Abstract

Background:

The contrast avoidance model (CAM) proposes that persons with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) are sensitive to sharp increases in negative emotion or decreases in positive emotion (i.e., negative emotional contrasts; NECs) and use worry to avoid NECs. Sensitivity to and avoidance of NECs could also be a shared feature of major depressive disorder (MDD) and social anxiety disorder (SAD).

Methods:

In a large college sample (N = 1,409), we used receiver operating characteristic analyses to examine the accuracy of a measure of emotional contrast avoidance in detecting probable GAD, MDD, and SAD.

Results:

Participants with probable GAD, MDD, and SAD all reported higher levels of contrast avoidance than participants without the disorder (Cohen’s d = 1.32, 1.62 and 1.53, respectively). Area under the curve, a measure of predictive accuracy, was .81, .87, and .83 for predicting probable GAD, MDD, and SAD, respectively. A cutoff score of 48.5 optimized predictive accuracy for probable GAD and SAD, and 50.5 optimized accuracy for probable MDD.

Conclusion:

A measure of emotional contrast avoidance demonstrated excellent ability to predict probable GAD, MDD, and SAD. Sensitivity to and avoidance of NECs appears to be a transdiagnostic feature of these disorders.

Keywords: generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, social anxiety disorder, transdiagnostic, contrast avoidance

1. Introduction

In view of the high rate of comorbidity between mood and anxiety disorders, research has increasingly focused on common mechanisms across multiple disorders (Barlow et al., 2016; Craske, 2012). A key promise of this transdiagnostic research is the identification of common mechanisms that can be targeted in interventions to address a range of psychological concerns. Meta-analyses have demonstrated strong efficacy of treatments targeting transdiagnostic mechanisms (Newby et al., 2015; Pearl & Norton, 2017). Thus, studying constructs involved in a range of mental disorders could have considerable clinical impact.

Repetitive negative thinking is considered one of the transdiagnostic mechanisms of emotional disorders (Ehring & Watkins, 2008; McEvoy et al., 2013). Studies found that repetitive negative thinking, such as worry and rumination, exacerbated negative emotional symptoms, and served as a gateway to various emotional disorders (Newman et al., 2017; Newman et al., 2013; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). However, there has been limited exploration of why individuals with emotional disorders do not stop engaging with repetitive negative thinking even though these thinking processes worsen their emotional problems. Thus, transdiagnostic research should seek to identify mechanisms that could contribute to repetitive negative thinking across emotional disorders.

The contrast avoidance model (CAM) has arisen in response to the absence of an explanation of why people engage in repetitive negative thinking (for a full review, see Newman & Llera, 2011). CAM was originally formulated to explain pathological worry in generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). According to the model, individuals with GAD have an aversion to a sharp increase in negative and decrease in positive emotions (Tenet 1). CAM explains that worry increases and sustains anxiety (Tenet 2), and this pre-charged anxiety enables avoidance of a subsequent surge in negative affect when worrisome events are happening (Tenet 3). This process is called the avoidance of a negative emotional contrast (NEC). The model also suggests that when there is a positive outcome or if the worrisome event does not happen, the person experiences a shift from a negative affective state (induced by worry) to a less distressing state of relief or surge in positive affect (Tenet 4). This is termed a positive emotional contrast (PEC). CAM suggests that negative and positive reinforcement resulting from avoidance of NECs and increased probability of PECs enhances anxious individuals’ positive beliefs about worry, engendering further worry (Newman & Llera, 2011; Newman et al., 2013).

During the past decade, research has provided strong evidence supporting CAM. Laboratory studies found that worry facilitated the avoidance of NECs upon exposure to negative emotional experiences (Jamil & Llera, 2021; Kim & Newman, 2022; Llera & Newman, 2010, 2014; Skodzik et al., 2016; Stapinski et al., 2010). Daily diary and ecological momentary assessments found that worry decreased the likelihood and intensity of NECs, but increased the likelihood and intensity of PECs (Crouch et al., 2017; Newman et al., 2019; Newman et al., 2022; Vîslă et al., 2021). Although prior evidence for NECs and PECs primarily demonstrated increases and decreases in negative emotion (e.g., fear, sadness) respectively, emerging studies suggest that these constructs can also take the form of decreases and increases in positive emotion (e.g., happiness, contentedness), respectively (Llera & Newman, 2017; Newman et al., 2022). Studies also found that individuals with GAD reported a stronger preference for worry in coping with NECs (Jamil & Llera, 2021; Kim & Newman, 2022; Llera & Newman, 2014, 2017) than healthy individuals. Thus, CAM has garnered substantial empirical support for explaining the occurrence of worry in GAD.

Some research has suggested that sensitivity to NECs is not limited to GAD but could also be a feature of major depressive disorder (MDD). Persons with MDD appear prone to strong increases in negative emotion in reaction to negative events. For example, experience sampling studies have indicated that higher depressive symptoms were associated with a larger increase in negative emotions upon the occurrence of negative events (Ha et al., 2019), and persons with MDD reported daily events to be more unpleasant than did healthy controls (Bylsma et al., 2011). Thus, persons with MDD may be susceptible to experiencing NECs and therefore wish to avoid them. In fact, Nolen-Hoeksema et al. (2008) proposed that rumination, a common form of repetitive negative thinking in MDD, creates a sustained sense of helplessness and thus enables avoidance of an increase in negative emotions from failed efforts to try to control situations. In this way, depressed individuals may actively ruminate to avoid an NEC. Some preliminary studies have provided direct evidence for contrast avoidance and its link to repetitive negative thinking in MDD. For example, in two experimental studies, both worry and rumination facilitated avoidance of a negative contrast in participants with MDD or GAD (Jamil & Llera, 2021; Kim & Newman, 2022). Furthermore, individuals with GAD and those with MDD both had a greater sensitivity to NECs compared to individuals with neither disorder (Jamil & Llera, 2021; Kim & Newman, 2019). Additionally, one study found that higher self-reported levels of sensitivity to NECs were concurrently and prospectively related to symptoms of MDD. Sensitivity to NECs was also concurrently related to rumination (White et al., 2021). These findings suggest that CAM is not a process just limited to worry and GAD, but it may underlie other types of repetitive negative thinking and related emotional disorders such as rumination and MDD.

Another emotional disorder that could be characterized by contrast avoidance is social anxiety disorder (SAD). Like persons with GAD, persons with SAD may have difficulty with strong increases in negative emotion. For example, in a laboratory study, persons with SAD (relative to healthy controls) displayed stronger reactivity to socially threatening stimuli in terms of both subjective negative emotion and activity in emotion-linked brain regions (Goldin et al., 2009). Research in the child literature has also indicated greater subjective negative emotional reactivity to adverse stimuli in the laboratory and in daily life among individuals with GAD and SAD (Carthy et al., 2010; Tan et al., 2012). The propensity toward strong negative emotional reactions in SAD could cause fear of NECs as in GAD. Furthermore, like persons with GAD, persons with SAD engage in forms of repetitive negative thinking, termed “anticipatory processing” and “post-event processing”, which bear a close resemblance to worry and rumination, respectively (Wong, 2016). As with worry and rumination, these forms of repetitive negative thinking generate and sustain negative emotion (Dannahy & Stopa, 2007; Vassilopoulos, 2004), and could thus play a role in avoiding subsequent NECs. Indeed, one study found that subjective emotional reactivity partly mediated the link between social anxiety and post-event processing (Çek et al., 2016), indicating that emotional reactivity could partly explain post-event processing in SAD. Thus, there is preliminary evidence that persons with SAD may be susceptible to NECs and could attempt to avoid NECs by generating and sustaining negative emotions via anticipatory and post-event processing.

In sum, the reviewed literature suggests that sensitivity to and avoidance of an NEC could be common across GAD, MDD, and SAD. It is possible that fear of an NEC might be a common factor driving and maintaining these three disorders. However, given that the disorders may not always entail worrying as a means for contrast avoidance, investigating the CAM transdiagnostically with respect to all three mental disorders requires capturing sensitivity to and avoidance of NECs in a flexible manner. The Contrast Avoidance Questionnaire-General Emotion (CAQ-GE; Llera & Newman, 2017) is an assessment instrument that was developed to examine sensitivity to and avoidance of NECs, irrespective of the method used to enact this avoidance (i.e., contrast avoidance via worry, rumination, or any other means). This measure is contrasted with the Contrast Avoidance Questionnaire-Worry (CAQ-W; Llera & Newman, 2017), which specifically assesses the use of worry to avoid negative emotional contrasts. We chose to use the CAQ-GE because those with GAD, MDD, and SAD may not always avoid emotional contrasts via worry (e.g., rumination, anticipatory and post-event processing, focusing on the negative). The CAQ-GE makes no reference to the method of avoiding emotional contrasts, and therefore is the strongest candidate measure to assess contrast avoidance as a transdiagnostic construct. Studies reported good psychometric properties of the CAQ-GE (Javaherirenani et al., 2021; Llera & Newman, 2017; Rogers et al., 2023; White et al., 2021). Thus, the CAQ-GE was used to examine whether CAM might be a common construct within the three disorders.

To date, two studies examining the original and translated versions of the CAQ-GE have found a significant and strong correlation between the CAQ-GE and GAD (r = .80) and the CAQ-GE and MDD (r = .63) symptoms (Javaherirenani et al., 2021; White et al., 2021), providing preliminary evidence for the relevance of CAM across GAD and MDD. An additional study examined the sensitivity and specificity of the CAQ-GE in predicting GAD and found a sensitivity of 89.7% and a specificity of 89.3% accounting for an area under the curve of 96% (Llera & Newman, 2017). However, no studies to date have examined the CAQ-GE scores in relation to SAD. Additionally, no studies have examined scores on the CAQ-GE as they relate to clinical-level presentations of MDD and SAD. Examining CAQ-GE scores among those with vs. without a clinically severe level of GAD, MDD, and SAD would address the relevance of contrast avoidance to each of these three clinical syndromes, above and beyond the relationship between contrast avoidance and higher vs. lower levels of symptoms of each disorder. Thus, transdiagnostic work should examine scores on the CAQ-GE among persons with probable GAD, MDD, and SAD, in comparison to persons without disorders. This approach could provide an idea of the level of self-reported contrast avoidance that could be expected among persons with each probable disorder. Ideally, such an investigation would also provide indices of accuracy in discriminating between the presence vs. absence of the disorder (e.g., sensitivity and specificity) to indicate how characteristic emotional contrast avoidance is of probable GAD, MDD, and SAD. Providing these advanced predictive accuracy metrics can also provide information about the utility of the CAQ-GE as a measure to screen for probable GAD, MDD, and SAD. In light of this gap in the literature, in the current study, we used a large sample to examine the accuracy of the CAQ-GE in predicting probable GAD, MDD, and SAD.

We collected data on the CAQ-GE as well as several validated screening measures for probable GAD, MDD, and SAD. We hypothesized that the CAQ-GE would be significantly higher among persons with probable GAD, MDD, and SAD, relative to persons who did not screen positive for any of these disorders, and that the CAQ-GE would have strong accuracy in detecting the presence of probable GAD, MDD, and SAD. Because CAM suggests that sensitivity to and avoidance of NECs could be relevant across emotional disorders, we did not have any hypotheses about the CAQ-GE performing better or worse in predicting a given probable disorder over another. This study provides a novel investigation of sensitivity to and avoidance of NECs as a possible transdiagnostic feature of GAD, MDD, and SAD.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were recruited using a mass screening of 1,458 undergraduate students at a public university in the northeastern United States. Because this study concerned the utility of the CAQ-GE in predicting probable GAD, SAD, and MDD, analyses used a subset of participants who completed the screening survey. The total analytic sample (N = 1,409) consisted of participants who were in at least one of the three ROC analyses. Among the total analytic sample, 1,033 (73.3%) participants were female, 365 (25.9%) were male, 11 (0.8%) identified themselves as other gender; 57 (4.0%) were African American, 159 (11.6%) were Asian American, 59 (4.2%) were Hispanic, 944 (67.0%) were Caucasian, 157 (11.1%) were Multiracial, 19 (1.3%) identified themselves as other, and 14 (1.0%) did not answer. The average age in the sample was 18.70 (SD = 1.53).

2.2. Measures

Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire-IV (GAD-Q-IV; Newman et al., 2002).

The GAD-Q-IV is a 9-item self-report diagnostic measure for GAD that assesses all DSM-5 criteria for GAD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The GAD-Q-IV was scored using a categorical scoring method, such that participants were determined to have probable GAD if they endorsed full diagnostic criteria. This scoring method demonstrated good sensitivity (89%) and specificity (82%) in detecting GAD as assessed via diagnostic interview (Moore et al., 2014).

Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996).

The BDI-II includes 21 items assessing presence and severity of MDD symptoms. Items are rated on a 0–3 Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater MDD symptom severity. Unlike the GAD-Q-IV, there is no validated way of mapping BDI-II items to DSM-5 criteria for MDD, and therefore item ratings were summed to yield a continuous total score. The measure has shown high internal consistency (α = .90 in the current sample) and 1-week retest reliability (r = .93; Beck et al., 1996), as well as convergent and divergent validity (Beck et al., 1996). A score of 20 or higher indicates moderate or greater depression (Beck et al., 1996). We used this cutoff to identify probable MDD in the sample. This cutoff previously showed sensitivity and specificity of .81 and .90 in detecting a diagnosis of MDD, respectively (Dozois et al., 1998).

Social Phobia Diagnostic Questionnaire (SPDQ; Newman et al., 2003).

The SPDQ is a 29-item self-report measure on symptoms of SAD based on DSM-5 criteria. The measure includes yes-no items (e.g., “Do you try to avoid social situations?”) and 5-point Likert scale items on fear and avoidance of various social situations (e.g., parties) as well as distress and interference from social anxiety. Like the GAD-Q-IV, the SPDQ assesses all DSM-5 criteria required for a diagnosis of SAD. Therefore, a categorical scoring method (requiring meeting full DSM-5 criteria for SAD) was used to determine whether or not a participant had probable SAD. Using this criterion scoring method, the SPDQ previously demonstrated sensitivity and specificity of .57 and .95, respectively (Newman et al., 2003).

Contrast Avoidance Questionnaire–General Emotion (CAQ-GE; Llera & Newman, 2017).

The CAQ-GE is a 25-item questionnaire that assesses the extent to which individuals create and sustain negative emotions to avoid negative contrasts in emotions and the degree to which individuals are uncomfortable with sharp increases in negative emotion or decreases in positive emotion. It also assesses efforts to increase the probability of an increase in positive emotion and decrease in negative emotion as well as discomfort with sustained positive emotion. Participants are instructed to respond on a Likert scale of 1 (“not at all true”) to 5 (“absolutely true”). The CAQ-GE showed excellent internal consistency (α = .95 in the current sample), strong 1-week retest reliability (r = .93; Llera & Newman, 2017), as well as good construct validity (Llera & Newman, 2017).

2.3. Procedures

All data collection was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the university at which data were collected. Students were invited through email to complete an online screening survey at the start of the Fall 2021 semester. Of the full sample of participants who completed the survey (N = 1,409), individuals were categorized as probable GAD (N = 312) if they met full diagnostic criteria for GAD on the GAD-Q-IV. They were included in the probable MDD subgroup (N = 381) if they scored 20 or higher on the BDI-II. They were included in the probable SAD group (N = 143) if they met full diagnostic criteria on the SPDQ. They were included in the nondisordered subgroup (N = 859) if they did not meet threshold for full diagnostic criteria of any of the three disorders. Three Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) analyses were conducted for examination of whether the CAQ-GE could accurately predict probable GAD (N = 1,171), probable MDD (N = 1,240), and probable SAD (N = 1,002). It was possible for a single participant to be in multiple groups, provided that they met selection criteria for a given group.

2.4. Data analysis

Missing data were handled using pairwise deletion in the ROC analyses. In Group 1 (N = 1,171), there were 41 participants with missing data on the CAQ-GE (3.5%), leaving a final sample of N = 297 with probable GAD and N = 833 who were nondisordered. In Group 2 (N = 1,240), there were 48 participants with missing data on the CAQ-GE (3.9%), leaving a final sample of N = 359 with probable MDD and 833 who were nondisordered. In Group 3 (N = 1,002), there were 32 cases with missing data on the CAQ-GE (3.2%), leaving a final sample of N = 137 with probable SAD and 833 who were nondisordered. Given the low missing data rates, we considered pairwise deletion an appropriate way to handle missing data (Tsikriktsis, 2005).

For descriptive analyses, we examined rates of comorbidity across probable GAD, MDD, and SAD. We also computed scale totals of the CAQ-GE and calculated means and standard deviations by subgroup. Means across the probable disorder vs. nondisordered subgroups were compared using independent samples t-tests, and the effect size of the difference was indexed by Cohen’s d. For Cohen’s d, a value of 0.2 was considered a small effect, 0.5 was considered a medium effect, and 0.8 or higher was considered a large effect.

For the predictive analyses, we used SPSS 23.0 to perform three ROC analyses to evaluate the ability of the CAQ-GE to predict (1) probable GAD (vs. nondisordered); (2) probable MDD (vs. nondisordered); (3) probable SAD (vs. nondisordered). An ROC analysis determines the sensitivity (percent of those in the probable disorder group correctly classified as belonging to the probable disorder group) and specificity (percent of those in the nondisordered group correctly classified as belonging to the nondisordered group) of all possible cut-off points on the CAQ-GE. We sought the optimal cut-off score for the CAQ-GE such that predictive accuracy was maximized based on sensitivity and specificity. An ROC curve was created by plotting sensitivity (true positive rates) against one minus specificity (false positive rates) for each possible cut-off point. This curve provides a visual representation of the accuracy of the CAQ-GE to detect disorder status. The closer the curve follows the left-hand border and then the top border of the ROC space, the more accurate the test. The closer the curve comes to the diagonal of the ROC space, the less accurate the test. The resulting area under the curve (AUC) was then calculated. The AUC represents the ability of the CAQ-GE to discriminate between participants with vs. without probable disorders. An area of one represents perfect discrimination whereas an area of .5 represents poor discrimination. AUC from .5 to .69 is considered poor, AUC from .7 to .79 is considered acceptable, AUC from .8 to .89 is considered excellent, and AUC .9 or higher is considered outstanding (Mandrekar, 2010). We also reported positive predictive value (PPV; percentage of those classified as having a probable disorder by the CAQ-GE who actually had a probable disorder) and the negative predictive value (NPV; percentage of those classified as not having a probable disorder by the CAQ-GE who did not have a probable disorder). Higher PPV and Higher NPV indicated better performance. Finally, we used the DeLong test in the pROC package (Robin et al., 2011) in R studio to pairwise compare the AUC values of the three ROC analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive analyses

There were 181 individuals with comorbidity between probable GAD and MDD, 72 individuals with comorbidity between probable GAD and SAD, 83 individuals with comorbidity between probable MDD and SAD, and 52 individuals with comorbidity between all three of probable GAD, MDD, and SAD.1 Descriptive statistics for the CAQ-GE across probable GAD (vs. nondisordered), probable MDD (vs. nondisordered), and probable SAD (vs. nondisordered) groups are shown in Table 1. Of note, independent samples t-tests indicated large and significant differences in CAQ-GE scores across the probable GAD vs. nondisordered groups, probable MDD vs. nondisordered groups, and probable SAD vs. nondisordered groups (Table 1). Thus, in descriptive terms, sensitivity to and avoidance of an NEC was transdiagnostically relevant across probable GAD, MDD, and SAD.

Table 1.

CAQ-GE scores by subgroup.

| Subgroup | N | M (SD) | t | df | P | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Probable GAD | 297 | 63.15 (20.08) | 19.55 | 1128 | < .001 | 1.32 |

| Nondisordered | 833 | 42.21 (14.03) | ||||

| Probable MDD | 359 | 67.51 (18.75) | 25.69 | 1190 | < .001 | 1.62 |

| Nondisordered | 833 | 42.21 (14.03) | ||||

| Probable SAD | 137 | 65.31 (20.38) | 16.61 | 968 | < .001 | 1.53 |

| Nondisordered | 833 | 42.21 (14.03) | ||||

Note. CAQ-GE = Contrast Avoidance Questionnaire–General Emotion. GAD = generalized anxiety disorder. MDD = major depressive disorder. SAD = social anxiety disorder. The “Nondisordered” subgroup was the same across all analyses.

3.2. ROC analyses

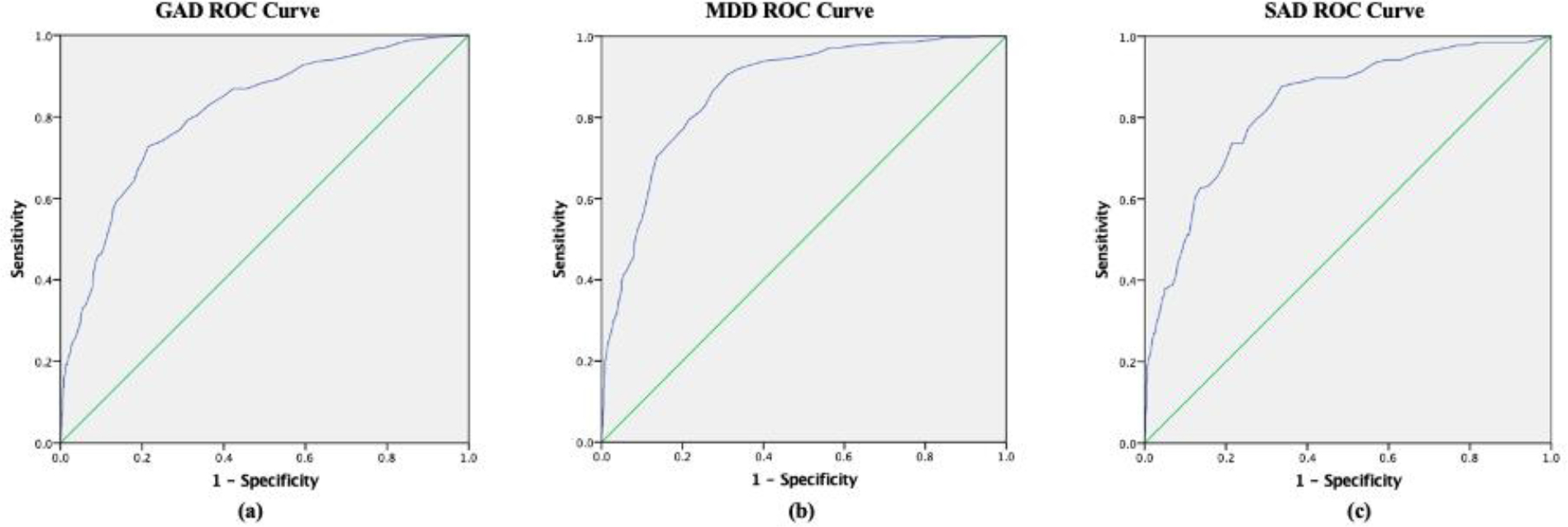

Table 2 presents area under the curve (AUC) values and their confidence intervals for the ROC analyses. The AUC values were significantly different from the null hypothesis that AUC = .50, p < .001, for all three analyses (Figure 1). The AUC values were .81, .87, and .83 for probable GAD, MDD, and SAD analyses, respectively, suggesting that the CAQ-GE possessed excellent accuracy in predicting each probable disorder.2 DeLong tests for ROC curves showed that the AUC value of the probable MDD ROC was significantly higher than the AUC value of the probable GAD ROC (D = 3.17, df = 2,106.5, p = .002), whereas the AUC value of the probable SAD ROC fell nonsignificantly in between the AUC value of the probable MDD ROC (D = −1.70, df = 1,571.9, p = .09) and the AUC value of the probable GAD ROC (D = 0.86, df = 1,893.8, p = .39)

Table 2.

Summary of ROC analyses statistics of the CAQ-GE.

| Target problem | AUC (SE) | AUC [95% CI] | Optimal cut-off score | Sensitivity % | Specificity % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Probable GAD | .81 (0.02) | [.78, .84] | 48.5 | 74.4 | 74.5 |

| Probable MDD | .87 (0.01) | [.85, .89] | 50.5 | 79.4 | 78.5 |

| Probable SAD | .83 (0.02) | [.79, .87] | 48.5 | 77.4 | 74.5 |

Note. ROC = receiver operating characteristics. CAQ-GE = Contrast Avoidance Questionnaire–General Emotion. AUC = area under the curve. CI = confidence interval. GAD = generalized anxiety disorder. MDD = major depressive disorder. SAD = social anxiety disorder.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the Contrast Avoidance Questionnaire–General Emotion (CAQ-GE) questionnaire to to detect the presence of a) generalized anxiety disorder; b) major depressive disorder; c) social anxiety disorder.

Sensitivity, specificity, correctly classified rates, and positive and negative predictive values were also calculated for a range of cutoff scores (Table 3). Results suggested that a cutoff score of 48.5 resulted in an optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity for probable GAD and SAD, and a cutoff score of 50.5 was optimal for probable MDD. Specifically, these cutoffs led to a sensitivity of .74% and a specificity of .75% to distinguish individuals with probable GAD from those without any disorder, a sensitivity of .79% and a specificity of .79% to distinguish individuals with probable MDD from those without any disorder, and a sensitivity of .77% and a specificity of .75% to distinguish individuals with probable SAD from those without any disorder, respectively.

Table 3.

Sensitivity, specificity, correctly classified rates, PPV, and NPV for Cutoff Score of the CAQ-GE

| Analysis | Cutoff score | Sensitivity % | Specificity % | Correctly Classified % | PPV % | NPV % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| GAD vs. no disorder | 44.5 | 80.50 | 66.40 | 70.11 | 46.07 | 90.52 |

| 45.5 | 79.10 | 68.90 | 71.58 | 47.56 | 90.24 | |

| 46.5 | 76.80 | 70.80 | 72.38 | 48.39 | 89.54 | |

| 47.5 | 75.80 | 72.60 | 73.44 | 49.66 | 89.38 | |

| 48.5 | 74.40 | 74.50 | 74.47 | 50.99 | 89.09 | |

| 49.5 | 73.70 | 75.90 | 75.32 | 52.16 | 89.00 | |

| 50.5 | 72.70 | 78.50 | 76.98 | 54.66 | 88.97 | |

|

|

||||||

| MDD vs. no disorder | 46.5 | 88.30 | 70.80 | 76.07 | 56.58 | 93.35 |

| 47.5 | 86.40 | 72.60 | 76.76 | 57.61 | 92.53 | |

| 48.5 | 82.70 | 74.50 | 76.97 | 58.29 | 90.90 | |

| 49.5 | 81.30 | 75.90 | 77.53 | 59.25 | 90.40 | |

| 50.5 | 79.40 | 78.50 | 78.77 | 61.41 | 89.84 | |

| 51.5 | 77.20 | 79.80 | 79.02 | 62.22 | 89.04 | |

| 52.5 | 76.30 | 80.80 | 79.44 | 63.14 | 88.78 | |

|

|

||||||

| SAD vs. no disorder | 44.5 | 87.60 | 66.40 | 69.39 | 30.01 | 97.02 |

| 45.5 | 83.20 | 68.90 | 70.92 | 30.55 | 96.14 | |

| 46.5 | 81.00 | 70.80 | 72.24 | 31.33 | 95.77 | |

| 47.5 | 79.60 | 72.60 | 73.59 | 32.33 | 95.58 | |

| 48.5 | 77.40 | 74.50 | 74.91 | 33.30 | 95.25 | |

| 49.5 | 73.70 | 75.90 | 75.59 | 33.46 | 94.61 | |

| 50.5 | 73.70 | 78.50 | 77.82 | 36.05 | 94.78 | |

Note. CAQ-GE = Contrast Avoidance Questionnaire–General Emotion. PPV = positive predictive value. NPV = negative predictive value. GAD = generalized anxiety disorder. MDD = major depressive disorder. SAD = social anxiety disorder.

The row in bold type indicates the cut-off score that achieves the optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity.

4. Discussion

The present study explored the transdiagnostic application of CAM by examining the accuracy of the CAQ-GE, a measure of sensitivity to and avoidance of NECs, in predicting positive screens for GAD, MDD, and SAD. The CAQ-GE had excellent accuracy in predicting all three disorders, with AUC estimates of .81, .87, and .83 for probable GAD, MDD, and SAD, respectively. In addition, mean scores on the CAQ-GE were significantly different for all three disorders than the nondisordered sample with large effect sizes. Thus, all three mental health conditions appeared to be characterized by sensitivity to and avoidance of NECs, providing some of the first evidence for contrast avoidance as a transdiagnostic feature of these three probable disorders.

Findings of this study converge with those of prior research on CAM, suggesting that the CAQ-GE can accurately discriminate between those with vs. without probable clinical levels of GAD (Llera & Newman, 2017). Findings also extend prior research by providing the first evidence that the CAQ-GE could accurately detect probable clinical levels of MDD and SAD. Thus, contrast avoidance could be a shared feature across each of GAD, MDD, and SAD. The cutoff scores that maximized predictive accuracy were similar across the three disorders: 48.5 for probable GAD and SAD and 50.5 for probable MDD. This score is somewhat higher than the cutoff score of 44.5 identified by Llera and Newman (2017) as optimal for detecting GAD. Of note, in the present study, the comparison group was individuals without a probable diagnosis, whereas in Llera and Newman (2017), the comparison group had especially low levels of GAD symptoms (below 4 on the GAD-Q-IV and 1 standard deviation below the mean on the Penn State Worry Questionnaire; Meyer et al., 1990). This may explain the stronger AUC findings of .96 in Llera and Newman (2017) for discriminating probable GAD. Thus, the cutoff scores of 48.5 and 50.5 appear to perform well in screening contexts where persons with probable GAD, MDD, and SAD must be distinguished from persons without these disorders, some of whom may have subclinically elevated symptoms. These cutoffs may be especially useful in naturalistic screening contexts with persons with a wide range of psychopathological severity (ranging from absent to subthreshold to clinical). In descriptive terms, participants in the probable GAD, MDD, and SAD sub-groups reported average CAQ-GE scores of 63.15, 67.52, and 65.31, respectively; this corresponds to an average item score of approximately 2.5 out of 5. Thus, these groups tended to report at least moderate agreement with statements about discomfort with NECs and creating and sustaining negative emotions to avoid NECs. This suggests that emotional contrast avoidance is a shared concern across GAD, MDD, and SAD.

It bears noting that although the CAQ-GE’s predictive accuracy was excellent in analyses of all three probable disorders, such accuracy (as measured by AUC) was highest for probable MDD and significantly higher than probable GAD. Thus, MDD could be a disorder especially characterized by sensitivity to and avoidance of NEC. Prior studies have suggested that persons with MDD experienced negative events as more unpleasant than persons without MDD (Bylsma et al., 2011), and higher depressive symptoms were related to larger increases in negative emotions when negative events occurred (Ha et al., 2019). Additionally, persons with MDD, but not persons with anxiety disorders, experienced greater variability and instability in sad mood than healthy participants (Lamers et al., 2018). Taking the present findings in this context, it is possible that persons with MDD are especially prone to sharp increases in negative emotion and therefore are especially sensitive to and avoidant of NECs. However, it is important to bear in mind that the CAQ-GE assesses general sensitivity to NECs and the general strategy of creating and sustaining negative emotions to avoid NECs. Therefore, it remains possible that persons with GAD use worry to avoid NECs to a greater extent than those with MDD or SAD. In fact, in an experimental study, participants with GAD (but not MDD) were more likely than healthy participants to prefer coping with fear contrasts using worry (Kim & Newman, 2022). In addition, White et al. (2021) found that whereas the CAQ-W (which measures contrast avoidance using worry) predicted future worry, the CAQ-GE tended to predict future depression symptoms. Also, Llera and Newman (2017) found that the CAQ-W performed slightly better than the CAQ-GE in detecting GAD. Unfortunately, the present study did not include the CAQ-W and therefore could not test both measures in tandem. Another important point is that for all three probable disorders the CAQ-GE had high predictive accuracy and all AUCs would be considered to be in the “excellent” range (Mandrekar, 2010). Thus, the most clear implication of the findings is that contrast avoidance is relevant to each of probable GAD, MDD, and SAD. Future studies should continue to examine CAM in depressed and socially anxious groups.

Given that the CAQ-GE assesses general sensitivity to and avoidance of NECs, the findings call for future research examining the specific phenomenon of contrast avoidance in each of MDD, GAD, and SAD. For example, it would be useful to identify the kinds of situations most likely to provoke NECs in GAD, MDD, and SAD, as well as the situations in which persons with GAD, MDD, and SAD are most likely to create and sustain negative emotions in an effort to avoid NECs and increase the probability of PECs. These questions could be addressed using experience sampling methods that capture emotions in daily life. Initial research on GAD suggests that social interactions can be contexts that provoke NECs, and that worry may function to avoid NECs in social interactions (Newman et al., 2022). Given that those with MDD and SAD (as well as those with GAD) report high rates of interpersonal problems, we suspect it is likely that social interactions are also situations that could evoke NECs in MDD and SAD and that persons with MDD and SAD may attempt to avoid NECs from social interactions. Specifically, with respect to SAD, it would be informative to investigate the occurrence and avoidance of NECs related to being either positively or negatively evaluated by others, given that persons with high social anxiety report fear of both (Carleton et al., 2007; Wallace & Alden, 1995, 1997; Weeks et al., 2008). Examining the extent to which persons with GAD, MDD, and SAD are sensitive to and avoid NECs resulting from these events would also be useful to contextualize contrast avoidance for each of these disorders.

The results of this research warrant investigation of the possible mechanistic role of contrast avoidance as it relates to repetitive negative thinking in GAD, MDD, and SAD. The CAM suggests that persons with GAD use worry to generate and sustain negative emotions and thereby avoid an NEC. Other theoretical models suggest that rumination could serve to sustain beliefs about uncontrollability and behavioral disengagement in depression (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008); given that a natural consequence of uncontrollability beliefs and disengagement is to keep a person feeling hopeless, rumination could serve to avoid NECs in depression. Additionally, subjective emotional reactivity partly mediated the relationship between social anxiety and post-event processing (Çek et al., 2016), providing indirect evidence for the notion that susceptibility to NECs could drive repetitive negative thinking in social anxiety. All three emotional disorders are characterized by engagement in one or more forms of repetitive negative thinking (e.g., worry, rumination, anticipatory processing, or post-event processing; Newman et al., 2013; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Wong, 2016), and each characteristic form of repetitive negative thinking has been found to generate and sustain negative emotions (Dannahy & Stopa, 2007; Jamil & Llera, 2021; Kim & Newman, 2022; Llera & Newman, 2014; Newman et al., 2019; Vassilopoulos, 2004). In light of this prior evidence and results from the present study, repetitive negative thinking could be employed as a means of avoiding NECs in all three disorders. It would be informative for future research to study how contrast avoidance functions in relation to different types of repetitive negative thinking and emotion across GAD, MDD, and SAD. A laboratory study found that worry tended to generate more fear than sadness, whereas rumination was more likely to generate more sadness than fear (Kim & Newman, 2022). Furthermore, worry was especially effective in avoiding fear contrasts (i.e., sharp increases in fear), whereas rumination was especially effective in avoiding sadness contrasts (i.e., sharp increases in sadness). Nonetheless, as noted above, persons with GAD (but not MDD) were more likely than controls to prefer coping with fear contrasts using worry (Kim & Newman, 2022). Thus, although contrast avoidance and repetitive negative thinking may be transdiagnostic to GAD, MDD, and SAD, there may be characteristic methods of employing repetitive negative thinking to avoid NECs and there may be particular sensitivity to contrasts related to specific types of emotion in each disorder. Relatedly, identifying factors in the development of contrast avoidance could inform transdiagnostic etiological models. Newman et al. (2013) theorized that harsh and overprotective parenting styles could impede the development of autonomy and skills for coping with unexpected negative events, leading to contrast avoidance and eventually GAD. Examining these parenting styles’ associations with contrast avoidance and with GAD, MDD, and SAD prospectively could illustrate long-term developmental pathways for these disorders.

The present study has implications for assessment and treatment of GAD, MDD, and SAD. First, a cutoff score on the CAQ-GE of 48.5 had the strongest accuracy in screening for probable GAD, and SAD, and a cutoff of 50.5 had the strongest accuracy in screening for probable MDD, suggesting that these scores could be useful to screen for probable diagnoses of any of these disorders. Additionally, given that individuals with all three probable disorders reported discomfort with NECs and creating and sustaining negative emotions to avoid NECs, it could be worthwhile for clinicians treating these conditions to open discussions with their clients about contrast avoidance. In the authors’ clinical experience, it is not uncommon for clients with emotional disorders to report using repetitive negative thinking to avoid disappointment. Probing these beliefs and providing psychoeducation has been helpful to show that repetitive negative thinking does nothing except make people feel worse during the time they are engaged in it. The CAM has thus been helpful to change clients’ attitudes toward repetitive negative thinking and the possibility of experiencing NECs. It would also be worthwhile to systematically investigate treatment approaches that can change beliefs about and avoidance of NECs. Newman and Llera (2011) proposed treating GAD by exposure to negative emotional contrasts; we are not aware of any study investigating this approach, though it is worth testing this approach in treating each of GAD, MDD, and SAD (e.g., for a person with SAD, shifting from a relaxing non-social situation to a feared social situation could facilitate an emotional contrast). Another approach that may be helpful is savoring positive emotional experiences. Part of CAM is that individuals are uncomfortable with sustained positive emotion because such positive emotion leaves them vulnerable to NECs. Thus, it may be that interventions that expose individuals to sustained positive emotion could also help to treat individuals with these three disorders (LaFreniere & Newman 2023). Given the high comorbidity between these problems, reducing contrast avoidance could prove invaluable in reducing symptoms of all three conditions.

We note several limitations of the present investigation. First, the study employed a cross-sectional design. Although this design enabled investigating the accuracy of the CAQ-GE in detecting the presence of probable GAD, MDD, and SAD, it could not address important questions related to the role of contrast avoidance in the etiology and maintenance of these disorders. A prior investigation documented a positive relationship between CAQ-GE scores and future depression symptoms (White et al., 2021), though additional studies investigating the prospective relationship between contrast avoidance and GAD, MDD, and SAD are necessary to elucidate links between these constructs. Prospective investigations could also facilitate analysis of the relationship between contrast avoidance and other constructs relevant to GAD, MDD, and SAD (e.g., forms of repetitive negative thinking); such investigations are necessary to demonstrate that contrast avoidance is not only a correlate, but also a mechanism, of each condition. Another limitation of this study was its use of an undergraduate student sample. Although this method facilitated collecting a large sample of participants with and without each of probable GAD, MDD, and SAD, it also limited the potential generalizability of the results to community adult samples. A third limitation is that we cannot rule out the possibility that comorbidity could have influenced our findings. At the same time, high levels of comorbidity are prototypical of these disorders (Kessler et al., 2012) and only examining pure probable disorders would have left us with very unrepresentative and significantly smaller subsamples. This could have biased our results. Also, the goal of this study was simply to determine whether the CAQ-GE could accurately discriminate individuals with each probable disorder from nondisordered controls. Therefore, we decided to examine within each group anybody who scored highly on each disorder measure separately and to compare these AUC findings between disorders. Despite these limitations, this study substantially advances the literature on transdiagnostic processes in GAD, MDD, and SAD by providing the first investigation to our knowledge of the relationship between CAQ-GE scores and clinical levels of these disorders.

This study investigated the accuracy of the CAQ-GE, a measure of sensitivity to and avoidance of negative emotional contrasts, in detecting probable GAD, MDD, and SAD. The measure had excellent accuracy in detecting the probable presence of all three conditions, with AUC estimates of .81, .87, and .83 for probable GAD, MDD, and SAD, respectively. The results suggest that the CAQ-GE could be used to screen for GAD, MDD, and SAD. Furthermore, the results suggest that contrast avoidance is a shared feature across each of the disorders. The findings call for further research examining contrast avoidance as it occurs naturalistically in GAD, MDD, and SAD, as well as mechanistic research examining the longitudinal associations between contrast avoidance and repetitive negative thinking within these disorders. Such investigation will pave the way for transdiagnostic approaches to treat shared mechanisms across these emotional disorders.

Highlights.

Tested theories on the transdiagnostic nature of contrast avoidance across three disorders.

We tested those with and without probable generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder (SAD) and major depressive disorder (MDD).

Probable GAD, SAD, and MDD vs. controls scored significantly higher on the Contrast Avoidance Questionnaire-General Emotion scale (CAQ-GE).

Area under the curve, a test of predictive accuracy for the CAQ-GE, was .81, .87, and .83 for predicting probable GAD, MDD, and SAD, respectively.

A cutoff score of 48.5 optimized predictive accuracy for probable GAD and SAD and 50.5 opimized predictive accuracy for probable MDD.

Sensitivity to and avoidance of a negative emotional contrast appears to be a transdiagnostic feature of GAD, MDD, and SAD.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by National Institute of Mental Health Research Grant MH115128.

Footnotes

We did not exclude comorbid disorders from our probable GAD, MDD, and SAD samples as we believed it would be unrepresentative of these disorders in the real world.

We used the total CAQ-GE score because we had no apriori theoretical reason to expect one subscale to perform better than the other subscale and we had no hypotheses about the specific subscales. We also wanted to capture the full construct of contrast avoidance which includes efforts to create and sustain negative emotion to avoid NECs and discomfort with NECs. Nonetheless, AUC values were similar when compared between the two subscales or compared to total CAQ-GE scores for each disorder. Therefore, effects were not driven by any one subscale.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5; 5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Allen LB, & Choate ML (2016). Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders–republished article. Behavior Therapy, 47(6), 838–853. 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80036-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II): Manual and questionnaire. The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bylsma LM, Taylor-Clift A, & Rottenberg J (2011). Emotional reactivity to daily events in major and minor depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120(1), 155–167. 10.1037/a0021662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton RN, Collimore KC, & Asmundson GJ (2007). Social anxiety and fear of negative evaluation: construct validity of the BFNE-II. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(1), 131–141. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carthy T, Horesh N, Apter A, Edge MD, & Gross JJ (2010). Emotional reactivity and cognitive regulation in anxious children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(5), 384–393. 10.1016/j.brat.2009.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çek D, Sánchez A, & Timpano KR (2016). Social anxiety–linked attention bias to threat is indirectly related to post-event processing via subjective emotional reactivity to social stress. Behavior Therapy, 47(3)(Suppl. 377–387), 377–387. 10.1016/j.beth.2016.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG (2012). Transdiagnostic treatment for anxiety and depression. Depression and Anxiety, 29(9), 749–753. 10.1002/da.21992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch TA, Lewis JA, Erickson TM, & Newman MG (2017). Prospective investigation of the contrast avoidance model of generalized anxiety and worry. Behavior Therapy, 48(4), 544–556. 10.1016/j.beth.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannahy L, & Stopa L (2007). Post-event processing in social anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(6), 1207–1219. 10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJA, Dobson KS, & Ahnberg JL (1998). A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory–II. Psychological Assessment, 10(2), 83–89. 10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.83 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T, & Watkins ER (2008). Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic process. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 1(3), 192–205. 10.1521/ijct.2008.1.3.192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Manber T, Hakimi S, Canli T, & Gross JJ (2009). Neural bases of social anxiety disorder: Emotional reactivity and cognitive regulation during social and physical threat. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(2), 170–180. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha T, van Roekel E, Iida M, Kornienko O, Engels R, & Kuntsche E (2019). Depressive symptoms amplify emotional reactivity to daily perceptions of peer rejection in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(11), 2152–2164. 10.1007/s10964-019-01146-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamil N, & Llera SJ (2021). A transdiagnostic application of the contrast-avoidance model: The effects of worry and rumination in a personal-failure paradigm. Clinical Psychological Science, 9(5), 836–849. 10.1177/2167702621991797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Javaherirenani R, Ahadianfard P, & Ashouri A (2021). Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of General Emotion Questionnaire-Contrast Avoidance Model. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 15(4). e114376. 10.5812/ijpbs.114376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Lakoma MD, Petukhova M, . . . Merikangas KR (2012). Lifetime co-morbidity of DSM-IV disorders in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Psychological Medicine, 1–14. 10.1017/S0033291712000025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, & Newman MG (2019). The paradox of relaxation training: Relaxation induced anxiety and mediation effects of contrast avoidance in generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 259, 271–278. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, & Newman MG (2022). Avoidance of a negative emotional contrast from worry and rumination: An application of the contrast avoidance model. Journal of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy, 32(1), 33–43. 10.1016/j.jbct.2021.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFreniere LS, & Newman MG (2023). Reducing contrast avoidance in GAD by savoring positive emotions: Outcome and mediation in a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 93, 102659. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers F, Swendsen J, Cui L, Husky M, Johns J, Zipunnikov V, & Merikangas KR (2018). Mood reactivity and affective dynamics in mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(7), 659–669. 10.1037/abn0000378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llera SJ, & Newman MG (2010). Effects of worry on physiological and subjective reactivity to emotional stimuli in generalized anxiety disorder and nonanxious control participants. Emotion, 10(5), 640–650. 10.1037/a0019351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llera SJ, & Newman MG (2014). Rethinking the role of worry in generalized anxiety disorder: Evidence supporting a model of Emotional Contrast Avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 45(3), 283–299. 10.1016/j.beth.2013.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llera SJ, & Newman MG (2017). Development and validation of two measures of emotional contrast avoidance: The Contrast Avoidance Questionnaires. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 49, 114–127. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandrekar JN (2010). Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. Journal of Thoracic Oncology, 5(9), 1315–1316. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ec173d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy PM, Watson H, Watkins ER, & Nathan P (2013). The relationship between worry, rumination, and comorbidity: Evidence for repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic construct. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(1), 313–320. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, & Borkovec TD (1990). Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28(6), 487–495. 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MT, Anderson NL, Barnes JM, Haigh EAP, & Fresco DM (2014). Using the GAD-Q-IV to identify generalized anxiety disorder in psychiatric treatment seeking and primary care medical samples. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(1), 25–30. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newby JM, McKinnon A, Kuyken W, Gilbody S, & Dalgleish T (2015). Systematic review and meta-analysis of transdiagnostic psychological treatments for anxiety and depressive disorders in adulthood. Clinical Psychology Review, 40(Suppl. C), 91–110. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Cho S, & Kim H (2017). Worry and generalized anxiety disorder: A review. Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology. 10.1016/B978-0-12-809324-5.05108-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Jacobson NC, Zainal NH, Shin KE, Szkodny LE, & Sliwinski MJ (2019). The effects of worry in daily life: An ecological momentary assessment study supporting the tenets of the contrast avoidance model. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(4), 794–810. 10.1177/2167702619827019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Kachin KE, Zuellig AR, Constantino MJ, & Cashman-McGrath L (2003). The Social Phobia Diagnostic Questionnaire: Preliminary validation of a new self-report diagnostic measure of social phobia. Psychological Medicine, 33(4), 623–635. 10.1017/S0033291703007669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, & Llera SJ (2011). A novel theory of experiential avoidance in generalized anxiety disorder: A review and synthesis of research supporting a Contrast Avoidance Model of worry. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(3), 371–382. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Llera SJ, Erickson TM, Przeworski A, & Castonguay LG (2013). Worry and generalized anxiety disorder: A review and theoretical synthesis of research on nature, etiology, and treatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 275–297. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Schwob JT, Rackoff GN, Shin KE, Kim H, & Van Doren N (2022). The naturalistic reinforcement of worry from positive and negative emotional contrasts: Results from a momentary assessment study within social interactions. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 92, 102634. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Zuellig AR, Kachin KE, Constantino MJ, Przeworski A, Erickson T, & Cashman-McGrath L (2002). Preliminary reliability and validity of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire-IV: A revised self-report diagnostic measure of generalized anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy, 33(2), 215–233. 10.1016/S0005-7894(02)80026-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, & Lyubomirsky S (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424. 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl SB, & Norton PJ (2017). Transdiagnostic versus diagnosis specific cognitive behavioural therapies for anxiety: A meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 46, 11–24. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez JC, & Muller M (2011). pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics, 12(77), 1–8. 10.1186/1471-2105-12-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers TA, Gorday JY, Bardeen JR, & Benfer N (2023). Examining the factor structure and incremental utility of the Contrast Avoidance Questionnaires via bifactor analysis. Journal of Personality Assessment, 105(2), 238–248. 10.1080/00223891.2022.2081921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodzik T, Zettler T, Topper M, Blechert J, & Ehring T (2016). The effect of verbal and imagery-based worry versus distraction on the emotional response to a stressful in-vivo situation. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 52, 51–58. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2016.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapinski LA, Abbott MJ, & Rapee RM (2010). Evaluating the cognitive avoidance model of generalised anxiety disorder: Impact of worry on threat appraisal, perceived control and anxious arousal. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(10), 1032–1040. 10.1016/j.brat.2010.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan PZ, Forbes EE, Dahl RE, Ryan ND, Siegle GJ, Ladouceur CD, & Silk JS (2012). Emotional reactivity and regulation in anxious and nonanxious youth: A cellphone ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(2), 197–206. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02469.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsikriktsis N (2005). A review of techniques for treating missing data in OM survey research. Journal of Operations Management, 24(1), 53–62. 10.1016/j.jom.2005.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilopoulos SPH (2004). Anticipatory processing plays a role in maintaining social anxiety. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 18(4), 321–332. 10.1080/10615800500258149 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vîslă A, Zinbarg R, Hilpert P, Allemand M, & Flückiger C (2021). Worry and positive episodes in the daily lives of individuals with generalized anxiety disorder: An ecological momentary assessment study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 722881. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.722881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace ST, & Alden LE (1995). Social anxiety and standard setting following social success or failure. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 19(6), 613–631. 10.1007/BF02227857 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace ST, & Alden LE (1997). Social phobia and positive social events: the price of success. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(3), 416–424. 10.1037/0021-843X.106.3.416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks JW, Heimberg RG, Rodebaugh TL, & Norton PJ (2008). Exploring the relationship between fear of positive evaluation and social anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(3), 386–400. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White EJ, Grant DM, Kraft JD, Taylor DL, Deros DE, Nagel KM, & Frosio KE (2021). Psychometric properties and prospective predictive utility of the Contrast Avoidance Questionnaires. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 37(6), 460–472. 10.1027/1015-5759/a000630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong QJJ (2016). Anticipatory processing and post-event processing in social anxiety disorder: An update on the literature. Australian Psychologist, 51(2), 105–113. 10.1111/ap.12189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]