Abstract

Background:

Although insomnia is highly prevalent in alcohol use disorders(AUD), its associations with the severity of alcohol use, pre-existing psychiatric comorbidities and psychosocial problems are understudied. The present study evaluates the interplay between these factors using a structural equation model (SEM).

Methods:

We assessed baseline cross-sectional data on patients with AUD (N=123) recruited to a placebo-controlled medication trial. Severity of alcohol use was measured by the Brief Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (B-MAST). Insomnia Severity Index was used to assess insomnia symptoms. The Hamilton scales for Depression and Anxiety, Short Index of Problems and Timeline Follow Back evaluated psychiatric symptoms, psychosocial consequences of drinking and level of alcohol consumption respectively. We used logistic regression to evaluate the association between insomnia and severity of alcohol use while controlling for covariates. We constructed a SEM with observed variables to delineate the effect of psychiatric symptoms, psychosocial factors and current alcohol use on the pathway between alcohol use severity and insomnia.

Results:

The sample was predominately male(83.9%), Black(54.6%) and employed(60.0%). About 45% of the participants reported moderate-severe insomnia.The association between insomnia and B-MAST attenuated after adjustment for demographics, psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial problems(OR[95% CI]=1.17(0.99–1.47). SEM findings demonstrated that B-MAST and insomnia were linked to psychiatric symptoms (95% Asymptotic-Confidence Interval (ACI): 0.015–0.159, p<0.05) but not to psychosocial problems or current alcohol use.

Conclusion:

Among treatment-seeking patients with AUD, psychiatric burden mediated the relationship between severity of alcohol use and insomnia. Clinicians should screen for underlying psychiatric disorders among treatment-seeking patients with AUD complaining of insomnia.

Keywords: Alcoholism, insomnia, sleep initiation and maintenance disorders, psychosocial factors, psychiatric symptoms, structural equation modelling

1. Introduction

Alcohol use disorder (AUD), as defined by American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force (2013), is a chronic disorder that incorporates criteria of alcohol dependence, alcohol abuse and craving for alcohol (American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force., 2013). It is characterized by compulsive behaviors to seek alcohol, an increased fixation on alcohol-related activities and an inability to regulate excess intake or withdrawal, and associated negative state of anxiety, irritability and other symptoms. AUD is associated with substantial medical (alcohol liver disease, transplantation, heart failure) and psychiatric co-morbidity (depression/anxiety disorders) and staggering direct and indirect health care costs (Bouchery et al., 2011).

Insomnia is prevalent among alcohol use disorder (AUD) patients (Caetano et al., 1998; Chakravorty et al., 2016; Escobar-Cordoba et al., 2009; Zhabenko et al., 2012). Psychosocial problems and suicide are complications of insomnia in AUD patients (Chakravorty et al., 2010; Chaudhary et al., 2015). Both insomnia and AUD often manifest with mood and anxiety symptoms and may also be comorbid with major depressive and anxiety disorders. Furthermore, insomnia during the premorbid phase increases the risk of subsequently developing AUD and mood and anxiety disorders(Ford and Kamerow, 1989). Thus, insomnia and AUD may be associated with psychosocial problems and psychiatric disorders such as depressive and anxiety disorders.

While prior studies have established a high prevalence of insomnia in alcohol dependent subjects, the relationship between insomnia and severity of AUD is complex. In one investigation involving veterans with heavy drinking, depressive symptoms predicted higher alcohol related problems. Insomnia was associated with greater quantity of alcohol consumption and more alcohol-related problems. However, the study was conducted in young veterans with likely post traumatic stress symptoms that may independently influence sleep architecture and alcohol intake (Miller et al., 2017a). In another longitudinal study, the quantity of alcohol consumption was associated with insomnia severity. On further analysis, severity of depressive symptoms mediated the relationship between insomnia severity and quantity of alcohol consumption in the last 90 days (Zhabenko et al., 2013). Finally, an investigation evaluating a Polish sample of patients in residential alcohol treatment showed that insomnia symptoms were associated with severity of alcohol use, quantity of alcohol consumption, and mental and physical symptoms (Zhabenko et al., 2012). In summary, insomnia-related symptoms are associated with the severity of alcohol use, levels of alcohol consumption, comorbid psychiatric symptoms, and potentially the psychosocial consequences of alcohol use. The nature and degree of these relationships have not been examined simultaneously in previous studies. Understanding these relationships may identify patients at risk of having insomnia in the context of AUD, determine the focus of targeted clinical interventions and help with risk stratification in terms of relapse.

In this study, we evaluated the relation among severity of alcohol use, current psychiatric symptom burden, psychosocial consequences of drinking and level of current alcohol use with insomnia by structural equation modeling.

2. Methods

2.1. Design.

The current study analyzed cross-sectional data from baseline assessments of subjects with AUD recruited for a randomized, placebo-controlled, double blind trial of quetiapine treatment (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier # NCT00674765).

2.2. Setting.

The study was conducted within the PennMedicine health system outpatient clinic. The Institutional Review Board of the Perelman School of Medicine approved the conduct of this study and all subjects provided written, informed consent.

2.3. Subjects.

Subject characteristics have been published in a prior study (Chaudhary et al., 2015). Heavy-drinking subjects were recruited into the study if they were 18–70 years old, met current DSM-IV diagnosis of alcohol dependence, drank to intoxication for ≥ 15 of the past 30 days, and consumed ≥ 10 standard drinks/drinking day (men) or ≥ 8 drinks/drinking day (women) over the past 30 days. Subjects were excluded from the study if they met past year dependence criteria for drugs (other than nicotine and cannabis), had a positive urine drug screen, had an unstable/serious medical illness, a psychiatric disorder such as bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia or regularly used a psychotrophic medication within last two weeks (with the exception of medications used for detoxification from alcohol or diphenhydramine used sparingly for sleep). The study included one week of screening followed by randomization into the clinical trial. All the baseline assessments were conducted at the treatment facility before randomization at the time of screening by a trained personnel. As the assessments were conducted before randomization, there was no influence of subsequent treatment on the current study. The final sample for the analysis consisted of 123 participants for whom complete data were available, as reported previously (Chaudhary et al., 2015).

2.4. Measures.

2.4.1. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I).

(FIRST, 2002) We used this structured interview instrument at baseline to screen for current (i.e., past year) alcohol and drug use disorders and to assess a lifetime diagnosis of mania or psychotic disorder using the criteria specified by the DSM-IV(Chaudhary et al., 2015).

2.4.2. Insomnia Severity Index (ISI).

(Bastien et al., 2001; Morin et al., 2011) This 7-item insomnia questionnaire evaluates insomnia using the following items: 1) Difficulty Falling Asleep (DFA), 2) Difficulty Staying Asleep (DSA), 3) Early Morning Awakening (EMA), 4) Satisfaction/dissatisfaction with current sleep pattern (Satisfaction), 5) How noticeable to others do you think your sleep problem is in terms of impairing the quality of your life (Noticeable), 6) How worried/distressed are you about your current sleep problem (Distressed), 7) “To what extent do you consider your sleep problem to interfere with your daily functioning (e.g., daytime fatigue, mood, ability to function at work/daily chores, concentration, memory, and mood, etc.) currently?” The individual responses were recorded on a Likert scale with a range from 0 to 4, from “none” to “very severe” (for items 1–3), from “very satisfied” to “very dissatisfied” for item 4, and “not at all” to “very much” (for items 5–7). The ISI yields a total score ranging from 0–28. Patients with an ISI score greater than 10 were deemed to have insomnia. This cutoff yielded a sensitivity of 86.1% and a specificity of 87.7% in a community sample of 959 individuals (Morin et al., 2011). Cronbach’s alpha for the ISI in this sample was 0.89.

2.4.3. Michigan Alcohol Screening Test - Brief Version (B-MAST)(Pokorny et al., 1972).

The B-MAST is a measure of lifetime severity of AUD based on self-perceived drinking patterns and drinking-alcohol related consequences(Cherpitel, 1997; Hearne et al., 2002; MacKenzie et al., 1996). This validated tool consists of 10 items extracted from the original 25-item measure. The score ranges from 0 to 10 (see Supplementary File 1). Higher B-MAST score indicated higher lifetime severity of alcohol dependence and is represented here as the severity of AUD.

2.4.4. Addiction Severity Index (ASI)

(Chaudhary et al., 2015; McLellan et al., 1992).This validated and commonly-used instrument assesses a subject’s substance-related problems across 7 domains and generates clinical profiles for the past month as well as over the individual’s lifetime. In this study, we used information from the following areas: general information (demographic characteristics), alcohol/drugs (alcohol/drugs treatment history), and psychiatric status (lifetime history).

2.4.5. Timeline follow-back interview (TLFB)

(Chaudhary et al., 2015; McLellan et al., 1992; Sobell et al., 1988) The TLFB interview uses a calendar format to evaluate the number of standard alcoholic drinks consumed per day during a pre-specified time period. We used this measure to assess drinking characteristics over the 90 days prior to entry into the study. Heavy drinking was classified in men and women as the consumption of ≥5 drinks per day and ≥4 drinks per day, respectively.(NIAAA, 2012) We used the TLFB data to generate the following alcohol consumption variables: drinks per day (quantity), drinks per drinking day, number of drinking days (frequency), and number of heavy drinking days. These data were used as proxy for current alcohol use.

2.4.6. Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS)

(Hamilton, 1967). This validated, interviewer-rated, 17-item measure evaluates the current overall severity of depressive symptoms. Each item is evaluated on a 5-point scale ranging from “0” (absent) to “4” (severe) and yields a global score of 0–54 (Zimmerman et al., 2013). Cronbach’s alpha for the HDRS in this sample was 0.84.

2.4.7. Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS)

(Hamilton, 1959). This validated, interviewer-rated, 14-item instrument evaluates the current global intensity of anxiety symptoms on a 5-point scale ranging from “0” (absent) to “4” (severe). It yields a global score of 0–56. The Cronbach’s alpha for the HARS in this sample was 0.81.

2.4.8. Short Index of Problems (SIP)

(Chaudhary et al., 2015; Miller et al., 1995). This validated 15-item measure is used to assess for the adverse psychosocial consequences of alcohol use in the last 3 months (such as, “whether drinking has gotten in way of personal growth” or “whether drinking damaged my social life”). Responses to each of the 15 questions are ordered on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3, which denote the frequency of occurrence, and are as follows: “never”, “once or a few times”, “once or twice a week”, “daily or almost daily.” The instrument evaluates these problems over the last 3 months (recent) and generates a global score, as well as 5 individual subscales that evaluate physical, social, interpersonal, intrapersonal and impulse control domains. We used the SIP-recent total score as a measure of psychosocial problems in our analysis(Chaudhary et al., 2015). The Cronbach’s alpha for the SIP in the current sample was 0.93.

2.4.9. Additional Covariates:

Sociodemographic variables in the analysis included, age (in years), gender(1=Male, 0=Female), race (analyzed by creating two dummy coded variables: 0= White, 1=Black; as well as 0= White, 1=Others; marital status (0= No, 1=Yes), education (Number of years), employment status (Categorical variable: 1= Full-time, 2=Part-time,3= Others ), living conditions (Nominal variable: 0= Alone, 1=With Family, 2=With Friends), and lifetime use of psychiatric medications(1=Yes, 0=,No).

2.5. Statistical Analysis.

Descriptive data involving demographic and clinical variables for the study population was presented as frequencies (percentages), mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range) as deemed appropriate. Linear regression analyses were used to independently evaluate the relationship between B-MAST and these demographic and clinical variables. Multivariable ordinal logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the relationships between B-MAST and insomnia categories (none, mild, moderate-severe). The covariates in this model included age, gender, race, marital status, education, employment status, living condition, depression without insomnia, anxiety without insomnia, psychosocial problems, and lifetime use of psychiatric medications. The covariates were selected based on prior knowledge of the associations between these variables and AUD and insomnia (Alvanzo et al., 2011; Chakravorty et al., 2013; Chaudhary et al., 2015; Grandner et al., 2016; Grant et al., 2004; Kaufmann et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2010; Levin et al., 2020; Whinnery et al., 2014; Witbrodt et al., 2014).We used the proportionality score assumption in order to appropriately interpret the odds ratio in this model.

We employed two separate principal component analyses (PCA) to generate factors that explained the maximal variance of current alcohol use and psychiatric symptoms. In the first PCA for current alcohol use, the input variables were drinks per day, number of drinking days, number of heavy drinking days, and drinks per heavy drinking days Among the two factors that had an eigenvalue > 1.0, we selected the first component with an eigenvalue of 2.63 and one that explained 65% of variance. In the second PCA for psychiatric symptoms, the input variables were the anxiety and depressive symptoms from the HDRS and HARS but the sleep items from these scales were excluded to minimize overlapping variance in these concepts. Only one factor had eigenvalue>1.0 and was selected as the representative of the variance of depressive and anxiety symptoms (eigenvalue 1.80, explained variance = 90%). Alcohol use and psychiatric symptoms were then employed as observed indicators for the Structural Equation Model (SEM).

Next, we evaluated a SEM model to examine whether current alcohol consumption (PCA factor for alcohol use), psychiatric symptoms (PCA factor for depression and anxiety) or psychosocial problems mediated the relationship between the severity of alcohol use and insomnia. Age, gender and employment from regression model were excluded from this model posthoc because the estimates between severity of alcohol use and insomnia did not change in our main analysis. Model fitness was tested using Chi-Square Goodness of fit test, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). We report the Bentler-Raykov squared correlation coefficient to measure the variance due to alcohol intensity because of the cross-sectional nature of the study and the assumption of a non-recursive model(Bentler and Raykov, 2000). We further tested the significance of association by deriving 95% asymmetric confidence intervals (ACI)(MacKinnon et al., 2007). We considered the association significant if the 95% ACI did not include zero.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics:

The average subject in this sample was middle-aged (mean=44.4 years), male (83.7%), self-identifed themselves as Black (54.9% were Black), employed (60.7%) and with a high school education (mean years of education was 13.3), Table 1. About 63.9% of them were living with family members, and 17.2% were currently married.

Table 1:

Demographic and clinical characteristics and their association with B-MAST total scores

| Variables | Total Sample (N=123) N(%) or Mean(SD) |

β (SE)* | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age | 44.39(9.58) | 0.04(0.02) | 0.04 |

| Male | 103 (83.74) | −0.10(0.59) | 0.87 |

| Married | 21(17.21) | ||

| Race | −1.20(0.38) | 0.002 | |

| White | 51(41.80) | ||

| Black | 67(54.92) | ||

| Others | 4(3.28) | ||

| Education in years | 13.29(3.10) | 0.19(0.07) | 0.16 |

| Professional Skills | 87(71.31) | 0.19(0.48) | 0.69 |

| Employment | 0.10(0.34) | 0.73 | |

| Full time | 74(60.66) | ||

| Part time | 28(22.95) | ||

| Other | 20(16.39) | ||

| Living Status | 0.04(0.09) | 0.66 | |

| Family | 78(63.93) | ||

| Friends | 14(11.48) | ||

| Alone | 30(24.59) | ||

| Current Alcohol use | |||

| B-MAST Total Score | 5.9(2.3) | ||

| Number of Drinking Days (past 90 days) | 75.8(15.37) | 0.01(0.005) | 0.48 |

| Drinks per Day (past 90 days) | 15.67(8.68) | −0.001(0.03) | 0.98 |

| Drinks per Drinking Day (past 90 days) | 18.33(8.36) | −0.01(0.03) | 0.78 |

| Number of Heavy Drinking Days (past 90 days) | 74.47(16.63) | 0.003(0.005) | 0.49 |

| Lifetime alcohol use (in years) | 19.21(10.99) | 0.03(0.02) | 0.19 |

| Psychiatric factors | |||

| Psychosocial problems in last 3 months | 23.86(11.58) | 0.11(0.02) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety without insomnia | 4.01(4.41) | 0.10(0.05) | 0.04 |

| Depression without insomnia | 7.16(6.56) | 0.09(0.03) | 0.01 |

| Severity of Psychiatric Problems¥¥ | 0.29(0.46) | 0.43(1.05) | 0.68 |

Footnotes:

Measures on the scale of 1–10 with 10 being most severe; HARS = Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HDRS = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; ASI = Addiction Severity Index Variables;

β = unstandardized beta estimates, SE = standard error; beta estimates should be interpreted with MAST score measured continuously as the outcome/dependent variable.

3.2. Clinical Characteristics:

a) Insomnia: Ninety two subjects (75%) complained of insomnia, Table 1. The mean ISI score for the total sample was 13.02; 29% had mild insomnia whereas 46% had moderate-severe insomnia. b) Psychiatric: On an average, they reported mild mood disturbance (mean HDRS score=7.2) but did not endorse clinically significant anxiety symptoms (mean HARS score=4.0), Table 1. c) Alcohol use: The B-MAST score (severity of AD) was 5.9. Their lifetime alcohol consumption was about 2 decades (mean=19.2)(Table 1). In the 90 days prior to their assessments, subjects drank on an average of 75.8 days and these drinking days were predominantly heavy drinking days (mean=74.5).

3.3. The relationship between B-MAST and Insomnia:

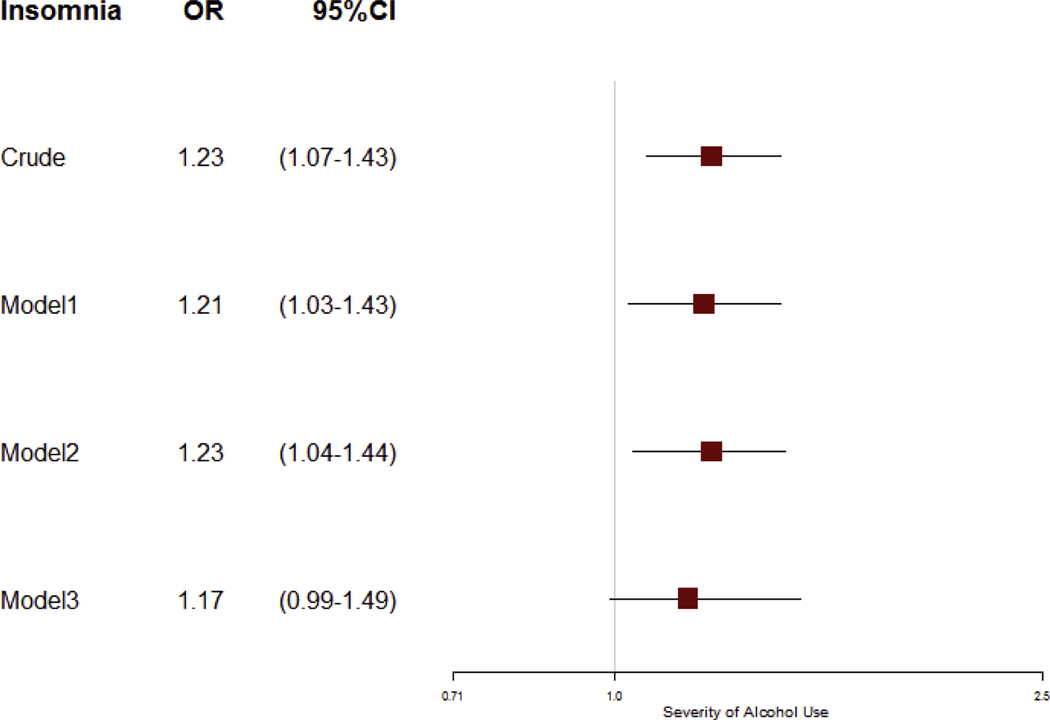

The B-MAST score was positively associated with the ISI score on bivariate analysis (R2=0.24, β (SE) = 0.59 (0.27), p=0.028). In the proportional odds model adjusted for demographics and psychiatric symptoms, for each one-point increase in the B-MAST score, the odds of moderate-severe insomnia were 1.23 times the odds of mild or no insomnia (Figure 1). However, these associations were no longer significant, once we adjusted for the total SIP score.

Figure 1:

The association between insomnia categories and the severity of drinking in alcohol use disorder

Footnotes: AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder; Model 1 adjusted for age, gender, race, employment, marital status, living condition, education; Model 2 adjusted for Model1 + depression without insomnia, anxiety without insomnia, lifetime use of psychiatric medications; Model 3 adjusted for Model2 + psychosocial problems; a Ordinal Logistic regression was conducted to determine odds of insomnia among problem drinkers vs non-problem drinkers/ per unit increase in intensity of alcoholism. The results are presented as proportional odds ratio (95% CI) as the proportional odds assumption was not violated at alpha=0.05.

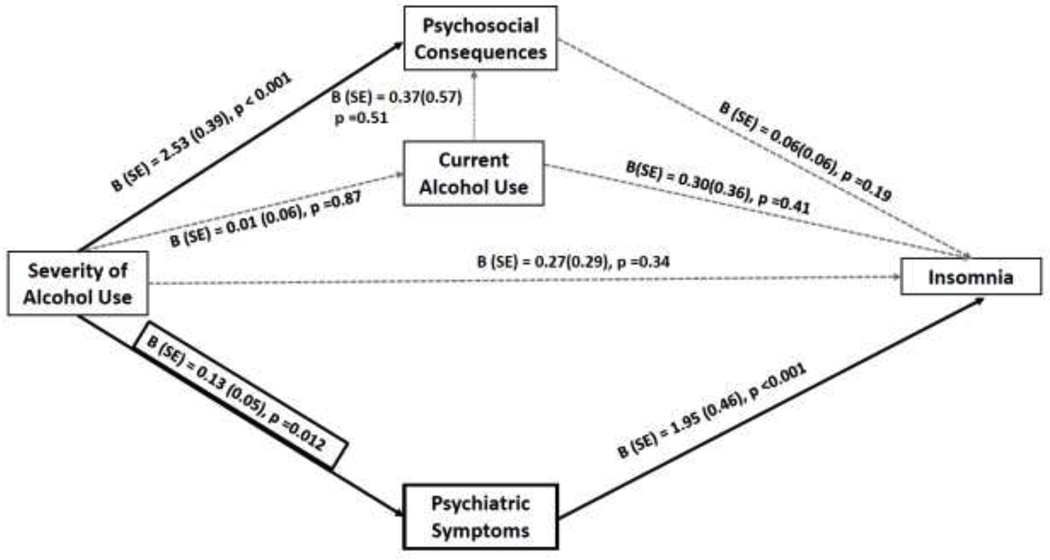

The structural equation model evaluated potential roles of other variables previously associated with insomnia and alcohol use severity. These variables included current alcohol use, psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial problems. We excluded employment as a covariate as it was not associated with insomnia (β=0.06, p=0.19). The model demonstrated that psychiatric symptoms significantly accounted for the association between severity of alcohol use and insomnia (Figure 2). The B-MAST score was associated with psychosocial consequences. However, psychosocial consequences were not associated with insomnia (p=0.19). The current alcohol use was not associated with severity of alcohol use or insomnia. This overall model was a good fit for the data (χ2(df)= 0.30(10), p=0.58) and one that was confirmed with other model fit indices (CFI =1.0, TLI = 1.1, RMSEA = 0.00 (90% CI RMSEA: 0.00–0.20).

Figure 2:

SEM Model of the Relationship between Severity of Alcoholism and Insomnia

Footnote: B(SE) = beta coefficients with standard error; AUD = Alcohol use Disorder. The arrows represent potential pathways between severity of alcohol use and insomnia via psychosocial consequences, current alcohol use and psychiatric symptoms. A thick black arrow indicates a statistically significant association between two variables while a grey dash arrow indicates a non-significant association between two variables.

The significance of mediation pathways were tested by MacKinnon’s asymmetric confidence interval (ACI).: a) Psychiatric symptoms: 95% asymmetric confidence interval (ACI): 0.015–0.159, p<0.05; b) Psychosocial consequences of drinking: 95% ACI: −0.076–0.130, p≥0.05 (the range included 0, thus the association was not significant); c) Current alcohol use: 95% ACI: −0. 025–0.029, p≥0.05

4. Discussion

We investigated the association between severity of alcohol use and insomnia in a treatment-seeking sample of patients with AUD. About three-quarters of the sample complained of insomnia, and approximately half of the sample met criteria for severe AUD. The B-MAST total score, which served as a measure of severity of alcohol use, was associated with a 1.23-times increased likelihood of having insomnia after adjusting for demographics and psychiatric problems. These associations were no longer significant after adjusting for psychosocial consequences of drinking. Finally, the structural equation model showed that their underlying psychiatric symptoms explained the association between the severity of alcohol use and insomnia symptoms. The alcohol use or their psychosocial consequences of alcohol use did not explain this association between the severity of alcohol use and insomnia symptoms.

Many factors influence the relationship between AUD and insomnia, e.g., co-occurring psychiatric comorbidity, level of alcohol consumption, and psychosocial consequences of drinking. It is difficult to disentangle these associations in a cross-sectional study. By modeling multiple relationships simultaneously, the structural equation framework estimates the covariance between the variables(Jöreskog, 1979). Such an approach relies on prior research for the direction of causation(Bullock et al., 1994; Jöreskog, 1979; Pentz and Chou, 1994). In this study, our structural equation model showed that in the presence of other covariates, severity of alcohol use was related to insomnia via their psychiatric symptoms. While severity of alcohol use was associated with the psychosocial consequences of drinking, psychosocial consequences were not associated with insomnia. Moreover, controlling for psychiatric symptoms, severity of alcohol use was not associated with insomnia symptoms.

Insomnia is a common complaint among those with psychiatric disorders and AUD. Prior studies have demonstrated an overlap between insomnia and psychiatric disorders. One twin study involving 1412 twin pairs showed a substantial overlap between insomnia and depressive and anxiety symptoms(Gehrman et al., 2013). Another twin study demonstrated a significant overlap between insomnia and psychiatric disorders (such as major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorders), but only a modest overlap between insomnia and alcohol use disorders(Lind et al., 2017). Some cross-sectional studies in treatment-seeking patients with AUD reported correlations between insomnia and psychiatric disorders(Chakravorty et al., 2013; Kolla et al., 2020). Thus, insomnia is closely related to psychiatric and alcohol use disorders.

The association between alcohol-related variables, psychiatric complaints, and insomnia have been evaluated in a limited number of studies. A recent study utilized mediation analyses on the data from young veterans who reported alcohol use(Miller et al., 2017a). The authors found that depressive and PTSD-related symptoms influenced insomnia symptoms. Insomnia symptoms, in turn, enhanced alcohol consumption and alcohol-related consequences. A drawback of this study was that it did not examine the influence of alcohol use severity, alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related consequences on insomnia. Another study demonstrated that insomnia and psychiatric symptoms worsen the alcohol-related consequences in heavy drinking young veterans(Miller et al., 2017b). A third study involving subjects with alcohol-dependence from a residential treatment facility showed that the quantity of alcohol consumption influences insomnia symptoms through its impact on depressive symptoms. However, this study did not account for the severity of the alcohol use disorder (Zhabenko et al., 2013). Our study supports these findings by determining that the current psychiatric symptoms could be an important driving factor in the relationship between severity of alcohol use disorder and insomnia. Unlike a previous study(Zhabenko et al., 2013), our study focused on both current alcohol consumption and symptoms of severity of alcohol use Our data indicate that insomnia symptoms are significantly associated with their current psychiatric symptom burden. When we accounted for other potential influences, symptoms of severity of alcohol use and insomnia were related through their association with psychiatric symptoms. There are several important implications of these findings on treatment. First, our results emphasize that individuals with higher severity of alcohol use disorder and insomnia require targeted interventions to treat any persistent psychiatric symptoms. A clinical trial of 124 treatment-seeking individuals with alcohol dependence in inpatient treatment program reported that the assessment of sleep regularity can be an important assessment or early marker for addressing mood disorders using targeted intervention of cognitive behavioral therapy of insomnia (CBT-I)(Brooks et al., 2020). While CBT-I is a viable approach for co-morbid insomnia among those with psychiatric diagnosis, the clinical implications of such targeted interventions in the presence of severity of AUD still needs to be studied. Second, insomnia symptoms could be a marker of underlying psychiatric symptoms and suicidal behavior in those drinking heavily(Chakravorty et al., 2014a; Kolla et al., 2020). The prioritization of psychiatric treatment may help reduce insomnia severity and could potentially improve alcohol use-related outcomes. The use of psychotropic medications have been shown to improve insomnia symptoms of individuals with alcohol dependence, (Chakravorty et al., 2014b; Le Bon et al., 2003) and individuals with major depressive disorder(Trivedi et al., 2013) Third, targeted treatment of insomnia has been shown to decrease suicidal behavior(Trockel et al., 2015). Given the high prevalence of insomnia in AUD patients, screening for sleep disturbances, especially in the context of ongoing psychiatric symptoms, should be an integral part of the management of these patients.

Our study population includes a greater percent of Blacks which is most likely a reflection of the ethnic makeup of the population from which study participants were recruited (Chakravorty et al., 2019; Kampman et al., 2013; Levin et al., 2020). Previous research has shown that race could be independently associated with both alcohol dependence and insomnia (Alvanzo et al., 2011; Grandner et al., 2016; Grant et al., 2004; Kaufmann et al., 2016; Whinnery et al., 2014; Witbrodt et al., 2014). We therefore accounted for race as a potential confounder in our analyses.

The results of this study should be interpreted cautiously as the relatively small sample size limited us from accounting for additional confounders. We cannot rule out the effect of unobserved measures in these relationships. The severity of alcohol use was screened using the brief MAST, although it has been found to be as effective as the longer version and the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test(Connor et al., 2007; Teitelbaum and Mullen, 2000). The cross-sectional design of this study does not allow us to examine temporal relations among variables. Future longitudinal studies could address this shortcoming. We also acknowledge that the Hamilton Scales of Depression and Anxiety measure current depressive and anxiety related symptoms but not underlying psychiatric problems. It is important to acknowledge that there is a possibility of unmeasured confounders, and measurement bias in observational studies, some factors that limit the feasibility of attesting to causal associations between variables (Ferrie et al., 2011; Martin and Winters, 1998; Midanik et al., 2007). While the classic criteria for inferring causality from a body of observational studies requires more validation studies (Hill, 1965), if such an association is indeed causal, our results could suggest that it is imperative to address underlying psychiatric disorders.

Despite these limitations, this study is one of the few studies to model the relationship between insomnia and psychiatric symptoms, psychosocial consequences of drinking and alcohol use severity in a treatment-seeking sample of individuals with AUD. Future research should prospectively investigate these relationships, using larger sample sizes, and with subjective and objective sleep data such as actigraphy or polysomnography.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Higher severity of alcohol use was associated with moderate to severe insomnia

Moderate to severe insomnia was associated with a higher severity of alcohol use

Psychiatric symptoms mediated the relationship between severity of alcohol use and insomnia

Current alcohol consumption indices were not linked to the severity of insomnia

Acknowledgment:

The content of this publication does not represent the views of the University of Pennsylvania, Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States Government, or any other institution.

Role of the funding source:

This work was supported by VA grants IK2CX000855 and CX001957 (S.C.) and NIH grants U34 DA045177; UG3 DA049694; U01 DK123813 (to K.M.K.)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

None of the authors reported any conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- Alvanzo AA, Storr CL, La Flair L, Green KM, Wagner FA, Crum RM, 2011. Race/ethnicity and sex differences in progression from drinking initiation to the development of alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 118(2–3), 375–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force., 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM, 2001. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med 2(4), 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchery EE, Harwood HJ, Sacks JJ, Simon CJ, Brewer RD, 2011. Economic costs of excessive alcohol consumption in the US, 2006. American journal of preventive medicine 41(5), 516–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks AT, Raju S, Barb JJ, Kazmi N, Chakravorty S, Krumlauf M, Wallen GR, 2020. Sleep Regularity Index in Patients with Alcohol Dependence: Daytime Napping and Mood Disorders as Correlates of Interest. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock HE, Harlow LL, Mulaik SA, 1994. Causation issues in structural equation modeling research. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 1(3), 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL, Greenfield TK, 1998. Prevalence, trends, and incidence of alcohol withdrawal symptoms: analysis of general population and clinical samples. Alcohol Health Res World 22(1), 73–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty S, Chaudhary NS, Brower KJ, 2016. Alcohol Dependence and Its Relationship With Insomnia and Other Sleep Disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40(11), 2271–2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty S, Grandner MA, Kranzler HR, Mavandadi S, Kling MA, Perlis ML, Oslin DW, 2013. Insomnia in alcohol dependence: predictors of symptoms in a sample of veterans referred from primary care. Am J Addict 22(3), 266–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty S, Grandner MA, Mavandadi S, Perlis ML, Sturgis EB, Oslin DW, 2014a. Suicidal ideation in veterans misusing alcohol: relationships with insomnia symptoms and sleep duration. Addict Behav 39(2), 399–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty S, Hanlon AL, Kuna ST, Ross RJ, Kampman KM, Witte LM, Perlis ML, Oslin DW, 2014b. The effects of quetiapine on sleep in recovering alcohol-dependent subjects: a pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 34(3), 350–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty S, Kuna ST, Zaharakis N, O’Brien CP, Kampman KM, Oslin D, 2010. Covariates of craving in actively drinking alcoholics. The American journal on addictions / American Academy of Psychiatrists in Alcoholism and Addictions 19(5), 450–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravorty S, Morales KH, Arnedt JT, Perlis ML, Oslin DW, Findley JC, Kranzler HR, 2019. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia in Alcohol-Dependent Veterans: A Randomized, Controlled Pilot Study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 43(6), 1244–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary NS, Kampman KM, Kranzler HR, Grandner MA, Debbarma S, Chakravorty S, 2015. Insomnia in alcohol dependent subjects is associated with greater psychosocial problem severity. Addict Behav 50, 165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel CJ, 1997. Brief screening instruments for alcoholism. Alcohol Health and Research World 21(4), 348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor JP, Grier M, Feeney GF, Young RM, 2007. The validity of the Brief Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (bMAST) as a problem drinking severity measure. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 68(5), 771–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Cordoba F, Avila-Cadavid JD, Cote-Menendez M, 2009. Complaints of insomnia in hospitalized alcoholics. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 31(3), 261–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrie JE, Kumari M, Salo P, Singh-Manoux A, Kivimaki M, 2011. Sleep epidemiology--a rapidly growing field. Int J Epidemiol 40(6), 1431–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FIRST MB, SPITZER RL, GIBBON M. & WILLIAMS JBW, 2002. Structured Cinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP), in: Biometrics Research, N.Y.S.P.I. (Ed.). New York. [Google Scholar]

- Ford DE, Kamerow DB, 1989. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? Jama 262(11), 1479–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrman P, Seelig AD, Jacobson IG, Boyko EJ, Hooper TI, Gackstetter GD, Ulmer CS, Smith TC, 2013. Predeployment Sleep Duration and Insomnia Symptoms as Risk Factors for New-Onset Mental Health Disorders Following Military Deployment. Sleep 36(7), 1009–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner MA, Williams NJ, Knutson KL, Roberts D, Jean-Louis G, 2016. Sleep disparity, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic position. Sleep Med 18, 7–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP, 2004. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend 74(3), 223–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M, 1959. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. The British journal of medical psychology 32(1), 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M, 1967. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. The British journal of social and clinical psychology 6(4), 278–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearne R, Connolly A, Sheehan J, 2002. Alcohol abuse: prevalence and detection in a general hospital. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 95(2), 84–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AB, 1965. The Environment and Disease: Association or Causation? Proc R Soc Med 58, 295–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, 1979. Statistical estimation of structural models in longitudinal-developmental investigations.

- Kampman KM, Pettinati HM, Lynch KG, Spratt K, Wierzbicki MR, O’Brien CP, 2013. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate for the treatment of comorbid cocaine and alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 133(1), 94–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann CN, Mojtabai R, Hock RS, Thorpe RJ Jr., Canham SL, Chen LY, Wennberg AM, Chen-Edinboro LP, Spira AP, 2016. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Insomnia Trajectories Among U.S. Older Adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 24(7), 575–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolla BP, Mansukhani MP, Biernacka J, Chakravorty S, Karpyak VM, 2020. Sleep disturbances in early alcohol recovery: Prevalence and associations with clinical characteristics and severity of alcohol consumption. Drug Alcohol Depend 206, 107655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bon O, Murphy JR, Staner L, Hoffmann G, Kormoss N, Kentos M, Dupont P, Lion K, Pelc I, Verbanck P, 2003. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy of trazodone in alcohol post-withdrawal syndrome: polysomnographic and clinical evaluations. J Clin Psychopharmacol 23(4), 377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MR, Chassin L, Mackinnon D, 2010. The effect of marriage on young adult heavy drinking and its mediators: results from two methods of adjusting for selection into marriage. Psychol Addict Behav 24(4), 712–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin FR, Mariani JJ, Pavlicova M, Choi CJ, Mahony AL, Brooks DJ, Bisaga A, Dakwar E, Carpenter KM, Naqvi N, Nunes EV, Kampman K, 2020. Extended release mixed amphetamine salts and topiramate for cocaine dependence: A randomized clinical replication trial with frequent users. Drug Alcohol Depend 206, 107700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind MJ, Hawn SE, Sheerin CM, Aggen SH, Kirkpatrick RM, Kendler KS, Amstadter AB, 2017. An examination of the etiologic overlap between the genetic and environmental influences on insomnia and common psychopathology. Depress Anxiety 34(5), 453–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie DM, Langa A, Brown TM, 1996. Identifying hazardous or harmful alcohol use in medical admissions: a comparison of audit, cage and brief mast. Alcohol and Alcoholism 31(6), 591–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM, 2007. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior research methods 39(3), 384–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Winters KC, 1998. Diagnosis and assessment of alcohol use disorders among adolescents. Alcohol Health Res World 22(2), 95–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M, 1992. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of substance abuse treatment 9(3), 199–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Greenfield TK, Bond J, 2007. Addiction sciences and its psychometrics: the measurement of alcohol-related problems. Addiction 102(11), 1701–1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, DiBello AM, Carey KB, Borsari B, Pedersen ER, 2017a. Insomnia severity as a mediator of the association between mental health symptoms and alcohol use in young adult veterans. Drug Alcohol Depend 177, 221–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, DiBello AM, Carey KB, Pedersen ER, 2017b. Insomnia moderates the association between alcohol use and consequences among young adult veterans. Addict Behav 75, 59–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R, 1995. The Drinker Inventory Of Consequences (DrInC): An Instrument for Assessing Adverse Consequences of Alcohol Abuse, in: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, N.I.A.A.A. (Ed.). National Instute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, N.I.A.A.A., Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, Ivers H, 2011. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep 34(5), 601–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentz MA, Chou CP, 1994. Measurement invariance in longitudinal clinical research assuming change from development and intervention. J Consult Clin Psychol 62(3), 450–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny AD, Miller BA, Kaplan HB, 1972. The brief MAST: A shortened version of the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test. American Journal of Psychiatry 129(3), 342–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Cancilla A, 1988. Reliability of a timeline method: assessing normal drinkers’ reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. Br J Addict 83(4), 393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelbaum L, Mullen B, 2000. The validity of the MAST in psychiatric settings: a meta-analytic integration. Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test. J Stud Alcohol 61(2), 254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi MH, Bandelow B, Demyttenaere K, Papakostas GI, Szamosi J, Earley W, Eriksson H, 2013. Evaluation of the effects of extended release quetiapine fumarate monotherapy on sleep disturbance in patients with major depressive disorder: a pooled analysis of four randomized acute studies. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 16(8), 1733–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trockel M, Karlin BE, Taylor CB, Brown GK, Manber R, 2015. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on suicidal ideation in veterans. Sleep 38(2), 259–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whinnery J, Jackson N, Rattanaumpawan P, Grandner MA, 2014. Short and long sleep duration associated with race/ethnicity, sociodemographics, and socioeconomic position. Sleep 37(3), 601–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witbrodt J, Mulia N, Zemore SE, Kerr WC, 2014. Racial/ethnic disparities in alcohol-related problems: differences by gender and level of heavy drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38(6), 1662–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhabenko N, Wojnar M, Brower KJ, 2012. Prevalence and correlates of insomnia in a polish sample of alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36(9), 1600–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhabenko O, Krentzman AR, Robinson EA, Brower KJ, 2013. A longitudinal study of drinking and depression as predictors of insomnia in alcohol-dependent individuals. Subst Use Misuse 48(7), 495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.