Abstract

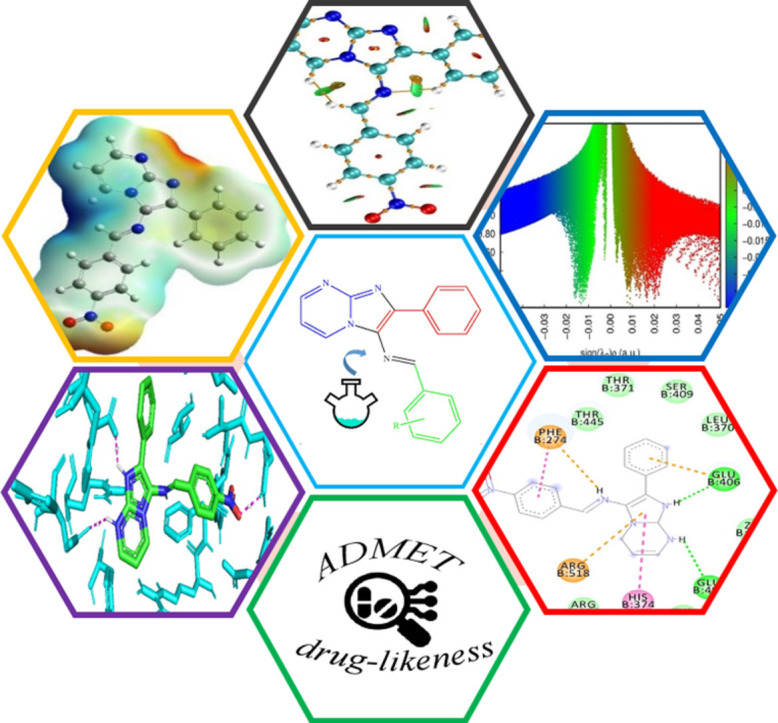

In the present work, a new series of imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine Schiff base derivatives have been obtained using an easy and conventional synthetic route. The synthesized compounds were spectroscopically characterized using 1H, 13C NMR, LC-MS(ESI), and FT-IR techniques. Green metric calculations indicate adherence to several green chemistry principles. The energy of Frontier Molecular Orbitals (FMO), Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP), Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM), and Reduced Density Gradient (RDG) were determined by the Density Functional Theory (DFT) method at B3LYP/6–31 G (d, p) as the basis set. Moreover, molecular docking studies targeting the human ACE2 and the spike, key entrance proteins of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 were carried out along with hACE2 natural ligand Angiotensin II, the MLN-4760 inhibitor as well as the Cannabidiolic Acid CBDA which has been demonstrated to bind to the spike protein and block cell entry. The molecular modeling results showed auspicious results in terms of binding affinity as the top-scoring compound exhibited a remarkable affinity (-9.1 and -7.3 kcal/mol) to the ACE2 and spike protein respectively compared to CBDA (-5.7 kcal/mol), the MLN-4760 inhibitor (-7.3 kcal/mol), and angiotensin II (-9.2 kcal/mol). These findings suggest that the synthesized compounds may potentially act as effective entrance inhibitors, preventing the SARS-CoV-2 infection of human cells. Furthermore, in silico, ADMET, and drug-likeness prediction expressed promising drug-like characteristics.

Keywords: Imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine; Schiff base; SARS-COV-2; DFT calculations; Molecular docking; ADMET; Drug-likeness

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Over the past decades, Nitrogen heterocycle compounds gained much interest in both synthetic and biological researchers as bioactive molecules [1], [2], [3]. Imidazo-fused heterocyclic scaffolding is considered one of the most important cores structures in organic compounds that are used for many applications in medicinal science [4]. Imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine derivatives constitute a significant class of fused nitrogen-bridged heterocyclic compounds seen as of great interest for biological chemists and tremendously important in the pharmaceutical industry [5], because of their broad spectrum of biological and pharmacological activities such as anti-cancer [6], anti-viral [7,8], anti-microbial [9,10], anti-fungal [11], and anti-inflammatory [12,13]. Many preclinical drug candidates have imidazopyrimidine motif as a core unit such as divaplon, fasiplon, and taniplon [14,15].

Given the biological potential, a series of novel 2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine-Schiff base derivatives were prepared using an easy and highly efficient synthetic route allowing large-scale production which could serve as promising scaffolds in the development of novel bioactive compounds.

At the end of 2019, a novel coronavirus named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) or (COVID-19) emerged in Wuhan City in central China. It quickly spread worldwide, affecting whole aspects of life [16]. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic in March 2020, marking one of modern history's biggest public health crises [17]. Globally, as of March 29, 2023, there have been 761 402 282 confirmed cases, including 6 887 000 deaths, reported to the WHO [18].

COVID-19 has become one of the deadliest and most debilitating viral respiratory diseases, exhibiting influenza-like symptoms ranging from mild discomfort to severe lung injury and multi-organ failure, ultimately leading to death. The virus's rapid spread and its ability to affect multiple vital organs made it a serious global crisis [19].

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been immense, causing unprecedented disruptions in global economies, overwhelming healthcare systems, leading to a significant loss of life [20]. The pandemic has also resulted in social isolation, mental health challenges, and has exposed deep inequalities in society. The pandemic has affected every aspect of daily life and has forced individuals and communities to adapt to new ways of living and working [21]. The economic impact has been particularly severe, caused widespread disruption to businesses and has resulted in job losses and economic downturns [22]. The pandemic has highlighted the importance of global cooperation and solidarity in addressing global health challenges and has underscored the need for investment in public health infrastructure and preparedness. The effects of this pandemic will continue to be felt for years to come, both in terms of its direct impact on public health and its far-reaching economic and social consequences.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, many efforts have been made by the scientific community to address the pandemic in numerous ways, including developing efficient and fast diagnostic tests [23], vaccines [24], antiviral drugs [24], and monoclonal antibodies [25], to alleviate the severity of COVID-19. While several therapeutic approaches have been explored to treat SARS-CoV-2 infection, including repurposing existing approved drugs like Hydroxychloroquine, Ritonavir, Favipiravir, Lopinavir, etc., either as monotherapies or in various combinations, the results from clinical trials have been inconsistent and at times contradictory. Nevertheless, clinicians have continued to use drugs that have shown even minimal efficacy in an effort to save lives [26].

Although both men and women can contract COVID-19, studies have shown that men are more likely to experience severe outcomes and are at a higher risk of mortality than women across all age groups [27,28]. The reasons for this gender discrepancy are not fully understood, but several factors are believed to play a role. One possibility is that the hormonal differences between men and women could be a contributing factor [29]. Studies suggest that estrogens may help protect against COVID-19 by enhancing the immune system's ability to fight the virus. Conversely, androgens have been linked to worse COVID-19 outcomes in men [30]. Additionally, sex-specific differences in ACE2 gene expression in human lung tissue, with males having higher ACE2 expression levels than females, could also explain this gender discrepancy [31]. Therefore, understanding the gender differences in COVID-19 outcomes can help researchers develop targeted interventions and treatments to improve outcomes for all individuals affected by the disease [32].

Imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine derivatives have antiviral properties and may be effective against other viruses, such as HIV [33,34] and hepatitis C [35]. Thus, we investigated their potential as a treatment for COVID-19. However, it is too early to say with certainty whether it would benefit males more than females, or vice versa. More research is needed to fully understand the implications of sex differences in the context of COVID-19.

As it is coronavirus time and its remarkable ability to mutate over a short period [36]. Researchers used molecular docking experiments to find alternative drugs that could serve as potential anti-COVID therapeutics. Many studies have shown that SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins interact with the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 ACE2 receptor, allowing the virus to fuse with the host cell membrane causing a viral infection. Therefore, the development of Spike-ACE2 protein-protein inhibitors could be used to prevent the infection process of SARS-CoV-2 [37], [38], [39].

Consequently, molecular docking studies have been performed to investigate the potential ability of these compounds as antiviral agents against coronavirus. The findings are promising in terms of binding energies towards the active residues of ACE2 and spike protein. Compound (7a) has shown an affinity of −9.1 kcal/mol to the ACE2 receptor compared to the MLN-4760 inhibitor (−7.3 kcal/mol) and was competitive with the natural ligand angiotensin II (−9.2 kcal/mol), and an affinity score of −7.3 kcal/mol against the S protein compared to the reference CBDA (−5.7 kcal/mol) that have been demonstrated to bind to the spike protein and prevent cell entry. Furthermore, in silico ADMET and drug-likeness properties studies were carried out to assess the potential pharmacokinetic and pharmacological characteristics which expressed promising drug-like characteristics.

2. Experimental section

2.1. General information and materials

Chemicals and solvents were reagent grade purchased from commercial suppliers and used as received with no further purification. All compounds and reactions were routinely checked and monitored by TLC performed on commercially prepared aluminum plates pre-coated with silica gel Merck 60 F254. The 1H and 13C NMR were recorded in CDCl3 as solvent using a JNM-ECZ500R/S1 FT NMR SYSTEM (JEOL) spectrometer operating at 500 MHz for 1H and 126 MHz for 13C. CDCl3 was chosen as solvent due to its high purity, and greater solubility of the molecules under investigation, Additionally, it is a commonly used solvent for NMR spectroscopy studies of organic compounds. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) and the residual solvent peak was used as an internal reference. Mass spectra have been recorded using the electrospray ionization (ESI) technique on Thermo Scientific TSQ 8000 Evo Triple Quadrupole GC-MS/MS spectrometry. Additionally, FT-IR spectra were obtained on JASCO FT/IR-4700 spectrophotometers, and IR absorption was expressed in wavenumber (cm−1). Mp of the new compounds was measured with a Stuart melting point apparatus SMP20.

2.2. Synthesis

2.2.1. General procedure for gram scale preparation of precursors 3, 4, and 5

Initially, a mixture of 1 (2-Aminopyrimidine, 0.1 mol) and 2 (2-Bromoacetophenone, 0.1 mol) in acetone (100 ml) was stirred overnight at ambient temperatures. After completion of the reaction (monitored by TLC), the precipitated product was filtered and washed with acetone to yield compound 3 (2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine). The 3-nitroso derivative was obtained by direct nitrosation using a saturated sodium nitrite solution which was added to 3 (0.1 mol) in acetic acid (100 ml) under stirring for 5 h, the mixture was treated with water resulting in the formation of a green solid filtered and washed to give the product 4 (3-nitroso-2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine) in good yield. Finally, to a cold stirred mixture of tin powder (2eq) and concentrated hydrobromic acid (50 ml), the 3-nitroso derivative 4 (0.1 mol) was added slowly, and the temperature was maintained at −10 °C for 2 h and then kept overnight at room temperature. The resulting solution was filtered and alkalinized to pH=9, extracted with Chloroform, dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure, then recrystallized from absolute ethanol to give sufficiently pure product 5 (2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidin-3-amine) to be used in the next step without any further purification.

2.2.2. General procedure for the preparation of Schiff base heterocycles of imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine nucleus 7a–e

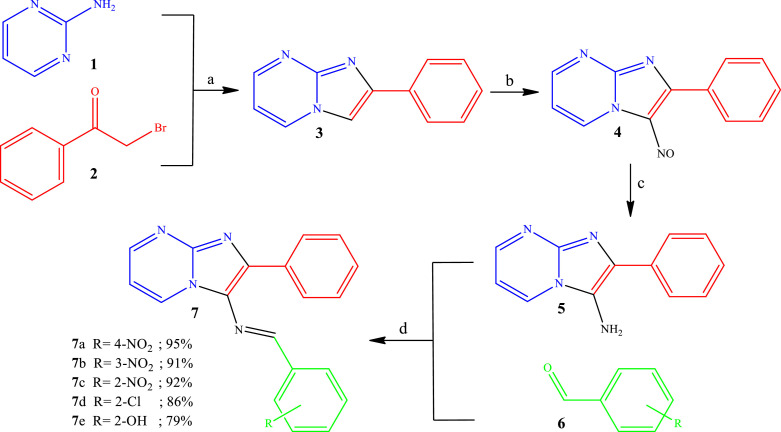

To a stirred solution of 5 (20 mmol) and substituted aldehydes 6 (20 mmol) in ethanol (50 ml), two drops of acetic acid as a catalyst were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The progress of the reaction was routinely checked and monitored by TLC. After completion of the reaction, the precipitated compound was filtered and washed with absolute cold ethanol to obtain an analytically pure product with high yields. A general approach to synthesizing the desired compounds is outlined in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

The general route for the synthesis of compounds 7a–e. Reagents and conditions: a) Acetone, rt, overnight; b) NaNO2, acetic acid, rt, 5 h; c) Sn Powder, HBr 48%, −10 °C for 2 h then overnight at rt; d) Acetic acid, Ethanol, rt, 24 h.

2.3. Theoretical studies

2.3.1. Quantum chemical calculations

Quantum chemical simulations, based on Density Functional Theory (DFT) have been a valuable tool in determining optimized molecular structures and reactive sites in chemical systems [40]. The relationship between molecular structure and biological activity has been extensively explored, and it has been established that these properties are largely influenced by electron density, as well as other factors such as steric effects and orbital character of donor-acceptor electrons [41,42]. Therefore, DFT was used to clarify the correlation between the molecular structures of the prepared Schiff bases and their associated activities. For the optimal geometries, the Gaussian 09 package[43] was employed to investigate quantum chemical calculations using DFT, at Becke's three-parameter hybrid functional (B3) [44] combined with gradient corrected correlation functional of Lee–Yang–Parr (LYP) [45], using 6–31 G(d,p) basis set. The B3LYP functional combined with the 6–31 G(d,p) basis set is a commonly used DFT method in quantum chemical calculations for small and medium-sized molecules due to its balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. This method can provide insights into the structural and dynamic properties of molecules. It has been particularly useful in studying ligand-protein interactions, predicting binding modes and affinities, and drug design. Overall, the B3LYP/6–31 G(d,p) method is a powerful and versatile tool for investigating noncovalent interactions in various research areas. Many studies report a satisfactory concurrence between the theoretical and experimental geometrical parameters, which has proven to accurately predict the molecular properties of organic compounds [46], [47], [48], [49]. Additionally, the Gauss View 6 [50] program was utilized to calculate and plot the vibrational frequencies, frontier molecular orbitals, and the Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP) for the molecules.

In this study, various chemical indices were calculated, including the energy of the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO), the energy of the Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO), the energy gap (ΔEgap = ELUMO-EHOMO), the global electrophilicity index (ω), absolute electronegativity (χ), absolute hardness (η), softness (σ), and dipole moment (μ). All the quantum parameters are calculated using the following formula [51,52].

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

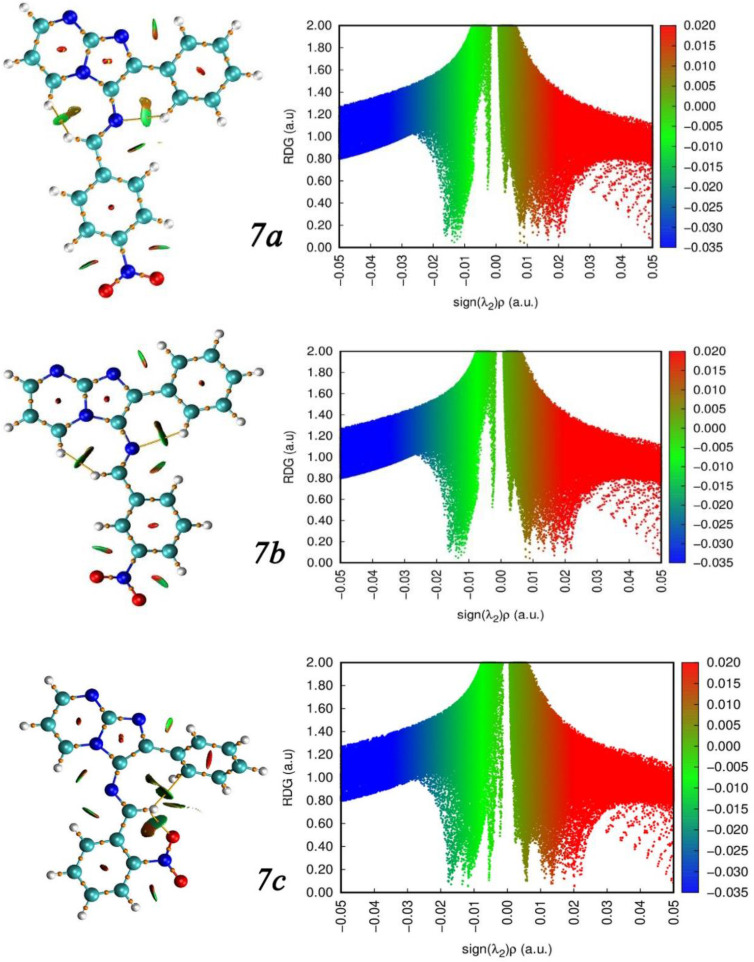

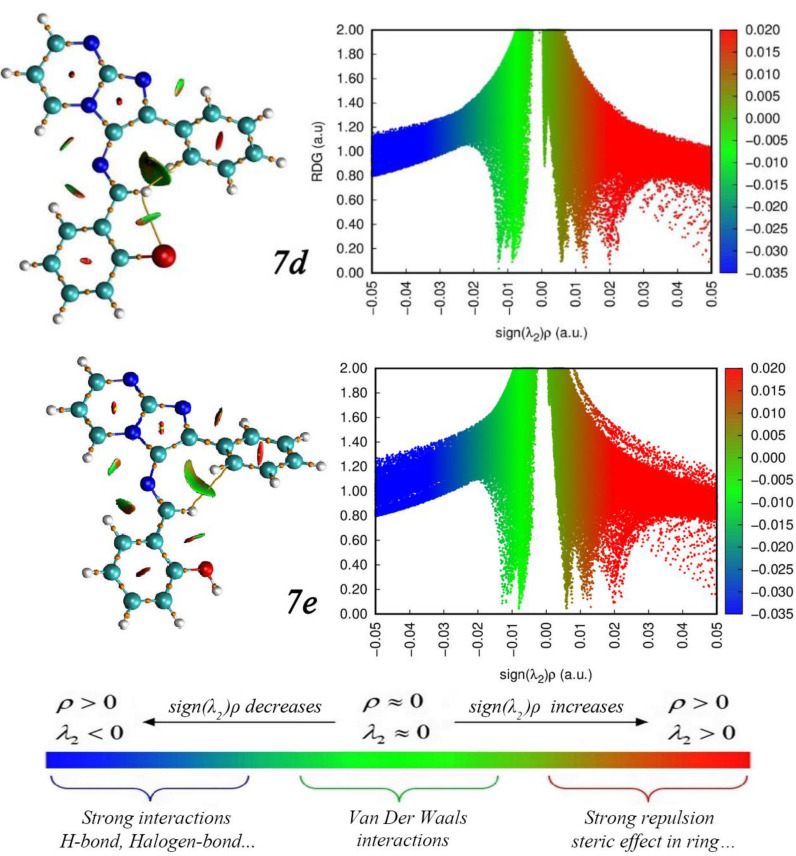

The Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecule (QTAIM) analysis is performed based on the electronic density topology. The molecular structure optimization generates a wfn file, which is loaded into the Multiwfn software. The Bond Critical Point (BCP) creates links between critical sites of interacting atoms, and the 3D molecular structure shows the type and strength of interactions through the blue-green-red isosurface. Blue indicates strong attractive interactions (negative region of sign(λ2)), green shows van der Waals interactions (near-zero region of sign(λ2)), and red represents repulsive interactions (positive region of sign(λ2)) [43]. By plotting the Reduced Density Gradient (RDG) on the y-axis and sign(λ2) on the x-axis, the corresponding 2D scattering plot is obtained. The peaks present in the graph correspond to the interactions present in the 3D graph. The QTAIM 3D and 2D graphs were generated using VMD and Gnuplot tools [53,54].

2.3.2. Molecular docking studies

Molecular docking experiments represent a powerful tool in computer-aided drug design, enabling the prediction of the binding modes and affinities of small molecules with target proteins. In this study, virtual screening targeting the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, key severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 entrance proteins, was performed to predict the binding affinity of the targeted receptors and the potential inhibitors. ACE2 and the spike RBD crystal structures were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 7U0N). Molecular docking experiments were conducted to study the binding interactions between the newly synthesized compounds against ACE2 and S protein, using MLN-4760 (CID: 448281) and angiotensin II (CID: 172198) as reference compounds for ACE2 docking. While cannabidiolic acid (CBDA) (CID: 160570) was used as a reference for spike docking. Notably, the infection inhibition assay findings reported by (B. van Breemen et al. 2022) [55], demonstrated that CBDA was able to block SARS-CoV-2 cell entry, thereby preventing the infection process.

The newly synthesized compounds and the targeted proteins were prepared and optimized with AutoDock Tools [56]. The molecular docking study was carried out using PyRx. The grid box for ACE2 protein was mainly centered on the XYZ coordinates as −12.217, 39.173, and 4.536 respectively, and with XYZ grid size of 25.000, 23.124, and 47.241 Å respectively. Similarly, for the spike RBD, the grid was centered on these XYZ coordinates as 12.191, 43.828, and −17.938 respectively, and with XYZ grid size of 18.557, 23,323, and 37.404 Å respectively. The resulting interactions between the protein's active site and ligands were processed and visualized in 2D and 3D utilizing PyMOL [57] and Discovery Studio Visualizer [58].

2.3.3. Drug likeness and ADMET prediction

Evaluating pharmacokinetic and physicochemical properties is an essential step in drug discovery, as it helps identify compounds with optimal drug-like properties that can be developed into safe and effective drugs. In this study, the SwissADME server [59] was employed to predict several parameters such as molar refractivity, partition coefficient (Log P), Rotatable bonds, Hydrogen Bond Acceptor-Donor (HBA-D), and Topological Surface Area (TPSA). Moreover, the pkCSM tool [60] was used to predict the ADMET properties. This tool provides detailed information on various attributes that could impact the safety and efficacy of the compound as a potential drug candidate. The examination was performed based on recognized medicinal chemistry criteria, ensuring the selected compounds for further investigation have the potential to be developed into safe and effective drugs.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Chemistry

In the present work, new Schiff base heterocycles of imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine nucleus were prepared following a four-step synthetic protocol according to the literature procedure. Initially, the intermediate 3 (2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine) was obtained by the condensation of commercially available 1 (2-Aminopyrimidine) with 2 (2-Bromoacetophenone) [9]. The 3-nitroso derivative 4 (3-nitroso-2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine) was obtained by direct nitrosation using sodium nitrite [61]. A reduction treatment on the nitroso derivative 4 yielded the 3-amino product 5 (2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidin-3-amine) [61]. The new series of Schiff base derivatives were prepared by condensation of the 3-amino product 5 with different substituted aldehydes 6 to give the corresponding pure products in very good yields (Fig. 2 ).

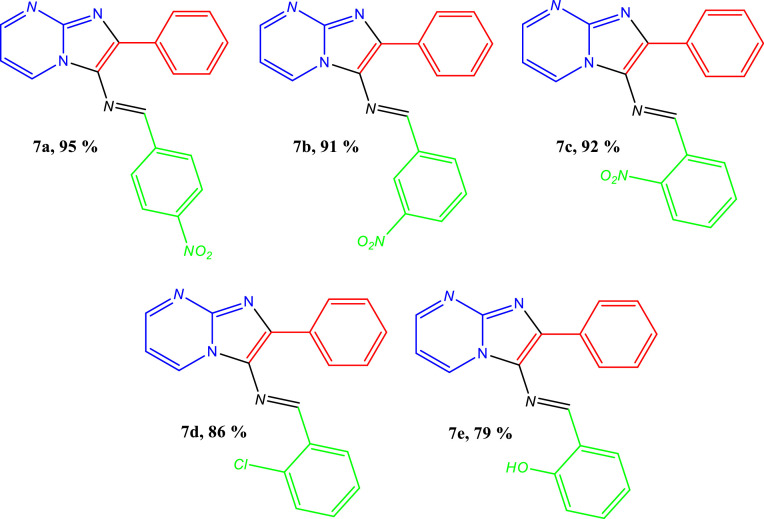

Fig. 2.

Chemical structures of compounds 7a–e.

The structure of all novel imines was confirmed by analytical and spectral data. NMR spectra of compounds 7a–e revealed the expected characteristic protons. 1H NMR spectra displayed the presence of a singlet at δ 8.83–9.32 ppm corresponding to the proton of the imine group (N CH). While 13C NMR spectra displayed a characteristic peak at δ 150.35–153.97 ppm due to the (N CH)group. Moreover, additional confirmation was obtained by IR spectra of 7a–e showed an absorption band at 1605–1598 cm−1 indicating (C = N) stretching vibration, which confirmed the formation of the predicted Schiff base heterocycles derivatives (see Supplementary file).

3.1.1. (E)-N-(4-nitrobenzylidene)−2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidin-3-amine (7a)

Obtained from 4-Nitrobenzaldehyde as a red powder; yield 95%. mp; 255–257 °C. FT-IR (ʋmax/cm−1): υ(C—H) = 3104, 3055; υ(C = N) = 1604; υ(C = C) = 1580; υ(N = O) = 1513, 1335; υ(C—N) = 1214;υ(C—C) = 1103.1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.89 (s, 1H), 8.77 (dd, J = 6.8, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.62 (dd, J = 4.1, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.94 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.86 – 7.80 (m, 2H), 7.51 – 7.41 (m, 2H), 7.41 (tt, J = 7.3, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.01 (dd, J = 6.8, 4.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.47, 151.10, 149.19, 146.92, 141.77, 137.60, 133.94, 131.14, 129.14, 129.11, 128.85, 128.77, 126.38, 124.21, 109.46. LC-MS (ESI): m/z = 344.11 (M + 1).

3.1.2. (E)-N-(3-nitrobenzylidene)−2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidin-3-amine (7b)

Obtained from 3-Nitrobenzaldehyde as a golden powder; yield 91%. mp; 230–232 °C. FT-IR (ʋmax/cm−1):υ(C—H) = 3116, 3079; υ(C = C) = 1601; υ(N = O) = 1515, 1345; υ(C—N) = 1209;υ(C—C) = 1066. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.90 (s, 1H), 8.78 (dd, J = 6.8, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.68 (s, 1H), 8.62 (dd, J = 4.1, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 8.29 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.63 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.53 – 7.43 (m, 2H), 7.46 – 7.37 (m, 1H), 7.01 (dd, J = 6.8, 4.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.97, 150.94, 148.91, 146.70, 137.98, 137.03, 133.96, 131.12, 130.02, 129.17, 129.04, 128.73, 126.25, 125.64, 122.52, 109.37.LC-MS (ESI): m/z = 344.11 (M + 1).

3.1.3. (E)-N-(2-nitrobenzylidene)−2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidin-3-amine (7c)

Obtained from 2-Nitrobenzaldehyde as a golden powder; yield 92%, mp; 215–217 °C. FT-IR (ʋmax/cm−1): υ(C—H) = 3110, 3066; υ(C = N) = 1604; υ(C = C) = 1563; υ(N = O) = 1518, 1341; υ(C—N) = 1207;υ(C—C) = 1075. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.25 (s, 1H), 8.75 (dd, J = 6.8, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.59 (dd, J = 4.1, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.25 (dd, J = 7.9, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (dd, J = 7.0, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.74 – 7.65 (m, 1H), 7.57 (ddd, J = 8.4, 7.4, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (dd, J = 7.6, 7.0 Hz, 2H), 7.40 (tt, J = 7.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (dd, J = 6.8, 4.1 Hz, 1H).13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.95, 150.56, 149.07, 146.77, 138.35, 133.58, 133.25, 131.24, 130.82, 129.18, 129.08, 129.04, 128.94, 126.15, 124.79, 109.46.LC-MS (ESI): m/z = 344.11 (M + 1).

3.1.4. (E)-N-(2-chlorobenzylidene)−2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidin-3-amine (7d)

Obtained from 2-chlorobenzaldehyde as a yellow powder; yield 86%, mp; 180–182 °C. FT-IR (ʋmax/cm−1): υ(C—H) = 3104, 3072; υ(C = N) = 1605; υ(C = C) = 1588; υ(C—N) = 1218;υ(C—C) = 1065; υ(C—Cl) = 750.1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.32 (s, 1H), 8.72 (dd, J = 6.7, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.56 (dd, J = 4.0, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.31 – 8.22 (m, 1H), 7.87 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.4 Hz, 2H), 7.45 (dd, J = 8.6, 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (tt, J = 7.6, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.39 – 7.30 (m, 3H), 6.94 (dd, J = 6.7, 4.0 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) 153.84, 150.45, 146.41, 136.78, 136.11, 133.91, 133.44, 132.36, 130.96, 130.24, 129.01, 128.75, 128.69, 127.71, 127.15, 127.05, 109.11.LC-MS (ESI): m/z = 333.08 (M + 1).

3.1.5. (E)−2-(((2-phenylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidin-3-yl)imino)methyl)phenol (7e)

Obtained from 2-Hydroxybenzaldehyde as a brown powder; yield 79%, mp; 210–212 °C. FT-IR (ʋmax/cm−1): υ(O—H) = 3195; υ(C—H) = 3110, 3067; υ(C = N) = 1598; υ(C = C) = 1565; υ(C—O) = 1445; υ(C—N) = 1215.1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.31 (s, 1H), 8.83 (s, 1H), 8.58 (dd, J = 4.0, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.47 (dd, J = 6.8, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.5 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (ddd, J = 8.4, 7.1, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.43 – 7.38 (m, 2H), 7.36 (tt, J = 7.4, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (dd, J = 6.8, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (ddd, J = 7.7, 7.1, 1.1 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 164.30, 160.91, 150.35, 145.88, 135.71, 134.14, 133.35, 132.73, 129.94, 129.15, 128.77, 128.35, 125.59, 119.88, 119.03, 117.44, 109.37.LC-MS (ESI): m/z = 315.12 (M + 1).

3.2. Green metrics calculations

Additionally, we performed green metrics calculations of the most commonly used metrics such as Carbon Efficiency (CE), Atom Economy (AE), Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME), Mass Intensity (MI) and E-factor which have been proposed in the last decade, as a measure of environmental sustainability in terms of minimization theoretical waste amount [62].

In the preceding analyses, the green metrics were calculated using literature procedures [63]. Were the reagents in catalytic quantities and the amount of solvents or any recoverable materials were not considered in the calculations since they are assumed to be recycled or can be reused. In an ideal condition, CE, AE, and RME would be close to 100%, while MI would be close to 1 and E-Factor close to 0 [64].

Table 1 represents the green metric calculations of the synthesized compounds. The results indicate that the reactions have good to excellent green metrics. For compounds 7a-e, the %CE, %AE, and %RME are all high, while the MI values are relatively low, indicating that the reactions have excellent atom economy and maximum conversion of starting materials into product.

Table 1.

Green metrics calculations of synthesized derivatives.

| Step | Substrate | % Yield | % CE a | % AE b | % RME c | MI d | E-Factor e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. | 3 | 96 | 96 | 66.36 | 63.71 | 1.56 | 0.56 |

| b. | 4 | 98 | 98 | 84.86 | 83.18 | 1.20 | 0.20 |

| c. | 5 | 83 | 91 | 79.94 | 85.32 | 1.17 | 0.17 |

| d. | 7a | 95 | 95 | 95.01 | 90.30 | 1.10 | 0.10 |

| 7b | 91 | 91 | 95.01 | 86.56 | 1.15 | 0.15 | |

| 7c | 92 | 92 | 95.01 | 87.39 | 1.14 | 0.14 | |

| 7d | 86 | 86 | 94.86 | 81.71 | 1.22 | 0.22 | |

| 7e | 79 | 79 | 94.58 | 74.69 | 1.33 | 0.33 |

Carbon efficiency.

Atom economy.

Reaction mass efficiency.

Mass Intensity.

E-factor.

It is important to note that the precursors can be prepared with different reactants and conditions, resulting in significant improvements in the green metrics parameters. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that the four-step synthetic protocol reported here follows several green chemistry principles and takes place at room temperature and under normal pressure.

3.3. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations

3.3.1. Geometry optimization

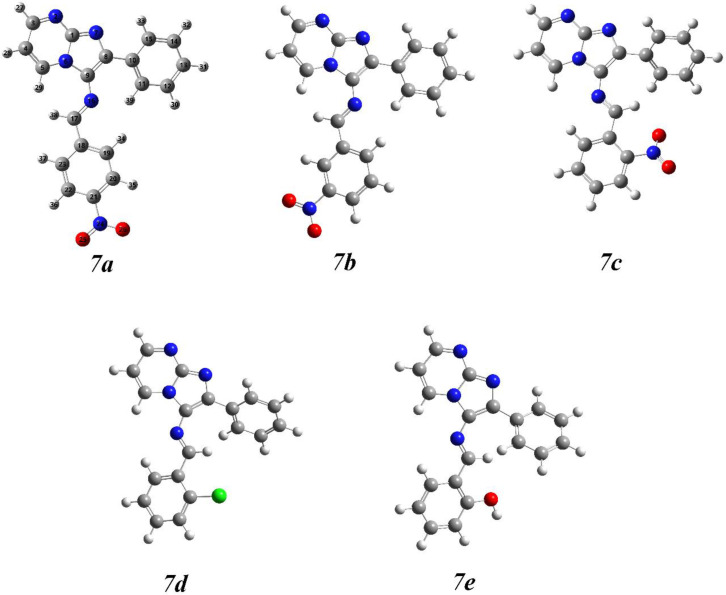

The molecular modeling study plays a crucial role in understanding the relationship between the molecular structure and its reactivity. The results of the molecular modeling of the synthesized molecules are presented in this section, including the quantum chemistry calculations performed using the DFT method.

Primarily molecular structure optimization of 7a-e was performed using density functional theory to obtain the most stable ground state geometry. DFT calculations were performed at the B3LYP level of theory [44,45], using 6–31 G(d,p) basis set. Additionally, the molecular modeling results indicate that the compounds' chemical configurations are local minimum energy structures, as confirmed by vibrational frequency calculations that showed the absence of an imaginary wave number. Therefore, the stable gas phase configurations (minimal energy geometries) are shown in Fig. 3 .

Fig. 3.

The optimized molecular structures of 7a-e.

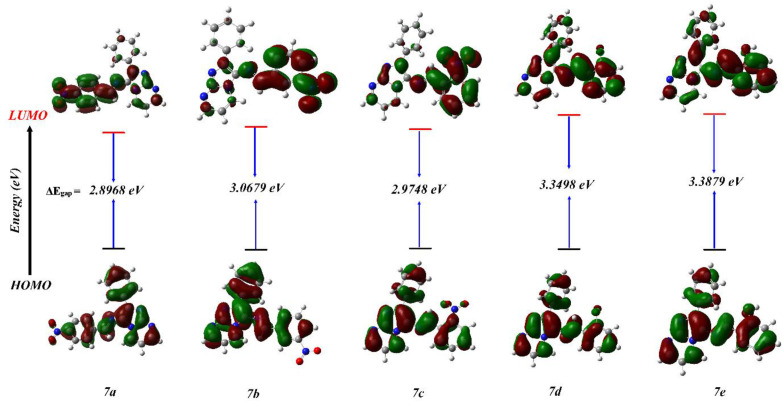

3.3.2. The frontier molecular orbitals (FMO) analysis

The analysis of frontier molecular orbitals is crucial in quantum chemistry for studying the mobility of electronic charges in a molecular system [65]. It examines the energy difference between the HOMO and the LUMO [66]. These two orbitals referred to as "frontier" orbitals, serve the same role as chemical valence orbitals, the HOMO is related to the electron-donating character of the molecule, while, the LUMO provides insight into the electron-accepting character of the molecule [67]. Further, the energy gap between the HOMO and the LUMO, also known as the HOMO-LUMO gap, is a measure of the stability of a molecule and its ability to donate or accept electrons. In the context of biological activity, the energy gap is important because it determines how reactive a molecule is to other molecules and how easily it can participate in chemical reactions such as binding to proteins or enzymes [68]. A small energy gap indicates a more reactive molecule, while a large energy gap indicates a less reactive and more stable molecule. Therefore, the energy gap is a fundamental factor in understanding the biological activity of molecules and their potential as therapeutic agents.

The representations of frontier molecular orbitals for the optimized structures are depicted in Fig. 4 . The green and red regions represent the MOs with opposite total phases. The positive phase of the molecule is depicted in red color and the negative phase in green [69]. It is obvious from the figure that, the HOMOs are localized mainly over the entire molecules. On the other hand, the LUMOs are located principally on the substituted phenyl nuclei. The ΔEgap values for the five molecules are ordered as follows: 7a < 7c < 7b < 7d < 7e. Among the five molecules studied, it was observed that molecule 7a displays the smallest energy gap with a value of 2.8968 eV, which enhances its reactivity and facilitates its interaction with other species [70]. This property could make molecule 7a useful in various biological processes, such as in drug design and development, as well as in other areas where reactivity and interaction with biological systems are important. While the highest value is presented by molecule 7e with a value of 3.3879 eV, making it less reactive compared to the other molecules.

Fig. 4.

Correlation diagram between HOMO and LUMO of 7a-e.

To enhance the discussion on the electron interaction and chemical reactivity of the studied compounds [71], various theoretical parameters were determined and presented in Table 2 , such as molecular orbital energies (EHOMO, ELUMO), the energy gap (ΔE), global hardness (η) and softness (σ), the absolute electronegativity (χ), the global electrophilicity index (ω) and the dipole moment (μ),.

Table 2.

Global reactivity descriptors of 7a-e.

| Quantum parameters | 7a | 7b | 7c | 7d | 7e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EHOMO (eV) | −5.8185 | −5.7453 | −5.6638 | −5.4589 | −5.2095 |

| ELUMO (eV) | −2.9217 | −2.6775 | −2.689 | −2.1091 | −1.8216 |

| ΔEgap (eV) | 2.8968 | 3.0679 | 2.9748 | 3.3498 | 3.3879 |

| η (eV) | 1.4484 | 1.5339 | 1.4874 | 1.6749 | 1.6939 |

| σ (eV-1) | 0.6904 | 0.6519 | 0.6723 | 0.597 | 0.5903 |

| χ (eV) | 4.3701 | 4.2113 | 4.1764 | 3.784 | 3.5155 |

| ω (eV) | 6.5927 | 5.7808 | 5.8633 | 4.2744 | 3.648 |

| µ (Debye) | 4.7699 | 1.5451 | 6.3526 | 5.1072 | 6.1960 |

Typically, high reactivity is favored by low global hardness values and high global softness values . [72] In our study, it is evident that the low hardness value (1.4484 eV) and high softness value (0.69040 eV) reflect the reactivity of the synthesized compounds. Table 2 shows that 7a has a low hardness value (1.4484 eV) and a high softness value (0.69040 eV), which explains this molecule's important inhibitory and biological activity compared to the others. However, the significant values of electronegativity (χ) and electrophilicity index (ω) in the same molecule indicate its potential to interact with receptors by the transfer of electrons. [73] as a result, this leads to an increase in its binding capacity.

The dipole moment of a molecule, as determined by the value of µ (Debye), is a critical parameter that reflects the separation and the distribution of electrical charge within the molecule, which can affect various physical and chemical properties, including solubility, reactivity, and intermolecular interactions [74]. Molecules with larger dipole moments are more polar and have the potential to interact more strongly with other polar molecules or charged species, such as solvents or proteins. Therefore, the calculated dipole moments of the synthesized compounds could help understand their behavior in biological environments and their potential for drug design applications [75].

The values of the dipole moment, as represented by the µ (Debye) values, for compounds 7a-e are different, which suggests that these molecules have different polarity levels. Compound 7c has the highest dipole moment value of 6.3526 Debye, indicating that it is the most polar among the five studied compounds. On the other hand, compound 7b has the lowest dipole moment value of 1.5451 Debye, which suggests it is the least polar among the studied compounds.

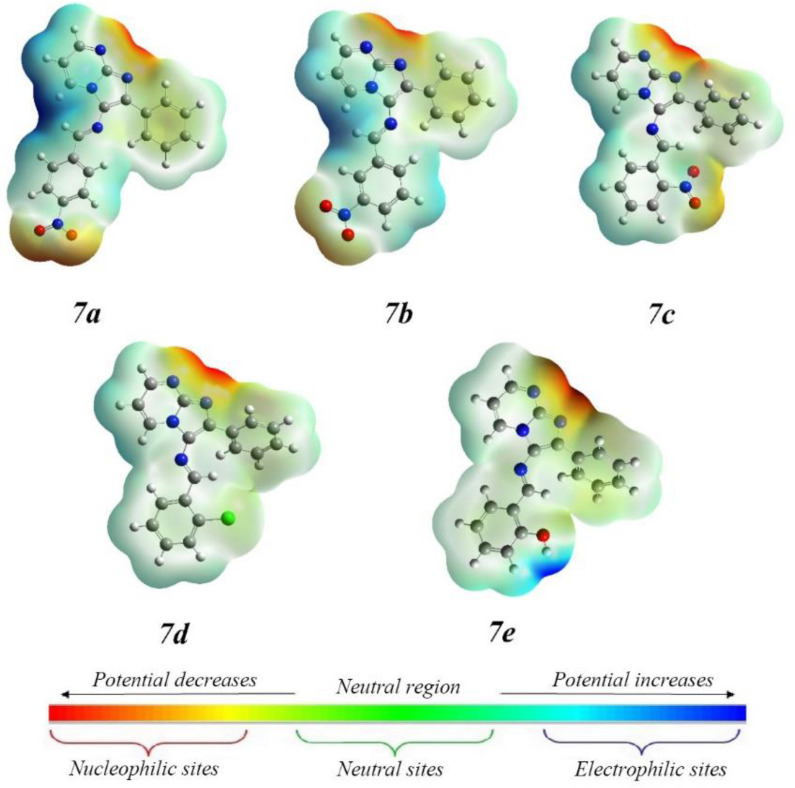

3.3.3. Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) analysis

The Molecular Electrostatic Potential surface (MEP) of the studied compounds was determined to gain insight into the distribution of electrostatic potential around each molecule which is mainly determined by the charge and distribution of electrons [76]. The MEP, [77] serves as a primer descriptor for comprehending the relationship between molecular structure and biological activity [78,79]. This descriptor is particularly valuable for identifying electrophilic and nucleophilic reaction sites, as well as the interactions involving hydrogen bonding. Thus, a color spectrum is utilized to distinguish the different levels of electrostatic potential energy to make the data easily interpretable. The red color represents the lowest potential which indicates a negative charge that is supposed to be the nucleophilic attack and protonation sites, while the blue color represents the highest potential which denotes a positive charge and indicates the electrophilic sites on the molecule of interest, while green color marks zero potential regions in terms of electron density [70].

The MEP maps generated at the optimized geometries of the studied compounds, using the Gauss View 6 software, are illustrated in Fig. 5. In all compounds, the regions localized around the nitrogen atoms N2 and N7 of the imidazopyrimidine moiety, along with the NO2 group in 7a-c (red color) represent the most electron-rich regions, with high affinity for electrophiles, therefore they are anticipated to be sites of nucleophilic attack. However, the MEP maps show the presence of electron-accepting regions (blue color) localized around the hydrogen atoms bonded to carbons C4, C5, and C17 of compounds 7a and 7b as well as around the hydrogen of the OH group in compounds 7e, which indicate electrophilic sites that could attract nucleophilic moieties. As a result, these sites give information about the region from which the compounds can interact intermolecularly .

Fig. 5.

MEP of 7a-e.

3.4. Quantum theory of atoms in molecule (QTAIM) analysis

The quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) is a computational method for analyzing the nature of chemical bonds and interactions in molecular systems. It uses quantum mechanics to calculate electron densities and to identify bond critical points, where bonds can be formed or broken [80]. The QTAIM approach can be used to determine various topological parameters, such as the electron density Laplacian, kinetic energy density, and potential energy density. It can provide a deeper understanding of chemical reactions, molecular stability, and reactivity [81].

In the present work, the analysis and visualization of non-covalent interactions were performed using the QTAIM molecular graph. As a result, the investigated compounds contain various intra-molecular interactions such as van der Waals interactions corresponding to (H....H) and (N....H) connections that appeared in compounds 7a and 7b, with sign(λ2)ρ (< −0.01 a.u), and (O….H), (Cl….H) connections observed in compounds 7c and 7d respectively, which are indicated by the critical points (CPs), in addition of intra-molecular hydrogen bond interactions that are marked by the green bonds in Fig. 6 . The red color at the center of the benzene rings denoted ring strain (steric repulsion). These interactions are indicated by the presence of the peak at positive sign (λ2)ρ values (> 0.02 a.u) [82]. Moreover, the presence of these different types of intermolecular interactions with different strengths and natures such as hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions can affect the reactivity and behaviors of molecules in different ways.

Fig. 6.

The RDG and NCI interactions analysis of 7a-e.

3.5. Molecular docking analysis

The molecular docking studies of the newly synthesized compounds 7a-e, toward the highly contagious and fast-spreading Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 entrance proteins, were investigated. The obtained docking scores based on the best binding pose for each compound are shown in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Molecular docking scores of 7a-e, the hACE2 natural ligand angiotensin II, its inhibitor MLN-4760, and the spike entrance blocker CBDA.

| Ligands | Smile and CID | hACE2 docking score (Kcal/mol) | Spike docking score (Kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7a | [O-][N+](=O)c1ccc(cc1)/C = N/c1c(nc2n1cccn2)c1ccccc1 | −9.1 | −7,3 |

| 7b | [O-][N+](=O)c1cccc(\C = N\c2c(nc3ncccn23)-c2ccccc2)c1 | −8.9 | −6.6 |

| 7c | [O-][N+](=O)c1ccccc1\C = N\c1c(nc2ncccn12)-c1ccccc1 | −8.7 | −6.2 |

| 7d | Clc1ccccc1\C = N\c1c(nc2ncccn12)-c1ccccc1 | −8.7 | −6.7 |

| 7e | Oc1ccccc1\C = N\c1c(nc2ncccn12)-c1ccccc1 | −8.7 | −6.5 |

| angiotensin II | 172198 | −9.2 | – |

| MLN-4760 | 448281 | −7.3 | – |

| CBDA | 160570 | – | −5.7 |

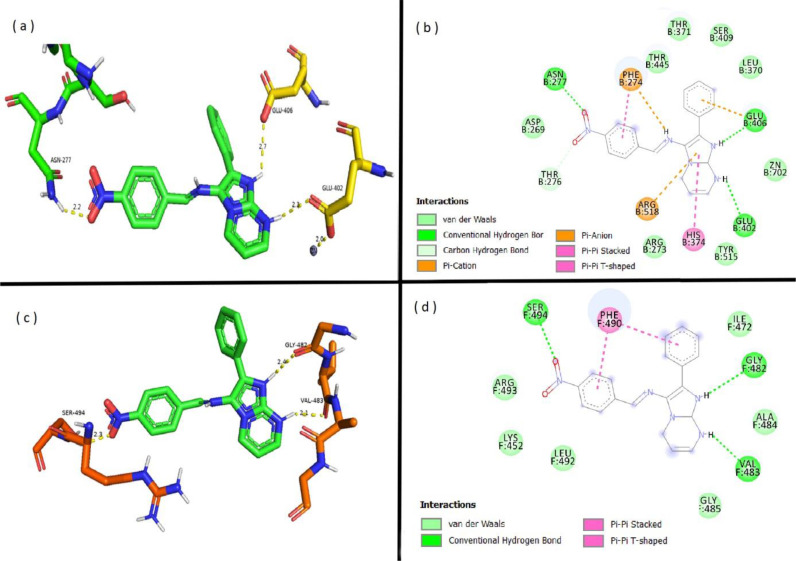

The binding score suggests that all docked compounds display binding affinity against the targeted proteins. Notably, compound 7a showed the most promising results along with ACE2 and the spike protein. This top-scoring compound exhibited a higher affinity (−9.1 kcal/mol) to the ACE2 receptor compared to the MLN-4760 inhibitor (−7.3 kcal/mol) and was competitive with the natural ligand, angiotensin II (−9.2 kcal/mol). The chemical interaction of this compound with ACE2 showed a stable interaction with three H-bonds with ASN277, GLU402, and GLU406 residues, with distances of 2.2, 2.3, and 2.7 Å, respectively. Additionally, there was a Pi-anion/Pi-cation and Pi-Pi T-shaped interaction with PHE274, and Pi-anion/Pi-cation with ARG518, and a Pi-Pi stacked interaction with HIS374.

In the case of spike protein docking studies, molecule 7a also showed a remarkably higher binding affinity of −7.3 kcal/mol compared to the entrance blocker CBDA, which had an affinity of −5.7 kcal/mol. Its chemical interaction with the spike also showed a stable interaction with three H-bonds to residues GLY482, VAL483, and SER494, with distances of 2.4, 2.1, and 2.3 Å, respectively. Notably, SER494 is one of the major residues of the spike protein's Receptor-Binding Domain (RBD). In addition, there was a Pi-Pi T-shaped interaction with PHE490 (Fig. 7 ) . These results suggest that molecule 7a may act as a potential dual inhibitor of both ACE2 and spike protein, making it a promising candidate for further development as a therapeutic agent against SARS-CoV-2 and its variants.

Fig. 7.

3D and 2D interaction views of the potential inhibitor 7a with ACE2 and spike proteins.

(a) 3D model showing inhibitor 7a's interaction with the active site of ACE2.

(b) 2D model showing inhibitor 7a's interaction with the active site of ACE2.

(c) 3D model showing inhibitor 7a's interaction with the RBD of the spike protein.

(d) 2D model showing inhibitor 7a's interaction with the RBD of the spike protein.

3.6. Physicochemical and drug-likeness properties

Drug-likeness properties refer to a set of criteria used to evaluate whether a compound has the potential to become a drug. These properties are evaluated based on several criteria, including molecular weight, lipophilicity (log P), Molar refractivity, HBA, HBD, number of rotatable bonds, and TPSA. Among these, Lipinski's rule [83] of five is a widely used guideline for evaluating drug-likeness, which emphasizes that a molecule is more likely to be orally bioavailable if it meets specific parameters, such as having a molecular weight of less than 500, a log P less than 5, no more than 5 H-bond donors, no more than 10 H-bond acceptors, and a TPSA of less than 140 Å2.

The physicochemical parameters obtained from the SwissADME server (Table 4 ) are within the accepted range revealing that the potential inhibitors 7a-e fully obeyed Lipinski's rule [83], suggesting they have favorable properties such as optimal size, flexibility, and polarity that positively associate with good bioavailability. However, The ADME prediction (Table 5 ) has shown a promising result, revealing that all compounds adhere to other essential drug-likeness rules, including Ghose et al. [84], [85], [86], [87] and display good bioavailability scores of 0.55. These findings suggest that the newly synthesized compounds hold significant potential as drug candidates and could be further investigated for their therapeutic properties.

Table 4.

Predicted physicochemical properties of 7a-e along with MLN-4760 as a reference by the SwissADME server.

| Compound | MWa (<500) | TPSAb (<140A˚2) | HBAc (<10) | HBDd (<5) | RBe (<5) | LogPf (<5) | Lipinski's Violation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7a | 343.34 | 88.37 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 3.11 | 0 |

| 7b | 343.34 | 88.37 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 3.09 | 0 |

| 7c | 343.34 | 88.37 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 3.08 | 0 |

| 7d | 332.79 | 42.55 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 4.21 | 0 |

| 7e | 314.34 | 62.78 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3.32 | 0 |

| MLN-4760 (reference) | 428.31 | 104.45 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 2.06 | 0 |

Molecular weight.

Topological polar surface area.

Number of hydrogen bond acceptor.

Number of hydrogen bond donor.

Number of rotatable bonds.

Consensus of calculated lipophilicity.

Table 5.

Drug-likeness properties of 7a-e along with MLN-4760 as a reference by the SwissADME server.

| Compound | Lipinski | Ghose | Veber | Egan | Muegge | Bioavailability Score | Lipinski's Violation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.55 | 0 |

| 7b | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.55 | 0 |

| 7c | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.55 | 0 |

| 7d | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 0.55 | 0 |

| 7e | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.55 | 0 |

| MLN-4760 (reference) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0.55 | 0 |

3.7. ADMET properties of the potential inhibitors

The ADMET properties of a potential drug candidate are essential for determining its suitability for clinical use. In addition to being effective at low doses and having low toxicity, the drug candidate should have adequate pharmacokinetic properties that ensure the availability of the drug molecules in an active form for the desired duration of action. In silico evaluation of ADMET properties can significantly aid in predicting the behavior of a drug candidate in the body, thus simplifying and accelerating the drug discovery process and minimizing the risk of failure during clinical trials. Therefore, a thorough assessment of ADMET properties is critical for successfully developing and commercializing new drugs [88,89].

Based on the results obtained in Table 6 , the potential inhibitors have moderate water solubility and high intestinal absorption by the human intestine (91.21% - 93.18%) which guarantees excellent absorption. Additionally, The Caco2 permeability value suggests that the inhibitors have good intestinal permeability, which is encouraging and implies that these inhibitors may be well-suited for oral delivery. In addition, their Skin permeability is undoubtedly effective with an excellent dermal permeability rating. However, there are substrates of P-glycoprotein, but the fact that they inhibit P-glycoprotein I and II could potentially help to mitigate this issue by reducing the efflux of the inhibitors from cells, which may help increase their bioavailability [90,91].

Table 6.

In silico ADMET predictions of the potential inhibitors 7a-e.

| Property and Model Name | 7a | 7b | 7c | 7d | 7e | MLN-4760 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | ||||||

| Water solubility (log mol/L) | −2.965 | −2.972 | −2.958 | −2.957 | −2.945 | −2.892 |

| Caco2 permeability (log Papp in 10−6 cm/s) | 1.251 | 1.252 | 1.262 | 1.415 | 1.267 | 0.744 |

| Intestinal absorption in humans (% Ab) | 92.92 | 93.184 | 93.046 | 92.44 | 91.216 | 44.856 |

| Skin permeability (log Kp) | −2.736 | −2.736 | −2.736 | −2.74 | −2.741 | −2.735 |

| P-glycoprotein substrate (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| P-glycoprotein I inhibitor (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| P-glycoprotein II inhibitor (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Distribution | ||||||

| VDss in humans (log L/kg) | 0.065 | 0.118 | 0.198 | 0.209 | 0.173 | 0.011 |

| Fraction unbound in humans (Fu) | 0.079 | 0.075 | 0.071 | 0.087 | 0.091 | 0.381 |

| BBB permeability (log BB) | −0.945 | −0.976 | −1.002 | 0.555 | 0.323 | −1.403 |

| CNS permeability (log PS) | −1.887 | −1.886 | −1.876 | −1.294 | −1.848 | −3.238 |

| Metabolism | ||||||

| CYP2D6 substrate (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| CYP3A4 substrate (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| CYP1A2 inhibitor (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor (Yes/No) | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Excretion | ||||||

| Total Clearance (log ml/min/kg) | 0.252 | 0.182 | 0.212 | 0.406 | 0.431 | −0.144 |

| Renal OCT2 Substrate (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Toxicity | ||||||

| AMES toxicity (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Max. tolerated dose in humans (log mg/kg/day) | 0.372 | 0.374 | 0.366 | 0.425 | 0.422 | 0.438 |

| hERG I inhibitor (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| hERG II inhibitor (Yes/No) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Oral Rat Acute Toxicity (LD50) (mol/kg) | 2.573 | 2.569 | 2.564 | 2.805 | 2.793 | 2.482 |

| Oral Rat Chronic Toxicity (LOAEL) (log mg/ky_bw/day) | 1.236 | 1.257 | 1.304 | 0.951 | 1.083 | 2.35 |

| Hepatotoxicity (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Skin sensitization (Yes/No) | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| T. Pyriformis toxicity (log ug/L) | 0.285 | 0.285 | 0.285 | 0.285 | 0.285 | 0.285 |

| Minnow toxicity (log mM) | 0.342 | 0.19 | 0.183 | 0.097 | 0.756 | 0.635 |

When considering distribution, the inhibitors have low VDss and a low fraction unbound in humans, indicating a limited distribution in the body. They also have moderate to good Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB) and Central Nervous System (CNS) permeability values suggesting that they may not easily cross the BBB but may still be able to exert some effect within the CNS [92].

In terms of metabolism, the inhibitors are substrates and inhibitors for CYP3A4, which is an important enzyme involved in drug metabolism and can lead to complex drug-drug interactions. Yet they are not substrates for CYP2D6 that may be beneficial as this enzyme is known to have a high degree of genetic variability among individuals. Regarding excretion, the inhibitors have moderate total clearance and are renal OCT2 substrates. [93]

Finally, the potential inhibitors do not appear to be hepatotoxic or skin sensitizers, but were AMES toxicity positive. They also have some inhibitory effects on hERG II, which is an ion channel involved in cardiac function, but do not inhibit hERG I. The high maximum tolerated dose in humans (0.366–0.425 log mg/kg/day) is also a positive sign for their relatively safe profile.

Overall, these ADMET predictions can provide useful information for further evaluating the potential of these inhibitors as drug candidates. In addition to the in silico predictions, the actual pharmacokinetic properties must be evaluated in vitro and in vivo to confirm the effectiveness and safety of the drug candidate [94,95].

4. Conclusion

This study aimed to synthesize and evaluate new Schiff base heterocycles based on the imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine nucleus using a simple and efficient synthetic approach that adheres to several principles of green chemistry, enabling large-scale production. The synthesized compounds have been characterized using 1H, 13C NMR, LC-MS(ESI), and FT-IR spectral techniques.

Quantum chemical computations were carried out using DFT at B3LYP/6–31 G (d, p) basis set and the optimized parameters were investigated to predict and to understand their reactivity and behavior.

Notably, the resulting scores from molecular docking studies targeting the entrance proteins of SARS-CoV-2 as well as the observed reliable binding modes have revealed that the newly synthesized compounds exhibited promising binding affinity against the targeted proteins compared to known references. As a result, these compounds demonstrate the potential to act as dual inhibitors of both ACE2 and spike protein that could block SARS-CoV-2 cell entry, thereby preventing the infection process, thus making them promising candidates for further development as a therapeutic agent against the coronavirus and its variants.

Moreover, in silico ADME prediction shows that the synthesized compounds fully obeyed Lipinski's rule, adhered to other essential drug-likeness rules, and displayed good ADMET properties, suggesting their suitability as drug candidates. This opens the door for further in vitro and in vivo investigations of their therapeutic properties.

Overall, the findings of this study may contribute to the ongoing efforts to develop effective treatments against SARS-CoV-2 or the upcoming variants, which could be highly contagious and fast-spreading, and evade immunity from previous infections or vaccines that remain a significant public health concern worldwide.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mohamed Azzouzi: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Zainab El Ouafi: Software, Methodology. Omar Azougagh: Software, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Walid Daoudi: Investigation, Methodology. Hassan Ghazal: Resources. Soufian El Barkany: Resources. Rfaki Abderrazak: Formal analysis. Stéphane Mazières: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Abdelmalik El Aatiaoui: Validation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Adyl Oussaid: Supervision, Validation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to their respective institutions for providing the necessary facility to complete this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.135525.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Pathania S., Narang R.K., Rawal R.K. Role of sulphur-heterocycles in medicinal chemistry: an update. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;180:486–508. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eftekhari-Sis B., Zirak M., Akbari A. Arylglyoxals in synthesis of heterocyclic compounds. Chem. Rev. 2013;113(5):2958–3043. doi: 10.1021/cr300176g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kharb R., Sharma P.C., Yar M.S. Pharmacological significance of triazole scaffold. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2011;26(1):1–21. doi: 10.3109/14756360903524304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deep A., Kaur Bhatia R., Kaur R., Kumar S., Kumar Jain U., Singh H., Batra S., Kaushik D., Kishore Deb P. Imidazo [1, 2-a] pyridine scaffold as prospective therapeutic agents. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017;17(2):238–250. doi: 10.2174/1568026616666160530153233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar A., Kumar M., Maurya S., Khanna R.S. Regioselective synthesis of fused imidazo [1, 2-a] pyrimidines via intramolecular C–N bond formation/6-endo-dig cycloisomerization. J. Org. Chem. 2014;79(15):6905–6912. doi: 10.1021/jo5007762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamal A., Reddy J.S., Ramaiah M.J., Dastagiri D., Bharathi E.V., Prem Sagar M.V., Pushpavalli S.N.C.V.L., Ray P., Pal-Bhadra M. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of imidazopyridine/pyrimidine-chalcone derivatives as potential anticancer agents. Medchemcomm. 2010;1(5):355–360. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gueiffier A., Lhassani M., Elhakmaoui A., Snoeck R., Andrei G., Chavignon O., Teulade J.-.C., Kerbal A., Essassi E.M., Debouzy J.-.C., Witvrouw M., Blache Y., Balzarini J., De Clercq E., Chapat J.-.P. Synthesis of acyclo-c-nucleosides in the imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine and pyrimidine series as antiviral agents. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39(14):2856–2859. doi: 10.1021/jm9507901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Véron J.-.B., Allouchi H., Enguehard-Gueiffier C., Snoeck R., Andrei G., De Clercq E., Gueiffier A. Influence of 6- or 8-substitution on the antiviral activity of 3-arylalkylthiomethylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridine against human cytomegalovirus (CMV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV): part II. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16(21):9536–9545. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aeluri R., Alla M., Polepalli S., Jain N. Synthesis and antiproliferative activity of imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine Mannich bases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;100:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Tel T.H., Al-Qawasmeh R.A. Post Groebke–Blackburn multicomponent protocol: synthesis of new polyfunctional imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine and imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine derivatives as potential antimicrobial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45(12):5848–5855. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rival Y., Grassy G., Taudou A., Ecalle R. Antifungal activity in vitro of some imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1991;26(1):13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laneri S., Sacchia A., Gallitelli M., Arena F., Luraschi E., Abignente E., Filippelli W., Rossi F. Research on heterocyclic compounds — Part XXXIX. 2-Methylimidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine-3-carboxylic derivatives: synthesis and antiinflammatory activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1998;33(3):163–170. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Almirante L., Polo L., Alfonso E.Provinciali, Rugarli P., Gamba A., Olivi A., Murmann W. Derivatives of imidazole. II. Synthesis and reactions of imidazo[1,2-α]pyrimidines and other bi- and tricyclic imidazo derivatives with analgesic, antiinflammatory, antipyretic, and anticonvulsant activity. J. Med. Chem. 1966;9(1):29–33. doi: 10.1021/jm00319a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tully W.R., Gardner C.R., Gillespie R.J., Westwood R. 2-(Oxadiazolyl)- and 2-(thiazolyl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidines as agonists and inverse agonists at benzodiazepine receptors. J. Med. Chem. 1991;34(7):2060–2067. doi: 10.1021/jm00111a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li B., Shen N., Yang Y., Zhang X., Fan X. Synthesis of naphtho[1′,2′:4,5]imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines via Rh(iii)-catalyzed C–H functionalization of 2-arylimidazo[1,2-a]pyridines with cyclic 2-diazo-1,3-diketones featuring with a ring opening and reannulation. Organic Chem. Front. 2020;7(7):919–925. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu B., Guo H., Zhou P., Shi Z.-.L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19(3):141–154. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng M. Outbreak of COVID-19: an emerging global pandemic threat. Biomed. Pharmacotherapy. 2020;129 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.W.H.O. (WHO), WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard 2023. https://covid19.who.int/.

- 19.Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P., Bretzel G., Froeschl G., Wallrauch C., Zimmer T., Thiel V., Janke C., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Drosten C., Vollmar P., Zwirglmaier K., Zange S., Wölfel R., Hoelscher M. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. New England J. Med. 2020;382(10):970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Xia J.a., Zhou X., Xu S., Huang H., Zhang L., Zhou X., Du C., Zhang Y., Song J., Wang S., Chao Y., Yang Z., Xu J., Zhou X., Chen D., Xiong W., Xu L., Zhou F., Jiang J., Bai C., Zheng J., Song Y. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020;180(7):934–943. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pierce M., McManus S., Jessop C., John A., Hotopf M., Ford T., Hatch S., Wessely S., Abel K.M. Says who? The significance of sampling in mental health surveys during COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(7):567–568. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30237-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker S.R., Bloom N., Davis S.J., Kost K., Sammon M., Viratyosin T. The unprecedented stock market reaction to COVID-19. Rev. Asset Pricing Stud. 2020;10(4):742–758. [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Jaddaoui I., Allali M., Raoui S., Sehli S., Habib N., Chaouni B., Al Idrissi N., Benslima N., Maher W., Benrahma H., Hamamouch N., El Bissati K., El Kasmi S., Hamdi S., Bakri Y., Nejjari C., Amzazi S., Ghazal H. A review on current diagnostic techniques for COVID-19. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2021;21(2):141–160. doi: 10.1080/14737159.2021.1886927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forchette L., Sebastian W., Liu T. A comprehensive review of COVID-19 virology, vaccines, variants, and therapeutics. Curr. Med. Sci. 2021;41(6):1037–1051. doi: 10.1007/s11596-021-2395-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conti P., Ronconi G., Caraffa A., Gallenga C., Ross R., Frydas I., Kritas S. Induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1 and IL-6) and lung inflammation by Coronavirus-19 (COVI-19 or SARS-CoV-2): anti-inflammatory strategies. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents. 2020;34(2):327–331. doi: 10.23812/CONTI-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh A., Gupta V. SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics: how far do we stand from a remedy? Pharmacological Rep. 2021;73(3):750–768. doi: 10.1007/s43440-020-00204-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo Y.-.R., Cao Q.-.D., Hong Z.-.S., Tan Y.-.Y., Chen S.-.D., Jin H.-.J., Tan K.-.S., Wang D.-.Y., Yan Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak – an update on the status. Mil. Med. Res. 2020;7(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin J.-.M., Bai P., He W., Wu F., Liu X.-.F., Han D.-.M., Liu S., Yang J.-.K. Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: focus on severity and mortality. Front. Public Health. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clausen C.L., Holm Johannsen T., Skakkebæk N.Erik, Frederiksen H., Ryrsø C.K., Dungu A.M., Hegelund M.H., Faurholt-Jepsen D., Krogh-Madsen R., Lindegaard B., Linneberg A., Kårhus L.L., Juul A., Benfield T. Pituitary–gonadal hormones associated with respiratory failure in men and women hospitalized with COVID-19: an observational cohort study. Endocr. Connect. 2023;12(1) doi: 10.1530/EC-22-0444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ding T., Zhang J., Wang T., Cui P., Chen Z., Jiang J., Zhou S., Dai J., Wang B., Yuan S., Ma W., Ma L., Rong Y., Chang J., Miao X., Ma X., Wang S. Potential influence of menstrual status and sex hormones on female severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: a cross-sectional multicenter study in Wuhan, China. Clinic. Infect. Dis. 2021;72(9):e240–e248. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gebhard C., Regitz-Zagrosek V., Neuhauser H.K., Morgan R., Klein S.L. Impact of sex and gender on COVID-19 outcomes in Europe. Biol. Sex Differ. 2020;11(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00304-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wenham C., Smith J., Morgan R. COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet North Am. Ed. 2020;395(10227):846–848. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30526-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zadeh E.E., Vahabpour R., Beirami A.D., Hajimahdi Z., Zarghi A. Novel 4-Oxo-4, 10-dihydrobenzo [4, 5] imidazo [1, 2-a] pyrimidine-3-carboxylic acid derivatives as HIV-1 integrase inhibitors: synthesis, docking studies, molecular dynamics simulation and biological activities. Med. Chem. Res. 2021;17(9):1060–1071. doi: 10.2174/1573406416666200909104616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pandeya S.N., Sriram D., Nath G., DeClercq E. Synthesis, antibacterial, antifungal and anti-HIV activities of Schiff and Mannich bases derived from isatin derivatives and N-[4-(4′-chlorophenyl)thiazol-2-yl] thiosemicarbazide. European J. Pharmaceutical Sci. 1999;9(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(99)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vliegen I., Paeshuyse J., De Burghgraeve T., Lehman L.S., Paulson M., Shih I.H., Mabery E., Boddeker N., De Clercq E., Reiser H., Oare D., Lee W.A., Zhong W., Bondy S., Pürstinger G., Neyts J. Substituted imidazopyridines as potent inhibitors of HCV replication. J. Hepatol. 2009;50(5):999–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harvey W.T., Carabelli A.M., Jackson B., Gupta R.K., Thomson E.C., Harrison E.M., Ludden C., Reeve R., Rambaut A., Peacock S.J., Robertson D.L., Consortium C.-G.U. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19(7):409–424. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00573-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boopathi S., Poma A.B., Kolandaivel P. Novel 2019 coronavirus structure, mechanism of action, antiviral drug promises and rule out against its treatment. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021;39(9):3409–3418. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1758788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cong Y., Feng Y., Ni H., Zhi F., Miao Y., Fang B., Zhang L., Zhang J.Z.H. Anchor-locker binding mechanism of the coronavirus spike protein to human ACE2: insights from computational analysis. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021;61(7):3529–3542. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gurwitz D. Angiotensin receptor blockers as tentative SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics. Drug Dev. Res. 2020;81(5):537–540. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.kerkour R., Chafai N., Moumeni O., Chafaa S. Novel α-aminophosphonate derivates synthesis, theoretical calculation, Molecular docking, and in silico prediction of potential inhibition of SARS-CoV-2. J. Mol. Struct. 2023;1272 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2022.134196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benbouguerra K., Chafai N., Chafaa S., Touahria Y.I., Tlidjane H. New α-Hydrazinophosphonic acid: synthesis, characterization, DFT study and in silico prediction of its potential inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 main protease. J. Mol. Struct. 2021;1239 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hellal A., Chafaa S., Chafai N., Touafri L. Synthesis, antibacterial screening and DFT studies of series of α-amino-phosphonates derivatives from aminophenols. J. Mol. Struct. 2017;1134:217–225. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Azougagh O., Essayeh S., Achalhi N., El Idrissi A., Amhamdi H., Loutou M., El Ouardi Y., Salhi A., Abou-Salama M., El Barkany S. New benzyltriethylammonium/urea deep eutectic solvent: quantum calculation and application to hyrdoxylethylcellulose modification. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022;276 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friesner R.A., Beachy M.D. Quantum mechanical calculations on biological systems. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1998;8(2):257–262. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee C., Yang W., Parr R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 1988;37(2):785–789. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noureddine O., Issaoui N., Medimagh M., Al-Dossary O., Marouani H. Quantum chemical studies on molecular structure, AIM, ELF, RDG and antiviral activities of hybrid hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19: molecular docking and DFT calculations. J. King Saud University Sci. 2021;33(2) doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2020.101334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Venkateshan M., Muthu M., Suresh J., Kumar R.Ranjith. Azafluorene derivatives as inhibitors of SARS CoV-2 RdRp: synthesis, physicochemical, quantum chemical, modeling and molecular docking analysis. J. Mol. Struct. 2020;1220 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.128741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Topal T., Zorlu Y., Karapınar N. Synthesis, X-ray crystal structure, IR and Raman spectroscopic analysis, quantum chemical computational and molecular docking studies on hydrazone-pyridine compound: as an insight into the inhibitor capacity of main protease of SARS-CoV2. J. Mol. Struct. 2021;1239 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ganga M., Sankaran K.R. Synthesis, spectral characterization, DFT, molecular docking and biological evaluation of some newly synthesized asymmetrical azines of 3,5-dimethoxy-4‑hydroxy benzaldehyde. Chem. Data Collect. 2020;28 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frisch A., Nielson A., Holder A. Vol. 556. Gaussian Inc.; Pittsburgh, PA: 2000. (Gaussview User Manual). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Halim S.A., Ibrahim M.A. Synthesis, spectral analysis, quantum studies, NLO, and thermodynamic properties of the novel 5-(6-hydroxy-4-methoxy-1-benzofuran-5-ylcarbonyl)-6-amino-3-methyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b] pyridine (HMBPP) RSC Adv. 2022;12(21):13135–13153. doi: 10.1039/d2ra01469f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parr R.G., Pearson R.G. Absolute hardness: companion parameter to absolute electronegativity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105(26):7512–7516. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Racine J. gnuplot 4.0: a portable interactive plotting utility. J. Appl. Econ. 2006;21(1):133–141. [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Breemen R.B., Muchiri R.N., Bates T.A., Weinstein J.B., Leier H.C., Farley S., Tafesse F.G. Cannabinoids block cellular entry of SARS-CoV-2 and the emerging variants. J. Nat. Prod. 2022;85(1):176–184. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c00946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30(16):2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.S. Yuan, H.C.S. Chan, Z. Hu, Using PyMOL as a platform for computational drug design, wires computational molecular science 7(2) (2017) e1298.

- 58.D.S.S.D. Biovia, CA, USA, Discovery studio visualizer, 936 (2017).

- 59.Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):42717. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pires D.E.V., Blundell T.L., Ascher D.B. pkCSM: predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58(9):4066–4072. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rival Y., Grassy G., Michel G. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of some imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidine derivatives. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1992;40(5):1170–1176. doi: 10.1248/cpb.40.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mohire P.P., Chandam D.R., Patravale A.A., Choudhari P., Karande V., Ghosh J.S., Deshmukh M.B. An expedient four component synthesis of substituted pyrido-pyrimidine heterocycles in glycerol: proline based low transition temperature mixture and their antioxidant activity with molecular docking studies. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2021;42(1):137–155. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kinen C.O., Rossi L.I., de Rossi R.H. The development of an environmentally benign sulfide oxidation procedure and its assessment by green chemistry metrics. Green Chem. 2009;11(2):223–228. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mohire P.P., Chandam D.R., Patil R.B., Patravale A.A., Ghosh J.S., Deshmukh M.B. Low melting mixture glycerol:proline as an innovative designer solvent for the synthesis of novel chromeno fused thiazolopyrimidinone derivatives: an excellent correlation with green chemistry metrics. J. Mol. Liq. 2019;283:69–80. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang R., Xu X., Ma P., Ma C., Zhai D., Pan Y., Jiang J. High-energy materials based on 1H-tetrazole and furoxan: molecular design and screening. J. Mol. Struct. 2022;1250 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ebenso E.E., Verma C., Olasunkanmi L.O., Akpan E.D., Verma D.K., Lgaz H., Guo L., Kaya S., Quraishi M.A. Molecular modelling of compounds used for corrosion inhibition studies: a review. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021;23(36):19987–20027. doi: 10.1039/d1cp00244a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pramanik S., Roy S., Ghorui T., Ganguly S., Pramanik K. Molecular and electronic structure of nonradical homoleptic pyridyl-azo-oxime complexes of cobalt(iii) and the azo-oxime anion radical congener: an experimental and theoretical investigation. Dalton Trans. 2014;43(14):5317–5334. doi: 10.1039/c3dt53460j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kosar B., Albayrak C. Spectroscopic investigations and quantum chemical computational study of (E)-4-methoxy-2-[(p-tolylimino)methyl]phenol. Spectrochim. Acta Part A. 2011;78(1):160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.He P., Zhang J.-.G., Wu L., Wu J.-.T., Zhang T.-.L. Computational design and screening of promising energetic materials: novel azobis(tetrazoles) with ten catenated nitrogen atoms chain. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2017;30(10):e3674. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eno E.A., Mbonu J.I., Louis H., Patrick-Inezi F.S., Gber T.E., Unimuke T.O., Okon E.E.D., Benjamin I., Offiong O.E. Antimicrobial activities of 1-phenyl-3-methyl-4-trichloroacetyl-pyrazolone: experimental, DFT studies, and molecular docking investigation. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2022;99(7) [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ebenso E.E., Arslan T., Kandemirli F., Caner N., Love I. Quantum chemical studies of some rhodanine azosulpha drugs as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acidic medium. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2010;110(5):1003–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oyeneyin O.E., Ojo N.D., Ipinloju N., James A.C., Agbaffa E.B. Investigation of corrosion inhibition potentials of some aminopyridine schiff bases using density functional theory and monte carlo simulation. Chem. Africa. 2022;5(2):319–332. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Owen A.E., Louis H., Agwamba E.C., Udoikono A.D., Manicum A.-L.E. Antihypotensive potency of p-synephrine: spectral analysis, molecular properties and molecular docking investigation. J. Mol. Struct. 2023;1273 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abraham C.S., Prasana J.C., Muthu S. Quantum mechanical, spectroscopic and docking studies of 2-amino-3-bromo-5-nitropyridine by density functional method. Spectrochim. Acta Part A. 2017;181:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2017.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Noureddine O., Gatfaoui S., Brandan S.A., Sagaama A., Marouani H., Issaoui N. Experimental and DFT studies on the molecular structure, spectroscopic properties, and molecular docking of 4-phenylpiperazine-1-ium dihydrogen phosphate. J. Mol. Struct. 2020;1207 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cao J., Zhao M., Xiao T., Xu J., Chen J., Xu W., Ma C., Ma P. Regulation of external electric field on the high-energy polynitrogen compound 1,5-diaminotetrazole-4N-oxide. J. Mol. Model. 2022;29(1):28. doi: 10.1007/s00894-022-05423-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rathi P.C., Ludlow R.F., Verdonk M.L. Practical high-quality electrostatic potential surfaces for drug discovery using a graph-convolutional deep neural network. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63(16):8778–8790. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang L., Qi Z.-.D., Ye Y.-.L., Li X.-.H., Chen J.-.H., Sun W.-.M. DFT study on the adsorption of 5-fluorouracil on B40, B39M, and M@B40 (M = Mg, Al, Si, Mn, Cu, Zn) RSC Adv. 2021;11(62):39508–39517. doi: 10.1039/d1ra08308b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Abdel Halim S., Hassaneen H.M.E. Experimental and theoretical study on the regioselective bis- or polyalkylation of 6-amino-2-mercapto-3H-pyrimidin-4-one using zeolite nano-gold catalyst and a quantum hybrid computational method. RSC Adv. 2022;12(55):35794–35808. doi: 10.1039/d2ra06572j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bader R.F.W. Atoms in molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 1985;18(1):9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Saleh G., Gatti C., LoPresti L., Contreras-García J. Revealing non-covalent interactions in molecular crystals through their experimental electron densities. Chemistry – A European J. 2012;18(48):15523–15536. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Contreras-García J., Johnson E.R., Keinan S., Chaudret R., Piquemal J.P., Beratan D.N., Yang W. NCIPLOT: a program for plotting non-covalent interaction regions. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7(3):625–632. doi: 10.1021/ct100641a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lipinski C.A., Lombardo F., Dominy B.W., Feeney P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012;64:4–17. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ghose A.K., Viswanadhan V.N., Wendoloski J.J. A knowledge-based approach in designing combinatorial or medicinal chemistry libraries for drug discovery. 1. A qualitative and quantitative characterization of known drug databases. J. Comb. Chem. 1999;1(1):55–68. doi: 10.1021/cc9800071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Veber D.F., Johnson S.R., Cheng H.-.Y., Smith B.R., Ward K.W., Kopple K.D. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45(12):2615–2623. doi: 10.1021/jm020017n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Egan W.J., Merz K.M., Baldwin J.J. Prediction of drug absorption using multivariate statistics. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43(21):3867–3877. doi: 10.1021/jm000292e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Muegge I., Heald S.L., Brittelli D. Simple selection criteria for drug-like chemical matter. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44(12):1841–1846. doi: 10.1021/jm015507e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morcoss M.M., El Shimaa M., Ibrahem R.A., Abdel-Rahman H.M., Abdel-Aziz M., Abou El-Ella D.A. Design, synthesis, mechanistic studies and in silico ADME predictions of benzimidazole derivatives as novel antifungal agents. Bioorg. Chem. 2020;101 doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cheng F., Li W., Zhou Y., Shen J., Wu Z., Liu G., Lee P.W., Tang Y. admetSAR: a comprehensive source and free tool for assessment of chemical ADMET properties. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012;52(11):3099–3105. doi: 10.1021/ci300367a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kalantzi L., Goumas K., Kalioras V., Abrahamsson B., Dressman J.B., Reppas C. Characterization of the human upper gastrointestinal contents under conditions simulating bioavailability/bioequivalence studies. Pharm. Res. 2006;23(1):165–176. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-8476-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Awortwe C., Fasinu P., Rosenkranz B. Application of Caco-2 cell line in herb-drug interaction studies: current approaches and challenges. JPPS. 2014;17(1):1. doi: 10.18433/j30k63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mishra S.S., Kumar N., Sirvi G., Sharma C.S., Singh H.P., Pandiya H. Computational prediction of pharmacokinetic, bioactivity and toxicity parameters of some selected anti-arrhythmic agents. Pharm. Chem. J. 2017;4:143–146. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rodrigues-Junior V.S., Villela A.D., Abbadi B.L., Sperotto N.D., Pissinate K., Picada J.N., da Silva J.B., Bizarro C.V., Machado P., Basso L.A. Nonclinical evaluation of IQG-607, an anti-tuberculosis candidate with potential use in combination drug therapy. RTP. 2020;111 doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2019.104553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Garrido A., Lepailleur A., Mignani S.M., Dallemagne P., Rochais C. hERG toxicity assessment: useful guidelines for drug design. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;195 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Han Y., Zhang J., Hu C.Q., Zhang X., Ma B., Zhang P. In silico ADME and toxicity prediction of ceftazidime and its impurities. Front. Pharmacol. 2019;10:434. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.