Abstract

Background

Vitamin B6 plays vital roles in numerous metabolic processes in the human body, such as nervous system development and functioning. It has been associated with some benefits in non‐randomised studies, such as higher Apgar scores, higher birthweights, and reduced incidence of pre‐eclampsia and preterm birth. Recent studies also suggest a protection against certain congenital malformations.

Objectives

To evaluate the clinical effects of vitamin B6 supplementation during pregnancy and/or labour.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group Trials Register (31 March 2015) and reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials comparing vitamin B6 administration in pregnancy and/or labour with: placebos, no supplementations, or supplements not containing vitamin B6.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and risk of bias, extracted data and checked them for accuracy. For this update, we assessed methodological quality of the included trials using risk of bias and the GRADE approach.

Main results

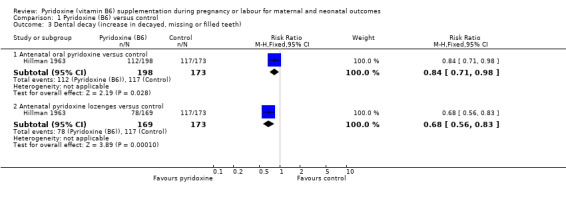

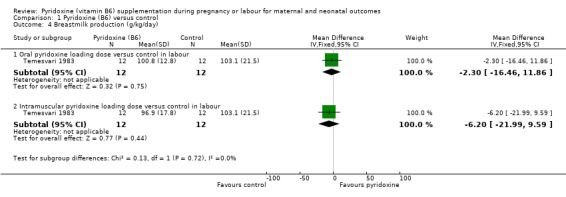

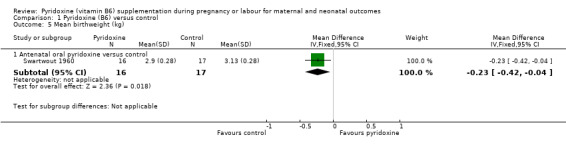

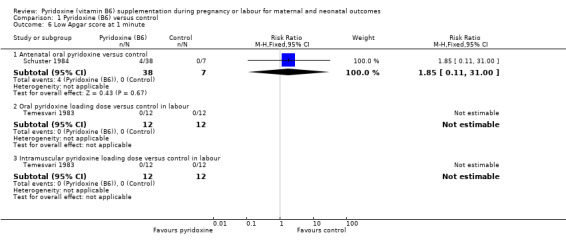

Four trials (1646 women) were included. The method of randomisation was unclear in all four trials and allocation concealment was reported in only one trial. Two trials used blinding of participants and outcomes. Vitamin B6 as oral capsules or lozenges resulted in decreased risk of dental decay in pregnant women (capsules: risk ratio (RR) 0.84; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.71 to 0.98; one trial, n = 371, low quality of evidence; lozenges: RR 0.68; 95% CI 0.56 to 0.83; one trial, n = 342, low quality of evidence). A small trial showed reduced mean birthweights with vitamin B6 supplementation (mean difference ‐0.23 kg; 95% CI ‐0.42 to ‐0.04; n = 33; one trial). We did not find any statistically significant differences in the risk of eclampsia (capsules: n = 1242; three trials; lozenges: n = 944; one trial), pre‐eclampsia (capsules n = 1197; two trials, low quality of evidence; lozenges: n = 944; one trial, low‐quality evidence) or low Apgar scores at one minute (oral pyridoxine: n = 45; one trial), between supplemented and non‐supplemented groups. No differences were found in Apgar scores at five minutes, or breastmilk production between controls and women receiving oral (n = 24; one trial) or intramuscular (n = 24; one trial) loading doses of pyridoxine at labour. Overall, the risk of bias was judged as unclear. The quality of the evidence using GRADE was low for both pre‐eclampsia and dental decay. The other primary outcomes, preterm birth before 37 weeks and low birthweight, were not reported in the included trials.

Authors' conclusions

There were few trials, reporting few clinical outcomes and mostly with unclear trial methodology and inadequate follow‐up. There is not enough evidence to detect clinical benefits of vitamin B6 supplementation in pregnancy and/or labour other than one trial suggesting protection against dental decay. Future trials assessing this and other outcomes such as orofacial clefts, cardiovascular malformations, neurological development, preterm birth, pre‐eclampsia and adverse events are required.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Infant, Newborn; Pregnancy; Dietary Supplements; Birth Weight; Dental Caries; Dental Caries/prevention & control; Eclampsia; Eclampsia/prevention & control; Labor, Obstetric; Pre‐Eclampsia; Pre‐Eclampsia/prevention & control; Pregnancy Outcome; Pyridoxine; Pyridoxine/administration & dosage; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Vitamin B Complex; Vitamin B Complex/administration & dosage

Plain language summary

Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) supplementation in pregnancy or labour for maternal and neonatal outcomes

This review could not provide evidence from randomised controlled trials that routine supplementation with vitamin B6 during pregnancy is of any benefit, other than one trial suggesting protection against dental decay. It may cause harm if too much is taken, as amounts well above the recommended daily allowance are associated with numbness and difficulty in walking.

Vitamin B6 is a water‐soluble vitamin which plays vital roles in numerous metabolic processes in the human body and helps with the development of the nervous system. Vitamin B6 is contained in many foods including meat, poultry, fish, vegetables, and bananas. It is thought that B6 may play a role in the prevention of pre‐eclampsia, where the mother’s blood pressure is high with large amounts of protein in the urine or other organ dysfunction, and in babies being born too early (preterm birth). Vitamin B6 may be helpful for reducing nausea in pregnancy. This review of four trials (involving 1646 pregnant women) assessed routine B6 supplementation during pregnancy with the aim of reducing the chances of pre‐eclampsia and preterm birth. Vitamin B6 as oral capsules or lozenges resulted in a decreased risk of dental decay in pregnant women in one trial. Lozenges had a greater effect, suggesting a local or topical effect of pyridoxine within the oral cavity. We did not find any clear differences in the risk of eclampsia or pre‐eclampsia (three trials and two trials, respectively, low quality evidence). The studies did not have enough data to be able to make any other useful assessments.

The included trials were conducted between 1960 and 1983 and did not include important newborn outcomes that have only recently been associated with vitamin B6, such as decreases in cardiovascular malformations and orofacial clefts. The trials began at different times during pregnancy, most had high rates of loss to follow‐up, and adverse effects of vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) use were not assessed.

Further research assessing outcomes such as orofacial clefts, cardiovascular malformations, neurological development, preterm birth, pre‐eclampsia and adverse events would be helpful.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Pyridoxine (B6) versus control.

| Pyridoxine (B6) versus control during pregnancy or labour for maternal and neonatal outcomes | ||||||

| Population: pregnant women, either during the prenatal period or during labour. Settings: USA, Hungary. Intervention: pyridoxine (B6) versus control. | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Pyridoxine (B6) versus control | |||||

| Eclampsia ‐ Antenatal oral pyridoxine versus control | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 1242 (3 studies) | See comment | The outcome was reported with no events. |

| Pre‐eclampsia ‐ Antenatal oral pyridoxine versus control | Study population | RR 1.71 (0.85 to 3.45) | 1197 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 20 per 1000 | 35 per 1000 (17 to 70) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 10 per 1000 | 17 per 1000 (9 to 35) | |||||

| Pre‐eclampsia ‐ Antenatal pyridoxine lozenges versus control | Study population | RR 1.43 (0.64 to 3.22) | 944 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | ||

| 21 per 1000 | 30 per 1000 (13 to 67) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 21 per 1000 | 30 per 1000 (13 to 68) | |||||

| Dental decay (increase in decayed, missing or filled teeth) ‐ Antenatal oral pyridoxine versus control | Study population | RR 0.84 (0.71 to 0.98) | 371 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | ||

| 676 per 1000 | 568 per 1000 (480 to 663) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 676 per 1000 | 568 per 1000 (480 to 662) | |||||

| Dental decay (increase in decayed, missing or filled teeth) ‐ Antenatal pyridoxine lozenges versus control | Study population | RR 0.68 (0.56 to 0.83) | 342 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | ||

| 676 per 1000 | 460 per 1000 (379 to 561) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 676 per 1000 | 460 per 1000 (379 to 561) | |||||

| Preterm birth (before 37 completed weeks of gestation) | Not estimable | Not estimable | 0 (no study) | See comment | None of the included studies reported this outcome. | |

| Low birthweight | Not estimable | Not estimable | 0 (no study) | See comment | None of the included studies reported this outcome. | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Most studies contributing data had design limitations. 2 Wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect. 3 One study with design limitations. 4 Estimate based on small sample size.

Background

Description of the condition

Vitamin B6 is a water‐soluble vitamin, naturally occurring in three forms ‐ pyridoxine, pyridoxal and pyridoxamine ‐ all of which are converted to the co‐enzyme pyridoxal phospate (PLP) (Whitney 2002). It plays a vital role in numerous metabolic processes in the human body including nervous system development and functioning. The role of vitamin B6 supplementation during pregnancy has been evaluated and there is some evidence supporting its use in reducing the severity of nausea during pregnancy (Matthews 2014; Wibowo 2012). Evidence from case‐control studies has also shown a possible decrease in risk of orofacial clefts (cleft lip and/or palate) in babies of periconceptional folate‐supplemented mothers consuming high dietary pyridoxine (Krapels 2004). Some decrease in cardiovascular malformations in the offspring of mothers treated with pyridoxine has also been found (Czeizel 2004). Earlier studies have reported higher birthweights with supplementation of two mg/day dose of vitamin B6 during pregnancy (Chang 1999), low serum and milk levels (Roepke 1979) and lower one‐minute Apgar scores in babies of mothers with low vitamin B6 intake. Pyridoxine may also have a role in prevention of pre‐eclampsia (de la Calle 2003) and preterm birth (Ronnenberg 2002). In animal experiments, vitamin B6 has been associated with a decreased incidence of tooth decay (Rapisarda 1981).

Description of the intervention

The recommended daily allowance (RDA) for pyridoxine for women during pregnancy is currently 1.9 mg/day, compared to 1.3 mg/day recommended for non‐pregnant females between the ages of 19 and 50 years (DRI 1998). This additional requirement for pyridoxine is based on estimated increased weight and metabolic needs of the mother and accumulation by the fetus and placenta (DRI 1998). However, although vitamin B6 indices decrease during pregnancy, especially during the third trimester, there is insufficient evidence to determine whether this is indicative of a deficient state with associated clinical implications, or a normal physiological response to pregnancy (DRI 1998). The tolerable upper intake limit in adults and in pregnancy is 100 mg/day (DRI 1998). Symptoms of toxicity include numbness, seizures and an inability to walk due to sensory nerve damage, which may be irreversible if high doses are consumed for prolonged periods of time (DRI 1998; Whitney 2002). The use of high doses in childbearing women may have possible detrimental effects on the developing nervous system of the fetus (Masino 2002) and possible reduction in breastmilk production (DRI 1998; Gupta 1990; Kang‐Yoon 1992), although this has not been consistently reported.

Deficiency of vitamin B6 presents with symptoms of nervous system dysfunction, such as irritability, depression, confusion, peripheral neuropathy, seizures, and can also manifest as microcytic anaemia (Chaney 2002). Vitamin B6 is present in moderate quantities in a variety of foods, but is destroyed by heating (Whitney 2002). Richest sources of B6 include meats, poultry, fish, potatoes, legumes such as peas and beans, and also bananas and liver, although it is suggested that several servings are necessary to meet recommended intakes (Truswell 1999; Whitney 2002). Substances interfering with vitamin B6 include alcohol and isoniazid (the anti‐tuberculosis drug), and possibly, and to a lesser extent, oral contraceptives (Chaney 2002; Truswell 1999; Var 2014). Thus, supplementation is required in people such as those with inadequate dietary consumption, malabsorption, alcoholism, or those taking isoniazid or other similarly interacting drugs. Vitamin B6 is absorbed well from the gastrointestinal tract, and is most commonly administered orally; alternate administration is via intravenous, intramuscular or subcutaneous injection (RxMed 2005).

How the intervention might work

In the human body, PLP activates several pathways in amino acid metabolism, including the formation of neurotransmitters (such as serotonin, norepinephrine, gamma‐amino butyric acid (GABA)); and also plays a role in heme (component of haemoglobin) synthesis (Chaney 2002; NDP 1990; Whitney 2002). PLP is also required for myelin (nerve sheath) formation (Chaney 2002). It thus aids the normal development of the central nervous system and also influences cognitive function (Ramakrishna 1999). Vitamin B6 also lowers the level of homocysteine which, when elevated, is considered a risk factor for cardiovascular disease (Austin 2004; Chaney 2002). There is some evidence suggesting a favourable influence of vitamin B6 on oxygen transportation among animal models, premature newborns and term newborns requiring intensive care; suggesting the possible impact of administering vitamin B6 during labour for postnatal adaptation disturbances of newborns (Boda 1981;Temesvari 1983).

Why it is important to do this review

Dietary vitamin B6 intake was estimated as inadequate in a very large proportion of female adults in the second US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES II) based on the RDA recommended at the time (Kant 1990). Numerous other studies in the United States around that time also documented vitamin B6 intakes below the RDA among pregnant women (NDP 1990). Furthermore, a recent epidemiological survey in the US population showed that plasma PLP concentrations of women of childbearing age were significantly lower than those of comparably aged men (Morris 2008). Based on the recently lowered RDA of 1.3 mg/day (DRI 1998; IFIC 1998), the results of third US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), suggest adequate dietary intakes among young women (mean daily intake 1.50 mg +/‐ 0.04 in females 20 to 39 years) (Alaimo 1998). However, the adequacy of a reduced RDA of vitamin B6 for young women ‐ from 1.6 mg/day to 1.3 mg/day ‐ has been questioned (Hansen 2001). In two recent small studies from Spain, women during pregnancy were not found to be meeting recommended B6 intakes (Arija 2004; Rocamora 2003). This review evaluated clinical outcomes in mothers and newborns, from trials in which pyridoxine was administered during pregnancy or labour, or both, for purposes other than treatment of nausea and vomiting.

Objectives

To evaluate the clinical effects of vitamin B6 supplementation during pregnancy on maternal and infant outcomes

To evaluate the clinical effects of vitamin B6 administration during labour on maternal and infant outcomes.

The impact of vitamin B6 on maternal nausea and vomiting was excluded as this is already covered in another Cochrane review by Matthews 2014.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled studies administering vitamin B6 during pregnancy and/or labour, for purposes other than treatment of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.

Types of participants

Pregnant women, either during the prenatal period or during labour. The impact of vitamin B6 on maternal nausea and vomiting was excluded

Types of interventions

Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) alone compared with a placebo, or no supplementation. Trials comparing vitamin B6 containing supplements versus the same supplement, but not containing vitamin B6, were also included.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Maternal outcomes

Pre‐eclampsia

Preterm birth (birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation)

Neonatal outcomes

Low birthweight defined as birthweight less than 2.5 kg

Secondary outcomes

Maternal outcomes

Eclampsia

Dental decay

Breastmilk production (as defined by authors)

Adverse events, as defined by authors such as: (a) sensory neuropathy, number of women reporting symptoms such as numbness, tingling sensation in fingers and toes, and inability to walk; (b) seizures

Neonatal outcomes

Mean birthweight in kg

Mean birth length in cm

Low Apgar (less than seven) at one minute (or as defined by authors)

Low Apgar (less than seven) at five minutes (or as defined by authors)

Cardiovascular malformations

Orofacial clefts

Long‐term developmental delay (as defined by authors)

Adverse events, as defined by authors, such as seizure

Admission to special care unit

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (31 March 2015).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of retrieved studies.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, seeThaver 2006. For this update, the following methods were used for assessing one new report (Coelingh Benninck 1979) that was identified as a result of the updated search.

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third review author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third review author. We entered data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked them for accuracy. When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we planned to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

Assessment of quality in included studies

For this update the quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach (Schunemann 2009) in order to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the main comparisons.

Eclampsia

Pre‐eclampsia

Dental decay

Preterm birth (birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation)

Low birthweight

GRADEprofiler (GRADE 2014) was used to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014) in order to create ’Summary of findings’ tables. A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes were produced using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Continuous data

We used the mean difference (MD) for outcomes measured in the same way between trials. In future updates, we may use the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

None of the included trials in this update was cluster randomised. For future updates, we will include cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials. We will adjust their sample sizes or standard errors using the methods described in the Handbook using an estimate of the intra‐cluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely. We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity or subgroup analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Cross‐over trials

Cross‐over trials were not an eligible study design for inclusion.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, levels of attrition were noted. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included, the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect will be explored by using sensitivity analysis. For all outcomes, analyses were carried out, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if an I² was greater than 30% and either a Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. Had we identified substantial heterogeneity (above 30%), we planned to explore it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates, if there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar. Had there been clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we planned to use random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. In future updates, if used, the random‐effects summary will be treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we will discuss the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful, we will not combine trials. If we use random‐effects analyses, the results will be presented as the average treatment effect with 95% CIs, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If we had identified substantial heterogeneity, we planned to investigate it using subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses. We planned to consider whether an overall summary was meaningful, and if it was, to use random‐effects analysis to produce it.

We carried out subgroup analyses according to the route of administration (oral, lozenges, intramuscular). We were unable to assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014) owing to the limited number of included trials and paucity of data.

In future updates, if data allow, we will assess subgroup differences by interaction tests available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We will report the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

For this update, we did not perform sensitivity analyses as studies were old and of low quality. In future updates, it data allow, we will carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality assessed by concealment of allocation, high attrition rates, or both, with poor‐quality studies being excluded from the analyses in order to assess whether this makes any difference to the overall result.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

For this update, one new report (Coelingh Benninck 1979) was identified by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Search Cordinator, which was excluded since it did not provide enough information for inclusion. Please see Characteristics of excluded studies.

Included studies

We included four trials (Hillman 1963; Schuster 1984; Swartwout 1960; Temesvari 1983) in this review.

Participants

The majority of the studies are quite old. The estimated number of pregnant women included in this review is 1646 (which includes all 1532 participants in Hillman 1963; 45 participants in Schuster 1984; 33 in Swartwout 1960; and 36 in Temesvari 1983). One trial (Hillman 1963) recruited women regardless of gestational age while two other trials recruited women who were less than or equal to 3.5 months (Swartwout 1960), and less than 5.5 months (Schuster 1984) pregnant. The fourth trial (Temesvari 1983) recruited women in the delivery room. Three trials (Schuster 1984; Swartwout 1960; Temesvari 1983) specified that only women who were free from complications were enrolled. Information regarding baseline dietary intake was available for one trial (Schuster 1984), in which 83% of women were found consuming less than the then current RDA of pyridoxine of 2.6 mg/day for pregnancy. Dietary intake was not controlled in Hillman 1963, although the authors reported that similar dietary instructions were given to intervention and control groups.

Interventions

One trial (Temesvari 1983) administered a loading dose of 100 mg of pyridoxine hydrochloricum either intramuscularly (group 1) or orally (group 2) to previously unsupplemented women in the delivery room, whose labour lasted two to 10 hours after the loading dose was administered (mean for group (1) was four hours; mean for group (2) was 5.5 hours). Loading doses were administered to induce changes in blood oxygen affinity levels in the mother and newborn and were based on findings from an earlier study by the same authors, which showed the effect of high pyridoxine doses on newborn blood oxygen affinity (Temesvari 1983). We analysed this trial separately from the other trials due to the difference in timing and duration of pyridoxine supplementation. One trial (Swartwout 1960) administered 25 mg pyridoxine‐HCl orally. In Hillman 1963, 20 mg pyridoxine was administered as part of a multivitamin supplement, or as three daily lozenges containing 6.67 mg of pyridoxine each. Schuster et al (Schuster 1984) administered 2.6, 5, 7.5, 10 and 20 mg to different groups (providing 2.1, 4.1, 6.2, 8.2, 12.3, 16.5 mg pyridoxine equivalents respectively). For this trial, we merged the various pyridoxine supplemented groups into one group (of 2.6 to 20 mg) and compared it to the control group. Further dosage categorisations may be possible in future updates of the review. We did not combine different routes of administration of pyridoxine (intramuscular, oral, lozenges) to avoid double‐counting the control groups of a single trial.

Outcomes

The author of one trial (Schuster 1984) provided additional information on trial methodology and outcomes. Among primary outcomes, eclampsia and pre‐eclampsia were reported in two (Hillman 1963; Schuster 1984) and were assumed as absent based on information presented in one trial (Swartwout 1960). Dental decay was reported in one trial (Hillman 1963). One trial reported the effect of pyridoxine supplementation on breastmilk production, although it was measured only on one particular day, by weighing the baby before and after a single breastfeeding episode, and thus may have limited accuracy (Temesvari 1983). Mean birthweight was reported by one trial, but the test of significance used to generate the P value was unclear (Swartwout 1960). Thus, caution is advised whilst interpreting mean birthweight, since the standard deviation we calculated was based on the assumption that the authors employed the conventional t‐test. Certain required clinical outcomes, although reported by two trials (Hillman 1963; Schuster 1984) could not be extracted due to incomplete information or varying format. Low Apgar score at one minute and five minutes were reported by two trials (Schuster 1984; Temesvari 1983) and one trial (Temesvari 1983) respectively. No included trial reported data for preterm birth, low birthweight, cardiovascular or orofacial malformations or adverse events in the neonate. One trial (Temesvari 1983) mentioned that mothers and babies followed 'uncomplicated courses at the nursery'. Details for each trial can be found in the Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

We have excluded two trials (Coelingh Benninck 1979; Lumeng 1976).The reasons for exclusion are described in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

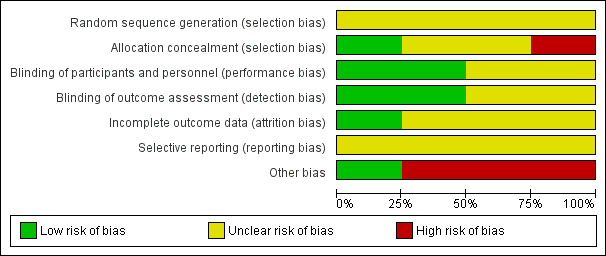

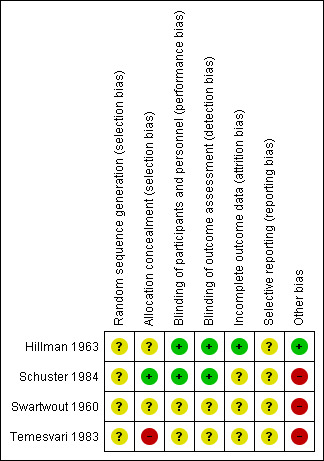

Risk of bias in included studies

Most of the studies were conducted over 30 to 55 years ago, and we found poor subjective and objective compliance with random allocation, adequate concealment and blinding. Figure 1 and Figure 2 provide a graphical summary of the results of risk of bias for the included studies. Methodological details for each trial can be found in the Characteristics of included studies.

1.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random‐sequence generation was not clearly specified in any of the included trials (Hillman 1963; Swartwout 1960; Temesvari 1983; Schuster 1984). Allocation was not clearly mentioned in two of the included trials (Hillman 1963; Swartwout 1960). Schuster 1984 specified that the drug manufacturers assigned numbered codes to different dosages of pyridoxine supplements while allocation was probably unconcealed in Temesvari 1983.

Blinding

One trial was triple‐blinded (Schuster 1984) while one trial was described as double‐blinded (Hillman 1963) and mentioned the use of placebos. In Hillman 1963 the dental examination of participants was performed by dentists who were involved in the trial, but dental ratings assigned to participants from the clinical records and from radiological bite‐films were conducted by dentists not involved in the trial. Blinding was not clear in Temesvari 1983 and Swartwout 1960.

Incomplete outcome data

This was adequate in one trial (Hillman 1963). Schuster 1984; Swartwout 1960 and Temesvari 1983 did not provide any information on loss to follow‐up and reasons.

Selective reporting

Studies provided insufficient information, which limited us from making any judgment.

Other potential sources of bias

Schuster 1984 and Temesvari 1983 selected participants who volunteered to take part in the study; while in Swartwout 1960 all the participants were black and only those were included who were willing to be hospitalised for 24 hours during the course of study. All three trials were considered to have a high risk of 'Other' bias. Hillman 1963 was considered to have a low risk of bias for this domain.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparison: Pyridoxine versus control

Primary outcomes

Maternal outcomes

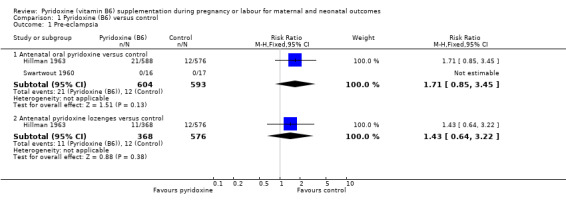

(1) Pre‐eclampsia or toxemia

We did not find any statistically significant differences in the risk of pre‐eclampsia among women receiving antenatal oral pyridoxine, or antenatal pyridoxine lozenges, compared to women not receiving pyridoxine (antenatal oral pyridoxine: risk ratio (RR) 1.71; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.85 to 3.45; n = 1197; two trials) and (antenatal pyridoxine lozenges: RR 1.43; 95% CI 0.64 to 3.22; n = 944; one trial) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pyridoxine (B6) versus control, Outcome 1 Pre‐eclampsia.

(2) Preterm birth

None of the included studies reported this outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Maternal outcomes

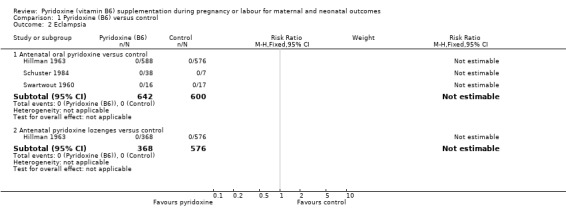

(1) Eclampsia

There were no events in either the control or pyridoxine supplemented arm (antenatal oral pyridoxine: n = 1242; three trials) and (antenatal pyridoxine lozenges: n = 944; one trial) (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pyridoxine (B6) versus control, Outcome 2 Eclampsia.

(2) Dental decay

Dental decay was defined as an increase in decayed, missing and filled teeth (Hillman 1963). We found a statistically significant decrease in the risk of dental decay with antenatal oral pyridoxine supplementation (RR 0.84; 95% CI 0.71 to 0.98; n = 371; one trial) and also with antenatal pyridoxine lozenges (RR 0.68; 95% CI 0.56 to 0.83; n = 342; one trial), compared to control groups (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pyridoxine (B6) versus control, Outcome 3 Dental decay (increase in decayed, missing or filled teeth).

(3) Breastmilk production

Breastmilk production was evaluated in one trial by measuring the amount of breastmilk suckled by newborn (weight gain of newborn after each suckling) on day five of life in g/kg/day (Temesvari 1983). We did not find any statistically significant differences in mean breastmilk production (g/kg/day), between women administered a loading dose of oral pyridoxine at the time of labour versus no pyridoxine (mean difference (MD) ‐2.30; 95% CI ‐16.46 to 11.86; n = 24; one trial), or between those administered a loading dose of intramuscular pyridoxine at the time of labour versus no pyridoxine (MD ‐6.20; 95% CI ‐21.99 to 9.59; n = 24; one trial), although CIs are very wide (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pyridoxine (B6) versus control, Outcome 4 Breastmilk production (g/kg/day).

(4) Adverse events

Only one trial (Swartwout 1960) reported that no significant neuropathy occurred in any participant of their trial (n = 33).

Neonatal outcomes

(1) Mean birthweight (kg)

We found a statistically significantly lower mean birthweight in the group supplemented with oral pyridoxine antenatally (MD ‐0.23 kg; 95% CI ‐0.42 to ‐0.04; n = 33; one trial) (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pyridoxine (B6) versus control, Outcome 5 Mean birthweight (kg).

(2) Low Apgar score (less than seven) at one minute

We did not find any statistically significant differences in risk of low Apgar score at one minute between women supplemented with antenatal oral pyridoxine and women not supplemented (RR 1.85; 95% CI 0.11 to 31.00; n = 45; one trial), although CIs were very wide. No babies in either arm of mothers receiving loading doses of intramuscular pyridoxine versus no pyridoxine (n = 24; one trial), or loading doses of oral pyridoxine (n = 24; one trial) versus no pyridoxine at the time of labour were found to have Apgar scores of less than seven at one minute (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pyridoxine (B6) versus control, Outcome 6 Low Apgar score at 1 minute.

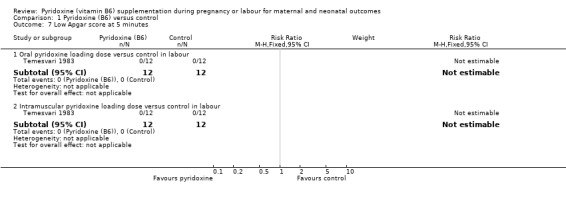

(3) Low Apgar score (less than seven) at five minutes

No babies of mothers receiving either oral loading dose of pyridoxine, intramuscular loading dose, or no supplementation at labour, were found to have Apgar scores of less than seven at five minutes (oral pyridoxine: n = 24; one trial) and (intramuscular pyridoxine: n = 24; one trial) (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Pyridoxine (B6) versus control, Outcome 7 Low Apgar score at 5 minutes.

None of the included studies reported low birthweight, mean birth length, cardiovascular malformations, orofacial clefts, long‐term developmental delay, and admission to special care unit.

Heterogeneity and subgroup analysis

We were unable to conduct planned subgroup analysis or assess the presence of heterogeneity owing to the limited number of included trials and paucity of data. Such analyses may be possible in future updates of the review.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Oral pyridoxine supplementation was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the risk of dental decay in pregnant women (16%; 95% confidence interval (CI) 2 to 29%), although CIs were wide. We found pyridoxine lozenges to be associated with a greater decrease in the risk of dental decay (32%; 95% CI 17 to 44%), although this finding was also associated with wide CIs. These results need further assessment in well‐designed studies in different settings. However, the data suggest a primarily local or topical effect of pyridoxine within the oral cavity, and in vitro experiments suggest pyridoxine and its analogues inhibit various activities of bacteria (Streptococcus mutans) implicated in dental decay (Thaniyavarn 1982). The risk of low birthweight could not be assessed, as no included trial reported these data. The results of a small trial show that vitamin B6 was associated with a reduction in mean birthweight by 0.23 kg (CI 0.04 to 0.42 kg). However, there is some uncertainty regarding this outcome since the standard deviation calculated by us was based on the assumption that a t‐test was used. Moreover, only 33 participants contributed data. Thus, this finding also requires corroboration from well‐designed trials of large sample sizes.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The data were not sufficient to detect any statistically significant differences in the risk of eclampsia, pre‐eclampsia, breastmilk production or low Apgar scores among women receiving pyridoxine supplementation or control groups. The included trials were conducted between 1960 to 1983, and thus did not include important neonatal outcomes, which have only recently been associated with vitamin B6, such as cardiovascular malformations and orofacial clefts. In addition, adverse effects of pyridoxine use were not assessed.

Quality of the evidence

There were only four included trials data on important clinical outcomes were seldom reported. All included trials, except one, were double or triple blinded; however, allocation concealment and the method of randomisation were deemed adequate in only one trial. There were high rates of loss to follow‐up in most trials, which may also have been a potential source of bias in the results. The overall risk of bias is unclear. The quality of the evidence using GRADE was low for pre‐eclampsia, and dental decay. The reasons for downgrading the quality of the evidence were because of most studies contributing data had design limitations, wide confidence intervals crossing the line of no effect and small sample sizes.

Potential biases in the review process

We undertook a systematic, thorough search of the literature to identify all studies meeting the inclusion criteria and we are confident that the included trials met the set criteria. Study selection and data extraction were carried out in duplicate and independently and we reached consensus by discussing any discrepancies.

A protocol was published for this review. All the analyses were specified a priori, with the exception of a post hoc analysis of the different cut‐off values for biochemistry markers.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Most of the existing data on vitamin B6 supplementation during pregnancy focuses on the effectiveness of B‐6 supplementation for reducing pregnancy‐related nausea and vomiting (Matthews 2014). Our review findings are in concordance with existing reviews highlighting the need for additional studies to confirm positive effects of vitamin B6 supplementation on maternal and infant outcomes (Dror 2012).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is at present not enough evidence to show any important clinical benefit of providing vitamin B6 supplementation in pregnancy. Although there may be some protection against tooth decay, more studies are required to confirm this finding.

Implications for research.

Future well‐designed trials evaluating neonatal outcomes such as cardiovascular malformations, orofacial clefts and long‐term neurological development, as well as maternal outcomes such as preterm birth and pre‐eclampsia are warranted. The risk of adverse events should also be evaluated.

Feedback

Hughes, December 2002

Summary

Please mention the possibility of side‐effects with pyridoxine, in particular peripheral neuropathy, and suggest what would be a safe dose if it were used.

[Summary of comment received from Richard Hughes, December 2002]

Reply

Potential adverse effects, and recommended upper limits of dose, are discussed in the Background section of the updated review.

[Reply from the review team, December 2005]

Contributors

Richard Hughes

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 March 2016 | Amended | Added external source of support for Erika Ota (the Evidence and Programme Guidance Unit, Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, World Health Organization). |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 1997 Review first published: Issue 2, 1997

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 31 March 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Review updated. One new trial identified and excluded (Coelingh Benninck 1979). |

| 31 March 2015 | New search has been performed | Search updated. Methods updated and 'Summary of findings' table added. The title in this update has changed from: Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) supplementation in pregnancy, to; Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) supplementation during pregnancy or labour for maternal and neonatal outcomes. |

| 16 February 2009 | Amended | Author contact details edited |

| 20 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 30 December 2005 | New search has been performed | Search updated. Included studies: included four new trials: Hillman 1963; Swartwout 1960; Temesvari 1983; Schuster 1984. (Swartwout 1960 and Temesvari 1983 had been excluded in the original review as clinical outcomes were not considered extractable.) |

| 30 December 2005 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Background: updated. Outcomes: added maternal outcomes: eclampsia, pre‐eclampsia, preterm birth, breastmilk production and adverse events. Added neonatal outcomes: mean birthweight and length, low birthweight, Apgar scores at one and five minutes, cardiovascular malformations, orofacial clefts, long‐term developmental delay, adverse events and admission to special care unit. Methods of review: updated. Changed from odds ratio to relative risk. Added planned subgroup analyses. Results: updated. |

Acknowledgements

The original protocol and review were undertaken by Kassam Mahomed and A Metin Gülmezoglu and the previous review was completed by the late Durrane Thave. Their contribution is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Rebecca Smyth, Editorial Assistant at the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group, for help in preparing the updated protocol.

Previous data extractions and write‐up were completed by Mohammed Ammad Saeed.

We would also like to acknowledge Erika Ota for her assistance with the GRADE tables. Erika Ota's work was financially supported by the UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization. The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication. Erika's work was also partially funded by The Evidence and Programme Guidance Unit, Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, World Health Organization.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by two peers (an editor and referee who is external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Pyridoxine (B6) versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pre‐eclampsia | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Antenatal oral pyridoxine versus control | 2 | 1197 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.71 [0.85, 3.45] |

| 1.2 Antenatal pyridoxine lozenges versus control | 1 | 944 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.43 [0.64, 3.22] |

| 2 Eclampsia | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Antenatal oral pyridoxine versus control | 3 | 1242 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.2 Antenatal pyridoxine lozenges versus control | 1 | 944 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Dental decay (increase in decayed, missing or filled teeth) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Antenatal oral pyridoxine versus control | 1 | 371 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.71, 0.98] |

| 3.2 Antenatal pyridoxine lozenges versus control | 1 | 342 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.56, 0.83] |

| 4 Breastmilk production (g/kg/day) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Oral pyridoxine loading dose versus control in labour | 1 | 24 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.30 [‐16.46, 11.86] |

| 4.2 Intramuscular pyridoxine loading dose versus control in labour | 1 | 24 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐6.20 [‐21.99, 9.59] |

| 5 Mean birthweight (kg) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Antenatal oral pyridoxine versus control | 1 | 33 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.23 [‐0.42, ‐0.04] |

| 6 Low Apgar score at 1 minute | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Antenatal oral pyridoxine versus control | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.85 [0.11, 31.00] |

| 6.2 Oral pyridoxine loading dose versus control in labour | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6.3 Intramuscular pyridoxine loading dose versus control in labour | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Low Apgar score at 5 minutes | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Oral pyridoxine loading dose versus control in labour | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7.2 Intramuscular pyridoxine loading dose versus control in labour | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Hillman 1963.

| Methods | Method of randomisation and allocation concealment unclear. Described as double‐blinded. Follow‐up adequate (540 randomised and followed). | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 1532. Eligibility criteria: pregnant women attending clinics and at any parity or gestational age. | |

| Interventions | 3 groups: 1) multivitamin capsule* + 3 placebo lozenges daily (173)**. 2) multivitamin capsule* containing 20 mg pyridoxine + 3 placebo lozenges daily (198). 3) multivitamin capsule* + 3 pyridoxine lozenges daily (6.67 mg of pyridoxine in each) (169). Duration: until delivery. | |

| Outcomes | Clinical outcomes: 1) dental decay (increase in number of decayed‐missing‐filled teeth) assessed at start of trial and 6 weeks' postpartum. 2) eclampsia. 3) pre‐eclampsia. | |

| Notes | Location: Brooklyn, New York, USA.

Setting: antenatal clinic. Year of trial: not reported. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "A total of 540 women,....were assigned at random to one of three study groups". Comment: authors do not specify the method used for randomisation. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: not specified in the text. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Employing the “double blind” procedure, the DMF rating was assessed by clinical (probe and mirror) and roentgenologic (bitewing film) examination..". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Employing the “double blind” procedure, the DMF rating was assessed by clinical (probe and mirror) and roentgenologic (bitewing film) examination,....all the DMF ratings were calculated from the recorded observations and films by a single dental consultant, who did not directly perform any of the examinations". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Comment: authors have not provided any trial flow chart; however, they reported the findings for all the participants randomised. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: insufficient information to decide about selective reporting. |

| Other bias | Low risk | None. |

Schuster 1984.

| Methods | Method of randomisation adequate and secure (?block randomisation). Allocation concealment adequate. Triple‐blinded. (Author provided further information.) Follow‐up inadequate (196 randomised, 22 followed at delivery). | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 196 at start of trial, 46 at 30 weeks, 22 at delivery. Eligibility criteria: good health at first visit; < 22 weeks pregnant; > or equal to 17 years; not taking B6 supplements or medications containing B6; no long history of oral contraceptive use. | |

| Interventions | 7 groups (data provided by author for 45 participants): 1) no pyridoxine (7). 2) 2.6 mg (10). 3) 5 mg (6). 4) 7.5 mg (7). 5) 10 mg (4). 6) 15 mg (6). 7) 20 mg (5). Per day of pyridoxine‐HCl. | |

| Outcomes | Clinical outcomes: 1) eclampsia. 2) low Apgar score at 1 minute. | |

| Notes | Location: Florida, USA.

Setting: Maternal and Infant Care clinics for low‐income women.

Year of study: 1981‐1983. For analysis, we merged the various pyridoxine supplemented groups into one group (of 2.6 to 20 mg) and compared it to the control group. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "In this double‐blind study subjects were randomly assigned a coded vitamin B‐6 supplement containing 0,2.6, 5, 7.5, 10, 15 or 20 mg of PN‐HC1 at their initial prenatal clinic visit". Comment: authors do not specify the method used for randomisation. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "In this double‐blind study subjects were randomly assigned a coded vitamin B‐6 supplement containing 0,2.6, 5, 7.5, 10, 15 or 20 mg of PN‐HC1 at their initial prenatal clinic visit". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "In this double‐blind study subjects were randomly assigned a coded vitamin B‐6 supplement containing 0,2.6, 5, 7.5, 10, 15 or 20 mg of PN‐HC1 at their initial prenatal clinic visit". |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "In this double‐blind study subjects were randomly assigned a coded vitamin B‐6 supplement containing 0,2.6, 5, 7.5, 10, 15 or 20 mg of PN‐HC1 at their initial prenatal clinic visit". |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: not specified. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: insufficient information to decide about selective reporting. |

| Other bias | High risk | Comment: all the participants volunteered to take the supplements. |

Swartwout 1960.

| Methods | Method of randomisation and allocation concealment unclear. Described as double‐blinded. Follow‐up inadequate (?58 randomised, 33 followed). | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 33. Eligibility criteria: no evidence of disease or complications of pregnancy and not > 3 and a half months pregnant. | |

| Interventions | 2 groups: 1) 25 mg pyridoxine‐HCl (16). 2) placebo of identical appearance (17). | |

| Outcomes | Clinical outcomes: 1) mean birthweight. 2) stated that no serious prenatal or delivery complications occurred. 3) adverse event: sensory neuropathy in mothers. | |

| Notes | Location: Louisiana, USA. Setting: Charity Hospital. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Patients were assigned by a standard double‐blind procedure to one of the two study groups". Comment: authors have not specified the method of randomisation. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Patients were assigned by a standard double‐blind procedure to one of the two study groups". Comment: authors have not specified the method of randomisation. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Quote: "Patients were assigned by a standard double‐blind procedure to one of the two study groups". Comment: authors have not specified the method of randomisation. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Quote: "Patients were assigned by a standard double‐blind procedure to one of the two study groups". Comment: authors have not specified the method of randomisation. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: authors have not provided any trial flow chart; however, they reported the reasons for loss to follow‐up. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: insufficient information to decide about selective reporting. |

| Other bias | High risk | Comments: all the participants were black and only those who were willing to get admitted to the hospital for 24 hours once a month were included. |

Temesvari 1983.

| Methods | Method of randomisation and allocation concealment unclear. Most likely not blinded. Follow‐up adequate (36 randomised and followed). | |

| Participants | Number of participants: 36. Eligibility criteria: not pyridoxine supplemented; uncomplicated pregnancies; presenting to delivery room. | |

| Interventions | 3 groups: 1) 100 mg pyridoxinum hydrochloricum intramuscularly (12). 2) same as above, but orally (12). 3) none (12). Duration: 1 loading dose only. Labour was completed in 2‐10 hours (mean for group 1): 4 hours; mean for group 2): 5.5 hours) after loading dose was administered. | |

| Outcomes | Clinical outcomes: 1) breastmilk output measured as amount of milk suckled on day 5 (g/kg/day). 2) low Apgar score at 1 minute. 3) low Apgar score at 5 minutes. | |

| Notes | Location: Szeged, Hungary.

Setting: delivery ward.

Year: December 1980 to January 1981. Administration of Vitamin B6 during labour. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Random allocation was done into three groups". Comment: authors do not clarify the method for randomisation. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Not specified. Comment: probably not done. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: not specified. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: not specified. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Comment: not specified. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: insufficient information to decide about selective reporting. |

| Other bias | High risk | The participants volunteered to participate in the study. |

*Multivitamin‐mineral capsule contained: 6000 international units vitamin A; 400 units vitamin D; 2 mg riboflavin; 15 mg niacin; 5 mg pantothenic acid; 1.5 mg thiamine; 100 mg ascorbic acid; 0.2 mg sodium iodide; 1 micro‐g B12; 0.25 mg folate; 15 mg ferrous iron. **number of participants in parenthesis. *** not defined in text of trial.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Coelingh Benninck 1979 | We have been unable to locate the full text, and this is the only report, an abstract, we have. It does not provide enough information for assessment for inclusion. |

| Lumeng 1976 | Reasons for excluding this study were: (1) there was no control group (i.e. a non‐vitamin B6 supplemented group) and (2) only biochemical outcomes were studied. 33 antenatal women were randomly assigned to multivitamin supplements containing 2.5, 4 or 10 mg pyridoxine. |

Differences between protocol and review

We have divided the outcomes into primary and secondary.

We were unable to conduct planned subgroup analysis or assess the presence of heterogeneity owing to limited number of included trials and paucity of data. Such analyses may be possible in future updates of the review.

The title in this update has changed from: Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) supplementation in pregnancy, to; Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) supplementation during pregnancy or labour for maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Contributions of authors

For this update, the data extraction, entry and write‐up were undertaken by Rehana A Salam and Nadeem Zuberi. Technical input was provided by Professor Zulfiqar Bhutta.

Sources of support

Internal sources

The Aga Khan University, Pakistan.

External sources

UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), Department of Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization, Switzerland.

The Evidence and Programme Guidance Unit, Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, World Health Organization, Switzerland.

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Hillman 1963 {published data only}

- Hillman R, Cabaud P, Nilsson D, Arpin P, Tufano R. Pyridoxine supplementation during pregnancy. Clinical and laboratory observations. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1963;12:427‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman RW, Cabaud PG, Schenone RA. The effects of pyridoxine supplements on the dental caries experience of pregnant women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1962;10:512‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schuster 1984 {published data only}

- Schuster K, Bailey LB, Mahan CS. Effect of maternal pyridoxine‐HCl supplementation on the vitamin B‐6 status of mother and infant and on pregnancy outcome. Journal of Nutrition 1984;114:977‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Swartwout 1960 {published data only}

- Swartwout JR, Unglaub WG, Smith RC. Vitamin B6, serum lipids and placental arteriolar lesions in human pregnancy. A preliminary report. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1960;8:434‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Temesvari 1983 {published data only}

- Temesvari P, Szilagyi I, Eck E, Boda D. Effects of an antenatal load of pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) on the blood oxygen affinity and prolactin levels in newborn infants and their mothers. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica 1983;72:525‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Coelingh Benninck 1979 {published data only}

- Coelingh Bennink HJT, Stolte LAM, Riet HG, Hart H, Haspels AA. A decrease in the incidence of gestational diabetes by prophylactic treatment with vitamin B6 [abstract]. 9th World Congress of Gynecology and Obstetrics; 1979 Oct 26‐31; Tokyo, Japan. 1979:269.

Lumeng 1976 {published data only}

- Lumeng L, Cleary RE, Wagner R, Yu P‐L, Li T‐K. Adequacy of Vitamin B6 supplementation during pregnancy: a prospective study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1976;29:1376‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Alaimo 1998

- Alaimo K, McDowell MA, Briefel RR, Bischof AM, Caughman CR, Loria CM, et al. Dietary intake of vitamins, minerals, and fiber of persons ages 2 months and over in the United States: third national health and nutrition examination survey, phase 1, 1988‐91. Advance Data: Vital and Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; Center for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Health Statistics, 1994:1‐28. [Google Scholar]

Arija 2004

- Arija V, Cuco G, Vila J, Iranzo R, Fernandez‐Ballart J. Food consumption, dietary habits and nutritional status of the population of Resus: follow‐up from preconception throughout pregnancy and after birth [Consumo, hábitos alimentarios y estado nutricional de la población de Reus en la etapa preconcepcional, el embarazo y el posparto]. Medical Clinics (Barcelona) 2004;123(1):5‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Austin 2004

- Austin RC, Lentz SR, Werstuck GH. Role of hyperhomocysteinemia in endothelial dysfunction and atherothrombotic disease. Cell Death and Differentiation 2004;11(Suppl 1):S56‐S64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boda 1981

- Boda D, Temesvári P, Eck, E. Influence of pyridoxine on the oxygen transport function of blood in the neonatal period in clinical and experimental conditions. Padiatrie und Padologie 1981;17(2):149‐155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chaney 2002

- Chaney SG. Chapter 27: Principles of nutrition II: Micronutrients. Section 27.6: Energy releasing water soluble vitamins. In: Delvin TM editor(s). Textbook of Biochemistry with Clinical Correlations. 5th Edition. Wiley‐Liss (a Wiley & Sons, Inc. publication), 2002:1148‐53. [Google Scholar]

Chang 1999

- Chang SJ. Adequacy of maternal pyridoxine supplementation during pregnancy in relation to the vitamin B6 status and growth of neonates at birth. Journal of Nutritional Science Vitaminology (Tokyo) 1999;45(4):449‐58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Czeizel 2004

- Czeizel AE, Puho E, Banhidy F, Acs N. Oral pyridoxine during pregnancy: potential protective effect for cardiovascular malformations. Drugs 2004;5(5):259‐69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

de la Calle 2003

- Calle M, Usandizaga R, Sancha M, Magdaleno F, Herranz A, Cabrillo E. Homocysteine, folica acid and B‐group vitamins in obstetrics and gynaecology. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2003;107:125‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

DRI 1998

- Food, Nutrition Board. Institute of Medicine. Chapter 7: Vitamin B6. Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. A Report of the Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate, other B Vitamins, and Choline and Subcommittee on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients. National Academy Press, 1998:150‐95. [Google Scholar]

Dror 2012

- Dror DK, Allen LH. Interventions with vitamins B6, B12 and C in pregnancy. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 2012;26(S1):55‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

GRADE 2014 [Computer program]

- McMaster University. GRADEpro. [Computer program on www.gradepro.org]. Version 2015. McMaster University, 2014.

Gupta 1990

- Gupta T, Sharma R. An antilactogenic effect of pyridoxine. Journal of Indian Medical Association 1990;88(12):336‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hansen 2001

- Hansen CM, Shultz TD, Kwak H‐K, Memon HS, Leklem JE. Assessment of vitamin B‐6 status in young women consuming a controlled diet containing four levels of vitamin B‐6 provides and estimated average requirement and recommended dietary allowance. Journal of Nutrition 2001;131:1777‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

IFIC 1998

- International Food Information Council. Nutrient requirements get a makeover the evolution of the recommended dietary allowances. http://www.ific.org/foodinsight/1998/so/rdafi598.cfm (accessed December 2005).

Kang‐Yoon 1992

- Kang‐Yoon SA, Kirksey A, Giacoia G, Kerstin W. Vitamin B‐6 status of breast‐fed neonates: influence of pyridoxine supplementation on mothers and neonates. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1992;56:548‐58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kant 1990

- Kant AK, Block G. Dietary vitamin B‐6 intake and food sources in the US population: NHANES II; 1976‐1980. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1990;54(4):707‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Krapels 2004

- Krapels IP, Rooij IA, Ocke MC, Cleef BA, Kuijpers‐Jagtman AM, Steegers‐Theunissen RP. Maternal dietary B vitamin intake, other than folate, and the association with orofacial cleft in the offspring. European Journal of Nutrition 2004;43(1):7‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Masino 2002

- Masino SA, Kahle JS. Vitamin B6 therapy during childbearing years: cause for caution?. Nutritional Neuroscience 2002;5(4):241‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Matthews 2014

- Matthews A, Haas DM, O'Mathúna DP, Dowswell T, Doyle M. Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007575.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Morris 2008

- Morris MS, Picciano MF, Jacques PF, Selhub J. Plasma pyridoxal 5′‐phosphate in the US population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2004. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008;87(5):1446‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NDP 1990

- Committee on Nutritional Status During Pregnancy and Lactation. Food and Nutrition Board. Institute of Medicine. Water‐soluble vitamins. Nutrition During P: Part I: Weight Gain, Part II: Nutrient Supplements. National Academy of Sciences, 1990:351‐79. [Google Scholar]

Ramakrishna 1999

- Ramakrishna T. Vitamins and brain development. Physiological Research 1999;48(3):175‐87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rapisarda 1981

- Rapisarda E, Longo A. Effects of zinc and vitamin B6 in experimental caries in rats. Minerva Stomatologica 1981;30(4):317‐20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2014 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

Rocamora 2003

- Irles Rocamora JA, Iglesias Bravo EM, Aviles Mejias S, Bernal Lopez E, Valle Galindo PB, Moriones Lopez L, et al. Nutritional value of the diet in healthy pregnant women. Results of a nutrition survey of pregnant women [Valor nutricional de la dieta en embarazadas sanas: Resultados de una encuesta dietética en gestantes]. Nutricion Hospitalaria 2003;18(5):248‐52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Roepke 1979

- Roepke JL, Kirksey A. Vitamin B6 nutriture during pregnancy and lactation. I. Vitamin B6 intake, levels of the vitamin in biological fluids, and condition of the infant at birth. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1979;32(11):2249‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ronnenberg 2002

- Ronnenberg AG, Goldman MB, Chen D, Aitken IW, Willett WC, Selhub J, et al. Preconception homocysteine and B vitamin status and birth outcomes in Chinese women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2002;76(6):1385‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RxMed 2005

- Vitamin B6: general monograph. http://www.rxmed.com/b.main/b2.pharmaceutical/b2.1.monographs/CPS‐%20Monographs/CPS‐%20(General%20Monographs‐%20V)/VITAMIN%20B6.html (accessed December 23, 2005).

Schunemann 2009

- Schunemann HJ. GRADE: from grading the evidence to developing recommendations. A description of the system and a proposal regarding the transferability of the results of clinical research to clinical practice [GRADE: Von der Evidenz zur Empfehlung. Beschreibung des Systems und Losungsbeitrag zur Ubertragbarkeit von Studienergebnissen]. Zeitschrift fur Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualitat im Gesundheitswesen 2009;103(6):391‐400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thaniyavarn 1982

- Thaniyavarn S, Taylor KG, Singh S, Doyle RJ. Pyridine analogs inhibit the glucosyltransferase of streptococcus mutans. Infection and Immunity 1982;37(3):1101‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Truswell 1999

- Truswell AS. Vitamins. ABC of Nutrition. 3rd Edition. London: BMJ Books, 1999:57‐64. [Google Scholar]

Var 2014

- Var C, Keller S, Tung R, Freeland D, Bazzano AN. Supplementation with vitamin B6 reduces side effects in Cambodian women using oral contraception. Nutrients 2014;6(9):3353‐62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Whitney 2002

- Whitney EN, Rolfes SR. The water soluble vitamins: B vitamins and Vitamin C. Understanding Nutrition. 9th Edition. Wadsworth. Thomson Learning, 2002:306‐46. [Google Scholar]

Wibowo 2012

- Wibowo N, Yuditiya P, Akihiko S, Antonio F, Victor T, Saptawati B. Vitamin B 6 supplementation in pregnant women with nausea and vomiting. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 2012;116(3):206‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

CDSR 1997

- Mahomed K, Gulmezoglu AM. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) supplementation in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1997, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000179] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thaver 2006

- Thaver D, Saeed MA, Bhutta ZA. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) supplementation in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000179.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]