Abstract

Purpose:

Ataxia Telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR) is a pivotal component of the DNA damage response and repair pathways that is activated in responses to cytotoxic cancer treatments. Several ATR inhibitors (ATRi) are in development that block the ATR mediated DNA repair and enhance the damage associated with cytotoxic therapy. BAY-1895344 (elimusertib) is an orally available ATRi with preclinical efficacy that is in clinical development. Little is known about the pharmacokinetics (PK) which is of interest because tissue exposure and ATR inhibition may relate to toxicities or responses.

Methods:

To evaluate BAY-1895344 PK, a sensitive LC-MS/MS method was utilized for quantitation in mouse plasma and tissues. PK studies in mice were first conducted to determine dose linearity. In vivo metabolites were identified and analyzed semi-quantitatively. A compartmental PK model was developed to describe PK behavior. An extensive PK study was then conducted in tumor-bearing mice to quantitate tissue distribution for relevant tissues.

Results:

Dose linearity was observed from 1 to 10 mg/kg PO, while at 40 mg/kg PO bioavailability increased approximately 4-fold due to saturation of first-pass metabolism, as suggested by metabolite analyses and a developed compartmental model. Longer half-lives in PO treated mice compared to IV treated mice indicated absorption-rate limited elimination. Tissue distribution varied but showed extensive distribution to bone marrow, brain, and spinal cord.

Conclusion:

Complex PK behavior was limited to absorption processes which may not be recapitulated clinically. Tissue partition coefficients may be used to contrast ATR inhibitors with respect to their efficacy and toxicity.

Keywords: Pharmacokinetics, small molecule inhibitor of ATR, BAY-1895344, tissue distribution, LC/MS

1. INTRODUCTION

Radiotherapy (RT) and chemotherapy used in cancer treatments often rely on causing irreparable DNA damage to cancer cells that results in cell death. This resulting damage is recognized and repaired by the DNA damage response (DDR), a complex network of proteins and pathways which cumulatively act to repair damage and mitigate cell death [1]. Central to the DDR is Ataxia Telangiectasia and Rad3-realted (ATR), a serine/threonine kinase that is activated by DNA damage and in turn initiates several DDR related signaling cascades [1]. This occurs largely at stalled replication forks with single-stranded breaks (SSBs) but can also be caused by resection during the homologous recombination that occurs after double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs) [2]. In addition to other DDR processes, ATR can activate cell cycle arrest, largely through activation of its major effector kinase CHK1, which promotes suppression of origin firing, resolution of replication stress, and ultimately repair to DNA [3].

ATR is highly relied upon by many cancers to maintain basic fidelity from persistent genomic instability experienced during cancer development and maintenance, including stress experienced due to the loss of the G1 checkpoint caused by p53 mutations [3]. Although non-diseased tissues utilize ATR, they rely on it less than cancer cells and thus a therapeutic window exists to exploit the dependency of cancer cells on ATR to resolve damage and avoid cell death [4,2].

ATR inhibitors (ATRi) are a relatively novel class of kinase inhibitors that are largely designed to be combined with chemotherapy or RT with the ultimate goal of limiting DDR and extending the efficacy of a primary DNA damaging agent [4]. Four ATRi are currently in clinical development: BAY-1895344 (elimusertib), AZD6738 (ceralasertib), M6620 (VX-970, berzosertib), and M4344 (VX-803) [3,5]. Several questions about ATRi remain unanswered including those surrounding the selectivity of ATRi for enhancing tumor damage without increasing damage at surrounding healthy tissue where ATR is necessary, and exacerbating the already narrow toxicity profiles of RT and chemotherapy [6]. Pivotal to this question is the role drug exposure has in defining efficacy and toxicity. Investigations into the distribution of an ATRi to the tumor and relevant tissues may allow conclusions to be drawn about the relationship of pharmacokinetics (PK) with pharmacodynamic (PD) responses of efficacy and toxicity. Adding to this is the novel finding that ATRi also have an immunological component to their response, with evidence that CD8+ T-cell anti-tumor responses are enhanced when ATRi is administered with RT [7,8].

BAY-1895344 is a highly potent orally available ATR inhibitor currently in clinical development and is currently in 8 clinical trials (Clinicaltrials.gov accessed date 9/22/21)[9]. Preclinical studies have identified it as being efficacious as both a monotherapy and in combination with DNA damaging agents with particular sensitivity against cell lines harboring mutations to Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated (ATM), a related DDR kinase [10]. Current information on BAY-1895344 PK is limited but preclinical evidence suggests its ability to sustain systemic concentrations in mice above the various cell line IC50 [10,11,9]. There is currently no information regarding any BAY-1895344 related effects on the immunological responses observed with other ATRi. Thorough description of BAY-1895344 distribution to tumor and relevant tissue sites may reveal PK-based therapeutic windows that can be compared with other ATRi class members.

In an effort to support the development of ATRi and BAY-1895344, several PK studies of BAY-1895344 PK in mice were completed to thoroughly determine the drug distribution to tumor, and tissues with toxicological and immunological relevance. Prior to this, the dose linearity and bioavailability, as well as in vivo metabolism, were investigated to fully understand PK mechanisms and identify an appropriate dose to administer for an extensive tissue distribution study. The results reported here will provide future studies a PK-based framework to help explain PD responses of efficacy, toxicity and immunology and additionally allow direct comparisons of PK with other ATRi class members.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

BAY-1895344 was purchased from AdooQ Bioscience (Irvine, CA) and [13C2D3]-BAY-1895344 (Suppl.Figure 1) was custom synthesized and purchased from ALSACHIM (Illkirch-Graffenstaden, France). Water and acetonitrile (both HPLC grade), ethanol, formic acid, DMSO were obtained through Fisher Scientific (Fairlawn, NJ). Cremophor was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Saline was purchased from SteriCare (Haltom City, TX).

2.2. Mice

Specific pathogen-free female Balb/c mice (5-7 weeks of age) were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA). Mice were allowed to acclimate to the University of Pittsburgh Animal Facility for at least 1 week before studies were initiated. To minimize exogenous infection, mice were maintained in microisolator cages and handled in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 2011) and on a protocol approved by the University of Pittsburgh IACUC. Ventilation and airflow in the animal facility were set to 12 changes/h. Room temperature was regulated at 72 ± 4 °F and the rooms were kept on automatic 12-h light/dark cycles. The mice received Prolab ISOPRO RMH 3000, Irradiated Lab Diet (PMI Nutrition International, Brentwood, MO) and water ad libitium. Mice at each time point were stratified by body weight (and by tumor size if applicable). Throughout all studies, mice were routinely weighed and monitored for changes in health.

2.3. Dose Linearity and Bioavailability Studies

Mice (N=3 per time point) were dosed with 4 mg/kg BAY-1895344 IV with a 30 s bolus in the tail vein or 1, 4, 10, and 40 mg/kg BAY-1895344 PO was administered by gavage. The vehicle for all groups was 10% ethanol, 10% cremophor, and 80% saline. Sample collection time points were 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 360, and 1440 min. Vehicle controls were included at 5 and 1440 min. Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and the following tissues collected: blood, kidney, lung, skeletal muscle, and brain. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture using EDTA anticoagulated syringes, transferred to microcentrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 4 min to separate plasma and red blood cells (RBCs). Pooled urine and feces were collected over ice from mice in the 1440 min groups housed in metabolic cages.

2.4. Extensive Tissue Distribution PK Study

Mice were injected subcutaneously on the right flank with 1x106 CT26 cells, a murine colorectal carcinoma cell line from BALB/c mice, obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with L-glutamine (BioWhittaker Inc., Walkersville, MD), containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 100 units of penicillin/mL and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin (Biofluids, BioSource, Rockville, MD) in an incubator with 95% air, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity at 37 °C. Cells were verified and checked for mycoplasm by IDEXX BioAnalytics (Westbrook, ME). Implantation and tumor growth were monitored twice weekly with a digital caliper. When tumors were approximately 200 mm3, mice were stratified into time groups (N=3) primarily using body weight and secondarily using tumor size. Mice were administered 10 mg/kg PO through oral gavage. Sample collection time points were 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, 360, 960, and 1440 min and vehicle controls were included at 5 and 1440 min. At each time point, mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and the following tissues collected: blood, liver, kidney, spleen, lung, skeletal muscle, brain, heart, fat, tumor, small intestine (contents were removed by flushing with 3 ml of PBS), esophagus (flushed with PBS), spinal cord, thymus, draining lymph node, non-draining lymph node, and bone marrow. Bone marrow was obtained by flushing both femurs from each mouse with PBS. The bone marrow from each mouse was isolated by centrifugation at 12,000 x g and the supernatant was removed except for approximately 50 μL. Prior to analysis of the bone marrow, the bone marrow was resuspended, sonicated and a 20 μl aliquot was taken for determination of protein using the Bio-Rad protein assay following the manufacturer’s instructions with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Blood was processed to obtain plasma and urine and feces were collected as described above.

2.5. Bioanalysis

An LC-MS/MS assay was implemented on an Agilent (Palo Alto, CA) 1290 Infinity II Autosampler and Binary Pump and a SCIEX (Concord, ON, Canada) 6500+ mass spectrometer to quantitate BAY-1895344 in plasma, RBCs, tissues, and tumor.

Mass spectrometer conditions were determined using infusion of need standards and were optimized as follows: 20 L/h curtain gas, 5,000 ion spray voltage, 300 °C temperature, 70 L/h gas 1 and gas 2, medium collision cell gas, 50V declustering potential, 10 V entrance potential, 50 V collision energy, 10 V collision exit potential. MRM channels were 376.3>318.2 for BAY-1895344 and 380.3>322.2 for [13C2D3]-BAY-1895344, both with dwell times of 0.1 s.

Chromatographic separation was still achieved using a Phenomenex (Torrance, CA) Synergi Polar-RP 80A column (4 μm, 2 mm × 50 mm) at ambient temperature with a gradient mobile phase program consisting of mobile phase solvent A (water with 0.1% formic acid (v/v)) and mobile phase solvent B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (v/v)). A gradient HPLC method was used with an initial condition of 10% mobile phase B pumped at 0.5 mL/min that was increased to 95% over the course of 3.0 min. This composition was maintained between 3.1 and 5.0 min but the flow rate was increased to 1.0 mL/min. At 5.1 min the composition was returned to initial composition and pumped at a 1.0 mL/min until 7.0 min to re-equilibrate the column.

Duplicate standard curves with calibrators consisting of 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 500, 1,000 and 5,000 ng/mL, in addition to blank plasma, were prepared fresh on days of analysis using control Balb/c mouse plasma (Innovative Research, Novi, MI). QCs were prepared in bulk and stored at −80 °C, with concentrations of 1.5 (QCL), 150 (QCM), and 4,000 ng/mL (QCH). Samples were prepared by adding 10 μL of 0.1 μg/mL of [13C2D3]-BAY-1895344 to each 50 μL sample followed by the addition of 200 μL of acetonitrile for protein precipitation. Samples were then vortexed for 1 minute, centrifuged for 10 min at 13,500 x g, and 100 μL of the resulting supernatant transferred to HPLC vials. The injection volume was 3 μL. Retention times for both analyte and IS were 1.5 min. Curve fitting was accomplished through linear regression with 1/y2 weighting.

To validate the assay, a triplicate standard curve with QCs (N=6, per level) was prepared in plasma and analyzed to determine analytical accuracy and precision. Assay performance in matrices of RBC and tissue homogenate was determined by spiking control samples to the 150 ng/mL QCM level in replicates of 4 and determining their accuracy based on a calibration curve constructed in mouse plasma. Analyte recovery and matrix effect were analyzed in plasma by comparing QCM samples with both QCM level spiked neat and plasma background samples (N=4).

For tissue and tumor homogenate analysis, samples were homogenized with 3 parts PBS (v/g)) and further diluted with control plasma as needed.

A representative chromatogram of the BAY-1895344 and IS response of an LLQ sample can be seen in Suppl.Figure 2. The accuracy and precision of a triplicate standard curve and QCs met the batch acceptance criteria for FDA bioanalytical method validation with accuracies of calibrators and QCs ranging between 90.2 to 113.0% with precisions <10.3% (see Suppl.Table 1) [12].

2.6. Metabolite Identification and Quantification

Metabolites were identified and examined by comparing unique peaks and masses found in the urine of mice administered BAY-1895344 to vehicle administered mice. First, broad-range mass scans (MS) were used to identify unique peaks as well as investigate common metabolic transitions. These identified m/z traces were sequentially analyzed with product ion scans to identify MRM transitions representing unique metabolites that were then added to the existing LC-MS/MS method and used for metabolite semi-quantitation. This was accomplished by reporting IS-normalized metabolite response as the measure for concentration. Due to a lack of reference standards, the assay was not further optimized or validated for quantitating metabolites. Additionally, metabolite stability and linearity in response are unknown.

2.7. Pharmacokinetic Analysis

2.7.1. Noncompartmental Analysis

Noncompartmental (NC) PK was determined using GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA) using the linear trapezoidal method and Bailer method of AUC determination for estimates of exposure in plasma, RBC, and tissues [13]. PK parameters or analysis requiring dose was adjusted for the actual dose as determined using measurements of dosing solution. Dose-normalized plasma exposures, Cmax and AUC, of PO treated groups of the dose linearity studies were compared using ANOVA tests to evaluate dose linearity.

Tissue partition coefficients (PTissue) and RBC partitioning (PRBC) were calculated using Eq. (1) and compared among PO treated groups using ANOVA tests.

For analysis of urine and feces from 1440 min groups, urine was diluted at least 1:10 in control plasma and feces was homogenized 3:1 in PBS. The resulting concentrations were multiplied by the volume or weight to convert to a total amount and then divided by 3 to account for the number of mice per cage. These amounts were then divided by the average total amount of drug administered to calculate the percent excreted by urine and feces, see Eq. (2). Renal clearance (ClR) was calculated by dividing the excreted amount by the plasma AUC, see Eq. (3) [14].

Plasma metabolite data was used to determine semi-quantitative exposure as well as metabolic ratios, using Eq. (4). The MR among PO treated groups in the dose linearity studies were compared using ANOVA testing. Metabolite presence was also determined in urine and feces.

2.7.2. Intestinal Contribution to Oral Bioavailability

The contribution of gut to oral bioavailability was estimated by calculating the contribution of liver processes to bioavailability from IV data and stripping this contribution from the observed bioavailability [15,16]. Assuming IV drug clearance was restricted to hepatic processes, the predicted bioavailability based on liver processes, FH, was calculated from IV PK by using the liver extraction ratio, EH, (see Eq. (5)) constructed using literature values of hepatic blood flow, QH, in conjunction with study specific PK items including the fraction of drug excreted in urine (fe) and total blood clearance, ClBlood, as seen in Eq. (6) [16,15]. Fe was derived from the amount of drug measured in urine (Ae) and the total amount of drug administered, see Eq. (7). ClBlood was defined by multiplying the observed plasma clearance (ClPlasma) by the ratio of plasma exposure (AUCPlasma) to total blood exposure (AUCBlood), see Eq. (8). AUCBlood was calculated using hematocrit (HCT) to construct total blood exposure contributions from exposure in RBC (AUCRBC) and plasma, see Eq. (9).

Observed in vivo bioavailabilities, FObserved, contain both contributions from absorption and gut processes, FA and FG respectively (see Eq. (10)) [15]. For the purposes of this exercise it was assumed that absorption was complete with all drug entering intestinal enterocytes (FA = 1), and the predicted hepatic contribution was subtracted from the observed bioavailability to yield the gut contribution to bioavailability for each PO treatment group, see Eq. (11).

2.7.3. Compartmental Model

A unified compartmental PK model was developed in ADAPT5 [17, ADAPT5 Users Guide] to fit the data. Naïve-pooled concentration-time data from each study was used to optimize PK parameters that were shared between each treatment group. Model performance was determined and reported using parameter CV%, R2, AIC (Akaike information criterion), as well as visual inspection of standardized residual plots. Bioavailability estimates from the model were produced by calculating the AUC of predicted concentrations at times identical to observations. The developed model was then used to simulate expected plasma concentrations in the extensive PK study. Separately, tumor and plasma time concentration data from the extensive PK study was used to extend this model to add an uncoupled tumor compartment [18].

2.8. Plasma Protein Binding

Plasma protein binding of BAY1895344 was determined using rapid equilibrium dialysis (RED) devices (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Freshly collected Balb/c mouse plasma was spiked in replicates of N=3 at 50, 500, and 5,000 ng/mL using stock solutions with <0.1% organic solvent in final samples, for a 16 h incubation.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Dose Linearity and Bioavailability Studies

3.1.1. Noncompartmental Analysis

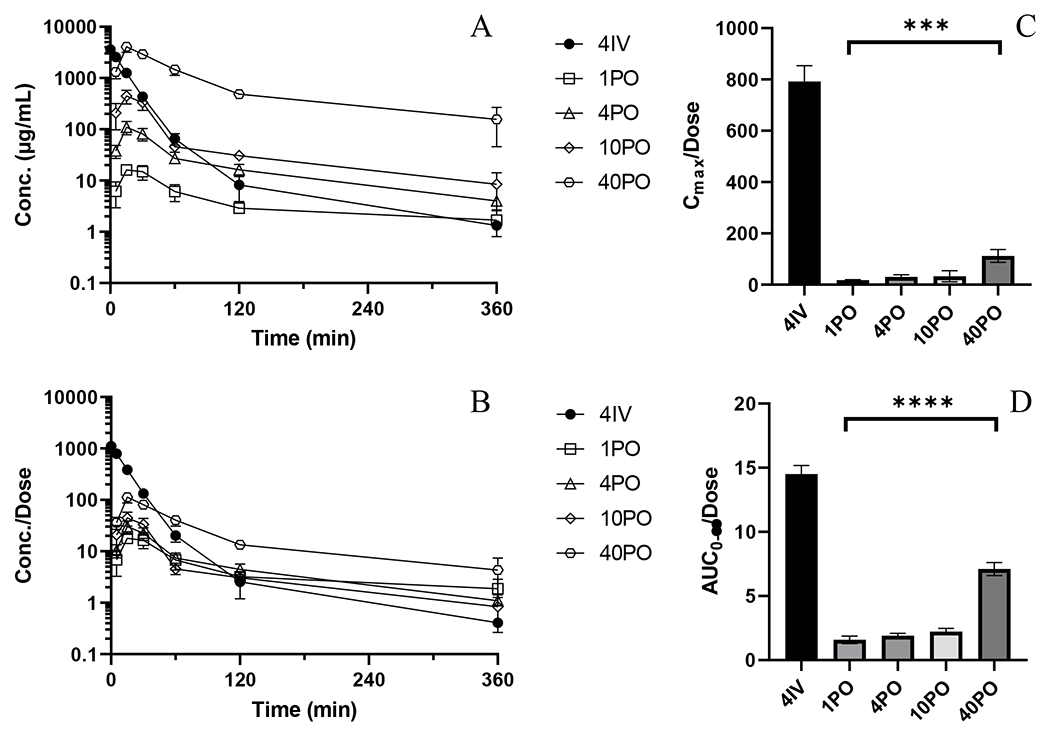

Plasma concentration versus time profiles for all dose linearity and bioavailability studies are depicted in Figure 1A and PK parameters are detailed in Table 1. All plasma samples had concentrations above the 0.5 ng/mL LLQ up to 360 min and fell below the LLQ at 1440 min. IV administered mice displayed a biphasic concentration-time profile. The Cmax for all PO administered mice was observed at 15 min. Dose-normalized concentrations (Figure 1B) of the 1, 4 and 10 mg/kg PO treated groups were largely superimposable while the 40 PO group was distinctly higher indicating a non-linearity that was also reflected in Cmax and AUC (Figure 1C and D) as well as calculated apparent clearance (Cl/F/kg) and volumes of distribution (Vd/F/kg). This non-linearity corresponded to a four-fold increase in the observed bioavailability between 1 and 40 mg/kg doses. IV clearance was 55.8 mL/min/kg and the volume of distribution was 7.31 L/kg. The half-live in PO treated mice appeared to be absorption rate limited (e.g., flip-flop kinetics) with longer half-lives in PO treated mice (125 to 182 min) compared to IV treated mice (91 min). Among PO treated mice, there was no discernable trend in half-life between doses, suggesting that while the absorption rate was constant with dose, even if the bioavailable fraction did change with dose.

Figure 1.

PK and NCA of BAY-1895344 from bioavailability and dose linearity studies. A) Mean plasma concentration versus time profiles for 4IV (•), 1PO (○), 4PO (◇), 10PO (△), 40PO (□). B) Mean plasma concentrations normalized by administered dose versus time profiles C) Dose-normalized Cmax (ANOVA test of PO treated groups, p=0.0005) D) Dose-normalized AUC0-∞ (ANOVA test of PO treated groups, p<0.0001). Error bars represent ± SD for concentrations and ± SEM for AUC.

Table 1.

Noncompartmental BAY-1895344 PK parameters

| Route Dose (mg/kg) |

IV 4 |

PO 1 |

PO 4 |

PO 10 |

PO 40 |

p-value | PO-extf 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual dose (mg/kg) | 3.25 | 0.900 | 3.64 | 10.0 | 36.3 | 8.97 | |

|

| |||||||

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 2,573 (200) | 16.0 (1.9) | 110 (32) | 330 (216) | 4,073 (906) | 649 (266) | |

| Cmax/dosea | 792 (62) | 18 (2) | 30 (9) | 33 (22) | 112 (25) | 0.0005 | 72.4 (29.7) |

| Tmax (min) | 5 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | |

| AUC0-360 (μg/mL•min) | 58.1 (2.6) | 1.49 (0.16) | 7.64 (0.72) | 22.2 (2.4) | 284 (21) | 30.7 (4.7) | |

| AUC0-360/dose a,c | 17.9 (0.8) | 1.65 (0.17) | 2.11 (0.20) | 2.22 (0.24) | 7.83 (0.57) | <0.0001 | 3.43 (0.53) |

| AUC0-∞ (μg/mL•min) | 58.2 (2.6) | 1.94 (0.16) | 8.37 (0.72) | 23.8 (2.4) | 307 (21) | 32.3 (4.7) | |

| AUC0-∞ /dose | 17.9 (0.8) | 2.15 (0.17) | 2.30 (0.20) | 2.37 (0.24) | 8.46 (0.57) | 3.60 (0.53) | |

| F d | - | 0.120 | 0.129 | 0.133 | 0.488 | ||

| Cl (mL/min/kg) e | 55.8 | 465 | 432 | 420 | 114 | 278 | |

| Vd (L/kg) e | 7.31 | 122 | 77.7 | 78.4 | 24.2 | 43.2 | |

| Half-life (min) | 90.9 | 182 | 125 | 129 | 147 | 108 | |

| 0-24h urine (% dose) | 0.102 | 0.0238 | 0.0150 | 0.0129 | 0.0314 | 0.0192 | |

| ClR (mL/min/kg) | 0.0569 | 0.111 | 0.0650 | 0.05643 | 0.0371 | 0.0534 | |

| 0-24h feces (% dose) | 1.04 | 1.91 | 2.45 | 1.82 | 5.20 | 1.16 | |

Values represent the mean and error (SD for Cmax, SEM for AUC)

Calculated using exact dose

ANOVA test of PO routes only

% extrapolated ranges from 0.3 to 23.1%

Based on AUC0-∞

Apparent parameter for initial 4 PO doses 2, 7.5, 20, and 75 mg/kg

Plasma PK parameters from tissue distribution study

Renal excretion of unaltered BAY-1895344 represented negligible contributor to overall clearance with <0.1% of administered drug recovered across all groups. In feces, <1% of unaltered drug could be recovered after IV dosing. PO treated groups had slightly larger amounts in feces and a modest proportional trend, ranging from 1.7 to 4.7%, between lowest and highest PO doses, respectively, indicating absorption was almost complete and non-uniform prior to entering intestinal enterocytes.

Tissue analysis revealed all tissues generally mirrored profiles of plasma, indicating their distribution was perfusion-rate limited (Suppl.Figure 3A–E and Suppl.Table 2). RBC and tissue partition coefficients revealed several trends between dose and administration route, but no comparisons gained statistical significance (Suppl.Figure 4A–E and Suppl.Table 3). Lung and kidney partitioning had little variability among PO treated groups, but all were approximately 50% higher than the IV group.

3.1.2. Metabolite Analysis

Visual assessment of total ion count (TIC) MS scan chromatograms from treated mouse urine revealed no readily apparent unique peaks discernable from vehicle control treated plasma. Several common metabolic mass changes to the parent m/z such as +16 (hydroxyl), +32 (dihydroxyl), −14 (demethyl), and +176 (glucuronide) were extracted from the TIC and uniquely present in treated urine compared to vehicle urine. Product ion scans of these m/z in urine identified discernable product ions that were used to create MRM channels that were incorporated into the LC-MS/MS method and used to analyze urine and plasma. Of these, four MRM channels revealed dose-dependent responses which are listed by identifying name, retention time (RT), MRM, relative mass change from parent, and proposed metabolic mechanism in Suppl.Table 4. Chromatograms of these metabolite MRM traces in urine can be seen in Suppl.Figure 5A–D. Two separate peaks were observed in the direct glucuronide MRM channel, indicating unique metabolites but only the larger 1.3 min peak was used for analysis. The selected product ion of this conjugated metabolite was the parent BAY-1895344 m/z of 376.3. This glucuronide also appeared to crosstalk into the parent BAY-1895344 MRM channel at the 1.3 min RT (Suppl.Figure 5E) but with sufficient distance from the parent peak not to affect parent signal. One of the identified dihydroxy metabolites, M2C, utilized a product ion of 318.3 m/z, identical to BAY-1895344.

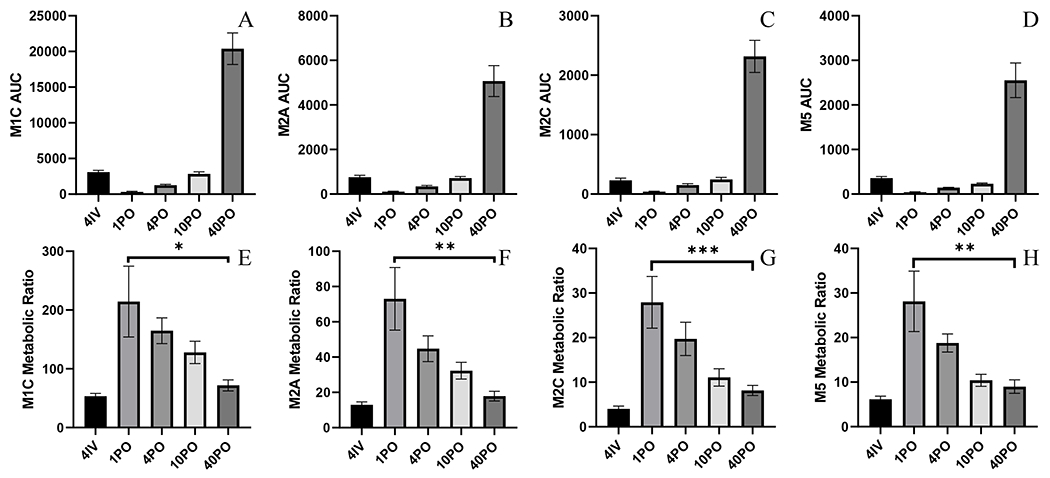

All four metabolites were detected in treated plasma samples out until 360 min in all treated groups (Suppl.Figure 6A–E). All metabolites had terminal half-lives approximately parallel to their respective parent BAY-1895344, indicating they are formation-rate limited. All metabolite exposures increased with dose (Figure 2A–D and Table 2). Metabolic ratios (MR) were statistically different among PO treated groups, with a trend of decreasing MR with dose (Figure 2E–H). All IV related MR were smaller than any related MR in the PO groups, indicating all four metabolites are largely formed during the absorption and first-pass process.

Figure 2.

Metabolite NCA from dose linearity and bioavailability studies A) M1C AUC0-360 B) M2A AUC0-360 C) M2C AUC0-360 D) M5 AUC0-360 E) M1C MR (P=0.0269) F) M2A MR (P=0.0014) G) M2C MR (P=0.0007) H) M5 MR (P=0.0011). Metabolic ratios constructed from metabolite and parent AUC0-360. Error bars represent ± SEM.

Table 2.

BAY-1895344 Metabolite Semi-Quantitative NCA from Dose Linearity and Bioavailability Studies

| Metabolite ID |

Route Dose (mg/kg |

IV 4 |

PO 1 |

PO 4 |

PO 10 |

PO 40 |

p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1C | AUC0-360 | 3,100 (235) | 319 (83) | 1,261 (83) | 2,848 (292) | 20,383 (2,208) | |

| MR AUC0-360 | 53.4 (4.7) | 214 (60) | 165 (22) | 128 (19) | 71.8 (9.4) | 0.0269 | |

|

| |||||||

| M2A | AUC0-360 | 754 (89) | 109 (24) | 343 (46) | 719 (72) | 5,068 (692) | |

| MR AUC0-360 | 13.0 (1.6) | 73.1 (17.7) | 44.8 (7.3) | 32.3 (4.7) | 17.8 (2.8) | 0.0014 | |

|

| |||||||

| M2C | AUC0-360 | 232 (36) | 41.6 (7.5) | 151 (25) | 247 (35) | 2,316 (271) | |

| MR AUC0-360 | 4.00 (0.64) | 27.9 (19.7) | 19.7 (11.1) | 11.1 (2.0) | 8.15 (1.12) | 0.0007 | |

|

| |||||||

| M5 | AUC0-360 | 357 (38) | 41.9 (9.1) | 144 (8) | 232 (16) | 2,553 (389) | |

| MR AUC0-360 | 6.16 (0.71) | 28.1 (6.8) | 18.8 (2.0) | 10.4 (1.3) | 8.99 (1.52) | 0.0011 | |

Values are reported as mean and error (SEM)

ANOVA testing and reported p-value limited only to PO data

3.1.3. Intestinal Contribution to Oral Bioavailability

The hepatic contribution to bioavailability based on IV PK was estimated to result in an FLiver of 0.111, see Suppl.Table 5. This was then used to discern the intestinal metabolism component of first-pass metabolism using observed bioavailabilities to produce an Fgut of 1.08 for the lowest PO dose and increasing with each dose (Suppl.Table 6). Fgut values greater than 1.0 indicate saturation of liver metabolism in addition to saturation of intestinal metabolism.

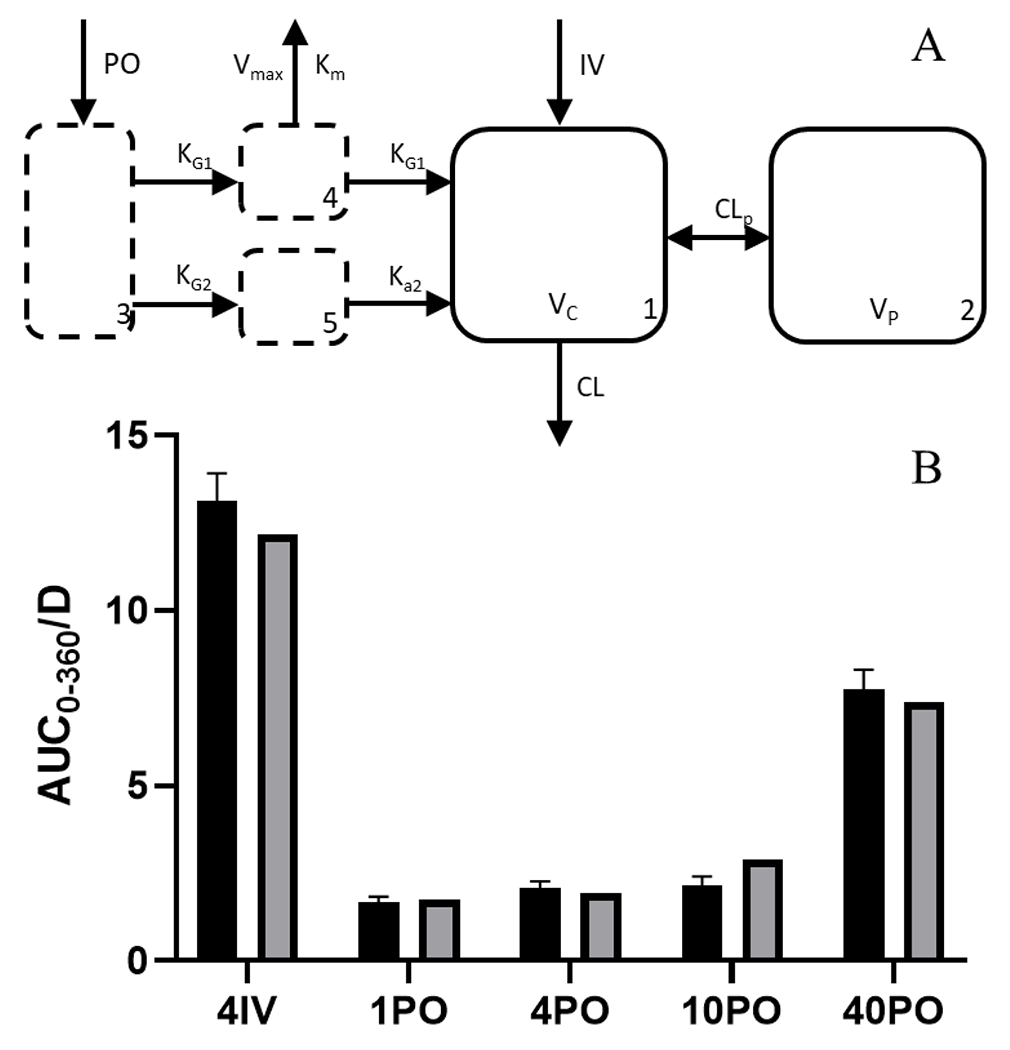

3.1.4. Compartmental Model

A compartmental method was developed that shared all PK parameters and accommodated both absorption rate limited kinetics and the saturable first pass metabolism that resulted in dose-dependent bioavailability (Figure 3A). PO delivery was incorporated through a multi-compartment absorption process where drug was delivered to a central gut lumen compartment and then transferred into a gut wall compartment by a rate the rate constant KG1. From here, drug was able to be either transferred into the central compartment via the same KG1 rate constant or be eliminated through a saturable presystemic clearance process represented by a Vmax and Km. To accommodate for absorption rate limited kinetics, a third absorption compartment was added that allowed drug transfer from the gut lumen compartment into a parallel gut wall compartment by the rate constant KG2. Drug in this compartment was then able to flow into the central compartment by rate constant Ka2 and thereby define the terminal slope of PO groups.

Figure 3.

Unified compartmental PK model A) model structure showing drug administered through the gut lumen with the ability to move to a saturable first-pass metabolism absorption site and a non-saturable absorption site, both of which lead to a central two-compartment model B) AUC0-360 (±SEM) observed by NCA in dose linearity and bioavailability groups (solid black) and compartmental model prediction (solid grey).

The model performed proficiently with estimated PK parameters, model performance and fit reported in Suppl.Table 7 and Suppl.Figure 7A–J. Model-based estimation was similar to NCA values for AUC (Figure 3B) as well as bioavailability (Suppl.Table 8) and overall captured the non-linearity. Equations used in the model can be seen in Eq. (12)–(16).

3.2. Extensive Tissue Distribution PK Study

3.2.1. Noncompartmental Analysis

The plasma concentration-time profile and PK of tumor-bearing mice was similar in profile compared to the 10 mg/kg PO non-tumor bearing group with a slightly higher Cmax and AUC (Table 1 and Suppl.Figure 8A). Concordantly, Cl/F was lower and Vd/F/kg higher for tumor-bearing mice. The half-life was similar at 108 min.

Distribution into all tissues appeared to be perfusion-rate limited (Table 3 and Suppl.Figure 8B–R). Samples for all tissues were above the 0.5 ng/mL LLQ until at least 360 min, except bone marrow which fell below the LLQ after 120 min. Tissue exposure and calculated partition coefficients (see Suppl.Figure 9A–B) showed most tissues experienced similar exposures to plasma with some exceptions. RBC, brain, spinal cord, skeletal muscle, and tumor all experienced lower exposure compared to plasma. Liver, kidney, small intestine, esophagus, and bone marrow all experienced greater exposure than plasma. Urine and fecal extraction were both low, approximating results from tumor free mice.

Table 3.

Extensive PK Study Tissue PK and Partition Coefficients

| Tissue | Cmax (ng/mL) | Tmax (min) | AUC0-t (μg/mL•min) | AUC0-∞ (μg/mL•min)b | Partition Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Plasma | 649 (266) | 15 | 30.7 (4.7) | 32.3 (4.7) | |

| RBC | 209 (84) | 15 | 9.7 (2.52) | 10.0 (2.52) | 0.311 (0.075) |

| Liver | 6,272 (3,194) | 15 | 310 (41) | 329 (41) | 10.2 (2.0) |

| Kidneys | 996 (387) | 15 | 56.3 (6.6) | 65.5 (6.6) | 2.03 (0.36) |

| Spleen | 519 (83) | 15 | 29.7 (8.7) | 31.2 (8.7) | 0.966 (0.305) |

| Lungs | 1,200 (64) | 15 | 49.2 (6.2) | 51.5 (6.2) | 1.60 (0.30) |

| Heart | 1,077 (825) | 15 | 37.3 (8.7) | 39.1 (8.7) | 1.21 (0.32) |

| Fat | 314 (170) | 15 | 24.3 (2.9) | 27.1 (2.9) | 0.841 (0.152) |

| Muscle | 274 (119) | 15 | 14.7 (2.8) | 15.3 (2.8) | 0.473 (0.111) |

| Brain | 204 (79) | 15 | 8.97 (1.45) | 9.8 (1.45) | 0.303 (0.063) |

| Tumor | 356 (88) | 15 | 20.2 (2.3) | 22.1 (2.3) | 0.685 (0.122) |

| Small Intestine | 9,933 (9,932) | 5 | 434 (75) | 453 (75) | 14.0 (3.1) |

| Draining Lymph Node | 945 (493) | 15 | 43.2 (7.0) | 47.1 (7.0) | 1.46 (0.31) |

| Non-draining Lymph Node | 946 (339) | 15 | 39.0 (4.5) | 42.1 (4.5) | 1.31 (0.24) |

| Esophagus | 17,812 (2,058) | 15 | 430.7 (103) | 436 (103) | 13.5 (3.8) |

| Spinal Cord | 179 (35) | 15 | 145 (22) | 9.83 (22) | 0.305 (0.064) |

| Thymus | 999 (336) | 15 | 32.6 (7.1) | 35.5 (7.1) | 1.10 (0.27) |

| Bone Marrowa | 2,341 (937) | 15 | 63.6 (10.0) | 85.4 (10.0) | 2.65 (0.50) |

Error is presented as SD for Cmax and SEM for AUC.

Bone marrow fellow below LLQ after 120 min, and reported AUC is from 0-120 min. The partition coefficients with a plasma AUC from the same time

All infinity extrapolated AUC portions are <1%, except for bone marrow which is 25.6%

Metabolite analysis revealed exposures for all metabolites were approximately three-fold higher than compared to tumor-free mice (Suppl.Figure 10), which was also reflected in higher metabolic ratios (Suppl.Table 9).

3.2.2. Compartmental Model

The addition of the uncoupled tumor compartment to the developed model (Suppl.Figure 11A) performed adequately with the model fitting the data well (Suppl.Table 10 and Suppl.Figure 11B). Underlying equations for the final model structure can be seen in Equations (17–22).

3.3. Plasma Protein Binding

Plasma protein binding was moderate, with the fraction unbound ranging from 16.6% to 19.8% (CV<12.4%) between 50 and 5,000 ng/mL, respectively (Suppl.Table 11).

4. DISCUSSION

The complex PK of BAY-1895344 in mice reported here appeared to be the product of two absorption-related processes that impacted systemic exposure. First was the observed greater than dose proportional increases in exposure, which were found to be due to saturation of first-pass metabolism. Second was the longer half-life in PO treated mice compared to IV treated mice. Fully understanding these two mechanisms, both of which were captured through compartmental modeling, can allow for a more thorough determination of the relationship of PK with future PD related studies as well as provide a mechanistic means of evaluating clinical translatability.

The first-pass saturation identified with BAY-1859344 in mice is a common phenomenon where metabolizing enzymes in the intestines or liver intended to limit systemic exposure of xenobiotics are overwhelmed, leading to dose-dependent bioavailability, as was also identified with another oral ATRi AZD6738 [16,19–21]. Saturation of this presystemic clearance process is particularly relevant for compounds with narrow therapeutic indices, such as chemotherapies, where more than proportional increases in dose can translate into supratherapeutic exposures that may increase the frequency or intensity of adverse events. The oral bioavailabilities of BAY-1895344 appeared to only modestly saturate between 1 and 10 mg/kg PO, with a 12% increase in bioavailability. Greater saturation appeared to occur between the 10 and 40 mg/kg PO, with more than a 250% increase in bioavailability. As BAY-1895344 is preclinically investigated for efficacy in numerous combinations, it is important to understand that reducing the dose, to allow for tolerable combinations, may result in a more than proportional decrease in exposure. Although not investigated, doses above 40 mg/kg PO likely produce even greater bioavailability. These observations were supported by analysis of the four identified metabolites, all of which had greater than dose proportional increases in exposure. These were reflected in metabolic ratios that decreased dose, indicating saturation.

Metabolite analysis identified both phase I and II metabolites and each of them showed signs of saturation below 10 mg/kg. Bioavailability appeared to be linear in this range indicating that these metabolic pathways did not quantitatively cause dose dependent bioavailability from first pass saturation at 1, 4 and 10 mg/kg PO but may have contributed at 40 mg/kg PO. Several reasons could explain why bioavailability was minimally impacted at 10 mg/kg and below when these four metabolic pathways appeared saturated. The most impactful is likely that additional unidentified metabolic pathways are more crucial to overall first pass clearance and compensate for the saturation of the pathways we monitored. These more impactful metabolites pathways likely also become saturated at doses greater than 10 mg/kg, resulting in observed greater bioavailability at 40 mg/kg. In rats, high doses of acetaminophen (paracetamol) were found to saturate intestinal glucuronidation that did not ultimately impact bioavailability or parent exposure due to an additional intestinal metabolic sulfonation pathway that was able to metabolize additional drug [22]. Future studies may further elucidate the metabolic fate of BAY-1895344, particularly in humans which may highlight any clinical relevancy of results.

There was marginal excretion of unaltered BAY-1895344 in the excreta of mice, indicating unabsorbed drug was not impactful to bioavailability. There was a minimal difference in the predicted bioavailability of 0.111 calculated from IV data and the 0.120 observed bioavailability in the lowest 1 mg/kg PO treated mice. This supports a minimal intestinal contribution to bioavailability particularly at lower doses and that saturation of hepatic metabolism is primarily responsible to the observed dose-dependent bioavailability. Confounding this is the metabolite PK identified with a higher MR for all four metabolites after PO dosing compared to IV treated mice and, additionally, each MR decreased with PO dose indicating saturation. This supports the evidence that intestinal metabolism is both present and saturable within the first-pass effect but perhaps of minimal impact to overall parent disposition. Overall, the assumptions used in deriving the intestinal contribution to overall metabolism are likely inadequate as there is evidence supporting both saturation of hepatic and intestinal first-pass metabolism. Outside of metabolic saturability, absorption rate-limited elimination was another notable finding. The half-life of PO treated mice was between 50 to 100% greater than the 91 min half-life after IV administration, with no discernable trend in dose. Absorption rate-limited elimination is likely to be an inherent physiochemical property of BAY-1895344 because it was delivered in solution, although other mechanisms can produce this phenomenon [23–25].

This identified absorption-rate limited elimination did not dull the rapid 15 min Cmax in PO treated mice and necessitated a model with dual absorption routes. A fast initial absorption rate accommodates the observed early Cmax, and a second slower rate that rate-limits the terminal elimination slope, which is normally defined by clearance and volume of distribution. This effect is relatively common in drugs delivered by either subcutaneous and intramuscular injections, due to slow release from a drug depot created at the injection site and it is a rarer for orally administered drugs [23,24]. There are several physiochemical or physiological mechanism which may explain this occurrence after oral administration in mice including, although not limited to, intestinal efflux transporters, drug coming out of solution in the intestine, and slow gastric motility [24].

Translation of this effect in humans would require the cumulative rates of tablet liberation, drug dissolution, and intestinal absorption to be slower than elimination. Identification of this effect would require clinical bioavailability studies to determine if the terminal slope of orally administered BAY-1895344 is defined by elimination or absorption and these studies are unlikely to be conducted unless there is reason to believe it affects safety or efficacy. And although this effect for BAY-1895344 in humans is unknown, it was mild in mice and the phenomenon is rarely observed in humans, making its overall clinical impact likely minimal [26].

These absorption processes are complicated by the observed saturable first-pass metabolism, which was incorporated into the rapid absorption compartment because saturation likely occurs during earlier moments of higher drug presentation. The location of saturation here is also supported by the fact that terminal half-lives would be dissimilar among PO doses if it affected the slower absorption rate. While the model accurately predicts observations, the true physiological behavior is likely a more complex process, where proximal absorption sites have a high absorption rate which incrementally decreases towards more distal sites in the GI tract. More complex PK models exist that represent this model including the advanced compartmental absorption and transit (ACAT) model [27]. ACAT models incorporate physiological movement of drug from the stomach through the large intestine via subdivided portions of the small intestine, each with mechanisms of absorption, efflux, metabolism, and transit. While these concepts are likely to represent true physiological processes, they require more densely collected PK data and can complicate interpretation.

The investigated PO doses of BAY-1895344 in mice of 1, 4, 10 and 40 mg/kg translate to approximately a dose of 5, 20 50 and 200 mg in humans [28]. Clinical PK data of single agent BAY-1895344 found dose proportional exposure and no evidence of saturable absorption among the entire investigated dose range of 5 to 80 mg administered twice daily [9]. They reported a single agent maximum tolerable dose (MTD) of 40 mg BID which is below the equivalent point of saturation observed with mouse PK data which did not experience significant saturation until the 200 mg human equivalent dose (40 mg/kg). Based on this alone, saturation of first-pass metabolism would not be expected in humans although future reports of BAY-1895344 PK should be more conclusive. Clinically the Cmax range was 178 to 3,255 ng/mL between 5 and 80 mg PO and largely overlaps with the Cmax in mice of 16 to 4,073 ng/mL from human equivalent 5 to 200 mg doses. The reported clinical AUC0-12 was 56.7 to 1,183 μg/mL∙min, which are slightly larger than the AUC0-∞ in mice of 1.94 to 307 μg/mL•min. This may indicate that the oral bioavailability in humans is higher than in mice although fully understanding inter-species differences in bioavailability may require identifying the specific enzymes responsible for the BAY-1895344 metabolism. Discrepancies in these enzyme expression between species, particularly both intestinal and hepatic, would provide a mechanism to explain differences in bioavailability and may explain saturation of first-pass. While saturable first-pass metabolism may not be clinically relevant it is still important to the interpretation of preclinical data such as a previously reported BAY-1895344 study in mice that reported efficacy using doses of 50 mg/kg, which is above the point of saturation identified here [10,11].

Tissue distribution and partition coefficients may allow evaluation of the relationship of PK with drug responses and differences among ATRi that may affect their clinical applications. Regarding responses of toxicity, clinically BAY-1895534 produced severe adverse events, specifically neutropenia and thrombocytopenia which may be related to bone marrow exposure [9]. Compared to AZD6738, BAY-1895344 has approximately 50% the bone marrow partitioning which may impact differences in hematological toxicities, although AZD6738 appears to have a qualitatively similar monotherapy toxicity profile [29,21]. BAY-1895344 had higher partitioning to several tissues compared to AZD6738, including brain and spinal cord (~10-fold higher than AZD6738) which supports the choice of BAY-1859344 when targeting CNS malignancies. BAY-1895344 had two-fold higher partitioning to the draining lymph node which may affect ATRi related immune responses. BAY-1895344 had four-fold higher partitioning to highly radiosensitive esophagus compared to AZD6738 which may limit the use of BAY-1895344 in the radiation treatment of head and neck or lung cancers [30]. There were minor differences in the partitioning of other analyzed tissues between these two ATRi and any differences in responses to these sites may be due to differences in potency.

The accurate determination of BAY-1895344 exposure at target and off-target sites reported here provides a direct means of defining a therapeutic index and comparing it with other drug class members. Dose-dependent bioavailability from first-pass saturation and absorption-rate limited elimination were important PK observations in mice, which may allow the correlation of PK with pharmacodynamic responses, including efficacy, toxicity, or immunological response. Differences identified here between BAY-1895344 and AZD6738 in the distribution to several tissues, including CNS and bone marrow, may inform their relative clinically utility.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in-part by the National Institutes of Health grants TL1TR001858, R50CA211241, R01CA236367, and P30CA047904. This project used the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center, Cancer Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics Facility (CPPF). BFK was also supported in-part by a fellowship from the American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education. This project is funded, in part, under a Grant with the Pennsylvania Department of Health. The Department specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations, or conclusions.

Abbreviations

- ATR

Ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related

- ATRi

Ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related inhibitor

- XRT

Radiation Therapy

- IR

Ionizing radiation

- LC-MS/MS

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- PK

Pharmacokinetics

- NCA

Noncompartmental Analysis

- IS

Internal Standard

- MRM

Multiple-reaction monitoring

- TIC

Total Ion Chromatogram

- IV

Intravenous

- PO

Oral

- AUC

Area Under the Curve

- Cmax

Maximum plasma concentration

- Tmax

Time of maximum plasma concentration

- F

Bioavailability

EQUATIONS

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Predicted Bioavailability

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

Non-Linear Compartmental PK Model with Saturable Absorption and Rate-Limiting Absorption

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

Non-Linear Compartmental PK Model with Saturable Absorption, Rate-Limiting Absorption, and Uncouple Tumor Compartment

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

| (22) |

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blackford AN, Jackson SP (2017) ATM, ATR, and DNA-PK: The Trinity at the Heart of the DNA Damage Response. Molecular cell 66 (6):801–817. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lecona E, Fernandez-Capetillo O (2018) Targeting ATR in cancer. Nature reviews Cancer 18 (9):586–595. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0034-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qiu Z, Oleinick NL, Zhang J (2018) ATR/CHK1 inhibitors and cancer therapy. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology 126 (3):450–464. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.09.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fokas E, Prevo R, Hammond EM, Brunner TB, McKenna WG, Muschel RJ (2014) Targeting ATR in DNA damage response and cancer therapeutics. Cancer Treat Rev 40 (1):109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnieh FM, Loadman PM, Falconer RA (2021) Progress towards a clinically-successful ATR inhibitor for cancer therapy. Current Research in Pharmacology and Drug Discovery 2:100017. doi: 10.1016/j.crphar.2021.100017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner JM, Kaufmann SH (2010) Prospects for the Use of ATR Inhibitors to Treat Cancer. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 3 (5):1311–1334. doi: 10.3390/ph3051311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown JS, Sundar R, Lopez J (2018) Combining DNA damaging therapeutics with immunotherapy: more haste, less speed. British journal of cancer 118 (3):312–324. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vendetti FP, Karukonda P, Clump DA, Teo T, Lalonde R, Nugent K, Ballew M, Kiesel BF, Beumer JH, Sarkar SN, Conrads TP, O’Connor MJ, Ferris RL, Tran PT, Delgoffe GM, Bakkenist CJ (2018) ATR kinase inhibitor AZD6738 potentiates CD8+ T cell-dependent antitumor activity following radiation. The Journal of clinical investigation 128 (9):3926–3940. doi: 10.1172/JCI96519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yap TA, Tan DS, Terbuch A, Caldwell R, Guo C, Goh BC, Heong V, Haris NRM, Bashir S, Drew Y, Hong DS, Meric-Bernstam F, Wilkinson G, Hreiki J, Wengner AM, Bladt F, Schlicker A, Ludwig M, Zhou Y, Liu L, Bordia S, Plummer R, Lagkadinou E, de Bono JS (2020) First-in-Human Trial of the Oral Ataxia Telangiectasia and Rad3-Related Inhibitor BAY 1895344 in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Cancer discovery. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wengner AM, Siemeister G, Lucking U, Lefranc J, Wortmann L, Lienau P, Bader B, Bomer U, Moosmayer D, Eberspacher U, Golfier S, Schatz CA, Baumgart SJ, Haendler B, Lejeune P, Schlicker A, von Nussbaum F, Brands M, Ziegelbauer K, Mumberg D (2020) The Novel ATR Inhibitor BAY 1895344 Is Efficacious as Monotherapy and Combined with DNA Damage-Inducing or Repair-Compromising Therapies in Preclinical Cancer Models. Molecular cancer therapeutics 19 (1):26–38. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-0019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luecking U, Wortmann L, Wengner AM, Lefranc J, Lienau P, Briem H, Siemeister G, Boemer U, Denner K, Schaefer M, Koppitz M, Eis K, Bartels F, Bader B, Bone W, Moosmayer D, Holton SJ, Eberspacher U, Grudzinska-Goebel J, Schatz C, Deeg G, Mumberg D, von Nussbaum F (2020) Damage Incorporated: Discovery of the Potent, Highly Selective, Orally Available ATR Inhibitor BAY 1895344 with Favorable Pharmacokinetic Properties and Promising Efficacy in Monotherapy and in Combination Treatments in Preclinical Tumor Models. Journal of medicinal chemistry. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Research USDoHaHSFaDACfDEa (2013) Guidance for Industry Bioanalytical Method Validation [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailer AJ (1988) Testing for the equality of area under the curves when using destructive measurement techniques. Journal of pharmacokinetics and biopharmaceutics 16 (3):303–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tucker GT (1981) Measurement of the renal clearance of drugs. British journal of clinical pharmacology 12 (6):761–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilkinson GR (1987) Clearance approaches in pharmacology. Pharmacological reviews 39 (1):1–47 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pond SM, Tozer TN (1984) First-pass elimination. Basic concepts and clinical consequences. Clinical pharmacokinetics 9 (1):1–25. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198409010-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Argenio DZS A; Wang X (2009) ADAPT 5 User’s Guide: Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Systems Analysis Software. Biomedical Simulations Resource. Los Angeles [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beumer JH, Parise RA, Kanterewicz B, Petkovich M, D’Argenio DZ, Hershberger PA (2012) A local effect of CYP24 inhibition on lung tumor xenograft exposure to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) is revealed using a novel LC-MS/MS assay. Steroids 77 (5):477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen DD, Kunze KL, Thummel KE (1997) Enzyme-catalyzed processes of first-pass hepatic and intestinal drug extraction. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 27 (2-3):99–127. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00039-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thummel KE (2007) Gut instincts: CYP3A4 and intestinal drug metabolism. J Clin Invest 117 (11):3173–3176. doi: 10.1172/JCI34007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kiesel BF, Guo J, Parise RA, Venkataramanan R, Clump DA, Bakkenist CJ, Beumer JH (2022) Dose-dependent bioavailability and tissue distribution of the ATR inhibitor AZD6738 (ceralasertib) in mice. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology 89 (2):231–242. doi: 10.1007/s00280-021-04388-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goon D, Klaassen CD (1990) Dose-dependent intestinal glucuronidation and sulfation of acetaminophen in the rat in situ. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 252 (1):201–207 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanez JA, Remsberg CM, Sayre CL, Forrest ML, Davies NM (2011) Flip-flop pharmacokinetics--delivering a reversal of disposition: challenges and opportunities during drug development. Therapeutic delivery 2 (5):643–672. doi: 10.4155/tde.11.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrison KL, Sahin S, Benet LZ (2015) Few Drugs Display Flip-Flop Pharmacokinetics and These Are Primarily Associated with Classes 3 and 4 of the BDDCS. J Pharm Sci 104 (9):3229–3235. doi: 10.1002/jps.24505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiesel BF, Parise RA, Guo J, Huryn DM, Johnston PA, Colombo R, Sen M, Grandis JR, Beumer JH, Eiseman JL (2016) Toxicity, pharmacokinetics and metabolism of a novel inhibitor of IL-6-induced STAT3 activation. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology 78 (6):1225–1235. doi: 10.1007/s00280-016-3181-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benet LZ, Broccatelli F, Oprea TI (2011) BDDCS applied to over 900 drugs. The AAPS journal 13 (4):519–547. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9290-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang W, Lee SL, Yu LX (2009) Mechanistic approaches to predicting oral drug absorption. The AAPS journal 11 (2):217–224. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9098-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration (2005) Guidance for Industry Estimating the Maximum Safe Starting Dose in Initial Clinical Trials for Therapeutics in Adult Healthy Volunteers. U.S.Department of Health and Human Services; Food and Drug Administration; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dillon MT, Espinasse A, Ellis S, Mohammed K, Grove LG, McLellan L, Smith SA, Ross G, Adeleke S, Woo K, Josephides E, Spicer JF, Forster MD, Harrington KJ (2017) Abstract CT084: A Phase I dose-escalation study of ATR inhibitor monotherapy with AZD6738 in advanced solid tumors (PATRIOT Part A). Cancer research 77 (13 Supplement):CT084–CT084. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.Am2017-ct084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trotti A (2000) Toxicity in head and neck cancer: a review of trends and issues. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics 47 (1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00558-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davies B, Morris T (1993) Physiological parameters in laboratory animals and humans. Pharmaceutical research 10 (7):1093–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.https://www.criver.com/sites/default/files/Technical%20Resources/Clinical%20Pathology%20Data%20for%20BALB_c%20Mouse%20Colonies%20in%20North%20America%20for%20January%202008%20-%20December%202012.pdf. Accessed 10/25/21

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.