Abstract

Background:

Ticks are vectors of many pathogens that involve various important diseases in humans and animals, they have several diverse hosts consequently can retain a diverse group of indigenous microbes, from bacteria to fungi. Little is known about the prevalence and diversity of tick microflora colonizing the midgut and their effects on ticks and their interaction. This information is important for development of vector control strategies.

Methods:

This study was carried out in northern Iran during autumn 2019. Ticks, Ixodes ricinus caught alive on the bodies of domestic animals in the fall. The tick homogenate was prepared. The identification of fungal isolates was carried out according to a combination of macro and microscopic morphology and molecular sequencing. Pathogenic bacteria of the family Borreliaceae, Francisella tularensis, Borrelia burgdorferi and Coxiella burnetii were tested by real-time PCR.

Results:

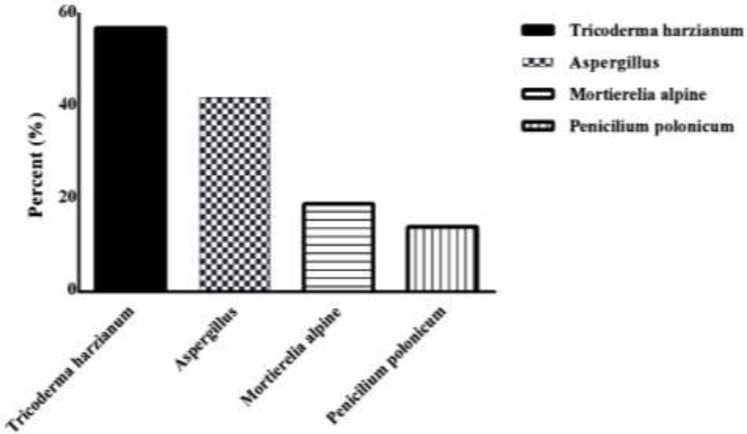

A total of 133 mature I. ricinus ticks were collected from domestic animals, including 71.5% cattle and 28.5% sheep. The tick frequency rates were 87.21% for Mazandaran, 8.28% for Golestan and 4.51% for Gilan Provinces. Total prevalence of fungal tick contamination was 53.4% (75/133) of which Trichoderma harzianum (57%) was the most prevalent species followed by Aspergillus spp. (42%), Mortierella alpine (19%) and Penicillium polonicum (14%). All tick samples were negative for three pathogenic bacteria including Francisella tularensis, Coxiella burnetii, and Borrelia burgdorferi by real-time PCR analysis.

Conclusion:

These results show a first picture of the microbial diversity of ticks and highlight the importance of microbiota and their role in host-pathogen interaction.

Keywords: Microflora, Ixodes ricinus, Fungal species, Mycoflora, Microbiome

Introduction

Arthropods are vectors of many pathogens that involve various important diseases in humans and animals (1). These organisms are hematophagous which feed on blood and most of these arthropods are blood eaters and during engorgement transmit or acquire microorganisms (2) on the other hand, arthropods have several diverse hosts consequently can retain a diverse group of microbes indigenous, from bacteria to fungi (3, 4). A single tick can carry different pathogens, co-infections are common and can make diagnosis and treatment difficult (4). Ixodidae ticks are important in the transmission of a variety of zoonotic microorganisms (viruses, bacteria and protozoan) (5).

Ticks are not only carriers of pathogens, but also a diverse group of commensal and symbiotic microorganisms as bacteria, viruses and fungi are also present in ticks whose biology and their effects on ticks and their interaction remain largely unexplored or very often neglected (6, 7). Tick-borne diseases seem to be a real challenge threatening public and economic health. Some of them can cause physical and cognitive damage which can be very painful (8).

Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne pathogen in the temperate woodlands of North America, Europe and Asia and is caused by some members of Borrelia burgdorferi. The past 20 years the number of reported cases has tripled in the United States and has also increased in parts of Europe (9). The first endemic case of lyme borreliosis was reported in 1997 in Iran proving the existence of the spirochete B. burgdorferi which had not previously been found in ticks in this region (10). In 2001 a 9-year-old boy was admitted to Children's Medical Center with a final diagnosis of Lyme disease (https://acta.tums.ac.ir/index.php/acta/article/view/3187). In 2020, Naddaf et al. reported for the first time the existence of the infection of I. ricinus ticks in the littoral of the Caspian Sea by the spirochetes Lyme borreliosis (11).

The tularemia caused by Francisella tularensis, zoonosis, is characterized by high morbidity and mortality rates in more than 190 different mammal species, including humans (12). In Iran, positive serological tests were first reported in 1973, in wildlife and domestic livestock in the northwestern and southeastern parts of the country. The first human case was reported in 1980 in the southwest of Iran, and recent studies conducted among at-risk populations in the western, southeastern, and southwestern parts of Iran. The presence of F. tularensis in ticks was confirmed in the province of Kurdistan (western Iran) and the possible role of ticks in the transmission of the pathogen to livestock and humans by bites has been demonstrated in this region (13).

Q fever is a zoonosis with a worldwide distribution is caused by Coxiella burnetii, many species of mammals, birds, and ticks are reservoirs of C. burnetii in nature. Coxiella burnetii infection is most often latent in animals (14). According to a study published in 2019 in the case of infective endocarditis (IE) patients hospitalized in Rajai Cardiovascular Medical and Research Center from August 2015 to September 2017, a high prevalence of Q fever was revealed (15). Coxiella burnetii DNA or its antibodies have frequently been detected in ruminants. Since these animals can transmit the infection to humans, Q fever can be a potential health problem in Iran (16).

Anaplasmosis is a zoonotic disease, described in various domestic animals and humans and the bacterium in question is Anaplasma phagcytophilum transmitted by ticks with a worldwide distribution (17). In Iran, in 2014 in the province of Mazandaran, we have the first investigation of tick-borne Anaplasma infections in domestic animals and humans (18). Fungal microbiota comprises an important part of total microbiota of vertebrates and non-vertebrates (19). The determination of the tick fungal microflora (microbiota) and the interactions between its symbiotic microorganisms in the context of pathogen transmission will likely reveal new perspectives and spawn new paradigms for tick-borne diseases (20). The present study for the first time aimed to determine the diversity of the fungal microflora that colonize in the middle intestine of mature I. ricinus ticks in the three provinces of northern Iran.

Materials and Methods

Study area and population

This study was conducted in northern Iran consists of the southern border of the Caspian Sea and the Alborz mountains with an area of 58,167Km2 in three provinces of Gilan (37.280 N, 49.59° E) Mazandaran (36.2262° N, 52.5319° E) and Golestan (37.2898° N, 55.1376° E). The forest cover of northern Iran has a total of 3,400,000 hectares of forest on the northern slopes of the Alborz Mountains and the coastal provinces of the Caspian Sea (Fig. 1). General characteristics of the climate are too much rain in all seasons, especially in autumn and winter, relatively high humidity in all seasons and low temperature difference during the day due to the presence of moisture. Domestic animals such as cattle, sheep, and dog due to the large number of forests, can easily move between the forest and the herd.

Fig. 1.

Map of tick sampling areas in three northern provinces of Iran

Sampling

Sampling of ticks on domestic animals (cattle, sheep) was carried out in autumn 2019 (from 6 to 11 November) during the period of multiplication of ticks and was carried out at various sites in the provinces of northern Iran including Mazandaran, Gilan and Golestan (Table 1), (Fig. 1). The sample size was estimated at 100 ticks but given the number of ticks collected at this time of the year to increase the accuracy of the study, all 133 ticks collected were entered in this study and collected according to their animal host in 14 sampling sites (Table 1).

Table 1.

Details of location and host of fungal species (Trichoderma harzianum, Mortierella alpine, Aspergillus sp., Penicillium polonicum) were found in Ixodes ricinus from the northern provinces of Iran, 2019

| Province | City | Distract | N | E | Host | No. of sampled ticks (contaminated ticks) | Fungal spp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mazandaran | Mahmoud-abad | Boondeh | 36°34′16.0″ | 52°14′16.0″ | Cattle | 7 (5) | T. harzianum |

| Mazandaran | Chamestan | Joorband | 36°26′42.2″ | 52°07′37.9″ | Cattle | 6 | NF |

| Mazandaran | Chamestan | Joorband | 36°26′45.2″ | 52°07′26.4″ | Sheep | 2 | NF |

| Mazandaran | Chamestan | Joorband | 36°26′39.2″ | 52°07′32.1″ | Cattle | 6 | NF |

| Mazandaran | Amol | Razageh | 36°19′50.0″ | 52°21′42.0″ | Sheep | 6 | NF |

| Mazandaran | Amol | Esku Mahalleh |

36°24′19.7″ | 52°18′30.8″ | Cattle | 7 | NF |

| Mazandaran | Chamestan | Joorband | 36°26′15.5″ | 52°07′15.3″ | Cattle | 14 | |

| (6) | T. harzianum | ||||||

| (14) | M. alpine | ||||||

| Mazandaran | Amol | Komdarreh | 36°23′55.2″ | 52°25′51.7″ | Cattle | 20 | NF |

| Mazandaran | Savadkuh | Chay Baq | 36°20′30.4″ | 52°52′05.9″ | Sheep | 11 | |

| (9) | T. harzianum, | ||||||

| (5) | Aspergillus sp. | ||||||

| Mazandaran | Tonekabon | Goli Jan | 36°49′04.1″ | 50°48′45.8″ | Cattle | 16 | |

| (10) | Aspergillus sp., | ||||||

| (5) | P. polonicum | ||||||

| Mazandaran | Nowshahr | Musa Abad | 36°37′40.2″ | 51°30′39.0″ | Sheep | 11 | |

| (10) | T. harzianum, | ||||||

| (8) | Aspergillus sp. | ||||||

| Mazandaran | Fereydunkenar | Boneh | 36°39′24.0″ | 52°30′22.3″ | Cattle | 10 | |

| Kenar | (9) | T. harzianum, | |||||

| (8) | Aspergillus sp. | ||||||

| Golestan | Kordkuy | Valaghuz | 36°45′59.2″ | 54°07′10.2″ | Cattle | 11 | NF |

| Gilan | Rudsar | Ahmad | 37°10′13.5″ | 50°16′57.3″ | Cattle | 6 | |

| Abad | (4) | T. harzianum | |||||

| (5) | P. polonicum |

NF: Not Found

Ticks caught alive on the bodies of domestic animals living in barn using forceps and sterile disposable material, were then collected according to their host. The ectoparasites were identified directly under a stereomicroscope without mounting. All ectoparasites have been identified at the species level using available taxonomic morphological key of ticks (21). Ticks identified as mature I. ricinus were kept for this study. A number of 133 I. ricinus ticks were isolated from two domestic animals, cattle and sheep from a total of 14 sampling sites (Table 1).

Preparation of ticks' homogenate

The whole ticks were placed in sterile tubes containing 70% ethyl alcohol for 3min then rinsed with sterile water three times to avoid transportation of microorganisms from the outside environment and from the surface of the ticks. Homogenization of the samples (ticks) is done with a QIAGEN Tissue Lyser II homogenization device, the samples were placed in sterile microtubes containing metal willow and 300μl of RTL RNA buffer extraction kits (QIAGEN) were added to the microbial tubes. According to the manufacturer's instructions, the QIAGEN Tissue Lyser II microtubes were homogenized at 30 Hertz (HZ) for 3min to obtain a uniform suspension. The topical solution was removed and transferred to a new sterile microtube to continue the extraction process. One part was used fresh for fungus culture and the rest for DNA extraction and the molecular process.

Mycological Identification Culture based identification

Ticks' homogenate was diluted with Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) to give a final volume of 100μl and diluted solutions these were spread on to Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (Peptone 1%, Glucose 2%, Agar-agar 1.5%; Merck, Germany) and Potato Dextrose Agar (Potato infusion 20%, Dextrose 2%, Agar 2%) plates and incubated for 2 weeks at 25 °C. The plates were periodically checked for fungal colonies. Identification of fungal isolates was performed according to a combination of macro and microscopic morphology.

Molecular identification DNA extraction

DNA was extracted and purified from fungal colonies using the following method, briefly, 10–20mm3 of the fresh colonies grown on Sabouraud glucose agar (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) were added to 1.5ml tubes that contained 300μl of lysis buffer (200M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 25mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA); 0.5% w/v sodium dodecyl sulfate; and 250mM NaCl) and crushed with a conical grinder (Micro Multi Mixer; IEDA Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) for 1min. The samples were incubated in a boiling water bath for 10min, mixed with 150μl of 3.0M sodium acetate, kept at −20 °C for 10min, and centrifuged at 12,000rpm for 10min. The supernatant was extracted once with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and once more with chloroform. The DNA in supernatant was precipitated with 250μl isopropanol, washed with 300μl of 70% ethanol, air dried, and rehydrated in 50μl ultrapure water, and stored at −20 °C until use.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and Sequencing

For the polymerase chain reaction with the specific ITS region primers, ITS1 and ITS4 (Table 2). Each mixture contained 2.5μl of 10× reaction buffer, 0.5μM of universal fungal primers forward ITS1 and reverse ITS4, 400μM of deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1.25U of Taq DNA polymerase (Takara, Japan), 1μl of DNA extracted and enough ultrapure water to reach a final reaction volume of 25μl. The PCRs were programmed for preheating at 96 °C for 6min followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C for 1min, 56 °C for 1min, and 72 °C for 45s, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 10min. Five microliters of the PCR products were electrophoresed on to 1.5% agarose gel in Tris-Acetate-EDTA (TAE) buffer (Tris 40mM, acetic acid 20mM, EDTA 1mM), stained with 0.5μg/ml of ethidium bromide, and observed and photographed under ultraviolet irradiation. The PCR products of the ITS region were purified using a QI quick purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), sequenced in both directions using the same primers.

Table 2.

Primers and probes used for molecular detection of three pathogens Francisella tularensis, Coxiella burnetii, Borrelia burgdorferi and fungal species

| Target (gene) | Primer/probe | Sequence (5′ → 3′) | Product (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISFtu2 (F. tularensis) | ISFtu2Fw | ACAAGAAGTCATGCTTGATTCAAC | 144 |

| ISFtu2Rv | GGATTACCTAAAGCATCAGTCATAGC | ||

| Probe | FAM-ATAGCAAGAGCACATGCTTGTGCTACGG-TAMRA | ||

| 16S rRNA (Borrelia) | 6BOR16SFw | GGTCAAGACTGACGCTGAGTCA | 135 |

| 6BOR16SRv | GGCGGCCACTTAACACGTTAG | ||

| Probe | FAM-TCTACGCTGTAAACGATGCACACTTGGTG –BHQ-1 | ||

| IS1111 (C. burnetii) | tmQ-koorts4-Fw | AAAACGGATAAAAAGAGTCTGTGGTT | 70 |

| tmQ-koorts4-Rv | CCACACAAGCGCGATTCAT | ||

| tmQ-koorts4-probe | FAM-AAAGCACTCATTGAGCGCCGCG-TAMRA | ||

| Fungal ITS | ITS1 | TCCGTAGGTGAACTGCGG | 600–750 |

| ITS4 | TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGGC |

Molecular detection of bacterial pathogens

The whole genomic DNA extracted from ticks were screened for members of the family Borreliaceae, F. tularensis and C. burnetii by targeting 16SrRNA, ISFTu2 and IS1111 genes respectively, using primers and probes listed in Table 2. The final 20μl reactions contained 10μl master mix 2× (Amplicon, Denmark), 500 nM of each primer, 200nM probe, and 4μl (50 nM) of the template DNA. Amplifications were performed in a Rotor-Gene 6000 instrument (Corbett Life Science, Sydney, Australia) for an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10min, followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15sec, and annealing at 60 °C for 60sec. DNA of B. borgdorferi senso stricto (Amplirun® Borrelia DNA control), the DNA of F. tularensis subsp holarctica NCTC 10857 and plasmid contain IS1111 from C. burnetii were included as positive controls in all the assays. PCR with no sample DNA was considered as negative control.

Results

Ticks collected

A total of 133 mature I. ricinus ticks were collected from domestic animals including 71.5 % cattle and 28.5% sheep. The tick frequency was 87.21% for Mazandaran, 8.28% for Golestan and 4.51% for Gilan (Table 1), (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The frequency (left panel) and prevalence (right panel) of fungal contamination of the Ixodes ricinus ticks collected in three Northern provinces in Iran, 2019

Detection of fungal species

The isolated extract of tick midgut was cultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar (E-Merck, Germany) medium to isolate the possible fungal species. The morphological and then molecular identification have proven the fungal species include 57% Trichoderma harzianum (MT804339, MT803548, MT809136), 42% Aspergillus spp., 14% Penicillium polonicum (MT809131) and 19% Mortierella alpine (MT803487). Among the 14 sampling sites, ticks from seven sites were contaminated with fungal species from four distinct genera (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Distribution of fungal genera and species in contaminated Ixodes ricinus ticks in Northern provinces of Iran, 2019

Detection of Bacterial pathogens

Real-time PCR for three bacterial pathogens including F. tularensis, C. burnetii, B. burgdorferi was negative for all 133 ticks obtained from 14 sampling sites (Table 1).

Discussion

To our knowledge this project was the first attempt to determine the fungal community that inhabits the middle intestine of ticks in the three provinces of northern Iran and contamination with three bacterial pathogens that transmitted to human by ticks, using culture and molecular methods.

Ixodes ricinus ticks cover a wide geographic region in the EU (22), I. ricinus is an indigenous hard tick species having a wide geographical distribution (23), Portugal to Russia and from North Africa to Scandinavia. This wide geographical distribution entails that this tick species could have a role in transmission of tick-borne disease in wide geographic areas (24). A survey of ticks was carried out in four different geographic areas of Iran, where the majority of domestic ruminants in Iran exist (18, 19) showed Ixodidae ticks were found throughout the year. The highest number of adult Ixodidae ticks was generally found from April to August, and Ixodes ticks were present in the Caspian region and in the south and west of country (24–27).

The number of ticks obtained is very important in Mazandaran which agrees with the previous studies on the abundance of this tick according to favorable climatic conditions in the Northern provinces of Iran (28, 29).

Ixodes ricinus is a three-host tick: larvae, nymphs and adults feed on different hosts where larvae and nymphs prefer small to medium-sized animals and adults tend to feed on large animals (30). In this study we have chosen adult ticks because of their size, it is especially the adult females fed or in the process of being engorged with blood which are the most detectable, because they are much larger than during the other stages of development and the amount of blood they eat on large animals such as cattle and sheep.

We were expecting to have a much more varied number of fungi species. As this study is the first done by this approach, we have not the element of comparison but in a study carried out on the midgut of sand flies they found six fungi species of which two fungi species are common with our study (Penicillium and Aspergillus) (31). Another most observed species in this study was Actinomycetes that is a shared bacterial species with fungi and among 14 sample sites in 83.4%, this species of bacteria was present.

The fungal species isolated in this study are among the saprophytes which can be pathogenic in insects, plants and humans (32). Studies have shown that fungi can have an entomopathogenic effect under different environmental conditions (33). The predominant pathogenic genera isolated from soil in the United States for winter tick larvae (Dermacentor albipictus) being Aspergillus spp, Beauveria bassiana, Mortierella spp, Mucor spp, Paecilomyces spp, Penicillium spp. and Trichoderma spp. (34). On I. ricinus ticks, the most important tick species in Europe, susceptibility to entomopathogenic fungi shows particularly high potential efficacy and the predominant species of isolated entomopathogenic fungi were hyphomycetes, Paecilomyces farinosus and Verticillium lecanii, Beauveria bassiana, B. brongniartii, P. fumosoroseus and V. aranearum (35). The secondary metabolites of fungi may be involved in their entomopathogenic effect, Aspergillus flavus is effective on insect Heliozella stenella by secreting aflatoxin, caused histological changes in even at very low doses. Metarhizium anisopliae secretes Distruxine (a) Distruxine (b) when injected into wax and silk moth. Beauvaria bassiana (White muscurdine fungus) secret Beauvaricine is the peptide depsi (36). The susceptibility to entomopathogenic fungi against two of the most important tick species in Europe: I. ricinus and Dermacentor reticulatus shows the potential efficacy particularly greater in I. ricinus (37). The definition of the tick's microbiome and interactions between the tick and its symbiotic bacteria in the context of pathogen transmission likely reveal new knowledge for controlling tick-borne diseases (38). In this study we have tried to answer this question even though it is very early because in the studies already show microbiome of I. ricinus ticks evaluated over the last 10 years in Austria reveals a number of bacteria were affiliated with the genera Rickettsia, Bartonella and Borrelia (39) which are known to be pathogenic and transmitted by ticks indicating that the tick microbiome is mainly composed of gram-negative bacteria of the phylum Proteobacteria and intracellular bacterial endosymbionts which regulate the reproductive capacity and vectoral competence of ticks, also maintain the integrity of the epithelial barrier of the tick gut (6). Although I. ricinus is of great importance to public health, its microbial communities remain largely unexplored to this day.

A pool of adults of I. ricinus collected from two distinct geographic regions of northern Italy showed a total of 108 genera belonging to all bacterial phyla and pathogenic bacteria, such as Borrelia, Rickettsia and Candidatus neoehrlichia (40). The microbiome currently focuses mainly on its eubacterial members, but the microbiome is also made up of viruses and eukaryotic microbes such as protozoa, nematodes, and fungi, and their interactions within and between realms could further modulate the human health (41). On the other hand, ecological analysis revealed that the composition of bacterial communities depending on the geographic regions and the life stages of the ticks. This finding suggests that the environmental context (abiotic and biotic factors) and host selection behaviors affect their microbiome (40).

Entomopathogenic fungi are known to infect different tick species and their effectiveness is very strain specific. Numerous studies show the important role of pathogenic fungi in the control of insects, including Ixodes (35, 37, 42–44). Although entomopathogenic fungi have been widely used for agricultural and forestry pest control, little effort has been made to assess the applicability of the biological control potentials of entomopathogenic fungi against ticks, vectors of human and animal diseases. it can also be said that the susceptibility of ticks to a particular fungus depends largely on the genera and species of ticks; species of fungus, strain, concentration of conidia;, temperature, humidity and geographical area always trying to understand the biology of the fungus, which is necessary to better understand its proper use in field conditions (40). In the case of Fusarium stem rot caused by Fusarium graminearum strongly affecting the productivity of corn crops by modifying the plant microbiome by promoting the colonization of roots by Trichoderma harzianum in the corn rhizosphere, first, we increase plant growth and further protect the environment from harmful agrochemical effects by replacing it with a biological control agent (45).

Conclusion

Results of the present study revealed that different human and animal pathogenic fungal genera are among microbial flora of I. ricinus ticks in Northern provinces of Iran. These results represent only a first image of the microbial diversity of the tick. Further studies are needed to determine the roles these genera play in ticks and their effects on human health. These studies could bring us closer to the discovery of the causative agent and interaction between them to know the system of transmission of these agents even save them by ticks.

Acknowledgments

Authors wish to thank the personal of Mycology department of the Pasteur Institute of Iran for their kind help in culturing tick samples.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical considerations

There was no human and animal study that needs ethical concerns.

References

- 1.Irwin PJ, Jefferies R. (2004) Arthropod-transmitted diseases of companion animals in Southeast Asia. Trends Parasitol. 20(1): 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krenn HW, Aspöck H. (2012) Form, function and evolution of the mouthparts of blood-feeding Arthropoda. Arthropod Struct Dev. 41(2): 101–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abraham NM, Liu L, Jutras BL, Yadav AK, Narasimhan S, Gopalakrishnan V, Ansari JM, Jefferson KK, Cava F, Jacobs-Wagner C, Fikrig E. (2017) Pathogen-mediated manipulation of arthropod microbiota to promote infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 114(5): E781–E90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonnet SI, Binetruy F, Hernández-Jarguín AM, Duron O. (2017) The tick microbiome: why non-pathogenic microorganisms matter in tick biology and pathogen transmission. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 7: 236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonenshine DE. (2018) Range expansion of tick disease vectors in North America: implications for spread of tick-borne disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 15 (3): 478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choubdar N, Karimian F, Koosha M, Oshaghi MA. (2021) An integrated overview of the bacterial flora composition of Hyalomma anatolicum, the main vector of CCHF. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 15(6): e0009480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisen RJ, Kugeler KJ, Eisen L, Beard CB, Paddock CD. (2017) Tick-borne zoonoses in the United States: persistent and emerging threats to human health. ILAR J. 58(3): 319–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah SZ, Jabbar B, Ahmed N, Rehman A, Nasir H, Nadeem S, Jabbar I, Rahman ZU, Azam S. (2018) Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of a tick-borne disease-Kyasanur forest disease: current status and future directions. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 8: 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kilpatrick AM, Dobson AD, Levi T, Salkeld DJ, Swei A, Ginsberg HS, Kjemtrup A, Padgett KA, Jensen PM, Fish D, Ogden NH, Diuk-Wasser MA. (2017) Lyme disease ecology in a changing world: consensus, uncertainty and critical gaps for improving control. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 372(1722): 20160117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shams-Davatchi C. (1997) The first endemic case of lyme brocellosis in Iran. Med J Islamic Republ Iran. 11(3): 237. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naddaf SR, Mahmoudi A, Ghasemi A, Rohani M, Mohammadi A, Ziapour SP, Nemati AH, Mostafavi E. (2020) Infection of hard ticks in the Caspian Sea littoral of Iran with Lyme borreliosis and relapsing fever borreliae. Ticks Tick-borne Dis. 11(6): 101500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zellner B, Huntley JF. (2019) Ticks and Tularemia: Do We Know What We Don't Know? Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 9: 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahravani M, Moravedji M, Mostafavi E, Baseri N, Seyfi H, Mohammadi M, Ziaei AH, Mozoun MM, Latifian M, Esmaeili S. (2022) Molecular detection of Francisella tularensis in small ruminants and their ticks in western Iran, Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 83: 101779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkan Ş, Erbaş G, Parin U. (2017) Bacterial Tick-Borne Diseases of Livestock Animals. Chapter 7, In: Livestock Sciences (Sekin S. Eds.), InTech Open, Rijeka, Croatia, pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moradnejad P, Esmaeili S, Maleki M, Sadeghpour A, Kamali M, Rohani M, Ghasemi A, Bagheri Amiri F, Pasha HR, Boudagh S, Bakhshandeh H, Naderi N, Ghadrdoost B, Lotfian S, Dehghan Manshadi SA, Mostafavi E. (2019) Q fever endocarditis in Iran. Sci Rep. 9(1): 15276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nokhodian Z, Feizi A, Ataei B, Hoseini SG, Mostafavi E. (2017) Epidemiology of Q fever in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis for estimating serological and molecular prevalence. J Res Med Sci. 22: 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khatat SEH, Sahibi H. (2015) Anaplasma phagocytophilum: An emerging but un-recognized tick-borne pathogen. Rev Mar Sci Agron Vét. 3(2): 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hosseini-Vasoukolaei N, Oshaghi MA, Shayan P, Vatandoost H, Babamahmoudi F, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Telmadarraiy Z, Mohtarami F. (2014) Anaplasma Infection in Ticks, Livestock and Human in Ghaemshahr, Mazandaran Province, Iran. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 8(2): 204–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martino C, Dilmore AH, Burcham ZM, Metcalf JL, Jeste D, Knight R. (2022) Microbiota succession throughout life from the cradle to the grave. Nat Rev Microbiol. 20: 707–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clube J. (2018) Altering microbial populations and modifying microbiota. Google Patents.

- 21.Mathison BA, Pritt BS. (2014) Laboratory identification of arthropod ectoparasites. Clin Microbiol Rev. 27(1): 48–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Švec P, Hönig V, Zubriková D, Wittmann M, Pfister K, Grubhoffer L. (2019) The use of multi-criteria evaluation for the selection of study plots for monitoring of I. ricinus ticks–Example from Central Europe. Ticks Tick-borne Dis. 10(4): 905–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rehman A, Nijhof AM, Sauter-Louis C, Schauer B, Staubach C, Conraths FJ. (2017) Distribution of ticks infesting ruminants and risk factors associated with high tick prevalence in livestock farms in the semi-arid and arid agro-ecological zones of Pakistan. Parasit Vectors. 10(1): 190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mansfield KL, Jizhou L, Phipps LP, Johnson N. (2017) Emerging tick-borne viruses in the twenty-first century. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 7: 298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahbari S, Nabian S, Shayan P. (2007) Primary report on distribution of tick fauna in Iran. Parasitol Res. 101(Suppl 2): S175–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yakhchali M, Hosseine A. (2006) Prevalence and ectoparasites fauna of sheep and goats flocks in Urmia suburb, Iran. Veterinarski Arhiv. 76(5): 431–442. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sofizadeh A, Telmadarraiy Z, Rahnama A, Gorganli-Davaji A, Hosseini-Chegeni A. (2014) Hard tick species of livestock and their bioecology in Golestan Province, north of Iran. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 8 (1): 108–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hosseini-Chegani A, Tavakoli M, Telmadarraiy Z. (2019) The updated list of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae and Argasidae) occurring in Iran with a key to the identification of species. Syst Appl Acarol. 24(11): 2133–2166. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yakhchali M, Rostami A, Esmaelzadeh M. (2011) Diversity and seasonal distribution of ixodid ticks in the natural habitat of domestic ruminants in north and south of Iran. Revue Méd Vét. 162(5): 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson JF, Magnarelli LA. (2008) Biology of ticks. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 22(2): 195–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akhoundi M, Bakhtiari R, Guillard T, Baghaei A, Tolouei R, Sereno D, Toubas D, Depaquit J, Abyaneh MR. (2012) Diversity of the bacterial and fungal microflora from the midgut and cuticle of phlebotomine sand flies collected in North-Western Iran. PloS One. 7(11): e50259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mygind PH, Fischer RL, Schnorr KM, Hansen MT, Sönksen CP, Ludvigsen S, Raventós D, Buskov S, Christensen B, De Maria L, Taboureau O, Yaver D, Elvig-Jørgensen SG, Sørensen MV, Christensen BE, Kjaerulff S, Frimodt-Moller N, Lehrer RI, Zasloff M, Kristensen HH. (2005) Plectasin is a peptide antibiotic with therapeutic potential from a saprophytic fungus. Nature. 437(7061): 975–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeo H, Pell JK, Alderson PG, Clark SJ, Pye BJ. (2003) Laboratory evaluation of temperature effects on the germination and growth of entomopathogenic fungi and on their pathogenicity to two aphid species. Pest Manag Sci. 59(2): 156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoder JA, Dobrotka CJ, Fisher KA, LeBarge AP, Pekins PJ, McLellan S. (2018) Entomopathogenic fungi of the winter tick in moose wallows: a possible bio-control for adult moose? ALCES. 54: 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalsbeek V, Frandsen F, Steenberg T. (1995) Entomopathogenic fungi associated with Ixodes ricinus ticks. Exp Appl Acarol. 19 (1): 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rao GUB, Narladkar BW. (2018) Role of entomopathogenic fungi in tick control: A review. J Entomol Zoolog Stud. 6(1): 1265–1269. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szczepańska A, Kiewra D, Plewa-Tutaj K, Dyczko D, Guz-Regner K. (2020) Sensitivity of Ixodes ricinus (L.,1758) and Dermacentor reticulatus (Fabr.,1794) ticks to entomopathogenic fungi isolates: preliminary study. Parasitol Res. 119(11): 3857–3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Institute of Medicine (2011) Critical Needs and Gaps in Understanding Prevention, Amelioration, and Resolution of Lyme and Other Tick-Borne Diseases: The Short-Term and Long-Term Outcomes: Workshop Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Available at: 10.17226/13134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guizzo MG, Dolezelikova K, Neupane S, Frantova H, Hrbatova A, Pafco B, Fiorotti J, Kopacek P, Zurek L. (2022) Characterization and manipulation of the bacterial community in the midgut of Ixodes ricinus. Parasit Vectors. 15: 248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carpi G, Cagnacci F, Wittekindt NE, Zhao F, Qi J, Tomsho LP, Drautz DI, Rizzoli A, Schuster SC. (2011) Metagenomic profile of the bacterial communities associated with Ixodes ricinus ticks. Plos One. 6(10): e25604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goodrich JK, Di Rienzi SC, Poole AC, Koren O, Walters WA, Caporaso JG, Knight R, Ley RE. (2014) Conducting a microbiome study. Cell. 158(2): 250–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hartelt K, Wurst E, Collatz J, Zimmermann G, Kleespies RG, Oehme RM, Kimmig P, Steidle JLM, Mackenstedt U. (2008) Biological control of the tick Ixodes ricinus with entomopathogenic fungi and nematodes: Preliminary results from laboratory experiments. Int J Med Microbiol. 298: 314–320. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wassermann M, Selzer P, Steidle JL, Mackenstedt U. (2016) Biological control of Ixodes ricinus larvae and nymphs with Metarhizium anisopliae blastospores. Ticks tick-borne Dis. 7(5): 768–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhioua E, Ginsberg HS, Humber RA, LeBrun RA. (1999) Preliminary survey for entomopathogenic fungi associated with Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) in southern New York and New England, USA. J Med Entomol. 36(5): 635–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saravanakumar K, Li Y, Yu C, Wang Q, Wang M, Sun J, Gao JX, Chen J. (2017) Effect of Trichoderma harzianum on maize rhizosphere microbiome and biocontrol of Fusarium Stalk rot. Sci Rep. 7(1): 1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]