Abstract

This study uses data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs to assess whether SARS-CoV-2 remains associated with higher risk of death compared with seasonal influenza in fall-winter 2022-2023.

In the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, 2 US studies suggested that people hospitalized for COVID-19 had nearly 5 times the risk of 30-day mortality compared with those hospitalized for seasonal influenza.1,2 Since then, much has changed, including SARS-CoV-2 itself, clinical care, and population-level immunity; mortality from influenza may have also changed. This study assessed whether COVID-19 remains associated with higher risk of death compared with seasonal influenza in fall-winter 2022-2023.

Methods

We used the electronic health databases of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Between October 1, 2022, and January 31, 2023, we enrolled all individuals with at least 1 hospital admission record between 2 days before and 10 days after a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 or influenza and an admission diagnosis for COVID-19 or seasonal influenza. We removed 143 participants hospitalized with both infections. The cohort was followed up until the first occurrence of death, 30 days after hospital admission, or March 2, 2023. Differences in baseline characteristics between the groups were evaluated through absolute standardized differences (<0.1 indicating good balance).

We evaluated the risk of death in people hospitalized for COVID-19 vs influenza through inverse probability-weighted Cox survival models. Logistic regression was used to generate a propensity score, which was then applied in inverse probability weighting to balance the 2 groups; covariates were defined based on prior knowledge and ascertained in the 3 years preceding admission (eMethods in Supplement 1). We also estimated the absolute risk as the percentage of excess deaths (difference in death rates between COVID-19 and influenza groups at 30 days). Risk was also examined in prespecified subgroups (age ≤65 years vs >65 years; COVID-19 vaccination; SARS-CoV-2 infection status; and use of outpatient COVID-19 antiviral treatment before admission) (eMethods in Supplement 1). Interaction analyses were undertaken to assess statistically significant risk differences between subgroups.

Analyses were performed with SAS Enterprise Guide version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc). Statistical significance was defined as a 95% CI that did not cross 1.0 on a relative scale. The study was approved with a waiver of informed consent by the VA St Louis Health Care System institutional review board.

Results

There were 8996 hospitalizations (538 deaths [5.98%] within 30 days) for COVID-19 and 2403 hospitalizations (76 deaths [3.16%]) for seasonal influenza (Table). After propensity score weighting, the 2 groups were well balanced (mean age, 73 years; 95% male).

Table. Baseline Characteristics in Seasonal Influenza and COVID-19 Group Before and After Propensity Score Weighting.

| Before propensity score weighting | After propensity score weightinga | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seasonal influenza (n = 2403) | COVID-19 (n = 8996) | SMDb | Seasonal influenza (n = 2403) | COVID-19 (n = 8996) | SMDb | |

| Age | ||||||

| Mean (SD), y | 70.52 (11.68) | 73.42 (12.25) | 0.24 | 73.81 (12.22) | 73.42 (12.25) | 0.03 |

| ≤65 y, No. (%) | 665 (27.67) | 1787 (19.86) | 0.18 | 481 (20.03) | 1787 (19.86) | 0.004 |

| >65 y, No. (%) | 1738 (72.33) | 7209 (80.14) | 0.18 | 1922 (79.98) | 7209 (80.14) | 0.004 |

| Race, No. (%)c | ||||||

| Black | 607 (25.26) | 2066 (22.97) | 0.05 | 562 (23.40) | 2066 (22.97) | 0.01 |

| White | 1694 (70.50) | 6421 (71.38) | 0.02 | 1713 (71.29) | 6421 (71.38) | 0.003 |

| Other | 102 (4.24) | 509 (5.66) | 0.07 | 128 (5.34) | 509 (5.66) | 0.01 |

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||||

| Male | 2245 (93.42) | 8580 (95.38) | 0.09 | 2295 (95.51) | 8580 (95.38) | 0.007 |

| Female | 158 (6.58) | 416 (4.62) | 0.09 | 108 (4.49) | 416 (4.62) | 0.007 |

| Smoking status, No. (%) | ||||||

| Never | 688 (28.63) | 3231 (35.92) | 0.16 | 890 (37.05) | 3231 (35.92) | 0.02 |

| Former | 906 (37.70) | 3658 (40.66) | 0.06 | 973 (40.50) | 3658 (40.66) | 0.003 |

| Current | 809 (33.67) | 2107 (23.42) | 0.23 | 540 (22.45) | 2107 (23.42) | 0.02 |

| Area Deprivation Index, mean (SD)d | 53.73 (19.06) | 53.01 (18.92) | 0.04 | 52.61 (18.93) | 53.01 (18.92) | 0.02 |

| BMI, mean (SD)e | 29.18 (6.97) | 28.43 (7.63) | 0.10 | 28.28 (6.85) | 28.43 (7.63) | 0.02 |

| eGFR, mean (SD), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 65.51 (26.36) | 65.02 (27.10) | 0.02 | 63.85 (27.43) | 65.02 (27.10) | 0.04 |

| Blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | ||||||

| Systolic | 134.92 (12.43) | 134.39 (12.68) | 0.04 | 134.5 (12.57) | 134.39 (12.68) | 0.01 |

| Diastolic | 76.77 (7.47) | 75.29 (7.34) | 0.20 | 75.37 (7.34) | 75.29 (7.34) | 0.01 |

| COVID-19 vaccination status, No. (%) | ||||||

| Not vaccinated | 454 (18.89) | 1865 (20.73) | 0.05 | 429 (17.84) | 1865 (20.73) | 0.07 |

| 1 dose | 114 (4.74) | 384 (4.27) | 0.02 | 112 (4.68) | 384 (4.27) | 0.02 |

| 2 doses | 517 (21.51) | 1841 (20.46) | 0.03 | 530 (22.06) | 1841 (20.47) | 0.04 |

| Boosted | 1318 (54.85) | 4906 (54.54) | 0.01 | 1332 (55.43) | 4906 (54.54) | 0.02 |

| Influenza vaccine, No. (%) | 1487 (61.88) | 5743 (63.84) | 0.04 | 1524 (63.43) | 5743 (63.84) | 0.008 |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection, No. (%) | ||||||

| Primary infection | NA | 7111 (79.05) | NA | 7111 (79.05) | ||

| Reinfection | NA | 1885 (20.95) | NA | 1885 (20.95) | ||

| Treatment status, No. (%) | ||||||

| Outpatient nirmatrelvir-ritonavir, molnupiravir, or remdesivir | NA | 191 (2.12) | NA | 191 (2.12) | ||

| Inpatient remdesivir | NA | 2188 (24.32) | NA | 2188 (24.32) | ||

| Outpatient oseltamivir | 139 (5.78) | NA | 147 (6.13) | NA | ||

| Inpatient oseltamivir | 1982 (82.48) | NA | 1960 (81.58) | NA | ||

| Outcomes, No. (%) | ||||||

| Death within 30 d | 76 (3.16) | 538 (5.98) | 90 (3.74) | 538 (5.98) | ||

| In hospital death within 30 d | 47 (1.95) | 374 (4.16) | 56 (2.33) | 374 (4.16) | ||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; NA, not applicable; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Propensity score weights were estimated based on age, self-reported race, sex, area deprivation index, body mass index, smoking status, prior history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, use of long-term care, eGFR, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, use of steroid, cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, coronary artery disease, dementia, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, HIV, immune dysfunction, liver diseases and peripheral artery diseases, number of outpatient visits and hospital admissions, number of blood panel tests, number of medications received and number of Medicare outpatient visits and hospital admissions, the calendar date of the admission, hospital bed capacity, and hospital bed occupancy at the participants’ health care facility within the week of the admission.

SMD less than 0.1 was considered evidence of good balance.

Self-reported race information was collected from electronic health records and used in the study in accordance with the requirement by the funding agency (US Department of Veterans Affairs) and the Office of Management and Budget, which defines minimum standards for maintaining, collecting, and presenting data on race and ethnicity for all federal reporting agencies. Other race included Alaska Native and American Indian, Asian, or Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander. The categories in this classification are social-political constructs and should not be interpreted as being anthropological in nature.

A measure of socioeconomic disadvantage, with a range from low to high disadvantage of 0 to 100.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by square of height in meters.

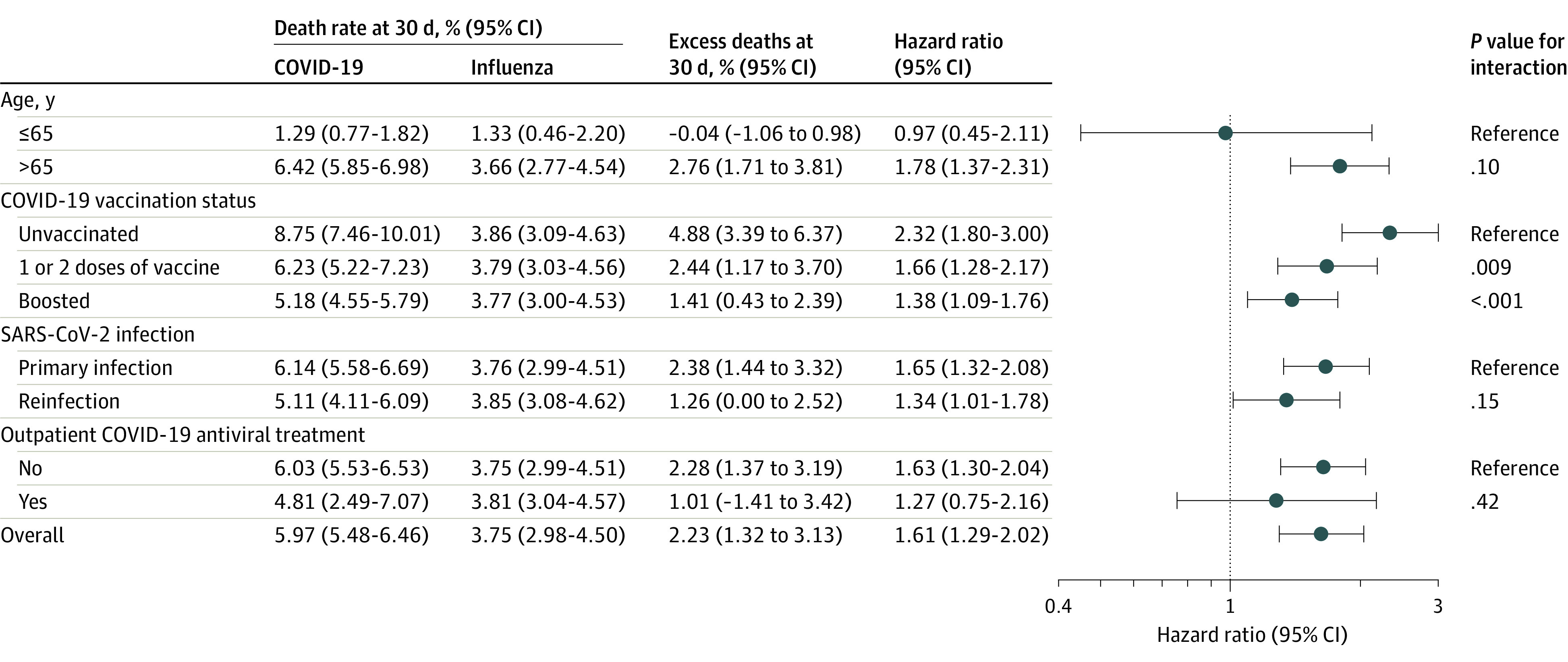

The death rate at 30 days was 5.97% for COVID-19 and 3.75% for influenza, with an excess death rate of 2.23% (95% CI, 1.32%-3.13%) (Figure). Compared with hospitalization for influenza, hospitalization for COVID-19 was associated with a higher risk of death (hazard ratio, 1.61 [95% CI, 1.29-2.02]).

Figure. Hazard Ratio, Death Rates, and Percentage of Excess Deaths in COVID-19 Compared With Seasonal Influenza.

Comparison conducted in overall cohort by age (≤65, >65 years) and by COVID-19 vaccination status (unvaccinated, 1-2 doses of vaccine, and boosted), SARS-CoV-2 infection status (with primary SARS-CoV-2 infection and reinfection), and outpatient COVID-19 antiviral treatment (yes or no), compared with overall seasonal influenza. Outpatient COVID-19 antiviral treatment included nirmatrelvir-ritonavir, molnupiravir, or remdesivir.

The risk of death decreased with the number of COVID-19 vaccinations (P = .009 for interaction between unvaccinated and vaccinated; P < .001 for interaction between unvaccinated and boosted). No statistically significant interactions were observed across other subgroups (Figure).

Discussion

This study found that, in a VA population in fall-winter 2022-2023, being hospitalized for COVID-19 vs seasonal influenza was associated with an increased risk of death. This finding should be interpreted in the context of a 2 to 3 times greater number of people being hospitalized for COVID-19 vs influenza in the US in this period.3,4 However, the difference in mortality rates between COVID-19 and influenza appears to have decreased since early in the pandemic; death rates among people hospitalized for COVID-19 were 17% to 21% in 2020 vs 6% in this study, while death rates for those hospitalized for influenza were 3.8% in 2020 vs 3.7% in this study.1,2 The decline in death rates among people hospitalized for COVID-19 may be due to changes in SARS-CoV-2 variants, increased immunity levels (from vaccination and prior infection), and improved clinical care.5

The increased risk of death was greater among unvaccinated individuals compared with those vaccinated or boosted—findings that highlight the importance of vaccination in reducing risk of COVID-19 death.

Study limitations include that the older and predominantly male VA population may limit generalizability to broader populations. The results may not reflect risk in nonhospitalized individuals. The analyses did not examine causes of death, and residual confounding cannot be ruled out.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Senior Editor.

eMethods

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Xie Y, Bowe B, Maddukuri G, Al-Aly Z. Comparative evaluation of clinical manifestations and risk of death in patients admitted to hospital with Covid-19 and seasonal influenza: cohort study. BMJ. 2020;371:m4677. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cates J, Lucero-Obusan C, Dahl RM, et al. Risk for in-hospital complications associated with COVID-19 and influenza—Veterans Health Administration, United States, October 1, 2018–May 31, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(42):1528-1534. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6942e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laboratory-confirmed COVID-19–associated hospitalizations. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Accessed March 7, 2023. https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/covidnet/covid19_3.html

- 4.Influenza Hospitalization Surveillance Network (FluSurv-NET). Accessed March 7, 2023. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/influenza-hospitalization-surveillance.htm

- 5.Portmann L, de Kraker MEA, Fröhlich G, et al. ; CH-SUR Study Group . Hospital outcomes of community-acquired SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant infection compared with influenza infection in Switzerland. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e2255599-e99. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.55599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement