Abstract

Purpose:

To assess long-term quality of life (QoL) in patients with sustained biochemical control of acromegaly, comparing those receiving vs not receiving pharmacotherapy (primary analysis); to assess change in QoL over time (secondary analysis).

Methods:

Cross-sectional study, with a secondary longitudinal component, of 58 patients with biochemically controlled acromegaly. All had participated in studies assessing QoL years previously, after having undergone surgery ± radiotherapy. One cohort received medical therapy [MED (n=33)]; the other did not [NO-MED (n=25)]. QoL was assessed by the 36-Item-Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), Acromegaly Quality of Life Questionnaire (AcroQoL), Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI), Symptom Questionnaire, and QoL-Assessment of Growth Hormone Deficiency in Adults (QoL-AGHDA).

Results:

Mean (±SD) duration of biochemical control was 15.0 ± 6.4 years for MED and 20.4 ± 8.2 years for NO-MED (p=0.007). 58% of subjects scored <25% of normal on ≥1 SF-36 domain and 32% scored <25% of normal on ≥4 of 8 domains. Comparing MED vs NO-MED and controlling for duration of biochemical control, there were no significant differences in QoL by SF-36, AcroQOL, GIQLI, Symptom Questionnaire, or QoL-AGHDA. Growth hormone deficiency (GHD) but not radiotherapy predicted poorer QoL. In MED, QoL improved over time in three AcroQoL domains and two GIQLI domains. In NO-MED, QoL worsened in two SF-36 domains and two Symptom Questionnaire domains; QoL-AGHDA scores also worsened in subjects with GHD.

Conclusion:

A history of acromegaly and development of GHD, but not pharmacologic or radiotherapy, are detrimental to QoL, which remains poor over the long-term despite biochemical control.

Keywords: Acromegaly, quality of life, growth hormone deficiency, radiation therapy

Introduction

Growth hormone (GH) excess in acromegaly is associated with impaired quality of life (QoL) [1, 2], which improves following surgery, radiation therapy, and/or pharmacologic treatment [3–6]. However, in studies up to 15 years following acromegaly remission, QoL does not normalize [7–10]. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated improvement in many acromegaly-related symptoms (e.g., fatigue, headache, and hyperhidrosis) and health-related QoL following treatment [6], but comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and arthropathy persist or may even progress [11]. Treatment modality may be an important determinant of QoL in patients with acromegaly. Some, but not all, studies show that radiation therapy [9, 12–15] and somatostatin analog use [13, 16, 17] negatively affect QoL, although it is difficult to account for differences in disease severity of patients who require further treatment for acromegaly after surgery. Additionally, GH deficiency (GHD) can occur in patients treated for acromegaly, and our group demonstrated in a cross-sectional study that patients with GHD after cure of acromegaly have poorer QoL than those who are GH sufficient [15].

There are few studies describing the long-term trajectory of QoL in patients with acromegaly who remain in remission. Many patients require pharmacotherapy for persistent disease after surgery [18], and an important question is whether sustained dependence on pharmacotherapy negatively impacts QoL, which might be expected given medication side effects and the burden of chronic medication use. Additionally, an understanding of whether factors such as history of radiation therapy, GH status, and hypopituitarism affect QoL in patients with long-term sustained biochemical control has not been investigated and could inform patient and provider expectations, choice of therapies, and goals of care.

In this study, we compared QoL in patients with acromegaly biochemically controlled on pharmacotherapy following surgery +/− radiation treatment (MED) to patients not requiring pharmacotherapy after surgery +/− radiation (NO-MED) (some of whom developed GHD). We also investigated determinants of long-term QoL; the overall mean duration of biochemical control was 17 years but ranged from 5–48 years. We hypothesized that QoL would be lower in patients receiving pharmacotherapy than those cured by surgery +/− radiation and that radiation therapy and GHD would independently predict impaired QoL for all patients. As a secondary analysis, we compared current QoL scores to those obtained 5–14 years prior to assess whether QoL changes over time in patients with sustained biochemical control. We hypothesized that QoL would improve but remain poor in the long-term.

Methods

Subjects

We assessed QoL in 58 subjects with biochemically controlled acromegaly (defined as normal serum IGF-1 level). Thirty-three subjects had undergone surgery +/− radiation but required pharmacologic treatment for biochemical control (MED cohort); subjects were treated with somatostatin analog (octreotide LAR or lanreotide depot) monotherapy (n=21) or GH receptor antagonist (pegvisomant) monotherapy (n=12) [19]. Twenty-five subjects comprised the second group and were definitively treated by surgery +/− radiation therapy (NO-MED cohort) [15].

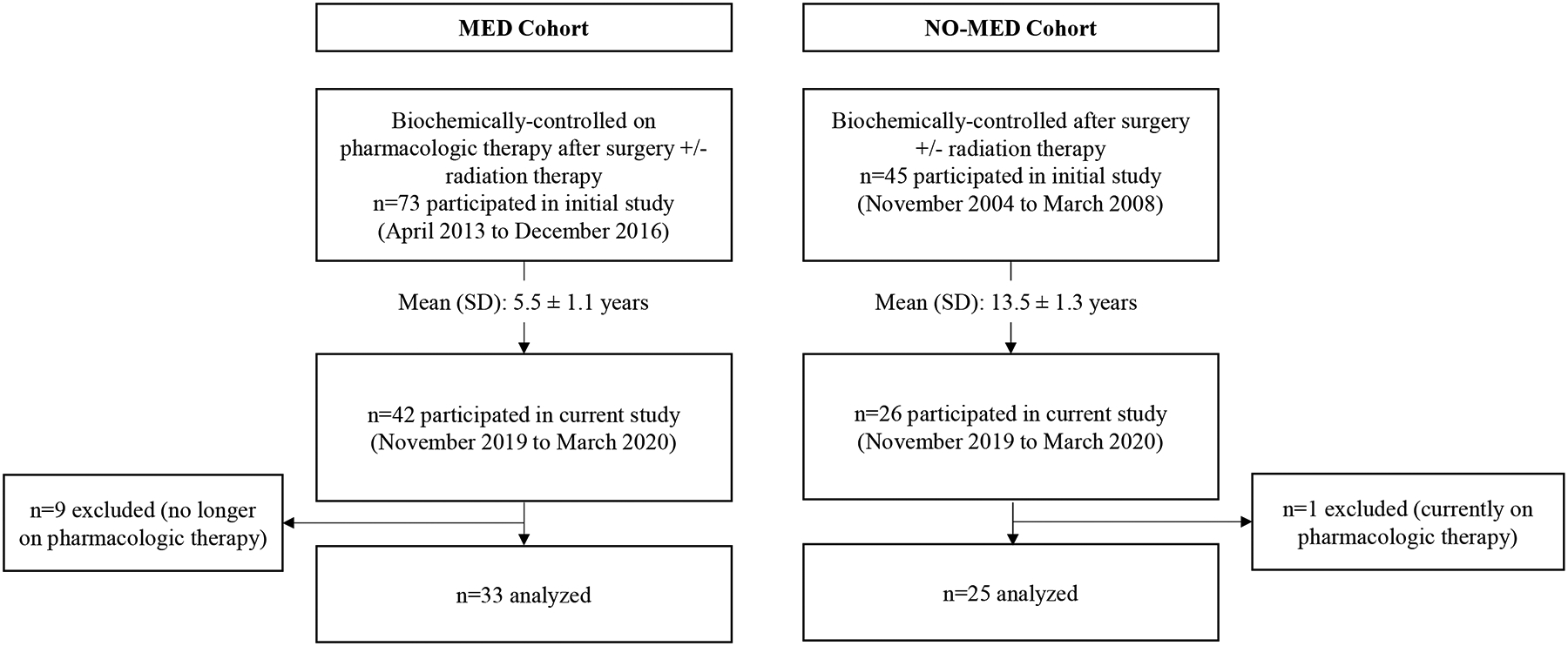

One hundred eighteen subjects who had participated in two cross-sectional studies in which QoL scores were assessed [15, 19] were invited by mail to participate in this study, 58% (n=68) of whom returned completed questionnaires. As shown in Figure 1, nine subjects in MED were excluded because they were no longer on pharmacologic treatment for acromegaly. One subject in NO-MED was excluded because he was taking a somatostatin analog and pegvisomant. QoL was reassessed following a mean ± SD of 5.5 ± 1.1 years (range 3–7 years) for MED and 13.5 ± 1.3 years (range 12–15 years) for NO-MED. Our primary analysis compared QoL scores between those patients who were and were not receiving medications for biochemical control of acromegaly. As a secondary analysis, we assessed changes in QoL over time, when possible.

Figure 1.

Study design.

The percentage of subjects who responded to the study invitation was similar in MED (58%) vs NO-MED (53%) (p=0.66). Age, gender, GHD, and history of radiation therapy were similar in study participants vs nonparticipants.

Protocol

QoL was evaluated by the following self-administered questionnaires:

36-Item-Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): a well-validated QoL questionnaire that addresses physical and psychological well-being during the preceding four weeks. The following domains are assessed: 1) physical functioning, 2) role limitations due to physical functioning, 3) general health perception, 4) pain, 5) energy/fatigue, 6) emotional well-being, 7) role limitations due to emotional health, and 8) social functioning, and a physical component summary score and mental health component summary score are calculated [20]. Higher scores indicate better QoL.

Acromegaly QoL Questionnaire (AcroQoL): a disease-generated validated questionnaire that specifically targets QoL symptoms characteristic of acromegaly. The following domains are assessed: 1) physical, 2) psychological, 3) appearance, and 4) personal relationships, and a global score is calculated [21]. Higher scores indicate better QoL.

Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI): a well-validated questionnaire designed to capture GI symptoms. The following domains are assessed: 1) physical function, 2) social function, 3) emotions, 4) GI symptoms, and 5) medical treatment [22]. Higher scores indicate better QoL.

Symptom Questionnaire: a well-validated questionnaire assessing 1) anxiety, 2) depression, 3) somatic symptoms, and 4) anger/hostility [23]. Higher scores indicate greater symptom severity.

QoL-Assessment of Growth Hormone Deficiency in Adults (QoL-AGHDA): a disease-generated questionnaire designed to evaluate QoL in adult patients with GHD [24]. A higher score indicates worse QoL.

In addition to assessing long-term QoL, data were compared to those obtained in the original cross-sectional studies to assess change in QoL over time (secondary analysis). Subjects in MED had previously completed SF-36, AcroQoL, and GIQLI. Subjects in NO-MED had previously completed SF-36, Symptom Questionnaire, and QoL-AGHDA. For any one domain or composite score, scores were considered missing if greater than 50% of answers were left blank.

Clinical characteristics and QoL scores from initial assessment were published in the parent studies [15, 19], but QoL scores at reassessment have not been reported. Acromegaly treatment history, past medical history, hormonal deficiencies and hormone replacement therapies, and most recent IGF-1 level were determined through a patient questionnaire and review of primary endocrine provider notes and medication lists. GHD had previously been assessed and published in NO-MED [15]. The study was approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in JMP Statistical Database Software (version Pro 14.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Two-sample T tests were performed for two-way comparisons. Changes in QoL from initial assessment to reassessment were determined using paired T tests. Multivariate ANCOVA models were constructed to determine predictors of QoL. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were determined for univariate correlations. Statistical significance was set as two-tailed p-value <0.05.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Demographics, treatment history, pituitary hormone status, and medical comorbidities are reported by cohort in Table 1. There were no differences in mean ± SD age (63 ± 12 years), gender (67% female), BMI (30 ± 7 kg/m2), and race (93% white) between MED and NO-MED. Mean duration of biochemical control was 15.0 ± 6.4 years for MED vs 20.4 ± 8.2 years for NO-MED (p=0.007). There were no differences in tumor size or IGF-1 level at diagnosis between MED and NO-MED. Thirty percent of subjects in MED underwent radiation treatment vs 48% for NO-MED (p=0.19). In MED, n=21 (64%) were on somatostatin analog monotherapy and n=12 (36%) were on pegvisomant monotherapy.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics.

| MED (n=33) | NO-MED (n=25) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 62.9 ± 12.6 | 62.3 ± 11.1 | 0.84 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.6 ± 5.8 | 30.9 ± 9.1 | 0.51 |

| Female gender (n,%) | 23 (70) | 16 (64) | 0.78 |

| Caucasian (n,%) | 31 (94) | 23 (92) | 1.00 |

| Acromegaly-related variables | |||

| Duration of biochemical control (years) | 15.0 ± 6.4 | 20.4 ± 8.2 | 0.007 |

| Tumor size at diagnosis (cm) | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 0.53 |

| IGF-1 level at diagnosis (ng/mL) | 958 ± 449 | 678 ± 187 | 0.10 |

| Transsphenoidal surgery (n,%) | 33 (100) | 25 (100) | 1.00 |

| Radiation (n,%) | 10 (30) | 12 (48) | 0.19 |

| SSA use (n,%) | 21 (64) | N/A | |

| GH receptor antagonist use (n,%) | 12 (36) | N/A | |

| Current IGF-1 index | 1.06 ± 0.34 | 0.79 ± 0.38 | 0.03 |

| Pituitary hormone status | |||

| ≥1 pituitary hormone deficiency | 19 (58) | 19 (76) | 0.17 |

| Hypothyroidism (n,%) | 17 (52) | 14 (56) | 0.79 |

| Adrenal insufficiency (n,%) | 4 (12) | 9 (36) | 0.05 |

| Growth hormone deficiency (n,%) | N/A | 11 (44) | |

| Growth hormone replacement (n,%) | N/A | 2 (18) | |

| Male hypogonadism (n,%) | 4 (40) | 5 (56) | 0.66 |

| Testosterone replacement (n,%) | 4 (100) | 4 (80) | |

| Menopausal (n,%) | 16 (70) | 12 (75) | 1.00 |

| Estrogen replacement (n,%) | 1 (6) | 1 (8) | |

| Female hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (n,%) | 6 (26) | 4 (25) | 1.00 |

| Estrogen replacement (n,%) | 4 (67) | 2 (50) | |

| Diabetes insipidus (n,%) | 0 | 1 (4) | 0.18 |

| Medical comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes mellitus (n,%) | 10 (30) | 2 (8) | 0.05 |

| Hypertension (n,%) | 16 (48) | 11 (44) | 0.79 |

| Depression (n,%) | 10 (30) | 5 (20) | 0.55 |

| History of cancer (n,%) | 8 (24) | 6 (24) | 1.00 |

| Osteoporosis (n,%) | 9 (0.27) | 9 (0.36) | 0.77 |

| Joint replacement (n,%) | 8 (0.24) | 9 (0.36) | 0.39 |

Values reported as mean ± SD. MED underwent surgery ± radiation but required long-term somatostatin analog or growth hormone receptor antagonist monotherapy. NO-MED were in remission after surgery ± radiation. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SSA, somatostatin analog; GH, growth hormone; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1. IGF-1 index defined as IGF-1 level divided by mean normal range for age. Growth hormone deficiency had previously been assessed in NO-MED group only.

Fifty eight percent of MED and 76% of NO-MED had at least one pituitary hormone deficiency (p=0.17). There was a trend toward higher prevalence of adrenal insufficiency in NO-MED vs MED (36% vs 12%, p=0.05); prevalence of hypothyroidism, hypogonadism, and diabetes insipidus was similar between groups (Table 1). Mean IGF-1 index (IGF-1 level/mean normal range) was higher in MED vs NO-MED (1.06 ± 0.34 vs 0.79 ± 0.38, p=0.03). GHD was assessed in the NO-MED cohort only; n=11 (44%) had GHD, of which n=2 were on GH replacement. No patients in MED had an IGF-1 level less than the lower limit of normal. There was a trend toward higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus in MED vs NO-MED (30% vs 8%, p=0.05); only one subject was on insulin. There were no differences between groups in prevalence of hypertension, depression, cancer, osteoporosis, or joint replacement (Table 1).

QoL comparison between subjects receiving and not receiving pharmacotherapy

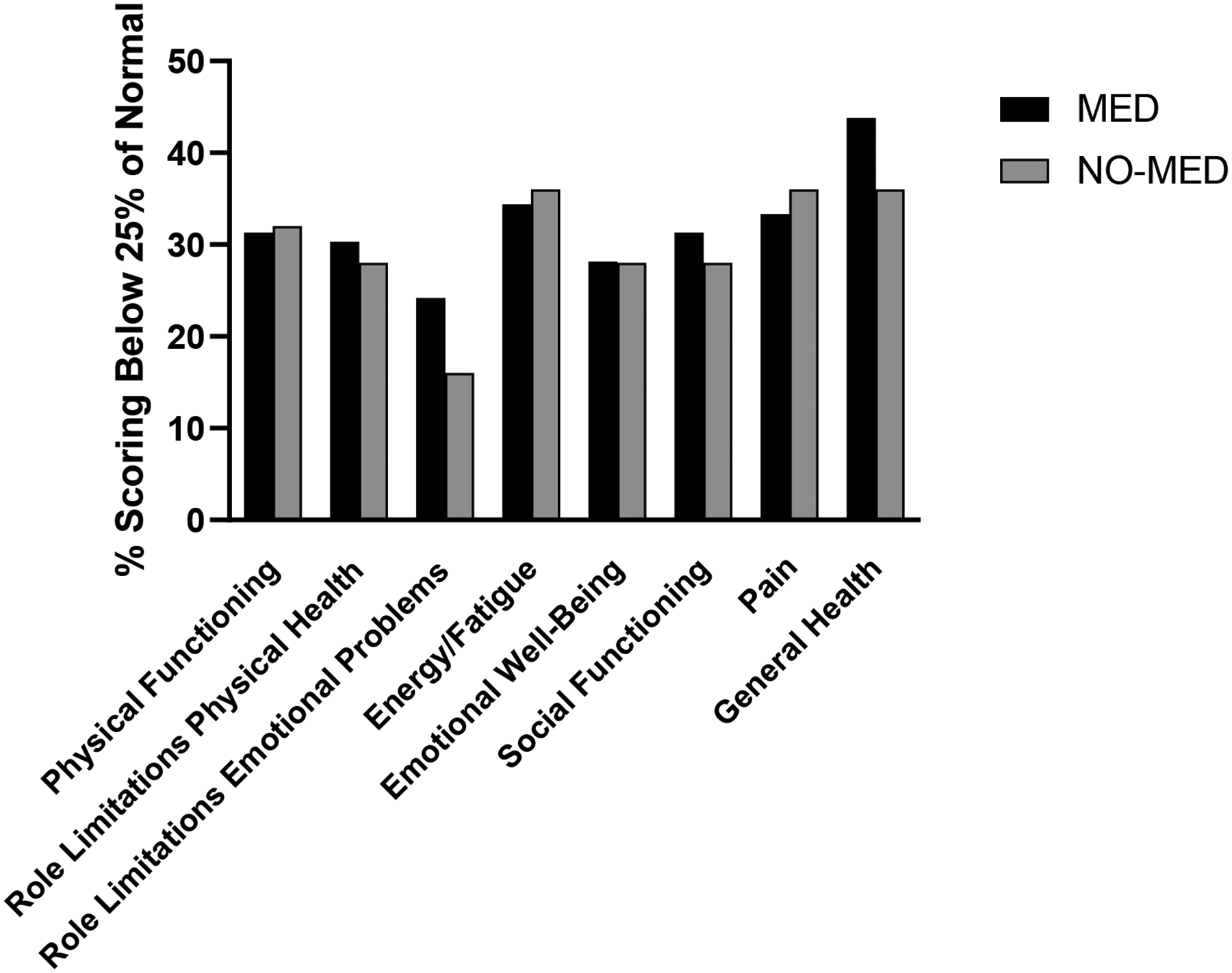

Fifty-three percent of MED subjects and 64% of NO-MED subjects scored in the lowest quartile (<25%) of normal for age on at least one SF-36 domain (p=0.43). Thirty-eight percent of MED subjects and 24% of NO-MED subjects scored in the lowest quartile of normal for age on 50% or more SF-36 domains (p=0.39). For all SF-36 domains, the percentage of subjects scoring in the lowest quartile of normal for age was similar between MED and NO-MED (Figure 2), even after controlling for differences in duration of biochemical control, IGF-1 index, presence of adrenal insufficiency, and presence of diabetes mellitus.

Figure 2.

The percentage of subjects scoring in the lowest quartile (<25%) of normal for age was similar between MED and NO-MED for all eight SF-36 domains.

There was a trend towards lower QoL scores on the AcroQoL Psychological and Appearance domains in MED subjects compared to NO-MED subjects (Table 2) that became nonsignificant after controlling for differences between groups in duration of biochemical control, IGF-1 index, presence of adrenal insufficiency, and presence of diabetes mellitus. There were no significant differences in QoL by the other AcroQOL domains or by GIQLI, Symptom Questionnaire, or QoL-AGHDA in MED vs NO-MED (Table 2); findings did not change after controlling for duration of biochemical control, IGF-1 index, presence of adrenal insufficiency, and presence of diabetes mellitus.

Table 2.

Quality of life scores.

| MED (n=33) | NO-MED (n=25) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AcroQoL | |||

| Physical | 70.4 ± 22.3 | 70.9 ± 17.8 | 0.93 |

| Psychological | 67.8 ± 17.9 | 76.1 ± 15.0 | 0.07 |

| Appearance | 60.2 ± 20.2 | 69.0 ± 18.2 | 0.09 |

| Personal Relations | 75.5 ± 18.0 | 83.1 ± 15.1 | 0.10 |

| Global Score | 60.8 ± 23.5 | 67.3 ± 19.4 | 0.27 |

| Symptom Questionnaire | |||

| Depression | 4.78 ± 5.28 | 5.48 ± 5.99 | 0.64 |

| Anxiety | 5.19 ± 5.53 | 4.52 ± 4.79 | 0.63 |

| Somatic | 8.75 ± 5.64 | 8.12 ± 4.91 | 0.66 |

| Anxiety-Hostility | 2.63 ± 4.00 | 3.44 ± 3.91 | 0.44 |

| QoL-AGHDA | 6.52 ± 5.84 | 8.52 ± 6.70 | 0.23 |

| GIQLI | |||

| Symptoms | 3.40 ± 0.48 | 3.46 ± 0.43 | 0.63 |

| Physical State | 2.91 ± 0.90 | 2.87 ± 0.84 | 0.87 |

| Emotions | 3.07 ± 0.80 | 3.07 ± 0.84 | 0.99 |

| Social Functioning | 2.82 ± 0.95 | 3.00 ± 1.06 | 0.51 |

| Medical Treatment | 3.27 ± 0.91 | 3.56 ± 0.87 | 0.23 |

| Total Score | 110 ± 21 | 112 ± 21 | 0.73 |

Values reported as mean ± SD. MED underwent surgery ± radiation but required somatostatin analog or growth hormone receptor antagonist monotherapy. NO-MED were in remission after surgery ± radiation. There remained no significant differences between MED and SURG after controlling for duration of biochemical control, IGF-1 index, radiation therapy, hypopituitarism, and IGF-1 level at diagnosis. Abbreviations: AcroQoL, Acromegaly Quality of Life Questionnaire; QoL-AGHDA, QoL-Assessment of Growth Hormone Deficiency in Adults; GIQLI, Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index.

Determinants of long-term QoL

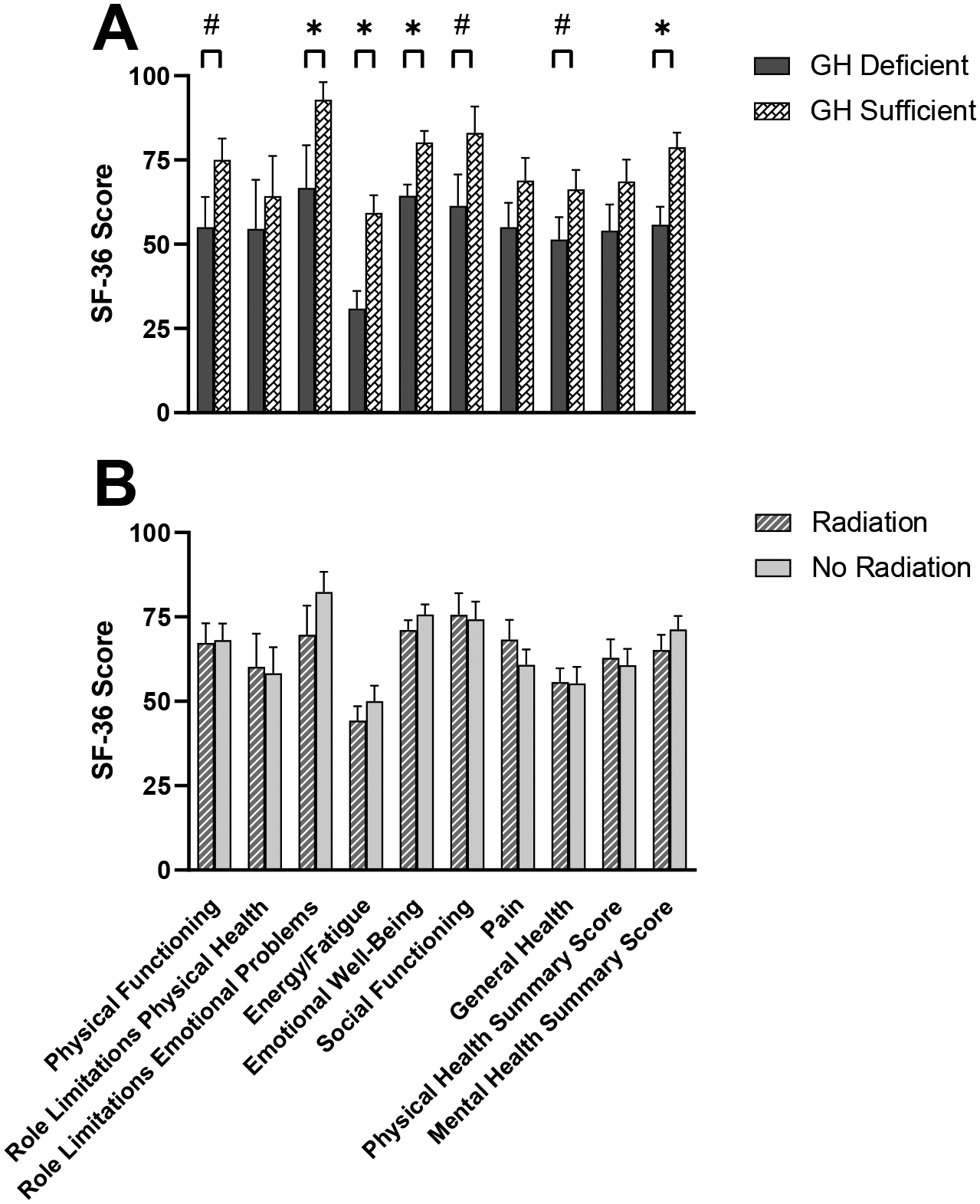

GHD in the cohort for whom data were available (NO-MED) was associated with lower SF-36 scores on three domains and one summary score, and there was a trend towards lower SF-36 scores on three additional domains (Figure 3A). Findings were similar after excluding the two subjects receiving GH replacement. Seven of the 11 subjects with GHD had received radiation treatment. Radiation treatment was not associated with lower SF-36 scores in MED or NO-MED (when analyzed individually) or in all subjects combined (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

A) Growth hormone (GH) deficiency in the cohort for whom data were available (NO-MED) was associated with lower mean SF-36 scores on three domains (Role Limitations due to Emotional Problems, Energy, Emotional Well-Being) and one summary score (Mental Health). There was a trend towards lower mean SF-36 scores on three additional domains (Physical Functioning, Social Functioning, General Health). B) Mean SF-36 scores were similar in subjects treated with radiation therapy compared to subjects not treated with radiation. Data graphed are for MED and NO-MED subjects combined, but results were similar when analyzing MED and NO-MED groups individually. Higher scores on SF-36 correspond to better quality of life. *p<0.05. #0.05<p<0.1. Error bars indicate SEM.

In total, GHD was associated with lower QoL on 15 of 26 domains (including the SF-36 domains reported above). When comparing subjects with GHD receiving GH replacement (n=2) vs not receiving GH replacement (n=9), those receiving GH replacement had better QoL on the Depression domain of the Symptom questionnaire (1.5 ± 2.1 vs 10.9 ± 5.3, p=0.04); otherwise, there were no differences in QoL scores between groups. A higher number of pituitary hormone deficiencies was inversely associated with QoL on 11 of 26 domains, and hypothyroidism was associated with lower QoL on 9 of 26 domains. There was a positive correlation between IGF-1 index and QoL on 7 of 26 domains. Female sex was associated with lower QoL on 2 of 26 domains, while radiation treatment, adrenal insufficiency, hypogonadism, and duration of biochemical control were not associated with QoL by any domain. Joint replacement was associated with lower QoL on 4 SF-36 domains (Physical Functioning, Role Limitations due to Physical Health, Social Functioning, and Pain).

In MED, there were no differences in QoL in subjects receiving treatment with a somatostatin analog vs pegvisomant.

Changes in QoL in MED cohort

As a secondary analysis, we examined change over time in QoL where possible. In the MED cohort, QoL in three AcroQoL domains improved over time, and there was a trend toward improvement in the fourth domain (listed first are mean scores at reassessment followed by mean scores at initial assessment): Physical [70 ± 22 (SD) vs 60 ± 24, p<0.0001], Psychological (68 ± 18 vs 60 ± 22, p=0.0002), Appearance (60 ± 20 vs 50 ± 24, p<0.0001), and Personal Relations (75 ± 18 vs 70 ± 22, p=0.06). There was no change in the AcroQoL global score (61 ± 23 vs 60 ± 21, p=0.97). QoL improved in two GIQLI domains, Physical State (2.9 ± 0.9 vs 2.1 ± 1.0, p<0.0001) and Emotions (3.1 ± 0.8 vs 2.9 ± 0.8, p=0.02). There was no change in QoL in the other GIQLI domains (Symptoms, Social Functioning, Medical Treatment) or in any SF-36 domain.

Changes in QoL in NO-MED cohort

In the NO-MED cohort, QoL declined on one SF-36 domain and one summary score, and there was a trend towards a decline in QoL on two additional SF-36 domains (listed first are mean scores at reassessment followed by mean scores at initial assessment): Pain [63 ± 25 (SD) vs 80 ± 24, p=0.003], Physical Health Summary Score (62 ± 26 vs 76 ± 19, p=0.02), Role Limitations due to Physical Health (60 ± 46 vs 82 ± 31, p=0.05), and Social Functioning (74 ± 32 vs 85 ± 18, p=0.07). There were no significant changes in QoL by the other six SF-36 domains or the Mental Health Summary Score. QoL worsened on two Symptom Questionnaire domains, Depression (5.5 ± 5.6 vs 2.9 ± 4.1, p=0.003) and Somatic (8.1 ± 4.9 vs 5.3 ± 4.0, p=0.02), and did not change in the Anxiety and Anxiety-Hostility domains. There was a trend towards worsened QoL on QoL-AGHDA (8.5 ± 6.7 vs 6.5 ± 6.0, p=0.08), which became significant after controlling for GHD (scores worsened significantly in the subjects with GHD compared to GH sufficient).

Discussion

This study assessed whether QoL differs in acromegaly subjects requiring pharmacotherapy for biochemical control following surgery +/− radiation treatment to those cured by surgery +/− radiotherapy. As a secondary analysis, change in QoL over time in subjects with sustained biochemical control was evaluated. There were no differences in any QoL scores, including the disease-specific AcroQoL, between subjects receiving or not receiving pharmacotherapy. Moreover, some acromegaly-specific QoL domains improved in subjects treated pharmacologically, while other QoL domains worsened in subjects cured by surgery +/− radiation therapy. QoL by SF-36 remained poor in treated acromegaly subjects compared to age-matched controls, a finding that is consistent with previously published studies [1, 7]. Furthermore, the presence of GHD and hypothyroidism predicted poorer long-term QoL, while radiation treatment did not negatively affect QoL. That QoL was not lower in patients requiring chronic pharmacologic treatment, as might be expected given factors such as medication side effects, the burden of chronic medication, and greater severity of disease, was notable and unexpected. Our findings elevate pharmacologic therapy as an option for long-term treatment of acromegaly in patients not cured by surgery.

The main aim of this study was to investigate QoL in patients with long-term biochemical control of acromegaly, and specifically whether chronic pharmacologic therapy is an important contributor to QoL. Many patients with acromegaly require multimodal treatment with medication and/or radiation following surgery [18], and we have demonstrated that long-term pharmacologic treatment (average of 15 years in this study) does not adversely affect QoL compared to patients also treated by surgery +/− radiation treatment but not requiring pharmacologic treatment. These data support a recently published study by Arshad et al., which showed that patients have a comparable QoL, if not better QoL in some physical domains, when biochemically controlled by medical therapy following surgery (n=18) than cured by surgery (n=32) [25]. Subjects had a mean duration of disease of 11.9 years (medical group) and 9.9 years (surgical group), but the mean duration of disease control was not reported. Our study, which includes more medically treated patients and patients with longer duration of disease, confirms those findings and further adds to the literature by reporting determinants of long-term QoL and longitudinal change in QoL. We previously showed in the MED cohort at baseline that QoL was no different in patients treated with somatostatin analog monotherapy compared to pegvisomant monotherapy, and we now show that this remains the case years later [19].

In contrast to some, but not all, prior studies of the effects of radiation therapy on QoL [9, 12–15], we did not find that radiation treatment negatively affected QoL in either group. GHD, on the other hand, did predict poorer long-term QoL, and this relationship was independent of radiation treatment. Advanced radiation therapy technologies such as stereotactic radiosurgery and proton beam therapy may be associated with a decreased risk of impaired cognition and seizures because of lower radiation exposure of the healthy brain compared with conventional radiotherapy, which could affect QoL. This may explain the association between radiation treatment and poorer QoL in older studies, although this has not been formally evaluated. We previously published data that patients with GHD after cure of acromegaly have worse QoL than those who are GH sufficient [15], and treatment with GH resulted in improvements in QoL by SF-36, QoL-AGHDA, and the Symptom Questionnaire [26]. The QoL differences could not be explained by radiation treatment or other hormone deficiencies, and the magnitude of impaired QoL was similar to that observed in studies comparing patients with GHD from other hypothalamic or pituitary lesions to healthy controls [15]. Another study found that QoL scores by AGHDA were poorer in females (but no different in males) with GHD following treatment for acromegaly or Cushing’s disease compared with GHD from other causes [27]. These data and the present study suggest that GHD can exert an independent detrimental effect on long-term QoL in both physical and psychological domains, although this phenotype may not be unique to acromegaly. Hypothyroidism was also associated with poorer QoL at reassessment despite all receiving thyroid hormone replacement, which is consistent with QoL studies in patients with primary hypothyroidism [28–30].

QoL improvement in acromegaly appears to be most pronounced in the first year of treatment, even in patients who have not achieved remission [31]. Two other studies that assessed whether QoL continues to change over time once patients have achieved biochemical control have shown inconsistent results; in neither of these studies was the effect of pharmacologic therapy for acromegaly specifically studied. In the four-year longitudinal study by Van der Klauuw et al. of patients who received multimodal therapy (surgery, radiation therapy, and/or somatostatin analogs) with a mean duration of disease control of 11.5 years, QoL declined on five QoL domains (physical functioning, social functioning, fatigue, psychological well-being, and personal relationships) [12]. In contrast, Kyriakakis et al. showed no change in QoL scores in a five-year prospective study of patients treated similarly (surgery, radiation, and/or somatostatin analogs or dopamine agonists) who had a mean duration of biochemical control of 7.8 years [1]. Potential explanations for differences in results include effects of treatment modality (subjects were analyzed together and not separated by treatment modality) or differences in duration of biochemical control between studies. We report an improvement in QoL in three of the four AcroQoL domains (Physical, Psychological, Appearance) and two GIQLI domains (Physical State, Emotions) in subjects relying on pharmacologic therapy for biochemical control. In subjects cured by surgery +/− radiation treatment, QoL worsened in two SF-36 domains (Pain, Physical Health Summary Score), two Symptom Questionnaire domains (Depression, Somatic), and the QoL-AGHDA in subjects with GHD.

A strength of this study was the inclusion of patients with decades of biochemical control; the mean duration of biochemical control was 15.0 years for MED and 20.4 years for NO-MED, which to our knowledge is the longest reported in the acromegaly QoL literature. This allowed us to investigate determinants of long-term quality of life, which is critical to patient care. As all patients in MED were on medication monotherapy, these data may not be generalizable to patients with more severe disease who require combination medical therapy following surgery ± radiation treatment. Additionally, these data may not apply to patients who have undergone multimodal therapy but not achieved biochemical control. Limitations of this study include that duration of follow-up for the longitudinal assessment was different for MED vs NO-MED and that only the SF-36 questionnaire was administered to both cohorts at both time points because we were constrained by previously collected QoL data. Longer-term, prospective studies with more frequent assessment timepoints are warranted to further characterize changes in physical and affective (including depressive) symptoms that affect QoL in patients treated for acromegaly.

In conclusion, QoL remained poor in patients with long-term (up to a mean of 15–20 years), sustained biochemical control of acromegaly. Patients requiring pharmacologic treatment did not experience poorer QoL than those cured by surgery +/− radiation; in fact, there was an improvement over time in many acromegaly-specific QoL domains in subjects treated pharmacologically, while QoL scores worsened on some physical and psychologic domains in the cohort cured by surgery +/− radiation. GHD, but not radiation treatment, predicted impaired QoL. Overall, our data suggest that a history of acromegaly and the subsequent development of GHD, but not pharmacologic or radiation treatment, are detrimental to QoL over the long-term. For patients with acromegaly who require additional treatment after surgery, long-term pharmacologic therapy is an excellent option. Because QoL on medication is robust over so many years, primary medical therapy (without surgery) may be an option that should be studied further.

Funding:

This work was conducted with support from The Endocrine Society Acromegaly Clinical Research Fellowship Award; NIH grants T32 DK007028, K24 HL092902, K23DK115903, and K23 DK113220; and the Harvard Catalyst/The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (Grants 1UL1TR001102, 8 UL1 TR000170 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, and 1 UL1 RR025758 from the National Center for Research Resources). Pfizer provided growth hormone for a randomized controlled trial from which baseline data for this study were obtained for a subset of subjects.

Conflicts of interest:

LED has received drug donation from Pfizer for an investigator-initiated study. WWW has participated as a clinical trial investigator for Chiasma. LBN has received grant support/investigator funding from Ipsen and Chiasma and serves as a consultant on an advisory board for Pfizer and Chiasma. BS has equity in Pfizer and Amgen. UBK served as a consultant on advisory boards for Novo Nordisk and Acerus. KKM has received grant support for investigator-initiated studies from Amgen and drug donation from Pfizer for an investigated-initiated study and has equity in GE, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Becton Dickinson, and Boston Scientific. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Ethics approval:

Approval was obtained from the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Board. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate:

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data availability:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Kyriakakis N, Lynch J, Gilbey SG, Webb SM, Murray RD (2017) Impaired quality of life in patients with treated acromegaly despite long-term biochemically stable disease: Results from a 5-years prospective study. Clinical endocrinology. 86(6):806–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pantanetti P, Sonino N, Arnaldi G, Boscaro M (2002) Self image and quality of life in acromegaly. Pituitary. 5(1):17–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trepp R, Everts R, Stettler C, Fischli S, Allemann S, Webb SM, et al. (2005) Assessment of quality of life in patients with uncontrolled vs. Controlled acromegaly using the acromegaly quality of life questionnaire (acroqol). Clinical endocrinology. 63(1):103–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paisley AN, Rowles SV, Roberts ME, Webb SM, Badia X, Prieto L, et al. (2007) Treatment of acromegaly improves quality of life, measured by acroqol. Clinical endocrinology. 67(3):358–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matta MP, Couture E, Cazals L, Vezzosi D, Bennet A, Caron P (2008) Impaired quality of life of patients with acromegaly: Control of gh/igf-i excess improves psychological subscale appearance. European journal of endocrinology. 158(3):305–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broersen LHA, Zamanipoor Najafabadi AH, Pereira AM, Dekkers OM, van Furth WR, Biermasz NR (2021) Improvement in symptoms and health-related quality of life in acromegaly patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 106(2):577–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biermasz NR, van Thiel SW, Pereira AM, Hoftijzer HC, van Hemert AM, Smit JW, et al. (2004) Decreased quality of life in patients with acromegaly despite long-term cure of growth hormone excess. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 89(11):5369–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biermasz NR, Pereira AM, Smit JW, Romijn JA, Roelfsema F (2005) Morbidity after long-term remission for acromegaly: Persisting joint-related complaints cause reduced quality of life. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 90(5):2731–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kauppinen-Makelin R, Sane T, Sintonen H, Markkanen H, Valimaki MJ, Loyttyniemi E, et al. (2006) Quality of life in treated patients with acromegaly. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 91(10):3891–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo X, Wang K, Yu S, Gao L, Wang Z, Zhu H, et al. (2021) Quality of life and its determinants in patients with treated acromegaly: A cross-sectional nationwide study in china. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 106(1):211–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelsma ICM, Biermasz NR, van Furth WR, Pereira AM, Kroon HM, Kloppenburg M, et al. (2021) Progression of acromegalic arthropathy in long-term controlled acromegaly patients: 9 years of longitudinal follow-up. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 106(1):188–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Klaauw AA, Biermasz NR, Hoftijzer HC, Pereira AM, Romijn JA (2008) Previous radiotherapy negatively influences quality of life during 4 years of follow-up in patients cured from acromegaly. Clinical endocrinology. 69(1):123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshida K, Fukuoka H, Matsumoto R, Bando H, Suda K, Nishizawa H, et al. (2015) The quality of life in acromegalic patients with biochemical remission by surgery alone is superior to that in those with pharmaceutical therapy without radiotherapy, using the newly developed japanese version of the acroqol. Pituitary. 18(6):876–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rowles SV, Prieto L, Badia X, Shalet SM, Webb SM, Trainer PJ (2005) Quality of life (qol) in patients with acromegaly is severely impaired: Use of a novel measure of qol: Acromegaly quality of life questionnaire. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 90(6):3337–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wexler T, Gunnell L, Omer Z, Kuhlthau K, Beauregard C, Graham G, et al. (2009) Growth hormone deficiency is associated with decreased quality of life in patients with prior acromegaly. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 94(7):2471–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Postma MR, Netea-Maier RT, van den Berg G, Homan J, Sluiter WJ, Wagenmakers MA, et al. (2012) Quality of life is impaired in association with the need for prolonged postoperative therapy by somatostatin analogs in patients with acromegaly. European journal of endocrinology. 166(4):585–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tseng FY, Chen ST, Chen JF, Huang TS, Lin JD, Wang PW, et al. (2019) Correlations of clinical parameters with quality of life in patients with acromegaly: Taiwan acromegaly registry. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association = Taiwan yi zhi. 118(11):1488–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghajar A, Jones PS, Guarda FJ, Faje A, Tritos NA, Miller KK, et al. (2020) Biochemical control in acromegaly with multimodality therapies: Outcomes from a pituitary center and changes over time. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 105(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dichtel LE, Kimball A, Yuen KCJ, Woodmansee W, Haines MS, Guan QX, et al. (2021) Effects of growth hormone receptor antagonism and somatostatin analog administration on quality of life in acromegaly. Clinical endocrinology. 94(1):58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr., Raczek AE (1993) The mos 36-item short-form health survey (sf-36): Ii. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Medical care. 31(3):247–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webb SM, Badia X, Surinach NL (2006) Validity and clinical applicability of the acromegaly quality of life questionnaire, acroqol: A 6-month prospective study. European journal of endocrinology. 155(2):269–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ure BM, Schmulling C, Neugebauer E, et al. (1995) Gastrointestinal quality of life index: Development, validation and application of a new instrument. The British journal of surgery. 82(2):216–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellner R (1987) A symptom questionnaire. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 48(7):268–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKenna SP, Doward LC, Alonso J, Kohlmann T, Niero M, Prieto L, et al. (1999) The qol-aghda: An instrument for the assessment of quality of life in adults with growth hormone deficiency. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 8(4):373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arshad MF, Ogunleye O, Ross R, Debono M (2021) Surgically treated acromegaly patients have a similar quality of life whether controlled by surgery or requiring additional medical therapy (qualat study). Pituitary. 24(5):768–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller KK, Wexler T, Fazeli P, Gunnell L, Graham GJ, Beauregard C, et al. (2010) Growth hormone deficiency after treatment of acromegaly: A randomized, placebo-controlled study of growth hormone replacement. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 95(2):567–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldt-Rasmussen U, Abs R, Bengtsson BA, Bennmarker H, Bramnert M, Hernberg-Ståhl E, et al. (2002) Growth hormone deficiency and replacement in hypopituitary patients previously treated for acromegaly or cushing’s disease. European journal of endocrinology. 146(1):67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winther KH, Cramon P, Watt T, Bjorner JB, Ekholm O, Feldt-Rasmussen U, et al. (2016) Disease-specific as well as generic quality of life is widely impacted in autoimmune hypothyroidism and improves during the first six months of levothyroxine therapy. PloS one. 11(6):e0156925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan NC, Chew RQ, Subramanian RC, Sankari U, Koh YLE, Cho LW (2019) Patients on levothyroxine replacement in the community: Association between hypothyroidism symptoms, co-morbidities and their quality of life. Family practice. 36(3):269–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samuels MH, Kolobova I, Niederhausen M, Janowsky JS, Schuff KG (2018) Effects of altering levothyroxine (l-t4) doses on quality of life, mood, and cognition in l-t4 treated subjects. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 103(5):1997–2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolters TLC, Roerink S, Sterenborg R, Wagenmakers M, Husson O, Smit JWA, et al. (2020) The effect of treatment on quality of life in patients with acromegaly: A prospective study. European journal of endocrinology. 182(3):319–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.