Abstract

Background:

Interventions that target anxiety/depressive symptoms in the context of smoking treatment have shown promise irrespective of psychiatric diagnosis. Yet, these tailored treatments are largely absent for persons who smoke and are living with HIV (SLWH).

Objective:

To evaluate a novel, smoking cessation intervention that addresses anxiety/depression and HIV-related health (QUIT) against a time-matched control (TMC) and a standard of care (SOC) condition.

Methods:

SLWH (N = 180) will be recruited from 3 medical clinics in Boston, MA, and Houston, TX. The trial will consist of a baseline assessment, a 10-week intervention/assessment period, and follow-up assessments, accounting for a total study duration of approximately 8 months. All participants will complete a baseline visit and a pre-randomization standardized psychoeducation visit, and will then be randomized to one of three conditions: QUIT, TMC, or SOC. QUIT and TMC will consist of nine 60-minute, cognitive behavioral therapy-based, individual weekly counseling sessions using standard smoking cessation counseling; additionally, QUIT will target anxiety and depressive symptoms by addressing underlying mechanisms related to mood and quit difficulty. SOC participants will complete weekly self-report surveys for nine weeks. All participants will be encouraged to quit at Session 7 and will be offered nicotine replacement therapy to help.

Conclusions:

QUIT is designed to improve smoking cessation in SLWH by addressing anxiety and depression and HIV-related health issues. If successful, the QUIT intervention would be ready for implementation and dissemination into “real-world” behavioral health and social service settings consistent with the four objectives outlined in NIDA’s Strategic Plan.

Keywords: Smoking Cessation, HIV, Anxiety, Depression, Psychosocial Treatment, Efficacy/Effectiveness

1. Introduction

People living with HIV (PLWH) smoke at rates 2–3 times higher than people without HIV, with smoking estimates of 33.6%−74% among PLWH compared to 16.8–18% among the general population.1,2 PLWH who smoke (SLWH) lose more life-years than PLWH who do not smoke and people who smoke who do not have HIV.3–5 Indeed, a recent cohort study found that life-years lost among SLWH (12.3) was nearly quadruple that of HIV-negative individuals who smoked (3.6) and more than double PLWH who did not smoke (5.1).3 Despite the risk for reduced life expectancy, SLWH are less willing to quit than individuals who smoke without HIV.6 Subsequently, smoking cessation trials that target SLWH have yielded mixed findings.7–15 Limited integration of factors known to interfere with smoking cessation, such as anxiety and depressive symptoms,16,17 within treatments for SLWH may contribute to quit difficulty and mixed findings.

Research suggests that anxiety and depression are major impediments to smoking cessation,16,17 which is particularly relevant to SLWH given the population’s elevated rates.18 Indeed, SLWH are 66% more likely to report elevated anxiety than PLWH who do not smoke.19 Although therapeutic smoking interventions that target anxiety/depressive symptoms have shown promise in the general population,20 such treatments, apart from ours described below, are absent for SLWH. This neglect is unfortunate as depression and anxiety are common among those who smoke,21,22 are common psychiatric disorders,23 and share common vulnerability processes implicated in the etiology of smoking.24

To comprehensively address anxiety/depressive symptoms in the context of smoking cessation among SLWH, integrated cessation treatments that address vulnerabilities across anxiety/depressive disorders are needed.25 Scientific efforts have identified anxiety sensitivity, distress intolerance, and anhedonia as three of the strongest and most consistent emotion constructs relevant to anxiety/depression and smoking.24 These malleable mechanisms can be targeted in treatment24 and represent underlying anxiety/depression-smoking mechanisms that may be relevant to smoking cessation outcomes among SLWH. To test this theory, we completed a pilot study to initially test an intervention (QUIT) that integrated standard cognitive behavioral therapy for smoking cessation with treatment that targets these three mechanisms. 25,26 We used a transdiagnostic approach to treatment development, which relies on engaging mechanisms implicated in the onset and maintenance of related behavioral health conditions. Compared to an enhanced standard-of-care (E-SOC), smoking abstinence was significantly higher in QUIT at end-of-treatment (EOT; QUIT=59%, E-SOC=9%) and 6-month follow-up (6MFU; QUIT=46%, E-SOC=5%).26 Additionally, anxiety/depressive symptom severity scales showed lower symptom severity among participants in QUIT at EOT and 6MFU,27 providing evidence that QUIT can successfully increase smoking abstinence and decrease anxiety/depression symptomology at EOT through a 6MFU among SLWH.

The primary aim of the present study is to expand our previous findings by testing the effects of QUIT against a time-matched smoking cessation control (TMC) and SOC in a larger sample of SLWH. Our primary outcome will be smoking cessation. We also will examine putative mechanisms (e.g., anxiety sensitivity, distress intolerance, and anhedonia) and a moderator (e.g., sex) of intervention effects. Finally, we will compare the cost-effectiveness of QUIT to SOC.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design

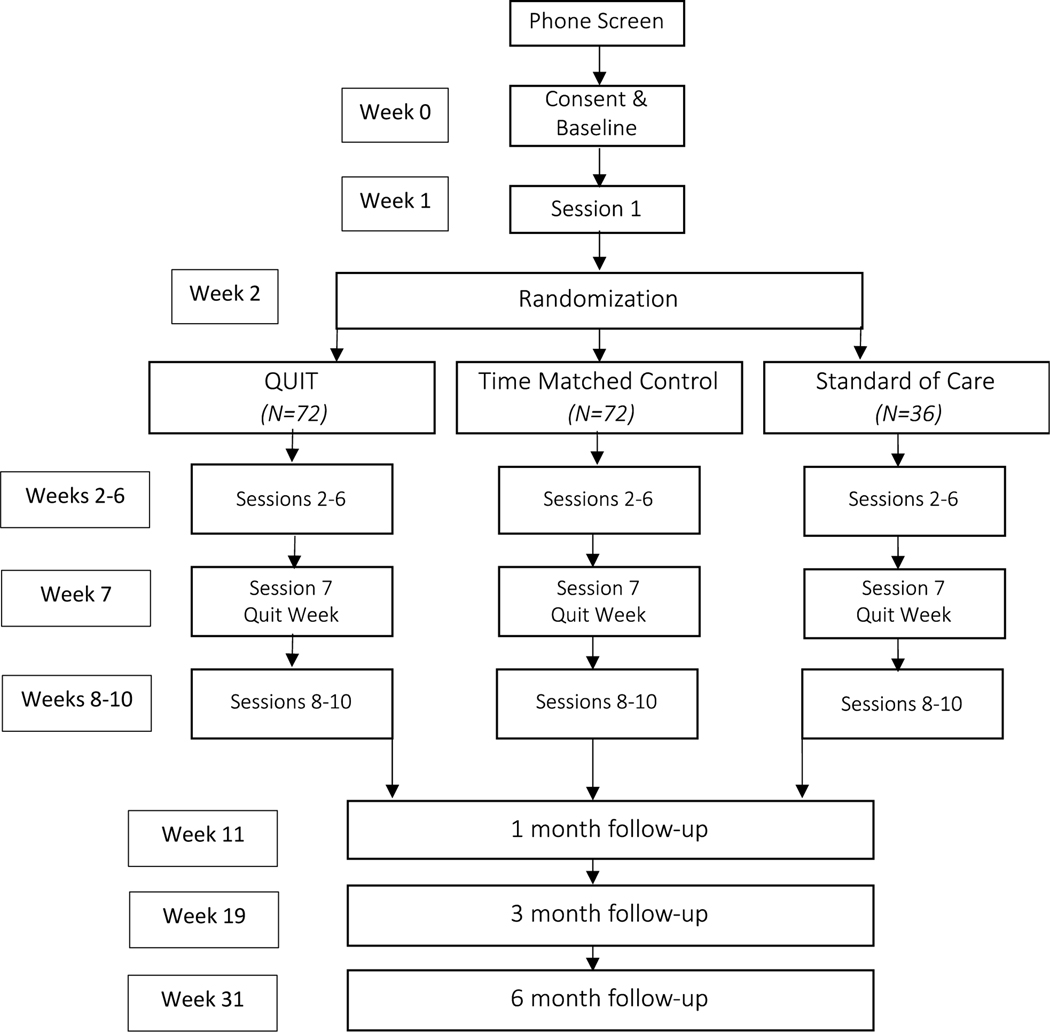

Adults who smoke and are living with HIV (N = 180) will be recruited and enrolled from three medical clinics (two in Boston, MA and one in Houston, TX) to participate in a trial on the effects of a novel smoking cessation treatment. Participants will attend a baseline assessment consisting of self-report questionnaires, clinician-administered assessments, and abstraction of medical record data related to HIV disease progression. Post-baseline, participants will attend a pre-randomization psychoeducation session (i.e., treatment session 1) on health and social consequences associated with smoking, benefits of quitting smoking, nicotine withdrawal, and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). At the beginning of session 2 participants will be randomly assigned to one of three conditions: (1) smoking cessation treatment involving an integrated CBT-based, transdiagnostic approach to treat anxiety, depression, and nicotine dependence concurrently (QUIT); (2) standard smoking treatment (time matched control [TMC]); or (3) smoking status assessment (standard of care [SOC]). QUIT and TMC will consist of nine 60-minute treatment sessions; SOC will consist of nine assessment-only appointments. Each condition will include five pre-quit sessions and four post-quit sessions with quit occurring at session 7, for a total intervention period of 10 weeks (including the pre-randomization treatment session 1). Follow-up will be scheduled for 1-, 3-, and 6-months post-quit week (i.e., post-session 7). Participants in all arms will be offered long-acting NRT at no cost. See Figure 1 for study diagram.

Figure 1.

Participant Flowchart

2.2. Specific Aims and Hypotheses

We will employ a hybrid efficacy/effectiveness randomized controlled trial design to compare the effects of QUIT to TMC and SOC on smoking cessation, and depression and anxiety symptoms, at 1-month and 6-month follow-up. We hypothesize that (1a) 7-day point prevalence abstinence (PPA) will be higher, at 1-month and 6-month follow-up (examined as separate endpoints), for those in the QUIT condition than for those in the TMC and SOC condition. We hypothesize that (1b) greater reductions in depression and anxiety symptoms, at both 1-month and 6-month follow-up (examined as separate endpoints), will be reported by those in the QUIT condition relative to those in the TMC and SOC conditions. Our primary outcome is PPA at 6-month follow-up.

To examine potential (2a) mechanisms of action at 1-month follow-up and (2b) moderators of treatment outcome at 1-month and 6-month follow-up. In testing the putative mechanisms of action, we hypothesize that depression and anxiety symptoms will mediate the effects of the intervention on abstinence. Additionally, we will explore the role of transdiagnostic factors (i.e., anxiety sensitivity, distress intolerance, and anhedonia) as mechanisms underlying intervention effects on abstinence. If any of these factors (depression, anxiety, anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, and/or anhedonia) are highly correlated, they will be combined for these mediation analyses. To determine possible moderators, we will test whether abstinence, and/or treatment effects, vary as a function of sex. Informed by our previous work among adults who smoke without HIV28, anxiety sensitivity also will be evaluated as a potential moderator in exploratory analyses.

To estimate the cost-effectiveness of QUIT. As small improvements in cessation may not be justified if they require substantially greater cost, we will compare QUIT to SOC on cost-effectiveness (incremental cost per cessation and quality-adjusted life years saved). The SOC control condition was selected as the most appropriate comparison condition because TMC is not a strategy that would be used outside the research setting.

2.3. Participants

Participants will include 180 adults who smoke and are living with HIV. Participants will need to meet the following eligibility criteria: (1) HIV-infected; (2) aged 18 – 79 years old; (3) smokes an average of at least 5 cigarettes in the past week or weekend; (4) a motivation to quit smoking of at least a 5 on a 10- point scale or a recent (past year) quit attempt lasting at least 24 hours; and (5) ability to provide informed consent. Participants will not be required to meet diagnostic criteria for anxiety or mood disorders nor are clinically significant elevations in anxiety or depression symptoms inclusion criteria. This approach is consistent with methodology in our pilot RCT (in which no anxiety/depression inclusion criteria were specified) and will ensure that all SLWH will potentially be able to participate and increase confidence that the observed outcomes will generalize more broadly. To reduce the risk of adverse events, we will employ the following exclusion criteria: (1) current interfering, untreated, or unstable major mental health condition (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or psychosis); (2) current use of any pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy for smoking cessation; (3) cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in the past year; (4) use of other tobacco products (i.e., electronic cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco) more than three times per week; and (5) insufficient command of the English language.

2.3.1. Implementation Site Demographics.

The three implementation sites will provide great depth and breadth across multiple spectra of diversity. Participants will be recruited to one of three sites: Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, MA; Fenway Health in Boston, MA; and Thomas Street Health Center in Houston, TX. Participants at Thomas Street Health Center will provide us with broader racial and ethnic diversity: patient make-up at Thomas Street is 59% Black and 31% Hispanic/Latino (compared to a patient system that is >80% Caucasian and 90% non-Hispanic at Fenway Health and a patient population that is estimated to be approximately >50% Caucasian and 85% non-Hispanic/Latino at Massachusetts General Hospital). Fenway Health will provide a greater subset of participants with diverse sexual orientations: the majority of patients at Fenway Health are gay or bisexual. Additionally, Thomas Street Health Center will provide greater gender diversity as more than 25% of the patients identify as cis-gender female. All eligible participants will be enrolled without regard to ethnic, racial, socioeconomic, sexual, or gender identity.

2.4. Procedures

The study is funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; R01DA047933) and is registered on clinicaltrials.gov (ID: NCT03904186). Enrollment to the RCT began in December 2019 and, as of this writing, is in the recruitment phase. Although assessments and treatment were proposed to be delivered in-person, procedures were modified to allow for remote administration in response to the novel coronavirus pandemic. The trial consists of a baseline assessment, 10-session intervention period, and follow-up assessments. Participants in each condition will receive the same set of questionnaires at every visit. These questionnaires are standardized across all visits and conditions and will assess anxiety/depressive symptoms, distress tolerance, and smoking abstinence. The Institutional Review Board at Mass General Brigham approved the study and serves as the Single IRB for all sites under the National Institutes of Health Single IRB policy29, and a Data Safety and Monitoring Board provides ongoing oversight.

We aim to recruit a sample of 180 participants (60 at each implementation site). We anticipate an attrition rate of 50% at study follow-up assessments, which will result in 90 participants who complete the entire study across sites. Participants will be recruited via referrals from doctors within the infectious disease units at the study sites (two of the project co-investigators, Drs. Robbins and Giordano, are healthcare providers who specialize in HIV, and will aid in recruiting participants), posted fliers at community organizations, and through multimedia platforms, such as LGBTQ dating sites, Craigslist, and healthcare system research portals. Of note, participants do not need to be service-connected to any of these three centers to be eligible for our study; this decision was made in an effort to recruit a sample that will be more generalizable to the broader population. Interested participants will complete a brief screener, either via phone or in-person, to assess age, HIV diagnosis, number of cigarettes smoked, motivation to quit smoking (and recent quit attempts, if the participant is not motivated to quit smoking currently), non-cigarette tobacco products used more than three times per week, concurrent smoking cessation medication and/or treatment, and use of English. Individuals eligible at the phone screener will be scheduled for an initial baseline appointment (Visit 1/week 0) to further evaluate eligibility. At baseline (Visit 1/week 0), participants will meet with a trained research assistant who will obtain informed consent and administer a self-report battery and complete a structured clinical interview with a trained master’s level clinician. In response to the coronavirus pandemic, all appointments will be completed in-person, on the phone, or via a secure videoconferencing program, depending on local conditions and preference of the participants.

Eligible participants will be scheduled for a pre-randomization treatment appointment (week 1/session 1). This appointment will provide psychoeducation for smoking cessation and withdrawal; support for quitting; discussion of health consequences of continued smoking and benefits of quitting; past quit experiences; and motivation for smoking and smoking cessation. Consistent with our pilot RCT trial,26 we included a pre-randomization treatment visit to build rapport and trust that would support treatment compliance and study retention. Participants will then be scheduled for their next appointment and informed they will be randomized to a condition at that time (i.e., week 2/session 2). Participants will be randomized using variable-sized permuted block-randomization to allocate participants to treatment condition at each site (n=72 to QUIT, n=72 to TMC, n=36 to SOC) at their second treatment session. The study statistician, who will have no contact with participants thereby preventing experimenter bias in randomization, will oversee the randomization process. Prior to study implementation, randomization schema tables (stratified by sex assigned at birth and implementation site) will be created by the study statistician. The study Project Manager uploaded the tables to REDCap, which is a secure HIPAA-compliant data collection and management tool housed behind the MGH firewall. Only the study Project Manager can see and access the tables once uploaded to REDCap – all other study team members will utilize the REDCap randomization module, which hides the allocation until randomization is prompted. When the participant arrives for session 2, the site managers/coordinators will use REDCap to randomize the participant and communicate the allocation to the Research Assistant and Therapist. The Therapist will then inform their participant of the allocation and either conduct a therapy session (for those allocated to QUIT and TMC conditions) or will have the Research Assistant take over the visit and administer questionnaires (for those allocated to the SOC condition). The REDCap randomization module was tested thoroughly before the trial began, to ensure that outputs mirrored the allocations in the original tables. Additionally, after each randomization, the Project Manager compares the randomization allocation in REDCap to the tables provided by the study statistician as a secondary check. Each treatment condition will consist of nine weekly appointments with sessions 2–6 corresponding to pre-quit treatment (weeks 2–6) and sessions 7–10 corresponding to post-quit treatment (weeks 7–10); the participant’s quit date will be scheduled for session 7 for each condition, which will allow sufficient time to gain preliminary mastery over skills presented in treatment. While we will be flexible with participant rescheduling pre-Session 7 (i.e., quit day), missed appointments post-quit day will result in a missed session, with participants moving ahead to their next session the following week. This decision was made to both follow clinical suggestions of length of NRT use, as well as adhere to our data analysis schema (e.g., ensure that the 1-month follow up is assessed within window). We will make a note of both delayed and missed sessions, and will account for these discrepancies in data analysis. Participants will complete a brief assessment of smoking and mood-related constructs at each session and receive nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) starting on the quit day (week 7/session 7).

We chose the long-acting transdermal nicotine patch because of extensive empirical literature supporting its effectiveness and safety, its ease of use, and its relatively benign side effects, making it an over-the-counter medication. Additionally, recent literature has attributed an increase in cessation success of up to 98% to a combination of behavioral and pharmacotherapy treatment.30 Thus, we should be able to easily discover differences between our behavioral conditions (QUIT and TMC) and our SOC condition, as well as determine whether the targeted mechanisms in our QUIT treatment lead to cessation successes over and above a standard behavioral and pharmacotherapeutic treatment. As our treatments encourage a “tiered” approach to cessation (e.g., gradually reducing number of cigarettes until Quit Day, rather than going “cold turkey”), many of participants will likely not attempt or be quit prior to their assigned Quit Day; therefore, we will provide them with NRT on their Quit Day, rather than earlier. We will follow the Food and Drug Administration guidelines for dose and time administration.31

The participant’s clinician or research assistant will provide the participant with instructions on usage and supply the correct dosage at each study visit for the following week. NRT usage is not required for study participation (participants can choose to opt-out), but if they choose to partake in the NRT usage, participants will receive eight weeks of nicotine replacement therapy as part of the study.

Following completion of intervention phase, participants will be asked to complete 30-minute follow-up sessions at 1-, 3, and 6-months post-quit week (weeks 11, 19, and 31, respectively). The study staff will assess self-reported smoking status and collect biochemical verification of smoking status at follow-ups. Participants will receive $15 for every weekly session they complete for a total of $150 for each participant. Additionally, participants will receive $50 for each of the four major assessments (baseline, 1-month follow-up, 3-month follow-up, 6-month follow-up), for an overall total of $350; ineligible participants will be compensated $50 for completing the baseline.

2.5. Intervention Conditions

2.5.1. Time-Matched Control (TMC).

Consistent with our established manualized procedures for standard smoking cessation treatment,32 the TMC involves a combination of CBT plus NRT. The TMC is based on the most recent clinical practice guideline from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence.33 The treatment will consist of nine 60-minute weekly sessions. The study therapists will cover topics such as smoking and abstinence history, individualized smoking cessation barriers, maladaptive cognitions around the use of cigarettes, using cigarettes as a way to cope with stress and negative affect, and identifying and planning for triggers and high-risk situations. See Table 1 for session content.

Table 1.

TM Control Treatment Modules.

| Session 2 |

|---|

| • Overview of treatment • Smoking history and prior quit attempts • Health benefits of quitting smoking • Reasons for smoking and quitting • Importance of cigarette monitoring |

|

|

| Session 3 |

| • Identify high-risk situations • Cigarette reduction • Psychoeducation on nicotine addiction • Cognitive restructuring |

|

|

| Session 4 |

| • Cognitive restructuring and automatic thoughts • New response to high-risk situations • Cigarette reduction • Social support |

|

|

| session 5 |

| • Plan for reducing cigarette use •Review skills (cognitive restructuring, social support, and planning for high-risk situations) |

|

|

| Session 6 |

| • Review plan for high-risk situations • Preparation for Quit Day • Coping card • Continued self-monitoring • Discuss the nicotine patch |

|

|

| Session 7 (QUIT WEEK) |

| • Quit experience and withdrawal symptoms • Review plan for high-risk situations • Barriers for abstinence and motivation for quit • Create abstinence plans • Review importance of social support and handouts |

|

|

| Session 8 |

| • Quit experience and withdrawal symptoms • Positive quit benefits • Review plan for high-risk situations • Lifestyle changes to support the quit |

|

|

| Session 9 |

| • Quit experience and withdrawal symptoms • Positive quit benefits • Review plan for high-risk situations • Relapse prevention • Lifestyle changes to support the quit |

|

|

| Session 10 |

| • Relapse prevention • Lifestyle changes to support the quit • Review plan for high-risk situations • Support continued practice |

2.5.2. Integrated CBT-based, transdiagnostic treatment (QUIT).

QUIT integrates a standard smoking cessation protocol (i.e., CBT plus NRT) with a transdiagnostic CBT-based protocol designed to address anxiety and depressed mood. To tailor QUIT for individuals with HIV, the intervention also integrates psychoeducation on the relation between smoking and HIV status, including the intersection of smoking and HIV with respect to HIV treatment response, HIV-related health implications including HIV disease progression and survival, and the increased risk for non-HIV related illnesses. Additionally, psychoeducation specifically relevant to SLWH will be presented, such as sleep, pneumonia, and cardiovascular health. This information will be integrated throughout QUIT and allow for flexibility to address additional topics related to living with HIV and being a smoker, such as stigma. It will be delivered in nine 60-minute individual weekly sessions. Procedures draw heavily on standard CBT practice for anxiety and depressive disorders, yet incorporate novel elements designed to target vulnerabilities linked with difficulties in ceasing smoking, namely anxiety sensitivity,34,35 distress tolerance,36 and anhedonia.24 Sessions are active, with treatment components practiced inside and outside the session. The main goal of QUIT is to help participants learn healthy and adaptive long-term strategies for tolerating, coping with, and effectively reducing negative emotions and for enhancing positive emotions without smoking. The treatment consists of four key components to achieve this goal: (1) psychoeducation on smoking and mood; (2) addressing dysfunctional cognitive processes; (3) addressing dysfunctional behavioral processes; and (4) relapse prevention. See Table 2 for session content.

Table 2.

QUIT Treatment Modules.

| Session 2 |

|---|

| • Treatment rationale • Monitor and reduce cigarette use prior to Quit Day • Relationship between smoking and emotions • Discuss pros and cons of smoking • Education about smoking and HIV |

|

|

| Session 3 |

| • Introduction of the CBT model for smoking • Introduction to behavioral approach to quitting • Identifying high risk situations, smoking -related thoughts, and rate distress • Education about HIV and smoking |

|

|

| Session 4 |

| • In-session behavioral experiment/craving exposure exercises • Apply behavioral experiment/exposure for negative emotions broadly • Education about HIV and smoking |

|

|

| Session 5 |

| • Behavioral activation/pleasant event scheduling • Cognitive approach to quitting smoking, including identifying automatic thoughts • Cognitive restructuring/common smoking myths • Education about HIV and smoking |

| Session 6 |

| • Continue cognitive restructuring • Preparation for Quit Day • Discuss the nicotine patch • Education about HIV and smoking |

|

|

| Session 7 (QUIT WEEK) |

| • Quit experience and withdrawal symptoms • Barriers for abstinence and motivation for quit • Create abstinence plans • Skills practice (behavioral experiments/exposures for craving and physical anxiety symptoms, pleasant event planning, and cognitive restructuring) • Education about HIV and smoking |

|

|

| Sessions 8 |

| • Quit experience and withdrawal symptoms • Positive quit benefits • Barriers for abstinence and motivation for quit • Skills practice (behavioral experiments/exposures for craving and physical anxiety symptoms, pleasant event planning, and cognitive restructuring) • Relapse prevention • Education about HIV and smoking |

|

|

| Session 9 |

| • Quit experience and withdrawal symptoms • Positive quit benefits • Barriers for abstinence and motivation for quit • Skills practice (behavioral experiments/exposures for craving and physical anxiety symptoms, pleasant event planning, and cognitive restructuring) • Relapse prevention • Education about HIV and smoking |

|

|

| Session 10 |

| • Quit experience and withdrawal symptoms • Positive quit benefits • Barriers for abstinence • Review treatment program • Review relapse prevention • Lifestyle changes to maintain abstinence • Education about HIV and smoking • Support continued practice |

Psychoeducation.

Participants will receive psychoeducation regarding the nature of depression and anxiety, distress intolerance, and the CBT model. The concept of a fear-avoidance hierarchy will be discussed, and each participant will develop a hierarchy with their therapist’s help. Psychoeducation regarding the relation between anxiety and depression and the relation between smoking and anxiety and depression will be provided, and smoking situations will be included in the fear/avoidance hierarchy. Participants also will learn how greater distress tolerance skills can facilitate emotional adaptation without smoking.

Dysfunctional cognitive processes.

Automatic thoughts and cognitive restructuring will be introduced. The process of asking and answering disputing questions and developing rational responses will be developed and will target anxiety sensitivity (e.g., “I will go crazy if I’m anxious and unable to smoke”) and distress intolerance (e.g., “I cannot tolerate withdrawal”) separately. Activities will include monitoring and disputing these thoughts, including an explicit focus on identification of cognitions related to smoking and distress.

Dysfunctional behavioral processes.

Separate behavioral exercises will be employed to target the three vulnerability constructs. To target anxiety sensitivity, in-session graduated exposure to anxiety and distress-provoking situations and response prevention are introduced, negotiated, and planned, with the goal of offsetting motivation to resume smoking out of fear of experiencing anxiety symptoms. To target distress intolerance, smoking-related cues will be introduced during in-session exposure exercises so that participants can learn to manage cravings while experiencing elevated distress states without acting on acute motivation to suppress distress via smoking. Finally, to target anhedonia, behavioral activation and scheduling of pleasurable events will be devised and implemented to target action strategies associated with low positive affect.

Termination and relapse prevention.

The post-quit sessions (sessions 7–10) will be used to develop relapse prevention action plans and cover termination issues. These sessions will reiterate the importance of continuing to practice skills learned in treatment as well as developing specific plans for how to remain abstinent. Participants and therapists also will discuss challenges in remaining abstinent and problem-solve to identify skills that can help support the quit attempt. Treatment gains will also be discussed to increase self-efficacy to manage mood without smoking.

2.5.3. Standard of Care (SOC).

Each of the three recruitment sites characterize SOC as a) routine assessment of smoking status that occurs at least annually for patients receiving care, b) infrequent prescription for pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation and very infrequent referral for behavioral smoking cessation services, and c) the availability of open enrollment smoking cessation support groups. Consistent with this operationalization of SOC, participants assigned to this condition will complete a weekly assessment for the remaining nine weeks; each appointment will last 20 minutes. Should the participants in this group signal a need for extra help with cessation post-randomization (and pre-quit day), they will be reminded that they can reach out to their primary doctor. Participants will receive NRT starting quit day, but no additional intervention to assist with smoking cessation.

2.6. Therapist Training and Supervision

Study therapists will be masters- and doctoral-level clinicians (clinical psychology, social work, or other mental health specialty) and will deliver all treatments. Therapists will complete a multi-day training on QUIT and TMC with a PhD-level clinician with expertise delivering QUIT and smoking cessation treatment. The training will consist of role plays, review of QUIT session recordings, and didactics. After successfully completing the training, treatment fidelity will be continually monitored and assessed during on-going weekly supervision meetings. To assist with supervision and treatment fidelity assessment, all treatment sessions will be audio-recorded. Therapists consistently not meeting acceptable treatment adherence, therapist competency, or contamination ratings will receive remedial training.

2.7. Assessments

Data collected will include self-report, clinician administered, and biospecimens. See Table 3 for schedule of data collection.

Table 3.

Measures

| SCREENING | BASELINE | ACTIVE TX | 1M Post-Quit (End of Treatment) | 3M Post-Quit | 6M Post-Quit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SELF-REPORT | ||||||

| SCREENING AND DESCRIPTIVE MEASURES | ||||||

| Demographics | X | X | ||||

| Screener Questions | X | |||||

| FTND | X | |||||

| SHQ | X | X | ||||

| Motivation to Quit | X | X | ||||

| ASSESSMENT OF ABSTINENCE | ||||||

| TLFB | X | X | X | X | X | |

| ANXIETY AND DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS | ||||||

| PHQ8 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| OASIS | X | X | X | X | X | |

| TRANSDIAGNOSTIC MECHANISMS | ||||||

| SSASI | X | X | X | X | X | |

| DTS | X | X | X | X | X | |

| SHAPS | X | X | X | X | X | |

| COST-EFFECTIVENESS | ||||||

| EQ-5D-3L | X | X | X | |||

| Resource Utilization for Cost | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| HIV-RELATED VARIABLES | ||||||

| RUQ | X | X | X | X | ||

| ART Adherence | X | X | X | X | X | |

| ACTG SF-12 | X | X | ||||

| CLINICIAN ADMINISTERED/COMPLETED | ||||||

| MINI | X | |||||

| Therapist Adherence | X | |||||

| BIOLOGICALLY VERIFIED | ||||||

| Carbon Monoxide Analysis | X | X | X* | X* | X* | |

| Saliva Cotinine Analysis * | X* | X* | X* | |||

| Urine Anabasine Analysis * | X* | X* | X* | |||

| Third-party smoking abstinence verification * | X* | X* | X* | |||

| CD4 and Viral Load | X | X | ||||

Dependent on a participant’s use/non-use of NRT, participants may complete select biological verifications at follow-ups. Please see page 23 for more details.

2.7.1. Screening and Descriptive Measures

Demographics and Screener Questions.

Participants will be asked to provide standard demographic information (i.e., name, contact information, age, sex, race/ethnicity, level of education, etc.), current smoking cessation treatment status, past-year history of CBT for anxiety disorder, and comfort with the English language at baseline.

Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND).

The FTND is a 6-item scale designed to assess gradations in tobacco dependence.37 This measure will serve to quantify nicotine dependence at baseline.

Smoking History Questionnaire (SHQ).

Smoking history and pattern will be assessed with the SHQ, a 30-item measure that includes items pertaining to smoking rate, age of initiation, years of smoking habitually.38 This measure will serve to contextualize the participants’ smoking behavior and history at baseline.

Motivation to Quit.

Two items will be used to assess motivation to quit. First, participants will be asked to self-report their motivation to quit smoking cigarettes on a 10-point Likert scale, with 1 being not at all motivated to 10 being extremely motivated. Second, participants will be asked if they have engaged in a recent (past-year) quit attempt that lasted at least 24 hours. Motivation will be assessed at the phone screener and baseline appointment to determine eligibility.

MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI).

The MINI is a short structured clinical interview for diagnosis of psychiatric disorders according to DSM-5.39 The MINI will be administered by trained research personnel with a master’s degree in psychology or another mental-health related field at baseline. Those who report current interfering, untreated, or unstable major mental health condition (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or psychosis) during the MINI will be excluded.

2.7.2. Assessment of Abstinence

Self-reported smoking status will be assessed at each session, and at 1-month, 3-month, and 6-month follow-up (i.e., post-quit). Self-reported abstinence will be verified via an expired carbon monoxide (CO) breath analysis at all timepoints, as well as biochemically confirmed at all follow up assessments by saliva cotinine for participants who do not report NRT use and a urine assessment of anabasine for participants who report using NRT. Anabasine assays will be employed for participants currently utilizing NRT as anabasine concentrations in urine are traditionally used to validate abstinence from tobacco in the presence of NRT.40 Participants who are unable or unwilling to provide urine assessment to test for anabasine will be required to have a significant other confirm the participant’s abstinence status (other verified); similar methods have been successfully used in previous smoking trials.41 Values of 30 ng/mL42 for saliva cotinine and 3 ng/mLfor anabasine43,44 will be used as cutoffs for abstinence. We will use the timeline follow-back (TLFB) measure at all assessments to assess daily cigarette consumption; this procedure has demonstrated good reliability and validity.45 Self-reported abstinence will be overridden by a positive saliva cotinine (>30 ng/mL) or anabasine (>3 ng/mL) assessment or positive smoking status according to ‘other verified’ data. If cotinine, anabasine, or ‘other verified’ data are not available to verify abstinence at an assessment, abstinence will be considered missing data.46 The main outcome analyses are based upon 7-day point prevalence abstinence (PPA, biochemically/other verified + reported abstinence of at least 7 days). PPA will be defined as biochemically/other verified no smoking, not even a puff, in the 7 days prior to any assessment.

2.7.3. Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms

The Patient Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-8).

The PHQ-8 is an 8-item measure of current severity of depression (or lack of depression).47 The PHQ-8 will be administered at all study assessments.

The Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS).

OASIS is a 5-item scale that assesses the severity and impairment related to anxiety-related symptoms.48 The OASIS will be administered at all study assessments.

2.7.4. Transdiagnostic Mechanisms

Short-Scale Anxiety Sensitivity Index (SSASI).

The SSASI is a 5-item measure that assesses sensitivity to, and discomfort with, physical sensations.49 This measure was derived from the original 18-item Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3.22 The SSASI will be administered at all study timepoints.

Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS).

The DTS is a 15-item self-report measure that assesses participants’ perceived ability to tolerate emotional distress.50 The DTS will be administered at all study timepoints.

Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS).

The SHAPS is a 14-item self-report measure that assesses participants’ current levels of anhedonia.51 The SHAPS will be administered at all study timepoints.

2.7.5. Cost Effectiveness Outcomes

In cost-effectiveness analyses, our measures of effectiveness will include the primary trial endpoint – biochemically/other-confirmed 7-day PPA – and quality-adjusted life years (QALY) saved. QALYs will be measured by combining assessments from health utility instruments which provide a measure of health valued at 1 (perfect health) and 0 (death) and vital status over the study follow-up period. “Health utility” assessments weigh survival time by the quality of life a participant experiences over that time: e.g., 1 QALY saved could be achieved by living one additional year in perfect health or 2 additional years in health deemed to have an average health utility value of 0.5.

EQ-5D Instrument.

We will measure health utilities at baseline and 6 month follow up with the EQ-5D instrument,52 a 5-item scale that has been shown sensitive to variations in health states related to HIV, mental health,53,54 and tobacco use.55,56 Recently, this instrument has also been validated in HIV positive samples in North America.57

Resource Utilization for Cost.

We will collect resource utilization data regarding the delivery of the counseling intervention for participants in all three arms of the study, the use of cessation medications (including those used by participants that were not provided by the study), and time costs for participants. Personnel time: We will assemble data regarding the time required to train the therapist (trainer and therapist time) and for the therapist to deliver the intervention, write chart notes, and obtain clinical supervision. We will include prorated overhead and space costs. These data will be collected from notations in the project management database. Medical care: Though study provision of NRT will be equal across study arms, we will use the Resource Utilization Questionnaire to track overall use of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation in case participants seek additional medications on their own. The cost of these medications will be estimated using values from the Medicaid National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC)58 database, the VA Drug Pricing Database59 and the Pharmacy Red Book.60 Changes in health care use and health expenditures do not typically appear in the very short-term (i.e. months after cessation).61,62 Nevertheless, for completeness we will track subjects’ health care use during the study and follow-up periods using each site’s clinical data systems. The cost of this care will be estimated using Medicare payment rates63 to apply nationally standardized prices. Participant time: For the societal perspective analysis, we will track participant costs incurred due to the interventions, specifically time devoted to scheduling and receiving treatment, and additional costs such as transportation. Time devoted to the intervention outside of direct counseling sessions (e.g., “homework”) and transportation costs will be ascertained by a participant time questionnaire. Time will be valued according to national average wage data for the participant’s age and education.64

2.7.6. HIV-Related Variables

Although none of our primary or secondary outcomes are directly analyzing HIV-related markers, previous research has shown that SLWH may have difficulties with ART uptake.65–67 For that reason, we will also be obtaining a number of HIV-related variables for descriptive purposes.

HIV-related biomarkers.

Participants will be asked to fill out a medical record release at their baseline and 6MFU to collect the most recent CD4+ and HIV viral load count.

Resource Utilization Questionnaire.

The Resource Utilization Questionnaire (RUQ) was developed by our MGH team, who have used it in many studies in the past. It will be used to measure participant healthcare utilization at all assessment timepoints.

ART Adherence.

ART adherence will be measured via self-report68 for up to four medications. It will be assessed at all timepoints.

ACTG SF-12.

The ACTG SF-12 will be used to measure health-related quality of life53 at baseline and 6MFU.

2.7.7. Other Variables

Therapist Adherence.

20% of all audio recordings will be rated for therapist competency, fidelity (if session 1 or QUIT), and contamination (if TMC) by other study clinicians and PIs. Competency ratings are comprised of four questions on a scale of 0–4, for a cumulative potential total of 16 points; fidelity ratings are comprised of a varying number of yes/no questions (0 or 1) for a potential total of up to 13 points; and contamination ratings are comprised of a standard set of 10 yes/no questions (0 or 1) for a cumulative potential total of 10 points. All scores will be tabulated and averaged by a trained research assistant, who will track both therapist and rater averages of fidelity, competency, and contamination scores, and alert the lead clinician if any therapist scores are significantly low.

2.8. Data Analysis

2.8.1. Overview

The primary objective of this project is to examine the effects of QUIT over TMC and SOC for smoking cessation. Primary outcome will be PPA at the 6-month follow-up. We will first assess the equivalence of the treatment groups on key baseline variables (demographics and psychological variables); variables on which the groups differ will be used as covariates in the final analyses. We also will examine the correlation between putative mediators to evaluate potential multicollinearity that may dampen effects; if any of the mediators (depression, anxiety, anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, and/or anhedonia) are highly correlated (r≥.75), they will be combined (averaged together) for the mediation analyses. We will then examine missing data patterns, dropout rates (see below), and distributional properties of measures, and use transformations to improve distributions if necessary.

Abstinence data (PPA) will be analyzed using Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMM), employing a logistic linking function (see below for details of the model). GLMM includes all subjects, regardless of missing data, and does not require imputation of missing data (e.g., as in last-observation-carried-forward analyses, or when all missing data is coded as smoking).46 GLMM is the recommended intent-to-treat approach for longitudinal smoking cessation trials.69

As in previous research,28,70 we will use a 3-phase piecewise growth curve model to model PPA over the study period. The first phase of the growth model will be from randomization to week 6 (pre-quit treatment phase), the second phase will be weeks 7–11 (post-quit treatment and 1-week follow-up phase), and the third phase will be from weeks 11–30 (follow-up phase). Primary endpoint will be week 30 (6-month follow-up). We will model the change over time as curvilinear within each phase and model a discontinuity in the growth curve between the first and second phase to reflect a jump in abstinence on the scheduled quit day. Psychological outcomes will be analyzed using multilevel modeling (MLM), using the same growth curve model. But since there may not be any substantial change in the psychological variables at quit week, nonsignificant discontinuities and nonsignificant slope differences between phases will be dropped.

2.8.2. Aims

Aim 1a (QUIT will engender higher abstinence rates (PPA) at 1-month and at the 6-month follow-up, compared to TMC and SOC).

In two GLMM analyses, we will alternately “center” our time variables at each of the endpoints (end of treatment and 6-month follow-up) to estimate between-group differences at each respective endpoint. Treatment Condition will be coded with 2 dummy variables: one coding the comparison of QUIT to control, and the other coding the comparison of QUIT to SOC. These treatment condition dummy variables will be included as predictors of the slope of change in outcomes during each phase of the study. The significance of each dummy variable comparison will test whether QUIT is superior to TMC and/or SOC at that endpoint. If significant in an analysis, the treatment condition effect will demonstrate that abstinence rates are significantly different between QUIT and the comparison groups at the respective end point.

Aim 1b (QUIT will engender greater reductions in depression and anxiety symptoms at 1-month and at the 6-month follow-up, compared to TMC and SOC).

We will model depression (PHQ-8) and anxiety symptom (OASIS) growth similar to PPA. However, if a 2-phase growth curve model (treatment phase and follow-up phase) fits the data better (i.e., lower AIC [Akaiki Information Criterion] and lower BIC [Bayesian Information Criterion]) than the 3-phase growth curve used for PPA, we will use a 2-phase growth curve model. Given that our measures of depression and anxiety symptoms are continuous, we will use MLM (which models the dependent variable as continuous) to analyze the trajectory of depression and anxiety symptoms. Treatment condition dummy variables will be included as predictors of the slope of change in outcomes during each phase of the study. The significance of each dummy variable comparison will test whether QUIT is superior to TMC and/or SOC at that endpoint. If statistically significant in an analysis, the treatment condition effect will demonstrate that change in depression or anxiety symptoms are significantly different between QUIT and the comparison groups at the respective end point.

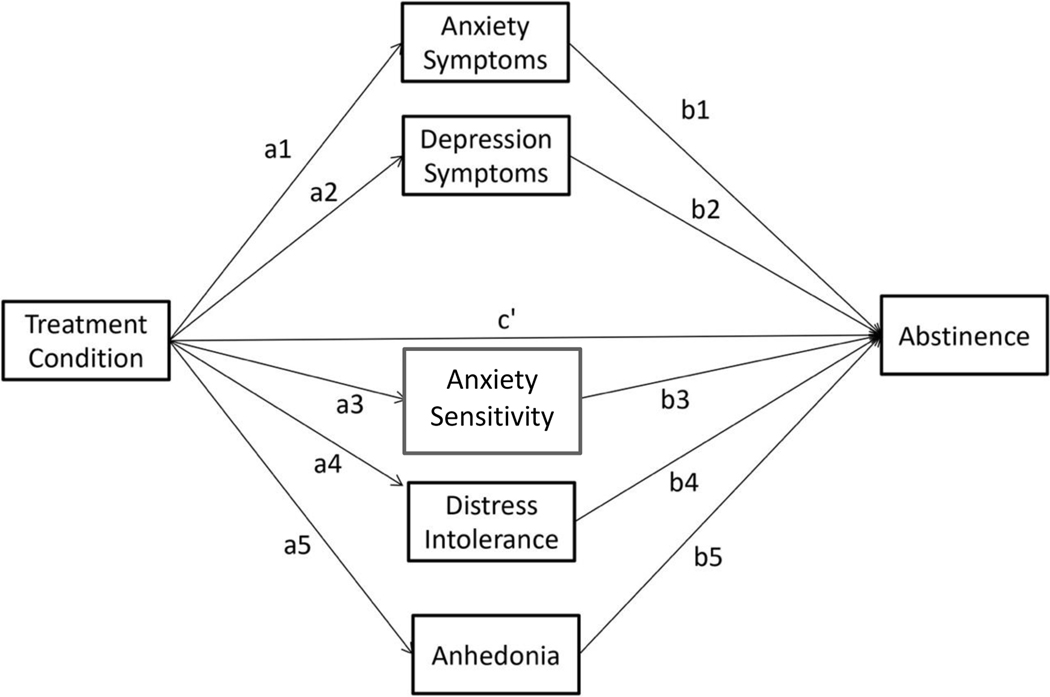

Aim 2a (Greater abstinence in QUIT compared to TMC and SOC will be partially mediated by reductions in depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, anxiety sensitivity, distress intolerance, and anhedonia at 1-month follow-up).

All 5 mediators will be included simultaneously in a single mediation analysis to determine which are significant mediators of the treatment effect on abstinence over and above the others (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mediation Model.

We will use multilevel modeling (MLM) instead of GLMM to calculate the “a” path in our mediation model (the effect of treatment on depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, SSASI, DTS, and anhedonia) because the outcomes for the “a” paths (the mediators) are continuous variables. The “b” paths in our mediation model will be the regression coefficients for the six putative mediators when they are all added simultaneously to the GLMM analysis for PPA (the model in Aim 1a). In order for the “b” path to more closely estimate the causal relation between putative mediators and abstinence, we will use a cross lag mediation analysis, in which the mediators at time “t” predict the outcome at the next assessment (“t+1”), controlling for the outcome at time “t” (as we have done in previous multimediator longitudinal models).71 Further, for accurate calculation of the cross lag effects, recent research72–74 indicates that one must disaggregate the between-person and within-person components of time-varying predictors (i.e., the mediators), and estimate both effects in the same model. Thus, we will include both between- and within-person effects of all mediators in the mediation analysis. The significance of the mediated pathways will be calculated using the distribution of products test performed by the program RMediation.75

Aim 2b (Sex will moderate treatment effects).

To determine whether sex moderates the effect of condition on abstinence, we will add an interaction between sex and all of the growth curve parameters in the GLMM piecewise growth curve model testing Aim 1a. Any significant interactions will indicate that there are moderator effects in that portion of the piecewise growth curve. To investigate if mediation depends on these factors, we will add the interaction of sex with the “a” paths, the “b” paths, and the “c” paths in our mediation model in Aim 2a. If moderation is significant, we will calculate the significance of the mediated pathway for males and for females, separately. A similar statisticsl approach will be used to test anxiety sensitivity as an exploratory moderator of observed effects.

Aim 3 (The incremental cost effectiveness of QUIT relative to SOC will compare favorably to other smoking cessation interventions).

Our cost-effectiveness analysis will estimate the incremental cost per quit and the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) at week 24. Cost per quit is a smoking-specific measure that will allow direct comparison with other smoking cessation strategies; cost per QALY is a general measure of cost-effectiveness that allows comparison across the full spectrum of health care policies, strategies, and interventions. Following current methodological recommendations, we will assess these measures of cost-effectiveness from both a societal perspective and from a health system perspective.47 Given resource constraints, we will not estimate cost per QALY over participants’ complete lifespans as that would require a significant mathematical modeling effort. However, our data on short-term costs and QALY improvements will be readily usable to assess lifetime cost per QALY using advanced modeling techniques developed by Reddy and others.76

We will calculate the incremental cost per quit of the QUIT intervention, as well as the TMC relative to SOC using standard methods77 as we have done in our prior studies,78–80 i.e., cost-effectiveness is equal to (Total cost at 6 months arm[i]-Total costs at 6 months arm[j])/(Total cotinine confirmed quits at 6 months arm[i]-Total cotinine confirmed quits at 6 months arm[j]). Incremental cost per quality of life years saved analyses will proceed similarly. We will use Monte Carlo simulation methods incorporating uncertainty in the calculation parameters to develop confidence bounds on our cost per quit and cost per QALY estimates. Following standard methods of economic evaluation, we will also perform parameter-specific sensitivity analyses in which individual parameters are varied singly and in combination, through plausible ranges to assess the relative impact different elements of the program have on overall cost-effectiveness.80–83

2.8.3. Missing Data

We will use pattern mixture modeling to assess the effect of missing data. We will rerun our analyses coding for various missing data patterns (no missing data, sporadic missing, dropouts, etc.) to determine (1) if missingness impacts our findings and (2) how the differences between treatment conditions depends on the missing data pattern. We also will conduct sensitivity analyses to compare findings when missing abstinence data are coded in two additional ways: (1) using last observation carried forward (LOCF) and (2) coding all missing data as “smoking”.46

2.8.4. Statistical Power

Aim 1.

We performed a Monte Carlo study to calculate the minimum between-group differences in abstinence rates detectable by our analysis. For this study, we conservatively assumed a dropout rate of 50% by the 6-month follow-up and assumed a total of 27% missing data (there was 26.6% missing in our pilot study) for the 180 participants. The study was powered for QUIT compared to TMC with the understanding that the cessation rate for SOC would be lower than TMC. We assumed a 10% abstinence rate in the TMC condition at the 6-month follow-up (this rate is twice as high as the rate we found in the control condition in our pilot study [5%] at the 6-month follow-up). We examined numerous abstinence rates for QUIT to determine the lowest rate detectable by our analysis with .80 power, performing 1,000 simulations for each tested abstinence rate. The results indicated that with our planned sample size we would have greater than .80 power to detect a significant condition effect if the abstinence rate in experimental group was 23% or greater.

Aims 2a.

Our Monte Carlo study indicated that we would have greater than .91 power to detect mediation for a mediated pathway if the “a” path and the “b” path were of medium effect size or greater.

Aim 2b.

For the aim of sex moderating the effects of condition on PPA, again we would have .80 power to detect a difference of approximately 16% between males and females in the effect of treatment condition on abstinence. The power to detect medium sized-mediated pathways is just slightly decreased by having additional sex interactions in the model.

Aim 3.

The study is powered to detect primary and secondary clinical endpoints for Aims 1 and 2. However, Monte Carlo methods will be used to estimate confidence bounds for the composite outcome of cost and effectiveness that will accurately assess feasibility and guide dissemination.

2.9. Status Update

2.9.1. Current Numbers

As of April 13, 2021, 90 participants have been screened for the study; 51 have given verbal and/or written consent to participate in the study and have completed a baseline assessment; 46 have been enrolled post-baseline; 41 have been randomized; and 12 have completed the study (including all follow-ups). Our current attrition rate is much better than anticipated, standing at approximately 9.8%.

2.9.2. COVID-19 Adaptations

Two sites, MGH and Fenway Health, were actively recruiting and enrolling participants at the time that COVID-19 stay-at-home advisories affected in-person work in Boston. However, all but one of our enrolled participants were willing and able to shift to remote visits. New participants were enrolled under a fully remote process at our two Boston sites, and recruitment was able to continue uninterrupted under these new processes. Per Massachusetts state and site-specific guidelines, most study procedures have remained remote, and in-person work will be limited to a case-by-case basis.

Our Houston site at Thomas Street Health Clinic opened to recruitment in July of 2020 and is operating in a hybrid model. Most potential participants are coming to the clinic for laboratory appointments and to access the pharmacy during the pandemic and are recruited in-person. Referrals from HIV clinicians are also being collected and contacted by phone. The consent, intervention and evaluation procedures have been available both in person and remotely, with varying in-person uptake depending on the status of the pandemic.

Preliminary data analyses will determine whether outcomes at each assessment are impacted by remote status due to COVID-19. Since in-person treatment and assessments were curtailed during treatment for some participants, and may be re-implemented for others after COVID-19 restrictions are lifted, each assessment will be coded for remote status due to COVID-19 restrictions (0=in-person, 1=remote). Preliminary analysis will investigate whether remote status due to COVID-19 restrictions (as a time-varying predictor) predicts or moderates each outcome. If remote status is not related to outcomes, it will be dropped and our primary analyses will be conducted as originally specified. If it is related to outcome, then final analyses will include its significant predictor/moderator effects, and results will be reported for both in-person and remote treatments/assessments.

3. DISCUSSION

A substantial group of SLWH would benefit from a smoking cessation intervention that reduces anxiety and depression. Emerging evidence points to the utility of integrating standard smoking cessation care with a transdiagnostic intervention that engages therapeutic targets (anxiety sensitivity, distress intolerance, and anhedonia) for ameliorating anxiety and depression. Our treatment, QUIT, targets these specific mechanisms, thereby enhancing the odds of cessation success among SLWH. Building on our pilot project, the proposed study aims to address the smoking-based health disparity among SLWH by testing whether QUIT outperforms an active, credible TMC and a SOC control. We are testing the intervention in a diverse population of SLWH recruited from three clinical settings in two large cities. The complexity of the 3-arm hybrid efficacy/effectiveness design allows us to advance the science expeditiously, with a time-matched control to answer the efficacy questions and a standard of care condition to address cost effectiveness. If successful, the intervention would be ready for implementation and dissemination into “real-world” behavioral health and social service settings consistent with the four objectives outlined in NIDA’s Strategic Plan. Indeed, the varying demographics served at each implementation site coupled with our keen attention to ensuring treatment materials are understood by individuals with varying levels of educational and technological backgrounds will lend well to help generalize findings and support treatment implementation to a broader population of SLWH. Moreover, we are also creating a variety of tools, which will be of great benefit for community dissemination. Training tools (e.g., agendas and PowerPoints) have been created as part of the study to train our clinicians and can be easily adapted to community-based clinicians who may have less knowledge of CBT techniques. Clinicians are also provided with QUIT handbooks to follow, which outline a “script” of everything that should be covered at each visit. These resources will support the easy adoption of QUIT into point of care settings.

Notably, study procedures have been and will continue to be adapted in response to the coronavirus pandemic. As such, this study may serve as a clinically important example for how to implement remote/virtual smoking cessation research among SLWH. Such flexible platforms for treatment delivery may have greater potential to reach and impact SLWH, which constitutes an underserved, harder-to-reach population. By providing a remote means of care, our study may be able to assess and assist a larger group of SLWH and remove potential barriers to treatment access – money needed to commute into the office or the need to take time off from work to attend appointments.

One notable limitation of our study is use of the nicotine patch alone. This decision was made as inclusion of a short-term NRT may undermine the function of the behavioral experiments (i.e., to move through the craving/urge without smoking) taught in the QUIT condition as participants may be included to use a short-term NRT when experiencing withdrawal instead of ‘surfing the urge.’ Yet, some research would suggest that use of combination/dual NRT (e.g., long-acting nicotine patches along with short-term gum or lozenges) is more efficacious in cessation success than single NRT; however, the level of behavioral support in these studies was variable.30 Given limited research on both combination therapies and level of therapeutic/behavioral support, more research should be conducted to determine the type(s) of NRT that would be useful in the context of smoking cessation with this strength of behavioral support. Additionally, one of our primary outcomes of this trial is cost-effectiveness, which could become skewed by dual NRT.84 As such, future trials would benefit from an analysis of the cost-to-benefit ratio of dual NRT contrasted with single NRT.

Ultimately, the goal of the present study is to help SLWH stop smoking, which should decrease smoking-related morbidity and mortality in SWLH. We aim to fill a void surrounding smoking cessation RCTs by helping to develop a standardized treatment that could be modeled within many communities outside of Boston and Houston to allow for a more extensive treatment plan. By addressing comorbid anxiety and depressive symptoms driving poor cessation outcomes, we hope that our treatment plan will not only help SLWH quit smoking, but also ensure that they maintain abstinence.

Acknowledgements.

Funding for this project came from the National Institute on Drug Abuse R01 DA047933 (O’Cleirigh, Smits, Zvolensky; ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03904186). The National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institutes of Health, and the Department of Veterans Affairs had no role in the writing of the report or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Hile SJ, Feldman MB, Alexy ER, Irvine MK. Recent Tobacco Smoking is Associated with Poor HIV Medical Outcomes Among HIV-Infected Individuals in New York. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(8):1722–1729. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1273-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Substance Use Disorders and HIV | Special Patient Populations | Adult and Adolescent ARV | ClinicalInfo. Published July 10, 2019. Accessed February 7, 2021. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-arv/substance-use-disorders-and-hiv?view=full

- 3.Helleberg M, Afzal S, Kronborg G, et al. Mortality Attributable to Smoking Among HIV-1–Infected Individuals: A Nationwide, Population-Based Cohort Study. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2013;56(5):727–734. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helleberg M, May MT, Ingle SM, et al. Smoking and life expectancy among HIV-infected individuals on antiretroviral therapy in Europe and North America. AIDS. 2015;29(2):221–229. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy KP, Parker RA, Losina E, et al. Impact of Cigarette Smoking and Smoking Cessation on Life Expectancy Among People With HIV: A US-Based Modeling Study. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(11):1672–1681. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frazier EL, Sutton MY, Brooks JT, Shouse RL, Weiser J. Trends in cigarette smoking among adults with HIV compared with the general adult population, United States - 2009–2014. Prev Med. 2018;111:231–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cropsey KL, Hendricks PS, Jardin B. A pilot study of screening, brief intervention, and referral for treatment (SBIRT) in non-treatment seeking smokers with HIV. Addictive behaviors. 2013;38(10):2541–2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tseng T-Y, Krebs P, Schoenthaler A. Combining text messaging and telephone counseling to increase varenicline adherence and smoking abstinence among cigarette smokers living with HIV: a randomized controlled study. AIDS and Behavior. 2017;21(7):1964–1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vidrine DJ, Marks RM, Arduino RC, Gritz ER. Efficacy of cell phone–delivered smoking cessation counseling for persons living with HIV/AIDS: 3-month outcomes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2011;14(1):106–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humfleet GL, Hall SM, Delucchi KL, Dilley JW. A randomized clinical trial of smoking cessation treatments provided in HIV clinical care settings. nicotine & tobacco research. 2013;15(8):1436–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manuel JK, Lum PJ, Hengl NS, Sorensen JL. Smoking cessation interventions with female smokers living with HIV/AIDS: a randomized pilot study of motivational interviewing. AIDS care. 2013;25(7):820–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moadel AB, Bernstein SL, Mermelstein RJ, Arnsten JH, Dolce EH, Shuter J. A randomized controlled trial of a tailored group smoking cessation intervention for HIV-infected smokers. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 1999;2012;61(2):208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shuter J, Morales DA, Considine-Dunn SE, An LC, Stanton CA. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a web-based smoking cessation intervention for HIV-infected smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 1999;2014;67(1):59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lloyd‐Richardson EE, Stanton CA, Papandonatos GD. Motivation and patch treatment for HIV+ smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2009;104(11):1891–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingersoll KS, Cropsey KL, Heckman CJ. A test of motivational plus nicotine replacement interventions for HIV positive smokers. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(3):545–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ziedonis D, Hitsman B, Beckham JC, et al. Tobacco use and cessation in psychiatric disorders: National Institute of Mental Health report. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(12):1691–1715. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zvolensky MJ, Jardin C, Wall MM. Psychological distress among smokers in the United States: 2008–2014. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2018;20(6):707–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandt C, Zvolensky MJ, Woods SP, Gonzalez A, Safren SA, O’Cleirigh CM. Anxiety symptoms and disorders among adults living with HIV and AIDS: A critical review and integrative synthesis of the empirical literature. Clinical psychology review. 2017;51:164–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shacham E, Morgan J, Önen NF, Taniguchi T, Overton ET. Screening Anxiety in the HIV Clinic. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2407–2413. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0238-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gritz ER, Danysh HE, Fletcher FE. Long-term outcomes of a cell phone–delivered intervention for smokers living with HIV/AIDS. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2013;57(4):608–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mykletun A, Overland S, Aarø LE, Liabø H-M, Stewart R. Smoking in relation to anxiety and depression: evidence from a large population survey: the HUNT study. European Psychiatry. 2008;23(2):77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor S, Zvolensky MJ, Cox BJ. Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: development and initial validation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3. Psychological assessment. 2007;19(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leventhal AM, Zvolensky MJ. Anxiety, depression, and cigarette smoking: a transdiagnostic vulnerability framework to understanding emotion-smoking comorbidity. Psychological bulletin. 2015;141(1):176–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labbe AK, Wilner JG, Kosiba JD, et al. Demonstration of an Integrated Treatment for Smoking Cessation and Anxiety Symptoms in People With HIV: A Clinical Case Study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2017;24(2):200–214. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2016.03.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Cleirigh C, Zvolensky MJ, Smits JAJ, et al. Integrated Treatment for Smoking Cessation, Anxiety, and Depressed Mood in People Living With HIV: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2018;79(2):261–268. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magidson JF, Skeer MR, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Prevalence of psychiatric and substance abuse symptomatology among HIV-infected gay and bisexual men in HIV primary care. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(5):470–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smits JA, Zvolensky MJ, Davis ML. The efficacy of vigorous-intensity exercise as an aid to smoking cessation in adults with high anxiety sensitivity: A randomized controlled trial. Psychosomatic medicine. 2016;78(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NOT-OD-16–094: Final NIH Policy on the Use of a Single Institutional Review Board for Multi-Site Research. Accessed February 13, 2021. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-16-094.html

- 30.Patnode CD, Henderson JT, Melnikow J, Coppola EL, Durbin S, Thomas R. Chapter 4: Discussion. In: Interventions for Tobacco Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Women: An Evidence Update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2021. Accessed February 7, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567068/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. Accessed December 1, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=074612

- 32.MacPherson L, Tull MT, Matusiewicz AK. Randomized controlled trial of behavioral activation smoking cessation treatment for smokers with elevated depressive symptoms. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2010;78(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiore M Treating tobacco use and dependence. Health and Human Services Department. Published online 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zvolensky MJ, Garey L, Kauffman BY, Manning K. Integrative treatment program for anxiety sensitivity and smoking cessation. The Clinician’s Guide to Anxiety Sensitivity Treatment and Assessment: Elsevier. 2019:101–120. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zvolensky MJ, Garey L, Allan NP. Effects of anxiety sensitivity reduction on smoking abstinence: An analysis from a panic prevention program. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2018;86(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown RA, Palm Reed KM, Bloom EL. A randomized controlled trial of distress tolerance treatment for smoking cessation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2018;32(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fagerström K Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerstrom Test for Cigarette Dependence. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2012;14(1):75–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(1):180–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Association AP. DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition. Generic; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacob P, Hatsukami D, Severson H, Hall S, Yu L, Benowitz NL. Anabasine and anatabine as biomarkers for tobacco use during nicotine replacement therapy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(12):1668–1673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hecht J, Rigotti NA, Minami H, et al. Adaptation of a Sustained Care Cessation Intervention for Smokers Hospitalized for Psychiatric Disorders: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2019;83:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2019.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.NicConfirmTM Instant Nicotine Saliva Test Kit | Saliva Test for Nicotine. Confirm BioSciences. Published June 26, 2018. Accessed October 26, 2020. https://www.confirmbiosciences.com/products/nicotine-tobacco-tests/nicconfirm-instant-cotinine-test-kit/

- 43.Suh-Lailam BB, Haglock-Adler CJ, Carlisle HJ, Ohman T, McMillin GA. Reference interval determination for anabasine: a biomarker of active tobacco use. J Anal Toxicol. 2014;38(7):416–420. doi: 10.1093/jat/bku059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moyer TP, Charlson JR, Enger RJ, et al. Simultaneous analysis of nicotine, nicotine metabolites, and tobacco alkaloids in serum or urine by tandem mass spectrometry, with clinically relevant metabolic profiles. Clin Chem. 2002;48(9):1460–1471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, Miller IW. Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998;12(2). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blankers M, Smit ES, Pol P, Vries H, Hoving C, Laar M. The missing= smoking assumption: a fallacy in internet-based smoking cessation trials? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2016;18(1):25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Jama. 2016;316(10):1093–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Euroquol Research Foundation. EQ-5D-3L User Guide; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zvolensky MJ, Garey L, Fergus TA. Refinement of anxiety sensitivity measurement: The Short Scale Anxiety Sensitivity Index (SSASI. Psychiatry research. 2018;269:549–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Simons JS, Gaher RM. The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motivation and emotion. 2005;29(2):83–102. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Snaith RP, Hamilton M, Morley S, Humayan A, Hargreaves D, Trigwell P. A scale for the assessment of hedonic tone the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(1):99–103. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.1.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.E G. EQ-5D-5L Valuation. Accessed; 2017. https://euroqol.org/wp-content/uploads/

- 53.Wu AW, Hays RD, Kelly S, Malitz F, Bozzette SA. Applications of the Medical Outcomes Study health-related quality of life measures in HIV/AIDS. Quality of Life Research. 1997;6(6):531–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu M, Safren SA, Skolnik PR. Optimal recall period and response task for self-reported HIV medication adherence. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12(1):86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smit ES, Evers SM, Vries H, Hoving C. Cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of Internet-based computer tailoring for smoking cessation. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2013;15(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vogl M, Wenig CM, Leidl R, Pokhrel S. Smoking and health-related quality of life in English general population: implications for economic evaluations. BMC public health. 2012;12(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tran BX, Ohinmaa A, Nguyen LT. Quality of life profile and psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L in HIV/AIDS patients. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2012;10(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.NADAC (National Average Drug Acquisition Cost) | Data.Medicaid.gov. Accessed December 1, 2020. https://data.medicaid.gov/Drug-Pricing-and-Payment/NADAC-National-Average-Drug-Acquisition-Cost-/a4y5-998d

- 59.VA Drug Pricing Database | Department of Veterans Affairs Open Data Portal. Accessed December 1, 2020. https://www.data.va.gov/dataset/VA-Drug-Pricing-Database/pu94-4asd

- 60.Introduction to RED BOOK Online. http://www.micromedexsolutions.com/micromedex2/4.34.0/WebHelp/RED_BOOK/Introduction_to_REDB_BOO

- 61.Fishman PA, Thompson EE, Merikle E, Curry SJ. Changes in health care costs before and after smoking cessation. Nicotine & tobacco research. 2006;8(3):393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Musich S, Faruzzi SD, Lu C, McDonald T, Hirschland D, Edington DW. Pattern of medical charges after quitting smoking among those with and without arthritis, allergies, or back pain. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2003;18(2):133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fee Schedules - General Information | CMS. Accessed October 26, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/FeeScheduleGenInfo/index

- 64.Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2015/median-weekly-earnings-

- 65.Gonzalez A, Barinas J, O’Cleirigh C. Substance use: impact on adherence and HIV medical treatment. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8(4):223–234. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0093-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.O’Cleirigh C, Valentine SE, Pinkston M, et al. The unique challenges facing HIV-positive patients who smoke cigarettes: HIV viremia, art adherence, engagement in HIV care, and concurrent substance use. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(1):178–185. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0762-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ghura S, Gross R, Jordan-Sciutto K, et al. Bidirectional Associations among Nicotine and Tobacco Smoke, NeuroHIV, and Antiretroviral Therapy. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2020;15(4):694–714. doi: 10.1007/s11481-019-09897-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilson IB, Lee Y, Michaud J, Fowler FJ, Rogers WH. Validation of a New Three-Item Self-Report Measure for Medication Adherence. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(11):2700–2708. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1406-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]