Abstract

Therapeutic antibodies are an important tool in the arsenal against coronavirus infection. However, most antibodies developed early in the pandemic have lost most or all efficacy against newly emergent strains of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), particularly those of the Omicron lineage. Here, we report the identification of a panel of vaccinee-derived antibodies that have broad-spectrum neutralization activity. Structural and biochemical characterization of the three broadest-spectrum antibodies reveal complementary footprints and differing requirements for avidity to overcome variant-associated mutations in their binding footprints. In the K18 mouse model of infection, these three antibodies exhibit protective efficacy against BA.1 and BA.2 infection. This study highlights the resilience and vulnerabilities of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and provides road maps for further development of broad-spectrum therapeutics.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, coronavirus, Omicron, antibodies, cryo-EM, neutralization, bivalent antibody binding, COVID-19

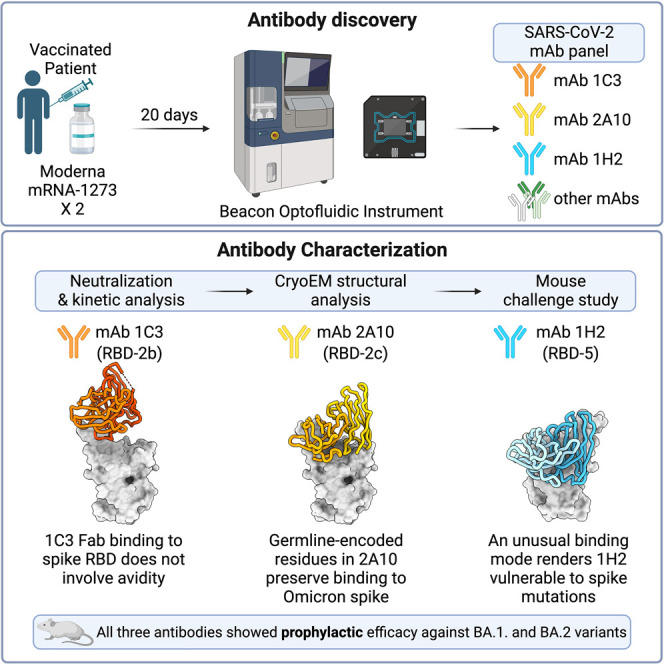

Graphical abstract

Hastie et al. identify antibodies from a vaccinated subject that show broad activity against multiple Omicron lineages. Structural analysis of these mAbs illustrates different binding modes and differential dependencies on IgG avidity. These mAbs also exhibit protective efficacy in a mouse model of BA.1 and BA.2 infection.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was isolated in late 2019 and has since caused over 500 million cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), resulting in 6.3 million deaths. The SARS-CoV-2 surface glycoprotein, spike, mediates cell entry by engaging the cell-surface receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) via its receptor-binding domain (RBD). The spike S2 subunit then drives fusion between virus and host cell membranes. Spike, particularly the RBD, is the primary target of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2.1

Since SARS-CoV-2 was first identified, a succession of variants of concern (VOCs) have emerged and spread around the globe.2 Some VOCs caused large regional outbreaks, such as the Beta variant in South Africa3 and the Gamma variant in Brazil,4 whereas others, such as Alpha,5 Delta,6 and Omicron7 became globally dominant. These VOCs drove waves of infection, and variants that reached worldwide prevalence replaced the previous VOC as the primary circulating strain.

Each VOC has mutations throughout the SARS-CoV-2 genome, but those in the spike are of particular concern because they can increase virus transmission as well as affect vaccine and antibody therapy efficacy. Mutations in the spike protein of VOCs localize to several key residues in the RBD, and some recurrent mutations appear in divergent VOCs (Figure 1 ). For example, the VOCs Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Gamma (P.1), and Mu (B.1.621) each bear the N501Y mutation, which is implicated in the increased transmission associated with these VOCs relative to the original Wuhan strain.8 Beta, Gamma, and Mu each carry the E484K mutation, and Beta and Gamma also have substitutions at K417. Mutations at E484 and K417 have been implicated in immune escape of these VOCs.4 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 The Delta variant, which in mid-2021 quickly surpassed all others as the dominant lineage, has T478K and L452R substitutions that also contribute to immune evasion and virus spread.6 , 9 , 10

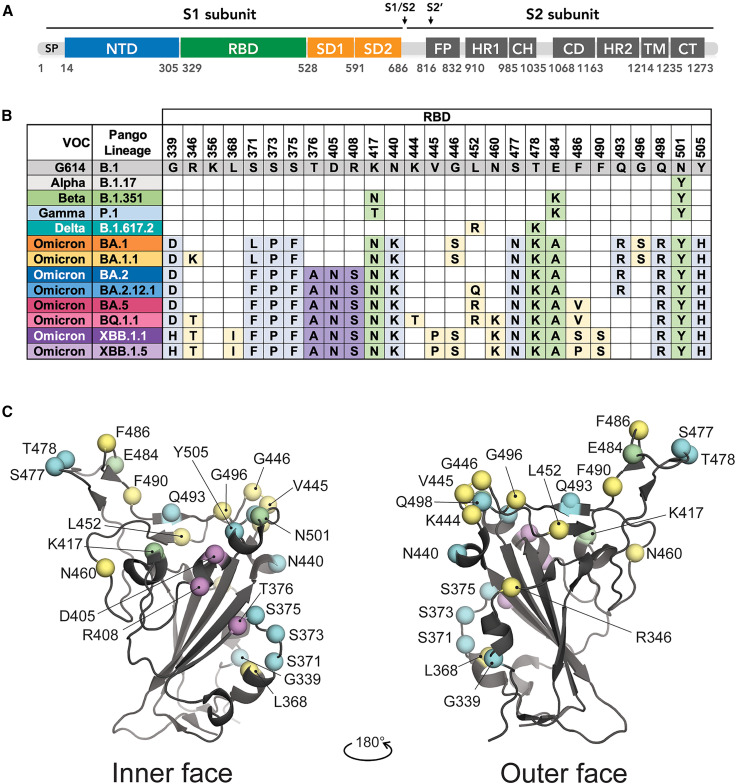

Figure 1.

Variant-related mutations on the SARS-CoV-2 spike

(A) Spike primary structure with subunit domain boundaries denoted. SP, signal peptide; NTD, N-terminal domain; RBD, receptor-binding domain; SD1, subdomain 1; SD2, subdomain 2; S1/S2, furin cleavage site; S2’,S2 sub-cleavage site; FP, fusion peptide; CH, central helix; HR1, heptad repeat 1; CD, connector domain; HR2, heptad repeat 2; TM, transmembrane domain; CT, cytoplasmic tail.

(B) Positions and substitutions of variant-related mutations located in the RBD compared with the B.1 lineage. The World Health Organization variant designation and Pango lineage are indicated for each variant of concern (VOC).

(C) Cartoon representation of the RBD and positions of variant-related mutations. Mutations shared among Omicron variants but not with other VOCs are colored light blue. Those found in BA.2 and related lineages are colored purple. Green indicates mutations found in multiple VOCs. Positions that are less frequently mutated in multiple VOCs (e.g., R346, L452, and N460) are colored yellow.

See also Figures S1 and S2.

Omicron BA.1 was first identified in late 2021 in South Africa13 and rapidly became the dominant circulating variant.14 BA.1 harbored more than 30 mutations throughout the spike, including a six- and three-residue insertion in the N-terminal domain (NTD) as well as 15 S1 domain point mutations, 9 of which localize to the RBD.15 Several Omicron lineages and sublineages characterized after BA.1 share mutations with other VOCs (i.e., L452, E484, K417, T478, and N501)16 , 17 , 18 but also have less frequent mutations like S371L, S373P, S375F, N440K, F486V, and Y505H (Figures 1B and 1C). BQ.1.1, a relative of BA.5 and XBB, a recombinant of two BA.2 lineages, was recently identified in several regions and carries R346T, K444T, N460K, F486S/P, and F490S mutations.19

Omicron-associated mutations occurring across the spike epitope landscape profoundly affect vaccine and therapy efficacy.20 Most antibodies that received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) emergency use authorization lost most or all efficacy against at least one Omicron lineage.7 , 21 , 22 , 23 Even antibodies targeting epitopes in highly conserved regions that were thought to be resistant to escape have reduced efficacy against one or more Omicron lineages.21 , 22 , 23 , 24

Identification of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that remain effective against newly emergent or divergent VOCs is critical for continued development of durable COVID-19 therapeutics. Understanding antibody epitopes and recognition patterns that retain activity against the broad array of variants also informs next-generation vaccine development. Some research groups focused on immunization of animals or computational approaches to develop mAbs, but patient samples are still the most frequent source of antibodies for therapeutic development.25 Here we report isolation of several antibodies from a double-vaccinated Californian that are effective against prominent VOCs, including several Omicron lineages. Epitope mapping identifies pairs of these mAbs that bind SARS-CoV-2 spike simultaneously. High-resolution structural analyses of three of these antibodies in complex with B.1 (D614G) or Omicron-BA.1 spike illuminate the binding surfaces and different ways in which these antibodies interact with the RBD. Further, these three antibodies protect against infection of K18-hACE2 transgenic mice with BA.1 and BA.2. These antibodies provide important therapeutic options to replace antibodies that escaped.

Results

Isolation of antibodies from an mRNA vaccinee

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from a patient in April 2021, 20 days after their second dose of the Moderna mRNA-1273 vaccine. This subject had high neutralizing titers against the ancestral D614G variant and maintained moderate to high titers against other VOCs, including Beta, Delta, and Omicron lineages BA.1, BA.1.1, and BA.2 (Figure S1A). Memory B cells were enriched and activated for 10 days before loading onto a Berkeley Lights Beacon optofluidics instrument and isolated as single cells in NanoPens. SARS-CoV-S (HexaPro-Delta) antigen reactivity of secreted antibodies was measured in real time for thousands of cells simultaneously (Figure S1B). In total, 158 unique Delta-spike-reactive monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were obtained from the activated B cells. The majority of isolated mAbs (n = 92) targeted the RBD. An additional 25 bound to the NTD, and 41 were reactive to spike only, presumably binding to an epitope in S2, to regions outside of the boundaries for the NTD or RBD constructs used in these studies or to an epitope only displayed in the context of the trimer (Figures S1C and S1D). Of the spike-reactive antibodies, 110 recognized Omicron-BA.1 spike, with about half targeting the RBD specifically (Figure S1D).

We next used a high-throughput single-cycle VSV pseudovirus (VSVpp) neutralization assay to assess the ability of the antibodies to reduce infection with G614, Delta, and Omicron-BA.1 pseudoviruses. Briefly, pseudovirions were first incubated with diluted (1:10) antibody expression supernatant and then allowed to infect Vero cells. Under these conditions, one-third (55 of 158) and one-quarter (43 of 158) of spike-reactive antibodies decreased infection with G614-VSVpp and Delta-VSVpp, respectively (Figure S1C). Among mAbs that neutralized both G614 and Delta, just five (1C3, 2A10, 4H4, 1H2, and 2E6) decreased infection of BA.1-VSVpp by more than 85%. Sequence analysis for these five mAbs demonstrates use of a variety of heavy and light chains (HC and LC, respectively) (Figure 2 A). Two mAbs (2A10 and 4H4) are derived from the 3–53 heavy-chain germline, which has been identified as a public clonotype for SARS-CoV-2 neutralization.26 , 27

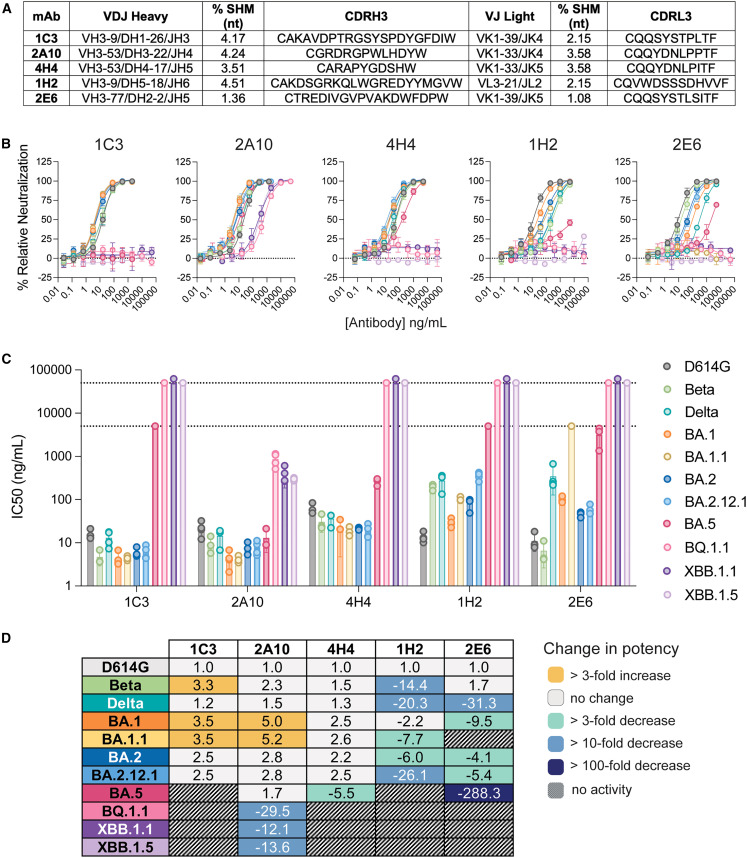

Figure 2.

Broadly neutralizing antibodies from a vaccinee

(A) The heavy (top) and light (bottom) germline, percent somatic hypermutation (SHM), and complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) sequence are shown for each bNAb.

(B) Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 pseudoviruses bearing the spike of the indicated VOC. Color coding corresponds to the key shown in (C).

(C) Half-maximal inhibitory concentrion (IC50) values for each neutralization curve in (B), calculated by nonlinear regression analysis. The limit of detection (L.O.D.) is shown as a dotted line and indicates the maximum antibody concentration used in the experiment.

Error bars for (B) and (C) indicate the standard deviation from the mean for at least three independent experiments, each performed in technical duplicates.

(D) Fold change in IC50 for each antibody:variant pair relative to D614G.

Broadly neutralizing antibodies cluster into three competition groups

To determine the relative potency of the five broadly neutralizing mAbs (bNAb), we obtained a full dose-response curve with purified 1C3, 2A10, 4H4, 1H2, and 2E6 immunoglobulin G (IgG) against VSVpp bearing the spike of the G614 virus or prominent VOCs, including Beta and Delta and the Omicron lineages BA.1, BA.1.1, BA.2, BA.2.12.1, BA.5, BQ.1.1, XBB.1.1, and XBB.1.5. 2A10 and 4H4 retained activity against VOCs through BA.5 (Figures 2B–2D; Table S1). Notably, 2A10 was broadly neutralizing and highly potent (4–13 ng/mL) against many of the Omicron lineages tested. 2A10 also neutralized BQ.1.1 and both XBB variants, albeit with lower potency. In contrast, 1C3 showed potent neutralization against only the BA.1 and BA.2 lineages and sublineages (4–6 ng/mL). mAbs 1H2 and 2E6 had variable potency against Beta, Delta, and BA.1.1 and BA.5 pseudoviruses. In particular, mAb 2E6 failed to neutralize BA.1.1, presumably because of the R346K mutation that distinguishes this sublineage from the BA.1 parent. Like 1C3, 1H2 and 2E6 lost activity against BA.5, BQ.1.1, XBB.1.1, and XBB.1.5.

Pairwise competition analysis of the RBD and each bNAb was used to identify the antibody community for each mAb (Figure S1E). We increased the competition matrix resolution using previously characterized antibodies and those identified in these studies but with more restricted breadth as sentinels. Based on our previous classification of over 350 RBD-directed neutralizing antibodies,24 , 28 1C3, 2A10, and 4H4 are in the RBD-2 community, and each blocks RBD interaction with ACE2 (Figure S1E). These three mAbs can co-bind with 1H2 and 2E6, but they segregate into different sub-communities (2a, 2b, and 2c for 4H4, 1C3, and 2A10, respectively) because of differential interaction with RBD-3, RBD-6, and RBD-7 mAbs. 2E6 is an RBD-4 antibody and blocks ACE2 binding, while 1H2 is an RBD-5 antibody that does not block ACE2 binding (Figure S1E).

We also used negative-stain electron microscopy to confirm the epitope groups identified in our competition screen and to further map the epitope location and binding mode for each of the five bNAbs (Table S2). Consistent with our previous findings,24 the RBD-2 mAbs 1C3, 2A10, and 4H4 engage the trimeric spike in a bivalent manner, in which each antibody fragment (Fab) of a single IgG contacts a single spike protein from the top of the receptor binding motif (RBM), pulling the RBDs upright (Table S2). In contrast, mAbs 1H2 and 2E6 cross-link adjacent spikes, with each Fab anchored to a separate molecule (Table S2). Because nearly all 1H2 IgG bound two spikes simultaneously, we made a 3D reconstruction of its Fab bound to spike. Although 1H2 and 2E6 bind the outer face of the RBD, 1H2 contacts at least one “up” RBD, whereas 2E6 binds to all “down” RBDs (Table S2).

Avidity enhances neutralization for some mAbs

Electron microscopy (EM) analysis with intact IgG demonstrates that avidity is a common feature among RBD-targeted mAbs24 , 28 (Table S2). Here we examined whether avidity is critical for 1C3, 2A10, and 1H2 neutralization activity by measuring the ability of the Fab fragments to neutralize D614G, Delta, BA.1, BA.2, or Beta pseudoviruses. 1C3 and 2A10 IgGs anchor to spike bivalently through a similar epitope, but their Fabs have markedly different neutralization potency toward BA.1, BA.2, and Beta pseudovirions (Figures 3A and 3B; Table S1). The 1C3 Fab maintains robust potency against all five variants examined, but for 2A10, the Fab potency is reduced 2,000–5,000-fold against BA.1 and Beta relative to the intact IgG and reduced by more than 300-fold against BA.2 compared with IgG. The 2A10 IgG and Fab neutralization potencies against D614G and Delta pseudoviruses are similar. Antibody 1H2, which targets a different epitope on the outer face of the RBD and cross-links spikes as an IgG, showed reduced Fab-mediated neutralization for all five viruses, but the Fab and IgG had similar variant-linked reductions in neutralization (Figure 3C).

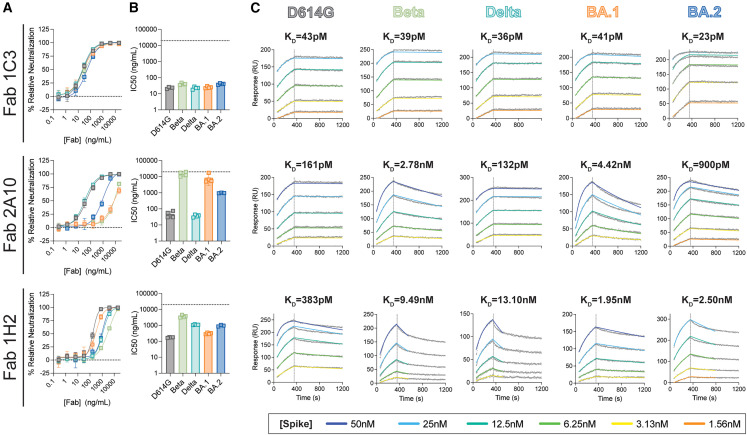

Figure 3.

Neutralization and kinetics analysis of select VOCs and Fab fragments

(A) Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 pseudoviruses bearing the spike of the indicated VOC by the Fab of each indicated antibody.

(B) IC50 values for each neutralization curve, calculated by nonlinear regression analysis. The L.O.D., shown as a dotted line, indicates the maximum concentration of antibody used in the experiment (5,000 or 50,000 ng/mL).

For (A) and (B), error bars indicate the standard deviation from the mean of four experiments, each performed in technical duplicates.

(C) SPR analysis of each Fab:spike pair, as indicated. The Fab ligand used for each experiment remains constant across each row, and the spike analyte remains constant for each column. The average KD obtained from eight replicate experiments is shown above each plot. Raw data are colored gray, with the 1:1 fit colored according to the spike concentration. For 1H2, the dissociation was truncated to 450 s to capture an accurate off-rate.

The marked difference between 2A10 IgG- and Fab-mediated neutralization of Beta, BA.1, and BA.2 pseudoviruses suggests that reductions in affinity caused by mutations in these spikes are overcome by avidity. On the other hand, 1H2-mediated spike cross-linking enhances neutralization, but affinity associated with the single-Fab footprint appears to play a larger role overall in its activity. To test this hypothesis, we compared the binding characteristics of the IgG and Fab of 1C3, 2A10, and 1H2 to D614G, Delta, and BA.1 spike ectodomains using high-throughput surface plasmon resonance (SPR; Carterra LSA platform). We also analyzed the binding kinetics of each Fab to BA.2 and Beta spikes.

Consistent with our neutralization results, 1C3 IgG and Fab had picomolar affinity (15–40 pM) for each spike tested (Figures 3A and S2A; Table S3). In contrast, 2A10 Fab and IgG bind similarly to D614G and Delta spikes, but for BA.1 spike, the Fab affinity is 15-fold lower than for IgG (0.3 nM vs. 4.4 nM). Binding of 2A10 Fab to Beta and BA.2 spikes was also reduced (KD 2.8 nM and 1 nM, respectively) (Figures 3B and S2A; Table S3). For 1H2, which binds the outer face of the RBD, IgG and Fab exhibited similar decreases in affinity for each spike, and the KD values mirrored the IC50 of neutralization for the corresponding pseudovirus (Figures 3C and S2A; Tables S1 and S3).

Taken together, these data highlight the different avidity requirements for 1C3, 2A10, and 1H2 neutralization of pseudoviruses bearing D614G, Beta, Delta, or BA.1 and BA.2 spikes. 1C3 has high affinity for these five spikes and does not require avidity for potent neutralization. For 2A10, avidity offsets decreased affinity for Beta, BA.1, and BA.2 spikes to maintain potent neutralization. For 1H2, affinity and avidity are important for high neutralization potency.

Structural analysis of broadly neutralizing mAbs

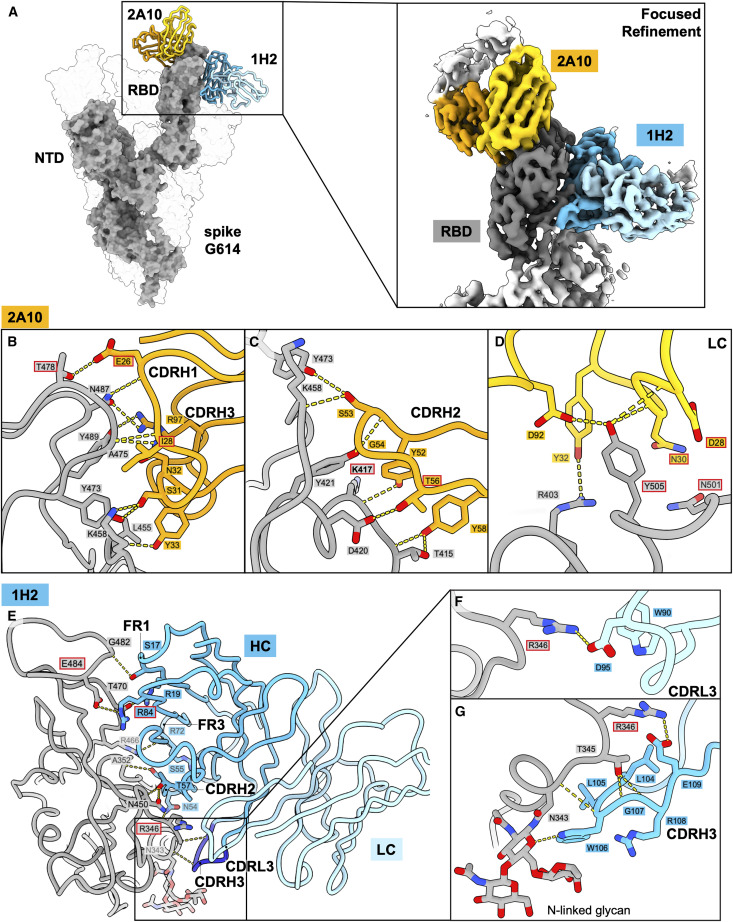

We used cryo-EM to illuminate the epitopes of three of the Omicron-neutralizing antibodies. The Fab of RBD-2b antibody 1C3 in complex with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 spike was solved to 3.4 Å (Figures 4A and S3; Table S4). The Fabs of the RBD-2c antibody 2A10 and the RBD-5 antibody 1H2 were solved together as a ternary complex with SARS-CoV-2 D614G spike to global 3.2-Å resolution (Figures 5A and S3; Table S4).

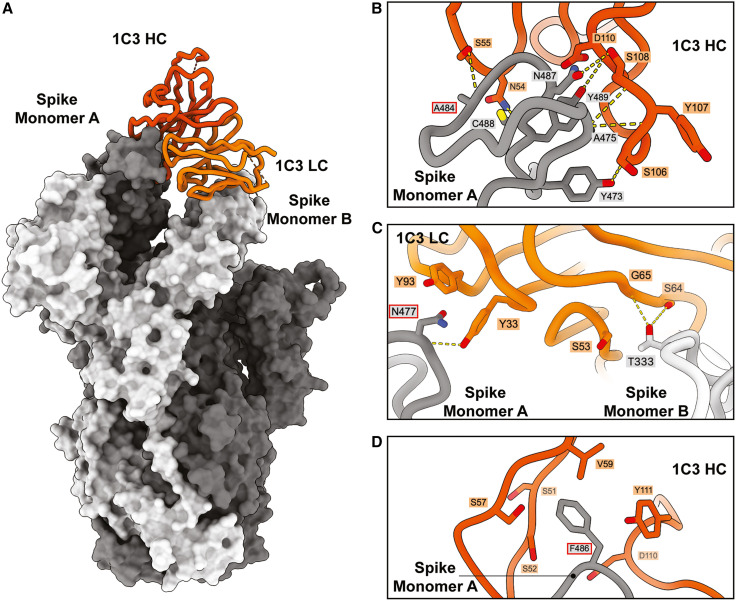

Figure 4.

Cryo-EM analysis of the 1C3-spike complex and interactions between 1C3 and Omicron BA.1 RBD

(A) Model of the cryo-EM structure of 1C3 Fab in complex with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 spike (PDB: 8F0G). One copy of 1C3 Fab (shown as cartoon representation with the HC and LC shown in dark and light orange, respectively) simultaneously contacts two spike monomers (shown as a surface representation), A (gray), and B (light gray).

(B) SARS-CoV-2 Omicron spike interactions with 1C3, a close-up view of 1C3 HC interacting with the spike RBD in monomer A. Dashed yellow lines indicate hydrogen bonds.

(C) Close-up view of 1C3 light chain interacting with the spike RBD in monomers A and B. Dashed yellow lines indicate hydrogen bonds.

(D) RBD residue F486 in BA.1, which is mutated to valine in BA.5, forms intensive hydrophobic contacts with 1C3 HC residues.

See also Figures S1–S5 and Tables S2 and S4.

Figure 5.

Cryo-EM analysis of the 2A10-1H2-spike complex and interactions between 2A10, 1H2, and D614G RBD

(A) Model of the cryo-EM structure of 1H2 and 2A10 Fabs in complex with SARS-CoV-2 D614G spike. The local refined structure of the RBD complexed with the two Fabs is modeled on the D614G spike model (shown as surface representation; PDB: 8F0H). Only one copy of each of the two Fabs is shown as a cartoon representation. 2A10 is shown in orange (HC) and yellow (LC), and 1H2 is shown in dark (HC) and light blue (LC).

(B–D) Interactions between 2A10 and D614G spike. 2A10 mainly utilizes heavy-chain complementarity-determining region (CDR) H1 (B) and CDRH2 (C) and LC residues from CDR L2 and L3 (D) to contact the spike. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by yellow dashed lines. Red outlines highlight 2A10 residues that are mutated from the germline as well as spike residues mutated in Omicron variants (K417N, T478K, N501Y, and Y505H).

(E–G) Interactions between 1H2 and D614G spike. Contacts to the spike RBD by 1H2 residues from framework region (FR) 1, CDRL2, and FR3 are shown in (E). Magnified views of contacts are shown in (F) for CDRL3 and in (G) for CDRH3. N343-linked glycans are shown as sticks. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by the yellow dashed lines. 1H2 residue R84 is mutated from the germline and is outlined in red. Spike residues mutated in Omicron variants (R346K in BA.1.1, E484A) are also labeled with red outlines.

See also Figures S1–S7 and Tables S2, S4, and S5.

Avidity independence of RBD-2b antibody 1C3 achieved through differential engagement of spike by the Fab

Negative-stain EM of 1C3 IgG in complex with D614G or BA.1 spike shows three Fabs (two from one IgG and another from a second IgG) simultaneously engaging three RBDs to pull them into an upright “goal post” position (Table S2). Each Fab interacts with a single RBD despite having one IgG binding bivalently and the other binding the single remaining RBD.

In contrast, cryo-EM analysis of 1C3 Fab bound to spike shows sub-stoichiometric asymmetry: only one copy of the 1C3 Fab is stably bound per trimeric spike and simultaneously interacts with two RBDs (Figure 4A). The heavy- and light-chain complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) bind ∼740 Å2 of molecular surface at the apex of the monomer A RBD, while the framework of the light chain simultaneously contacts ∼240 Å2 of molecular surface on the adjacent “down” RBD of monomer B, effectively locking the spike in a mostly closed state. Although an additional Fab could bind the third RBD, such a configuration is not visually apparent in this relatively small dataset (50,000 particles). Curiously, the Fab and the IgG engage the RBD differently; IgG binding lifts the RBD to a fully upright position characteristic of RBD-2 antibodies, while the Fab alone lifts it only slightly upward (Table S4). The bivalency and coupling of the two Fabs in an IgG likely drives the greater lifting force. For 1C3, the IgG and Fab have similar neutralization activity. The unusual binding mode of the isolated 1C3 Fab (unconstrained by its paired Fab in the in vivo-relevant IgG) in which the light chain and framework lock two adjacent RBDs in the closed position may partially explain the ability of the Fab to maintain a neutralization potency similar to its IgG. The notable difference in mode of recognition between IgG and Fab also suggests that, for some antibodies, examination of Fab structure alone may not fully illuminate interactions and activities that occur with complete IgG.

The majority of the 1C3 paratope lies within CDRH2 and CDRH3, which surround the RBD apex (Figures 4B, S4A and S4B). Only light-chain residues Y33 and Y93 contact the monomer A RBD (Figure 4C). The light-chain CDRL2 and framework region 3 (FR3) mediate contact with the adjacent monomer B (Figure 4C). Of the 15–17 RBD residues that have substitutions in the various Omicron lineages, 1C3 contacts the side chain of only F486, which sits in a hydrophobic pocket formed by several CDRH2 and CDRH3 residues, including S51 in CDRH2 and D100 and Y111 in CDRH3 (Figure 4D). We find that F486 is rotated relative to its position in an antibody-free BA.1 spike (PDB: 7WPB) and to its position in the 2A10-1H2-D614G ternary structure (see below). F486 may function as a keystone for 1C3 binding (Figure S5), particularly given the loss of 1C3-mediated neutralization of variants like BA.5 that carry mutations at this residue. To address this possibility, we used SPR to measure the affinity of 1C3 Fab for spike with F486V as a single point mutation and in the context of the full complement of mutations found in BA.5. The strength of the interaction between 1C3 and F486V-spike was reduced by ∼1,500-fold relative to G614 spike with F486 (66 nM vs. 0.04 nM; Figure S2B; Table S3). This disparity in affinity was driven primarily by the more than 300-fold faster off-rate of F486V from 1C3. The affinity for BA.5 spike was higher than that of F486V alone (7 nM) because of the slower off-rate. However, the overall binding efficiency was poor.

Importance of germline-encoded residues in 2A10 recognition of Omicron-specific substitutions

The structure of mAb 2A10 was resolved in complex with SARS-CoV-2 D614G spike together with mAb 1H2. In this complex, all three RBDs of the spike are in the up conformation, and three copies each of 2A10 and 1H2 can bind per spike trimer. However, the flexibility of the “up” RBDs and six Fabs compromises resolution. We performed focused refinement to improve the local resolution of the antibody-antigen binding regions and built a model for a single RBD in complex with one copy of 2A10 Fab and one copy of the 1H2 Fab (Figure 5A; Table S4). In addition, we used X-ray crystallography to solve the structure of the RBD in complex with 2A10 Fab to 2.57 Å (Table S5). The Fab binding footprints are essentially identical between the cryo-EM and X-ray structures. Consistent with the ACE2 blocking analysis (Figure S1E), the 2A10 epitope largely overlaps the ACE2 receptor footprint, with heavy and light chains obstructing its access. The 2A10 heavy chain buries ∼680 Å2 of spike surface area with mostly CDRH1 and CDRH2, while the light chain buries ∼210 Å2, primarily through CDRL1 (Figures 5B–5D).

The 2A10 heavy chain derives from the public germline IGHV3-53 and the light chain from IGKV1-33 (Figure S4A). The majority of side-chain-mediated contacts made by 2A10 to the RBD are through germline-encoded residues. Only four residues are somatically mutated: G26E, T28I, and S56T from the heavy chain and S30N from the light chain (Figures S4A and S4C). G26E forms hydrogen bonds with RBD residues T478 and N487, T28I is in close contact with RBD residue K458, and S56T hydrogen bonds with D420. S30N is bound by N501 (Figures 5B–5D). Like several previously described mAbs from the IGHV3-53 germline,26 , 27 , 29 the 2A10 CDRH3 is short (13 residues) and contributes less to antigen interaction. Six residues in CDRH1 and four residues in CDRH2 contact the RBD, whereas only two CDRH3 residues contact the RBD, including residue R97, which forms hydrogen bonds with RBD residues N487 and Y489 (Figures 5B and 5C).

2A10 maintains remarkable breadth and potency against Omicron pseudoviruses, even though several substitutions shared by multiple variants lie within its epitope. Specifically, the RBD mutations K417N, S477N, T478K, N501Y, and Y505H are found together in all Omicron lineages. The 2A10 CDRH1 residue E26 contacts S477 and T478 side chains, while CDRH2 Y52 forms a hydrogen bond to the main-chain nitrogen of K417 (Figures 5B, 5C, and S6B). The light-chain residues CDRL1 N30 and CDRL3 D92 form hydrogen bonds with N501 and Y505, respectively (Figures 5D and S6D). Modeling of the mutations at these RBD residues suggests that this hydrogen bonding would be preserved (Figure S6D).

Previous studies identified K417N as a key mutation for escape from VH3-53 mAbs in particular and certain sub-communities of the RBD-2 group in general.24 , 30 In contrast, S477N, T478K, and N501Y mutations did not affect most RBD-2 mAbs.24 To understand whether any of these residues, or Y505H, are individually responsible for the reduced affinity of 2A10 for some variants, we performed binding analyses between the Fab and spikes bearing single point mutations. The mutations S477N, T478K, and N501Y had no impact on Fab binding affinity, while the Y505H mutation reduced the affinity of 2A10 Fab for spike from 0.16 nM to 0.7 nM (∼4.5-fold) (Figure S2C; Table S3). However, the affinity of 2A10 Fab for spike containing only N417 was reduced by ∼40-fold compared with spike containing K417 (7 nM vs. 0.16 nM), even though this RBD residue does not form hydrogen bonds or salt bridges with the antibody. Curiously, the affinity of 2A10 Fab for Beta, BA.1, and BA.2 spikes, which all contain K417N, is higher than that for the single point mutation alone (KD of 2.8 nM, 4.5 nM, and 0.9 nM, respectively). Hence, the additional substitutions present in these variants may have a positive additive effect. Indeed, 2A10 binds spike bearing K417N-T478K, K417N-N501Y, or K417N-Y505H double point mutations with 1.5–2 times greater affinity relative to spike with the single K417N point mutation. Notably, 2A10 affinity for Beta, which contains K417N and N501Y, was similar to the double point mutation. Modeling suggests that N417 could be readily accommodated within the 2A10 epitope and may even form new hydrogen bonds to heavy chain residues Y33 and/or Y52 (Figures S6A and S6D).

In addition to substitutions in BA.2, the more recently evolved Omicron sublineage BA.5, BQ.1.1, XBB.1.1, and XBB.1.5 each have a substitution at F486 (as well as other substitutions outside of the 2A10 epitope), and BQ.1.1 and XBB variants also have an N460K substitution. F486 and N460 lie on the periphery of the 2A10 footprint; F486 packs into a hydrophobic groove formed by 2A10 HC residues V2 and F27, and N460 forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone oxygen of G54 in CDR-H2 (Figures S6C and S6D). Spike with an F486V single point mutation bound to 2A10 Fab with similar affinity as BA.2 (Table S2; Figure S6B). However, the 2A10 Fab had over 7-fold lower affinity for BA.5 than BA.2 spike (∼7 nM vs. 0.9 nM). Hence, while mutations to F486 alone do not impact affinity, they have a negative additive effect in the context of other mutations. Nevertheless, 2A10 IgG maintains robust neutralization of BA.5 pseudovirions (12 ng/mL), indicating again that the avidity of the 2A10 IgG surmounts the poor affinity of a single Fab. For BQ.1.1 and both XBB lineages in particular, the 2A10 Fab has a drastic reduction in affinity relative to IgG. Surprisingly, although BQ.1.1 and XBB share many mutations, there is a marked difference in the affinity of 2A10 Fab for the respective spikes (∼10 nM vs. ∼5 μM) and for the IgG (4.5 nM vs. 23 nM). Nevertheless, 2A10 neutralization potency against XBB.1.1 and XBB.1.5 pseudoviruses is 3-fold higher than for BQ.1.1 pseudoviruses.

An unusual binding mode renders 1H2 vulnerable to spike mutations

Cryo-EM analysis of the 1H2 Fab in complex with D614G spike reveals its unusual binding pattern that involves a near-parallel approach angle to the RBD (Figures 5A and 5E). Because of this approach, CDRH2 and CDRH3 and the heavy-chain FR1 and FR3 contribute significantly to the 1,000 Å of RBD surface buried by the antibody (Figure 5E). The 1H2 epitope footprint does not overlap with the ACE2 binding site, consistent with the ACE2 competition studies.

1H2 and 1C3 are derived from the same heavy-chain germline (IGHV 3–9) but bind different epitopes (Figures S4A, S4B, and S4D). Most non-CDR residues involved in the heavy chain-RBD interface are conserved or very similar between 1H2 and 1C3 (Figure S4A). The sole exception is R84 (N84 in 1C3), which forms a salt bridge with the RBD residue E484 (Figures 5E and S7C). Otherwise, each of the 10 additional RBD contacts mediated by FR1 and FR3 occur through germline-encoded residues. Given that 1C3 and 1H2 do not compete with one another, the differences in the CDRs, especially CDRH3, likely drive recognition of the distinct epitope by the same IGHV 3–9 germline.

Because of its angle of approach, the 1H2 CDRH3 must bend 45° to interact with the RBD (Figures 5E and 5G). Contacts between CDRH3 residues 104–109 and RBD residues N343, T345, and R346 stabilize the CDR in this bent position (Figure 5G). CDRH3 residue W106 hydrogen bonds to the N-acetylglucosamine and stacks atop the fucose at N343 (Figure 5G). Likewise, the main chains of antibody residues L105 and G107 contact RBD residues N343 and T345, respectively (Figures 5E and 5G). E109 of CDRH3 hydrogen bonds with R346 (Figures 5E and 5G). The light chain has minimal involvement in the 1H2 epitope and contacts only R346 of the RBD through CDRL3 residues W90 and D95 (Figure 5F).

The 1H2 binding site contains several spike residues that are frequently mutated in VOCs, including R346, L452, and E484. CDRs H2, H3, and L3 of 1H2 create a hydrophobic pocket for the aliphatic portion of R346 and form hydrogen bonds with the guanidinium head group (Figure S7A). The R346K mutation in BA.1.1 may weaken the hydrogen bonds to 1H2 residues E109 in CDRH3 and D95 in CDRL3 (Figure S7A; Table S3). Meanwhile, residues L452 and E484 are in close contact with the 1H2 FR3 (Figures 5E and S7). Mutation of L452 in the RBD to either Arg or Gln (found in Delta and BA.5 and BA.2.12, respectively) would produce a steric clash with the FR3 residue T69 (Figure S7B). Similarly, mutation of E484K, as found in Beta, or E484A, found in all Omicron lineages, would abolish the salt bridge with FR3 residue R84 (Figure S7C).

Interestingly, the E484K mutation and L452R/Q mutations, found in Delta and BA.2.12, respectively, appear to have a greater impact neutralization potency than the E484A and R346K mutations of BA.1/BA.1.1 (20- to 25-fold vs. 8-fold reduction relative to D614G pseudovirus; Figures 1D and S2D; Tables S1 and S3). Kinetics analysis of 1H2 Fab and spike bearing either R346K or E484A had little to no impact on affinity (Figure S2D; Table S3). The affinity of spikes bearing either E484K or L452R single point mutations, however, was reduced to ∼5.5 nM from 380 pM for D614G spike (Figure S2D; Table S3). Thus, the effects of E484A/K and L452 mutations appear to be additive. Although neither R346K or E484A impacted affinity in isolation, 1H2 neutralizes BA.1.1 with ∼3-fold lower potency than BA.1. Likewise, 1H2 Fab bound to BA.5 spike, which contains both E484A and L452R, with only ∼70 nM affinity, and therefore, the IgG cannot neutralize BA.5. Taken together, the non-canonical binding of the 1H2 FR3 region to the RBD appears to be a liability rather than a benefit.

Prophylactic efficacy against BA.1 and BA.2 variants

mAbs 1C3, 2A10, and 1H2 were down-selected for in vivo analysis based on their potency, their broad neutralization, and the ability of 1C3 and 2A10 to co-bind with 1H2 on spike. The prophylactic efficacy of each mAb was assessed individually in K18-hACE2 transgenic mice that were administered a single 10 mg/kg (∼200 μg) dose of IgG by intraperitoneal injection 1 day prior to intranasal inoculation with 104 plaque-forming units (PFUs) of either BA.1 (Figure 6 A) or BA.2 (Figure 7 A).

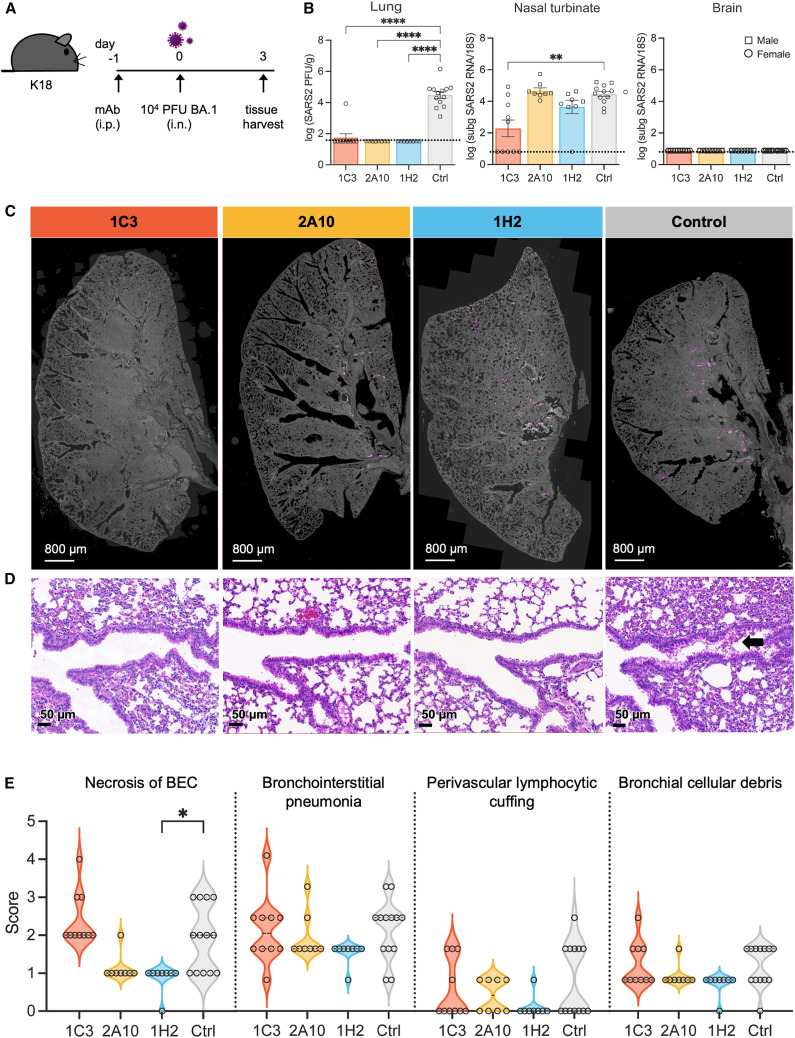

Figure 6.

Antibody-mediated protection of BA.1 challenge in K18-huACE2 mice

(A) Experimental design for (B)–(D).

(B) Infectious virus titers measured by plaque assay of lungs collected from mice challenged with 104 PFUs SARS-CoV-2 BA.1 after passive transfer with mAb (left). Subgenomic 7a SARS-CoV-2 RNA at 3 dpi was detected by qRT-PCR in the nasal turbinates (center) or brain (right).

(C) Lung images are representative of the distribution of immunofluorescence SARS-CoV-2 N protein staining (magenta).

(D) Representative histopathology images from lung samples stained with H&E. An arrow indicates BEC necrosis.

(E) Histopathological features of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the lungs of mice were scored from 0 (least severe) to 5 (most severe).

For (B) and (E), data represent two independent experiments for a total of 8–13 mice per group. Individual mice are represented as a square (male mouse) or circle (female mouse). Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis by Kruskal-Wallis test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Only significant differences are shown. The L.O.D. of each assay is represented by a dotted line.

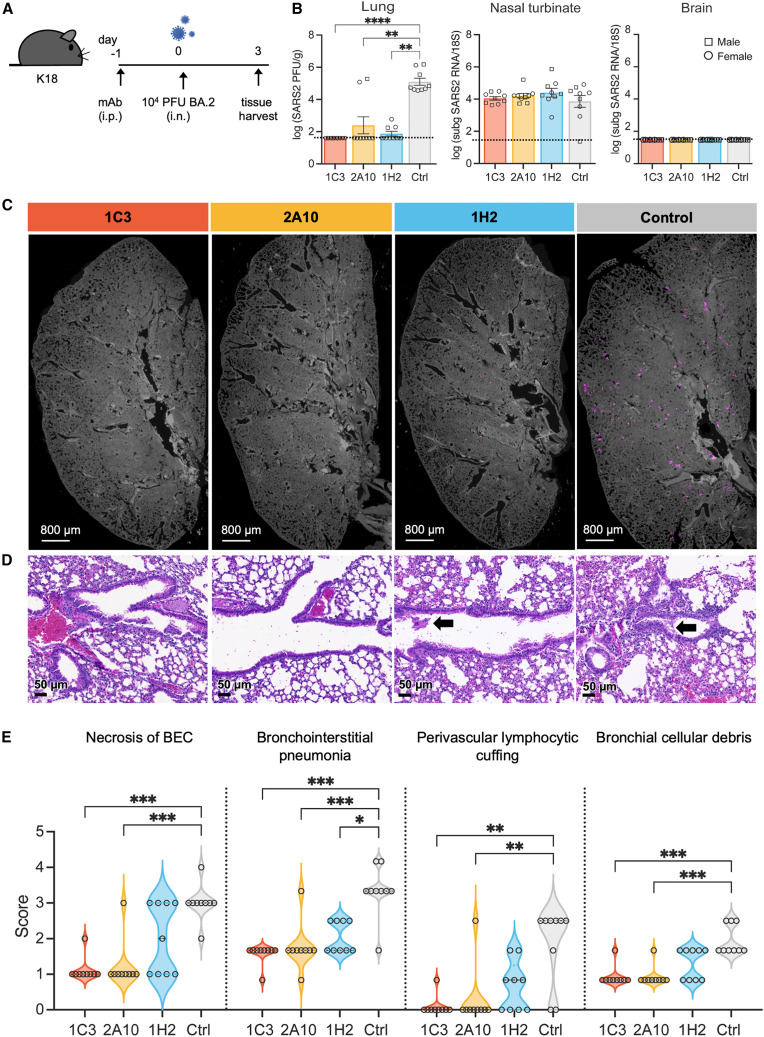

Figure 7.

Antibody-mediated protection of BA.2 challenge in K18-huACE2 mice

(A) Experimental design for (B)–(D).

(B) Infectious viral particles in lungs were titrated using plaque assay at 3 dpi (left). Replicating virus was detected at 3 dpi by qRT-PCR of subgenomic 7a SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the nasal turbinates (center) and brain (right).

(C) Immunofluorescence distribution of SARS-CoV-2 N protein staining (magenta) of lungs.

(D) Representative histopathology images from lung samples stained with H&E. Arrows indicate BEC necrosis.

(E) Histopathological features of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the lungs of mice were scored from 0 (least severe) to 5 (most severe).

Data for (B) and (E) represent two independent experiments for a total of 9 mice per group, with each mouse represented as a square (male mouse) or circle (female mouse). Error bars indicate the SEM. Statistical analysis by Kruskal-Wallis test. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Only significant differences are indicated. A dotted line represents the L.O.D. of each assay.

To compare viral burden after prophylactic treatment with each mAb and virus challenge, we measured infectious virus in the lungs by plaque assay and replicating virus in the nasal turbinates and brain by qRT-PCR of subgenomic 7a viral RNA 3 days post infection (dpi). Notably, treatment with 2A10 or 1H2 reduced infectious virus to undetectable levels in the lungs of all BA.1-infected mice and in all but one 1C3-treated mouse (Figure 6B). Infectious virus in the lungs of BA.2-infected mice was undetectable in all 1C3-treated animals and in 7 of 9 and 6 of 9 animals treated with 2A10 or 1H2, respectively (Figure 7B). Antibody 1C3 also reduced the level of subgenomic viral RNA in nasal turbinates of BA.1-infected mice by 4.5-fold (Figure 6B). For the other antibody treatments, viral load in nasal turbinates of BA.1 and BA.2-infected mice remained constant. Similar to previous reports, none of the BA.1 or BA.2-challenged mice had detectable virus in the brain31 (Figures 6B and 7B).

Consistent with viral load data by plaque assay in the lungs, immunofluorescence staining of N protein in the lungs after mAb treatment and viral challenge revealed lower levels or no virus in 1C3-, 2A10-, and 1H2-treated mice compared with the untreated control group for both BA.1 and BA.2 challenge (Figures 6C and 7C). Overall, treatment with 1C3, 2A10, or 1H2 drastically reduced viral burden in the lower respiratory tract of BA.1- or BA.2-challenged mice.

Histopathological features of SARS-CoV-2 disease at 3 dpi were evaluated in lungs of mice treated with mAbs and then challenged with BA.1 or BA.2. Ten of 37 previously described criteria32 were evaluated, including necrosis of bronchiolar epithelial cells (BECs), bronchointerstitial pneumonia, perivascular lymphocytic cuffing, and cellular debris in the bronchi. For BA.1-infected mice, blinded examination by a board-certified pathologist indicated small to no significant differences in lungs of mice treated with 1C3, 2A10, or 1H2 compared with the anti-SARS-1 control group (Figure 6D). In BA.1-infected mice, the only lesion that was slightly but significantly reduced by mAb treatment was necrosis of BECs with 1H2 treatment compared with the control group (p = 0.005) (Figure 6E). In contrast, for BA.2-infected mice, 1C3 and 2A10 significantly reduced all lung lesions measured compared with the control PBS-treated group (Figure 7D). 1H2 reduced bronchointerstitial pneumonia but not any of the other lesions evaluated in BA.2-infected mice (p = 0.03). Thus, treatment with 1C3, 2A10, or 1H2 decreases lung pathology in BA.2-infected mice; however, the same antibody dosing regimen does not impact lung pathogenesis in BA.1-infected mice.

Discussion

The rapid emergence and multiple waves of SARS-CoV-2 variants, coupled with the expected seasonal continuation of viral infection and mutation, necessitate identification of antibodies that can provide durable protection, either through targeting conserved sites or employing avidity to retain sufficient binding to mutated epitopes to retain effectiveness in the face of continuing virus evolution. Such antibodies are needed for pre-exposure prophylaxis for immunocompromised individuals during future seasonal COVID-19 outbreaks and as treatment for acute infection of those who are unvaccinated or experience vaccine breakthrough. Information about how antibodies retain activity against a range of VOCs is also important to design next-generation vaccines that elicit broader immunity.

The antibodies described here were elicited in a human who had been twice vaccinated with the Wuhan sequence of spike and was not known to have been naturally infected. Nevertheless, this individual produced antibodies of broad utility and therapeutic protection against viruses that had not yet evolved when the vaccine was received. These results suggest that ideal antibodies exist in the vaccine-mediated repertoire and can be boosted from their memory response upon VOC infection or future vaccination.

Structural and biochemical characterization of three antibodies from this panel also provide insight into spike engagement and neutralization. The RBD-2c antibody 1C3 maintains high affinity and potent neutralization regardless of avidity. One potential explanation for this avidity independence is the differential binding modes of IgG and Fab. As an IgG, 1C3 blocks two ACE2 sites through dual engagement of two “up” RBD molecules. In contrast, the 1C3 Fab binds to one slightly up RBD and locks the adjacent RBD in the down state. Hence, a single Fab molecule can also simultaneously block two ACE2 binding sites. This antibody is, however, escaped by BA.5. BQ.1.1 and XBB variants with F486V, F486S, and F489P mutations, respectively. Any one of these mutations may either reduce contact with 1C3 within the CDRH2/H3 hydrophobic pocket or even preclude rotation of the residue itself (Figure S5). Other RBD-2b antibodies have also shown sensitivity to F486 mutations. For example, tixagevimab (AZD8895) binds in a similar location as 1C3, and while it maintains moderate neutralization against Omicron lineages BA.1 and BA.2, it loses activity against BA.5 because of the F486V mutation.20 Hence, although mAbs in this RBD-2b group exhibit resistance to many Omicron-associated mutations, the presence of phenylalanine at position 486 (F486) appears to be a keystone requirement to preserve neutralization activity, if not binding. Nevertheless, identification of the vulnerabilities within this epitope site may allow structure-guided engineering to regain function against variants with substitutions at this residue.

Unlike 1C3, the RBD-2c mAb 2A10 is remarkably resilient to multiple mutations throughout its epitope because of avid binding by the IgG. Kinetic analysis revealed a substantial reduction in affinity of the 2A10 Fab for spikes from multiple VOCs. This loss of affinity is consistent with the reduction in Fab-mediated neutralization. The avidity afforded by strong bivalent binding of the IgG overcomes the loss of affinity. Hence, despite contacting 6–8 residues that have substitutions in multiple omicron lineages, 2A10 maintains highly potent neutralization of these pseudovirions and is protective against BA.1 and BA.2 infection in a K18 mouse model.

The RBD-5 mAb 1H2 binds to the outer face of the RBD, with a substantial portion of the epitope contributed by framework regions of the variable domain. Indeed, substitutions in RBD residues contacted by CDRs (e.g., R346K) appear to have less impact than the framework contacts (e.g., E484 K/A and L452R). Like other RBD-5 mAbs,24 1H2 does not block receptor binding. Instead, it may function similarly to the RBD-5 (class 3) antibody Sotrovimab, for which neutralization involves IgG-specific bivalent mechanisms such as spike cross-linking, steric hindrance or aggregation of virions.1 , 33

Broadly neutralizing antibodies, like those reported here, are continuously identified. Nevertheless, SARS-CoV-2 evolves rapidly. Variants bearing mutations to RBD residues R346 (e.g., Mu and BA.1.1) and F486 (identified in mink populations in 202034) did not initially gain a strong foothold. However, mutations to both of these residues are now present in newly emergent variants, either alone or in combination. Additionally, mutations to RBD residues K444, V445, and N460 are also increasing in frequency. Importantly, residues K444 and V445 (identified in BQ.1.1 and XBB, respectively) were identified as key escape sites for bebtelovimab (LY-CoV140435), while the N460K mutation (identified in BA.2.75, BQ.1.1, and XBB) impacts VH3-53 mAbs that target the RBD-2 epitope36 and is likely the reason why mAb 2A10 loses some efficacy against these variants as well. Notably, bebtelovimab received emergency use authorization on February 11, 2022.35 This authorization was revoked just 9 months later with emergence of the BQ and XBB variants, highlighting the ongoing need to develop durable therapeutics.

Limitations of the study

A limitation of this study is that the serum was obtained from a single vaccinee within weeks of vaccination at a time point when antibody titers were high. Whether these select antibodies will persist or continue to mature in the face of subsequent exposures is unclear. It would be interesting to explore whether this individual subsequently produced other antibodies that had broad neutralizing potency against a range of Omicron sublineages. In addition, in experiments involving mice, we tested only one dosing protocol and did not test other doses or dosing frequency and interval. A different dose or multiple doses may be needed to determine whether antibody treatment modulates disease severity. Last, the efficacy of these antibodies in non-human primates and humans has not yet been tested, and whether these broadly neutralizing antibodies would work well in combination with antibodies targeting other sites, particularly the more conserved S2 domain of spike, awaits exploration.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| CoVIC antibodies | Hastie and Li et al.24 | https://covic.lji.org |

| Goat Anti-Human IgG-HRP | Invitrogen | Cat# A18811; AB_2535588 |

| Purified Human IgG | Invitrogen | Cat# 02-7102; AB_2532958 |

| APC/Cyanine7 anti-human CD3 Antibody | BioLegend | Cat# 344817; AB_10644011 |

| APC/Cyanine7 anti-human CD14 Antibody | BioLegend | Cat# 367107; AB_2566709 |

| APC/Cyanine7 anti-human CD16 Antibody | BioLegend | Cat# 302017; AB_314217 |

| APC/Cyanine7 anti-human CD56 (NCAM) Antibody | BioLegend | Cat# 318331; AB_10898118 |

| APC/Cyanine7 anti-human CD8a Antibody | BioLegend | Cat# 301015; AB_314133 |

| Brilliant Violet 650™ anti-human CD20 Antibody | BioLegend | Cat# 302335; AB_11218609 |

| PE-Cy™7 Mouse Anti-Human CD19 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 560911; AB_396893 |

| BB515 Mouse Anti-Human CD27 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 564642; AB_2744354 |

| Brilliant Violet 785™ anti-human IgD Antibody | BioLegend | Cat# 348241; AB_2629808 |

| PE anti-human CD38 Antibody | BioLegend | Cat# 356603; AB_2561899 |

| Goat anti Human IgG (H + L) Alexa Fluor 594 | Invitrogen | Cat# A-11014; AB_2534081 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| VSV-ΔG-GFP | Karafast | Cat# EH1020 |

| SARS-CoV-2 D614G/Vesicular Stomatitis Virus pseudovirus | This study | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 Beta/Vesicular Stomatitis Virus pseudovirus | This study | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 Delta/Vesicular Stomatitis Virus pseudovirus | This study | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1/Vesicular Stomatitis Virus pseudovirus | This study | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1.1/Vesicular Stomatitis Virus pseudovirus | This study | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2/Vesicular Stomatitis Virus pseudovirus | This study | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2.12.1/Vesicular Stomatitis Virus pseudovirus | This study | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.5/Vesicular Stomatitis Virus pseudovirus | This study | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 | BEI Resources | NR-56481 |

| SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2 | Dr. Michael Diamond | |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Uranyl formate | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Cat# 22451 |

| Papain | Sigma | Cat# P3125 |

| L-cysteine | Calbiochem | Cat# 4400 |

| PFA | Electron Microscopy Sciences | Cat# 15710 |

| Hoechst | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 62249 |

| TransIT-LT1 | Mirus | Cat# MIR 2304 |

| ExpiCHO expression medium | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A2910001 |

| BioLock | iba | Cat# 2-0205-250 |

| HRV 3C Protease | Pierce | Cat# 88946 |

| Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s Medium | Gibco | Cat# 12440-046 |

| FBS | Gibco | Cat# 26140-079 |

| Penstrept/Glutamine | Sigma | Cat# P4333 |

| Low IgG FBS | Omega Scientific | Cat# FB-06 |

| Insulin | Sigma | Cat# IO516 |

| Transferrin, Human | Sigma | Cat# T8158-100mg |

| IL-2, Human recombinant | GenScript | Cat# Z00368-50 |

| IL-21, Human recombinant | Stemcell | Cat# 78082.1 |

| IL-6, Human recombinant | Stemcell | Cat# 78050.1 |

| IFN Alpha 2b, Human recombinant | PBL Assay | Cat# 11105-1 |

| IL-15, Human recombinant | BioLegend | Cat# 715902 |

| LLME | Cayman Chem | Cat# 16008 |

| Mitomycin C | Enzo | Cat# BML-GR311-0002 |

| Benzonase | Sigma | Cat# E8263-25KU |

| LIVE/DEAD™ Fixable Aqua | Thermo Fisher | Cat# L34965 |

| Brilliant Stain Buffer | BD Biosciences | Cat# 563794 |

| Exonuclease I | Thermo fisher | Cat# EN0582 |

| FastAP™ Thermosensitive Alkaline Phosphatase | Thermo fisher | Cat# EF0652 |

| Platinum SuperFi II Green PCR Master Mix | Invitrogen | Cat# 12369050 |

| Platinum II Hot-Start Green PCR Master mix (2X) | Thermo fisher | Cat# 14001-013 |

| NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly master mix | NEB | Cat# E2621L |

| NEB 5 alpha F'Iq competent E coli | NEB | Cat# C2992I |

| E-gel96 2% with SYBR safe | Invitrogen | Cat# G720802 |

| Qiaprep 96 Turbo Miniprep kit | Qiagen | Cat# 27191 |

| SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein ectodomains with HexaPro mutations and C-terminal Foldon, HRV3C protease cleavage site, 8x-His-tag, and strep-tag | This study | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| TMB substrate kit | Peirce | Cat# 34021 |

| BirA biotin-protein ligase kit | Avidity | Cat# BirA500 |

| ExpiFectamine CHO Transfection kit | ThermoFisher | Cat# A29129 |

| Deposited data | ||

| 1C3 and Omicron BA.1 spike complex (Cryo-EM) | This study | EMD-28756 |

| 1C3 and Omicron BA.1 spike complex (Fitted coordinate) | This study | PDB: 8F0G |

| 2A10 and 1H2 Fabs in complex with D614G spike (Cryo-EM, Local Refinement) | This study | EMD-28757 |

| 2A10 and 1H2 Fabs in complex with D614G spike (Fitted coordinate, Local Refinement) | This study | PDB: 8F0H |

| SARS-CoV-2 RBD in complex with Omicron-neutralizing antibody 2A10(X-ray crystallography) | This study | PDB: 8E1G |

| Negative stain EM map of SARS-CoV-2 D614G Spike in complex with 2A10 IgG | This study | EMD-28763 |

| Negative stain EM map of SARS-CoV-2 D614G Spike in complex with 4H4 IgG | This study | EMD-28764 |

| Negative stain EM map of SARS-CoV-2 D614G Spike in complex with 1C3 IgG | This study | EMD-28765 |

| Negative stain EM map of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 Spike in complex with 1C3 IgG | This study | EMD-28769 |

| Negative stain EM map of SARS-CoV-2 D614G Spike in complex with 2G3 IgG | This study | EMD-28770 |

| Negative stain EM map of SARS-CoV-2 D614G Spike in complex with 2E6 IgG | This study | EMD-28771 |

| Negative stain EM map of SARS-CoV-2 D614G Spike in complex with 1H2 Fab | This study | EMD-28772 |

| Negative stain EM map of SARS-CoV-2 D614G Spike in complex with 1G8 IgG | This study | EMD-28773 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| 293T cells | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3216 |

| Vero cells | ATCC | Cat# CRL-1586 |

| ExpiCho-S cells | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# A29127 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Empty vector: phCMV3 | Genlantis | Cat# P003300 |

| pCAGGS-VSV-G | Kerfast | Cat# EH1017 |

| phCMV3-D614G Spike | This study | GenBank #QHD43416.1 with D614G mutation |

| phCMV3-Beta Spike | This study | GenBank #QHD43416.1 with L18F, D80A, D215G, Δ242–244, R246I, K417N, E484K, N501Y, D614G, and A701V mutations |

| phCMV3-Delta Spike | This study | GenBank #QHD43416.1 with T19R, G142D, E156G, Δ157–158, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, and D950N mutations |

| phCMV3-Omicron BA.1 Spike | This study | GenBank #QHD43416.1 with A67V, Δ69/70, T95I, G142D, Δ143/145, N211I, Δ212, ins214 EPE, G339D, S371L, S373P, S375F, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, G496S, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, T547K, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, D796Y, N856K, Q954H, N969K, and L981F mutations |

| phCMV3-Omicron BA1.1 Spike | This study | GenBank #QHD43416.1 with A67V, Δ69/70, T95I, G142D, Δ143/145, N211I, Δ212, ins214 EPE, G339D, R346K, S371L, S373P, S375F, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, G496S, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, T547K, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, D796Y, N856K, Q954H, N969K, and L981F mutations |

| phCMV3-Omicron BA.2 Spike | This study | GenBank #QHD43416.1 with T19I, L24S, Δ25/27, G142D, V213G, ins214 EPE, G339D, S371F, S373P, S375F, T376A, D405N, R408S, K417N, N440K, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, Q954H, and N969K mutations |

| phCMV3-Omicron BA.2.12.1 Spike | This study | GenBank #QHD43416.1 with T19I, L24S, Δ25/27, G142D, V213G, ins214 EPE, G339D, S371F, S373P, S375F, T376A, D405N, R408S, K417N, N440K, L452Q, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, S740L, N764K, D796Y, Q954H, and N969K mutations |

| phCMV3-Omicron BA.5 Spike | This study | GenBank #QHD43416.1 with T19I, L24S, Δ25/27, Δ69/70, G142D, V213G, ins214 EPE, G339D, S371F, S373P, S375F, T376A, D405N, R408S, K417N, N440K, L452R, S477N, T478K, E484A, F486V, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, Q954H, and N969K mutations |

| phCMV3-Omicron BQ.1.1 Spike | This study | GenBank #QHD43416.1 with T19I, A27S, Δ25/27, Δ69/70, G142D, V213G, ins214 EPE, G339D, R346T, S371F, S373P, S375F, T376A, D405N, R408S, K417N, N440K, K444T, L452R, N460K, S477N, T478K, E484A, F486V, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, Q954H, and N969K mutations |

| phCMV3-Omicron XBB.1.1 Spike | This study | GenBank #QHD43416.1 with T19I, A27S, Δ25/27, Δ69/70, V83A, G142D, H146Q, Q183E, V213G, ins214 EPE, G252V, G339H, L368I, R346T, S371F, S373P, S375F, T376A, D405N, R408S, K417N, N440K, V445P, G446S, N460K, S477N, T478K, E484A, F486S, F490S, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, Q954H, and N969K mutations |

| phCMV3-Omicron XBB.1.5 Spike | This study | GenBank #QHD43416.1 with T19I, A27S, Δ25/27, Δ69/70, V83A, G142D, V143D, H146Q, Q183E, V213G, ins214 EPE, G252V, G339H, L368I, R346T, S371F, S373P, S375F, T376A, D405N, R408S, K417N, N440K, V445P, G446S, N460K, S477N, T478K, E484A, F486P, F490S, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, D614G, H655Y, N679K, P681H, N764K, D796Y, Q954H, and N969K mutations |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| XDS | Kabsch37 | http://xds.mpimf-heidelberg.mpg.de |

| Phenix, versions 1.19 | Adams et al.38 | https://www.phenix-online.org |

| Coot | Emsley and Cowtan39 | https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| Molprobity | Chen et al.40; Williams et al.41 | http://molprobity.biochem.duke.edu |

| Pymol Molecular Graphics System | Schrödinger, LLC | https://pymol.org |

| GraphPad Prism 9 | GraphPad Software, Inc | https://www.graphpad.com |

| IMGT/V-QUEST | Brochet et al.42 | http://www.imgt.org/IMGT_vquest/vquest |

| cryoSPARC | Punjani et al.43 | https://cryosparc.com/ |

| UCSF ChimeraX | Pettersen et al.44 | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimerax/ |

| Carterra “Kinetics” and “Epitope” software packages | Carterra | https://carterra-bio.com/ |

| PDBePISA version 1.52 | EMBL-EBI | http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/pisa/ |

| Swiss-model | Waterhouse et al.45 | https://swissmodel.expasy.org/ |

| EPU | Thermo Fisher | https://www.thermofisher.com/ |

| COCOMAPS | Vangone et al.46 | https://www.molnac.unisa.it/BioTools/cocomaps/ |

| AIMLESS 0.7.7 | Evans & Murshudov47 | https://www.ccp4.ac.uk/html/aimless.html |

| CCP4 | Winn et al.48 | https://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ |

| autoPROC 1.1.7 | Vonrhein et al.49 | https://www.globalphasing.com/autoproc/ |

| Phaser 2.8.3 | McCoy et al.50 | https://www.phaser.cimr.cam.ac.uk/index.php/Phaser_Crystallographic_Software |

| Other | ||

| Berkeley Lights Beacon | Berkeley Lights, Inc | https://www.berkeleylights.com/systems/beacon/ |

| OptoSelect 11K Chip | Berkeley Lights, Inc | Cat# 750-08090 |

| OptoSeq BCR kit | Berkeley Lights, Inc | Cat# 750-01003 |

| Streptavidin Coated Polystyrene Particles | Spherotech | Cat# SVP5-60-5 |

| Carterra LSA | Carterra | https://carterra-bio.com/lsa/ |

| CMDP LSA chip | Carterra | Cat# 4282 |

| HC30M LSA chip | Carterra | Cat# 4279 |

| AmMag protein A Magnetic | GenScript | Cat# L00776 |

| AmMag SA Plus | GenScript | https://www.genscript.com/automated-magnetic-bead-systems.html |

| StrepTrap HP | GE Healthcare | Cat# 28907547 |

| HiTrap KappaFabSelect | GE Healthcare | Cat# 17545811 |

| HiTrap LambdaFabSelect | GE Healthcare | Cat# 17548211 |

| Superdex 75 Increase 10/300 GL | GE Healthcare | Cat# 29148721 |

| Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL | GE Healthcare | Cat# 28990944 |

| Superose 6 Increase 10/300 GL | GE Healthcare | Cat# 29091596 |

| Oryx Crystallization Robot | Douglas Instruments | https://www.douglas.co.uk |

| CellInsight CX5 High Content Screening Platform | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# CX51110 |

| Titan Krios | Thermo Fisher Scientific | https://www.thermofisher.com/us/en/home.html |

| Holey Carbon C-flat 2/1 400 mesh copper grids | Electron Microscopy Sciences | https://www.emsdiasum.com/ |

| Quantifoil 2/2 300 Mesh, Copper grids | Electron Microscopy Sciences | https://www.emsdiasum.com/ |

| Graphene oxide | sigmaaldrich | 763705-25ML |

| PELCO easiGlow Glow Discharge Cleaning System | Ted Pella | https://www.tedpella.com/easiGlow_html/Glow-Discharge-Cleaning-System.aspx |

| Vitrobot Mark IV | Thermo Fisher Scientific | https://www.thermofisher.com/us/en/home/electron-microscopy/products/sample-preparation-equipment-em/vitrobot-system.html |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Kathryn Hastie (kmhastie@lji.org) and Erica Ollmann Saphire (erica@lji.org).

Materials availability

All unique reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Experimental model and subject details

Human subjects

The human antibodies studied in this paper were isolated from blood samples from a vaccinated individual (male, 32 yrs) in San Diego. Samples were obtained under the Informed Consent Document from La Jolla Institute for Immunology Institutional Review Board Human Subjects Protocol IB-233-0820 A3.

K18-mouse model

K18-hACE2 (B6.Cg-Tg(K18-ACE2)2Prlmn/J) transgenic mice were bred under pathogen-free conditions at LJI or purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and housed with a 12 h on/off light cycle. Male and female mice aged 5 to 8 weeks were used in all experiments and housed in an animal biosafety level 3 containment laboratory for viral infection and manipulation. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) ABSL3 (protocol number AP00001242) and strictly conducted according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Cell lines

HEK-293T (ATCC CRL-3216, human, female) and Vero (ATCC CCL-81, monkey, female) cells were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing L-glutamine (DMEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. ExpiCHO (chinese hamster, female) cells were cultured in ExpiCHO expression medium (Thermo Fisher) and maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 8% CO2.

Viruses

Recombinant, single-cycle VSV-ΔG-GFP particles were generated by pseudotyping with a synthetic, codon-optimized SARS-CoV-2 Spike. SARS-CoV-2 variants Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 were obtained from BEI Resources (NIAID, NIH) and Dr. Michael Diamond (Washington University), respectively.

Method details

Plasmids

Plasmids for SARS-Cov-2 S with a 19-residue truncation (Δ19) were generated from a synthetic codon-optimized DNA (Wuhan-Hu-1 isolate, GenBank: MN908947.3) through sub-cloning into the pHCMV3 expression vector. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed to generate the D614G variant. Positive clones were fully sequenced to ensure that no additional mutations were introduced.

Spike proteins were generated for antibody discovery and structural biology using the HexaPro background [containing residues 14–1208 (GenBank: MN908947) of the ectodomain, six proline substitutions (F817P, A892P, A899P, A942P, K986P, V987P)51], as well as the D614G mutation and replacement of cleavage site residues 682–685 (“RRAR” to “GSAS”). Soluble NTD (residues 1–305) and RBD (residues 319–591) were generated through subcloning of the SARS-CoV-2 spike construct. Each spike domain was cloned into a phCMV mammalian expression vector containing an N-terminal Gaussia luciferase signal sequence and a C-terminal HRV-3C cleavage site and either a Twin-StrepII-Tag or an 8xHis tag to facilitate purification. HexaPro constructs also contained a foldon trimerization domain between the C terminus of S2 and the HRV-3C site. In some cases, proteins were expressed with a C-terminal Avi tag to facilitate site-specific biotinylation. Plasmids were transformed into Stellar competent cells and isolated using a Plasmid Plus Midi kit (Qiagen). All clones were fully sequenced to ensure that no additional mutations were introduced.

Transient transfection and protein purification

SARS-CoV-2 constructs were transiently transfected into ExpiCHO-S cells (Thermo Fisher). Cells were maintained and transfected according to manufacturer’s protocols. Briefly, cells were grown to a density of 1 × 107 cells/mL and diluted to 6 × 106 cells/mL on the day of transfection. Plasmid DNA and Expifectamine were mixed in Opti-PRO SFM (Gibco) according to manufacturer’s instructions, and added to the cells. Transfected cells were fed the next day with manufacturer-supplied feed and enhancer according to the suggested protocol, and cultures were then incubated at 32°C, 5% CO2 and 115 RPM. Cultures were harvested 7–8 days after transfection, or when cells reached <85% viability. All cultures were clarified by centrifugation. BioLock (IBA Life Sciences) was added to cultures transfected with constructs containing the Twin-StrepII-Tag prior to purification over a StrepTrap-HP column equilibrated with 25mM Tris pH 7.6, 200mM NaCl (TBS). After extensive washing, bound proteins were eluted in TBS buffer supplemented with 5mM d-desthiobiotin (Sigma Aldrich). Proteins with 8x-His tags were purified using magnetic NiNTA beads. After extensive washing with 25mM Tris pH 7.6, 300mM NaCl, 30mM imidazole, bound proteins were eluted with 300mM imidazole in TBS. Affinity-purified proteins were incubated with HRV-3C protease to remove purification tags and subsequently purified by size-exclusion-chromatography (SEC) on either a Superose 6 increase or Superdex 200 increase column (GE) in TBS. For experiments using biotinylated proteins, site-specific biotinylation of the AviTag was carried out by incubation with BirA ligase according to manufacturer’s instructions (Avidity) prior to purification over the appropriate column.

Antibody identification

Cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed in complete DMEM-Benz (20% FBS (Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin/100 μg/mL streptomycin (Sigma), 25U/mL benzonase (Sigma)). Following one wash in cDMEM-Benz, and two washes in cDMEM, PBMCs were surface-stained for cell markers. Briefly, cells resuspended in Brilliant Stain Buffer (BD Biosciences) were stained with an antibody cocktail for a dump channel (CD3, CD14, CD16, CD56, & CD8a) as well as for Memory B cell gating (CD19, CD20, CD38, CD27, & IgD) on ice for 30 min (BioLegend, BD Biosciences). Following a PBS wash, Live/Dead Fixable Aqua stain (ThermoFisher) was applied. After sorting with a FACSAriaIII, live CD19+ CD20+ CD38+ CD27+ IgD-cells were seeded into 6-well plates on a feeder layer of mitomycin-treated MS40L cells in day 0 culture media of complete Iscove’s medium (cIMEM, 20% Low IgG FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin/100 μg/mL streptomycin, 5 μg/mL Insulin and 50 μg/mL hu Transferrin) supplemented with 100 U/ml Hu rIL-2 (GenScript), and 100 ng/mL Hu rIL-21 (Stemcell Technologies). Seven days later, cell concentrations were readjusted to 250,000 c/mL and culture media was changed to cIMEM supplemented with 500 U/mL Hu rIFN-α 2b (PBL Assay), 50 ng/mL Hu rIL-6 (Stemcell Technologies) and 10 ng/mL Hu rIL-15 (BioLegend). On day 8–10 after sorting, cells were loaded onto OptoSelect 11K chips (Berkeley Lights, Inc.) wherein they were isolated as single cells in nanoliter pens using OEP light cages and were screened in a 30 min time course assay for secretion of antibodies that bound to streptavidin beads (Spherotech) coated with 10μg/mL biotinylated SARS-CoV-2 Delta.HexaPro spike ectodomains. Secreted antibodies were detected with 1μg/mL goat anti-human IgG (H + L)-Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen), which was added to the cell culture media used to resuspend the antigen-coated beads.

Synthesis of cDNA was carried out on-chip using the Berkeley Lights OptoSeq BCR kit, according to the manufacturer’s directions. First-strand reaction products were exported on mRNA capture beads and deposited into individual wells of a 96-well plate. Total cDNA was amplified using Platinum SuperFi II polymerase (Invitrogen). After enzymatic cleanup, antibody heavy and light chain variable domains were amplified with one or two rounds of nested PCR using Platinum II Hot-Start polymerase (Invitrogen) using previously published primer sets.52 , 53 The resulting PCR products were assessed using 96w E-gels (Thermo Fisher) and paired wells were sequenced and analyzed using the International ImMunoGeneTics Information System (IMGT)/V-Quest webserver.42 , 54 Unique VH and VL domains were cloned into linearized antibody expression vectors (human IgG1 and relevant light chain) using Gibson assembly (NEB) according to the manufacturer’s directions. Ligation reactions were transformed into 5-alpha F’Iq competent E. coli cells (NEB). QIAprep 96 Turbo Miniprep kits (Qiagen) were used to isolate plasmids according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, S block wells containing 1.1 mL of LB media spiked with antibiotic were inoculated with single colonies and incubated overnight at 37°C with agitation. DNA extraction was carried out with Qiagen buffer solutions and protocols. Plasmids were sequenced to ensure that the genes were in-frame, and the cloned heavy and light chain variable domains were compared to PCR sequences.

Monoclonal antibody production and purification

Test expressions of each isolated antibody were carried out in 2.5 mL cultures of ExpiCho cells cultured in 24-well blocks. ExpiCho cells were transiently transfected and antibodies were allowed to express for 5 days. Cell supernatants were clarified and used directly in ELISA and neutralization screens. Antibodies of interest were produced in larger (25-200mL) cultures of ExpiCho cells and purified from cell supernatants using Protein A affinity chromatography with the AmMag system (Genscript).

Fab production

Purified IgGs were digested with 5% w/w papain for 3 h at 37°C. The resulting Fabs were purified from the Fc via a kappa select or lambda select column, as appropriate. Undigested IgG and F(ab’)2 were removed by SEC purification with an S75 Increase column.

Production of recombinant virions

Recombinant SARS-CoV-2-pseduotyped VSV-ΔG-GFP virions were generated by transfecting 293T cells with phCMV3-SARS-CoV-2 S plasmids (wild-type/G614 or indicated variant of concern) using TransIT according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Mirus Bio). At 24 h post-transfection, cells were washed twice with OptiMEM and were infected with VSV-G pseudotyped ΔG-GFP parent virus (VSV-G∗ΔG-GFP) at MOI = 2 for 2 h with rocking. The virus was then removed, and the cells were washed twice with OPTI-MEM containing 2% FBS (OPTI-2) before fresh OPTI-2 was added. Supernatants containing SARS-CoV2-VSVpp were removed 24 h post-infection and clarified by centrifugation.

Viral titrations

Vero cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density sufficient to produce a monolayer at the time of infection. Then, 5-fold serial dilutions of pseudovirus were made and added to cells in triplicate wells. Infection was allowed to proceed for 12–16 h at 37°C. The cells were then fixed with 4% PFA and stained with Hoescht (1μg/mL in PBS). Cells were washed once with PBS and pseudovirus titers were quantified as the number of fluorescent forming units (ffu/mL) using a CellInsight CX5 imager (ThermoScientific) and automated enumeration of cells expressing GFP.

Neutralization assay

Pre-titrated amounts of rVSV-SARS-CoV-2 (parental or variant) were incubated with a 1:10 dilution of vaccinee sera or antibody expression supernatant or with serially diluted purified mAbs or corresponding Fab at 37°C for 1 h before addition to confluent Vero monolayers in 96-well plates. Infection proceeded for 16–18 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 before the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 1ug/mL Hoescht. Cells were imaged using a CellInsight CX5 imager and infection was quantified by automated enumeration of total cells and those expressing GFP. Infection was normalized to the average number of cells infected with rVSV-SARS-CoV-2 incubated with normal human sera or an huIgG isotype control. Neutralization IC50 values were calculated using nonlinear regression in GraphPad Prism 9.0.

High-throughput SPR epitope binning

Epitope binning was performed with a classical sandwich assay format on a Carterra LSA HT-SPR instrument equipped with a HC30M sensor chip (Carterra) at 25°C and in an HBSTE-BSA running buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween 20, supplemented with 0.5 mg/mL BSA). Two microfluidic modules, a 96-channel print-head (96PH) and a single flow cell (SFC), were used to deliver samples onto the sensor chip. The chip was activated with a freshly prepared solution of 130 mM 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) (Pierce PG82079) and 33 mM N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (Sulfo-NHS) (ThermoFisher Scientific 24510) in 0.1 M MES pH 5.5 using the SFC. Antibodies were diluted to 10 μg/mL in 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5) and immobilized in duplicate using the 96PH for 10 min. Unreactive esters were quenched with a 7-min injection of 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) using the SFC. The binning analysis was performed over this array with the HBSTE-BSA buffer as the running buffer and sample diluent. The RBD antigen was injected in each cycle for 4 min at 50 nM and followed immediately by a 4-min injection of the analyte antibody soluble ACE-2 at 200nM. The surface was regenerated each cycle with double pulses (17 s per pulse) of 10 mM Glycine pH 2.0. Data was processed and analyzed with Epitope software (Carterra). Briefly, data was referenced using unprinted locations on the array and each binding cycle was normalized to the RBD capture level. The binding level of the analyte antibody just after the end of the injection was compared to that of a buffer only injection. Signals that were significantly increased relative to the buffer controls are described as sandwiches and represent non-blocking behavior. Competition results were visualized as a heatmap that depicts blocking relationships of analyte/ligand pairs. Antibodies with similar patterns of competition are clustered together in a dendrogram and are assigned to shared communities.

High-throughput SPR binding kinetics

Binding kinetics measurements were performed on the Carterra LSA platform using CMDP sensor chips (Carterra) at 25°C. Two different surface capture lawns were prepared with 25 mM MES pH 5.5 with 150 mM NaCl and 0.05% Tween 20 as a running buffer. In both cases, the chip was activated with a freshly prepared solution of 130 mM 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) + 33 mM N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (Sulfo-NHS) in 0.1 M MES pH 5.5 using the SFC. 50ug/mL of either goat anti-Human IgG Fc secondary antibody (for IgG capture) (VWR, 103255–066) or a 1:1 mixture of bivalent CH1-kappa LC (ThermoFisher Scientific 7103302100) and CH1-lambda LC (ThermoFisher Scientific 7103312100) antibody (for Fab capture) was diluted into 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.5) and immobilized for 10 min. Unreactive esters were quenched with a 7-min injection of 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) using the SFC. IgGs and Fabs were captured using the 96PH, with 1X HBSTE buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA and 0.01% Tween 20) as running buffer and antibody diluent. Each IgG or Fab was immobilized onto 6-8 separate spots of the same chip, enabling replicated binding kinetics measurements.

A five-fold (for IgG binding) or two-fold (for Fab binding) dilution series of each spike was prepared in 1xHBSTE-BSA buffer. The spike was then injected onto the chip surface using the SFC, from the lowest to the highest concentration, without regeneration in between. Five to six injections of buffer before the lowest non-zero concentration were used for signal stabilization. For each concentration, baseline data were collected for 120 s, association data for 300 s and dissociation data for 900 s. After the titration of each analyte, the chip surface was regenerated with two pulses (17 s per pulse) of 10mM Glycine, pH 2.0. IgGs and Fabs were re-captured at the start of each analyte cycle. The running buffer for all kinetic steps was 1xHBSTE-BSA.

Titration data were processed with the Kinetics software package (Carterra), including reference subtraction, buffer subtraction and data smoothing. Spike binding time courses for each antibody were fitted to a 1:1 Langmuir model to derive ka, kd and KD values. Due to its trimeric nature, the spike interaction with IgG will have an avidity component.

Epitope mapping via negative stain EM

Purified HexaPro.D614G spike or HexaPro.BA.1 ectodomain was incubated with 3-fold molar excess of 1C3 IgG, 2A10 IgG, 4H4 IgG, 2E6 IgG and 1H2 IgG or Fab overnight at RT. Each complex was diluted in 1x TBS to an absorbance A280 value of 0.03 and 4μL was applied to freshly glow-discharged, carbon-coated 400mesh copper grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 1 min. Excess sample was blotted before the grid was quickly washed with water. Excess liquid was again blotted before the grids were stained with 0.75% uranyl acetate (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 2 min. Excess stain was blotted and the grids were left to air dry. TEM images were collected using SerialEM55 on a Titan Halo 300kV electron microscope (Thermo Fisher) equipped with a K3 direct electron detector camera (Gatan) or Falcon 3EC detector (Thermo Fisher) at a magnification of 18,000×. Cryosparc43 was used for motion correction, CTF estimation, particle picking, 2D classification and 3D reconstruction. Maps were aligned and prepared using ChimeraX.44

Crystallographic structure determination and data processing

2A10 Fab and SARS-CoV-2 RBD, purified as described above, were combined to form a 1:1 Fab-RBD complex with excess Fab. After 1 h at 4°C, Fab-RBD complex was purified using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (Sigma GE28-9909-44) into 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris pH 7.4. The sample was filtered and concentrated to estimated protein concentration 7.4 mg/mL.

A vapor diffusion hanging drop was formed from 1 μL of the above protein and 1 μL of 23%w/v PEG 3350, 230 mM ammonium fluoride. This reagent was an optimization of condition 60 from the JCSG Top 96 screening block (Rigaku 1009846). Crystals appeared after 17 days of incubation at 20°C and were harvested after 22 days. The cryoprotectant was 23%w/v PEG 3350, 230 mM ammonium fluoride, 10%v/v glycerol. The structure was determined to 2.57 Å resolution at the Eli Lilly LRL-CAT beamline of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory.

Data processing employed XDS 2/5/2021,37 AIMLESS 0.7.7,47 CCP4,48 autoPROC 1.1.7,49 and PHENIX 1.20.1–4487.56 Molecular replacement using Phaser 2.8.350 was by reference to PDB:6XE1 57 for the SARS-CoV-2 RBD, and a homology model created by SWISS-MODEL45 for 2A10 Fab. Protein structure was corrected using Coot 0.9.2-pre,39 with refinement by phenix.refine.38 Structures were aligned and figures were created using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.5.2 Schrödinger, LLC.

Spike-fab complex structure determination by Cryo-EM

Antibody complexes were obtained by incubating spike protein with ∼3 M excess of Fabs at room temperature. 3 μL of the sample for cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) imaging were prepared by applying the complex solution to Quantifoil-2/2 grids with coated Graphene Oxide (Electron Microscopy Sciences), followed by blotting and plunge-freezing into liquid ethane using a Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Data processing

TEM images were collected automatically using EPU on a Titan Krios 300 kV electron microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a magnification of 75,900 with a Gatan K3 detector for a total dose of ∼50 e−/A2. Data processing was performed using Cryosparc v3.3.1.58 Movies were motion-corrected by Patch motion correction. CTF estimation was performed using Patch CTF estimation. Particles were first picked using the CryoSPARC blob picker, then those particles selected after 2D classification were used to train Topaz,59 a neural network for further particle picking. Picked particles were extracted and subjected to rounds of 2D classification for selection.

For the 1C3 Fab and SARS-CoV-2 omicron spike complex, the reconstruction was obtained by homogeneous refinement using an Ab-initio model as a reference, followed by local CTF refinements and non-uniform refinement in CryoSPARC. For the ternary 1H2, 2A10, and SARS-CoV-2 D614G spike complex, the reconstruction for the overall complex was obtained by homogeneous refinement using an Ab-initio model as a reference, followed by heterogeneous refinement, and further homogeneous and non-uniform refinement in CryoSPARC. To improve map quality for the antigen-antibody interaction regions, a mask covering the antibody Fv regions and RBD was generated using Chimera.60 Refined particles were subjected to local non-uniform refinement using the generated static mask. For both reconstructions, local resolution estimation was performed in CryoSPARC. Reported resolutions are based on the gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) of 0.143 criteria.