Abstract

Previous studies have shown that self-affirmation increases acceptance of a message and motivates health behavior change. The present study investigated whether self-affirmation increases the acceptance of persuasive messages on COVID-19 vaccines and promotes vaccination intention. A total of 144 participants were randomly assigned to the self-affirmation (n = 72) or control (n = 72) groups before reading a persuasive message on COVID-19 vaccines. The results revealed that the self-affirmation group showed significantly higher acceptance of persuasive information on COVID-19 vaccines than the control group. Additionally, the self-affirmation group also showed significantly higher post-experiment vaccination intention than the control group. Mediation analysis indicated that increased acceptance of persuasive information significantly mediated the beneficial effects of self-affirmation on post-experiment vaccination intention. The present study demonstrated that self-affirmation could be an effective strategy for increasing the acceptance of persuasive messages on COVID-19 vaccines and promoting vaccination intention.

Keywords: Self-affirmation, Acceptance of messages, Vaccination intention, COVID-19, Randomized controlled trial

Introduction

With the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) spreading across the world, vaccines are a critical tool for controlling and overcoming the epidemic. Vaccination has also become the most effective measure for people to protect themselves from COVID-19 (WHO, 2021). At present, in addition to the effectiveness and safety of the vaccines, the general public’s acceptance and vaccination rate will directly determine whether the epidemic can be effectively controlled (Sallam, 2021). A recent study estimated that nearly 80% of the population would need to be vaccinated (assuming an effectiveness of 85% against the infection) in order to achieve maximum protection (Hall et al., 2021). However, a considerable number of people are hesitant or refuse to be vaccinated. For example, Ruiz and Bell (2021) found that 37.8% of the people in the United States were hesitant or unwilling to receive COVID-19 vaccines. Similarly, Murphy et al. (2021) reported that in a survey, 31% and 35% of the British and Irish people, respectively, were hesitant or refused to receive the vaccination. A recent study on 1942 French people aged 18–64 found similar results, with 28.8% of the respondents refusing to be vaccinated (Schwarzinger et al., 2021).

Although the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination is generally high in some countries (Sallam, 2021; Wang et al., 2020), studies have shown a downward trend in acceptance levels, as control over the pandemic increases. For example, Wang et al. (2021) revealed that 91.9% of the Chinese people were willing to be vaccinated in March 2020; however, this proportion dropped to 88.6% by the end of the year. Moreover, when asked to assume that the vaccine was available immediately, the proportion of people willing to receive it dropped from 52.2% in March 2020 to 24.7% by the end of the year.

In December 2020, a survey by Ipsos of 4654 people aged 16–74 from 15 countries around the world indicated that there were three main reasons for individuals’ unwillingness to be vaccinated: concerns about the vaccines’ side effects, doubts about its effectiveness, and low-risk perception of COVID-19 (Ipsos, 2020). All these factors are related to a lack of knowledge about the vaccines or the pandemic. Therefore, disseminating information about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines as well as emphasizing the risk of COVID-19 infection to the general public has become an important method of promoting people’s willingness to be vaccinated. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) official website has set up a “Vaccines Explained”1 series to publicize vaccines’ safety and effectiveness as well as their importance for epidemic control.

However, research has shown that once people form an attitude or belief toward a given object or event, they tend to resist acknowledging information that conflicts with their views; it activates their self-defense response (Cohen et al., 2000; Sherman & Cohen, 2002, 2006). Such defense responses may hinder people from accepting persuasive messages with important value and impede health behavior change (Harris & Napper, 2005; Reed & Aspinwall, 1998). For example, smokers are more likely to deny or avoid information about the link between smoking and lung cancer, and continue smoking. Therefore, understanding how to reduce the biased cognition of health messages and promote vaccination has become an imminent question (Lawes-Wickwar et al., 2021).

According to self-affirmation theory, most people are motivated to maintain self-integrity; that is, seeing themselves as “adaptively and morally adequate” (Steele, 1988). This motivation may result in biased and defensive processing of persuasive information because it threatens their self-integrity (Badea & Sherman, 2019; Sherman & Cohen, 2002). However, self-affirmation theory also proposes that the self is a multi-dimensional and flexible system, and thus, threats in one domain can be compensated by affirmations in other, unrelated, important domains. Therefore, self-affirmations that precede the threats can buffer or reduce their impact on self-integrity (Cohen & Sherman, 2014; Sherman, 2013; Sherman & Cohen, 2006), thereby allowing people to process persuasive information in a less defensive manner (Crocker et al., 2008; Harris et al., 2007; Van Koningsbruggen et al., 2009).

Indeed, studies show that receiving self-affirmations before exposure to persuasive information can increase the acceptance of such messages and promote intentions to change health behaviors (Epton et al., 2015; Ferrer & Cohen, 2019; Harris & Epton, 2009). In a pioneering work, Reed and Aspinwall (1998) showed that caffeine users who affirmed their kindness had higher acceptance of caffeine-related health threat information than non-affirmed caffeine users. Similarly, Sherman et al. (2000) showed that sexually active college students who self-affirmed, reported a greater risk perception for HIV and more AIDS-preventive behaviors (e.g., purchased condoms) than their non-affirmed counterparts. Corell et al. (2004) further revealed that self-affirmation not only decreased bias but also increased sensitivity to argument strength. Moreover, Harris et al. (2005, 2007) found that compared with the non-affirmed group, self-affirmed smokers and drinkers showed increased acceptance of health-risk information on smoking and drinking, and a higher willingness to reduce their harmful behaviors. Likewise, Epton and Harris (2008) found that self-affirmation not only increased women’s intention to eat more fruits and vegetables but also promoted their actual fruit and vegetable consumption in the short and long terms. Additionally, Falk et al. (2015) revealed that after self-affirmation, health information activated the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which is associated with self-related information processing, indicating that self-affirmation may facilitate people’s perception of health (threat) information as self-related and thus, more valuable.

The above research shows that self-affirmation can reduce self-defense (Reed & Aspinwall, 1998; Sherman et al., 2000), improve the objectivity of information processing (Corell et al., 2004), and enhance the connection between information and self (Falk et al., 2015), thereby increasing the acceptance of persuasive information and promoting intentions or actual health behavior change. Because Self-affirmation is theorized to restore self-integrity when the self has been threatened (Ferrer & Cohen, 2019; Steele, 1988). Research also shows that self-affirmation is most beneficial for intention/behavior change under the condition of information threatening for message recipients (Harris & Napper, 2005; Reed & Aspinwall, 1998; Sherman et al., 2000). For example, studies showed that self-affirmed frequent caffeine drinkers accepted the information (on the link between caffeine consumption and fibrocystic breast disease) and intended to change their behavior more than low frequent caffeine drinkers (Reed & Aspinwall, 1998; Sherman et al., 2000). Moreover, some studies also revealed the beneficial effects self-affirmation even in the absence of obvious threat (Briñol et al., 2007; Epton & Harris, 2008; Logel et al., 2019). For example, Epton and Harris (2008) showed that self-affirmation before the presentation of a message that outlined the health benefits of fruit and vegetable consumption promoted female graduates and undergraduates’ actual fruit and vegetable consumption.

In 2019, the WHO listed “vaccine hesitation” as one of the top ten threats to global health (Scheres & Kuszewski, 2019). The persistence of the COVID-19 pandemic further amplifies the threat of vaccine hesitation to human health and epidemic control. However, intervention based on information alone may ineffective. This study, therefore, aims to implement self-affirmation theory to the processing of persuasive COVID-19 vaccine information, and examine the effect of self-affirmation on acceptance of persuasive information about COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination intention in a Chinese sample. According to previous studies, we predict that: (1) self-affirmed participants will be more accepting of a COVID-19 persuasive message and will have higher vaccination intention than non-affirmed participants, such effects may be more prominent for those with initially low vaccination intention since the persuasive message would be more threatening for them (Harris & Napper, 2005; Reed & Aspinwall, 1998; Sherman et al., 2000); and (2) increased acceptance of the COVID-19 persuasive message will mediate the beneficial effect of self-affirmation on vaccination intention.

However, most studies regarding self-affirmation and health messaging were conducted on western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic samples, especially from the United States (Cheon et al., 2020; Ferrer & Cohen, 2019). It is widely known that cultural experiences influence and determine an individual’s self. In contrast to the western culture’s emphasis on individualism and tendency to have an independent self-construal, Chinese culture heavily emphasizes collectivism and Chinese people tend to have an interdependent self-construal (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Difference in self-construal presents a set of specific consequences for cognition, motivation, and behavior (Markus & Kitayama, 2003). Thus, it is predicted that the self-affirmation effects in Chinese people may be somewhat different. Nevertheless, emerging evidence show that the impact of self-affirmation on health messaging may be similar among Chinese and western people. For example, Ma and Nan (2019) showed that independent and interdependent self-affirmation did not differ in message derogation and attitudes toward smoking among Chinese people. The present study provides further evidence on the impact of self-affirmation on health messaging in a non-western sample.

Method

Participants

According to G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2007), 128 participants are needed to detect a significant group difference for an analysis of variance (ANOVA) with power 0.8, alpha 0.05, and moderate effect size f = 0.25. Therefore, 144 undergraduates from a compulsory educational psychology course (23 men, 121 women; age: 18–23 years, M = 19.71 ± 1.02) were recruited from April 25 to April 29, 2021. All participants were native Chinese from Northwest Normal University in China and participated in exchange for partial course credit. Participants were assigned to the self-affirmation (n = 72, 7 males, 65 females; age: M = 19.68 ± 0.90 years old) or the control (n = 72, 16 males, 56 females; age: M = 19.74 ± 1.14 years old) group based on a random, computer-generated number for each participant. Prior to the formal experiment, all participants provided informed consent. Additionally, none of the students in the present study received any teaching content or coursework involving self-affirmation, and none of the participants had previously participated in similar studies. There were no dropouts from the self-affirmation and control groups.

Procedure and instruments

The present research took place as part of an educational psychology course in three different classrooms, instructed by a teacher (experimenter). The study included: (1) measurement of baseline vaccination intention; (2) self-affirmation or control manipulation; (3) reading of a popular science article on COVID-19 vaccines; and (4) post-experiment, measurement of acceptance of persuasive vaccine information and vaccination intention. The materials were presented in an A4 physical booklet that was placed in an envelope corresponding to each assigned group. The envelopes were also assigned in a random order based on the computer-generated numbers. In this study, a double-blind setting was used; that is, the participants did not know the assigned condition and the purpose of the study until they completed it. Since participants’ group assignment was carried out by another researcher, the experimenters (teachers) also did not know which participant would be assigned to a specific experimental condition. All materials in the present study were presented in Chinese, and the ethics committee of Northwest Normal University approved the procedure for the present study. At the time the data were collected, two Chinese vaccines (Sinopharm and Sinovac vaccine) were already approved in China and vaccinations were being offered on a voluntary basis.

Baseline Vaccination Intention. Two questions were used to assess baseline COVID-19 vaccination intention: (1) “Do you have any hesitation about getting COVID-19 vaccines?” and (2) “Do you intend to get vaccinated?” Participants indicated their response to the first question on a 9-point scale, ranging from 1 “no hesitation at all” to 9 “very hesitant.” This item was scored in reverse. The second question was answered on a 9-point scale ranging from 1 “definitely do not intend to” to 9 “definitely intend to.” These two items correlated significantly (r = 0.53, p < 0.001) with each other and were combined into a sum score.

Self-affirmation and control manipulation. The experiment manipulation was based on the research of Sherman et al. (2000) and Crocker et al. (2008). All participants were presented with a list of six personal values that were previously identified as important for Chinese individuals: (1) self-discipline and character, (2) ability and talent, (3) public interest, (4) family and kinship, (5) money and wealth, and (6) fame and status (Jin et al., 2009). Participants in the self-affirmation group were asked to select a value that was personally important to them and write about it, while participants in the control group were asked to select a value that was unimportant to them and write why it may be important for other people. Based on Cohen et al. (2006), participants were also asked to indicate their level of agreement with statements concerning their chosen value to reinforce the manipulation after the written task. These statements are: (1) “This value has influenced my/someone’s life”; (2) “In general, I/someone try/tries to live up to this value”; (3) “This value is an important part of who I/someone am/is”; and (4) “I/someone care/cares about this value.” Participants indicated their response to each statement on a scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 6 “strongly agree.”

Popular science articles on COVID-19 vaccines. The article was closely based on two popular science articles on COVID-19 vaccines released by iScientist (2021) and Science_China (2021), which included 2262 Chinese characters in total. This article clarified three common misgivings. First, it addressed the effectiveness of the approved COVID-19 vaccines in China with examples such as, “The third phase trial in Brazil showed that although the overall protective effect of the Sinovac vaccine was 50.4%, its protective effect on severe and hospitalized patients was 100%.” Second, it explained herd immunity, that is, why enough people should be vaccinated to achieve immunity and block the transmission of the virus. Third, it highlighted the risk of infection without vaccination. Participants were asked to read the article carefully.

Acceptance of the message on the COVID-19 vaccine. After reading the article, participants were asked two questions to examine whether they accepted its main points: (1) “Vaccination is very important to protect myself from COVID-19”; and (2) “Mass vaccination is an important measure in building colony-level immune defense.” Participants indicated their responses to each statement on a 9-point scale, ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 9 “strongly agree.” These two items were significantly correlated (r = 0.70, p < 0.001) and were combined into a sum score.

Post-experiment vaccination intention. To avoid practice effects, two different questions were used to assess COVID-19 vaccination intention post-experiment: (1) “To what extent do you think you should be vaccinated?” and (2) “To what extent do you think that you will actually get vaccinated?” Responses were given on a 9-point scale ranging from 1 “definitely do not intend to” to 9 “definitely intend to.” These questions correlated significantly (r = 0.66, p < 0.001) and the sum score was computed as the final score.

Statistical analyses

Data was analyzed following intention to treat analysis (ITT). Firstly, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) or chi-squared test was conducted to compare the sociodemographic and baseline vaccination intention of the different groups. Secondly, between-participants ANOVA was conducted to test the self-affirmation effects on the acceptance of the message and post-experiment vaccination intention. In this step, we also performed supplementary analysis which include covariates (e.g., sex and age) to test the robustness of self-affirmation effects. Thirdly, moderation analyses were conducted with acceptance of the message/post-experiment vaccination intention as dependent variables, condition (dummy coded, control group = 0, self-affirmation group = 1) as an independent variable, baseline vaccination intention as moderator to examine the hypothesis that whether the self-affirmation effect would be more prominent for participants with initial low vaccination intention. Finally, a mediation analysis was conducted with post-experiment vaccination intention as dependent variable, condition (dummy coded, control group = 0, self-affirmation group = 1) as an independent variable, acceptance of the message as mediator, and age and sex as covariates to test whether the acceptance of the persuasive message mediated the effect of self-affirmation on vaccination intention post-experiment.

Results

Baseline comparisons

To test whether the self-affirmation and control groups were matched in age and baseline vaccination intention, a MANOVA was conducted, with age and baseline vaccination intention as dependent variables, and the group as the independent variable. The results showed that the overall group effect was not significant (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.999, F (2, 141) = 0.052, p = 0.949). A separate ANOVA further confirmed that the two groups were comparable in terms of age and baseline vaccination intention (Fs (1,142) < 0.105, ps > 0.462; Table 1). Additionally, a chi-squared test to examine sex distribution across the groups revealed that the proportion of males in the control group was significantly higher than that in the self-affirmation group, χ2(1) = 4.191, p = 0.041; therefore, sex was controlled for in the subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Mean scores and standard deviations on various variables by groups

| Self-affirmation group (n = 72) | Control group (n = 72) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Sex (male/female)a | 7/65 | – | 16/56 | – |

| Age (years) | 19.68 | 0.90 | 19.74 | 1.14 |

| Baseline vaccination intention | 14.11 | 3.75 | 14.12 | 3.72 |

| Acceptance of the message | 16.74 | 1.85 | 15.96 | 1.99 |

| Post-experiment vaccination intention | 16.96 | 2.08 | 16.15 | 2.22 |

N = 144; aThe numbers of males and females reported

Acceptance of the message

To examine whether self-affirmation increases the acceptance of the persuasive message on COVID-19 vaccines, a between-participants ANOVA was conducted with the group (self-affirmation and control) as the independent variable and acceptance of the message as the dependent variable. The results indicated a significant group effect, F (1, 142) = 5.892, p = 0.016, and partial η2 = 0.040, with the self-affirmation group (M = 16.74 ± 1.85) showing significantly higher acceptance of the persuasive message on COVID-19 vaccines, compared with the control group (M = 15.96 ± 1.99). An analysis with sex and age as covariates revealed a similar significant group effect, F (1, 140) = 6.091, p = 0.015, partial η2 = 0.042.

Post-experiment vaccination intention

To examine whether the increased acceptance of the persuasive message on COVID-19 vaccines in the self-affirmation group promotes higher vaccination intention, a between-participants ANOVA was conducted to capture post-experiment vaccination intention. The results revealed a significant group effect, F (1, 142) = 5.055, p = 0.026, and partial η2 = 0.034, with participants in the self-affirmation group (M = 16.96 ± 2.08) showing significantly higher vaccination intention post-experiment than those in the control group (M = 16.15 ± 2.22). An analysis with sex and age as covariates revealed a similar significant group effect, F (1, 140) = 4.507, p = 0.036, and partial η2 = 0.031.

Moderating effect

We used the SPSS macro PROCESS program (Hayes, 2017) to test the possible moderating effect of baseline vaccination intention on the self-affirmation effects in acceptance of the message and post-experiment vaccination intention. The results showed that the moderating effects of baseline vaccination intention in the relationship between condition (dummy coded, control group = 0, self-affirmation group = 1) and acceptance of the message/post-experiment vaccination intention were not significant, p = 0.53/0.74.

Mediating effect

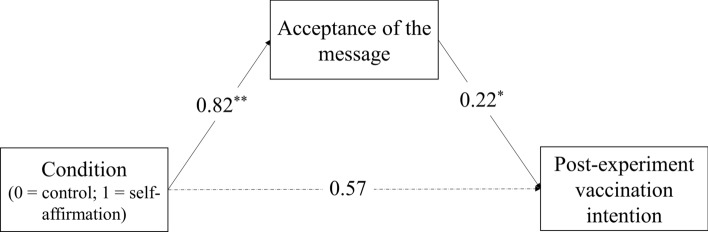

Since the self-affirmation group had higher acceptance of the persuasive message on COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination intention than the control group, we used the SPSS macro PROCESS program (Hayes, 2017) to test whether the acceptance of the persuasive message mediated the effect of self-affirmation on vaccination intention post-experiment. Condition (dummy coded, control group = 0, self-affirmation group = 1) was entered as an independent variable, acceptance of the persuasive message as mediator, and age, sex, and baseline vaccination intention as covariates. The results showed that without the acceptance of the message in the model, condition had a significant effect on vaccination intention post-experiment (B = 0.76, SE = 0.31, p = 0.015). When the acceptance of the message was included as a mediator, the significant effect of condition on post-experiment vaccination intention changed to non-significant (B = 0.57, SE = 0.31, p = 0.065). However, the effect of conditions (e.g., self-affirmation vs. control) on the acceptance of the message was significant (B = 0.82, SE = 0.29, p = 0.006); additionally, the effect of acceptance of the message on post-experiment vaccination intention was significant (B = 0.22, SE = 0.09, p = 0.011). The bootstrapping results revealed that acceptance of the message significantly mediated the relationship between self-affirmation and post-experiment vaccination intention, B = 0.18, SE = 0.10, 95% CI = 0.02 to 0.42 (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mediating effect of acceptance of the message in the relationship between condition and post-experiment vaccination intention. *p < .05, **p < .01

Discussion

At present, many countries have started vaccinating their population, and vaccines have become a critical tool to control the COVID-19 pandemic. All approved vaccines have been strictly tested by conducting large-scale clinical trials with thousands of people to ensure their safety and effectiveness. However, a large number of people worldwide are still hesitant or refuse to be vaccinated (Sallam, 2021). Therefore, in addition to providing sufficient effective vaccines, increasing the general public’s acceptance and improving vaccination intention is vital to curb the spread of COVID-19. The present study is the first to provide evidence that self-affirmation before presenting persuasive information about COVID-19 vaccines increases individuals’ acceptance of the message and promotes vaccination intention.

Previous studies have shown that self-affirmation reduces individuals’ defense response to threat (Harris & Napper, 2005; Sherman & Cohen, 2006) and promotes more systematic and in-depth processing of persuasive information (Correll et al., 2004; Epton & Harris, 2008), and enhances the self-relevance and value of persuasive (threatening) information (Falk et al., 2015). Either of these pathways may increase the acceptance of persuasive messages on COVID-19 vaccines; that is, participants who engage in self-affirmation before being exposed to COVID-19 information would show a higher acceptance of persuasive messages than those who do not engage in self-affirmation; the latter may resist or have a processing bias toward the persuasive messages because fully accepting persuasive information may threaten their self-integrity (Cohen & Sherman, 2014). This threat may arise from the conflict between the persuasive messages (e.g., vaccines are effective) and their existing attitudes and beliefs (e.g., vaccines are ineffective). Alternatively, the threat could also arise from health-risk information in persuasive messages (e.g., not vaccinating will increase the risk of infection for oneself and others). Thus, in the present study, we found that practicing self-affirmation before exposure to persuasive information about COVID-19 vaccines increased individuals’ acceptance of such information.

Will increased acceptance of persuasive messages on COVID-19 after self-affirmation further promote changes in vaccination intention? The results of the present study shows that although those in the self-affirmation and control groups were comparable in terms of their baseline vaccination intention, post-experiment, those who engaged in self-affirmation (i.e., the self-affirmation group) showed significantly higher vaccination intention than those who did not (i.e., the control group). This is consistent with the findings of previous studies (Harris & Napper, 2005; Harris et al., 2007; Reed & Aspinwall, 1998; Van Koningsbruggen et al., 2009). For example, Harris et al. (2005, 2007) found that self-affirmed alcohol drinkers and smokers showed greater message acceptance when processing threatening health risk information. Mediation analysis further confirmed that the increased acceptance of persuasive messages promoted vaccination intention in the self-affirmation group. This implies that increasing individuals’ acceptance of persuasive information will promote a change in behavioral intention.

However, inconsistent with expectations and some previous studies (Harris & Napper, 2005; Reed & Aspinwall, 1998; Sherman et al., 2000), the present study only showed an overall self-affirmation effect but did not confirm the moderating effect of baseline vaccination intention on self-affirmation effect, that is, affirmed individuals with relatively low baseline vaccination intention did not benefit more due to message acceptance and change in vaccination intention. The possible reason may be that the overall relative high scores on baseline vaccination intention for the sample of the present study (M = 14.11 ± 3.53), that is, these people weren't really high hesitant. Considering other studies (e.g., Briñol et al., 2007; Epton & Harris, 2008; Logel et al., 2019), findings of the present study add to the literature in that it shows the beneficial effects of self-affirmation even in the absence of a threat. Moreover, the present study also provides further evidence that self-affirmation influenced health message acceptance and changed behavior intention in a non-western sample.

The findings of the present study have important implications for the improvement of the general public’s acceptance of persuasive messages on COVID-19 and promotion of changes in vaccination intention. The theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) proposes that all determinants work on behavior via intentions. Therefore, improved vaccination intention may further promote actual vaccination behavior.

Some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, because of the convenience sampling strategy, participants in this study were all native Chinese college students. Consistent with a previous study (Wang et al, 2021), since the vaccination intention at baseline level was generally high for this sample, this may hinder the generalizability of the results. Further studies need to examine whether self-affirmation can also benefit people with high vaccine hesitancy. Second, regarding the findings on the acceptance of the persuasive message on COVID-19 vaccines (partial η2 = 0.040) and post-experiment vaccination intention (partial η2 = 0.034), we only obtained a medium to small effect (Cohen, 1988). Therefore, other evidence-based strategies (see Lawes-Wickwar et al., 2021) should be employed in practical applications. Additionally, the final outcome variable of the present study was vaccination intention, not vaccination behavior. Although a large number of studies have demonstrated that intention can highly predict actual behavior (Ajzen et al., 2018; Si et al., 2020), there are also inconsistent findings (Harris & Napper, 2005). According to the trigger and channel framework of self-affirmation effects (Ferrer & Cohen, 2019), the presence of resources (including infrastructure and instrumental content) may help translate motivation and intention into sustained action. Therefore, further resources (e.g., convenient access to vaccines and high-quality services) should be provided to turn the resulting intentional change of self-affirmation into concrete behavior in practical applications. Further research is required to examine the effect of self-affirmation on actual vaccination behavior and how various supporting resources can augment the effects of self-affirmation.

In summary, based on a randomized controlled trial, the present study investigated the effect of self-affirmation on the acceptance of persuasive information on COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination intention. The results show that self-affirmation increases individuals’ acceptance of persuasive information on COVID-19 vaccines, which, in turn, promotes vaccination intention.

Author contributions

SL and QX contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by YX, WZ, and XM. The draft of the manuscript was written by Shifeng Li. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by The Ministry of education of Humanities and Social Science Project-College counselors’ program (Grant Number 20JDSZ3172), and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Gansu Province (18JR3RA082).

Data availability

All data, materials, and code used and generated during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

Human and animal rights and informed consent

Ethical approval was given by the Ethics Committee of Northwest Normal University (20210017). The study was in line with Declaration of Helsinki. And all participants provided informed consent before taking part.

Footnotes

Vaccine Explained Series: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines/explainers.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M, Lohmann S, Albarracín D. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In: Albarracín D, Johnson BT, editors. The handbook of attitudes: Volume 1: Basic principles. Routledge; 2018. pp. 197–255. [Google Scholar]

- Badea C, Sherman DK. Self-affirmation and prejudice reduction: When and why? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2019;28:40–46. doi: 10.1177/0963721418807705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Briñol P, Petty RE, Gallardo I, DeMarree KG. The effect of self-affirmation in nonthreatening persuasion domains: Timing affects the process. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33:1533–1546. doi: 10.1177/0146167207306282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon BK, Melani I, Hong YY. How USA-centric is psychology? An archival study of implicit assumptions of generalizability of findings to human nature based on origins of study samples. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2020;11:928–937. doi: 10.1177/1948550620927269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GL, Aronson J, Steele CM. When beliefs yield to evidence: Reducing biased evaluation by affirming the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:1151–1164. doi: 10.1177/01461672002611011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GL, Garcia J, Apfel N, Master A. Reducing the racial achievement gap: A social-psychological intervention. Science. 2006;313:1307–1310. doi: 10.1126/science.1128317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GL, Sherman DK. The psychology of change: Self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annual Review of Psychology. 2014;65:333–371. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Correll J, Spencer SJ, Zanna MP. An affirmed self and an open mind: Self-affirmation and sensitivity to argument strength. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2004;40:350–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2003.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Niiya Y, Mischkowski D. Why does writing about important values reduce defensiveness? Self-affirmation and the role of positive, other-directed feelings. Psychological Science. 2008;19:740–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epton T, Harris PR. Self-affirmation promotes health behavior change. Health Psychology. 2008;27:746–752. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epton T, Harris PR, Kane R, van Koningsbruggen GM, Sheeran P. The impact of self-affirmation on health-behavior change: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology. 2015;34:187–196. doi: 10.1037/hea0000116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk EB, O’Donnell MB, Cascio CN, Tinney F, Kang Y, Lieberman MD, Taylor SE, An L, Resnicow K, Strecher VJ. Self-affirmation alters the brain’s response to health messages and subsequent behavior change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:1977–1982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500247112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer RA, Cohen GL. Reconceptualizing self-affirmation with the trigger and channel framework: Lessons from the health domain. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2019;23:285–304. doi: 10.1177/1088868318797036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall VJ, Foulkes S, Saei A, Andrews N, Oguti B, Charlett A, Wellington E, Stowe J, Gillson N, Atti A, Islam J. COVID-19 vaccine coverage in health-care workers in England and effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against infection (SIREN): a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. The Lancet. 2021;397:1725–1735. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00790-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PR, Mayle K, Mabbott L, Napper L. Self-affirmation reduces smokers’ defensiveness to graphic on-pack cigarette warning labels. Health Psychology. 2007;26:434–446. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PR, Napper L. Self-affirmation and the biased processing of threatening health-risk information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:1250–1263. doi: 10.1177/0146167205274694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PR, Epton T. The impact of self-affirmation on health cognition, health behaviour and other health-related responses: A narrative review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2009;3:962–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00233.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ipsos. (2020). Global attitudes on a COVID-19 vaccine. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2020-12/global-attitudes-on-a-covid-19-vaccine-december-2020-report.pdf.

- iScientist. (2021). What is the best vaccine? https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/YEt7XH9mNPmx3QURebbBmg.

- Jin SH, Zheng JJ, Xin ZY. The structure and characteristics of contemporary Chinese values. Acta PsyChologica Siniea. 2009;41:1000–1014. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2009.01000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawes-Wickwar S, Ghio D, Tang MY, Keyworth C, Stanescu S, Westbrook J, Jenkinson E, Kassianos AP, Scanlan D, Garnett N, Laidlaw L. A rapid systematic review of public responses to health messages encouraging vaccination against infectious diseases in a pandemic or epidemic. Vaccines. 2021;9:1–26. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logel C, Kathmandu A, Cohen GL. Affirmation prevents long-term weight gain. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2019;81:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2018.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, Nan X. Investigating the interplay of self-construal and independent Vs. interdependent self-affirmation. Journal of Health Communication. 2019;24:293–302. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2019.1601300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review. 1991;98:224–253. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (2003). Models of agency: Sociocultural diversity in the construction of action. In V. Murphy-Berman & J. Berman (Eds.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Vol. 49. Cross-cultural differences in perspectives on self (pp. 1–57). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [PubMed]

- Murphy J, Vallières F, Bentall RP, Shevlin M, McBride O, Hartman TK, McKay R, Bennett K, Mason L, Gibson-Miller J, Levita L, Martinez AP, Stocks TVA, Karatzias T, Hyland P. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nature Communications. 2021;12:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20226-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MB, Aspinwall LG. Self-affirmation reduces biased processing of health-risk information. Motivation and Emotion. 1998;22:99–132. doi: 10.1023/A:1021463221281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz JB, Bell RA. Predictors of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Results of a nationwide survey. Vaccine. 2021;39:1080–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: A concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2021;9:160. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres J, Kuszewski K. The ten threats to global health in 2018 and 2019. A welcome and informative communication of WHO to everybody. Zeszyty Naukowe Ochrony Zdrowia. Zdrowie Publicznei Zarzadzanie. 2019;17:2–8. doi: 10.4467/20842627OZ.19.001.11297. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzinger M, Watson V, Arwidson P, Alla F, Luchini S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative working-age population in France: A survey experiment based on vaccine characteristics. The Lancet Public Health. 2021;6:e210–e221. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00012-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Science_China. (2021). Is vaccination hesitation widespread? https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/z5Jxao0OH3hAj1tSu_Kmjw.

- Sherman DK. Self-affirmation: Understanding the effects. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2013;7:834–845. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DK, Cohen GL. Accepting threatening information: Self-affirmation and the reduction of defensive biases. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2002;11:119–123. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DK, Cohen GL. The psychology of self-defense: Self-affirmation theory. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Academic Press; 2006. pp. 183–242. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DA, Nelson LD, Steele CM. Do messages about health risks threaten the self? Increasing the acceptance of threatening health messages via self-affirmation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:1046–1058. doi: 10.1177/01461672002611003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Si H, Shi JG, Tang D, Wu G, Lan J. Understanding intention and behavior toward sustainable usage of bike sharing by extending the theory of planned behavior. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2020;152:104513. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM. The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Academic Press; 1988. pp. 261–302. [Google Scholar]

- Van Koningsbruggen GM, Das E, Roskos-Ewoldsen DR. How self-affirmation reduces defensive processing of threatening health information: Evidence at the implicit level. Health Psychology. 2009;28:563–568. doi: 10.1037/a0015610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Jing R, Lai X, Zhang H, Lyu Y, Knoll MD, Fang H. Acceptance of covid-19 vaccination during the covid-19 pandemic in China. Vaccines. 2020;8:1–14. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8030482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Lu X, Lai X, Lyu Y, Zhang H, Fenghuang Y, Jing R, Li L, Yu W, Fang H. The changing acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination in different epidemic phases in China: A longitudinal study. Vaccines. 2021;9:1–17. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2021, March 31). Getting the COVID-19 Vaccine. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/getting-the-covid-19-vaccine.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data, materials, and code used and generated during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.