Abstract

Purpose:

Child abuse is regarded as a life-course social determinant of health problems. However, little is known about the nutritional status of physically abused children and their cumulative effect on child behavior. The present study aimed to examine the non-anemic iron deficiency status of abused children and the combined effect of physical abuse and non-anemic iron deficiency on child behavior in China.

Methods:

This cross-sectional study comprised 314 children aged 11–14 (12.30 ± 0.57) years old from Jintan, China. Children self-reported their physical abuse experiences and behavior problems. Blood iron and hemoglobin concentrations were also measured.

Results:

Thirty-eight percent of children reported physical abuse experience, 17.5% had non-anemic iron deficiency, and the two risk factors co-occurred in 8.0% children. Physically abused children were more likely to be affected by non-anemic iron deficiency than their non-abused counterparts. Children who had experienced both physical abuse and non-anemic iron deficiency reported more behavior problems than children with neither or either risk factors.

Conclusions:

Physically abused children are more likely to have non-anemic iron deficiency. Children with the presence of both physical abuse experience and non-anemic iron deficiency have more behavior problems. There is a need to prevent both child abuse and non-anemic iron deficiency simultaneously to maintain normal child behavior development.

Keywords: Child physical abuse, Iron deficiency, Behavior, School children, China

Introduction

Child abuse, especially physical abuse, was long regarded as an acceptable disciplinary strategy and widely practiced in the Chinese societies (Fang et al., 2015; K. Ji & Finkelhor, 2015; Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Alink, 2013). However, it has been recognized as a life-course social determinant of many health problems across the world. Of them, behavioral problems are of particular concern for school children. Research shows that child abuse experiences are associated with internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems in children and adolescents, such as depression, anxiety, aggressive and violent behaviors (Gilbert et al., 2009; Heim, Shugart, Craighead, & Nemeroff, 2010). Childhood and adolescent behavioral problems can cause difficulties in school adaptation (Masten et al., 2005), increase the risk for suicidal attempts (Perez, Jennings, Piquero, & Baglivio, 2016) in children and predict risky health behavior in emerging adulthood (Sentse, Kretschmer, Haan, & Prinzie, 2016). Despite the potential detrimental effects in childhood and beyond, evidence-based programs that target child abuse remain largely underexplored in Mainland China (Man, Barth, Li, & Wang, 2017).

Many prevention programs have been launched in other countries (Chen & Chan, 2016) However, a recent meta-analysis suggested that the present child abuse prevention programs did not significantly improve behaviors of abused children (Casillas, Fauchier, Derkash, & Garrido, 2016), indicating that some other factors may exist and affect abuse-related behavior problems. The nutritional factor may be one of the factors that could influence the relationship between child abuse and behavior. Prior studies show that abused children are more likely to experience childhood malnutrition (Yount, DiGirolamo, & Ramakrishnan, 2011), thus posing additional risk for emotional and behavioral impairments Specifically, studies in western countries found that 25–35% of maltreated children showed malnutrition and consequent growth retardation (Birrell & Birrell, 1968; Oates, Peacock, & Forrest, 1984). Children with suspected abuse had significantly lower dietary micronutrient intake in the US (Harper, Ekvall, Ekvall, & Pan, 2014). Similar to child abuse, malnutrition, especially iron deficiency, is highly prevalent in China (Global Burden of Disease Pediatrics Collaboration, 2016), and has exhibited both short- and long-term effects on emotional and behavioral problems (Liu et al., 2014). However, few Chinese studies have specifically investigated the nutritional status of abused children and their combined contribution to behavioral problems.

The aim of this study is twofold: to examine the association between non-anemic iron deficiency and child physical abuse in a community sample of Chinese school-aged children; and whether child physical abuse and non-anemic iron deficiency have an accumulative effect on behavioral problems. The findings from our study will inform future preventions and interventions for the interrelated public issues of child abuse, malnutrition and behavioral problems in children, and eventually shed light on health consequences in adulthood.

Methods

Design and Sample

The present study used secondary data collected during the Wave II of China Jintan Child Cohort Study. The cohort study is an ongoing prospective-designed longitudinal project with the main purpose to investigate the neural mechanism of lead exposure and child neurobehavioral outcomes. In 2004, the China Jintan Child Cohort Study used a multiple-stage sampling method and enrolled 1656 Chinese children (55.5% boys, 44.5% girls), aged 3–5 years, in Jintan City (Jintan City became the Jintan District of Changzhou City, Jiangsu Province, China on June 1, 2015). The research team first set up a stratified sampling process to select four preschools across different types of location: rural (2 preschools), suburban (1 preschool) and urban (1 preschool), and then recruited all preschoolers in each preschool using a cluster sampling strategy. These preschoolers were regarded as representative of children aged 3–6 years old in Jintan city in China in terms of sex, age and ethnicity. Details of the cohort study design were described elsewhere (Liu et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2015).

During 2005–2007, 1385 out of the 1656 preschoolers and their parents and teachers participated in the Wave I of data collection (Liu et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2015). About 80.1% of these children were followed up with for the Wave II data collection during 2011–2013 (Liu et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2014). Child behavior problems, blood iron level and hemoglobin were measured twice at both Wave I and II. Child physical abuse was measured in 2013 at Wave II. For the purpose of the study, we included 414 children who had cross-sectional information of child physical abuse, the blood level of micronutrients and hemoglobin, as well as behaviors collected in 2013. The majority of them were 6th graders aged 11 and 12 years old (range 11–14, mean age 11.80 ± 0.67 years old).

Written informed consent was obtained from parents and oral informed assent was obtained from children prior to data collection. Data of child abuse were collected by distributing the questionnaire in the classroom during the regularly scheduled class time. Children's fasting blood samples were collected by nurses in Jintan Hospital and then stored and analyzed per protocol. Children self-reported their behavior problems using an established questionnaire in a quiet waiting room in Jintan Hospital. The participating children were instructed that they could skip any questions or withdraw from the study anytime. After the questionnaire survey, information about psychological and social service resources, such as information about the Jintan Maternal Health Center and Jintan Hospital and materials about parenting and child development were provided to all children, parents and teachers in case they needed help. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania and the Ethics Committee of the Jintan Hospital.

Measures

Child Physical Abuse

The Chinese Version of The Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998) was used to assess physical abuse by mother and father abusers in the previous 12 months using the severe and very severe physical assault subscale (7 items, in which two example items are listed: “[Mother/Father] hit me with a fist or kicked me hard” and “[Mother/Father] beat me up”). Children were asked to provide information regarding whether their parents (mother and father separately) displayed these behaviors (0 = “No”, 1 = “Yes”). Non-abused children were those with zeros on all items in the subscales for both mother and father abusers. Otherwise, they were labeled as physically abused survivors. The CTSPC is one of the most widely used tool to assess child abuse among children aged 10 years or older. The Chinese version of CTSPC showed satisfactory to good reliabilities (Chan, 2012; Cui, Xue, Connolly, & Liu, 2016). Out of the 414 children, 350 children filled out the questionnaire.

Serum Iron and Hemoglobin Level

Trained pediatric nurses collected approximately two tubes of 0.5 mL of venous blood from 329 children at fasting. One tube of blood was used to assess the serum iron and other trace elements in the Research Center for Environmental Medicine of Children at Shanghai Jiaotong University using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. The other tube was used to measure blood hemoglobin concentrations by the 7–22 photoelectric colorimeter at the Jintan Maternal Child Health Center. The detailed analytical procedure was reported elsewhere (X. Ji & Liu, 2015; Zhao et al., 2009). Iron deficiency was defined as blood iron level below 7.5 μg/dL (Liu et al., 2014). Hemoglobin concentrations higher than 115 g/L were considered as non-anemic.

Child Behavior

Children (n = 339) self-reported their behaviors using the Chinese version of the 112-item Youth Self-Report (YSR, Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) that is designed for adolescents aged 11–18 years. The YSR is a widely used tool for assessing adolescent behavioral problems including internalizing (i.e., anxiety, depression, somatic complaints and suicide) and externalizing behaviors (i.e., aggression, delinquency, and hyperactivity) over the last 6 months. Participants were asked to rate on a 3-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (often true). The YSR has shown good psychometric properties among the youth in different countries (Ivanova et al., 2007; Leung et al., 2006; Verhulst et al., 2003). The Chinese version of the YSR is also reported to have satisfactory reliability and validly (Liu et al., 1997). In the preliminary analysis of the study, we calculated the normalized T scores from the raw scores of total behavior problems (combining both internalizing and externalizing problems). Higher T scores indicate more behavioral problems.

Covariates

Covariates included child sex, age, family location in preschool (i.e. urban, suburban, or rural), socioeconomic status (SES), hemoglobin concentrations and body mass index (BMI). SES was generated according to the procedure described elsewhere (Straus, 2004). It was the standardized z score of the sum of z scores of children's father's and mothers' years of education and monthly wage. Missing values of mothers' and fathers' years of education and monthly wages were replaced by the sample means of respective variables. BMI was calculated by using weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters.

Statistical Analysis

Sample characteristics were summarized by descriptive statistics. Bivariate analysis including t-tests, ANOVA, chi-square test and Pearson correlation were used to examine the differences in demographic characteristics and physical abuse between children with and without non-anemic iron deficiency, as well as bivariate associations with behavior problems. The generalized linear model (GLM) with logit link was used to analyze the relationship between non-anemic iron deficiency and physical abuse controlling for covariates. Then, two generalized liner models were constructed to analyze the associations of behavior problems with both iron deficiency and physical abuse. Model 1 was constructed by including non-anemic iron deficiency and physical abuse as individual independent variables first, and then adding an interaction term of physical abuse and iron deficiency. Model 2 was constructed by using a risk indicator of non-anemic iron deficiency and physical abuse, which has four categories (no risks, non-anemic iron deficiency only, physical abuse only, and both non-anemic iron deficiency and abuse), together with other covariates as independent variables. The GLMs were clustered at family residence location to adjust the standard errors. The significance level was set at α = 0.05 level. Analyses were performed using STATA 13.0 for Windows (College Station, TX) in 2016.

Results

We obtained completed data on child physical abuse, serum iron level, and behaviors from 317 children. Among them, three children with hemoglobin levels <115 g/L were excluded from the analysis. There were no statistical differences in child sex, age, and family location and SES between excluded and attributed children. Among the final sample of 314 children, 54.9% were boys and their mean age was 12.30 (SD = 0.57) years old. The majority children were from urban (41.4%) or suburban (43.3%) areas in Jintan and 15.3% were from rural areas. More than one-third of children reported physical abuse by at least one parent in the preceding year, 17.5% children had non-anemic iron deficiency, and the two risk factors co-occurred in 25 (8.0%) children.

Children living in rural areas reported a relatively high rate of physical abuse experience (50.0%) than their peers in urban (38.5%) and suburban (33.1%) areas. However, such group difference did not reach the statistical significance level (p > 0.05). There were no statistical differences in socioeconomic status or family location between children with and without physical abuse experience, between children with and without non-anemic iron deficiency, and behavior problems (ps > 0.05). There was not significant difference in age between children with and without physical abuse or iron deficiency, and behavior scores were not statistically-significantly related to child age (ps > 0.05). More boys than girls reported physical abuse experience in the previous year (χ2 = 13.66, p < 0.001) and non-anemic iron deficiency (χ2 = 4.20, p = 0.04). Physically abused children or children with non-anemic iron deficiency reported significantly more behavior problems (p values < 0.05). See Table 1.

Table 1.

The sociodemographic characteristics and bivariate associations in the sample (n = 317).

| Total | Physical abuse | t/χ 2 | Iron deficiency | χ 2 | Behavior problem | t/F/r | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | ||||||

| Total | 317 | 51.75 ± 10.44 | |||||||

| Sex | 13.66 *** | 4.20 * | 1.74 | ||||||

| Boys | 172 (54.8) | 81 (47.1) | 91 (52.9) | 37 (21.5) | 135 (78.5) | 52.75 ± 10.94 | |||

| Girls | 142 (45.2) | 38 (26.8) | 104 (73.2) | 18 (12.7) | 124 (87.4) | 50.70 ± 9.75 | |||

| Age | 12.30 ± 0.57 | 12.28 ± 0.63 | 12.31 ± 0.53 | 0.42 | 12.28 ± 0.57 | 12.31 ± 0.57 | 0.32 | −0.05 | |

| SES | 0.04 ± 1.07 | −0.03 ± 1.12 | 0.08 ± 1.04 | 0.87 | 0.10 ± 0.99 | 0.03 ± 1.09 | 0.44 | −0.10 | |

| Location | 4.34 | 0.13 | 1.13 | ||||||

| Urban | 130 (41.4) | 50 (38.5) | 80 (61.5) | 22 (16.9) | 108 (83.1) | 52.69 ± 11.38 | |||

| Suburban | 136 (43.3) | 45 (33.1) | 91 (66.9) | 25 (18.4) | 111 (81.6) | 50.81 ± 8.61 | |||

| Rural | 48 (15.3) | 24 (50.0) | 24 (50.0) | 8 (16.7) | 40 (83.3) | 52.31 ± 12.40 | |||

| Hemoglobin level (g/L) | 134.54 ± 8.01 | 134.05 ± 8.44 | 134.84 ± 7.74 | 0.84 | 132.73 ± 7.92 | 134.93 ± 7.99 | 1.86 | − 0.07 | |

| BMI | 19.42 ± 3.64 | 19.84 ± 3.84 | 19.16 ± 3.0 | 1.60 | 20.10 ± 4.39 | 19.27 ± 3.46 | 1.53 | 0.06 | |

| Physical abuse | 1.62 | 4.94 *** | |||||||

| Yes | 119 (37.9) | 25 (20.0) | 94 (80.0) | 55.42 ± 11.32 | |||||

| No | 195 (62.1) | 30 (15.4) | 165 (84.6) | 49.63 ± 9.26 | |||||

| Iron deficiency | 2.01 * | ||||||||

| Yes | 55 (17.5) | 54.39 ± 10.43 | |||||||

| No | 259 (82.5) | 51.28 ± 10.40 | |||||||

Notes. SES, Social economic status. Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Although there was no significant association between physical abuse and non-anemic iron deficiency at the bivariate level (χ2 = 1.63, p = 0.20), physically abused children were slightly more likely to have from iron deficiency (OR = 1.15, 95%CI = 1.06–1.25, p = 0.001) controlling for hemoglobin levels, BMI and the other covariates.

Table 2 shows the results of Model 1 and Model 2. The results of Model 1 show that physically abused children reported significantly higher YSR score than children without such experience (β = 5.24, 95% CI = 2.20–8.28, p < 0.001). Children with non-anemic iron deficiency also showed more behavior problems (β = 2.49, 95% CI = 0.44–4.54, p = 0.02). By adding the interaction term of child physical abuse and iron deficiency in Model 1, a further analysis showed that the interaction term was not statistically significant (β = 0.34, 95% CI = −2.99–3.33, p = 0.92).

Table 2.

The effect of physical abuse and iron deficiency on child behavior.

| Behavior problem | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||

| Physical abuse | |||

| No | Reference | Reference | |

| Yes | 5.24 (2.20, 8.28) *** | 5.20 (1.57, 8.84) *** | |

| Iron deficiency | |||

| No | Reference | Reference | |

| Yes | 2.49 (0.44, 4.54) * | 2.42 (−0.63, 5.47) | |

| Physical abuse × Iron deficiency | 0.17 (−2.99, 3.33) | ||

| Model 2 | |||

| Risk indicator | |||

| Both physical abuse and iron deficiency | Reference | ||

| Physical abuse only | −2.49 (−4.54, −0.43) * | ||

| Iron deficiency only | −5.24 (−6.44, −4.04) *** | ||

| Neither | −7.50 (−10.83, −4.16) *** |

Notes. Boldface indicates statistical significance (*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001). Models were adjusted child sex, age, socioeconomic status, family location, hemoglobin level and BMI.

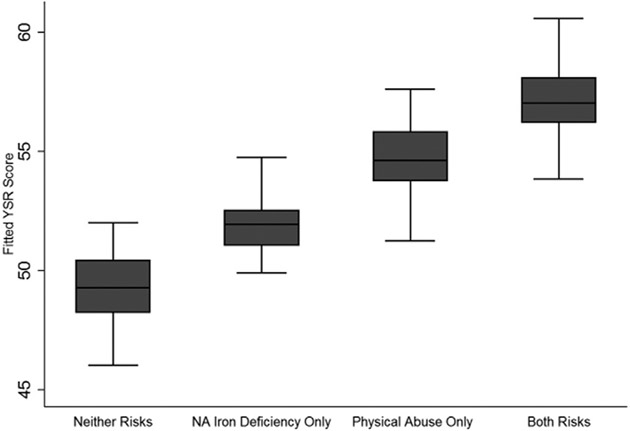

Results of Model 2 show that children with both physical abuse experience and non-anemic iron deficiency reported significantly more behavior problems than children with neither of the two risk factors (β = −7.85, 95% CI = −10.83 – −4.16, p < 0.001), physically abused children only (β = 2.49, 95% CI = −4.54 – −0.43, p = 0.02), or children with non-anemic iron deficiency only (β = −5.24, 95% CI = −6.44 to −4.04, p < 0.001) (See Fig. 1). A post-hoc analysis showed that the combined effect on child behavior was not significantly worse than the sum of the effects of child abuse and non-anemic iron deficiency (β = 0.23, p = 0.89), indicating an additive pattern of the combined effect.

Fig. 1.

The boxplot of fitted behavior problem score among children with different risk factors (i.e. neither physical abuse nor non-anemic iron deficiency, physical abuse only, non-anemic iron deficiency only and both physical abuse and non-anemic iron deficiency). The fitted YSR scores were adjusted by child sex, age, socioeconomic status, family location, hemoglobin level and body mass index (BMI). NA, non-anemic. YSR, Youth Self Report.

Discussions

To our best knowledge, the present study was the first to report the micronutrient status of abused children and their combined effect on child behavior development in China. Using a community sample of Chinese children, we found that social risk factors, such as child abuse and biological risk factors such as non-anemic iron deficiency are likely to present simultaneously. Specifically, physical abuse exposure increased the likelihood of the presence of non-anemic iron deficiency. In addition, children with both physical abuse and non-anemic iron deficiency simultaneously demonstrated significantly more behavior problems (7 points more in T score) than their counterparts with only one risk factor or without neither risk factors in an additive manner.

The finding suggests physically abused children were more likely to suffer from non-anemic iron deficiency, highlighting that vulnerable children were more vulnerable to other risk factors simultaneously. Such co-occurrence could be due to physically abused children also experiencing physical neglect through parents failing to meet their child's need for nutrition and food. A parental abuser may also withhold food on purpose as a method to “discipline’/abuse his/her children. It is also possible that a third variable contributes to both child abuse and iron deficiency and, therefore, confound the co-occurrence of the two risks. For example, the low socioeconomic status may be a confounder that correlates with both child abuse (Liao, Lee, Roberts-Lewis, Hong, & Jiao, 2011) and iron deficiency (Pasricha, Drakesmith, Black, Hipgrave, & Biggs, 2013). However, after controlling the SES in this study, the association between child physical abuse and iron deficiency remains statistically significant, suggesting such co-occurrence is independent of socioeconomic status in this sample of children.

Children with both physical abuse experience and non-anemic iron deficiency showed more behavior problems than their counterparts with only one risk factor or without neither risks. The combined effect of the biosocial risks is additive, indicating that their effects on child behavior combine linearly to account for variance in outcomes (Rauer, Karney, Garvan, & Hou, 2008). This finding aligns with the cumulative risk effect model in that the accumulation of risk factors, rather than a single factor, is more important in determining the risk of adverse outcome (Appleyard, Egeland, Dulmen, & Alan Sroufe, 2005). Children with risk factors from multiple domains are more prone to negative developmental outcomes. The finding is consistent with the existing evidence that children with multiple types of abuse (Appleyard et al., 2005), or multiple deficiencies of micronutrients (Liu et al., 2014) showed more behavior problems. The present findings contribute to the literature that children with the co-occurred child abuse and iron deficiency may be at-risk of significantly more behavior problems.

The existing literature has suggested multiple pathways linking child physical abuse and iron deficiency to behavior problems. Child physical abuse has been found to be associated with impaired cognitive functioning, emotion process and social development, probably due to altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function, changes in brain structure and function, neurobiological mechanism and epigenetic modifications (for reviews, Chen & Baram, 2016; Sandi & Haller, 2015). Iron deficiency may exert similar deleterious effect on neurobehavioral function. Emerging evidence suggests that iron deficiency anemia in early life has deleterious effects on child neurocognitive and behavioral development and the underlying brain activity (Kennedy, Wallin, Tran, & Georgieff, 2016; Lozoff et al., 2006). A recent experimental study on college-aged women showed that, subclinical iron deficiency, even without anemia, was associated with decreased performance on neurobehavioral tasks and altered brain activity during the tasks (Wenger, DellaValle, Murray-Kolb, & Haas, 2017). Furthermore, the review by Hoeijmakers, Lucassen, and Korosi (2014) suggests that different forms of early life adversity (in this case, child physical abuse and iron deficiency) may have synergistic effects on human development because they lead to very similar cognitive outcomes. This further supports the cumulative effect of physical abuse and iron deficiency on child behavior problems revealed in this study.

In addition, the present study also found gender discrepancy in both child abuse and non-anemic iron deficiency. The finding that more boys reported physical abuse experience in the previous year is consistent with previous Chinese studies (Cui et al., 2016; Liao et al., 2011). In our sample, boys also demonstrated more iron deficiency in the present study. Several studies in Asia showed that boy infants were at higher risk of iron deficiency and iron-deficient anemia due to more iron requirement for body lean mass growth (Wieringa et al., 2007). However, girls have been considered more susceptible to iron deficiency during adolescence, especially after the onset of menarche. Whereas the median age of menarche among healthy Chinese girls is 12.83 years (Mao et al., 2011), the majority of the girl participants in the present study were aged 11 and 12 years old and might not have had menstruation yet. Thus, iron deficiency was not a significant problem among these girl participants. Further studies are needed to explore the gender difference in iron status from a developmental perspective.

The present findings should be interpreted cautiously due to several study limitations. First, the sample size of participants with both physical abuse and iron deficiency is relatively small, thus affecting the stability of statistical estimates of the combined effect of the two risk factors. In addition, the sample size also limits the possibility to examine gender difference in the relationship between physical abuse, iron deficiency and behavior problems. However, we consider our study as the first step to call for attention to the comorbidity of child abuse and malnutrition in the Chinese society. Further studies of a large sample size are needed to replicate the finding. Second, only one social risk factor (physical abuse), and one biological risk factor (non-anemic iron deficiency) were examined in the present study because they are very prevalent socio-/bio-risks among Chinese children (K. Ji & Finkelhor, 2015; MDG Achievement Fund, 2013). Given the fact that risk factors do not operate in isolation and they may affect child development in a cumulative manner (Appleyard et al., 2005), more studies are needed to further explore cumulative effects of multiple biological and socio-risk factors on behavior and health outcomes. Last but not least, all the relationship demonstrated in the study cannot be interpreted as a causal relationship.

Conclusion

The study shows that physically abused children are more likely to experience non-anemic iron deficiency. Children with the presence of both physical abuse experience and non-anemic iron deficiency have more behavior problems. Therefore, it is important to prevent both child abuse and non-anemic iron deficiency simultaneously to maintain normal child behavior development.

Implications for Practice

The present study provides implications for child health practice in China and societies with the similar sociocultural perceptions of child abuse. The additive pattern of the combined effect of physical abuse and iron deficiency suggests that health intervention programs should target to prevent child abuse and eliminate iron deficiency simultaneously to help with child behavior development. Some child health promotion programs in China has been shown successful or promising improvement in child nutrition (Sylvia et al., 2013; The United Nations Children's Emergency Fund, 2012; Wang, Stewart, Yuan, & Chang, 2015); however, to our knowledge, no successful/effective prevention programs of child abuse have been launched or studied in China. Practitioners and researchers can work together to develop evidence-based prevention programs of child abuse based on the existing successful programs promoting child nutrition and further investigate their feasibility, fidelity and effectiveness. Moreover, in the treatment of child behavior problems, it may be helpful to eliminate re-exposure to child abuse and improve children's nutritional status to complement with other behavioral interventions and treatment.

In addition, it is important to detect the risk social determinants early to help children maintain normal behavior development. Health professionals, especially pediatricians, pediatric nurses and home-visiting nurses play important roles in health promotion to improve nourishment among children. They also have a unique opportunity in detecting abused children and provide support for victims of domestic violence (Dickson & Tutty, 1996). However, their roles in child abuse have not been acknowledged in China. For example, screening for child abuse is still not a mandatory responsibility for Chinese health professionals in any settings. Based on the findings, we suggest that Chinese health professionals pay special attention to screen for child abuse history for children with iron deficiency to identify vulnerable children with multiple risk factors.

Acknowledgements

We thank the children and their parents for participating in the study. NC thanks the China Scholarship Council (CSC) for support for her PhD program.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute of Environment Health Sciences grants (R01-ES018858, K01-ES015877, and K02-ES019878) to JL and the Research Award from the Office of Nursing Research at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Achenbach T, & Rescorla L (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment Burlington, VT. University of Vermont. Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Appleyard K, Egeland B, Dulmen MH, & Alan Sroufe L (2005). When more is not better: The role of cumulative risk in child behavior outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(3), 235–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell RG, & Birrell JH (1968). The maltreatment syndrome in children: A hospital survey. The Medical Journal of Australia, 2(23), 1023–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casillas KL, Fauchier A, Derkash BT, & Garrido EF (2016). Implementation of evidence-based home visiting programs aimed at reducing child maltreatment: A meta-analytic review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 53, 64–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL (2012). Comparison of parent and child reports on child maltreatment in a representative household sample in Hong Kong. Journal of Family Violence, 27(1), 11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, & Chan KL (2016). Effects of parenting programs on child maltreatment prevention: A meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse, 17(1), 88–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, & Baram TZ (2016). Toward understanding how early-life stress reprograms cognitive and emotional brain networks. Neuropsychopharmacology, 41(1), 197–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui N, Xue J, Connolly CA, & Liu J (2016). Does the gender of parent or child matter in child maltreatment in China? Child Abuse & Neglect, 54,1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson F, & Tutty LM (1996). The role of public health nurses in responding to abused women. Public Health Nursing, 13(4), 263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Fry DA, Ji K, Finkelhor D, Chen J, Lannen P, & Dunne MP (2015). The burden of child maltreatment in China: A systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 93(3), 176–185C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, &Janson S (2009). Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet, 373(9657), 68–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Burden of Disease Pediatrics Collaboration. (2016). Global and national burden of diseases and injuries among children and adolescents between 1990 and 2013: Findings from the global burden of disease 2013 study. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(3), 267–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper E, Ekvall S, Ekvall V, & Pan W (2014). The nutritional status of children with suspected abuse. In Atrosh F (Ed.), Pharmacology and nutritional intervention in the treatment of disease (pp. 327–329). INTECH. [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Shugart M, Craighead WE, & Nemeroff CB (2010). Neurobiological and psychiatric consequences of child abuse and neglect. Developmental Psychobiology, 52(7), 671–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeijmakers L, Lucassen PJ, & Korosi A (2014). The interplay of early-life stress, nutrition, and immune activation programs adult hippocampal structure and function. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 7, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova MY, Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA, Dumenci L, Almqvist F, Bilenberg N, … Erol N (2007). The generalizability of the Youth Self-Report syndrome structure in 23 societies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(5), 729–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji K, & Finkelhor D (2015). A meta-analysis of child physical abuse prevalence in China. Child Abuse & Neglect, 43, 61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X, & Liu J (2015). Associations between blood zinc concentrations and sleep quality in childhood: A cohort study. Nutrients, 7(7), 5684–5696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy BC, Wallin DJ, Tran PV, & Georgieff MK (2016). Long-term brain and behavioral consequences of early-life iron deficiency. Fetal development (pp. 295–316). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Leung PW, Kwong SL, Tang CP, Ho TP, Hung SF, Lee CC, … Liu WS (2006). Test–retest reliability and criterion validity of the Chinese version of CBCL, TRF, and YSR. Journal ofChild Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(9), 970–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao M, Lee AS, Roberts-Lewis AC, Hong JS, &Jiao, K. (2011). Child maltreatment in China: An ecological review of the literature. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(9), 1709–1719. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Cao S, Chen Z, Raine A, Hanlon A, Ai Y, … Jintan Cohort Study Group (2015). Cohort profile update: The China Jintan child cohort study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 44(5) (1548–1548I). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Hanlon A, Ma C, Zhao SR, Cao S, & Compher C (2014). Low blood zinc, iron, and other sociodemographic factors associated with behavior problems in preschoolers. Nutrients, 6(2), 530–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, McCauley L, Leung P, Wang B, Needleman H, Pinto-Martin J, & Group JC (2011). Community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to study children's health in China: Experiences and reflections. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48(7), 904–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, McCauley LA, Zhao Y, Zhang H, Pinto-Martin J, & Jintan Cohort Study Group (2010). Cohort profile: The China Jintan child cohort study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 39(3), 668–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Guo C, Liu L, Wang A, Hu L, Tang M, … Zhao G (1997). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of Youth Self Report. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 11 (4), 200–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lozoff B, Beard J, Connor J, Felt B, Georgieff M, & Schallert T (2006). Long-lasting neural and behavioral effects of iron deficiency in infancy. Nutrition Reviews, 64 (suppl_2), S34–S43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man X, Barth RP, Li YE, & Wang Z (2017). Exploring the new child protection system in Mainland China: How does it work? Children and Youth Services Review, 76, 196–202. [Google Scholar]

- Mao S, Jiang J, Sun X, Zhao Q, Qian B, Liu Z, … Qiu Y (2011). Timing of menarche in Chinese girls with and without adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Current results and review of the literature. European Spine Journal, 20(2), 260–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Roisman GI, Long JD, Burt KB, Obradović J, Riley JR, … Tellegen A (2005). Developmental cascades: Linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Developmental Psychology, 41(5), 733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MDG Achievement Fund (2013). China: Improving nutrition and food safety for China's most vulnerable women and children. Retrieved from http://www.mdgfund.org/node/179.

- Oates RK, Peacock A, & Forrest D (1984). The development of abused children. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 26(5), 649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasricha SR, Drakesmith H, Black J, Hipgrave D, & Biggs BA (2013). Control of iron deficiency anemia in low- and middle-income countries. Blood, 121(14), 2607–2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez NM, Jennings WG, Piquero AR, & Baglivio MT (2016). Adverse childhood experiences and suicide attempts: The mediating influence of personality development and problem behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauer AJ, Karney BR, Garvan CW, & Hou W (2008). Relationship risks in context: A cumulative risk approach to understanding relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 70(5), 1122–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandi C, & Haller J (2015). Stress and the social brain: Behavioural effects and neurobiological mechanisms. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 16(5), 290–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentse M, Kretschmer T, Haan A, &Prinzie P (2016). Conduct problem trajectories between age 4 and 17 and their association with behavioral adjustment in emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(8), 1633–1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, & Alink LR (2013). Cultural–geographical differences in the occurrence of child physical abuse? A meta-analysis of global prevalence. International Journal of Psychology, 48(2), 81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA (2004). Prevalence of violence against dating partners by male and female university students worldwide. Violence Against Women, 10(7), 790–811. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, & Runyan D (1998). Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(4), 249–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvia S, Luo R, Zhang L, Shi Y, Medina A, & Rozelle S (2013). Do you get what you pay for with school-based health programs? Evidence from a child nutrition experiment in rural China. Economics of Education Review, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- The United Nations Children's Emergency Fund (2012). Nutrition-UNICEF China protecting children's rights. Retrieved from http://www.unicefchina.org/en/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=lists&catid=119. [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst FC, Achenbach TM, Van der Ende J, Erol N, Lambert MC, Leung PW, … Zubrick SR (2003). Comparisons of problems reported by youths from seven countries. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(8), 1479–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Stewart D, Yuan Y, & Chang C (2015). Do health-promoting schools improve nutrition in China? Health Promotion International, 30(2), 359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger MJ, DellaValle DM, Murray-Kolb LE, & Haas JD (2017). Effect of iron deficiency on simultaneous measures of behavior, brain activity, and energy expenditure in the performance of a cognitive task. Nutritional Neuroscience, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieringa FT, Berger J, Dijkhuizen MA, Hidayat A, Ninh NX, Utomo B, … Winichagoon P (2007). Sex differences in prevalence of anaemia and iron deficiency in infancy in a large multi-country trial in south-east Asia. The British Journal of Nutrition, 98(05), 1070–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yount KM, DiGirolamo AM, & Ramakrishnan U (2011). Impacts of domestic violence on child growth and nutrition: A conceptual review of the pathways of influence. Social Science & Medicine, 72(9), 1534–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao T, Chen T, Qiu Y, Zou X, Li X, Su M, … Jia W (2009). Trace element profiling using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry and its application in an osteoarthritis study. Analytical Chemistry, 81(9), 3683–3692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]