Abstract

Objective: This quick literature review aimed to organize information on the detailed components of total pain in older people with advanced dementia in a holistic manner.

Materials and Methods: The authors analyzed qualitative data from relevant clinical guidelines or textbooks, focusing on certain types of pain and distress in older people with advanced dementia, followed by an expert panel review by research team members. In the search, the authors defined a person with advanced dementia as having a functional assessment staging tool scale score greater than or equal to six.

Results: The model covered a wide variety of pain, from physical pain to dementia-related psychological and spiritual aspects of total pain, including living environment change, stigma, discrimination, lack of communication and understanding, loss of sense of control and dignity, and cultural distress. It also identified physical appearance as an important factor in dying with dignity, as established by existing research on individuals with incurable cancers.

Conclusion: The conceptual model of total pain in people with advanced dementia is expected to help turn healthcare professionals’ attention to physical, psychological, social, and spiritual contributors to total pain in advanced dementia.

Keywords: palliative care, end-of-life care, total pain, dementia, dignity

Introduction

Dame Cicely Saunders first articulated the theory of “total pain” to describe the sum of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual suffering experienced by patients with advanced diseases such as heart failure, respiratory failure, and cancer1). The theory suggests that the combination of and interplay between these elements results in a “total pain” experience that is individualized and specific to each patient’s particular situation2). Good pain management is a central pillar of good palliative care, and the assessment of total pain is a critical part of management. Without a clear conceptualization of total pain in patients with advanced diseases, the patient’s situation may not be accurately elicited2).

The importance of assessing and managing total pain in cancer patients has been widely recognized by both clinicians and researchers. However, cancer represents only a fraction of the serious diseases3). While current guidelines generally recommend palliative care for other diseases, such as heart failure, dementia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the assessment and management of total pain in patients dying from non-cancer causes has received limited focus. Consequently, a key question remains: Can the concept of total pain for cancer patients be translated to other patient populations?

Among non-cancer serious diseases, the palliative care needs of dementia patients have recently been recognized because it has been established over recent decades that the clinical course of advanced dementia, including uncomfortable symptoms such as pain, is similar to that experienced by older patients with cancer and other terminal conditions4). Furthermore, older people with dementia often feel confused, anxious, or frustrated, and the person-centered approach to dementia treatment uses positive reinforcement to meet their emotional needs and help them rediscover their identity4, 5). Thus, the concept of total pain may provide a basis for palliative care need assessment to intervene successfully with people with advanced dementia.

A complete and thorough appreciation of all possible components of total pain is needed to apply the total pain theory to palliative care research and practice in advanced dementia. However, few studies have focused on the total pain experienced by older people with advanced dementia through a multidimensional lens. Therefore, this quick literature review aimed to organize information on the detailed components of total pain in older people with advanced dementia in a holistic manner.

Materials and Methods

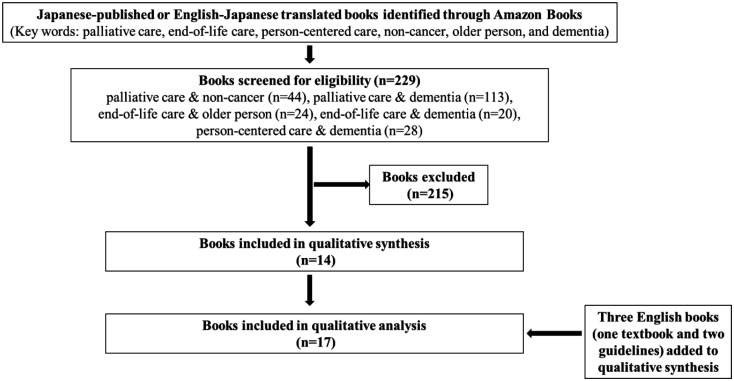

The authors used a convenient sampling approach to obtain relevant information for synthesizing available clinical guidelines or textbooks focusing on certain types of pain and distress in older people with advanced dementia. Details of the relevant literature are presented in Table 1. A flow diagram of the study is shown in Figure 1. A brief search was performed on Amazon Books for all popular Japanese-published or English-Japanese translated books on palliative care for older people with advanced dementia available as of April 2021, regardless of the year of publication, using one or more of the following keywords: palliative care, end-of-life care, person-centered care, non-cancer, older person, and dementia. The titles and customer reviews of the retrieved books were screened for eligibility, and any books demonstrating components of total pain in people with advanced dementia were included. The authors also included an English textbook (Book No. 3) and two English guidelines (Books 8 and 12) for palliative care for older people, regardless of dementia. Finally, to enhance the search for spiritual aspects of total pain in older people with advanced dementia, the authors referred to the first author’s (YH) previous papers on this topic.

Table 1. Details of the analyzed literature analyzed.

| Book No. | Author/Editor | Title | Literature category | Language | Publisher | Year of publication | ISBN/ASIN | Total number of pages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Benson S | The care assistant’s guide to working with people with dementia | Textbook | English-Japanese translation | Tsutsui Shobo | 2007 | 488720535X | 269 |

| 2 | Brooker D | Person-centered dementia care: making services better | Textbook | English-Japanese translation | Creates Kamogawa | 2010 | 486342048X | 242 |

| 3 | Henderson ML, et al. | Improving nursing home care of the dying: a training manual for nursing home staff | Textbook | English | Springer Publishing | 2003 | 826119255 | 208 |

| 4 | Hirahara S & Kuwata M | Palliative care for dementia: end of life care for all | Textbook | Japanese | Nanzando | 2019 | 4525381612 | 279 |

| 5 | Hughes JC & Boldwin C | Ethical issues in dementia care: making difficult decisions | Textbook | English-Japanese translation | Creates Kamogawa | 2017 | 4863421990 | 168 |

| 6 | Kitwood T | Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first | Textbook | English-Japanese translation | Creates Kamogawa | 2017 | 4863422075 | 272 |

| 7 | Kitwood T & Bredin K | Person to Person: Guide to the care of those with failing mental powers | Textbook | English-Japanese translation | Bricolage | 2018 | 4907946147 | 168 |

| 8 | Kuebler KK, et al. | End of life care: Clinical practice guideline | Guideline | English | W.B. Saunders | 2002 | 721684521 | 492 |

| 9 | Kuwata M & Yuasa M | A practical guide to end of life care for older people (Vol. 1) | Textbook | Japanese | Chuohoki Publishing | 2016 | 4805854006 | 215 |

| 10 | Kuwata M & Yuasa M | A practical guide to end of life care for older people (Vol. 2) | Textbook | Japanese | Chuohoki Publishing | 2016 | 4805854014 | 227 |

| 11 | Loveday B | Leadership for person-centered dementia care | Textbook | English-Japanese translation | Community Life Support Center | 2018 | 4904874609 | 159 |

| 12 | Martin GA & Sabbagh MN | Palliative care for advanced Alzheimer’s and dementia: guidelines and standards for evidence-based care | Guideline | English | Springer Publishing | 2010 | 826106757 | 313 |

| 13 | May H, et al. | Enriched care planning for people with dementia | Textbook | English-Japanese translation | Creates Kamogawa | 2016 | 4863421745 | 264 |

| 14 | Nagae H | Empathetic advance care planning: a practical guide for community-based networks of health care, medical and welfare professionals | Textbook | Japanese | Japanese Nursing Association Publishing | 2018 | 4818021202 | 272 |

| 15 | National Advisory Committee | A guide to end-of-life care for seniors | Guideline | English-Japanese translation | Kosei Kagaku Kenkyusho | 2001 | 4905690781 | 273 |

| 16 | Perrin T & May H | Wellbeing in dementia | Textbook | English-Japanese translation | Elsevier Japan | 2007 | 4860348729 | 209 |

| 17 | Robert Twycross R & Wilcock A | Introducing palliative care (fifth edition) | Textbook | English-Japanese translation | Igaku Shoin Medical Publishers | 2018 | 4260035509 | 412 |

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

The first author (YH), a geriatrician with extensive experience in qualitative research, extracted relevant information and identified key components of total pain in older people with advanced dementia through a manual bibliography search, followed by an expert panel review by the research team members with dementia expertise, including the other authors (TY, SH, JO, MK, and HM). In the search, the authors defined a person with advanced dementia as having a functional assessment staging tool scale score greater than or equal to six. An inductive and deductive content analysis approach was used to organize the qualitative data into the concept of total pain6). The second author (TM), a healthcare communication designer, created an illustration to focus readers’ attention on psychosocial and spiritual pain, as well as physical pain.

Results

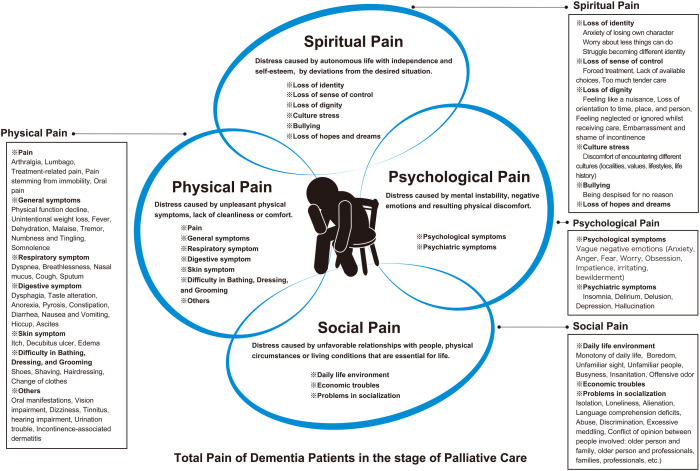

The model produced from the component extraction results is illustrated in Figure 2. The model covered a wide variety of pain, from physical pain to dementia-related psychological and spiritual aspects of total pain, including living environment changes, stigma, discrimination, lack of communication and understanding, loss of sense of control and dignity, and cultural distress. It also identified physical appearance as an important factor associated with dying with dignity, as established by existing research on individuals with incurable cancer7).

Figure 2.

Total pain of dementia patients receiving palliative care.

Pain in advanced dementia can be understood as having physical, psychological, social, and spiritual components. Pain was not just a physical sensation: it might be a consequence of psychological and psychiatric symptoms, loneliness, spiritual distress, or daily life environment. The combination of these elements results in a “total pain” experience that is individualized and specific to each patient’s particular situation. Whether or not patients with advanced dementia report pain, hurting, or suffering, it is important to assess these experiences through a multidimensional lens that allows for the appreciation of all possible causes and influences.

Discussion

This qualitative review summarized the specifics of total pain in advanced dementia, and the authors revised the model of total pain in palliative care to apply it to advanced dementia patients. Pain is a subjective experience; however, with dementia, in contrast to cancer, patients’ self-reported pain is limited. Pain in dementia patients must be translated by healthcare professionals into an objective assessment to guide interventions. This model reconfirmed that advanced dementia patients suffer symptoms including physical pain, breathlessness, and neuropsychiatric symptoms, as well as complications such as respiratory or urinary infections. It also provided a conceptual basis for actively reflecting on and evaluating the atmosphere and environment in care settings. Advanced dementia patients still have numerous complex physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs requiring multidisciplinary health care. This model may help healthcare professionals identify and meet the unmet palliative care needs of dementia patients.

Conclusion

Dementia is the most common neurological disorder, usually chronic or progressive, leading to deterioration in cognitive function. It is a life-limiting condition; however, it is not recognized as a terminal disorder. Therefore, the authors revised the model of total pain in palliative care to apply to advanced dementia patients. The conceptual model of total pain in people with advanced dementia may help turn healthcare professionals’ attention to the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual contributors to total pain in advanced dementia.

Acknowledgments

The authors disclose receipt of the following financial support for this article’s research, authorship, and publication. This work was supported by a Health Labor Sciences Research Grant [grant number 21GB1001].

References

- 1.Richmond C. Dame Cicely Saunders. BMJ 2005; 331: 238. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7510.238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta A, Chan LS. Understanding of the concept of “total pain”. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2008; 10: 26–32. doi: 10.1097/01.NJH.0000306714.50539.1a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison KL, Kotwal AA, Smith AK. Palliative care for patients with noncancer illnesses. JAMA 2020; 324: 1404–1405. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.15075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenmann Y, Golla H, Schmidt H, et al. Palliative care in advanced dementia. Front Psychiatry 2020; 11: 699. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirakawa Y, Yajima K, Chiang C, et al. Meaning and practices of spiritual care for older people with dementia: experiences of nurses and care workers. Psychogeriatrics 2020; 20: 44–49. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008; 62: 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tollow P, Ogden J, McCabe CS, et al. ‘Physical appearance and well-being in adults with incurable cancer: a thematic analysis’. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2020; bmjspcare-2020-002632. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]