Summary

Health impacts of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) and SARS-CoV-2 co-infections are not fully understood. Both pathogens modulate host responses and induce immunopathology with extensive lung damage. With a quarter of the world’s population harboring latent TB, exploring the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 infection and its effect on the transition of Mtb from latent to active form is paramount to control this pathogen. The effects of active Mtb infection on establishment and severity of COVID-19 are also unknown, despite the ability of TB to orchestrate profound long-lasting immunopathologies in the lungs. Absence of mechanistic studies and co-infection models hinder the development of effective interventions to reduce the health impacts of SARS-CoV-2 and Mtb co-infection. Here, we highlight dysregulated immune responses induced by SARS-CoV-2 and Mtb, their potential interplay, and implications for co-infection in the lungs. As both pathogens master immunomodulation, we discuss relevant converging and diverging immune-related pathways underlying SARS-CoV-2 and Mtb co-infections.

Subject areas: Virology, Microbiology, Bacteriology

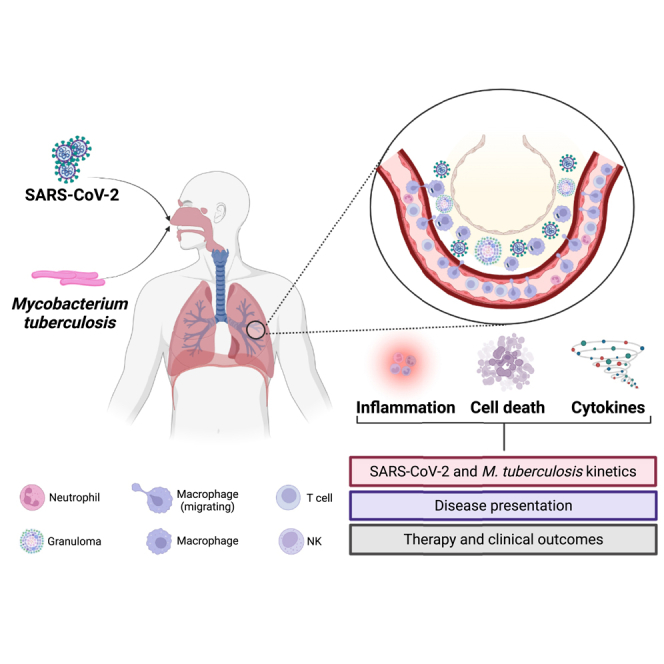

Graphical abstract

Virology; Microbiology; Bacteriology

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB), is an ancient pathogen that has plagued humans for thousands of years and is responsible for ∼1.5 million deaths annually.1 In addition, about 25% of the world’s population carries Mtb in a latent form that has the potential to transition into active TB, for example due to co-infections. TB is the leading cause of death in people living with HIV worldwide, and people with HIV have up to 20 times higher risk of developing active TB compared to those without HIV. While reactivation of latent TB by HIV has been well studied,2,3 the impact of respiratory pathogens on latent TB is less understood.4,5,6

COVID-19, caused by SARS-CoV-2, is a severe respiratory viral disease that emerged in December 2019 to cause a global pandemic.7 The spread of COVID-19 had a severe impact on TB control efforts due to reduced access to diagnostics and treatment options.8 The global TB report from WHO estimates an 18% reduction in TB case notifications and 15%–20% reduction in patients receiving TB treatment. The under-diagnosis of TB can be attributed to reduced access to reagents and services due to pandemic-related restrictions and also to the stigma associated with visiting health-care clinics, as both TB and COVID-19 manifest with similar symptoms.1 As countries recover from the effects of the pandemic, we need to increase efforts to improve case detection and narrow the gap between incident TB cases and diagnosis of new TB cases. Consequently in 2021, the number of new TB cases and deaths increased, reversing the progress made in TB control over the past decade.1,8 Both Mtb and SARS-CoV-2 infect the lung and cause a broad spectrum of respiratory symptoms, along with the global occurrence of both diseases. Thus, there is a significant risk of co-infection and crosstalk between these pathogens.9

Recent in vitro and clinical studies suggest that SARS-CoV-2 infection may contribute to the progression of TB from a latent to active state through depletion of host CD4+ T cells, inflammatory responses in the lung, or activation of stem-cell-mediated defense mechanisms.10,11 While these reports highlight the negative effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on TB resolution,10,11 experiments in mice suggest that prior Mtb infection is protective against SARS-CoV-2-mediated disease.12 These reports allude to potential crosstalk between both pathogens, although mechanistic studies are yet to clarify these interactions. Protective effects of Mtb infection against viral infections have been considered before in the context of BCG (Bacillus Calmette-Guerin) vaccination and immunity against non-TB stimuli.13 These effects have been reported against viruses such as yellow fever virus14 and viral respiratory tract infections15 in healthy volunteers and elderly individuals, respectively. The role of the BCG vaccine and non-specific-trained immunity in protecting against COVID-19 has been investigated and has been inconclusive with several conflicting reports summarized recently.16 In this article, we specifically focus on Mtb and SARS-CoV-2 co-infections and its potential implications on pathogenesis and host cellular responses. We emphasize on interconnected events during infection such as cell death, inflammation, and cytokine responses as they play prominent roles in pathogen control and clinical outcomes.

Prevalence of TB and COVID-19 co-infections

Multiple case reports of Mtb and SARS-CoV-2 co-infection have been published and have helped uncover a link between these pathogens in clinical settings.8,17,18 Surveillance data show that co-infection neared 1% in the Philippines,17 5% in South Africa,8 and between 0.37% and 4.47% in China.18 Meta-analysis studies suggest that co-infection is associated with higher rates of mortality from COVID-19 alone. A recent multinational study reported a mortality of 11% in TB/COVID-19-positive patients,19 doubling the maximum mortality estimated by Johns Hopkins for COVID-19 alone.20 Reports from South Africa also indicate that co-infected individuals have a 2x mortality risk compared to patients with Mtb mono-infection,21,22 although participants in these studies often had comorbidities such as diabetes and HIV.23,24,25 These studies indicate that co-infections elevate the risk of negative clinical resolutions in affected individuals. However, mechanistic studies investigating protein-protein interactions during Mtb and SARS-CoV-2 co-infections and their influence on the host immune response and clinical outcomes have not been addressed.

SARS-CoV-2 infection-induced pathology within the lung

SARS-CoV-2 infection of lung epithelial cells initiates cell death and imbalanced immune responses that accompany the release of infectious virus.26,27,28 SARS-CoV-2 proteins have been implicated in the induction of programmed cell death like apoptosis29 as well as non-programmed necroptosis30 and pyroptosis.31 For instance, ORF3a activates caspase-3 which then directs the ordered break down of the infected cell into self-contained compartments during apoptosis.29 Macrophages that clear apoptotic bodies can become activated upon recognition of SARS-CoV-2 antigens carried as apoptosis cargo, directly contributing to inflammation.32 Necroptosis, an inflammatory cell death pathway, is characterized by the phosphorylation cascade of receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 3, and mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase (MLKL). Phosphorylated MLKL assembles pores through which damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPS) and pro-inflammatory mediators are secreted from the dying cell.33 SARS-CoV-2 RNA polymerase, nsp12 interacts with RIPK1, resulting in direct activation of necroptosis and cytokine release during in vitro infection.30 Pyroptosis is another cell death mechanism where inflammasome complexes (NLRP3-ASC-Caspase1) drive pore formation by Gasdermin and subsequent release of inflammasome-derived cytokines.34 Cell-to-cell fusion and syncytia formation during SARS-CoV-2 infection are associated with pyroptosis in the lung-derived cell line A549 in vitro.31,35 Fragments of the spike (S) protein produced during syncytia formation, i.e., S2, are involved in activation of caspase-9 that ultimately leads to pyroptosis.31 Indeed, SARS-CoV-2 infection mediates cell death through the release of DAMPS and inflammatory signals, such as IL-1β that amplifies lung injury.36 Cell death and release of inflammatory cytokines contribute to lung tissue damage in severely ill patients as demonstrated in postmortem human lung samples.36

Secretion of DAMPS and pro-inflammatory molecules recruit inflammatory cells that compound the immunopathology of severe COVID-19 (Figure 1). Macrophages are significant players among recruited immune cells due to their role in sensing DAMPS, communicating with incoming immune cells, and translating signals into self-sustained pro-inflammatory programs.37 Cytokine release and hyperinflammation syndromes have been observed during COVID-19, where mediators such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-18, CXCL-10, MIP, and TNF-α trigger exaggerated inflammation.38 Monocytes and B cells upregulate expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine gene transcripts when co-cultured with SARS-CoV-2-infected lung epithelial cells.39 Furthermore, NK cells release enzymes like perforin,40 whereas neutrophils produce reactive oxygen species41 that injure the airways and delay tissue repair in severely ill patients with COVID-19. Thus, communication dynamics between infected lung tissue and immune cells is central to the onset of inflammation during COVID-19.

Figure 1.

SARS-CoV-2 and M. tuberculosis infection within the lung microenvironment

SARS-CoV-2 infection induces cell death in lung epithelial cells (A). SARS-CoV-2 infection induces the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemoattractants (B), which increases the influx of immune cells within the lung microenvironment (C). Infiltrated immune cells produce excessive pro-inflammatory mediators like TNF-α and IL-1, and antiviral type I IFN (D). M. tuberculosis (Mtb) can infect epithelial cells and macrophages within the lung environment (E). Mtb-infected macrophages secrete a subset of cytokines (F) that recruits immune cells and macrophages which communicate via IL-12 and IFNγ (G) to mount anti-Mtb responses (H). Mtb exploits the influx of macrophages to acquire new hosts, and in turn, amplify cytokine production (F and G). TB infections are characterized by formation of structured cellular aggregates called granulomas (I) where both pro- and anti-inflammatory responses co-exist and influence bacterial dynamics (J). While cytokine responses that are induced during monotypic infections are being studied, little is known about the combinatorial impact of SARS-CoV-2- and Mtb-mediated induction of cytokine responses on host tissue health and the respective pathogens (K and L). Figure created with BioRender.com.

In addition to promoting inflammation, studies have demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection can induce a broad spectrum of type I interferon (IFN) responses in patients42,43 (Figure 1). SARS-CoV-2 is sensitive to the antiviral effects of IFNs, but encodes several accessory proteins to antagonize them, giving rise to the varied IFN expression patterns observed in patients.44 IFN production depends on a phosphorylation cascade that includes TBK1 and culminates in nuclear translocation of phosphorylated IRF3, which activates transcription of IFN.45 Nsp13 and nsp6 proteins of SARS-CoV-2 inhibit phosphorylation of TBK1 and IRF3,46 respectively, and nsp12 and Orf 6 block nuclear translocation of IRF3 by binding to Nup98 in the nuclear pore complex, thus inhibiting synthesis of type I IFN.47 If IFN is produced, nsp1, nsp6, nps13, Orf 3a, Orf 7b, and M block phosphorylation of downstream transcription factors, STAT1 and STAT2, and inhibit expression of interferon-stimulated genes in recipient cells.46 SARS-CoV-2 therefore modulates the IFN response via cooperative mechanisms48 which warrants a closer inspection considering that IFNs can influence TB progression.49,50

SARS-CoV-2 can also infect immune cells, albeit non-productively. CD4+ T cells are infected by SARS-CoV-2 in an angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)-independent and LFA1-dependent manner. CD4+ infection induces T cell activation, exhaustion, and eventual cell death via the ROS-HIF-1a pathway, which might explain the lymphopenia observed in some patients with COVID-19.51 Depletion of CD4+ T cells may be linked to defective anti-TB responses,10,11 and therefore, SARS-CoV-2 infection of these immune cells may be detrimental for TB control. This effect evokes that of HIV in the global decline of CD4+ T cells,52 which has been linked to enhanced risk of TB acquisition and failure in disease control.53

M. tuberculosis infection of the lung

Mtb can establish persistent infection in the lung, where bacteria modulate antimicrobial and pro-inflammatory responses.54 Mtb infection in humans and in animal models have revealed the multi-stage and essential role of both pro- and anti-inflammatory responses in establishing infection. Production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, and type I IFN accompanies intracellular bacterial replication and drives the formation of organized cellular structures called granulomas (Figure 1). Th1 responses mediated by CD4+ T cells, which secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, recruit macrophages and activate cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. Anti-inflammatory responses mediated through cytokines, such as IL-10, IL-27, TGF-β, and Th17 and regulatory T cells, are important for controlling Mtb infection and associated lung pathology.55,56,57 The pathology and progression of Mtb lesions is determined by various immune players—cytokines, chemokines (CCR2, CXCR2, and CXCR5), lipid effectors, and immune cells (macrophages, NK cells, neutrophils, DCs, B cells, CD4+, CD8+, and γδ T cells). Indeed, these factors together influence the balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory responses during Mtb infection in the lung and contribute to establishing microenvironments where Mtb can persist and establish active/latent infection or is cleared by the host.54 The role of host immune responses in keeping Mtb in check is highlighted by the increased risk of TB reactivation observed upon pharmacologic inhibition of TNF-α or in HIV-infected individuals.2,58

Like SARS-CoV-2 infection, cytokine release during Mtb infection is associated with inflammasome activation and cell death. Type I IFN responses promote Mtb infection, and transcriptomic analyses of Mtb-infected cells/tissues have shown that production of type I IFNs can be used as a marker of active TB.49 Mtb not only elicits complex immune responses but it also counters them to persist within host cells. Mtb thrives within intracellular compartments whose function is to destroy invading microorganisms. Modulation of intracellular compartments and trafficking, and cell membrane repair turn the cell into an environment suitable for Mtb replication.59 Like SARS-CoV-2, Mtb interferes with the innate immune response and directs cell death pathways that modify the lung structure.60

Mtb can induce non-inflammatory (apoptosis) and inflammatory (necroptosis) cell death in macrophages, with each cell death mode evoking a different disease outcome. The balance, or lack thereof, between apoptosis and necroptosis has garnered the spotlight in recent years as Mtb modulates both responses, leading to varied outcomes.61,62,63 Apoptosis is thought to inhibit mycobacterial dissemination by restricting this pathogen to apoptotic bodies and enhancing antigen presentation to clear infection, preserving respiratory tissue.63,64 It is thus surprising that Mtb has developed pro-apoptotic factors like the secreted mycobacterial proteins EsxA65 and LpqH66 that invoke apoptosis through phagosome membrane damage and toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) in THP-1 macrophages, respectively. Macrophages infected with Mtb can also undergo apoptosis via activation of caspases-3 and -12 following endoplasmic reticulum stress,67 highlighting the presence of multiple pro-apoptosis mechanisms. Rather surprisingly, virulent Mtb has also been shown to subvert apoptosis through intramacrophage secretion of mycobacterial proteins like NuoG that suppresses nitric oxide production, apoptosis, and release of TNF-α, facilitating Mtb survival, immune evasion, and spread.61

The apparent contradiction between pro and anti-apoptosis mechanisms may reflect temporal regulation of this cell death mode. This phenomenon may also occur during non-programmed cell death like necroptosis and pyroptosis, which do not preserve respiratory architecture. Mtb can direct activation of necroptosis via its tuberculosis necrotizing enzyme and depletion of NAD+ in macrophages in vitro.68 Virulent Mtb also upregulates necroptosis pathway components, including MLKL, via uncharacterized mechanisms and poises cell death toward necroptosis.69 As a form of regulated necrosis, it is possible that Mtb exploits necroptosis to build a replication-favorable microenvironment, as virulent Mtb replicates well within necrotic macrophages.70 Indeed, the roles of apoptosis and necroptosis in mycobacterial replication and spread may appear contradictory at times and are likely influenced by differences in strain and infection models used to dissect them. Nevertheless, the balance between necroptosis and apoptosis could be at the heart of the variability in TB clinical presentation.69

Cell membrane damage or rupture of the lysosomal compartments within macrophages infected with Mtb induces the NLRP3-ASC-Caspase1 pyroptosis cell death pathway.71 Pyroptosis can be countered by Mtb itself by preventing inflammasome activation through the Mtb protein PknF that limits K+ efflux.72 The implications of pyroptosis and “contra-pyroptosis” and how the balance between these modes is achieved are unknown. The capacity of Mtb to modulate cell death in macrophages highlights the multitude of factors involved in the establishment of the microenvironment in which Mtb persists. The release of cytokines and chemokines as byproduct of cell death is also significant for modification of the lung environment by fomenting hyperinflammation.69

Crosstalk during SARS-CoV-2 and Mtb co-infection

While studies have identified cytokines produced upon infection with SARS-CoV-2 or Mtb, limited data exist on their crosstalk during co-infection and their cumulative impact on disease outcome in humans.73 In addition, studies have presented contradictory results on Mtb and SARS-CoV-2 co-infections, including conflicting reports on the role of BCG vaccination-mediated protection against COVID-19.16 Both respiratory diseases share similar hyperinflammatory signatures composed of major pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1 (Figure 1). Secreted cytokines and chemokines recruit immune cells that amplify pro-inflammatory responses and tissue damage. Robust, yet delayed type I IFN response has been linked to hyperinflammation in some COVID-19 patient cohorts.74 Mtb infection induces type I IFNs, which acts like a double-edged sword in both limiting and facilitating Mtb infection under different circumstances.75 Indeed, the complex pathogen-IFN interplay, the tug-of-war between the pathogen’s immunomodulatory activity and immune response, and its impact on SARS-CoV-2 and Mtb co-infections remain unknown (Figure 1).

Meta-analysis of transcriptomic signatures and data from single-cell RNA-sequencing studies in individuals across the TB infection spectrum identified higher COVID-19 risk signatures in active patients with TB and in individuals who progressed from latent to active TB, compared to non-progressors or uninfected individuals.73 Infection of monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) in vitro with Mtb was also found to induce expression of ACE2 (cellular receptor of SARS-CoV-2) and the proviral host protease, TMPRSS2. Furthermore, exposure of MDMs to conditioned media from Mtb-infected MDMs promoted SARS-CoV-2 infection and expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines.73 These observations are consistent with clinical reports that suggest that patients with TB have specific responses that raise the risk of developing severe COVID-19.76

A recent study by Mejia et al. demonstrated that ACE2 transgenic mice infected with Mtb are resistant to acute disease caused by subsequent SARS-CoV-2 infection.12 In this study, responses typically associated with Mtb, such as upregulation of IFNγ and expansion of lymphocytes and mononuclear cells were observed, suggesting that host response was primarily directed toward Mtb rather than the invading SARS-CoV-2.12 Hildebrand and colleagues77 also found that persistent TB (over 8 weeks infection) reduced the viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in lungs and spleens of ACE2 transgenic mice. In addition, this study suggested that SARS-CoV-2 affects TB kinetics; Mtb dissemination to spleen and liver was marginally enhanced in transgenic mice harboring persistent TB.77 Overall, these studies suggest that, at a minimum, both pathogens influence kinetics and host responses against each other, albeit in a rodent model. If we presume that a “primed” immune response exists in humans with active TB, like what was observed by Mejia et al. in mice, then the question remains - why do co-infected patients experience higher mortality in some cases?

Examining the link between cell death modes and inflammation is necessary to understand the mechanism of disease and clinical outcomes during co-infections (Figure 2). Virulent Mtb benefits from inflammatory cell death to facilitate its dissemination, resulting in collateral release of a gradient of inflammatory molecules as a by-product of necroptosis.61 SARS-CoV-2 triggers both apoptosis and necroptosis, but whether it can distort the balance between these cell death modes is unknown (Figure 2). While coronavirus infection-mediated bias toward necroptosis might help TB spread or reactivation, apoptosis might temper dissemination of virulent Mtb. On the contrary, could TB-linked necroptosis make the lung environment inhospitable for SARS-CoV-2? Experimental evidence is needed to shed light on the relationship between cell death modes, inflammation, and clinical presentation during co-infections.

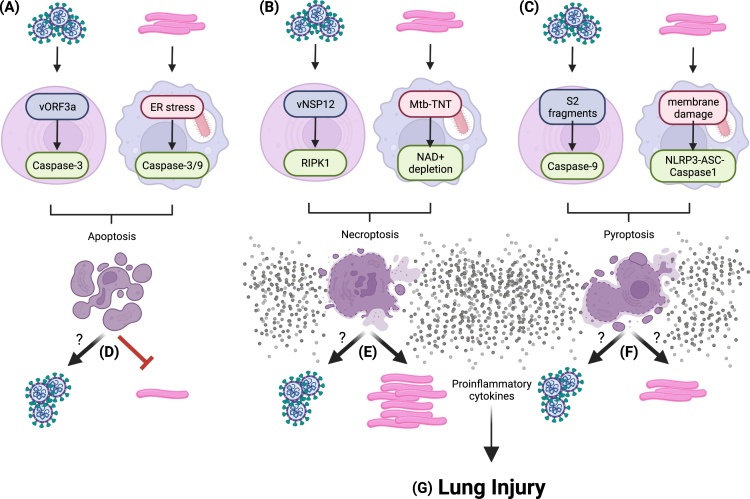

Figure 2.

Non-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory cell death in SARS-CoV-2 and M. tuberculosis infection

SARS-CoV-2 viral and M. tuberculosis (Mtb) promote non-inflammatory apoptosis (A), pro-inflammatory necroptosis (B), and pyroptosis (C) modes of cell death through viral and bacterial proteins and cell membrane damage. The combinatorial effects of cell death modes on SARS-CoV-2 and Mtb dynamics are not well understood. Whether apoptosis influences SARS-CoV-2 is still an open question, although it likely restricts Mtb replication and spread (D). Mtb exploits necroptotic cells to enhance its replication, but the necroptotic microenvironment may not be suitable for SARS-CoV-2 (E). The impact of pyroptosis on both pathogens, if any, has not been defined, albeit both pathogens can elicit pyroptosis in respiratory tissue (F). Nevertheless, the ensuing cytokine release as by-product of pro-inflammatory cell death contributes to lung injury (G). Figure created with BioRender.com.

Macrophages phagocytose dying cells without executing inflammatory programs in a mechanism known as efferocytosis. Macrophages that phagocytose apoptotic cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 become unable to clear respiratory infected cells or their remaining debris.32 Impaired efferocytosis and subsequent accumulation of debris in the lungs is associated with acute respiratory disease syndrome,78 which is a major contributor of severe COVID-19.79 Despite their efferocytosis incompetency, SARS-CoV-2-activated macrophages display enhanced production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6.32 The role of Mtb-infected macrophages in clearing SARS-CoV-2-infected cells and subsequent impact on the inflammatory phenotype of these macrophages is unknown. Discovering the role of host-microbe and microbe-microbe interactions using co-infection models of SARS-CoV-2 and Mtb is critical to delineate the nuances of molecular pathogenesis and host response modulation.

Accumulating data suggest that therapeutics targeting pro-inflammatory cytokines or their receptors may improve COVID-19 outcome. Therefore, interferons, corticosteroids, and monoclonal antibodies against inflammatory cytokines have been used as immunomodulators to control the inflammation and disease symptoms associated with COVID-19. While these therapeutics may control acute immunopathology, they may also suppress responses required to eliminate persisting virus and modulate the dynamics of Mtb populations (Figure 3). For example, corticosteroids have been used for the treatment of severely ill patients with COVID-19, which resulted in decreased mortality.80,81 However, prolonged use of corticosteroids in Mtb-infected individuals is associated with a higher risk of developing TB.82,83 Similarly, anti-IL6 antibodies could influence Mtb replication as Mtb regulates IL-6 secretion to inhibit type I interferon signaling and promote infection.84 It is unknown whether acute COVID-19, therapeutics against COVID-19 hyperinflammatory syndromes, long COVID, or a combination of these can impact TB progression and outcome. Multiple reports now suggest that the use of dexamethasone to treat COVID-19 symptoms may have helped in reactivation and dissemination of TB.85,86 The impact of TB therapeutics on SARS-CoV-2 infection and immunopathology has not been reported (Figure 3). Detailed studies are needed to address whether and how treatment against COVID-19 impacts TB progression and vice versa. Indeed, understanding the molecular drivers of protective and damaging host responses during co-infection will inform the development of drugs and treatment regimens (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Therapeutic intervention strategies for SARS-CoV-2 and M. tuberculosis

Both SARS-CoV-2 and M. tuberculosis (Mtb) infections induce the expression of type I IFNs and pro-inflammatory mediators. However, cytokine identity and levels during co-infection remain less studied. Indeed, the crosstalk between infection-induced cytokines, and its impact on SARS-CoV-2 infection, active TB, and latent TB remain less known. Multiple antiviral compounds have shown promising efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 (A). Similarly, effective antibiotics exist for both active and latent forms of Mtb infection (B). Clinical trials for immune modulators, cytokine blockers, and anti-inflammatory compounds have shown promise in mitigating infection-induced immunopathology, but the collective effect of these drugs on lung tissue homeostasis, pathogen control, and infection resolution during co-infection remains unknown (C). Figure created with BioRender.com.

Comorbidities that contribute to the risk of developing both severe COVID-19 and active TB remain to be identified. Any potential relationship between long COVID and latent TB is worth investigating given the possibility of long-term persistence and the spectrum of structural and cytokine changes induced by these pathogens. One-quarter of the world’s population harbor latent Mtb, and the molecular and long-term impacts of COVID-19 in these individuals are still unidentified.

Impact of BCG vaccination and trained immunity on SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis

BCG vaccine constitutes attenuated strains derived from Mycobacterium bovis and have been used widely to limit TB in children.87,88 BCG vaccination has been shown to enhance response against yellow fever virus14 and probable viral respiratory tract infections15 in BCG-vaccinated healthy volunteers and elderly individuals, respectively. Antiviral effects have also been reported in mice infected with influenza A89 and herpes simplex virus 2,90 indicating that BCG vaccination confers non-specific antiviral protection in vaccinated subjects.

The protective effects from BCG vaccination are attributed to “trained innate immunity”, a phenomenon that involves non-specific and short-lived enhanced responsiveness against pathogens other than Mtb. BCG vaccination enhances IFNγ and pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in monocytes exposed to non-TB pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus and even heat-killed bacteria.13 Training of the innate immunity occurs through epigenetic changes in myeloid progenitors within the bone marrow via histone modification (e.g., H3K4me3 or trimethylation of histone 3) which expose transcription start sites of immune genes.91 “Trained” monocytes expand and persist for short periods, sustaining non-specific immune activation and subsequent protective effects against non-TB stimuli.91 This response involves the receptor nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-2 (Nod2)13 which recognizes both bacterial components like muramyl dipeptide92 and viral RNA.93 The flexibility of Nod2 to recognize bacterial and viral DAMPS may bridge some of the cross-protective responses against viruses following BCG vaccination.

The role of BCG vaccination in preventing COVID-19 is controversial. Epidemiological analysis in countries with national BCG vaccination programs suggested a protective effect against COVID-19 morbidity and mortality during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.94,95,96 Data from South American countries with long running national BCG vaccination programs demonstrated that protection against SARS-CoV-2 was marginal at best.97 For example, in Peru, where nationwide BCG vaccinations began in the 1960s and coverage remains above 80% in children under 1 year of age,98 deaths due to COVID-19 became one of the highest in the world with 655.37 deaths per 100,000 population at its peak.20 More studies are required to assess the duration of non-specific immunity post BCG vaccination.

A recent study showed that BCG vaccination protected mice from influenza A virus infection, but no protection was observed in SARS-CoV-2-infected mice.99 In a separate study, BCG-vaccinated ACE2 transgenic mice failed to demonstrate any protective effects against SARS-CoV-2.77 BCG vaccination also failed to prevent COVID-19 in at-risk health-care workers in a double-blind clinical trial in South Africa.100 A definitive role and mechanism of BCG vaccination-mediated protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection remains to be identified.

Significance of studying respiratory co-infections

While Mtb and SARS-CoV-2 have unique features, both pathogens thrive in the lungs and can elicit similar hyperinflammatory syndromes, immune dysregulation, and extensive lung damage.101,102,103 Highly pathogenic betacoronaviruses, such as Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, also infect the lungs and may encounter previously established Mtb infection. Coronavirus infection dynamics, mechanisms of disease, immune response dysregulation, and clinical outcomes in the background of Mtb-induced lung damage have not been addressed. The opposite is also true: the effects of these emerging respiratory viruses on Mtb reactivation, latent TB, or anti-TB therapy have not been explored. Furthermore, the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 and common non-TB bacterial pneumonias (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, etc.) in hospital settings is unknown.

Lung-specific comorbidities like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis, and asthma, and their influence on viral pneumonias and vice versa remain under-studied. For instance, patients who recover from TB after anti-TB treatment often suffer from sequelae like COPD104 that may influence susceptibility to and aggravate respiratory infections105 as reports from South Africa suggest.106 An international committee has been established which generated a consensus statement emphasizing the need for a better understanding of the epidemiology and immunology of respiratory viral infections and their interactions with TB, with implications for better diagnosis, treatment, and prevention.105 Like Mtb, these conditions are chronic, modify the lung environment, and may present complications due to extensive damage of the lung architecture. Whether these local progressive conditions are conducive to severe viral pneumonias like COVID-19 or if they make the tissue microenvironment hostile to virus spread are still unknown. Comorbidities likely impact immune regulatory networks, compound clinical outcomes, and influence therapy during co-infections. Dissecting SARS-CoV-2 and Mtb co-infections using experimental in vitro and in vivo models that recapitulate the lung environment is necessary to resolve the ongoing debate on how these pathogens influence one another, the host response, and their clinical outcomes. Evaluating these co-infections is essential to develop therapies against novel emerging respiratory viruses and to refresh our outlook on old foes like TB.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation (SHRF) and Lung SK grant awarded to A.B. and N.D. K.R.C. is supported by a Living Skies Postdoctoral fellowship awarded by the University of Saskatchewan. A.B. also acknowledges support from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), and Coronavirus Variants Rapid Response Network (CoVaRR-Net). VIDO receives operational funding for its CL3 facility (Inter-Vac) from the Canada Foundation for Innovation through the Major Science Initiatives. VIDO also receives operational funding from the Government of Saskatchewan through Innovation Saskatchewan and the Ministry of Agriculture.

Author contributions

K.R.C. wrote the first draft with inputs from N.D. and A.B. All authors edited the manuscript during revisions and approved the final version.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Neeraj Dhar, Email: neeraj.dhar@usask.ca.

Arinjay Banerjee, Email: arinjay.banerjee@usask.ca.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Annual Global TB Report of WHO; 2022. Annual Report of Tuberculosis. 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diedrich C.R., Flynn J.L. HIV-1/Mycobacterium tuberculosis coinfection immunology: how does HIV-1 exacerbate tuberculosis? Infect. Immun. 2011;79:1407–1417. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01126-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esmail H., Riou C., Bruyn E.d., Lai R.P.-J., Harley Y.X.R., Meintjes G., Wilkinson K.A., Wilkinson R.J. The immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in HIV-1-Coinfected persons. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2018;36:603–638. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walaza S., Cohen C., Tempia S., Moyes J., Nguweneza A., Madhi S.A., McMorrow M., Cohen A.L. Influenza and tuberculosis co-infection: a systematic review. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses. 2020;14:77–91. doi: 10.1111/irv.12670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mhimbira F., Hiza H., Mbuba E., Hella J., Kamwela L., Sasamalo M., Ticlla M., Said K., Mhalu G., Chiryamkubi M., et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of respiratory viruses and bacteria detected in tuberculosis patients compared to household contact controls in Tanzania: a cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infection. 2019;25:107–107.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Zalm M.M., Walters E., Claassen M., Palmer M., Seddon J.A., Demers A.M., Shaw M.L., McCollum E.D., van Zyl G.U., Hesseling A.C. High burden of viral respiratory co-infections in a cohort of children with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020;20:924. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05653-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., Zhao X., Huang B., Shi W., Lu R., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dheda K., Perumal T., Moultrie H., Perumal R., Esmail A., Scott A.J., Udwadia Z., Chang K.C., Peter J., Pooran A., et al. The intersecting pandemics of tuberculosis and COVID-19: population-level and patient-level impact, clinical presentation, and corrective interventions. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022;10:603–622. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00092-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tadolini M., Codecasa L.R., García-García J.M., Blanc F.X., Borisov S., Alffenaar J.W., Andréjak C., Bachez P., Bart P.A., Belilovski E., et al. Active tuberculosis, sequelae and COVID-19 co-infection: first cohort of 49 cases. Eur. Respir. J. 2020;56:2001398. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01398-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riou C., du Bruyn E., Stek C., Daroowala R., Goliath R.T., Abrahams F., Said-Hartley Q., Allwood B.W., Hsiao N.-Y., Wilkinson K.A., et al. Relationship of SARS-CoV-2–specific CD4 response to COVID-19 severity and impact of HIV-1 and tuberculosis coinfection. J. Clin. Invest. 2021;131:e149125. doi: 10.1172/JCI149125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pathak L., Gayan S., Pal B., Talukdar J., Bhuyan S., Sandhya S., Yeger H., Baishya D., Das B. Coronavirus activates an altruistic stem cell–mediated defense mechanism that reactivates dormant tuberculosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2021;191:1255–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2021.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosas Mejia O., Gloag E.S., Li J., Ruane-Foster M., Claeys T.A., Farkas D., Wang S.-H., Farkas L., Xin G., Robinson R.T. Mice infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis are resistant to acute disease caused by secondary infection with SARS-CoV-2. PLoS Pathog. 2022;18:e1010093. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleinnijenhuis J., Quintin J., Preijers F., Joosten L.A.B., Ifrim D.C., Saeed S., Jacobs C., van Loenhout J., de Jong D., Stunnenberg H.G., et al. Bacille Calmette-Guérin induces NOD2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:17537–17542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202870109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arts R.J.W., Moorlag S.J.C.F.M., Novakovic B., Li Y., Wang S.Y., Oosting M., Kumar V., Xavier R.J., Wijmenga C., Joosten L.A.B., et al. BCG vaccination protects against experimental viral infection in humans through the induction of cytokines associated with trained immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:89–100.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giamarellos-Bourboulis E.J., Tsilika M., Moorlag S., Antonakos N., Kotsaki A., Domínguez-Andrés J., Kyriazopoulou E., Gkavogianni T., Domínguez-André J., Damoraki G., et al. Activate: randomized clinical trial of BCG vaccination against infection in the elderly. Cell. 2020;183:315–323.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J., Zhang Q., Wang H., Gong W. The potential roles of BCG vaccine in the prevention or treatment of COVID-19. Front. Biosci. 2022;27:157. doi: 10.31083/j.fbl2705157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sy K.T.L., Haw N.J.L., Uy J. Previous and active tuberculosis increases risk of death and prolongs recovery in patients with COVID-19. Infect. Dis. 2020;52:902–907. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2020.1806353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao Y., Liu M., Chen Y., Shi S., Geng J., Tian J. Association between tuberculosis and COVID-19 severity and mortality: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93:194–196. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.TB/COVID-19 Global Study Group. Casco N., Jorge A.L., Palmero D.J., Alffenaar J.W., Denholm J., Fox G.J., Ezz W., Cho J.G., Skrahina A., et al. Tuberculosis and COVID-19 co-infection: description of the global cohort. Eur. Respir. J. 2022;59:2102538. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02538-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johns Hopkins University Mortality Analyses Johns Hopkins coronavirus resource center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality

- 21.Jassat W., Mudara C., Ozougwu L., Tempia S., Blumberg L., Davies M.A., Pillay Y., Carter T., Morewane R., Wolmarans M., et al. Difference in mortality among individuals admitted to hospital with COVID-19 during the first and second waves in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet. Glob. Health. 2021;9:e1216–e1225. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00289-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Western Cape Department of Health in collaboration with the National Institute for Communicable Diseases South Africa Risk factors for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) death in a population cohort study from the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;73:e2005–e2015. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jassat W., Cohen C., Tempia S., Masha M., Goldstein S., Kufa T., Murangandi P., Savulescu D., Walaza S., Bam J.-L., et al. Risk factors for COVID-19-related in-hospital mortality in a high HIV and tuberculosis prevalence setting in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet. HIV. 2021;8:e554–e567. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(21)00151-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarkar S., Khanna P., Singh A.K. Impact of COVID-19 in patients with concurrent co-infections: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93:2385–2395. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bostanghadiri N., Jazi F.M., Razavi S., Fattorini L., Darban-Sarokhalil D. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and SARS-CoV-2 coinfections: a review. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:747827. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.747827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milross L., Majo J., Cooper N., Kaye P.M., Bayraktar O., Filby A., Fisher A.J. Post-mortem lung tissue: the fossil record of the pathophysiology and immunopathology of severe COVID-19. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022;10:95–106. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00408-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fitzek A., Schädler J., Dietz E., Ron A., Gerling M., Kammal A.L., Lohner L., Falck C., Möbius D., Goebels H., et al. Prospective postmortem evaluation of 735 consecutive SARS-CoV-2-associated death cases. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:19342. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-98499-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y., Garron T.M., Chang Q., Su Z., Zhou C., Qiu Y., Gong E.C., Zheng J., Yin Y.W., Ksiazek T., et al. Cell-type apoptosis in lung during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pathogens. 2021;10:509. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10050509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren Y., Shu T., Wu D., Mu J., Wang C., Huang M., Han Y., Zhang X.-Y., Zhou W., Qiu Y., Zhou X. The ORF3a protein of SARS-CoV-2 induces apoptosis in cells. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020;17:881–883. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0485-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu G., Li Y., Zhang S., Peng H., Wang Y., Li D., Jin T., He Z., Tong Y., Qi C., et al. SARS-CoV-2 promotes RIPK1 activation to facilitate viral propagation. Cell Res. 2021;31:1230–1243. doi: 10.1038/s41422-021-00578-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma H., Zhu Z., Lin H., Wang S., Zhang P., Li Y., Li L., Wang J., Zhao Y., Han J. Pyroptosis of syncytia formed by fusion of SARS-CoV-2 spike and ACE2-expressing cells. Cell Discov. 2021;7:73. doi: 10.1038/s41421-021-00310-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salina A.C.G., Dos-Santos D., Rodrigues T.S., Fortes-Rocha M., Freitas-Filho E.G., Alzamora-Terrel D.L., Castro I.M.S., Fraga da Silva T.F.C., de Lima M.H.F., Nascimento D.C., et al. Efferocytosis of SARS-CoV-2-infected dying cells impairs macrophage anti-inflammatory functions and clearance of apoptotic cells. Elife. 2022;11:e74443. doi: 10.7554/eLife.74443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molnár T., Mázló A., Tslaf V., Szöllősi A.G., Emri G., Koncz G. Current translational potential and underlying molecular mechanisms of necroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:860. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2094-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Man S.M., Karki R., Kanneganti T.-D. Molecular mechanisms and functions of pyroptosis, inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes in infectious diseases. Immunol. Rev. 2017;277:61–75. doi: 10.1111/imr.12534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tay M.Z., Poh C.M., Rénia L., MacAry P.A., Ng L.F.P. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:363–374. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li S., Zhang Y., Guan Z., Li H., Ye M., Chen X., Shen J., Zhou Y., Shi Z.-L., Zhou P., Peng K. SARS-CoV-2 triggers inflammatory responses and cell death through caspase-8 activation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020;5:235. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00334-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanz A.B., Sanchez-Niño M.D., Izquierdo M.C., Gonzalez-Espinoza L., Ucero A.C., Poveda J., Ruiz-Andres O., Ruiz-Ortega M., Selgas R., Egido J., Ortiz A. Macrophages and recently identified forms of cell death. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2014;33:9–22. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2013.771183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lucas C., Wong P., Klein J., Castro T.B.R., Silva J., Sundaram M., Ellingson M.K., Mao T., Oh J.E., Israelow B., et al. Longitudinal analyses reveal immunological misfiring in severe COVID-19. Nature. 2020;584:463–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2588-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leon J., Michelson D.A., Olejnik J., Chowdhary K., Oh H.S., Hume A.J., Galván-Peña S., Zhu Y., Chen F., Vijaykumar B., et al. A virus-specific monocyte inflammatory phenotype is induced by SARS-CoV-2 at the immune–epithelial interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2022;119 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2116853118. e2116853118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maucourant C., Filipovic I., Ponzetta A., Aleman S., Cornillet M., Hertwig L., Strunz B., Lentini A., Reinius B., Brownlie D., et al. Natural killer cell immunotypes related to COVID-19 disease severity. Sci. Immunol. 2020;5:6832. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abd6832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veenith T., Martin H., Le Breuilly M., Whitehouse T., Gao-Smith F., Duggal N., Lord J.M., Mian R., Sarphie D., Moss P. High generation of reactive oxygen species from neutrophils in patients with severe COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:10484. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13825-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee J.S., Shin E.-C. The type I interferon response in COVID-19: implications for treatment. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020;20:585–586. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00429-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aiello A., Grossi A., Meschi S., Meledandri M., Vanini V., Petrone L., Casetti R., Cuzzi G., Salmi A., Altera A.M., et al. Coordinated innate and T-cell immune responses in mild COVID-19 patients from household contacts of COVID-19 cases during the first pandemic wave. Front. Immunol. 2022;13:920227. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.920227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuen C.-K., Lam J.-Y., Wong W.-M., Mak L.-F., Wang X., Chu H., Cai J.-P., Jin D.-Y., To K.K.-W., Chan J.F.-W., et al. SARS-CoV-2 nsp13, nsp14, nsp15 and orf6 function as potent interferon antagonists. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:1418–1428. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1780953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McWhirter S.M., Fitzgerald K.A., Rosains J., Rowe D.C., Golenbock D.T., Maniatis T. IFN-regulatory factor 3-dependent gene expression is defective in Tbk1 -deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:233–238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237236100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xia H., Cao Z., Xie X., Zhang X., Chen J.Y.-C., Wang H., Menachery V.D., Rajsbaum R., Shi P.-Y. Evasion of type I interferon by SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. 2020;33:108234. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miorin L., Kehrer T., Sanchez-Aparicio M.T., Zhang K., Cohen P., Patel R.S., Cupic A., Makio T., Mei M., Moreno E., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Orf6 hijacks Nup98 to block STAT nuclear import and antagonize interferon signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:28344–28354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2016650117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Banerjee A., El-Sayes N., Budylowski P., Jacob R.A., Richard D., Maan H., Aguiar J.A., Demian W.L., Baid K., D’Agostino M.R., et al. Experimental and natural evidence of SARS-CoV-2-infection-induced activation of type I interferon responses. iScience. 2021;24:102477. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berry M.P.R., Graham C.M., McNab F.W., Xu Z., Bloch S.A.A., Oni T., Wilkinson K.A., Banchereau R., Skinner J., Wilkinson R.J., et al. An interferon-inducible neutrophil-driven blood transcriptional signature in human tuberculosis. Nature. 2010;466:973–977. doi: 10.1038/nature09247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dorhoi A., Yeremeev V., Nouailles G., Weiner J., Jörg S., Heinemann E., Oberbeck-Müller D., Knaul J.K., Vogelzang A., Reece S.T., et al. Type I IFN signaling triggers immunopathology in tuberculosis-susceptible mice by modulating lung phagocyte dynamics. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014;44:2380–2393. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen X.-R., Geng R., Li Q., Chen Y., Li S.-F., Wang Q., Min J., Yang Y., Li B., Jiang R.-D., et al. ACE2-independent infection of T lymphocytes by SARS-CoV-2. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022;7:83. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00919-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mehandru S., Poles M.A., Tenner-Racz K., Horowitz A., Hurley A., Hogan C., Boden D., Racz P., Markowitz M. Primary HIV-1 infection is associated with preferential depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes from effector sites in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:761–770. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolday D., Kebede Y., Legesse D., Siraj D.S., McBride J.A., Kirsch M.J., Striker R. Role of CD4/CD8 ratio on the incidence of tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy followed up for more than a decade. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0233049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dorhoi A., Kaufmann S.H.E. Pathology and immune reactivity: understanding multidimensionality in pulmonary tuberculosis. Semin. Immunopathol. 2016;38:153–166. doi: 10.1007/s00281-015-0531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Garra A., Redford P.S., McNab F.W., Bloom C.I., Wilkinson R.J., Berry M.P.R. The immune response in tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2013;31:475–527. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ernst J.D. The immunological life cycle of tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:581–591. doi: 10.1038/nri3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Flynn J.L., Chan J. Immune cell interactions in tuberculosis. Cell. 2022;185:4682–4702. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Minozzi S., Bonovas S., Lytras T., Pecoraro V., González-Lorenzo M., Bastiampillai A.J., Gabrielli E.M., Lonati A.C., Moja L., Cinquini M., et al. Risk of infections using anti-TNF agents in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2016;15:11–34. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2016.1240783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chai Q., Wang L., Liu C.H., Ge B. New insights into the evasion of host innate immunity by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020;17:901–913. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0502-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moraco A.H., Kornfeld H. Cell death and autophagy in tuberculosis. Semin. Immunol. 2014;26:497–511. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Velmurugan K., Chen B., Miller J.L., Azogue S., Gurses S., Hsu T., Glickman M., Jacobs W.R., Porcelli S.A., Briken V. Mycobacterium tuberculosis nuoG is a virulence gene that inhibits apoptosis of infected host cells. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e110. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Behar S.M., Martin C.J., Booty M.G., Nishimura T., Zhao X., Gan H.-X., Divangahi M., Remold H.G. Apoptosis is an innate defense function of macrophages against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:279–287. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nisa A., Kipper F.C., Panigrahy D., Tiwari S., Kupz A., Subbian S. Different modalities of host cell death and their impact on Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2022;323:C1444–C1474. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00246.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oddo M., Renno T., Attinger A., Bakker T., MacDonald H.R., Meylan P.R. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis of infected human macrophages reduces the viability of intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 1998;160:5448–5454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Augenstreich J., Arbues A., Simeone R., Haanappel E., Wegener A., Sayes F., Le Chevalier F., Chalut C., Malaga W., Guilhot C., et al. ESX-1 and phthiocerol dimycocerosates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis act in concert to cause phagosomal rupture and host cell apoptosis. Cell Microbiol. 2017;19:e12726. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.López M., Sly L.M., Luu Y., Young D., Cooper H., Reiner N.E. The 19-kDa Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein induces macrophage apoptosis through toll-like receptor-2. J. Immunol. 2003;170:2409–2416. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lim Y.-J., Choi J.-A., Choi H.-H., Cho S.-N., Kim H.-J., Jo E.-K., Park J.-K., Song C.-H. Endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway-mediated apoptosis in macrophages contributes to the survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pajuelo D., Gonzalez-Juarbe N., Tak U., Sun J., Orihuela C.J., Niederweis M. NAD+ depletion triggers macrophage necroptosis, a cell death pathway exploited by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Rep. 2018;24:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stutz M.D., Ojaimi S., Allison C., Preston S., Arandjelovic P., Hildebrand J.M., Sandow J.J., Webb A.I., Silke J., Alexander W.S., Pellegrini M. Necroptotic signaling is primed in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected macrophages, but its pathophysiological consequence in disease is restricted. Cell Death Differ. 2017;25:951–965. doi: 10.1038/s41418-017-0031-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lerner T.R., Borel S., Greenwood D.J., Repnik U., Russell M.R.G., Herbst S., Jones M.L., Collinson L.M., Griffiths G., Gutierrez M.G. Mycobacterium tuberculosis replicates within necrotic human macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 2017;216:583–594. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201603040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Beckwith K.S., Beckwith M.S., Ullmann S., Sætra R.S., Kim H., Marstad A., Åsberg S.E., Strand T.A., Haug M., Niederweis M., et al. Plasma membrane damage causes NLRP3 activation and pyroptosis during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2270. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16143-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rastogi S., Ellinwood S., Augenstreich J., Mayer-Barber K.D., Briken V. Mycobacterium tuberculosis inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome activation via its phosphokinase PknF. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17:e1009712. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sheerin D., Abhimanyu, Peton N., Peton N., Vo W., Allison C.C., Wang X., Johnson W.E., Coussens A.K. Immunopathogenic overlap between COVID-19 and tuberculosis identified from transcriptomic meta-analysis and human macrophage infection. iScience. 2022;25:104464. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Blanco-Melo D., Nilsson-Payant B.E., Liu W.-C., Uhl S., Hoagland D., Møller R., Jordan T.X., Oishi K., Panis M., Sachs D., et al. Imbalanced host response to SARS-CoV-2 drives development of COVID-19. Cell. 2020;181:1036–1045.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moreira-Teixeira L., Mayer-Barber K., Sher A., O’Garra A. Type I interferons in tuberculosis: Foe and occasionally friend. J. Exp. Med. 2018;215:1273–1285. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Petrone L., Petruccioli E., Vanini V., Cuzzi G., Gualano G., Vittozzi P., Nicastri E., Maffongelli G., Grifoni A., Sette A., et al. Coinfection of tuberculosis and COVID-19 limits the ability to in vitro respond to SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;113:S82–S87. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hildebrand R.E., Chandrasekar S.S., Riel M., Touray B.J.B., Aschenbroich S.A., Talaat A.M. Superinfection with SARS-CoV-2 has deleterious effects on Mycobacterium bovis BCG immunity and promotes dissemination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022;10:e0307522. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.03075-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mahida R.Y., Scott A., Parekh D., Lugg S.T., Hardy R.S., Lavery G.G., Matthay M.A., Naidu B., Perkins G.D., Thickett D.R. Acute respiratory distress syndrome is associated with impaired alveolar macrophage efferocytosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2021;58:2100829. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00829-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Anft M., Paniskaki K., Blazquez-Navarro A., Doevelaar A., Seibert F.S., Hölzer B., Skrzypczyk S., Kohut E., Kurek J., Zapka J., et al. COVID-19-Induced ARDS is associated with decreased frequency of activated memory/effector T cells expressing CD11a++ Mol. Ther. 2020;28:2691–2702. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.The RECOVERY Collaborative Group Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. Overseas. Ed. 2021;384:693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies REACT Working Group. Sterne J.A.C., Murthy S., Diaz J.V., Slutsky A.S., Villar J., Angus D.C., Annane D., Azevedo L.C.P., Berwanger O., et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324:1330–1341. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gopalaswamy R., Subbian S. Corticosteroids for COVID-19 therapy: potential implications on tuberculosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:3773. doi: 10.3390/IJMS22073773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chung W.S., Chen Y.F., Hsu J.C., Yang W.T., Chen S.C., Chiang J.Y. Inhaled corticosteroids and the increased risk of pulmonary tuberculosis: a population-based case-control study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2014;68:1193–1199. doi: 10.1111/IJCP.12459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Martinez A.N., Mehra S., Kaushal D. Role of interleukin 6 in innate immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;207:1253–1261. doi: 10.1093/INFDIS/JIT037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tang W., Leonhardt L., Pervez A., Sarvepalli S. A case of pleural tuberculosis vs latent tuberculosis reactivation as a result of COVID-19 infection and treatment. J. Community Hosp. Intern. Med. Perspect. 2022;12:89–93. doi: 10.55729/2000-9666.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Garg N., Lee Y.I. Reactivation TB with severe COVID-19. Chest. 2020;158:A777. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.724. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cho T., Khatchadourian C., Nguyen H., Dara Y., Jung S., Venketaraman V. A review of the BCG vaccine and other approaches toward tuberculosis eradication. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021;17:2454–2470. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1885280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tran V., Liu J., Behr M.A. BCG vaccines. Microbiol. Spectr. 2014;2 doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MGM2-0028-2013. MGM2-0028-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Spencer J.C., Ganguly R., Waldman R.H. Nonspecific protection of mice against Influenza virus infection by local or systemic immunization with Bacille Calmette-Guerin. J. Infect. Dis. 1977;136:171–175. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Starr S.E., Visintine A.M., Tomeh M.O., Nahmias A.J. Effects of immunostimulants on resistance of newborn mice to Herpes Simplex type 2 infection. Exp. Biol. Med. 1976;152:57–60. doi: 10.3181/00379727-152-39327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kaufmann E., Sanz J., Dunn J.L., Khan N., Mendonça L.E., Pacis A., Tzelepis F., Pernet E., Dumaine A., Grenier J.-C., et al. BCG educates hematopoietic stem cells to generate protective innate immunity against tuberculosis. Cell. 2018;172:176–190.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Grimes C.L., Ariyananda L.D.Z., Melnyk J.E., O’Shea E.K. The innate immune protein Nod2 binds directly to MDP, a bacterial cell wall fragment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:13535–13537. doi: 10.1021/ja303883c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sabbah A., Chang T.H., Harnack R., Frohlich V., Tominaga K., Dube P.H., Xiang Y., Bose S. Activation of innate immune antiviral responses by Nod2. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:1073–1080. doi: 10.1038/ni.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fu W., Ho P.C., Liu C.L., Tzeng K.T., Nayeem N., Moore J.S., Wang L.S., Chou S.Y. Reconcile the debate over protective effects of BCG vaccine against COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:8356. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87731-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Escobar L.E., Molina-Cruz A., Barillas-Mury C. BCG vaccine protection from severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:17720–17726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2008410117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Berg M.K., Yu Q., Salvador C.E., Melani I., Kitayama S. Mandated Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination predicts flattened curves for the spread of COVID-19. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eabc1463. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lindestam Arlehamn C.S., Sette A., Peters B. Lack of evidence for BCG vaccine protection from severe COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:25203–25204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2016733117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.BCG Immunization coverage estimates by country world health organization. https://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.80500?lang=en

- 99.Kaufmann E., Khan N., Tran K.A., Ulndreaj A., Pernet E., Fontes G., Lupien A., Desmeules P., McIntosh F., Abow A., et al. BCG vaccination provides protection against IAV but not SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. 2022;38:110502. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Upton C.M., van Wijk R.C., Mockeliunas L., Simonsson U.S.H., McHarry K., van den Hoogen G., Muller C., von Delft A., van der Westhuizen H.-M., van Crevel R., et al. Safety and efficacy of BCG re-vaccination in relation to COVID-19 morbidity in healthcare workers: a double-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;48:101414. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shariq M., Sheikh J.A., Quadir N., Sharma N., Hasnain S.E., Ehtesham N.Z. COVID-19 and tuberculosis: the double whammy of respiratory pathogens. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2022;31:210264. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0264-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Satapathy P., Ratho R.K., Sethi S. Immunopathogenesis in SARS-CoV-2 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis: the danger of overlapping crises. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13:1065124. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1065124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Luke E., Swafford K., Shirazi G., Venketaraman V. TB and COVID-19: an exploration of the characteristics and resulting complications of Co-infection. Front. Biosci. 2022;14:6. doi: 10.31083/j.fbs1401006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Marais B.J., Chakaya J., Swaminathan S., Fox G.J., Ehtesham N.Z., Ntoumi F., Zijenah L., Maurer M., Zumla A. Tackling long-term morbidity and mortality after successful tuberculosis treatment. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:641–642. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ong C.W.M., Migliori G.B., Raviglione M., MacGregor-Skinner G., Sotgiu G., Alffenaar J.W., Tiberi S., Adlhoch C., Alonzi T., Archuleta S., et al. Epidemic and pandemic viral infections: impact on tuberculosis and the lung. Eur. Respir. J. 2020;56:2001727. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01727-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Walaza S., Tempia S., Dawood H., Variava E., Wolter N., Dreyer A., Moyes J., von Mollendorf C., McMorrow M., von Gottberg A., et al. The impact of Influenza and tuberculosis interaction on mortality among individuals aged ≥15 Years hospitalized with severe respiratory illness in South Africa, 2010–2016. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019;6:ofz020. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]