Abstract

Background:

The Whole Health model is a holistic approach to facilitate whole health practices by addressing (1) the physical, mental, and social health of individuals and (2) associated support systems. Several national organizations such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's (IHI) Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) movement and, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs have implemented whole health frameworks with many common elements and promoted whole health practice and skills. However, implementing a Whole Health model across communities and health systems will require evidence of effectiveness. Generating evidence on the effectiveness of the Whole Health model's effect on health outcomes requires data-driven intelligence.

Methods:

We identified the national public-use data sets that are most often used in health research with a machine-assisted literature search of PubMed and Scopus for peer-reviewed journal articles published from 2010 through the end of 2021, including preprints, using Python [3.7]. We then assessed if the 8 most commonly used datasets include variables associated with whole health.

Results:

The number of publications examining whole health has increased annually in the last decade, with more than 2800 publications in 2020 alone. Since 2010, 24,811 articles have been published using 1 of these data sets. However, we also found a lack of data (ie, data set includes all of the whole health variables) to examine whole health in national data sets.

Conclusions:

We support a call to expand data collection and standardization of critical measures of whole health.

Keywords: whole health, person centered, health outcomes, biopsychosocial

Introduction

The World Health Organization defines health as the “state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”1 However, this definition has been expanded to include the multifacets of health. For example, the whole health perspective emphasizes a holistic approach to facilitate whole health practices by addressing (1) the physical, mental, and social health of individuals and (2) associated support systems. Recently, the Whole Health model has gained renewed attention due to the recognition that most of activities promoting health among individuals occur outside of medical care. Nearly 80% of health issues arise from factors rarely addressed within the health care system.2

The Whole Health model is disease-agnostic, whole-person approach to health. It is in contrast to a biomedical, disease-centered, and treatment approach. The biomedical model often neglects the personal and social dimensions of health and illness that are integral in the Whole Health model. Although the Institute of Medicine3 calls for new integrated and patient-centered approaches, much of the health care delivery remains disease centered. The concept of whole health not only goes beyond the reductionist vision of biomedicine, but it also goes beyond the biopsychosocial model4 and its extensions to consider the individual's biology, psychology, social situation,5 and emerging technological advances. It addresses some of the root causes of poor health of individuals, populations, and communities.

The concept of health has had a long elusive history and is no longer considered just the “absence of disease” or is it “complete physical, mental, and social well-being.”6 The concept of “holistic health” or viewing the whole person and not just the manifestations of the condition or disease and emphasized the interaction of physical and mental health was first referred to by Jan Smuts in 1926.7 By the 1960s, preventive medicine started to take hold to include the practice of public health to include the community and the social and behavioral aspects of health.8

Starting in the 1970s, there was a dramatic increase in the number of US medical schools teaching complement and alternative medicine (eg, acupuncture, homeopathy), extended the new perspectives on health and well-being.9 By 2000, in response to Crossing the Quality Chasm3 delineated the need for integrative medicine that accentuates the primary nature of the physician–patient relationship and focuses on conventional health care but extends health to include lifestyle factors such a diet, exercise, and stress management as well as preventive care and emotional well-being.10 Today, health is more about prevention of disease and promotion of health, including the environment in which the individual lives.7

Therefore, with this history, we focus on “whole health” and patient-centered care as in relationship between the patients and their community, including their providers, and the importance of self-care strategies that bolster inherent healing.9 Health has become a measure of person-centered care and how the patient can adapt to the health condition.

Underlying the whole health perspective is the biopsychosocial model of health. The biopsychosocial model, promoted by George Engel in 1977,4 extending an early notion of mind–body connection in 188611 and work in the 1950s by Roy Grinker,12 was an attempt to move the focus of medicine to a reductionist biomedical perspective to the more holistic view of mind and body health grounded in systems theory.13 The shift to a biopsychosocial model seemed to a response from the field of medicine's disease model that seemed inadequate for both the scientific tasks and social responsibilities of medicine or psychiatry by not accounting for the social context of the patient, the role of the physician, and the health care system.14

Despite the growing recognition of the biopsychosocial model in medicine, it is not without critique. Such critiques include the observation that model suggests all mental illnesses are biopsychosocial that may lead to poor treatment and that we must be careful in how we define and interpret the use of the model.13 Also, the 3 components of biology, psychology, and social interaction are not weighted equally and the boundaries between the 3 components are not clear,13 leading to an eclecticism or mixing of many different approaches.13

The criticisms from the field about the psychosocial model are evidenced in the literature,12,14,15 yet the emergence of concept of social determinants of health (SDOH) seems to emphasize the need to consider health with a wider and more holistic lens. A significant body of literature has been amassed to document the impact of SDOH on health including elements such as educational attainment, social environment, economic stability, and food security16–19 In fact, researchers have demonstrated that using a set of SDOH factors could identify individuals with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (using a validated polysocial risk score (ie, a cumulative social disadvantage score) based on SDOH variables, going beyond traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as demographics and traditional clinical risk factors.19

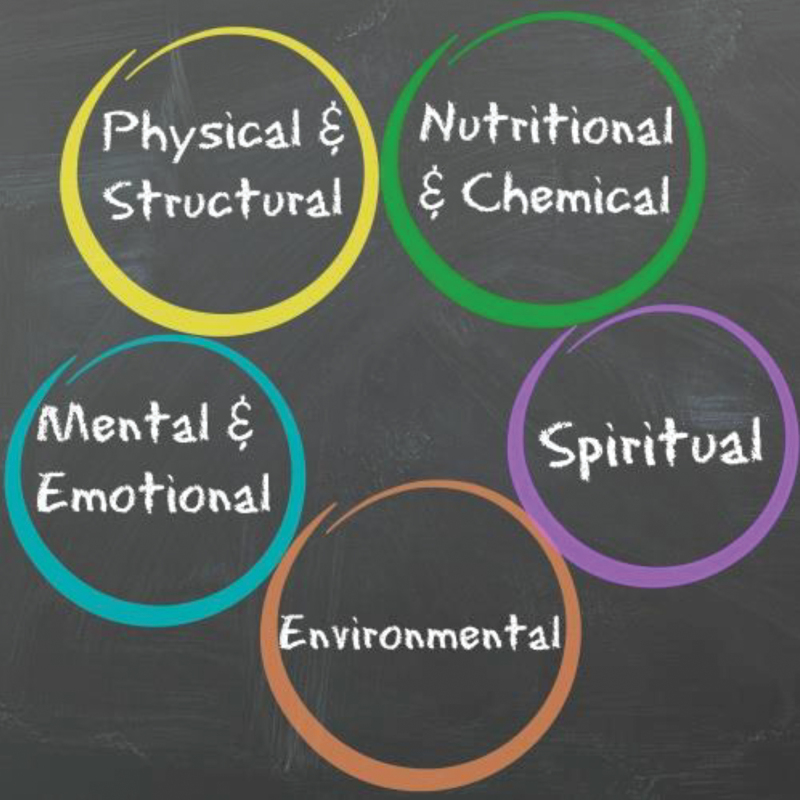

The whole health perspective in health care, based on prior work of Engel,4 Romano, and Grinker,11 started in Boston, 1977, with the National Institute of Whole Health (NIWH), an educational organization focusing on whole health education.20 NIWH focuses on a “whole person” approach connecting physical and structural, nutritional and chemical, mental and emotional, and spiritual and environmental pillars together rather than just targeting the health condition in isolation. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs developed the Whole Health model in 201421 and refers it as a “cycle of health,” which includes self-care, professional care, and the community. In 2019, a Whole Health Institute was founded to broaden the whole health concept to all communities.20

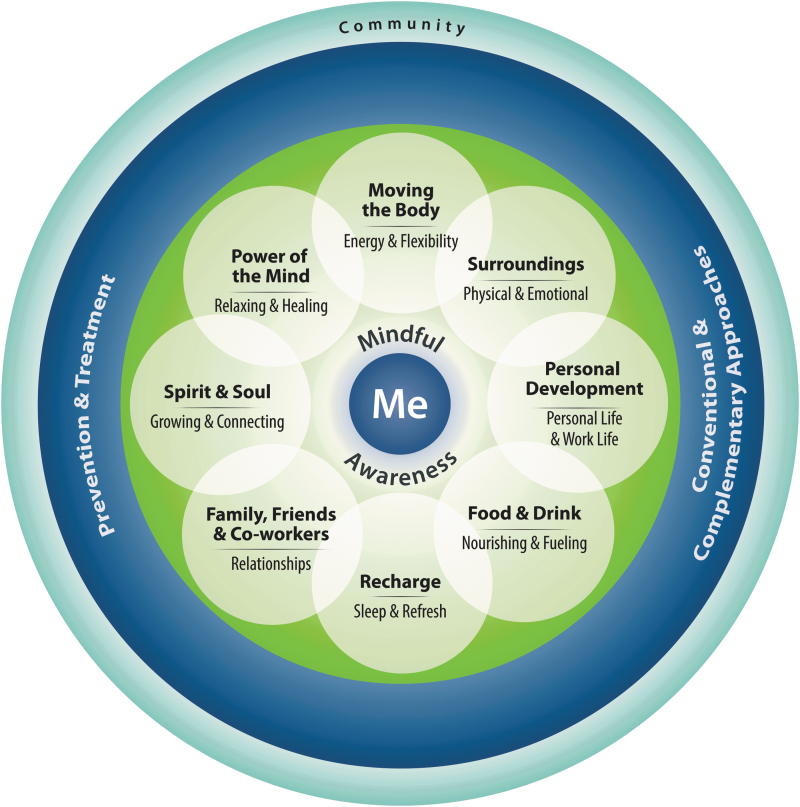

The versions of the whole health concept have different emphases: The NIWH emphasizes 5 domains (physical, nutritional, mental, spiritual, and environmental) (Fig. 1). The VA model emphasizes a circle of health with 4 overarching domains (mindful awareness, self-care, professional care, and the community) and 8 areas of self-care such as food and drink, recharge, relationships, spirit and soul, power of the mind, moving the body, surroundings, and personal development (Fig. 2). The tagline for the approach is “what matters to you; not what is the matter with you.” VA defines community as “all the people and groups you connect with; who rely on you and upon whom you rely.”22

FIG. 1.

The 5 aspect of Whole Health model developed by the NIWH. Figure used with permission from the NIWH, (https://www.wholehealtheducation.com/). NIWH, National Institute of Whole Health.

FIG. 2.

VA circle of health. Circle of health figure used with permission from Dryden et al.21

The Whole Health Institute, the VA, and the TakeCare.org share the same philosophy, extended the NIWH model of mind, body, spirit, and community.22 Similar to other figures, TakeCare.org uses 4 overlapping circles to highlight the role of Mind representing the stories we believe, Body as the actions we take, Spirit as the strengths we have, and Community as the relations we share all connected to Me as the center anchor: all these aspects promote health.

All these frameworks are very flexible and propose common core elements of a Whole Health model. Whereas the concept of whole health includes personal body, mind, environmental, and community, there is much variability in how the concept is applied.

However, some common themes have emerged from the 3 frameworks: (1) disease agnostic; (2) person-centered holistic approach; (3) mindful awareness; (4) integration of traditional and complementary therapies; (5) self-care as a pillar of health and well-being; (6) recognition of community and SDOH; and (7) care supported by health systems, programs, and policies.

Promotion of whole health practices among individuals, populations, and communities requires scoping the field and operationalizing the model for real-world practices. Efforts are underway by the National Academics of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in scoping the field examples, accomplishments, effective strategies, and factors that influence whole health.23 There have been studies examining components of Whole Health model on clinical, humanistic, and economic outcomes.

A peer-led whole health action management program has been shown to improve physical and emotional health and other outcomes such as paid employment among people with serious mental illness and co-occurring medical conditions.24 A review of 125 studies focused on integrative health care as the intersection of self-care, conventional medicine, and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) found heterogeneity in the approach and benefits in improving clinical outcomes and decreasing costs in primary care.25

Most of the studies on whole health have been focused on veterans26 because the U.S. Veterans Health Administration (VHA) implemented a whole health, patient-driven, personalized, and proactive approach for veterans.27 The VHA developed clinical policies, educational initiatives, and research strategies to encourage the use of the Whole Health model for the best possible care.28 Therefore, the VHA has begun to evaluate programs that use the Whole Health approach. In 1 attempt, researchers found that the employees thought that the approach had a meaningful impact on the well-being of the employees themselves as well as their workplace.29

Another study among veterans is in process to determine that whole health program evaluation is a randomized controlled trial to compare chronic pain management to see whether the whole health approach was superior to the Primary Care Group Education Approach.30 The evaluation had been interrupted due to COVID-19.30

One of the difficulties of the new approach is how to measure success. The only option is to operationalize behavioral outcomes as it is only possible to see the endpoints—type of diet, quality of sleep, exercise practices, social/emotional support, mind/body/religious practices, for example. Regardless of the approaches to whole health, evaluating Whole health in real-world practices requires measurements of the components of whole health. However, currently available health care data are centered on disease-specific treatment or disease-driven care, most collected variables available for a program evaluation in secondary data analyses are focused on deficits such as whether a person received care according to clinical guidelines.31

With the emphasis on person centeredness and well-being, researchers need operational definitions of variables of critical elements of whole health. Currently, even ecological studies that use combined national studies are not possible because wellness data are collected at different years in national data sets. For example, in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), mind–body therapies are not collected every year. Although the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) collects nutrition information, it is challenging to combine these measures across data sets due to variations in period of measurement. Therefore, our research team attempted to identify data on measures of whole health in national health-related public use data sets.

Methods

First, we considered national data sets that are often used in evaluating preventive care,32 health disparities, and quality of health care by national organizations such as Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to inform health policies.33 We identified 8 national data sets that are as follows: (1) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), (2) Health and Retirement Study (HRS), (3) Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), (4) Medical Expenditure Panel (MEPS), (5) NHIS, (6) NHANES, (7) National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP), and (8) Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID).

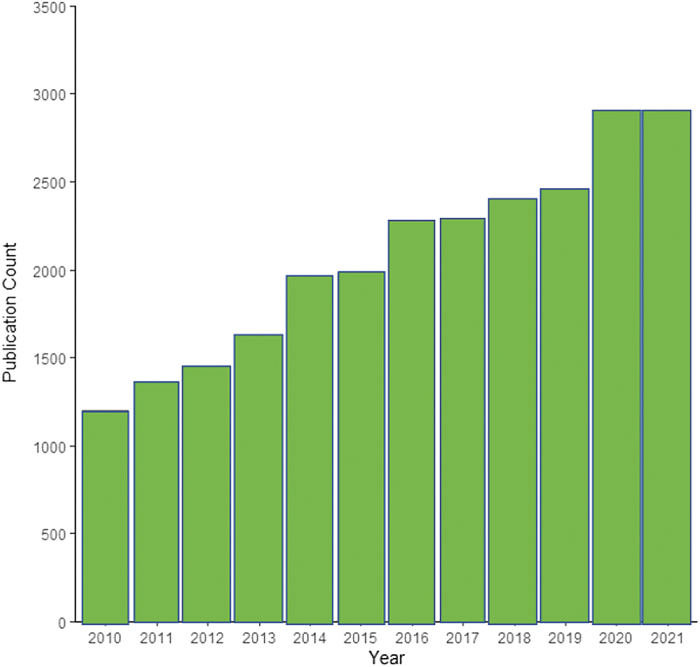

We examined the use of these 8 national data sets as determined by the number of scholarly publications, with a machine-assisted literature search using Python [3.7] to search PubMed and Scopus for peer-reviewed journal articles published from 2010 through the end of 2021, including preprints. The search queries involved the full name of each data set and the abbreviated name for BRFSS, NHANES, and MCBS. Other abbreviated names were commonly associated with different terms and concepts; therefore, they were excluded. After the initial search, the results were combined and deduplicated before being visualized in R [4.1.1] (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Publications by 8 national public use data sets.

Second, we sought to identify variables in each of the 8 national data sets that cover the components of the whole health model. These included sleep hygiene variables (hours of sleep, daytime sleepiness, Pittsburgh Sleep Index), diet and/or nutrition variables (fruits per day, vegetables per day), physical activity associated variables (meeting the minimum of recommended exercise/week, body mass index), mental health variables (Kessler 6 Index, depression diagnosis, nervousness, hopelessness, restlessness, effort, worthlessness), and mind–body variables (use of complementary or alternative medicines, meditation, yoga). In each category, “other” variables were also considered that included various topics related to each component such as physical activity limitations, cognition issues, trouble falling asleep, and whether specialty diets such as high-fact or low-cholesterol diets were followed.

We chose keywords relating to each component and conducted searches for the variables from 2010 to 2021 from multiyear indices where available (NHANES, NHIS, PSID, NSHAP). If such an index was not available, codebooks from 2015 to 2021 were searched individually with the same keywords (BFRSS, MEPS, HRS, MCBS). Resulting variables were reviewed to determine whether they were accurately related to the relevant component (eg, if the physical activity measure only included an indicator variable covering a monthly period rather than weekly minutes). Remaining variables were sorted into the appropriate whole health component to determine which components were present in which data sets. This study was reviewed and considered non-human subjects research by the Rutgers University Institutional Review Board.

Results

Figure 3 presents results of the machine-assisted literature search. It shows the number of peer-reviewed journal articles published from 2010 to 2021 that used 8 national data sets. From 2010 to 2021, 24,811 articles have been published using these data sets. The number of publications using these data sets has increased annually in the past decade, from 1200 publications in 2010 to 2800 publications in 2020.

Next, variables for the assessment of the Whole Health model from these 8 national data sets were reviewed. Table 1 gives the components of the whole health assessment covered in these data sets. Three data sets (NHANES, NHIS, PSID) provided data on 4 components of Whole Health. Four data sets (BRFSS, HRS, MCBS, NSHAP) had data covering 3 components. Finally, MEPS provided data on 2 components.

Table 1.

Whole Health Variables Available by National Public Use Databases

| NHANES | BFRSSa | MEPSa | NHIS | HRSa | MCBSa | PSID | NSHAP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recharge/sleep | ||||||||

| Hours of sleep | X | X | X | |||||

| Daytime sleepiness | X | X | ||||||

| Pittsburgh index | X | |||||||

| Other | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Diet/nutrition | ||||||||

| Fruits per day | X | X | ||||||

| Vegetables per day | X | X | ||||||

| Other | X | X | X | |||||

| Physical activity | ||||||||

| Minimum of exercise/week | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| BMI | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Other | X | X | ||||||

| Mental health | ||||||||

| Kessler 6 index | X | X | ||||||

| Depression diagnosis | X | X | ||||||

| Nervous | X | X | ||||||

| Hopeless | X | X | ||||||

| Restless | X | |||||||

| Depressed | X | |||||||

| Everything is an effort | X | |||||||

| Worthless | X | |||||||

| Other | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Mind–body | ||||||||

| Ever used CAM | X | |||||||

| Meditation | X | X | ||||||

| Yoga | X | |||||||

| Other | ||||||||

Codebooks from 2015 to 2020 were searched individually as there was no index of variables.

BFRSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; BMI, body mass index; CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; HRS, Health and Retirement Study; MCBS, Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey; MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NHIS, National Health Interview Survey; NSHAP, National Social Life, Health and Aging Project; PSID, Panel Study of Income Dynamics.

When different types of components were compared among national data sets, mental health was covered in all data sets, physical activity was in 7 out of 8 data sets, recharge/sleep was included in 5 data sets, and diet/nutrition and mind–body were only in 3 data sets, indicating a lack of standardization on whole health assessment. None of the data sets had any information on the connections between the individual and the community.

Discussion

Results from our examination of 8 increasingly used national data sets suggest that there is a lack of complete data to measure whole health and its components. This lack of data contributes to a lack of research on whole health and what may lead to whole health. The current data represent diverse and incomplete measurement of Whole Health with inconsistencies in the major domains reported. Therefore, it is important to operationalize and standardize measures of whole health so that the model can be monitored for improvements and implementable in the real world. There have been many toolkits developed for universal measurements of health phenomena, such as PhenX for COVID-19.34

A toolkit for whole health would be a significant contribution to the research community so that programs, policies, and research can benefit. Such standardization can also help the use of mobile apps for whole health. Mobile health apps are fast growing and used by individuals to monitor diabetes and depression, among other chronic conditions.35 In fact, VHA has implemented a mobile health app for whole health. Mobile health apps that collect disease-agnostic data and integrate the information into a data ecosystem are needed.

We believe that the foundational principle is person-centered rather than the disease-driven approach that focuses more on the disease than the person. A whole health approach that meets each person's specific values, needs, priorities/goals, and improve health outcomes of persons cannot be universal and should be tailored to each individual's goals such as the one implemented by the VHA.28 Each pillar of the Whole Health model can be emphasized differently once the persons are provided appropriate education and training in setting goals for preventive self-care and wellness.

In addition, the development of the Whole Health model emphasizes health care equity for each individual, regardless of their gender, race, or ethnicity. Though the current whole health models identify several dimensions to personalized whole health, the key structural components will be the individual (eg, physical and mental) and the surroundings of the individual (eg, environment and community) and how to connect them.

At present, more whole health education courses and programs have been developed with limited research supporting them. Early evaluations of this approach indicated improved health outcomes, well-being, costs, and reductions in fragmented care. Moreover, the findings of the current studies focused more on the individual's self-care, including physical, mental, and spiritual factors, but less evidence was found on the connections between the individual and the community. Knowing the current literature gap in interpreting the Whole Health model and evaluating the value of implementing the Whole Health model are essential.

Conclusion

There is a lack of concurrent measurement of multidimensional wellness data related to whole health in national databases, which are often used to benchmark disparities, quality of care, and develop national health policies. The national databases need to include whole health components for any evaluations of whole health approach in improving health and well-being of individuals and populations. Although we emphasize the need for personalized whole health care, we also recognize the need to develop standardized measures that can inform the person-centered approach. Therefore, we support a call to (1) collect data on whole health and its domains (ie, components) and (2) develop a standardized measure of diverse components of whole health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

National Institutes of Health: 5U54MD006882 and National Institute of General Medical Sciences, 5U54GM104942-07. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Constitution, Geneva, Switzerland. 1946. [Google Scholar]

- 2. McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff 2002;21:78–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001. PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977;196:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Card AJ. The biopsychosociotechnical model: a systems-based framework for human-centered health improvement. Health Syst 2022;1–21. 10.1080/20476965.2022.2029584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Books Z. What is health? The ability to adapt. Lancet 2009;373:781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Northup GW. Holistic medicine: a matter of definition. J Am Osteopathic Assoc 1987;87:68. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brokaw JJ, Tunnicliff G, Raess BU, et al. The teaching of complementary and alternative medicine in US medical schools: a survey of course directors. Acad Med 2002;77:876–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Snyderman R, Weil AT. Integrative medicine: bringing medicine back to its roots. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:395–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krejci LP, Carter K, Gaudet T. Whole health: the vision and implementation of personalized, proactive, patient-driven health care for veterans. Med Care 2014;52:S5–S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davis JE. Biomedicine and its cultural authority. New Atlantis 2016;60–77. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ghaemi SN. The rise and fall of the biopsychosocial model. Br J Psychiatry 2009;195:3–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hatala AR. The status of the “biopsychosocial” model in health psychology: towards an integrated approach and a critique of cultural conceptions. Open J Med Psychol 2012;1:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ghaemi SN. The biopsychosocial model in psychiatry: a critique. Am J Psychiatry 2011;121:451–457. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Benning TB. Limitations of the biopsychosocial model in psychiatry. Adv Med Educ Pract 2015;6:347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Federico MJ, McFarlane II AE, Szefler SJ, et al. The impact of social determinants of health on children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020;8:1808–1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mannoh I, Hussien M, Commodore-Mensah Y, et al. Impact of social determinants of health on cardiovascular disease prevention. Curr Opin Cardiol 2021;36:572–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jones KG, Roth SE, Vartanian KB. Health and health care use strongly associated with cumulative burden of social determinants of health. Popul Health Manage 2022;25:218–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Javed Z, Valero-Elizondo J, Dudum R, et al. Development and validation of a polysocial risk score for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Am J Prev Cardiol 2021;8:100251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Institute of Whole Health. National Institute of Whole Health. 2022. https://www.wholehealtheducation.com/ Accessed February 10, 2022.

- 21. Dryden EM, Bolton RE, Bokhour BG, et al. Leaning into whole health: sustaining system transformation while supporting patients and employees during COVID-19. Global Adv Health Med 2021;10:21649561211021047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. Whole Health. 2022. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth/ Accessed February 10, 2022.

- 23. The National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine. Transforming Health Care to Create Whole Health: Strategies to Assess, Scale, and Spread the Whole Person Approach to Health. 2022. https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/transforming-health-care-to-create-whole-health-strategies-to-assess-scale-and-spread-the-whole-person-approach-to-health Last accessed November 12, 2022.

- 24. Cook JA, Jonikas JA, Burke-Miller JK, et al. Whole health action management: a randomized controlled trial of a peer-led health promotion intervention. Psychiatr Serv 2020;71:1039–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jonas WB, Rosenbaum E. The case for whole-person integrative care. Medicina 2021;57:677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dougherty P, McCarten J, Ashrafioun L. Individual barriers to implementation of whole health for pain management among Veterans. J Altern Complement Med 2021;27:379–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marchand WR, Beckstrom J, Nazarenko E, et al. The Veterans Health Administration whole health model of care: early implementation and utilization at a large healthcare system. Mil Med 2020;185:e2150–e2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kligler B, Cotter A, Roca H, et al. Whole health/integrative health in the VHA: focusing on what matters to the veteran rather than what is the matter with them. Explore (New York, NY) 2017;13:274–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reddy KP, Schult TM, Whitehead AM, et al. Veterans Health Administration's Whole Health System of Care: supporting the health, well-being, and resiliency of employees. Glob Adv Health Med 2021;10:21649561211022698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Seal KH, Becker WC, Murphy JL, et al. Whole Health Options and Pain Education (wHOPE): a pragmatic trial comparing whole health team vs primary care group education to promote nonpharmacological strategies to improve pain, functioning, and quality of life in Veterans—rationale, methods, and implementation. Pain Med 2020;21(Supplement_2):S91–S99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gaudet T, Kligler B. Whole health in the whole system of the veterans administration: how will we know we have reached this future state? J Altern Complement Med 2019;25(S1):S7–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Taksler GB, Pfoh ER, Martinez KA, et al. Comparison of National Data Sources to assess preventive care in the US population. J Gen Intern Med 2022;37:318–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. US Department of Health and Human Services. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2022. https://www.ahrq.gov/ Last accessed November 12, 2022.

- 34. Hamilton CM, Strader LC, Pratt JG, et al. The PhenX Toolkit: get the most from your measures. Am J Epidemiol 2011;174:253–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Anderson K, Burford O, Emmerton L. Mobile health apps to facilitate self-care: a qualitative study of user experiences. PLoS One 2016;11:e0156164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]