Abstract

Sprue-like enteropathy (SLE) is a clinical syndrome similar to celiac disease and has been associated with the use of various angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), a class of medications frequently used in the management of hypertension. Currently, there has only been one documented case report which has observed this occurrence with the use of the ARB candesartan. A 90-year-old female patient presented with chronic diarrhea and weight loss of unclear etiology. Diagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy and ileocolonoscopy were macroscopically unremarkable, but histological samples revealed complete villous atrophy, chronic mucosal inflammation, and intraepithelial T-lymphocytic infiltration. However, serological studies could not confirm celiac disease as a cause for the patient’s symptoms of malabsorption. After exclusion of other intestinal inflammation etiologies with noted ongoing candesartan use, the diagnosis of SLE was made, and candesartan therapy was discontinued. Additionally, we decided to initiate a lactose-free diet. Clinical remission was achieved without any recurrences. Candesartan is a commonly prescribed therapeutic agent in the treatment of hypertension. Our case underlines the importance of considering it as a potential cause for unexplained symptoms of malabsorption.

Keywords: Candesartan, Angiotensin receptor blocker, Sprue-like enteropathy, Sprue-like intestinal disease, Celiac disease, Adverse events

Introduction

Sprue-like enteropathy (SLE) is a clinical syndrome that closely resembles celiac disease; the latter also known as gluten-sensitive enteropathy or celiac sprue. The symptoms range from mild abdominal discomfort to severe chronic diarrhea and is characterized by similar histopathological changes to the intestinal mucosa [1]. Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder characterized by intestinal hypersensitivity to gliadin, a component of the protein gluten contained in grains. T-cell mediated chronic intestinal inflammation causes epithelial damage with villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and loss of the brush border [2]. In contrast, SLE patients generally present with similar pathohistological changes but have negative celiac serological findings and are unresponsive to a gluten-free diet [3].

SLE can be triggered by pharmacological agents (drug-induced SLE) in addition to other etiologies that can lead to intestinal mucosal injury. Several pharmacological substances have been involved in its pathogenesis, including angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) [1]. ARBs are among the most commonly used first-line antihypertensive agents [4, 5]. They primarily work by inhibiting the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system [3]. Known side effects include hyperkalemia, hypotension, and angioedema [5]. More recently, they have further been implicated in the occurrence of drug-induced SLE, which was first documented in 2012 by the Mayo Clinic (USA). In a series of 22 cases, the study noted an association between olmesartan and drug-induced SLE [6]. This association has subsequently been supported by a case series of 36 patients with olmesartan-associated enteropathy in a French national survey [7]. Other ARBs have also been named as triggers of drug-induced SLE [8–10]. Monde et al. [11] reported on a case of SLE associated with the ARB candesartan. In addition, a retrospective longitudinal analysis of German and Italian patient databases, De Bortoli et al. [12] found an association between the use of various ARBs, among them candesartan, and the occurrence of unspecified intestinal malabsorption.

We describe the case of a 90-year-old patient admitted to our hospital with chronic diarrhea and weight loss after having been treated with candesartan. After discontinuation of candesartan, the diarrhea stopped, and the patient has remained symptom-free to date.

Case Presentation

A 90-year-old female with a past medical history of chronic kidney disease stage 3 and hypertension was admitted to our hospital with chronic diarrhea. The patient had reported up to 8 bowel movements per day after meals and nocturnal diarrhea for about 6 weeks, accompanied by a 4-kg unintentional weight loss. Her past medical history was unremarkable for gastrointestinal pathologies. Physical examination demonstrated signs of malnourishment with evidence of exsiccosis. Otherwise, clinical examination and abdominal ultrasound were normal.

The basic metabolic panel on admission showed hypokalemia (2.67 mmol/L [reference: 3.1–5.1 mmol/L]) and an increase of C-reactive protein to 35 mg/L (reference: <5 mg/dL). The complete blood count was normal. Fecal calprotectin was only very mildly elevated (86 μg/g [reference <50]). Stool cultures did not demonstrate any infectious etiology. These findings were compatible with some kind of relatively mild colonic inflammatory process associated with rather severe diarrhea.

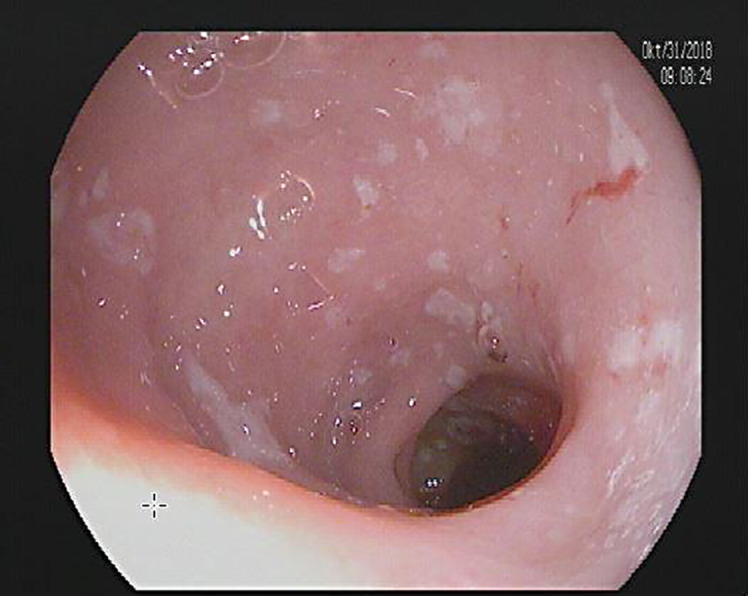

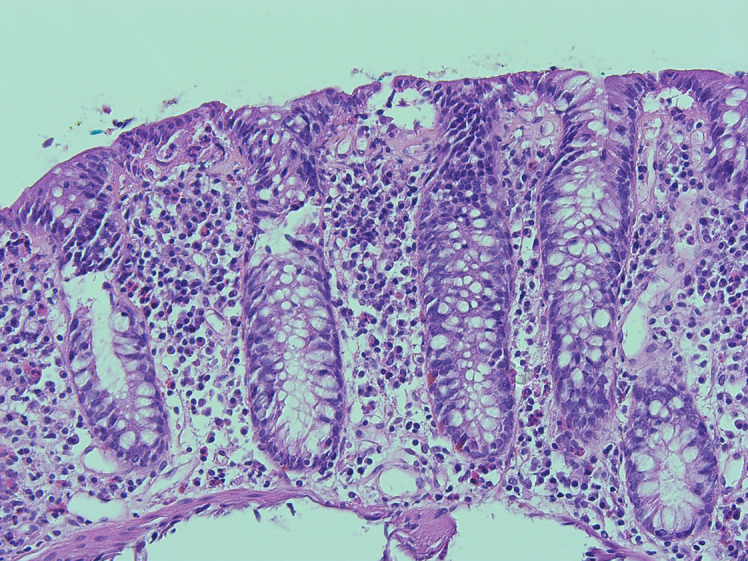

A diagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed multiple fibrin covered erosions indicative of duodenitis (shown in Fig. 1). Histological analysis of samples taken in the duodenum showed signs of a noninfectious inflammation with complete villous atrophy, as shown in Figure 2a as compared to a specimen from a non-affected person in Figure 2b. Ileocolonoscopy was macroscopically unremarkable apart from diverticula without signs of inflammation (shown in Fig. 3). Colonic biopsies were consistent with a mild chronic mucosal inflammation: intraepithelial leukocytosis and proliferation of collagenous connective tissue forming subepithelial collagen bands (shown in Fig. 4). No signs of ischemia were found.

Fig. 1.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy shows several fibrin-covered erosions in the duodenum that are indicative of duodenitis.

Fig. 2.

a Left: Duodenal biopsy reveals complete villous atrophy (H&E stain, ×20 magnification). a Right: Duodenal biopsy shows intraepithelial leukocytosis (H&E stain, ×200 magnification). b Normal duodenal mucosa with villi and microvilli (H&E stain, ×40 magnification).

Fig. 3.

Ileocolonoscopy shows diverticula without signs of inflammation.

Fig. 4.

Colonic biopsy shows intraepithelial leukocytosis and proliferation of collagenous connective tissue forming subepithelial collagen bands without signs of ischemia (H&E stain, ×200 magnification).

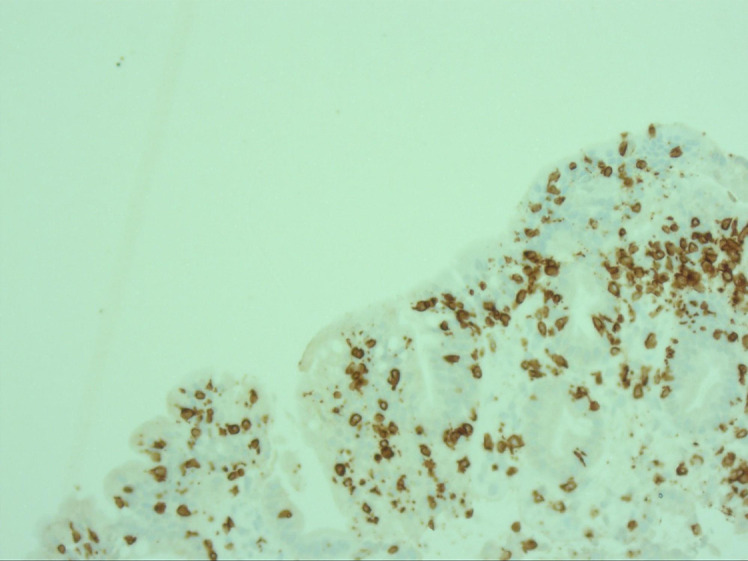

Immunohistochemistry showed significant intraepithelial CD3-positive T-lymphocytic infiltration in the duodenum (shown in Fig. 5). Histological samples from the colon also showed intraepithelial CD3-positive T-lymphocytic infiltration and subepithelial collagen bands (shown in Fig. 6a, b, respectively), but the diagnostic threshold for lymphocytic colitis (20 intraepithelial lymphocytes [IELs]/100 enterocytes) and/or collagenous colitis (subepithelial band thickness of >10µ) was not met. Furthermore, the increase in IELs did not meet the diagnostic threshold of 40 IELs/100 enterocytes for celiac disease using the MARSH classification. Additional serological studies for celiac disease were unremarkable, with normal total IgA, negative IgA/IgG tissue transglutaminase antibodies, and negative IgA/IgG antigliadin antibodies.

Fig. 5.

Duodenal immunohistochemistry shows intraepithelial CD3-positive T-lymphocytic infiltration (DAB staining with hematoxylin nuclear counterstaining, ×40 magnification).

Fig. 6.

a Colonic immunohistochemistry shows intraepithelial CD3-positive T-lymphocytic infiltration (DAB staining with hematoxylin nuclear counterstaining, ×100 magnification). b Colonic immunohistochemistry shows subepithelial collagen bands in blue (Ladewig’s staining, ×200 magnification).

After ruling out other iatrogenic causes of intestinal inflammation, with particular consideration for other pharmacological agents that could cause gastrointestinal side effects (see Table 1 for medications at admission), the symptoms were attributed to her utilization of candesartan (16 mg per oral once daily in the morning) and the diagnosis of ARB-induced SLE was made. Four days after the discontinuation of candesartan and initiation of a lactose-free diet, the diarrhea was markedly reduced and the patient's general well-being improved. After discharge, the patient’s primary care physician confirmed that the diarrhea continued to improve and had completely subsided with no recurrences after 6 weeks.

Table 1.

Medications at admission

| Medication | Dose | Dose frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Amlodipine | 5 mg | 1-0-1 (qAM PM) |

| Bisoprolol | 2.5 mg | 1-0-0 (qAM)) |

| Candesartan | 16 mg | 1-0-0 (qAM) |

| Eliquis (apixaban) | 2.5 mg | Held |

| Folic acid | 5 mg | 1-0-0 (qAM) |

| Magnesium effervescent tablets | Unknown | 1-0-0 (qAM) |

| Metamizole | 500 mg | 1-1-1-1 (QID) |

| Torem (torsemide) | 5 mg | 1-0-0 (qAM) |

| Tramadol | 100 mg | 0-0-1 (qPM) |

| Vitamin D | 1,000 IU | 1-0-0 (qAM) |

qAM, once a day in the morning; qPM, once a day in the evening; qAM PM, every morning and evening; QID, four times a day.

Discussion

The diagnosis of drug-induced SLE is based on histological evidence demonstrating villous atrophy and intraepithelial lymphocytosis that cannot be explained by other etiologies and regresses after discontinuation of the ARB in question [1, 10]. Based on these criteria, numerous studies have demonstrated an association between the use of ARBs and enteropathy. However, only one case report has made a connection between candesartan and ARB-induced enteropathy. Monde et al. [11] reported a case of candesartan-associated diarrhea that resolved after discontinuation of the triggering agent. Our case has many similarities to the case of Monde et al. [11], which also reported marked mucosal inflammation with villous atrophy on duodenal and colonic biopsy with negative diagnostic testing for celiac disease. In contrast to the case report of Monde et al. [11], we specify the process of coming to the diagnosis of SLE step by step. For instance, we exclude infections, ischemia, microscopic colitis, and other pharmacological agents as causative for the patient’s malabsorption symptoms and support our hypothesis with detailed diagnostic findings. In addition, we show pictures of the biopsies and the immunohistochemistry taken from duodenal and colonic tissue.

Both cases showed cessation of symptoms after candesartan was discontinued. Further, Monde et al. [11] demonstrated marked regression of villous atrophy on a follow-up biopsy 3 months after stopping of candesartan, proving the reversibility of symptoms with the removal of the trigger. Given the patient’s high age, we did not perform a follow-up esophagogastroduodenoscopy and subsequently cannot show pathological evidence that the villous atrophy and mucosal inflammation regressed after candesartan was stopped. However, the patient’s primary care physician confirmed that her diarrhea never returned. After careful exclusion of other causes of enteropathy, such as inflammatory bowel disease, ischemic colitis, microscopic colitis, infectious colitis, and celiac disease, the use of ARBs was the most plausible cause of the histopathological and clinical findings. This is in line with a review of 73 case reports on SLE-associated enteropathy by Wenzel and Datz [10], who demonstrated that discontinuation of the ARB in question led to complete healing and cessation of symptoms in all cases. Thus, our findings are consistent with the literature on SLE-associated enteropathy.

While the pathogenesis of ARB-induced SLE is currently unclear, several mechanisms have been suggested, such as increased intestinal sodium and water secretion mediated by AT1 receptor inhibition or an AT2 receptor-mediated increase in TGF-beta signal transduction and disruption of mucosal regeneration [10]. The long latency period between the administration of ARBs and the onset of clinical symptoms has been interpreted as a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction, which is characterized by CD3-positive and cytotoxic CD8-positive lymphocytes mucosal infiltrates. Immunohistochemistry of our duodenal biopsies showed a significant degree of CD3-positive T-lymphocytic infiltration (shown in Fig. 5), which is consistent with this hypothesis.

What is more, we could show a temporal relationship between the administration of candesartan and the onset of diarrhea. After requesting all medical files and medication plans, we could trace back the patient’s medical history to 1991. The last episode of diarrhea was described in 1995 prior to the initiation of ARBs in 2001 (irbesartan) and the switch to candesartan in 2014. In conclusion, our case adds on to the existing evidence and expands the list of ARBs that cause SLE-induced enteropathy.

In this case, we show an association between the use of a commonly used ARB, candesartan, and the occurrence of drug-induced SLE. This supports a previous connection between the use of candesartan and enteropathy made by Monde et al. [11]. Furthermore, our case supports the hypothesis that ARB-induced enteropathy is a class effect rather than a special adverse event for the ARB olmesartan [10] and expands the list of ARBs that have been associated with it. The CARE Checklist has been completed by the authors for this case report, attached as online supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000529003).

Statement of Ethics

The research was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was not required for this study in accordance with local/national guidelines. Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient for publication of the details of their medical case and any accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No funding was received.

Author Contributions

Lydia Holtgrewe, Stefan Linnemüller, and Frank Schuppert collected all needed information and data needed for the case study. Lydia Holtgrewe and Frank Schuppert drafted the manuscript. The patient was treated by Stefan Linnemüller during her hospital stay. Harald Dippel, the patient’s primary care physician, provided information about the patient’s follow-up. Hildegard Weckauf provided histological pictures and pathological expertise. All the authors have read and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

No funding was received.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this case report are not publicly available due to information that could compromise the privacy of the patient. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Freeman HJ. Drug-induced sprue-like intestinal disease. Int J Celiac Dis. 2014 Feb;2(2):49–53. 10.12691/ijcd-2-2-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oxentenko AS, Rubio-Tapia A. Celiac disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019 Dec;94(12):2556–71. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kamal A, Fain C, Park A, Wang P, Gonzalez-Velez E, Leffler DA, et al. Angiotensin II receptor blockers and gastrointestinal adverse events resembling sprue-like enteropathy: a systematic review. Gastroenterol Rep. 2019 Jun;7(3):162–7. 10.1093/gastro/goz019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heran BS, Wong MMY, Heran IK, Wright JM. Blood pressure lowering efficacy of angiotensin receptor blockers for primary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Oct;2008(4):CD003822. 10.1002/14651858.CD003822.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mayo Clinic . Angiotensin II receptor blockers. 1998–2022 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER); 2021 Aug. [cited 2022 Sep 10]. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/high-blood-pressure/in-depth/angiotensin-II-receptor-blockers/ART-20045009?p=1. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rubio-Tapia A, Herman ML, Ludvigsson JF, Kelly DG, Mangan TF, Wu TT, et al. Severe spruelike enteropathy associated with olmesartan. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012 Dec;87(8):732–8. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marthey L, Cadiot G, Seksik P, Pouderoux P, Lacroute J, Skinazi F, et al. Olmesartan-associated enteropathy: results of a national survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014 Sep;40(9):1103–9. 10.1111/apt.12937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Herman ML, Rubio-Tapia A, Wu TT, Murray JA. A case of severe sprue-like enteropathy associated with valsartan. ACG Case Rep J. 2015 Jan;2(2):92–4. 10.14309/crj.2015.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Negro A, Rossi GM, Santi R, Iori V, De Marco L. A case of severe sprue-like enteropathy associated with losartan. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015 Oct;49(9):794. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wenzel RR, Datz C. Association of sprue-like enteropathy and angiotensin receptor-1 antagonists. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2019 Aug;131(19–20):493–501. 10.1007/s00508-019-01539-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Monde L, Pierson-Marchandise M, Gras V, Sevestre H, Lawson P, Andrejak M, et al. Angiotensin II receptor blockers-induced enteropathy: not just olmesartan! A case report with candesartan. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2016 Mar;30(S1):47–87. 10.1007/s40278-017-26633-9.26501493 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Bortoli N, Ripellino C, Cataldo N, Marchi S. Unspecified intestinal malabsorption in patients treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers: a retrospective analysis in primary care settings. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2017 Sep;16(11):1221–5. 10.1080/14740338.2017.1376647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this case report are not publicly available due to information that could compromise the privacy of the patient. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.