replication phase begins and reaches a peak viral load at the beginning of symptom onset [2]. In a previous in vitro study, the inhibitory concentration50 (IC50) of ivermectin to inhibit viral replication was 2 µM. The human lung tissue level of ivermectin was estimated from animal studies to be 2.67-fold higher than plasma [3]. The daily approved dose of ivermectin resulted in an estimated accumulation ratio in lung tissue of 5.35 which would result in lung concentration at 25% of the IC50 [4]. A pharmacokinetic study showed that it required a 35-times higher than the approved dose of ivermectin to reach the IC50 concentration in lung tissue.

The use of ivermectin in COVID-19 treatment was assessed in 18 randomized control trials (RCT) comparing ivermectin with placebo, ivermectin plus doxycycline versus placebo, and ivermectin versus standard of care [5]. The studies included 10 RCTs for hospitalized patients and 8 RCTs for ambulatory patients. Recently, a meta-analysis suggested that ivermectin does not reduce the risk of mechanical ventilation or mortality [6]. In addition, a randomized controlled trial of metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine for early treatment of non-hospitalized adults with COVID-19 infections reported that none of the 3 medications prevented hypoxemia, emergency department visit, hospitalization, or death [7]. Due to inconclusive evidence on the effectiveness of ivermectin, in 2021 the Infection Disease Society of America (IDSA) and the World Health Organization (WHO) both recommended that ivermectin be used for the treatment of COVID-19 infection only within clinical trials [5,8].

In Thailand, the 2022 clinical practice guideline (CPG) [9], recommended favipiravir and supportive treatment as the standard of care for the treatment of patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 infection. If a patient develops severe COVID-19 infection, according to Thai CPG the patient would be referred to the intensive care unit (ICU) and additional therapies provided, including favipiravir, anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., corticosteroids, intravenous methylprednisolone pulse), and immunomodulating agents (e.g., baricitinib, tocilizumab). Controversies exist regarding the role of ivermectin in combination with standard of care, and clinical trials that compare ivermectin versus favipiravir are lacking. We therefore, perform a randomized clinical trial to evaluate the role of favipiravir-based standard of care versus ivermectin plus the favipiravir-based standard of care for treatment of moderate COVID-19 infection in Thailand.

Materials and Methods

1. Study setting and population

This open-label, randomized control trial (RCT) was performed at Thammasat Field Hospital (470-beds) and Thammasat University Hospital (600-beds) from October 1st, 2021 to May 31st, 2022. These hospitals accept patients with mild COVID-19, who were at risk for disease progression, and moderately ill COVID-19 patients. In Thailand, mandatory notification to public health authorities applies to all COVID-19 cases. The standard of care that was provided to all inpatients included supportive care and favipiravir. Patients were admitted at these hospitals for 10 - 14 days from symptom onset or the first positive reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for COVID-19.

The study enrolled Thai patients who were 18 years or older with confirmation of COVID-19 infection by RT-PCR, were symptomatic and met the WHO definition of moderate disease, had a duration of symptoms <5 days, and had provided informed consent [10]. Patients were excluded if they were asymptomatic; did not meet the WHO definition of moderate illness; patients with severe symptoms, including hypoxia requiring oxygen via high flow nasal cannula or mechanical ventilation (WHO classification 5 or above); weight <40 kg or >100 kg; were pregnant or breast feeding; had chronic liver disease; epilepsy requiring barbiturates, benzodiazepine, or valproic acid for treatment; liver injury grade 2 or above (alanine transaminase [ALT] >3 × upper normal limits); who could not tolerate oral medications; or were enrolled in another medication treatment study.

Patients who met the above criteria were cluster randomized weekly into the intervention or control group in a 1:1 ratio, using a computer-generated technique. The intervention group received the standard of care including supportive care and favipiravir therapy (60 mg/kg/day on the first day then 20 mg/kg/day on days 2 - 5) and ivermectin (400 μg/kg/day for 5 days), while the control group received only supportive care treatment, which included anti-inflammatory agents, if indicated, and favipiravir (dose/duration as above). The patient’s clinical history, anthropometric measurements, history of vaccination, blood chemistries, including liver function tests, and chest radiography were collected at baseline. All patients self-reported their level of function based on WHO classification. [11] We also follow CONSORT 2010 checklist protocol for randomized control trial as shown in the Supplementary Table 1.

2. Ethics statement

This study is registered with Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR) (TCTR number: TCTR20220427005). The study was approved by The Human Research Ethics Committee of Thammasat University (Medicine) (MTU-EC-IM-0-239/64). All participants provided informed consent.

3. Data collection and outcome measures

Patients were followed at day 3rd, 7th, 14th, and 21st after the start of treatment or until their symptom resolved. Complete blood count, liver function tests, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine, were collected on hospital days 3 - 5 and on hospital days 7 - 10. All medications were dispensed by the patients’ nurses. All study related adverse events (AEs) were reviewed by an independent data and safety monitoring board. The primary outcome was an improvement in the WHO-category ordinal scale by 2 points. Secondary outcomes assessed include the duration of illness, and development of severe COVID-19 requiring ICU admission. Adverse events were evaluated and graded according to the common terminology criteria for adverse events, version 5.0 [12].

Sample size calculations were based on a non-inferiority trial. Before the trial started, the case fatality rate at Thammasat University was about 1.0%. We felt that this rate was too low for mortality to be the primary endpoint in our study. In a previous study and from our local observation data of COVID-19 patients with moderate disease, the estimated proportion of patients who develop clinical progression in the control group was expected at 18% [13]. The lower bound, the non-inferiority margin was set at 10. This study required at least 145 patients in each group to provide a two-sided type I error of 0.05 with 80.0% power.

4. Statistical analysis

Primary analyses were performed based on a modified intention to treat, whereby randomized patients in the intervention group received at least 1 dose of ivermectin, and the control group was followed until the primary outcome was reached, had a serious AE, or ask to be withdrawn. Descriptive data were expressed as frequencies, percentages, or means with standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise stated. Categorical data were analyzed using the Fisher exact test, continuous variables were tested using t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. The primary and categorical secondary outcome measures were estimated using relative risk (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) <0.05 considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for MAC, (version 23, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Interim analyses were conducted monthly to evaluate the primary outcome and AEs. The early stopping was considered if there were significant differences in serious AEs in the intervention compared to the control group.

Results

1. Patients’ characteristics

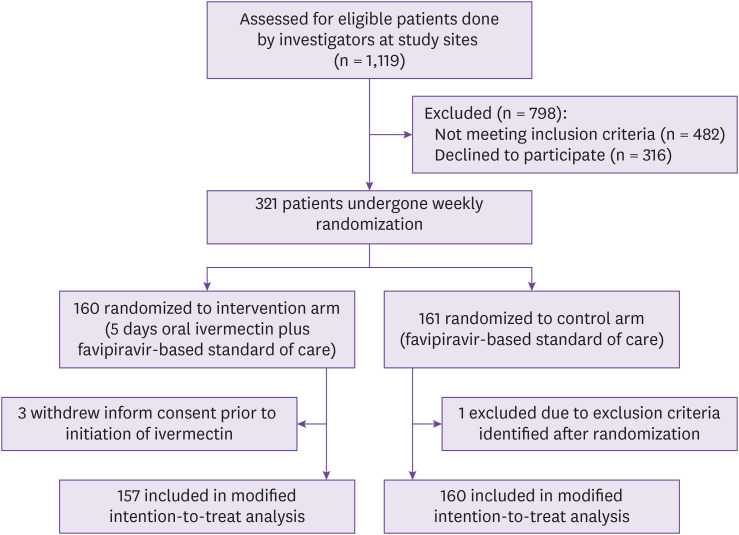

Between October 1st, 2021 to May 31st, 2022, 321 patients were enrolled and randomized. One patient was excluded after randomization. Three out of 320 (0.9%) patients withdrew consent before ivermectin treatment was initiated. The modified intention-to-treat population for the primary analysis included 317 patients with 157 in the intervention group and 160 in the control group (Fig. 1). Except for 3 out of 157 (1.9%) patients who discontinued medication due to its side effects, all other patients completed at least 5 doses of ivermectin.

Figure 1. Screening, enrollment, randomization, and treatment assignment.

Baseline demographics and characteristics of patients were well balanced between groups. (Table 1). The mean (SD) age was 47.4 years (± 20.2) with 196 out of 317 (61.8%) being women, 198 out of 317 (62.5%) patients were fully vaccinated with 2 doses of COVID-19 vaccines. The majority of participants had hypertension (31.5%), dyslipidemia (22.4%), and diabetes mellitus (16.7%). Fifty-five out of 317 (17.4%) patients were active smokers. The mean (SD) duration of symptoms at enrollment was 2.9 (± 1.5days) days. The most common symptoms were cough (70.0%), fever (58.0%), and runny nose (45.1%). One hundred and twenty-nine out of 317 (40.7%) patients had an abnormal chest radiograph at baseline.

Table 1. Comparison of baseline epidemiology and clinical characteristics.

| Characteristics | Intervention (N = 157) | Control (N = 160) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 47.9 (21.5) | 46.9 (19.0) | 0.661 | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 98 (61.3) | 98 (62.4) | 0.830 | |

| Anthropometrics | ||||

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 63.4 (13.4) | 63.5 (13.5) | 0.923 | |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 24.1 (4.8) | 24.4 (5.0) | 0.638 | |

| COVID-19 vaccination, n (%) | ||||

| Complete 2 doses of vaccine | 105 (66.9) | 93 (58.1) | 0.108 | |

| Disease severity at enrollment, n (%) | ||||

| WHO classification 0 - 2 | 4 (2.5) | 2 (1.3) | 0.164 | |

| WHO classification 3 - 4 | 153 (97.5) | 158 (98.8) | 0.164 | |

| O2 baseline (SD) | 97.1 (5.6) | 96.6 (9.8) | 0.544 | |

| Day of symptoms at enrollment, mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.3) | 2.9 (1.7) | 0.890 | |

| No limit activity | 111 (70.7) | 110 (68.8) | 0.264 | |

| Limit strenuous activity | 41 (26.1) | 41 (25.6) | 0.264 | |

| Limit light activity | 5 (3.2) | 5 (3.1) | 0.264 | |

| Dyspnea at rest | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.5) | 0.264 | |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 55 (35.0) | 45 (28.1) | 0.186 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 40 (25.5) | 31 (19.4) | 0.193 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 32 (20.4) | 21 (13.1) | 0.083 | |

| Asthma/COPD | 3 (1.9) | 5 (3.1) | 0.491 | |

| Current smoking | 34 (21.7) | 21 (13.1) | 0.132 | |

| Othersa | 25 (15.9) | 19 (11.9) | 0.300 | |

| Symptom, n (%) | ||||

| Cough | 112 (71.3) | 110 (68.8) | 0.615 | |

| Fever | 96 (61.1) | 88 (55.0) | 0.268 | |

| Runny nose | 68 (43.3) | 75 (46.9) | 0.524 | |

| Myalgia | 39 (24.8) | 51 (31.9) | 0.165 | |

| Loss sense of smell | 21 (13.4) | 23 (14.4) | 0.797 | |

| Dyspnea | 17 (10.8) | 21 (13.7) | 0.529 | |

| Othersb | 20 (12.7) | 17 (10.6) | 0.558 | |

| Imaging and laboratory parameters at enrollment | ||||

| Abnormal chest radiography | 67 (42.7) | 62 (38.8) | 0.477 | |

aChronic kidney disease, gouty arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, cardiac disease.

bSore throat, rash, lethargy, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting.

SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; WHO, World Health Organization; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The study was conducted from October 1st, 2021 to May 31st, 2022. From the outbreak variant timeline in Thailand, half of the patients were recruited during the Delta wave, and the other half were recruited during the Omicron wave.

2. Treatment outcome

Among the 317 patients, three out of 317 (0.9%) patients progressed to severe disease during the study period. Two out of 157 (1.3%) patients received ivermectin plus standard of care and one out of 160 (0.6%) patients received standard of care alone (RR: 2.052; 95% CI: 0.184 - 22.857; P = 0.551) (Table 2). Similar results were observed in the intention-to-treat analysis.

Table 2. Outcomes analysis.

| Outcomes | Intervention (N = 157) | Control (N = 160) | RR; 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome, n (%) | |||||

| Clinical improvement by 2 WHO ordinal scale | 155 (98.7) | 159 (99.4) | 0.487; 0.044 - 5.430 | 0.551 | |

| Secondary outcomes, n (%) | |||||

| Patients who had mechanical ventilation | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 1.019; 0.063 - 16.439 | 0.989 | |

| Patients who admitted to ICU | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | 2.052; 0.184 - 22.857 | 0.551 | |

| All-cause in-hospital mortalitya | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 1.019; 0.063 - 16.439 | 0.989 | |

aCOVID-19 pneumonia and ventilator associated pneumonia.

RR, relative risk; CI confidence interval; WHO, world health organization; ICU, intensive care unit.

There were no significant differences between intervention and control groups for all the pre-specified secondary outcomes (Table 2). There was both one patient in the intervention and control group who required mechanical ventilation (0.6%; P =0.989). ICU admission occurred in 2 out of 157 (1.3%) patients in the intervention group vs. 1 out of 160 patients (0.6%) in the control group (RR: 2.052; 95% CI: 0.184 - 22.857; P = 0.551). Each intervention and control group had 1 death [0.6% vs. 0.6%; RR: 95% CI: 1.019; 0.063 - 16.439; P = 0.989]. One patient in intervention group died from COVID-19 pneumonia while 1 patient in the control group died from ventilator associated pneumonia. The time to resolution of symptoms was comparable between both groups (5.0 vs. 5.2 days; P = 0.630). There was no significant difference in the incidence of disease complications and the requirement for supplementary oxygen treatment (Table 2).

There was a total of 47 AEs (Table 3), with 27 out of 47 (57.4%) occurring in the intervention group and 20 out of 47 (42.6%) in the control group. Dizziness (4.7%) and diarrhea (3.5%) were the most common AEs. There were 2 serious adverse events (both drug induced liver injury) in the intervention group. Three out of 157 (1.9%) patients were withdrawn from the study owing to AEs (e.g., drug induced liver injury, nausea, and vomiting); all were from the intervention group. There was no serious AE in the control group. The majority of AEs (45/47; 95.7%) were grade 1 and resolved within the study period.

Table 3. Comparison of adverse drug reaction (ADR).

| Adverse drug reaction | Intervention (N = 157) | Control (N = 160) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non serious ADR, n (%) | ||||

| Dizziness and vertigo | 10 (6.4) | 5 (3.1) | 0.174 | |

| Diarrhea | 6 (3.8) | 5 (3.1) | 0.735 | |

| Nausea and vomiting | 3 (1.9) | 1 (0.6) | 0.305 | |

| Constipation | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.5) | 0.721 | |

| Palpitation | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 0.989 | |

| Othersa | 2 (1.3) | 4 (2.5) | 0.423 | |

| Serious ADR, n (%) | ||||

| Drug induced liver injury | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.152 | |

aHiccup, palpitation, urticaria, bloating, sleepiness.

Discussion

There are several important findings from our study. First, we found that patients with moderate COVID-19 infection who received ivermectin plus favipiravir-based standard of care had a similar outcome compared to those who received favipiravir-based standard of care alone. Both regimens yielded similar outcomes in relation to improve the clinical progression of moderately ill COVID-19 patients as measured by the WHO-ordinal scale, time to resolution of symptoms, the proportion of patients who were referred to the intensive care unit, on a mechanical ventilator, and all causes of mortality. To our knowledge, this is the first study that compares the ivermectin plus favipiravir-based standard of care to the favipiravir-based standard of care alone which is a standardized treatment regimen in Thailand for moderately ill COVID-19 patients. Second, our data confirm that high dose ivermectin for the treatment of moderately ill COVID-19 patients was relatively safe. However, there is a need to monitor liver function tests as patients may develop drug-induced liver injury.

Favipiravir is an antiviral medication that has a proposed mechanism against COVID-19 by inhibiting RNA dependent RNA polymerase, thus inhibiting viral replication [14,15]. An early study in 2020 from Türkiye showed that early initiation of favipiravir within the first 72hrs reduced fatality in patients with COVID-19 [16]. In Thailand, a multicenter, observational study of favipiravir for the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients reported 66.7% of patients had clinical improvement by hospital day 7 using favipiravir therapy. A lower dose (<45 mg/kg) of favipiravir was independently associated with a lack of clinical improvement by day 7 [17]. Based upon that study, Thailand adopted using favipiravir at a dose of 60 mg/kg/day on the first day and then 20 mg/kg/day on 2nd - 5th day as a standard treatment regimen for patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 infection.

Ivermectin inhibits viral replication and thus may result in reduction in the disease severity and duration of illness. The approved dose of ivermectin for treatment of strongyloidiasis is 200-μg/kg, but a higher dose of ivermectin (400 μg/kg) was used in phase III study of dengue fever that showed no significant increase in adverse drug reactions. The first RCT to compare ivermectin with hydroxychloroquine among patients with COVID-19 pneumonia was performed using ivermectin at a single dose (~200 μg/kg/day); this study reported no significant improvement in number of in hospital days, respiratory deterioration or mortality [18]. Two RCTs using ivermectin at a single dose of 400 μg/kg and 600 μg/kg/day for 5 days [19,20], which is 2 - 3 times higher than the standard approved dose, yielded significant reduction in COVID-19 viral load. However, even though one RCT showed significant reduction in cough and anosmia symptom, both RCTs showed no significant mortality benefit. Additionally, three RCTs of ivermectin at a dose of 400 μg/kg/day compared to placebo or standard of care among mild COVID-19 patients showed no significantly difference in time to resolution and clinical progression of COVID-19 symptoms [21,22,23,24]. Similar to previous studies, our trial used an ivermectin dose of 400 μg/kg daily for 5 days in conjunction with favipiravir-based standard of care therapy. Our results contributed to the body of evidence suggesting that higher dose of ivermectin plus favipiravir-based standard of care for treatment did not improve the symptom as measured by WHO-category ordinal scale. Furthermore, there were no significant improvements in the duration of illness, requirement for intensive care admission, and all-cause mortality. Our study also confirmed that the use of ivermectin at 400 μg/kg/day for 5 days did not significantly increase serious adverse drug reactions.

There are some limitations in this study. First, because the nature of single center study and the relatively small sample size, it is possible that these limitations may lead to insignificant outcome in clinical improvement as measured by the WHO category ordinal scale by 2 points. However, our study is consistent with previous RCTs [21,22]. Second, the open label trial design might contribute to bias towards intervention group in terms of efficacy and adverse drug events. Third, this study was conducted during Delta and Omicron variant waves, therefore there might be a variation in epidemiology of patient populations, vaccination uptake and severity of diseases during the entire study period.

In conclusion, our data support existing evidence and suggest no additional benefit from adding ivermectin to a favipiravir-based standard therapy for treatment of moderate COVID-19 infection. Our study also confirms that higher dose of ivermectin (400 μg/kg/day for 5 days) did not lead to significant serious AEs, but a careful evaluation of liver function test should be considered. The study finding does not support adding ivermectin to favipiravir-based standard of care in moderately ill COVID-19 patients.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was partially supported by Thammasat University Research Grant (TUFT14/2565).

Ethical approval and consent to participate: MTU-EC-IM-0-239/64

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest.

- Conceptualization: PS, AA, KJ.

- Data curation: PS, OS, TP, CM.

- Formal analysis: AA, KJ, DKW, DJW.

- Funding acquisition: AA.

- Investigation: PS, OS, TP, CM.

- Methodology: AA, JK, DKW, DJW.

- Project administration: AA.

- Validation: PS, AA, JK, OS, TP, CM, DKW, DJW.

- Writing – original draft: PS, AA, JK, OS, TP.

- Writing – review & editing: PS, AA, KJ, OS, TP, CM, DKW, DJW.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The CONSORT 2010 checklist for ‘An Open Label Randomized Controlled Trial of Ivermectin Plus Favipiravir-Based Standard of Care versus Favipiravir-Based Standard of Care for Treatment of Moderate COVID-19 in Thailand

References

- 1.Wagstaff KM, Sivakumaran H, Heaton SM, Harrich D, Jans DA. Ivermectin is a specific inhibitor of importin α/β-mediated nuclear import able to inhibit replication of HIV-1 and dengue virus. Biochem J. 2012;443:851–856. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cevik M, Kuppalli K, Kindrachuk J, Peiris M. Virology, transmission, and pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. BMJ. 2020;371:m3862. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lifschitz A, Virkel G, Sallovitz J, Sutra JF, Galtier P, Alvinerie M, Lanusse C. Comparative distribution of ivermectin and doramectin to parasite location tissues in cattle. Vet Parasitol. 2000;87:327–338. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(99)00175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmith VD, Zhou JJ, Lohmer LRL. The approved dose of ivermectin alone is not the ideal dose for the treatment of COVID-19. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;108:762–765. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhimraj A, Morgan RL, Shumaker AH, Baden L, Cheng VC, Edwards KM, Gallagher JC, Gandhi RT, Muller WJ, Nakamura MM, O'Horo JC, Shafer RW, Shoham S, Murad MH, Mustafa RA, Sultan S, Falck-Ytter Y. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines on the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2022; Version 10.1.1. [Accessed 1 March 2022]. Available at: https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-treatment-and-management/

- 6.Marcolino MS, Meira KC, Guimarães NS, Motta PP, Chagas VS, Kelles SMB, de Sá LC, Valacio RA, Ziegelmann PK. Systematic review and meta-analysis of ivermectin for treatment of COVID-19: evidence beyond the hype. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22:639. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07589-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bramante CT, Huling JD, Tignanelli CJ, Buse JB, Liebovitz DM, Nicklas JM, Cohen K, Puskarich MA, Belani HK, Proper JL, Siegel LK, Klatt NR, Odde DJ, Luke DG, Anderson B, Karger AB, Ingraham NE, Hartman KM, Rao V, Hagen AA, Patel B, Fenno SL, Avula N, Reddy NV, Erickson SM, Lindberg S, Fricton R, Lee S, Zaman A, Saveraid HG, Tordsen WJ, Pullen MF, Biros M, Sherwood NE, Thompson JL, Boulware DR, Murray TA COVID-OUT Trial Team. Randomized trial of metformin, ivermectin, and fluvoxamine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:599–610. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2201662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO advises that ivermectin only be used to treat COVID-19 within clinical trials. 2021. [Accessed 1 March 2022]. Avaliable at: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/who-advises-that-ivermectin-only-be-used-to-treat-covid-19-within-clinical-trials .

- 9.Sirijatuphat R, Suputtamongkol Y, Angkasekwinai N, Horthongkham N, Chayakulkeeree M, Rattanaumpawan P, Koomanachai P, Assanasen S, Rongrungruang Y, Chierakul N, Ratanarat R, Jitmuang A, Wangchinda W, Kantakamalakul W. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and treatment outcomes of patients with COVID-19 at Thailand’s university-based referral hospital. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:382. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06081-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization (WHO) Living guidance for clinical management of COVID-19. 2021. [Accessed 17 April 2022]. p. 24. Avaliable at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-clinical-2021-2 .

- 11.Working WHO. Group on the Clinical Characterisation and Management of COVID-19 infection. A minimal common outcome measure set for COVID-19 clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:e192–e197. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30483-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 5.0. 2017. [Accessed 21 April 2022]. Avaliable at: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcae_v5_quick_reference_5x7.pdf .

- 13.Chen SL, Feng HY, Xu H, Huang SS, Sun JF, Zhou L, He JL, Song WL, Wang RJ, Li X, Fang M. Patterns of deterioration in moderate patients with COVID-19 from Jan 2020 to Mar 2020: a multi-center, retrospective cohort study in China. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020;7:567296. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.567296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Özlüşen B, Kozan Ş, Akcan RE, Kalender M, Yaprak D, Peltek İB, Keske Ş, Gönen M, Ergönül Ö. Effectiveness of favipiravir in COVID-19: a live systematic review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;40:2575–2583. doi: 10.1007/s10096-021-04307-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SB, Ryoo S, Huh K, Joo EJ, Kim YJ, Choi WS, Kim YJ, Yoon YK, Heo JY, Seo YB, Jeong SJ, Park DA, Yu SY, Lee HJ, Kim J, Jin Y, Park J, Peck KR, Choi M, Yeom JS Korean Society of Infectious Diseases (KSID) Revised Korean Society of Infectious Diseases/national evidence-based healthcarea collaborating agency guidelines on the treatment of patients with COVID-19. Infect Chemother. 2021;53:166–219. doi: 10.3947/ic.2021.0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karatas E, Aksoy L, Ozaslan E. Association of early favipiravir use with reduced COVID-19 fatality among hospitalized patients. Infect Chemother. 2021;53:300–307. doi: 10.3947/ic.2020.0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rattanaumpawan P, Jirajariyavej S, Lerdlamyong K, Palavutitotai N, Saiyarin J. Real-world effectiveness and optimal dosage of favipiravir for treatment of COVID-19: results from a multicenter observational study in Thailand. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022;11:805. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11060805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caly L, Druce JD, Catton MG, Jans DA, Wagstaff KM. The FDA-approved drug ivermectin inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2020;178:104787. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chowdhury A, Shahbaz M, Karim M, Islam J, Dan G, Shuixiang H. A comparative study on ivermectin-doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine-azithromycin therapy on COVID-19 patients. EJMO. 2021;5:63–70. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed S, Karim MM, Ross AG, Hossain MS, Clemens JD, Sumiya MK, Phru CS, Rahman M, Zaman K, Somani J, Yasmin R, Hasnat MA, Kabir A, Aziz AB, Khan WA. A five-day course of ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19 may reduce the duration of illness. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:214–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chaccour C, Casellas A, Blanco-Di Matteo A, Pineda I, Fernandez-Montero A, Ruiz-Castillo P, Richardson MA, Rodríguez-Mateos M, Jordán-Iborra C, Brew J, Carmona-Torre F, Giráldez M, Laso E, Gabaldón-Figueira JC, Dobaño C, Moncunill G, Yuste JR, Del Pozo JL, Rabinovich NR, Schöning V, Hammann F, Reina G, Sadaba B, Fernández-Alonso M. The effect of early treatment with ivermectin on viral load, symptoms and humoral response in patients with non-severe COVID-19: A pilot, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;32:100720. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reis G, Silva EASM, Silva DCM, Thabane L, Milagres AC, Ferreira TS, Dos Santos CVQ, Campos VHS, Nogueira AMR, de Almeida APFG, Callegari ED, Neto ADF, Savassi LCM, Simplicio MIC, Ribeiro LB, Oliveira R, Harari O, Forrest JI, Ruton H, Sprague S, McKay P, Guo CM, Rowland-Yeo K, Guyatt GH, Boulware DR, Rayner CR, Mills EJ TOGETHER Investigators. Effect of early treatment with ivermectin among patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1721–1731. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2115869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.López-Medina E, López P, Hurtado IC, Dávalos DM, Ramirez O, Martínez E, Díazgranados JA, Oñate JM, Chavarriaga H, Herrera S, Parra B, Libreros G, Jaramillo R, Avendaño AC, Toro DF, Torres M, Lesmes MC, Rios CA, Caicedo I. Effect of ivermectin on time to resolution of symptoms among adults with mild COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325:1426–1435. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.3071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim SCL, Hor CP, Tay KH, Mat Jelani A, Tan WH, Ker HB, Chow TS, Zaid M, Cheah WK, Lim HH, Khalid KE, Cheng JT, Mohd Unit H, An N, Nasruddin AB, Low LL, Khoo SWR, Loh JH, Zaidan NZ, Ab Wahab S, Song LH, Koh HM, King TL, Lai NM, Chidambaram SK, Peariasamy KM I-TECH Study Group. Efficacy of ivermectin treatment on disease progression among adults with mild to moderate COVID-19 and comorbidities: The I-TECH randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:426–435. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The CONSORT 2010 checklist for ‘An Open Label Randomized Controlled Trial of Ivermectin Plus Favipiravir-Based Standard of Care versus Favipiravir-Based Standard of Care for Treatment of Moderate COVID-19 in Thailand