Abstract

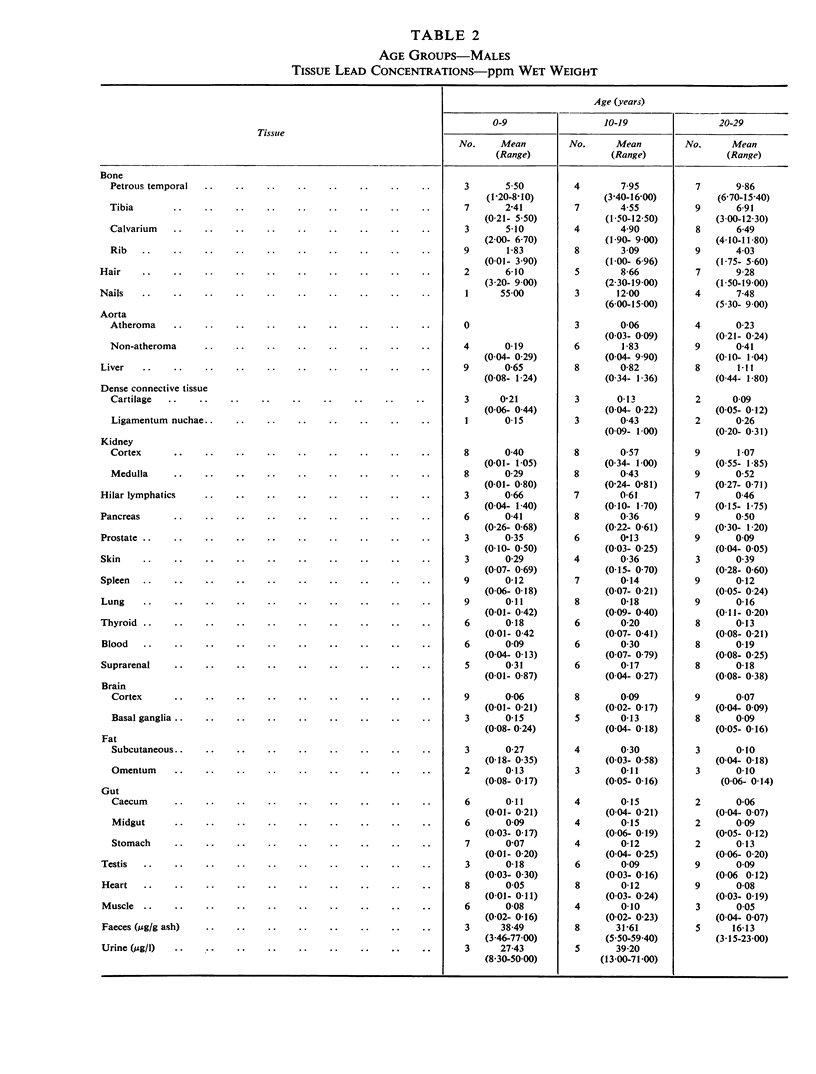

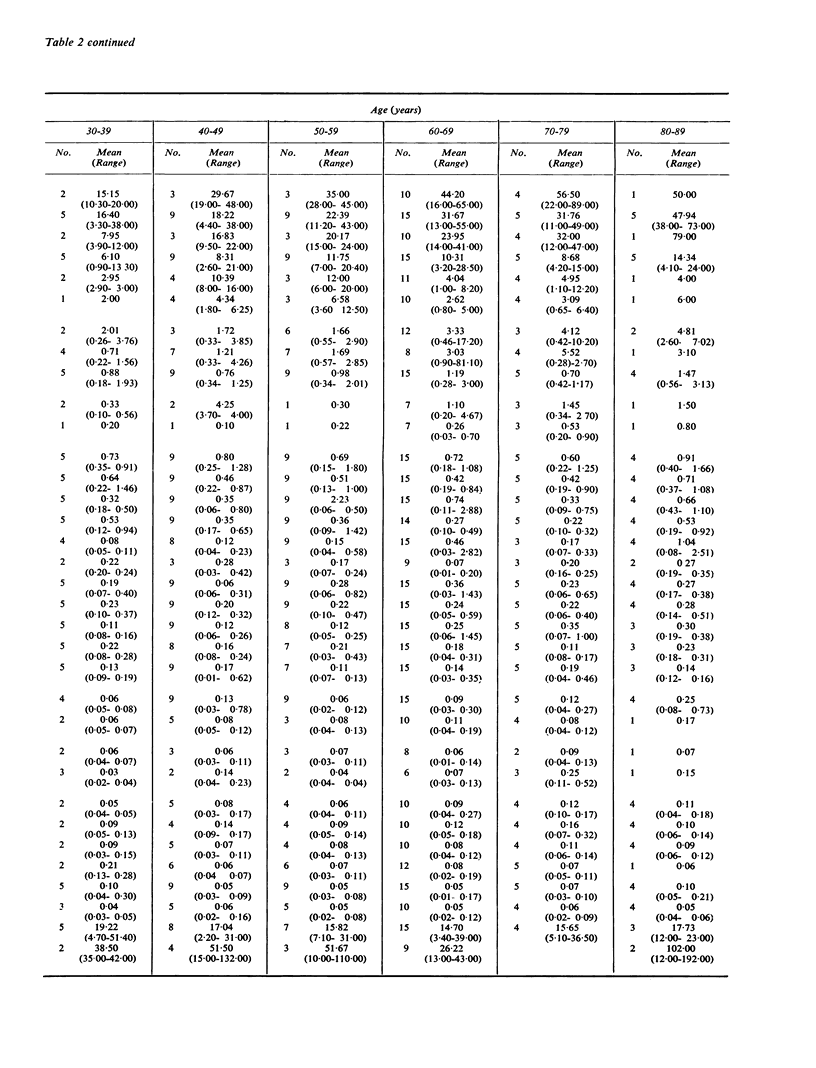

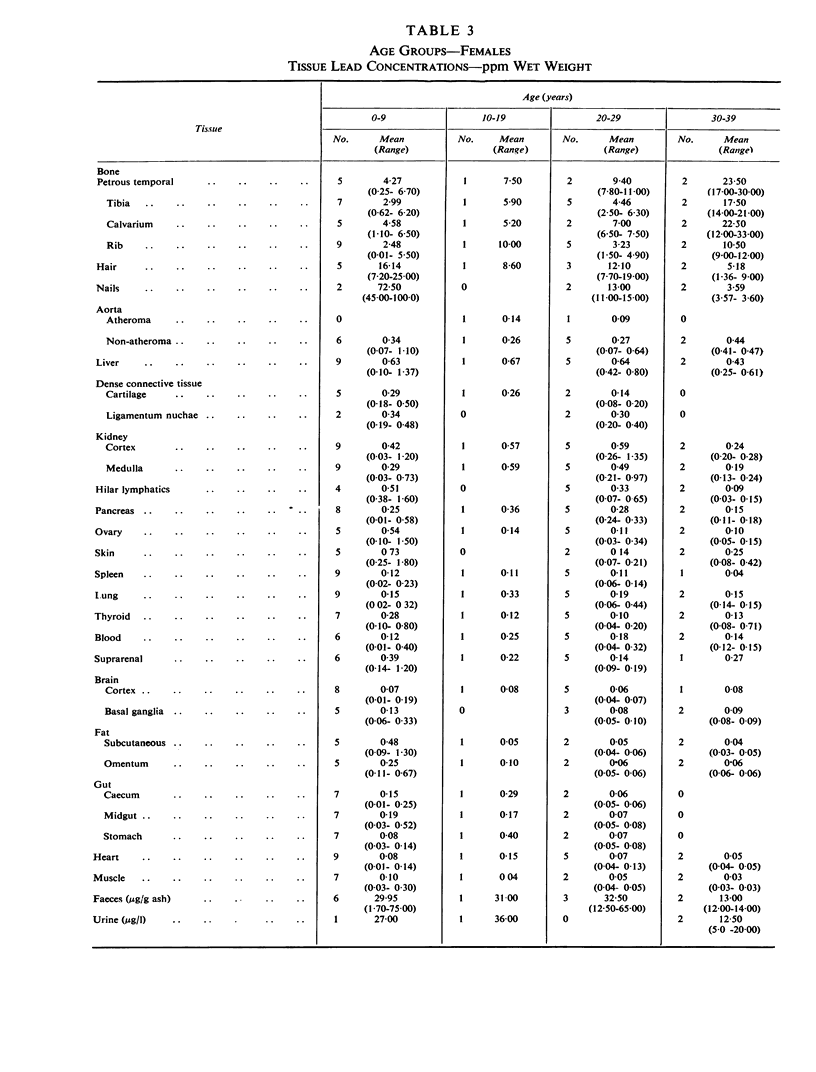

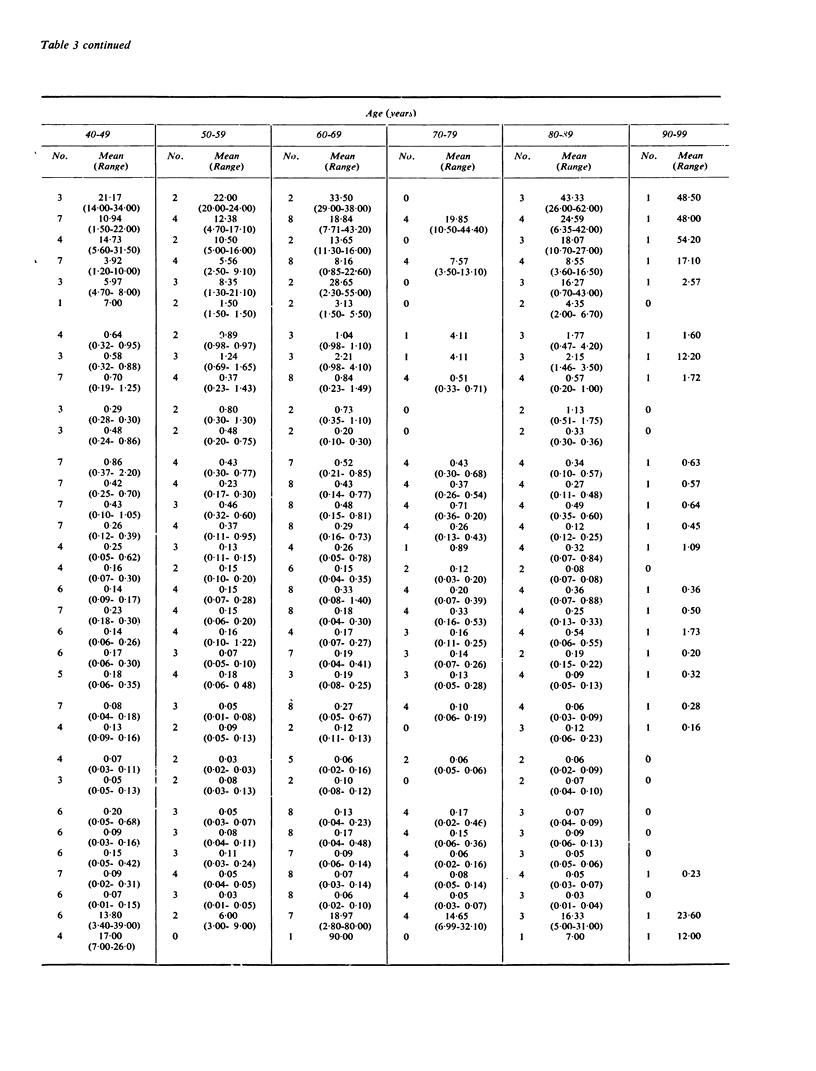

This postmortem study of lead concentrations in the tissues of 129 subjects is an extension to a report by Barry and Mossman (1970). Lead concentrations in bone greatly exceeded the concentrations in soft tissues and were highest in the dense bones. Bone lead concentrations increased with age in both sexes, more especially in male subjects and in dense bone, varying between mean values of 2-16 ppm in the ribs of children to over 50 ppm in the dense petrous temporal bones of elderly male adults. Male adults contained over 30% more lead in their bones than females. Mean concentrations of lead in the soft tissues varied from less than 0-1 ppm in organs such as muscle and heart to over 2 ppm in the aorta. In most tissues with lead values in excess of 0-2 ppm the male concentrations exceeded female values by about 30%. With the exception of the aorta, spleen, lung, and prostate, lead concentrations did not increase with age in the soft tissues of either sex after about the second decade of life. Children showed concentrations of lead in their soft tissues comparable to female adults, but the concentrations in bone were much lower. It is suggested that children do not possess the same capacity as adults to retain lead in bone. In male adults occupationally exposed to lead the concentrations of lead in bone exceeded the concentrations in unexposed male adults within the same age group by two-to three-fold. Soft tissue lead concentrations between the two groups were less divergent. An assessment of the total body burden of lead revealed higher levels in adult male subjects than in females at mean values of 164-8 mg compared to 103-6 mg, respectively. Over 90% of the total body burden of lead in adults was in bone, of which over 70% was in dense bone. Male adults occupationally exposed to lead had mean total body burdens of 566-4 mg Pb, of which 97% was in bone. The release of lead from bone in conjunction with calcium was not considered to be of physiological significance. Lead concentrations of hair and nails were higher than soft tissue lead concentrations and varied widely. Hair lead measurements were not considered to provide a reliable assessment of lead absorption. The concentrations of lead in tissues of a mixed group of subjects with no known occupational exposure to lead have been shown to be comparable to the findings in earlier studies. Present levels of lead in the environment are not considered to be a hazard to the health of the population in general.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barltrop D., Killala N. J. Faecal excretion of lead by children. Lancet. 1967 Nov 11;2(7524):1017–1019. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(67)90289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barltrop D. Lead poisoning. Arch Dis Child. 1971 Jun;46(247):233–235. doi: 10.1136/adc.46.247.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barltrop D., Strehlow C. D., Thorton I., Webb J. S. Significance of high soil lead concentrations for childhood lead burdens. Environ Health Perspect. 1974 May;7:75–82. doi: 10.1289/ehp.74775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry P. S., Mossman D. B. Lead concentrations in human tissues. Br J Ind Med. 1970 Oct;27(4):339–351. doi: 10.1136/oem.27.4.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie A. D., Dagg J. H., Goldberg A., Wang I., Ronald J. Lead poisoning in rural Scotland. Br Med J. 1972 May 27;2(5812):488–491. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5812.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie A. D., Moore M. R., Devenay W. T., Miller A. R., Goldberg A. Environmental lead pollution in an urban soft-water area. Br Med J. 1972 May 27;2(5812):491–493. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5812.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHISOLM J. J., Jr, HARRISON H. E. The exposure of children to lead. Pediatrics. 1956 Dec;18(6):943–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisolm J. J., Jr Lead poisoning. Sci Am. 1971 Feb;224(2):15–23. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0271-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of inorganic lead poisoning: a statement. Br Med J. 1968 Nov 23;4(5629):501–501. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5629.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMMERSON B. T. CHRONIC LEAD NEPHROPATHY: THE DIAGNOSTIC USE OF CALCIUM EDTA AND THE ASSOCIATION WITH GOUT. Australas Ann Med. 1963 Nov;12:310–324. doi: 10.1111/imj.1963.12.4.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinee V. F. Lead poisoning in New York City. Trans N Y Acad Sci. 1971 May;33(5):539–551. doi: 10.1111/j.2164-0947.1971.tb02619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HENDERSON D. A. A follow-up of cases of plumbism in children. Australas Ann Med. 1954 Aug;3(3):219–224. doi: 10.1111/imj.1954.3.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haar G. T., Aronow R. New information on lead in dirt and dust as related to the childhood lead problem. Environ Health Perspect. 1974 May;7:83–89. doi: 10.1289/ehp.74783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer D. I., Finklea J. F., Hendricks R. H., Shy C. M., Horton R. J. Hair trace metal levels and environmental exposure. Am J Epidemiol. 1971 Feb;93(2):84–92. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R. W., Elsea W. R. Ceramic glaze as a source of lead poisoning. JAMA. 1967 Nov 6;202(6):544–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEHOE R. A. The Harben Lectures, 1960: The metabolism of lead in man in health and disease. 3. Present hygienic problems relating to the absorption of lead. J R Inst Public Health. 1961 Aug;24:177–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein M., Namer R., Harpur E., Corbin R. Earthenware containers as a source of fatal lead poisoning. N Engl J Med. 1970 Sep 24;283(13):669–672. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197009242831302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopito L., Briley A. M., Shwachman H. Chronic plumbism in children. Diagnosis by hair analysis. JAMA. 1969 Jul 14;209(2):243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANE C. R., LAWRENCE A. Home-made wine as a cause of lead-poisoning: report of case. Br Med J. 1961 Oct 7;2(5257):939–940. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5257.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurer G. R., Albert R. E., Kneip T. J., Pasternack B., Strehlow C., Nelson N., Kent F. S. The distribution of lead paint in New York City tenement buildings. Am J Public Health. 1973 Feb;63(2):163–168. doi: 10.2105/ajph.63.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J. M., Hartley M. W., Miller R. E. Nephropathy in chronic lead poisoning. Arch Intern Med. 1966 Jul;118(1):17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NUSBAUM R. E., BUTT E. M., GILMOUR T. C., DIDIO S. L. RELATION OF AIR POLLUTANTS TO TRACE METALS IN BONE. Arch Environ Health. 1965 Feb;10:227–232. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1965.10663989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw G. D., Pounds C. A., Pearson E. F. Variation in lead concentration along single hairs as measured by non-flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry. Nature. 1972 Jul 21;238(5360):162–163. doi: 10.1038/238162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs H. K. Effect of a screening program on changing patterns of lead poisoning. Environ Health Perspect. 1974 May;7:41–45. doi: 10.1289/ehp.74741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder H. A., Tipton I. H. The human body burden of lead. Arch Environ Health. 1968 Dec;17(6):965–978. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1968.10665354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAVERS E., RENDLE-SHORT J., HARVEY C. C. The Rotherham lead-poisoning outbreak. Lancet. 1956 Jul 21;271(6934):113–116. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(56)90863-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. A. Balance between intake and output of lead in normal individuals. Br J Ind Med. 1971 Apr;28(2):189–194. doi: 10.1136/oem.28.2.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompsett S. L. The distribution of lead in human bones. Biochem J. 1936 Mar;30(3):345–346. doi: 10.1042/bj0300345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls A. D. Home-made cider: source of lead-poisoning. Br Med J. 1969 Jan 11;1(5636):98–98. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5636.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D., Whitten B., Leddy D. Lead content of human hair (1871-1971). Science. 1972 Oct 6;178(4056):69–70. doi: 10.1126/science.178.4056.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Dakhakhny A. A., el-Sadik Y. M. Lead in hair among exposed workers. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1972 Jan;33(1):31–34. doi: 10.1080/0002889728506603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]