Abstract

Many individuals diagnosed with cannabis use disorder (CUD) report a desire to quit using cannabis due to problems associated with use. Yet, successful abstinence is difficult for a large subset of this population. Thus, the present study sought to elucidate potential risk factors for cannabis use problems, perceived barriers for quitting, and diminished self-efficacy for remaining abstinent. Specifically, this investigation examined cigarette user status, anxiety sensitivity, and the interplay between these individual difference factors in terms of cannabis-related problems, perceived barriers for cannabis cessation, and self-efficacy for quitting cannabis use. The sample consisted of 132 adult cannabis users who met criteria for CUD and were interested in quitting (38% female; 63.6% Black; Mage = 37.22; SDage = 28.79; 54.6% current tobacco users). Findings revealed a significant interaction, such that anxiety sensitivity was related to cannabis use problems and perceived barriers for cannabis cessation among current cigarette users, but not among cigarette non-users. There was no significant interaction for self-efficacy for remaining abstinent. The current findings suggest that cigarette users constitute a subgroup that may be especially vulnerable to the effects of anxiety sensitivity in terms of cannabis use problems and perceived barriers for quitting cannabis use.

Keywords: Addictive Behavior, Cannabis Use Disorder, Anxiety Sensitivity, Self Efficacy, Perceived Barriers for Cessation, Cannabis Use Problems

Cannabis is one of the most used substances globally (Johnston et al., 2017), with rates of cannabis use increasing in the United States (US; Cerdá et al., 2012; SAMHSA, 2019). Increased cannabis use in the US is purported to be related to relaxed laws regarding the legalization of cannabis and the decreased perception of harm associated with cannabis use (Compton et al., 2016). For example, over 80% of individuals living in the US believe that cannabis can provide at least one benefit to users (Keyhani et al., 2018). Yet, frequent/heavy cannabis use is related to adverse health consequences, including damage to the lungs and airways (Vandrey et al., 2008), increased risk of developing lung cancer and respiratory disease (Aldington et al., 2008), elevations in anxiety and depression (Blanco et al., 2016; Crippa et al., 2009; Lev-Ran et al., 2014), and the presence of non-cannabis substance use disorders (Blanco et al., 2016). Furthermore, despite evidence-based treatments for cannabis use disorder (CUD), there is limited support for these treatments aiding in sustained abstinence (Sherman & McRae-Clark, 2016). Evidence suggests the success of treatment of CUD may be complicated by emotion regulatory issues, emotional distress (e.g., elevated negative affect), and concurrent use of additional substances (e.g., Baker et al., 2010).

There is growing evidence that anxiety sensitivity (AS) may be an important construct to consider within the context of cannabis misuse, (i.e., cannabis use that interferes with life functioning; Thake & Davis, 2011), and cannabis cessation difficulties (Zvolensky et al., 2018). AS is a transdiagnostic vulnerability factor reflecting an individual’s tendency to experience fear in response to anxious arousal symptoms and sensations that mimic such symptoms (Paulus et al., 2015; Reiss & McNally, 1985). Past work has shown a positive relationship between AS and the maintenance of substance use, such that heightened AS confers a greater likelihood of avoiding negative affect states by using substances (Buckner et al., 2011, 2014). Extant literature also indicates that those with elevated AS are likely to report greater cannabis withdrawal symptoms, cannabis use problems (Paulus et al., 2017) and maintain a higher frequency of use (Bonn-Miller et al., 2007; Buckner et al., 2011; Knapp et al., 2021; Paulus et al., 2017).

Although the direct effect of AS on cannabis outcomes is established (see Zvolensky et al., 2019), few studies have considered potential behavioral moderators of these relations. One addictive behavior of relevance that may influence the effect of AS on cannabis cessation-related outcomes is cigarette smoking. Indeed, cigarette use is common among cannabis users, with nearly 42% of current cannabis users reporting concurrent tobacco use (Akbar et al., 2019). Such data are of concern given that cannabis and cigarette co-use is associated with elevated levels of cannabis consumption, dependence, severity of withdrawal symptoms from both substances (Vandrey et al., 2008), and worse cannabis cessation outcomes compared to only cannabis users (McClure et al., 2018). Further, some work has found that global AS is related to more severe cannabis problems among current cigarette smokers who are concurrent cannabis users, but not among lifetime cannabis users who may or may not engage in current use (Guillot, Blumenthal, Zvolensky, & Schmidt, 2018). These data highlight the relevance of AS on cannabis use outcomes among current co-users, but no work has sought to empirically evaluate the differential effect of AS on cannabis-cessation processes across current cigarettes smoker status. Such work would have important clinical implications for co-users.

Theoretically, the effect of AS on cannabis problems and cessation-related difficulties may be especially salient among current cigarette smokers given that, compared to regular cannabis users, cigarette smokers may tend to use cannabis to help manage aversive anxiety-related physical sensations (Buckner et al., 2011). Indeed, dual cannabis and tobacco smokers are more likely to display respiratory distress, such as wheezing or exercise-induced shortness of breath, and waking during the night with chest tightness (Agrawal et al., 2012; Taylor et al., 2000). As such, cigarette smokers with increased AS may use cannabis to manage the uncomfortable interoceptive experiences that result from continued dual use and the manifestation of these symptoms through acute withdrawal, which may be related to greater perceived quit difficulty (Zvolensky, Kauffman, Garey, Viana, & Matoska, in press). Ultimately, these behavioral processes and patterns may confer worse cannabis-related processes (e.g., severity of cannabis use problems, beliefs about quitting, and self-efficacy for quitting). Further, such a theoretical model may be particularly relevant to current cannabis users with CUD as this group may be at increased risk for elevated internal perturbation distress and symptoms and concurrent cigarette use (Peters, et al., 2014; Weinberger et al., 2018).

The current study examined current cigarette smoking status as a moderator in the relation between AS and cannabis use processes among adults with CUD. Specific clinically significant constructs included cannabis use problems, perceived barriers for quitting cannabis, and self-efficacy for quitting cannabis (Budney et al., 2007; Hasin, 2018, Lee et al., 2019; Lees et al, 2021; Loflin et al., 2020). It was hypothesized that increased AS would be more related to increased cannabis use problems and perceived barriers to cannabis cessation, and lower related to self-efficacy for quitting, and that these relations would be stronger among cigarette users relative to non-users.

2. METHOD

2.1. Participants

The present sample consisted of 132 adult cannabis users (28.8% female; Mage= 37.22; SDage = 28.79) with CUD. Participants were recruited from 2012–2014 (see Hogan, 2015) via newspaper and community flyer advertisements targeting current cannabis users with a history of past (cannabis use) quit attempts. Inclusion criteria included being 18–65 years of age, using cannabis at least three times per week for the past six months, having at least two cannabis use quit attempts (lifetime) with at least one quit attempt occurring within the past 12 months, meeting DSM-IV criteria for current CUD, and being able to provide informed consent. CUD diagnoses were determined via semi-structured diagnostic interview (SCID-IV-TR; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996). Exclusion criteria included current suicidal or homicidal ideation, current psychosis, limited mental competency preventing ability to provide informed consent, currently enrolled in treatment for CUD or other substance use problems, recent legal mandate limiting cannabis use, prescribed use of medical cannabis for treatment of a medical disorder, being pregnant or currently breastfeeding, and an inability to provide informed, voluntary, written consent to participate. Participants were compensated with a $20.00 gift card. The current study utilized data from a study examining perceived and behavioral distress tolerance on various cannabis-related quit processes in individuals with cannabis use disorder (Hogan, 2015). A sub-set of the sample was selected based on available data. All procedures were approved by the affiliated university’s Institutional Review Board.

Participant demographics are presented in Table 1. In terms of self-identified racial composition, the study sample was 63.6% Black/African American, 28.0% White, 2.3% Asian, 0.6% Native American/Alaska Native, and 5.8% indicated ‘Other’; ethnically, 19.7% of the sample identified as Hispanic/Latino. Regarding education level, 27.1% earned a high school diploma, 46.5% received ‘some college,’ and 20.6% obtained a bachelor’s degree or higher. Participants reported using cannabis at an average rate of 5.9 (SD = 1.6) days per week. Over a third of the sample was identified as having a co-occurring anxiety disorder (39.4%), while 28.0% had a co-occurring mood disorder, and 15.9% had a non-CUD substance use disorder. Cigarette users and non-users did not significantly differ on presence of anxiety (X2(1)= .89, p=.35) or mood disorder (X(1)2 =.01, p= .94), but there was a difference for substance use (X2(1)= 7.02, p=.009) with cigarette users more likely to meet criteria for an additional substance disorder than non-cigarette users. On average, participants reported using cannabis at their weekly rate for 14.9 years (SD = 11.4). Over half of the sample (55.3%) reported joints as the main method of consuming cannabis, 25% reported blunt use, 10.6% used a bowl, and 6.1% reported using a bong. Nearly half of the present sample were current cigarette smokers (n = 72; 54.55%), averaging 9.7 (SD = 7.5; range 1–25) cigarettes per day. Among, cigarette smokers nicotine dependency was moderate per the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (M = 4.0; SD=1.6; Heatherton, et al. 1991). Among cigarette smokers nearly half reported also using cigars (45.8%), 4.2% reported using pipe tobacco and 8.3% reported using smokeless tobacco. Participants reported an average of 4.9 (SD = 2.7) cannabis use quit attempts in their lifetime.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristic of participants.

| Total | Non-cigarette users | Cigarette users | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/ n | SD / % | Mean/ n | SD / % | Mean/ n | SD / % | |

| Age | 37.62 | 11.63 | 39.52 | 10.43 | 35.33 | 12.64 |

| Sex (Males) | 94 | 71.21% | 39 | 65.0% | 55 | 76.4% |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 37 | 2.8% | 18 | 30.0% | 19 | 26.4% |

| Black | 84 | 63.6% | 37 | 61.7% | 47 | 65.3% |

| Asian | 3 | 2.3% | 1 | 1.7% | 2 | 2.8% |

| Native American/ Alaskan Native | 1 | 0.8% | 1 | 1.7% | 0 | 0% |

| Other | 7 | 5.3% | 3 | 5.0% | 4 | 5.6% |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Single | 88 | 66.7% | 41 | 68.3% | 47 | 65.3% |

| Living with Partner | 13 | 9.8% | 9 | 15.0% | 4 | 5.6% |

| Married | 12 | 9.1% | 6 | 10.0% | 6 | 8.3% |

| Divorced | 11 | 8.3% | 1 | 1.7% | 10 | 13.9% |

| Widowed | 4 | 3.0% | 1 | 1.7% | 3 | 4.2% |

| Separated | 4 | 3.0% | 2 | 3.3% | 2 | 2.8% |

| SCID | ||||||

| Anxiety Disorder | 49 | 37.1% | 20 | 33.3% | 29 | 40.3% |

| Mood Disorder | 36 | 27.3% | 19 | 31.7% | 17 | 23.6% |

| Substance Use (Non-CUD) | 23 | 17.4% | 4 | 6.7% | 19 | 26.4% |

| AUDIT | 8.80 | 8.20 | 9.56 | 8.68 | 7.84 | 7.50 |

| Preferred Marijuana use | ||||||

| Joint | 73 | 55.3% | 28 | 46.7% | 45 | 62.5% |

| Bowl | 14 | 10.6% | 7 | 11.7% | 7 | 9.7% |

| Bong | 8 | 1.5% | 5 | 8.3% | 3 | 4.2 |

| One-Hitter | 2 | 1.5% | 2 | 3.3% | 0 | 0% |

| Blunt | 33 | 25.0% | 17 | 28.3% | 16 | 22.2% |

| Vaporizer | 1 | 0.8% | 1 | 1.7% | 0 | 0% |

| Other | 1 | 0.8% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1.4% |

| Marijuana Usea | 5.92 | 1.62 | 5.93 | 1.67602 | 5.92 | 1.58 |

| Financial Straina | 17.34 | 5.08 | 16.67 | 4.99 | 17.90 | 5.11 |

| Anxiety Sensitivityb | 16.87 | 14.52 | 16.63 | 13.06 | 17.07 | 15.72 |

| Cannabis Problemsc | 26.67 | 6.99 | 25.77 | 5.84 | 27.42 | 7.79 |

| Barriers to Cessationc | 23.05 | 12.90 | 22.92 | 11.97 | 23.17 | 13.70 |

| Self-Efficacy | 56.27 | 17.73 | 58.33 | 17.53 | 54.56 | 17.84 |

Note. Total N=132, Non-current smokers N= 60, Current smokers N=72; Sex: 0 =Female, 1 = Male; SCID= Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders-DSM IV (First et al., 1996) AUDIT= Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (Babor et al. 2001) FSQ = Financial Strain Questionnaire (Pearlin et al., 1981); ASI = Anxiety Sensitivity Index (Taylor et al., 2007); Cannabis Problems= Marijuana Problems Scale (Stephens, Roffman, & Curtin, 2000); Barriers to Cessation= Barriers to Cessation Scale (Macnee & Talsma, 1995); Self-Efficacy for Quitting Cannabis= Self-Efficacy Questionnaire Cannabis (Hogan, 2015)..

2.2. Measures

Demographics Questionnaire.

Participants indicated their sex, race, age, and educational level. Sex and educational level were included as covariates in our model. Cigarette use was assessed via self-report measure “Do you currently smoke cigarettes?”

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders-DSM IV (SCID-IV-TR; First et al., 1996).

The SCID-IV-TR is a semi-structured interview used to assess psychopathology per guidelines established within the DSM-IV (First & Gibbon, 2004). All interviews were conducted by (trained/supervised) graduate-level research assistants or doctoral-level professionals. Twenty percent of cases were randomly selected and checked for interrater reliability. Reliability checks were conducted by trained and supervised post-baccalaureate research assistants or doctoral-level clinical psychology graduate students for diagnostic agreement. No diagnostic disagreements were found.

Financial Strain Questionnaire.

The Financial Strain Questionnaire (FSQ; Pearlin et al., 1981) is a 9-item self-report measure of the participants’ financial conditions. Past work has documented strong psychometric properties for the FSQ, which asks participants to rate the strain of finical situations (i.e., “Do you have enough money to buy the kind of food (you/your family should have?) on 3-point Likert-type scale (1 = Yes, I can afford to 3 = No, I cannot afford). The total score with higher scores indicating more finical strain was included as a covariate in our models. Internal consistency for this measure was strong (α = .91).

Anxiety Sensitivity Index – 3.

The Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3; Taylor et al., 2007) is an 18-item self-report measure of sensitivity to and fear of the potential negative consequences of anxiety-related symptoms and sensations Taylor et al., 2007). Respondents are asked to indicate, on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = very little to 4 = very much), the degree to which they are concerned about these possible negative consequences (range 0–72). The ASI-3, derived in part from the original ASI (Reiss & Mcnally, 1985), has sound psychometric properties, including excellent internal consistency, predictive validity, and reliability among treatment-seeking smokers (Farris et al., 2015), as well as cannabis and other substance users (Raines et al., 2021). Additionally, the factor structure and psychometric properties of AS as a construct is supported across a variety of diverse samples (Cintrón et al., 2005; Sandin et al., 1996). The total ASI-3 score was used in the current study. Internal consistency for this measure was strong (α =.93).

Smoking History Questionnaire.

The Smoking History Questionnaire (Brown et al., 2001) is a 15 item self-report questionnaire used to assess tobacco smoking history and patterns of smoking (e.g. smoking rate, age of onset of initiation). It has been successfully used in previous studies as a measure of smoking history (e.g., Zvolensky et al., 2004). Cigarette user status was used as a moderator variable in our proposed models.

Marijuana Problems Scale.

The Marijuana Problem Scale (MPS; Stephens et al., 2000) is a psychometrically sound, 19 item self-report measure that asks participants to identify areas of their life affected by marijuana use such as social relationships, self-esteem, motivation and productivity, work and finance, physical health, memory impairment, and legal problems in the past 90 days. Participants are asked to rate the statements, such as “problems with your partner” or “legal problems” on a 3-point Likert-type scale (0 = no problem to 2 = a serious problem). The total score with higher scores indicating higher levels of cannabis problems was included as a criterion variable. Internal consistency for this measure was strong (α = .90).

Barriers to Cannabis Cessation Scale.

The Barriers for Cannabis Cessation Scale (BCCS) is a 19 item self-report measure that assesses perceived barriers and is a modified version of the Barriers to Cessation Scale for assessing quitting cigarette smoking (Macnee & Talsma, 1995). The statements are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale (0 = Not a barrier/not applicable to 3 = Large barrier). The total score, with higher scores indicative of more perceived barriers, was included as a criterion variable. The BCCS has been used successfully in previous work relating to mental health and perceived cessation barriers (Manning et al., 2018). Internal consistency for this measure was strong (α = .92).

Self-efficacy for Quitting Cannabis.

The Smoking Self-Efficacy Questionnaire for quitting cannabis (SEQ-C) is a modified version of the Smoking Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985) focused on cannabis. The SEQ-C is a 19-item questionnaire that asks participants to rate how certain they are that they could using cannabis in high risk (i.e., tempting) situations. The statements are rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = completely unsure to 7 = completely sure). The total score is included as a criterion variable in our models. Internal consistency for this measure was strong (α = .90).

Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence.

The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Heatherton et al., 1991) is a 6-item questionnaire that assesses tobacco dependence. The FTND total scores range from 0 to 10, is calculated by summing the values of the six items, with higher scores indicating higher levels of nicotine dependence. Internal consistency for this measure was moderate (α = .68).

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor et al. 2001) is a 10-item questionnaire that assess alcohol frequency and identifying participants with alcohol use disorders. The AUDIT total score is calculated by summing the values of the 10 items, with higher scores indicating higher levels of alcohol dependence. Internal consistency for this measure was strong (α = .91).

2.3. Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25. First, descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations among study variables were examined. Second, three separate hierarchical regression analyses were conducted (criterion variables: cannabis use problems, perceived barriers for cannabis cessation, and self-efficacy for quitting cannabis use). Covariates were entered in the first step of each model and included sex (Buu et al., 2015), education level (Degenhardt & Hall, 2001), average cannabis use days per week (Ramesh, Haney, & Cooper, 2013), and financial strain (Gollust, Schroeder, & Warner, 2008). AS and cigarette user status were then simultaneously entered in the second step of each model. Finally, the interaction of AS and cigarette smoking status (product of predictor and moderator variables) was added in the third step. Planned post-hoc simple slope analyses were conducted to probe interaction effects using the PROCESS macro (Hayes & Preacher, 2013) to examine associations between AS and the dependent variables across smoking status (coded: 0 = cigarette non-users, 1 = cigarette users).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analyses

Zero-order correlations among all study variables are presented in Table 2. AS was positively related to cannabis use problems (r = .31, p < .001), perceived barriers for cannabis cessation (r = .28, p < .001) and self-efficacy for quitting cannabis use (r = .24, p < .001). AS did not significantly differ (t(130) = 1.6, p = .21) between cigarette smokers (M = 17.1, SD = 15.7) and non-smokers (M = 16.6, SD = 13.1). Cigarette user status was not significantly correlated with cannabis use problems (r = .12, p = .18), perceived barriers for cannabis cessation (r = .01, p = .91) or self-efficacy for quitting cannabis use (r = −.11, p = .22).

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics.

| Mean/ n | SD / % | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sexa | 94 | 71.21% | -- | ||||||||

| 2. Education a | 3.14 | 1.04 | .09 | -- | |||||||

| 3. Marijuana Usea | 5.92 | 1.62 | −.15 | −.11 | -- | ||||||

| 4. Financial Straina | 17.34 | 5.08 | .11 | .23** | −.06 | -- | |||||

| 5. Anxiety Sensitivityb | 16.87 | 14.52 | −.06 | .02 | .16 | .19* | -- | ||||

| 6. Smoking Statusd | 72 | 54.55% | .13 | .02 | −.01 | .12 | .02 | -- | |||

| 7. Cannabis Problemsc | 26.67 | 6.99 | .08 | .03 | .02 | .28** | .31** | .12 | -- | ||

| 8. Barriers to Cessationc | 23.05 | 12.90 | −.17 | −.04 | .16 | .18* | .28** | .01 | .45** | -- | |

| 9. Self-Efficacy | 56.27 | 17.73 | −.06 | −.05 | .06 | .06 | .24** | −.11 | .23** | .10 | -- |

Note. N = 132;.

p < .05,

p<.01.,

p<.001.

Covariate.

Predictor.

Outcome.

Moderator; Sex: 0 = Female, 1 = Male; Educational Level: 1 = Graduate school, 2 = College Graduate, 3 = Partial College, 4 = High School Graduate, 5 = Partial High School, 6 = Junior High School, 7 = Less than Seven Years of School; Marijuana Use (days per week); FSQ = Financial Strain Questionnaire (Pearlin et al., 1981); ASI = Anxiety Sensitivity Index (Taylor et al., 2007); Smoking Status: 0 = non-current smokers, 1 = current smoker; Cannabis Problems= Marijuana Problems Scale (Stephens, Roffman, & Curtin, 2000); Barriers to Cessation= Barriers to Cessation Scale (Macnee & Talsma, 1995); Self-Efficacy for Quitting Cannabis= Self-Efficacy Questionnaire Cannabis (Hogan, 2015).

3.2. Primary Analyses

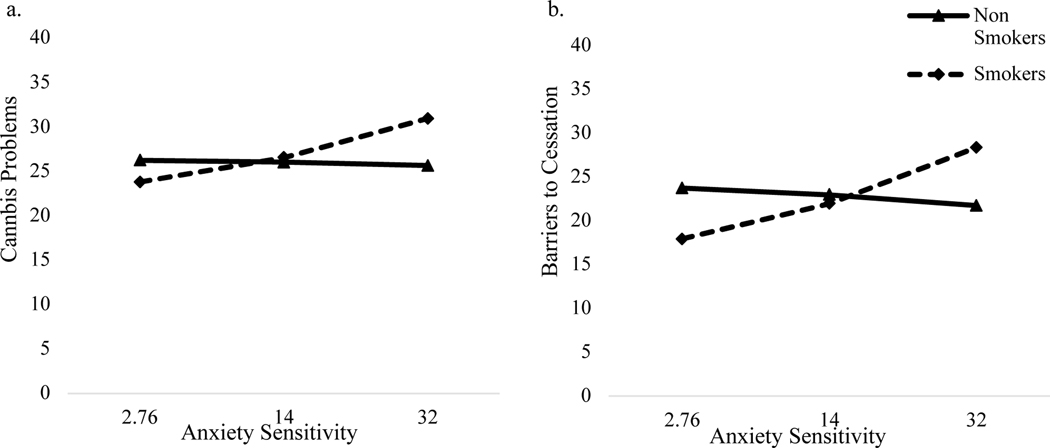

Regression results are presented in Table 3.1 For cannabis use problems, Step 1 of the model accounted for a statistically significant proportion of variance (R2 = .09, F[4, 127] = 3.00, p = .02), with financial strain as a statistically significant predictor. The addition of AS and cigarette user status to the regression model accounted for greater variance in cannabis use problems (ΔR2 = .08, p = .004), with AS as a statistically significant predictor. Adding the interaction effect between AS and cigarette user status accounted for statistically significantly more variance in cannabis use problems (ΔR2 = .06, p = .002). The form of the interaction effect indicated that AS was statistically significantly and positively related to cannabis use problems among cigarette smokers (b = .22, SE = .05, p < .001), but not among cigarette non-users (b = −.03, SE = .07, p = .62; see Figure 1a).

Table 3.

Regression Models

| Cannabis Use Problems | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| b | SE | t | p | sr 2 | ΔR2 | |

| Step 1 | .09* | |||||

| Sex | .90 | 1.33 | .68 | .50 | .06 | |

| Education | −.28 | .59 | −.47 | .64 | −.04 | |

| Cannabis use days | .18 | .37 | .49 | .63 | .04 | |

| Financial Strain | .40 | .12 | 3.30 | .001 | .28 | |

| Step 2 | .08* | |||||

| Anxiety Sensitivity | .13 | .04 | 3.24 | .002 | .27 | |

| Smoking Status | 1.11 | 1.16 | 0.96 | 0.34 | .08 | |

| Step 3 | .06* | |||||

| Anxiety Sensitivity*Smoking status | .26 | .08 | 3.16 | .002 | .25 | |

| Barriers for Cannabis Cessation | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| b | SE | t | p | sr 2 | ΔR2 | |

|

| ||||||

| Step 1 | .09* | |||||

| Sex | −4.75 | 2.44 | −1.95 | .05 | −.17 | |

| Education | −.75 | 1.08 | −.70 | .49 | −.06 | |

| Cannabis use days | 1.11 | .69 | 1.62 | .11 | .14 | |

| Financial Strain | .55 | .22 | 2.5 | .014 | .21 | |

| Step 2 | .04* | |||||

| Anxiety Sensitivity | .19 | .08 | 2.53 | .01 | .21 | |

| Smoking Status | .18 | 2.18 | .09 | .93 | .007 | |

| Step 3 | .05* | |||||

| Anxiety Sensitivity*Smoking status | .43 | .15 | 2.77 | .006 | .22 | |

| Self-Efficacy for Quitting Cannabis | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| b | SE | t | p | sr 2 | ΔR2 | |

|

| ||||||

| Step 1 | .02 | |||||

| Sex | −2.38 | 3.50 | −.68 | .50 | −.06 | |

| Education | −.99 | 1.55 | −.64 | .52 | −.06 | |

| Cannabis use days | .51 | .98 | .52 | .61 | .05 | |

| Financial Strain | .29 | .32 | .92 | .36 | .08 | |

| Step 2 | .06* | |||||

| Anxiety Sensitivity | .28 | .11 | 2.58 | .011 | .22 | |

| Smoking status | −3.90 | 3.10 | −1.26 | .21 | −.11 | |

| Step 3 | .02 | |||||

| Anxiety Sensitivity*Smoking status | .37 | .22 | 1.64 | .10 | .14 | |

Note. N = 132;

p < .05,

p<.01.,

p<.001.

Figure 1.

Interaction of Anxiety Sensitivity and Smoking status on (a.) Connabis Problems, (b.) Barriers to Cessation.

For perceived barriers for cannabis cessation, Step 1 of the model accounted for a statistically significant amount of variance (R2 = .09, F[4, 127] = 3.22, p = .02). The addition of AS and cigarette user status to the regression model accounted for greater variance in perceived barriers for cannabis cessation (ΔR2 = .04, p = .04), with AS as a statistically significant predictor. Adding the interaction effect between AS and cigarette user status accounted for statistically significantly more variance in perceived barriers for cannabis cessation (ΔR2 = .05, p = .006). Additionally, a statistically significant interaction effect between cigarette user status and AS was evident for perceived barriers for cannabis cessation (b = .43, SE = .15, p = .006). The form of this interaction effect indicated that AS was positively related to perceived barriers for cannabis cessation among cigarette smokers (b = .35, SE = .09, p = .003), but not among cigarette non-users (b = −.08, SE = .12, p = .53; see Figure 1b).

For self-efficacy for remaining abstinent from cannabis, the model was not statistically significant (R2 = .15, F[4, 127] = .47, p =.76). The addition of AS and cigarette user status to the regression model accounted for greater variance in self-efficacy to quit cannabis (ΔR2 = .06, p =.02), with AS as a significant predictor. There was no statistically significant interaction (b = .37, SE = .22, p = .10).

4. Discussion

The present study tested the moderating effect of cigarette use status on AS in terms of cannabis cessation-related processes among adults with CUD. Findings indicated that AS was significantly and positively related to cannabis use problems and perceived barriers for cannabis cessation among current cigarette smokers, but unrelated to these variables among non-cigarette users. These effects were evident after accounting for theoretically and empirically relevant covariates of sex (Buu et al., 2015), education level (Degenhardt & Hall, 2001), average cannabis use days per week (Ramesh, Haney, & Cooper, 2013), and financial strain (Gollust, Schroeder, & Warner, 2008).

The present findings suggest that higher levels of AS relate to more cannabis use problems and perceived barriers for cannabis cessation among current cigarette smokers. For cigarette non-users, however, AS does not similarly affect these processes. This pattern of findings may be possibly explained by differences in cannabis use motives between cannabis-only users and persons who also use cigarettes. Research indicates that coping-oriented motives for substance use covaries with substance-related problems and symptoms of dependence (e.g., Buckner et al., 2006; Bujarski et al., 2012; Foster et al., 2016). Moreover, mental health difficulties are more prevalent among dual users in comparison to cannabis-only users (Hindocha et al., 2021). Although speculative, cannabis-only users may be less prone to using cannabis as a means of reducing emotional distress attributable to anxious arousal or somatic symptoms. Indeed, compared to regular cannabis users, cigarette smokers may be more apt to use cannabis to help manage aversive anxiety-related physical sensations (e.g., Buckner et al, 2011). Futher research is needed to understand how use motives effect the studied relations.

Counter to expectation, cigarette user status did not moderate the relation between AS on self-efficacy for remaining abstinent from cannabis. It is important to note the association between AS and self-efficacy to quit cannabis suggested that those with higher AS tend to report higher self-efficacy to quit. This finding contrasts with past research on cigarette smokers, which typically finds an inverse relationship between AS and self-confidence in one’s ability to maintain abstinence (e.g., Zvolensky et al., 2006). Thus, based on the available evidence, it appears that AS may differentially relate to cessation-related self-efficacy between cigarette-only users and cannabis users regardless of cigarette user status. Considering the preliminary nature of these findings, further research is warranted to determine the replicability of these effects and to examine potential explanatory mechanisms of this observed association.

Clinically, the current study has several possible implications. First, it may be important to assess and monitor tobacco use among cannabis users seeking CUD/cessation treatment (Hindocha et al., 2021). Doing so could be beneficial for identifying patients at risk of poor CUD treatment response, and in turn, clinicians may be better equipped to tailor intervention efforts (e.g., greater density of relapse prevention skills). Second, research indicates that cognitive-behavioral approaches are effective in reducing AS among cigarette using populations (e.g., Garey et al., 2021; Schmidt et al., 2016; Smits et al., 2016). Thus, considering the present findings, tobacco users seeking treatment for CUD may find programs that focus on AS reduction to be particularly beneficial.

Several limitations should be noted. First, data were cross-sectional, which limits the ability to interpret causation or directionality of the effects. Future research could expand this line of work by using longitudinal or experimental designs and explicate the nature of the observed relationships further. Second, this study focused on current cigarette users, without consideration of lifetime use. Future research would benefit from documenting lifetime use status and investigating the effects of among specific subgroups (e.g., different histories of lifetime duration of use and co-use). Third, this study relied on self-report measures. Future research would therefore benefit from the implementation of multimethod measurement protocols. Fourth, the present study focused on participants who have attempted to quit cannabis in the past year. Future research could focus on participants who are not seeking treatment to determine if the observed relationships generalize to other segments of the cannabis using population. Fifth, the study relied on responses specifically about the use of combustible cigarettes and did not include information about other ways of consuming nicotine and cannabis. Future research should incorporate other methods of consumption to determine if the observed relationships generalizable to e-cigarettes, vaping, eating, or other popular methods of using these substances. Finally, the current study did not account for quantity of cannabis use or the potential use of other substances beyond tobacco. It may therefore be important for future research to document the quantity of cannabis use and integrate other forms of substance use in the tested models.

Overall, the present findings suggest that AS and cigarette use status interplay in terms of certain cannabis-related quit processes among adults with CUD. Thus, although AS serves as a general risk factor for cannabis use problems and cessation difficulties among those with CUD, these effects appear to be significantly more pronounced among cigarette users.

Author Note:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to the University of Houston under Award Number U54MD015946. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: none

Overall pattern of findings remained consistent when additional substance use diagnosis was included as a covariate at Step 1.

References

- Agrawal A, Budney AJ, & Lynskey MT (2012). The co-occurring use and misuse of cannabis and tobacco: A review. Addiction, 107(7), 1221–1233. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03837.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbar SA, Tomko RL, Salazar CA, Squeglia LM, & McClure EA (2019). Tobacco and cannabis co-use and interrelatedness among adults. Addictive Behaviors, 90, 354–361. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldington S, Harwood M, Cox B, Weatherall M, Beckert L, Hansell A, Pritchard A, Robinson G, & Beasley R. (2008). Cannabis use and risk of lung cancer: A case–control study. European Respiratory Journal, 31(2), 280–286. 10.1183/09031936.00065707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AL, Hides L, & Lubman DI (2010). Treatment of cannabis use among people with psychotic or depressive disorders: A systematic review. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(3), 247–254. 10.4088/JCP.09r05119gry [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, & Monteiro MG (2001). The alcohol use disorders identification test (pp. 1–37). Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Hasin DS, Wall MM, Flórez-Salamanca L, Hoertel N, Wang S, Kerridge BT, & Olfson M. (2016). Cannabis Use and Risk of Psychiatric Disorders: Prospective Evidence From a US National Longitudinal Study. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(4), 388–395. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Leen-Feldner EW, Feldner MT & Yartz AR (2005). Marijuana use among daily tobacco smokers: Relationship to anxiety-related factors. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 27, 279–289. 10.1007/s10862-005-2408-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Marshall EC, & Bernstein A. (2007). Incremental validity of anxiety sensitivity in relation to Marijuana withdrawal symptoms. Addictive Behaviors, 32(9), 1843–1851. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez CW, & Ramsey SE (2001). Anxiety sensitivity: Relationship to negative affect smoking and smoking cessation in smokers with past major depressive disorder. Addictive Behaviors, 26(6), 887–899. 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00241-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Bobadilla L, & Taylor J. (2006). Social anxiety and problematic cannabis use: Evaluating the moderating role of stress reactivity and perceived coping. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(7), 1007–1015. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ, Businelle MS, & Gallagher MW (2018). Direct and indirect effects of false safety behaviors on cannabis use and related problems. The American journal on addictions, 27(1), 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ, Farris SG, & Hogan J. (2014). Social Anxiety and Coping Motives for Cannabis Use: The Impact of Experiential Avoidance. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors : Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 28(2), 568–574. 10.1037/a0034545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ, Smits JAJ, Norton PJ, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, & Schmidt NB (2011). Anxiety sensitivity and marijuana use: An analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Depression & Anxiety (1091–4269), 28(5), 420–426. 10.1002/da.20816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujarski SJ, Norberg MM, & Copeland J. (2012). The association between distress tolerance and cannabis use-related problems: The mediating and moderating roles of coping motives and gender. Addictive Behaviors, 37(10), 1181–1184. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buu A, Dabrowska A, Heinze JE, Hsieh HF, & Zimmerman MA (2015). Gender differences in the developmental trajectories of multiple substance use and the effect of nicotine and marijuana use on heavy drinking in a high-risk sample. Addictive behaviors, 50, 6–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdá M, Wall M, Keyes KM, Galea S, & Hasin D. (2012). Medical marijuana laws in 50 states: Investigating the relationship between state legalization of medical marijuana and marijuana use, abuse and dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 120(1), 22–27. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cintrón JA, Carter MM, Suchday S, Sbrocco T, & Gray J. (2005). Factor structure and construct validity of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index among island Puerto Ricans. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 19(1), 51–68. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Han B, Jones CM, Blanco C, & Hughes A. (2016). Marijuana use and use disorders in adults in the USA, 2002–14: Analysis of annual cross-sectional surveys. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(10), 954–964. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30208-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crippa JA, Zuardi AW, Martín‐Santos R, Bhattacharyya S, Atakan Z, McGuire P, & Fusar‐Poli P. (2009). Cannabis and anxiety: A critical review of the evidence. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 24(7), 515–523. 10.1002/hup.1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, & Hall AW (2001). The relationship between tobacco use, substance-use disorders and mental health: results from the National Survey of Mental Health and Well-being. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 3(3), 225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris SG, DiBello AM, Allan NP, Hogan J, Schmidt NB, & Zvolensky MJ (2015). Evaluation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 among treatment-seeking smokers. Psychological Assessment, 27(3), 1123–1128. 10.1037/pas0000112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, & Gibbon M. (2004). The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II). In Hilsenroth MJ, Segal DL, Hilsenroth MJ (Ed), & Segal DL (Ed) (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment, Vol. 2: Personality assessment. (2004–12821-011; pp. 134–143). John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Foster DW, Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, & Zvolensky MJ (2016). Multisubstance Use Among Treatment-Seeking Smokers: Synergistic Effects of Coping Motives for Cannabis and Alcohol Use and Social Anxiety/Depressive Symptoms. Substance Use & Misuse, 51(2), 165–178. 10.3109/10826084.2015.1082596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garey L, Smit T, Neighbors C, Gallagher MW, & Zvolensky MJ (2021). Personalized Feedback for Smoking and Anxiety Sensitivity: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Substance Use & Misuse, 56(7), 929–940. 10.1080/10826084.2021.1900255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollust SE, Schroeder SA, & Warner KE (2008). Helping smokers quit: understanding the barriers to utilization of smoking cessation services. The Milbank Quarterly, 86(4), 601–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillot CR, Blumenthal H, Zvolensky MJ, & Schmidt NB (2018). Anxiety sensitivity components in relation to alcohol and cannabis use, motives, and problems in treatment-seeking cigarette smokers. Addictive behaviors, 82, 166–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn RL, Jackson KM, Borsari B, & Metrik J. (2018). Negative urgency partially accounts for the relationship between major depressive disorder and marijuana problems. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul, 5, 10. 10.1186/s40479-018-0087-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS (2018). US epidemiology of cannabis use and associated problems. Neuropsychopharmacology, 43(1), 195–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2013–21121-000). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, & Fagerstrom KO (1991). The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British journal of addiction, 86(9), 1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindocha C, Brose LS, Walsh H, & Cheeseman H. (2021). Cannabis use and co-use in tobacco smokers and non-smokers: Prevalence and associations with mental health in a cross-sectional, nationally representative sample of adults in Great Britain, 2020. Addiction, 116(8), 2209–2219. 10.1111/add.15381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan JB (2015). Distress Intolerance and Cannabis Use: An Initial Empirical Investigation.

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2017). Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2016: Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. In Institute for Social Research. Institute for Social Research. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED578534 [Google Scholar]

- Keyhani S, Steigerwald S, Ishida J, Vali M, Cerdá M, Hasin D, Dollinger C, Yoo SR, & Cohen BE (2018). Risks and Benefits of Marijuana Use. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(5), 282–290. 10.7326/M18-0810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp AA, Allan NP, Cloutier R, Blumenthal H, Moradi S, Budney AJ, & Lord SE (2021). Effects of anxiety sensitivity on cannabis, alcohol, and nicotine use among adolescents: Evaluating pathways through anxiety, withdrawal symptoms, and coping motives. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 44(2), 187–201. 10.1007/s10865-020-00182-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev-Ran S, Roerecke M, Foll BL, George TP, McKenzie K, & Rehm J. (2014). The association between cannabis use and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Medicine, 44(4), 797–810. 10.1017/S0033291713001438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DC, Schlienz NJ, Peters EN, Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Strain EC, & Vandrey R. (2019). Systematic review of outcome domains and measures used in psychosocial and pharmacological treatment trials for cannabis use disorder. Drug and alcohol dependence, 194, 500–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees R, Hines LA, D’Souza DC, Stothart G, Di Forti M, Hoch E, & Freeman TP (2021). Psychosocial and pharmacological treatments for cannabis use disorder and mental health comorbidities: a narrative review. Psychological Medicine, 51(3), 353–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loflin Mallory JE, Kiluk Brian D., Huestis Marilyn A., Aklin Will M., Budney Alan J., Carroll Kathleen M., D’Souza Deepak Cyril et al. “The state of clinical outcome assessments for cannabis use disorder clinical trials: A review and research agenda.” Drug and alcohol dependence 212 (2020): 107993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macnee CL, & Talsma A. (1995). Development and testing of the barriers to cessation scale. Nursing Research, 44(4), 214–219. 10.1097/00006199-199507000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning K, Paulus DJ, Hogan JBD, Buckner JD, Farris SG, & Zvolensky MJ (2018). Negative affectivity as a mechanism underlying perceived distress tolerance and cannabis use problems, barriers to cessation, and self-efficacy for quitting among urban cannabis users. Addictive Behaviors, 78, 216–222. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, & Donovan DM (Eds.). (2005). Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. Guilford press. [Google Scholar]

- McClure EA, Baker NL, Sonne SC, Ghitza UE, Tomko RL, Montgomery L, Babalonis S, Terry GE, & Gray KM (2018). Tobacco use during cannabis cessation: Use patterns and impact on abstinence in a National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 192, 59–66. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus DJ, Manning K, Hogan JBD, & Zvolensky MJ (2017). The role of anxiety sensitivity in the relation between anxious arousal and cannabis and alcohol use problems among low-income inner city racial/ethnic minorities. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 48, 87–94. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus DJ, Talkovsky AM, Heggeness LF, & Norton PJ (2015). Beyond Negative Affectivity: A Hierarchical Model of Global and Transdiagnostic Vulnerabilities for Emotional Disorders. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 44(5), 389–405. 10.1080/16506073.2015.1017529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, & Mullan JT (1981). The Stress Process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22(4), 337–356. 10.2307/2136676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters EN, Schwartz RP, Wang S, O’Grady KE, & Blanco C. (2014). Psychiatric, psychosocial, and physical health correlates of co-occurring cannabis use disorders and nicotine dependence. Drug and alcohol dependence, 134, 228–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh D, Haney M, & Cooper ZD (2013). Marijuana’s dose-dependent effects in daily marijuana smokers. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology, 21(4), 287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S, & McNally R. (1985). Expectancy model of fear.. Reiss S, Bootzin RR (Eds). Theoretical issues in behavior therapy inside. In: San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sandin B, Chorot P, & McNally RJ (1996). Validation of the Spanish version of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index in a clinical sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(3), 283–290. 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00074-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2019. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19–5068, NSDUH Series H-54).

- Schmidt NB, Raines AM, Allan NP, & Zvolensky MJ (2016). Anxiety sensitivity risk reduction in smokers: A randomized control trial examining effects on panic. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 138–146. 10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman BJ, & McRae-Clark AL (2016). Treatment of Cannabis Use Disorder: Current Science and Future Outlook. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy, 36(5), 511–535. 10.1002/phar.1747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits JAJ, Zvolensky MJ, Davis ML, Rosenfield D, Marcus BH, Church TS, Powers MB, Frierson GM, Otto MW, Hopkins LB, Brown RA, & Baird SO (2016). The Efficacy of Vigorous-Intensity Exercise as an Aid to Smoking Cessation in Adults with High Anxiety Sensitivity: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(3), 354–364. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Roffman RA, & Curtin L. (2000). Comparison of extended versus brief treatments for marijuana use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 898–908. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Carron L, & Pihl RO (1993). Reasons for licit drug use: Relationships to anxiety sensitivity levels. 1+ 11 National Library, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DR, Poulton R, Moffitt TE, Ramankutty P, & Sears MR (2000). The respiratory effects of cannabis dependence in young adults. Addiction, 95(11), 1669–1677. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951116697.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Zvolensky MJ, Cox BJ, Deacon B, Heimberg RG, Ledley DR, Abramowitz JS, Holaway RM, Sandin B, Stewart SH, Coles M, Eng W, Daly ES, Arrindell WA, Bouvard M, & Cardenas SJ (2007). Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: Development and initial validation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3. Psychological Assessment, 19(2), 176–188. 10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thake J, & Davis CG (2011). Assessing problematic cannabis use. Addiction Research & Theory, 19(5), 448–458. [Google Scholar]

- Vandrey RG, Budney AJ, Hughes JR, & Liguori A. (2008). A within-subject comparison of withdrawal symptoms during abstinence from cannabis, tobacco, and both substances. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 92(1), 48–54. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Pacek LR, Wall MM, Zvolensky MJ, Copeland J, Galea S, ... & Goodwin RD (2018). Trends in cannabis use disorder by cigarette smoking status in the United States, 2002–2016. Drug and alcohol dependence, 191, 45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Bonn-Miller MO, Feldner MT, Leen-Feldner E, McLeish AC, & Gregor K. (2006). Anxiety sensitivity: Concurrent associations with negative affect smoking motives and abstinence self-confidence among young adult smokers. Addictive Behaviors, 31(3), 429–439. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Farris SG, Leyro TM, Langdon KJ, Bernstein A, & Bonn-Miller M. (2019). Cannabis: An overview of the empirical literature (pp. 339–352). In Johnson B. (Ed.), Addiction medicine: Science and practice (Vol. 2). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Feldner MT, Leen-Feldner E, Bonn-Miller MO, McLeish AC, & Gregor K. (2004). Evaluating the Role of Anxiety Sensitivity in Smoking Outcome Expectancies Among Regular Smokers. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28(4), 473–486. 10.1023/B:COTR.0000045559.73958.89 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Kauffman BY, Garey L, Viana AG, & Matoska CT (in press). Interoceptive anxiety-related processes: Importance for understanding COVID-19 and future pandemic mental health and addictive behaviors and their comorbidity. Behaviour Research and Therapy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zvolensky MJ, Rogers AH, Manning K, Hogan JBD, Paulus DJ, Buckner JD, Mayorga NA, Hallford G, & Schmidt NB (2018). Anxiety sensitivity and cannabis use problems, perceived barriers for quitting, and fear of quitting. Psychiatry Research, 263, 115–120. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]