Abstract

Trans women are disproportionately incarcerated in the United States and Australia relative to the general population. Stark racial and ethnic disparities in incarceration rates mean that Black American and First Nations Australian trans women are overrepresented in incarceration relative to White and non-Indigenous cisgender and trans people. Informed by the Intersectionality Research for Transgender Health Justice (IRTHJ) framework, the current study drew upon lived experiences of Black American and First Nations Australian trans women to develop a conceptual model demonstrating how interlocking forces of oppression inform, maintain, and exacerbate pathways to incarceration and postrelease experiences. Using a flexible, iterative, and reflexive thematic analytic approach, we analyzed qualitative data from 12 semistructured interviews with formerly incarcerated trans women who had been incarcerated in sex-segregated male facilities. Three primary domains—pathways to incarceration, experiences during incarceration, and postrelease experiences—were used to develop the “oppression-to-incarceration cycle.” This study represents a novel application of the IRTHJ framework that seeks to name intersecting power relations, disrupt the status quo, and center embodied knowledge in the lived realities of formerly incarcerated Black American and First Nations Australian trans women.

Keywords: intersectionality, oppression, heteropatriarchy, systemic racism, health inequities

Introduction

Trans women1 are disproportionately incarcerated in the United States and Australia relative to the general population (Brömdal et al., 2019a; Brömdal et al., 2019b; Glaze & Kaeble, 2014; Glezer et al., 2013; Grant et al., 2011; Lynch & Bartels, 2017; Van Hout et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2017), with estimates suggesting that 19% to 65% of trans women have been incarcerated at least once in their lifetime (Clements et al., 1999; Garofalo et al., 2006; Grant et al., 2011; Reisner et al., 2014) compared to approximately 2.5% of the general population (Maruschak & Minton, 2020).

This high burden of incarceration among trans women is produced in part by the disproportionate experiences of discrimination, violence, and victimization trans women face across their lifespan due to having a gender identity and/or expression that does not align with socially constructed norms, rooted in cisgenderism2 and heteropatriarchy3 (Clark et al., 2017; Musto, 2019; Stanley & Smith, 2015; Wesp et al., 2019; White Hughto et al., 2015, 2018).

These victimizations in turn restrict access to material and financial resources, including employment and housing, leading some trans women to turn to street economies, such as sex work, for financial survival (Brömdal et al., 2019b; Garofalo et al., 2006; Grant et al., 2011; Lynch & Bartels, 2017; Mizock & Mueser, 2014; Nemoto et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2017) and using substances to cope with mistreatment and psychological implications of victimization (Garofalo et al., 2006; Grant et al., 2011; Mizock & Mueser, 2014; Nemoto et al., 2011; Reisner et al., 2015).

Intersecting with these aforementioned experiences, which place trans women at higher risk of arrest and incarceration, are stark racial disparities in incarceration rates entrenched globally in White supremacy, histories of settler colonialism, and systemic racism. Black Americans4 are incarcerated in U.S. state prisons at a rate 5 times that of White Americans, and in 12 states over half the prison population is Black (Walker et al., 2016). Moreover, Black American trans women have a threefold risk of incarceration history compared to White American trans women (Reisner et al., 2014).

Paralleling the U.S. context, First Nations Australians are disproportionately incarcerated.5 In 2020, First Nations Australians were incarcerated in state prisons at a rate 11 times that of the non-Indigenous population, with 79% also having experienced prior incarceration (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020). Due in part to lack of transparent and publicly available data in concert with the fact that no large-scale Australian survey exists comparable to the U.S. Transgender Survey, it is difficult to ascertain the rate of incarceration among trans women in Australia, including First Nations trans women6 (James et al., 2016).

Although it is estimated that <1% of the Australian prison population identify as trans, this is probably underestimated (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2015; Bali, 2020; Lynch & Bartels, 2017; Wilson et al., 2017). Indeed, due to the cyclical nature of incarceration and release, quantifying the proportion of incarcerated trans people in both the United States and Australia at any given timepoint is challenging. This may result in an underestimate of the burden of incarceration for this population.

Due to the elevated risk and vulnerability of trans women in male prisons, some trans women—especially those holding multiple minoritized identities—may elect to not disclose their trans history in order to avoid mistreatment, leading to underreporting/counting of incarcerated trans people in both the United States and Australia (Brömdal et al., 2019a; White Hughto et al., 2018).

Recognizing these multiple and intersectional layers of discrimination, mistreatment, violence, and victimization, and acknowledging the scholarship of Black and other racial and ethnic minority and Indigenous trans scholars, activists/advocates, and prison abolitionists (Lydon et al., 2015; Stanley & Smith, 2015; Wesp et al., 2019), trans carceral health research requires the development of a conceptual model that depicts and names the interlocking forces of oppression that trans women of color experience across their lifespan within and outside of prison walls.

The goal of the current study was to develop a conceptual framework to demonstrate how interlocking forces of oppression (e.g., cisgenderism, heteropatriarchy, White supremacy, settler colonialism, systemic racism) collectively inform, maintain, and exacerbate pipelines/pathways to incarceration among Black American and First Nations Australian trans women, including their incarceration and postrelease experiences.

Method

Guiding Theoretical Framework: Intersectionality Research for Transgender Health Justice

Informed by the lived experiences of Black American and First Nations Australian trans women with incarceration histories, this article conceptualizes the incarceration experiences of Black American and First Nations Australian trans women by grounding discourse and analyses within a novel theory-driven conceptual framework: the Intersectionality Research for Transgender Health Justice (IRTHJ) framework (Wesp et al., 2019). IRTHJ, developed in 2019 by a multidisciplinary group of health scholars of trans and cisgender experience, draws upon theories of intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1990; Mays & Ghavami, 2018) and structural injustice (Young, 2010) to advance trans health inequities research.

Intersectionality theory, rooted in Black lesbian feminist resistance movements of the late 20th century (Combahee River Collective, 1995) and formally introduced into legal scholarship by Crenshaw (1990), posits that, “multiple social categories (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, ability) intersect at the micro level of individual experience to reflect multiple interlocking systems of privilege and oppression at the macro, social-structural level (e.g., racism, sexism, heterosexism, ableism)” (Bowleg, 2012, p. 1267).

The theory of structural injustice posits that unjust systems of privilege and oppression have become the status quo, and the normalization of these ingrained systems benefits and privileges some members of society while harming and marginalizing others (Young, 2010). Structural injustice theory further suggests that it is the collective responsibility of all members of society to actively resist against such sociostructural systems of oppression in an effort to achieve health equity (Wesp et al., 2019; Young, 2010).

Uniting intersectionality theory and structural injustice theory, IRTHJ posits that interlocking forces of power including structures of domination (e.g., cisgenderism, White supremacy), institutional systems (e.g., criminal–legal, health care), and sociostructural processes (e.g., colonizing, criminalizing) produce health inequities owing to trans people's “structurally produced marginalized social positions at the intersections of race, ethnicity, citizenship, gender, sexuality, age, disability, and class” (Wesp et al., 2019, p. 290). IRTHJ calls upon researchers to engage in the following three actions to actively resist these structures, systems, and processes and to advance trans health justice and associated research: naming intersecting power relations, disrupting the status quo, and centering embodied knowledge.

Below we describe how our authorship team of cross-continental, interdisciplinary scholars engages in each of these three actions to document incarceration experiences of Black American and First Nations Australian trans women and disrupt the systems of power that work to oppress and criminalize these populations.

Naming Intersecting Power Relations

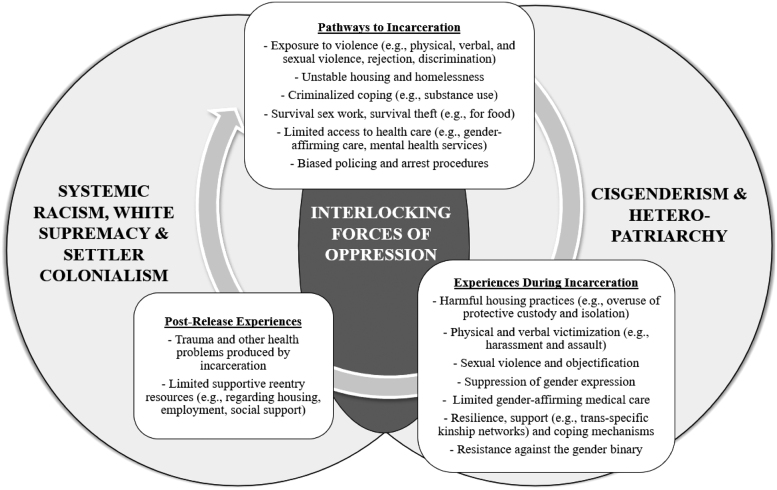

IRTHJ encourages researchers to consider and name interlocking forces of power that produce trans health inequities (Wesp et al., 2019). Figure 1 depicts our conceptual model documenting the oppression-to-incarceration cycle of Black American and First Nations Australian trans women that was developed through interviews we conducted with formerly incarcerated Black American and First Nations Australian trans women (see Results and Discussion section for details).

Fig. 1.

Oppression-to-incarceration cycle of Black American and First Nations Australian trans women developed through interviews with formerly incarcerated trans women in the United States and Australia.

In this model, we depict and name the primary interlocking forces of oppression that imbue the pathways to incarceration, incarceration experiences, and postrelease experiences in both countries. Systemic racism, White supremacy, settler colonialism, cisgenderism, and heteropatriarchy permeate the day-to-day existence of Black American and First Nations Australian trans women within and beyond the prison walls (Biello & Hughto, 2021; Stanley & Smith, 2015). By centering these interlocking forces of oppression immediately behind the foregrounded cycle, we aim to demonstrate that these systems of domination produce, maintain, and exacerbate the oppression-to-incarceration cycle and associated health inequities.

Disrupting the Status Quo

IRTHJ challenges trans health equity scholars to critically engage in self-reflexivity to disrupt the status quo by inspecting our positionalities and worldviews and examining how we may directly or indirectly maintain the structural production of health inequities (Wesp et al., 2019). Our research team is a cross-continental group of scholars based in the northeastern and southeastern United States and in Queensland and New South Wales, Australia. Our scholarship spans disciplines of gender studies, sociology, education, clinical and health psychology, epidemiology, behavioral sciences, health policy, public health, criminology, and medical anthropology.

The authors have been engaged in trans health equity research situated in the context of incarceration settings for 4 to 20 years; collectively, our authorship team has nearly 50 years of trans health justice and equity research and advocacy experience. We include scholars of trans and cisgender (cis) experience spanning sexual orientations (e.g., bisexual, pansexual, genderqueer, heterosexual), class backgrounds (e.g., working class, upper-middle class), immigration statuses (i.e., immigrant, first generation, native-born), and language statuses (i.e., English as an additional language; English as a first language).

Racial and ethnic identities of our team include North African, White European descent, and White Australian. Importantly, our authorship team also includes both trans and cis people with incarceration experiences. We acknowledge that our positionalities as a group of scholars who are predominately White or of Eurocentric ethnicity and working within systems of higher education mean that we have benefited from institutions that have historically excluded scholars of color including Black and Indigenous scholars.

We further acknowledge that we do not hold the culturally specific knowledges and perspectives of Black and First Nations peoples. Professionally and personally, we endeavor to dismantle the systems of oppression that maintain the structural production of health inequities including from within our institutions of higher education in the United States and Australia.

Centering Embodied Knowledge

IRTHJ calls upon researchers to center embodied knowledge by “valu[ing] and be[ing] accountable to…the voices, situated knowledge, and perspectives of trans populations, especially those who experience and resist multiple intersecting oppressions” (Wesp et al., 2019, p. 292).

Collectively, we strive to center the lived experiences of trans individuals with incarceration histories in four concrete ways: (a) elevating the voices of incarcerated trans people through their own words drawn from interviews and letters (du Plessis et al., 2022; Haire et al., 2021; Halliwell et al., 2022; Phillips et al., 2020; Sanders et al., 2022; White Hughto et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2017); (b) engaging with community-based organizations serving and advocating for trans people involved with the criminal–legal system in the United States and Australia; (c) involving trans people with incarceration experience in our research including in study design, development, delivery, and dissemination; and (d) leveraging our positions of relative privilege to advocate for trans health equity within and beyond incarceration settings.

The present article centers embodied knowledge by drawing upon semistructured interviews with formerly incarcerated Black American and First Nations Australian trans women. As researchers, we acknowledge the historically unjust power differentials between researchers and minoritized research participants including racial and ethnic minority trans populations (Rogers & Lange, 2013; Vincent, 2018; Wesp et al., 2019). We, therefore, have worked for several years in Australia and the United States to build trust with local communities of trans women with incarceration histories including Black Americans and First Nations Australians. To do so, we developed our research projects, research questions, and interview questions in consultation with trans community members and trans support organizations.

Trans community members in both nations endorsed our research and helped facilitate the recruitment process and encouraged formerly incarcerated trans community members to share their lived experiences with our research team. We situate the personal lived experiences of Black American and First Nations Australian trans women within the context of the permeating and ingrained forces of oppression (see Fig. 1) with the ultimate collective goal of naming, resisting, and dismantling these structures.

Sample

The present investigation included 12 interviews with formerly incarcerated Black American (9 interviews) and First Nations Australian (3 interviews) trans women. Participants were eligible to participate if they were 18 years or older; assigned male sex at birth; identified as a woman, trans woman, or on the trans-feminine or male-to-female spectrum; and had been incarcerated in a prison or jail within the past 5 years. All participants had been incarcerated in sex-segregated male facilities.

The U.S. sample was drawn from interviews collected in 2015 as part of a larger investigation (Hughto et al., 2018) into the health care experiences of incarcerated trans women, including questions regarding health care needs during incarceration, access to gender-affirming medical care (e.g., hormones, surgery), factors influencing health while incarcerated, and more general questions regarding the lived experiences of incarcerated trans women. Of the nine trans women interviewed, seven identified as Black American and two identified as Black American and mixed race (e.g., Afro-Latina). Participants ranged in age from 28 to 49 years old (average 38 years) and had been incarcerated for, on average, 5 years. Participants were compensated with a $50 gift card.

The Australian sample was drawn from interviews collected in 2018 and 2019 as part of larger study (Brömdal et al., 2022) exploring the lived experiences of trans persons in Queensland, including housing, health care experiences, and barriers and supports to well-being while incarcerated. The three interviews included in this study were with First Nations trans women. Participants ranged in age from 20 to 52 years old (average 36 years) and had been incarcerated for, on average, 4 months. Participants received a gift card of a similar amount as compensation for their time.

We acknowledge that having fewer Australian than U.S. interviews may have inadvertently elevated U.S.-centric perspectives in our findings; however, we intentionally involved U.S. and Australian researchers in each analytic step in effort to ensure that analyses prioritized the voices and views of participants in both nations.

Procedure

The goal of this investigation was to critically examine the incarceration experiences (encompassing pre- and postrelease experiences) of Black American and First Nations Australian trans women through semistructured, qualitative interviews. This analysis was catalyzed by formal and informal cross-continental research team discussions regarding the structures of oppression that seemed to operate similarly in the United States and Australia to uniquely harm the Black American and First Nations Australian trans women recruited in our larger investigations.

In both nations, interviews (ranging from 45 to 120 minutes) were conducted in person at a place of the participant's choice (e.g., local community-based organization, coffee shop). Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim; to protect anonymity, participant names were anonymized with pseudonyms. Both research projects were approved by their university's respective ethics board.

The IRTHJ framework guided our analytic approach such that participants' lived experiences were situated within existing, ingrained structures of power and domination. Analyses followed a flexible thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, 2019). Interviews were conducted by J.M.W.H. in the United States and by A.B. in Australia, and coded by K.A.C. in the United States and by T.P. in Australia—all of whom have extensive training in qualitative research methods focused on trans populations with incarceration experience.

Although the 12 interviews had been used in previous larger investigations, we considered the interviews with Black American and First Nations Australian trans women as a unique set of interviews; thus, we conducted a completely new and independent analysis (with codebook and resultant themes) led by two different coders than led the larger investigations. Aligned with thematic analysis, coders followed a six-step process including reading and rereading all interviews, open coding, refining and collapsing codes, defining themes, and developing the conceptual model integrating results.

The analytic process was flexible, iterative, and reflexive (Braun & Clarke, 2019). Coders had regular one-on-one meetings over a period of several months to discuss and refine codes and develop themes. Throughout the analytic process, coders consistently reflected on how the developing themes were situated within larger structures of power and domination aligned with an IRTHJ framework and how their personal and professional positionalities informed analysis and conceptual model development. In the final steps of analyses, coders discussed and refined identified themes and the associated conceptual model across several meetings with the entire authorship team.

Results and Discussion

Overview: Oppression-to-Incarceration Cycle

Three primary domains were identified from this analysis: (a) pathways to incarceration, (b) experiences during incarceration, and (c) postrelease experiences. Within each domain, there were several themes. The oppression-to-incarceration cycle delineated in Figure 1 integrates each domain and theme and documents the cyclical nature of the findings such that one set of experiences produced the next and so on.

The cycle itself is situated within the context of interlocking systems of domination related to race and ethnicity (i.e., structural racism, White supremacy, settler colonialism) and gender identity (i.e., cisgenderism, heteropatriarchy). These forces of oppression operate in tandem before, during, and after incarceration to exclude, oppress, marginalize, and criminalize Black American and First Nations Australian trans women and drive health inequities.

Because the overarching goal of the study was to apply the IRTHJ framework to develop a conceptual model delineating the incarceration experiences of racial and ethnic minority trans women across two nations, here we briefly summarize each theme and offer salient qualitative examples in Table 1.

Table 1.

Salient Quotes Characterizing the Oppression-to-Incarceration Cycle Developed Through Interviews With Black American and First Nations Australian Trans Women

| Theme | Subtheme | Qualitative example | Participant's nation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathways to incarceration | Exposure to violence (e.g., physical, verbal, and sexual violence, rejection, discrimination) | “Well, I was born in [year], and that was during the time for a lotta Black people, um, a time of civil unrest, a time when we were considered second-rate and second-class citizens, and still are to this day, with some people. And, um, I really felt that growin’ up as a little boy, I'm gonna say for now that's—this part of the interview—because I didn't understand it [my gender identity]…I didn't have a definition for being transgendered at that time… when I was 12.” | United States |

| “I got mucked around with [molested] since I was 5 years old until I was 11 years old by him [my uncle].” | Australia | ||

| “I went in my mother's closet, and got all dolled up and dressed up, and she came home early, of course, and caught me, and was upset, and [said], ‘you take them clothes off, you're never gonna be a woman so stop acting like one.’…I couldn't be open in my home ‘cause it clearly wasn't accepted.” | United States | ||

| “I got flogged [by my father], you know?” | Australia | ||

| Unstable housing and homelessness | “…my first experience with the law was when I was 18. Um, I was working [in retail]. And, uh, I was actually homeless. And started to try to have to find food. And didn't have anywhere to live. But I worked [at a clothing retailer]. So, I ended up kinda start stealing and ended up, uh, getting a felony case right out of high school. And, uh, kinda really changed my whole life, you know. And, uh, it's kinda like it's been haunting me forever and ever.” | United States | |

| “I didn't go and steal someone's car just for the fun of it. I had to get places, I had to do things and I had to have somewhere to sleep … And that was better than the streets.” | Australia | ||

| Criminalized coping (e.g., substance use) | “…of course, because of my emotional state, um, and having this ugly relationship with my parents, I turned to drugs and alcohol to cope.” | United States | |

| “I've been [incarcerated] a lot, I've been in [name] Juvenile Detention Centre … when I was 14 and I was doing drugs all the time when I was 14.” | Australia | ||

| “I said I started drinkin’ and druggin’ at 12. You know weed and beer and stuff like that, because it was doin’ more for me than just givin’ me a buzz, it was really numbing me, it was really, um, just took the pain away.” | United States | ||

| Survival sex work, survival theft (e.g., for food) | “I'm a recovering addict, I'm a trans woman, and um, for many years I've sex worked and lived beneath the law.” | United States | |

| “So, a lot of my crime was petty, and a lot of my incarceration was for unpaid fines. And it all surrounded my drug use; I was heroin dependent from a very young age. And so, all my offending was … for prostitution and unpaid fines and just petty crime associated with part of using drugs.” | Australia | ||

| Limited access to health care (e.g., gender-affirming care, mental health services) | “I survived the suicide attempt when I was 12, physically, but emotionally, spiritually, and mentally, I really did kill myself, because I was just in so much pain and—and loss, and the fact that I wanted to die, so I just walked around dead.” | United States | |

| “I'm a trans women and I became HIV positive, you know, in the sex industry. Um, and the end result is, like, there's no 401k plan…you're gonna be beaten, you may get killed, you're gonna infect, and you're going to end up with a compromised immune system. They don't tell them [young trans women] that. You're gonna end up… getting silly putty pumped into you. You're gonna have to go get lanced open because you wanted a quick fix, and, like, girls are dying from illegal silicone.” | United States | ||

| Biased policing and arrest procedures | “Eight months ago, I was arrested in [U.S. state], and the cop, he was like, ‘What is your name?’ and I said my name is [Nadia], and I gave him my debit card… he said, ‘No your name.’ I said, ‘It is my government name,’ and it was.” | United States | |

| “[My trans woman friend], uh, had a [sex industry] client who ended up hitting her, like was attacking her. And, uh, he called the cops. And they totally did not want to hear it. And he was like 6′4″ and he came with like nine police officers. And we sat there and waited for them because we were attacked. He was like beating her up. And I didn't even, I never even hit him… And, uh, they came and they arrested us… I sat in [U.S. state] in jail for 4 months.” | United States | ||

| Experiences during incarceration | Harmful housing practices (i.e., overuse of “protective custody” and isolation) | “When I first got there… they kept treating me like the monkey in the window. They had me in the infirmary in this big, huge glass, and I woke up and I was like, why am I here?” | United States |

| “I think part of the reason why [rape by a correctional officer] happened because I was, they put me in isolation where I was in a, in a room by myself… Just for my safety, they hadn't dealt with trans prisoners in there before. So, they pretty much put me in there for my safety away from the mainstream prison system. It was part of their hospital prison in [Australian state]. And, and then, so- protecting me, but it actually put me in danger with the prison. Well, the prison officer come into my cell at night…” | Australia | ||

| Physical and verbal victimization (e.g., harassment and assault) | “The nurse, she makes it a point to like defeminize you. … ‘you're not a girl’, they say things like ‘you're not a girl, you're a he’, you know what I mean? Like they would say very derogatory things just to break your spirit.” | United States | |

| “I was constantly on guard… But I only had one actually altercation. Because … they're very racist up there [in US state]. And so, it was not even so much my altercation wasn't even so much the fact that the fact that I was [trans], it was more so because I was African American.” | United States | ||

| “I think [Australian state prison] and other prisons hadn't had a lot of transsexuals in them, where the officers haven't had any experience, they just—, they can be—, they can be misgendering you, they can be. I had, I remember when I was in [name] jail the, I think she was the deputy superintendent, called me a ‘thing’.” | Australia | ||

| “There was this Kiwi [New Zealander] officer that always called me a tranny or a transvestite. And I said, “I'm trans, there's a difference…. It's not my fault, stop calling me names.” | Australia | ||

| Sexual violence and objectification | “I know the degradation, the humiliation around being incarcerated and ostracized, and marginalized, and sexualized, and all that comes along when you put a bunch of men, quote, unquote, “heterosexual men” in a room with something different… That prison changed my whole perspective. I was like, I'm out of my element, I can't do this. I literally had a convict walk up on me and say—‘cause it was really hot and I didn't have any money yet and I didn't have a bra, so I guess you could see my breasts and he said, ‘if you get raped it's your fault.’” | United States | |

| “I self-harmed in jail. I just wanted, I partially just wanted to get out of—… one time I was in [Australian prison] and I was in the section that was just, there'd been some guys that tried to rape me, it was just horrendous. I just wanted to get out of there, and I wanted to go to another section of the prison.” | Australia | ||

| Suppression of gender expression | “…it was horrible, I mean, if they cut your extensions out, if you have like extensions in your hair, … they like literally—and they don't, like, let you take it out yourself. They cut it out and those officers are, like, they make a point to try to, like, um, defeminize you completely. So, like, they would like cut patches in your head, you know what I mean? Purposely, so you had to buzz your hair after that … if you have weave sewn in, they would cut the braids. So, your hair would look ridiculous.” | United States | |

| “…even though you were classed as male, you're a different kind of male …we were told that we'd have to wear a shirt all the time. Men would be able to walk around with shirts off, and we were classed as men, [but] we'd have to keep our breasts covered at all times.” | Australia | ||

| “…they told me I had to take everything off, like my hair, my nails, my jewelry, everything.” | United States | ||

| Limited gender-affirming medical care | “…because I never – I don't have a prescription, uh, for hormones, they wouldn't give me any.” | United States | |

| Interviewer: “What training do you think the nurses had around trans [health care]?” Interviewee: “None. At all. Nothing at all. Just what they heard from [trans] girls going into a jail.” |

Australia | ||

| Resilience, support (e.g., informal kinship networks) and coping mechanisms | “There were other trans women I was incarcerated with that I knew from the street … we would try to, like, cheer each other up … we just did little things just to you know, that we were accustomed to doing. Like, dancing and stuff.” | United States | |

| “And I said to [another trans woman], ‘here, we've got our own cells, I can come to yours and you can come to mine,’ and she goes, ‘you won't put up with me darling.’ And I said, ‘oh please’…That's the way that we mucked around and joked.” | Australia | ||

| Resistance against the gender binary | Interviewee: “When I was in jail, you know, I presented the way that I feel that I should be, you know. I always kept my face clean shaved and at times, my [trans] friends and I would have a little bit of makeup on…” Interviewer: “So where did you get the makeup from?” Interviewee: “Believe it or not, oh, god. It was kind of risky. But we, um, I used to get like black tar that goes into windows. And we used Vaseline. And if you let it sit on it long enough, it almost like melts a little bit…so we used to use that.” |

United States | |

| “I felt that I had to force it [file complaint against the prison system] because I think they would have been quite happy to sweep it under the carpet or try and ignore it but because I had an extensive knowledge of the system because I'd been in it for so long and knew that once I asked for the official forms and copies of my complaint as well. That it almost forced them to act on it, but I don't think they would have acted on it otherwise.” | Australia | ||

| Postrelease experiences | Trauma and other health problems produced by incarceration | “I thought a friend was a friend and then he actually raped me … I feel dirty inside, I feel like a slut. But like my mum said it's not my fault … and if I tell [who raped me], I will get my head smashed in, stood over.” | Australia |

| “There'd been some guys that tried to rape me, it was just horrendous I just wanted to get out of there, and I wanted to go to another section of the prison. So—, I swallowed, I cut my wrists and I swallowed razor blades … They couldn't get them out endoscopically so they had to get them out, they had to operate, cut me open. So, I wasn't really suicidal I was desperate.” | Australia | ||

| “I guess I'm very comfortable with my transition, even though I'm not as far as I would like to be in my transition. But I'm very comfortable. I walk the streets. I've had jobs. I shop. I'm out all the time. And I don't really get harassed or anything like that. So to get to a jail and it's, like, okay, well, you guys should at least try to keep me safe. I mean, who knows if I'm going to go into this thing and these guys are so homophobic that they attack or something. You never know. And that was like my biggest fear.” | United States | ||

| Limited supportive reentry resources (e.g., regarding housing, employment, and social support) | Participant recounting their interaction at homeless shelter immediately following release from incarceration: “I said ‘I need a bed,’ he said ‘You can't stay here miss.’ I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘This is a men's shelter.’ I said, ‘Well thank you,’ I said, ‘Nice compliment.’ I look like Whoopie Goldberg right now and I feel like shit, look like shit, and it's cold outside, but then I said, ‘But I am a man.’ ‘Cause I didn't know any other address or I didn't know where you were supposed to go… and he was like, ‘No you're not and you're not staying here.’ |

United States | |

| Participant recalls the positive influence of supportive reentry resources: “One of the positive experiences was when I was let out of prison once, and the Gender Centre in [Australian city] had come in and seen if I needed any help with housing when I left there. So, when I left the prison I went straight into Gender Centre housing, which is a supportive environment. So it was a really positive thing for me and helped me because I wasn't straight back out sex working and putting myself in danger and reoffending …like I was supported.” |

Australia | ||

| “Because of my drug use and being trans, I was estranged from my family. I didn't have my family support.” | United States |

Pathways to Incarceration

Participants situated their early life experiences within existing structures of power and domination (see Table 1 for exemplary quotes). In both nations, participants characterized their upbringings as being fraught with experiences of racism, socioeconomic marginalization, and parental mental health problems and substance use. Participants described early life experiences of violence and rejection steeped in expectations of cisgenderism and heteronormativity. From a young age, participants felt “different” and were frequently treated differently from their siblings, peers, and classmates due to their feminine gender expressions. Often, participants faced severe familial rejection whereby they were explicitly forbidden from expressing their femininity in the house or face being “kicked out.”

With little support from family, unstable access to housing, and few employment opportunities (often due to antitrans discrimination), participants frequently engaged in underground economies to survive (e.g., sex work, selling drugs, petty theft). Faced with the compounding forces of racism and cisgenderism that left many participants navigating poverty and homelessness, in conjunction with the mental health sequelae of early life traumas and rejection, many participants used drugs or alcohol to cope. Participants described limited or no access to mental health care services and often obtained gender-affirming medical procedures (e.g., hormones, silicone injections) from unsupervised street vendors due to lack of access to health care or, in the United States, lack of health insurance.

Furthermore, participants were unduly surveilled, targeted, and harassed by law enforcement due to their intersecting trans and racial and/or ethnic minority identities. The coalescence of these experiences frequently resulted in the incarceration of Black American and First Nations Australian trans women in the United States and Australia.

Incarceration Experiences

While incarcerated in sex-segregated male facilities, Black American and First Nations Australian trans women faced rampant violations of their health and human rights driven by paramilitaristic prison environments that promote and value hypermasculinity and heteronormativity (see Table 1 for qualitative examples). Upon incarceration, many participants were sequestered into single cells in “protective custody” units or in the medical infirmary where they were isolated in captivity for most of the day.

Although correctional administrators justified the forced isolation as a means to protect trans women from the general male population, “protective custody” often fostered more harm including the mental health toll of isolation as well as sexual assault and rape at the hands of prison staff. Physical and verbal victimization and harassment by other incarcerated people and prison staff were common, and participants described being frequent targets of transphobic and racist attacks.

Sexual violence and objectification of trans women were normalized, and prison staff and other incarcerated people reiterated to trans women the notion that rape was inevitable. Many participants were sexually harassed, assaulted, and raped by other incarcerated people as well as prison staff, which resulted in their hypervigilance, distress and trauma, and self-harm.

Furthermore, adhering to strict masculinity norms, the prison attempted to squash any expression of trans women's femininity. Participants described that their hair was forcibly cut, they were policed and punished for “acting feminine,” and they were denied female commissary items such as brassieres.

In addition, participants had little to no access to gender-affirming medical care while incarcerated. Without prescription documentation of hormone therapy prior to incarceration, many participants' access to hormones was ceased during incarceration, leading to severe mood swings, depression, and gender dysphoria. Moreover, most participants explained that prison health care staff had limited (or no) training related to trans people's health care needs and were frequently openly transphobic (e.g., purposefully misgendering trans patients).

Despite facing subjugation, victimization, and violence during incarceration, Black American and First Nations Australian trans women demonstrated incredible resilience in part due to the support of other incarcerated trans women. Indeed, participants formed trans-specific kinship networks inside the prison walls to share advice and companionship. The trans women often worked together to resist the prison's strict gender binary, whereby they shared knowledge on how to create rudimentary makeup and feminine clothing. The trans women then took steps to resist the gender binary by creatively expressing their womanhood in male facilities through makeup, clothes, and feminine mannerisms, and by advocating for themselves through lodging complaints against the prison system for violating their human and civil rights.

Postrelease Experiences

The severe sexual and physical violence that trans women experienced while incarcerated produced trauma that affected participants long after they were released (see Table 1 for salient quotes). Participants in both nations described feelings of worry, distress, and low self-worth and experiences of nightmares due especially to sexual victimization and rape that they experienced while incarcerated.

Furthermore, most participants said that after release from incarceration, there was limited (or no) reentry resources or access to family support to help them reintegrate into society. Many were dropped off at homeless shelters immediately upon discharge and realized only upon arrival that the shelter did not allow trans women to stay. Participants who were able to access supportive reentry resources (e.g., housing) explained how instrumental the resources were in stabilizing their lives. However, few participants had access to any supportive reentry resources, and most described that without access to supportive housing, employment, or social support, they were regularly forced back into pathways to incarceration and the oppression-to-incarceration cycle begins anew.

Conclusion

We are careful to note that not all forces of oppression that subjugate Black American and First Nations Australian trans women in the United States and Australia nor all pathways to incarceration, incarceration experiences, and postrelease experiences are captured by the oppression-to-incarceration cycle developed here.

For an ongoing understanding of the harmful toll of forced captivity on trans people across the globe, we encourage readers—especially White and cisgender members of the academe—to engage with the wealth of essays from formerly and currently incarcerated people in Captive Genders: Trans Embodiment and the Prison Industrial Complex (Stanley & Smith, 2015) as well as with reports and resources generously produced by trans, Indigenous, and people of color-led activist and resistance organizations in the United States (e.g., Black and Pink, Gender Justice LA, National Center for Transgender Equality) and in Australia (e.g., NSW Trans and Gender Diverse Criminal Justice System Advisory Council, Sisters Inside, Inc.).

The oppression-to-incarceration cycle developed here through interviews with Black American and First Nations Australian trans women documents how trans health inequities are produced, maintained, and exacerbated by the carceral system and presents an application of the IRTHJ framework. This conceptual model seeks to name intersecting power relations, disrupt the status quo, and center embodied knowledge in the lived realities of formerly incarcerated Black American and First Nations Australian trans women.

Authors' Contributions

K.A.C. conceptualized the study, conducted analyses, and wrote the initial draft. A.B. collected data, reviewed and revised drafts, and provided supervision. T.P. conducted analyses and reviewed and revised drafts. T.S. reviewed and revised drafts. A.B.M. reviewed and revised drafts. J.M.W.H. collected data, conducted analyses, reviewed and revised drafts, and provided supervision.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the HIV Foundation Queensland with the second author as the lead investigator [Project ID 2017-20, 2017] and the Yale Fund for Gay and Lesbian Studies with the last author as the lead investigator [2015]. This work was also supported by the University of Southern Queensland through an Internal Research Capacity Grant with the second author as the lead investigator [Project ID 1007573, 2020].

“Trans women” is an umbrella term that refers to the diversity of individuals assigned male sex/gender at birth who are women. We purposefully and intentionally use the term “trans women” as it is generally the preferred term of our community partners and our research team members who identify with this umbrella term.

Cisgenderism pathologizes/rejects a person's gender when that gender identity does not align with the gender they were assumed at birth (Worthen, 2016).

Heteropatriarchy is a sociopolitical system where (primarily) cisgender males and heterosexuals have authority over cisgender women and people of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities (Valdes, 1996).

“Black American” is an umbrella term used in the United States to describe people who are descendants of enslaved people from the African continent as well as immigrants and descendants of immigrants from African nations and the Caribbean. (Berlin, 2010).

“First Nations Australians” refers to Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia and encompasses the diversity of Australia's First Peoples, cultures, languages, beliefs, and practices (Australian Institute of First Nations and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 2021).

The term “First Nations Australian trans women” is used in this article to represent the diverse trans women's population including Sistergirls and other trans feminine peoples.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020). Prisoners in Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime-and-justice/prisoners-australia/2020#prisoner-characteristics-australia

- Australian Institute of First Nations and Torres Strait Islander Studies. (2021). Australia's First Peoples. https://bit.ly/362jwVc

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2015). The health of Australia's prisoners 2015. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/9c42d6f3-2631-4452-b0df-9067fd71e33a/aihw-phe-207.pdf

- Bali, M. (2020). Background briefing in Why was this woman sent to a men's prison? https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/backgroundbriefing/why-was-this-woman-sent-to-male-prison/12416714

- Berlin, I. (2010). The changing definition of African-American. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-changing-definition-of-african-american-4905887

- Biello, K. B., & Hughto, J. M. (2021). Measuring intersectional stigma among racially and ethnically diverse transgender women: Challenges and opportunities. American Journal of Public Health, 111(3), 344–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg, L. (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—An important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1267–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. [Google Scholar]

- Brömdal, A., Clark, K. A., Hughto, J. M. W., Debattista, J., Phillips, T. M., Mullens, A. B., Gow, J., & Daken, K. (2019a). Whole-incarceration-setting approaches to supporting and upholding the rights and health of incarcerated transgender people. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(4), 341–350. 10.1080/15532739.2019.1651684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brömdal, A., Mullens, A. B., Phillips, T. M., & Gow, J. (2019b). Experiences of transgender prisoners and their knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding sexual behaviors and HIV/STIs: A systematic review. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(1), 4–20. 10.1080/15532739.2018.1538838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brömdal, A., Halliwell, S., Sanders, T., Clark, K. A., Gildersleeve, J., Mullens, A. B., Phillips, T. M., Debattista, J., du Plessis, C., Daken, K., & Hughto, J. M. W. (2022). Navigating intimate trans citizenship while incarcerated in Australia and the United States. Feminism & Psychology, 0(0), 1–23. 10.1177/09593535221102224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K. A., White Hughto, J. M., & Pachankis, J. E. (2017). “What's the right thing to do?” Correctional healthcare providers' knowledge, attitudes and experiences caring for transgender inmates. Social Science & Medicine, 193, 80–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements, K., Katz, M., & Marx, R. (1999). The transgender community health project: Descriptive results. http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite.jsp

- Combahee River Collective. (1995). Combahee River Collective statement. In B. Guy-Sheftall (Ed.), Words of fire: An anthology of African American feminist thought (pp. 232–240). New York: New Press. (Original work published 1977). [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. (1990). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43, 1241. [Google Scholar]

- du Plessis, C., Halliwell, S., Mullens, A., Sanders, T., Gildersleeve, J., Phillips, T., & Brömdal, A. (2022). A trans agent of social change in incarceration: A psychobiographical study of natasha keating. Journal of Personality, 0(0), 1–43. 10.1111/jopy.12745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo, R., Deleon, J., Osmer, E., Doll, M., & Harper, G. W. (2006). Overlooked, misunderstood and at-risk: Exploring the lives and HIV risk of ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(3), 230–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaze, L., & Kaeble, D. (2014). Correctional populations in the United States, 2013 (NCJ 248479). Bureau of Justice Statistics. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5177 [Google Scholar]

- Glezer, A., McNiel, D. E., & Binder, R. L. (2013). Transgendered and incarcerated: A review of the literature, current policies and laws, and ethics. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 41(4), 551–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, J. M., Mottet, L., Tanis, J. E., Harrison, J., Herman, J., & Keisling, M. (2011). Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. National LGBQT Task Force. https://www.thetaskforce.org/injustice-every-turn-report-national-transgender-discrimination-survey/

- Haire, B. G., Brook, E., Stoddart, R., & Simpson, P. (2021). Trans and gender diverse people's experiences of healthcare access in Australia: A qualitative study in people with complex needs. PLoS One, 16(1), e0245889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell, S., du Plessis, C., Hickey, A., Gildersleeve, J., Sanders, T., Clark, K., Hughto, J. M. W., Debattista, J., Phillips, T., Daken, K., & Brömdal, A. (2022). A critical discourse analysis of an Australian incarcerated trans woman's letters of complaint and self-advocacy. Ethos, 50, 208–232. 10.1111/etho.12343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2016). The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

- Lydon, J., Carrington, K., Low, H., Miller, R., & Yazdy, M. (2015). Coming out of concrete closets: A report on Black & Pink's National LGBTQ Prisoner Survey. Black and Pink. http://www.blackandpink.org/wp-content/upLoads/Coming-Out-of-Concrete-Closets.-Black-and-Pink.-October-21-2015.pdf

- Lynch, S., & Bartels, L. (2017). Transgender prisoners in Australia: An examination of the issues, law and policy. Flinders Law Journal, 19(2), 185–231. [Google Scholar]

- Maruschak, L. M., & Minton, T. D. (2020). Correctional populations in the United States, 2017–2018. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Mays, V. M., & Ghavami, N. (2018). History, aspirations, and transformations of intersectionality: Focusing on gender. In C. B. Travis and J. W. White (Eds.), APA Handbook of the Psychology of Women: History, Theory, and Battlegrounds, Vol. 1 (pp. 541–566). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Mizock, L., & Mueser, K. T. (2014). Employment, mental health, internalized stigma, and coping with transphobia among transgender individuals [empirical study; interview; quantitative study]. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(2), 146–158. [Google Scholar]

- Musto, J. (2019). Transing critical criminology: A critical unsettling and transformative anti-carceral feminist reframing. Critical Criminology, 27(1), 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto, T., Bödeker, B., & Iwamoto, M. (2011). Social support, exposure to violence and transphobia, and correlates of depression among male-to-female transgender women with a history of sex work. American Journal of Public Health, 101(10), 1980–1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, T., Brömdal, A., Mullens, A. B., Gildersleeve, J., & Gow, J. (2020). “We don't recognise transexuals…and we're not going to treat you”: Cruel and unusual and the lived experiences of transgender women in US prisons. In M. Harmes, M. Harmes, & B. Harmes (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of incarceration across popular culture (pp. 331–360). Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Reisner, S. L., Bailey, Z., & Sevelius, J. (2014). Racial/ethnic disparities in history of incarceration, experiences of victimization, and associated health indicators among transgender women in the US. Women and Health, 54(8), 750–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner, S. L., Pardo, S. T., Gamarel, K. E., White Hughto, J. M., Pardee, D. J., & Keo-Meier, C. L. (2015). Substance use to cope with stigma in healthcare among U.S. female-to-male trans masculine adults. LGBT Health, 2(4), 324–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, W., & Lange, M. M. (2013). Rethinking the vulnerability of minority populations in research. American Journal of Public Health, 103(12), 2141–2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, T., Gildersleeve, J., Halliwell, S., du Plessis, C., Clark, K. A., Hughto, J. M. W., Mullens, A., Phillips, T., Daken, K., & Brömdal, A. (2022). Trans architecture and the prison as archive: “Don't be a queen and you won't be arrested”. Punishment & Society, 0(0), 1–24. 10.1177/14624745221087058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, E., & Smith, N. (Eds.). (2015). Captive genders: Trans embodiment and the prison industrial complex (2nd ed.) AK Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valdes, F. (1996). Unpacking hetero-patriarchy: Tracing the conflation of sex, gender & sexual orientation to its origins. Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities, 8(1), 161–211. https://openyls.law.yale.edu/handle/20.500.13051/7687 [Google Scholar]

- Van Hout, M. C., Kewley, S., & Hillis, A. (2020). Contemporary transgender health experience and health situation in prisons: A scoping review of extant published literature (2000–2019). International Journal of Transgender Health, 21(3), 258–306. 10.1080/26895269.2020.1772937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, B. W. (2018). Studying trans: Recommendations for ethical recruitment and collaboration with transgender participants in academic research. Psychology & Sexuality, 9(2), 102–116. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S., Spohn, C., & DeLone, M. (2016). The color of justice: Race, ethnicity, and crime in America. Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Wesp, L. M., Malcoe, L. H., Elliott, A., & Poteat, T. (2019). Intersectionality Research for Transgender Health Justice: A theory-driven conceptual framework for structural analysis of transgender health inequities. Transgender Health, 4(1), 287–296. 10.1089/trgh.2019.0039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto, J. M., Clark, K. A., Altice, F. L., Reisner, S. L., Kershaw, T. S., & Pachankis, J. E. (2018). Creating, reinforcing, and resisting the gender binary: A qualitative study of transgender women's healthcare experiences in sex-segregated jails and prisons. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 14(2), 69–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto, J. M., Reisner, S. L., & Pachankis, J. E. (2015). Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science & Medicine, 147, 222–231. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M., Simpson, P. L., Butler, T. G., Richters, J., Yap, L., & Donovan, B. (2017). ‘You're a woman, a convenience, a cat, a poof, a thing, an idiot’: Transgender women negotiating sexual experiences in men's prisons in Australia. Sexualities, 20(3), 380–402. [Google Scholar]

- Worthen, M. G. F. (2016). Hetero-cis-normativity and the gendering of transphobia. International Journal of Transgenderism, 17(1), 31–57. 10.1080/15532739.2016.1149538 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young, I. M. (2010). Responsibility for justice. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]