Abstract

Background:

Data on dementia prognosis among ethnic minority groups are limited in Europe.

Objective:

We assessed differences in short-term (1-year) and long-term (3-year) mortality and readmission risk after a first hospitalization or first ever referral to a day clinic for dementia between ethnic minority groups and the ethnic Dutch population in the Netherlands

Methods:

Nationwide prospective cohorts of first hospitalized dementia patients (N = 55,827) from January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2010 were constructed. Differences in short-term and long-term mortality and readmission risk following hospitalization or referral to the day clinic between ethnic minority groups (Surinamese, Turkish, Antilleans, Indonesians) and the ethnic Dutch population were investigated using Cox proportional hazard regression models with adjustment for age, sex, and comorbidities.

Results:

Age-sex-adjusted short-term and long-term risks of death following a first hospitalization with dementia were comparable between the ethnic minority groups and the ethnic Dutch. Age- and sex-adjusted risk of admission was higher only in Turkish compared with ethnic Dutch (HR 1.57, 95% CI,1.08–2.29). The difference between Turkish and the Dutch attenuated and was no longer statistically significant after further adjustment for comorbidities. There were no ethnic differences in short-term and long-term risk of death, and risk of readmission among day clinic patients.

Conclusion:

Compared with Dutch patients with a comparable comorbidity rate, ethnic minority patients with dementia did not have a worse prognosis. Given the poor prognosis of dementia, timely and targeted advance care planning is essential, particularly in ethnic minority groups who are mired by cultural barriers and where uptake of advance care planning is known to be low.

Keywords: Dementia, ethnic minority groups, ethnicity, Netherlands

INTRODUCTION

Dementia is one of the leading causes of morbidity and disability among the elderly [1]. Studies in the United States of America (US) found higher rates of dementia among ethnic minority groups than in White Americans [2–7], whereas others reported no differences between the ethnic groups [8, 9]. Evidence in Europe suggests that ethnic minority groups, in general, have a higher prevalence of dementia than the European host populations [10, 11]. Furthermore, studies also found important differences in dementia incidence between African origin populations living in different geographical locations [12, 13], pointing toward the relevance of environmental factors [14].

Despite the relevance of dementia, studies into prognosis of dementia in ethnic minority groups are very limited. A worse prognosis has been reported for White Americans relative to ethnic minority groups in the US despite their lower prevalence and incidence of dementia [15–17]. In Europe, such data are completely lacking. Given the aging of ethnic minority groups in Europe, physicians will be confronted more and more with demented patients from various ethnic groups. Information on prognosis after dementia is relevant for advanced care planning as well as for public health policy makers.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess differences in short-term (1-year) and long-term (3-year) mortality risks after a first hospitalization or referral to a day clinic for dementia between ethnic minority groups and the Dutch ethnic population (henceforth, the Dutch). Furthermore, we assessed differences in readmission risk between ethnic minority groups and the Dutch.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Databases

A cohort of patients with dementia was constructed through data linkage of several Dutch national registers: hospital discharge register (HDR), population register, and national cause of death register. The HDR registers medical and administrative data for all admitted and day clinic patients visiting a Dutch hospital; no information from outpatient visits and nursing home residents was available. Patients in the Netherlands are referred to the day clinic either in case of memory-related disorders or with multiple health problems. The HDR contains information on patients’ demographics, admission data, and primary and secondary diagnoses at admission. The primary and secondary discharge diagnosis is determined at discharge and coded using the 9th version of the international classification of disease codes (ICD-9 codes)[18]. The population register contains information on all registered citizens residing in the Netherlands, including date of birth, sex, current address, and postal code. The national cause of death register contains information on date of death and causes of death. The overall validity of these registers are high [19].

Cohort identification

To construct a cohort of patients with dementia first ever hospitalized or first ever referred to the day clinic for dementia, all patients with either a principal or secondary diagnosis of dementia (ICD-9 codes 290.0; 290.1; 290.3; 290.4; 294.1; 331.0; 331.1; 331.82) aged between 60 and 100 years were selected from the HDR between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2010. In the Dutch population, there are about 2.9 million people age 60 years and older. A recent validation study showed high validity of the use of ICD-9 codes to identify patients with dementia (positive predictive value was 93.2%) [20]. Included patients were linked to the population register and the national cause of death register using a personal identifier. This identifier was assigned to each individual in the population register with a unique combination of postal code, gender, and date of birth to ensure all cases were unique. This approach resulted in a study population consisting of 59,201 patients.

Privacy issues

Linkage of data from the different registries was performed in agreement with the privacy legislation in the Netherlands [21]. All linkages and analysis were performed in a secure environment of Statistics Netherlands.

Determinants

Ethnic background

Ethnic minority groups were constructed based on the country of birth of the resident and his/her parents. A person was considered an ethnic minority if he/she was born abroad and at least one of the parents was born abroad. Persons with both parents born in the Netherlands were considered as the ethnic Dutch population [22].

Comorbidity

The presence and extent of comorbidity was defined using a modified Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) by Quan et al., which has been proved to be a valid and reliable method to measure comorbidity in clinical research [23]. This updated version of the CCI was originally based on 12 weighted discharge diagnoses (heart failure, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, rheumatologic disease, mild liver disease, moderate or severe liver disease, diabetes mellitus with chronic complications, hemiplegia or paraplegia, renal disease, any malignancy, metastatic solid tumor, and AIDS/HIV). The CCI ranges from 0 to 24 points, zero points representing no comorbidity. Dementia was excluded from this index because participants in our cohort did not have a previous hospital admission with dementia. Total scores per individual were subdivided into three different groups: 0–2 and ≥3.

Outcome measures

One (1-year) and three year (3-year) mortality risks were defined as risk of death within one and three years, respectively, after the index visit for dementia. Readmission risk was defined as the risk of a first hospital admission after the index visit with dementia.

Data analysis

Baseline characteristics were calculated for all ethnic groups. Continuous data were summarized as mean and standard deviation or as median and interquartile range where appropriate. Categorical data were summarized as percentages. Patients were followed up from their earliest date of a first hospitalization or visit at the day clinic, until the end of the study period (December 31, 2010) or until death of the patient. Cox proportional hazard regression analyses adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidity were performed to identify differences in prognosis (mortality and all cause readmission risk) after a hospital visit (inpatient or day clinic visit) for dementia between ethnic minority groups and the Dutch (reference group). Because of the important differences in disease severity between hospitalized and day clinic dementia patients and subsequent effect on prognosis, we stratified the analyses by admission type. To check for violation of the proportional hazard assumptions we inspected log-minus-log survival plots. SPSS software version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for analysis. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population

Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients with a first hospitalization or day clinic visit for dementia between 2000 and 2010. In total, 55,827 patients with Dutch, Indonesian, Turkish, Surinamese, and Antillean ethnic backgrounds were identified through record linkage of the HDR with the population register and the national cause of death register and were included in the analysis. Other ethnic groups were excluded because of small numbers (n = 3,374). Except for Indonesians, all ethnic minority groups were younger than the Dutch. Turkish were more likely and Indonesians and Surinamese were less likely than the Dutch to be married or living together with a partner. Compared with the Dutch, AD diagnosis was significantly less common in Surinamese, whereas vascular dementia was significantly more common in Surinamese and Turkish people. Turks also had significantly higher comorbidities than the Dutch. The mean follow-up in months was shorter in Dutch than in ethnic minority groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with a first hospitalization or day clinic visit for dementia in The Netherlands between 2000 and 2010

| Ethnic Dutch | Indonesian | Surinamese | Turkish | Antillean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 53,999 | 1,344 | 312 | 100 | 72 |

| Female (%) | 61.0 | 63.1 | 61.2 | 40.0* | 58.3 |

| Age Mean (SD) | 81.5 (7.0) | 81.2 (7.0) | 77.6 (8.4)* | 72.9 (6.4)* | 76.9 (8.9)* |

| Married/living together | 35.8 | 30.5* | 28.2* | 68.0* | 34.7 |

| Person-years at risk | |||||

| Day clinic | 42,412 | 1,206 | 339 | 112 | 77 |

| Inpatients | 60,940 | 1,434 | 375 | 70 | 65 |

| N events (deaths) | |||||

| Day clinic | 7,737 | 185 | 50 | 11 | 11 |

| Inpatients | 28,137 | 654 | 122 | 31 | 29 |

| Dementia diagnosis | |||||

| Alzheimer’s Disease | 62.5 | 62.8 | 54.8* | 55.0 | 59.7 |

| Vascular Dementia | 12.4 | 12.5 | 18.9* | 24.0* | 6.9 |

| Other | 25.1 | 24.7 | 26.3 | 21.0 | 33.4 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |||||

| 0 | 81.9 | 83.0 | 80.8 | 72.0* | 80.6 |

| 1–2 | 15.5 | 14.2 | 15.4 | 23.0* | 15.3 |

| ≥3 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.8 | 5.0 | 4.2 |

| Follow up (months) | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 24 (23.6–24.4) | 27 (23.9–30.1) | 37 (27.5–46.5) | 40 (26.5–54.4) | 33 (20.6–45.4) |

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range;

p-value <0.05 for ethnic minority group versus Dutch.

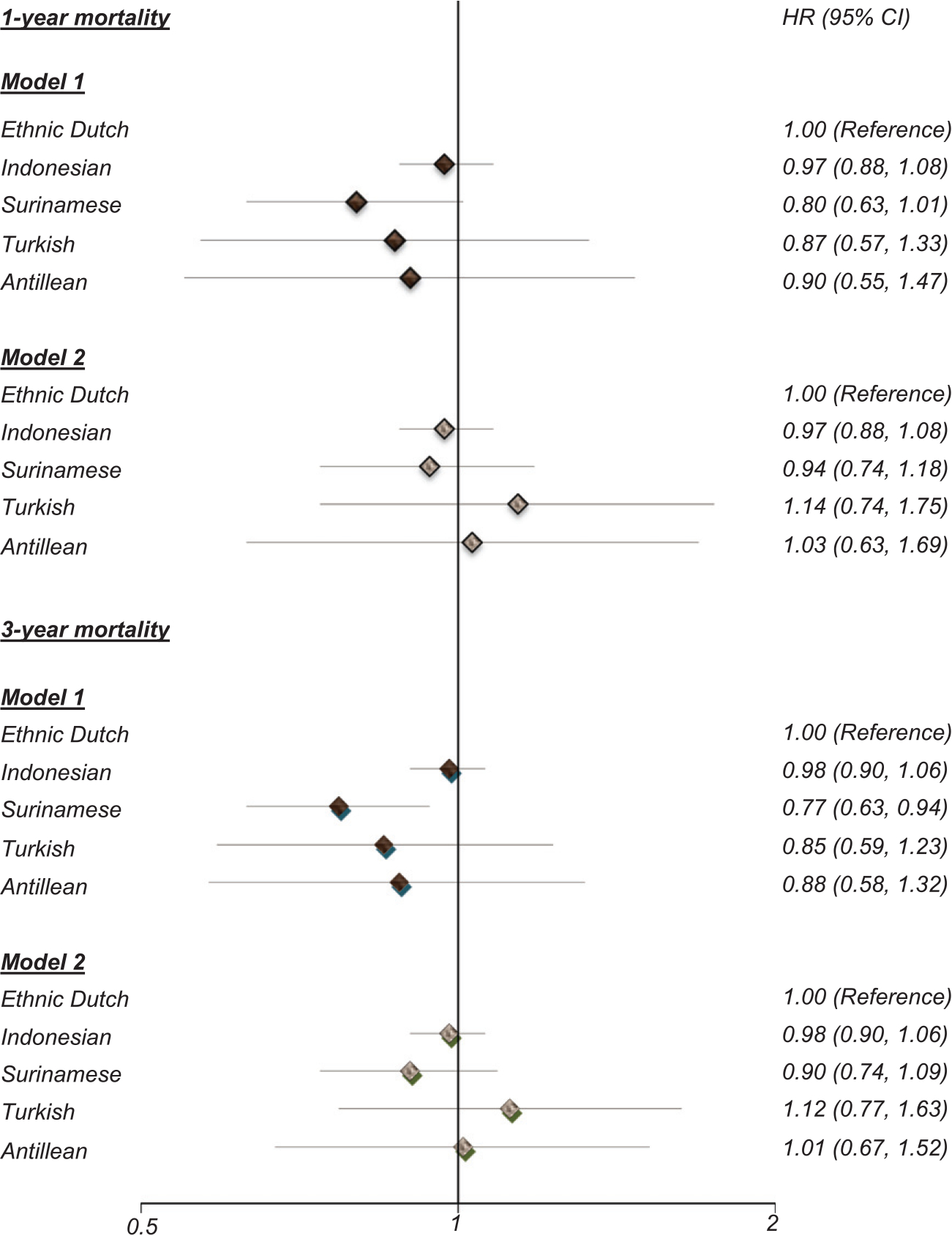

Ethnic differences in mortality risk after a first hospitalization for dementia

Figure 1 shows differences in short-term and long-term mortality risks after a first hospitalization with dementia between the ethnic groups. Absolute short-term mortality risk ranged from 40% in Antillean to 45% in the Dutch. Long-term risks ranged from 60% in Surinamese and 71% in the Dutch. In an unadjusted model, both short- and long-term risks of death were lower in Surinamese than Dutch people (HR 0.80; 95% CI, 0.63–1.01 and 0.77; 95% CI, 0.63–0.94, respectively) although the short-term risk of death was of borderline statistical significance. These differences were abolished after adjustment for age and sex (HRs 0.93; 95% CI, 0.73–1.17 and 0.89; 95% CI, 0.73–1.08, respectively). Further adjustment for comorbidities did not change the results. There were no significant differences between the other ethnic minority groups and the Dutch.

Fig. 1.

Difference in short-term and long-term mortality risk after a first hospitalization for dementia between the ethnic minority groups and Dutch population between 2000 and 2010. Model 1: crude, Model 2: Adjusted for age, sex and comorbidity.

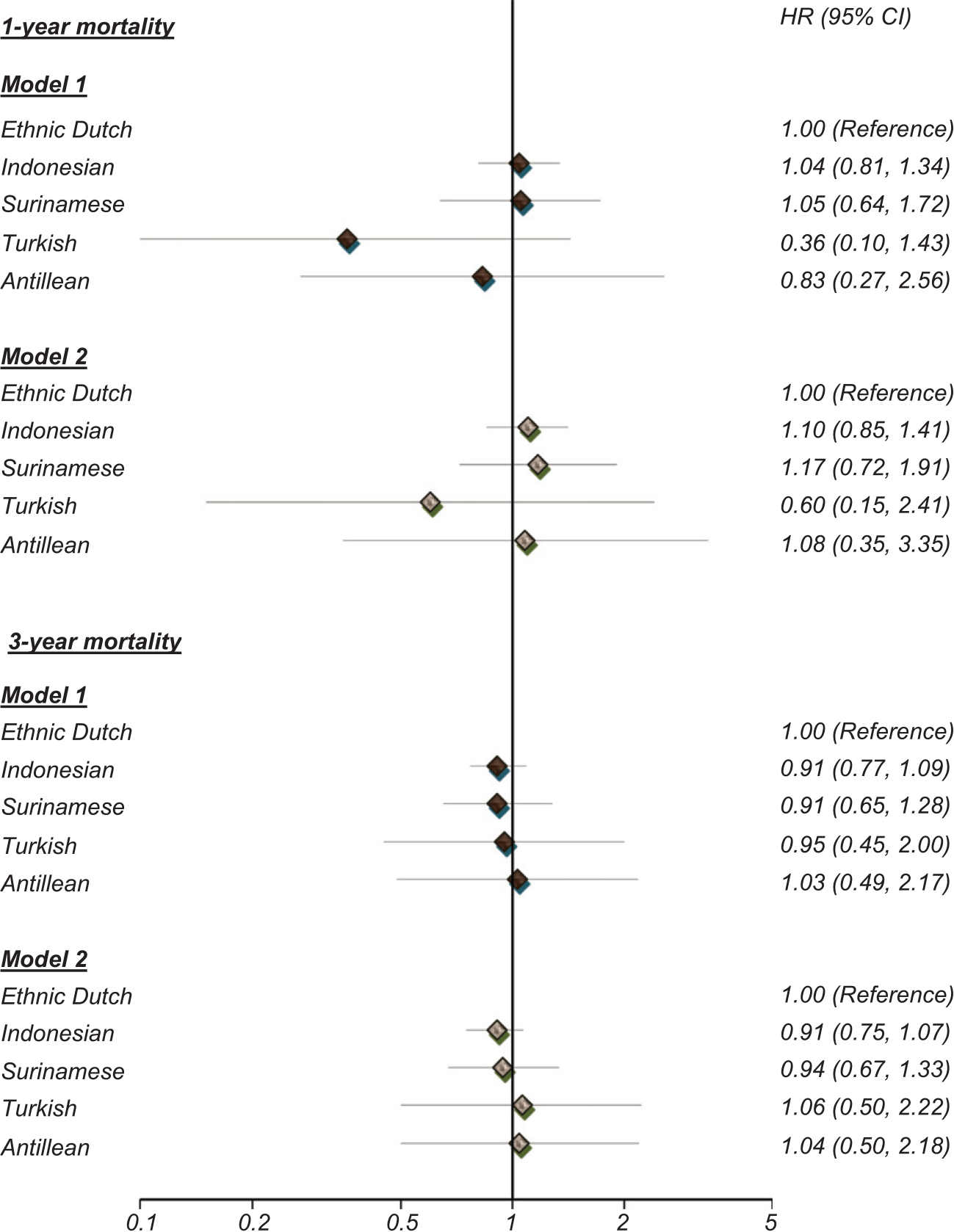

Ethnic differences in mortality risk after a first day clinic visit with dementia

Absolute short-term risk of death was approximately 15% in all ethnic subgroups, whereas long-term risks of death ranged from 34% in Antillean to 39% in the Dutch. Figure 2 shows differences in short-term and long-tern risk of death following first day clinic visit with dementia between the ethnic groups. Both crude and adjusted short-term and long-term risks of death did not differ between ethnic minority groups and their Dutch counterparts.

Fig. 2.

Difference in short-term and long-term mortality risk after a first day clinic visit for dementia between the ethnic minority groups and Dutch population between 2000 and 2010. Model 1: crude; Model 2: Adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidity.

Ethnic differences in readmission risk after first hospitalization and day clinic visit with dementia

Table 2 shows the readmission risk after a first hospitalization or a first day clinic visit with dementia among the ethnic groups. Except for Indonesians, all the ethnic minority groups had a higher risk of readmission with the crude differences being significantly higher in Turkish (HR 1.85; 95% CI, 1.27–2.69) and Surinamese (HR 1.25; 95% CI, 1.01–1.53) compared with the Dutch dementia patients. Adjustment for age and sex abolished the difference between Surinamese and the Dutch (HR 1.17; 95% CI, 0.95–1.45), but the difference between Turkish and the Dutch persisted (HR 1.57, 95% CI, 1.08–2.29). The difference between Turkish and the Dutch attenuated and was no longer statistically significant after further adjustment for comorbidities (HR 1.41; 95% CI, 0.96–2.05). The readmission risk after day clinic visit with dementia did not differ between the ethnic groups.

Table 2.

Difference in readmission risk after a first hospitalization or day clinic visit for dementia between ethnic minority groups and Dutch population between 2000 and 2010

| Crude | Age-sex adjusted | Adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Inpatient | |||

| Ethnic Dutch | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Indonesian | 1.00 (0.90–1.12) | 0.99 (0.88–1.11) | 0.97 (0.87–1.07) |

| Surinamese | 1.25 (1.01–1.53) | 1.17 (0.95–1.45) | 1.15 (0.94–1.42) |

| Turkish | 1.85 (1.27–2.69) | 1.57 (1.08–2.29) | 1.41 (0.96–2.05) |

| Antillean | 1.21 (0.73–2.01) | 1.14 (0.69–1.09) | 1.18 (0.71–1.95) |

| Day clinic | |||

| Ethnic Dutch | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Indonesian | 0.95 (0.83–1.07) | 0.95 (0.84–1.08) | 0.95 (0.84–1.08) |

| Surinamese | 0.98 (0.76–1.25) | 0.97 (0.76–1.24) | 0.98 (0.76–1.25) |

| Turkish | 0.74 (0.47–1.17) | 0.70 (0.45–1.10) | 0.70 (0.45–1.10) |

| Antillean | 0.96 (0.58–1.59) | 0.94 (0.57–1.57) | 0.90 (0.54–1.50) |

p-value < 0.05 for bold values

DISCUSSION

Key findings

Our findings show higher re-admission risks in Surinamese and Turkish people as compared to native Dutch population. However, all increased risks were attributed to either differences in demographic factors and/or differences in co-morbidities. Prognosis in terms of long-term mortality was lower only in Surinamese than in the Dutch, but this difference was also accounted for by demographic factors. Mortality risks in the other ethnic minority groups were comparable to the Dutch.

Discussion of key findings

The higher readmission rates after a first dementia hospitalization among Turkish reflect differences in comorbidities. Turkish people had higher prevalence of comorbidities than the Dutch. The difference attenuated and was no longer significant after accounting for comorbidities confirming the potential influence of comorbidities on hospitalization among these groups in our study. Explanations for the higher rate of comorbidities particularly in Turkish dementia patients is unclear, but it is possible that dementia is more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage among this ethnic group compared to other ethnic groups due to cultural factors such as language barriers and negative perception of the dementia within the Turkish community [24, 25]. In a qualitative study among dementia patients in the Netherlands, for example, the family caregivers generally talked openly about the dementia with their close family, but in the Turkish and Moroccan communities, in particular, open communication within the broader communities was often hampered, e.g., by feelings of shame [24].

Literature on ethnic differences in dementia mortality risk following diagnosis remains inconclusive. The lack of ethnic differences in our study corroborates with some [26, 27] but not all previous studies [13, 14, 28]. Yet, studies have been exclusively conducted in the US [15, 16, 28], and the findings may not be applicable to the European context due to differences in ethnic compositions, migration histories, and health care reimbursement system. Intuitively one would link ethnic differences in cardiovascular disease and its risk factors to dementia prognosis among ethnic groups. Indeed, cardiovascular diseases and their risk factors, e.g., hypertension and diabetes have been linked to dementia [29–31]; and these conditions are more common in ethnic minority groups than in the European host populations [32–34]. In our recent analysis, Antillean and Surinamese men had higher incidence of stroke than Dutch people [33].

Hypertension and diabetes are also more common among these populations than in the European host populations [35, 36]. Furthermore, poor blood pressure control had been reported among ethnic minority groups in the Netherlands [36]. Despite the differences in these adverse health outcomes that are known to influence the occurrence and prognosis of dementia [37], prognosis in terms of mortality did not differ between the ethnic minority groups. Also, the known adverse risk profile of ethnic minority groups was not reflected in a higher prevalence of comorbidities, except for the Turkish, probably resulting from the younger ages of the ethnic groups as compared to the Dutch.

Our findings have important clinical and public health implications. Patients with a first hospitalization for dementia have been shown to have poorer mortality risks compared with patients hospitalized for cardiovascular disease such as stroke, heart failure, and acute myocardial infarction in the Netherlands [38]. Our findings show that risk of death and readmission among ethnic minority groups is as high as among the Dutch. This supports the need for targeted advance care planning in the Netherlands particularly in ethnic minority groups where uptake of advance care planning is known to be low or delayed due to cultural barriers such as poor language proficiency and poor health literacy [39].

Limitations and strengths

Our study has limitations. Although we had a very large database, numbers of patients within ethnic subgroups were of modest sample sizes. As a consequence, we were unable to stratify the analysis by dementia subtypes. Due to lack of information on dementia prognosis among ethnic groups prior to this study, we were unable to perform power analyses for the different subgroups. Future studies with a larger sample of ethnic minorities should take these factors into account. Inherent to many national-level databases, we lack data on other factors that may be of relevance such as severity of dementia, limiting our ability to assess the impact of these factors on mortality and readmission rates. Another limitation is that the ethnic minority groups were defined on the basis of country of birth. Country of birth reflect ethnicity reasonably well in some ethnic groups [40], but it may be a less reliable measure of ethnicity for other groups, such as Surinamese who are ethnically diverse. Furthermore, the median follow-up was shorter in Dutch than in ethnic minority groups possibly due to their older age. Nevertheless, we applied Cox regression models, which takes differences in follow-up times between groups into account.

A major strength of this study is that it is based on a nationwide database enabling dementia prognosis to be studied among various ethnic minority groups in Europe as compared to a host population. We are among the first presenting information on dementia mortality and readmission among ethnic minority groups in Europe. The validity of the linkage of different registries in the Netherlands has been demonstrated to be high [19, 21, 41]. Another strength is the high validity of the ICD-9 codes to identify patients with dementia in the Dutch HDR [20].

In conclusion, compared with the Dutch patients, ethnic minority patients with dementia did not have a worse prognosis. The equally high risk of mortality and readmission in all ethnic groups emphasizes the need for targeted advance care planning for prevention and treatment of dementia related complications and comorbidities particularly in ethnic minority groups who are mired by cultural barriers.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This study was financially supported by Alzheimer Nederland (project WE.03-2012-38). Dr Ilonca Vaartjes was supported by a grant from the Dutch Heart Foundation (grant DHF project “Facts and Figures”). Authors’ disclosures available online (http://j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/160897r1).

REFERENCES

- [1].Alzheimer’s Association (2012) Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 8, 131–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Tang MX, Cross P, Andrews H, Jacobs DM, Small S, Bell K, Merchant C, Lantigua R, Costa R, Stern Y, Mayeux R (2001) Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Caucasians in northern Manhattan. Neurology 56, 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Demirovic J, Prineas R, Loewenstein D, Bean J, Duara R, Sevush S, Szapocznik J (2003) Prevalence of dementia in three ethnic groups: The South Florida program on aging and health. Ann Epidemiol 13, 472–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Krishnan LL, Petersen NJ, Snow AL, Cully JA, Schulz PE, Graham DP, Morgan RO, Braun U, Moffett ML, Yu HJ, Kunik ME (2005) Prevalence of dementia among Veterans Affairs medical care system users. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 20, 245–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Heyman A, Fillenbaum G, Prosnitz B, Raiford K, Burchett B, Clark C (1991) Estimated prevalence of dementia among elderly black and white community residents. Arch Neurol 48, 594–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Folstein MF, Bassett SS, Anthony JC, Romanoski AJ, Nestadt GR (1991) Dementia: Case ascertainment in a community survey. J Gerontol 46, M132–M138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Auchus AP (1997) Dementia in urban black outpatients: Initial experience at the Emory satellite clinics. Gerontologist 37, 25–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fillenbaum GG, Heyman A, Huber MS, Woodbury MA, Leiss J, Schmader KE, Bohannon A, Trapp-Moen B (1998) The prevalence and 3-year incidence of dementia in older Black and White community residents. J Clin Epidemiol 51, 587–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yaffe K, Falvey C, Harris TB, Newman A, Satterfield S, Koster A, Ayonayon H, Simonsick E (2013) Health ABC Study. Effect of socioeconomic disparities on incidence of dementia among biracial older adults: Prospective study. BMJ 347, f7051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hendrie HC, Osuntokun BO, Hall KS, Ogunniyi AO, Hui SL, Unverzagt FW, Gureje O, Rodenberg CA, Baiyewu O, Musick BS (1995) Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia in two communities: Nigerian Africans and African Americans. Am J Psychiatry 152, 1485–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hendrie HC, Ogunniyi A, Hall KS, Baiyewu O, Unverzagt FW, Gureje O, Gao S, Evans RM, Ogunseyinde AO, Adeyinka AO, Musick B, Hui SL (2001) Incidence of dementia and Alzheimer disease in 2 communities: Yoruba residing in Ibadan, Nigeria, and African Americans residing in Indianapolis, Indiana. JAMA 285, 739–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hall K, Murrell J, Ogunniyi A, Deeg M, Baiyewu O, Gao S, Gureje O, Dickens J, Evans R, Smith-Gamble V, Unverzagt FW, Shen J, Hendrie H (2006) Cholesterol, APOE genotype, and Alzheimer disease: An epidemiologic study of Nigerian Yoruba. Neurology 66, 223–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mehta KM, Yaffe K, Pérez-Stable EJ, Stewart A, Barnes D, Kurland BF, Miller BL (2008) Race/ethnic differences in AD survival in US Alzheimer’s Disease Centers. Neurology 70, 1163–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gillum RF, Obisesan TO (2011) Differences in mortality associated with dementia in U.S. blacks and whites. J Am Geriatr Soc 59, 1823–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Adelman S, Blanchard M, Rait G, Leavey G, Livingston G (2011) Prevalence of dementia in African-Caribbean compared with UK-born White older people: Two-stage cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry 199, 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Parlevliet JL, Uysal-Bozkir Ö, Goudsmit M, van Campen JP, Kok RM, Ter Riet G, Schmand B, de Rooij SE (2016) Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older non-western immigrants in the Netherlands: A cross-sectional study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 31, 1040–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Glymour MM, Kosheleva A, Wadley VG, Weiss C, Manly JJ (2011) Geographic distribution of dementia mortality: Elevated mortality rates for black and white Americans by place of birth. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 25, 196–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].(1979) The International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death, 9th revision. Clinical Modification Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Harteloh P, de Bruin K, Kardaun J (2010) The reliability of cause-of-death coding in the Netherlands. Eur J Epidemiol 25, 531–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].van de Vorst IE, Vaartjes I, Sinnecker LF, Beks LJ, Bots ML, Koek HL (2015) The validity of national hospital discharge register data on dementia: A comparative analysis using clinical data from a university medical centre. Neth J Med 73, 69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Reitsma JB, Kardaun JW, Gevers E, de Bruin A, van der Wal J, Bonsel GJ (2003) Possibilities for anonymous follow-up studies of patients in Dutch national medical registrations using the municipal population register: A pilot study. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 147, 2286–2290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].van Oeffelen AA, Agyemang C, Stronks K, Bots ML, Vaartjes I (2014) Prognosis after a first hospitalisation for acute myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure by country of birth. Heart 100, 1436–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, Fushimi K, Graham P, Hider P, Januel JM, Sundararajan V (2011) Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol 173, 676–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].van Wezel N, Francke AL, Kayan Acun E, Devillé WL, van Grondelle NJ, Blom MM (2016) Explanatory models and openness about dementia in migrant communities: A qualitative study among female family carers. Dementia (London). doi: 10.1177/1471301216655236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Nielsen TR, Waldemar G (2016) Knowledge and perceptions of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in four ethnic groups in Copenhagen, Denmark. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 31, 222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Waring SC, Doody RS, Pavlik VN, Massman PJ, Chan W (2005) Survival among patients with dementia from a large multi-ethnic population. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 19, 178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Helzner EP, Scarmeas N, Cosentino S, Tang MX, Schupf N, Stern Y (2008) Survival in Alzheimer disease: A multiethnic, population-based study of incident cases. Neurology 71, 1489–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Moschetti K, Cummings PL, Sorvillo F, Kuo T (2012) Burden of Alzheimer’s disease-related mortality in the United States, 1999–2008. J Am Geriatr Soc 60, 1509–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].de la Torre JC (2012) Cardiovascular risk factors promote brain hypoperfusion leading to cognitive decline and dementia. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol 2012, 367516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Vermeer SE, Prins ND, den Heijer T, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM (2003) Silent brain infarcts and the risk of dementia and cognitive decline. N Engl J Med 348, 1215–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Qiu C, Winblad B, Marengoni A, Klarin I, Fastbom J, Fratiglioni L (2006) Heart failure and risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease: A population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med 166, 1003–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Agyemang C, Addo J, Bhopal R, Aikins Ade G, Stronks K (2009) Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and established risk factors among populations of sub-Saharan African descent in Europe: A literature review. Global Health 5, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Agyemang C, van Oeffelen AA, Norredam M, Kappelle LJ, Klijn CJ, Bots ML, Stronks K, Vaartjes I (2014) Ethnic disparities in ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage incidence in the Netherlands. Stroke 45, 3236–3242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].van Oeffelen AA, Agyemang C, Stronks K, Bots ML, Vaartjes I (2014) Incidence of first acute myocardial infarction over time specific for age, sex, and country of birth. Neth J Med 72, 20–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Meeks KA, Freitas-Da-Silva D, Adeyemo A, Beune EJ, Modesti PA, Stronks K, Zafarmand MH, Agyemang C (2016) Disparities in type 2 diabetes prevalence among ethnic minority groups resident in Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intern Emerg Med 11, 327–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Agyemang C, Kieft S, Snijder MB, Beune EJ, van den Born BJ, Brewster LM, Bindraban N, van Montfrans G, Peters RJ, Stronks K (2015) Hypertension control in a large multi-ethnic cohort in Amsterdam, The Netherlands: The HELIUS study. Int J Cardiol 183, 180–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].van de Vorst IE, Koek HL, de Vries R, Bots ML, Reitsma JB, Vaartjes I (2016) Effect of vascular risk factors and diseases on mortality in individuals with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 64, 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].van de Vorst IE, Vaartjes I, Geerlings MI, Bots ML, Koek HL (2015) Prognosis of patients with dementia: Results from a prospective nationwide registry linkage study in the Netherlands. BMJ Open 5, e008897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].van der Steen JT, van Soest-Poortvliet MC, Hallie-Heierman M, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Deliens L, de Boer ME, an den Block L, van Uden N, Hertogh CM, de Vet HC (2014) Factors associated with initiation of advance care planning in dementia: A systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis 40, 743–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Stronks K, Kulu-Glasgow I, Agyemang C (2009) The utility of ‘country of birth’ for the classification of ethnic groups in health research: The Dutch experience. Ethn Health 14, 255–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].De Bruin A, Kardaun JW, Gast A (2004) Record linkage of hospital discharge register with population register: Experiences at Statistics Netherlands. Stat J UN Econ Commun Eur 21, 23–32. [Google Scholar]