Abstract

An adequate bowel preparation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a prerequisite for successful colonoscopy for screening, diagnosis, and surveillance. Several bowel preparation formulations are available, both high- and low-volume based on polyethylene glycol. Generally, low-volume formulations are also based on several compounds such as magnesium citrate preparations with sodium picosulphate, oral sulphate solution, and oral sodium phosphate-based solutions. Targeted studies on the quality of bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy in the IBD population are still required, with current evidence from existing studies being inconclusive. New frontiers are also moving towards the use of alternatives to anterograde ones, using preparations based on retrograde colonic lavage.

Keywords: Bowel preparation, Colonoscopy, Inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, Ulcerative colitis, Artificial intelligence

Core Tip: Obtaining adequate bowel preparation is challenging when treating a patient with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) undergoing colonoscopy. Colonoscopy has multidimensional value ranging from diagnosis to disease surveillance and cancer screening. Although numerous data are available on bowel preparations in the general population, it is still unclear which preparation is the best for both efficacy and safety in patients with IBD. In addition, the factors that increase the risk of suboptimal preparation in IBD patients remain unclear.

INTRODUCTION

Adequate bowel preparation is crucial for successful colonoscopy in diagnostic, therapeutic, and screening indications; however, it remains one of the main challenges in patients undergoing colonoscopy[1,2]. Thus, several requirements were identified for managing this issue, including improving the palatability and tolerability of bowel preparation products and adopting a tailored, patient focused approach by taking into account the patient's choice of product[1]. Management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), requires regular endoscopic surveillance. In patients with IBD, endoscopic procedures are indicated for initial diagnosis, monitoring of disease activity, evaluation of therapeutic response, and cancer screening[3]. The latter indication is significant as patients with IBD are at an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer[4]. In addition, a proportion of patients with IBD undergo surgical intervention and therefore require postoperative endoscopic re-evaluation to identify any postsurgical recurrence, especially in CD[5].

Emerging evidence has emphasised “treat-to-target” approaches in the management of IBD by defining specific treatment goals and punctuating the timing of evaluation. Assessment of these uses standardised endoscopic scores, the calculation of which requires adequate bowel preparation in all regions of the colon and last ileum that can be explored by colonoscopy and ileocolonoscopy[6,7]. However, especially in IBD patients, there is a need to weigh up the safety of intestinal preparations, especially under severe disease activity conditions[8]. Although rare, significant adverse events associated with bowel preparation, such as mucosal inflammation[9], intestinal perforations[10], and ischaemic colitis[11], have been reported.

The purpose of the present review is to provide an overview of the current available evidence on bowel preparation formulations, specifically evaluated in IBD, to determine the factors of successful and unsuccessful bowel preparation in patients with IBD, and to provide clues on the appropriate choice of formulation for IBD patients.

TYPE OF BOWEL PREPARATIONS STUDIED IN IBD

Several bowel preparations are available for patients undergoing colonoscopies. They can be categorized into high-volume (volume of at least 3 L), isosmotic, polyethylene glycol (PEG) formulations, and low-volume (volume less than 3 L, but with the addition of osmotically active adjuvants such as ascorbic-acid, citrate, and bisacodyl) PEG[12]. There are also osmotically active, non-PEG, low-volume solutions. Examples include magnesium citrate preparations or other preparations based on sodium picosulphate, oral sulphate, and oral sodium phosphate[12]. However, they have a high potential risk of adverse events due to their osmotic properties.

There are currently no studies that provide a definitive and detailed overview of the application of various bowel preparations available to patients with IBD. Table 1 summarises the bowel preparation regimens studied specifically for IBD patients. Case reports of patients with IBD and the relevant adverse events associated with bowel preparation are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Anterograde and retrograde bowel preparation regimens studied in patients with inflammatory bowel disease

|

Ref.

|

Year

|

Design

|

n

|

IBD

|

Bowel preparation

|

Split dosing considered

|

Low fiber diet considered

|

Main result (success), %

|

Post-colonoscopy IBD flare-up rate, % (days after colonoscopy)

|

Severe AEs

|

| Gould et al[13] | 1982 | CT | 23 | UC: 23 | Castor oil 30 mL | - | YES | 82.6 | 26 (14-21 d) | NO |

| Gould et al[13] | 1982 | CT | 23 | UC: 23 | Sennosides 75 mg | - | YES | 86.9 | 48 (14-21 d) | NO |

| Lazzaroni et al[15] | 1993 | CT | 48 | UC: 26; CD: 23 | 4 L PEG-ELS plus placebo | YES | - | 96 | - | NO |

| Lazzaroni et al[15] | 1993 | CT | 57 | UC: 35; CD: 21 | 4 L PEG-ELS plus simethicone | YES | - | 96 | - | NO |

| Manes et al[53] | 2015 | CT | 106 | UC: 106 | 2 L PEG plus bisacodyl | YES | YES | 83 | - | NO |

| Manes et al[53] | 2015 | CT | 105 | UC: 105 | 4 L PEG-ELS | YES | YES | 77.1 | - | NO |

| Kim et al[22] | 2017 | CT | 53 | UC: 53 | 4 L PEG-ELS | YES | YES | 96.2 | 5.7 (7 d); 1.9 (28 d) | NO |

| Kim et al[22] | 2017 | CT | 56 | UC: 56 | 2 L PEG plus ascorbate | YES | YES | 92.9 | 3.6 (7 d); 1.8 (28 d) | NO |

| Briot et al[31] | 2019 | nCT Prospective | UC: 21; CD: 57; Unspecified IBD: 2 | Picosulphate-based regimen | YES | YES | 78.4 | 0 | NO | |

| Bezzio et al[39] | 2020 | nCTProspective | 189 | UC: 63; CD: 63 | 2 L PEG-ELS plus simethicone | YES | - | UC: 89.8; CD: 86.2 | - | NO |

| Maida et al[25] | 2021 | nCT Retrospective | 185 | UC: 95; CD: 90 | 1 L PEG plus ascorbate solution | YES | YES | 92.9 | - | NO |

| Mohsen et al[30] | 2021 | CT | 61 | - | 2 L Sodium; picosulphate, magnesium citrate PEG | YES | YES | 89.5 | - | NO |

| Mohsen et al[30] | 2021 | CT | 64 | - | 2 L PEG plus ascorbate solution | YES | YES | - | NO | |

| Neri et al[29] | 2021 | nCT Prospective | 103 | UC: 47; CD: 56 | 1 L PEG-ELS | YES | YES | 85.4 | - | NO |

| Kim et al[32] | 2022 | nCT Prospective | 52 | UC: 35; CD: 17 | 2 L PEG plus ascorbate | YES | YES | 98.1 | 0 (7 and 28 d) | NO |

| Kim et al[32] | 2022 | nCT Prospective | 55 | UC: 37; CD: 18 | Novel oral sulphate tablets | YES | YES | 98.1 | 3,63 (7 and 28 d) | NO |

| Gajera et al[51] | 2022 | nCT Retrospective | 318 | UC: 182; CD: 104; Unspecified IBD: 28 | Colonic lavage | Not applicable | YES | 97 | - | NO |

IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; PEG: Polyethylene glycol; ELS: Electrolyte lavage solution; UC: Ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease; CT: Clinical trial; nCT: Non-clinical trial.

Table 2.

Case reports on patients with known inflammatory bowel disease and relevant adverse events related to bowel preparation

|

Ref.

|

Bowel preparation

|

Age

|

IBD

|

Gender

|

AE

|

Comorbidity

|

IBD therapy

|

Outcome

|

| Loraine et al[34] | Sodium picosulphate/magnesium oxide/citric acid | 73 | CD | F | Shock | Severe COPD, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiomyopathy, diverticular disease | Azathioprine | Dead |

| Gonlusen et al[35] | Sodium picosulphate | 56 | CD | F | Acute renal failure | GERD, healed gastric ulcer, endometriosis, mitral valve prolapse, migraine | None | Favourable |

IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; CD: Crohn’s disease; F: Female; AE: Adverse event; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Bowel preparation studied in IBD: Origins

An early trial in 1982 focused on evaluating bowel preparation in patients with UC who underwent colonoscopy for dysplasia screening[13]. The study compared two bowel preparation products, castor oil (30 mL) and senna tablets (75 mg sennosides). However, the authors highlighted post-colonoscopy complaints (particularly complaints that were more common with senna tablets) and many UC flare-ups in several cases requiring steroid treatment. In this study, they targeted patients with UC with inactive or presumably mild disease activity. The efficacy rate shown with both preparations exceeded 80%. In any case, to date, such preparations are insupportable and fall into disuse, especially given the abundant availability of new generation products with better safety margins.

High- and low-volume plus adjuvant preparations of polyethylene glycol in patients with IBD

PEG-based preparations were first introduced in 1980 by Davis et al[14] as an alternative to traditional laxatives. Several studies have examined high-volume PEG preparations in patients with IBD. In general, these formulations have been studied alone or in comparison to a control group of other solutions such as low-volume solutions.

An early Italian study[15] evaluated the efficacy of simethicone in addition to a 4 L PEG Electrolyte Lavage Solution (ELS). A high efficacy rate of 96% was shown in the group taking only 4 L PEG-ELS (considering at least acceptable preparation). In contrast, preparation was adequate and excellent in 50% and 27% of IBD participants, respectively. The authors defined the preparation as excellent in the absence of formed stools and the presence of low fluid content. The preparation was defined as adequate in the absence of formed stools and the moderate presence of clear fluid. Regarding the safety profile, the preparation showed poor tolerability in only 14% of participants with no serious adverse events and the main complaint was abdominal bloating.

However, two subsequent studies compared high-volume and low-volume PEG solutions with bisacodyl and ascorbic acid adjuvants.

Bisacodyl is a diphenylmethane compound. It has an extrinsic laxative action owing to its dual prokinetic and secretion properties after conversion to an intestinally active metabolite. It has shown comparable properties in some intestinal motility parameters to other drugs such as prucalopride, linaclotide, and tegaserod[16].

In a noninferiority study with 211 participants, Kastenberg et al[17] compared a high-volume 4 L PEG-ELS solution with a low-volume solution (2 L PEG) with bisacodyl adjuvant at 5 mg, and concluded a noninferiority of the latter over the former. They focused exclusively on patients with UC. Patients had a free choice of a split or non-split regimen, but nonetheless were instructed to eat a low fibre diet for the 3 d prior to preparation. Bisacodyl was administered by patients in the afternoon of the day before the procedure, and only after the procedure was initiated. Colon cleansing was assessed using the Ottawa scale[17]. The efficacy rate was higher in the low-volume group (83%), compared with 77.1% in the high-volume group, but the difference was not significant. In addition, the presence of bubbles was significantly worse in the low-volume group. Disease activity and the type of administration (split or not) did not influence patient compliance. In terms of safety, severe adverse reactions were not observed in both solutions. The low-volume PEG preparation with bisacodyl in this study, showed greater potential in avoiding gastrointestinal disorders associated with bowel preparation, including bloating, cramping, anal irritation, nausea, and vomiting.

In any case, the use of bisacodyl at high dosages > 5 mg should be avoided[18]. Cases of ischaemic colitis after bisacodyl use have been reported. Two cases were reported after using 15 mg bisacodyl in two women over 50 years of age with ischaemic colitis. In both cases, the patients were discharged without adverse outcomes; however, in one of the two cases, haemodynamic deterioration was experienced[19]. They were not IBD patients; however, in the latter patients, bisacodyl dosing must be weighed carefully. Certainly, such preparations should be evaluated with extreme caution in elderly patients with cardiovascular and ischaemic colitis risk factors[20] and even more so in patients with coexisting IBD.

Neurointestinal reactions are further rare but serious adverse reactions. In some studies, the use of bisacodyl as a laxative induced changes in colonic redundancy and colonic dilatation with loss of haustral markings. This is likely to have been caused by neuronal or colonic muscle damage[21]. In addition, in vitro evidence in rat bladder epithelium, suggests that bisacodyl has the potential to induce proliferative epithelial injury[21]. However, such evidence is still experimental and does not definitively impose a contraindication for this product. Moreover, the contraindication for bisacodyl in patients with advanced congestive heart failure should also be considered[18].

A subsequent study by Kim et al[22] investigated the low-volume solution adjuvant ascorbic acid, and compared this with classic high-volume 4 L PEG-ELS. As in the previous study, the authors exclusively targeted 109 patients with inactive UC. In addition, in this study, patients were given a free choice between a split and non-split regimen, and were advised to eat a fibre-free diet for 2 d before the endoscopic examination. Bowel preparation quality was assessed with the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBSP)[23] and a score of equal to or greater than 6 defined a successful preparation. The authors also assessed possible disease recurrence 4 wk after the endoscopic procedure using the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index[24], with a cut-off greater than 4 defined as recurrence. In both groups, the split regimen was the most widely used, and more than 90% of patients in both groups achieved an effective preparation. The safety profile was slightly worse in the 4 L PEG group, but not significantly different from that of the low-volume preparation. However, patients treated with 4 L PEG experienced a significantly higher rate of nausea. There was no difference in disease recurrence at 1 mo, which was more, but not significantly greater than that in the low-volume group with ascorbate (25% vs 22.6%, respectively).

Moreover, in the context of ascorbate-based preparations, Maida et al[25] evaluated a preparation with 1 L of PEG in 185 patients with IBD, compared with 226 non-IBD controls. The study concluded a higher clearance rate (assessed by the BBSP) than in non-IBD controls (92.9% vs 85.4%), and a similar safety profile between IBD and non-IBD. No correlation was found between disease activity and incidence of adverse events. The rate of non-severe adverse events was 22.2% in IBD patients compared with 21.2% in controls, and there were no severe adverse events in the study.

Patients with phenylketonuria or glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency should not undergo this type of preparation due to the presence of ascorbate[26]. Some case reports of serious adverse events have also been described with ascorbic acid. For example, an > 70-year-old hypertensive diabetic woman experienced ischaemic colitis with 200 g of 3350 PEG in 1 L and 21 g of ascorbic acid solution[27]. An 82-year-old woman with atrial fibrillation and mild chronic renal failure received a 1 L PEG preparation with ascorbate and experienced non-occlusive mesenteric ischaemic colitis[28]. Both were elderly, non-IBD patients, with cardiovascular risk factors. Therefore, similar to bisacodyl, such preparations should be weighed carefully in elderly patients with IBD and cardiovascular risk factors. In addition, attention should be paid to patients with advanced heart failure, unstable angina, and creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min. In these patients, adequate hydration should be considered when such a formulation is used[18].

Finally, an attempt with very low-volume PEG-based preparations (1 L PEG) was made by Neri et al[29]. In a cohort of 103 IBD patients, with good distribution between CD and UC, Neri et al[29] showed an adequate preparation rate of 85.4% (assessed by BBSP), with an impact of disease activity on preparation rate. This evidence, coupled with a good safety profile, makes this preparation a good choice for patients with a very low tolerance for high-volume preparations.

Moreover, a final study by Mohsen et al[30] evaluated a comparative single-blinded randomised trial for both preparation type and population (IBD vs non-IBD patients). The authors compared a preparation based on sodium picosulphate/magnesium citrate in combination with PEG and a low-volume preparation of PEG with ascorbic acid. The two preparations did not differ in terms of efficacy (assessed by the Ottawa scale) or safety. Although, in the group of IBD patients on the low-volume preparation of PEG with ascorbic acid, the incidence of abdominal pain increased. Overall, only 10.5% of the patients had inadequate preparation.

What are the alternatives to polyethylene glycol-based preparations in focused studies in patients with IBD?

Alternatives to PEG-based preparations include those based on magnesium citrate plus picosulphate and oral sulphate solutions, a compound of magnesium sulphate, sodium sulphate, and potassium sulphate. However, few studies have evaluated these preparations for IBD treatment.

A 2019 French multicentre study examined several low-volume solutions based on sodium picosulphate, sodium phosphate, and trisulphate (sodium, magnesium, and potassium sulphate)[31]. All three of these non-PEG regimens had been administered in more than 50% of the sample in a split regimen, with a previous low fibre diet lasting between one and more than 3 d, depending on the regimen. The efficacy rate in the preparation with sodium picosulphate reached 78.4%, comparable with 76.7% of the 2 L PEG examined in the same study. Both formulations were significantly more effective than the control 4 L PEG group. In addition, patient tolerance was better in the picosulphate group than in the 2 L and 4 L PEG groups. The safety profile of sodium picosulphate was not extremely harmful because there was one case of fever and another of vomiting in CD patients (however, the sample receiving this formulation consisted of only approximately 80 patients). Oral sulphate tablets were evaluated in the study by Kim et al[32], however, only in 110 patients with inactive IBD in non-inferiority comparison with split regimens with a 2 L PEG preparation with ascorbic acid. The study showed a greater tolerance for the oral sulphate-based preparation, so much so that more than 90% of the patients taking it stated that they would reuse it for subsequent colonoscopy.

Regarding safety, although there were no severe events, a small percentage of patients (only two) on oral sulphate showed disease flare-ups after colonoscopy. Furthermore, caecal intubation was achieved more quickly in the PEG-based preparation (100%) than in the sulphate preparation (92.8%). Finally, the preparation with sulphate achieved a lower and, therefore, better score for bubble presence. There is still little evidence to justify the use of such alternative preparations to PEG-based preparations in patients with IBD, so much so that the recommendations of endoscopic reference societies tend to recommend PEG-based solutions in patients with IBD[18].

In fact, previous evidence has shown that in settings other than IBD, solutions based on sodium phosphate or sodium picosulphate for intestinal preparation had a 10-fold increased risk of developing intestinal mucositis compared with preparations with PEG[33].

Cases of post-preparation shock with picosulphate-based solutions have also been described[34] as well as of acute renal failure[35]. Unlike PEG-based solutions, these solutions are hyperosmolar and challenging to handle and contraindicated in patients with heart failure, rhabdomyolysis, hypermagnesemia, gastrointestinal ulcerative lesions, and renal failure[18].

Role of simethicone as an additional component in bowel preparation

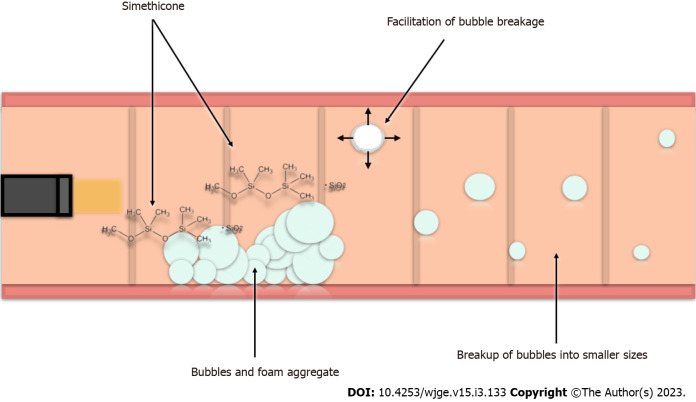

Simethicone is a compound of dimethicone and 4%-7% silicon dioxide. This surfactant can reduce the surface tension of bubbles in the intestinal lumen by removing them. This improves clarity of endoscopic examination and reduces abdominal tension (Figure 1)[36].

Figure 1.

Functioning of simethicone at the level of the intestinal mucosa. Simethicone is a surfactant causing a reduction in the surface tension of intestinal bubbles. This reduction results in the aggregate of bubbles adhering to the colic mucosa being weaker with the facilitation of bubble reduction. As a result, larger bubbles are divided into smaller bubbles that have a greater ease of intestinal transit. The silicon dioxide component of dimethicone has an additional role, with an extensive molecular surface area that can promote bubble rupture. The breakdown of foam and bubbles and formed gas can be either absorbed by the intestinal wall or eliminated by intestinal transit. This likely explains the ameliorative effect on patients' symptoms.

Few studies have investigated the role of simethicone in intestinal preparations, specifically for patients with IBD. Metanalytic evidence has suggested its potential to improve mucosal cleanliness and visibility, providing evidence to increase the detection rate of adenomas and polyps[37,38]. Therefore, Lazzaroni et al[15] began experimenting in a randomised controlled trial with high-volume 4 L PEG-ELS in IBD, comparing with a double-arm design by adding 120 mg of simethicone.

In the study, the mean age of the participants was under 40 years for both arms. The cohort mainly consisted of UC patients. Regarding efficacy rates, bowel preparation was at least acceptable in 96% of cases in both arms. Although efficacy was not found to be a significant distinguishing element between the arms with or without simethicone, it was interesting to note a significant ameliorative effect on the presence of bubbles. Bubbles were either not detected or minimally impacted the examination in 98% of the sample with simethicone vs 85% of patients taking 4 L PEG alone. The tolerability of patient preparation increased in favour of the simethicone-based preparation. Generally, in this study, the addition or non-addition of simethicone did not dramatically affect the differences in safety. These were mainly comparable in terms of nausea, cramping pain, and abdominal bloating, except for sleep disturbances and general malaise, which were drastically lower in patients in the simethicone group (19% vs 44%). Bezzio et al[39] also showed good efficacy and tolerability of a 2 L PEG-ELS solution with added simethicone in 126 patients with IBD.

Further evidence on simethicone in patients with IBD, was provided by studies in a different setting, namely, studies of patients undergoing small-bowel capsule endoscopy[40-42]. One study observed that adding 80 mg of simethicone to a 2 L PEG preparation improved visualisation of the intestinal mucosa more in the proximal rather than in the distal tract, but only in non-CD patients. This effect was likely due to altered motility in CD patients[42]. In addition, in the paediatric population, adding simethicone to the PEG preparation appears to give good results in small-bowel capsule endoscopy; however, good visualisation of the terminal ileum remains challenging[41].

In any case, it is noteworthy that the most recent European guidelines recommend adding simethicone to intestinal preparations, cautiously leaning towards improved cleanliness and tolerability, despite a strong need for evidence to reaffirm this recommendation[18].

A study which was not solely conducted in the IBD population, analysed the optimal timing of simethicone administration in bowel preparation. The study suggested that optimal simethicone administration in the PEG-based preparation was in the evening of the day before colonoscopy. Moreover, the ameliorative effect is primarily at the expense of caecal intubation and bubble improvement[43]. This evaluation was further conducted in another study, combining a PEG preparation with ascorbic acid. Again, patients who took simethicone in the evening of the day before colonoscopy, showed fewer bubbles and improved detection of diminutive adenomas less than or equal to 5 mm[44].

Although not directly analysed in patients with IBD, improvement in the ease of caecal intubation[43] should be considered. Patients with ileal CD, both at the first diagnosis and at follow-up, should be carefully studied in the small intestinal tract. One of the most widely used scores is the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn's Disease[45] uses a thorough assessment of the ileum to identify the presence of ulcerative lesions and/or stenosis. This need is also reaffirmed by another endoscopic score, the Crohn's Disease Index of Severity, most commonly used in patients with CD[46].

The use of intraprocedural simethicone requires several technical considerations. A spectroscopic study of residual fluid samples detected with borescopes in the colonoscope channel found residual simethicone[47]. This study indicated that as simethicone is an inert and hydrophobic compound, it can reduce the effectiveness of endoscope reprocessing. In addition, simethicone is often included in solutions containing sugars which can potentially increase intra-endoscopic microbial growth[48]. Moreover, several dimethicone crystals have been detected in the waterjet channel of a damaged endoscope[49]. Therefore, European guidelines have warned about using simethicone at the lowest effective dose[50], exclusively in the biopsy channel and not in the auxiliary water channel[18].

Role of high-volume colonic lavage as a bowel preparation strategy: A retrograde strategy

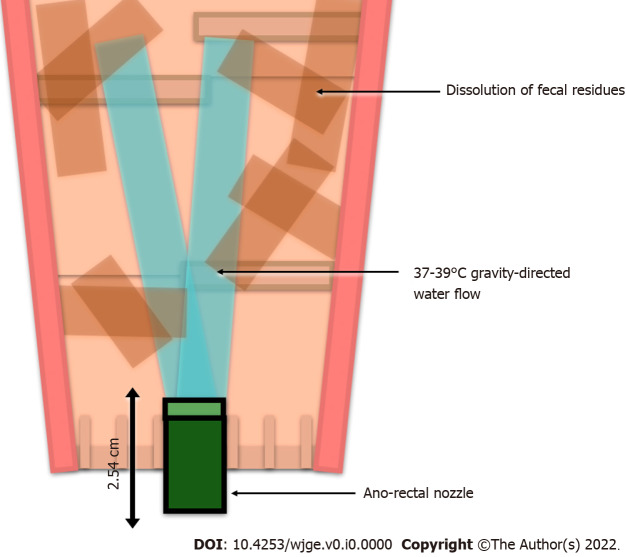

In addition to conventional oral bowel preparations, a promising method of retrograde bowel preparation (already evaluated in non-IBD patients), high-volume water irrigation with colonic lavage, has recently been explored for IBD. This is undoubtedly a preparation modality that overcomes the obstacles and predictors of poor bowel preparation observed for oral bowel preparation. Moreover, it is likely to be more “palatable” to patients who experience problems with oral bowel preparation. However, it can be practiced only in a hospital setting, and after prescription by experienced practitioners. In a recent study, Gajera et al[51] examined this modality (Figure 2) in a retrospective study of more than 300 patients with IBD. The efficacy of bowel preparation was above 90% (except in patients with severe hemorrhoidal disease, in whom it was just under 90%).

Figure 2.

Colonic lavage process. A nozzle is inserted approximately 2.54 cm into the rectum of the patient on a disinfected stand. According to the gravity gradient, a direct flow of water is dispensed from the nozzle at the rigidly controlled temperature of 37-39 °C, with immediate termination of the procedure if this temperature is exceeded. The water flow makes the stool soft, facilitating its dissolution and elimination. The procedure is generally complete within an hour, and the patient can subsequently undergo an endoscopic examination.

Interestingly, a high efficacy rate of 94% was recorded, even for patients with previous gastrointestinal surgery. No severe reactions were observed; the most frequent mild reaction was abdominal pain in approximately 15% of patients. This study was not restricted to a specific IBD and had a good distribution of UC and CD. In this study, IBD patients were required to take bisacodyl (10 mg) the day before colonic lavage. In other non-IBD cases, this was magnesium hydroxide, 1-5 d before.

Comparisons between preparations: What evidence in IBD?

There is still a need for numerous studies on the preparations already available in singles for patients with IBD, especially in the different IBD subgroups with increased severity, such as patients with perianal disease and CD with stenosing phenotype. However, there are even fewer available data of head-to-head comparisons among different regimens.

A meta-analysis by Restellini et al[52] was designed specifically for patients with IBD with adequate bowel preparation as the primary outcome. The study included four previously described studies by Gould et al[13], Lazzaroni et al, Manes et al[53], and Kim et al[22].

The study by Gould et al[13] was excluded owing to a lack of clinical applicability of castor oil or senna. Furthermore, the study by Lazzaroni et al[15] was excluded owing to a lack of robust data on the efficacy of preparation with the addition of simethicone. The remaining two studies compared high- and low-volume PEG-based solutions. Examining these two analytical methods, the authors concluded that there were no relevant differences in preparation quality. Shifting the perspective onto the patient’s tolerability and willingness on the choice of regimen for subsequent colonoscopy, the winning regimens were the addition of simethicone to the 4 L PEG preparation, and the 2 L PEG preparation with bisacodyl or ascorbate compared with high volumes. Meta-analyses comparing PEG-based and non-PEG preparations are still needed. Even fewer comparative data exist between oral and retrograde rectal anterograde IBD preparations. An additional study, particularly relevant to colorectal cancer prevention in IBD, advised IBD patients undergoing chromoendoscopy to follow a clear fluid diet the day before colonoscopy[54].

Predictors of IBD patients' poor bowel preparation?

The extreme phenotypic variability of patients with IBD and the different regimens available for bowel preparation pose a problem for stratifying bowel preparation, identifying which patients are most at risk of poor bowel preparation, and with which preparations.

Several predictors of poor bowel preparation have been identified in PEG-based and UC-based studies, including male sex, non-split regimen, poor patient compliance (less than 100% intake), and moderate to severe discomfort during preparation[53]. The split regimen was a predictor of good bowel cleansing success in the study by Maida et al[25] with a 1 L PEG regimen with ascorbate. In another study that included both PEG-based and non-PEG regimens, PEG 2 L or 4 L regimens were associated with greater efficacy. Having a CD or colonoscopy in private vs public centres has also contributed to this[31]. Other evidence indicates that patients with active CD, experience more abdominal pain during bowel preparation, and patients with worse anxiety experience more symptoms during bowel preparation[55].

In contrast, a recent study by Kumar et al[56] highlighted an interesting finding relating bowel preparation to disease activity and biological therapy. Moderate-to-severe disease activity and biological therapy were predictors of suboptimal bowel preparation. Additional predictors of poor preparation identified in the study were, a non-split regimen, and patient age of over 65 years.

One Digestive Disease Week 2022 abstract presented a retrospective study of factors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy related to underlying IBD in 309 patients. The authors described how the presence of diabetes mellitus and antidepressant use were independent general risk factors in this setting. Indeed, it is well known that diabetes mellitus is a non-negligible comorbidity in IBD patients, increasing the risk of hospitalisations and infections, while not increasing the general risk of IBD complications or mortality[57]. In patients with UC, a history of inadequate bowel preparation was an independent risk factor[58].

One study aimed to investigate the experiences of IBD patients who resorted to repeat colonoscopy through telephone interviews. Despite the small sample size of approximately 33 patients, it emerged that patients felt that repeated colonoscopy was a guarantee of their health, and an ongoing reminder of the chronic and incurable nature of IBD[59]. This underscores how beyond looking for predictors and patient compliance, healthcare providers should strive to assist patients who require continuity of care. This is also in view of the fact that, as demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with IBD are exposed to a higher rate of anxiety and depression than the general population[60], even in disease remission[61]. Moreover, IBD patients are exposed to a non-negligible rate of treatment nonadherence[62,63].

Patients with active IBD: What factors to consider?

Bowel preparations can result in mucosal damage, with some studies having associated cases of toxic megacolon[64-67]. Therefore, caution becomes of utmost importance in patients with active IBD. PEG-based or sulphate-based solutions can induce colic mucosal damage by inducing metabolic or chemical damage[22]. Such histological damage results are also seen with sodium picosulphate[68]. As stated earlier, the risk of mucosal inflammation with PEG solutions is around ten times lower than that with those based on picosulphate or sulphate. Furthermore, picosulphate solutions can cause ulcerative lesions at the esophagogastric level[69,70]. In light of these facts, it is inevitable that for patients with active IBD, the only advisable solutions based on the available evidence, are PEG-based solutions[18,71]. Clearly, within active UC, a distinction must be made between moderate to severe and severe acute UC. Severe acute UC generally includes several diagnostic criteria (the presence of more than six bloody evacuations per day and at least one of the following: Body temperature greater than 37.8 °C, heart rate greater than 90 bpm, haemoglobin less than 105 g/L, and C-reactive protein greater than 30 mg/L. Under these conditions, the risk of impending megacolon, toxic megacolon, and colectomy is very high. Therefore, in addition to the initiation of treatment, it is appropriate to screen for confounding factors of disease activity. First, a faecal culture screening for Clostridium difficile should be performed. However, an evaluation of rectal biopsy for cytomegalovirus should also be performed. For cytomegalovirus evaluation, a complete colonoscopy is not recommended due to the high risk of bowel perforation and a simple sigmoidoscopy is appropriate[72]. Therefore, the problem of choosing the appropriate bowel preparation arises. In such cases, a simple phosphate enema generally suffices, as regular oral bowel preparation may increase the risk of colic dilatation[71].

Prospects: Role of artificial intelligence

More recently, artificial intelligence (AI) applications are emerging for use in digestive endoscopy, with indications from diagnosis to treatment[73-75]. In addition, promising AI results have also emerged for adenoma and polyp detection rates[76]. However, to date, the assessment of bowel preparation has been performed by the general application of scales by an endoscopist. Thus, assessment of bowel preparation is strongly dependent on the endoscopist[1].

However, even in bowel preparation, AI systems have been used in various experiments. For example, the ENDOANGEL system, which is based on deep convolutional neural network (CNN) technology, showed a higher BBPS calculation accuracy than operators with less than one year of experience, and operators with more than three years of experience. Furthermore, ENDOANGEL has an overall accuracy in classifying colonoscopy images of 91.89% and was associated with a 30-second reminder system for the endoscopist on bowel preparation assessment. Such a reminder system has the potential to overcome the limitations of BBPS. The reminder system is based on the selection of representative segments of different colic localisations. In contrast, this system is based on continuous video images, which are more representative of the bowel preparation of the whole colon[77]. The experience of Lee et al[78] also supports the use of AI systems, using two CNN algorithms and set on a BBPS. This study also provided encouraging results with an accuracy for inadequate bowel preparation of 85.3%, and an area under the curve of more than 0.8 (0.918).

Furthermore, the κ index of agreement between raters without and with AI was similar. Su et al[79] developed an automated quality control system for lower endoscopy, based on CNN. However, the system was not explicitly designed for exclusive evaluation of bowel preparation. Instead, it evaluated the withdrawal phase and stability, as well as the detection rate of colorectal polyps. In addition, the CNN system showed significant superiority in evaluating bowel preparation.

Ultimately, despite the paucity of available studies, the applications of AI and CNN in the real-time assessment of bowel preparation have non-negligible potential. Such an application may have a positive impact, improving several parameters including accuracy in the assessment of bowel preparation, prediction of the difficulty of caecal intubation, and estimation of the sensitivity of the examination in cancer screening.

CONCLUSION

Bowel preparation remains one of the main difficulties encountered by IBD patients undergoing colonoscopy. In general, PEG-based preparations appear to have the best safety profile and are recommended by endoscopic reference scientific societies for patients with IBD. Indeed, the timing of bowel preparation plays a relevant role, with split regimens being preferred. Caution must be exercised in patients with active intestinal inflammation due to the risk of mucosal damage associated with bowel preparation. New forms of preparation are emerging in both modalities, such as retrograde technology, with the integration of AI into quality assessment. However, new evidence is needed to enable tailoring of preparations to individual IBD patients. This will improve patient compliance and procedure efficacy.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: November 11, 2022

First decision: November 30, 2022

Article in press: February 15, 2023

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Iizuka M, Japan; Wu SC, China S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Liu JH

Contributor Information

Antonietta Gerarda Gravina, Department of Precision Medicine, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Naples 80138, Italy. antoniettagerarda.gravina@unicampania.it.

Raffaele Pellegrino, Department of Precision Medicine, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Naples 80138, Italy.

Mario Romeo, Department of Precision Medicine, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Naples 80138, Italy.

Giovanna Palladino, Department of Precision Medicine, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Naples 80138, Italy.

Marina Cipullo, Department of Precision Medicine, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Naples 80138, Italy.

Giorgia Iadanza, Department of Precision Medicine, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Naples 80138, Italy.

Simone Olivieri, Department of Precision Medicine, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Naples 80138, Italy.

Giuseppe Zagaria, Department of Precision Medicine, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Naples 80138, Italy.

Nicola De Gennaro, Department of Precision Medicine, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Naples 80138, Italy.

Antonio Santonastaso, Department of Precision Medicine, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Naples 80138, Italy.

Marco Romano, Department of Precision Medicine, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Naples 80138, Italy.

Alessandro Federico, Department of Precision Medicine, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Naples 80138, Italy.

References

- 1.Millien VO, Mansour NM. Bowel Preparation for Colonoscopy in 2020: A Look at the Past, Present, and Future. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2020;22:28. doi: 10.1007/s11894-020-00764-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parekh PJ, Oldfield EC 4th, Johnson DA. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: what is best and necessary for quality? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2019;35:51–57. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maaser C, Sturm A, Vavricka SR, Kucharzik T, Fiorino G, Annese V, Calabrese E, Baumgart DC, Bettenworth D, Borralho Nunes P, Burisch J, Castiglione F, Eliakim R, Ellul P, González-Lama Y, Gordon H, Halligan S, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Kotze PG, Krustinš E, Laghi A, Limdi JK, Rieder F, Rimola J, Taylor SA, Tolan D, van Rheenen P, Verstockt B, Stoker J European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO] and the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology [ESGAR] ECCO-ESGAR Guideline for Diagnostic Assessment in IBD Part 1: Initial diagnosis, monitoring of known IBD, detection of complications. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:144–164. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke WT, Feuerstein JD. Colorectal cancer surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease: Practice guidelines and recent developments. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:4148–4157. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i30.4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valibouze C, Desreumaux P, Zerbib P. Post-surgical recurrence of Crohn's disease: Situational analysis and future prospects. J Visc Surg. 2021;158:401–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2021.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kishi M, Hirai F, Takatsu N, Hisabe T, Takada Y, Beppu T, Takeuchi K, Naganuma M, Ohtsuka K, Watanabe K, Matsumoto T, Esaki M, Koganei K, Sugita A, Hata K, Futami K, Ajioka Y, Tanabe H, Iwashita A, Shimizu H, Arai K, Suzuki Y, Hisamatsu T. A review on the current status and definitions of activity indices in inflammatory bowel disease: how to use indices for precise evaluation. J Gastroenterol. 2022;57:246–266. doi: 10.1007/s00535-022-01862-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, D'Amico F, Dhaliwal J, Griffiths AM, Bettenworth D, Sandborn WJ, Sands BE, Reinisch W, Schölmerich J, Bemelman W, Danese S, Mary JY, Rubin D, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Dotan I, Abreu MT, Dignass A International Organization for the Study of IBD. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1570–1583. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navaneethan U, Kochhar G, Phull H, Venkatesh PG, Remzi FH, Kiran RP, Shen B. Severe disease on endoscopy and steroid use increase the risk for bowel perforation during colonoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:470–475. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thoreson R, Cullen JJ. Pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease: an overview. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ji D. Oral magnesium sulfate causes perforation during bowel preparation for fiberoptic colonoscopy in patients with colorectal cancer. J Emerg Med. 2012;43:716–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung JW, Lee JM, Sohn YW, Han WC, Yoon K. Ischemic Colitis Associated with Low-volume Oral Sulfate Solution for Bowel Preparation. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2020;75:216–219. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2020.75.4.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Leo M, Iannone A, Arena M, Losurdo G, Palamara MA, Iabichino G, Consolo P, Rendina M, Luigiano C, Di Leo A. Novel frontiers of agents for bowel cleansing for colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:7748–7770. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i45.7748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gould SR, Williams CB. Castor oil or senna preparation before colonoscopy for inactive chronic ulcerative colitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1982;28:6–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(82)72955-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis GR, Santa Ana CA, Morawski SG, Fordtran JS. Development of a lavage solution associated with minimal water and electrolyte absorption or secretion. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:991–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazzaroni M, Petrillo M, Desideri S, Bianchi Porro G. Efficacy and tolerability of polyethylene glycol-electrolyte lavage solution with and without simethicone in the preparation of patients with inflammatory bowel disease for colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1993;7:655–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1993.tb00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corsetti M, Landes S, Lange R. Bisacodyl: A review of pharmacology and clinical evidence to guide use in clinical practice in patients with constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33:e14123. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kastenberg D, Bertiger G, Brogadir S. Bowel preparation quality scales for colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2833–2843. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i26.2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hassan C, East J, Radaelli F, Spada C, Benamouzig R, Bisschops R, Bretthauer M, Dekker E, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ferlitsch M, Fuccio L, Awadie H, Gralnek I, Jover R, Kaminski MF, Pellisé M, Triantafyllou K, Vanella G, Mangas-Sanjuan C, Frazzoni L, Van Hooft JE, Dumonceau JM. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019;51:775–794. doi: 10.1055/a-0959-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shamatutu C, Chahal D, Tai IT, Kwan P. Ischemic Colitis after Colonoscopy with Bisacodyl Bowel Preparation: A Report of Two Cases. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2020;2020:8886817. doi: 10.1155/2020/8886817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomer O, Shapira Y, Kriger-Sharabi O, Mawasi N, Melzer E, Epshtein J, Ackerman Z. An Israeli national survey on ischemic colitis induced by pre-colonoscopy bowel preparation (R1) Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2022;85:94–96. doi: 10.51821/88.1.8676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawrensia S, Raja A. Bisacodyl. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2022. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547733/

- 22.Kim ES, Kim KO, Jang BI, Kim EY, Lee YJ, Lee HS, Jeon SW, Kim HJ, Kim SK Crohn’s and Colitis Association in Daegu-Gyeongbuk (CCAiD) Comparison of 4-L Polyethylene Glycol and 2-L Polyethylene Glycol Plus Ascorbic Acid in Patients with Inactive Ulcerative Colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2489–2497. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4634-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:620–625. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, Allan RN. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29–32. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maida M, Morreale GC, Sferrazza S, Sinagra E, Scalisi G, Vitello A, Vettori G, Rossi F, Catarella D, Di Bartolo CE, Schillaci D, Raimondo D, Camilleri S, Orlando A, Macaluso FS. Effectiveness and safety of 1L PEG-ASC preparation for colonoscopy in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53:1171–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2021.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehta JB, Singhal SB, Mehta BC. Ascorbic-acid-induced haemolysis in G-6-PD deficiency. Lancet. 1990;336:944. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92317-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi SI, Choi J. Ischaemic colitis caused by polyethylene glycol with ascorbic acid bowel preparation agent. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-245891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishii R, Sakai E, Nakajima K, Matsuhashi N, Ohata K. Non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia induced by a polyethylene glycol with ascorbate-based colonic bowel preparation. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2019;12:403–406. doi: 10.1007/s12328-019-00970-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neri B, Scarozza P, Giannarelli D, Sena G, Mossa M, Lolli E, Calabrese E, Biancone L, Grasso E, Di Iorio L, Troncone E, Monteleone G, Paoluzi OA, Del Vecchio Blanco G. Efficacy and tolerability of very low-volume bowel preparation in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;33:977–982. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000002167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohsen W, Williams AJ, Wark G, Sechi A, Koo JH, Xuan W, Bassan M, Ng W, Connor S. Prospective single-blinded single-center randomized controlled trial of Prep Kit-C and Moviprep: Does underlying inflammatory bowel disease impact tolerability and efficacy? World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:1090–1100. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i11.1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briot C, Faure P, Parmentier AL, Nachury M, Trang C, Viennot S, Altwegg R, Bulois P, Thomassin L, Serrero M, Ah-Soune P, Gilletta C, Plastaras L, Simon M, Dray X, Caillo L, Del Tedesco E, Abitbol V, Zallot C, Degand T, Rossi V, Bonnaud G, Colin D, Morel B, Winkfield B, Danset JB, Filippi J, Amiot A, Attar A, Levy J, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Vuitton L CLEAN Study Group. Efficacy, Tolerability, and Safety of Low-Volume Bowel Preparations for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: The French Multicentre CLEAN Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:1121–1130. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim KO, Kim EY, Lee YJ, Lee HS, Kim ES, Chung YJ, Jang BI, Kim SK, Yang CH. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of oral sulphate tablet for bowel preparation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A multicentre randomized controlled study. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16:1706–1713. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawrance IC, Willert RP, Murray K. Bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: prospective randomized assessment of efficacy and of induced mucosal abnormality with three preparation agents. Endoscopy. 2011;43:412–418. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loraine A. Bowel preparation agent inducing profound shock precolonoscopy. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-233406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonlusen G, Akgun H, Ertan A, Olivero J, Truong LD. Renal failure and nephrocalcinosis associated with oral sodium phosphate bowel cleansing: clinical patterns and renal biopsy findings. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:101–106. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-101-RFANAW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mojsiewicz-Pieńkowska K. Review of Current Pharmaceutical Applications of Polysiloxanes (Silicones). In: Thakur VK, Thakur MK, editors. Handbook of Polymers for Pharmaceutical Technologies. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2015: 363–381. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moolla M, Dang JT, Shaw A, Dang TNT, Tian C, Karmali S, Sultanian R. Simethicone decreases bloating and improves bowel preparation effectiveness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:3899–3909. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-07066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu X, Yuan M, Li Z, Fei S, Zhao G. The Efficacy of Simethicone With Polyethylene Glycol for Bowel Preparation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55:e46–e55. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bezzio C, Schettino M, Manes G, Andreozzi P, Arena I, Della Corte C, Costetti M, Devani M, Omazzi BF, Saibeni S. Tolerability of Bowel Preparation and Colonoscopy in IBD Patients: Results From a Prospective, Single-Center, Case–Control Study. Crohn’s & Colitis 360. 2020;2:otaa077. doi: 10.1093/crocol/otaa077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Houdeville C, Leenhardt R, Souchaud M, Velut G, Carbonell N, Nion-Larmurier I, Nuzzo A, Histace A, Marteau P, Dray X. Evaluation by a Machine Learning System of Two Preparations for Small Bowel Capsule Endoscopy: The BUBS (Burst Unpleasant Bubbles with Simethicone) Study. J Clin Med. 2022;11 doi: 10.3390/jcm11102822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oliva S, Cucchiara S, Spada C, Hassan C, Ferrari F, Civitelli F, Pagliaro G, Di Nardo G. Small bowel cleansing for capsule endoscopy in paediatric patients: a prospective randomized single-blind study. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.08.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papamichael K, Karatzas P, Theodoropoulos I, Kyriakos N, Archavlis E, Mantzaris GJ. Simethicone adjunct to polyethylene glycol improves small bowel capsule endoscopy imaging in non-Crohn's disease patients. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28:464–468. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu ZW, Zhan SG, Yang MF, Meng YT, Xiong F, Wei C, Li YX, Zhang DG, Xu ZL, Wu BH, Shi RY, Yao J, Wang LS, Li DF. Optimal Timing of Simethicone Supplement for Bowel Preparation: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;2021:4032285. doi: 10.1155/2021/4032285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim H, Ko BM, Goong HJ, Jung YH, Jeon SR, Kim HG, Lee MS. Optimal Timing of Simethicone Addition for Bowel Preparation Using Polyethylene Glycol Plus Ascorbic Acid. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:2607–2613. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05599-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daperno M, D'Haens G, Van Assche G, Baert F, Bulois P, Maunoury V, Sostegni R, Rocca R, Pera A, Gevers A, Mary JY, Colombel JF, Rutgeerts P. Development and validation of a new, simplified endoscopic activity score for Crohn's disease: the SES-CD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:505–512. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01878-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sipponen T, Nuutinen H, Turunen U, Färkkilä M. Endoscopic evaluation of Crohn's disease activity: comparison of the CDEIS and the SES-CD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:2131–2136. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ofstead CL, Wetzler HP, Johnson EA, Heymann OL, Maust TJ, Shaw MJ. Simethicone residue remains inside gastrointestinal endoscopes despite reprocessing. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44:1237–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ofstead CL, Hopkins KM, Eiland JE, Wetzler HP. Widespread clinical use of simethicone, insoluble lubricants, and tissue glue during endoscopy: A call to action for infection preventionists. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47:666–670. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2019.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Stiphout SH, Laros IF, van Wezel RA, Gilissen LP. Crystallization in the waterjet channel in colonoscopes due to simethicone. Endoscopy. 2016;48:E394–E395. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-120261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barakat MT, Huang RJ, Banerjee S. Simethicone is retained in endoscopes despite reprocessing: impact of its use on working channel fluid retention and adenosine triphosphate bioluminescence values (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gajera A, South C, Cronley KM, Ziebert JJ, Wrigh CH, Levitan O, Burleson DB, Johnson DA. High-Volume Colonic Lavage Is a Safe and Preferred Colonoscopy Preparation for Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Crohn’s & Colitis 360. 2022;4:otac024. doi: 10.1093/crocol/otac024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Restellini S, Kherad O, Bessissow T, Ménard C, Martel M, Taheri Tanjani M, Lakatos PL, Barkun AN. Systematic review and meta-analysis of colon cleansing preparations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:5994–6002. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i32.5994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manes G, Fontana P, de Nucci G, Radaelli F, Hassan C, Ardizzone S. Colon Cleansing for Colonoscopy in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: Efficacy and Acceptability of a 2-L PEG Plus Bisacodyl Versus 4-L PEG. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2137–2144. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Megna B, Weiss J, Ley D, Saha S, Pfau P, Grimes I, Li Z, Caldera F. Clear liquid diet before bowel preparation predicts successful chromoendoscopy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:373–379.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nett A, Velayos F, McQuaid K. Quality bowel preparation for surveillance colonoscopy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease is a must. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2014;24:379–392. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumar A, Shenoy V, Buckley MC, Durbin L, Mackey J, Mone A, Swaminath A. Endoscopic Disease Activity and Biologic Therapy Are Independent Predictors of Suboptimal Bowel Preparation in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Undergoing Colonoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:4851–4865. doi: 10.1007/s10620-022-07530-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fuschillo G, Celentano V, Rottoli M, Sciaudone G, Gravina AG, Pellegrino R, Marfella R, Romano M, Selvaggi F, Pellino G. Influence of diabetes mellitus on inflammatory bowel disease course and treatment outcomes. A systematic review with meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2022.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Capela TL, Silva VM, Freitas M, Magalhães RS, Gonçalves TC, De Castro FD, Moreira MJ, Cotter J. Disease and non-disease-related risk factors for inadequate bowel preparation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Should the strategy be different? Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95:AB111. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ryhlander J, Ringstrom G, Simrén M, Stotzer PO, Jakobsson S. Undergoing repeated colonoscopies - experiences from patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:1467–1472. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2019.1698649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barberio B, Zamani M, Black CJ, Savarino EV, Ford AC. Prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:359–370. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spina A, Mazzarella C, Dallio M, Romeo M, Pellegrino R, Durante T, Romano M, Loguercio C, Di Mauro M, Federico A, Gravina AG. The Lesson from the First Italian Lockdown: Impacts on Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms and Sleep Quality in Patients with Remission of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2022;17:109–119. doi: 10.2174/1574887117666220328125720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Depont F, Berenbaum F, Filippi J, Le Maitre M, Nataf H, Paul C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Thibout E. Interventions to Improve Adherence in Patients with Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Disorders: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pellegrino R, Pellino G, Selvaggi F, Federico A, Romano M, Gravina AG. Therapeutic adherence recorded in the outpatient follow-up of inflammatory bowel diseases in a referral center: Damages of COVID-19. Dig Liver Dis. 2022;54:1449–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2022.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Present DH. Toxic megacolon. Med Clin North Am. 1993;77:1129–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schwesinger WH, Levine BA, Ramos R. Complications in colonoscopy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1979;148:270–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Waye JD. The role of colonoscopy in the differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 1977;23:150–154. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(77)73622-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sugiyama M, Kusumoto E, Ota M, Kimura Y, Tsutsumi N, Oki E, Sakaguchi Y, Kusumoto T, Ikejiri K, Maehara Y. Induction of potentially lethal hypermagnesemia, ischemic colitis, and toxic megacolon by a preoperative mechanical bowel preparation: report of a case. Surg Case Rep. 2016;2:18. doi: 10.1186/s40792-016-0145-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chlumská A, Benes Z, Mukensnabl P, Zámecník M. Histologic findings after sodium phosphate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Diagnostic pitfalls of colonoscopic biopsies. Cesk Patol. 2010;46:37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang DH, Bang BW, Kwon KS, Kim HK, Shin YW. A Case of Thermal Esophageal Injury Induced by Sodium Picosulfate with Magnesium Citrate. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2017;2017:9879843. doi: 10.1155/2017/9879843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ze EY, Choi CH, Kim JW. Acute Gastric Injury Caused by Undissolved Sodium Picosulfate/Magnesium Citrate Powder. Clin Endosc. 2017;50:87–90. doi: 10.5946/ce.2016.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parra-Blanco A, Ruiz A, Alvarez-Lobos M, Amorós A, Gana JC, Ibáñez P, Ono A, Fujii T. Achieving the best bowel preparation for colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17709–17726. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i47.17709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, Hendy PA, Smith PJ, Limdi JK, Hayee B, Lomer MCE, Parkes GC, Selinger C, Barrett KJ, Davies RJ, Bennett C, Gittens S, Dunlop MG, Faiz O, Fraser A, Garrick V, Johnston PD, Parkes M, Sanderson J, Terry H IBD guidelines eDelphi consensus group, Gaya DR, Iqbal TH, Taylor SA, Smith M, Brookes M, Hansen R, Hawthorne AB. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019;68:s1–s106. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mitsala A, Tsalikidis C, Pitiakoudis M, Simopoulos C, Tsaroucha AK. Artificial Intelligence in Colorectal Cancer Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment. A New Era. Curr Oncol. 2021;28:1581–1607. doi: 10.3390/curroncol28030149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chahal D, Byrne MF. A primer on artificial intelligence and its application to endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:813–820.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hassan C, Spadaccini M, Iannone A, Maselli R, Jovani M, Chandrasekar VT, Antonelli G, Yu H, Areia M, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Bhandari P, Sharma P, Rex DK, Rösch T, Wallace M, Repici A. Performance of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy for adenoma and polyp detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93:77–85.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Deliwala SS, Hamid K, Barbarawi M, Lakshman H, Zayed Y, Kandel P, Malladi S, Singh A, Bachuwa G, Gurvits GE, Chawla S. Artificial intelligence (AI) real-time detection vs. routine colonoscopy for colorectal neoplasia: a meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36:2291–2303. doi: 10.1007/s00384-021-03929-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou J, Wu L, Wan X, Shen L, Liu J, Zhang J, Jiang X, Wang Z, Yu S, Kang J, Li M, Hu S, Hu X, Gong D, Chen D, Yao L, Zhu Y, Yu H. A novel artificial intelligence system for the assessment of bowel preparation (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:428–435.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee JY, Calderwood AH, Karnes W, Requa J, Jacobson BC, Wallace MB. Artificial intelligence for the assessment of bowel preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95:512–518.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2021.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Su JR, Li Z, Shao XJ, Ji CR, Ji R, Zhou RC, Li GC, Liu GQ, He YS, Zuo XL, Li YQ. Impact of a real-time automatic quality control system on colorectal polyp and adenoma detection: a prospective randomized controlled study (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:415–424.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]